Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

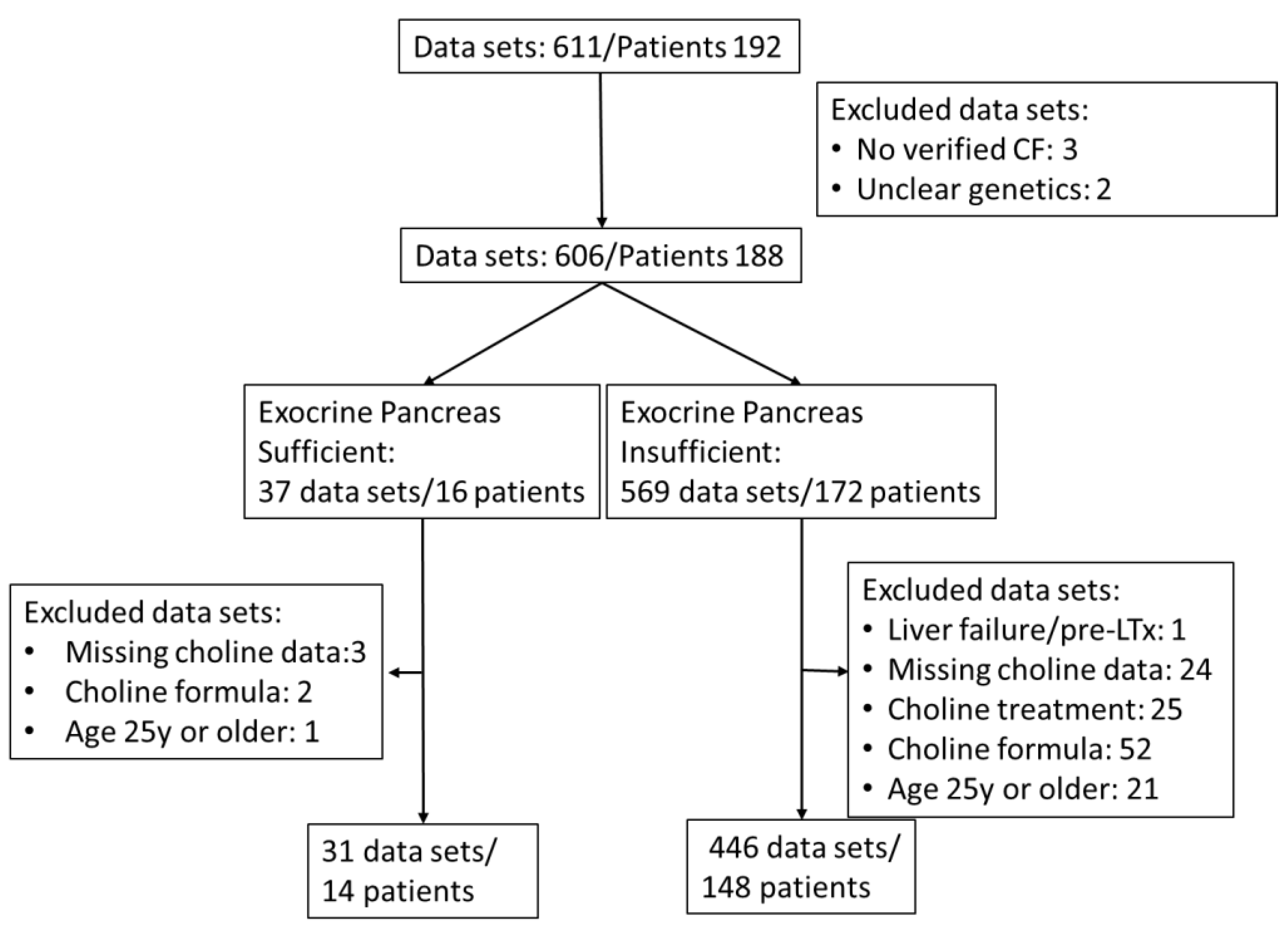

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Exclusion of Additional Choline Intake

| Inclusion parameter | Genetically verified Cystic Fibrosis with or without exocrine pancreas insufficiency; Age 0 to <25 y |

| Exclusion Parameters | Acute liver failure Pre-transplantation status choline supplementation via prescribed choline or dietary supplements 25 y or older No data on choline parameters |

2.4. Plasma Collection

2.5. Mass Spectrometry

2.6. Clinical Parameters

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Parameters of Choline Homeostasis in the Whole Study Group

