Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

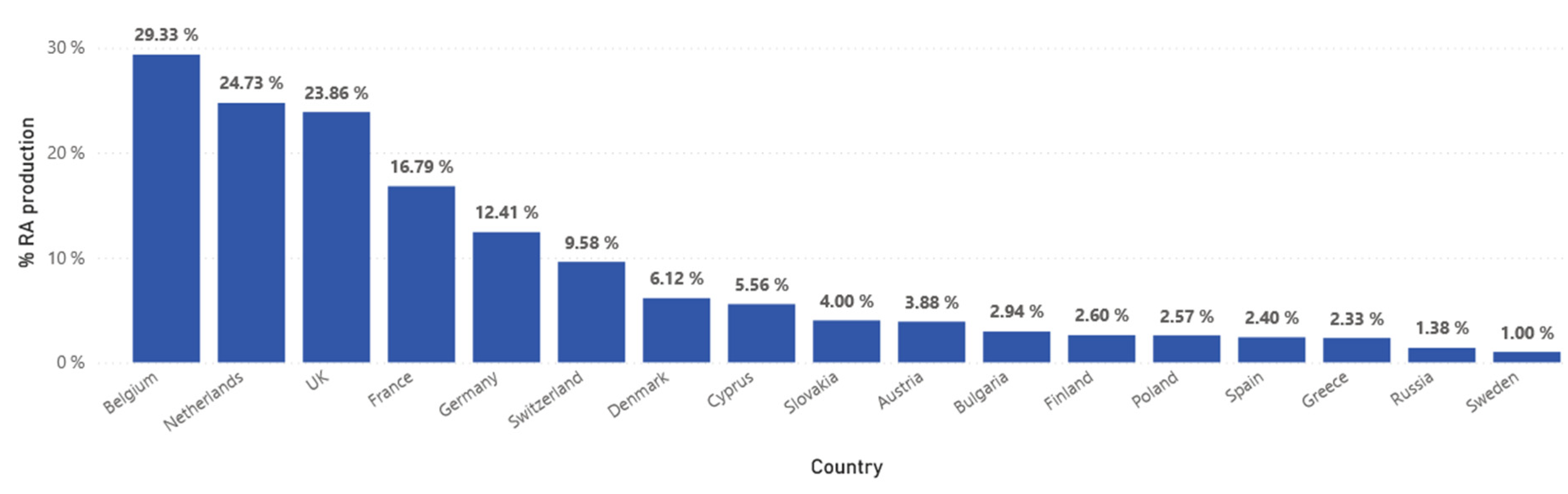

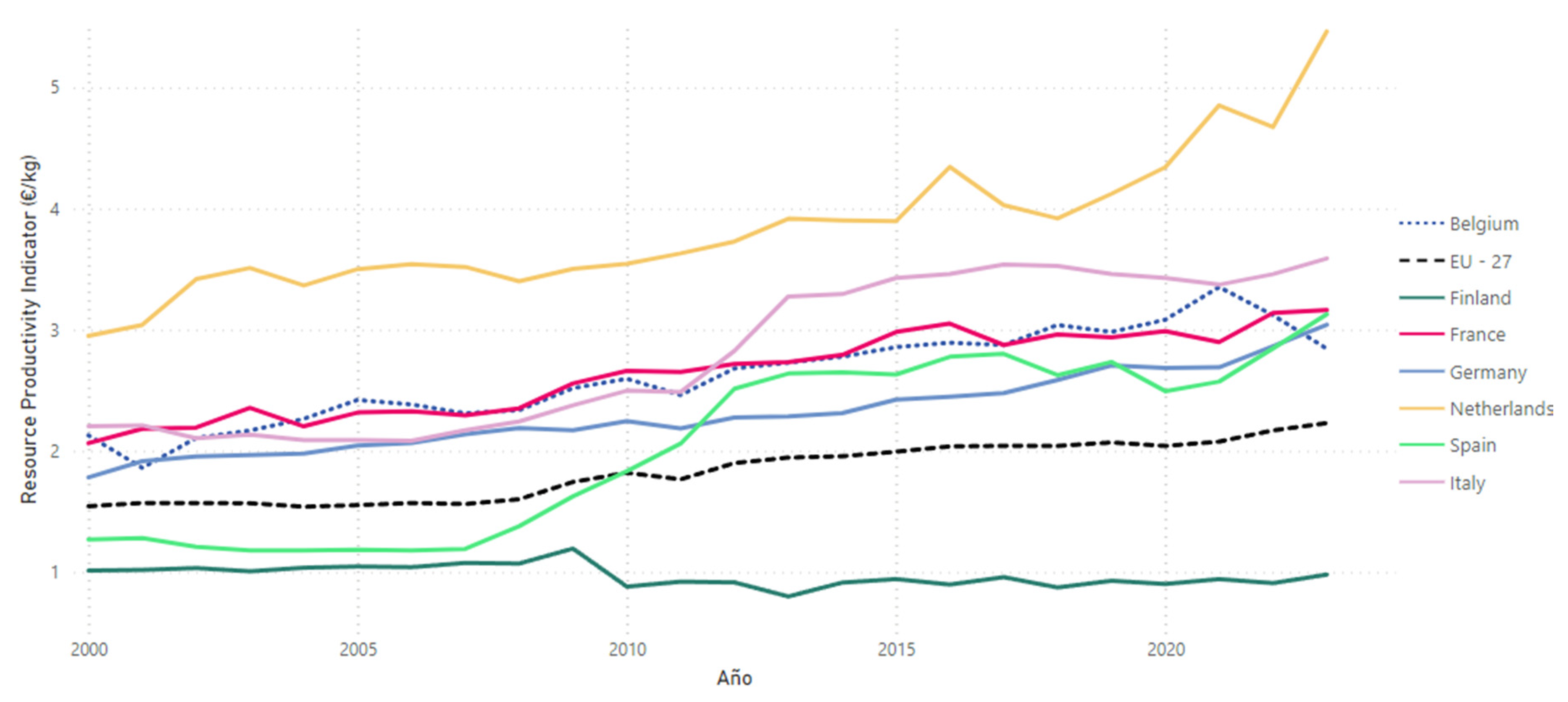

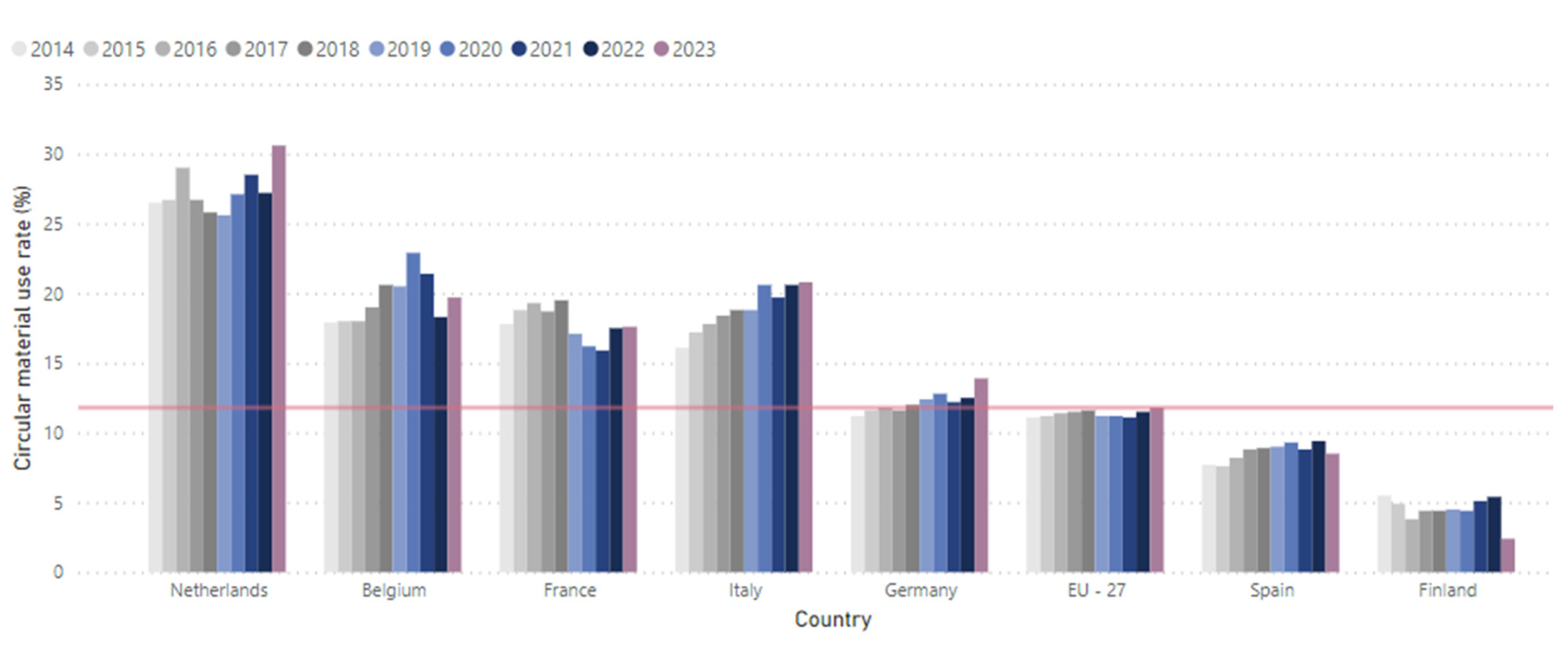

1. Introduction

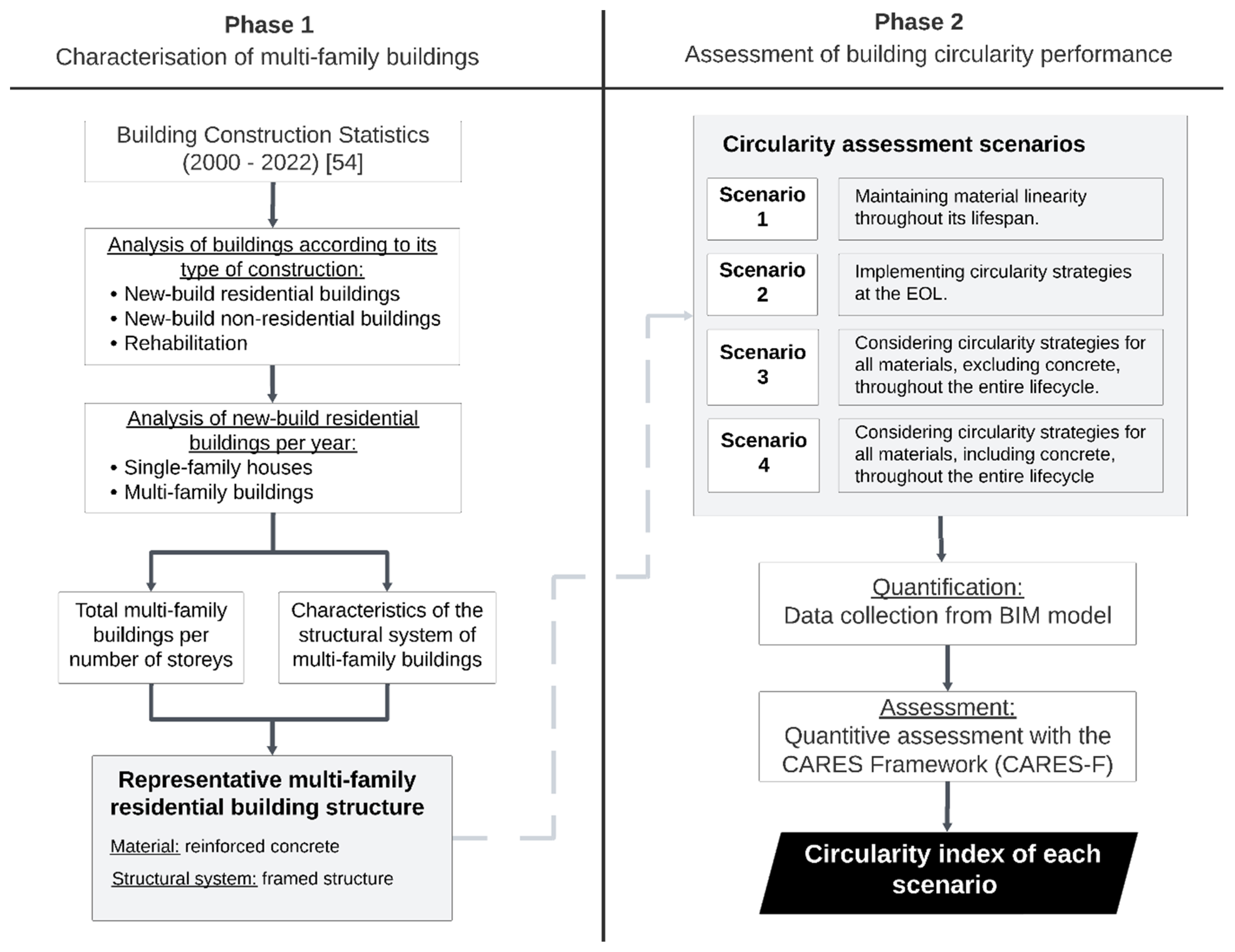

