Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

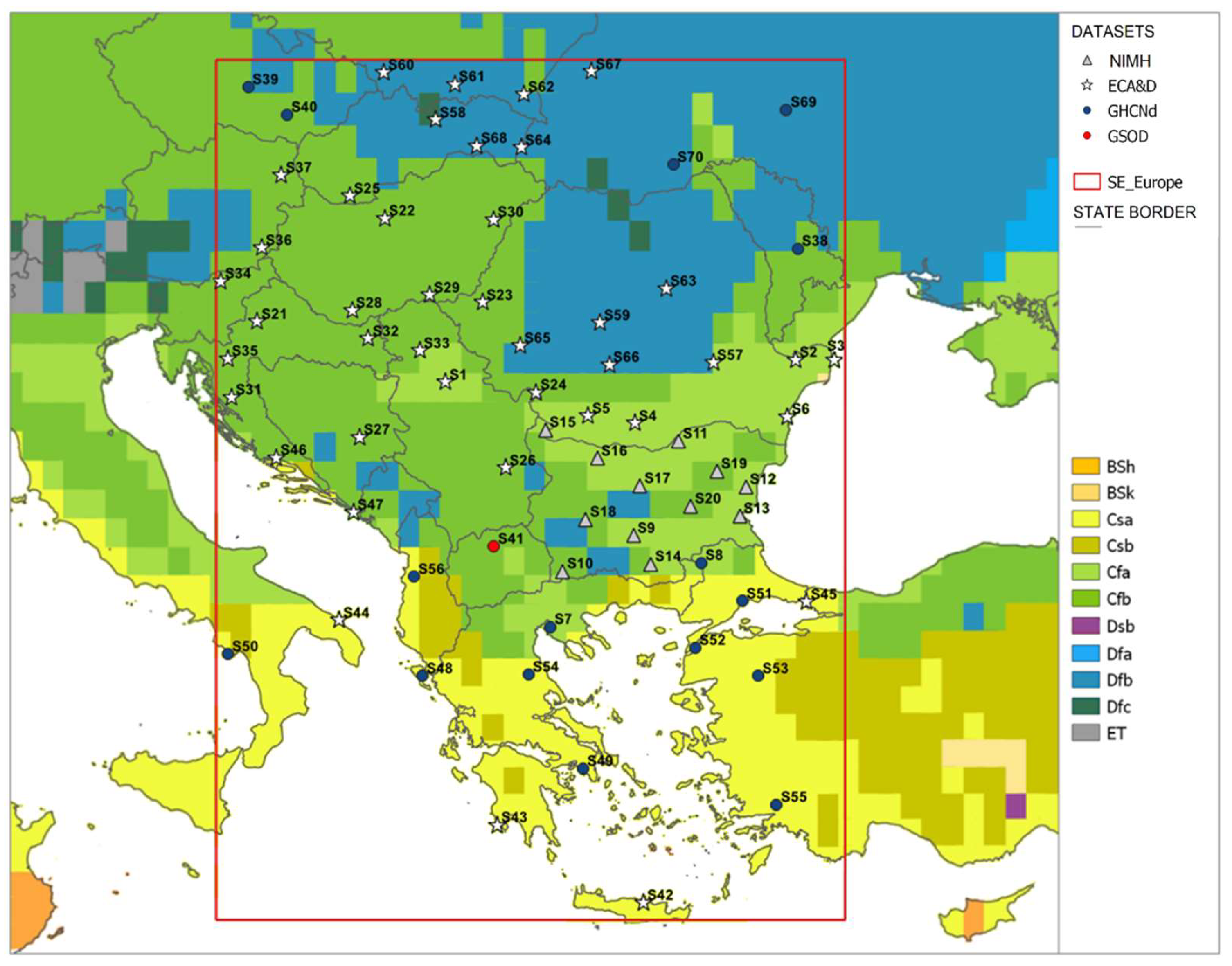

2. Data and Methods

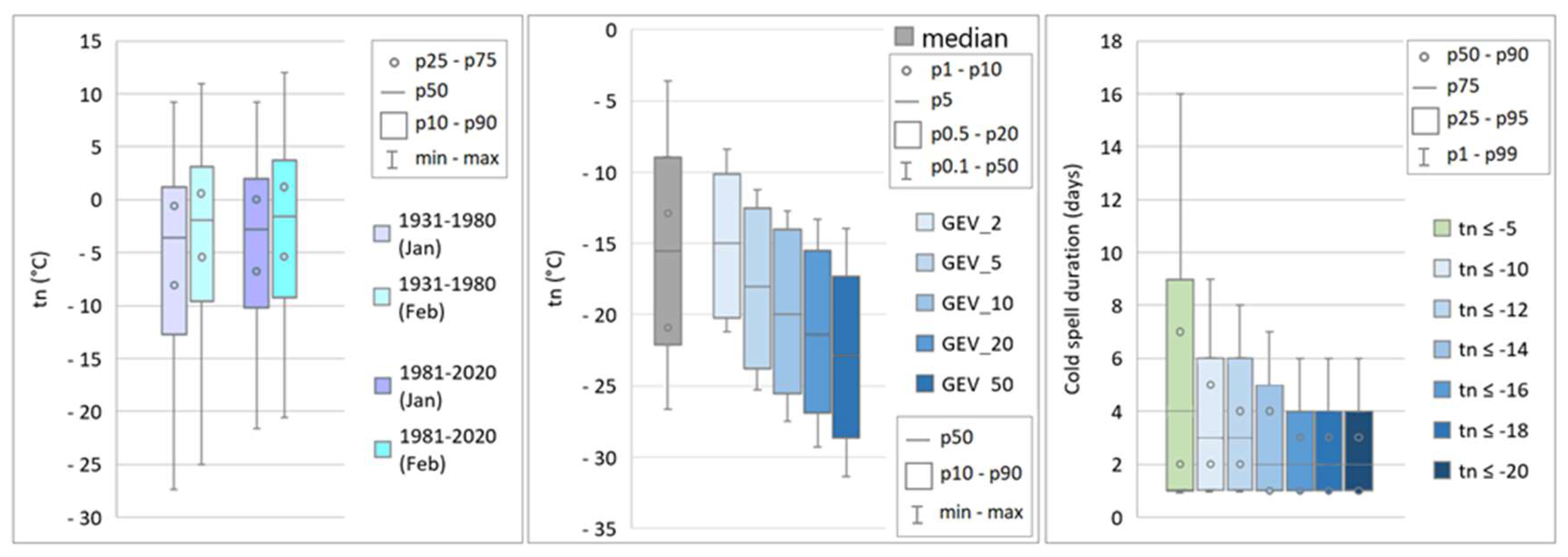

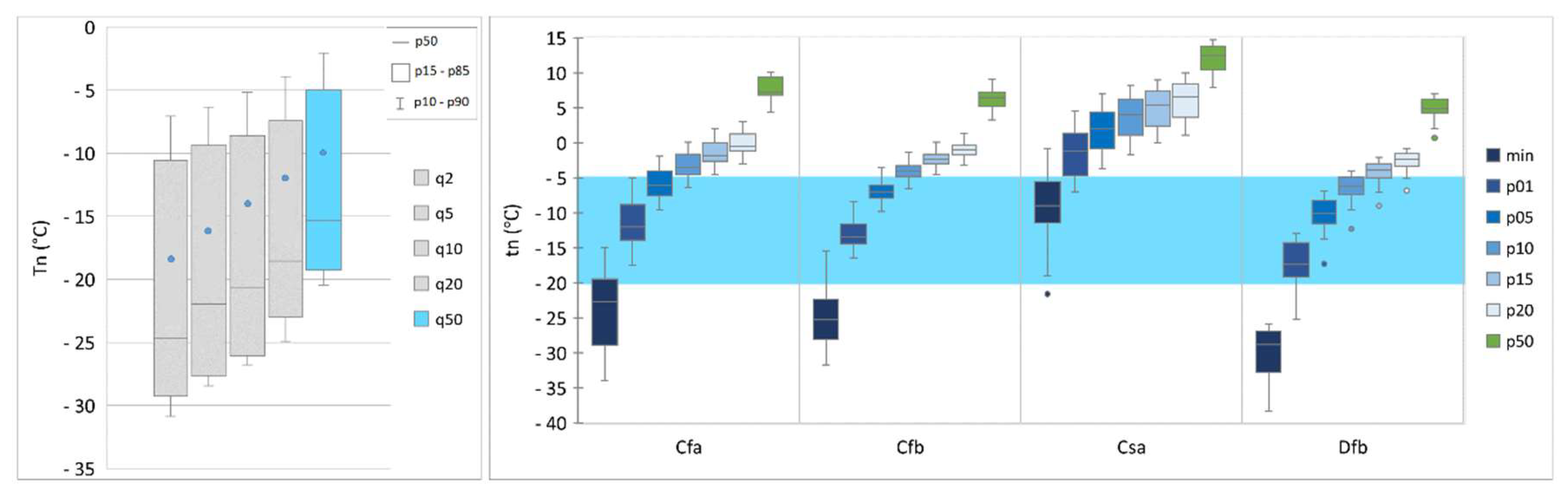