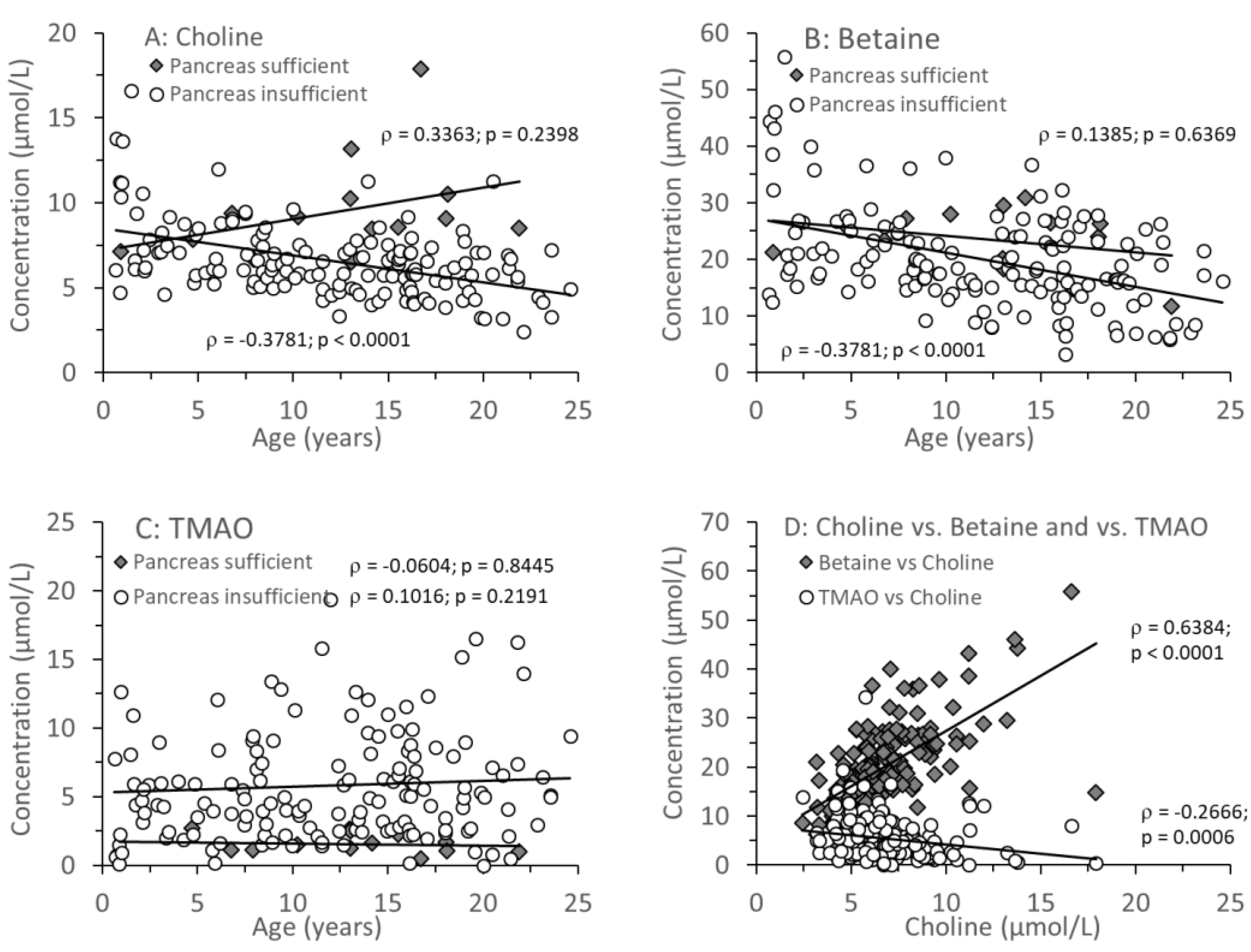

3.2. Age-Related Changes of Water-Soluble Choline Compounds in Plasma

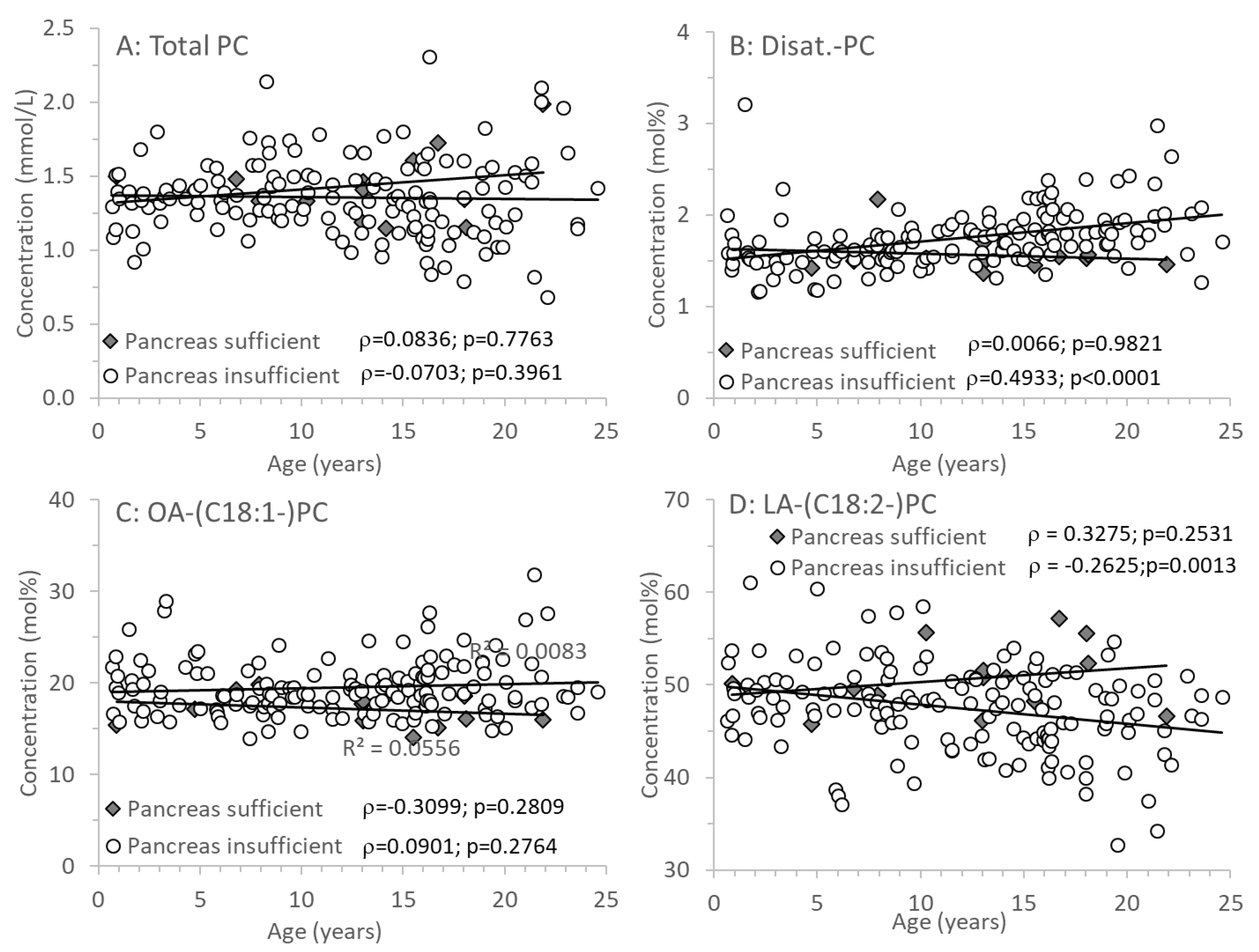

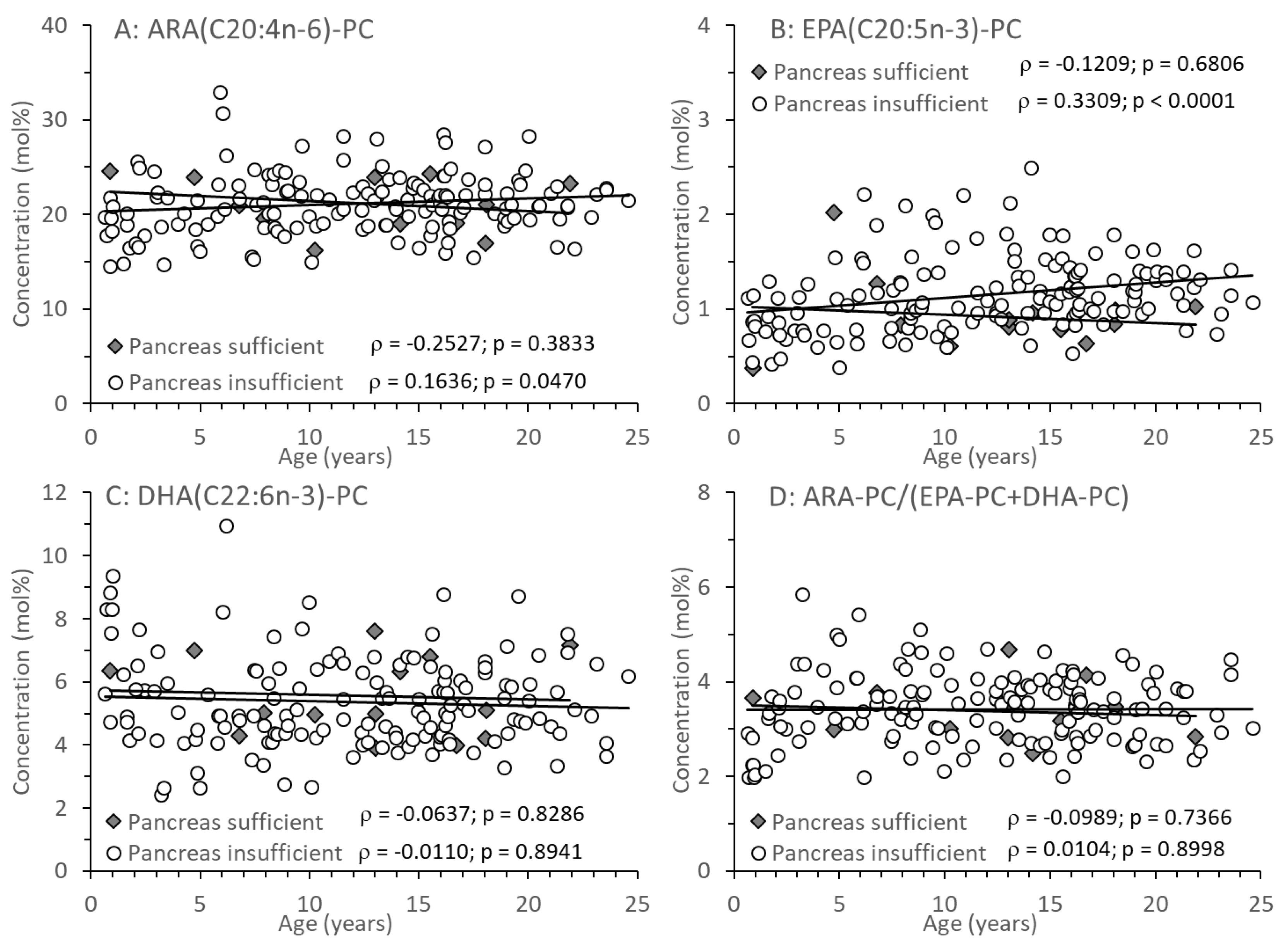

3.3. Age-Related Changes of PC and Its Sub-Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Plasma Choline and Betaine Levels in Relation to Exocrine Pancreas Function

4.2. The Impact of Small Intestinal Bacterial Colonization and PEMT Genetics

4.3. Effects of Age on Plasma Choline and TMAO Levels

4.4. Plasma Phospholipids and Long-Chain Poly-Unsaturated Fatty Acids (LC-PUFA) in CF

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naehrig, S.; Chao, C.-M.; Naehrlich, L. Mukoviszidose - Diagnose und Therapie (Cystic fibrosis—diagnosis and treatment). Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017, 114, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosorok, M.R.; Wei, W.H.; Farrell, P.M. The incidence of cystic fibrosis. Stat Med 1996, 15, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskin S, Pereira-Ferrari L, Reis FC, Abreu F, Marostica P, Rozov T, Cardieri J, Ludwig N, Valentin L, Rosario-Filho NA, Camargo Neto E, Lewis E, Giugliani R, Diniz EM, Culpi L, Phillip JA 3rd, Chakraborty R. Incidence of cystic fibrosis in five different states of Brazil as determined by screening of p.F508del, mutation at the CFTR gene in newborns and patients. J Cyst Fibros 2008, 7, 15–22.

