1. Introduction

The real estate sector is increasingly recognizing the importance of sustainability and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors in property valuation and investment decisions. This shift is driven by growing environmental concerns, regulatory pressures, and changing tenant preferences. In recent years, the European Central Bank (ECB) has emphasized the significance of climate risk in financial stability, further highlighting the need for sustainable real estate practices [1].

Background on ESG and Real Estate

ESG criteria are becoming essential in financial decision-making, with regulatory developments like the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) that significantly expands the scope and detail of sustainability reporting requirements for companies [2].

CSRD has increased transparency in corporate sustainability reporting, while credit rating agencies incorporate these risks into their assessments, highlighting the growing importance of aligning financial profitability with long-term sustainability indicators [3].

This study focuses on Class A office buildings in Madrid's Central Business District (CBD), analyzing the impact of ESG certifications on various aspects of real estate performance [4]. By examining multiple properties with different renovation and CAPEX investment levels, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of how ESG certifications influence valuation, market perception, and financial performance.

Figure 1.

Madrid geographical distribution and building selection in the CBD.

Figure 1.

Madrid geographical distribution and building selection in the CBD.

The research employs a multi-criteria decision analysis methodology to evaluate the complex interplay of factors affecting ESG-certified buildings. This approach allows for a nuanced examination of the benefits and challenges associated with sustainable real estate practices in Spain compared to other studies done in the European office market [5].

Research Objectives

Our study is particularly timely given the ECB's recent announcements regarding climate risk and the increasing emphasis on carbon-neutral buildings [6]. By analyzing the relationship between ESG certifications and key performance indicators, we seek to provide valuable insights for investors, developers, and policymakers in the real estate sector.

To provide the right scoring of different parameters involved in the research, the study suggests a Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) analysis based on input from different experts in the industry [7].

Previous research has predominantly concentrated on evaluating the influence of building certifications on investor interest in property acquisition [8]. In contrast, this study proposes a comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to assessment, offering a more robust and nuanced understanding of the factors influencing investment decision.

2. Literature Review

ESG Factors and Climate Risk in Real Estate

The integration of ESG factors into real estate valuation and performance assessment has been recently published by Contact et al [9], which provides a comprehensive study on climate and real estate, highlighting the growing importance of ESG considerations in the broader European context [10]. To mention the most relevant topics:

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for ESG factors play an important role in determining the value of real estate assets [11]. These KPIs cover areas like energy efficiency, carbon footprint, water and waste management, and the well-being of tenants. Studies have looked into how these ESG-related KPIs are connected to financial measures like capital expenditures (CAPEX) and rental income [12].

Climate risk presents a complex, long-term governance challenge for organizations [13], requiring strategic responses due to its ambiguous nature and potential to significantly impact business strategies and opportunities [14]. Climate change risk assessment involves balancing potential adverse effects on human welfare and ecosystems against the costs of mitigation and adaptation, with uncertainty playing a crucial role in shaping decision-making processes at individual, governmental, and corporate levels [15].

Studies have also demonstrated that higher corporate social responsibility can mitigate negative climate risk impacts on firm performance [16], underscoring the importance of ESG considerations in risk management strategies [17]. The 'Social' dimension of ESG plays a crucial role in asset appraisal, particularly with the contemporary emphasis on health, well-being, and inclusivity in real estate assets. The WELL Building Standard (2023) exemplifies how prioritizing health-oriented spaces can positively affect tenant productivity and satisfaction [18]. This paradigm shift towards social well-being within the ESG framework necessitates a holistic approach that encompasses design elements, indoor environmental quality, and wellness amenities.

European Central Bank Directives and Climate Risk

The ECB has increasingly emphasized the importance of climate risk in financial stability [19]. The ECB has directed banks to incorporate climate-related and environmental risks into their risk management frameworks [20], which has significant implications for real estate financing and valuation, particularly for properties with strong ESG credentials [21].

Regional and policy impacts of ECB climate risk directives and local regulations on property market dynamics [22] and investor behavior have been assessed, with studies highlighting how policy changes may affect valuation metrics [23]. This regulatory focus has led to increased research on the impact of climate risk on real estate valuation [24].

Most recent publication from global organizations like RICS and BBP among others [25], have mentioned Net Zero Carbon (NZC) [26], Green Building Certifications, Energy Management, CO2/m2, renewable energy use, Physical Climate Risk, Water Usage Efficiency, and Waste Management Efficiency as part of their priorities [27].

Various studies in Europe have highlighted that the building sector is a key contributor to wealth and jobs. They point out the importance of energy use and emissions, especially in Southern Europe, where effective adaptation measures are needed [28], with a special focus on Portugal [29]. These studies also examine how climate change affects energy consumption in buildings, particularly in hot and humid areas [30], across European cities [31], and on real estate assets throughout the continent [32].

Not only in Europe. From a US perspective, there is also evidence of this correlation [33] and [34]. However, specific regional approaches and local measurements are suggested to ensure proper mitigation [35].

Below table shows different KPIs with recommended relevance.

Table 1.

Comprehensive set of KPIs for assessing office buildings in Europe. Source: own study.

Table 1.

