Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Date and Methods

2.1. GEOS-Chem Model Description

2.2. Numerical Experiments

2.3. Model Evaluation

2.3.1. GOSAT Total Column CO2 (XCO2) Observations

- Screening the a priori values to exclude abnormal or missing data.

- Re-matching the valid a priori values with the atmospheric pressure.

- Interpolating horizontally to obtain simulated data that matches the longitude and latitude of the GOSAT data.

- Interpolating vertically to obtain simulated data that matches the layers of the GOSAT data.

- Using the processed simulated data from the above steps in equation (1) to compute the simulated XCO2.

2.3.2. Surface CO2 Observations

- Horizontal interpolation was applied to match the latitude and longitude of the observation sites with the simulated data.

- Vertical interpolation was performed to match the elevation of the observation sites with the simulated data.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Simulation Verification Results

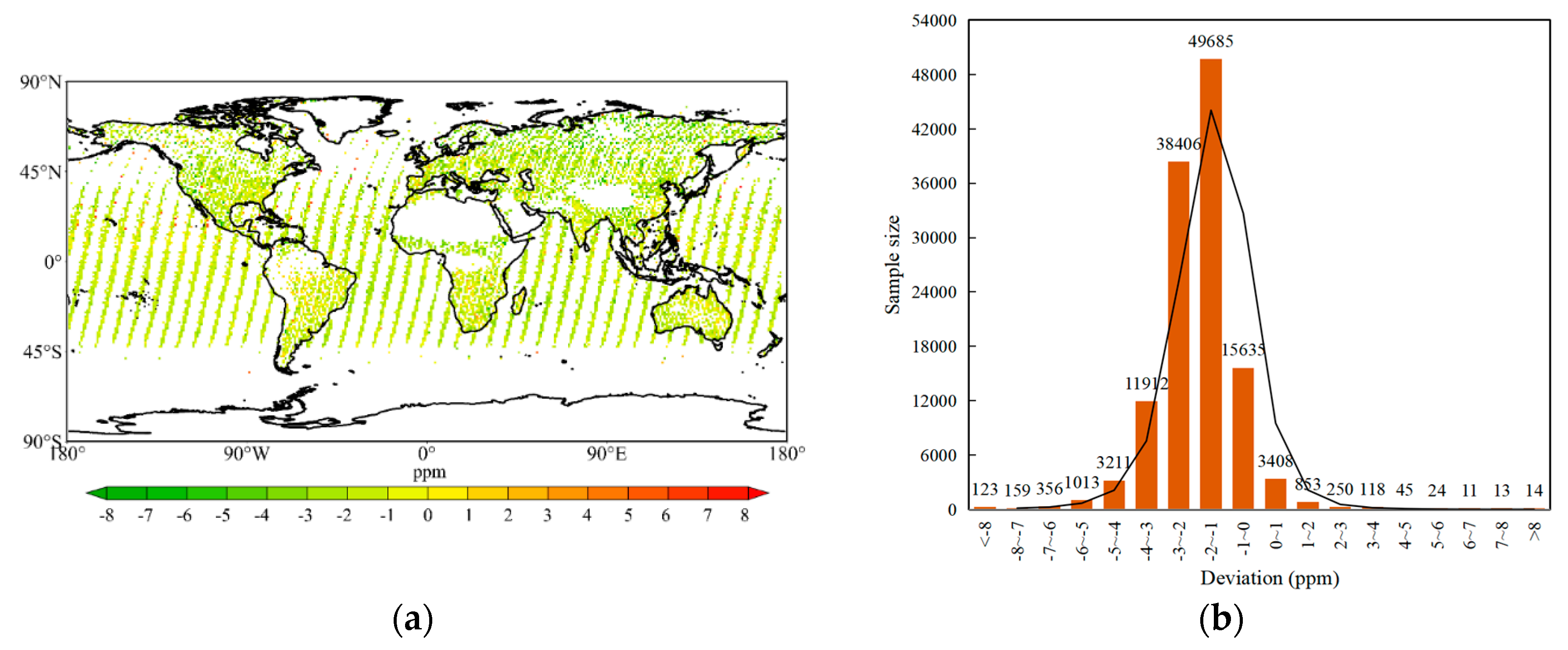

3.1.1. Verification Results of Satellite Observations

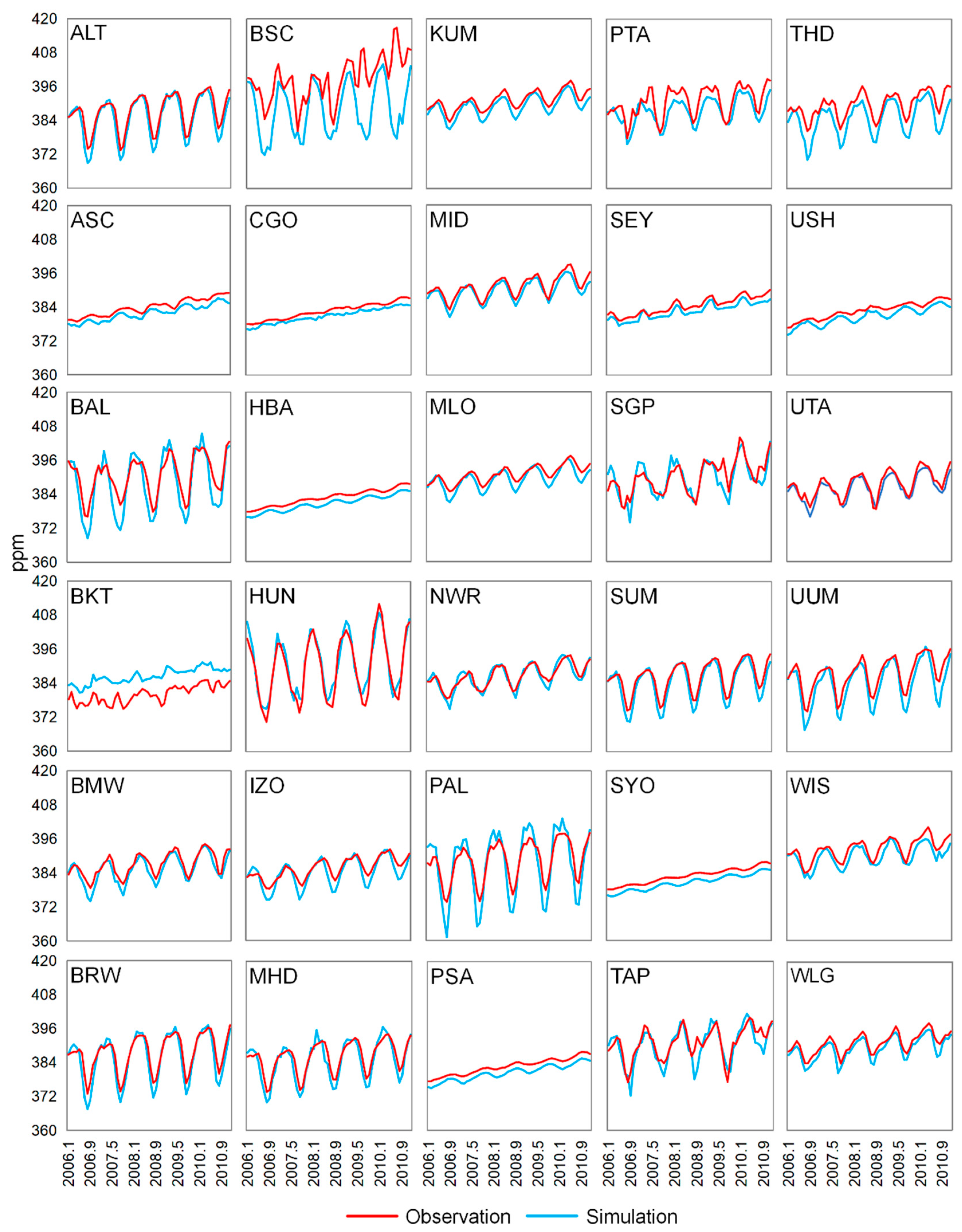

3.1.2. Verification Results of Surface Observation

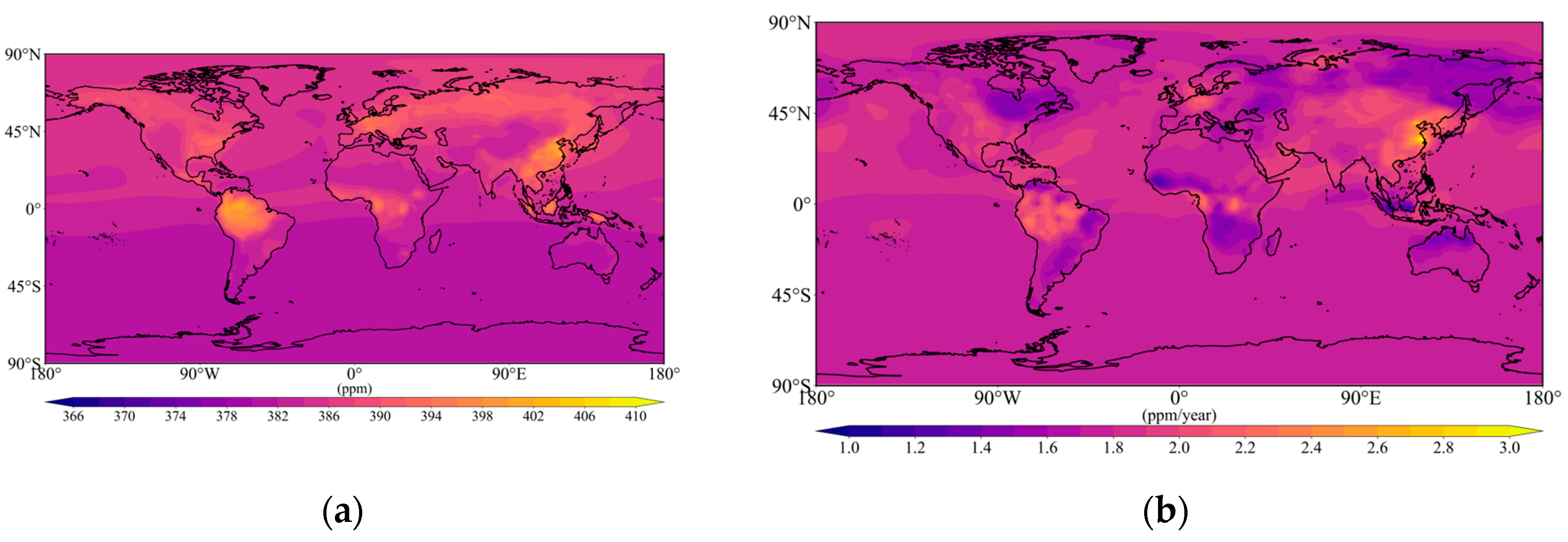

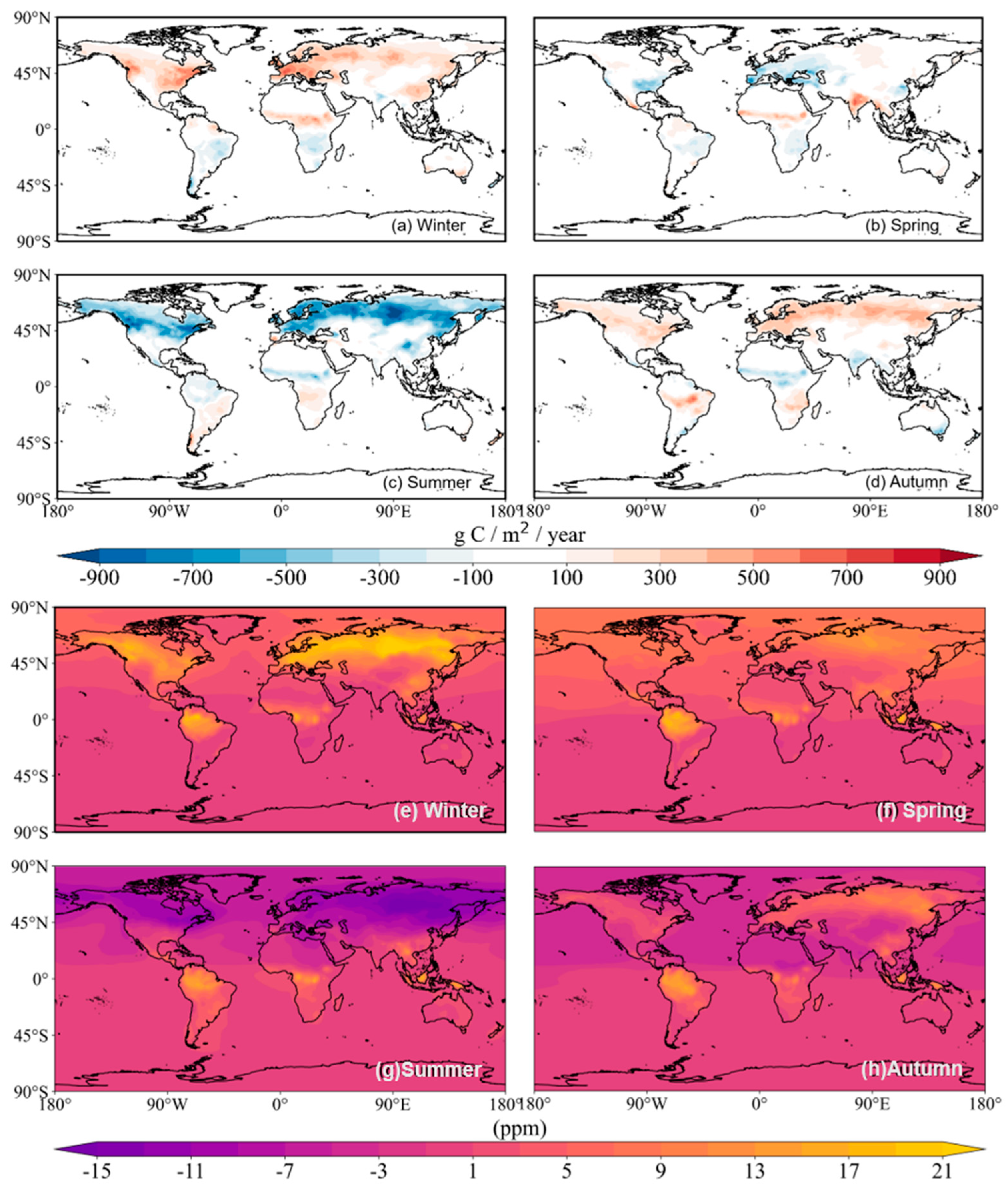

3.2. Temporal and Spatial Characteristics of Global Simulated Atmospheric CO2 Concentration

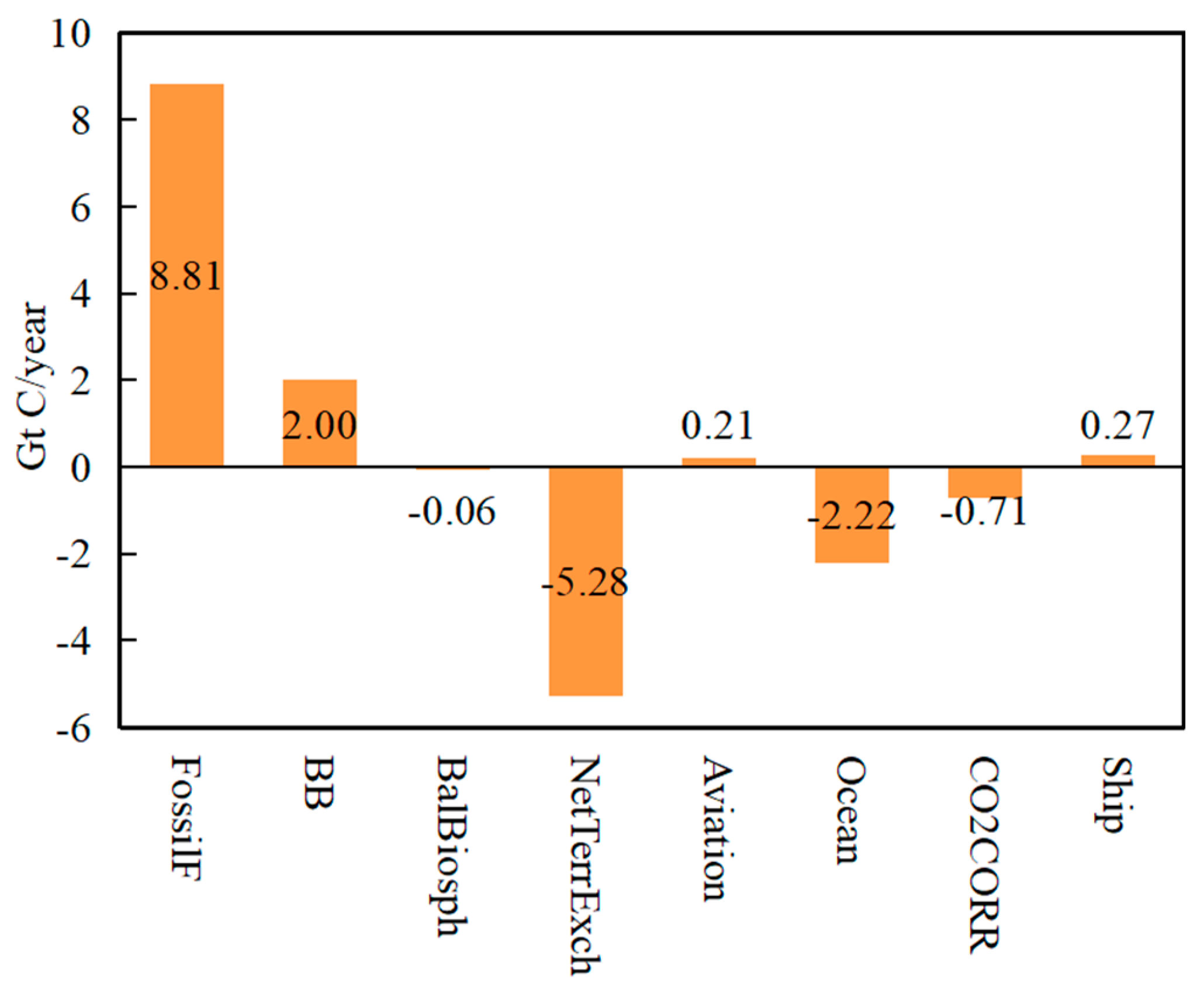

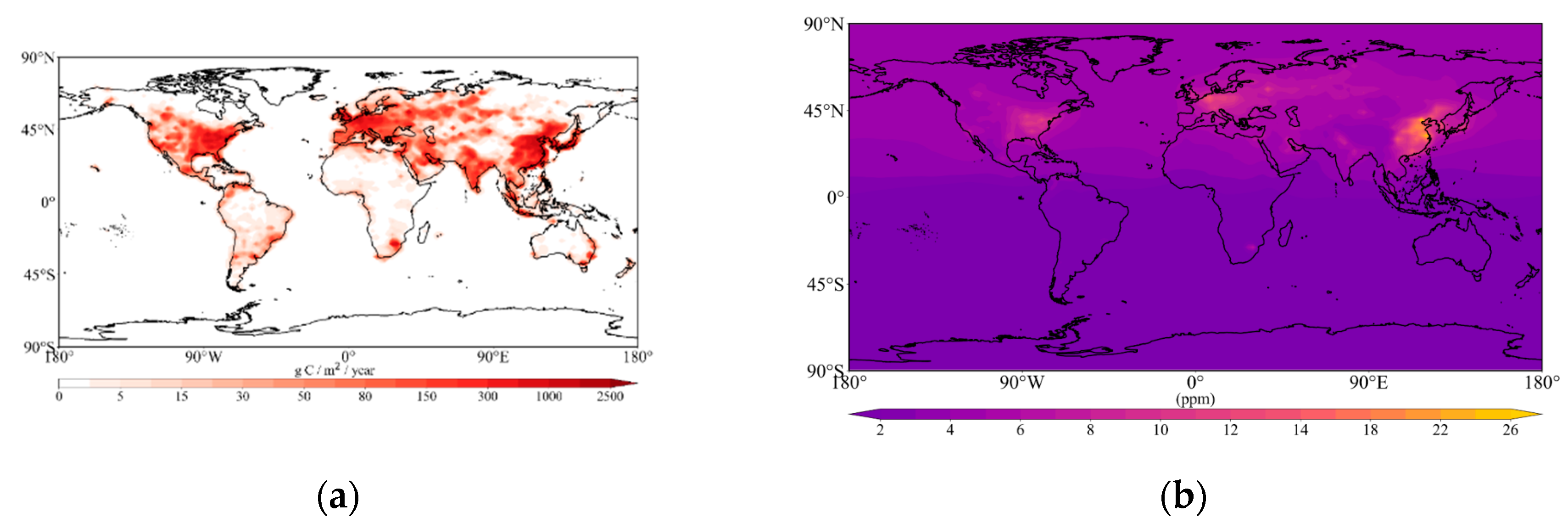

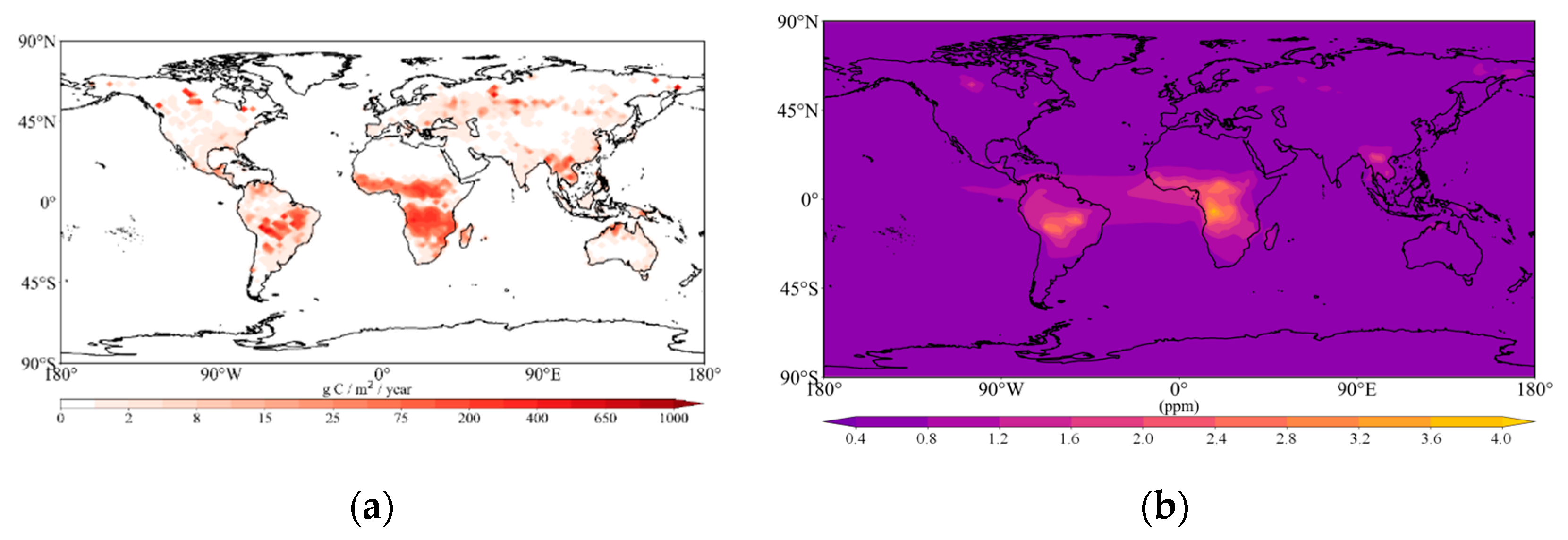

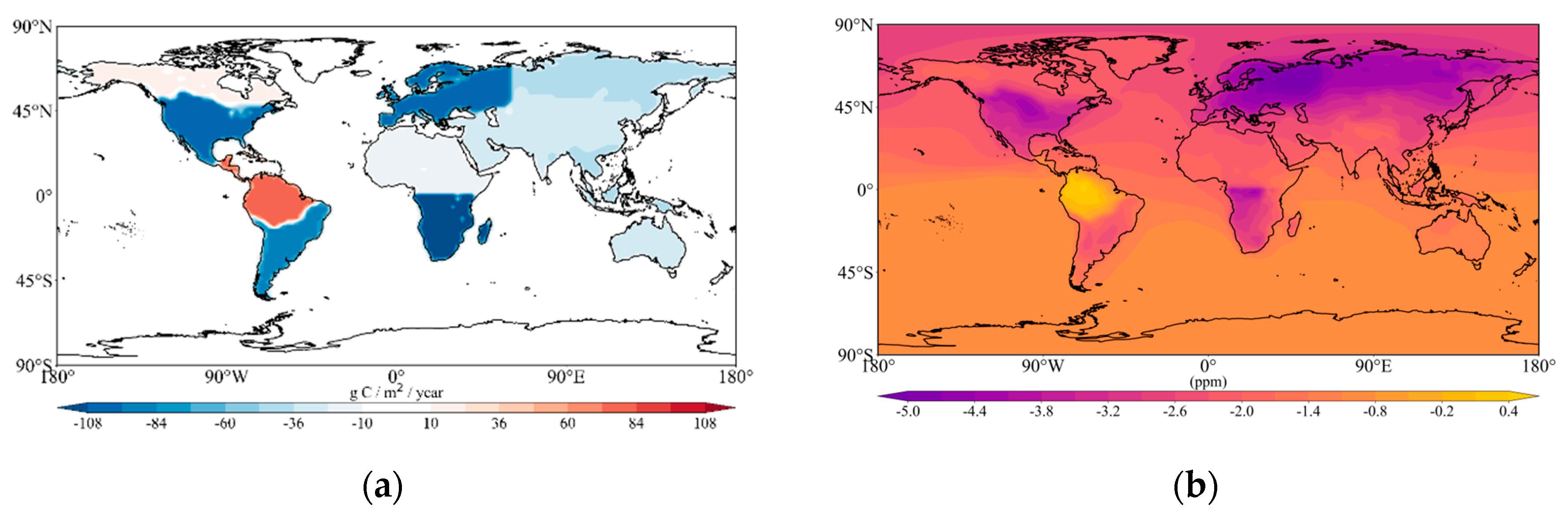

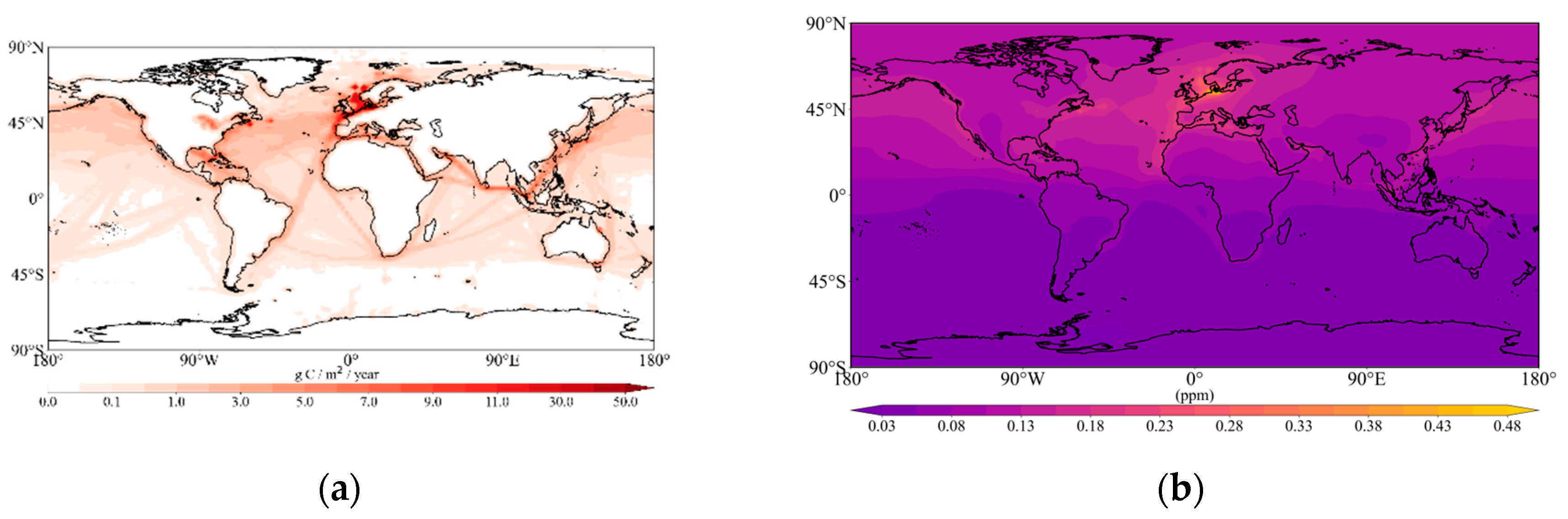

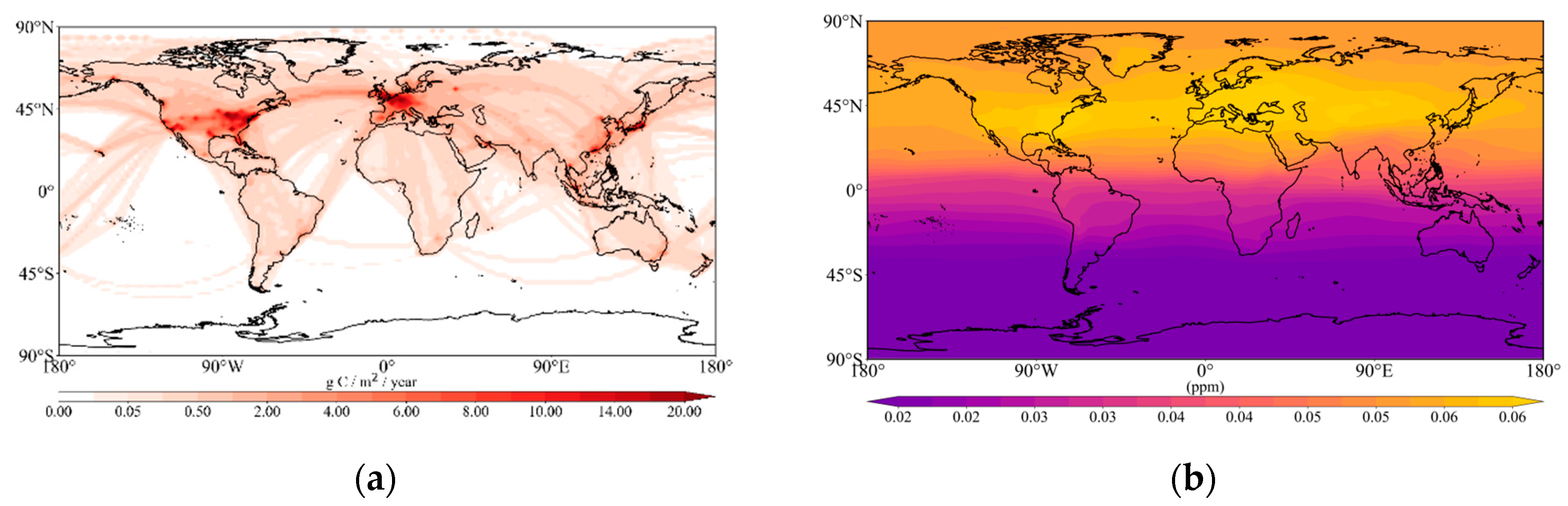

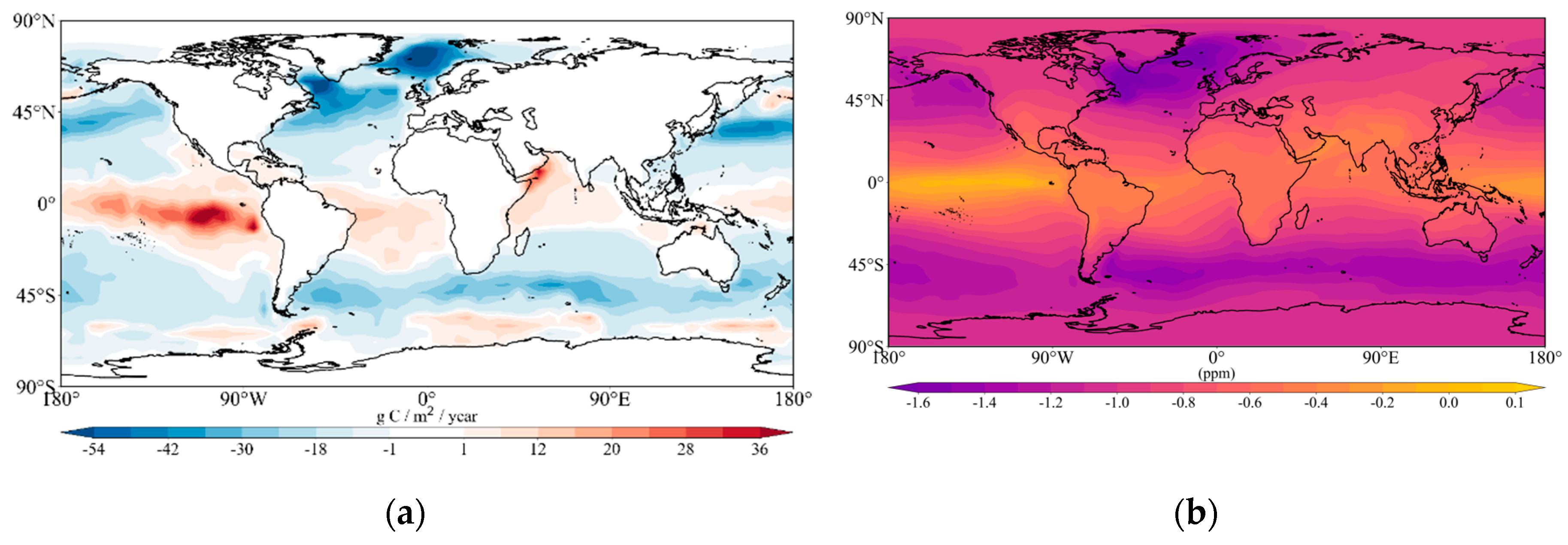

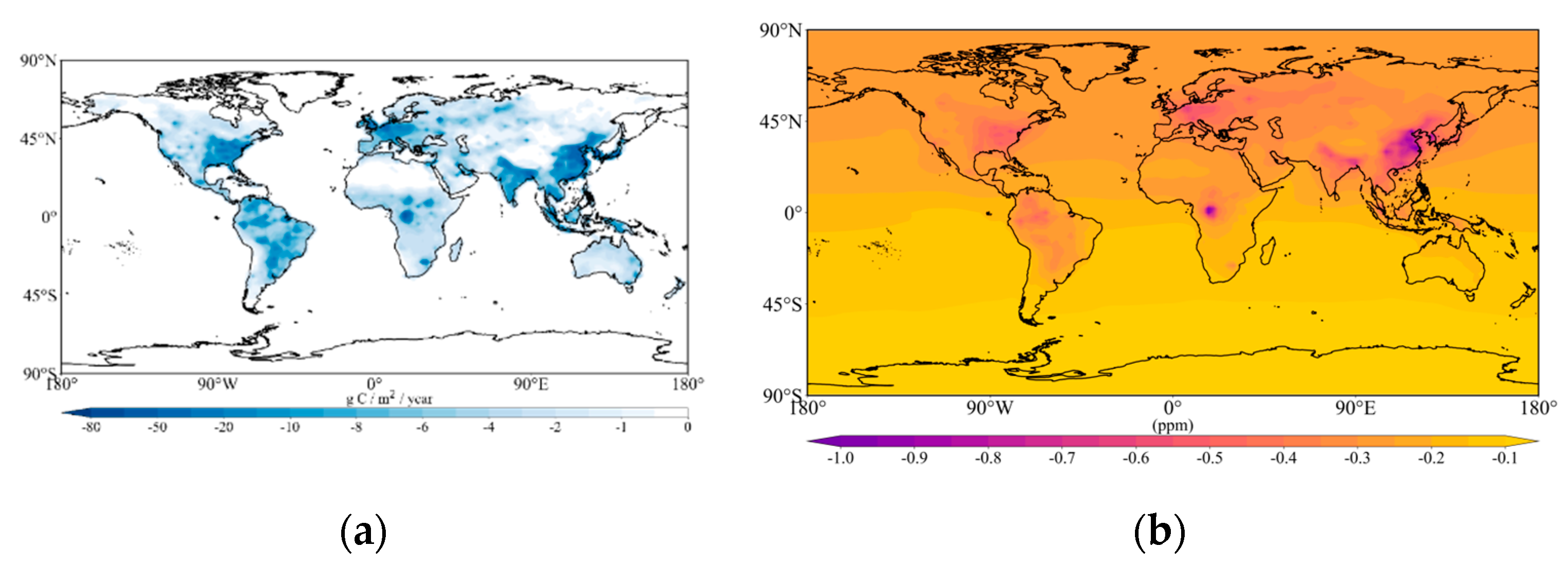

3.3. Effects of Different CO2 Sources on Atmospheric CO2 Concentration