- Scotet, V.; Duguépéroux, I.; Saliou, P.; Rault, G.; Roussey, M.; Audrézet, M.P.; Férec, C. Evidence for decline in the incidence of cystic fibrosis: a 35-year observational study in Brittany, France. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoo AF, Thia LP, Nguyen TT, Bush A, Chudleigh J, Lum S, Ahmed D, Balfour Lynn I, Carr SB, Chavasse RJ, Costeloe KL, Price J, Shankar A, Wallis C, Wyatt HA, Wade A, Stocks J; London Cystic Fibrosis Collaboration. Lung function is abnormal in 3-month-old infants with cystic fibrosis diagnosed by newborn screening. Thorax 2012, 67, 874–881.

- Korten I, Kieninger E, Yammine S, Cangiano G, Nyilas S, Anagnostopoulou P, Singer F, Kuehni CE, Regamey N, Frey U, Casaulta C, Spycher BD, Latzin P; SCILD; BILD study group. Respiratory rate in infants with cystic fibrosis throughout the first year of life and association with lung clearance index measured shortly after birth. J Cyst Fibros 2019, 18, 118–126. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, C.; Battezzati, P.M.; Crosignani, A.; Morabito, A.; Costantini, D.; Padoan, R.; Giunta, A. Liver disease in cystic fibrosis: a prospective study on incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Hepatology 2002, 36, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.M.; Goodman, R.; Thomson, R.; Mchugh, K.; Lindsell, D.R.M. Ultrasound evaluation of liver disease in cystic fibrosis as part of an annual assessment clinic: a 9-year review. Clin. Radiol. 