Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Aim and Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Method

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Types of Studies

2.5. Search Strategy

2.6. Study Selection

2.7. Data Extraction

2.8. Data Transformation

2.9. Data Synthesis and Integration

3. Results

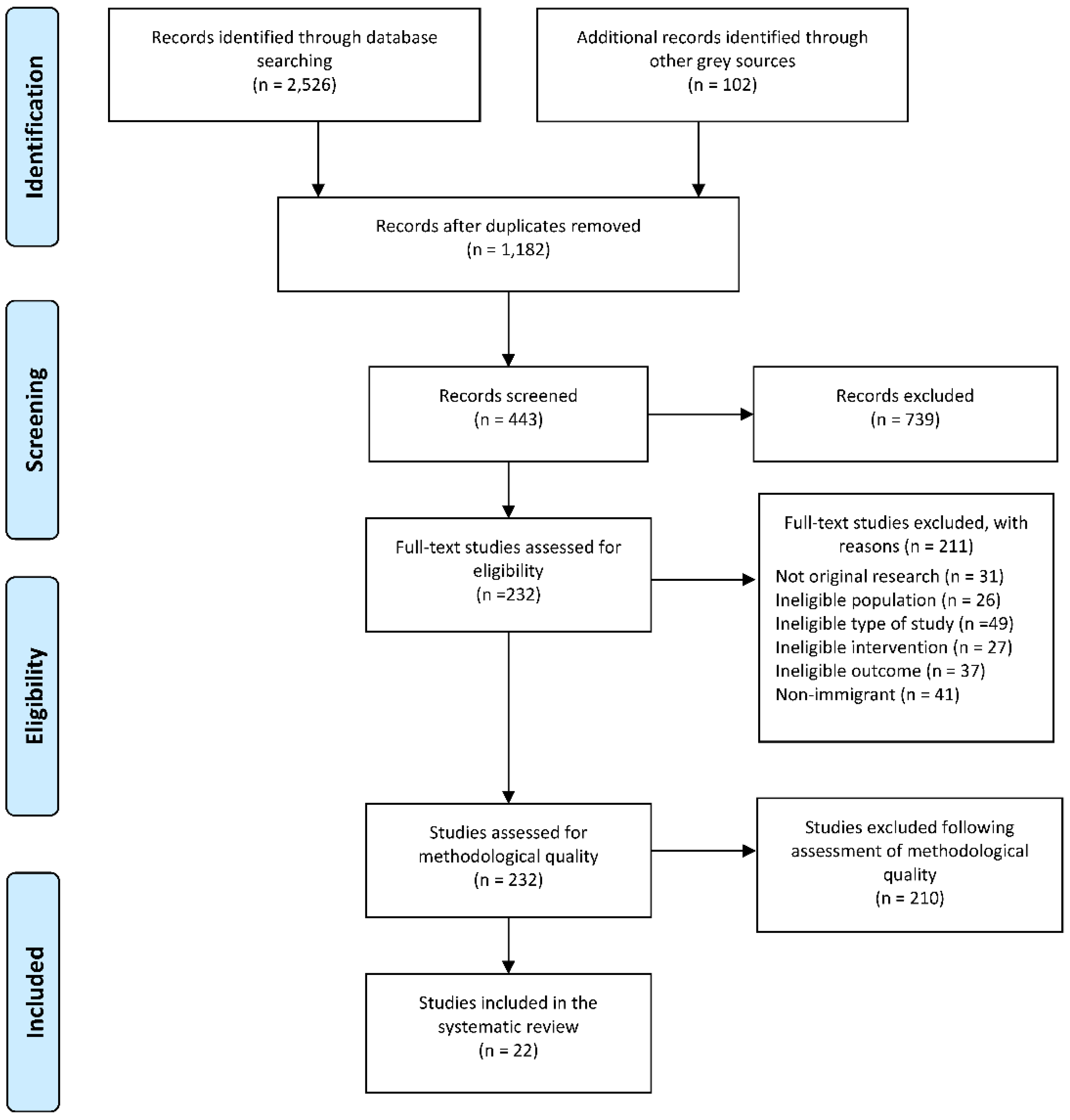

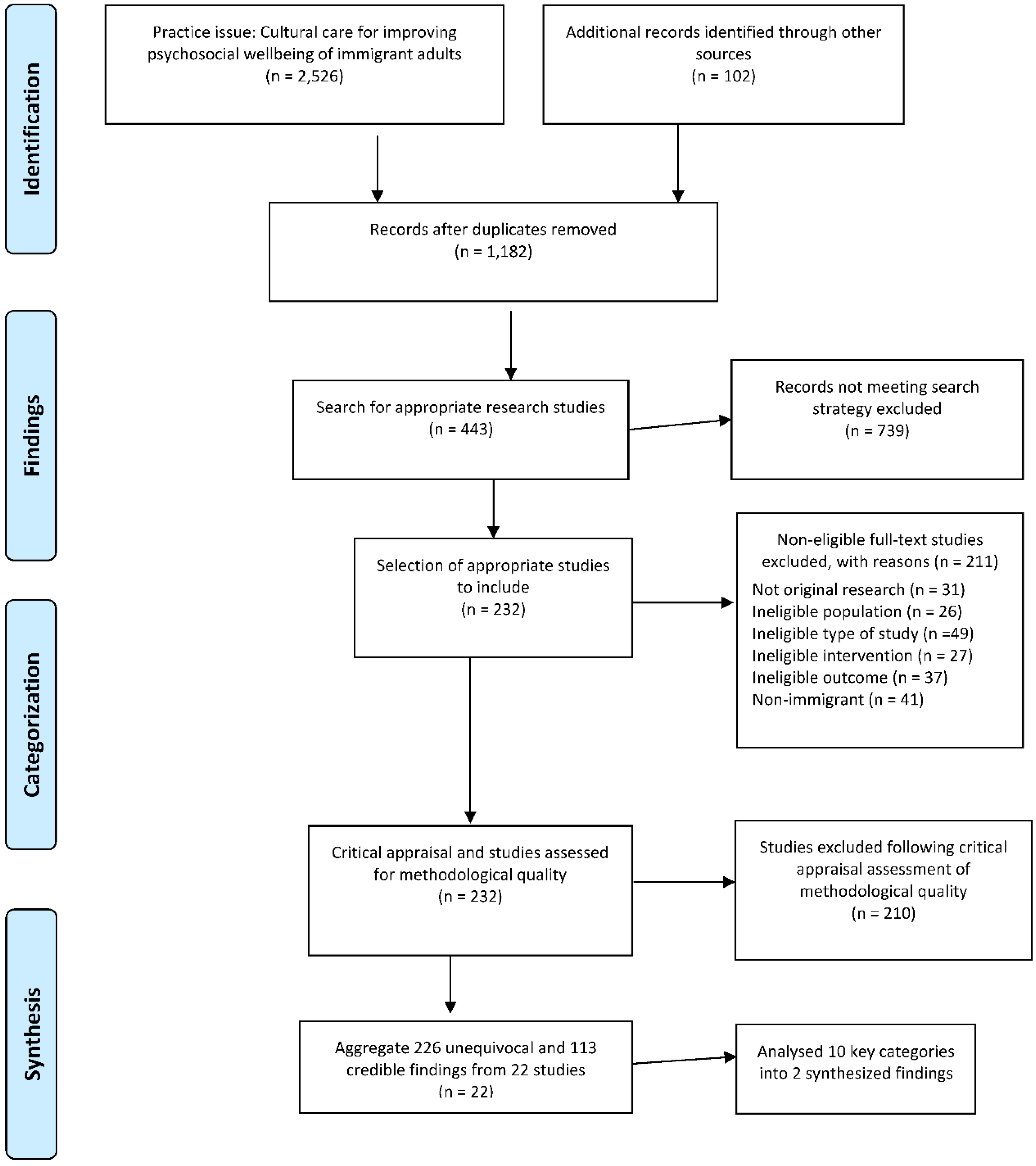

3.1. Study Inclusion

3.2. Participant Characteristics

3.3. Content Analysis

3.4. Synthesized Finding 1: Experiences of Cultural Considerations in Care

3.4.1. Theme 1: Development of Culturally Responsive Care Models

3.4.2. Theme 2: Barriers and Gaps in Culturally Responsive Care in Rural Communities

3.4.3. Theme 3: Patient Information, Education and Culturally Responsive Care

3.5. Synthesized Finding 2: Experiences of Psychosocial Well-Being of Immigrants

3.5.1. Theme 4: Cultural Stigma, Self-Perception of Access, Use and the Role of Healthcare Providers

3.5.2. Theme 5: Impact of Cancer and Linguistically Appropriate Care

3.5.3. Theme 6: Challenges with Psychosocial Well-Being and Culturally Responsive Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Implications