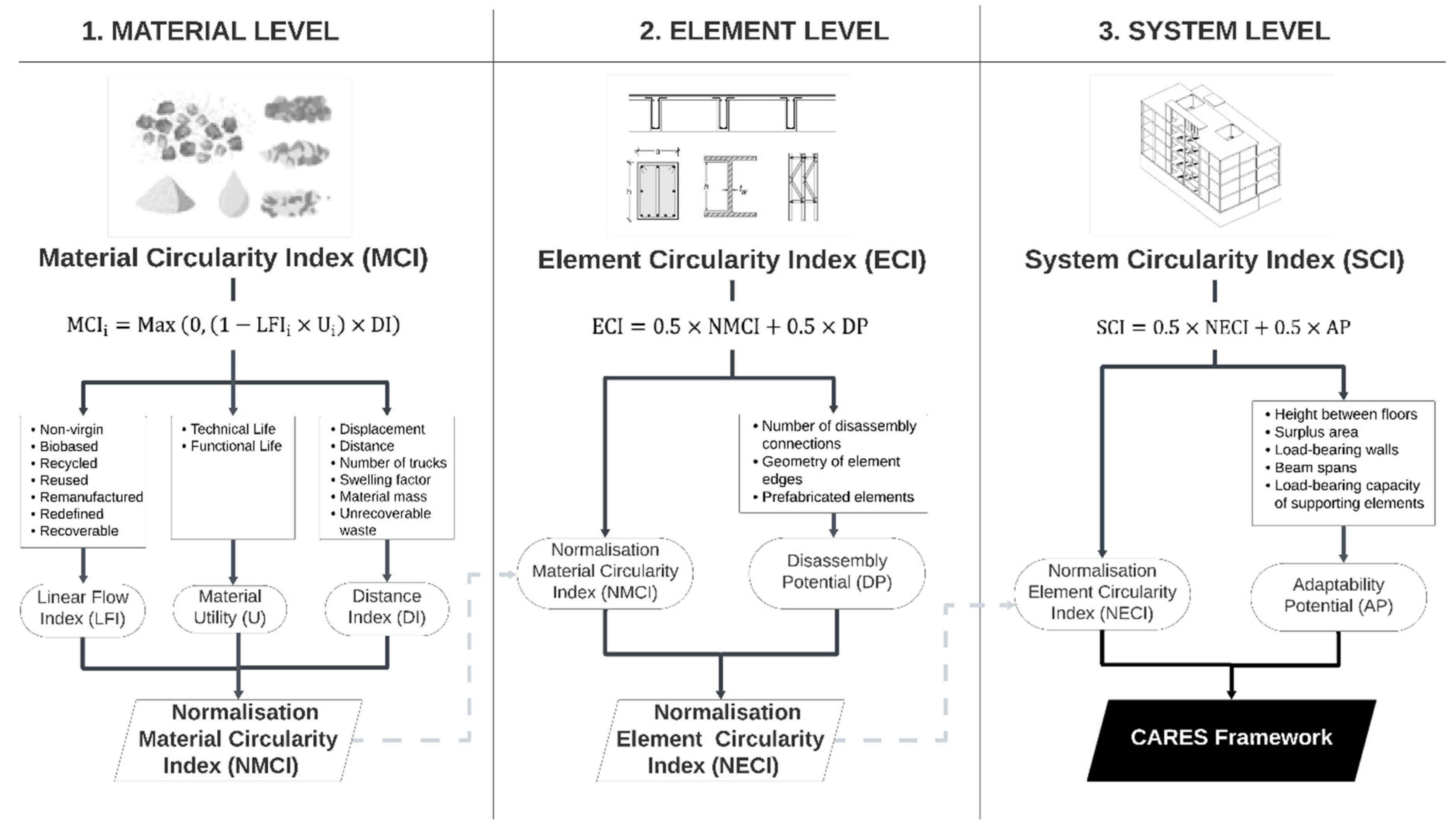

2. Materials and Methods

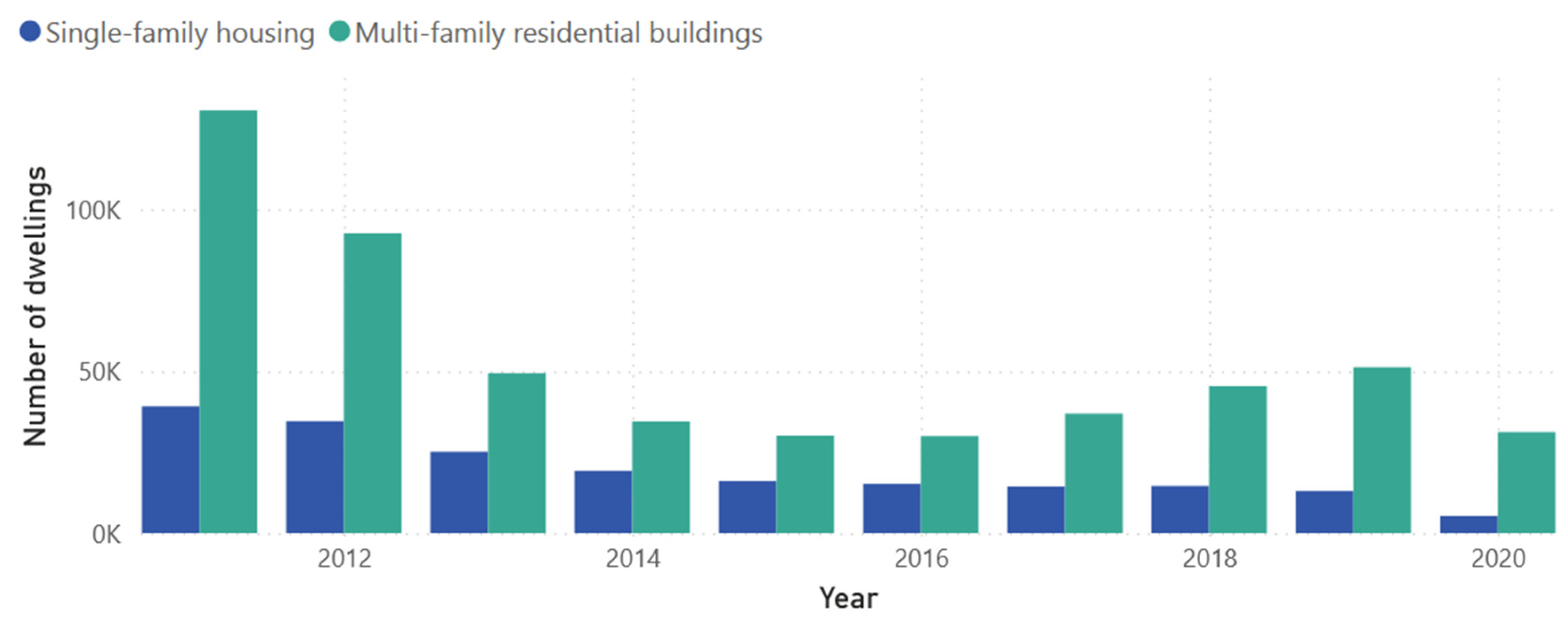

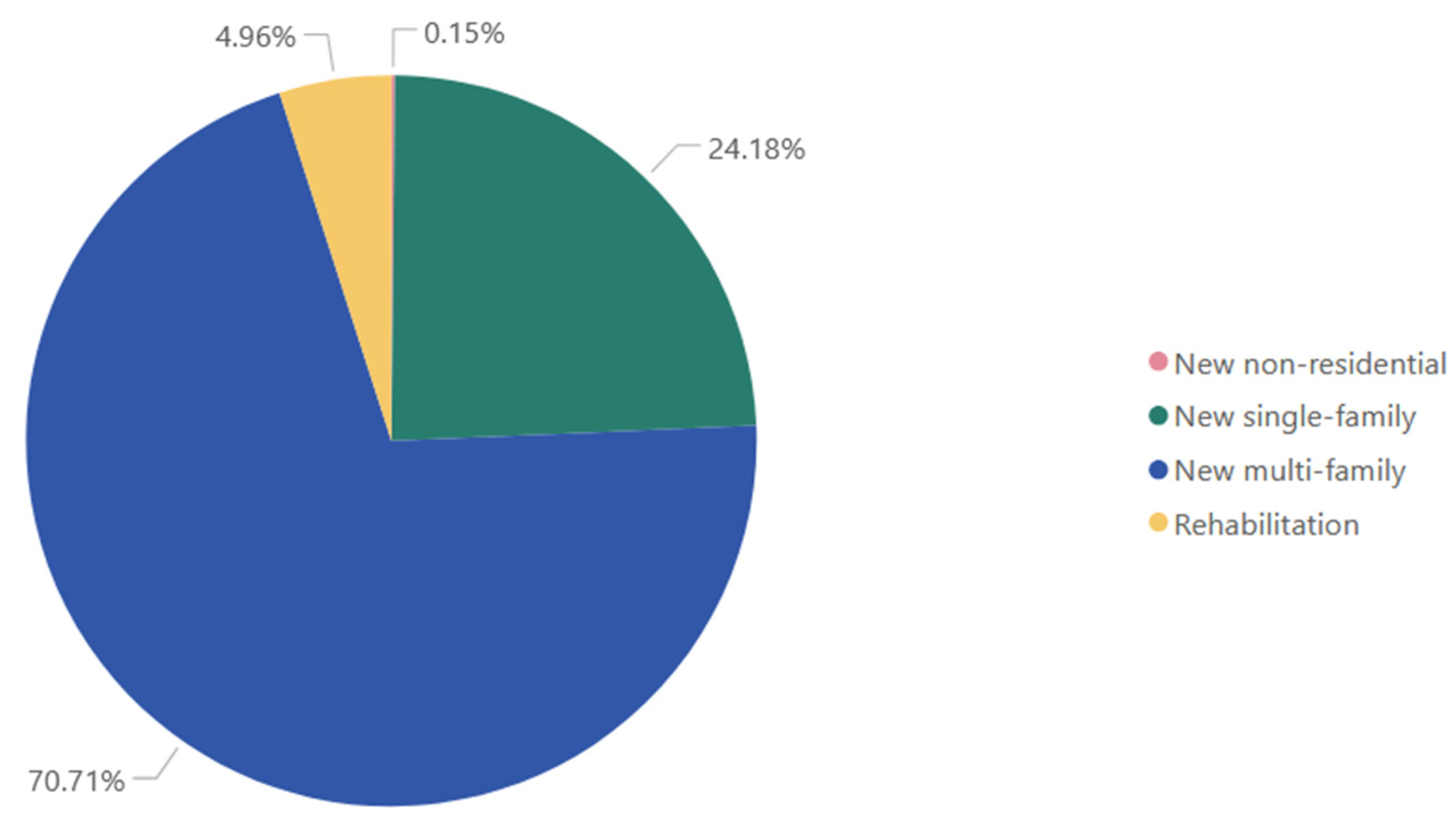

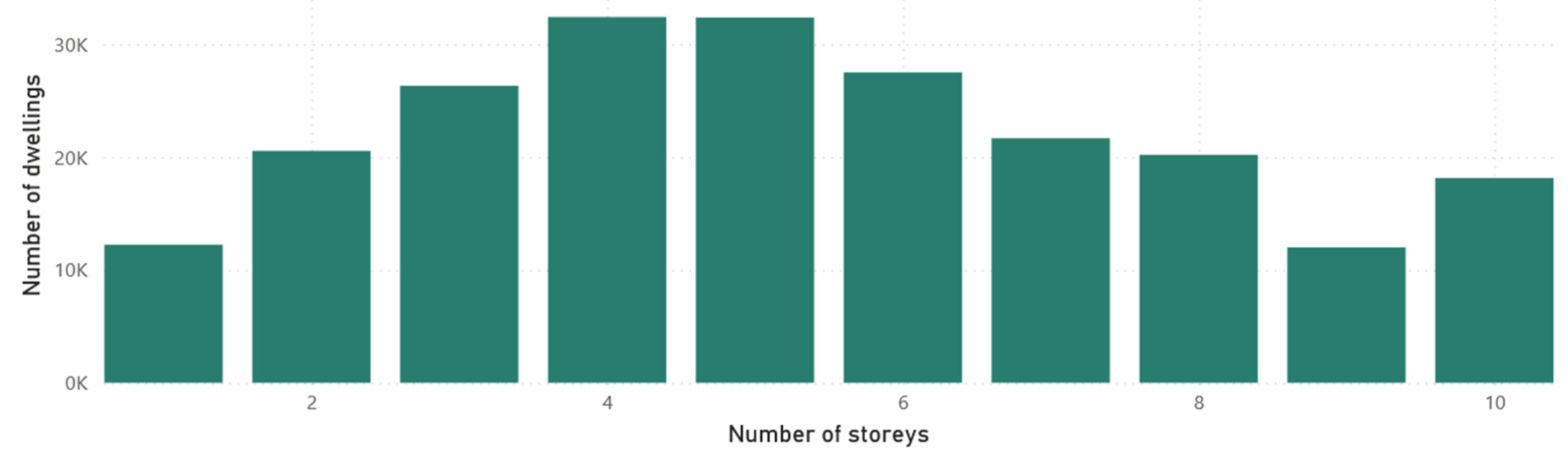

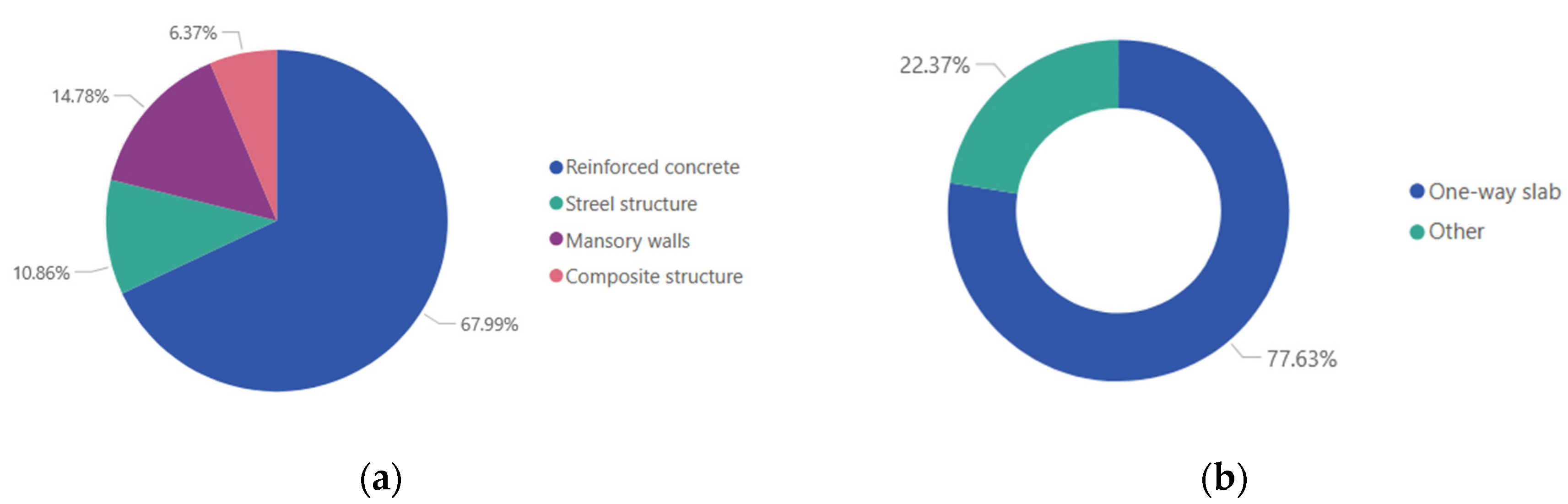

