Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

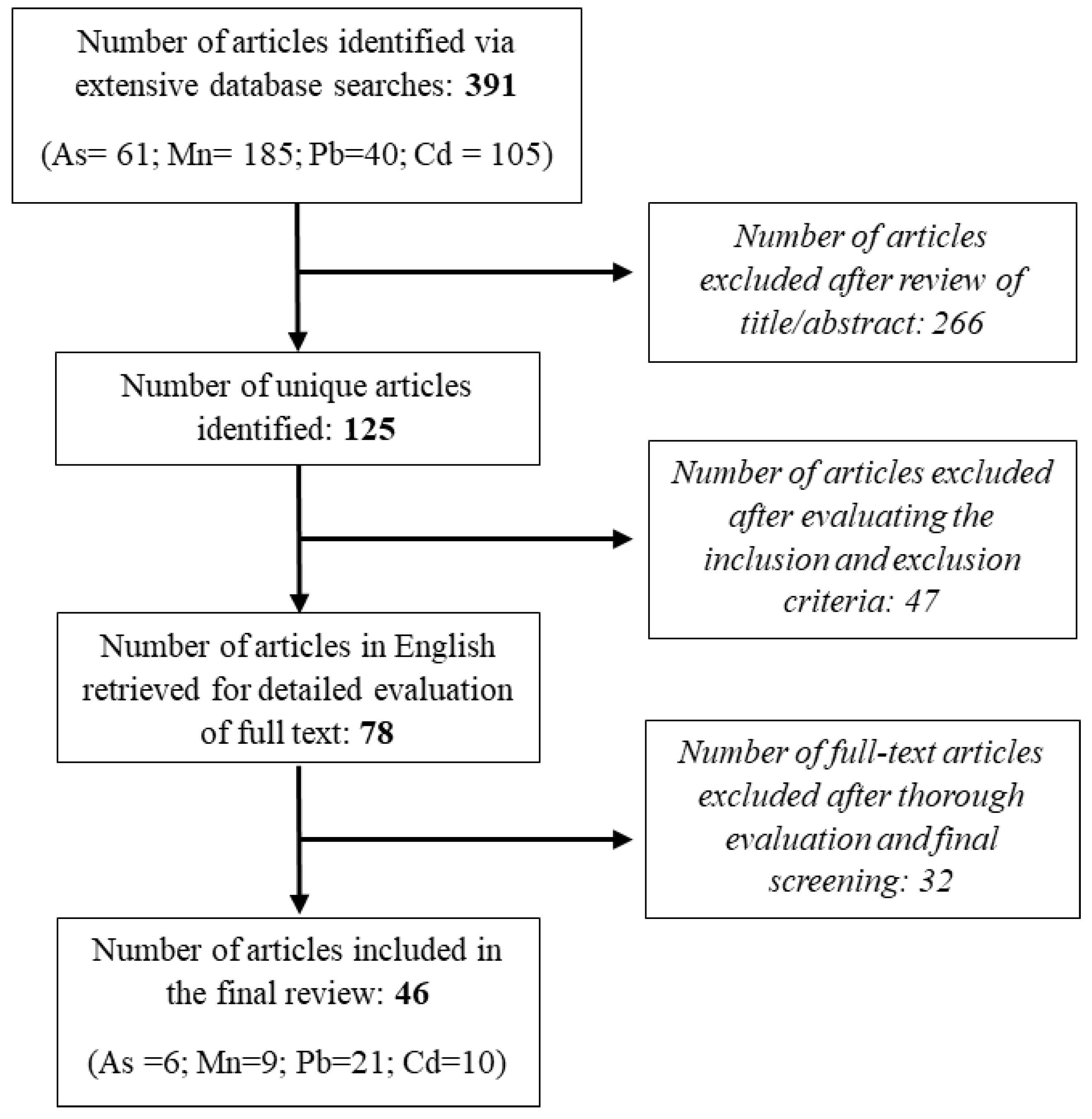

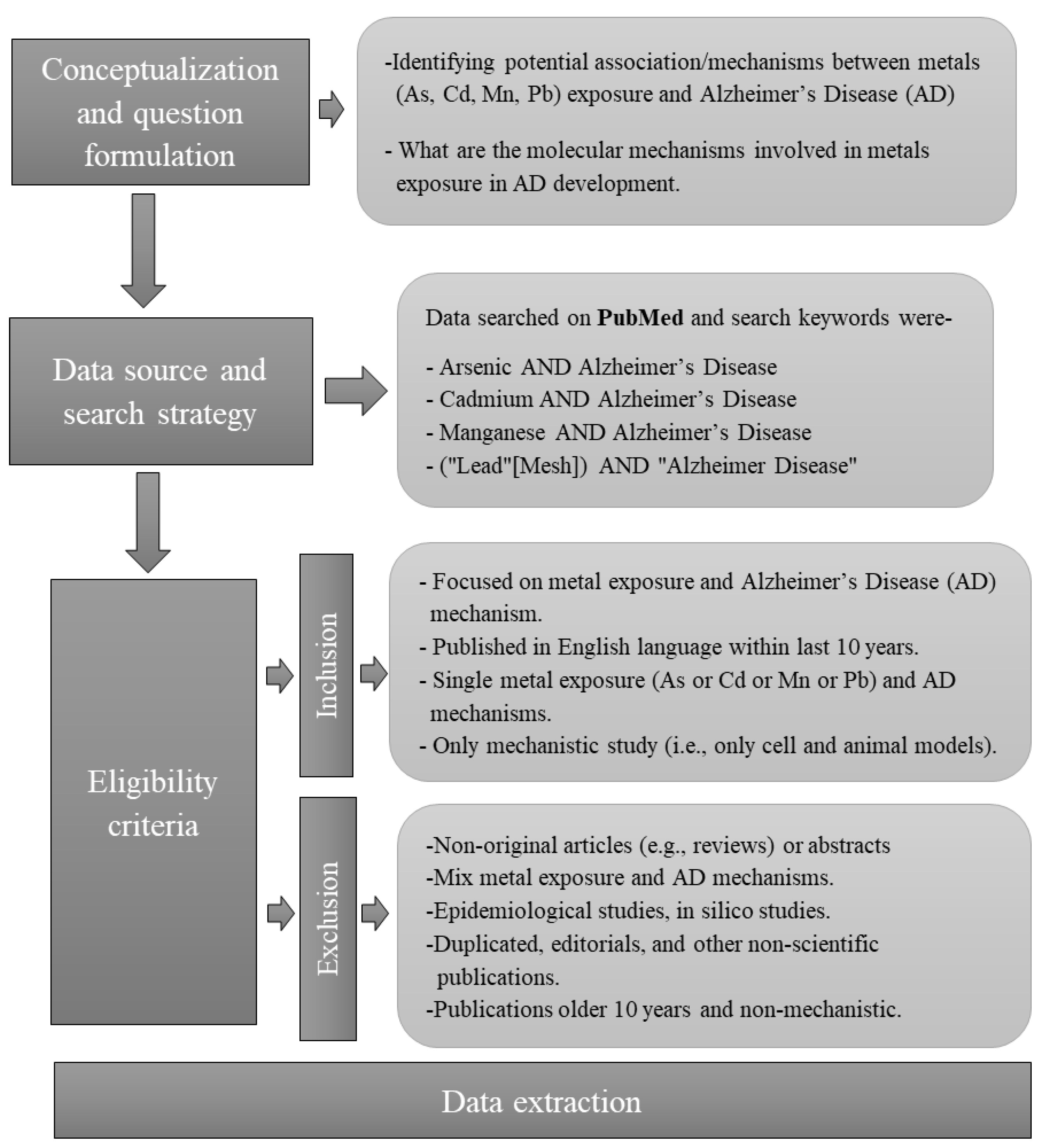

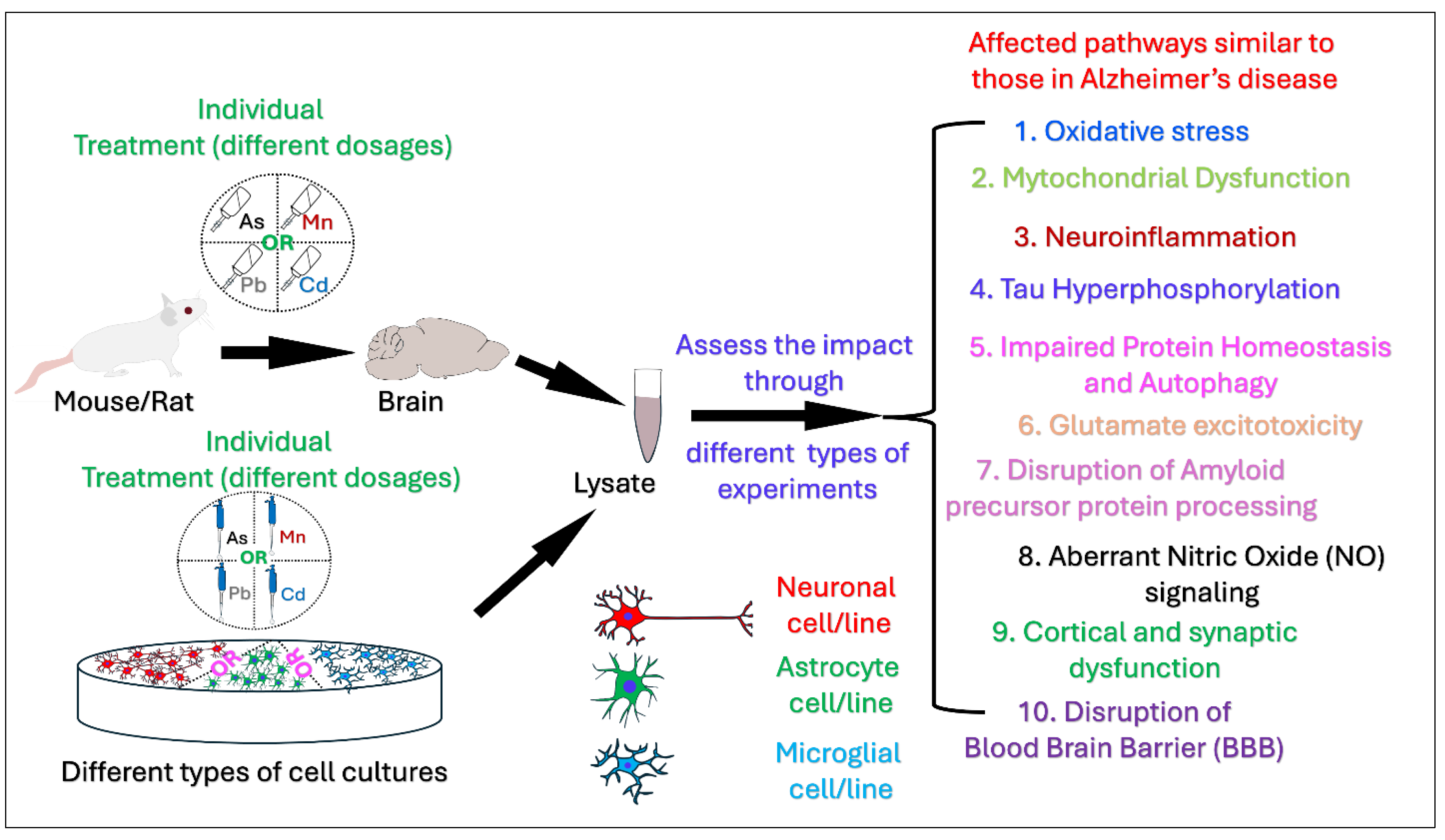

Numerous epidemiological studies indicate that populations exposed to environmental hazards such as heavy metals have a higher likelihood of developing Alzheimer's disease (AD) compared to those unexposed indicating a potential association between heavy metals exposure and Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD). The aim of this review is to summarize contemporary mechanistic research exploring the associations of four important metals, Arsenic (As), Manganese (Mn), Lead (Pb), and Cadmium (Cd) with AD and possible pathways, processes, and molecular mechanisms on the basis of data from the most recent mechanistic studies. Primary research publications published during the last decade, were located using a search of the PubMed Database. A thorough literature search and final screening yielded 46 original research articles for this review. Of the 46 papers, 6 pertain to As, 9 to Mn, 21 to Pb, and 10 to Cd exposures and AD pathobiology. Environmental exposure to these heavy metals induce a wide range of pathological processes that intersect with well-known mechanisms of AD, such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, protein aggregation, and neuroinflammation, autophagy dysfunction, and Tau hyperphosphorylation. While exposure to single metals shares some affected pathways, certain effects are unique to specific metals. For instance, Pb and Cd induce Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) disruption, whereas As and Mn are associated with neuroinflammation, glutamate excitotoxicity, impaired Amyloid Precursor Protein processing, aberrant Nitric Oxide (NO) signaling, and cortical and synaptic dysfunction. Our reivew provides a deeper understanding of biological mechanisms showing how metals contribute to AD. Information regarding the potential metal-induced neurotoxicity regarding AD may help us develop effective therapeutic AD intervention and treatment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criterion

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Mechanisms and Pathobiology of AD Development Related to Arsenic Exposure

3.1.1. Insights from Mouse Models of Arsenic Exposure

Arsenic and Bioenergetic Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease

Arsenic and Tau Phosphorylation: A Key Marker of AD

Arsenic-Induced Nitric Oxide Dysregulation and Neurotoxicity

3.1.2. Findings from Rat Models of Arsenic Exposure

Neurotoxicity and Amyloid-β Production, Synaptic and Cortical Changes

3.1.3. Mechanistic Insights from Cell Line: Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Aggregation

3.2. Mechanisms and Pathobiology of AD Development Related to Manganese Exposure

3.2.1. Cell line and Manganese Exposure

Drp1 Role in Neuroprotection and Mn-Induced Toxicity

Impact of Mn Exposure on Autophagy

Mn exposure Impairs Astrocytic Glutamate Transporter, EAAT2

REST Protects Dopaminergic Neurons Against Manganese-Induced Neurotoxicity

Glutamate Excitotoxicity in Mn-Induced Neurotoxicity

Role of Mn Exposure and NF-κB in Neuroinflammation

3.2.2. Mouse Model and/or cell Line Manganese Treatment

Manganese-Induced Toxicity Impairs Glutamatergic Signaling

Astrocytic REST (Repressor Element-1 Silencing Transcription Factor) Role in Mn-Induced Neurotoxicity

Mn-Induced Dysregulation Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP) Processing and Cognitive Impairment

3.3. Mechanisms and Pathobiology of AD Development Related to Lead Exposure

3.3.1. Mechanism of Pb-Induced AD Pathology in Mice/Cell Line

3.3.2. Mechanistic Insights from cell Line Studies

3.3.3. Insights from Rat Models of Lead Exposure

3.3.4. Findings from Zebrafish Models of Lead Exposure

3.4. Mechanisms and Pathobiology of AD Development Related to Cadmium Exposure

3.4.1. Insights from Mouse Models of Cadmium Exposure

3.4.2. Mechanistic Insights from Cell Line of Cadmium Exposure

3.4.3. Findings from Rat Models of Cadmium Exposure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

5.1. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, T., Khan, A., Alam, S. I., Ahmad, S., Ikram, M., Park, J. S., Lee, H. J., & Kim, M. O. (2021). Cadmium, an Environmental Contaminant, Exacerbates Alzheimer's Pathology in the Aged Mice's Brain. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 13, 650930. [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer's Association (2016). 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association, 12(4), 459–509. [CrossRef]

