Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Unlocking more aspects of human cognitive structuring, human-AI, and human-robot interaction requires increasingly advanced communication skills on both the human and robot sides. This paper compares three methods of retrieving cultural heritage information in primary school education: search engines, large language models (LLMs), and the NAO humanoid robot, which serves as a facilitator with programmed answering capabilities for convergent questions. Human-robot interaction has become a critical aspect of modern education, with robots like the NAO providing new opportunities for engaging and personalized learning experiences. The NAO, with its anthropomorphic design and ability to interact with students, presents a unique approach to fostering deeper connections with educational content, particularly in the context of cultural heritage. The paper includes an introduction, an extensive literature review, methodology, research results from student questionnaires, and conclusions. The findings highlight the potential of intelligent and embodied technologies in enhancing knowledge retrieval and engagement, demonstrating the NAO’s ability to adapt to student needs and facilitate more dynamic learning interactions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

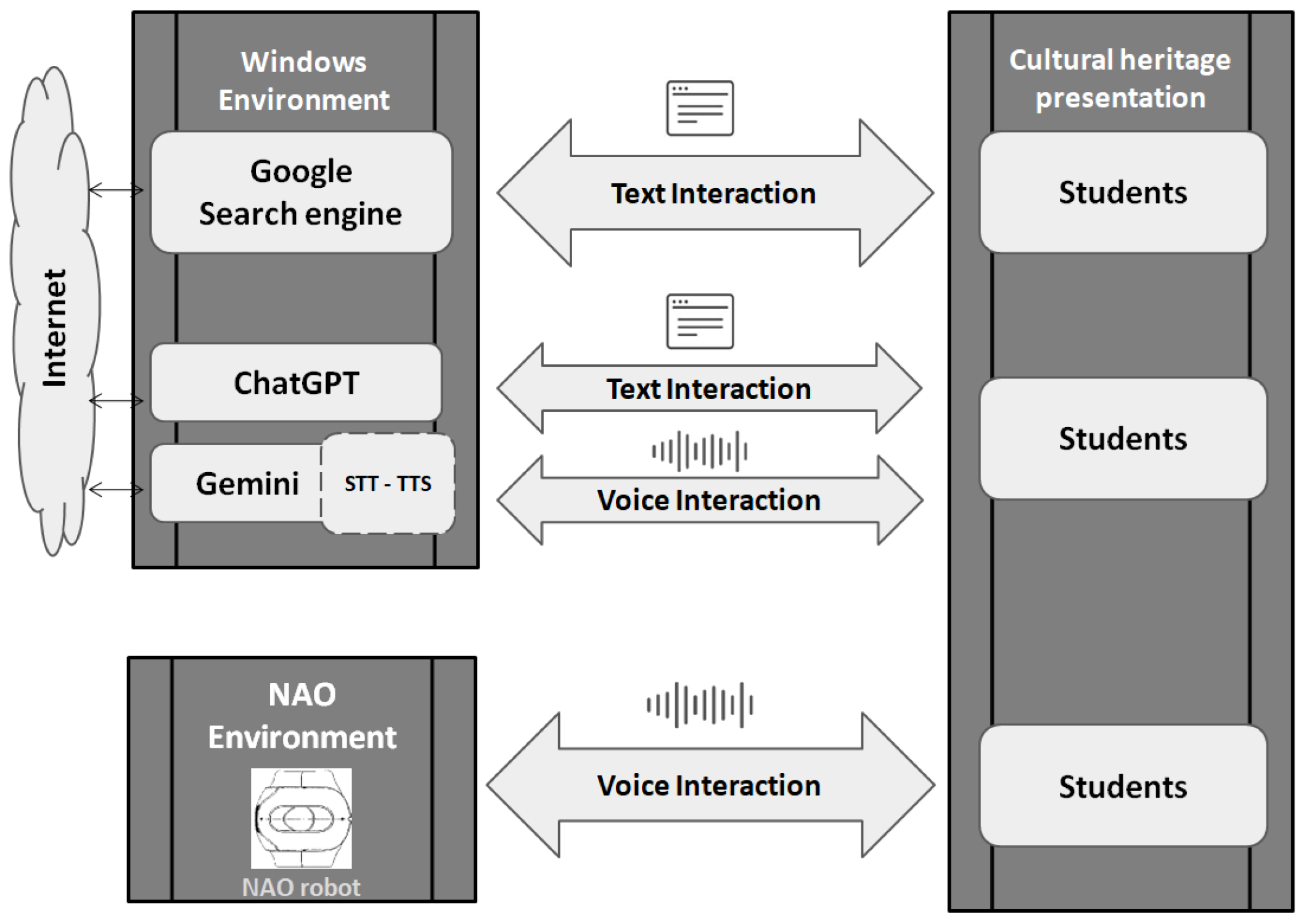

3. Methodology

- Comparative Evaluation of Methods for Retrieving Cultural Heritage Information

- General Comparison of Information Retrieval Methods

- NAO-Specific Interaction

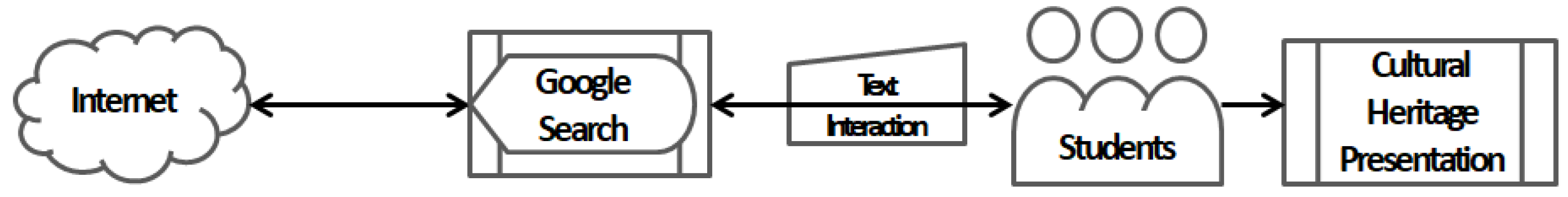

3.1. Phase 1: Search Engines