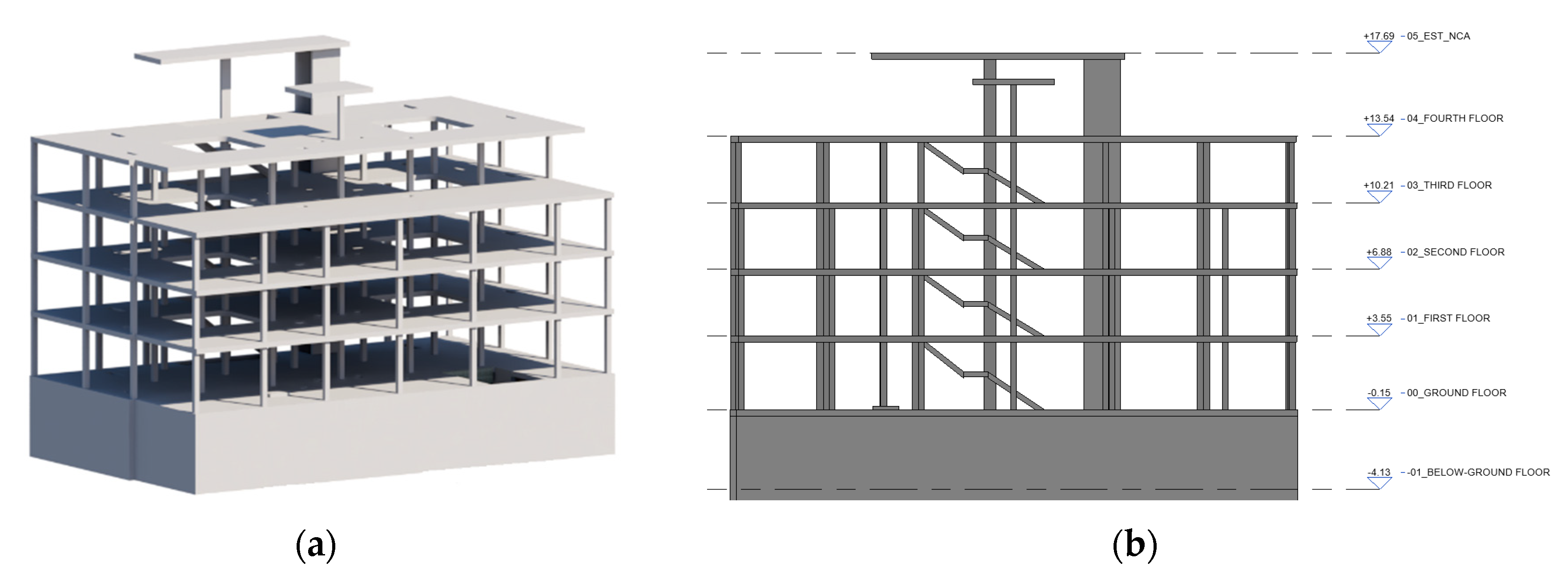

3. Characterisation of the Multi-Family Building Model

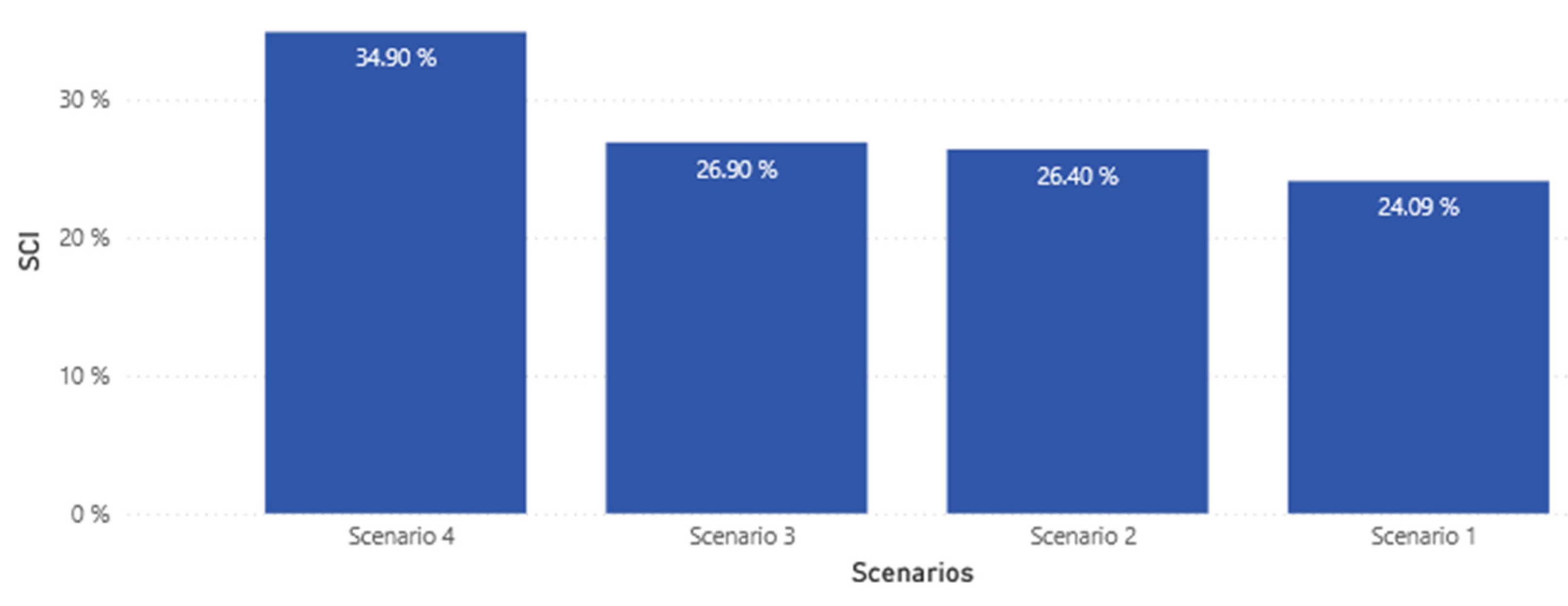

4. Circularity Assessment of Each Scenario

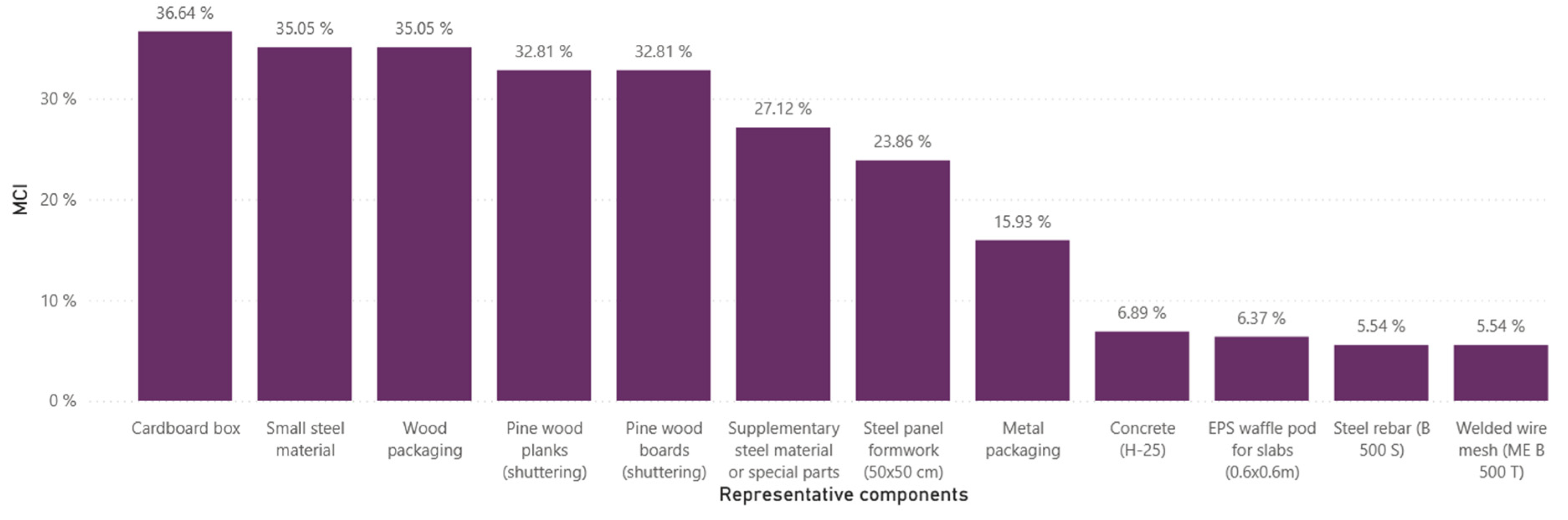

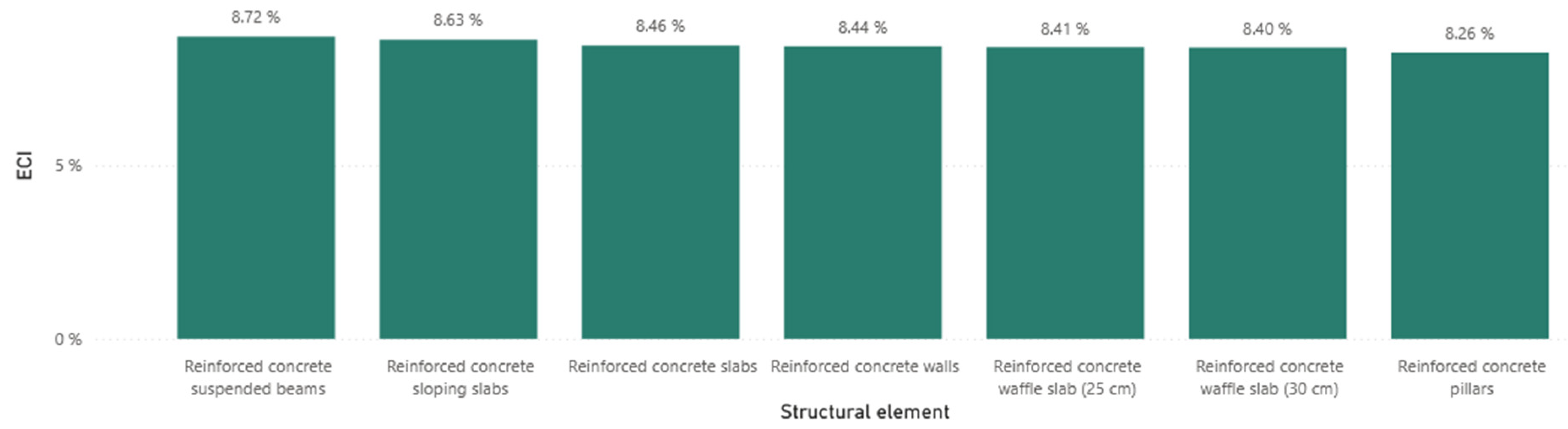

