Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Object of the Study

2.2. Nutrient Media and Seeding

2.3. Mass Spectrometric Analysis

2.4. PCR Analysis of Escherichia coli

2.5. CDT Typing

2.6. Serotyping of Escherichia coli

2.7. Biochemical Identification and Susceptibility to Antimicrobials

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of E. albertii and Other Microorganisms

3.2. Identification of E. albertii

3.3. Results of PCR Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oaks, J.L.; Besser, T.E.; Walk, S.T.; Gordon, D.M.; Beckmen, K.B.; Burek, K.A. Escherichia albertii in wild and domestic birds. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010, 16, 638–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.J.; Alam, K.; Islam, M.; Montanaro, J.; Rahaman, A.S.; Haider, K. Hafnia alvei, a probable cause of diarrhea in humans. Infect Immun. 1991, 59, 1507–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, K.; Ooka, T.; Akita, H.; Hiratsuka, T.; Takao, S.; Fukada, M. Epidemiological Aspects of Escherichia albertii Outbreaks in Japan and Genetic Characteristics of the Causative Pathogen. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2020, 17, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuoka, E.; Furukawa, K.; Nagamura, T.; Harada, F.; Ekinaga, K.; Tokunaga, H. Food poisoning outbreak due to atypical EPEC OUT:HNM, May 2011-Kumamoto. Infect. Agents Surveill. Rep. 2012, 33, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, K.; Maeda-Mitani, E.; Kimura, H.; Honda, M.; Ikeda, T.; Sugitani, W. Non-biogroup 1 or 2 Strains of the Emerging Zoonotic Pathogen Escherichia albertii, Their Proposed Assignment to Biogroup 3, and Their Commonly Detected Characteristics. Front Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchaamba, F.; Barmettler, K.; Treier, A.; Houf, K.; Stephan, R. Microbiology and Epidemiology of Escherichia albertii-An Emerging Elusive Foodborne Pathogen. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Knirel, Y.A.; Feng, L.; Perepelov, A.V.; Senchenkova, S.N.; Reeves, P.R. Structural diversity in Salmonella O antigens and its genetic basis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014, 38, 56–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Bai, X.; Yang, X.; Fan, G.; Wu, K.; Song, W. Identification and Genomic Characterization of Escherichia albertii in Migratory Birds from Poyang Lake, China. Pathogens. 2022, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Cao, L.; Zeng, X.; Gillespie, B.; Lin, J. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia albertii originated from the broiler farms in Mississippi and Alabama. Vet Microbiol. 2022, 267, 109379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmettler, K.; Biggel, M.; Treier, A.; Muchaamba, F.; Vogler, B.R.; Stephan, R. Occurrence and Characteristics of Escherichia albertii in Wild Birds and Poultry Flocks in Switzerland. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alispahic, M.; Hummel, K.; Jandreski-Cvetkovic, D.; Nöbauer, K.; Razzazi-Fazeli, E.; Hess, M. Species-specific identification and differentiation of Arcobacter, Helicobacter and Campylobacter by full-spectral matrix-associated laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry analysis. J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujioka, M.; Yoshioka, S.; Ito, M.; Ahsan, C.R. Characterization of the Emerging Enteropathogen Escherichia Albertii Isolated from Urine Samples of Patients Attending Sapporo Area Hospitals, Japan. Int J Microbiol. 2022, 6, 4236054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-RL VTEC_Method_02_Rev 0, EU Reference Laboratory VTEC, Rome, Italy.