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Landschützer, P.; Le Quéré, C.; Li, H.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2024 2024.

- Bauska, T.K.; Joos, F.; Mix, A.C.; Roth, R.; Ahn, J.; Brook, E.J. Links between Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide, the Land Carbon Reservoir and Climate over the Past Millennium. Nat Geosci 2015, 8, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.F.; Prentice, I.C.; Canadell, J.G.; Williams, C.A.; Wang, H.; Raupach, M.; Collatz, G.J. Recent Pause in the Growth Rate of Atmospheric CO2 Due to Enhanced Terrestrial Carbon Uptake. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, J.; Olsson, T.; Schultz, D.M.; Baklanov, A.; Klein, T.; Miranda, A.I.; Monteiro, A.; Hirtl, M.; Tarvainen, V.; Boy, M.; et al. A Review of Operational, Regional-Scale, Chemical Weather Forecasting Models in Europe. Atmos Chem Phys 2012, 12, 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Palmer, P.I.; Yang, Y.; Yantosca, R.M.; Kawa, S.R.; Paris, J.-D.; Matsueda, H.; Machida, T. Evaluating a 3-D Transport Model of Atmospheric CO2 Using Ground-Based, Aircraft, and Space-Borne Data. Atmos Chem Phys 2011, 11, 2789–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Han, P.; Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Oda, T.; Martin, C.; Liu, Z.; Yao, B.; Sun, W.; Wang, P.; et al. Global to Local Impacts on Atmospheric CO2 from the COVID-19 Lockdown, Biosphere and Weather Variabilities. Environmental Research Letters 2022, 17, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntharalingam, P.; Spivakovsky, C.M.; Logan, J.A.; McElroy, M.B. Estimating the Distribution of Terrestrial CO2 Sources and Sinks from Atmospheric Measurements: Sensitivity to Configuration of the Observation Network. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.; Jones, D.B.A.; Suntharalingam, P.; Chen, J.M.; Andres, R.J.; Wecht, K.J.; Yantosca, R.M.; Kulawik, S.S.; Bowman, K.W.; Worden, J.R.; et al. Modeling Global Atmospheric CO2 with Improved Emission Inventories and CO2 Production from the Oxidation of Other Carbon Species. Geosci Model Dev 2010, 3, 689–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randerson, J.T.; Thompson, M. V.; Conway, T.J.; Fung, I.Y.; Field, C.B. The Contribution of Terrestrial Sources and Sinks to Trends in the Seasonal Cycle of Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Global Biogeochem Cycles 1997, 11, 535–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntharalingam, P.; Jacob, D.J.; Palmer, P.I.; Logan, J.A.; Yantosca, R.M.; Xiao, Y.; Evans, M.J.; Streets, D.G.; Vay, S.L.; Sachse, G.W. Improved Quantification of Chinese Carbon Fluxes Using CO2 /CO Correlations in Asian Outflow. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2004, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.; Jones, D.B.A.; Suntharalingam, P.; Chen, J.M.; Andres, R.J.; Wecht, K.J.; Yantosca, R.M.; Kulawik, S.S.; Bowman, K.W.; Worden, J.R.; et al. Modeling Global Atmospheric CO2 with Improved Emission Inventories and CO2 Production from the Oxidation of Other Carbon Species. Geosci Model Dev 2010, 3, 689–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaro, R.; McCarty, W.; Suárez, M.J.; Todling, R.; Molod, A.; Takacs, L.; Randles, C.A.; Darmenov, A.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Reichle, R.; et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J Clim 2017, 30, 5419–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster R D, D.A.S. da S.A.M. The Quick Fire Emissions Dataset (QFED): Documentation of Versions 2.1, 2.2 and 2. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, T.; Maksyutov, S. A Very High-Resolution (1 Km×1 Km) Global Fossil Fuel CO2 Emission Inventory Derived Using a Point Source Database and Satellite Observations of Nighttime Lights. Atmos Chem Phys 2011, 11, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Sutherland, S.C.; Wanninkhof, R.; Sweeney, C.; Feely, R.A.; Chipman, D.W.; Hales, B.; Friederich, G.; Chavez, F.; Sabine, C.; et al. Climatological Mean and Decadal Change in Surface Ocean PCO2, and Net Sea–Air CO2 Flux over the Global Oceans. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2009, 56, 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messerschmidt, J.; Parazoo, N.; Wunch, D.; Deutscher, N.M.; Roehl, C.; Warneke, T.; Wennberg, P.O. Evaluation of Seasonal Atmosphere–Biosphere Exchange Estimations with TCCON Measurements. Atmos Chem Phys 2013, 13, 5103–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.F.; Law, R.M.; Gurney, K.R.; Rayner, P.; Peylin, P.; Denning, A.S.; Bousquet, P.; Bruhwiler, L.; Chen, Y. -H.; Ciais, P.; et al. TransCom 3 Inversion Intercomparison: Impact of Transport Model Errors on the Interannual Variability of Regional CO2 Fluxes, 1988–2003. Global Biogeochem Cycles 2006, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesly, R.M.; Smith, S.J.; Feng, L.; Klimont, Z.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; Pitkanen, T.; Seibert, J.J.; Vu, L.; Andres, R.J.; Bolt, R.M.; et al. Historical (1750–2014) Anthropogenic Emissions of Reactive Gases and Aerosols from the Community Emissions Data System (CEDS). Geosci Model Dev 2018, 11, 369–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.C.; Brasseur, G.P.; Wuebbles, D.J.; Barrett, S.R.H.; Dang, H.; Eastham, S.D.; Jacobson, M.Z.; Khodayari, A.; Selkirk, H.; Sokolov, A.; et