2.1. Climatologically Justified Threshold Indicators

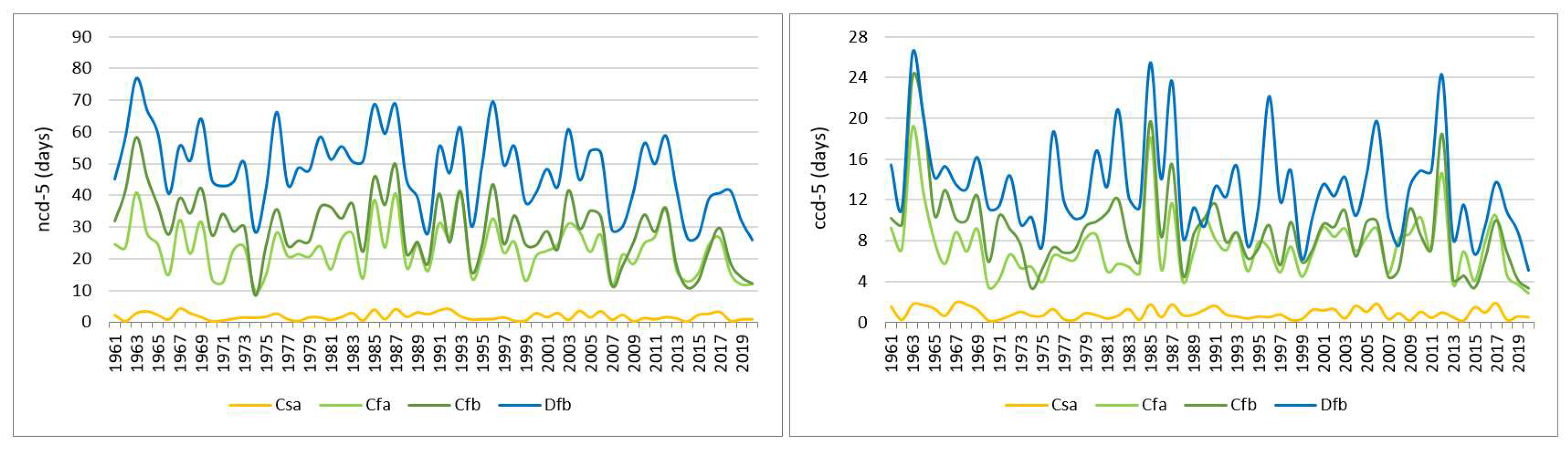

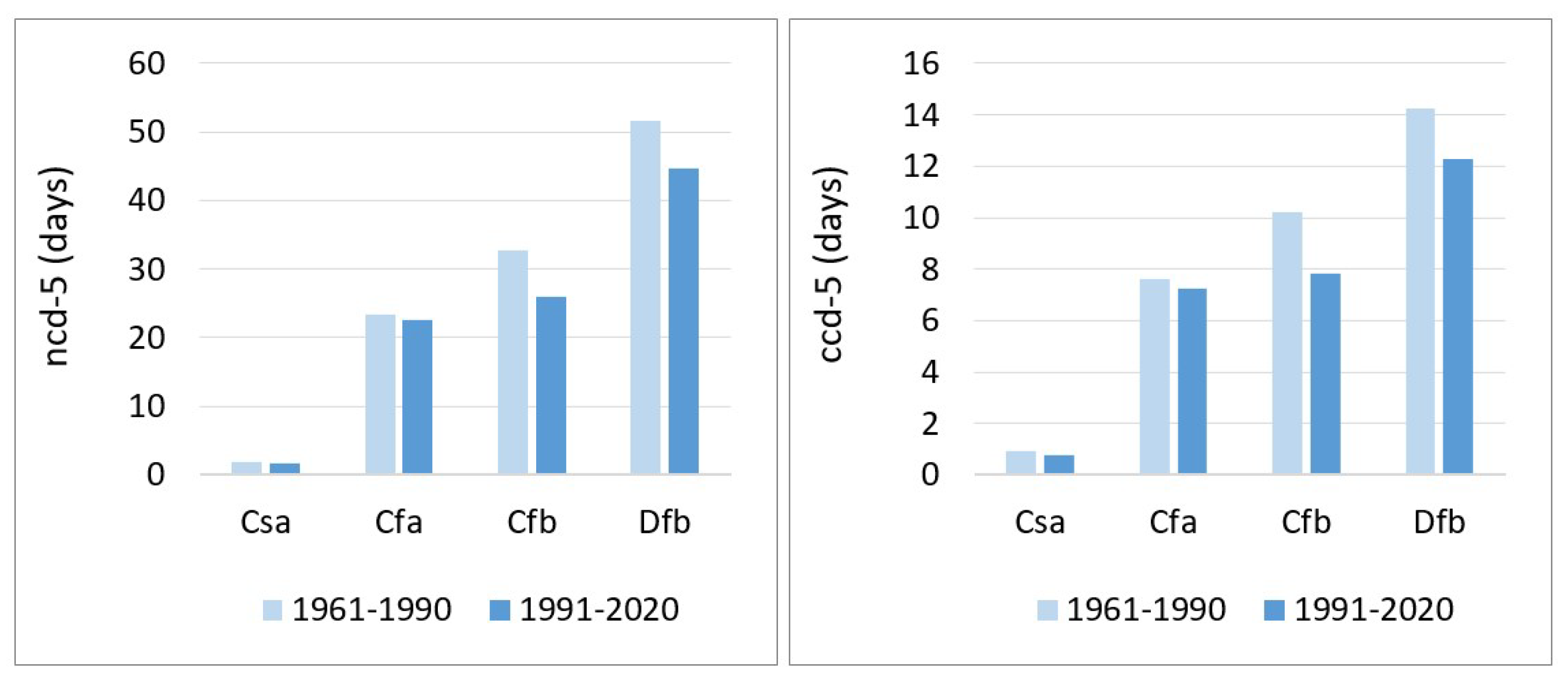

- Annual number of cold days (ncd-5) – i.e., the annual count of days when tn < -5 °C;