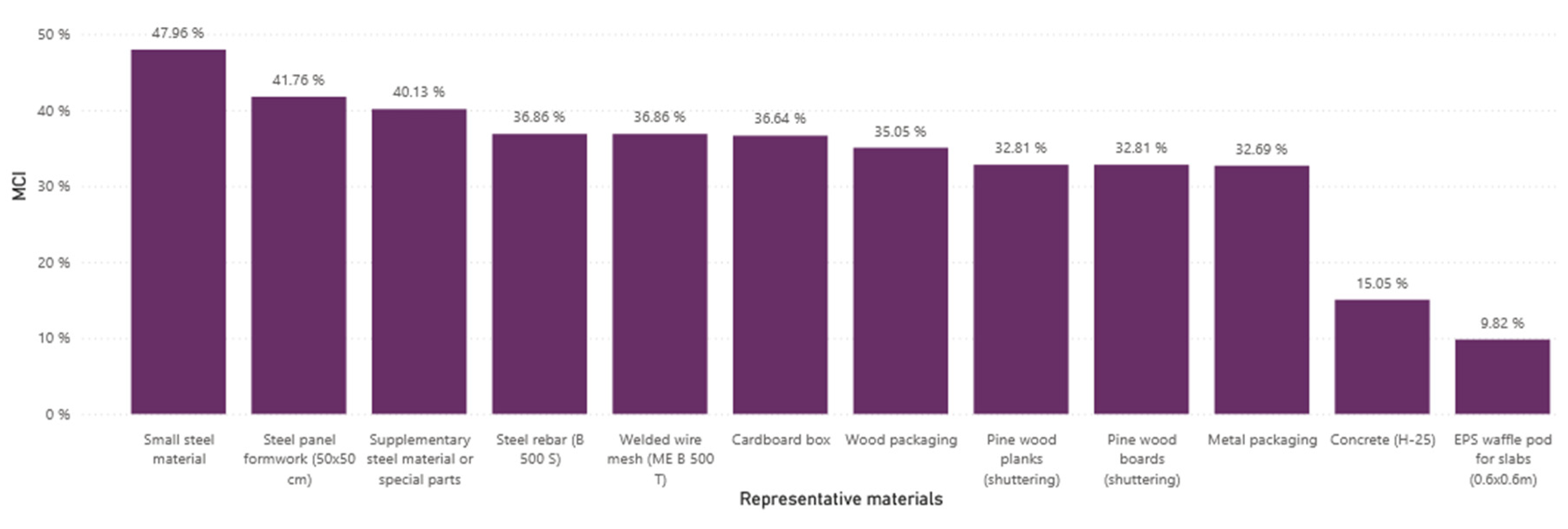

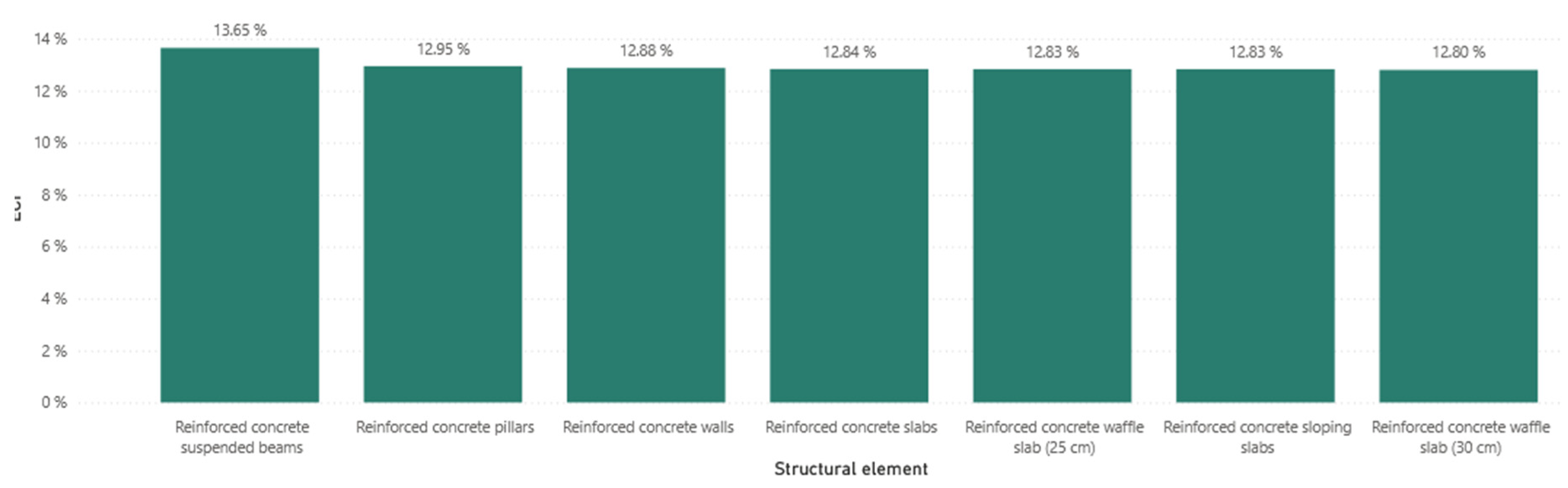

4.1. Scenario 1: Maintaining Material Linearity Throughout Its Lifespan

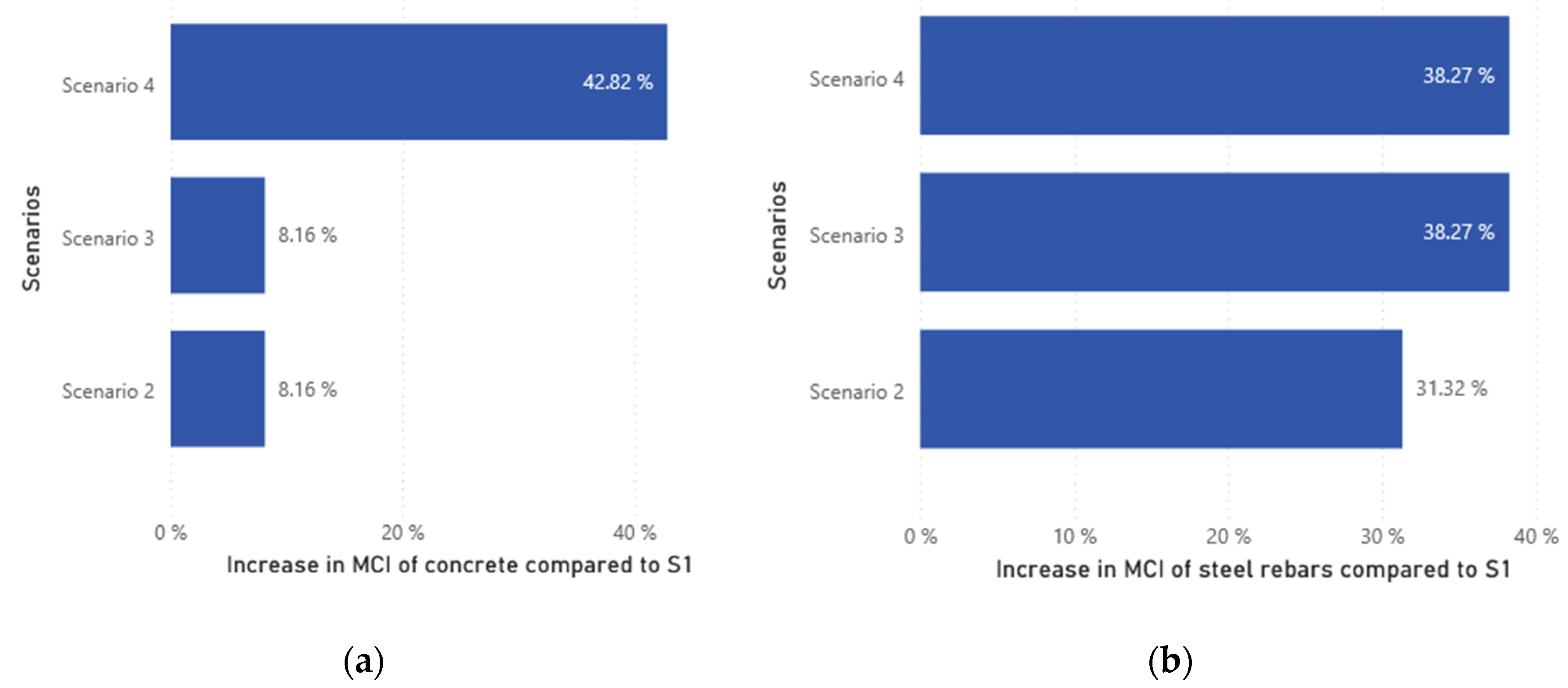

