1. Introduction

Corpus callosum (CC) is the biggest commissure of the human brain. It consists of circa 200 million fibers forming white matter tracts, which are responsible for communication between cerebral hemispheres. It permits the interaction, coordination and specialization of several brain functions. Anatomically CC consists of four main parts - the rostrum, the genu, the body, and the splenium. More detailed division distinguishes seven subareas - the rostrum, genu, rostral body, anterior midbody, posterior midbody, isthmus and splenium. CC originates about the eighth week of gestation and its development is strictly connected with growth of corresponding brain parts. The myelination undergoes during childhood and adolescence [

1].

Epidemiology

First reports of transient lesions with diffusion restriction were published in the 1990s. They were called: mild encephalitis/encephalopathy with reversible splenial lesion (MERS), reversible splenial lesion syndrome (RESLES), transient splenial lesions (TSL) and finally cytotoxic lesions of the Corpus Callosum (CC) - (CLOCCs). Incidence of CLOCCs is unknown but it is deemed to be a rare disorder [

2].

Etiology and Pathophysiology

CLOCCs are secondary afflictions of the CC and predominantly they are reversible. Etiological factors can be divided into infection -, trauma- , metabolic – and other (drug/ toxin; vascular) - associated causes (

Table 1). The most common ones are infection-associated causes as well as in adult and pediatric patients. Infection causes group includes viral, bacterial pathogens; plasmodia ones are more sporadic. Principally infection causes predominate in children. In adults there is observed second group of entities associated with CLOCCs connected with drugs and toxins [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Problems with identification of entities associated with CLOCCs occur in many patients (in adult and pediatric groups).

Pathophysiology of CC lesions is hypothesized to be result of cytokinopathy created by the cascade of the inflammatory process, both in the humoral and cellular mechanisms. It increases the concentration of glutamate in the extracellular fluid; the high number of glutamate receptors in the corpus callosum explains the particular sensitivity of this structure to this disorder and the penetration of water into astrocytes and neurons. It leads to cytotoxic edema. Different etiologies probably converge on the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, resulting in a common molecular pathway with the same tissue injury and radiological findings, despite a variety of triggering clinical conditions [

7].

Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis and Treatment

The clinical symptoms of patients with transient splenial lesions are nonspecific and depend on the underlying disease. Patients with CLOCCs suffer from general and neurological symptoms like impairment of consciousness, seizures, ataxia, paresthesia, headache. Motor deterioration, slurred speech, neck stiffness, coma, tremor, ataxia, somnolence, dysarthria, visual disturbance, and dizziness have also been reported. Nonspecific clinical features include fever and vomiting. Furthermore, CLOCCs - like diagnostic findings can be seen in MRI examinations of patients without any clinical problems [

2,

8].

Diagnosis is based on the results of neuroimaging MRI. Pathognomonic signs manifest usually as ovoid, homogeneous, non-hemorrhagic lesions detected in the middle part of the splenium. Extra-splenial callosal lesions are seen essentially in pediatric group. Extracallosal involvement is described in some patients; it may predict irreversible character of injury. Lesions are usually hyperintense on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences, hypointense or isointense on T1-weighted images, present restricted diffusion and do not show contrast enhancement. [

2,

9] .

Differential diagnostics involve among others ischemic lesions, neuroinflammatory disease as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) or multiple sclerosis (MS), neoplasms and rare metabolic encephalopathies. [

2,

10].

Outcomes and Follow-up

In most patients within a month there is a complete regression of changes in the corpus callosum [

11]. MRI follow-up is usually performed to several months after diagnosing. Patients with persisted lesions constitute fractional part [

2]. Data from publications quote normal neurodevelopment after recovering [

6].

The authors present a case of a 15-year-old girl, so far without any health burden, who suffered from severe CLOCCs, with the etiology of Ebstein-Barr virus infection. According to the authors' knowledge, few cases of CLOCCs with such etiology over many years has been described in the literature so far.