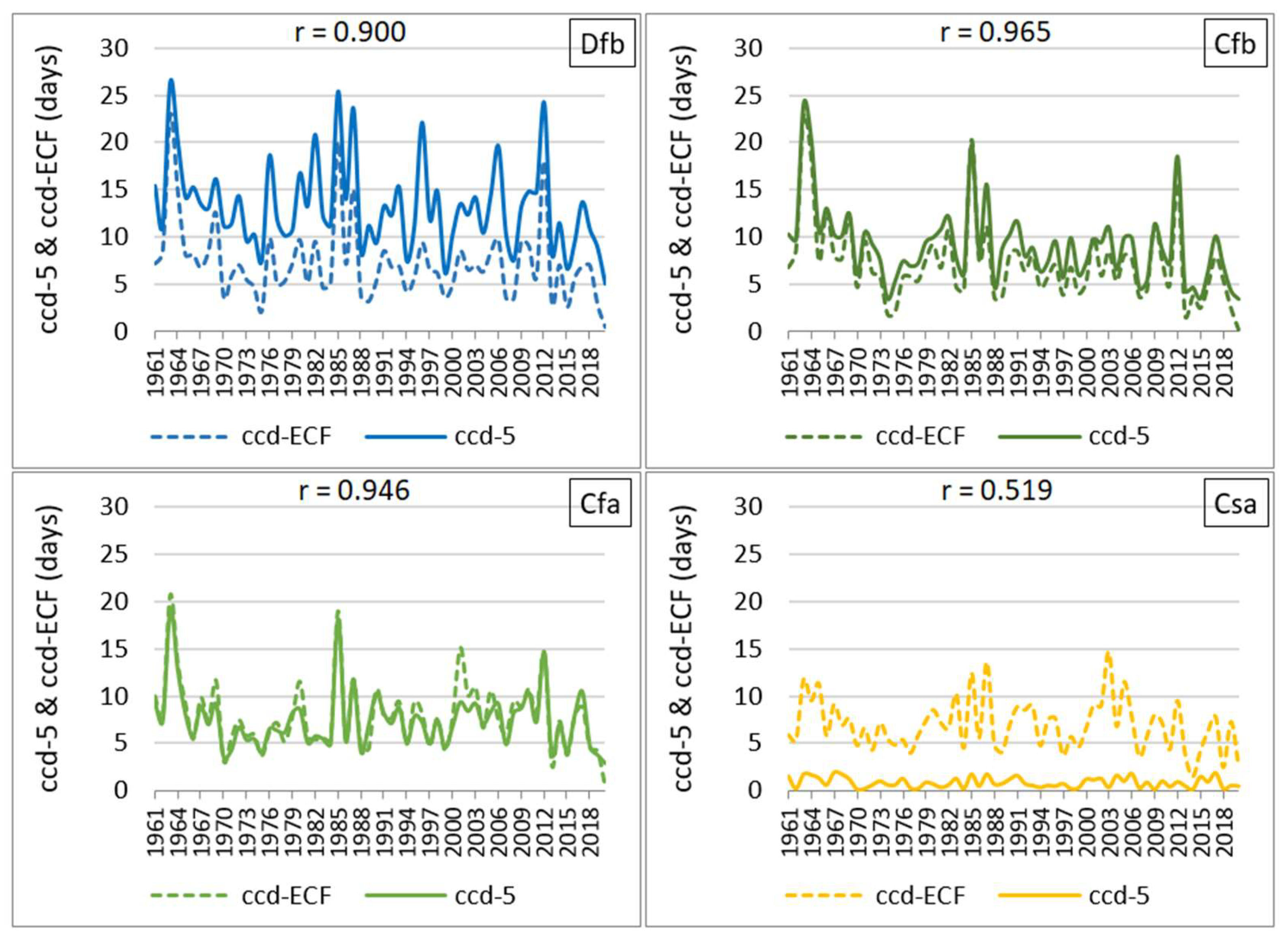

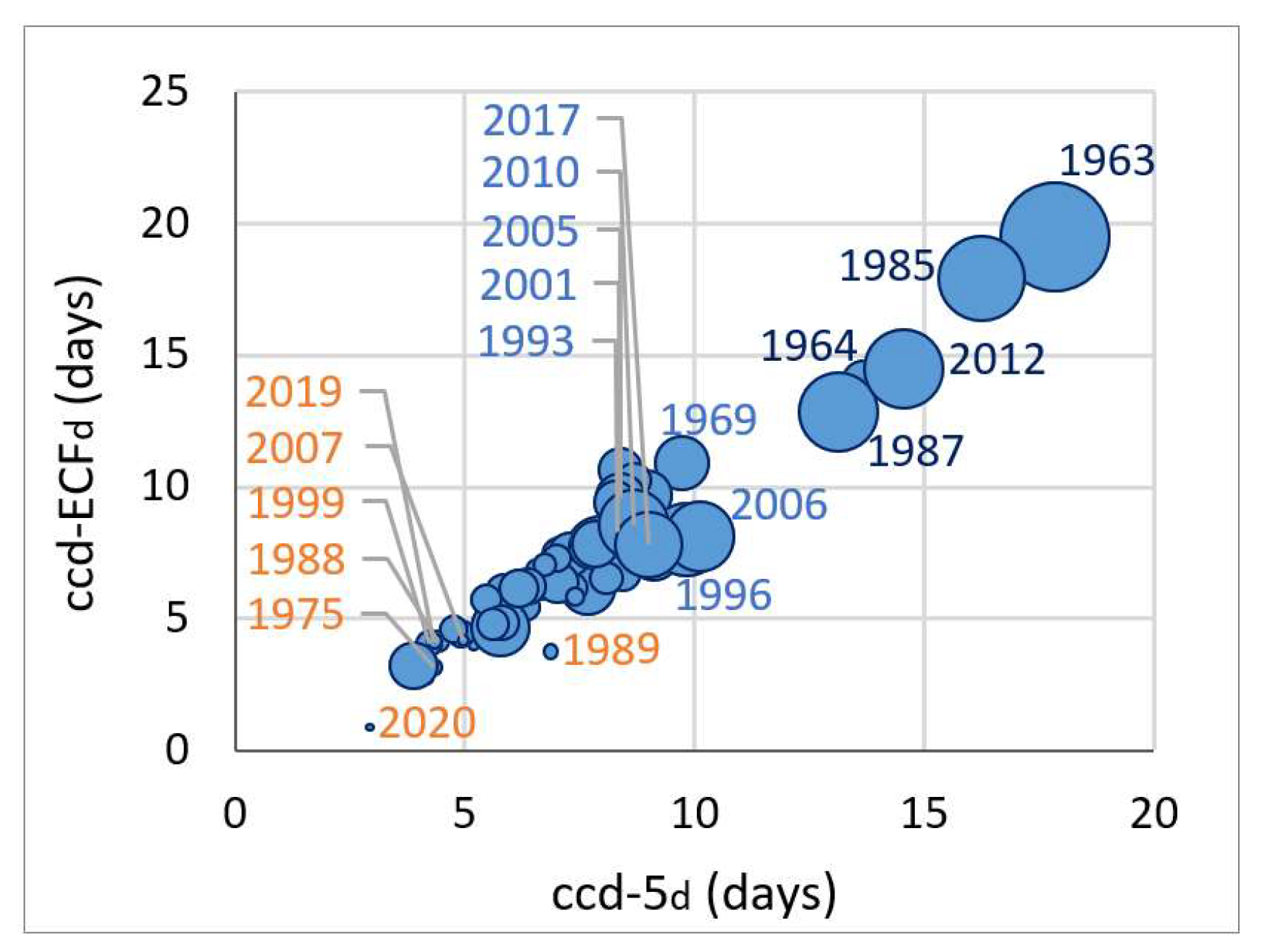

- Maximum number of consecutive cold days (ccd-5) – i.e., the longest continuous calendar period when tn < -5 °C;

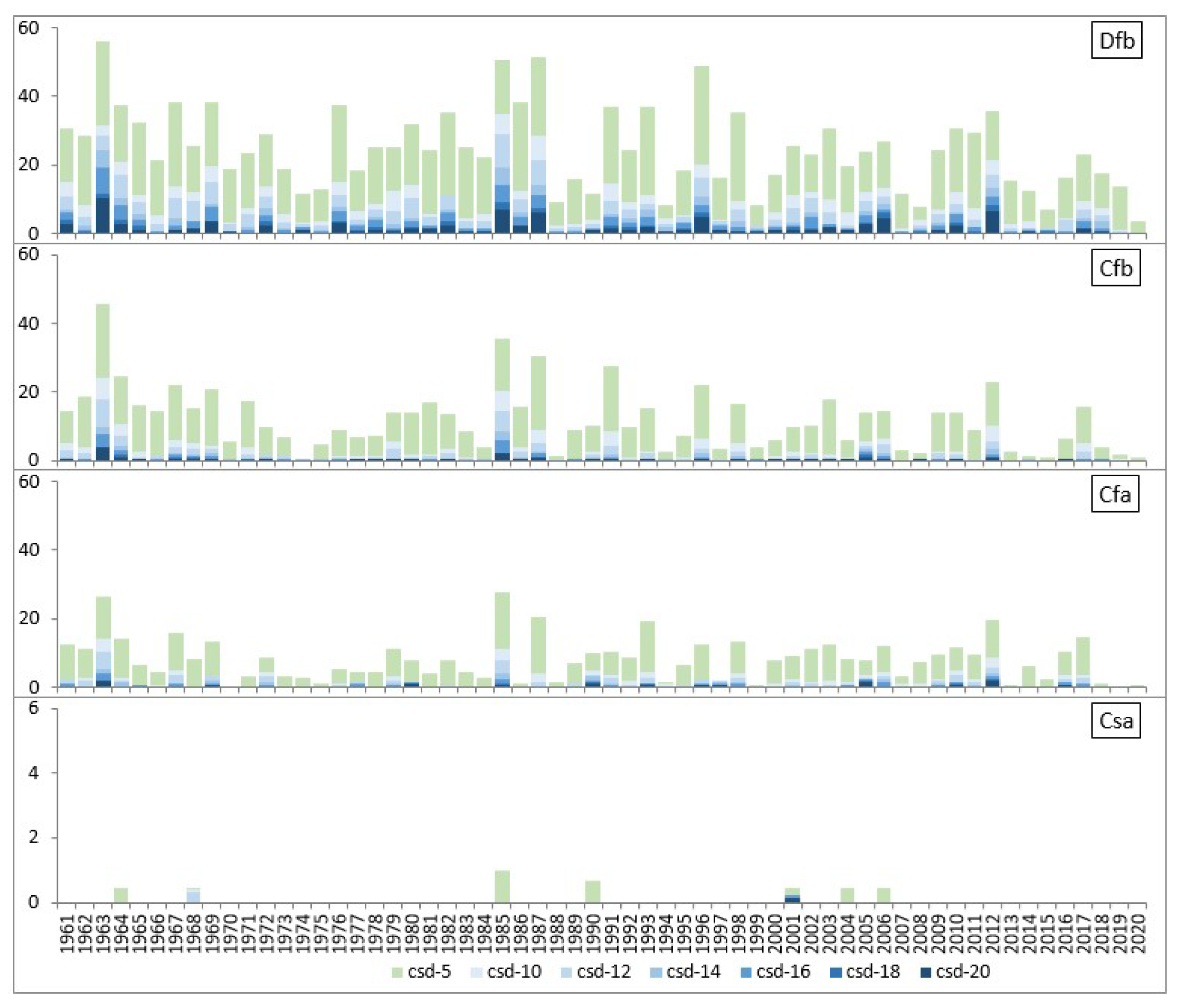

- Cold spells duration at different tn-thresholds (csd-5/-10/-12/-14/-16/-18/-20) – i.e., the annual count of days when tn ≤ -5, -10, -12, -14, -16,- 18 and -20 °C for at least 7, 5, 4, 4, 3, 3 and 2 consecutive days, respectively.

2.2. Excess Cold Factor (ECF)

2.3. Software Products Used in the Research

3. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Csa/Csb | Köppen-Geiger classification: temperate climate with dry, hot/warm summer |

| Cfa/Cfb | Köppen-Geiger classification: temperate climate with no dry hot/warm summer |

| Dfa/Dfb/Dfc | Köppen-Geiger classification: boreal climate with hot/warm/cold summer |

| ECA&D | European Climate Assessment and Dataset project |

| ECE | Extreme cold event |

| ECF | Excess cold factor |

| EHF | Excess heat factor |

| ETCCDI | WMO Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices |

| EURO-CORDEX | Coordinated Downscaling Experiment – European Domain |

| GHCNd | Global Historical Climatology Network daily dataset of the U.S. National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) |

| GSOD | Global Surface Summary of the Day (GSOD) dataset of the U.S. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) |

| NIMH | National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology, Bulgaria |

| SEE | Southeastern Europe |

| WMO | World Meteorological Organization |

Appendix A

| Station ID | Station name | Country code (ISO 3166-1) | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | Altitude (m) | Data source | KGC | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Belgrade (Obs.) | RS | 44.8000 | 20.4667 | 132 | ECA&D | Cfa | urban |

| S2 | Tulcea | RO | 45.1831 | 28.8167 | 4 | ECA&D | Cfa | suburban |

| S3 | Sulina | RO | 45.1667 | 29.7331 | 3 | ECA&D | Cfa | rural |

| S4 | Roșiorii de Vede | RO | 44.1000 | 24.9831 | 102 | ECA&D | Cfa | rural |

| S5 | Craiova | RO | 44.2300 | 23.8700 | 192 | ECA&D | Cfa | rural |

| S6 | Constanța | RO | 44.2200 | 28.6300 | 13 | ECA&D | Cfa | suburban |

| S7 | Thessaloniki Airport | GR | 40.5200 | 22.9700 | 7 | GHCNd | Cfa | airport |