4.2. Scenario 2: Implementing Circularity Strategies at the EOL

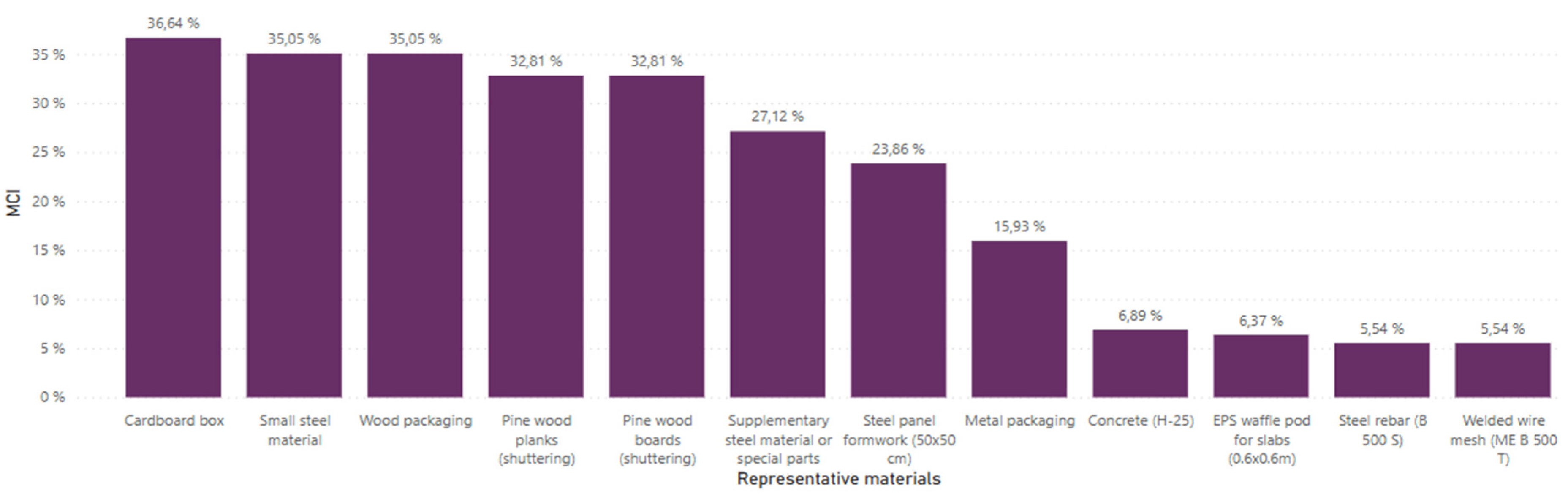

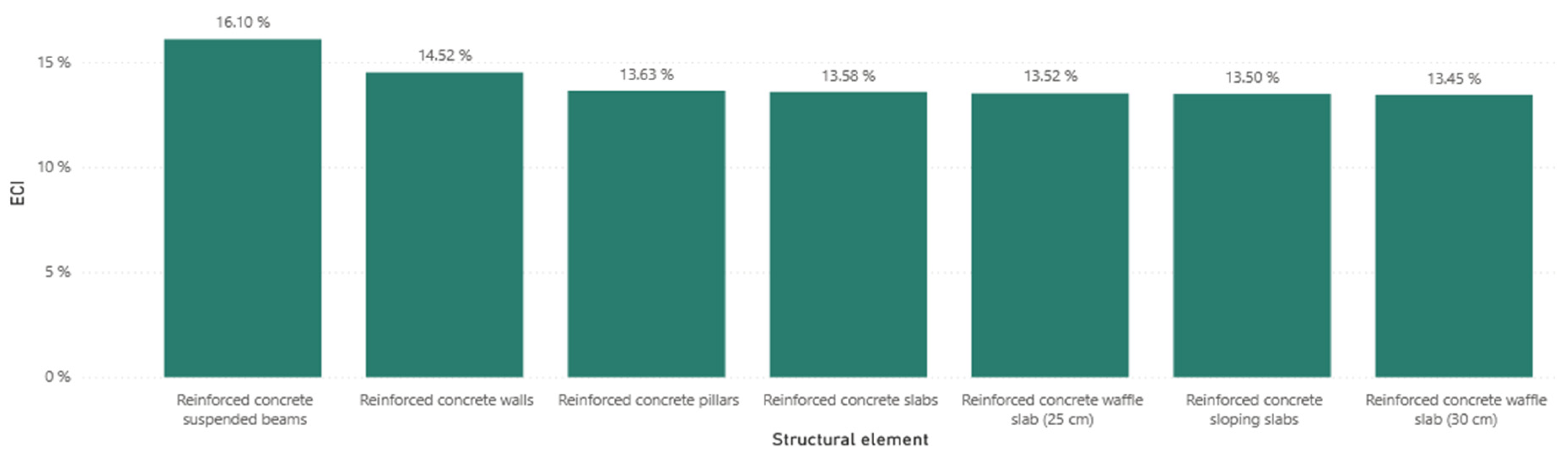

4.3. Scenario 3: Considering Circularity Strategies for All Materials, Excluding Concrete, Throughout the Entire Life Cycle

