Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Morphological Identification

2.3. Molecular Identification

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Identification

- 1a

- large ctenoid scale, longitudinal scales 24-25, predorsal scales 7; pelvic fins origin slightly behind opercula margin .…………………………………..….…………..…..... 2

- 1b

- moderate ctenoid scale, longitudinal scales 29-30, predorsal scales 3-4; pelvic fins origin slightly behind opercula margin .……………………………….......................... 3

- 2a

- big head, head length 35.86 ± 3.28 %SL, head width 62.30 ± 3.15 %HL; mouth large (63.24 ± 0.80 %HL), maxillary extending well beyond posterior margin of eyes both gender; pelvic fins length 22.75 ± 0.36 %SL …………..……… Pseudogobiopsis oligactis

- 2b

- big head, head length 32.60 ± 1.24 %SL, head width 55.61 ± 3.85 %HL; mouth large (48.33 ± 12.41 %HL), in male maxillary extending well beyond posterior margin of eyes (57.10 %HL), and extending to middle of eyes in female (39.56 %HL), pelvic fins length 24.85 ± 0.35 %SL ……………...………….…..….. Eugnathogobius siamensis

- 3a

- mouth moderate large, maxillary extending to middle of eyes in both gender (35.50 ± 3.86 %HL); body moderate slender, body depth at pelvic fins origin 15.85 ± 0.31 %SL; pelvic fins length 19.37 ± 1.15 %SL; caudal fin length 24.77 ± 0.54 %SL ………………………………………………………………… Rhinogobius chiengmaiensis

- 3b

-

mouth moderate large, maxillary extending to middle of eyes in both gender (39.19 ± 2.06 %HL); body very slender, body depth at pelvic fins origin 13.28 ± 0.54 %SL; pelvic fins length 17.88 ± 1.17 %SL; caudal fin length 27.34 ± 2.28 %SL …...……..…..…………………………….……………………………………….. Rhinogobius mekongianus