2. Case Report

15- years- old girl was born from an unburdened pregnancy and childbirth, showing the proper course of psychomotor development and achieving good results in labor. The first symptoms of disease were nausea, vomiting, fever, cough and the child reported imbalances and vision disturbances. For this reason, in the conditions of a regional hospital, computed tomography of the head with contrast was performed, obtaining a correct result. However, laboratory tests revealed hypertransaminasemia, and abdominal ultrasound - hepatosplenomegaly. This was the reason for the transfer of the child to the gastroenterology ward of the tertiary hospital. During less than a day's stay in the gastroenterology department, the child's condition deteriorated significantly - rapidly increasing severity disturbances and seizure with respiratory failure appeared (Glasgow score 7), which was an indication for the child’s transfer to the ICU. Initial brain MRI did not show any changes in corpus callosum which was done in the first day of neurological symptoms. The most significant deviations in laboratory tests were: hypetransaminazemia, elevated concentration of C-reactive protein, increase of D-Dimers and prolongation of aPTT, and in the blood count, leukocytosis with predominance of lymphocytes and significant presentation of monocytes. In the cerebrospinal fluid image, slight lymphocytic pleocytosis and increased protein concentration; the culture was negative, antigens typical for meningitis were not detected. Positive Monotest and high titre of antibodies to EBV in the blood serum which together with rashes on the skin of the whole body that appeared on the 3rd day of stay at the ICU, organomegaly and the results of laboratory tests determined the diagnosis of mononucleosis.