4.4. Scenario 4: Incorporating Circularity Strategies for All Materials, Including Concrete, Throughout the Entire Life Cycle

5. Discussions and Future Research

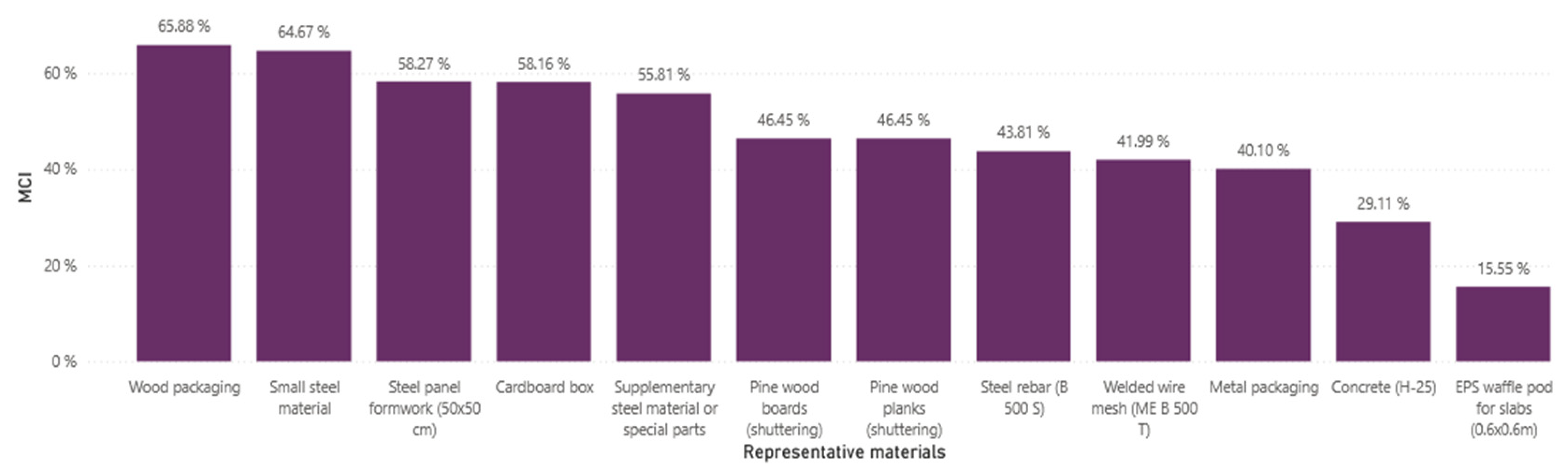

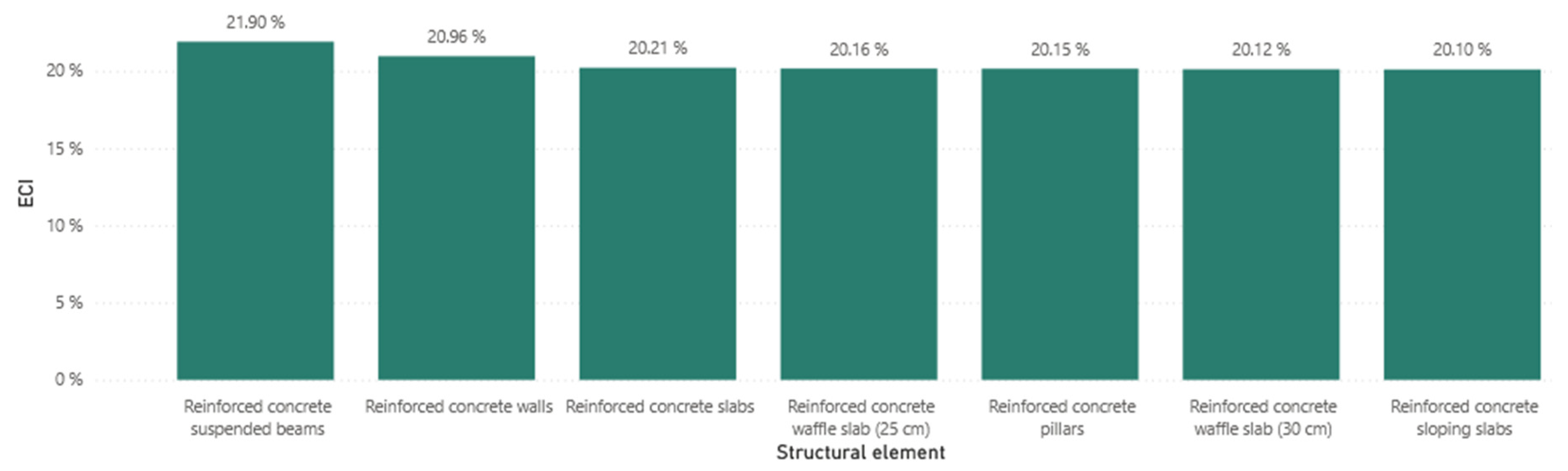

5.1. Impact of Material Circularity Strategies at All Levels in Each Scenario

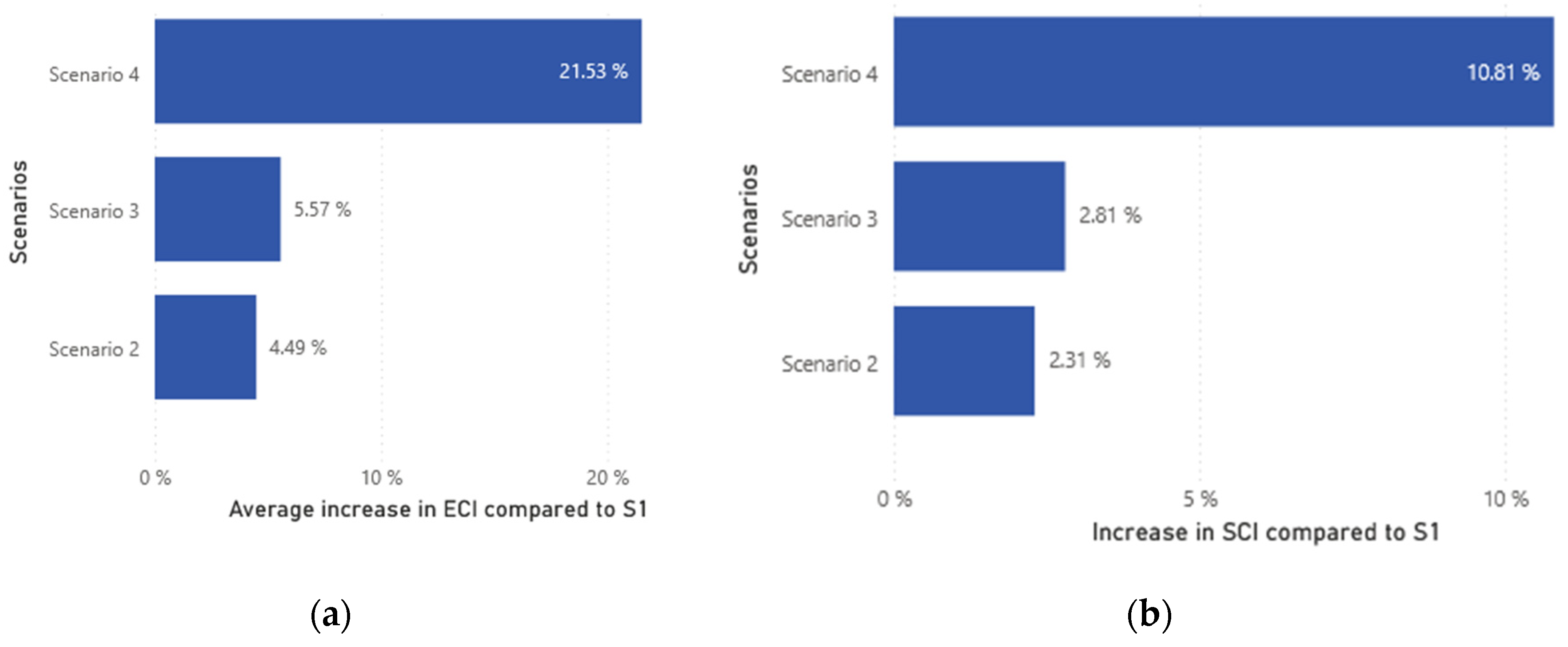

5.2. Implications of Each Scenario at the Macro Level

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Adaptability Potential |

| CARES-F | Circularity Assessment Method for Residential Structures (CARES Framework) |

| CDW | Construction and Demolition Waste |

| CE | Circular Economy |

| CMU | Circular Material Use |

| CPM | Compressible Packaging Model |

| DfA | Design for Adaptability |

| DfC | Design for Circularity |

| DfD | Design for Disassembly |

| DI | Distance Index |

| DMC | Domestic Material Consumption |

| DP | Disassembly Potential |

| EC | European Commission |

| ECI | Element Circularity Index |

| EEEC | CE Spanish Strategy |

| EOL | End Of Life |

| EU | European Union |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| INE | National Institute of Statistics (acronym in Spanish) |

| MCI | Material Circularity Index |

| MITMA | Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility (acronym in Spanish) |

| NAC | Natural Aggregate Concrete |

| NCA | Natural Coarse Aggregate |

| NFA | Natural Fine Aggregate |

| RA | Recycled Aggregate |

| RAC | Recycled Aggregate Concrete |

| RCA | Recycled Coarse Aggregate |

| RPI | Resource Productivity Indicator |

| S1 | Scenario 1 |

| S2 | Scenario 2 |

| S3 | Scenario 3 |

| S4 | Scenario 4 |

| SCI | System Circularity Index |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SP | Superplasticiser |

References

- Neupane, R.P.; Devi, N.R.; Imjai, T.; Rajput, A.; Noguchi, T. Cutting-Edge Techniques and Environmental Insights in Recycled Concrete Aggregate Production: A Comprehensive Review. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Advances 2025, 25, 200241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcradv.2024.200241.

- Scrivener, K.L. Options for the Future of Cement. Indian Concrete Journal 2014, 88, 11–21.