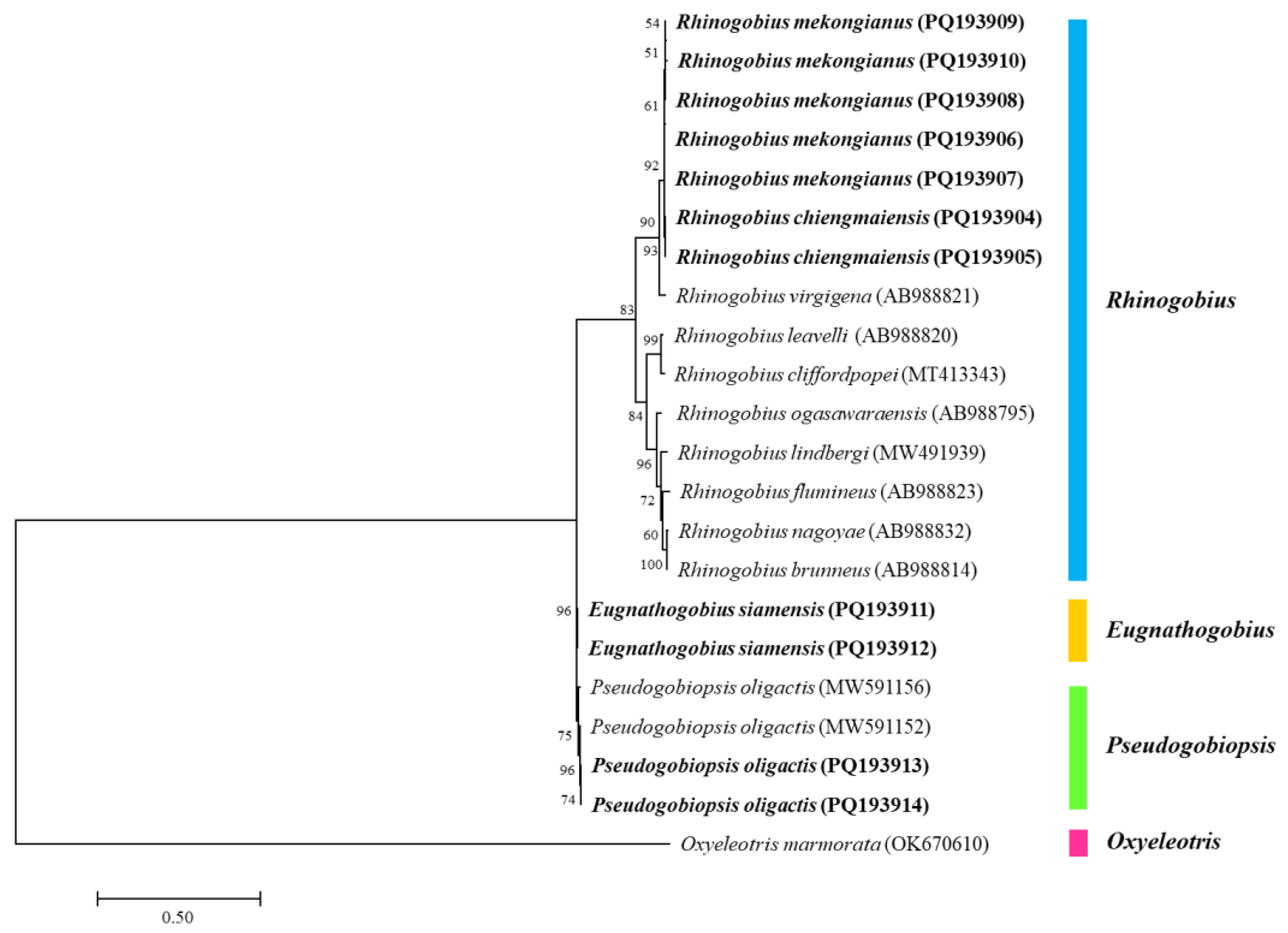

3.2. Molecular Identification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V.H. Fishes of the World, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.S. Fishes of the World, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thacker, C.E. Phylogenetic placement of the European sand gobies in Gobionellidae and characterization of gobionellid lineages (Gobiiformes: Gobioidei). Zootaxa 2013, 3619, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.S.; Kottelat, M.; Miller, P.J. Freshwater gobies of the genus Rhinogobius from the Mekong basin in Thailand and Laos, with descriptions of three new species. Zool. Stud. 1999, 38, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.S.; Miller, P.J. A new freshwater goby of Rhinogobius (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from Hainan Island, southern China. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2013, 21, 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kottelat, M. Zoogeography of the fishes from Indochinese inland waters with an annotated check-list. Bull. ZooI. Mus. Univ. Amsterdam 1989, 12, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- McCraney, W.T.; Thacker, C.E.; Alfaro, M.E. Supermatrix phylogeny resolves goby lineages and reveals unstable root of Gobiaria. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 151, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, C.E.; Roje, D.M. Phylogeny of Gobiidae and identification of gobiid lineages. Syst. Biodivers. 2011, 9(4), 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.H.; Wu, H.L.; Li, C.H.; Wu, Y.Q.; Liu, S.H. A new species of Rhinogobius (Pisces: Gobiidae), with analyses of its DNA barcode. Zootaxa 2018, 4407, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.S.; Wang, S.C.; Shao, K.T. A new freshwater gobiid species of Rhinogobius Gill, 1859 (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from northern Taiwan. Zootaxa 2022, 5189, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Oseko, N.; Yamasaki, Y.Y.; Kimura, S.; Shibukawa, K. A new species with two new subspecies of Rhinogobius (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from Yaeyama Group, the Ryukyu Islands, Japan. Bull. Kanagawa Pref. Mus. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 51, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Iida, M.; Tran, H.D. Taxonomy of freshwater gobies of the genus Rhinogobius (Oxudercidae, Gobiiformes) from central Vietnam, with descriptions of two new species. Zootaxa 2024, 5493(5), 507–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panitvong, N. Freshwater Fishes of Thailand; Parbpim Ltd.: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suvarnaraksha, A.; Utsugi, K. A Field Guild of the Northern Thai Fishes; Maejo University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, and Nagao Natural Environment Foundation: Tokyo, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Cywinska, A.; Ball, S.L.; deWaard, J.R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2003, 270, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Datta, S.K.; Zhilik, A.A. Molecular diversity of freshwater fishes of Bangladesh assessed by DNA barcoding. Bangladesh J. Zool. 2020, 48, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.S.; Datta, S.K.; Saha, T.; Hossain, Z. Molecular characterization of marine and coastal fishes of Bangladesh through DNA barcodes. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 3696–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingpeng, X.; Heshan, L.; Zhilan, Z.; Chunguang, W.; Yanguo, W.; Jianjun, W. DNA barcoding for identification of fish species in the Taiwan Strait. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetapan, K.; Panprommin, N.; Wangkahart, E.; Ruenkoed, S.; Panprommin, D. COI-high resolution melting analysis for discrimination of four fish species in the family Notopteridae in Thailand. Zool. Anz. 2024, 309, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.D.; Zemlak, T.S.; Innes, B.H.; Last, P.R.; Hebert, P.D.N. DNA barcoding Australia's fish species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2005, 360, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panprommin, D.; Manosri, R. DNA barcoding as an approach for species traceability and labeling accuracy of fish fillet products in Thailand. Food Control 2022, 136, 108895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbart, M.; Kerr, M.; Schram, M.J.; Williams, I.; Koziol, G.; Peebles, E.; Stallings, C.D. Evaluation of DNA metabarcoding for identifying fish eggs: a case study on the West Florida Shelf. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y. Unraveling the drifting larval fish community in a large spawning ground in the Middle Pearl River using DNA barcoding. Animals 2022, 12, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao Natural Environment Foundation. Fishes of the Indochinese Mekong; Nagao Natural Environment Foundation: Tokyo, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal Omega, accurate alignment of very large numbers of sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 2014, 1079, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 512–526. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I.S.; Cheng, Y.H.; Shao, K.T. A new species of Rhinogobius (Teleostei: Gobiidae) from the Julongjiang Basin in Fujian Province, China. Ichthyol. Res. 2008, 55, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottelat, M. Fishes of Laos; WHT Publications Ltd.: Colombo, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, H.K. Review of the gobiid fish genera Eugnathogobius and Pseudogobiopsis (Gobioidei: Gobiidae: Gobionellinae), with descriptions of three new species. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2009, 57, 127–181. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.H.; Lim, K.K.P. Rediscovery of the bigmouth stream goby, Pseudogobiopsis oligactis (Actinopterygii: Gobiiformes: Gobionellidae) in Singapore. Nat. Singap. 2011, 4, 363–367. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.M. The freshwater fishes of Siam, or Thailand. Bull. U.S. Natl. Mus. 1945, 188, 1–622. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, A.; Jabeen, F.; Ali, M.; Zafar, S. DNA barcoding and phylogenetics of Wallago attu using mitochondrial COI gene from the River Indus. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2023, 35, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Ratnasingham, S.; de Waard, J.R. Barcoding animal life: cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 divergences among closely related species. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2003, 270 (Suppl_1), S96–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Guan, L.; Wang, D.; Gan, X. DNA barcoding and evaluation of genetic diversity in Cyprinidae fish in the midstream of the Yangtze River. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 2702–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, P.D.N.; Stoeckle, M.Y.; Zemlak, T.S.; Francis, C.M. Identification of birds through DNA barcodes. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agorreta, A.; San Mauro, D.; Schliewen, U.; Van Tassell, J.L.; Kovačić, M.; Zardoya, R.; Rüber, L. Molecular phylogenetics of Gobioidei and phylogenetic placement of European gobies. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 69, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2023. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/.

