Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Deep Learning Architectures

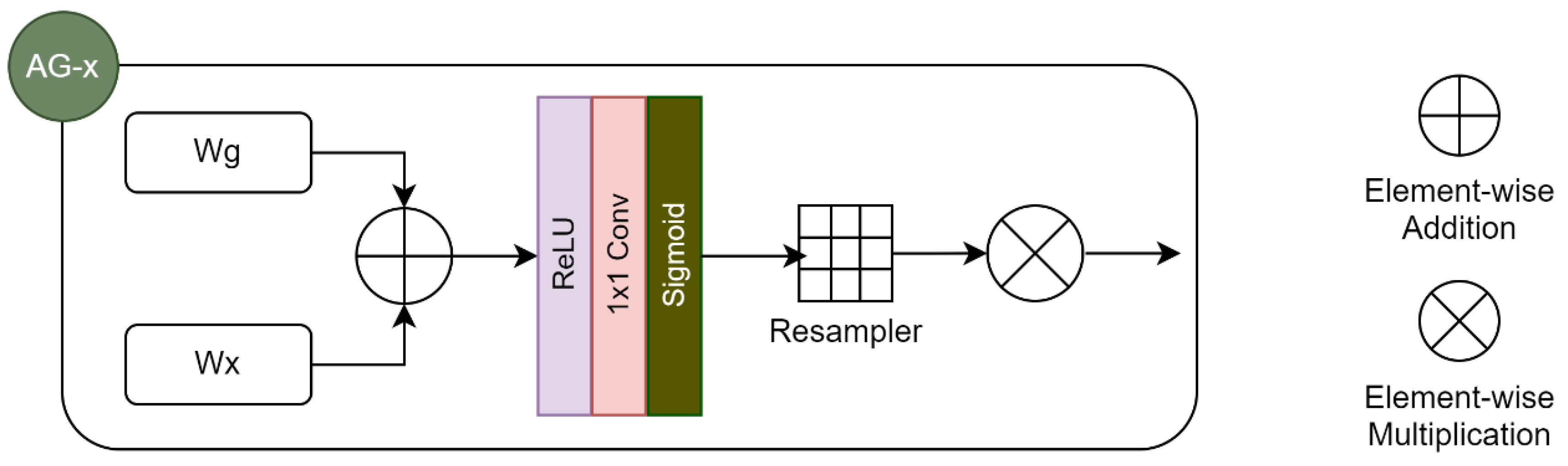

2.2. Attention Mechanisms

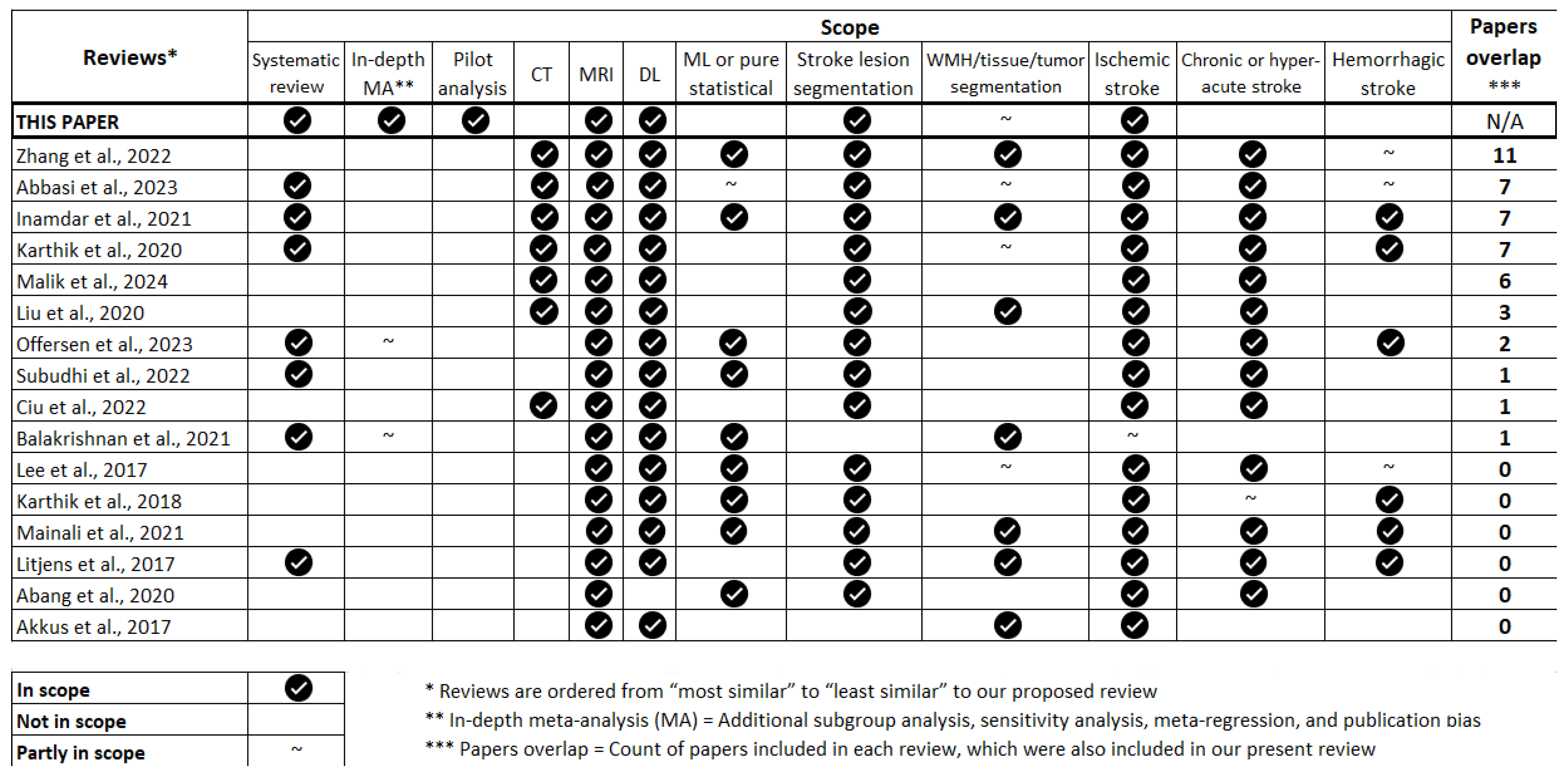

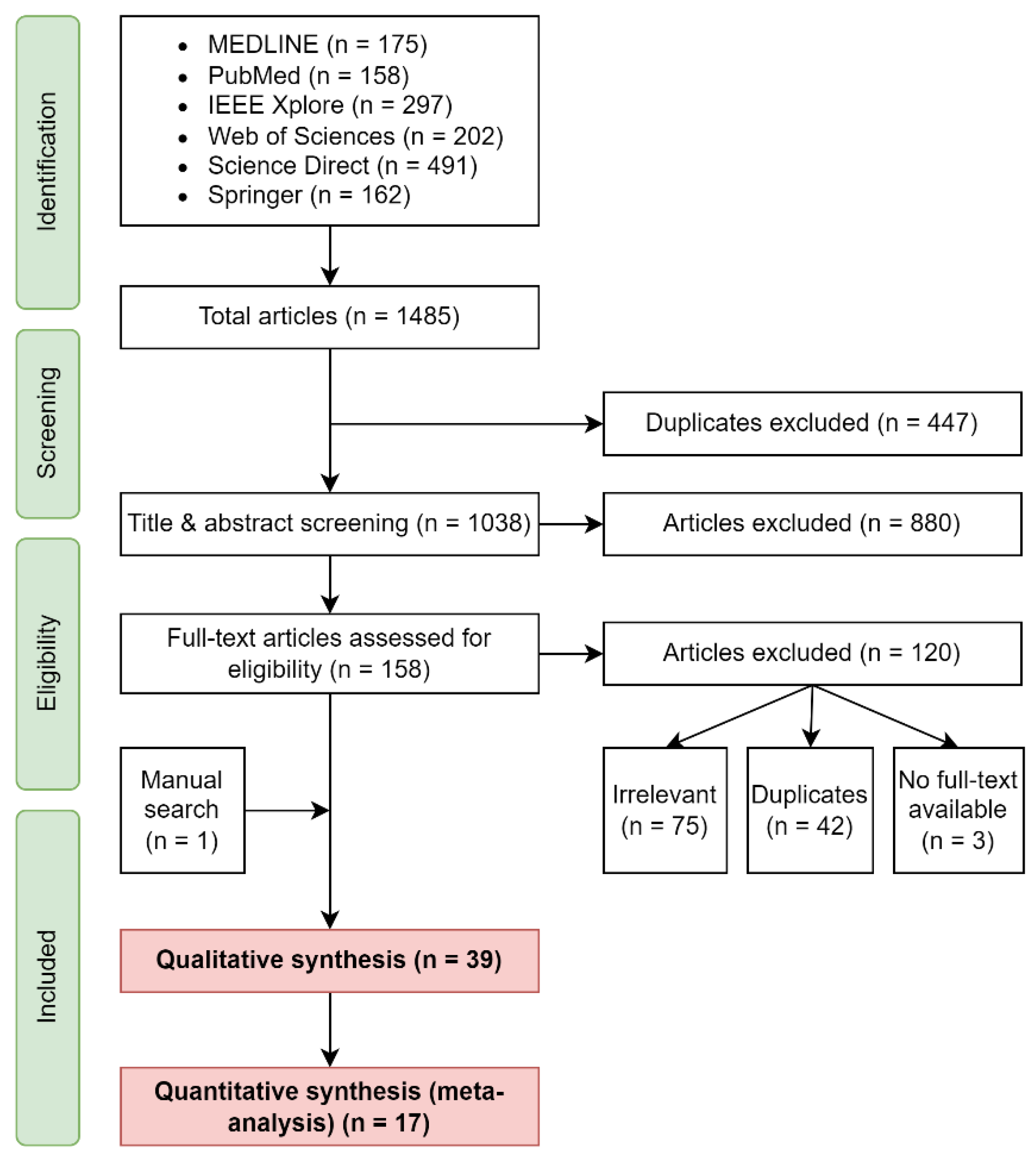

3. Materials & Methods

3.1. Protocol Registration

3.2. Search Strategy

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

3.4. Data Extraction

3.5. Data Analysis

3.6. Publication Quality Analysis

3.7. Pilot Analysis

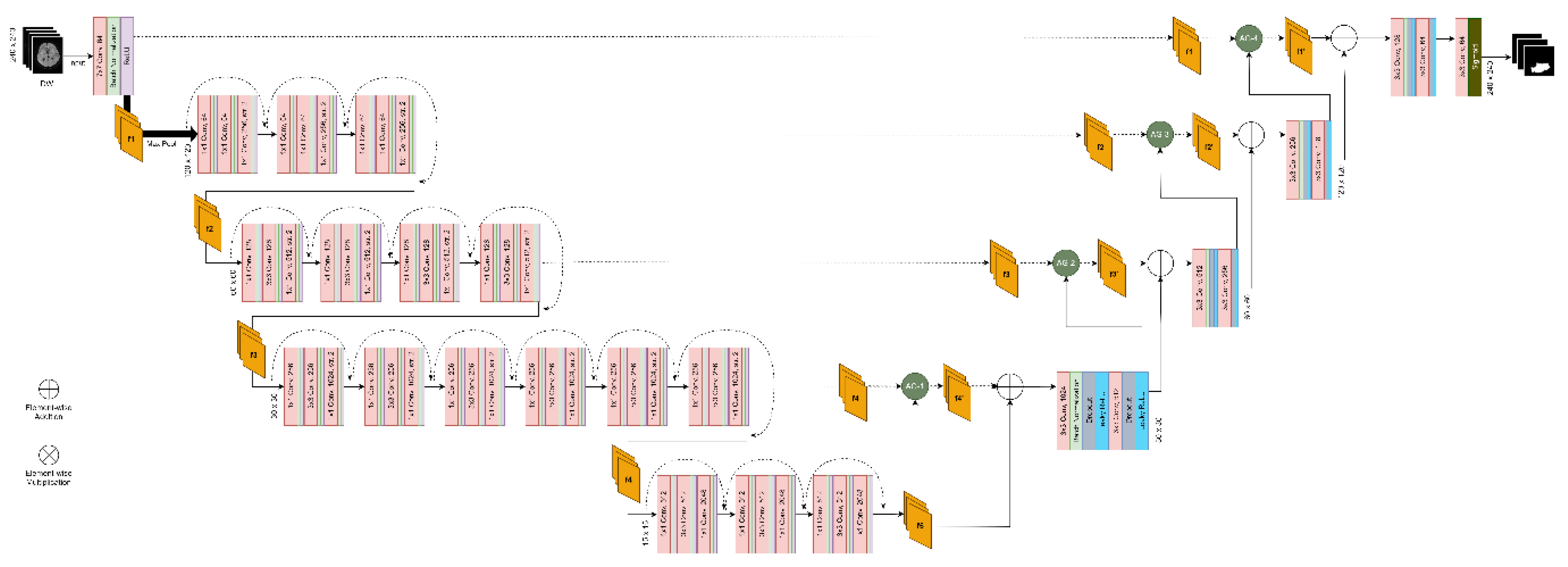

-

Proposing an architecture that leverages the findings of our systematic review in terms of best development practices:

- ○

- Use 2D model with image-wise training

- ○

- Increase network depth while leveraging the power of skip connections by combining U-Net and ResNet

-

Conducting multiple experiments (24 in total) assessing segmentation performance in different scenarios:

- ○

- With versus without attention mechanisms

- ○

- Using a compound loss function versus a region-based loss function

- ○

- Using input images of a single modality (DWI) versus input images of multiple modalities

3.7.1. Dataset

3.7.2. Data Pre-Processing

- Intensity-based normalization using Min-Max scaling

- Intensity-based skull-stripping using BET2 (performed by challenge organizers)

- Rigid co-registration to the FLAIR sequences (performed by challenge organizers)

3.7.3. Segmentation Architecture, Model Training and Evaluation

4. Results

4.1. Search Results

4.2. Sample Characteristics

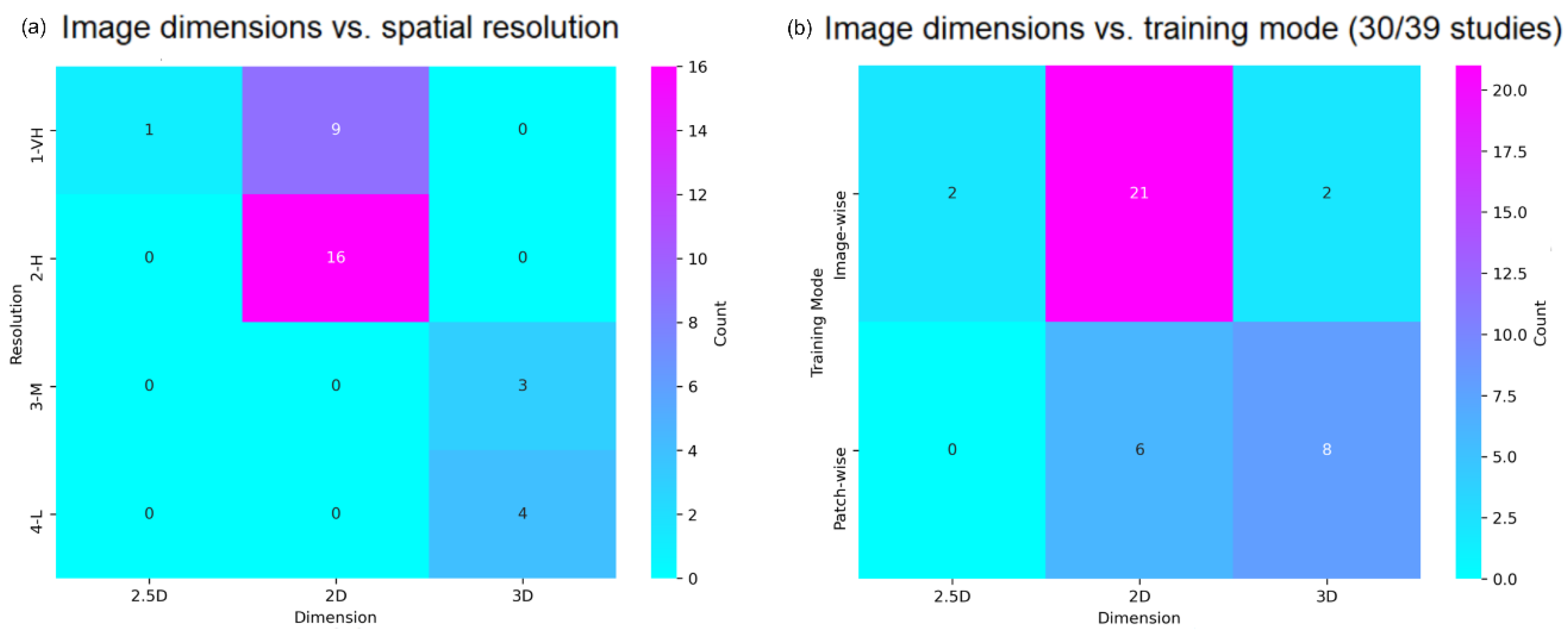

4.3. Imaging Acquisition and Manipulation

4.4. Data Pre-Processing

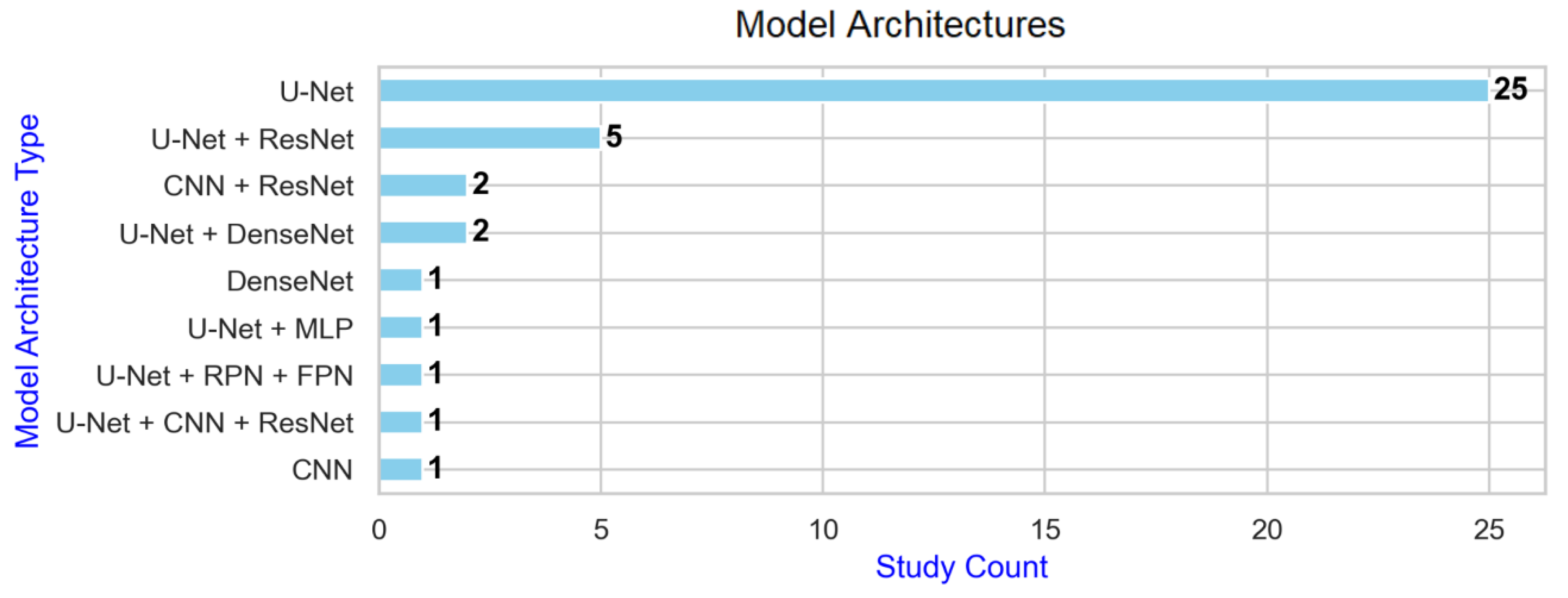

4.5. Deep Learning Architectures

4.6. Performance and Generalisability

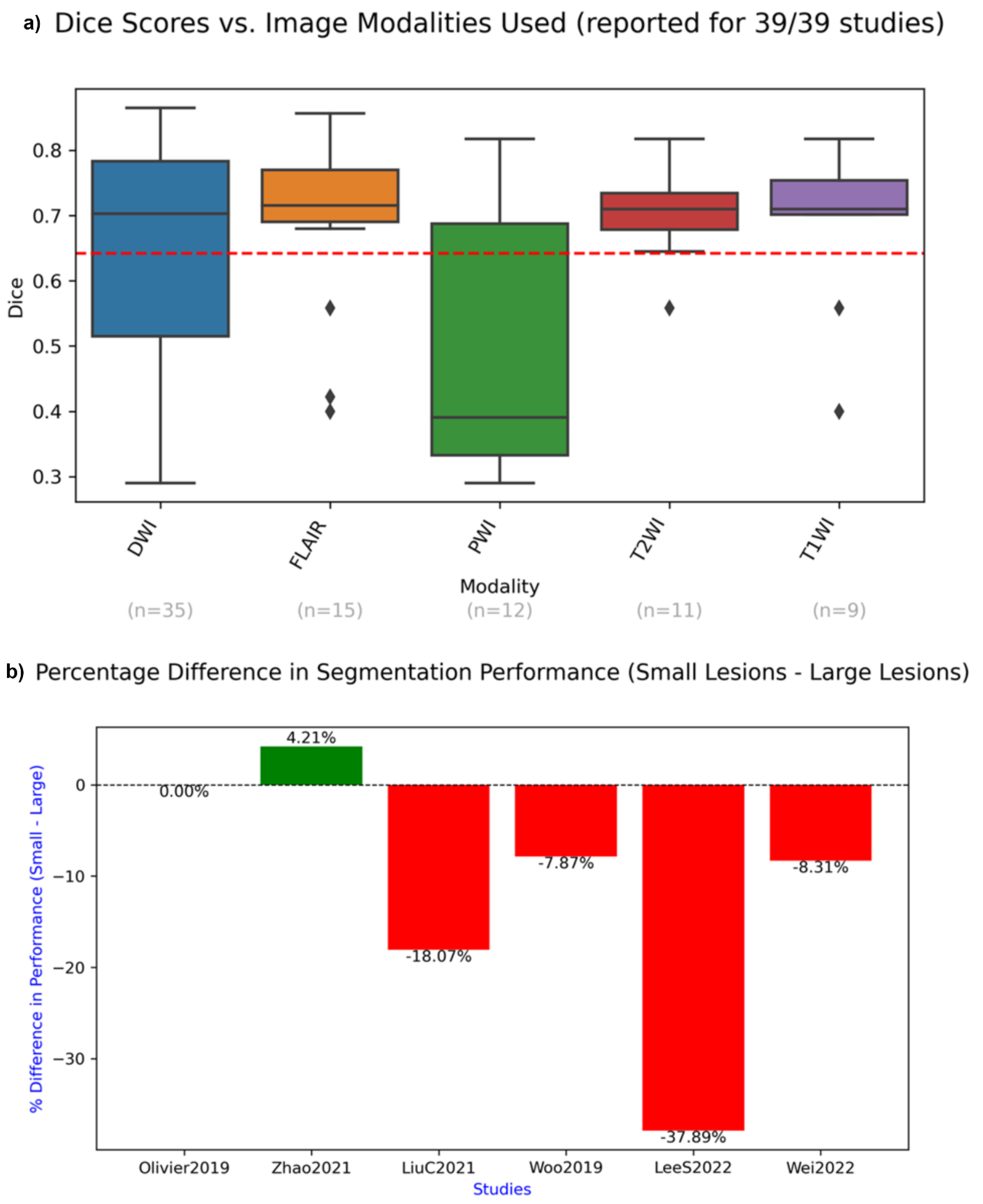

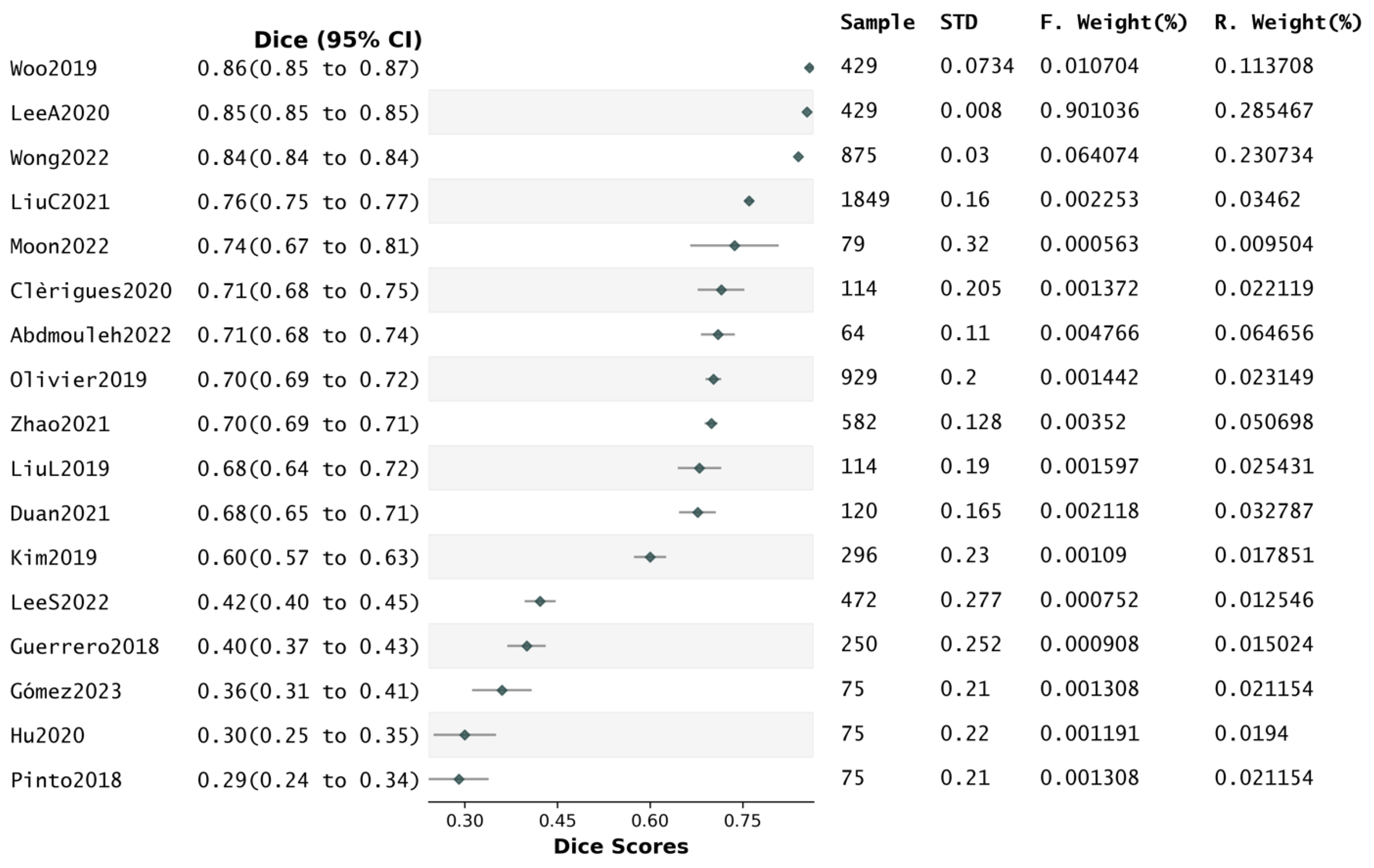

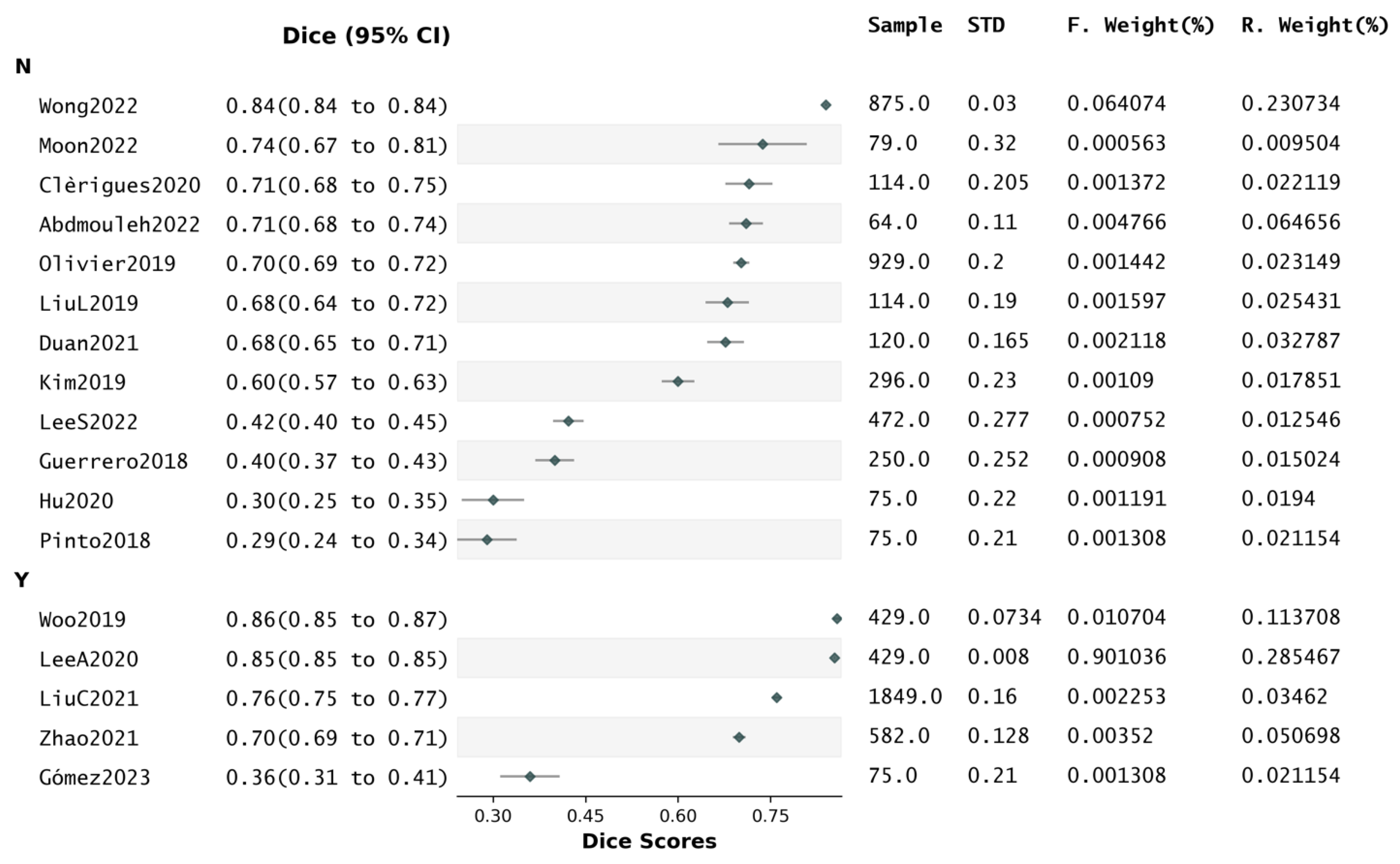

4.7. Reported Dice Scores and Segmentation Quality

4.8. Influence of Attention on Dice Scores

4.9. Risk of Bias Assessment

4.10. Pilot Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

- Liu Z. et al. [67] proposed a ResNet and a global convolution network-based (GCN) encoder-decoder. Each modality was concatenated to a three-channel image, then passed as input image to a series of residual blocks. The output of each block was then passed to its corresponding up-sampling layer using a skip connection incorporating a GCN and a boundary refinement layer

- Liu L. et al.‘s “MK-DCNN” [95] consisted of two sub-DenseNets with different convolution kernels, aiming to extract more image features than with a single kernel by combining low and high resolution

- Wu et al.’s W-Net [87] tackled variability in lesion shape by trying to capture both local and global features in input scans. A U-Net first captures local features, which then go through a Boundary Deformation Module, then finally through a Boundary Constraint Module that uses dilated convolution to ensure pixels neglected in previous layers can also contribute to the final segmentation

- Lucas et al. [100] added to their U-Net skip connections around each convolution block, besides those linking encoder-decoder layers

- Karthik et al. [101] embedded multi-residual attention blocks in their U-Net, hence allowing the network to use auxiliary contextual features to strengthen gradient flow between blocks and prevent vanishing gradient issues