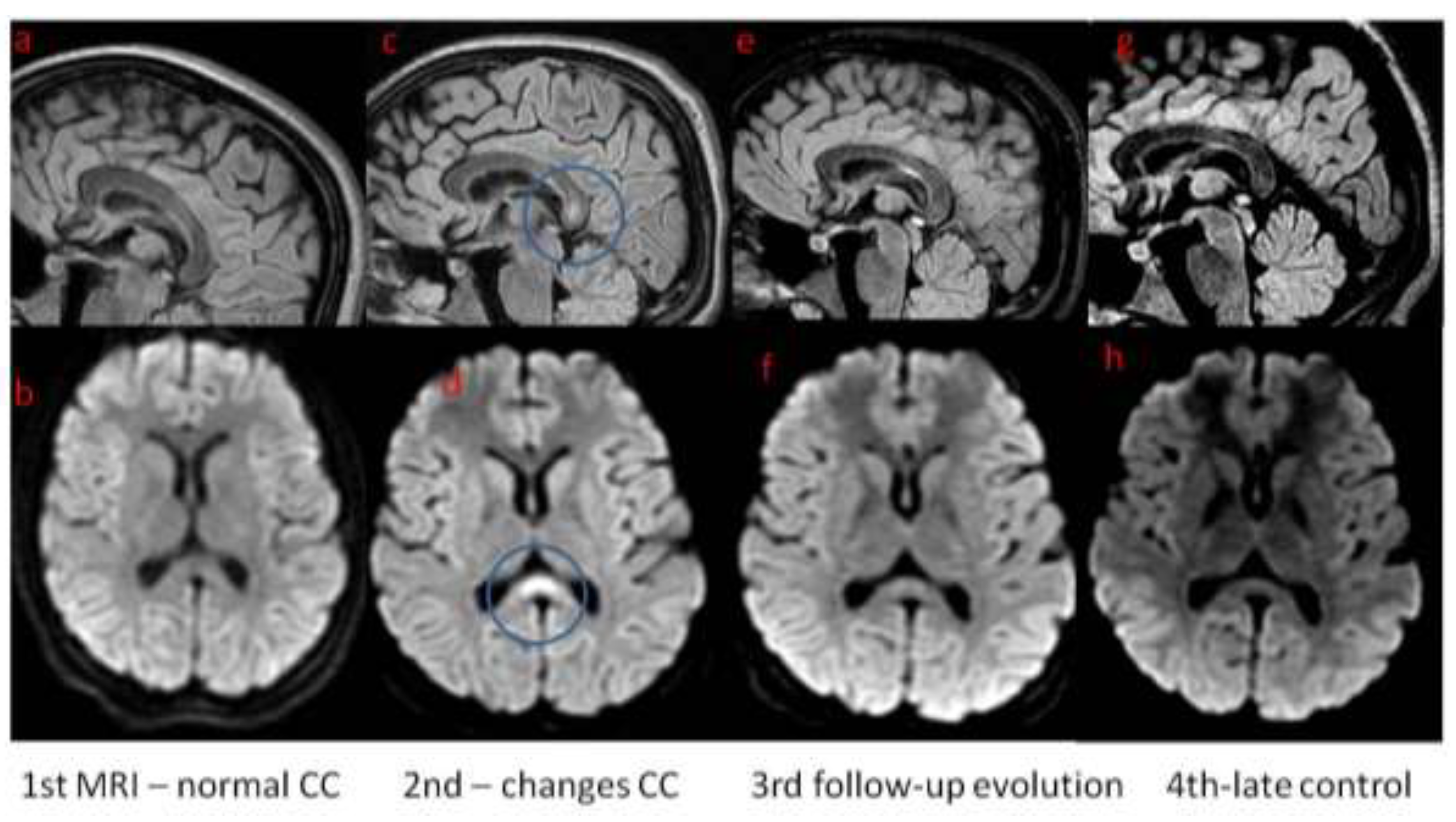

In ICU girl was treated with wide spectrum antibiotics, acyclovir, osmotic diuretics and sedation medicines. She was intubated and mechanical ventilation was initiated. After 8 days from admission the general condition of the child, in terms of the recouping of consciousness and the achievement of full respiratory and circulatory capacity, quickly improved, so the child continued treatment in the neurology department. Control MRI was performed 11 days after onset of the neurological symptoms; it showed abnormal signal in the corpus callosum meeting the CLOCC criteria. Follow-up MRI was performed within a month of the first examination, showing partial regression of corpus callosum changes. One month after the onset of symptoms, the child presents no changes in the neurological examination. Laboratory tests were completely normalized, as was the ultrasound image of the abdominal organs. In the eeg recording carried out two weeks after the onset of status epilepticus and monitored one month after the onset, symptomatic absence of seizure activity. In the absence of further seizure incidents, no antiepileptic drugs were used, only a thiopental coma was necessary during the stay at the ICU. After 11 days in neurology department girl was discharged from hospital. 3 months later she was admitted to hospital in order to perform control examinations. Child was in good condition, without any neurological abnormalities. MRI was performed and showed further regression, but not complete resolution of corpus callosum changes (

Figure 1.).

3. Discussion

Ebstein-Barr virus (EBV) belongs to the family of Herpesviridae [

3].This virus usually causes infections called mononucleosis, which are usually mild and self-limited [

11] .Neurological complications of the EBV infection, most typically, they concern the situation of acute infection with this virus, however, there are also reports of reactivation of the infection after a different length of time after acute illness. About 1-5% of patients who develop an acute EBV infection will develop neurological symptoms, include meningitis and / or encephalitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, cerebellitis, and cranial paralysis [

3,

12]. A 10-year observational study of EBV encephalitis by Doja et al. shows a wide spectrum of the course and clinical symptoms of the disease [

13]. Two of the 21 patients included in the follow-up were in a life-threatening condition and died. Caruso et col. describe 5 cases of children with permanent, severe neurological defects [

14].

The reason why the corpus callosum is particularly vulnarable to damage of various (metabolic, infectious, inflammatory, traumatic) etiologies is due to the large number of glutamate receptors [

5,

16]. Regardless of the causative factor (infection, trauma, metabolic factors), macrophages and monocytes are activated and the secretion of interleukins 1 and 6 increases, which in turn causes T cells induction. Globally it leads to damage of blood-brain barrier and an increase in the secretion of tumor necrosis factor by endothelial cells. Astrocytes are cells that especially produce a lot of glutamate and are responsible for blocking their reuptake, and they are stimulated by interleukin 1; as a result, the concentration of glutamate in the extracellular space increases even a hundredfold. Furthermore microglia take part in this process and can start demyelination. This situation is called cytokinopathy, and the high concentration of susceptible receptors in the corpus callosum is the cause of the cytotoxic onset of edema in this structure of the brain [16-18].

Laboratory diagnosis in cases of suspected acute EBV infection usually consists in detecting the presence of the genetic material of the virus by PCR [

15]. In the case of our patient, the clinical picture with symptoms of fever, nausea and vomiting, then – organomegaly on ultrasonography examination, and the results of laboratory tests (features of liver cell damage, monocytic smear in the peripheral blood image), as well as a positive Monotest and the presence of antibodies to EBV in Elisa test, made the diagnosis. The rash appeared about a week after the first nonspecific symptoms of the disease appeared during the patient's stay at the ICU, which complements the clinical picture characteristic of EBV infection. At the same time, the patient did not present any symptoms of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis which is one of the possible haematological complications of EBV infection. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis predisposes to cytokinopathy and CLOCCs because of high level of cytokines [

19,

20].

The image of the brain in magnetic resonance imaging, i.e. initially normal corpus callosum, with changes appearing in control MRI and subsequently their gradual disappearance in the control tests are also consistent with the CLOCCs picture described in patients with acute neurological complications of EBV infection.

The proposed treatment, if the EBV etiology of infection is proven, especially with severe course with complications from the central nervous system, is acyclovir and steroids, but their effectiveness is variable. In the case of our patient, until the results of negative bacteriological tests of blood and cerebrospinal fluid as well as antigens typical for meningitis were obtained, we used broad-spectral antibiotics with ceftriakson, wancomycin and acyclovir. The antibiotic treatment was then discontinued.