- Introduction to Search Engines: Students were introduced to the basics of using Google effectively, including tips on formulating search queries and evaluating the reliability of sources.

- Hands-on Research Activity: Students conducted searches on specific topics related to Greek cultural heritage, collecting information to support their presentations.

- Group Discussion: A collaborative discussion followed, during which students analyzed the effectiveness of search engines in gathering relevant and reliable information.

- Did you find the information you were looking for easily?

- Did you have trouble finding information on cultural heritage?

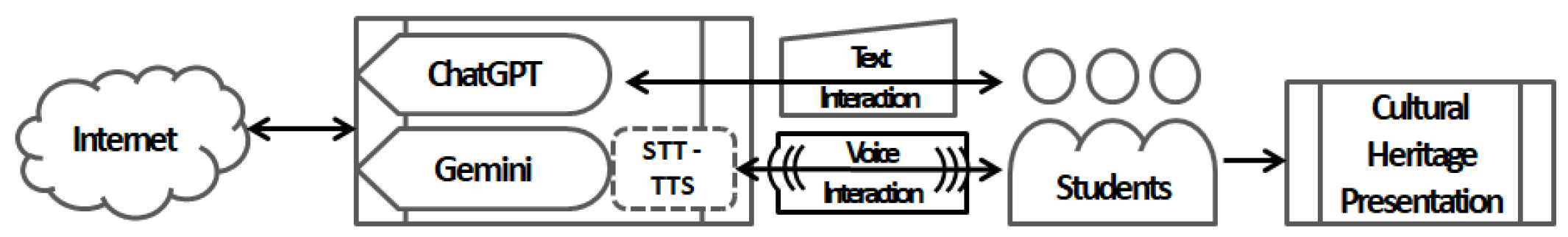

3.2. Phase 2: Large Language Models (LLMs)

- Introduction to LLMs: Students received an overview of LLMs, their capabilities, and their potential applications in learning.

- Interactive Q&A Session: Students engaged with Gemini using voice commands in Greek and with ChatGPT for written queries. They compared the responses from both models, focusing on clarity, depth, and relevance.

- Cross-Referencing Results: Students analyzed the information gathered from LLMs and compared it to the data they had collected during the first phase.

- Did each technology have knowledge of cultural heritage?

- Did you think you could use this technology without the help of the teacher?

3.3. Phase 3: NAO Robot

- Introduction to NAO: Students were introduced to the features of the NAO robot and its potential as a learning assistant.

- Interactive Session with NAO: Students posed questions to the robot about Greek culture, observing its responses and engaging in a dialogue.