- Vupputuri et al. [102] used self-attention through multi-path convolution, aiming to compensate for information loss, while using weighted average across filters to provide more optimal attention-enabled feature maps

- Ou. et al. [103] used lambda layers, which work by transforming intra-slice and inter-slice context around a pixel into linear functions (or "lambdas"), which are then applied to the pixel to produce enhanced features. As opposed to attention, lambdas do not give “weights” to pixels

- Findings drawn from reported performance metrics (e.g., Dice) must be carefully interpreted, as performance depends on the quality of the data being used, which was variable across studies

- Results of this review may be skewed towards acute stroke (rather than subacute)

- Over-reliance on specific public datasets, which may have selection biases, may limit the generalisability of the research findings, as reported results may not fully represent all possible clinical scenarios

- Findings in terms of segmentation of small versus large lesions are slightly flawed, due to the various ways in which these two categories were defined across studies

- Data augmentation helped reduce overfitting by increasing the size of the training data, but effects of bias cannot be balanced-out by increasing the sample size by repetition [62]

5.2. Pilot Analysis

6. Study Limitations

- Only articles published in (or translated to) English that were accessible via institutional login were reviewed. Accordingly, relevant papers may have been missed

- Relevant papers may have been missed as a result of incongruences between search terms and article keywords in the various databases

- Since most of the included studies were not longitudinal, this review lacks an assessment of long-term patient outcomes, which is an essential factor in validating the clinical relevance and predictive value of segmentation algorithms

- While the review outlines the impact of lesion size on segmentation performance, the pilot analysis does not specifically assess how algorithms can be optimized for lesions of varying sizes

7. Conclusions and Future Works

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsao, C. W., Aday, A. W., Almarzooq, Z. I., Anderson, C. A. M., Arora, P., Avery, C. L., Baker-Smith, C. M., Beaton, A. Z., Boehme, A. K., Buxton, A. E., Commodore-Mensah, Y., Elkind, M. S. V., Evenson, K. R., Eze-Nliam, C., Fugar, S., Generoso, G., Heard, D. G., Hiremath, S., Ho, J. E., … Martin, S. S. (2023). Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 147(8). [CrossRef]