Comprehensive set of KPIs for assessing office buildings in Europe. Source: own study.

| KPI |

Relevance |

Justification |

| CO2 emissions (kgCO2e/m2/year) |

Highest |

Directly measures climate impact; crucial for climate change assessment; aligns with EU carbon reduction goals |

| Energy consumption (kWh/m2/year) |

Highest |

Strongly linked to CO2 emissions and building efficiency; fundamental component of EPCs [36] |

| Renewable energy production (onsite) |

Very High |

Contributes to reducing carbon footprint and energy independence; aligns with EU's push for nearly zero-energy buildings |

| Green building certifications (e.g., BREEAM, LEED) |

Very High |

Comprehensive measure of overall building sustainability; BREEAM dominant in UK/Europe, LEED gaining ground |

| Physical climate risk analysis |

High |

Important for assessing long-term climate change impacts on the property; crucial for long-term valuation and risk management |

| Energy rating (EPC) |

High |

Indicates energy efficiency; mandatory in EU for property transactions |

| Water usage efficiency |

Moderate |

Key component of occupant health and wellbeing; emphasized in certifications like WELL |

| Waste management and recycling rate |

Moderate |

Important for energy management and occupant comfort; increasingly relevant in EMEA |

| CREM or other pathway analysis |

Lower |

Measures carbon footprint of construction materials/processes, gaining importance in lifecycle assessments [37] |

Multi-Criteria Decision-Making in Real Estate

MCDM methods offer a way to handle complex information, helping people make clear and consistent decisions [38]. These methods are especially helpful when dealing with many different or conflicting factors, or when considering a broad range of qualitative and intangible elements [39].

The complexity of integrating ESG factors and climate risk into real estate decision-making has led to the adoption of MCDM approaches. These methods allow for a more nuanced evaluation of properties, considering various ESG and financial metrics simultaneously.

This literature review demonstrates the growing importance of ESG factors and climate risk considerations in real estate valuation, financing, and performance assessment. It also highlights the need for further research to fully understand and quantify these factors’ impact across different markets and property types.

3. Madrid Office Market Dynamics

Climate risks specific to Madrid have been focused on SDGs [40], but little has developed on the office sector and Madrid’s CBD, evaluating potential impacts on property values due to factors like extreme heat, air pollution, or other risks.

Studies specific to the Madrid office market provide context for our research [41]. Other authors analyzed the evolution of the Madrid office market, highlighting the importance of location, quality, and sustainability in determining property values [42].

Figure 2.

Madrid Districts. Source: own study.

Figure 2.

Madrid Districts. Source: own study.

The literature also emphasizes the need for urban resilience strategies, particularly through green infrastructure policies [43]. These policies can foster resilience by addressing factors such as diversity, governance, and social cohesion. However, implementation faces barriers like financing and political will.

The increasing frequency of extreme climate events presents unprecedented challenges for urban centers like Madrid, necessitating strategic resilience planning within real estate markets. Madrid’s exposure to rising temperatures and periodic heatwaves underscores the need for adaptive infrastructure and building design. This suggests resilience frameworks tailored to urban real estate can mitigate adverse impacts, thus safeguarding property values and tenant safety [44].

Implementing resilience-enhancing strategies such as green roofs, improved insulation, and emergency response protocols can serve as critical defenses against climate risks [45]. Furthermore, integrating resilience measures aligns with broader sustainability and insurance considerations, providing a competitive advantage for developers and investors alike [46]. By preemptively addressing these risks, the Madrid real estate market can ensure its stability and attractiveness amidst the pressures of evolving climate patterns.

4. Multi-Criteria Decision Making in Real Estate

In response to the growing importance of ESG factors in real estate valuation and investment decisions, this study employs a multi-criteria methodology to analyze the impact of ESG certifications on Class A office buildings in Madrid's Central Business District.

The MCDM approach has been successfully applied in various domains, including climate policy [47] and infrastructure assessment [48], demonstrating its efficacy in evaluating complex, multifaceted issues [49].

Our research builds upon the established literature on sustainable real estate practices [50], which has consistently shown that green-certified buildings command rent and price premiums compared to conventional properties [51]. However, this study extends beyond these findings by incorporating a comprehensive analysis of ESG factors, climate risk considerations, and their combined impact on office portfolio performance in a major European urban center [52].

The MCDM framework allows for a nuanced evaluation of multiple criteria, including:

ESG certification impact on property value and performance [53]

Cost-benefit analysis of retrofit strategies and their role in achieving ESG certifications [54]

The influence of ESG certifications on access to financing [55], interest rates, and investment attractiveness [56]

Benchmarking against local and international standards [57].

By engaging diverse stakeholder inputs, our methodology reflects market realities and provides a holistic view of the factors influencing sustainable real estate practices in Madrid [58]. This approach is particularly relevant given the increasing emphasis on ESG reporting and disclosure practices in the real estate sector [59].

While previous studies have examined the impact of green certifications on commercial real estate prices, there remains a gap in understanding how these factors interact with climate risk considerations in the context of a large European city's office portfolio. Our study aims to address this gap by offering insights into the evolving relationship between ESG certifications, climate risk, and office building performance in Madrid [60].

This research contributes to the growing body of literature on sustainable real estate by providing a comprehensive analysis of ESG factors in the Madrid office market. The findings will offer valuable insights for investors, REITs, developers, and policymakers [61], guiding decision-making processes in an increasingly ESG-conscious real estate landscape.

However, very little has been studied on how above research evolved and linked climate risk and office portfolio in a large European city country. Thus this study aims to offer some clarity on the field.

5. Materials and Methods

Research Design

To cover different aspects of how climate risk interacts with real estate, the author suggests a Multi-Criteria Decision-making analysis in Real Estate [62]. This appraisal has been used in many hybrid scenarios [63], and the method has been applied to various aspects of real estate research [64]. Other researchers incorporated multiple criteria, including environmental, social, and economic factors, to evaluate the sustainability of buildings [65].

Similarly, there has been analysis demonstrating the effectiveness of MCDM in addressing complex decision-making problems in real estate and urban planning [66].

The buildings selected for the study are shown in the below figure.

Figure 3.

Madrid CBD with selected projects. Source: own study.

Figure 3.

Madrid CBD with selected projects. Source: own study.

6. MCDM Framework

The MCDM analysis covers 21 office projects in Madrid CBD. Initial selection presents

nE indicators of type E,

nI of type I, and

nA of type A such that:

where “m” is the total number of KPIs (12 indicators in our case). Each KPI has a given score, denoted by:

that for the mixed-use projects, take values from a given internal criteria

1 from 1 to 5, that is:

In our case, with m=12, we assign the following Cj values:

Table 2.

assigned values. Source: own study. Details of the calculation are shown in the Appendix.