The patient's seizure state resulted in significant disturbances of consciousness, which contributed to the occurrence of acute respiratory failure requiring the use of mechanical ventilation and treatment in the ICU.

Treatment of CLOCCs is symptomatic and focuses on the treatment of the primary disease. In case of severe CLOCCs, immunomodulatory treatment may be considered. This procedure was implemented with good results in a patient with CLOCCs due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection accompanied by neuroinfection described by Lu et al [

21]. A similar procedure was used with good effect in a case with a severe form of Covid-19 infection [

22].

Our patient after recovery did not present any deviations in the neurological examination and the image of the abdominal organs in the ultrasound assessment, nor in the results of laboratory tests, which have been completely normalized. She did not present seizure incidents. In neuroimaging, significant, though partial regression of corpus callosum changes is shown.

Our patient's initial disease was mononucleosis, i.e. an acute infection caused by the Ebstein Barr virus. Chronic infection could lead to prolonged symptoms as a result of chronic inflammation, secondary causing changes in the corpus callosum. Such observations were reported in the work of Voitiuk et al [

23].

Differential diagnosis between CLOCCs and EBV encephalitis is important primarily because of the different treatment and prognosis. Clinical symptoms in the course of CLOCCs tend to be self-limiting, while changes in the magnetic resonance image usually regress with some delay. In our patient, changes in MRI persisted with complete remission of clinical symptoms. This is consistent with previously published data [

6,

24]. In turn, EBV encephalitis, despite the predominant mild clinical course in relation to encephalitis of other etiologies, may be associated with prolonged manifestation of clinical symptoms and the risk of permanent neurological complications. Cheng H et al. in their work on EBV infections noted permanent neurological damage in 14% of patients. The following observations were noted in the above-cited work: cases of neuroinfection were not associated with symptoms of mononucleosis and only 41.5% of patients with CNS involvement had abnormal MRI scans [

25]. The authors of another study also observed a lack of symptoms typical of mononucleosis in most patients with EBV encephalitis [

26]. Our patient initially had symptoms of mononucleosis and was subsequently diagnosed with CLOCCs (secondary to EBV infection). It is also worth recalling that a characteristic MRI scan is essential for the diagnosis of CLOCCs. The fundamental difference between the above-mentioned diseases is the nature of the changes – primary in EBV encephalitis and secondary in CLOCCs. The coexistence of both diseases may make it difficult to make the right diagnosis, i.e. to determine the dominant medical problem in an individual case.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion cases of CLOCCs are reported as secondary syndrome connected with many disease entities. They can be connected with infections (i.e. Covid 19), seizures, antiepileptic treatment, metabolic disturbances, thermogenic drugs, malignancies, SAH, trauma. Clinical presentation can involve asymptomatic cases and severe conditions demanding intensive treatment. It is important to differentiate primary and secondary (CLOCCs) lesions in corpus callosum. General prognosis for CLOCCs is good, though normalization of brain MRI can take even several months. MRI being the only method to show CLOCCs has become an imaging gold standard. Still, clinical abnormalities often precede radiological changes, as happened in reported patient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization IK and JSM and MMS.; methodology, IK and JSM; resources MD and JG; data curation JSM.; writing—original draft preparation IK, JSM and MD.; writing—review and editing IL, MMS. and JG;. supervision MMS; project administration, M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient’s mother to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, Upper Silesian Child Health Centre.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Tanaka-Arakawa MM, Matsui M, Tanaka C, Uematsu A, Uda S, Miura K, et al. (2015) Developmental Changes in the Corpus Callosum from Infancy to Early Adulthood: A Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. PLoS ONE 10(3): e0118760. [CrossRef]

- Moors et al. European Radiology (2024). Cytotoxic lesions of the corpus callosum: a systematic review. European Radiology (2024) 34:4628-4637. 4.

- Häusler M, Ramaekers VT, Doenges M, Schweizer K, Ritter K, Schaade L. Neurological complications of acute and persistent Epstein-Barr virus infection in paediatric patients. J Med Virol. 2002 Oct;68(2):253-63. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González CB, Garnica CN. Cytotoxic lesion of the corpus callosum in pediatrics: A case report. Radiology Case Reports. 18 (2023):2186-2193.

- Moreau A, Ego A, Vandergheynst F, Tacoone FS, Sadeghi N, Montessinos I, Gaspard N, Gorham J. Cytotoxic lesions of corpus callosum ( CLOCCs) associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Journal of Neurology 2021, 268: 1592-1594.