- Angon, P. B., Islam, M. S., Kc, S., Das, A., Anjum, N., Poudel, A., & Suchi, S. A. (2024). Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: Soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon, 10(7), e28357. [CrossRef]

- Arab, H. H., Eid, A. H., Yahia, R., Alsufyani, S. E., Ashour, A. M., El-Sheikh, A. A. K., Darwish, H. W., Saad, M. A., Al-Shorbagy, M. Y., & Masoud, M. A. (2023). Targeting Autophagy, Apoptosis, and SIRT1/Nrf2 Axis with Topiramate Underlies Its Neuroprotective Effect against Cadmium-Evoked Cognitive Deficits in Rats. Pharmaceuticals, 16(9), 1214. [CrossRef]

- Arora, S., Santiago, J. A., Bernstein, M., & Potashkin, J. A. (2023). Diet and lifestyle impact the development and progression of Alzheimer's dementia. Frontiers in nutrition, 10, 1213223. [CrossRef]

- Arruebarrena, M. A., Hawe, C. T., Lee, Y. M., & Branco, R. C. (2023). Mechanisms of Cadmium Neurotoxicity. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(23), 16558. [CrossRef]

- Ashleigh, T., Swerdlow, R. H., & Beal, M. F. (2023). The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association, 19(1), 333–342. [CrossRef]

- ATSDR. (2012). Toxicological profile for cadmium. Atlanta, GA Retrieved from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp5.pdf.

- Ayyalasomayajula, N., Ajumeera, R., Chellu, C. S., & Challa, S. (2019). Mitigative effects of epigallocatechin gallate in terms of diminishing apoptosis and oxidative stress generated by the combination of lead and amyloid peptides in human neuronal cells. Journal of biochemical and molecular toxicology, 33(11), e22393. [CrossRef]

- Bakulski, K. M., Seo, Y. A., Hickman, R. C., Brandt, D., Vadari, H. S., Hu, H., & Park, S. K. (2020). Heavy Metals Exposure and Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 76(4), 1215–1242. [CrossRef]

- Bakulski, K.M., Hu, H., Park, S.K., 2020. Lead, cadmium and Alzheimer’s disease. Genetics, neurol. Behav. diet dementia 813–830. [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, L. J. M., Ayyalasomayajula, N., Murumulla, L., Dixit, P. K., & Challa, S. (2022). Defective mitophagy and induction of apoptosis by the depleted levels of PINK1 and Parkin in Pb and β-amyloid peptide induced toxicity. Toxicology mechanisms and methods, 32(8), 559–568. [CrossRef]

- Bandaru, L. J. M., Murumulla, L., C, B. L., D, K. P., & Challa, S. (2023). Exposure of combination of environmental pollutant, lead (Pb) and β-amyloid peptides causes mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in human neuronal cells. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes, 55(1), 79–89. [CrossRef]

- Bellenguez, C., Küçükali, F., Jansen, I. E., Kleineidam, L., Moreno-Grau, S., Amin, N., Naj, A. C., Campos-Martin, R., Grenier-Boley, B., Andrade, V., Holmans, P. A., Boland, A., Damotte, V., van der Lee, S. J., Costa, M. R., Kuulasmaa, T., Yang, Q., de Rojas, I., Bis, J. C., Yaqub, A., … Lambert, J. C. (2022). New insights into the genetic etiology of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Nature genetics, 54(4), 412–436. [CrossRef]

- Bihaqi, S. W., Alansi, B., Masoud, A. M., Mushtaq, F., Subaiea, G. M., & Zawia, N. H. (2018). Influence of Early Life Lead (Pb) Exposure on α-Synuclein, GSK-3β and Caspase-3 Mediated Tauopathy: Implications on Alzheimer's Disease. Current Alzheimer research, 15(12), 1114–1122. [CrossRef]

- Bihaqi, S. W., Bahmani, A., Adem, A., & Zawia, N. H. (2014). Infantile postnatal exposure to lead (Pb) enhances tau expression in the cerebral cortex of aged mice: relevance to AD. Neurotoxicology, 44, 114–120. [CrossRef]

- Bird T. D. (2008). Genetic aspects of Alzheimer disease. Genetics in medicine, 10(4), 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Blacker, D., & Tanzi, R. E. (1998). The genetics of Alzheimer disease: current status and future prospects. Archives of neurology, 55(3), 294–296. [CrossRef]

- Branca, J. J. V., Fiorillo, C., Carrino, D., Paternostro, F., Taddei, N., Gulisano, M., Pacini, A., & Becatti, M. (2020). Cadmium-Induced Oxidative Stress: Focus on the Central Nervous System. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 9(6), 492. [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. E., Shah, P., Pollock, B. G., Gerretsen, P., & Graff-Guerrero, A. (2019). Lead (Pb) in Alzheimer's Dementia: A Systematic Review of Human Case- Control Studies. Current Alzheimer research, 16(4), 353–361. [CrossRef]

- Canfield, R. L., Jusko, T. A., & Kordas, K. (2005). Environmental lead exposure and children's cognitive function. Rivista italiana di pediatria = The Italian journal of pediatrics, 31(6), 293–300.