- Saka, O.; McGuire, A.; Wolfe, C. Cost of stroke in the United Kingdom. Age and Ageing 2008, 38, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, W.; Dong, P.; Xia, Y.; Wang, S. D-UNet: A Dimension-Fusion U Shape Network for Chronic Stroke Lesion Segmentation. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2021, 18, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Petzsche, M. R., de la Rosa, E., Hanning, U., Wiest, R., Valenzuela, W., Reyes, M., Meyer, M., Liew, S.-L., Kofler, F., Ezhov, I., Robben, D., Hutton, A., Friedrich, T., Zarth, T., Bürkle, J., Baran, T. A., Menze, B., Broocks, G., Meyer, L., … Kirschke, J. S. (2022). ISLES 2022: A multi-center magnetic resonance imaging stroke lesion segmentation dataset. Scientific Data, 9(1), 762. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, E.H. A new penumbra: transitioning from injury into repair after stroke. Nature Medicine 2008, 14, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.W.M.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Medical Image Analysis 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres, P. (2020). Introduction to Neural Network Models of Cognition (NNMOC). https://com-cog-book.github.io/com-cog-book/features/cov-net.html.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep Learning. MIT Press. http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Abang Isa, A.M.A.A.; Kipli, K.; Mahmood, M.H.; Jobli, A.T.; Sahari, S.K.; Muhammad, M.S.; Chong, S.K.; AL-Kharabsheh, B.N.I. A Review of MRI Acute Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation. International Journal of Integrated Engineering 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesamian, M.H.; Jia, W.; He, X.; Kennedy, P. Deep Learning Techniques for Medical Image Segmentation: Achievements and Challenges. Journal of Digital Imaging 2019, 32, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger O., Fischer, P., Brox T. (2015). U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In J. and W. W. M. and F. A. F. Navab Nassir and Hornegger (Ed.), Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015. Pp. 234–241, Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Lundervold, A.S.; Lundervold, A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Zeitschrift Für Medizinische Physik 2019, 29, 102–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cheng, J.; Quan, Q.; Wu, F.-X.; Wang, Y.-P.; Wang, J. A survey on U-shaped networks in medical image segmentations. Neurocomputing 2020, 409, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2016). Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 770–778. [CrossRef]

- Surekha, Y.; Koteswara Rao, K.; Lalitha Kumari, G.; Ramesh Babu, N.; Saroja, Y. Empirical Investigations To Object Detection In Video Using ResNet-AN Implementation Method. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 2022, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.-X.; Pan, Y.; Wang, J. Deep convolutional neural network for automatically segmenting acute ischemic stroke lesion in multi-modality MRI. Neural Computing and Applications 2020, 32, 6545–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veit, A., Wilber, M., & Belongie, S. (2016). Residual Networks Behave Like Ensembles of Relatively Shallow Networks. [CrossRef]

- Milletari, F., Navab, N., & Ahmadi, S.-A. (2016). V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation. 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), 565–571. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, L.; Lou, W.; Abrigo, J.M.; Mok, V.C.T.; Chu, W.C.W.; Wang, D.; Shi, L. Automatic Segmentation of Acute Ischemic Stroke From DWI Using 3-D Fully Convolutional DenseNets. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2018, 37, 2149–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diganta, M. (2020). Attention Mechanisms in Computer Vision: CBAM. Https://Blog.Paperspace.Com/Attention-Mechanisms-in-Computer-Vision-Cbam.

- Schlemper, J.; Oktay, O.; Schaap, M.; Heinrich, M.; Kainz, B.; Glocker, B.; Rueckert, D. Attention gated networks: Learning to leverage salient regions in medical images. Medical Image Analysis 2019, 53, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takyar, A. (2021). How Attention Mechanism’s Selective Focus Fuels Breakthroughs in AI. https://Www.Leewayhertz.Com/Attention-Mechanism/.

- Gómez S, Mantilla D, Rangel E, Ortiz A, Vera DD, Fabio Martínez Carrillo. A deep supervised cross-attention strategy for ischemic stroke segmentation in MRI studies. Biomedical physics & engineering express. 2023 Apr 5;9(3):035026–6. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J., Shen, L., Albanie, S., Sun, G., & Wu, E. (2017). Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. https://arxiv.org/abs/1709.01507. [CrossRef]

- Woo, I.; Lee, A.; Jung, S.C.; Lee, H.; Kim, N.; Cho, S.J.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Sunwoo, L.; Kang, D.-W. Fully Automatic Segmentation of Acute Ischemic Lesions on Diffusion-Weighted Imaging Using Convolutional Neural Networks: Comparison with Conventional Algorithms. Korean Journal of Radiology 2019, 20, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Woo, I.; Kang, D.-W.; Jung, S.C.; Lee, H.; Kim, N. Fully automated segmentation on brain ischemic and white matter hyperintensities lesions using semantic segmentation networks with squeeze-and-excitation blocks in MRI. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2020, 21, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-F., Hsu, J., Xu, X., Ramachandran, S., Wang, V., Miller, M. I., Hillis, A. E., Faria, A. v, Wintermark, M., Warach, S. J., Albers, G. W., Davis, S. M., Grotta, J. C., Hacke, W., Kang, D.-W., Kidwell, C., Koroshetz, W. J., Lees, K. R., Lev, M. H., … investigators, T. S. and V. I. (2021). Deep learning-based detection and segmentation of diffusion abnormalities in acute ischemic stroke. Communications Medicine, 1(1), 61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. (2021, October). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Linares-Espinós E, Hernández V, Domínguez-Escrig JL, Fernández-Pello S, Hevia V, Mayor J, et al. . (2018). Methodology of a systematic review. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed). 42(8):499-506. [CrossRef]

- Maier, O., Menze, B. H., von der Gablentz, J., Häni, L., Heinrich, M. P., Liebrand, M., Winzeck, S., Basit, A., Bentley, P., Chen, L., Christiaens, D., Dutil, F., Egger, K., Feng, C., Glocker, B., Götz, M., Haeck, T., Halme, H.-L., Havaei, M., … Reyes, M. (2017). ISLES 2015 - A public evaluation benchmark for ischemic stroke lesion segmentation from multispectral MRI. Medical Image Analysis, 35, 250–269. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bentley, P.; Mori, K.; Misawa, K.; Fujiwara, M.; Rueckert, D. DRINet for Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2018, 37, 2453–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, M.Z.; Hasan, M.; Yakopcic, C.; Taha, T.M.; Asari, V.K. (2018). Recurrent Residual Convolutional Neural Network based on U-Net (R2U-Net) for Medical Image Segmentation. https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.06955. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dou, Q.; Yu, L.; Qin, J.; Heng, P.-A. VoxResNet: Deep voxelwise residual networks for brain segmentation from 3D MR images. NeuroImage 2018, 170, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, R.; Qin, C.; Oktay, O.; Bowles, C.; Chen, L.; Joules, R.; Wolz, R.; Valdés-Hernández, M.C.; Dickie, D.A.; Wardlaw, J.; Rueckert, D. White matter hyperintensity and stroke lesion segmentation and differentiation using convolutional neural networks. NeuroImage: Clinical 2018, 17, 918–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdzal, M.; Chartrand, G.; Vorontsov, E.; Shakeri, M.; di Jorio, L.; Tang, A.; Romero, A.; Bengio, Y.; Pal, C.; Kadoury, S. Learning normalized inputs for iterative estimation in medical image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2018, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Meng, Z.; Sun, C.; Cui, H.; Su, R. RA-UNet: A Hybrid Deep Attention-Aware Network to Extract Liver and Tumor in CT Scans. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheibi, Y.; Shirini, K.; Razavi, S.N.; Farhoudi, M.; Samad-Soltani, T. CNN-Res: deep learning framework for segmentation of acute ischemic stroke lesions on multimodal MRI images. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2023, 23, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenyk, Z. (2021, February 3). Microsoft Vision Model ResNet-50 combines web-scale data and multi-task learning to achieve state of the art. https://www.Microsoft.Com/En-Us/Research/Blog/Microsoft-Vision-Model-Resnet-50-Combines-Web-Scale-Data-and-Multi-Task-Learning-to-Achieve-State-of-the-Art/.

- Drozdzal, M.; Vorontsov, E.; Chartrand, G.; Kadoury, S.; Pal, C. (2016). The Importance of Skip Connections in Biomedical Image Segmentation. https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.04117. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Wang, J. Application of Deep Learning Method on Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Science) 2022, 27, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-H.; Phillips, P.; Sui, Y.; Liu, B.; Yang, M.; Cheng, H. Classification of Alzheimer’s Disease Based on Eight-Layer Convolutional Neural Network with Leaky Rectified Linear Unit and Max Pooling. Journal of Medical Systems 2018, 42, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthik, R.; Gupta, U.; Jha, A.; Rajalakshmi, R.; Menaka, R. A deep supervised approach for ischemic lesion segmentation from multimodal MRI using Fully Convolutional Network. Applied Soft Computing 2019, 84, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlemper, J.; Oktay, O.; Schaap, M.; Heinrich, M.; Kainz, B.; Glocker, B.; Rueckert, D. Attention gated networks: Learning to leverage salient regions in medical images. Medical Image Analysis 2019, 53, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthik, R.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Rajalakshmi, R.; Raymann, J. Delineation of ischemic lesion from brain MRI using attention gated fully convolutional network. Biomedical Engineering Letters 2021, 11, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari-Farsani, S.; Yu, Y.; Duarte Armindo, R.; Lansberg, M.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Albers, G.; Christensen, S.; Levin, C.S.; Zaharchuk, G. Predicting final ischemic stroke lesions from initial diffusion-weighted images using a deep neural network. NeuroImage: Clinical 2023, 37, 103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Thamm, T.; Gong, E.; Ouyang, J.; Huang, C.; Christensen, S.; Marks, M.P.; Lansberg, M.G.; Albers, G.W.; Zaharchuk, G. Use of Deep Learning to Predict Final Ischemic Stroke Lesions From Initial Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JAMA Network Open 2020, 3, e200772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shore, J.; Johnson, R. Axiomatic derivation of the principle of maximum entropy and the principle of minimum cross-entropy. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1980, 26, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.; Cummock, J.S.; Li, G.; Ghosh, R.; Xu, P.; Volpi, J.J.; Wong, S.T.C. Automatic Segmentation in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Prognostic Significance of Topological Stroke Volumes on Stroke Outcome. Stroke 2022, 53, 2896–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.-C.; Huang, W.-Y.; Jian, C.-Y.; Hsu, C.-C.H.; Hsu, C.-C.; Lin, C.-P.; Cheng, C.-T.; Chen, Y.-L.; Wei, H.-Y.; Chen, K.-F. Semantic segmentation guided detector for segmentation, classification, and lesion mapping of acute ischemic stroke in MRI images. NeuroImage: Clinical 2022, 35, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.S.; Heffron, L.; Mahzarnia, A.; Obeng-Gyasi, B.; Holbrook, M.; Badea, C.T.; Feng, W.; Badea, A. Automated multimodal segmentation of acute ischemic stroke lesions on clinical MR images. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2022, 92, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brott, T.; Adams, H.P.; Olinger, C.P.; Marler, J.R.; Barsan, W.G.; Biller, J.; Spilker, J.; Holleran, R.; Eberle, R.; Hertzberg, V. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989, 20, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzeck, S., Hakim, A., McKinley, R., Pinto, J. A. A. D. S. R., Alves, V., Silva, C., Pisov, M., Krivov, E., Belyaev, M., Monteiro, M., Oliveira, A., Choi, Y., Paik, M. C., Kwon, Y., Lee, H., Kim, B. J., Won, J.-H., Islam, M., Ren, H., … Reyes, M. (2018). ISLES 2016 and 2017-Benchmarking Ischemic Stroke Lesion Outcome Prediction Based on Multispectral MRI. Frontiers in Neurology, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Petzsche, M. R., de la Rosa, E., Hanning, U., Wiest, R., Valenzuela, W., Reyes, M., Meyer, M., Liew, S.-L., Kofler, F., Ezhov, I., Robben, D., Hutton, A., Friedrich, T., Zarth, T., Bürkle, J., Baran, T. A., Menze, B., Broocks, G., Meyer, L., … Kirschke, J. S. (2022). ISLES 2022: A multi-center magnetic resonance imaging stroke lesion segmentation dataset. Scientific Data, 9(1), 762. [CrossRef]