- Dubois, D.; Delmas, J.; Cady, A.; Robin, F.; Sivignon, A.; Oswald, E. Cyclomodulins in urosepsis strains of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2010, 48, 2122–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, W.A.; Bragg, R.R. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction for screening avian pathogenic Escherichia coli for virulence genes. Avian Pathol. 2012, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.J.; Wannemuehler, Y.; Doetkott, C.; Johnson, S.J.; Rosenberger, S.C.; Nolan, L.K. Identification of minimal predictors of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli virulence for use as a rapid diagnostic tool. J Clin Microbiol. 2008, 46, 3987–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telhig, S.; Ben Said, L.; Zirah, S.; Fliss, I.; Rebuffat, S. Bacteriocins to Thwart Bacterial Resistance in Gram Negative Bacteria. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11, 586433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rood, J.I.; Adams, V.; Lacey, J.; Lyras, D.; McClane, B.A.; Melville, S.B. Expansion of the Clostridium perfringens toxin-based typing scheme. Anaerobe. 2018, 53, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallapura, G.; Morgan, M.J.; Pumford, N.R.; Bielke, L.R.; Wolfenden, A.D.; Faulkner, O.B. Evaluation of the respiratory route as a viable portal of entry for Salmonella in poultry via intratracheal challenge of Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium. Poult Sci. 2014, 93, 340–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camba, S.I.; Del Valle, F.P.; Shirota, K.; Sasai, K.; Katoh, H. Evaluation of 3-week-old layer chicks intratracheally challenged with Salmonella isolates from serogroup c1 (O:6,7) and Salmonella Enteritidis. Avian Pathol. 2020, 49, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.E.; Murray, L.; Fanning, S.; Cormican, M.; Daly, M.; Delappe, N. Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Salmonella bredeney associated with a poultry-related outbreak of gastroenteritis in Northern Ireland. J Infect. 2003, 47, 33–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymurazov, M.G.; Platonov, M.E.; Tazina, O.I.; Manin, T.B. The biological properties of the strains Avibacterium paragallinarum and Gallybacterium anatis isolated in the Russian Federation in 2015. Veterinary, 6.

- Manin, TB.; Маximov, Т.P.; Teimurazov, M.G.; Platonov, М.Е. The new data of spread of infectious coryza in Russia and some CIS countries in 2013 – 2015 years. Veterinary, 4.

- Persson, G.; Bojesen, A.M. Bacterial determinants of importance in the virulence of Gallibacterium anatis in poultry. Vet Res. 2015, 46, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Jiang, H.; Qi, Z.; Shen, X.; Xue, M.; Hu, J. APEC infection affects cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and cell cycle pathways in chicken trachea. Res Vet Sci. 2020, 130, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oaks, J.L.; Besser, T.E.; Walk, S.T.; Gordon, D.M.; Beckmen, K.B.; Burek, K.A. Escherichia albertii in wild and domestic birds. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010, 16, 638–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Ragione, R.M.; McLaren, I.M.; Foster, G.; Cooley, W.A.; Woodward, M.J. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of avian Escherichia coli O86:K61 isolates possessing a gamma-like intimin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4932–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadis, G.; Destoumieux-Garzón, D.; Lombard, C.; Rebuffat, S.; Peduzzi, J. Isolation and characterization of two members of the siderophore-microcin family, microcins M and H47. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 288–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Milne, J.C.; Madison, L.L.; Kolter, R.; Walsh, C.T. From peptide precursors to oxazole and thiazole-containing peptide antibiotics: microcin B17 synthase. Science. 1996, 274, 1188–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The mdh, lysP and clpX genes are specific to E. albertii | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Primer | 5’-3’ | Annealing, °C | Product size (bp) | Reference |

|

Mdh malatedehydrogenase |

mdh-F | CTGGAAGGCGCAGATGTGGTACTGATT | 55 | 115 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| mdh-R | CTTGCTGAACCAGATTCTTCACAATACCG | ||||

|

Lys Lysine-specific transporter |

lysP-F | GGGCGCTGCTTTCATATATTCTT | 55 | 252 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| lysP-R | TCCAGATCCAACCGGGAGTATCAGGA | ||||

|

Clp Heat shock protein |

clpX-F | TGGCGTCGAGTTGGGCA | 55 | 384 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| clpX-R | TCCTGCTGCGGATGTTTACG | ||||

| Pre-denaturation 95°C – 5 min; 25 cycles: denaturation 95°C – 1 min, annealing 55°C – 1 min, elongation 72°C – 1 min-. Final elongation 72°C – 3 min. | |||||

| E. coli APEC virulence genes | |||||

|

cva colicin V plasmid |

cvaF | CACACACAAACGGGAGCTGTT | 63 | 672 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| cvaR | CTTCCGCAGCATAGTTCCAT | ||||

|

omp episomal outer membrane protease |

ompF | TCATCCCGGAAGCCTCCCTCACTACTAT | 63 | 496 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| ompR | TAGCGTTTGCTGCACTGGCTTCTGATAC | ||||

|

iroN salmochelinsiderophore receptor |

ironF | AAGTCAAAGCAGGGGTTGCCCG | 63 | 667 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| ironR | GATCGCCGACATTAAGACGCAG | ||||