- Reflection and Feedback: Students shared their experiences working with the NAO robot, reflecting on how it compared to the previous methods.

- Were you satisfied with the NAO’s answers?

- Were there times when the NAO did not listen to what you were saying?

- Would you like the NAO to be smarter?

3.4. Comparative Analysis and Insights

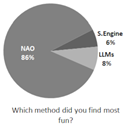

- Which method did you find most fun?

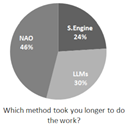

- Which method took you the longest to do the work?

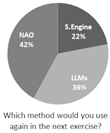

- Which method would you use again in the next exercise?

- Which method do you think should be improved?

3.5. Objectives and Outcomes

- Individual Performance Evaluation: To assess the performance of each method—Google’s search engine, Large Language Models, and the NAO robot—in providing accurate and relevant information.

- Comparative Analysis: To compare the three methods in terms of reliability, speed, and accuracy of responses, as well as their usability and engagement levels.

- Focus on Embodied Interaction: To evaluate the students’ experiences with the NAO robot, highlighting its potential as an innovative educational tool.

4. Analysis of Questionnaire Data

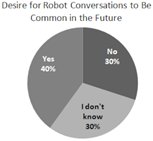

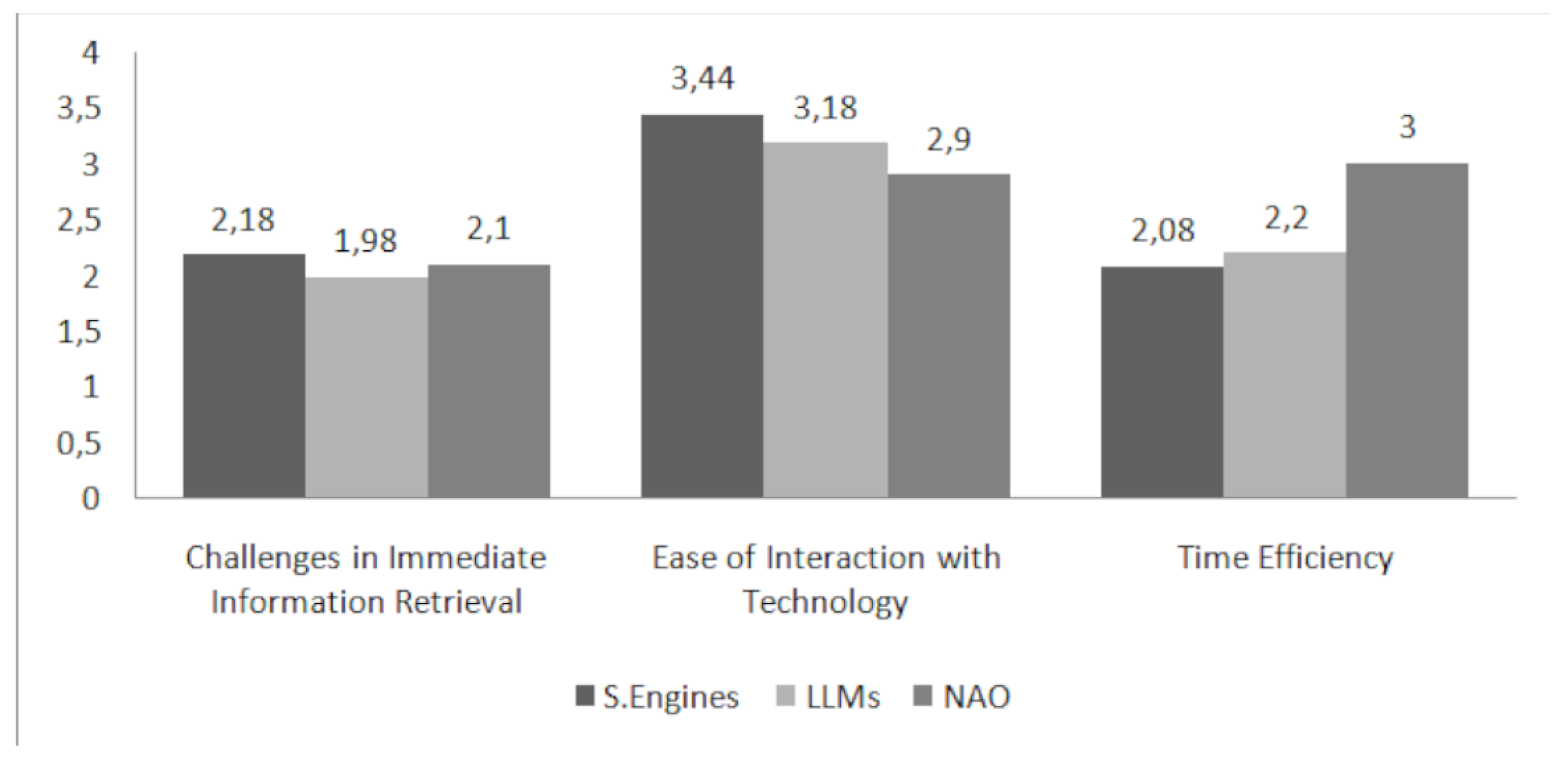

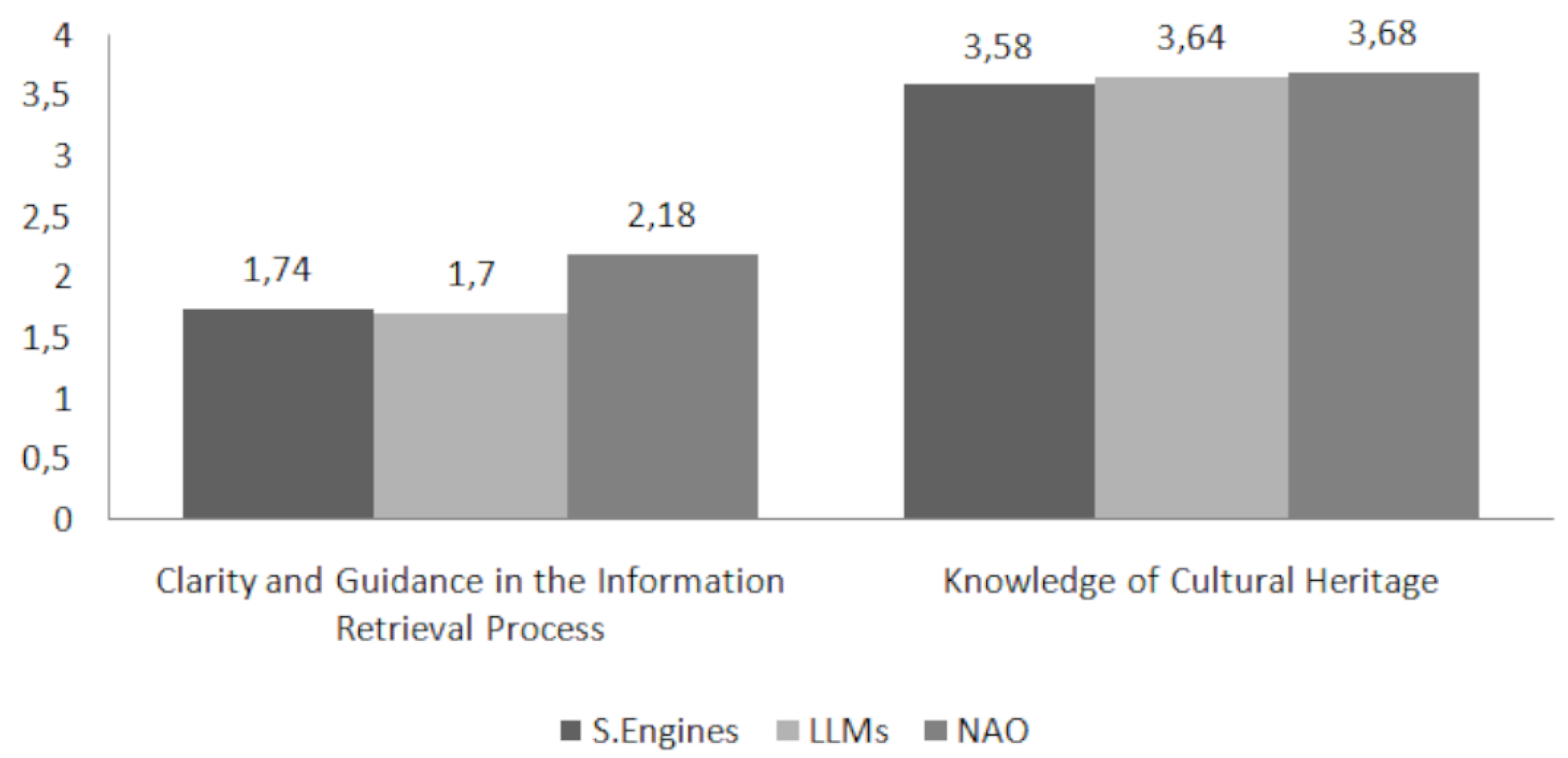

4.1. 1st Category: Comparative Evaluation of Methods for Retrieving Cultural Heritage Information

- Did you find the information you were looking for easily?