al. Comparison of Model Estimates of the Effects of Aviation Emissions on Atmospheric Ozone and Methane. Geophys Res Lett 2013, 40, 6004–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.; Jones, D.B.A.; Suntharalingam, P.; Chen, J.M.; Andres, R.J.; Wecht, K.J.; Yantosca, R.M.; Kulawik, S.S.; Bowman, K.W.; Worden, J.R.; et al. Modeling Global Atmospheric CO2 with Improved Emission Inventories and CO2 Production from the Oxidation of Other Carbon Species. Geosci Model Dev 2010, 3, 689–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liao, H.; Tian, X.; Gao, H.; Jia, B.; Han, R. Impact of Prior Terrestrial Carbon Fluxes on Simulations of Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddington, C.L.; Conibear, L.; Robinson, S.; Knote, C.; Arnold, S.R.; Spracklen, D. V. Air Pollution From Forest and Vegetation Fires in Southeast Asia Disproportionately Impacts the Poor. Geohealth 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Beig, G.; Song, S.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J.; Ying, Q.; Liang, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, X.; et al. The Impact of Power Generation Emissions on Ambient PM2.5 Pollution and Human Health in China and India. Environ Int 2018, 121, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Zhang, M.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Y. Assessment of the Biospheric Contribution to Surface Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations over East Asia with a Regional Chemical Transport Model. Adv Atmos Sci 2015, 32, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, P.; Chen, L.; Xu, N.; Ma, Y. Global Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations Simulated by GEOS-Chem: Comparison with GOSAT, Carbon Tracker and Ground-Based Measurements. Atmosphere (Basel) 2018, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunch, D.; Toon, G.C.; Blavier, J.