- Chen H, Yu X, Chen Y, Wu H, Wu Z, Zhong J and Tang Z (2023) Reversible splenial lesion syndrome in children: a retrospective study of 130 cases. Front. Neurol. 14:1241549. [CrossRef]

- Scoppettuolo P, Sinkunaite L, Topciu MF, Schulz J. Cytotoxic lesions of the corpus callosum during the course of ketotic hyperglycemia revealing type I diabetes: A case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2023 May 10;11.

- Chen WX, Liu HS, Yang SD, Zeng SH, Gao YY, Du ZH, et al. Reversible splenial lesion syn-drome in children: retrospective study and summary of case series. Brain Dev 2016;38:915-27.

- Barburoglu M, Gunoz Comert R, Huseynov H, Cobanoglu S, Ulukan C, Kipoglu O, et al. Cytotoxic lesions of the corpus callosum: magnetic resonance imaging findings and etiologic factors. J Ist Faculty Med 2022;85(4):447-55. [CrossRef]

- Stamm, B. Lineback, C.M.Tang, M. Jia, D.T. Chrenka, E., Sorond, F.A. Sabayan, B. Diffusion Restriction in the Splenium: A Comparative Study of Cytotoxic Lesions of the Corpus Callosum (CLOCCs) versus Lesions of Vascular Etiology. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6979. [CrossRef]

- Hagemann G, Mentzel HJ, Weisser H, Kunze A, Terborg C. Multiple reversible MR signal changes caused by Epstein-Barr virus encephalitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Aug;27(7):1447-9. PMID: 16908555; PMCID: PMC7977541.

- Cohen, JI. Epstein-Barr virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2000 Aug 17;343(7):481-92. PMID: 10944566. [CrossRef]

- Doja A, Bitnun A, Ford Jones EL, et al. Pediatric Epstein-Barr Virus—Associated Encephalitis: 10-Year Review. Journal of Child Neurology. 2006;21(5):384-391. [CrossRef]

- Caruso JM, Tung GA, Gascon GG, Rogg J, Davis L, Brown WD. Persistent Preceding Focal Neurologic Deficits in Children With Chronic Epstein-Barr Virus Encephalitis. Journal of Child Neurology. 2000;15(12):791-796. [CrossRef]

- Moreau A, Ego A, Vandergheynst F, Tacoone FS, Sadeghi N, Montessinos I, Gaspard N, Gorham J. Cytotoxic lesions of corpus callosum ( CLOCCs) associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Journal of Neurology 2021, 268: 1592-1594.

- 16. Starkey J, Kobayashi N, Numagouchi Y, Moritani T. Cytotoxic lesion of the corpus callosum that show restricted diffusion: mechanisms, causes, and manifestations. RadioGraphics 2017;37:562-576.

- Miller AH, Haroon E, Raison CL, Felger JC. Cytokine targets in the brain: impact on neurotransmitters and neurocircuits. DepressAnxiety 2-13;30(4): 297-306.

- PhelpsC, Korneva E et al. Neuroimmunebiology.Vol 6, Cytokines and the brain. Amsterdam, the Netherlands; Elservier,2008.

- Butterworth RF, Giguère JF, Michaud J, Lavoie J, Layrargues GP. Ammonia: key factor in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Pathol. 1987 Feb-Apr;6(1-2):1-12. PMID: 3306479. [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, RF. Pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy and brain edema in acute liver failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015 Mar;5(Suppl 1):S96-S103. Epub 2014 Jul 9. PMID: 26041966; PMCID: PMC4442857. [CrossRef]

- Lua K, Wub T and Yeh P. Cytotoxic Lesions beyond the Corpus Callosum Following Acute Meningoencephalitis and Mycoplasma Pneumoniae Infection: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Neurol 2023;15:113–119.

- Nie DA (2021) Encephalopathy and Cytotoxic Lesion of the Corpus Callosum Associated with Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: A CaseReport. J Pediatr Neurol Neurosci 5(2):134-137.

- Voitiuk A et al. Differential diagnosis of paroxysmal states: literature Review and analysis of a clinical case on the example of CLOCCs-syndrome in a young man. Wiad Lek. 2022;75(4 p1):907-913.

- van Os, E, Nijhuis M, and Malm S. Clinically mild encephalitis/ encephalopathy with a reversible splenial lesion (MERS) in a child with ataxia and diplopia. JICNA 2019, 19(1).

- Cheng et al. Clinical characteristics of Epstein–Barr virus infection in the pediatric nervous system. BMC Infectious Diseases (2020) 20:886.

- Bolis V, Karadedos Ch, Chiotis I et al. Atypical manifestations of Epstein---Barr virus in children: a diagnostic challenge. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2016;92(2):113---121.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).