6.1. Practice

6.2. Research

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashing, K.T.; George, M.; Jones, V. Health-related quality of life and care satisfaction outcomes: informing psychosocial oncology care among Latina and African-American young breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashing-Giwa, K.T.; Padilla, G.V.; Tejero, J.S.; Kim, J. Breast cancer survivorship in a multiethnic sample: challenges in recruitment and measurement. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 2004, 101, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Kessie, T.; Caulfield, B. Patient experiences of rehabilitation and the potential for an mHealth system with biofeedback after breast cancer surgery: qualitative study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2020, 8, e19721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burg, M.A.; Lopez, E.D.; Dailey, A; Keller, M.E.; Prendergast, B. The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. Journal of general internal medicine 2009, 24, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, N.J.; Napoles, T.M.; Banks, P.J.; Orenstein, F.S.; Luce, J.A.; Joseph, G. Survivorship care plan information needs: perspectives of safety-net breast cancer patients. PloS one 2016, 11, e0168383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2023; Cancer Society, 2023. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics.

- Canadian Cancer Society. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2024. 2024. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics.

- Costas-Muñiz, R.; Garduño-Ortega, O.; Hunter-Hernández, M.; Morales, J.; Castro-Figueroa, E.M.; Gany, F. Barriers to psychosocial services use for Latina versus non-Latina white breast cancer survivors. American journal of psychotherapy 2021, 74, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, J.; Frisina, A.; Hack, T.; Parascandalo, F. A peer health educator program for breast cancer screening promotion: Arabic, Chinese, South Asian, and Vietnamese immigrant women’s perspectives. Nursing Research and Practice 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.; Jones, R.; Tipene-Leach, D. et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health 2019, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, M.S.; Fehr, F.; Smith, M.; Marshall, M. Mediators of psychosocial well-being for immigrant women living with breast cancer in Canada: A Critical ethnography. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2023, 5, 00. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moissac, D.; Bowen, S. Impact of language barriers on quality of care and patient safety for official language minority Francophones in Canada. Journal of Patient Experience 2019, 6, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Woods, M. Systematic reviews and qualitative methods. In Qualitative research: theory, method and practice, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2010; pp. 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza, M.S.; Latif, E.; McCarthy, A.; Karkada, S.N. Experiences and perspectives of ethnocultural breast cancer survivors in the interior region of British Columbia: A descriptive cross-sectional approach. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2022, 16, 101095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, M.S.; O'Mahony, J.; Karkada, S.N. Effectiveness and meaningfulness of breast cancer survivorship and peer support for improving the quality of life of immigrant women: A mixed methods systematic review protocol. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2021, 10, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, A.; Sakellariou, D. Healthcare access for refugee women with limited literacy: layers of disadvantage. International journal for equity in health 2017, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada, 2023, Canada, welcome historic number of newcomers in 2023. Immigrant, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, Modified on 23. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2022/12/canada-welcomes-historic-number-of-newcomers-in-2022.

- Green, E.K.; Wodajo, A.; Yang, Y.; Sleven, M.; Pieters, H.C. Perceptions of support groups among older breast cancer survivors: “I've heard of them, but I've never felt the need to go”. Cancer nursing 2018, 41, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gripsrud, B.H.; Brassil, K.J.; Summers, B.; Søiland, H.; Kronowitz, S.; Lode, K. Capturing the experience: Reflections of women with breast cancer engaged in an expressive writing intervention. Cancer Nursing 2016, 39, E51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gushulak, B.D.; MacPherson, D.W. Health aspects of the pre-departure phase of migration. PLoS medicine 2011, 8, e1001035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, R.; Heus, L.; Baker, N.A.; Dastur, D.; Leung, F.H.; Leung, E.; Parsons, J.A. Designing a multifaceted survivorship care plan to meet the information and communication needs of breast cancer patients and their family physicians: results of a qualitative pilot study. BMC medical informatics and decision making 2013, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill-Kayser, C.E.; Vachani, C.C.; Hampshire, M.K.; Di Lullo, G.; Jacobs, L.A.; Metz, J.M. Impact of internet-based cancer survivorship care plans on health care and lifestyle behaviors. Cancer 2013, 119, 3854–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwee, J.; Bougie, E. Do cancer incidence and mortality rates differ among ethnicities in Canada? Health Reports 2021, 32, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Juarez, G.; Mayorga, L.; Hurria, A.; Ferrell, B. Survivorship education for Latina breast cancer survivors: empowering survivors through education. Psicooncologia 2013, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O'brien, K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation science 2010, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levesque, J.V.; Gerges, M.; Girgis, A. Psychosocial experiences, challenges, and coping strategies of Chinese–Australian women with breast cancer. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing 2020, 7, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarondo, L.; Lockwood, C.; McArthur, A. Barriers and facilitators to implementing evidence in African health care: a content analysis with implications for action. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2019, 16, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lluch, C.; O'Mahony, J.; D'Souza, M.; Hawa, R. Health Literacy of Healthcare Providers and Mental Health Needs of Immigrant Perinatal Women in British Columbia: A Critical Ethnography. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2023, 44, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Porrit, K.; Munn, Z.; Rittenmeyer, L.; Salmond, S.; Bjerrum, M.; Loveday, H.; Carrier, J.; Stannard, D.; Aromataris, E.; et al. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. Joanna Briggs Institute. Reviewers’ Manual. Edited by Aromataris E, Munn Z.(editors), The Joanna Briggs Institute 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Class, M.; Gomez- Duarte, J.; Graves, K.; Ashing-Giwa, K. A contextual approach to understanding breast cancer survivorship among Latinas. Psycho- Oncology 2012, 21, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Class, M.; Perret-Gentil, M.; Kreling, B.; Caicedo, L.; Mandelblatt, J.; Graves, K.D. Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. Journal of Cancer Education 2011, 26, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Prisma-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muliira, J.; D'Souza, M.S. Effectiveness of patient navigator interventions on uptake of colorectal cancer screening in primary care settings. Japan Journal of Nursing Science 2016, 13, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliira, J.; D'Souza, M.S.; Maroof, S. Contrasts in Practices and Perceived Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening by Nurses and Physicians Working in Primary Care Settings in Oman. Journal of Cancer Education 2016, 31, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muliira, J.M.; D'Souza, M.S.; Ahmed, S.M.; Al-Dhahli, N.S.; Al-Jahwari, F.R.M. Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening in Primary Care Settings: Attitudes and Knowledge of Nurses and Physicians. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing 2016, 3, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nápoles, A.M.; Santoyo-Olsson, J.; Chacón, L.; Stewart, A.L.; Dixit, N.; Ortiz, C. Feasibility of a mobile phone app and telephone coaching survivorship care planning program among Spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors. JMIR cancer 2019, 5, e13543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.; Gough, D. Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. 2020, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porritt, K.; Gomersall, J.; Lockwood, C. JBI's systematic reviews: study selection and critical appraisal. AJN The American Journal of Nursing 2014, 114, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, L.; D’Souza, M.S.; Tinampay, C. Effectiveness of breast cancer screening interventions in improving screening rates and preventive activities in Muslim refugee and immigrant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 2022, 00, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh-Carlson, S.; Wong, F.; Oshan, G. Evaluation of the delivery of survivorship care plans for South Asian female breast cancer survivors residing in Canada. Current Oncology 2018, 25, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh–Carlson, S.; Wong, F.; Martin, L.; Nguyen, S.K.A. Breast cancer survivorship and South Asian women: understanding about the follow-up care plan and perspectives and preferences for information post-treatment. Current Oncology 2013, 20, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada, 22, Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.