2002, 57, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debray, D.; Kelly, D.; Houwen, R.; Strandvik, B.; Colombo, C. Best practice guidance for the diagnosis and management of cystic fibrosis- associated liver disease. J Cyst Fibros 2011, 10 (Suppl 2), 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, K.; Gurwitz, D.; Durie, P.; Corey, M.; Levison, H.; Forstner, G. Improved respiratory prognosis in patients with cystic fibrosis with normal fat absorption. J Pediatr 1982, 100, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.H.; Innis, S.M.; Davidson, A.G.; James, S.J. Phosphatidylcholine and lysophosphatidylcholine excretion is increased in children with cystic fibrosis and is associated with plasma homocysteine, S-adenosylhomocysteine, and S-adenosylmethionine. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 81, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grothe, J.; Riethmüller, J.; Tschürtz, S.M.; Raith, M.; Pynn, C.J.; Stoll, D.; Bernhard, W. Plasma phosphatidylcholine alterations in cystic fibrosis patients: impaired metabolism and correlation with lung function and inflammation. Cell Physiol Biochem 2015, 35, 1437–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry. Annual Data Report. Bethesda, Maryland, 2010: http://www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/LivingWithCF/CareCenterNetwork/PatientRegistry/2010-Patient-Registry-Report.pdf.

- Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Registry. Annual Report. Toronto, Ontario,CAN, 2011: http://www.cysticfibrosis.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Registry2011FINALOnlineEN.pdf.

- Lindblad, A.; Glaumann, H.; Strandvik, B. Natural history of liver disease in cystic fibrosis. Hepatology 1999, 30, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury, N.A. Intracellular CFTR: Localization and function. Physiol Rev 2011, 79, S175–S191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, C.; Battezzati, P.M.; Crosignani, A.; Morabito, A.; Costantini, D.; Padoan, R.; Giunta, A. Liver disease in cystic fibrosis: a prospective study on incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Hepatology 2002, 36, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.M.; Goodman, R.; Thomson, R.; Mchugh, K.; Lindsell, D.R.M. Ultrasound evaluation of liver disease in cystic fibrosis as part of an annual assessment clinic: a 9-year review. Clin Radiol 2002, 57, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, U.; Dockter, G.; Lammert, F. Cystic fibrosis-associated liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2010, 24, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, F.; Broderick, A.L.; Yu, B.B.; Leonard, M.R.; Glickman, J.N.; Carey, M.C. Pathophysiological basis of liver disease in cystic fibrosis employing a DeltaF508 mouse model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2008, 294, G1411–G1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.M.; da Costa, K.A.; Kwock, L.; Galanko, J.; Zeisel, S.H. Dietary choline requirements of women: effects of estrogen and genetic variation. Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 92, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, A.L.; Dubin, M.; Jenden, D.; Moukarzel, A.; Roch, M.H.; Rice, K.; Gornbein, J.; Ament, M.E.; Eckhert, C.D. Lecithin increases plasma free choline and decreases hepatic steatosis in long-term total parenteral nutrition patients. Gastroenterology 1992, 102, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, A.A. Lecithin increases plasma free choline and decreases hepatic steatosis in long-term total parenteral nutrition patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1992, 16, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, A.L.; Dubin, M.D.; Moukarzel, A.A.; Jenden, D.J.; Roch, M.; Rice, K.M.; Gornbein, J.; Ament, M.E. Choline deficiency: a cause of hepatic steatosis during parenteral nutrition that can be reversed with intravenous choline supplementation. Hepatology 1995, 22, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boujaoude, L.C.; Bradshaw-Wilder, C.; Mao, C.; Cohn, J.; Ogretmen, B.; Hannun, Y.A.; Obeid, L.M. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator regulates uptake of sphingoid base phosphates and lysophosphatidic acid: modulation of cellular activity of sphingosine 1-phosphate. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 35258–35264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheele GA, Fukuoka SI, Kern HF, Freedman SD (1996) Pancreatic dysfunction in cystic fibrosis occurs as a result of impairments in luminal pH, apical trafficking of zymogen granule membranes, and solubilization of secretory enzymes. Pancreas 1996, 12, 1–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard WCholine in cystic fibrosis: relations to pancreas insufficiency, enterohepatic cycle, PEMT and intestinal microbiota. Eur J Nutr 2021, 60, 1737–1759. [CrossRef]

- Linsdell, P.; Hanrahan, J.W. Glutathione permeability of CFTR. Am J Physiol 1998, 275, C323–C326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowitz, D. CFTR, bicarbonate, and the pathophysiology of cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015, 50 (Suppl 40), S24–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan I, Ramjeesingh M, Li C, Kidd JF, Wang Y, Leslie EM, Cole SP, Bear CE. CFTR directly mediates nucleotide-regulated glutathione flux. EMBO J 2003, 22, 1981–1989.