- Did you have trouble finding information about cultural heritage?

- Was the process of searching for information fun?

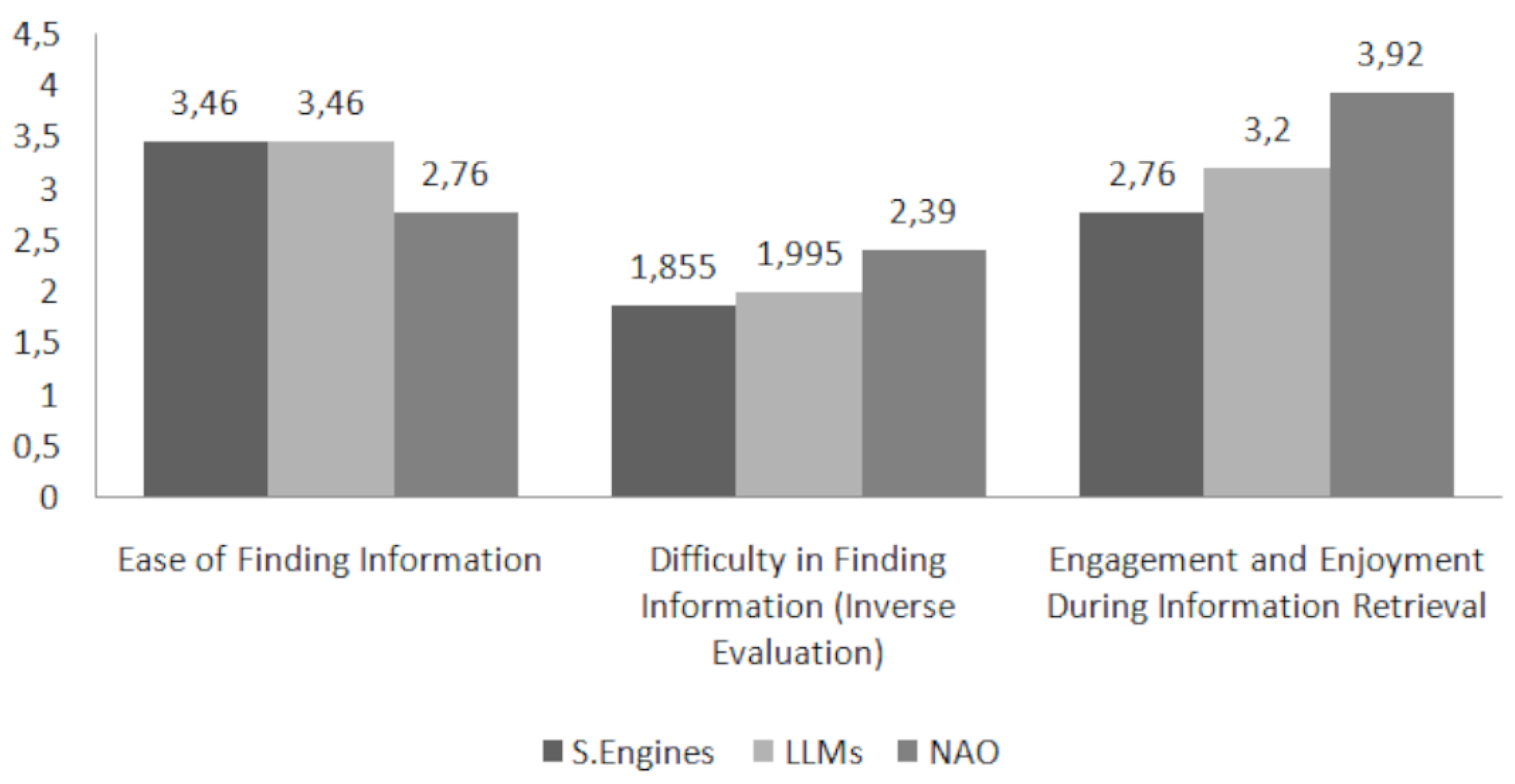

- Would you like to do more work with this technology?