- Chib, S., & Singh, S. (2022). Manganese and related neurotoxic pathways: A potential therapeutic target in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotoxicology and teratology, 94, 107124. [CrossRef]

- Chin-Chan, M., Cobos-Puc, L., Alvarado-Cruz, I., Bayar, M., & Ermolaeva, M. (2019). Early-life Pb exposure as a potential risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: are there hazards for the Mexican population?. Journal of biological inorganic chemistry: JBIC : a publication of the Society of Biological Inorganic Chemistry, 24(8), 1285–1303. [CrossRef]

- Chin-Chan, M., Navarro-Yepes, J., & Quintanilla-Vega, B. (2015). Environmental pollutants as risk factors for neurodegenerative disorders: Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 9, 124. [CrossRef]

- Del Pino, J., Zeballos, G., Anadón, M. J., Moyano, P., Díaz, M. J., García, J. M., & Frejo, M. T. (2016). Cadmium-induced cell death of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons mediated by muscarinic M1 receptor blockade, increase in GSK-3β enzyme, β-amyloid and tau protein levels. Archives of toxicology, 90(5), 1081–1092. [CrossRef]

- Deng, P., Fan, T., Gao, P., Peng, Y., Li, M., Li, J., Qin, M., Hao, R., Wang, L., Li, M., Zhang, L., Chen, C., He, M., Lu, Y., Ma, Q., Luo, Y., Tian, L., Xie, J., Chen, M., Xu, S., … Pi, H. (2024). SIRT5-Mediated Desuccinylation of RAB7A Protects Against Cadmium-Induced Alzheimer's Disease-Like Pathology by Restoring Autophagic Flux. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany), 11(30), e2402030. [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M. A., & Dickson, D. W. (2019). The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Molecular neurodegeneration, 14(1), 32. [CrossRef]

- Dhapola, R., Beura, S. K., Sharma, P., Singh, S. K., & HariKrishnaReddy, D. (2024). Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease: current knowledge of signaling pathways and therapeutics. Molecular biology reports, 51(1), 48. [CrossRef]

- Dosunmu, R., Wu, J., Basha, M. R., & Zawia, N. H. (2007). Environmental and dietary risk factors in Alzheimer's disease. Expert review of neurotherapeutics, 7(7), 887–900. [CrossRef]

- Eid, A., Bihaqi, S. W., Hemme, C., Gaspar, J. M., Hart, R. P., & Zawia, N. H. (2018). Histone acetylation maps in aged mice developmentally exposed to lead: epigenetic drift and Alzheimer-related genes. Epigenomics, 10(5), 573–583. [CrossRef]

- Eid, A., Bihaqi, S. W., Renehan, W. E., & Zawia, N. H. (2016). Developmental lead exposure and lifespan alterations in epigenetic regulators and their correspondence to biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2, 123–131. [CrossRef]

- Fan, R. Z., Sportelli, C., Lai, Y., Salehe, S. S., Pinnell, J. R., Brown, H. J., Richardson, J. R., Luo, S., & Tieu, K. (2024). A partial Drp1 knockout improves autophagy flux independent of mitochondrial function. Molecular neurodegeneration, 19(1), 26. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators (2022). Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7, e105–e125 e105–e125. [CrossRef]

- Gella, A., & Durany, N. (2009). Oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Cell adhesion & migration, 3(1), 88–933(1), 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Gong, G., & OʼBryant, S. E. (2010). The arsenic exposure hypothesis for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders, 24(4), 311–316. [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P., & Bellanger, M. (2017). Calculation of the disease burden associated with environmental chemical exposures: application of toxicological information in health economic estimation. Environmental health : a global access science source, 16(1), 123. [CrossRef]

- Gu, H., Territo, P. R., Persohn, S. A., Bedwell, A. A., Eldridge, K., Speedy, R., Chen, Z., Zheng, W., & Du, Y. (2020). Evaluation of chronic lead effects in the blood brain barrier system by DCE-CT. Journal of trace elements in medicine and biology, 62, 126648. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T., Zhang, D., Zeng, Y., Huang, T. Y., Xu, H., & Zhao, Y. (2020). Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Molecular neurodegeneration, 15(1), 40. [CrossRef]

- Henderson A. S. (1988). The risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a review and a hypothesis. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica, 78(3), 257–275. [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M. T., Carson, M. J., El Khoury, J., Landreth, G. E., Brosseron, F., Feinstein, D. L., Jacobs, A. H., Wyss-Coray, T., Vitorica, J., Ransohoff, R. M., Herrup, K., Frautschy, S. A., Finsen, B., Brown, G. C., Verkhratsky, A., Yamanaka, K., Koistinaho, J., Latz, E., Halle, A., Petzold, G. C., … Kummer, M. P. (2015). Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet. Neurology, 14(4), 388–405. [CrossRef]

- Hippius, H., & Neundörfer, G. (2003). The discovery of Alzheimer's disease. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 5(1), 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Horton, C. J., Weng, H. Y., & Wells, E. M. (2019). Association between blood lead level and subsequent Alzheimer's disease mortality. Environmental epidemiology (Philadelphia, Pa.), 3(3), e045. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D., Chen, L., Ji, Q., Xiang, Y., Zhou, Q., Chen, K., Zhang, X., Zou, F., Zhang, X., Zhao, Z., Wang, T., Zheng, G., & Meng, X. (2024). Lead aggravates Alzheimer's disease pathology via mitochondrial copper accumulation regulated by COX17. Redox biology, 69, 102990. [CrossRef]

- Huat, T. J., Camats-Perna, J., Newcombe, E. A., Valmas, N., Kitazawa, M., & Medeiros, R. (2019). Metal Toxicity Links to Alzheimer's Disease and Neuroinflammation. Journal of molecular biology, 431(9), 1843–1868. [CrossRef]

- Ijomone, O. M., Ijomone, O. K., Iroegbu, J. D., Ifenatuoha, C. W., Olung, N. F., & Aschner, M. (2020). Epigenetic influence of environmentally neurotoxic metals. Neurotoxicology, 81, 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Islam, F., Shohag, S., Akhter, S., Islam, M. R., Sultana, S., Mitra, S., Chandran, D., Khandaker, M. U., Ashraf, G. M., Idris, A. M., Emran, T. B., & Cavalu, S. (2022). Exposure of metal toxicity in Alzheimer's disease: An extensive review. Frontiers in pharmacology, 13, 903099. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. H., Ge, G., Gao, K., Pang, Y., Chai, R. C., Jia, X. H., Kong, J. G., & Yu, A. C. (2015). Calcium Signaling Involvement in Cadmium-Induced Astrocyte Cytotoxicity and Cell Death Through Activation of MAPK and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathways. Neurochemical research, 40(9), 1929–1944. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M., Joshi, S., Khambete, M., & Degani, M. (2023). Role of calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease and its therapeutic implications. Chemical biology & drug design, 101(2), 453–468. [CrossRef]

- Kirkley, K. S., Popichak, K. A., Afzali, M. F., Legare, M. E., & Tjalkens, R. B. (2017). Microglia amplify inflammatory activation of astrocytes in manganese neurotoxicity. Journal of neuroinflammation, 14(1), 99. [CrossRef]

- Lanoiselée, H. M., Nicolas, G., Wallon, D., Rovelet-Lecrux, A., Lacour, M., Rousseau, S., Richard, A. C., Pasquier, F., Rollin-Sillaire, A., Martinaud, O., Quillard-Muraine, M., de la Sayette, V., Boutoleau-Bretonniere, C., Etcharry-Bouyx, F., Chauviré, V., Sarazin, M., le Ber, I., Epelbaum, S., Jonveaux, T., Rouaud, O., … collaborators of the CNR-MAJ project (2017). APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 mutations in early-onset Alzheimer disease: A genetic screening study of familial and sporadic cases. PLoS medicine, 14(3), e1002270. [CrossRef]