-F.L.; Washenfelder, R.A.; Notholt, J.; Connor, B.J.; Griffith, D.W.T.; Sherlock, V.; Wennberg, P.O. The Total Carbon Column Observing Network. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2011, 369, 2087–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbasi, S.; Malakooti, H.; Rahnama, M.; Azadi, M. Study of Mid-Latitude Retrieval XCO2 Greenhouse Gas: Validation of Satellite-Based Shortwave Infrared Spectroscopy with Ground-Based TCCON Observations. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 836, 155513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, A.J.; Boesch, H.; Parker, R.J.; Feng, L.; Palmer, P.I.; Blavier, J. -F. L.; Deutscher, N.M.; Macatangay, R.; Notholt, J.; Roehl, C.; et al. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Retrieved from the Greenhouse Gases Observing SATellite (GOSAT): Comparison with Ground-based TCCON Observations and GEOS-Chem Model Calculations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, H.; O’Dell, C.W.; Basu, S.; Boesch, H.; Chevallier, F.; Deutscher, N.; Feng, L.; Fisher, B.; Hase, F.; Inoue, M.; et al. Does GOSAT Capture the True Seasonal Cycle of Carbon Dioxide? Atmos Chem Phys 2015, 15, 13023–13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morino, I.; Uchino, O.; Inoue, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Yokota, T.; Wennberg, P.O.; Toon, G.C.; Wunch, D.; Roehl, C.M.; Notholt, J.; et al. Preliminary Validation of Column-Averaged Volume Mixing Ratios of Carbon Dioxide and Methane Retrieved from GOSAT Short-Wavelength Infrared Spectra 2010.