Table 2.

assigned values. Source: own study. Details of the calculation are shown in the Appendix.

| |

E |

I |

A1 |

| |

E1 |

E2 |

E3 |

E4 |

I1 |

I2 |

I3 |

I4 |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

| |

Previous experience |

Listed developer / Fin entity |

Professional Property MMT |

Access to subway (distance in m) |

Rent |

Occupancy |

Refurbished |

Grade |

ESG Certification |

Climate risk assessment |

International designer |

Parking ratio |

| Criteria (1-5) |

4 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

The total scoring “T

EIA” for the “m” indicators considered is,

Criteria. Scoring and Weighting Process

An external advisor will be able to rank each of the projects studied, for instance, assigning Cj, from 0 to 10, to each indicator E, I, and A.

Therefore, the criteria for appraisal will be 0 Cj 10.

Appraisal

As per the MCDM analysis, the Total Asset Performance (TAP) for 12 indicators, grouped in three categories, E, I, and A, weighted by Cj criteria, results in:

The analysis done for one of the recent projects in Madrid (Castellana 77) is shown below. An external advisor could assign the following Cj criteria for each of the E, I, and A KPIs:

Table 3.

Cj values (0-10) for

Table 3.

Cj values (0-10) for

| Project \ Indicator |

E1 |

E2 |

E3 |

E4 |

I1 |

I2 |

I3 |

I4 |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

| Castellana 77 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

10 |

2 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

Empirical Results

For the MCDM analysis, all 21 office projects are assessed against the given , evaluated with an external score from 0 to 10.

Table 4.

Office name Cj and parameters for calculation. Source: own study.

Table 4.

Office name Cj and parameters for calculation. Source: own study.

| Project \ Indicator |

CJ |

E1 |

E2 |

E3 |

E4 |

I1 |

I2 |

I3 |

I4 |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

Total |

| Castellana 77 |

7.38 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

10 |

2 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

90 |

| Serrano 47 |

7.33 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

2 |

8 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

8 |

90 |

| Castellana 79 |

7.33 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

86 |

| Pablo Ruiz Picasso 11 |

7.29 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

4 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

90 |

| Claudio Coello 123 |

7.19 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

4 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

90 |

| Castellana 66 |

7.14 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

88 |

| Castellana 259D |

7.10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

2 |

10 |

6 |

8 |

8 |

2 |

10 |

8 |

90 |

| José Ortega y Gasset 29 |

7.10 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

2 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

8 |

8 |

6 |

10 |

4 |

80 |

| Castellana 83-85 |

7.05 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

4 |

86 |

| Serrano 88 |

7.00 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

8 |

10 |

8 |

0 |

4 |

78 |

| Castellana 259B |

6.95 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

10 |

10 |

90 |

| Castellana 41 |

6.95 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

10 |

0 |

6 |

86 |

| Maria de Molina 4 |

6.90 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

2 |

10 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

8 |

0 |

2 |

82 |

| Castellana 95 |

6.81 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

8 |

4 |

10 |

2 |

6 |

10 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

78 |

| Pablo Ruiz Picasso 1 |

6.81 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

10 |

6 |

10 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

80 |

| Velázquez 34 |

6.81 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

10 |

2 |

84 |

| Castellana 43 |

6.62 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

10 |

2 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

0 |

6 |

80 |

| Castellana 259C |

6.57 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

6 |

2 |

10 |

10 |

82 |

| Castellana 35 |

6.48 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

8 |

6 |

10 |

0 |

6 |

6 |

10 |

0 |

8 |

74 |

| Castellana 259A |

6.10 |

10 |

0 |

10 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

10 |

10 |

4 |

2 |

10 |

8 |

76 |

| Castellana 52 |

5.05 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

0 |

4 |

64 |

For this project and m = 21, the max Cj,

will be 90.