- Do you think you can use this technology without the help of the teacher?

- Do you think this technology "knows" everything?

- Were there any questions you did not immediately find with this technology?

- Do you find it easy to interact with this technology?

- Did you spend a lot of time on each question?

- Did this technology confuse you in your search for information?

- Did each technology have knowledge of cultural heritage?

4.2. Summary of Results of 1st Category

4.2.1. Search Engines: High Efficiency and Usability, Low Engagement

4.2.2. LLMs: Balanced Usability and Engagement, Moderate Autonomy

4.2.3. NAO Robot: High Engagement, Challenges in Efficiency and Usability

4.2.4. Comparison Between Engagement and Efficiency Across Methods

4.2.5. Cultural Heritage Knowledge Across Methods

4.3. 2nd Category: General Comparison of Information Retrieval Methods

4.4. Summary of Results of 2nd Category

4.5. 3rd Category: NAO-Specific Interaction

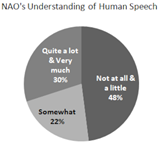

4.5.1. Interaction and Acoustic Skills

| Question | Graph | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| NAO’s Understanding of Human Speech |  |

The responses indicate mixed satisfaction with NAO’s ability to understand students, with a significant portion (24) expressing dissatisfaction. This suggests that NAO’s auditory recognition system may need improvement to better meet user expectations. |

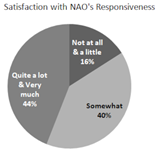

| Satisfaction with NAO’s Responsiveness |  |

The majority of students were either somewhat or highly satisfied with NAO’s responses, indicating that while there is room for improvement, NAO generally provides acceptable answers to student queries. |

| Perceptions of NAO’s Auditory Improvements |  |

Most students (29) perceive improvements in NAO’s auditory system, which could reflect gradual adaptation or better understanding of its limitations over time. |

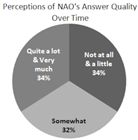

| Perceptions of NAO’s Answer Quality Over Time |  |

Responses are evenly distributed, with many students believing that NAO’s answers have room for improvement. This suggests that while NAO’s current performance is acceptable to some, others see significant potential for enhancement in its responses. |

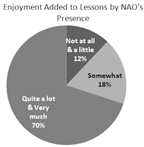

| Enjoyment Added to Lessons by NAO’s Presence |  |

The majority of students (35) found the interaction with NAO enjoyable, highlighting its ability to create an engaging classroom atmosphere. |

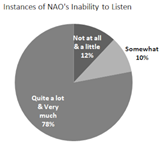

| Instances of NAO’s Inability to Listen |  |

A high number of students (39) reported that NAO frequently failed to listen, indicating a critical area for improvement in its auditory responsiveness. |

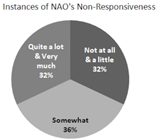

| Instances of NAO’s Non-Responsiveness |  |

The responses suggest that NAO occasionally fails to respond, which might disrupt the interaction flow and frustrate users. |

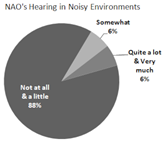

| NAO’s Hearing in Noisy Environments |  |

The overwhelming majority (44) reported that NAO struggled to hear in noisy environments, emphasizing the need for better noise-cancellation features. |

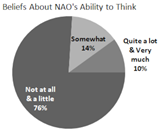

| Beliefs About NAO’s Ability to Think |  |

Most students (38) do not perceive NAO as capable of independent thought, reflecting its current limitations as a pre-programmed robot. |

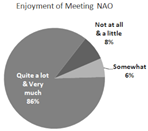

| Enjoyment of Meeting NAO |  |

The vast majority (43) enjoyed meeting NAO, showcasing its novelty and appeal as a humanoid robot in the classroom. |

4.5.2. Perceptions of NAO and Robotics

| Question | Graph | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

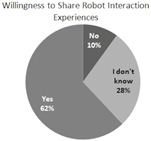

| Willingness to Share Robot Interaction Experiences |  |

Most students (31) would share their experience, suggesting that interacting with NAO is a unique and exciting event worth discussing. |

