5. Theoretical Framework for Structural fragility curves

Fragility curves represent the probability of reaching or exceeding a specified limit damage state when a structure is subjected to a given hazard intensity. In the following definition, momentum flux was used as the intensity parameter (Eq, (23)). Nevertheless, other variables, such as height (h) or overturning moment (h

2v

2), can also be used. Log-normal functions are proposed as mass movement fragility curves using the momentum flux, hv

2 (where h and v are the height and velocity of mass movement at a given site, respectively) as the hazard intensity parameter [

30]. Each curve is characterised by a median value and its log-normal standard deviation (β). Therefore, the probability of reaching or exceeding a specific damage state, given a structural response due to a defined hazard (mass movements), can be calculated as follows:

Which denotes a cumulative logarithmic normal distribution, where:

: the mass movement impact index represents the intensity of the hazard.

: it is the median value of the impact index at which the building reaches the Damage State (DS).

: it is the standard deviation of the natural logarithm of the impact index associated with a Damage State (DS).

Φ: it is the standard normal cumulative distribution function.

These curves are defined by two parameters: the median value and the standard deviation . The median value defines the point at which the probability of equaling or exceeding the damage state equals 50%, and the standard deviation gives an idea of the scatter.

7. Discussion

This research provides information on flow intensity parameters, including velocity, dynamic thrust, momentum flow and overturning moment, between 3 and 5 November 2019 in Jericó, Antioquia, Colombia. It also provides a technical description of the structural damage to the impacted buildings. In addition, it includes information on the structural fragility of unreinforced masonry buildings in the municipality due to mass movements.

The median thrust for houses 1, 6, and 7 is 841.8 kN, and for house 4, it is 556.64 kN (

Table 10). The median momentum flux for houses 1, 6, and 7 is 81.26 m

3/s

2, and for house 4, it is 50.89 m

3/s

2 (

Table 11). This is contrasted with the median momentum flux threshold of 23.30 m

3/s

2 for a complete damage state in URM Colombian structures [

30], which supports the collapse of the unreinforced masonry houses studied.

Although the damage to house number two was slight, some facade walls collapsed because they were forced to flex out-of-plane due to the landslide. The median momentum flux that caused the walls to collapse was 40.63 m3/s2, contrasted with a complete damage threshold equal to 0.46 m3/s2. This analysis reiterates the inability of unreinforced masonry to assume flexion out-of-plane. Although these types of local failures in a building must be analysed, it is essential to appreciate that the partially confined masonry building's overall stability was maintained. The three-story building also has a reinforced concrete frame system at the first-story level, giving it additional strength. It must be recognised that part of the lateral load with which this building was analysed (house 2) was dissipated by the collapsed house, number 1.

Electricity, among other services, is vital even in atypical situations such as those generated by debris flows. However, for the event that occurred in Jericó, the collapse of a power pole was observed under a medium thrust of 21.01 kN, a median momentum flux of 33.98 m3/s2, and a median overturning moment of 51.09 m4/s2. Contrasting complete damage thresholds with a shear median capacity of 18.13 kN, a median momentum flux of 28.87 m3/s2, and a median overturning moment of 56.46 m4/s2. According to what was observed on the ground, the hydraulic concrete of the power pole failed at the base when the shear force of the debris flow impacted it.

Considering the different variables and the uncertainty in calculating intensity and structural fragility, it was decided to do a probabilistic analysis using Monte Carlo simulation. It is necessary to know the different variables to reduce uncertainty by taking advantage of prior knowledge and field data. The technique illustrated in this work allows the probability calculation of hazard intensity, structural fragility, and risk against mass movements.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; methodology, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; software, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; validation, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; formal analysis, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; investigation, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; resources, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; writing—review and editing, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; visualisation, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B; supervision, A.L.S-C., J.A.P., J.W.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figures and Tables

Figure 4.

(a) Affected buildings. 1st Avenue – 7th Street, right side; (b) Buildings before the event. 1st Avenue – 7th Street, right side.

Figure 4.

(a) Affected buildings. 1st Avenue – 7th Street, right side; (b) Buildings before the event. 1st Avenue – 7th Street, right side.