|

fim fimbriae |

fimF | GGATAAGCCGTGGCCGGTGG | 63 | 331 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| fimR | CTGCGGTTGTGCCGGAGAGG | ||||

|

iut Aerobactinsiderophore receptor |

iutF | GGCTGGACATCATGGGAACTGG | 63 | 302 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| iutR | CGTCGGGAACGGGTAGAATCG | ||||

|

iss Episomal gene for increased survival in serum |

issF | CAGCAACCCGAACCACTTGATG | 63 | 323 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| issR | AGCATTGCCAGAGCGGCAGAA | ||||

|

hly hemolysin |

hlyF | GGCCACAGTCGTTTAGGGTGCTTACC | 63 | 450 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| hlyR | GGCGGTTTAGGCATTCCGATACTCAG | ||||

|

eae intimin |

eaeF | CATTGATCAGGATTTTTCTGGTGATA | 63 | 102 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| eaeR | CTCATGCGGAAATAGCCGTTA | ||||

| Pre-denaturation 95°C – 5 min; 35 cycles: denaturation 95°C – 30 sec, annealing 63°C – 45 sec, elongation 72°C – 1 min 45 sec. Final elongation 72°C – 5 min. | |||||

| E. colimicrocin genes | |||||

| Microcin B17 | mcc B17-F | TCACGCCAGTCTCCATTAGGTGTTGGCATT | 60 | 135 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| mcc B17-R | TTCCGCCGCTGCCACCGTTTCCACCACTAC | ||||

| Microcin C7 | mcc C7-F | CGTTCAACTGTTGCAATGCT | 60 | 134 | |

| mcc C7-R | AGTTGAGGGGCGTGTAATTG | ||||

| Microcin E492 | mcc E492-F | GTCTCTCCTGCACCAAAAGC | 60 | 291 | |

| mcc E492-R | TTTTCAGTCATGGCGTTCTG | ||||

| Microcin H47 | mcc H47-F | CACTTTCATCCCTTCGGATTG | 60 | 227 | |

| mcc H47-R | AGCTGAAGTCGCTGGCGCACCTCC | ||||

| Microcin J25 | mcc J25-F | TCAGCCATAGAAAGATATAGGTGTACCAAT | 60 | 175 | |

| mcc J25-R | TGATTAAGCATTTTCATTTTAATAAAGTGT | ||||

| Microcin L | mcc L-F | GGTAAATGATATATGAGAGAAATAACGTTA | 60 | 233 | |

| mcc L-R | TTTCGCTGAGTTGGAATTTCCTGCTGCATC | ||||

| Microcin V | mcc V-F | CACACACAAAACGGGAGCTGTT | 60 | 680 | |

| mcc V-R | TTTCGCTGAGTTGGAATTTCCTGCTGCATC | ||||

| Microcin M | micM-4-F | CGTTTATTAGCCCGGGATTT | 60 | 166 | |

| micM-4-R | GCAGACGAAGAGGCACTTG | ||||

| Pre-denaturation 95°C – 5 min; 35 cycles: denaturation 95°C – 30 sec, annealing 60°C – 30 sec, elongation 72°C – 30 sec. Final elongation 72°C – 5 min. | |||||

| Primers encoding different types of cdt genes and cif gene in E. coli | |||||

| cdtB-II, cdtB-III, cdtB-V | CDT-s1 | GAAAGTAAATGGAATATAAATGTCCG | 60 | 467 | [Ошибка! Истoчник ссылки не найден.] |