- Lansberg, M.G.; Straka, M.; Kemp, S.; Mlynash, M.; Wechsler, L.R.; Jovin, T.G.; Wilder, M.J.; Lutsep, H.L.; Czartoski, T.J.; Bernstein, R.A.; Chang, C.W.; Warach, S.; Fazekas, F.; Inoue, M.; Tipirneni, A.; Hamilton, S.A.; Zaharchuk, G.; Marks, M.P.; Bammer, R.; Albers, G.W. MRI profile and response to endovascular reperfusion after stroke (DEFUSE 2): a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Neurology 2012, 11, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.P.; Heit, J.J.; Lansberg, M.G.; Kemp, S.; Christensen, S.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Rasmussen, P.A.; Zaidat, O.O.; Broderick, J.P.; Yeatts, S.D.; Hamilton, S.; Mlynash, M.; Albers, G.W. Endovascular Treatment in the DEFUSE 3 Study. Stroke 2018, 49, 2000–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaharchuk, G. (2020, March 19). Imaging Collaterals in Acute Stroke (iCAS) (iCAS). Https://Clinicaltrials.Gov/Study/NCT02225730.

- Karthik, R.; Menaka, R.; Johnson, A.; Anand, S. Neu2roimaging and deep learning for brain stroke detection - A review of recent advancements and future prospects. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 197, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelio Lea Katrina, S.; del Castillo MA, V.; N Jr. P., C. U-ISLES: Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation Using U-Net. In S. and B. R. Arai Kohei and Kapoor (Ed.), Intelligent Systems and Applications. Pp. 326–336. Springer International Publishing.

- Aboudi, F., Drissi, C., & Kraiem, T. (2022). Efficient U-Net CNN with Data Augmentation for MRI Ischemic Stroke Brain Segmentation. 2022 8th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), 1, 724–728. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kurgan, L.; Wu, F.; Wang, J. Attention convolutional neural network for accurate segmentation and quantification of lesions in ischemic stroke disease. Medical Image Analysis 2020, 65, 101791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostmeier, S.; Axelrod, B.; Isensee, F.; Bertels, J.; Mlynash, M.; Christensen, S.; Lansberg, M.G.; Albers, G.W.; Sheth, R.; Verhaaren, B.F.J.; Mahammedi, A.; Li, L.-J.; Zaharchuk, G.; Heit, J.J. USE-Evaluator: Performance metrics for medical image segmentation models supervised by uncertain, small or empty reference annotations in neuroimaging. Medical Image Analysis 2023, 90, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.L.; Factor, R.E. Understanding sources of bias in diagnostic accuracy studies. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 2013, 137, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-C.; Lee, J.-E.; Yu, I.; Song, H.-N.; Baek, I.-Y.; Seong, J.-K.; Jeong, H.-G.; Kim, B.J.; Nam, H.S.; Chung, J.-W.; Bang, O.Y.; Kim, G.-M.; Seo, W.-K. Evaluation of Diffusion Lesion Volume Measurements in Acute Ischemic Stroke Using Encoder-Decoder Convolutional Network. Stroke 2019, 50, 1444–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdmouleh, N., Echtioui, A., Kallel, F., & Hamida, A. ben. (2022). Modified U-Net Architecture based Ischemic Stroke Lesions Segmentation. 2022 IEEE 21st International Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (STA), 361–365. [CrossRef]

- Pavlakis, S.G.; Hirtz, D.G.; deVeber, G. Pediatric Stroke: Opportunities and Challenges in Planning Clinical Trials. Pediatric Neurology 2006, 34, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospel, J.; Singh, N.; Ganesh, A.; Goyal, M. Sex and Gender Differences in Stroke and Their Practical Implications in Acute Care. Journal of Stroke 2023, 25, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Cao, C.; Ding, S.; Liu, Z.; Han, T.; Liu, S. Towards Clinical Diagnosis: Automated Stroke Lesion Segmentation on Multi-Spectral MR Image Using Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 57006–57016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulms, N.; Redmann, L.; Herpertz, C.; Bonberg, N.; Berger, K.; Sundermann, B.; Minnerup, H. The Effect of Training Sample Size on the Prediction of White Matter Hyperintensity Volume in a Healthy Population Using BIANCA. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clèrigues, A.; Valverde, S.; Bernal, J.; Freixenet, J.; Oliver, A.; Lladó, X. Acute and sub-acute stroke lesion segmentation from multimodal MRI. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 194, 105521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, A.; Moal, O.; Moal, B.; Munsch, F.; Okubo, G.; Sibon, I.; Dousset, V.; Tourdias, T. Active learning strategy and hybrid training for infarct segmentation on diffusion MRI with a U-shaped network. Journal of Medical Imaging 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Cao, C.; Jin, S.; Wu, H.; Ding, S. Deep Learning-Based Acute Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation Method on Multimodal MR Images Using a Few Fully Labeled Subjects. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine 2021, 2021, 3628179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Ji, P. TernausNet-based segmentation of cerebral infarction in magnetic resonance images. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2023, 16, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglovikov, V.; Shvets, A. (2018). TernausNet: U-Net with VGG11 Encoder Pre-Trained on ImageNet for Image Segmentation. https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.05746. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L.-J., Kai Li, & Li Fei-Fei. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2009, 248–255. [CrossRef]

- Schick, F.; Pieper, C.C.; Kupczyk, P.; Almansour, H.; Keller, G.; Springer, F.; Mürtz, P.; Endler, C.; Sprinkart, A.M.; Kaufmann, S.; Herrmann, J.; Attenberger, U.I. 1.5 vs 3 Tesla Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Investigative Radiology 2021, 56, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Fan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, D.; Feng, Y.; Lu, J.; Fan, Y. Deep Learning in Ischemic Stroke Imaging Analysis: A Comprehensive Review. BioMed Research International 2022, 2022, 2456550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Farrall, A.J. Diagnosis of stroke on neuroimaging. BMJ 2004, 328, 655–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, R.; Menaka, R. Computer-aided detection and characterization of stroke lesion – a short review on the current state-of-the art methods. The Imaging Science Journal 2018, 66, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezrpour, S.; Seyedarabi, H.; Razavi, S.N.; Farhoudi, M. Automatic segmentation of the brain stroke lesions from MR flair scans using improved U-net framework. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 78, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, C.Z.; Madsen, M.H.; Schmitz, M.L.; Mikkelsen, I.K.; Fisher, M.; Andersen, G. Sensitivity of Diffusion- and Perfusion-Weighted Imaging for Diagnosing Acute Ischemic Stroke Is 97.5%. Stroke 2015, 46, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Sunwoo, L.; Choi, Y.; Jung, J.H.; Jung, S.C.; Won, J.-H. Impact of Diffusion–Perfusion Mismatch on Predicting Final Infarction Lesion Using Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 97879–97887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitburana, O.; Koroshetz, W.J. Magnetic resonance imaging: Implication in acute ischemic stroke management. Current Atherosclerosis Reports 2005, 7, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuda, W.; Lansberg, M.G.; Thijs, V.N.; Kemp, S.M.; Bammer, R.; Wechsler, L.R.; Moseley, M.E.; Parks, M.P.; Albers, G.W. Optimal Definition for PWI/DWI Mismatch in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2008, 28, 887–891. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, H.; Luo, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y. An automatic machine learning approach for ischemic stroke onset time identification based on DWI and FLAIR imaging. NeuroImage: Clinical 2021, 31, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avesta, A.; Hossain, S.; Lin, M.; Aboian, M.; Krumholz, H.M.; Aneja, S. Comparing 3D, 2.5D, and 2D Approaches to Brain Image Auto-Segmentation. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L., Yang, X., Chen, H., Qin, J., & Heng, P. A. (2017). Volumetric ConvNets with Mixed Residual Connections for Automated Prostate Segmentation from 3D MR Images. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 31(1). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Li, J. W-Net: A boundary-enhanced segmentation network for stroke lesions. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 230, 120637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.R.; Mohseni Salehi, S.S.; Erdogmus, D.; Prabhu, S.P.; Warfield, S.K.; Gholipour, A. Asymmetric Loss Functions and Deep Densely-Connected Networks for Highly-Imbalanced Medical Image Segmentation: Application to Multiple Sclerosis Lesion Detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 1721–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Wang, J. Rethinking the Dice Loss for Deep Learning Lesion Segmentation in Medical Images. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Science) 2021, 26, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Luo, W.; Hu, J.; Guo, S.; Huang, W.; Scott, M.R.; Wiest, R.; Dahlweid, M.; Reyes, M. Brain SegNet: 3D local refinement network for brain lesion segmentation. BMC Medical Imaging 2020, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachmadi, M. F., Poon, C., & Skibbe, H. (2023). Improving Segmentation of Objects with Varying Sizes in Biomedical Images using Instance-wise and Center-of-Instance Segmentation Loss Function. https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.06229. [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, M.A.; Raghavendra, U.; Gudigar, A.; Chakole, Y.; Hegde, A.; Menon, G.R.; Barua, P.; Palmer, E.E.; Cheong, K.H.; Chan, W.Y.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Acharya, U.R. A Review on Computer Aided Diagnosis of Acute Brain Stroke. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ying, L.; Xiao, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, H.; Liang, D. Learning Joint-Sparse Codes for Calibration-Free Parallel MR Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2018, 37, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.S.; Vijayalakshmi, V. A review on acute/sub-acute ischemic stroke lesion segmentation and registration challenges. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2019, 78, 2481–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wu, F.-X.; Wang, J. Efficient multi-kernel DCNN with pixel dropout for stroke MRI segmentation. Neurocomputing 2019, 350, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y., Kwon, Y., Lee, H., Kim, B. J., Paik, M. C., & Won, J.-H. (2016). Ensemble of Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Prognosis of Ischemic Stroke. In A. Crimi, B. Menze, O. Maier, M. Reyes, S. Winzeck, & H. Handels (Eds.), Brainlesion: Glioma, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injuries. Pp. 231–243). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Pinto A., Pereira, S., M. R., A. V., W. R., S. C. A., R. M. (2018). Enhancing Clinical MRI Perfusion Maps with Data-Driven Maps of Complementary Nature for Lesion Outcome Prediction. In J. A. and D. C. and A.-L. C. and F. G. Frangi Alejandro F. and Schnabel (Ed.), Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018. Pp. 107–115. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Duan W., Zhang, L. and C. J. and G. G. and Y. X. (2021). Multi-modal Brain Segmentation Using Hyper-Fused Convolutional Neural Network. In S. M. and H. M. and K. V. and R. J. M. and T. C. and W. T. Abdulkadir Ahmed and Kia (Ed.), Machine Learning in Clinical Neuroimaging. Pp. 82–91. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Song, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, L. Ischemic Stroke Lesion Segmentation Using Multi-Plane Information Fusion. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 45715–45725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, C., Kemmling, A., Mamlouk, A. M., & Heinrich, M. P. (2018). Multi-scale neural network for automatic segmentation of ischemic strokes on acute perfusion images. 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), 1118–1121. [CrossRef]