Office is 7.38

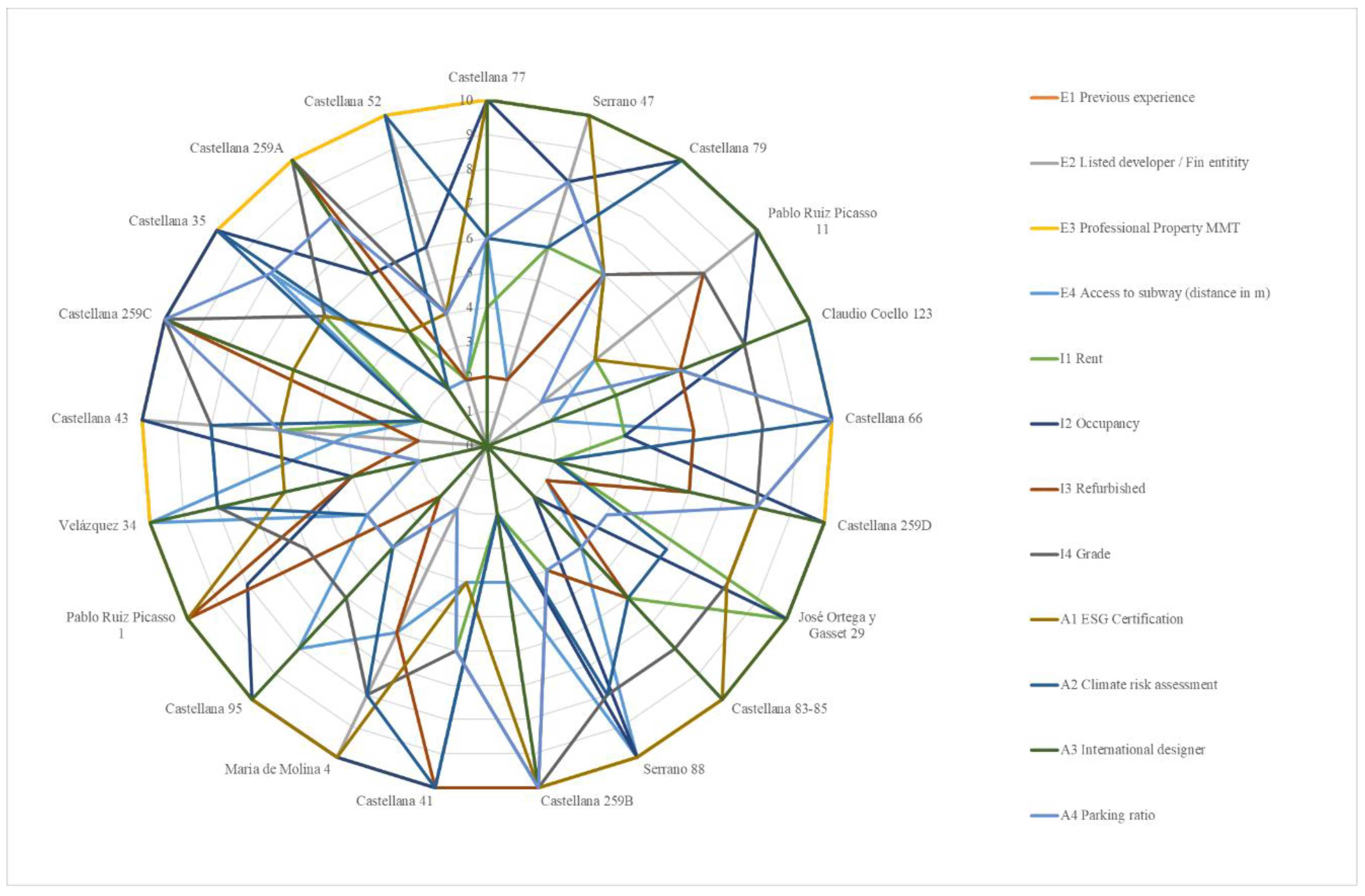

A chart with a summary of the results is presented below.

Figure 1.

MCDM results of office building projects. Source: Own study.

Figure 1.

MCDM results of office building projects. Source: Own study.

7. Results

The multi-criteria decision-making analysis of 21 office projects in Madrid's CBD yielded several key findings:

Looking at the top performers (Castellana 77), the building has LEED Platinum certification, contributing to its strong performance [67]. Good location and accessibility to the subway increase scoring [68].

Professional Property Management services enhance tenant satisfaction, leading to increased renewal intentions and, consequently, higher rents [69].

Similarly, Castellana 79, benefits from a high-quality refurbishment and international designer influence [70].

On the other side, lower performing buildings, like Castellana 52, scored lower, not due to their ESG certifications [71], but to location accessibility, and suffering from lower parking ratio reflections [72].

Spider chart with a summary of the results is shown below.

Figure 3.

MCDM results and appraisal of 21 office buildings. Source: own study.

Figure 3.

MCDM results and appraisal of 21 office buildings. Source: own study.

ESG Certifications

In general, the rationale behind performance is driven by the adherence to ESG Certifications, location, accessibility and higher rents. Easy access to subways and prime residential areas positively influences their TAP_EIA scores. Additionally, refurbishment and modernization of the properties highlight improved scoring due to enhanced tenant appeal and functionality.

The ESG certification impact, therefore, shows different performance on BREEAM and LEED accreditations, which provide a comprehensive measure of sustainability, incorporating factors such as energy management and carbon footprint. This has been discussed with global organizations like ULI and RICS, emphasizing the broader financial benefits of sustainability [27].

Buildings with higher ESG certification scores generally exhibited superior TAP_EIA, significantly outperforming uncertified counterparts [57]. Among these, BREEAM Exceptional and LEED Platinum stand out for their focus on energy efficiency and carbon reduction, aligning closely with net-zero carbon objectives. Certifications in progress, like LEED in progress, cannot be fully ranked until finalized.

Location and Accessibility

The proximity to public transportation, specifically subway access, shows a strong positive correlation with TAP_EIA scores, underpinning the importance of accessibility in performance metrics. Moreover, buildings located in prime residential neighborhoods outperform those in less desirable areas, reinforcing the impact of location on asset desirability [73].

Developer and Owner Influence

Properties developed by listed companies or financial entities generally achieve better performance, reflecting superior TAP_EIA scores compared to those with different ownership structures [74]. This indicates that institutional backing enhances valuation and resilience.

Tenant Appeal and Quality

Buildings with high-quality fit-outs and embodying "flight to quality" traits achieved TAP_EIA scores above the average [75]. Properties managed professionally also consistently outperformed others, highlighting a considerable improvement in overall ratings.

Sustainability Features

Incorporation of alternative uses or terrace spaces can modestly enhance TAP_EIA scores, while traditional amenities like parking ratios show a weaker correlation with performance, suggesting greater emphasis on sustainable transport options [76].

Brand and Architecture

Buildings designed by noted architects command a premium in TAP_EIA scores, while properties with scalable brands perform better, underscoring the value of architectural distinction and brand equity.

Distribution of Scores

The TAP_EIA scores for the examined projects range up to 8.32, with 60% of projects scoring above the mean, which reflects the high quality of the sample.

The results delineate the multifaceted factors driving office building performance, affirming that ESG certifications, prime location, and superior management are crucial. Investments in sustainability and tenant-focused amenities substantially enhance asset performance, corroborating their strategic value in the real estate market within Madrid's CBD.

8. Discussion

The analysis of Class A office buildings in Madrid highlights the significant role of ESG certifications in enhancing property performance. This research confirms that ESG-certified properties, particularly those with LEED Platinum and BREEAM Exceptional ratings, consistently achieve higher TAP_EIA scores.