- Connor, B.J.; Boesch, H.; Toon, G.; Sen, B.; Miller, C.; Crisp, D. Orbiting Carbon Observatory: Inverse Method and Prospective Error Analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masarie, K.A.; Peters, W.; Jacobson, A.R.; Tans, P.P. ObsPack: A Framework for the Preparation, Delivery, and Attribution of Atmospheric Greenhouse Gas Measurements. Earth Syst Sci Data 2014, 6, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liao, H.; Tian, X.-J.; Gao, H.; Cai, Z.-N.; Han, R. Sensitivity of the Simulated CO2 Concentration to Inter-Annual Variations of Its Sources and Sinks over East Asia. Advances in Climate Change Research 2019, 10, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, M.; Chen, L.; Kou, X.; Skorokhod, A. CMAQ Simulation of Atmospheric CO2 Concentration in East Asia: Comparison with GOSAT Observations and Ground Measurements. Atmos Environ 2017, 160, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liao, H.; Tian, X.; Gao, H.; Jia, B.; Han, R. Impact of Prior Terrestrial Carbon Fluxes on Simulations of Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Zhu, J.; Zeng, N. Improved Simulation of Regional CO2 Surface Concentrations Using GEOS-Chem and Fluxes from VEGAS. Atmos Chem Phys 2013, 13, 7607–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, T.; Heutel, G.; Miller, N.H.; Molitor, D.; Reif, J. The Mortality and Medical Costs of Air Pollution: Evidence from Changes in Wind Direction. American Economic Review 2019, 109, 4178–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, T.; Heutel, G.; Miller, N.H.; Molitor, D.; Reif, J. The Mortality and Medical Costs of Air Pollution: Evidence from Changes in Wind Direction. American Economic Review 2019, 109, 4178–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; He, Y.; Ye, Y.; Liu, C. Employ Mathematical Modeling to Summarize, Analyze, And Predict the Relationship Between Carbon Dioxide and Temperature, Location, And Other Factors. Academic Journal of Science and Technology 2024, 11, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, M. Investigating the Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions in China’s Transportation Industry from a Structural Adjustment Perspective. Atmos Pollut Res 2024, 15, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guan, Y.; Shan, Y.; Cui, C.; Hubacek, K. Emission Growth and Drivers in Mainland Southeast Asian Countries. J Environ Manage 2023, 329, 117034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkel, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Rödenbeck, C.; Keeling, R.; Heimann, M.; Thonicke, K.; Zaehle, S.; Reichstein, M. Enhanced Seasonal CO2 Exchange Caused by Amplified Plant Productivity in Northern Ecosystems. Science (1979) 2016, 351, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Rogers, B.M.; Sweeney, C.; Chevallier, F.; Arshinov, M.; Dlugokencky, E.; Machida, T.; Sasakawa, M.; Tans, P.; Keppel-Aleks, G. Siberian and Temperate Ecosystems Shape Northern Hemisphere Atmospheric CO2 Seasonal Amplification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 21079–21087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quéré, C.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.W.; Smith, A.J.P.; Abernethy, S.; Andrew, R.M.; De-Gol, A.J.; Willis, D.R.; Shan, Y.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. Temporary Reduction in Daily Global CO2 Emissions during the COVID-19 Forced Confinement. Nat Clim Chang 2020, 10, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, C.; Ristovski, Z.; Milic, A.; Gu, Y.; Islam, M.S.; Wang, S.; Hao, J.; Zhang, H.; He, C.; et al. A Review of Biomass Burning: Emissions and Impacts on Air Quality, Health and Climate in China. Science of The Total Environment 2017, 579, 1000–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Long, X. A Review of the Ecological and Socioeconomic Effects of Biofuel and Energy Policy Recommendations. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 61, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.D.; van der Werf, G.R.; Shen, S.S.P. Human Amplification of Drought-Induced Biomass Burning in Indonesia since 1960. Nat Geosci 2009, 2, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, M.O.; Merlet, P. Emission of Trace Gases and Aerosols from Biomass Burning. Global Biogeochem Cycles 2001, 15, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, S.; Johnson, M.S.; Potter, C.; Genovesse, V.; Baker, D.F.; Haynes, K.D.; Henze, D.K.; Liu, J.; Poulter, B. Prior Biosphere Model Impact on Global Terrestrial CO2 Fluxes Estimated from OCO-2 Retrievals. Atmos Chem Phys 2019, 19, 13267–13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Fahey, D.W.; Skowron, A.; Allen, M.R.; Burkhardt, U.; Chen, Q.; Doherty, S.J.; Freeman, S.; Forster, P.M.; Fuglestvedt, J.; et al. The Contribution of Global Aviation to Anthropogenic Climate Forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmos Environ 2021, 244, 117834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.J.; Winebrake, J.J.; Green, E.H.; Kasibhatla, P.; Eyring, V.; Lauer, A. Mortality from Ship Emissions: A Global Assessment. Environ Sci Technol 2007, 41, 8512–8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landschützer, P.; Gruber, N.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Schuster, U. Recent Variability of the Global Ocean Carbon Sink. Global Biogeochem Cycles 2014, 28, 927–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Sutherland, S.C.; Wanninkhof, R.; Sweeney, C.; Feely, R.A.; Chipman, D.W.; Hales, B.; Friederich, G.; Chavez, F.; Sabine, C.; et al. Climatological Mean and Decadal Change in Surface Ocean PCO2, and Net Sea–Air CO2 Flux over the Global Oceans. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 2009, 56, 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, N.; Astor, Y.; Church, M.; Currie, K.; Dore, J.; Gonaález-Dávila, M.; Lorenzoni, L.; Muller-Karger, F.; Olafsson, J.; Santa-Casiano, M. A Time-Series View of Changing Ocean Chemistry Due to Ocean Uptake of Anthropogenic CO2 and Ocean Acidification. Oceanography 2014, 27, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, R.; Jones, D.B.A.; Suntharalingam, P.; Chen, J.M.; Andres, R.J.; Wecht, K.J.; Yantosca, R.M.; Kulawik, S.S.; Bowman, K.W.; Worden, J.R.; et al. Modeling Global Atmospheric CO2 with Improved Emission Inventories and CO2 Production from the Oxidation of Other Carbon Species. Geosci Model Dev 2010, 3, 689–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flux Type | Inventory Name Abbreviation |