- Tam Ashing, K.; Padilla, G.; Tejero, J.; Kagawa-Singer, M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer 2003, 12, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, C.; Scanlon, K.; Scott, E.; Ream, E.; Harding, S.; Armes, J. Survivorship care and support following treatment for breast cancer: a multi-ethnic comparative qualitative study of women’s experiences. BMC Health Services Research 2016, 16, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.L.; Ghahari, S. Immigrants’ Experience of Health Care Access in Canada: A Recent Scoping Review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 2023, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Campbell, J.; Hopp, L. Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual 2017 Apr 19; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia; pp. 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Warmoth, K.; Cheung, B.; You, J.; Yeung, N.C.; Lu, Q. Exploring the social needs and challenges of Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study using an expressive writing approach. International journal of behavioural medicine 2017, 24, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.Y.; Fang, C.Y.; Ma, G.X. Breast cancer experience and survivorship among Asian Americans: a systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2014, 8, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Searches, Inclusion Criteria, and MeSH | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Breast cancer, (female* or wom?n or mother* or grandmother* or girl*).mp. (brca or (breast adj4 (adenocarcinoma* or cancer* or carcinoma* or metasta* or neoplasm* or tumo?r))).ti,ab,kw. ((brca or mastectomy*) or (breast* or mammary) adj4 (adenocarcinoma* or cancer* or carcinoma* or metasta* or malignan* or neoplasm* or tumor* or tumour*)).mp. Female/ Breast Neoplasms/ "Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Syndrome"/ Breast Cancer Lymphedema/ Breast Carcinoma in Situ/ Breast Neoplasms/ Carcinoma, Ductal, Breast/ Carcinoma, Lobular/ Inflammatory Breast Neoplasms/ exp Mastectomy/ Triple Negative Breast Neoplasms/ Unilateral Breast Neoplasms/ Breast Diseases/ Breast/ Mammary Glands, Human/ Nipples/ Neoplasms/ breast neoplasms/or breast carcinoma in situ/or breast neoplasms, male/or carcinoma, ductal, breast/or carcinoma, lobular/or "hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome"/or inflammatory breast neoplasms/or triple negative breast neoplasms/or unilateral breast neoplasms/ |

296563 |

| 2 | Breast Diseases/ | 12270 |

| 3 | Breast Cancer Lymphedema/ | 205 |

| 4 | breast/or mammary glands, human/or nipples/ | 47048 |

| 5 | 2 or 4 | 55209 |

| 6 | Neoplasms/ | 429418 |

| 7 | 5 and 6 | 2150 |

| 8 | exp Mastectomy/ | 32022 |

| 9 | 1 or 7 or 8 | 301213 |

| 10 | Cultural care, peer-based support groups grassroots community-based support groups supportive care psychosocial care emotional support ((emotional or community or grassroots or psychosocial or psychologic* or peer* or self-help or social) adj3 (group* or support* or care or caring)).mp. Peer Group/ Self-Help Groups/ cross-cultural comparison/or cultural characteristics/or cultural diversity/or ethnology/ stigma/cultural stigma/shame aging/ageism/seniors rural community/rural health/rural area |

53567 |

| 11 | Immigrant women, asian american chinese alien* emigra* foreigner* immigra* refugee* African Americans/ Hispanic Americans/ Acculturation/ Multilingualism/ Cross-Cultural Comparison/ Cultural Characteristics/ Cultural Diversity/ Ethnology/ "Emigrants and Immigrants"/ Refugees/ Undocumented Immigrants/ "emigrants and immigrants"/or undocumented immigrants/or homeless persons/or refugees/or "transients and migrants"/ |

41010 |

| 13 | Quality of life, ambivalence over emotional expression depressive symptoms quality of life well being wellbeing well-being Tools: HRQOL Affective Symptoms/ Quality of Life/ Risk Factors/ Uncertainty/ |

21580 |

| 14 | Survivors, (survivor* or survivour*).mp. Survivors/ Cancer Survivors/ Lived experience |

21780 |

| Research Studies | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Total Scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addington, E. L., Sohl, S. J., Tooze, J. A., & Danhauer, S. C. (2018). Convenient and Live Movement (CALM) for women undergoing breast cancer treatment: Challenges and recommendations for internet-based yoga research. Complementary therapies in medicine, 37, 77-79. | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Ahmed, K., Marchand, E., Williams, V., Coscarelli, A., & Ganz, P. A. (2016). Development and pilot testing of a psychosocial intervention program for young breast cancer survivors. Patient education and counseling, 99(3), 414-420. |

Y | U | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Ashing-Giwa, K. T., Padilla, G., Tejero, J., Kraemer, J., Wright, K., Coscarelli, A., ... & Hills, D. (2004). Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer, 13(6), 408-428. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Brennan, L., Kessie, T., & Caulfield, B. (2020). Patient experiences of rehabilitation and the potential for an mHealth system with biofeedback after breast cancer surgery: qualitative study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(7), e19721. | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | 8 |

| Burg, M. A., Lopez, E. D., Dailey, A., Keller, M. E., & Prendergast, B. (2009). The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. Journal of general internal medicine, 24(2), 467. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-009-1012-y. United States of America. | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Burke, N. J., Napoles, T. M., Banks, P. J., Orenstein, F. S., Luce, J. A., & Joseph, G. (2016). Survivorship care plan information needs: perspectives of safety-net breast cancer patients. PloS one, 11(12), e0168383. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168383. United states of America. | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | U | Y | U | Y | Y | 7 |

| Costas-Muñiz, R., Garduño-Ortega, O., Hunter-Hernández, M., Morales, J., Castro-Figueroa, E. M., & Gany, F. (2021). Barriers to psychosocial services use for Latina versus non-Latina white breast cancer survivors. American journal of psychotherapy, 74(1), 13-21. | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Crawford, J., Frisina, A., Hack, T., & Parascandalo, F. (2015). A peer health educator program for breast cancer screening promotion: Arabic, Chinese, South Asian, and Vietnamese immigrant women’s perspectives. Nursing Research and Practice, 2015. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Green, E. K., Wodajo, A., Yang, Y., Sleven, M., & Pieters, H. C. (2018). Perceptions of support groups among older breast cancer survivors: “I've heard of them, but I've never felt the need to go”. Cancer nursing, 41(6), E1. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000522. USA. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | 8 |

| Gripsrud, B. H., Brassil, K. J., Summers, B., Søiland, H., Kronowitz, S., & Lode, K. (2016). Capturing the experience: Reflections of women with breast cancer engaged in an expressive writing intervention. Cancer Nursing, 39(4), E51. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | 9 |

| Haq, R., Heus, L., Baker, N. A., Dastur, D., Leung, F. H., Leung, E., ... & Parsons, J. A. (2013). Designing a multifaceted survivorship care plan to meet the information and communication needs of breast cancer patients and their family physicians: results of a qualitative pilot study. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 13(1), 1-13. Canada | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 9 |

| Hill-Kayser, C. E., Vachani, C. C., Hampshire, M. K., Di Lullo, G., Jacobs, L. A., & Metz, J. M. (2013). Impact of internet-based cancer survivorship care plans on health care and lifestyle behaviors. Cancer, 119(21), 3854-3860. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | 8 |

| Juarez, G., Mayorga, L., Hurria, A., & Ferrell, B. (2013). Survivorship education for Latina breast cancer survivors: empowering survivors through education. Psicooncologia, 10(1), 57. DOI: 10.5209/rev_PSIC. 2013.v10.41947. USA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | 9 |

| Levesque, J. V., Gerges, M., & Girgis, A. (2020). Psychosocial experiences, challenges, and coping strategies of Chinese–Australian women with breast cancer. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 7(2), 141-150. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 9 |

| Levine, E. G., Aviv, C., Yoo, G., Ewing, C., & Au, A. (2009). The benefits of prayer on mood and well-being of breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 17, 295-306. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | 9 |