Figure 5.

(a) The reinforced first storey with reinforced concrete frames. Interior view. house 2; (b) Rear facade. House 2. Reinforced with reinforced concrete wall in the first storey.

Figure 5.

(a) The reinforced first storey with reinforced concrete frames. Interior view. house 2; (b) Rear facade. House 2. Reinforced with reinforced concrete wall in the first storey.

Figure 6.

(a) Side facade, infill walls total collapse, House 2; (b) Side facade. Infill walls without total collapse. House 2.

Figure 6.

(a) Side facade, infill walls total collapse, House 2; (b) Side facade. Infill walls without total collapse. House 2.

Figure 7.

(a) Partially confined masonry structure. Side facade. House 3; (b) Partially confined masonry structure. Front facade. House 3.

Figure 7.

(a) Partially confined masonry structure. Side facade. House 3; (b) Partially confined masonry structure. Front facade. House 3.

Figure 8.

(a) House 4 Collapsed by the landslide; (b) Debris from House 4 due to landslide.

Figure 8.

(a) House 4 Collapsed by the landslide; (b) Debris from House 4 due to landslide.

Figure 9.

(a) Building before the event. The image about 2nd Avenue. House 4. Source: Google Earth; (b) Building before the event. Image of the intersection of 2nd Avenue and 9th Street. House 4. Source: Google Earth.

Figure 9.

(a) Building before the event. The image about 2nd Avenue. House 4. Source: Google Earth; (b) Building before the event. Image of the intersection of 2nd Avenue and 9th Street. House 4. Source: Google Earth.

Figure 10.

(a) Affected building 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. House 5; (b) The facade affected, house 5, 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side.

Figure 10.

(a) Affected building 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. House 5; (b) The facade affected, house 5, 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side.

Figure 11.

(a) Affected buildings 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. Houses 5, 6 and 7; (b) Buildings original state 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. House 5, 6, and 7. Source: Google Earth.

Figure 11.

(a) Affected buildings 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. Houses 5, 6 and 7; (b) Buildings original state 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. House 5, 6, and 7. Source: Google Earth.

Figure 12.

(a) Houses 6 and 7 collapsed. Left side. 1st Avenue – 7th Street; (b) Affected building 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. house 6.

Figure 12.

(a) Houses 6 and 7 collapsed. Left side. 1st Avenue – 7th Street; (b) Affected building 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. house 6.

Figure 13.

(a) Affected building 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. House 6. Earth wall detail; (b) Affected building detail 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. house 6.

Figure 13.

(a) Affected building 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. House 6. Earth wall detail; (b) Affected building detail 1st Avenue – 7th Street, left side. house 6.

Figure 14.

(a) A power pole collapsed on 6th Street, lower slope of las Nubes Hill; (b) Collapsed power pole on 6th Street, lower slope of las Nubes Hill.

Figure 14.

(a) A power pole collapsed on 6th Street, lower slope of las Nubes Hill; (b) Collapsed power pole on 6th Street, lower slope of las Nubes Hill.

Figure 15.

(a) Architectural view of houses located on 6th Street and the lower part of the slope of Las Nubes Hill. Source: Google Earth; (b) View of affected houses on the hillside of las Nubes Hill, Valladares Stream, 6th Street. The photo was taken after evacuating the debris flow.

Figure 15.

(a) Architectural view of houses located on 6th Street and the lower part of the slope of Las Nubes Hill. Source: Google Earth; (b) View of affected houses on the hillside of las Nubes Hill, Valladares Stream, 6th Street. The photo was taken after evacuating the debris flow.

Figure 16.

(a) Affected houses on the hillside of Las Nubes Hill, Valladares stream. 6th Street; (b) Debris level measurement of houses affected hillside of Las Nubes Hill, Valladares stream. 6th Street. The photo was taken after evacuating the debris flow.

Figure 16.

(a) Affected houses on the hillside of Las Nubes Hill, Valladares stream. 6th Street; (b) Debris level measurement of houses affected hillside of Las Nubes Hill, Valladares stream. 6th Street. The photo was taken after evacuating the debris flow.