- Lau, V., Ramer, L., & Tremblay, M. È. (2023). An aging, pathology burden, and glial senescence build-up hypothesis for late onset Alzheimer's disease. Nature communications, 14(1), 1670. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Freeman, J. L. (2016). Embryonic exposure to 10 μg L(-1) lead results in female-specific expression changes in genes associated with nervous system development and function and Alzheimer's disease in aged adult zebrafish brain. Metallomics : integrated biometal science, 8(6), 589–596. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Freeman, J. L. (2020). Exposure to the Heavy-Metal Lead Induces DNA Copy Number Alterations in Zebrafish Cells. Chemical research in toxicology, 33(8), 2047–2053. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Peterson, S. M., & Freeman, J. L. (2017). Sex-specific characterization and evaluation of the Alzheimer's disease genetic risk factor sorl1 in zebrafish during aging and in the adult brain following a 100 ppb embryonic lead exposure. Journal of applied toxicology: JAT, 37(4), 400–407. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. X., Talukder, M., Xu, Y. R., Zhu, S. Y., Wang, Y. X., & Li, J. L. (2024). Cadmium causes cerebral mitochondrial dysfunction through regulating mitochondrial HSF1. Environmental pollution, 360, 124677. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Feng, X., Sun, X., Hou, N., Han, F., & Liu, Y. (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990-2019. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 14, 937486. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Xie, Y., Lu, Y., Zhao, Z., Zhuang, Z., Yang, L., Huang, H., Li, H., Mao, Z., Pi, S., Chen, F., & He, Y. (2023). APP/PS1 Gene-Environmental Cadmium Interaction Aggravates the Progression of Alzheimer's Disease in Mice via the Blood-Brain Barrier, Amyloid-β, and Inflammation. Journal of Alzheimer's disease: JAD, 94(1), 115–136. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. L., Shen, X., Gu, H., Zhao, G., Du, Y., & Zheng, W. (2023). High affinity of β-amyloid proteins to cerebral capillaries: implications in chronic lead exposure-induced neurotoxicity in rats. Fluids and barriers of the CNS, 20(1), 32. [CrossRef]

- Lokesh, M., Bandaru, L. J. M., Rajanna, A., Rao, J. S., & Challa, S. (2024). Unveiling Potential Neurotoxic Mechansisms: Pb-Induced Activation of CDK5-p25 Signaling Axis in Alzheimer's Disease Development, Emphasizing CDK5 Inhibition and Formation of Toxic p25 Species. Molecular neurobiology, 61(5), 3090–3103. [CrossRef]

- Lu, C., Meng, Z., He, Y., Xiao, D., Cai, H., Xu, Y., Liu, X., Wang, X., Mo, L., Liang, Z., Wei, X., Ao, Q., Liang, B., Li, X., Tang, S., & Guo, S. (2018). Involvement of gap junctions in astrocyte impairment induced by manganese exposure. Brain research bulletin, 140, 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Martin, K., Huggins, T., King, C., Carroll, M. A., & Catapane, E. J. (2008). The neurotoxic effects of manganese on the dopaminergic innervation of the gill of the bivalve mollusc, Crassostrea virginica. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Toxicology & pharmacology, 148(2), 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Martins, A. C., Jr, Morcillo, P., Ijomone, O. M., Venkataramani, V., Harrison, F. E., Lee, E., Bowman, A. B., & Aschner, M. (2019). New Insights on the Role of Manganese in Alzheimer's Disease and Parkinson's Disease. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(19), 3546. [CrossRef]

- Masoud, A. M., Bihaqi, S. W., Machan, J. T., Zawia, N. H., & Renehan, W. E. (2016). Early-Life Exposure to Lead (Pb) Alters the Expression of microRNA that Target Proteins Associated with Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 51(4), 1257–1264. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M. T., Wang, H., Abel, G. M., & Xia, Z. (2023). Inducible and Conditional Activation of Adult Neurogenesis Rescues Cadmium-Induced Hippocampus-Dependent Memory Deficits in ApoE4-KI Mice. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(11), 9118. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, R., Baglietto-Vargas, D., & LaFerla, F. M. (2011). The role of tau in Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 17(5), 514–524. [CrossRef]

- Min, J. Y., & Min, K. B. (2016). Blood cadmium levels and Alzheimer's disease mortality risk in older US adults. Environmental health : a global access science source, 15(1), 69. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. P., and LeVine, H., 3rd (2010). Alzheimer's disease and the amyloid-beta peptide. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 19(1), 311–323. [CrossRef]

- Neuwirth, L. S., Lopez, O. E., Schneider, J. S., & Markowitz, M. E. (2020). Low-level Lead Exposure Impairs Fronto-executive Functions: A Call to Update the DSM-5 with Lead Poisoning as a Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Psychology & neuroscience, 13(3), 299–325. [CrossRef]

- Niño, S. A., Martel-Gallegos, G., Castro-Zavala, A., Ortega-Berlanga, B., Delgado, J. M., Hernández-Mendoza, H., Romero-Guzmán, E., Ríos-Lugo, J., Rosales-Mendoza, S., Jiménez-Capdeville, M. E., & Zarazúa, S. (2018b). Chronic Arsenic Exposure Increases Aβ (1-42) Production and Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products Expression in Rat Brain. Chemical research in toxicology, 31(1), 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Niño, S. A., Morales-Martínez, A., Chi-Ahumada, E., Carrizales, L., Salgado-Delgado, R., Pérez-Severiano, F., Díaz-Cintra, S., Jiménez-Capdeville, M. E., & Zarazúa, S. (2018a). Arsenic Exposure Contributes to the Bioenergetic Damage in an Alzheimer's Disease Model. ACS chemical neuroscience, 10(1), 323–336. [CrossRef]

- Niño, S. A., Vázquez-Hernández, N., Arevalo-Villalobos, J., Chi-Ahumada, E., Martín-Amaya-Barajas, F. L., Díaz-Cintra, S., Martel-Gallegos, G., González-Burgos, I., & Jiménez-Capdeville, M. E. (2021). Cortical Synaptic Reorganization Under Chronic Arsenic Exposure. Neurotoxicity research, 39(6), 1970–1980. [CrossRef]

- Notarachille, G., Arnesano, F., Calò, V., & Meleleo, D. (2014). Heavy metals toxicity: effect of cadmium ions on amyloid beta protein 1-42. Possible implications for Alzheimer's disease. Biometals: an international journal on the role of metal ions in biology, biochemistry, and medicine, 27(2), 371–388. [CrossRef]

- Pajarillo, E., Demayo, M., Digman, A., Nyarko-Danquah, I., Son, D. S., Aschner, M., & Lee, E. (2022). Deletion of RE1-silencing transcription factor in striatal astrocytes exacerbates manganese-induced neurotoxicity in mice. Glia, 70(10), 1886–1901. [CrossRef]

- Pajarillo, E., Rizor, A., Son, D. S., Aschner, M., & Lee, E. (2020). The transcription factor REST up-regulates tyrosine hydroxylase and antiapoptotic genes and protects dopaminergic neurons against manganese toxicity. The Journal of biological chemistry, 295(10), 3040–3054. [CrossRef]

- Pakzad, D., Akbari, V., Sepand, M. R., & Aliomrani, M. (2021). Risk of neurodegenerative disease due to tau phosphorylation changes and arsenic exposure via drinking water. Toxicology research, 10(2), 325–333. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q., Bakulski, K. M., Nan, B., & Park, S. K. (2017). Cadmium and Alzheimer's disease mortality in U.S. adults: Updated evidence with a urinary biomarker and extended follow-up time. Environmental research, 157, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Peres, T. V., Schettinger, M. R., Chen, P., Carvalho, F., Avila, D. S., Bowman, A. B., & Aschner, M. (2016). "Manganese-induced neurotoxicity: a review of its behavioral consequences and neuroprotective strategies". BMC pharmacology & toxicology, 17(1), 57. [CrossRef]

- Qian, B., Li, T. Y., Zheng, Z. X., Zhang, H. Y., Xu, W. Q., Mo, S. M., Cui, J. J., Chen, W. J., Lin, Y. C., & Lin, Z. N. (2024). The involvement of SigmaR1K142 degradation mediated by ERAD in neural senescence linked with CdCl2 exposure. Journal of hazardous materials, 472, 134466. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M. S., Mise, N., & Ichihara, S. (2022). Arsenic contamination in food chain in Bangladesh: A review on health hazards, socioeconomic impacts and implications. Hygiene and Environmental Health Advances, 2, 100004. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M. S., Rahman, M. M., Mise, N., Sikder, M. T., Ichihara, G., Uddin, M. K., Kurasaki, M., & Ichihara, S. (2021). Environmental arsenic exposure and its contribution to human diseases, toxicity mechanism and management. Environmental pollution, 289, 117940. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A., Hannan, M. A., Uddin, M. J., Rahman, M. S., Rashid, M. M., & Kim, B. (2021). Exposure to Environmental Arsenic and Emerging Risk of Alzheimer's Disease: Perspective Mechanisms, Management Strategy, and Future Directions. Toxics, 9(8), 188. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A., Rahman, M. S., Uddin, M. J., Mamum-Or-Rashid, A. N. M., Pang, M. G., & Rhim, H. (2020). Emerging risk of environmental factors: insight mechanisms of Alzheimer's diseases. Environmental science and pollution research international, 27(36), 44659–44672. [CrossRef]

- Reuben A. (2018). Childhood Lead Exposure and Adult Neurodegenerative Disease. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 64(1), 17–42. [CrossRef]

- Rizor, A., Pajarillo, E., Nyarko-Danquah, I., Digman, A., Mooneyham, L., Son, D. S., Aschner, M., & Lee, E. (2021). Manganese-induced reactive oxygen species activate IκB kinase to upregulate YY1 and impair glutamate transporter EAAT2 function in human astrocytes in vitro. Neurotoxicology, 86, 94–103. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J. T., Venkataramani, V., Washburn, C., Liu, Y., Tummala, V., Jiang, H., Smith, A., & Cahill, C. M. (2016). A role for amyloid precursor protein translation to restore iron homeostasis and ameliorate lead (Pb) neurotoxicity. Journal of neurochemistry, 138(3), 479–494. [CrossRef]

- Rostagno A. A. (2022). Pathogenesis of Alzheimer's Disease. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(1), 107. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, T., Liu, Y., Buchner, V., & Tchounwou, P. B. (2009). Neurotoxic effects and biomarkers of lead exposure: a review. Reviews on environmental health, 24(1), 15–45. [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S., Garrett, S. H., Sens, M. A., & Sens, D. A. (2010). Cadmium, environmental exposure, and health outcomes. Environmental health perspectives, 118(2), 182–190. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, O., & Coleman, M. (2020). Alzheimer’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology and Pathogenesis. In X. Huang (Ed.), Alzheimer’s Disease: Drug Discovery. Exon Publications.