- Karthik, R.; Menaka, R.; Hariharan, M.; Won, D. Ischemic Lesion Segmentation using Ensemble of Multi-Scale Region Aligned CNN. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2021, 200, 105831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vupputuri, A.; Gupta, A. MCA-DN: Multi-path convolution leveraged attention deep network for salvageable tissue detection in ischemic stroke from multi-parametric MRI. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2021, 136, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y., Yuan, Y., Huang, X., Wong, K., Volpi, J., Wang, J. Z., & Wong, S. T. C. (2021). LambdaUNet: 2.5D Stroke Lesion Segmentation of Diffusion-Weighted MR Images. Pp. 731–741. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhang, S.; Xu, L.; Zhu, B.; Cui, H.; Geng, N.; Han, H.; Greenwald, S.E. Detection and Localization of Myocardial Infarction Based on Multi-Scale ResNet and Attention Mechanism. Frontiers in Physiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Yin, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ersoy, O.K. Multi-scale ResNet and BiGRU automatic sleep staging based on attention mechanism. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0269500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, L.; Quint, F.; Babyn, P.; Alirezaie, J. Dilated Convolution ResNet with Boosting Attention Modules and Combined Loss Functions for LDCT Image Denoising. 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 2022, 1548–1551. [CrossRef]

- Kendall, A., & Gal, Y. (2017). What Uncertainties Do We Need in Bayesian Deep Learning for Computer Vision? https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.04977. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Garner, P.; Donegan, S. Interpretation of subgroup analyses in systematic reviews: A tutorial. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 2019, 7, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L. (1985). Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Elsevier.

- Kumar, A.; Upadhyay, N.; Ghosal, P.; Chowdhury, T.; Das, D.; Mukherjee, A.; Nandi, D. CSNet: A new DeepNet framework for ischemic stroke lesion segmentation. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 193, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpathy, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Deep Visual-Semantic Alignments for Generating Image Descriptions. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, E.; Ballerini, L.; Hernandez M del, C.V.; Chappell, F.M.; González-Castro, V.; Anblagan, D.; Danso, S.; Muñoz-Maniega, S.; Job, D.; Pernet, C.; Mair, G.; MacGillivray, T.J.; Trucco, E.; Wardlaw, J.M. Machine learning of neuroimaging for assisted diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring 2018, 10, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springenberg, J. T., Dosovitskiy, A., Brox, T., & Riedmiller, M. (2014). Striving for Simplicity: The All Convolutional Net. https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6806. [CrossRef]

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and Understanding Convolutional Networks. 2014, Pp. 818–833. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, S.; Cheng, S.; Li, Z. NG-NAS: Node growth neural architecture search for 3D medical image segmentation. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2023, 108, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, J.; Vangone, A.; Meyder, A.; Adaszewski, S.; Strahm, M.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Zhang, S. The Prospects of Monte Carlo Antibody Loop Modelling on a Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computer. Frontiers in Drug Discovery 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Included | Excluded | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke types | Ischaemic | Haemorrhagic | Differences in clinical presentations, lesion appearances, & aetiologies. |

| Stroke stages |

|

|

Prioritize stages where MRI plays a more prominent role in diagnosis and treatment planning. |

| Imaging |

|

|

MRI allows in-vivo assessment offering better soft tissue contrast & resolution than CT and PET. |

| Algorithms |

|

|

DL is the current state-of-the-art computational approach, much better than others at learning complex hierarchical features. |

| Population |

|

|

Human-based studies are more clinically relevant. Synthetic data may not fully capture variations and complexities of real clinical stroke lesions. |

| Publishing |

|

|

To only retain the most reliable sources of information while also aiming for a wide readership. |

| Completeness | Studies with sufficient information to be reproduced. | Studies not reporting segmentation performance scores. | Reproducibility is key in scientific research. |

| First author | Sample size | Number of medical centers | Stroke stage | Age range | Gender | Mean NIHSS | Mean Stroke-to-MRI time | Mean lesion volume | Lesion volume ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SC: Single-center; MC: Multi-center |

Acute; Subacute |

M: Male F: Female |

(in ml) | (in ml) | |||||

| Karthik, R. [42] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Gómez, S. [23] | 75 | MC: 2 | Acute | [18+] | - | - | - | 37.83 | [1.6, 160.4] |

| Olivier, A. [70] | 929 | MC: 6 | Acute Subacute |

[16–94] | M: 63.7% F: 36.3% |

7.6 | 68.8h | 21.84 | - |

| Clèrigues, A. [69] | 114 | MC: 4 | Acute Subacute |

[18+] | - | - | - | SISS: 17.59 SPES: 133.21 |

SISS: [1.0, 346.1] SPES: [45.6, 252.2] |

| Liu, L. [60] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Moon, H. [50] | 79 | - | Acute | - | M: 44.3% F: 55.7% |

9.3 | 83.8h | - | [0.0, 250] |

| Zhang, R. [19] | 242 | SC: 1 | Acute | [35–90] | M: 60.3% F: 39.7% |

- | - | - | - |

| Wong, K. [48] | 875 | SC: 1 | Acute | - | M: 48.9% F: 51.1% |

6 | - | - | - |

| Khezrpour, S. [79] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Hu, X. [90] | 75 | MC: 2 | Acute | [18+] | - | - | - | 37.83 | [1.6, 160.4] |

| Gheibi, Y. [37] | 44 | MC: 2 | Acute | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Kumar, A. [110] | 189 | MC: 6 | Acute Subacute |

[18+] | - | - | - | SISS: 17.59 SPES: 133.21 IS17: 37.83 |

SISS: [1.0, 346.1] SPES: [45.6, 252.2] IS17: [1.6, 160.4] |

| Liu, L. [16] | 79 | MC: 2 | Acute | [18+] | - | - | - | SPES: 133.21 LHC: - |

SPES: [45.6, 252.2] LHC: - |

| Zhao, B. [71] | 582 | SC: 1 | Acute | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Liu, C. [27] | 1849 | SC: 1 | Acute Subacute | [52–73] | M: 52.9% F: 47.1% |

3.4 | 17.7h | 3.12 | [1.55, 5.33] |

| Karthik, R. [44] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Liu, L. [95] | 114 | MC: 4 | Acute Subacute |

[18+] | - | - | - | SISS: 17.59 SPES: 133.21 |

SISS: [1.0, 346.1] SPES: [45.6, 252.2] |

| Aboudi, F. [59] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Pinto, A. [97] | 75 | MC: 2 | Acute | [18+] | - | - | - | 37.83 | [1.6, 160.4] |

| Choi, Y. [96] | 54 | MC: 2 | Acute | [18+] | - | - | - | 37.83 | [1.6, 160.4] |

| Kim, Y. [63] | 296 | SC: 1 | Acute | [58–79] | M: 61.3% F: 38.7% |

2.3 | 12.7h | 12.19 | [0.0, 279.4] |

| Woo, I. [25] | 429 | SC: 1 | Acute | [24–98] | M: 62.3% F: 37.7% |

- | 21.4h | - | - |

| Lee, A. [26] | 429 | SC: 1 | Acute[24–98 | [24–98] | M: 62.3% F: 37.7% |

- | 21.4h | 27.44 | [0.3, 227.6] |

| Lee, S. [81] | 472 | SC: 1 | Acute | [19+] | M: 63.3% F: 36.7% |

3 | 4.9h | 3.62 | [0.52, 71.8] |

| Karthik, R. [101] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Zhang, L. [99] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Ou, Y. [103] | 99 | SC: 1 | Acute | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vupputuri, A. [102] | 189 | MC: 6 | Acute Subacute |

[18+] | - | - | - | SISS: 17.59 SPES: 133.21 IS17: 37.83 |

SISS: [1.0, 346.1] SPES: [45.6, 252.2] IS17: [1.6, 160.4] |

| Abdmouleh, N. [64] | 64 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 17.59 | [1.0, 346.1] |

| Duan, W. [98] | 120 | SC: 1 | Acute | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lucas, C. [100] | 75 | MC: 2 | Acute | [18+] | - | - | - | 37.83 | [1.6, 160.4] |

| Nazari-Farsani, S. [45] | 445 | MC: 6+ | Acute | - | M: 50% F: 50% |

13 | 6.2h | 50 | [15, 123] |

| Wei, Y. [49] | 216 | SC: 1 | Acute | - | M: 69.7% F: 30.3% |

- | - | - | - |

| Li, C. [72] | 60 | SC: 1 | Acute | [49–88] | - | - | - | - | - |

| Liu, Z. [67] | 212 | SC: 1 | Acute Subacute |

- | M: 62% F: 38% |

- | - | - | - |

| Cornelio, L. [58] | 75 | MC: 2 | Acute | [18+] | - | - | - | 37.83 | [1.6, 160.4] |

| Yu, Y. [46] | 182 | MC: 6+ | Acute | - | M: 46.7% F: 53.3% |

15 | - | 54 | [16, 117] |

| Wu, Z. [87] | 400 | MC: 3 | Subacute | [18+] | - | - | - | 27.94 | [0.0575, 340.28] |

| Guerrero, R. [34] | 250 | SC: 1 | Acute | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| First author | Spatial resolution | Image modalities | Input dimension | Modality mismatch | Magnetic field |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Very High (VH); 2-High (H); 3-Moderate (M); 4-Low (L) |

SM: Single-modality; MM: Multi-modality Format: Modality-{Parameter} |

2D; 2.5D; 3D |

T1-T2; DWI-PWI; DWI-FLAIR; T2-FLAIR; T1-FLAIR |

1.5T; 3T |

|

| Karthik, R. [42] | 2-H | MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Gómez, S. [23] | 2-H | MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} | 2D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Olivier, A. [70] | Not reported | SM: {DWI-b0, DWI-b1000, DWI-ADC} | 3D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Clèrigues, A. [69] | 4-L |

MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} MM: {T1WI, T2WI, DWI-b1000, PWI-CBF, PWI-CBV, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax} |

3D | DWI-PWI; DWI-FLAIR |

1.5T 3T |

| Liu, L. [60] | 2-H | MM: {FLAIR, DWI-b1000} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Moon, H. [50] | 1-VH | MM: {FLAIR, DWI-b1000} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T |

| Zhang, R. [19] | 3-M | SM: {DWI-b0, DWI-b1000, DWI-ADC} | 3D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Wong, K. [48] | Not reported | SM: {DWI-b0, DWI-b1000, DWI-eADC} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Khezrpour, S. [79] | 2-H | SM: {FLAIR} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Hu, X. [90] | 4-L | MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} | 3D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Gheibi, Y. [37] | Not reported | MM: {FLAIR, DWI} | 2D | None reported | - |

| Kumar, A. [110] | 4-L |

MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} MM: {T1WI, T2WI, DWI-b1000, PWI-CBF, PWI-CBV, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax} MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} |

3D | DWI-PWI; DWI-FLAIR |

1.5T 3T |

| Liu, L. [16] | 2-H |

MM: {T1WI, T2WI, DWI-b1000, PWI-CBF, PWI-CBV, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax} MM: {DWI, T2WI} |

2D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Zhao, B. [71] | 2-H | SM: {DWI-ADC, DWI-b0, DWI-b1000} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Liu, C. [27] | 3-M | SM: {DWI-b0, DWI-ADC, DWI-IS} | 3D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Karthik, R. [44] | 2-H | MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Liu, L. [95] | 2-H |

MM: {FLAIR, DWI-b1000} MM: {T2WI, DWI-b1000, PWI-CBF, PWI-CBV, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax} |