| CDT-as1 | AAATCACCAAGAATCATCCAGTTA | ||||

| cdtB-II* | CDT-IIas | TTTGTGTTGCCGCCGCTGGTGAAA | 62 | 556 | |

| cdtB-III, cdtB-V* | CDT-IIIas | TTTGTGTCGGTGCAGCAGGGAAAA | 62 | 555 | |

| cdtB-I, cdtB-IV | CDT-s2 | GAAAATAAATGGAACACACATGTCCG | 56 | 467 | |

| CDT-as2 | AAATCTCCTGCAATCATCCAGTTA | ||||

| cdtB-I | CDT-Is | CAATAGTCGCCCACAGGA | 56 | 411 | |

| CDT-Ias | ATAATCAAGAACACCACCAC | ||||

| cdtB-IV | CDT-IVs | CCTGATGGTTCAGGAGGCTGGTTC | 56 | 350 | |

| CDT-IVas | TTGCTCCAGAATCTATACCT | ||||

| cdtC-V | P105 | GTCAACGAACATTAGATTAT | 49 | 748 | |

| c2767r | ATGGTCATGCTTTGTTATAT | ||||

| cif | cif-int-s | AACAGATGGCAACAGACTGG | 55 | 383 | |

| cif-int-as | AGTCAATGCTTTATGCGTCAT | ||||

| Pre-denaturation 95°C – 5 min; 35 cycles: denaturation 95°C – 30 sec, annealing – 30 sec, elongation 72°C – 30 sec. Final elongation 72°C – 5 min. | |||||

| No. of sample, workshop, age | Parenchymatous organs (liver, lungs, heart, spleen) | The contents of the sinuses, trachea | Intestines | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 line, 21d | 1 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Salmonella bredeney, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Bordetella hinzii | Clostridium perfringens |

| 2 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Salmonella bredeney, Bordetella hinzii | Clostridium perfringens | |

| 3 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Salmonella bredeney | Clostridium perfringens | |

| 4 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Salmonella bredeney, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Bordetella hinzii | ||

| 5 | Salmonella bredeney, Bordetella hinzii | |||

| 2 line, 21d | 1 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Salmonella bredeney, Streptococcus pluranimalium | |

| 2 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Gallibacterium anatis, Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Clostridium perfringens | |

| 3 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Streptococcus pluranimalium | ||

| 4 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Gallibacterium anatis, Staphylococcus piscifermentans | ||

| 5 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Gallibacterium anatis, Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Clostridium perfringens | |

| 3 line, 18d | 1 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Gallibacterium anatis, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Bordetella hinzii | |

| 2 | Salmonella bredeney, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Bordetella hinzii | |||

| 3 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Salmonella bredeney, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Bordetella hinzii, Gallibacterium anatis | ||

| 4 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Streptococcus pluranimalium, Bordetella hinzii | ||

| 5 | Gallibacterium anatis, Salmonella bredeney | |||

| 4 line, 18 d | 1 | Gallibacterium anatis, Streptococcus pluranimalium, E.coli | ||

| 2 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Gallibacterium anatis, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Staphylococcus piscifermentans | ||

| 3 | Gallibacterium anatis | |||

| 4 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Gallibacterium anatis, Streptococcus pluranimalium, Staphylococcus piscifermentans | ||

| 5 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | Escherichia albertii | |

| m/f, 18 d | 1 | Salmonella bredeney | Escherichia albertii, Clostridium perfringens | |

| 2 | Staphylococcus piscifermentans | E.coli | ||

| 3 | E.coli | Escherichia albertii | ||

| 4 | Salmonella bredeney | Escherichia albertii | ||

| 5 | Salmonella bredeney | Escherichia albertii | ||

| Antibiotics by Vitek2 | E. albertii group 1 with the eae gene (in parentheses MPC mg/l) | E. albertii group 2 without eae gene |

|---|---|---|

| BLRS | - | - |

| Ampicillin | S (8) | R (16) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulonic acid | S (8) | R (16) |

| Cefotaxime | S (≤ 0,25) | S (≤ 0,25) |

| Ceftazidime | S (≤ 0,12) | S (≤ 0,12) |

| Cefipime | S (≤ 0,12) | S (≤ 0,12) |

| Eatapenem | S (≤ 0,12) | S (≤ 0,12) |

| Meropenem | S (≤ 0,25) | S (≤ 0,25) |

| Amikacin | S (≤ 2) | S (≤ 2) |

| Gentamicin | S (≤ 1) | S (≤ 1) |

| Netilmicin | ND (≤ 1) | ND (≤ 1) |

| Ciprofloxacin | R (1) | R (1) |

| Tigecycline | S (≤ 0,5) | S (≤ 0,5) |

| Fosfomycin | ≤ 16 | ≤ 16 |

| Nitrofurantoin | S (≤ 16) | S (≤ 16) |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | S (≤ 20) | S (≤ 20) |