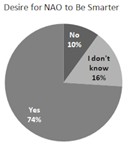

| Desire for NAO to Be Smarter |  |

The majority (37) would prefer a smarter NAO, reflecting students’ desire for more advanced capabilities. |

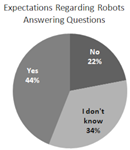

| Expectations Regarding Robots Answering Questions |  |

While many (22) expected NAO to answer questions, a significant portion (28) were either uncertain or skeptical, indicating mixed prior expectations. |

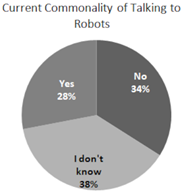

| Current Commonality of Talking to Robots |  |

Responses suggest that robot interactions are not yet widely perceived as common, highlighting the novelty of such experiences. |

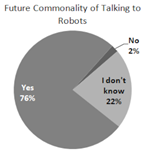

| Future Commonality of Talking to Robots |  |

Most students (38) believe that robot interactions will become common, reflecting optimism about the future of robotics. |

| Desire for Robot Conversations to Be Common in the Future |  |

A smaller majority (20) support the idea of frequent robot conversations, indicating some hesitation about widespread adoption. |

4.6. Summary of Results of 3rd Category

5. Discussion

5.1. Efficiency vs. Engagement

5.2. Students’ Perception of Robots

5.3. Cultural Heritage Knowledge and Pedagogical Goals

5.4. NAO’s Acoustic Challenges

5.5. Future Orientations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| STEM | Science Technology Engineering Mathematics |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

References

- Company, T.B.R. Educational Robot Global Market Report. 2024; Accessed on September 9, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi, A.; Uribe, L. Robotics to promote STEM learning: Educational robotics unit for 4th grade science. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC); 2017; pp. 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitti, F.B.V.; Spolaôr, N. How Have Robots Supported STEM Teaching? In Robotics in STEM Education: Redesigning the Learning Experience; Khine, M.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evripidou, S.; Georgiou, K.; Doitsidis, L.; Amanatiadis, A.A.; Zinonos, Z.; Chatzichristofis, S.A. Educational Robotics: Platforms, Competitions and Expected Learning Outcomes. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 219534–219562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimisis, D. Educational robotics: Open questions and new challenges. Themes in Science and Technology Education 2013, 6, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin, S.; Ismail, L.I.; Yussof, H.; Ismarrubie Zahari, N.; Bahari, S.; Hashim, H.; Jaffar, A. Humanoid robot NAO: Review of control and motion exploration. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering; 2011; pp. 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirova, A.; Rakhymbayeva, N.; Yadollahi, E.; Sandygulova, A.; Johal, W. 10 Years of Human-NAO Interaction Research: A Scoping Review. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdanivia Alarcon, D.A.; Cano, S.; Paucar, F.H.R.; Quispe, R.F.P.; Talavera-Mendoza, F.; Zegarra, M.E.R. Exploring the Effect of Robot-Based Video Interventions for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder as an Alternative to Remote Education. Electronics 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienza, M.; Laus, F.; Guglielmi, V.; Carriero, G.; Grisolia, M.; Palermo, G.; Pierri, F.; Turi, M.; Muratori, F.; Bloisi, D.; et al. HRI-based Gaze-contingent Eye Tracking for Autism Spectrum Disorder Treatment: A preliminary study using a NAO robot. In Proceedings of the 2023 32nd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2023; pp. 2665–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johal, W. Research Trends in Social Robots for Learning. Current Robotics Reports 2020, 1, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, O.O.; Hamad, N.M.A.; Chisom, O.N.; Osawaru, B.; Adewusi, E. AI in education: A review of personalized learning and educational technology. GSC Advanced Research and Reviews 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Atlas, S. ChatGPT for higher education and professional development: A guide to conversational AI. Digital Commons URI 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bungert, K.; Bruckschen, L.; Müller, K.; Bennewitz, M. Robots in Education: Influence on Learning Experience and Design Considerations. In Proceedings of the 2020 European Conference on Education (ECE); 2020; pp. 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaeian, H.; Gilanlioglu, I. Influence of the NAO robot as a teaching assistant on university students’ vocabulary learning and attitudes. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 2021, 37, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchem, I.; Thomas, E. A BREATHING EXERCISE WITH THE HUMANOID ROBOT NAO DESIGNED TO REDUCE STUDENT STRESS DURING CLASS: RESULTS FROM A PILOT STUDY WITH STUDENTS IN HIGHER EDUCATION. In Proceedings of the ICERI2022 Proceedings. IATED, 7-9 November, 2022 2022, 15th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation; pp. 6545–6551. [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A.-E.; Goldman, E.J.; Meltzer, A.; Poulin-Dubois, D. People Do Not Always Know Best: Preschoolers’ Trust in Social Robots. Journal of Cognition and Development 2023, 24, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podpečan, V. Can You Dance? A Study of Child–Robot Interaction and Emotional Response Using the NAO Robot. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gressmann, A.; Weilemann, E.; Meyer, D.; Bergande, B. Nao Robot vs. Lego Mindstorms: The Influence on the Intrinsic Motivation of Computer Science Non-Majors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 19th Koli Calling International Conference on Computing Education Research, New York, NY, USA, 2019. Koli Calling ’19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valagkouti, I.A.; Troussas, C.; Krouska, A.; Feidakis, M.; Sgouropoulou, C. Emotion Recognition in Human–Robot Interaction Using the NAO Robot. Computers 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruofei Zhang, D.Z.; Cheng, G. A review of chatbot-assisted learning: pedagogical approaches, implementations, factors leading to effectiveness, theories, and future directions. Interactive Learning Environments 2023, 0, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Wu, Y. Exploring the use of ChatGPT to foster EFL learners’ critical thinking skills from a post-humanist perspective. Thinking Skills and Creativity 2024, 54, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglez, D.; Kerneža, M. Integrating Generative Language Models in Lesson Planning: A Case Study; University of Maribor Press, 2024; pp. 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutawa, A.M.; Al Mudhahkah, H.M.; Al-Huwais, A.; Al-Khaldi, N.; Al-Otaibi, R.; Al-Ansari, A. Augmenting Mobile App with NAO Robot for Autism Education. Machines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement and Enjoyment |  |