- Developments in the Formulation and Reinforcement of Concrete; Mindess, S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing series in civil and structural engineering; Second edition.; Woodhead Publishing: Duxford, United Kingdom is an imprint of Elsevier, 2019; ISBN 978-0-08-102616-8.

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Cillari, G.; Ricciardi, P.; Miino, M.C.; Torretta, V.; Rada, E.C.; Abbà, A. The Production of Sustainable Concrete with the Use of Alternative Aggregates: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197903.

- European Commission The European Green Deal Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. A New Circular Economy Action Plan For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; 2020;

- Banjerdpaiboon, A.; Limleamthong, P. Assessment of National Circular Economy Performance Using Super-Efficiency Dual Data Envelopment Analysis and Malmquist Productivity Index: Case Study of 27 European Countries. Heliyon 2023, 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16584.

- Vásquez-Cabrera, A.; Montes, M.V.; Llatas, C. Meta-Analyses of Available Circular Assessment Methods: An Approach to the Spanish Building Sector. In Proceedings of the I Bienal de Investigación en Arquitectura (I BIAUS 2024); Sevilla, 2024.

- Eurostat Circular Economy - Material Flows Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Circular_economy_-_material_flows (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation Circular Economy Introduction Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- ISO/DIS 59004 Circular Economy – Terminology, Principles and Guidance for Implementation; 2024.

- Arranz, C.F.A.; Arroyabe, M.F. Institutional Theory and Circular Economy Business Models: The Case of the European Union and the Role of Consumption Policies. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 340, 117906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117906.

- Gardetti, M.A. 1 - Introduction and the Concept of Circular Economy. In Circular Economy in Textiles and Apparel; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; The Textile Institute Book Series; Woodhead Publishing, 2019; pp. 1–11 ISBN 978-0-08-102630-4.

- Bragança, L.; Griffiths, P.; Askar, R.; Salles, A.; Ungureanu, V.; Tsikaloudaki, K.; Bajare, D.; Zsembinszki, G.; Cvetkovska, M. Circular Economy Design and Management in the Built Environment: A Critical Review of the State of the Art; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; ISBN 978-3-031-73489-2.

- International Energy Agency Cement Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/industry/cement (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Demirbas, A.; Demirbas, M.F. Biomass and Wastes: Upgrading Alternative Fuels. Energy Sources 2003, 25, 317–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/00908310390142352.

- Singh, R.P.; Vanapalli, K.R.; Jadda, K.; Mohanty, B. Durability Assessment of Fly Ash, GGBS, and Silica Fume Based Geopolymer Concrete with Recycled Aggregates against Acid and Sulfate Attack. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 82, 108354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108354.

- V. Zhang, L.; Nehdi, M.L.; Suleiman, A.R.; Allaf, M.M.; Gan, M.; Marani, A.; Tuyan, M.; Bacteria, C.C. Crack Self-Healing in Bio-Green Concrete. Compos. Pt. B-Eng. 2021, 227, 109397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109397.

- Sangadji, S. Can Self-Healing Mechanism Helps Concrete Structures Sustainable? In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Sustainable Civil Engineering Structures and Construction Materials - Sustainable Structures for Future Generations (SCESCM); Tim, T.C., Ueda, T., Mueller, H.S., Eds.; Elsevier Science Bv: Amsterdam, 2017; Vol. 171, pp. 238–249.

- Tziviloglou, E.; Pan, Z.; Jonkers, H.M.; Schlangen, E. Bio-Based Self-Healing Mortar: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Journal of Advanced Concrete Technology 2017, 15, 536–543. https://doi.org/10.3151/jact.15.536.

- Regin, J.J.; Ilanthalir, A.; Shyni, R.L. Optimizing Lightweight Concrete with Coconut Shell Aggregates for High Strength and Sustainability. Glob. Nest. J. 2024, 26, 06214. https://doi.org/10.30955/gnj.006214.

- Pacheco, J.; Doniak, L.; Carvalho, M.; Helene, P. The Paradox of High Performance Concrete Used for Reducing Environmental Impact and Sustainability Increase. In Proceedings of the II INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON CONCRETE SUSTAINABILITY - ICCS16; Galvez, J.C., DeCea, A.A., FernandezOrdonez, D., Sakai, K., Reyes, E., Casati, M.J., Enfedaque, A., Alberti, M.G., DeLaFuente, A., Eds.; Int Center Numerical Methods Engineering: 08034 Barcelona, 2016; pp. 442–453.

- Xargay, H.; Folino, P.; Sambataro, L.; Etse, G. Temperature Effects on Failure Behavior of Self-Compacting High Strength Plain and Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 723–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.137.

- Lim, S.G.; Tay, Y.W.D.; Paul, S.C.; Lee, J.; Amr, I.T.; Fadhel, B.A.; Jamal, A.; Al-Khowaiter, A.O.; Tan, M.J. Carbon Capture and Sequestration with In-Situ CO2 and Steam Integrated 3D Concrete Printing. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccst.2024.100306.

- Kline, J.; Kline, C. CO2 Capture from Cement Manufacture and Reuse in Concrete. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE-IAS/PCA Cement Industry Technical Conference; IEEE: New York, 2018.

- Kim, S.; Park, C. Durability and Mechanical Characteristics of Blast-Furnace Slag Based Activated Carbon-Capturing Concrete with Respect to Cement Content. Appl. Sci.-Basel 2020, 10, 2083. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10062083.

- Folino, P.; Xargay, H. Recycled Aggregate Concrete - Mechanical Behavior under Uniaxial and Triaxial Compression. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 56, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.01.073.

- Babalola, O.E.; Awoyera, P.O.; Tran, M.T.; Le, D.-H.; Olalusi, O.B.; Viloria, A.; Ovallos-Gazabon, D. Mechanical and Durability Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete with Ternary Binder System and Optimized Mix Proportion. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2020, 9, 6521–6532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.04.038.

- Vahidi, A.; Mostaani, A.; Teklay Gebremariam, A.; Di Maio, F.; Rem, P. Feasibility of Utilizing Recycled Coarse Aggregates in Commercial Concrete Production. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 474, 143578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143578.

- Dosho, Y. Development of a Sustainable Concrete Waste Recycling System: -Application of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Produced by Aggregate Replacing Method-. ACT 2007, 5, 27–42. https://doi.org/10.3151/jact.5.27.

- Xiao, J.; Li, L.; Shen, L.; Poon, C.S. Compressive Behaviour of Recycled Aggregate Concrete under Impact Loading. Cement and Concrete Research 2015, 71, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.01.014.

- Schneider, M.; Romer, M.; Tschudin, M.; Bolio, H. Sustainable Cement Production—Present and Future. Cement and Concrete Research 2011, 41, 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.03.019.

- Fischer, C.; Werge, M.; Reichel, A. Present Recycling Levels of Municipal Waste and Construction & Demolition Waste in the EU; EU as a Recycling Society; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, 2009; pp. 1–73;.

- In European Aggregates Association A Sustainable Industry for a Sustainable Europe—Annual Review 2017–2018; European Aggregates Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; 34. European Aggregates Association A Sustainable Industry for a Sustainable Europe—Annual Review 2017–2018; European Aggregates Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2018;

- Kazmi, S.M.S.; Munir, M.J.; Wu, Y.-F.; Patnaikuni, I.; Zhou, Y.; Xing, F. Influence of Different Treatment Methods on the Mechanical Behavior of Recycled Aggregate Concrete: A Comparative Study. Cement and Concrete Composites 2019, 104, 103398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2019.103398.

- Hou, S.; Duan, Z.; Xiao, J.; Li, L.; Bai, Y. Effect of Moisture Condition and Brick Content in Recycled Coarse Aggregate on Rheological Properties of Fresh Concrete. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 35, 102075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.102075.

- Neupane, R.P.; Imjai, T.; Makul, N.; Garcia, R.; Kim, B.; Chaudhary, S. Use of Recycled Aggregate Concrete in Structural Members: A Review Focused on Southeast Asia. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 2023, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2270029.

- Zaetang, Y.; Sata, V.; Wongsa, A.; Chindaprasirt, P. Properties of Pervious Concrete Containing Recycled Concrete Block Aggregate and Recycled Concrete Aggregate. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 111, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.060.

- Chakradhara Rao, M. Properties of Recycled Aggregate and Recycled Aggregate Concrete: Effect of Parent Concrete. Asian J Civ Eng 2018, 19, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-018-0011-x.

- Rahal, K.N.; Alrefaei, Y.T. Shear Strength of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Beams Containing Stirrups. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 191, 866–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.10.023.

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Soomro, M.; Evangelista, A.C.J. A Review of Recycled Aggregate in Concrete Applications (2000–2017). Construction and Building Materials 2018, 172, 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.03.240.

- Salgado, F.D.A.; Silva, F.D.A. Recycled Aggregates from Construction and Demolition Waste towards an Application on Structural Concrete: A Review. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 52, 104452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104452.

- Tam, V.W.Y.; Tam, L.; Le, K.N. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Concrete Recycling Decision-Making and Implementation in Construction Industry. Waste Management 2010, 30, 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2009.09.044.

- DIN 4226-100 Aggregates for Concrete and Mortar—Part 100: Recycled Aggregates. Deutsches Institut Fur Normung 2002.

- EN DIN 12620 Aggregates for Concrete; Berlin, Germany, 2008.

- Ministerio de Transportes y Movilidad Sostenible Capítulo 8. Estructuras de hormigón. Propiedades tecnológicas de los materiales. In Código Estructural; 2021.

- UNE-EN 12620 Áridos para hormigón; Madrid, España, 2009.

- Morató, J.; Jiménez, L.M.; Calleros-Islas, A.; De la Cruz, J.L.; Díaz, L.D.; Martínez, J.; P.-Lagüela, E.; Penagos, G.; Pernas, J.J.; Rovira, S.; et al. Situación y Evolución de La Economía Circular En España; Fundación COTEC: Madrid, España, 2021;

- Morató, J.; Jiménez, L.M.; Penagos, G.; Sánchez, O.L.; Villanueva, B.; de la Cruz, J.L.; Martí, C.; Lagüela, E.P.; Pereira, S.; Pernas, J.J.; et al. Situación y Evolución de La Economía Circular En España; Fundación COTEC: Madrid, España, 2023;

- Eurostat Resource Productivity Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/CEI_PC030 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Eurostat Circular Material Use Rate Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/sdg_12_41/default/map?lang=en (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Giorgi, S.; Lavagna, M.; Wang, K.; Osmani, M.; Liu, G.; Campioli, A. Drivers and Barriers towards Circular Economy in the Building Sector: Stakeholder Interviews and Analysis of Five European Countries Policies and Practices. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 336, 130395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130395.