- Spitznagel, B. D., Buchanan, R. A., Consoli, D. C., Thibert, M. K., Bowman, A. B., Nobis, W. P., & Harrison, F. E. (2023). Acute manganese exposure impairs glutamatergic function in a young mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurotoxicology, 95, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Straif, K., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., et al. (2009). A review of human carcinogensepart C: Metals, arsenic, dusts, and fibres. The Lancet Oncology, 10(5), 453e454.

- Suresh, S., Singh S, A., Rushendran, R., Vellapandian, C., & Prajapati, B. (2023). Alzheimer's disease: the role of extrinsic factors in its development, an investigation of the environmental enigma. Frontiers in neurology, 14, 1303111. [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P. B., Yedjou, C. G., Patlolla, A. K., & Sutton, D. J. (2012). Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Experientia supplementum (2012), 101, 133–164. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M. K., Kartawy, M., Ginzburg, S., & Amal, H. (2022). Arsenic alters nitric oxide signaling similar to autism spectrum disorder and Alzheimer's disease-associated mutations. Translational psychiatry, 12(1), 127. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y., Yang, H., Tian, X., Wang, H., Zhou, T., Zhang, S., Yu, J., Zhang, T., Fan, D., Guo, X., Tabira, T., Kong, F., Chen, Z., Xiao, W., & Chui, D. (2014). High manganese, a risk for Alzheimer's disease: high manganese induces amyloid-β related cognitive impairment. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD, 42(3), 865–878. [CrossRef]

- Tyczyńska, M., Gędek, M., Brachet, A., Stręk, W., Flieger, J., Teresiński, G., & Baj, J. (2024). Trace Elements in Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia: The Current State of Knowledge. Journal of clinical medicine, 13(8), 2381. [CrossRef]

- Tyler, C. R., & Allan, A. M. (2014). The Effects of Arsenic Exposure on Neurological and Cognitive Dysfunction in Human and Rodent Studies: A Review. Current environmental health reports, 1(2), 132–147. [CrossRef]

- vonderEmbse, A. N., Hu, Q., & DeWitt, J. C. (2017). Developmental toxicant exposure in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease induces differential sex-associated microglial activation and increased susceptibility to amyloid accumulation. Journal of developmental origins of health and disease, 8(4), 493–501. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Zhang, L., Xia, Z., & Cui, J. Y. (2022). Effect of Chronic Cadmium Exposure on Brain and Liver Transporters and Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes in Male and Female Mice Genetically Predisposed to Alzheimer's Disease. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals, 50(10), 1414–1428. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R., Wu, Z., Liu, R., Bai, L., Lin, Y., Ba, Y., & Huang, H. (2022). Age-related miRNAs dysregulation and abnormal BACE1 expression following Pb exposure in adolescent mice. Environmental toxicology, 37(8), 1902–1913. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Huang, X., Zhou, L., Chen, J., Zhang, X., Xu, K., Huang, Z., He, M., Shen, M., Chen, X., Tang, B., Shen, L., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Association of arsenic exposure and cognitive impairment: A population-based cross-sectional study in China. Neurotoxicology, 82, 100–107. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2010). Exposure to lead: A major public health concern. World health organization, preventing disease through healthy environments.

- Wisessaowapak, C., Visitnonthachai, D., Watcharasit, P., & Satayavivad, J. (2021). Prolonged arsenic exposure increases tau phosphorylation in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells: The contribution of GSK3 and ERK1/2. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology, 84, 103626. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Liu, H., Zhao, H., Wang, X., Chen, J., Xia, D., Xiao, C., Cheng, J., Zhao, Z., & He, Y. (2020). Environmental lead exposure aggravates the progression of Alzheimer's disease in mice by targeting on blood brain barrier. Toxicology letters, 319, 138–147. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X., Jiang, Q., McDermott, J., & Han, J. J. (2018). Aging and Alzheimer's disease: Comparison and associations from molecular to system level. Aging cell, 17(5), e12802. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Wu, S., Szadowski, H., Min, S., Yang, Y., Bowman, A. B., Rochet, J. C., Freeman, J. L., & Yuan, C. (2023). Developmental Pb exposure increases AD risk via altered intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in hiPSC-derived cortical neurons. The Journal of biological chemistry, 299(8), 105023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Wei, L., Tang, S., Shi, Q., Wu, B., Yang, X., Zou, Y., Wang, X., Ao, Q., Meng, L., Wei, X., Zhang, N., Li, Y., Lan, C., Chen, M., Li, X., & Lu, C. (2021). Regulation PP2Ac methylation ameliorating autophagy dysfunction caused by Mn is associated with mTORC1/ULK1 pathway. Food and chemical toxicology, 156, 112441. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Zhang, J., Yang, X., Li, Z., Wang, J., Lu, C., Nan, A., & Zou, Y. (2021). Dysregulated APP expression and α-secretase processing of APP is involved in manganese-induced cognitive impairment. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 220, 112365. [CrossRef]

- Yegambaram, M., Manivannan, B., Beach, T. G., & Halden, R. U. (2015). Role of environmental contaminants in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease: a review. Current Alzheimer research, 12(2), 116–146. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. T., Chang, R. C., & Tan, L. (2009). Calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Progress in neurobiology, 89(3), 240–255. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y., Chen, R., Mao, K., Deng, M., & Li, Z. (2024). The Role of Glial Cells in Synaptic Dysfunction: Insights into Alzheimer's Disease Mechanisms. Aging and disease, 15(2), 459–479. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Matsushita, M., Zhang, L., Wang, H., Shi, X., Gu, H., Xia, Z., & Cui, J. Y. (2021). Cadmium exposure modulates the gut-liver axis in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Communications biology, 4(1), 1398. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A., Matsushita, M., Zhang, L., Wang, H., Shi, X., Gu, H., Xia, Z., & Cui, J. Y. (2021). Cadmium exposure modulates the gut-liver axis in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Communications biology, 4(1), 1398. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Wang, H., Abel, G. M., Storm, D. R., & Xia, Z. (2020). The Effects of Gene-Environment Interactions Between Cadmium Exposure and Apolipoprotein E4 on Memory in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Toxicological sciences, 173(1), 189–201. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. C., Gao, Z. Y., Wang, J., Wu, M. Q., Hu, S., Chen, F., Liu, J. X., Pan, H., & Yan, C. H. (2018). Lead exposure induces Alzheimers's disease (AD)-like pathology and disturbes cholesterol metabolism in the young rat brain. Toxicology letters, 296, 173–183. [CrossRef]

| SL | References | Study objective | Study type | Exposure | Outcomes | Key Findings |

| 1 | Tripathi et al., 2022 | Investigated nitric oxide signaling in arsenic neurotoxicity using mice model. | Mice model | Mice- drinking water | AD and ASD | Low doses arsenic exposure disrupts the S-nitrosylation (SNO) signaling in the striatum and hippocampus, affecting key proteins, mitochondrial respiratory function, endogenous antioxidant systems, transcriptional regulation, cytoskeleton maintenance, and regulation of apoptosis. This disruption leads to impaired neurodevelopment, neuronal function, and cell viability, resembling features of ASD and AD pathobiology. |

| 2 | Niño et al., 2021 | Investigated synaptic structure (cortical microstructure and synapses) in chronic arsenic exposure using both a triple-transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model and Wistar rats. | Triple-transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model and Wistar rats | Rats- drinking water | Cognitive impairment (AD) | Chronic arsenic exposure alters cortical microstructure and synaptic connectivity as indicated by high ADC and low FA, suggesting structural reorganization. Dendritic spine density increased at 2 months but decreased at 4 months. Synaptophysin levels increased at 2 months, remained stable at 4 months while PSD-95 protein levels decreased in arsenic-exposed groups at 4 months suggesting arsenic affects development and stabilization of dendritic complexity. |

| 3 | Wisessaowapak et al, 2021 | Investigated and determined whether prolonged exposure to arsenic affected the phosphorylation of wild-type tau in the neuronal cell model (SH-SY5Y Cells). | SH-SY5Y Cells | Cells | AD | Prolonged arsenic exposure increases tau phosphorylation in neurons, reducing dephosphorylated tau and elevates pS202 tau and GSK3β activity, leading to tau hyperphosphorylation. This enhances insoluble tau aggregation in cells, suggesting a link to sporadic Alzheimer's disease. |

| 4 | Pakzad et al., 2021 | Investigated the correlation between arsenic trioxide exposure and its impact on the tau protein Ser262 phosphorylation after 3 months of exposure via drinking water in male mice. | Mice model | Mice- drinking water | AD | Arsenic accumulation in the brain, likely due to the BBB integrity disruption. Tau phosphorylation at Ser262 increased significantly after 3 months of exposure to 10 ppm arsenic. Low arsenic levels may raise the risk of neurodegenerative disease. |

| 5 | Niño et al., 2018a | Investigated arsenic exposure and the pathophysiological progress of AD using the 3xTgAD mouse model. | 3xTgAD mouse model | Mice-drinking water | AD | Chronic arsenic exposure exacerbates AD-like pathology in mice potentially triggering neurodegeneration through mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to behavioral deficits, cognitive decline, sleep disturbances, altered circadian rhythm and locomotor activity. Exposed mice also exhibited elevated level of amyloid and tau along with oxidative stress and energy deficits in the hippocampus. Early life exposure poses major risks for cognitive decline. |