Description | Spatial | Temporal | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Burning | QFED | Quick Fire Emissions Database for 2006-2010 | 0.1° × 0.1° | Daily | [13] |

| Fossil Fuel | ODIAC | Open source Data Inventory for Atmospheric CO₂ for 2006-2010 | 1° × 1° | Monthly | [14] |

| Ocean Exchange | Scaled oceanexchange | Scaled ocean exchange for 2006-2010 | 4° × 5° | Monthly | [15] |

| Balanced Biosphere | SIB3 | Balanced Net Ecosystem Production (NEP) CO₂ for 2006-2010 | 1° × 1.25° | 3-hourly | [16] |

| Net Terrestrial Exchange | TransCom climatology |

TransCom net terrestrial biospheric CO₂ fixed in 2000 | 1° × 1° | Fixed | [17] |

| Ship | CEDS | Community Emissions Data System for 2006-2010 | 0.5° × 0.5° | Monthly | [18] |

| Aviation | AEIC | Aircraft Emissions Inventory Code fixed in 2005 | 1°×1° | Monthly | [19] |

| Chemical Source | CO₂ Chemical Source | CO₂ chemical production from carbon species oxidation fixed in 2004 | 2°×2.5° | Monthly | [20] |

| Flux Type | Inventory Name Abbreviation |

Experiments 1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASE | no_FF | no_BB | no_BalB | no_NTE | no_S | no_A | no_O | no_CS | ||

| Fossil Fuel | FF | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Biomass Burning | BB | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Balanced Biosphere | BalB | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + |

| Net Terrestrial Exchange | NTE | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + |

| Ship | S | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + |

| Aviation | A | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + |

| Ocean Exchange | O | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | + |

| Chemical Source | CS | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – |

| Time | Sample Size | Simulated Mean (ppm) |

Observed Mean (ppm) |

Simulated Standard Deviation(ppm) | Observed Standard Deviation(ppm) | RMSE (ppm) |

Correlation Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | 6407 | 385.48 | 387.24 | 1.36 | 1.84 | 2.15 | 0.74 |

| Feb | 5456 | 386.03 | 387.63 | 1.59 | 1.92 | 1.98 | 0.80 |

| Mar | 8285 | 386.86 | 388.27 | 1.88 | 2.11 | 1.78 | 0.86 |

| Apr | 8583 | 387.83 | 389.27 | 2.00 | 2.34 | 1.81 | 0.89 |

| May | 9396 | 387.88 | 389.52 | 1.74 | 2.39 | 2.07 | 0.86 |

| Jun | 10609 | 386.94 | 388.90 | 1.32 | 1.74 | 2.39 | 0.62 |

| Jul | 11704 | 385.47 | 387.57 | 2.04 | 2.07 | 2.48 | 0.80 |

| Aug | 14258 | 385.30 | 387.36 | 1.64 | 1.84 | 2.34 | 0.81 |

| Sep | 14166 | 385.44 | 387.51 | 1.16 | 1.33 | 2.33 | 0.64 |

| Oct | 14369 | 385.97 | 388.10 | 0.58 | 1.14 | 2.36 | 0.44 |

| Nov | 13207 | 386.30 | 388.39 | 0.42 | 1.03 | 2.32 | 0.28 |

| Dec | 8796 | 386.70 | 388.78 | 0.91 | 1.40 | 2.35 | 0.64 |

| Yr | 125236 | 386.26 | 388.18 | 1.67 | 1.89 | 2.25 | 0.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).