Interpretation of Key Findings

This correlation supports the hypothesis that sustainability features contribute to increased asset values and market resilience. Moreover, the importance of location and accessibility is evident, with properties situated near public transport and prime areas outperforming others, emphasizing the continued value of strategic siting in real estate investments [78].

Implications for Stakeholders

For investors and asset managers, the findings underscore the economic benefits of prioritizing ESG-certified investments [79]. Such properties not only command higher rents but also appeal to tenants seeking sustainable solutions, enhancing long-term value and reducing vacancy risks [80].

Developers should consider ESG frameworks as essential components of new projects to meet growing tenant demands and regulatory requirements. Property owners can enhance the value of existing properties through strategic retrofitting to obtain certifications, potentially increasing asset liquidity and marketability [81].

Policymakers and Regulators both can leverage these insights to establish guidelines and incentives that promote sustainable building practices. Enhanced ESG reporting and transparency requirements could drive the adoption of green certifications, aligning real estate sector goals with broader environmental objectives [82].

The deployment of innovative financial instruments, such as green bonds and sustainability-linked loans, serves as a powerful catalyst for ESG adoption in the real estate sector [83]. Historical insights illustrate how financial products tailored to sustainability criteria can offer more favorable terms while enhancing property valuations through explicit environmental commitments [84]. Therefore, strategic use of these instruments can transform investor perceptions, attract cross-border capital inflows, and reinforce market stability by contextualizing real estate within the global push toward sustainable development.

Comparison with Previous Studies

This study aligns with prior research demonstrating a premium on green-certified buildings but expands the discourse by incorporating a multi-criteria decision-making approach [85]. Previous studies have focused solely on certification impacts; this analysis holistically integrates ESG factors with geographical and managerial influences, offering a more comprehensive view.

Limitations of the Study

This research primarily focuses on prime office locations within Madrid, potentially limiting the generalizability of its findings to other geographic or market contexts. Future studies could expand the scope to include more diverse building types and locations. Additionally, while ESG certifications are pivotal, other emerging sustainability metrics warrant further investigation to provide a more rounded understanding of their financial impacts.

Recommendations for Climate Risk Mitigation

Implementing climate risk mitigation strategies, such as cool roofs, which are effective in reducing heat impact, is recommended [86]. The positive relationship between climate risk management and financial performance suggests that adopting these measures can significantly enhance corporate value [87]. Bridging the gap between theory and practical valuation of climate risks remains critical [88], with industry standards needing integration into routine real estate assessments [89].

Part of the most recent development on AI suggests incorporating technological advancements in the real estate sector, for instance, the integration of PropTech solutions providing a transformative approach to ESG data accuracy and decision-making efficiency [90]. Recent studies, such as those by Wang and Liu [91], have demonstrated how Internet of Things (IoT) applications enhance the energy efficiency of buildings, thus promoting sustainable practices [92]. By embedding smart building technologies, owners and managers can leverage real-time data analytics to optimize resource consumption, facilitate predictive maintenance, and enhance occupant comfort, significantly improving overall building performance [93].

By addressing these areas, stakeholders can better navigate the evolving landscape of real estate investment, ensuring assets are not only sustainable in performance but also resilient to future climate-related challenges.

9. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence of the significant impact that ESG certifications have on the performance and valuation of Class A office buildings in Madrid's CBD [52]. By employing a comprehensive multi-criteria analysis on 21 office projects, the research highlights the complex interplay between sustainability features, location attributes, and financial performance. Buildings with high-level ESG certifications consistently outperform their non-certified counterparts, achieving substantially higher TAP_EIA scores [50]. This performance advantage encompasses energy efficiency, public transport accessibility, and superior property management. The findings emphasize the growing importance of sustainability in real estate investment decisions, aligning with the European Central Bank’s emphasis on climate risk for financial stability [94].

This research advances academic knowledge by integrating ESG factors with real estate performance metrics, climate risk considerations, and location quality. It provides a detailed analysis of how these elements interact, offering a comprehensive framework for understanding the value-creation potential of sustainable practices in the real estate sector [2]. The study contributes to the literature by highlighting how ESG certifications can mitigate climate-related financial risks, offering actionable insights for regional and international markets [11]. This aligns with prior studies but extends their scope by incorporating a multi-dimensional analysis of ESG impacts on property performance and valuation.

For practitioners, the study underscores the necessity of integrating ESG certifications and strategic refurbishments into asset management and investment strategies to enhance property value and marketability [69]. Additionally, the application of MCDM techniques in assessing the interplay between climate risk, ESG performance, and traditional real estate valuation metrics [95].

Policymakers can leverage these findings to promote sustainable building practices and inform future regulations. Real estate professionals should prioritize sustainability features and accessibility to maximize asset performance, while investors and asset managers should focus on high-ESG properties to secure higher rent and valuation returns. Moreover, real estate players could spearhead the development of comprehensive valuation models incorporating ESG and climate risk factors, offering tailored retrofit solutions to improve asset values [96].

Future studies should explore the long-term financial implications of ESG investments in real estate, particularly their effects on asset liquidity and economic resilience. Investigating the potential for standardizing ESG metrics across different European markets could enhance transparency and comparability in sustainable investments [34]. Additional research might focus on quantifying the real-world impacts of climate risks on property valuations, loan-to-value ratios, and investment returns across diverse regions and property types. Standardized methodologies for incorporating climate risk into valuations are also necessary to ensure consistency and accommodate regional variations in risk profiles and market dynamics.