| S8 | Edirne | TR | 41.6700 | 26.5700 | 51 | GHCNd | Cfa | urban |

| S9 | Sadovo | BG | 42.1500 | 24.9500 | 155 | NIMH | Cfa | rural |

| S10 | Sandanski | BG | 41.5200 | 23.2700 | 206 | NIMH | Cfa | suburban |

| S11 | Obraztsov Chiflik | BG | 43.8000 | 26.0331 | 156 | NIMH | Cfa | suburban |

| S12 | Goren Chiflik | BG | 43.0094 | 27.6297 | 29 | NIMH | Cfa | suburban |

| S13 | Burgas | BG | 42.4977 | 27.4827 | 22 | NIMH | Cfa | suburban |

| S14 | Kardzhali | BG | 41.6500 | 25.3700 | 331 | NIMH | Cfa | suburban |

| S15 | Vidin | BG | 43.9942 | 22.8525 | 31 | NIMH | Cfa | suburban |

| S16 | Knezha | BG | 43.5000 | 24.0831 | 116 | NIMH | Cfa | rural |

| S17 | Sevlievo | BG | 43.0256 | 25.1151 | 197 | NIMH | Cfa | suburban |

| S18 | Ihtiman | BG | 42.4381 | 23.8196 | 637 | NIMH | Cfb | urban |

| S19 | Shumen | BG | 43.2796 | 26.9440 | 217 | NIMH | Cfb | suburban |

| S20 | Sliven | BG | 42.6776 | 26.3398 | 259 | NIMH | Cfb | urban |

| S21 | Zagreb- Grič | HR | 45.8167 | 15.9781 | 156 | ECA&D | Cfb | urban |

| S22 | Budapest | HU | 47.5108 | 19.0206 | 153 | ECA&D | Cfb | urban |

| S23 | Arad | RO | 46.1331 | 21.3500 | 116 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S24 | Drobeta-Turnu Severin | RO | 44.6331 | 22.6331 | 77 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S25 | Hurbanovo | SK | 47.8667 | 18.1831 | 115 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S26 | Niš | RS | 43.3331 | 21.9000 | 201 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S27 | Sarajevo | BA | 43.8678 | 18.4228 | 630 | ECA&D | Cfb | urban |

| S28 | Pécs-Pogány | HU | 46.0056 | 18.2328 | 202 | ECA&D | Cfb | airport |

| S29 | Szeged | HU | 46.2558 | 20.0903 | 81 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S30 | Debrecen Airport | HU | 47.4903 | 21.6106 | 107 | ECA&D | Cfb | airport |

| S31 | Gospić | HR | 44.5500 | 15.3667 | 564 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S32 | Osijek | HR | 45.5331 | 18.6331 | 88 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S33 | Novi Sad | RS | 45.3331 | 19.8500 | 84 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S34 | Šmartno pri Slovenj Gradcu | SI | 46.4894 | 15.1108 | 444 | ECA&D | Cfb | rural |

| S35 | Ogulin | HR | 45.2039 | 15.2717 | 326 | ECA&D | Cfb | rural |

| S36 | Fürstenfeld | AT | 47.0308 | 16.0806 | 323 | ECA&D | Cfb | rural |

| S37 | Gross-Enzersdorf | AT | 48.1994 | 16.5589 | 154 | ECA&D | Cfb | suburban |

| S38 | Kisinev | MD | 47.0200 | 28.8700 | 173 | GHCNd | Cfb | urban |

| S39 | Přibyslav | CZ | 49.5828 | 15.7625 | 532 | GHCNd | Cfb | rural |

| S40 | Brno–Tuřany | CZ | 49.1531 | 16.6889 | 241 | GHCNd | Cfb | airport |

| S41 | Skopje International Airport | MK | 41.9616 | 21.6214 | 238 | GSOD | Cfb | airport |

| S42 | Heraklion | GR | 35.3331 | 25.1831 | 39 | ECA&D | Csa | airport |

| S43 | Methoni | GR | 36.8331 | 21.7000 | 51 | ECA&D | Csa | rural |

| S44 | Brindisi | IT | 40.6331 | 17.9331 | 10 | ECA&D | Csa | urban |

| S45 | Istanbul | TR | 40.9667 | 29.0831 | 33 | ECA&D | Csa | urban |

| S46 | Split Marjan | HR | 43.5167 | 16.4331 | 122 | ECA&D | Csa | urban |

| S47 | Dubrovnik | HR | 42.5600 | 18.2700 | 52 | ECA&D | Csa | urban |

| S48 | Corfu | GR | 39.6200 | 19.9200 | 11 | GHCNd | Csa | urban |

| S49 | Hellinikon | GR | 37.9000 | 23.7500 | 10 | GHCNd | Csa | urban |

| S50 | Cape Palinuro | IT | 40.0251 | 15.2805 | 185 | GHCNd | Csa | rural |

| S51 | Tekirdag | TR | 40.9800 | 27.5500 | 3 | GHCNd | Csa | urban |

| S52 | Çanakkale | TR | 40.1400 | 26.4300 | 7 | GHCNd | Csa | airport |

| S53 | Balikesir | TR | 39.6200 | 27.9300 | 104 | GHCNd | Csa | airport |

| S54 | Larissa | GR | 39.6500 | 22.4500 | 73 | GHCNd | Csa | airport |

| S55 | Mugla | TR | 37.2200 | 28.3700 | 646 | GHCNd | Csa | urban |

| S56 | Tirana | AL | 41.3333 | 19.7833 | 38 | GHCNd | Csa | urban |

| S57 | Buzau | RO | 45.1331 | 26.8500 | 97 | ECA&D | Dfb | suburban |

| S58 | Poprad-Tatry | SK | 49.0667 | 20.2331 | 694 | ECA&D | Dfb | airport |

| S59 | Sibiu | RO | 45.8000 | 24.1500 | 444 | ECA&D | Dfb | airport |

| S60 | Bielsko-Biała | PL | 49.8069 | 19.0003 | 396 | ECA&D | Dfb | suburban |

| S61 | Nowy Sącz | PL | 49.6272 | 20.6886 | 292 | ECA&D | Dfb | suburban |

| S62 | Lesko | PL | 49.4664 | 22.3417 | 420 | ECA&D | Dfb | suburban |

| S63 | Miercurea Ciuc | RO | 46.3667 | 25.7331 | 661 | ECA&D | Dfb | rural |

| S64 | Uzhhorod | UA | 48.6331 | 22.2667 | 124 | ECA&D | Dfb | suburban |

| S65 | Caransebeș | RO | 45.4200 | 22.2500 | 241 | ECA&D | Dfb | airport |

| S66 | Râmnicu Vâlcea | RO | 45.1000 | 24.3700 | 239 | ECA&D | Dfb | urban |

| S67 | Lviv | UA | 49.8167 | 23.9500 | 323 | ECA&D | Dfb | urban |

| S68 | Košice | SK | 48.6667 | 21.2167 | 230 | ECA&D | Dfb | airport |

| S69 | Vinnytsia | UA | 49.2300 | 28.6000 | 298 | GHCNd | Dfb | airport |

| S70 | Chernivtsi | UA | 48.3667 | 25.9000 | 246 | GHCNd | Dfb | rural |

| Station ID | Station name | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | Altitude (m) | KGC | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vidin | 43.9942 | 22.8525 | 31 | Cfa | suburban |