- Sbodio, J.I.; Snyder, S.H.; Paul, B.D. Regulators of the transsulfuration pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Böckmann, K.A.; Minarski, M.; Wiechers, C.; Busch, A.; Bach, D.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Evidence and Perspectives for Choline Supplementation during Parenteral Nutrition-A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northfield, T.C.; Hofmann, A.F. Biliary lipid output during three meals and an overnight fast. I. Relationship to bile acid pool size and cholesterol saturation of bile in gallstone and control subjects. Gut 1975, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nilsson Å, Duan RD. Pancreatic and mucosal enzymes in choline phospholipid digestion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2019, 316, G425–G445. [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Raith, M.; Shunova, A.; Lorenz, S.; Böckmann, K.; Minarski, M.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Choline Kinetics in Neonatal Liver, Brain and Lung-Lessons from a Rodent Model for Neonatal Care. Nutrients 2022, 14, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, C.R.; Kempson, S.A. Betaine chemistry, roles, and potential use in liver disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2016, 1860, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innis, S.M.; Davidson, A.G.; Melynk, S.; James, S.J. Choline-related supplements improve abnormal plasma methionine-homocysteine metabolites and glutathione status in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2007, 85, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Lange, R.; Graepler-Mainka, U.; Engel, C.; Machann, J.; Hund, V.; Shunova, A.; Hector, A.; Riethmüller, J. Choline Supplementation in Cystic Fibrosis-The Metabolic and Clinical Impact. Nutrients 2019, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northfield, T.C.; Hofmann, A.F. Biliary lipid output during three meals and an overnight fast. I. Relationship to bile acid pool size and cholesterol saturation of bile in gallstone and control subjects. Gut 1975, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natl Acad Sci, U.S.A. Dietary Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline (1998) Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114310/pdf/ Bookshelf_NBK114310.pdf.

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Dietary Reference Values for choline. EFSA Journal 2016, 14, 4484. [CrossRef]

- Bailey RL, Pac SG, Fulgoni VL 3rd, Reidy KC, Catalano PM. Estimation of Total Usual Dietary Intakes of Pregnant Women in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e195967. [CrossRef]

- Probst, Y.; Guan, V.; Neale, E. Development of a Choline Database to Estimate Australian Population Intakes. Nutrients 2019, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The LipidWeb (2020) Plasma lipoproteins. https://lipidmaps.org/resources/lipidweb/lipidweb_html/lipids/simple/lipoprot/index.htm (acc. 2024.11.08).

- Bernhard, W.; Maas, C.; Shunova, A.; Mathes, M.; Böckmann, K.; Bleeker, C.; Vek, J.; Poets, C.F.; Schleicher, E.; Franz, A.R. Transport of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in preterm infant plasma is dominated by phosphatidylcholine. Eur J Nutr 2018, 57, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, S.R.; Tao, J.Q.; Yu, K.J.; Borok, Z.; Crandall, E.D.; Collins, H.L.; Rothblat, G.H. Expression and biological activity of ABCA1 in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008, 38, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agassandian, M.; Miakotina, O.L.; Andrews, M.; Mathur, S.N.; Mallampalli, R, K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and sPLA2 IB stimulate ABCA1-mediated phospholipid efflux via ERK-activation of PPARalpha-RXR. Biochem J, 2007, 403, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Agellon, L.B.; Vance, D.E. Choline redistribution during adaptation to choline deprivation. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 10283–10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Agellon, L.B.; Vance, D.E. Phosphatidylcholine homeostasis and liver failure. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 37798–37802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food allergens (NDA), Turck D, Bohn T, Castenmiller J, De Henauw S, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Knutsen HK, Maciuk A, Mangelsdorf I, McArdle HJ, Naska A, Pentieva K, Thies F, Tsabouri S, Vinceti M, Bresson J-L, Fiolet T, Siani A. Choline and contribution to normal liver function of the foetus and exclusively breastfed infants: evaluation of a health claim pursuant to Article 14 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA Journal 2023, 21. [CrossRef]

- Resseguie, M.E.; da Costa, K.A.; Galanko, J.A.; Patel, M.; Davis, I.J.; Zeisel, S.H. Aberrant estrogen regulation of PEMT results in choline deficiency-associated liver dysfunction. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa KA, Corbin KD, Niculescu MD, Galanko JA, Zeisel SH. Identification of new genetic polymorphisms that alter the dietary requirement for choline and vary in their distribution across ethnic and racial groups. FASEB J 2014, 28, 2970–2978. [CrossRef]

- Piras, I.S.; Raju, A.; Don, J.; Schork, N.J.; Gerhard, G.S.; DiStefano, J.K. Hepatic PEMT Expression Decreases with Increasing NAFLD Severity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvol, H.; Blackman, S.M.; Boëlle, P.Y.; Gallins, P.J.; Pace, R.G.; Stonebraker, J.R.; Accurso, F.J.; Clement, A.; Collaco, J.M.; Dang, H.; Dang, A.T.; Franca, A.; Gong, J.; Guillot, L.; Keenan, K.; Li, W.; Lin, F.; Patrone, M.V.; Raraigh, K.S.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.H.; O'Neal, W.K.; Sontag, M.K.; Levy, H.; Durie, P.R.; Rommens, J.M.; Drumm, M.L.; Wright, F.A.; Strug, L.J.; Cutting, G.R.; Knowles, M.R. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies five modifier loci of lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa KA, Kozyreva OG, Song J, Galanko JA, Fischer LM, Zeisel SH. Common genetic polymorphisms affect the human requirement for the nutrient choline. FASEB J 2006, 20, 1336–1344.