In conclusion, this research shows that ESG factors are not just about following rules but are key to creating value in today's real estate market [97]. The results strongly support using sustainable practices to stay competitive and ensure properties perform well over time, especially as more people focus on ESG issues [98]. Climate risk assessments are getting more specific for each property, suggesting a move towards evaluating climate risks locally in real estate markets. This means that real estate, insurance, and banking sectors need to work together to create a clear framework for assessing climate risk that everyone can use and understand. The findings from this study provide important information to help assess overall financial stability and support the shift towards stronger, more sustainable property markets.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to not being applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found in the supplementary materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 |

An external advisor could assign a correlative value to each E, I, and A, indicator. In our case, 1 to 5. |

References

- Campiglio, E.; Dafermos, Y.; Monnin, P.; Ryan-Collins, J.; Schotten, G.; Tanaka, M. Climate change challenges for central banks and financial regulators. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I.; Searcy, C. Integrating sustainability with corporate governance: a framework to implement the corporate sustainability reporting directive through a balanced scorecard. Manag. Decis. 2024, 63, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yébenes, M.O. Climate change, ESG criteria and recent regulation: challenges and opportunities. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2024, 14, 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Overbeek, R.; Ishaak, F.; Geurts, E.; Remøy, H. The added value of environmental certification in the Dutch office market. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2024, 17, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialardo, A.; Micelli, E.; Saccani, F. Does Sustainability Affect Real Estate Market Values? Empirical Evidence from the Office Buildings Market in Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2018, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Zheng, X.; Wang, P.-H.; Liang, J.; Hu, L. Research Progress of Carbon-Neutral Design for Buildings. Energies 2023, 16, 5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsak, E.E.; Ahiska, S.S. Practical common weight multi-criteria decision-making approach with an improved discriminating power for technology selection. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2005, 43, 1537–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, A.V.; Pacheco, G.R.; González, F.J.N. HOLISTIC APPROACH TO THE SUSTAINABLE COMMERCIAL PROPERTY BUSINESS: ANALYSIS OF THE MAIN EXISTING SUSTAINABILITY CERTIFICATIONS. Int. J. Strat. Prop. Manag. 2020, 24, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contat, J.; Hopkins, C.; Mejia, L.; Suandi, M. When climate meets real estate: A survey of the literature. Real Estate Econ. 2024, 52, 618–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhuyse, F.; Piseddu, T.; Moberg, Å. What evidence exists on the impact of climate change on real estate valuation? A systematic map protocol. Environ. Évid. 2023, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Luo, S. Sustainable development, ESG performance and company market value: Mediating effect of financial performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 3371–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Sheedy, Climate Risk Management, Taylor & Francis, 2021.

- Zhang, L.; Bai, E. The Regime Complexes for Global Climate Governance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, D.; Cheng, S.; Lioui, A.; Tarelli, A. Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. J. Financial Econ. 2022, 145, 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Ozkan, H. A. Ozkan, H. Temiz and Y. Yildiz, "Climate risk, corporate social responsibility, and firm performance," British Journal of Management, vol. 34, no. 4, p. 1791–1810, 2022.

- N. E. Hultman, D. M. N. E. Hultman, D. M. Hassenzahl and S. Rayner, "Climate risk," Annual Review of Environment and Resources, vol. 35, no. 1, p. 283–303, 2010.

- Karerat, S.; Houghton, A.; Dickinson, G. Leveraging healthy buildings as a tool to apply a people-centric approach to ESG. Corp. Real Estate J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, D.; Benkraiem, R.; Guesmi, K.; Vigne, S. The European Central Bank and green finance: How would the green quantitative easing affect the investors' behavior during times of crisis? Int. Rev. Financial Anal. 2022, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, H.; Aracil, E. Climate-related credit risk: Rethinking the credit risk framework. Glob. Policy 2024, 15, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, M.; Bertrand, J.-L. Climate risks and financial stability: Evidence from the European financial system. J. Financial Stab. 2023, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coën, A.; Lefebvre, B.; Simon, A. Monetary Policies and European Office Markets Dynamics. J. Real Estate Res. 2022, 44, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.; Devaney, S.; Sayce, S.; Van de Wetering, J. Climate Risk and Real Estate Prices: What Do We Know? J. Portf. Manag. 2021, 47, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Lu-Andrews, R.; Wu, Z. Commercial Real Estate in the Face of Climate Risk: Insights from REITs. J. Real Estate Res. 2024, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Hakimian, "Newcivilengineer.com," 24 9 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.newcivilengineer.com/latest/leading-industry-organisations-launch-new-uk-standard-for-zero-carbon-buildings-24-09-2024/. [Accessed 14 12 2024].

- Hamrouni, A.; Boussaada, R.; Toumi, N.B.F. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and debt financing. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2019, 20, 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, D.C.; Robinson, S.; Sanderford, A.R.; Wang, C. Climate change and commercial property markets. J. Reg. Sci. 2024, 64, 1066–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Li, Z. J. Li, Z. Zhai, H. Li, Y. Ding and S. Chen, "Climate change’s effects on the amount of energy used for cooling in hot, humid office buildings and the solutions," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 442, p. 140967, 2024.

- Fernandes, M.S.; Coutinho, B.; Rodrigues, E. The impact of climate change on an office building in Portugal: Measures for a higher energy performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellura, M.; Guarino, F.; Longo, S.; Tumminia, G. Climate change and the building sector: Modelling and energy implications to an office building in southern Europe. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2018, 45, 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooyberghs, H.; Verbeke, S.; Lauwaet, D.; Costa, H.; Floater, G.; De Ridder, K. Influence of climate change on summer cooling costs and heat stress in urban office buildings. Clim. Chang. 2017, 144, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaripadath, D.; Rahif, R.; Zuo, W.; Velickovic, M.; Voglaire, C.; Attia, S. Climate change sensitive sizing and design for nearly zero-energy office building systems in Brussels. Energy Build. 2023, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Bagh, J. T. Bagh, J. Fuwei and M. A. Khan, "From risk to resilience: Climate change risk, ESG investments engagement and Firm’s value," Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 5, 2024.