| 2 | Lom | 43.8307 | 23.2228 | 36 | Cfa | suburban |

| 3 | Varshets | 43.1972 | 23.2830 | 412 | Cfb | suburban |

| 4 | Vratsa | 43.2312 | 23.5292 | 311 | Cfb | suburban |

| 5 | Knezha | 43.5000 | 24.0831 | 116 | Cfa | rural |

| 6 | Pleven | 43.4073 | 24.6062 | 160 | Cfa | suburban |

| 7 | Sevlievo | 43.0256 | 25.1151 | 197 | Cfa | suburban |

| 8 | Pavlikeni | 43.2341 | 25.3252 | 140 | Cfa | rural |

| 9 | Ruse | 43.8401 | 25.9450 | 46 | Cfa | urban |

| 10 | Obraztsov Chiflik | 43.8000 | 26.0331 | 156 | Cfa | suburban |

| 11 | Suvorovo | 43.3166 | 27.5833 | 173 | Cfb | rural |

| 12 | Shumen | 43.2796 | 26.9440 | 217 | Cfb | suburban |

| 13 | Goren Chiflik | 43.0094 | 27.6297 | 29 | Cfa | suburban |

| 14 | Burgas | 42.4977 | 27.4827 | 22 | Cfa | suburban |

| 15 | Karnobat | 42.6558 | 26.9848 | 190 | Cfb | suburban |

| 16 | Yambol | 42.4751 | 26.5315 | 132 | Cfa | suburban |

| 17 | Sliven | 42.6776 | 26.3398 | 259 | Cfb | urban |

| 18 | Chirpan | 42.2146 | 25.2824 | 162 | Cfa | rural |

| 19 | Kazanlak | 42.6358 | 25.3878 | 397 | Cfb | rural |

| 20 | Hisarya | 42.4857 | 24.7179 | 320 | Cfa | suburban |

| 21 | Velingrad | 42.0120 | 23.9888 | 734 | Cfb | suburban |

| 22 | Sadovo | 42.1500 | 24.9500 | 155 | Cfa | rural |

| 23 | Haskovo | 41.9279 | 25.5414 | 237 | Cfa | urban |

| 24 | Kardzhali | 41.6500 | 25.3700 | 331 | Cfa | suburban |

| 25 | Dzhebel | 41.4978 | 25.2958 | 324 | Csb | suburban |

| 26 | Ivaylovgrad | 41.5286 | 26.1211 | 202 | Csa | suburban |

| 27 | Raykovo | 41.5739 | 24.7135 | 906 | Cfb | urban |

| 28 | Sandanski | 41.5200 | 23.2700 | 206 | Cfa | suburban |

| 29 | Blagoevgrad | 42.0019 | 23.0981 | 424 | Cfa | suburban |

| 30 | Kyustendil | 42.2819 | 22.7231 | 520 | Cfb | suburban |

| 31 | Rila | 42.1253 | 23.1308 | 528 | Cfb | suburban |

| 32 | Ihtiman | 42.4381 | 23.8196 | 637 | Cfb | urban |

| 33 | Tran | 42.8331 | 22.6578 | 747 | Dfb | suburban |

| 34 | Samokov | 42.3392 | 23.5653 | 946 | Dfb | suburban |

| 35 | Iskrets | 42.9817 | 23.2758 | 565 | Cfb | rural |

| 36 | Bozhurishte | 42.7619 | 23.2069 | 562 | Cfb | suburban |

References

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.; et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Technical Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Field, C.B. Changes in ecologically critical terrestrial climate conditions. Science 2013, 341, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: IPCC Special Report on impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels in context of strengthening the response to climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Randalls, S. History of the 2 °C climate target. WIREs Clim. Change 2010, 1, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Staal, A.; Abrams, J.F.; Winkelmann, R.; Sakschewski, B.; Loriani, S.; Fetzer, I.; Cornell, S.E.; Rockström, J.; Lenton, T.M. Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 2022, 377, eabn7950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WMO. State of the global climate 2023. WMO-No. 1347. World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Barnes, E.A. Data-driven predictions of the time remaining until critical global warming thresholds are reached. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2207183120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Russo, S.; Formetta, G.; Ibarreta, D.; et al. Global warming and human impacts of heat and cold extremes in the EU. JRC PESETA IV project – Task 11; European Commission: Joint Research Centre, Publications Office, 2020. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/47878.

- Ebi, K.L.; Capon, A.; Berry, P.; Broderick, C.; de Dear, R.; Havenith, G.; Honda, Y.; Kovats, R.S.; Ma, W.; Malik, A.; Morris, N.B.; Nybo, L.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Vanos, J.; Jay, O. Hot weather and heat extremes: Health risks. Lancet 2021, 398, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryti, N.R.; Guo, Y.; Jaakkola, J.J. Global Association of Cold Spells and Adverse Health Effects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deryugina, T.; Hsiang, S. Does the Environment Still Matter? Daily Temperature and Income in the United States; Technical Report w20750; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. http://www.nber.org/papers/w20750.

- García-León, D.; Casanueva, A.; Standardi, G.; Burgstall, A.; Flouris, A.D.; Nybo, L. Current and projected regional economic impacts of heatwaves in Europe. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añel, J.A.; Fernández-González, M.; Labandeira, X.; López-Otero, X.; De la Torre, L. Impact of Cold Waves and Heat Waves on the Energy Production Sector. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajda, A.; Tuomenvirta, H.; Jokinen, P.; Luomaranta, A.; Makkonen, L.; et al. Probabilities of adverse weather affecting transport in Europe: Climatology and scenarios up to the 2050s; Reports Vol. 2011, No. 9; Finnish Meteorological Institute, 2011. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/28592.