| Lopez-Class, M., Gomez- Duarte, J., Graves, K., & Ashing-Giwa, K. (2012). A contextual approach to understanding breast cancer survivorship among Latinas. Psycho-Oncology, 21(2), 115-124. | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Lopez-Class, M., Perret-Gentil, M., Kreling, B., Caicedo, L., Mandelblatt, J., & Graves, K. D. (2011). Quality of life among immigrant Latina breast cancer survivors: realities of culture and enhancing cancer care. Journal of Cancer Education, 26(4), 724-733. | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Nápoles, A. M., Santoyo-Olsson, J., Chacón, L., Stewart, A. L., Dixit, N., & Ortiz, C. (2019). Feasibility of a mobile phone app and telephone coaching survivorship care planning program among Spanish-speaking breast cancer survivors. JMIR cancer, 5(2), e13543. | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Singh–Carlson, S., Wong, F., Martin, L., & Nguyen, S. K. A. (2013). Breast cancer survivorship and South Asian women: understanding about the follow-up care plan and perspectives and preferences for information post treatment. Current Oncology, 20(2), 63-79. | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Tompkins C, Scanlon K, Scott E, Ream E, Harding S, Armes J. Survivorship care and support following treatment for breast cancer: a multi-ethnic comparative qualitative study of women’s experiences. BMC health services research. 2016 Dec 1;16(1):401. | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Warmoth, K., Cheung, B., You, J., Yeung, N. C., & Lu, Q. (2017). Exploring the social needs and challenges of Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study using an expressive writing approach. International journal of behavioral medicine, 24, 827-835. | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Wen, K. Y., Fang, C. Y., & Ma, G. X. (2014). Breast cancer experience and survivorship among Asian Americans: a systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 8, 94-107. | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9 |

| Total ratings for 22 articles | 20 | 19 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 188 |

| Total percentage of 22 articles | 91% | 86% | 86% | 95% | 82% | 82% | 73% | 82% | 91% | 86% | 85% |

| Yes | No | Unclear | Not applicable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

|

□ | □ | □ | □ |

| Reference, title, authors | Methods, design, approach | Phenomena, intervention | Population, Comparison | Outcomes | Results, Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addington, E. L., Sohl, S. J., Tooze, J. A., & Danhauer, S. C. (2018). Convenient and Live Movement (CALM) for women undergoing breast cancer treatment: Challenges and recommendations for internet-based yoga research. Complementary therapies in medicine, 37, 77-79. |

Pilot trial of cancer-adapted yoga classes delivered via internet-based, multipoint videoconferencing to women undergoing radiation or chemotherapy for breast cancer. Recruited women who met the inclusion criteria (e.g., stage 0-III breast (GoToMeeting). The participants were asked to attend 12 biweekly, 75-minute, Integral yoga classes that included gentle postures, breathing, meditation, and relaxation. The classes were taught by a Registered Yoga Teacher with specialized training in cancer-adapted yoga. The participants could see and interact with the instructor and other participants during the classes. Collected data on feasibility and acceptability, including enrollment rate, retention, adherence, satisfaction ratings, and qualitative feedback from program evaluation forms and telephone interviews. | Feasibility and acceptability of delivering cancer-adapted yoga classes via internet-based videoconferencing to women undergoing radiation or chemotherapy for breast cancer. Interested in whether this approach could overcome the barriers yoga participants faced by many cancer patients, such as physical limitations, fatigue, transportation, issues, and scheduling conflicts. They also wanted to explore how the participants and the yoga instructor perceived the online yoga program and how it could be improved. |

Women who were undergoing radiation or chemotherapy for breast cancer. The participants met the inclusion criteria, which included having stage 0-III breast cancer and elevated distress. The participants did not meet the exclusion criteria, which included regular yoga or vigorous exercise, and recent or planned surgery. The participants were recruited from a comprehensive cancer centre in the southeastern US. The participants were provided with internet-connected computers and detailed instructions on how to install and use the videoconferencing software. The participants were asked to attend 12 biweekly, 75-minute, integral yoga classes that included gentle postures, breathing, meditation, and relaxation. The classes were taught by a Registered Yoga Teacher with specialized training in cancer-adapted yoga. The participants could see and interact with the instructor and other participants during the classes. |

Difficulties in feasibility and accessibility for the program Recruitment: Difficulties in recruiting participants who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Retention: Challenges in retaining participants throughout the study, mainly due to cancer-related barriers. Adherence: Collected data on the participant’s adherence to the online yoga program, including attendance at the yoga classes. Participant Focused Feedback & Acceptability Satisfaction: Measured the participants’ satisfaction with the online yoga program using satisfaction ratings. Qualitative feedback: Qualitative feedback from the participants and the yoga instructor on how to improve the online yoga program. Improvement Class times: Offering more varied class times to enhance the feasibility and acceptability of the online yoga program. Enrollment timing: Recommended enrolling patients after they complete treatment to minimize cancer-related barriers. Technology interface: Simplifying the technology interface to make it easier for participants to use. |

Feasibility and acceptability of online yoga classes for women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Despite recruitment and retention challenges due to cancer-related and technological barriers, the program was generally well-received. Improvements suggested including more flexible class times and enrolling. |

| Ahmed, K., Marchand, E., Williams, V., Coscarelli, A., & Ganz, P. A. (2016). Development and pilot testing of a psychosocial intervention program for young breast cancer survivors. Patient education and counseling, 99(3), 414- 420. |

Needs assessment with community organizations and YBCS to identify the gaps in services and the priorities for the intervention. They also involved advisory committees composed of survivors and community representatives in the program planning process. Psychosocial program based on evidence-based models of treatment that included psychoeducation, skill-building exercises, and discussion. The program had two modules: one focused on anxiety management and the other on relationships and sexuality. The program was delivered in a group format with a workbook for each participant. Impact of the intervention on the participants’ knowledge, confidence, and ability regarding key concepts using a questionnaire before and after the program. They also collected qualitative feedback from the participants. The results showed an increase in self-reported scores on both modules and positive comments on the program content and format. |

The psychosocial challenges faced by young breast cancer survivors (YBCS). These challenges include managing anxiety, fear of recurrence, decision-making, and coping with sexuality/relations issues. | The participants were young breast cancer survivors (YBCS) who were diagnosed before the age of 45 and who had completed active treatment, excluding hormonal therapy. The participants were recruited from local community organizations, medical facilities, and social media in the Los Angeles area3. The workshop group sizes ranged from 3 to 8 participants. Only limited demographic data were available for participants from UCLA, where the mean age was 41.7 years (median 43 years) |

Psychosocial challenges of Young Breast Cancer Survivors (YBCS): explores the unique psychosocial issues that YBCS face, such as anxiety, fear of recurrence, decision-making difficulties, and sexuality/relationship issues. Development and effectiveness of a psychosocial intervention program: Creation of an intervention program designed to address the psychosocial challenges identified in the first theme. It covers the process of needs assessment, stakeholder engagement, and pilot testing. Effectiveness - discusses the evaluation of the intervention program’s effectiveness in improving psychosocial outcomes for YBCS. It includes the analysis of pre-and post-test questionnaires and qualitative feedback surveys. Dissemination and Integration of the Intervention Program: This theme looks at how the intervention program was disseminated to community clinical settings and integrated into oncology care. It discusses the training of local facilitators and the potential for broader implementation. |

Presents a psychosocial intervention program developed for young breast cancer survivors (YBCS) to address their unique challenges such as anxiety, fear of recurrence, decision-making, and sexuality/relationship issues. The program was evaluated using pre-and post-test questionnaires and qualitative feedback surveys, and the results showed significant improvements in managing anxiety and improving relationships/sexuality issues. Program fills an unmet need for YBCS and provides a model for integrating psychosocial care with oncology treatment. Wider dissemination of the program and further research for its continuous improvement. |

| Ashing-Giwa, K. T., Padilla, G. V., Tejero, J. S., & Kim, J. (2004). Breast cancer survivorship in a multiethnic sample: challenges in recruitment and measurement. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society, 101(3), 450-465. |

Qualitative research methods to gain a deep understanding of the experiences and concerns of breast cancer survivors from four ethnic groups: African American, Asian American, Latina, and Caucasian. Data were collected through key informant interviews with 20 health professionals and focus group interviews with 102 breast cancer survivors. The key informant interviews provided insights into the professional perspective on the needs and concerns of breast cancer survivors, while the focus group interviews allowed for first-hand accounts of the survivors’ experiences and concerns. The research design is cross-sectional and comparative, collecting data at one point in time and comparing the experiences and concerns of breast cancer survivors across different ethnic groups. Socio-ecological approach, recognizing that individuals are embedded within larger social systems that can influence health outcomes. This comprehensive approach allows for a thorough exploration of the unique challenges faced by breast cancer survivors from diverse ethnic backgrounds. | Personal experiences of breast cancer survivors from four different ethnic backgrounds: African American, Asian American, Latina, and Caucasian. It aims to shed light on their journeys from the point of diagnosis, through the treatment process, and into their lives post-cancer. The study recognizes that each ethnic group may face unique challenges and have distinct perspectives based on their cultural and societal contexts. For instance, language barriers, healthcare access, and social support systems can vary greatly among these groups. These factors can significantly impact a survivor’s experience with breast cancer. By exploring these diverse experiences, the study seeks to inform healthcare providers and policymakers about the specific needs of different ethnic groups. This could lead to the development of more tailored support systems and healthcare interventions that take into account cultural sensitivities and disparities. This underscore the importance of diversity in healthcare research. It highlights that a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective in addressing health issues as complex as cancer. Instead, a more nuanced understanding of patients’ experiences across different ethnic backgrounds can lead to more inclusive and effective healthcare solutions. |