NAO was overwhelmingly chosen as the most fun method (43 out of 50 students), far surpassing search engines and LLMs (3 and 4 votes, respectively). NAO’s interactive and humanoid characteristics resonate strongly with students, making it an engaging choice for activities prioritizing enjoyment. |

| Efficiency and Speed |  |

The data on time consumption in method use reveals that students spent the least time using search engines (12), followed by LLMs (15), while the NAO robot required the most time (23). This suggests that search engines are the most time-efficient tool for retrieving information, likely due to their straightforward interface and familiar usage patterns.The NAO robot, demands significantly more time. |

| Reliability and Familiarity |  |

Search engines and LLMs were equally perceived as the most reliable methods (20 and 21 votes, respectively), with NAO trailing at 9 votes. Search engines were overwhelmingly seen as the most common method (47 votes), underscoring their familiarity and integration into students’ daily lives. Familiarity and reliability make search engines and LLMs dependable choices, while NAO might require additional training or familiarity to build trust. |

| Future Preferences |  |

Students showed a balanced preference for using NAO (21 votes) and LLMs (18 votes) in future exercises, with search engines trailing (11 votes). While search engines remain a default choice, the novelty and interactive nature of NAO and the adaptability of LLMs appeal to students for future use. |

| Areas for Improvement |  |

NAO was identified as the method most in need of improvement (26 votes), followed by LLMs (16 votes) and search engines (8 votes). NAO’s lower usability and efficiency likely drive this perception, indicating areas for refinement in its design and functionality. |

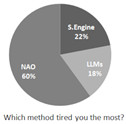

| Fatigue and Cognitive Load |  |

NAO was reported as the most tiring method (30 votes), significantly more than search engines (11 votes) and LLMs (9 votes). The cognitive and physical effort required to interact with NAO may detract from its overall effectiveness, particularly for longer or more complex tasks. |

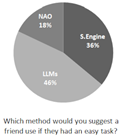

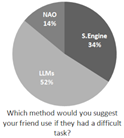

| Task Recommendations |  |

Students recommended LLMs for difficult tasks (23 votes), followed by search engines (18 votes) and NAO (9 votes).For easier tasks, search engines and LLMs were nearly tied (17 and 26 votes, respectively), with NAO trailing (7 votes). LLMs’ adaptability and ability to handle complex queries make them the preferred choice for challenging tasks, while search engines remain a go-to option for straightforward needs. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).