- Pornsopin, P.; Sirisuksa, T.; Kantiyawong, S.; Surajit, T. Study on cultivation of Chiangmai stream goby (Rhinogobius chiengmaiensis fowler, 1934); Inland Aquaculture Research and Development Division: Bangkok, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Accession no. | Collection site |

|---|---|---|

| Rhinogobius chiengmaiensis | PQ193904-PQ193905 | Ping river basin, Chiang Mai province |

| Rhinogobius mekongianus | PQ193906-PQ193910 | Kok River, Chiang Mai province |

| Eugnathogobius siamensis | PQ193911-PQ193912 | Surat Thani province |

| Pseudogobiopsis oligactis | PQ193913-PQ193914 | Satun province |

| Characters | R. chiengmaiensis | R. mekongianus | E. siamensis | P. oligactis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL (mm) | 28.82 ± 0.51 | 29.16 ± 2.95 | 30.48 ± 2.98 | 29.42 ± 3.68 |

| As % in SL | ||||

| Head length | 31.82 ± 1.67 | 30.50 ± 0.38 | 32.60 ± 1.24 | 35.86 ± 3.28 |

| Head width | 16.46 ± 3.06 | 15.23 ± 1.90 | 18.11 ± 0.57 | 22.39 ± 3.17 |

| Body depth at P2 | 15.85 ± 0.31 | 13.28 ± 0.54 | 18.08 ± 2.29 | 15.88 ± 0.51 |

| Body depth at A | 14.80 ± 0.24 | 11.78 ± 0.37 | 16.49 ± 1.94 | 13.52 ± 0.72 |

| Snout to D1 | 37.28 ± 1.59 | 39.66 ± 2.02 | 39.56 ± 3.06 | 45.14 ± 1.75 |

| Snout to D2 | 59.50 ± 2.57 | 59.01 ± 3.47 | 61.91 ± 2.21 | 58.13 ± 0.89 |

| Snout to A | 65.08 ± 1.89 | 64.27 ± 0.31 | 65.00 ± 1.75 | 63.29 ± 2.38 |

| Snout to P2 | 29.71 ± 2.56 | 29.33 ± 0.18 | 33.31 ± 1.54 | 36.06 ± 0.37 |

| D1 base length | 15.24 ± 2.40 | 14.46 ± 1.18 | 13.16 ± 0.13 | 8.84 ± 0.50 |

| D1 base length | 20.62 ± 2.94 | 17.39 ± 0.98 | 16.95 ± 0.29 | 16.31 ± 1.47 |

| A base length | 14.19 ± 0.01 | 13.72 ± 0.17 | 15.85 ± 1.16 | 13.31 ± 3.12 |

| C length | 24.77 ± 0.54 | 27.34 ± 2.28 | 22.61 ± 3.17 | - |

| Caudal peduncle length | 20.60 ± 1.03 | 19.72 ± 0.15 | 20.53 ± 1.52 | 13.95 ± 2.88 |

| Caudal peduncle depth | 11.55 ± 0.38 | 9.62 ± 0.54 | 11.38 ± 0.44 | 10.56 ± 0.56 |

| P1 length | 20.74 ± 6.94 | 25.48 ± 1.84 | 28.63 ± 0.56 | 22.70 ± 0.37 |

| P2 length | 19.37 ± 1.15 | 17.88 ± 1.17 | 24.85 ± 0.35 | 22.75 ± 0.36 |

| As % in HL | ||||

| Snout length | 29.76 ± 1.44 | 27.92 ± 2.71 | 27.98 ± 0.75 | 27.79 ± 0.01 |

| Eye diameter | 20.16 ± 1.39 | 19.74 ± 0.57 | 13.16 ± 0.72 | 12.63 ± 0.19 |

| Postorbital length | 50.08 ± 0.04 | 52.34 ± 2.13 | 58.87 ± 0.03 | 59.58 ± 0.17 |

| Interorbital space | 21.93 ± 0.01 | 16.35 ± 1.22 | 19.13 ± 0.03 | 19.99 ± 1.23 |

| snout to maxilla | 35.50 ± 3.86 | 39.19 ± 2.06 | 48.33 ± 12.41 | 63.24 ± 0.80 |

| Head width | 51.54 ± 6.93 | 49.97 ± 6.87 | 55.61 ± 3.85 | 62.30 ± 3.15 |

| Species | Nucleotide composition (%) | %GC content |

%AT content |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | C | A | G | ||||

| R. chiengmaiensis | 29.7 ± 0.0 | 28.8 ± 0.0 | 22.3 ± 0.0 | 19.2 ± 0.0 | 48.0 ± 0.0 | 52.0 ± 0.0 | |

| R. mekongianus | 30.0 ± 0.1 | 28.5 ± 0.0 | 22.2 ± 0.1 | 19.3 ± 0.1 | 47.8 ± 0.1 | 52.2 ± 0.1 | |

| E. siamensis | 27.4 ± 0.0 | 28.6 ± 0.0 | 24.3 ± 0.0 | 19.7 ± 0.0 | 48.3 ± 0.0 | 51.7 ± 0.0 | |

| P. oligactis | 27.3 ± 0.0 | 28.7 ± 0.0 | 23.6 ± 0.0 | 20.4 ± 0.0 | 49.1 ± 0.0 | 50.9 ± 0.0 | |

| Average | 29.0 ± 1.3 | 28.6 ± 0.1 | 22.9 ± 0.9 | 19.5 ± 0.5 | 48.2 ± 0.5 | 51.8 ± 0.5 | |

| Species | R. chiengmaiensis | R. mekongianus | E. siamensis | P. oligactis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. chiengmaiensis | 0.00 | |||

| R. mekongianus | 0.86 | 0.28 | ||

| E. siamensis | 15.38 | 11.02 | 0.00 | |

| P. oligactis | 16.63 | 12.00 | 1.64 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).