- Teixeira, E.; Fischer, G.; van Velthuizen, H.T.; Walter, C.; Ewert, F. Global hot-spots of heat stress on agricultural crops due to climate change. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 170, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotjahn, R. Weather Extremes That Affect Various Agricultural Commodities. In Extreme Events and Climate Change, 1st ed.; Castillo, F., Wehner, M., Stone, D.A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 21–48. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Huang, J.G.; Hänninen, H.; Berninger, F. Divergent trends in the risk of spring frost damage to trees in Europe with recent warming. Glob Chang Biol. 2019, 25, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oldenborgh, G.J.; Mitchell-Larson, E.; Vecchi, G.A.; De Vries, H.; Vautard, R.; Otto, F. Cold waves are getting milder in the northern midlatitudes. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 114004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vries, H.; Haarsma, R.J.; Hazeleger, W. Western European cold spells in current and future climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forzieri, G.; Cescatti, A.; de Silva, F.B.; Feyen, L. Increasing risk over time of weather-related hazards to the European population: A data-driven prognostic study. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e200–e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, N.; Jones, G.; Stott, P. Dramatically increasing chance of extremely hot summers since the 2003 European heatwave. Nature Clim Change 2015, 5, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO (2021). Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water Extremes (1970–2021); WMO-No. 1267; WMO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Schär, C.; Vidale, P.L.; Lüthi, D.; Frei, C.; Häberli, C.; Liniger, M.A.; Appenzeller, C. The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature 2004, 427, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donat, M.G.; Alexander, L.V. The shifting probability distribution of global daytime and night-time temperatures, Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, L14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackport, R.; Fyfe, J.C. Amplified warming of North American cold extremes linked to human-induced changes in temperature variability. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattiaux, J.; Vautard, R.; Cassou, C.; Yiou, P.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Codron, F. Winter 2010 in Europe: A cold extreme in a warming climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L20704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planchon, O.; Quénol, H.; Irimia, L.; Patriche, C. European cold wave during February 2012 and impacts in wine growing regions of Moldavia (Romania). Theor Appl Climatol 2015, 120, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtaş, M. The anomalously cold January 2017 in the southeastern Europe in a warming climate. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 6018–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de'Donato, F.K.; Leone, M.; Noce, D.; Davoli, M.; Michelozzi, P. The impact of the February 2012 cold spell on health in Italy using surveillance data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippel, S.; Barnes, C.; Cadiou, C.; Fischer, E.; Kew, S.; Kretschmer, M.; Philip, S.; Shepherd, T.G.; Singh, J.; Vautard, R.; Yiou, P. Could an extremely cold central European winter such as 1963 happen again despite climate change? Weather Clim. Dynam. 2024, 5, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, J.; López-Bueno, J.A.; Sáez, M.; Mirón, I.J.; Luna, M.Y.; Sanchez, M.G.; Carmona, R.; Barceló, M.A.; Linares, C. Will there be cold-related mortality in Spain over the 2021–2050 and 2051–2100 time horizons despite the increase in temperatures as a consequence of climate change? Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Sera, F.; Guo, Y.; Chung, Y.; Arbuthnott, K.; Tong, S.; Tobias, A.; Lavigne, E.; et al. A multi-country analysis on potential adaptive mechanisms to cold and heat in a changing climate. Environ Int. 2018, 111, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkova, E.P.; Vink, J.K.; Horton, R.M.; Gasparrini, A.; Bader, D.A.; Francis, J.D.; Kinney, P.L. Towards more comprehensive projections of urban heat-related mortality: Estimates for New York City under multiple population, adaptation, and climate scenarios. Environ Health Perspect 2017, 125, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pintor, M.P. The future of the temperature-mortality relationship. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e636–e637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, J.A.L.; Diaz, J.; Follos, F.; Vellón, J.M.; Navas, M.A.; Culqui, D.; Luna, M.Y.; Sanchez Martinez, G.; Linares, C. Evolution of the threshold temperature definition of a heat wave vs. Evolution of the minimum mortality temperature: A case study in Spain during the 1983–2018 period. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Haunschild, R.; Bornmann, L. Heat waves: A hot topic in climate change research. Theor Appl Climatol. 2021, 146, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Guidelines on the Definition and Characterization of Extreme Weather and Climate Events; WMO-No. 1310; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Perkins, S.E. A review on the scientific understanding of heatwaves—Their measurement, driving mechanisms, and changes at the global scale. Atmos. Res. 2015, 164, 242–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.M.; Mankin, J.S.; Lesk, C.; Coffel, E.; Raymond, C. A review of recent advances in research on extreme heat events. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2016, 2, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.R.; Bessemoulin, P.; Ebi, K.L.; Menne, B. Heatwaves and health: Guidance on warning-system development. World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Casanueva, A.; Burgstall, A.; Kotlarski, S.; Messeri, A.; Morabito, M.; Flouris, A.D.; Nybo, L.; Spirig, C.; Schwierz, C. Overview of Existing Heat-Health Warning Systems in Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Alexander, L.; Hegerl, G.C.; Jones, P.; Tank, A.K.; Peterson, T.C.; Trewin, B.; Zwiers, F.W. Indices for monitoring changes in extremes based on daily temperature and precipitation data. WIREs Clim. Change 2011, 2, 851–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.; Alexander, L. On the measurement of heat waves. J. Clim. 2013, 26, 4500–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, L.V.; Zhang, X.; Peterson, T.C.; Caesar, J.; Gleason, B.; Klein Tank, A.M.G.; et al. Global observed changes in daily climate extremes of temperature and precipitation, J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, D05109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, J.; Fawcett, R. Defining Heatwaves: Heatwave defined as a heat-impact event servicing all community and business sectors in Australia. CAWCR Technical Report, No. 060. CSIRO and Australian Bureau of Meteorology, 2013.

- Robinson, P.J. On the Definition of a Heat Wave. J. Appl. Meteorol. 2001, 40, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, F.N.; Fink, A.H.; Bissolli, P.; Pinto, J.G. Towards a more comprehensive assessment of the intensity of historical European heat waves (1979–2019). Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2022, 23, e1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, A.; Laschewski, G.; Muthers, S. The Heat Health Warning System in Germany – Application and Warnings for 2005 to 2019. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, M.; Crisci, A.; Messeri, A.; Messeri, G.; Betti, G.; Orlandini, S.; Raschi, A.; Maracchi, G. Increasing Heatwave Hazards in the Southeastern European Union Capitals. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xoplaki, E.; Trigo, R.; García-Herrera, R.; Barriopedro, D.; D’andrea, F.; et al. Chapter 6: Large-scale atmospheric circulation driving extreme climate events in the Mediterranean and related impacts. In The Climate of the Mediterranean Region; Lionello, P. (ed.), Elsevier, 2012, pp. 347–417.

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Pal, J.S.; Giorgi, F.; Gao, X. Heat stress intensification in the Mediterranean climate change hotspot, Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L11706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tringa, E.; Tolika, K.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Kostopoulou, E. A Climatological and Synoptic Analysis of Winter Cold Spells over the Balkan Peninsula. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulou, E. Analysis of the January 2017 Cold Spell in Greece and Its Implications on Human Health. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faranda, D.; Bourdin, S.; Ginesta, M.; Krouma, M.; Noyelle, R.; Pons, F.; Yiou, P.; Messori, G. A climate-change attribution retrospective of some impactful weather extremes of 2021, Weather Clim. Dynam. 2022, 3, 1311–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kysely, J.; Pokorna, L.; Kyncl, J.; et al. Excess cardiovascular mortality associated with cold spells in the Czech Republic. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Poso, A.; Lorenzo, N.; Martí, A.; Royé, D. Cold wave intensity on the Iberian Peninsula: Future climate projections. Atmos. Res. 2023, 295, 107011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piticar, A.; Croitoru, A.-E.; Ciupertea, F.-A.; Harpa, G.-V. Recent changes in heat waves and cold waves detected based on excess heat factor and excess cold factor in Romania. Int. J. Climatol 2018, 38, 1777–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcheva, K.; Bocheva, L.; Chervenkov, H. Spatio-Temporal Variation of Extreme Heat Events in Southeastern Europe. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Marini, K. Climate and Environmental Change in the Mediterranean Basin – Current Situation and Risks for the Future. MedECC: First Mediterranean Assessment Report; UNEP/MAP: Marseille, France, 2020.