- Naseer, M.M.; Khan, M.A.; Bagh, T.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, X. Firm climate change risk and financial flexibility: Drivers of ESG performance and firm value. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2023, 24, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, J.; Cao, J.; Fang, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, X. Climate change impacts on extreme energy consumption of office buildings in different climate zones of China. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2020, 140, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliūdžius, R.; Banionis, K.; Monstvilas, E.; Norvaišienė, R.; Adilova, D.; Prozuments, A.; Borodinecs, A. Analysis of Improvement in the Energy Efficiency of Office Buildings Based on Energy Performance Certificates. Buildings 2024, 14, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, O.I.; Enegbuma, W.I.; Donn, M. Operational, embodied and whole life cycle assessment credits in green building certification systems: Desktop analysis and natural language processing approach. Build. Environ. 2024, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolskienė, N.; Tamošiūnienė, R.; Banaitis, A.; Ferreira, F.A.F.; Banaitienė, N.; Taujanskaitė, K.; Meidutė-Kavaliauskienė, I. Developing a composite sustainability index for real estate projects using multiple criteria decision making. Oper. Res. 2017, 19, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopounidis, C.; Garefalakis, A.; Lemonakis, C.; Passas, I. Environmental, social and corporate governance framework for corporate disclosure: a multicriteria dimension analysis approach. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 2473–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciambra, A.; Stamos, I.; Siragusa, A. Localizing and Monitoring Climate Neutrality through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Framework: The Case of Madrid. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxas, T.; Juarez, L.; Gavriilidis, G. Planning and Marketing the City for Sustainability: The Madrid Nuevo Norte Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, M.; Ramallo, S.; Ruiz, M. Price and Spatial Distribution of Office Rental in Madrid: A Decision Tree Analysis. Economia 2021, 44, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Rieiro-Díaz, A.M.; Alba, D.; Langemeyer, J.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Ametzaga-Arregi, I. Urban resilience through green infrastructure: A framework for policy analysis applied to Madrid, Spain. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keisler, J.M.; Wells, E.M.; Linkov, I. A Multicriteria Decision Analytic Approach to Systems Resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2024, 15, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegut, A.; Eichholtz, P.; Kok, N. The price of innovation: An analysis of the marginal cost of green buildings. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2019, 98, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcarea, L.; Radulescu, C.V.; Manescu, A.M. BENEFITS OF INTEGRATING SUSTAINABILITY INTO INSURANCE COMPANIES. J. Financial Stud. 2024, 9, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukas, H.; Nikas, A. Decision support models in climate policy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, A.; Johansson, J.; Ivanov, O.L.; Björnsson, I.; Honfi, D. Risk-based multi-criteria decision analysis method for considering the effects of climate change on bridges. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2022, 19, 1445–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercereau, B.; Melin, L.; Lugo, M.M. Creating shareholder value through ESG engagement. J. Asset Manag. 2022, 23, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C.; Petrova, M.T. Building Sustainability, Certification, and Price Premiums: Evidence from Europe. J. Real Estate Res. 2023, 46, 514–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porumb, V.-A.; Maier, G.; Anghel, I. The impact of building location on green certification price premiums: Evidence from three European countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichholtz, P.; Holtermans, R.; Kok, N. Environmental Performance of Commercial Real Estate: New Insights into Energy Efficiency Improvements. J. Portf. Manag. 2019, 45, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, N.; Vimpari, J.; Junnila, S. A Review of the Impact of Green Building Certification on the Cash Flows and Values of Commercial Properties. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Kim, J.; Kim, T. Critical Review on Economic Effect of Renovation Works for Sustainable Office Building Based on Opinions of Real-Estate Appraisers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.C.; Batten, J.A.; Ahmad, A.H.; Mohamed-Arshad, S.B.; Nordin, S.; Adzis, A.A. Does ESG certification add firm value? Finance Res. Lett. 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. De Jong and S. Rocco, “ESG and impact investing,” Journal of Asset Management, vol. 23, no. 7, p. 547–549, 2022.

- Vaisi, S.; Varmazyari, P.; Esfandiari, M.; Sharbaf, S.A. Developing a multi-level energy benchmarking and certification system for office buildings in a cold climate region. Appl. Energy 2023, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, T.T.; Muttakin, M.; Mihret, D. Environmental, social, and governance performance, national cultural values and corporate financing strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.; Guo, C.Q.; Luu, B.V. Environmental, social and governance transparency and firm value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; White, M. Does Energy Performance Rating Affect Office Rents? A Study of the UK Office Market. J. Sustain. Real Estate 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroul, R.R.; Sabherwal, S.; Villupuram, S.V. ESG, operational efficiency and operational performance: evidence from Real Estate Investment Trusts. Manag. Finance 2022, 48, 1206–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolskienė, N.; Pozniak, A.; Tvaronavičienė, M. Assessment of the Sustainability of a Real Estate Project Using Multi-Criteria Decision Making. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-C. A HYBRID MULTIPLE CRITERIA DECISION-MAKING MODEL FOR INVESTMENT DECISION MAKING. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2014, 15, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Bhole, “Multi Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods and its applications,” International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology, vol. 6, no. 5, 2018.

- C. Colapinto, R. C. Colapinto, R. Jayaraman, F. Abdelaziz and D. Torre, “Environmental sustainability and multifaceted development: multi-criteria decision models with applications,” Annals of Operations Research, vol. 293, no. 2, pp. 405-432, 2019.

- Kettani, O.; Oral, M.; Siskos, Y. A Multiple Criteria Analysis Model For Real Estate Evaluation. J. Glob. Optim. 1998, 12, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Kim, "Green building strategies for LEED-certified laboratory buildings: comparison between gold and platinum levels," International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 153–173, 2020.

- Kopczewska, K.; Lewandowska, A. The price for subway access: spatial econometric modelling of office rental rates in London. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 1528–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Choi, M.-S. ; Residential Environment Institute Of Korea A Study on the Effect of Property Management Service Quality on Renewal Intent of Commercial Real Estate: Focusing on Office Building Property Management (PM). Resid. Environ. Inst. Korea 2022, 20, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. C. Cheshire and G. H. Dericks, "“Trophy Architects” and Design as Rent-seeking: Quantifying Deadweight Losses in a Tightly Regulated Office Market," Economica, vol. 87, no. 348, p. 1078–1104, 2020.