2D | DWI-PWI; DWI-FLAIR |

1.5T 3T |

| Aboudi, F. [59] | 2-H | MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Pinto, A. [97] | 2-H | MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} | 2D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Choi, Y. [96] | 4-L | MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} | 3D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Kim, Y. [63] | 1-VH | SM: {DWI-b0, DWI-b1000, DWI-ADC} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Woo, I. [25] | 1-VH | SM: {DWI-b1000, DWI-b0, DWI-ADC} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Lee, A. [26] | 1-VH | SM: {DWI-b1000, DWI-b0, DWI-ADC} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Lee, S. [81] | 3-M | MM: {DWI, DWI-ADC, FLAIR, PWI-Tmax, PWI-TTP, Pred(init)} | 3D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Karthik, R. [101] | 2-H | MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Zhang, L. [99] | 2-H | SM: {DWI-b1000} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Ou, Y. [103] | 1-VH | SM: {DWI-b1000, DWI-eADC} | 2.5D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Vupputuri, A. [102] | 2-H |

MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} MM: {T1WI, T2WI, DWI-b1000, PWI-CBF, PWI-CBV, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax} MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} |

2D | DWI-PWI; DWI-FLAIR |

1.5T 3T |

| Abdmouleh, N. [64] | 2-H | MM: {FLAIR, T2WI, T1WI, DWI-b1000} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 3T |

| Duan, W. [98] | Not reported | MM: {T2WI, DWI-b1000, DWI-b0} | 3D | None reported | - |

| Lucas, C. [100] | 2-H | MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} | 2D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Nazari-Farsani, S. [45] | Not reported | SM: {DWI-b1000, DWI-ADC} | 3D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Wei, Y. [49] | 1-VH | SM: {DWI-b1000} | 2D | T1-T2; T2-FLAIR; T1-FLAIR |

3T |

| Li, C. [72] | 1-VH | MM: {T1WI, T2WI, T2WI-FLAIR, DWI, DWI-ADC} | 2D | T2-FLAIR; T1-FLAIR |

1.5T |

| Liu, Z. [67] | Not reported | MM: {T2WI, DWI, DWI-ADC} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Cornelio, L. [58] | 2-H | MM: {DWI-ADC, PWI-rCBF, PWI-rCBV, PWI-MTT, PWI-TTP, PWI-Tmax, Raw 4D PWI} | 2D | DWI-PWI | 1.5T 3T |

| Yu, Y. [46] | Not reported | MM: {DWI-b1000, DWI-ADC, PWI-Tmax, PWI-MTT, PWI-CBF, PWI-CBV} | 2.5D | None reported | 1.5T 3T |

| Wu, Z. [87] | 1-VH | MM: {DWI-b1000, DWI-ADC, FLAIR} | 2D | DWI-FLAIR | 1.5T 3T |

| Guerrero, R. [34] | 1-VH | MM: {FLAIR, T1WI} | 2D | None reported | 1.5T |

| Data pre-processing methods | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Dataset | Intensity-based | Atlas-based | Morphology-based | Deformable surface-based | Machine learning-based |

| Dataset used for model training | Data pre-processing techniques used prior to model training | |||||

| Karthik, R. [42] | ISLES2015 SISS | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing | - Registration | - |

| Gómez, S. [23] | ISLES2017 | - Normalization - Contrast adjustment - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing - Rescaling |

- Registration | - |

| Olivier, A. [70] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - Rescaling - Zero-padding - Cropping |

- | - |

| Clèrigues, A. [69] | ISLES2015 SISS ISLES2015 SPES | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - | - Registration | - |

| Liu, L. [60] | ISLES2015 SISS | - Skull-stripping | - | - | - Registration | - |

| Moon, H. [50] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - Skull-stripping | - Zero-padding - Resizing |

- Registration | - |

| Zhang, R. [19] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - Zero-padding - Cropping - Resizing |

- | - |

| Wong, K. [48] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - | - | - |

| Khezrpour, S. [79] | ISLES2015 SISS | - Contrast adjustment - RGB to greyscale - Skull-stripping |

- | - Cropping - Resizing |

- Registration | - |

| Hu, X. [90] | ISLES2017 | - Skull-stripping | - | - Resizing - Cropping |

- Registration | - |

| Gheibi, Y. [37] | Proprietary | - | - | - Zero-padding | - Splitting into 2D | - |

| Kumar, A. [110] | ISLES2015 SPES ISLES2015 SSIS ISLES2017 |

- Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- Resizing | - Converting to 3D - Registration |

- Slice classification | |

| Liu, L. [16] | ISLES2015 SPES Proprietary |

- Normalization - Smoothing - Skull-stripping |

- | - | - Registration | - |

| Zhao, B. [71] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - | - | - |

| Liu, C. [27] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - Resizing - Rescaling |

- | - Slice classification - Skull-stripping |

| Karthik, R. [44] | ISLES2015 SISS | - Skull-stripping | - | - | - Registration | - |

| Liu, L. [95] | ISLES2015 SPES ISLES2015 SISS | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Zero-padding - Cropping - Resizing |

- Registration - Splitting into 2D |

- |

| Aboudi, F. [59] | ISLES2015 SISS | - RGB to greyscale - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing - Rescaling |

- Registration | - |

| Pinto, A. [97] | ISLES2017 | - Normalization - Bias field correction - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing | - Registration | - |

| Choi, Y. [96] | ISLES2016 | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing - Rescaling |

- Registration | - |

| Kim, Y. [63] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - Resizing | - | - |

| Woo, I. [25] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - | - Registration | - |

| Lee, A. [26] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - Resizing | - Registration | - |

| Lee, S. [81] | Proprietary | - | - | - Resizing - Rescaling |

- Registration | - |

| Karthik, R. [101] | ISLES2015 SISS | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Cropping - Rescaling |

- Registration | - Slice classification |

| Zhang, L. [99] | ISLES2015 SISS | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Cropping - Rescaling |

- Registration | - Slice classification |

| Ou, Y. [103] | Proprietary | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing | - | - |

| Vupputuri, A. [102] | ISLES2015 SPES ISLES2015 SISS ISLES2017 (IS17) |

- RGB to greyscale - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - | - Registration | - |

| Abdmouleh, N. [64] | ISLES2015 SISS | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - | - Registration | - |

| Duan, W. [98] | Proprietary | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing | - | - |

| Lucas, C. [100] | ISLES2017 | - Skull-stripping | - | - Rescaling | - Registration | - |

| Nazari-Farsani, S. [45] | UCLA iCAS DEFUSE DEFUSE-2 |

- Normalization | - | - | - Registration | - |

| Wei, Y. [49] | Proprietary | - Skull-stripping | - | - Rescaling | - Registration | - |

| Li, C. [72] | Proprietary | - | - | - Resizing | - | - |

| Liu, Z. [67] | Proprietary | - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Cropping - Resizing |

- Registration | - |

| Cornelio, L. [58] | ISLES2017 | - RGB to greyscale - Contrast adjustment - Normalization - Skull-stripping |

- | - Resizing | - Registration | - |

| Yu, Y. [46] | iCAS DEFUSE-2 |

- Normalization | - | - | - Registration | - |

| Wu, Z. [87] | ISLES2022 | - Skull-stripping | - | - Resizing - Rescaling |

- Registration | - |

| Guerrero, R. [34] | Proprietary | - Normalization | - | - Resizing | - Registration | - |

| First author | Architecture (Segmentation type) |

Loss function | Attention mechanism / type | Activation functions | Regularization method | Optimization method | Epochs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karthik, R. [42] | U-Net (Semantic) |

Dice | None | Leaky ReLU, ReLU, Softmax | Data augmentation | Adam | 120 |

| Gómez, S. [23] | U-Net (Semantic) |

Focal | Additive cross-attention / spatial | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Weight decay - Class weighting |

AdamW | 600 |

| Olivier, A. [70] | U-Net (Semantic) |

Dice | None | Leaky ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - ES on validation loss |

Adam | - |

| Clèrigues, A. [69] | U-Net (Semantic) |

Focal | None | PReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - ES on MAE/L1 loss - Dropout - Class weighting |

AdaDelta | - |

| Liu, L. [60] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | Self-gated soft attention / hybrid | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Dropout |

Adam | 150 |

| Moon, H. [50] | U-Net (Semantic) | BCE | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - | Adam | 200 |

| Zhang, R. [19] | DenseNet (Semantic) | Dice | None | ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - Weight decay - Learning rate adjust. |

SGD | 2000 |

| Wong, K. [48] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | None | ReLU, ? | Data augmentation | - | - |

| Khezrpour, S. [79] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - ES on validation loss |

Adam | - |

| Hu, X. [90] | U-Net + ResNet (Semantic) | Focal | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Class weighting |

Adam | 1500 |

| Gheibi, Y. [37] | U-Net + ResNet (Semantic) | Custom | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Weight decay - Dilution |

Adam | - |

| Kumar, A. [110] | U-Net (Semantic) | BCE-Dice | None | ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - Dropout - ES on validation set - Learning rate adjust. |

Adam | 200 |

| Liu, L. [16] | U-Net + ResNet (Semantic) | Custom | None | Leaky ReLU, Sigmoid | Data augmentation | - | 70 |

| Zhao, B. [71] | CNN (Semantic) | BCE | Squeeze-excitation / channel | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - ES on validation loss |

RAdam | - |

| Liu, C. [27] | U-Net (Semantic) | BCE-Dice | Dual attention gates / hybrid | SeLU (Self-normalized), Sigmoid | - Weight decay - ES on training & val. - Learning rate adjust. - Class weighting |

Adam | 200 |

| Karthik, R. [44] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | Attention gates / spatial | ReLU, Sigmoid | Data augmentation | - | 150 |

| Liu, L. [95] | U-Net + DenseNet (Semantic) | CE-Dice | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Dropout |

Adam | 8 |

| Aboudi, F. [59] | U-Net (Semantic) | CE | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | Data augmentation | Adam | 100 |

| Pinto, A. [97] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | None | - | - | Adam | - |

| Choi, Y. [96] | U-Net + CNN + ResNet (Semantic) | CE-Dice | None | ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - Weight decay - Dropout - ES on ? |

Adam | - |

| Kim, Y. [63] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - | Adam | 1000 |

| Woo, I. [25] | U-Net + DenseNet (Semantic) | - | Squeeze-excitation / channel | ReLU, Sigmoid | - | - | - |

| Lee, A. [26] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | Squeeze-excitation / channel | ReLU, Sigmoid | - | - | - |

| Lee, S. [81] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | ES on validation loss | Adam | - |

| Karthik, R. [101] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice-CE + Softmax-CE | Multi-residual attention / hybrid | ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - Masked dropout - Dropout - Learning rate adjust. |

Adam | 150 |

| Zhang, L. [99] | U-Net (Semantic + Instance) | CE | None | ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - Momentum - Weight decay |

SGD | - |

| Ou, Y. [103] | U-Net (Semantic) | BCE | None | ReLU, Softmax | - | RMSprop | 100 |

| Vupputuri, A. [102] | U-Net (Semantic) | BCE | Multi-path attention / hybrid (includes self-attention) | Leaky ReLU, Softmax | - ES on validation set - Dropout |

Adam | 30 |

| Abdmouleh, N. [64] | U-Net (Semantic) | CE | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | Data augmentation | Adam | 20 |

| Duan, W. [98] | CNN + ResNet (Semantic) | Dice-CE | None | PReLU, Softmax | Data augmentation | Adam | 600 |

| Lucas, C. [100] | U-Net (Semantic) | Soft QDice | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | Data augmentation | Adam | 100 |

| Nazari-Farsani, S. [45] | U-Net (Semantic) | BCE-Volume-MAE-Dice | Attention gates / spatial | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Class weighting - Dropout |