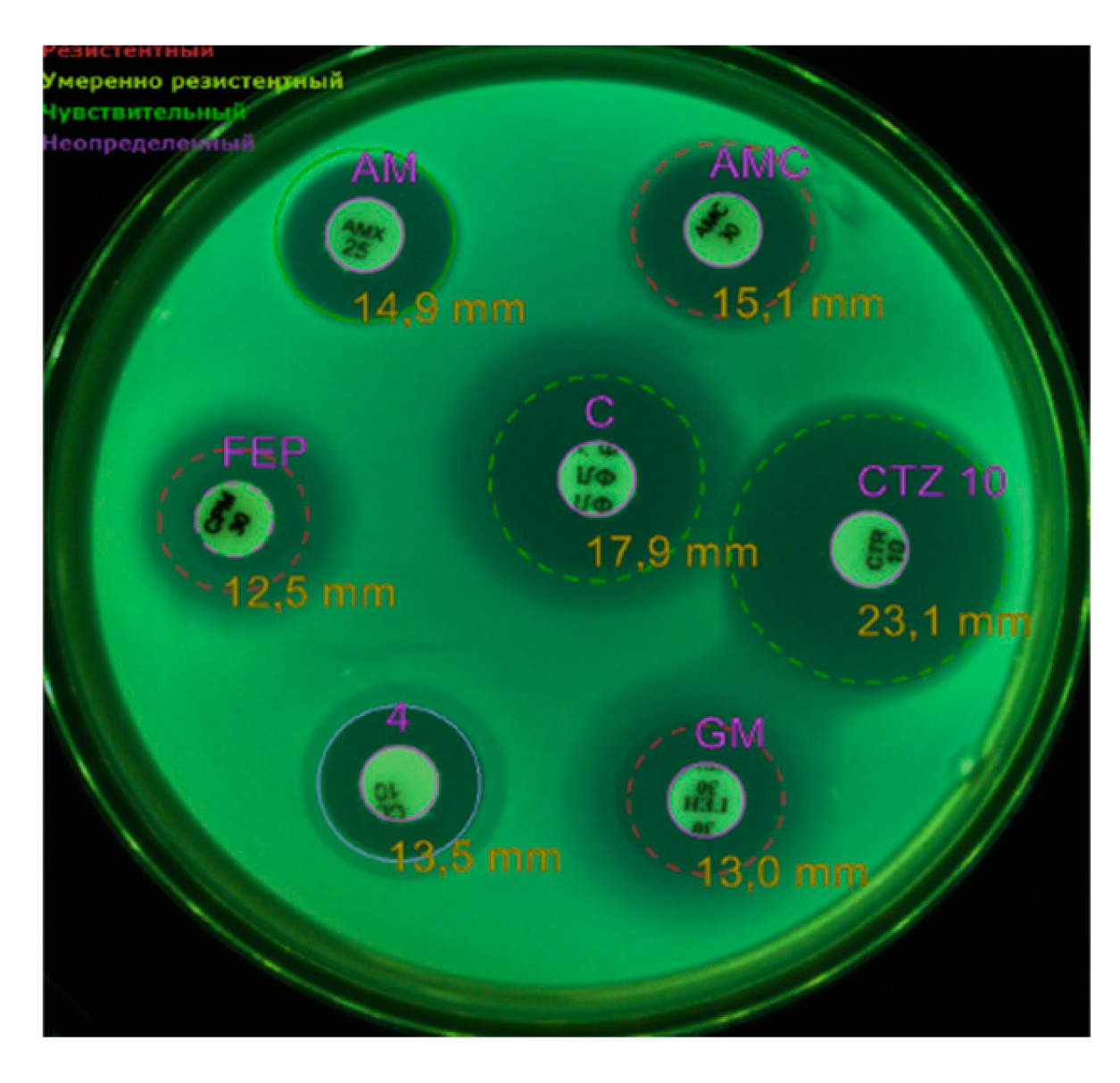

| Antibiotics using the disk-diffusion method | ||

| Amoxicillin/clavulonic acid, 30 | S | R |

| Ampicillin, 25 | S | R |

| Ceftazidime, 10 | S | S |

| Gentamicin, 10 | R | R |

| Colistin, 10. | R | R |

| Cefepime, 30. | R | R |

| Chloramphenicol, 30 | S | S |

| Imipenem, 10 | S | S |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | S | S |

| Amikacin, 30 | R | R |

| Fosfomycin, 50 | R | R |

| Norfloxacin, | R | R |

| Tigecycline | R | R |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).