- AlJaber, A.; Martinez-Vazquez, P.; Baniotopoulos, C. Barriers and Enablers to the Adoption of Circular Economy Concept in the Building Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112778.

- Cruz Rios, F.; Grau, D.; Bilec, M. Barriers and Enablers to Circular Building Design in the US: An Empirical Study. J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 2021, 147, 04021117. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002109.

- Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility Statistics of Buildings Constructed (2022) Available online: https://apps.fomento.gob.es/BoletinOnline/?nivel=2&orden=10000000 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Diaz-Lopez, C.; Carpio, M.; Martin-Morales, M.; Zamorano, M. Defining Strategies to Adopt Level(s) for Bringing Buildings into the Circular Economy. A Case Study of Spain. J. Clean Prod. 2021, 287, 125048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125048.

- Gonzalez-Vallejo, P. Evaluación Económica y Ambiental de la Construcción de Edificios residenciales. Aplicación a España y Chile. PhD Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, 2017.

- Llatas, C. A Model for Quantifying Construction Waste in Projects According to the European Waste List. Waste Management 2011, 31, 1261–1276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2011.01.023.

- Llatas, C.; Osmani, M. Development and Validation of a Building Design Waste Reduction Model. Waste Management 2016, 56, 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.05.026.

- Quiñones, R.; Llatas, C.; Montes, M.V.; Cortés, I. Quantification of Construction Waste in Early Design Stages Using Bim-Based Tool. Recycling 2022, 7, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling7050063.

- Llatas, C.; Quiñones, R.; Bizcocho, N. Environmental Impact Assessment of Construction Waste Recycling versus Disposal Scenarios Using an LCA-BIM Tool during the Design Stage. Recycling 2022, 7, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling7060082.

- Rodriguez Serrano, A.A.; Alvarez, S.P. Life Cycle Assessment in Building: A Case Study on the Energy and Emissions Impact Related to the Choice of Housing Typologies and Construction Process in Spain. Sustainability 2016, 8, 287. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030287.

- Castrillon-Mendoza, R.; Rey-Hernandez, J.M.; Castrillon-Mendoza, L.; Rey-Martinez, F.J. Sustainable Building Tool by Energy Baseline: Case Study. Appl. Sci.-Basel 2024, 14, 9403. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14209403.

- Mercader-Moyano, P.; Anaya-Duran, P.; Romero-Cortes, A. Eco-Efficient Ventilated Facades Based on Circular Economy for Residential Buildings as an Improvement of Energy Conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 7266. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14217266.

- Lopez-Ochoa, L.M.; Sagredo-Blanco, E.; Las-Heras-Casas, J.; Garcia-Lozano, C. Towards Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings in Cold Rural Mediterranean Zones: The Case of La Rioja (Spain). BUILDINGS-BASEL 2023, 13, 680. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13030680.

- Balletto, G.; Borruso, G.; Mei, G.; Milesi, A. Strategic Circular Economy in Construction: Case Study in Sardinia, Italy. J. Urban Plann. Dev. 2021, 147, 05021034. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)UP.1943-5444.0000715.

- Proyecto GEAR Guía Española de áridos reciclados procedentes de RCD; 2nd ed.; 2012;

- Tošić, N.; Torrenti, J.M.; Sedran, T.; Ignjatović, I. Toward a Codified Design of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Structures: Background for the New fib Model Code 2020 and Eurocode 2 . Structural Concrete 2021, 22, 2916–2938. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202000512.

- EMVISESA Empresa Municipal de la Vivienda de Sevilla. Available online: https://www.emvisesa.org/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- In Ihobe; LKS Ingeniería; Ecoingenium Guía para el uso de materiales reciclados en construcción; Ihobe, Sociedad Pública de Gestión Ambiental: Bilbao, 2016; 70. Ihobe; LKS Ingeniería; Ecoingenium Guía para el uso de materiales reciclados en construcción; Ihobe, Sociedad Pública de Gestión Ambiental: Bilbao, 2016;

- Vásquez-Cabrera, A.; Montes, M.V.; Llatas, C. CARES Framework: A Circularity Assessment Method for Residential Building Structures. Sustainability 2025, 17, 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020443.

- INE Population and Housing Census 2021 Available online: https://www.ine.es/Censo2021/Inicio.do?L=0 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility Statistics of Buildings Constructed (2003 - 2019) Available online: https://www.transportes.gob.es/informacion-para-el-ciudadano/informacion-estadistica/construccion/construccion-de-edificios/publicaciones-de-construccion-de-edificios-licencias-municipales-de-obra (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- González-Vallejo, P.; Solís-Guzmán, J.; Llácer, R.; Marrero, M. La construcción de edificios residenciales en España en el período 2007-2010 y su impacto según el indicador Huella Ecológica. Inf. constr. 2015, 67, e111. https://doi.org/10.3989/ic.14.017.

- IMPARGO CargoApps 2.0 TMS para transportistas y empresas de transporte Available online: https://company.impargo.de/es/tms-cargo-app-2.0 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-1999-1826 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- .

- Emblem, H.J. Packaging and Environmental Sustainability. In Packaging Technology; Emblem, A., Emblem, H., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing, 2012; pp. 65–86 ISBN 978-1-84569-665-8.

- Sander, K.; Schilling, S.; Lüskow, H.; Gonser, J.; Schwedtje, A.; Küchen, V. Review of the European List of Waste; European Commission in cooperation with Ökopol GmbH and ARGUS GmbH, 2008;

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/cei_srm020_esmsip2.htm (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- In EGGA Acero galvanizado y construcción sostenible; European General Galvanizers Association: Madrid, España, 2021; 81. EGGA Acero galvanizado y construcción sostenible; European General Galvanizers Association: Madrid, España, 2021;

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/cei_srm010_esmsip2.htm (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- 2022; 83. Plastics Europe The CE of Plastics; Madrid, España, 2022;

- 2020; 84. EuRIC aisbl Metal Recycling Factsheet; Belgium, EU, 2020;

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/env_waspac_esms.htm (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Döhler, N.; Wellenreuther, C.; Wolf, A. Market dynamics of biodegradable bio-based plastics: Projections and linkages to European policies. EFB Bioeconomy Journal 2022, 2, 100028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioeco.2022.100028.

- Amario, M.; Rangel, C.S.; Pepe, M.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Optimization of Normal and High Strength Recycled Aggregate Concrete Mixtures by Using Packing Model. Cement and Concrete Composites 2017, 84, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.08.016.

- Vaz, A.; Shehata, I.; Shehata, L.; Gomes, R.B. Comportamento de Vigas Reforçadas Sob Ação de Carregamento Cíclico. Revista IBRACON de Estruturas e Materiais 2017, 10, 1245–1272.

- In WRAP Designing out Waste: A Design Team Guide for Buildings; Waste and Resources Action Program: Oxon, 2023; 89. WRAP Designing out Waste: A Design Team Guide for Buildings; Waste and Resources Action Program: Oxon, 2023;

- Durmisevic, E. Transformable Building Structures. Design for Disassembly as a Way to Introduce Sustainable Engineering to Building Design & Construction. PhD Thesis, Technische Universiteit Delft: Delf, 2006.

- Dodd, N.; Donatello, S.; Cordella, M.; Perez, Z. Indicador 2.4 de Level(s): Diseño para la deconstrucción; European Commission, 2021;

- Geraedts, R. FLEX 4.0, A Practical Instrument to Assess the Adaptive Capacity of Buildings. Energy Procedia 2016, 96, 568–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2016.09.102.

- Dodd, N.; Donatello, S.; Cordella, M. Indicador 2.3 de Level(s): Diseño con fines de adaptabilidad y reforma; European Commission, 2021;

- Yao, Y.; Hong, B. Evolution of Recycled Concrete Research: A Data-Driven Scientometric Review. Low-carbon Materials and Green Construction 2024, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44242-024-00047-5.

- Subdirección General de Economía Circular Estrategia Española de Economía Circular. España Circular 2030; Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (MITECO): Madrid, 2018;

| LoW1 Code and Description | Representative material | Participation mass ratio | |

| 17 01 01 | Concrete | Concrete (H-25) | 93.33% |

| 17 04 05 | Iron and steel | Steel rebar (B 500 S) | 2.82% |

| 17 04 05 | Iron and steel | Small steel material | 1.08% |

| 15 01 11* | Metallic packaging containing a hazardous solid porous matrix | Metallic packaging | 0.55% |

| 17 04 05 | Iron and steel | Supplementary steel material or special parts | 0.54% |

| 17 02 01 | Wood | Pinewood planks (shuttering) | 0.45% |

| 17 02 01 | Wood | Pinewood boards (shuttering) | 0.43% |

| 17 04 05 | Iron and steel | Welded wire mesh (ME B 500 T) | 0.13% |

| 17 06 04 | Insulation materials | EPS waffle pod for slabs (0.6x0.6m) | 0.11% |

| 15 01 03 | Wooden packaging | Wooden packaging | 0.10% |

| 17 04 05 | Iron and steel | Steel panel formwork (50x50 cm) | 0.10% |

| 15 01 01 | Paper and cardboard packaging | Cardboard box | 0.10% |

| LoW Code and Description | Title | Author | Year | |

| 170101 | Concrete | Spanish Guide to Recycled Aggregates from RCD | GEAR [67] | 2012 |

| 170405 | Iron and steel | Guideline for recycled materials reuse in construction Trade in Recyclable Raw Materials (database) Galvanised steel and sustainable construction (report) |

Ihobe [70] Eurostat [80] EGGA [81] |

2016 2022 2021 |

| 170201 | Wood | Contribution of Recycled Materials to Raw Materials Demand (database) | Eurostat [82] | 2020 |

| 170203 | Plastic | The CE of plastics (report) Packaging and environmental sustainability |

Plastics Europe [83] Emblem et al. [78] |

2022 2012 |

| 150111* | Metallic packaging | Metal Recycling Factsheet | EuRIC AISBL [84] | 2022 |

| 150103 | Wooden packaging | Packaging Waste by Waste Management Operations (database) Trade in Recyclable Raw Materials (database) |

Eurostat [85] | 2023 |

| 150101 | Paper and cardboard packaging | Eurostat [80] | 2022 | |

| Composition | Properties | ||

| Cement | 266.4 kg/m3 | Compressive strength | 25 MPa |

| Free water | 170.0 kg/m3 | % of RCA | 20 % |

| Natural Fine Aggregate (NFA) | 844.4 kg/m3 | Effective water-cement ratio | 0.64 |

| Natural Coarse Aggregate (NCA) | 803.0 kg/m3 | ||

| Recycled Coarse Aggregate (RCA) | 195.6 kg/m3 | ||

| Superplasticiser (SP) | 2.7 kg/m3 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).