Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

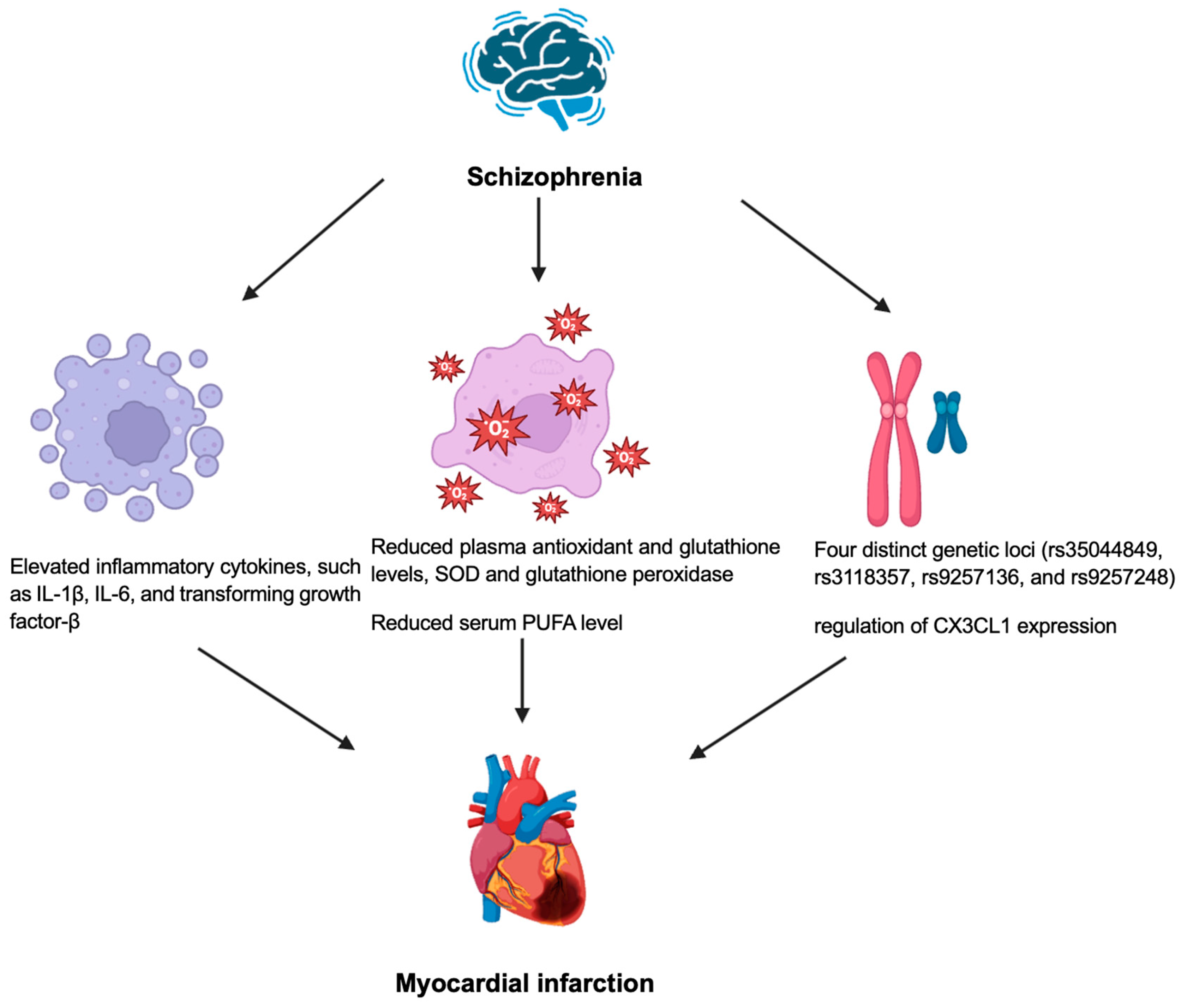

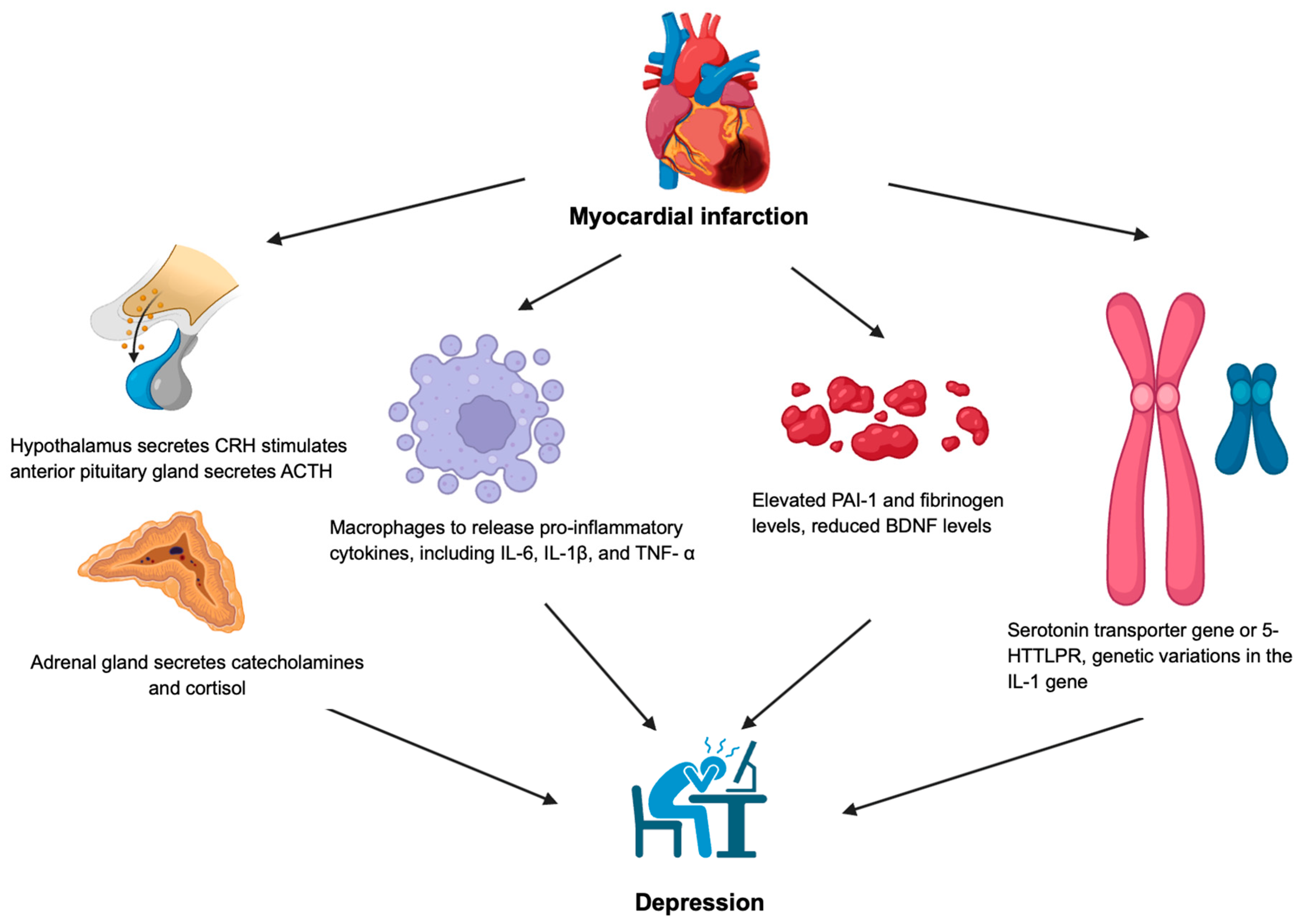

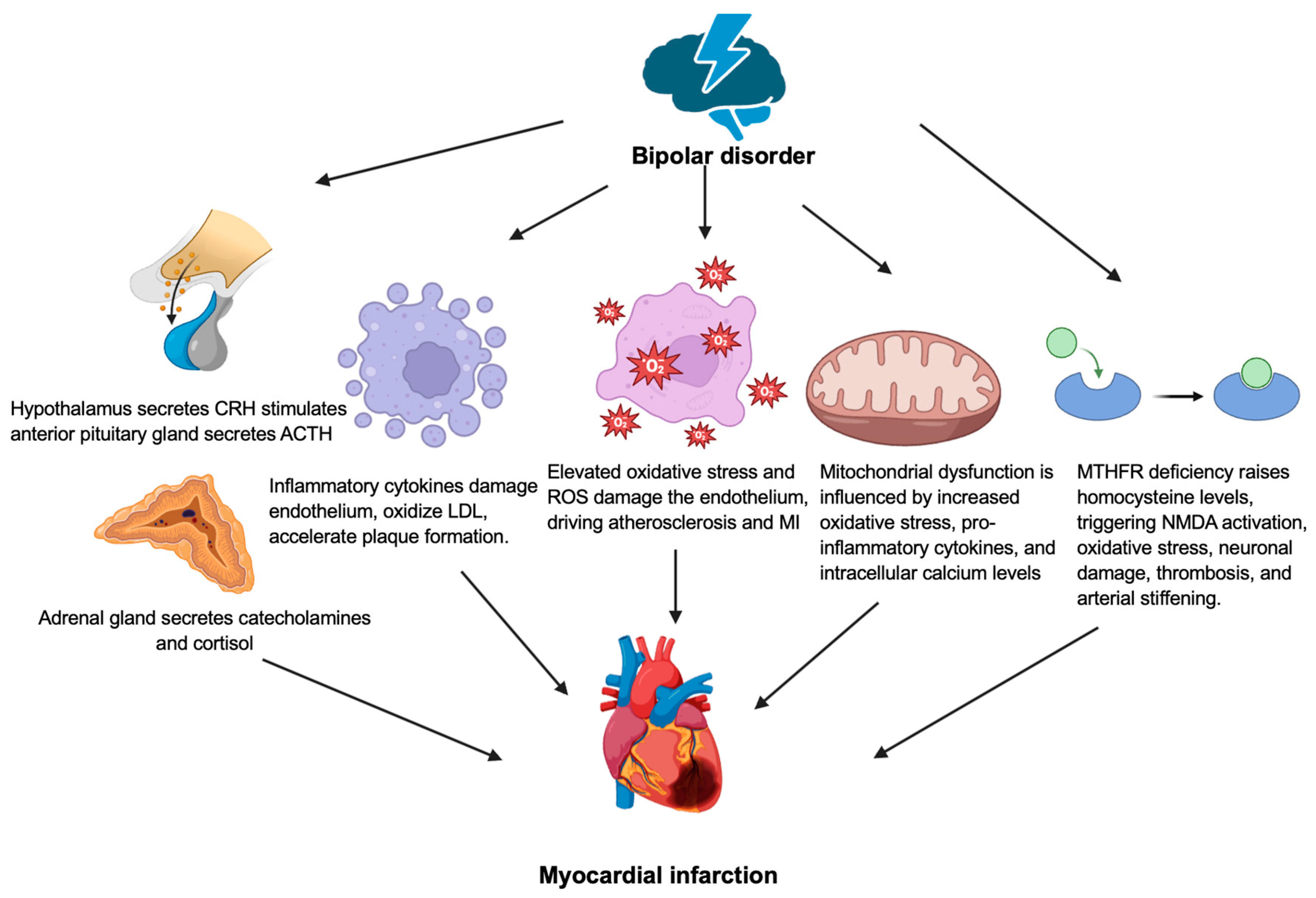

There is increasing evidence demonstrating that psychiatric conditions elevate the risk of developing accelerated atherosclerosis and early-onset cardiovascular disease (CVD) including myocardial infarction (MI). Several mechanisms contribute to this observation. Dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system and hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in these patients contribute to the development of (MI). Additionally, patients with underlying psychiatric disorders often have abnormal levels of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which can lead to early vascular damage and subsequent atherosclerosis. Elevated PAI-1 levels, reduced tPA activity, and decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), influenced by coagulation and inflammation, may contribute to depression and its link to MI. Oxidative stress, marked by increased reactive species and impaired antioxidant defenses, is associated with cellular damage and has been consistently implicated in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, potentially contributing to myocardial infarction. Finally, molecular genetic studies have indicated that psychiatric disorders and myocardial infarction may share potential pleiotropic genes. The interplay between psychiatric conditions and myocardial infarction underscores the importance of integrated care approaches to manage both mental and physical health.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Anxiety Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder

3. Bipolar Disorder

4. Schizophrenia

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BNDF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CRH | Corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| EPA | Eicosapentanoate |

| HMGB1 | High-mobility group box 1 |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal |

| HSP | Heat shock proteins |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| MTHFR | Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

| MPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| MCU | Mitochondrial calcium uniporter |

| NCX | Na⁺/Ca²⁺ exchanger |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| NSTEMI | Non-ST elevation MI |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| STEMI | ST elevation myocardial infarction |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| tPA | tissue plasminogen activator |