Ethnicity and socioeconomic background: The study involves breast cancer survivors from four different ethnic backgrounds: African American, Asian American, Latina, and Caucasian. These women have varying socioeconomic and cultural contexts that may influence their quality of life and psychosocial experiences. Health-related quality of life: The study assesses the physical, functional, psychological/emotional, and social well-being of breast cancer survivors about their health. It explores the unique challenges and perspectives of different ethnic groups. Cultural and socio-ecological factors: The study examines how culture and socio-ecological factors impact the breast cancer experience of women from diverse backgrounds. These factors include health beliefs, health socialization, relationships, quality of care, spirituality, and work issues. |

Culture and breast cancer experiences: Explores how culture influences the breast cancer experience of women from different ethnic groups, such as African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian. Culture affects women’s health beliefs, coping strategies, family support, spirituality, and access to care. Discusses the need for culturally responsive healthcare services and programs. Psychosocial functioning and social support: examines the psychosocial impact of breast cancer on women’s quality of life, emotional well-being, and mental health. Identifies common psychological issues such as fear, anxiety, denial, and depression. Describes how women use various social resources such as family, friends, support groups, and health professionals to deal with breast cancer. Identity and role changes: how breast cancer affects women’s sense of identity, such as their roles as mothers, wives, and caregivers. Highlights how women’s identity is shaped by their ethnicity, acculturation, socioeconomic status, and education. How women cope with identity changes and challenges due to breast cancer. Barriers and facilitators of health care and psychosocial care evaluates the barriers and facilitators to accessing health care and psychosocial care among women with breast cancer, especially women of color. Emphasizes the importance of socioeconomic and cultural factors, as well as systemic problems in the health care system. Benefits of health education, patient empowerment, and cultural competence. |

Diverse Experiences: The study found that breast cancer survivors from different ethnic backgrounds (African American, Asian American, Latina, and Caucasian) have unique experiences. These experiences are shaped by their cultural and societal contexts. For instance, cultural beliefs about illness and health can influence how these women perceive their diagnosis and treatment. Their societal context, including factors like healthcare access and social support, can also impact their journey through breast cancer. offer more effective support and interventions. Policy Implications: Significant implications for healthcare policies. It suggested that policies need to address healthcare disparities and provide adequate support for cancer survivors from diverse backgrounds. This could involve improving access to healthcare resources, enhancing patient education about the disease, or developing support programs tailored to the needs of different ethnic groups. Understanding these diverse experiences can help healthcare providers offer more personalized care. Healthcare Disparities: Disparities in healthcare access and quality among different ethnic groups. These disparities can be due to a variety of factors, such as language barriers, socioeconomic status, and geographical location. For example, women who do not speak English as their first language might face challenges in understanding their diagnosis or treatment plan. |

| Brennan, L., Kessie, T., & Caulfield, B. (2020). patient experiences of rehabilitation and the potential for an mHealth system with biofeedback after breast cancer surgery: qualitative study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(7), e19721. |

Qualitative research study design to explore the experiences and needs of women during home rehabilitation following surgery for breast cancer and to gather survivors’ perspectives on and requirements from mHealth technology for postoperative breast cancer rehabilitation. Semi structured interviews: Semi structured interviews with 10 breast cancer survivors under two main topics: “Rehabilitation” and “Technology”. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and anonymized. Thematic analysis: Thematic analysis with a semantic, mixed inductive and deductive approach to analyze the interview data, following the process outlined by Braun and Clarke. Identified four main themes under the topic of “rehabilitation experiences” and two main themes under the topic of “technology”. Reported the findings according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist for qualitative studies. |

Breast cancer rehabilitation: physical and psychological challenges that women face after breast cancer surgery and how physiotherapy can help them recover and prevent upper limb dysfunction. Unmet needs and lack of support: Gaps in the current provision of physiotherapy services and information for breast cancer survivors and how they affect their rehabilitation outcomes and quality of life. mHealth technology investigates the potential of mobile health (mHealth) systems, such as apps and wearable sensors, to enhance breast cancer rehabilitation by providing exercise support, biofeedback, and information. User-centered design: TUser-centered design approach to understand the experiences and needs of breast cancer survivors and their preferences and requirements for an mHealth system. | The study included 10 women who had surgery for breast cancer within the last 5 years. They were all white Irish, with a range of education levels, employment statuses, and incomes. They were mostly married or in a domestic partnership, and their ages ranged from 35 to 74 years. The participants had different types of breast surgery, such as lumpectomy, mastectomy, and reconstruction, and different extents of axillary surgery, such as sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary clearance. They also received different types of postoperative physiotherapy, from a single assessment to follow-up appointments or referrals. The participants were recruited from a sports club for breast cancer survivors, which may indicate that they were more physically active than the general population of breast cancer patients |

Rehabilitation experiences: patients’ rehabilitation process, their awareness of the impact of surgery, their expectations and reality of physiotherapy care, their confidence, and challenges in doing home exercises, and their sources of information and support. Unmet needs and lack of support: Gaps in physiotherapy services, information provision, and emotional support for patients after breast cancer surgery. It also highlights the patients’ feelings of isolation, fear, and anxiety during home rehabilitation. Self-driven rehabilitation: Describes the patients’ motivation, proactivity, and resilience in pursuing their recovery. It also discusses the benefits of exercise, peer support, and digital technology for enhancing physical and psychological well-being. Visions for high-quality rehabilitation: Patients’ preferences and recommendations for improving breast cancer rehabilitation. These include more access to physiotherapy, more patient education, more personalized and positive content, and more feedback and encouragement. mHealth system: Participants were open to using an mHealth system for postoperative rehabilitation and expressed their requirements for such a system. |

Main themes from the interviews with 10 breast cancer survivors: acute and long-term consequences of surgery, unmet needs and lack of support, self-driven rehabilitation, and visions for high-quality rehabilitation. These themes reflected the participants’ experiences, challenges, and preferences during home rehabilitation after breast cancer surgery. Unmet needs and mHealth potential: Participants had unmet needs regarding information, physiotherapy, and support during home rehabilitation, and they felt isolated and uncertain about their recovery. mHealth system could address these unmet needs by providing exercise support, biofeedback, and information from a reliable source. Motivation and quality of rehabilitation: Participants were motivated to exercise and recover after surgery, but faced barriers such as treatment side effects, fear of movement, and lack of feedback. mHealth system could improve the quality of rehabilitation by providing visual and audio guidance, personalized and positive content, and remote monitoring by a physiotherapist. User requirements for an |

| Burg, M. A., Lopez, E. D., Dailey, A., Keller, M. E., & Prendergast, B. (2009). The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24(2), 467. DOI: 10.1007/s11606- 009-1012-y. United States of America. |

Qualitative research: Qualitative methods to explore the perspectives of minority breast cancer survivors on their follow-up care and survivorship care plans. Qualitative methods are useful for understanding the experiences, meanings, and contexts of people’s lives. Focus groups: Four focus groups with 32 minority breast cancer survivors living in a Southeastern urban area. Focus groups are a form of group interview that allows participants to interact with each other and share their views on a topic. Focus groups can generate rich and diverse data on people’s opinions, attitudes, and feelings. Purposive sampling: Purposive sampling to recruit eligible participants who were female breast cancer survivors between the ages of 18 and 65 whose active treatment for breast cancer was completed. Purposive sampling is a technique that selects participants based on specific criteria or characteristics that are relevant to the research question. Purposive sampling can enhance the validity and representativeness of the sample. |