- Cordero, A.S.; Melgar, S.G.; Márquez, J.M.A. Green Building Rating Systems and the New Framework Level(s): A Critical Review of Sustainability Certification within Europe. Energies 2019, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhu, M.; Xiao, Z. Workplace Parking Provision and Built Environments: Improving Context-Specific Parking Standards Towards Sustainable Transport. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Liu and C. Z. B. Z., "The Agglomerative Effects of Neighborhood and Building Specialization on Office Values," in 28th Annual European Real Estate Society Conference. ERES, Milan, 2022.

- Z. Rezaee, S. Z. Rezaee, S. Homayoun, E. Poursoleyman and N. J. Rezaee, "Comparative analysis of environmental, social, and governance disclosures," Global Finance Journal, vol. 55, no. 100804, 2023.

- K. Matsuo, M. K. Matsuo, M. Tsutsumi, T. I. and T. K., "The Impact of the Flight to Quality on Office Rents and Vacancy Rates in Tokyo," Real Estate Management and Valuation, vol. 32, no. 3, 2024.

- S. Tsolacos, S. S. Tsolacos, S. Lee and H. Tse, "‘Space-as-a-service’: A premium to office rents?," Journal of European Real Estate Research, vol. 16, pp. 64-77, 2023.

- Jayakody, T.A.C.H.; Vaz, A. Impact of green building certification on the rent of commercial properties: A review. J. Informatics Web Eng. 2023, 2, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, N.; Vimpari, J.; Junnila, S. A Review of the Impact of Green Building Certification on the Cash Flows and Values of Commercial Properties. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morri, G.; Yang, F.; Colantoni, F. Green investments, green returns: exploring the link between ESG factors and financial performance in real estate. J. Prop. Invest. Finance. [CrossRef]

- H. Grove, M. H. Grove, M. Clouse and T. Xu, "Risk governance for environmental, social, and governance investing and activities," Risk Governance and Control: Financial Markets & Institutions, vol. 14, no. 4, p. 50–58, 2024.

- Jaspers, E.; Ankerstjerne, P. The ESG challenge for real estate. Corp. Real Estate J. 2023, 12, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. D. A. Soyombo, "The role of policy and regulation in promoting green buildings," World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 139–150, 2024.

- D. Raji, "SUSTAINABLE FINANCE IN ACTION: EXPLORING GREEN LOANS IN PROMOTING ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY," Kristu Jayanti Journal of Management Sciences (KJMS), vol. 2, no. 1, p. 14–25, 2024.

- Lützkendorf, T.; Lorenz, D. Sustainable property investment: valuing sustainable buildings through property performance assessment. Build. Res. Inf. 2005, 33, 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Theilig, B. K. Theilig, B. Lourenço and R. Reitberger, "Life cycle assessment and multi-criteria decision-making for sustainable building parts: criteria, methods, and application," Int J Life Cycle Assess, vol. 29, no. 11, p. 1965–1991, 2024.

- Rincón, L.; Gangolells, M.; Medrano, M.; Casals, M. Climate change mitigation and adaptation in Spanish office stock through cool roofs. Energy Build. 2024, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. M. Naseer, Y. M. M. Naseer, Y. Guo, T. Bagh and X. Zhu, "Sustainable investments in volatile times: Nexus of climate change risk, ESG practices, and market volatility," International Review of Financial Analysis, vol. 95, p. 103492, 2024.

- Sayce, S.L.; Clayton, J.; Devaney, S.; van de Wetering, J. Climate risks and their implications for commercial property valuations. J. Prop. Invest. Finance 2022, 40, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tang, W.; Liang, F.; Wang, Z. The impact of climate change on corporate ESG performance: The role of resource misallocation in enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S. Leveraging artificial intelligence to enhance ESG models: Transformative impacts and implementation challenges. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 69, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L. Research on sustainable green building space design model integrating IoT technology. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0298982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, K.M.; Hossain, M.; Alduais, N.A.M.; Al-Duais, H.S.; Omrany, H.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. A Review of Using IoT for Energy Efficient Buildings and Cities: A Built Environment Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Poyyamozhi, B. M. Poyyamozhi, B. Murugesan, N. Rajamanickam, M. Shorfuzzaman and Y. Aboelmagd, "IOT—A Promising solution to energy management in smart Buildings: A Systematic Review, applications, barriers, and future scope," Buildings, vol. 14, no. 11, p. 3446.

- Matisoff, D.C.; Noonan, D.S.; Flowers, M.E. Policy Monitor—Green Buildings: Economics and Policies. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2016, 10, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Riandari, M. Z. F. Riandari, M. Z. Albert and S. S. Rogoff, "MCDM methods to address sustainability challenges, such as climate change, resource management, and social justice," Idea Future Research, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 25–38, 2023.

- Chen, S.; Song, Y.; Gao, P. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonlanthen, J. ESG Ratings and Real Estate Key Metrics: A Case Study. Real Estate 2024, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morri, G.; Dipierri, A.; Colantoni, F. ESG dynamics in real estate: temporal patterns and financial implications for REITs returns. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Wilkinson and S. Sayce, "Decarbonising real estate," Journal of European Real Estate Research, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 387–408, 2020.

- Huang, Y.; Bai, F.; Shang, M.; Ahmad, M. On the fast track: the benefits of ESG performance on the commercial credit financing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 83961–83974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Battisti, G.; Guin, B. The greening of lending: Evidence from banks’ pricing of energy efficiency before climate-related regulation. Econ. Lett. 2023, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Newell, “Real Estate Insights The increasing importance of the “S” dimension in ESG,” Journal of Property Investment and Finance, vol. 41, no. 4, p. 453–459, 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).