- Meyer KA, Benton TZ, Bennett BJ, Jacobs DR Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Gross MD, Carr JJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Zeisel SH. Microbiota-Dependent Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Coronary Artery Calcium in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA). J Am Heart Assoc 2016, 5, e003970. [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Choline and choline-related nutrients in regular and preterm infant growth. Eur J Nutr 2019, 58, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, W.; Shunova, A.; Machann, J.; Grimmel, M.; Haack, T.B.; Utz, P.; Graepler-Mainka, U. Resolution of severe hepatosteatosis in a cystic fibrosis patient with multifactorial choline deficiency: A case report. Nutrition 2021, 89, 111348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, W.; Raith, M.; Kunze, R.; Koch, V.; Heni, M.; Maas, C.; Abele, H.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Choline concentrations are lower in postnatal plasma of preterm infants than in cord plasma. Eur J Nutr 2015, 54, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Raith, M.; Koch, V.; Maas, C.; Abele, H.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Developmental changes in polyunsaturated fetal plasma phospholipids and feto-maternal plasma phospholipid ratios and their association with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Eur J Nutr 2016, 55, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roum, J.H.; Buhl, R.; McElvaney, N.G.; Borok, Z.; Crystal, R.G. Systemic deficiency of glutathione in cystic fibrosis. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993, 75, 2419–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsdell, P.; Hanrahan, J.W. Glutathione permeability of CFTR. Am J Physiol 1998, 275, C323–C326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan I, Ramjeesingh M, Li C, Kidd JF, Wang Y, Leslie EM, Cole SP, Bear CE. CFTR directly mediates nucleotide-regulated glutathione flux. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1981–1989.

- Ratjen, F. The future of cystic fibrosis: A global perspective. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024 Oct 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Agellon, L.B.; Vance, D.E. Choline redistribution during adaptation to choline deprivation. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 10283–10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleuser, B.; Schumacher, F.; Gulbins, E. New Therapeutic Options in Pulmonal Diseases: Sphingolipids and Modulation of Sphingolipid Metabolism. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2024, 284, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, A.L.; Ament, M.E.; Sohel, M.; Dubin, M.; Jenden, D.J.; Roch, M.; Pownall, H.; Farley, W.; Awal, M.; Ahn, C. Choline deficiency causes reversible hepatic abnormalities in patients receiving parenteral nutrition: proof of a human choline requirement: a placebo-controlled trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2001, 25, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narkewicz, M.R. Integrating Clinical Ultrasound Into Screening for Cystic Fibrosis Liver Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019, 69, 394–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, A.L.; Sohel, M.; Moukarzel, A.; Bryant, D.; Schanler, R.; Awal, M.; Burns, P.; Dorman, K.; Belfort, M.; Jenden, D.J.; Killip, D.; Roch, M. Plasma choline in normal newborns, infants, toddlers, and in very-low-birth-weight neonates requiring total parenteral nutrition. Nutrition 2001, 17, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al-Waiz M, Mikov M, Mitchell SC, Smith RL. The exogenous origin of trimethylamine in the mouse. Metabolism 1992, 41, 135–136.

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; Dugar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.M.; Wu, Y.; Schauer, P.; Smith, J.D.; Allayee, H.; Tang, W.H.; DiDonato, J.A.; Lusis, A.J.; Hazen, S.L. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.H.; Yeung, C.K.; Peter, R.M.; Ibarra, C.; Gasser, R.; Itagaki, K.; Philpot, R.M.; Rettie, A.E. Isoform specificity of trimethylamine N-oxygenation by human flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO) and P450 enzymes: selective catalysis by FMO3. Biochem Pharmacol 1998, 56, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, W.; Böckmann, K.; Maas, C.; Mathes, M.; Hövelmann, J.; Shunova, A.; Hund, V.; Schleicher, E.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Combined choline and DHA supplementation: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Nutr 2020, 59, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckmann, K.A.; Franz, A.R.; Minarski, M.; Shunova, A.; Maiwald, C.A.; Schwarz, J.; Gross, M.; Poets, C.F.; Bernhard, W. Differential metabolism of choline supplements in adult volunteers. Eur J Nutr 2022, 61, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, A. The addition of choline to parenteral nutrition. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, S119–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumpf, V.J. Parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease in adult and pediatric patients. Nutr Clin Pract 21 2006, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, N.; Rout-Pitt, N.; McCarron, A.; Jackson, C.A.; Bulmer, A.C.; McAinch, A.J.; Donnelley, M.; Parsons, D.W.; Hryciw, D.H. Changes in Essential Fatty Acids and Ileal Genes Associated with Metabolizing Enzymes and Fatty Acid Transporters in Rodent Models of Cystic Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Exocrine pancreatic sufficiency | Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency |

| Number of Patients (and Data Sets) | 14 (31) | 148 (446) |

| F508del compound heterocygous F508del homocygous Other |

4 0 10 |

78 53 17 |

| Median Age at CF Diagnosis (y) | 1.04 (0.92-5.34) | 0.27 (0.10-1.67) p=0.0009 |

| Age at Measurements (y) | 13.03 (8.50-16.42) [0.89-21.90] |

12.66 (7.22-16.36) [0.64-24.58] p=0.(8208 |

| Sex (male/female) | 8/6 | 68/80; p=0.4258 |

| Body weight (kg) | 44.9 (28.8-56.8) | 38.1 (22.2-54.6) p=0.3634 |

| Body length (cm) | 156.0 (131.2-161.5) (71-181) | 150,9 (117.0-165.0) (61-188) p=0.7324 |

| (BMI (kg/m2) | 18.2 (17.2-21.4) | 17.2 (15.8-20.1) p=0.2199 |

| BMI Percentile (%) | 57,5 (26.8-73.3) | 40.0 (18.6-64.8) p=0.3051 |

| Coagulation (Quick) [70–120] | 95 (88-103) | 89 (79-100) p=0.0808 |

| Thrombocytes (103/µL) | 281 (256-298) | 304 (260-355) p=0.2566 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) [130–190] | 137(126-152) | 128 (105-143) p=0.3272 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) [<200] | 68 (55-74) | 83 (62-117) p=0.1218 |

| Albumin (g/dL) [3.0-5.0] | 4.3 (4.1-4.4) | 4.0 (3.8-4.2) p=0.0016 |

| AST [<39 U/L] | 19 (16-32) | 25 (19-36) p=0.0879 |

| ALT [<39U/L] | 17 (13-20) | 25 (20-34) p=0.0021 |

| AP [130-400] | 225 (134-267) | 225(150-279) p=0.7037 |

| gGT [<30U/L] | 12 (10-13) | 12 (10-20) p=0.2901 |

| Lipid-soluble vitamins A (µmol/L) [1.1-2.7] |

1.50 (1.15-1.70) |

1.40 (1.20-1.60) p=0.6669 |

| E (µmol/L) [10-40] | 24.3 (20.7-24.6) | 20.4 (15.7-24.8) p=0.0518 |

| D (nmol/L) [50-175] | [130–40054.0 (46.6-59.0) | 51.0 (35.0-63.8) p=0.5444 |

| Lung function parameters ppFEV1 (%)* FVC (%)* FEF 25 (%)* FEF25-75 (%)* |

97 (88-101) 103 (87-107) 104 (75-125) 93 (74-117) |

96 (83-104) p=0.9754 100 (93-107) p=0.8155 80 (57-106) p=0.0450 84 (64-100) p=0.0843 |

| Parameter | EPS | EPI | P-level |

| A: Choline and water-soluble derivatives | |||

| Choline (µmol/L) | 8.8 (8.0-10.0) | 6.1 (5.2-7.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Betaine (µmol/L) | 24.9 (21.4-27.1) | 18.6 (14.8-24.6) | 0.0287 |

| Choline + Betaine | 33.3 (30.9-35.6) | 25.3 (20.5-31.9) | 0.0020 |

| TMAO (µmol/L) | 1.4 (1.1-2.1) | 4.9 (2.6-8.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Betaine/Choline | 2.64 (2.36-3.31) | 3.00 (2.473.66) | 0.0772 |

| TMAO/Choline | 0.18 (0.13-0.20) | 0.71 (0.44-1.35) | < 0.0001 |

| B: Phospholipids | |||

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) (mmol/L) | 1.41 (1.33-1.50) | 1.35 (1.19-1.51) | 0.2927 |

| Lyso-PC (% of PC) | 2.57 (1.90-3.41) | 2.56 (2.01-3.09) | 0.7318 |

| SPH (% of PC) | 25.2 (21.1-29.3) | 23.2 (20.6-26.2) | 0.2344 |

| Ceramides (% of PC) | 0.27 (0.17-0.31) | 0.24 (0.19-0.30) | 0.6938 |

| C: PC sub-groups | |||

| Disaturated PC | 1.53 (1.47-1.57) | 1.70 (1.54-1.88) | 0.0056 |

| Oleyl (C18:1)-PC | 17.4 (15.9-18.6) | 18.9 (17.4-21.1) | 0.0031 |

| Linoleoyl (C18:2)-PC | 50.5 (48.4-52.1) | 47.9 (44.5-50.5) | 0.0121 |

| Arachidonoyl (C20:4)-PC | 21.3 (19.2-23.8) | 20.9 (18.9-23.0) | 0.7543 |

| Eicosapentaenoyl (C20:5)-PC | 0.86 (0.79-0.98) | 1.11 (0.88-1.37) | 0.0119 |

| Docosahexaenoyl: C22:6-PC | 5.06 (4.46-6.69) | 5.02 (4.34-6.29) | 0.4949 |

| Other PC* | 2.55 (2.37-2.96) | 2.43 (2.88-4.22) | 0.0005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).