Survivorship care plans (SCPs): These are documents that provide information on the cancer diagnosis, treatment, follow-up care, and psychosocial support for cancer survivors and their primary care providers. Explores the potential benefits and challenges of SCPs for minority breast cancer survivors. Minority breast cancer survivors’ experiences reports the findings of four focus groups with minority breast cancer survivors, mostly African American women, who shared their recall of information from their oncologists, their unmet needs and concerns, and their opinions on the ASCO SCP template for breast cancer. Primary care follow-up of cancer survivors: Discusses the implications of SCPs for improving the coordination and quality of care for cancer survivors in primary care settings, especially for minority and underserved populations. Identifies the gaps in knowledge and training for primary care physicians who care for cancer survivors. |

Female breast cancer survivors: All the participants were women who had completed active treatment for breast cancer and were between the ages of 18 and 65. Minority and mainly African American: Three out of four focus groups comprised only African American women; the fourth group included six African American women, one Hispanic woman and two Caucasian women. Living in a Southeastern urban area: The participants were recruited from members of the Sisters Network (a national African American organization with regional breast cancer support groups) and urban public health department outpatient clinics serving a high proportion of minority patients in a Southeastern city. |

Minority breast cancer survivors’ information needs: Survivors often have information gaps, confusion, and dissatisfaction with the communication from their oncologists and primary care providers. Minority-specific considerations, such as race-related side effects and support resources, should be taken into account when designing and delivering information to this population. Survivorship care plans as a potential tool for improving information transfer and coordination of care examines the concept and content of survivorship care plans (SCPs), which are portable records of tumour characteristics, treatments received, and follow-up guidelines meant to be completed by the oncologist and given to the survivor and their primary care provider. Assesses the reactions and opinions of minority breast cancer survivors on the SCP template from the Association of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and identifies the strengths and limitations of the SCP as a quality improvement tool. Discusses the system-level and provider-level challenges and opportunities for implementing SCPs in clinical practice. |

Information gaps: The survivors felt that they did not receive enough information from their oncologists about their cancer diagnosis, treatment, side effects, and follow-up care. They often had to seek information from other sources, such as the Internet, support groups, and other survivors. Psychosocial distress: The survivors experienced various physical and psychological side effects that were not anticipated or addressed by their oncologists. They also felt anxious and abandoned after completing treatment and wished they had more guidance on how to cope and prevent recurrence. Survivorship care plan feedback: The survivors liked the idea of having an SCP, but found the ASCO template too technical, generic, and limited. They suggested that the SCP should be more personalized, use plain language, and include more information on side effects, self-care, and resources. |

| Burke, N. J., Napoles, T. M., Banks, P. J., Orenstein, F. S., Luce, J. A., & Joseph, G. (2016). Survivorship care plan information needs perspectives of safety-net breast cancer patients. PloS one, 11(12), e0168383. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0 16 8383. United States of America. |

Community-university collaboration between the San Francisco Women’s Cancer Network (SFWCN) and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The collaboration aimed to identify the informational and structural challenges to treatment and survivorship for safety-net breast cancer patients, and to inform the content and delivery of appropriate and useful survivorship care plans (SCPs). Qualitative methods, specifically focus groups, to elicit the perspectives of low literacy, multi-lingual breast cancer patients on their information needs and preferences for SCPs. The focus groups were conducted in five languages (English, Spanish, Cantonese, Russian, and Tagalog) with women who were at least two years and no more than 15 years from their diagnosis. The focus groups were facilitated by bilingual, bicultural community organization staff who had undergone a half-day training with the university partners. Standard qualitative analysis techniques, including iterative data review, multiple coders, and “member checking”. | Survivorship care plans: SCPs are written documents that summarize the care received, disease characteristics, and follow-up plans for cancer survivors. Discusses the challenges and gaps in implementing SCPs for diverse and underserved populations and the recommendations from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and other organizations. Safety-net breast cancer patients: These are patients who receive care from providers who offer services regardless of ability to pay, and who have low health literacy, low English proficiency, and low income. Reports the findings from six focus groups conducted in five languages with African American, Latina, Russian, Filipina, White, and Chinese breast cancer patients who are at least two years and no more than 15 years from their diagnosis. Information needs and preferences: Identifies three themes that reflect the information needs and preferences of the focus group participants: 1) the need for information and education on the transition between “active treatment” and “survivorship”. 2) information needed (and often not obtained) from providers, such as screening, recurrence, side effects, reconstruction, and healthy lifestyle; and 3) perspectives on SCP content and delivery, such as referrals, symptom management, hereditary risk, family communication, and self-care strategies. |

The study engaged 38 participants with diverse characteristics to explore the information needs of safety-net breast cancer patients regarding survivorship care plans (SCPs). The participants, with a mean age of 61, represented various racial/ethnic backgrounds and educational levels. Notably, 36% reported an annual household income below $10,000. The findings emphasized a need for clear communication on the transition from active treatment to survivorship, highlighting confusion among participants. The study sheds light on structural issues within the healthcare context, such as fleeting relationships with providers and poor communication between oncology and primary care, underlying the reported information needs and care experiences. |

Need for information and education on the transition to survivorship: Women in the focus groups expressed confusion and a lack of clarity regarding the transition from "active treatment" to "survivorship." Despite being on ongoing treatments like Tamoxifen or other hormonal therapies, women found themselves categorized as in survivorship, leading to a discrepancy in understanding between patients and healthcare providers. Participants who did have an understanding of survivorship often gained this knowledge from community organizations and support groups rather than their healthcare providers. Information needed from providers Participants highlighted various areas where they lacked information from healthcare providers, contributing to a sense of uncertainty and anxiety. Five primary areas of information deficit were identified: Screening and Monitoring: Participants were unsure about the frequency and types of screenings they should undergo during survivorship. Recurrence: Women expressed fears and uncertainties about cancer recurrence, seeking guidance on recognizing symptoms and how to react. Healthy Lifestyle Choices: Participants desired guidance on healthy eating, physical activity, and managing the effects of cancer on their daily lives. |

Need for Information and Education on the Transition to Survivorship: Breast cancer survivors expressed confusion and a lack of clarity about the transition from active treatment to survivorship. The ongoing nature of treatments, such as hormonal therapies, created uncertainty about the categorization of survivorship. Participants suggested the need for new terms and highlighted the role of community organizations and support groups in providing information on survivorship. Information Needed (and Often Not Obtained) from Providers: Participants reported information deficits in key areas: Screening and Monitoring: Uncertainty about the frequency and types of screenings during survivorship. Recurrence: Fears and uncertainties about cancer recurrence, seeking guidance on symptoms and reactions. Side Effects and Pain: Lack of truthful information from providers, especially regarding hormonal treatments and prevalent side effects like lymphedema. Reconstruction: Insufficient information on breast reconstruction alternatives, timing, and post-surgery care. Healthy Lifestyle Choices: Desire for guidance on healthy eating, physical activity, and managing the effects of cancer on daily life. Perspectives on SCP Content and Delivery: Participants expressed specific |

| Costas-Muñiz, R., Garduño Ortega, O., Hunter Hernández, M., Morales, J., Castro-Figueroa, E. M., & Gany, F. (2021). Barriers to psychosocial services use for Latina versus non-Latina white breast cancer survivors. American journal of psychotherapy, 74(1), 13- 21. |

Retrospective cross-sectional design and was conducted at a single comprehensive cancer center located in New York City (NYC). Participants: The study included adult survivors aged 21 or older in remission from breast cancer. The sample consisted of 409 Latinas and 5146 non-Latina Whites who had received cancer care at the center between 2009 and 2014. The selection involved including all 409 Latinas and a random 10% sample of non-Latina Whites. Data Collection: Medical records of individuals treated between 2009 and 2014 were reviewed. Eligible participants received a mailed questionnaire packet covering demographics, attitudes toward and history of using psychosocial services, and perceived barriers to use. Implied consent was obtained through the completion of the anonymous survey. Demographic variables collected included age, education, religion, marital status, socioeconomic status, family composition, living situation, employment status, ethnicity, race, language preference, birthplace, and years of living in the United States. Psychosocial services variables encompassed histories of usage, preferences for services, and types of mental health professionals involved. Barriers variables included 14 patient-related barriers and six physician- or system-related barriers. Data Analysis: SPSS 19 software was utilized for statistical analyses. |

Access and utilization of psychosocial services among breast cancer survivors, with a specific emphasis on understanding the barriers faced by Latina and non-Latina White individuals. The study aims to explore disparities in psychosocial outcomes, investigate the reasons behind the lower rates of psychosocial service utilization among Latinos, and examine the self-reported barriers to accessing psychosocial services among breast cancer survivors. Additionally, the study explores the associations between these barriers and the actual use of psychosocial services following a cancer diagnosis. |