| 6 | Niño et al., 2018b | Investigated the effects of chronic arsenic exposure on the production and elimination of Amyloid-β (Aβ) in Wistar rats. | Male Wistar rats | Rats- drinking water | AD | Chronic arsenic exposure leads to cognitive deficits in rats, increasing Aβ (1−42) production, BACE1 enzymatic activity and elevating receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) levels (approximately 220-fold). Behavioral deficits observed in in fear conditioning test. No changes in LRP1 expression were noted with arsenic exposure. Arsenic exposure disrupts amyloid clearance equilibrium in the brain, supporting it's role in neurodegenerative disease development. |

| SL | References | Study objective | Study type | Exposure | Outcomes | Key Findings |

| 1 | Fan et al. 2024 | Investigated the role of Drp1 in manganese exposure induced autophagy and mitochondrial function. Determined if Drp1 inhibition improves autophagy independent of mitochondria. | Mechanistic-HeLa cells, N27 neuronal cells and mice | Cells and mice-orally gavage | PD and AD | Manganese exposure impairs autophagy without affecting mitochondria at low concentration. Partial Drp1 inhibition improves autophagy flux independently of mitochondrial function. Drp1 knockdown reduces protein aggregation in neurological disorders. Autophagy pathways are dysregulated in mouse models treated with manganese. Drp1 inhibition protects against manganese-induced autophagic impairment. This study highlights autophagy as a target of low manganese exposure. |

| 2 | Spitznagel et al., 2023 | Investigated acute Mn exposure effects on glutamatergic neurotransmission, evaluated glutamate clearance dynamics in astrocytes post-Mn exposure, investigated behavioral consequences of Mn exposure in AD models and identified vulnerabilities to Mn exposure in pre-symptomatic AD phases. | Mice and Primary astrocytes | Mice and Primary Astrocytes-Drinking water | AD | Manganese exposure altered glutamate clearance in astrocytes, increased cortical GLAST expression, and increases seizure susceptibility in APP/PSEN1 mice. No changes were observed in hippocampal long-term potentiation after manganese exposure. Acute manganese exposure lead to glutamatergic dyshomeostasis which may contribute to early Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. |

| 3 | Pajarillo et al., 2022 | Investigated the effects of astrocyte-specific deletion of REST in the striatum of Mn-exposed mice to test if astrocytic REST modulates Mn toxicity. In short, it investigated astrocytic REST's role in Mn-induced neurotoxicity, assessed locomotor and cognitive function impairment, and evaluated the impact of astrocytic REST deletion on proinflammatory factors. | Mice and Primary astrocytes | Mice and Primary Astrocytes-Nostril | PD, AD | Astrocytic REST deletion in the striatum of the mouse brain exacerbated Mn-induced toxicity, including nigrostriatal dopaminergic dysfunctions, motor deficits, and cognitive impairment, along with molecular changes in inflammation and glutamate transporter GLT-1. Astrocytic REST deletion worsened manganese-induced neurotoxicity in mice. |

| 4 | Xu et al., 2021 | Investigated Mn-induced autophagy dysfunction in N2a cells, explored the role of PP2Ac methylation in autophagy regulation, evaluated the effects of ABL-127 on PP2Ac methylation and assessed the impact of LCMT1 overexpression on autophagy. | N2a cells | N2a cells | PD, AD | This study demonstrated that autophagy disruption is related to cytotoxicity caused by Mn in N2a cells. mTORC1/ULK1 activation and PP2Ac demethylation contribute to autophagy modulation, and methylated PP2Ac can ameliorate autophagy dysfunction by inactivating mTORC1/ULK1 and reducing oxidation. It also suggests that the regulation of PP2Ac methylation is a promising research direction for the prevention and treatment of Mn neurotoxicity and even neurodegenerative diseases. |

| 5 | Rizor et al., 2021 | Investigated Mn-induced YY1 activation via the NF-kB pathway and examined mechanisms impairing EAAT2 function in astrocytes. | H4 human astrocyte cells | Cells | PD, AD | Results demonstrate that Mn exposure induced oxidative stress and TNF-α production, leading to the canonical phosphorylation of the upstream kinase IKK-β, increased YY1 promoter activity and mRNA/protein levels, and consequent EAAT2 repression. Mn exposure activates IκB kinase, impairing EAAT2 function. The NF-κB signaling pathway mediates YY1 activation by Mn. Oxidative stress and TNF-α are upstream of IKK-β activation. |

| 6 | Yang et al., 2021 | Investigated Mn-induced cognitive impairment mechanisms by assessing the role of APP in cognitive deficits, evaluating APP's secretase processing in neurotoxicity, exploring synaptic dysfunction by using both in vivo mouse model and in vitro cell culture (N2a cells). | astrocyte cell | Mice and N2a cells-gastric gavage | AD | Manganese exposure impairs cognition in mouse models, inhibits APP expression and α-secretase activity. No effect on β-secretase levels or activity was observed. Mn-induced cognitive impairment is related to synaptic dysfunction. The findings suggest similarities to early Alzheimer's disease mechanisms. Dysregulated APP processing contributes to cognitive deficits caused by manganese. s |

| 7 | Pajarillo et al., 2020 | Investigated the role of RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST) in dopaminergic neurons against Mn-induced toxicity and exmined the enhancement of the expression of the dopamine-synthesizing enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) | Neuronal cell lines (Mouse CAD cell line and LUHMES (CRL-2927) cell line) | Cells | PD, AD | The findings indicated that REST upregulates tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression in dopaminergic neurons and protects neurons from manganese (Mn)-induced toxicity by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, inhibiting proapoptotic proteins, nhancing antiapoptotic proteins and promoting the expression of antioxidant proteins like catalase and Nrf2. REST also binds to RE1 sites in the TH promoter. Therefore, REST's dysfunction is linked to Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. Finally, it was revealed that REST activates TH expression and thereby protects neurons against Mn-induced toxicity and neurological disorders associated with dopaminergic neurodegeneration. |

| 8 | Lu et al., 2018 | Investigated the function of the gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) in apoptosis induced by Mn by examining the Cx43 expression during excessive manganese exposure, excitotoxicity cell death mechanisms and glutamate homeostasis disruption due to manganese exposure. | Mechanastic- primary astrocytes | Primary astrocytes | Neurotoxicity, PD, AD | This research contributes to understanding how manganese exposure affects astrocyte communication and glutamate regulation, which could have implications for various neurological disorders associated with glutamate excitotoxicity. Manganese exposure significantly reduced astrocyte viability, increased apoptosis, disrupted glutamate homeostasis in astrocytes, elevated intracellular glutamate levels, Glutamate transporter expression was downregulated. |

| 9 | Kirkley et al., 2017 | Investigated the role of microglia and glial crosstalk in Mn-induced neurodegeneration. | Mechanastic-Mixed glial cultures from whole brain (astrocytes and microglia) | Cells | Neurotoxicity, AD, PD, Dementia | This study demonstrated that Mn is a potent inducer of an inflammatory phenotype in microglia that is essential for the activation of astrocytes, suggesting there are critical signaling pathways in glial cells for neuroinflammatory injury from Mn. It also revealed that the NF-κB signaling in microglia plays an essential role in inflammatory responses to Mn toxicity by regulating cytokines and chemokines that amplify the activation of astrocytes. |

| SL | References | Study objective | Study type | Exposure | Outcomes | Key Findings |

| 1 | Rogers et al., 2016 | Investigated the effect of Pb on iron homeostasis proteins in human neurons. Study the role of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in maintaining safe intracellular iron levels. | Mechanistic-human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells- In Vitro | Cells | neurotoxicity | Acute oxidative stress can result from the reduction of APP translation due to Pb exposure, which is associated to a rise in iron levels in neurons and glia without corresponding ferritin storage. Pb inhibits APP translation, raising cytosolic iron levels. Through the restoration of APP production, iron supplementation protects cells from Pb toxicity. The amyloid precursor protein (APP) is essential for preserving appropriate intracellular iron levels. Pb strengthens the inhibition of APP and FTH translation caused by IRP/IRE. Children with lead poisoning can benefit from iron administration as a treatment. |

| 2 | Wang et al., 2022 | Investigated how Pb affected microRNAs (miRNAs), post-transcriptional regulators that may be involved in the pathophysiology of AD. | Mechanistic-Mice-animal model | Mice-Drinking water | AD | Modulation of the miR-124-3p/BACE1 pathway plays a crucial role in Pb-induced AD-like amyloidogenic processing. BACE1 is upregulated in the PFC and hippocampal regions after exposure to Pb. miRNAs could be used as stand-in markers to diagnose illnesses. Pb exposure modifies miRNA expression, which impacts brain processes. |

| 3 | Bandaru et al., 2022 | Investigated the mitophagy marker proteins, including PINK1 and Parkin, in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells to examine the impact of Pd exposure on the PINK1/Parkin dependent pathway. | Mechanistic-SH-SY5Y cells | Cells | AD | Cells treated to Pb, both Aβ (25–35) and Aβ (1–40) separately and in various combinations showed a significant reduction in PINK1 and Parkin levels, which led to defective mitophagy. The Pb-exposed groups showed decreased mitochondrial mass, increased MPTP opening, depolarization of membrane potential, and increased generation of ROS within the mitochondria. By activating the Bak protein, which releases cytochrome c from mitochondria via MPTP and subsequently activates the cytosolic caspase-3 and AIF (apoptosis inducing factor) proteins, Pb may cause apoptosis. The results show that Pb-induced neurotoxicity may be caused by processes such as PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and defective mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. |