References

- Kumar, M.; Nayak, P.K. Psychological sequelae of myocardial infarction. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 95, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grippo, A.J.; Johnson, A.K. Stress, depression and cardiovascular dysregulation: a review of neurobiological mechanisms and the integration of research from preclinical disease models. Stress 2009, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringen, P.A.; Engh, J.A.; Birkenaes, A.B.; Dieset, I.; Andreassen, O.A. Increased mortality in schizophrenia due to cardiovascular disease - a non-systematic review of epidemiology, possible causes, and interventions. Front Psychiatry 2014, 5, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, T.M.; Wahlbeck, K.; Hällgren, J.; Westman, J.; Ösby, U.; Alinaghizadeh, H.; Gissler, M.; Nordentoft, M. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One 2013, 8, e67133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.M.; Parretti, H.M.; Pearce, E.; Price, M.J.; Riley, M.; Ryan, R.; Tyldesley-Marshall, N.; Avşar, T.S.; Matthewman, G.; Lee, A.; et al. Temporal trends in associations between severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2022, 19, e1003960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, M.; De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Di Palo, K.; Munir, H.; Music, S.; Piña, I.; Ringen Petter, A. Severe Mental Illness and Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2022, 80, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugathasan, P.; Johansen, M.B.; Jensen, M.B.; Aagaard, J.; Nielsen, R.E.; Jensen, S.E. Coronary Artery Calcification and Mortality Risk in Patients With Severe Mental Illness. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2019, 12, e008236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Vancampfort, D. The intriguing relationship between coronary heart disease and mental disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2018, 20, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.P.; Chien, W.C.; Cheng, W.T.; Chung, C.H.; Cheng, S.M.; Tzeng, W.C. Risk of anxiety and depressive disorders in patients with myocardial infarction: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016, 95, e4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roest, A.M.; Heideveld, A.; Martens, E.J.; de Jonge, P.; Denollet, J. Symptom dimensions of anxiety following myocardial infarction: associations with depressive symptoms and prognosis. Health Psychol 2014, 33, 1468–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrels, E.; Kainth, T.; Silva, B.; Yadav, G.; Gill, G.; Salehi, M.; Gunturu, S. Pathophysiological mechanisms of post-myocardial infarction depression: a narrative review. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1225794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkowska, A.; Rynkiewicz, A.; Wdowczyk, J.; Landowski, J. Morning and afternoon serum cortisol level in patients with post-myocardial infarction depression. Cardiol J 2019, 26, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjögren, E.; Leanderson, P.; Kristenson, M. Diurnal saliva cortisol levels and relations to psychosocial factors in a population sample of middle-aged Swedish men and women. Int J Behav Med 2006, 13, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nat Rev Cardiol 2014, 11, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M.; Hansson, G.K. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature 2011, 473, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konsman, J.P.; Luheshi, G.N.; Bluthé, R.M.; Dantzer, R. The vagus nerve mediates behavioural depression, but not fever, in response to peripheral immune signals; a functional anatomical analysis. Eur J Neurosci 2000, 12, 4434–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Yaffe, K.; Newman, A.B.; Simonsick, E.M.; Rubin, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Harris, T.; Pahor, M. Inflammatory markers and depressed mood in older persons: results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. Biol Psychiatry 2003, 54, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Bosmans, E.; De Jongh, R.; Kenis, G.; Vandoolaeghe, E.; Neels, H. Increased serum IL-6 and IL-1 receptor antagonist concentrations in major depression and treatment resistant depression. Cytokine 1997, 9, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raison, C.L.; Capuron, L.; Miller, A.H. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol 2006, 27, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, J.C.; Lawson, M.A.; André, C.; Moreau, M.; Lestage, J.; Castanon, N.; Kelley, K.W.; Dantzer, R. Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Mol Psychiatry 2009, 14, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R.; O'Connor, J.C.; Lawson, M.A.; Kelley, K.W. Inflammation-associated depression: from serotonin to kynurenine. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 36, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.J. Role of tissue-type plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in psychological stress and depression. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 113258–113268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, S.J.; Hong, C.J.; Liou, Y.J.; Yu, Y.W.; Chen, T.J. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene is associated with major depression and antidepressant treatment response. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2008, 18, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiser, F.; Conrad, R.; Imbierowicz, K.; Meier, C.; Liedtke, R.; Klingmüller, D.; Oldenburg, J.; Harbrecht, U. Coagulation activation and fibrinolysis impairment are reduced in patients with anxiety and depression when medicated with serotonergic antidepressants. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2011, 65, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Lu, N.; Yue, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhi, X.; Zhang, D.; Yuan, Y. The serum protein levels of the tPA-BDNF pathway are implicated in depression and antidepressant treatment. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karege, F.; Perret, G.; Bondolfi, G.; Schwald, M.; Bertschy, G.; Aubry, J.M. Decreased serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in major depressed patients. Psychiatry Res 2002, 109, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a biomarker for mood disorders: an historical overview and future directions. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010, 64, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.; Nestler, E.J. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 2008, 455, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, M.; Pagliusi, S.R.; Hohn, A.; Leibrock, J.; Barde, Y.A. Regional distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the adult mouse brain. Embo j 1990, 9, 2459–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C.; McCaffery, J.; Ali, S.; Whooley, M.A. Association of a serotonin transporter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) with depression, perceived stress, and norepinephrine in patients with coronary disease: the Heart and Soul Study. Am J Psychiatry 2007, 164, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schins, A.; Honig, A.; Crijns, H.; Baur, L.; Hamulyák, K. Increased coronary events in depressed cardiovascular patients: 5-HT2A receptor as missing link? Psychosom Med 2003, 65, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatani, D.; Sato, H.; Sakata, Y.; Shiotani, I.; Kinjo, K.; Mizuno, H.; Shimizu, M.; Ito, H.; Koretsune, Y.; Hirayama, A.; et al. Influence of serotonin transporter gene polymorphism on depressive symptoms and new cardiac events after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2005, 150, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujak, M.; Frangogiannis, N.G. The role of IL-1 in the pathogenesis of heart disease. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2009, 57, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Singh, B.; Varnika, F.; Fredrick, F.C.; Meda, A.K.R.; Aggarwal, K.; Jain, R. Linking hearts and minds: understanding the cardiovascular impact of bipolar disorder. Future Cardiol 2024, 20, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rovere, M.T.; Porta, A.; Schwartz, P.J. Autonomic Control of the Heart and Its Clinical Impact. A Personal Perspective. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weperen, V.Y.H.; Ripplinger, C.M.; Vaseghi, M. Autonomic control of ventricular function in health and disease: current state of the art. Clin Auton Res 2023, 33, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.I.; Carnethon, M.R.; Matthews, K.A.; McIntyre, R.S.; Miller, G.E.; Raghuveer, G.; Stoney, C.M.; Wasiak, H.; McCrindle, B.W. Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder Predispose Youth to Accelerated Atherosclerosis and Early Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 132, 965–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.L.; Minassian, A.; Paulus, M.P.; Geyer, M.A.; Perry, W. Heart rate variability in bipolar mania and schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 2010, 44, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, S.; Gast, K.B.; de Mutsert, R.; Swenne, C.A.; Jukema, J.W.; Middeldorp, S.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Dekkers, O.M. Heart rate variability and first cardiovascular event in populations without known cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis and dose–response meta-regression. EP Europace 2013, 15, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatkhullina, A.R.; Peshkova, I.O.; Koltsova, E.K. The Role of Cytokines in the Development of Atherosclerosis. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2016, 81, 1358–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckert, A.V.; Valvassori, S.S.; Moretti, M.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Quevedo, J. Role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Neurochem Res 2010, 35, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.I. Bipolar Disorder and the Vascular System: Mechanisms and New Prevention Opportunities. Can J Cardiol 2017, 33, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checa, J.; Aran, J.M. Reactive Oxygen Species: Drivers of Physiological and Pathological Processes. J Inflamm Res 2020, 13, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.; Cheng, H.; Wang, L. Ferroptosis and Lipid Metabolism in Acute Myocardial Infarction. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2024, 25, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.; Walder, K.; McGee, S.L.; Dean, O.M.; Tye, S.J.; Maes, M.; Berk, M. A model of the mitochondrial basis of bipolar disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017, 74, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantó, C.; Menzies, K.J.; Auwerx, J. NAD(+) Metabolism and the Control of Energy Homeostasis: A Balancing Act between Mitochondria and the Nucleus. Cell Metab 2015, 22, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Resendiz, S.; Prunier, F.; Girao, H.; Dorn, G.; Hausenloy, D.J. Targeting mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins for cardioprotection. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24, 6571–6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefani, D.; Raffaello, A.; Teardo, E.; Szabò, I.; Rizzuto, R. A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 2011, 476, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salagre, E.; Vizuete, A.F.; Leite, M.; Brownstein, D.J.; McGuinness, A.; Jacka, F.; Dodd, S.; Stubbs, B.; Köhler, C.A.; Vieta, E.; et al. Homocysteine as a peripheral biomarker in bipolar disorder: A meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2017, 43, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.; Alam, S.F. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J 2015, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Mason, A.M.; Carter, P.; Burgess, S.; Larsson, S.C. Homocysteine, B vitamins, and cardiovascular disease: a Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med 2021, 19, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namazi, M.R.; Feily, A. Homocysteine may accelerate skin aging: a new chapter in the biology of skin senescence? J Am Acad Dermatol 2011, 64, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.C.; Vincenzi, B.; Andrea, N.V.; Ulloa, M.; Copeland, P.M. Pathophysiological mechanisms of increased cardiometabolic risk in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheslack-Postava, K.; Brown, A.S. Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: A decade of further progress. Schizophrenia Research 2022, 247, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond, G.; Lançon, C.; Korchia, T.; Auquier, P.; Boyer, L. The Role of Inflammation in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kesteren, C.F.; Gremmels, H.; de Witte, L.D.; Hol, E.M.; Van Gool, A.R.; Falkai, P.G.; Kahn, R.S.; Sommer, I.E. Immune involvement in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis on postmortem brain studies. Transl Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monji, A.; Kato, T.; Kanba, S. Cytokines and schizophrenia: Microglia hypothesis of schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2009, 63, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.J.; Buckley, P.; Seabolt, W.; Mellor, A.; Kirkpatrick, B. Meta-analysis of cytokine alterations in schizophrenia: clinical status and antipsychotic effects. Biol Psychiatry 2011, 70, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haybar, H.; Bandar, B.; Torfi, E.; Mohebbi, A.; Saki, N. Cytokines and their role in cardiovascular diseases. Cytokine 2023, 169, 156261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.J.; Rogers, J.C.; Katshu, M.; Liddle, P.F.; Upthegrove, R. Oxidative Stress and the Pathophysiology and Symptom Profile of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 703452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aladağ, N.; Asoğlu, R.; Ozdemir, M.; Asoğlu, E.; Derin, A.R.; Demir, C.; Demir, H. Oxidants and antioxidants in myocardial infarction (MI): Investigation of ischemia modified albumin, malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase and catalase in individuals diagnosed with ST elevated myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-STEMI (NSTEMI). J Med Biochem 2021, 40, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, D.K.; Refsum, H.; Andreassen, O.A.; Bentsen, H. A five-year follow-up study of antioxidants, oxidative stress and polyunsaturated fatty acids in schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2019, 31, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentsen, H.; Landrø, N.I. Neurocognitive effects of an omega-3 fatty acid and vitamins E+C in schizophrenia: A randomised controlled trial. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 2018, 136, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, S.; Fukuda, D.; Aihara, K.I.; Akaike, M.; Shimabukuro, M.; Sata, M. n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Promising Nutrients for Preventing Cardiovascular Disease. J Atheroscler Thromb 2017, 24, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Chen, C.Y.; Li, Z.; Martin, A.R.; Bryois, J.; Ma, X.; Gaspar, H.; Ikeda, M.; Benyamin, B.; Brown, B.C.; et al. Comparative genetic architectures of schizophrenia in East Asian and European populations. Nat Genet 2019, 51, 1670–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Jiang, C. Unraveling the heart-brain axis: shared genetic mechanisms in cardiovascular diseases and Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia 2024, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, S.; Spandidos, D. Chemokines and atherosclerosis: focus on the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2013, 34, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jiang, L.; Bian, C.; Liang, Y.; Xing, R.; Yishakea, M.; Dong, J. Role of CX3CL1 in Diseases. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2016, 64, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).