Adult breast cancer survivors aged 21 or older, in remission from their diagnosis, and received care at a comprehensive cancer center in New York City between 2009 and 2014. The sample consists of 409 Latina and 5146 non-Latina White individuals. The selection method involved including all Latina participants and a random 10% sample of non-Latina Whites, totaling 409 and 5146, respectively. The study explores a range of demographic characteristics, including marital status, socioeconomic status, family composition, living situation, employment status, ethnicity, race, language preference, birthplace, and years of living in the United States. It also considers medical factors such as the time since diagnosis and remission status. Due to a small sample size, separate analyses for Latina and non-Latina White subgroups were not conducted. The response rate for the study was 30%, and participants provided implied consent by completing an anonymous survey after reviewing a form detailing the study, their rights, and potential benefits. These participant characteristics offer a comprehensive view of the study population, crucial for interpreting the findings on psychosocial outcomes and barriers to accessing psychosocial services among breast cancer survivors. |

Disparities in Psychosocial Outcomes: The study delves into the disparities in psychosocial outcomes, specifically examining how Latina individuals living with breast cancer experience poorer quality of life and higher rates of depression compared to non-Latino Whites. Utilization of Psychosocial Services: The research investigates the patterns of access to psychosocial services among breast cancer survivors. It explores the utilization rates of psychological, psychiatric, and other psychosocial interventions, with a particular focus on the differences between Latina and non-Latina White individuals. Barriers to psychosocial services use: The study aims to identify and understand the barriers that hinder the use of psychosocial services, especially among Latina breast cancer survivors. It acknowledges that despite the need for mental health support, there are obstacles preventing individuals, particularly Latinos, from receiving appropriate services. Unique Concerns of Latino Individuals: Latinos often face unique challenges, including socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic issues, impacting their access to psychosocial and mental health services. The study aims to uncover and comprehend these unique concerns that may contribute to disparities in mental health outcomes. Financial Impact of Cancer Diagnosis: The study explores the association between a cancer diagnosis, worsened mental health, and its impact on income, particularly emphasizing the challenges faced by Latinos in comparison to non-Latino Whites. Psychosocial Service Use Disparities: The study highlights the disparities in the use of psychosocial services, revealing that Latinos are less likely to receive these services than non-Latino Whites. It explores the potential reasons for this gap, encompassing patient-, provider-, and system-related barriers. |

Ethnic Disparities in Psychosocial Service Barriers: Latinas, among those needing psychosocial services, face specific barriers. Barriers include language, cultural understanding, and perceived cost. Prior Study on Psychosocial Service Disparities: Previous research showed differences in availability and acceptability. Non-Latina Whites are more likely to have contact with social workers and receive psychotropic medication. Latinas are more likely to receive spiritual counselling. Commonly Cited Barriers to Psychosocial Care: Beliefs in self-reliance, a desire to return to normalcy, and reliance on family and friends. Key reasons survivors decline services. Predictors of Lack of Psychosocial Service Use: Desire to return to normalcy. Lack of understanding about therapy benefits. Not knowing where to receive services. Mental health stigma and beliefs about distress normalcy. Concerns about cultural understanding by counsellors. Discomfort with medical interpreters. The gap in National Clinical Guidelines: Lack of specialized recommendations for culturally diverse patients. Need for guidelines addressing distress screening and management for diverse populations. Importance of Educational Interventions: Need for educational programs at individual, provider, and institutional levels. Programs to increase awareness, normalize psychosocial service use, and provide information. Emphasis on cultural competency training for providers. Call for System-Level Interventions: Recommendations for institutional policies promoting cultural competency. Support for diverse, bilingual staff. Translation of materials and language assistance programs. |

| Crawford, J., Frisina, A., Hack, T., & Parascandalo, F. (2015). A peer health educator program for breast cancer screening promotion: Arabic, Chinese, South Asian, and Vietnamese immigrant women’s perspectives. Nursing Research and Practice, 2015. |

Participatory action research (PAR): This is a collaborative and reflective approach that involves the participants as co-researchers in the study. The researchers used PAR to explore the experiences of immigrant women with a peer health educator program that promoted breast health and screening. The researchers drew on the critical social theory of Freire and Fals Borda to guide their PAR process. Qualitative methods: The researchers used focus groups and one-on-one interviews to collect data from 82 immigrant women from four cultural groups: Arabic, Chinese, South Asian, and Vietnamese. The researchers used a semistructured interview guide with open-ended questions to elicit the perspectives of the participants. The focus groups and interviews were conducted in the preferred language of the participants by immigrant women facilitators who were native speakers of the respective language. Thematic content analysis: The researchers used this method to analyze the transcribed and translated data. |

Immigrant women’s experiences with a peer health educator program: The main topic of interest is how immigrant women perceived and valued the program, which aimed to reduce barriers and provide access to breast health information and mammography screening. The researchers explored the benefits and challenges of the program, as well as the strengths and areas of improvement. Breast cancer prevention and screening: A related topic of interest is how immigrant women learned about breast health, risk reduction, breast cancer, and screening services through the program. The researchers examined how the program influenced immigrant women’s knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors regarding breast cancer prevention and screening. Public health actions and implications: Another related topic of interest is how the researchers used the findings from the study to inform and improve the public health program and practice. The researchers reported on the public health actions that were taken based on the recommendations of the immigrant women. They also discussed the implications of the study for public health policy, research, and education. |

Reports on a study that involved 82 immigrant women from four different cultural groups: Arabic, Chinese, South Asian, and Vietnamese. The participants were recruited from a peer health educator program that provided access to breast health information and mammography screening. The participants were 40 years of age and older, and had attended a women’s health session or been accompanied to breast screening by a peer health educator. The majority of participants were Arabic and South Asian immigrant women. Two-thirds of participants were 50 years of age and older. The mean number of years in Canada was 11 years, with a range of less than one year to 36 years. Over 50% of women resided in Canada for 10 years or less. The majority of immigrant women preferred to communicate in their native language. |

Identity and acculturation: The study explores how immigrant women from different cultural backgrounds adapt to their new host country and how they perceive their health and well-being. The study also examines how the peer health educator program helps immigrant women develop a sense of identity and belonging in Canada. Culture and health literacy: The study highlights the importance of cultural competence and health literacy in promoting breast cancer prevention and screening among immigrant women. The study shows how the peer health educator program provides culturally appropriate and linguistically accessible information and support to immigrant women, and how this enhances their knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding breast health. Psychosocial care and empowerment: The study demonstrates the role of peer health educators and social networks in providing psychosocial care and empowerment to immigrant women. The study reveals how the peer health educator program fosters a caring and trusting environment, where immigrant women can share their experiences, feelings, and concerns, and receive emotional and practical support. The study also shows how the peer health educator program empowers immigrant women to take charge of their own health and access healthcare services. |

Immigrant women’s experiences with the peer health educator program: Explored how Arabic, Chinese, South Asian, and Vietnamese immigrant women in Canada perceived a public health program that used peer health educators and multiple strategies to promote breast health and mammography screening. Participatory action research and qualitative methods to collect and analyze data from 82 immigrant women who participated in focus groups and interviews. Four dominant themes emerged from the data: Identified four main themes that reflected immigrant women’s experiences with the program: (1) Breast Cancer Prevention, which focused on learning about breast health, risk reduction, and screening services; (2) Social Support, which centered on the attributes of the peer health educator and the support she provided, as well as the support from other women in the community; (3) Screening Services Access for Women, which highlighted immigrant women’s perceptions of the program as a whole and its connections to other health services, as well as the role of family physicians; and (4) Program Enhancements, which suggested ways to improve the program in terms of content, process, and dissemination. Implications for public health practice and research: Discussed how the findings provided insights into the strategies used to promote breast health and mammography screening among immigrant women, as well as the barriers that persist, such as the lack of information and recommendation from family physicians. |

| Green, E. K., Wodajo, A., Yang, Y., Sleven, M., & Pieters, H. C. (2018). Perceptions of support groups among older breast cancer survivors: “I've heard of them, but I've never felt the need to go”. Cancer Nursing, 41(6), E1 |