| 4 | Eid et al., 2016 | Investigated how early life exposure to lead (Pb) can cause epigenetic modifications and late-life changes. | Mechanistic-mice model | Mice-Drinking water | AD | The findings indicate a connection between Pb exposure throughout early life and its potential to reprogram the expression of epigenetic intermediates involved in histone modification or DNA methylation, which in turn control the expression of latent AD-related genes. The latent increases in AD-related proteins in the brain may be mediated by epigenetic modifiers, which are impacted by prenatal exposure to Pb. |

| 5 | Xie et al., 2023 | Investigated the effects of Pb exposure on AD-like pathogenesis in human cortical neurons. | Mechanistic-human iPSC-derived cortical neurons as a model system | human iPSC-derived cortical neurons | AD | The results offer support for the idea that developmental Pb exposure-induced Ca dysregulation is a likely molecular mechanism behind the elevated risk of AD in groups exposed to developmental Pb. Developmental Pb exposure is linked to persistent neuronal alterations and AD hallmarks (elevated tau aggregation and phosphorylation, Aβ42/40). Epigenetic modifications and DNA methylation changes were observed post-Pb exposure. A higher risk of neurological disorders is linked to long-term low-level Pb exposure. |

| 6 | vonderEmbse et al., 2017 | Investigated the association between early toxicant exposure and systematic microglia activation, possibly reversing the pathological severity of AD. | Mechanistic-mouse model | Mouse-Drinking water | AD | According to this research, early exposure to Pb may make people more vulnerable to neurodegeneration in later life, and activated microglia may provide neuroprotection against amyloid buildup early in AD pathogenesis. Females might be more vulnerable to AD as a result of early-life microglial injury. |

| 7 | Masoud et al., 2016 | Investigated the early postnatal exposure to Pb and alteration the expression of select miRNA (microRNA that TargetProteins Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease). | Mechanistic-mice model | Mouse-Mother's milk | AD | Exposure to the heavy metal Pb in early life has a significant impact on the short- and long-term expression of miRNAs that target epigenetic mediators and neurotoxic proteins. Pb exposure increases miR-106b, miR-29b, and miR-132 expression initially. miR-106b decreases over time, while miR-124 is reduced. Pb exposure triggers changes in miRNA expression targeting AD-related proteins. |

| 8 | Lee and Freeman, 2016 | Investigated the connection between latent neurological changes and embryonic Pb exposure utilizing the brains of adult male and female zebrafish. | Mechanistic-Zebrafish brain | Aquaria water | AD | Embryonic exposure to Pb at levels as low as 10 µg/L disrupts global gene expression patterns in a sex-specific manner that could lead to neurological alterations in later life. Embryonic Pb exposure in zebrafish leads to neurodegenerative gene expression changes. The Zebrafish model shows potential for studying neurodegenerative diseases. |

| 9 | Wu et al., 2020 | Investigated examined the possible mechanism by which Pb exposure exacerbates the development of Alzheimer's disease in mice by compromising the blood-brain barrier (BBB). | Mechanistic-mice model | Mice-Drinking water | AD | The potential mechanism by which early exposure to Pb causes the progression of AD has been examined in this study. The scientists found that Pb exposure can result in aberrant alterations in BBB junction proteins and hasten the deposition of Aβ1–42 in the brains of APP/PS1 mice. Additionally, it can raise p-tau expression in APP/PS1 and C57BL/6J mice. The equilibrium between Aβ generation and clearance is also disrupted by Pb exposure. The findings showed a connection between astrocytes and Aβ1–42 deposition in the brains of APP/PS1 mice. |

| 10 | Gu et al., 2020 | Investigated the potential effects of long-term Pb exposure on the blood-brain barrier system's permeability using the Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Computerized Tomography (DCE-CT) technique. | Mechanistic-mice model | Mice-oral gavage | AD | Data showed that Pb exposure increased the permeability surface area product, and significantly induced brain perfusion. However, Pb exposure did not alter extracellular volumes or fractional blood volumes in the mouse brain. The study suggests that Pb exposure at subtoxic and toxic levels directly targets the brain vasculature and damages the blood brain barrier system. |

| 11 | Bandaru et al., 2023 | Investigated the precise mechanism by which Pb causes Alzheimer's disease, specifically mitochondrial damage, using human neuronal cells. | Mechanistic-human neuronal cells (SH-SY5Y) | human neuronal cells | AD | The results demonstrated that exposure to Pb increased oxidative stress by increasing MDA levels, lowering GSH levels, and lowering the expression of genes for antioxidants such as SOD2 (MnSOD) and Gpx4. In addition, cells treated with Pb showed decreased mitochondrial mass, MMP, ATP levels, cytochrome c oxidase activity, and mtDNA copy number. Additionally, it showed that treated cells had reduced expression levels of the protein markers NDUFS3, SDHB, UQCRC2, COX4, and ATP5A, indicating compromised mitochondrial respiration and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction in Pb-induced AD. Thus, Pb toxicity may be a contributing factor to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in the development of Alzheimer's disease. |

| 12 | Lee and Freeman, 2020 | Investigated the relation between neurotoxic Pb exposure and de novo copy number alterations (CNAs) using Zebrafish fibroblast cells. | Mechanistic-Zebrafish cells | Cells | AD | The study found several genomic regions with CNAs brought on by in vitro Pb exposure, indicating that Pb exposure may act as an environmental chemical stressor that contributes to the development of de novo CNAs. There was a tendency for the number of CNAs to rise in proportion to Pb concentration. Amyloid precursor protein (APP), a crucial molecular target linked to the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease, is connected to nearly every gene in a molecular network. These data demonstrate that Pb exposure causes de novo CNAs, which may be a mechanism causing negative health effects linked to Pb toxicity, such as the pathophysiology of neurological diseases, and warrant more research. |

| 13 | Liu et al., 2023 | Investigated the effects of long-term lead exposure on the buildup of Aβ in cerebral capillaries and the expression of a vital Aβ transporter, low-density lipoprotein receptor protein-1 (LRP1), in brain parenchyma and capillaries in Sprague-Dawley rats. | Mechanistic- Rat model | Rat-oral gavage | AD | The cerebral vasculature naturally has a remarkably high affinity for the Aβ found in blood, as this study shows. Aβ buildup in the cerebral vasculature is significantly increased by Pb exposure, whether in vitro or in vivo. The reduced expression of an Aβ efflux carrier LRP1 in response to Pb in the studied brain region and fractions is partially responsible for this elevated Aβ accumulation. |

| 14 | Eid et al., 2018 | Investigated early life Pb exposure and latent over expression of AD-related genes regulation histone activation pathways. | Mechanistic-mice model | Drinking water | AD | A lifetime reprogramming of gene expression brought on by early life exposure to Pb produces a global repression profile that may be mediated by both DNA methylation and histone modification pathways. Such reprogramming does not seem to occur in genes linked to Alzheimer's disease, and different epigenetic processes may mediate their latent overexpression. |

| 15 | Bihaqi et al., 2014 | Investigated the expression of tau in the aged mice's brain cortex due to the infantile postnatal exposure to lead (Pb). | Mechanistic-mice model | Drinking water | AD | A rise in the levels of tau protein and tau mRNA is observed in aged mice that have been exposed to developmental Pb. An abnormal site-specific tau hyperphosphorylation along with increased levels of cyclin dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) was observed in aged mice that had previously been exposed to Pb. In addition, mice exposed to developmental Pb showed a changed p35/p25 protein ratio and increased serine/threonine phosphatase activity as old age. These modifications promoted an increase in tau phosphorylation, suggesting that environmental factors during development may play a role in neurodegenerative disorders. |

| 16 | Bihaqi et al., 2018 | Investigated how developmental Pb exposure affected the α-Syn pathways in a mouse model that was knocked out for the murine tau gene and in a human neuroblastoma SHSY5Y cell line that had undergone exposure to a wide range of Pb doses. | Mechanistic-Mice and SHSY5Y cells | Drinking water | AD | Mice with early-life Pb exposure exhibit latent upregulation of α-Syn. Moreover, prior in vitro exposure to Pb increased the levels of Caspase-3, glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), and α-Syn and its phosphorylated forms. The latent effects of Pb exposure are mediated by epigenetic mechanisms. |

| 17 | Huang et al., 2024 | Investigated the mechanism by which Pb exposure aggravates AD progression and the role of microglial activation, APP/PS1 mice and Aβ1-42-treated BV-2 cells were exposed to Pb. | Mechanistic-mice model and BV-2 microglial cells | Drinking water | AD | The results of the study showed that long-term exposure to Pb can exacerbate memory and learning deficits in APP/PS1 mice. One possible explanation for the mechanism is that increased expression of the mitochondrial protein CHCHD4/AIF in microglia, which causes mitochondrial copper overload through COX17-mediated translocation. This results in mitochondrial dysfunction and excessive mtROS accumulation, which in turn activates microglia. |

| 18 | Zhou et al., 2018 | Investigated the role of cholesterol metabolism in lead induced premature AD-like pathology in rats. | Mechanistic-male Sprague-Dawley rats | Drinking water | AD | The findings showed that Pb exposure disrupted the metabolism of cholesterol in the brain, which led to early AD-like pathology in young, growing rats. Exposure to Pb disrupted the balance of cholesterol, reduced brain cholesterol, triggered the SREBP2-BACE1 pathway, reduced the expression of HMG-CR and LDL-R, and increased the expression of ABCA1 and LXR-α. |