Adam | 80 |

| Wei, Y. [49] | U-Net + ResNet (Semantic) | Focal Tversky | None | ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - Class weighting - Learning rate adjust. |

Adam | 150 |

| Li, C. [72] | U-Net (Instance) | CE | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Class weighting |

SGD | 200 |

| Liu, Z. [67] | CNN + ResNet (Semantic) | Dice | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Weight decay - Learning rate adjust. |

Adam | 500 |

| Cornelio, L. [58] | U-Net (Semantic) | Dice | None | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Dropout - Weight decay |

Adam | 50 |

| Yu, Y. [46] | U-Net (Semantic) | BCE-Volume-MAE-Dice | Attention gates / spatial | ReLU, Sigmoid | - Data augmentation - Class weighting - Dropout |

Adam | 120 |

| Wu, Z. [87] | U-Net + MLP (Semantic) | Dice + Boundary | Multi-head self-attention / hybrid (includes self-attention) | ReLU, Softmax | - Weight decay - Learning rate adjust. |

AdamW | 35 |

| Guerrero, R. [34] | U-Net + ResNet (Semantic) | CCE | None | ReLU, Softmax | - Data augmentation - Class weighting - Learning rate adjust. |

Adam | - |

| First author | Dice | Precision | Recall | Hausdorff distance | Lesion size-based results | General- izability |

Train time | Training library and infrastructure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

* Only scores reported on test sets are extracted * When scores are reported per input dataset, the average score is provided * Format: mean score ± standard deviation |

Results as reported based on lesion size | |||||||

| Karthik, R. [42] | 0.701 | - | - | - | N | L | 7h30 |

CPU: 3.6GHz QuadCore Intel Gen7 RAM: 32GB GPU: Nvidia Quadro P4000 Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Gómez, S. [23] | 0.36 ± 0.21 | 0.42 ± 0.25 | 0.48 ± 0.29 | - | N | L | - | - |

| Olivier, A. [70] | 0.703 ± 0.2 | - | - | - |

Sensitivity: S (<20mL): 0.987 L (>=20mL): 0.923 Specificity: S (<20mL): 0.923 L (>=20mL): 0.987 |

M | - |

GPU: Nvidia Tesla K80 Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Clèrigues, A. [69] | 0.715 ± 0.205 | 0.735 ± 0.25 | 0.745 ± 0.18 | 27.7 ± 21.45 | N | M | - |

CPU: Intel CoreTM i7-7800X OS: Ubuntu 18.04 RAM: 64GB GPU: Nvidia Titan X (12GB) Library: Torch |

| Liu, L. [60] | 0.764 | - | 0.944 | 3.19 | N | M | - | - |

| Moon, H. [50] | 0.737 ± 0.32 | 0.758 | 0.755 | 22.047 | Relation Dice-lesion size: Observed R2=0.195 | L | 24h |

OS: Centos7 GPU: 4 x Nvidia Quadro RTX 8000 Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Zhang, R. [19] | 0.791 | 0.927 | 0.782 | - | N | M | 6h23 |

CPU: Intel Core i7-4790 3.60GHz RAM: 16GB GPU: Nvidia Titan X Library: PyTorch |

| Wong, K. [48] | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.03 | - | N | M | - | - |

| Khezrpour, S. [79] | 0.852 | 0.998 | 0.856 | - | N | L | - |

GPU: Google Cloud Compute (K80) Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Hu, X. [90] | 0.30 ± 0.22 | 0.35 ± 0.27 | 0.43 ± 0.27 | - | N | L | - | GPU: 4 x Nvidia Titan Xp |

| Gheibi, Y. [37] | 0.792 | - | - | - | N | M | 1h27 |

GPU: Nvidia Tesla P100 Library: Keras |

| Kumar, A. [110] | - | 0.633 ± 0.213 | 0.653 ± 0.223 | - | N | M | 11h45 |

CPU: 2x Intel Xeon Silver 4114 (2.2GHz, 10C/20T) RAM: 192GB GPU: Nvidia Tesla V100 PCIe Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Liu, L. [16] | 0.817 | - | - | 1.92 | N | M | 0h36 | Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Zhao, B. [71] | 0.699 ± 0.128 | 0.852 | 0.923 | - | Dice: S: 0.718 (0.12) L: 0.689 (0.222) |

M | - |

CPU: Intel Core i7-6800K RAM: 64GB GPU: Nvidia GeForce 1080Ti Library: PyTorch |

| Liu, C. [27] | 0.76 ± 0.16 | 0.83 ± 0.17 | 0.73 ± 0.19 | - | Dice: S (<1.7ml): 0.68 (0.19) M (≥1.7&<14ml): 0.75 (0.14) L (≥14ml): 0.83 (0.10) |

H | - |

CPU: Intel Core E5-2620v4 (2.1GHz) GPU: 2 x Nvidia Titan XP Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Karthik, R. [44] | 0.7535 | - | - | - | N | L | 34h04 |

CPU: 3.6GHz QuadCore Intel (Gen 7) RAM: 32GB GPU: Nvidia Quadro P4000 Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Liu, L. [95] | 0.68 ± 0.19 | - | - | 39.975 ± 27.95 | N | M | - | - |

| Aboudi, F. [59] | 0.558 | 0.998 | - | - | N | L | - |

CPU: Intel Core i5 8th gen RAM: 8GB GPU: Nvidia GeForce GTX 1050 Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Pinto, A. [97] | 0.29 ± 0.21 | 0.23 ± 0.21 | 0.66 ± 0.29 | 41.58 ± 22.04 | N | L | - |

GPU: Nvidia GeForce GTX-1070 Library: Keras/Theano |

| Choi, Y. [96] | 0.31 | - | - | 37.7 | N | L | 3h |

CPU: 2 x Intel Xeon CPU E5-2630 v3 (2.4GHz) GPU: 4 x Nvidia GeForce GTX TITANX Library: Keras |

| Kim, Y. [63] | 0.6 ± 0.23 | - | - | - | Dice: > 0.75 for lesion volumes > 70mL | L | 20h |

CPU: Intel Xeon Processor E5-2680 (14 CPU, 2.4 GHz) OS: Ubuntu Linux 14.04 SP1 RAM: 64GB GPU: Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 Library: TensorLayer |

| Woo, I. [25] | 0.858 ± 0.0734 | - | - | - | Dice: - S (<10mL): 0.82 - L (>10mL): 0.89 |

L | - | - |

| Lee, A. [26] | 0.854 ± 0.008 | 0.845 | 0.995 | - | N | L | - | - |

| Lee, S. [81] | 0.422 ± 0.277 | 0.48 ± 0.308 | 0.467 ± 0.32 | - | Dice: S (<10mL): 0.377 L (>10mL): 0.607 |

M | 52h30 |

CPU: Xeon Processor E5-2650 v4 (Intel) GPU: Nvidia Titan X Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Karthik, R. [101] | 0.775 | 0.751 | 0.801 | - | N | L | - |

CPU: 4 cores OS: Ubuntu 16.04 RAM: 32GB GPU: 2 x Nvidia Tesla P100 Library: PyTorch |

| Zhang, L. [99] | 0.433 | - | 0.356 | - | N | L | - |

GPU: Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 Ti Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Ou, Y. [103] | 0.865 | 0.894 | 0.818 | - | N | M | 4h |

GPU: 4 x Nvidia Quadro RTX 6000 Library: PyTorch |

| Vupputuri, A. [102] | 0.71 | - | 0.897 | - | N | M | - | GPU: Nvidia Tesla K80 |

| Abdmouleh, N. [64] | 0.71 ± 0.11 | - | - | - | N | L | - | - |

| Duan, W. [98] | 0.677 ± 0.165 | - | - | 85.462 ± 14.496 | N | M | - |

GPU: Nvidia GTX 1080 Ti Library: PyTorch |

| Lucas, C. [100] | 0.35 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 21.48 | N | L | - |

GPU: Nvidia Titan Xp (12GB) Library: PyTorch |

| Nazari-Farsani, S. [45] | 0.5 | - | 0.6 | - | N | M | - | - |

| Wei, Y. [49] | 0.828 | - | - | - | Dice: S (<769 pixels): 0.761 L (>769): 0.83 |

M | - | - |

| Li, C. [72] | - | - | - | 38.27mm | N | L | - | - |

| Liu, Z. [67] | 0.658 | 0.61 | 0.6 | 51.04 | N | M | - |

CPU: Intel Core i7-7700K RAM: 48GB GPU: Nvidia GeForce 1080Ti Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Cornelio, L. [58] | 0.34 | - | - | - | N | L | 5h |

OS: Ubuntu v.16.04.3 GPU: Nvidia GeForce GTX Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Yu, Y. [46] | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.66 | - | N | M | 35h |

GPU: Nvidia Quadro GV100 & Nvidia Tesla V100-PCIE Library: Keras/TensorFlow |

| Wu, Z. [87] | 0.856 | 0.883 | 0.854 | 27.34 | N | M | 0h21 |

GPU: 6 x Nvidia Tesla 4s Library: PyTorch |

| Guerrero, R. [34] | 0.4±0.252 | - | - | - | N | L | - | Library: Lasagne/Theano |

| Mean Dice Score (± STD) | ||||

| DWI | DWI | DWI + FLAIR + T1WI + T2WI | DWI + FLAIR + T1WI + T2WI | |

| UResNet50 | Train | Validation | Train | Validation |

| BCE=0.3 + Dice=0.7 | 0.911 ± 0.11 | 0.692 ± 0.132 | 0.908 ± 0.041 | 0.675 ± 0.128 |

| BCE=0.5 + Dice=0.5 | 0.893 ± 0.102 | 0.610 ± 0.055 | 0.884 ± 0.318 | 0.619 ± 0.301 |

| BCE=0 + Dice=1 | 0.902 ± 0.205 | 0.625 ± 0.306 | 0.886 ± 0.16 | 0.608 ± 0.04 |

| UNet | Train | Validation | Train | Validation |

| BCE=0.3 + Dice=0.7 | 0.843 ± 0.322 | 0.556 ± 0.083 | 0.838 ± 0.072 | 0.570 ± 0.159 |

| BCE=0.5 + Dice=0.5 | 0.829 ± 0.031 | 0.521 ± 0.29 | 0.836 ± 0.2 | 0.547 ± 0.234 |

| BCE=0 + Dice=1 | 0.837 ± 0.202 | 0.560 ± 0.105 | 0.842 ± 0.085 | 0.555 ± 0.18 |

| AG-UResNet50 | Train | Validation | Train | Validation |

| BCE=0.3 + Dice=0.7 | 0.907 ± 0.121 | 0.676 ± 0.222 | 0.909 ± 0.177 | 0.664 ± 0.313 |

| BCE=0.5 + Dice=0.5 | 0.899 ± 0.06 | 0.642 ± 0.176 | 0.873 ± 0.096 | 0.630 ± 0.269 |

| BCE=0 + Dice=1 | 0.893 ± 0.19 | 0.669 ± 0.091 | 0.877 ± 0.231 | 0.631 ± 0.164 |

| AG-UNet | Train | Validation | Train | Validation |

| BCE=0.3 + Dice=0.7 | 0.829 ± 0.258 | 0.522 ± 0.142 | 0.817 ± 0.109 | 0.536 ± 0.22 |

| BCE=0.5 + Dice=0.5 | 0.793 ± 0.2 | 0.518 ± 0.207 | 0.802 ± 0.163 | 0.515 ± 0.082 |

| BCE=0 + Dice=1 | 0.797 ± 0.32 | 0.529 ± 0.099 | 0.784 ± 0.27 | 0.498 ± 0.105 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).