Qualitative methodology: Uses grounded theory, an inductive, qualitative methodology informed by constructivism, to explore how breast cancer survivors 65 years and above perceived professionally-led, in-person support groups. Grounded theory is a method that aims to generate theory from data through systematic coding, constant comparison, and memo-writing. Constructivism is a perspective that assumes that reality is socially constructed, and multiple interpretations are possible Individual interviews: Data from individual, in-depth interviews with 54 women who were at least 65 years old when they were diagnosed with loco-regional breast cancer and who initiated anti-hormonal treatment. The interviews were conducted by the senior author, an experienced qualitative interviewer, in a private place of the participant’s choosing. The interviews lasted an average of 97.2 minutes and covered topics such as support groups, decision-making, and anti-hormonal treatment. |

Support groups: Aims to describe how older breast cancer survivors perceived professionally-l ed, in-person support groups, and why they did or did not attend them. Support groups are a type of psychosocial intervention that can provide emotional, informational, and instrumental support to cancer survivors. Reviews the literature on the benefits and challenges of support groups, and the factors that influence participation in them. Anti-hormonal treatment: Focuses on the decision-making processes related to persistence with anti-hormonal treatment by older breast cancer survivors in the posttreatment phase. Anti-hormonal treatment is a type of oral medication that can reduce the risk of recurrence and mortality for hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Examines the role of support groups and other sources of support in facilitating adherence to anti-hormonal treatment. |

Age: women who were at least 65 years old when they were diagnosed with breast cancer. The average age of the participants was 71.9 years at diagnosis. Ethnicity: Reports that most participants self-identified as white (n=44), while the rest did not specify their ethnicity. Education: Reports that most participants were at least college graduates (n=38), while the rest had lower levels of education. Support: Most participants identified their husband (n=21) or daughter (n=17) as their main support person and spoke with friends daily (n=43). All participants lived independently either with a spouse (n=24) or alone (n=23). Cancer stage: Participants were diagnosed with loco-regional (Stage I, II or III) breast cancer, and initiated anti-hormonal treatment. Sample consisted of two equal groups: 27 women continuing with an anti-hormonal treatment and 27 women who had prematurely discontinued the medication within the 15 months preceding the interview. |

Cultural differences in support-seeking: Support-seeking literature suggests differences among individuals from different cultural backgrounds, and that their sample mostly included Caucasian women. This implies that culture may influence how older breast cancer survivors perceive and utilize support groups and that more research is needed to capture the diversity of experiences and preferences among different cultural groups. Identity as a cancer survivor: Discusses how participants resisted an identity as a cancer patient, and how they wanted to move on from the cancer experience and return to their life before cancer. This suggests that attending a support group may challenge their sense of identity and agency and that they may not see themselves as belonging to a community of cancer survivors. Psychosocial care options: Highlights the importance of providing integrated psychosocial services for cancer survivors post-treatment, and suggests that support groups are one of the possible options. Reviews the literature on the benefits and challenges of various types of support groups, such as peer or professionally led, online or in-person, and psycho-educational or emotional. |

Support groups are underutilized by older breast cancer survivors: Interviewed 54 women who were 65 years or older when they were diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. Only two of them were attending a professionally-led, in-person support group at the time of the interview. Most of them had negative assumptions about support groups and did not see themselves as the type of person who would benefit from them. Support groups are perceived as a place for emotional support only: Most participants thought that support groups were designed to provide emotional support for women who did not have other sources of support or who had more advanced or severe cancer. They did not associate support groups with informational or instrumental support, which they valued more and sought from other informal networks or trusted physicians. Support groups are seen as a reminder of cancer when participants want to move on: Participants wanted to return to their normal lives after completing their primary treatment and starting their anti-hormonal medication. They did not want to keep cancer in their lives or face the negative emotions of other group members. They also felt that their concerns were not worthy of or suitable for support groups compared to those of other women with worse prognoses. |

| Gripsrud, B. H., Brassil, K. J., Summers, B., Søiland, H., Kronowitz, S., & Lode, K. (2016). Capturing the experience: Reflections of women with breast cancer engaged in an expressive writing intervention. Cancer Nursing, 39(4), E51. |

Longitudinal design: The study followed a descriptive and comparative design, collecting data from participants at two time points: baseline and one year after surgery. The aim was to explore and describe the experience and feasibility of expressive writing for women with breast cancer following mastectomy and reconstructive surgery. Expressive writing intervention: The study used a therapeutic method developed by James W. Pennebaker, which involves writing about one’s deepest thoughts and feelings about a traumatic or stressful life event. The participants were asked to undertake four episodes of expressive writing at home, either by hand or electronically, according to an instruction tailored to breast cancer experiences (Appendix A). Semi-structured interviews: The study used a loosely structured interview guide to explore the women’s experiences with the intervention (Appendix B). The interviews were conducted by the researchers either in person or by phone and lasted for one to two hours. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Experiential thematic analysis: The study used a qualitative method to analyze the interview data, which involved identifying meaningful units, generating descriptive codes, and developing themes that captured the manifest content of the participants’ experiences. |

The experience of expressive writing: The study aimed to explore and describe how the participants felt and thought about the writing process, what challenges and benefits they encountered, and how the writing affected their emotional and physical well-being. The experience of breast cancer, mastectomy and reconstruction: The study aimed to investigate how the participants coped with the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, how they perceived and related to their bodies and breasts, and how they adjusted to the changes and challenges in their psychosocial and cultural contexts. The comparison of data across countries and time points: The study aimed to conduct comparative data analyses between the US and Norway, and between baseline and one-year follow-up, to examine the similarities and differences in the participants’ experiences and outcomes. |

Women with breast cancer: The study enrolled women who had been diagnosed with breast cancer and had undergone mastectomy, either with immediate or delayed reconstructive surgery. Diverse age and ethnicity: The study included women who were aged 18 and older, and who had different ethnic and cultural backgrounds. The US sample consisted of 7 women, of whom 4 were Caucasian, 2 were African American, and 1 was Asian. The Norwegian sample consisted of 14 women, of whom 13 were Caucasian and 1 was Asian. English speakers and writers: The study required the participants to be able to read and write English, as the intervention and the interviews were conducted in English. | Culture: explores the cross-cultural differences between American and Norwegian women with breast cancer, and how expressive writing may be influenced by their cultural backgrounds. For example, one participant from North-East Asia had a different response to the writing intervention than the other six participants, who were more comfortable with sharing their emotions and stories. Discusses how breast cancer and mastectomy can affect the meaning of breasts in different social and cultural contexts. Identity: examines how expressive writing can help women with breast cancer to reconstruct their identities after losing a part of their body and facing a life-threatening illness. Writing can provide a way of affirming one’s decisions, values, and strengths, as well as coping with the changes and challenges brought by the disease. Shows how writing can facilitate existential learning and transformation for cancer patients. Psychosocial care: Evaluates the feasibility and benefits of expressive writing as a psychosocial intervention for women with breast cancer. Writing can have positive effects on physical and emotional well-being, quality of life, fatigue, post-traumatic stress, and negative thought patterns. Highlights the importance of timing, setting, and instruction for the implementation of the intervention. Expressive writing can be a valuable tool for healthcare providers to introduce into the plan of care for patients with breast cancer. |

Writing as process: The participants described how they organized their writing, how much time they spent, and how they felt during and after writing. They also expressed awareness of the readership of their texts, such as the researchers, their families, or other women with breast cancer. Writing as a means to help others: The participants expressed a desire to help others through their writing, either by sharing their stories, providing support, or contributing to research. They also hoped that their writing would have a positive impact on the readers. Writing as therapeutic: The participants reported various benefits of writing, such as processing their emotions, validating their decisions, realizing their strengths, and coping with their challenges. They also identified some difficulties or discomforts of writing, such as recalling painful memories, confronting unpleasant feelings, or revealing intimate details. A divergent case: One participant had a different cultural background and a different response to writing. She found writing to be painful and scary, and she avoided thinking or talking about her illness. She also did not want to share her writing with anyone. However, she also recognized some positive aspects of writing, such as clarifying her worries and finding solutions. |

| Haq, R., Heus, L., Baker, N. A., Dastur, D., Leung, F. H., Leung, E., ... & Parsons, J. A. (2013). Designing a multifaceted survivorship care plan to meet the information and communication needs of breast cancer patients and their family physicians: results of a qualitative pilot study. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 13(1), 1-13. Canada |