| 19 | Ayyalasomayajula et al., 2019 | Investigated the role of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) in reducing oxidative stress and apoptosis in human neural cells caused by Pb and β-APs, both alone and in combination. | Mechanistic-SH-SY5Y cells | Cells | AD | EGCG reduced oxidative stress caused by Pb and β-AP by scavenging reactive oxygen species, inhibiting annexin V and caspase-3, and lowering apoptosis through increased expression levels of Bax and Bcl2. EGCG mitigates oxidative stress and apoptosis to shield SH-SY5Y cells from the cytotoxicity caused by Pb and β-APs. |

| 20 | Lee et al., 2017 | Investigated the impact of embryonic Pb exposure on AD genetic risk factors by analyzing sex-specific alterations in sorl1 expression in adult zebrafish. | Mechanistic- zebrafish | Aquaria water | AD | This study characterized sorl1 with changes in brain expression during aging being female-specific. No significant differences in sorl1 expression were observed with embryonic lead exposure. A zebrafish model was used to study AD genetic risk factors and sorl1. nSorl1 expression in the zebrafish brain was not influenced by age. The zebrafish model shows potential for AD research, with sorl1 characterization. |

| 21 | Lokesh et al., 2024 | Investigated how Pb and amyloid β peptides (1–40 and 25–35) interact with cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5) and its activator, p25, to determine the molecular basis of Pb-induced neurotoxicity in neuronal cells and their possible neurodegenerative significance. | Mechanistic-Human SH-SY5Y cells | Cells | AD | The findings showed that Pb exposure caused changes in intracellular calcium and increased Pb absorption. Additionally, a significant decrease in overall antioxidant capacity and an increase in protein carbonylation, a hallmark of oxidative damage, were shown in the results, indicating a compromised ability of cells to fend off oxidative stress and increased oxidative damage to DNA. The role of Pb-induced CDK5-p25 signaling in AD pathogenesis was further supported by the observation of dysregulations in levels of calpain, p25-35, and CDK5, as well as markers linked to antioxidant metabolism (phospho-Peroxiredoxin 1), DNA damage responses (phospho-ATM and phospho-p53), and nuclear membrane disruption (phospho-lamin A/C). The complex molecular processes behind Pb-induced neurotoxicity are clarified by these findings, which also offer important new information about the mechanisms underpinning the development of AD. |

| SL | References | Study objective | Study type | Exposure | Outcomes | Key Findings |

| 1 | Liu, et al., 2023 | Investigated the underlying mechanism and impact of low-dose environmental cadmium (Cd) exposure on the development of Alzheimer's disease. | Mechanistic-Mice-animal model | Mice-Drinking water | AD | At higher doses, Cd increased the amount of fluorescent dye that leaked and induced several degenerative morphological abnormalities in the mouse brains. The damage to the APP/PS1 mice was more severe than that of the C57BL/6J mice. Cd exposure cause a rise in anxiety-like behavior and disorderly movement, disruption to spatial reference memory, Aβ plaque formation in mice brains, an increase in microglia expression in the brain, and elevated levels of IL-6 in the cortex and serum. |

| 2 | Zhang et al., 2021 | Investigated cadmium (Cd) interactions with ApoE4 gene variants to modify the gut-liver axis in mouse. | Mechanistic-Mouse model | Mice-Drinking water | AD | In ApoE4-KI males (the most vulnerable mouse strain to neurological damage), Cd exposure significantly altered the gut-liver axis. This was demonstrated by an increase in microbial AD biomarkers, a decrease in gut and blood pathways related to energy supply, and an increase in hepatic pathways involved in inflammation and xenobiotic biotransformation. Male ApoE4-KIs exhibited the most noticeable alterations in their gut microbiota, along with a predicted down-regulation of numerous vital microbial processes related to energy and nutrition homeostasis. |

| 3 | Wang et al., 2022 | Investigated the effects of Cd-ApoE on the transcriptome alterations in the livers and brains of ApoE3/ApoE4 transgenic mice. | Mechanistic-mice model | Mice-Drinking water | AD | One possible explanation for the variation in the sensitivity to Cd neurotoxicity is that Cd dysregulated the brain and liver drug-processing genes in a way that was specific to sex and ApoE genotype. The livers of ApoE4 males exposed to Cd had more pro-inflammatory genes, and the brains of ApoE3 mice had more Cyp2j isoforms. Male-specific brain dysregulation of cation transporters was observed. |

| 4 | Notarachilleet al., 2014 | Investigated the effects of varying concentrations of Cd on the secondary structure of AbP1–42 in an aqueous environment as well as on the AbP1–42 ion channel integrated in a planar lipid membrane composed of phosphatidylcholine with 30% cholesterol. | Mechanistic-Experimental | - | AD | Results reinforce and broaden the growing idea that AD and environmental pollutants like Cd are related. By acting on both the channel integrated into the membrane and the peptide in solution, Cd can interact with the AbP1–42 peptide, reducing AbP1–42 channel activity and turnover until the channel activity completely vanishes and forming large amorphous aggregates in solution that are prone to precipitation. The production and neurotoxicity of AbP fibrils or oligomers may be significantly influenced by Cd. |

| 5 | Matsushita et al., 2023 | Investigated the possibility of functionally rescuing ApoE4-KI mice's Cd-induced cognitive impairment through genetic and conditional activation of adult neurogenesis. | Mechanistic-mice model | Drinking water | AD | The study showed a clear correlation between memory impairment and adult neurogenesis in a GxE model of ApoE4 by finding that Cd-induced impairments in hippocampus-dependent short-term spatial memory were restored by selective and conditional stimulation of adult neurogenesis. The results offer compelling proof of a GxE effect and a plausible underlying mechanism involving adult neurogenesis at levels of Cd exposure that are applicable to the US population. |

| 6 | Del Pino et al., 2016 | Investigated the mechanisms of cell death induced by cadmium (Cd) on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. | Mechanistic-SN56 Cell lines | SN56 cholinergic mourine septal cell line | AD | By blocking the M1 receptor, overexpressing AChE-S and GSK-3β, downregulating AChE-R, and raising the levels of Aβ, total, and phosphorylated tau proteins, Cd causes cell death in cholinergic neurons. The findings of this study offer new insight into the processes behind the detrimental effects of Cd on cholinergic neurons and imply that Cd may mediate these processes by blocking M1R through altered expression of AChE splices. |

| 7 | Deng et al., 2024 | Investigated examined the underlying mechanism and impact of autophagy on the development of AD caused by environmental Cd. | Mechanistic-Mouse neuroblastoma cells (Neuro-2a cells) | Cells | AD | RAB7A desuccinylation, which is catalyzed by SIRT5, is a crucial adaptive mechanism that helps address AD-like pathology and Cd-induced autophagic flux blockage. SIRT5 made RAB7A more active by desuccinylating it at the Lys31 residue. RAB7A activation acted as a buffer against autophagic flux blockage, hence reducing the worsening of AD-like pathologies and cognitive impairment caused by Cd. |

| 8 | Arab et al., 2023 | Investigated the potential of topiramate to combat the cognitive deficits induced by cadmium in rats with an emphasis on hippocampal oxidative insult, apoptosis, and autophagy. | Mechanistic-Rats model | oral gavage | AD-Cognitive Deficits | The effectiveness of topiramate in improving behavioral outcomes, such as memory/learning impairments and histopathological abnormalities, as well as certain molecular processes related to hippocampus disruptions of redox milieu, apoptosis, and autophagy, were the primary focus of this investigation. Hippocampal GLP-1 was markedly restored by topiramate, which also attenuated p-tau and A42. Notably, it increased GABA and cholinergic neurotransmitters and markedly decreased glutamate concentration in the hippocampus. The SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 axis was significantly activated, and the hippocampus suppressed the pro-oxidant processes, which led to the behavioral recovery. Additionally, topiramate suppressed the apoptotic alterations in the hippocampus and deactivated GSK-3. Within Topiramate’s pro-autophagic, antioxidant, and anti-apoptotic characteristics helped explain its neuroprotective effects in Cd-intoxicated rats. As a result, it might help lessen cognitive impairments brought on by Cd. |

| 9 | Zhang et al., 2020 | Investigated the gene-environment interactions (GxE) between ApoE-e4 and Cd exposure on cognition, a mouse model of AD was used that expresses human ApoE-e3 (ApoE3-KI [knock-in]) or ApoE-e4 (ApoE4-KI). | Mecahnistic-Mouse model | Mouse-Drinking water | AD | A GxE between ApoE4 and Cd exposure causes accelerated cognitive deterioration, and one of the possible underlying mechanisms is reduced adult hippocampus neurogenesis. Additionally, during the early stages of the animals' lives, male mice were more vulnerable to this GxE impact than female mice. |

| 10 | Qian et al., 2024 | Investigated the involvement of cellular senescence in AD, the effects of one of the potential environmental risk factors for AD, cadmium chloride (CdCl2) exposure was explored on neuron senescence in vivo and in vitro. | Mechanistic-Mice and SHSY5Y cells | Mice-Drinking water | AD | Cd promoted neural senescence via cascade activating the p53/p21/Rb pathway. SigmaR1 depletion contributed to neural senescence through Ca2+ dyshomeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cd activated SEL1L/HRD1-mediated ERAD to degrade SigmaR1 via ubiquitination at its K142 site. SEL1L/HRD1-regulated SigmaR1 degradation and p53/p21/Rb pathway was activated in AD. SigmaR1 agonist ANAVEX2-73 attenuated Cd-induced AD-like phenotype via the restrain of neural senescence. A new senescence-associated regulatory pathway for the SEL1L/HRD1/SigmaR1 axis that influences the pathological development of AD linked to CdCl2 exposure was identified in this study. Pharmacological stimulation of SigmaR1 may be a viable intervention technique for AD therapy, and it may serve as a neuroprotective biomarker of neuronal senescence. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).