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Abrantes, F.; Congedi, L.; Dulac, F.; Gacic, M.; et al. Introduction: Mediterranean Climate – Background Information; In The Climate of the Mediterranean Region; Lionello, P. (ed.); Elsevier, 2012; pp. xxxv–xc.

- Klein Tank, A.M.; Wijngaard, J.B.; Können, G.P.; Böhm, R.; Demarée, G.R.; Gocheva, A.; Mileta, M.; et al. Daily dataset of 20th-century surface air temperature and precipitation series for the European Climate Assessment. Int. J. Climatol. 2002, 22, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menne, M.J.; Durre, I.; Vose, R.S.; Gleason, B.E.; Houston, T.G. An overview of the Global Historical Climatology Network-Daily Database. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2012, 29, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.H.; Hengl, T.; Nelson, A. GSODR: Global Summary Daily Weather Data in R. J. Open Source Softw 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sippel, S.; Fischer, E.M.; Scherrer, S.C.; Meinshausen, N.; Knutti, R. Late 1980s abrupt cold season temperature change in Europe consistent with circulation variability and long-term warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 15, 094056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, V.; Schneider, M.; Koleva, E.; Moisselin, J.-M. Climate variability and change in Bulgaria during the 20th century, Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2004, 79, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, Y.; Duluc, C.-M.; Rebour, V. Temperature Extremes: Estimation of Non-Stationary Return Levels and Associated Uncertainties. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcheva, K. Cold waves on the territory of Bulgaria in the period 1952-2011. Bul. J. Meteo & Hydro 2017, 22, 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods. J. Inst. Actuar. 1949, 75, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlert, T. Package “Trend”: Non-Parametric Trend Tests and Change-Point Detection; R Package, 26, 2016. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/trend/trend.pdf.

- Oliveira, A.; Lopes, A.; Soares, A. Excess heat factor climatology, trends, and exposure across European functional urban areas. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2022, 36, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalley, B.D.; Spicer, T.; Jian, L.; Xiao, J.; Nairn, J.; Robertson, A.; Weeramanthri, T. Responding to heatwave intensity: Excess Heat Factor is a superior predictor of health service utilisation and a trigger for heatwave plans. Aust N Z J Public Health 2015, 39, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Poso, A.; Lorenzo, N.; Royé, D. Spatio-temporal evolution of heat waves severity and expansion across the Iberian Peninsula and Balearic islands. Environ Res. 2023, 217, 114864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanaki, E.; Giannaros, C.; Kotroni, V.; Lagouvardos, K.; Papavasileiou, G. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Heatwaves Characteristics in Greece from 1950 to 2020. Climate 2023, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.-J.; Sun, Y.; Hu, T.; Dong, S.-Y. Changes of extreme cold events in China over the last century based on reanalysis data. Climate Change Research 2023, 19, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espín-Sánchez, D.; Conesa-García, C. Spatio-temporal changes in the heatwaves and coldwaves in Spain (1950-2018): Influence of the East Atlantic pattern. Geographica Pannonica 2021, 25, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Zanobetti, A.; Schwartz, J.D. Estimating and projecting the effect of cold waves on mortality in 209 US cities. Environ Int. 2016, 94, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, S.C.; Lee, C.C. Temporal trends in absolute and relative extreme temperature events across North America. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2018, 123, 11–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, J.; Ostendorf, B.; Bi, P. Performance of Excess Heat Factor Severity as a Global Heatwave Health Impact Index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Technical Report; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. https://www.R-project.org/.

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; Technical Report; RStudio, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. http://www.rstudio.com/.

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System; Technical Report; Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2023. http://www.qgis.org/.

- Twardosz, R.; Walanus, A.; Guzik, I. Warming in Europe: Recent Trends in Annual and Seasonal temperatures. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2021, 178, 4021–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubkov, A.S.; Voskresenskaya, E.N.; Marchukova, O.V.; Evstigneev, V.P. European temperature anomalies in the cold period associated with ENSO events. IOP Conference Series. Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 606 (1); Bristol. [CrossRef]

- WMO. The Global Climate 2001-2010: A Decade of Climate Extremes; Summary Report; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Cohen, J.; Agel, L.; Barlow, M.; Entekhabi, D. No detectable trend in mid-latitude cold extremes during the recent period of Arctic amplification. Commun Earth Environ 2023, 4, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buric, D.; Doderovic, M. Trend of Percentile Climate Indices in Montenegro in the Period 1961–2020. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.F.; Xiao, Y.C.; Feng, Y.F.; Niu, L.Y.; Tan, X.; Sun, J.C.; Leng, Y.Q.; Li, W.Y.; Wang, W.Z.; Wang, Y.K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cold exposure and cardiovascular disease outcomes. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023, 10, 1084611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q. Temperature thresholds and crop production: A review. Clim. Change 2011, 109, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añel, J.A.; Pérez-Souto, C.; Bayo-Besteiro, S.; Prieto-Godino, L.; Bloomfield, H.; Troccoli, A.; Torre, L. Extreme Weather Events and the Energy Sector in 2021. Weather Clim. Soc. 2024, 16, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcheva, K.; Pophristov, V.; Marinova, T.; Trifonova, L. Complex approach for classification of winter severity in Bulgaria. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2075, 120011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brázdil, R.; Zahradníček, P.; Chromá, K.; Dobrovolný, P.; Dolák, L.; Řehoř, J.; Zahradník, P. Severity of winters in the Czech Republic during the 1961–2021 period and related environmental impacts and responses. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 43, 2820–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cfa | Cfb | Csa | Dfb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ta | +0.29/ +0.43 (S1) | 100% | +0.39/ +0.55 (S18) | 100% | +0.24/ +0.37 (S45) | 100% | +0.34/ +0.44 (S60) | 100% |

| Tmn | +0.26/ +0.46 (S1) | 82% | +0.34/ +0.58 (S18) | 100% | +0.23/ +0.47 (S45) | 87% | +0.32/ +0.41 (S60) | 93% |

| Tn | +0.54/ +0.54 (S7) | 6% | +0.76/ +1.09 (S37) | 50% | +0.28/ +0.28 (S48) | 7% | +0.79/ +1.00 (S60) | 36% |

| Cfa | Cfb | Csa | Dfb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ncd-5 | -1.5/ -2.3 (S5) | 18% | -3.1/ -4.5 (S34 and S36) | 88% | -3.1/ -4.1 (S60 and S70) | 86% | ||

| ccd-5 | -0.4/ -0.7 (S1) | 18% | -1.0/ -1.3 (S34 and S40) | 67% | -0.8/ -0.9 (S67 and S68) | 43% | ||

| csd-5 | -1.7/ -3.6 (S31 and S39) | 71% | -2.7/ -4.0 (S67) | 79% | ||||

| csd-10 | -0.3/ -0.7 (S34) | 21% | -1.3/ -1.8 (S67 and S69) | 43% | ||||

| csd-12 | -0.8/ -1.6 (S69) | 36% | ||||||

| csd-14 | -0.3/ -0.8 (S69) | 21% | ||||||

| csd-16 | -0.2/ -0.3 (S69) | 14% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).