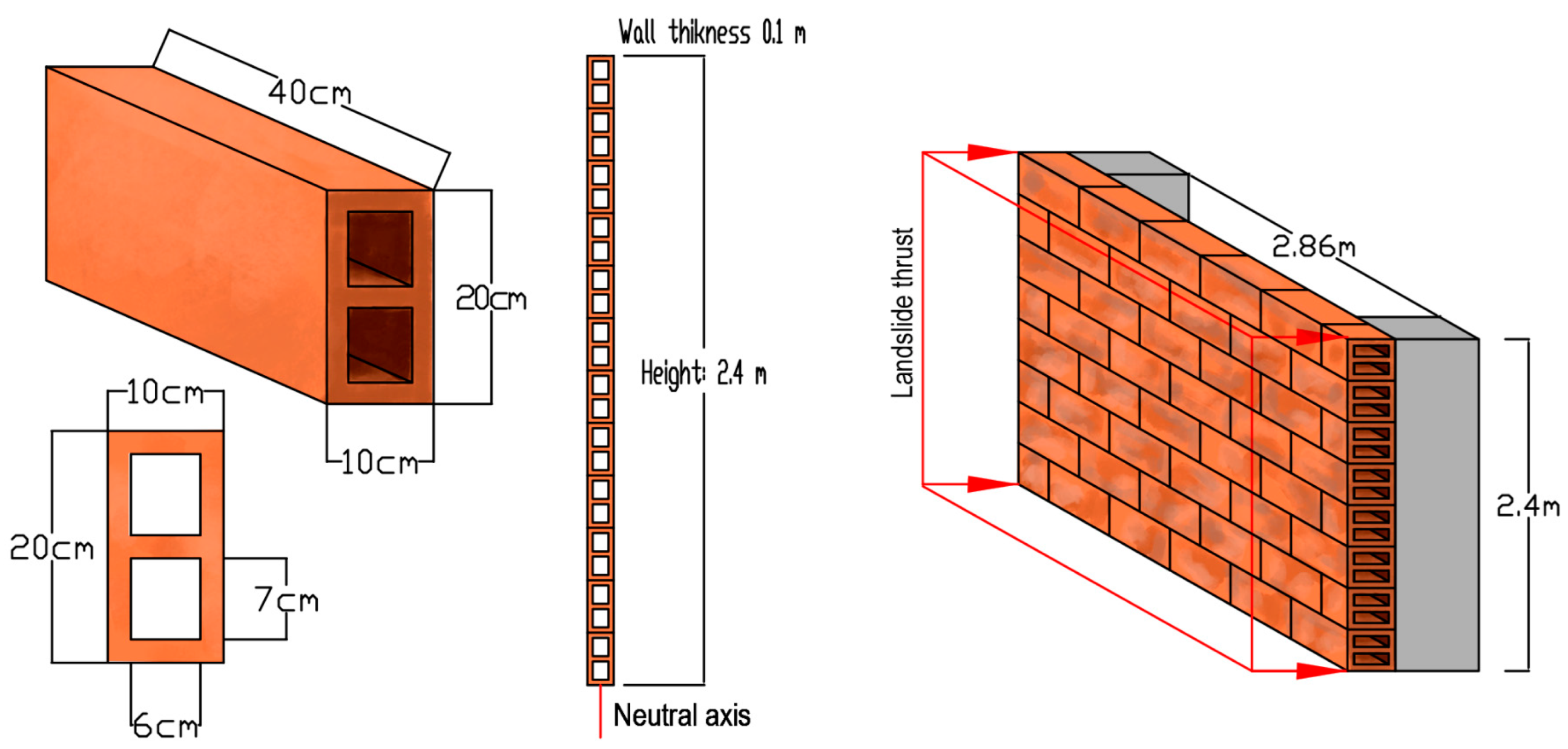

Figure 18.

Infill wall, subjected to dynamic lateral thrust due to landslide. 1st Avenue / 7th Street. Dwelling 2.

Figure 18.

Infill wall, subjected to dynamic lateral thrust due to landslide. 1st Avenue / 7th Street. Dwelling 2.

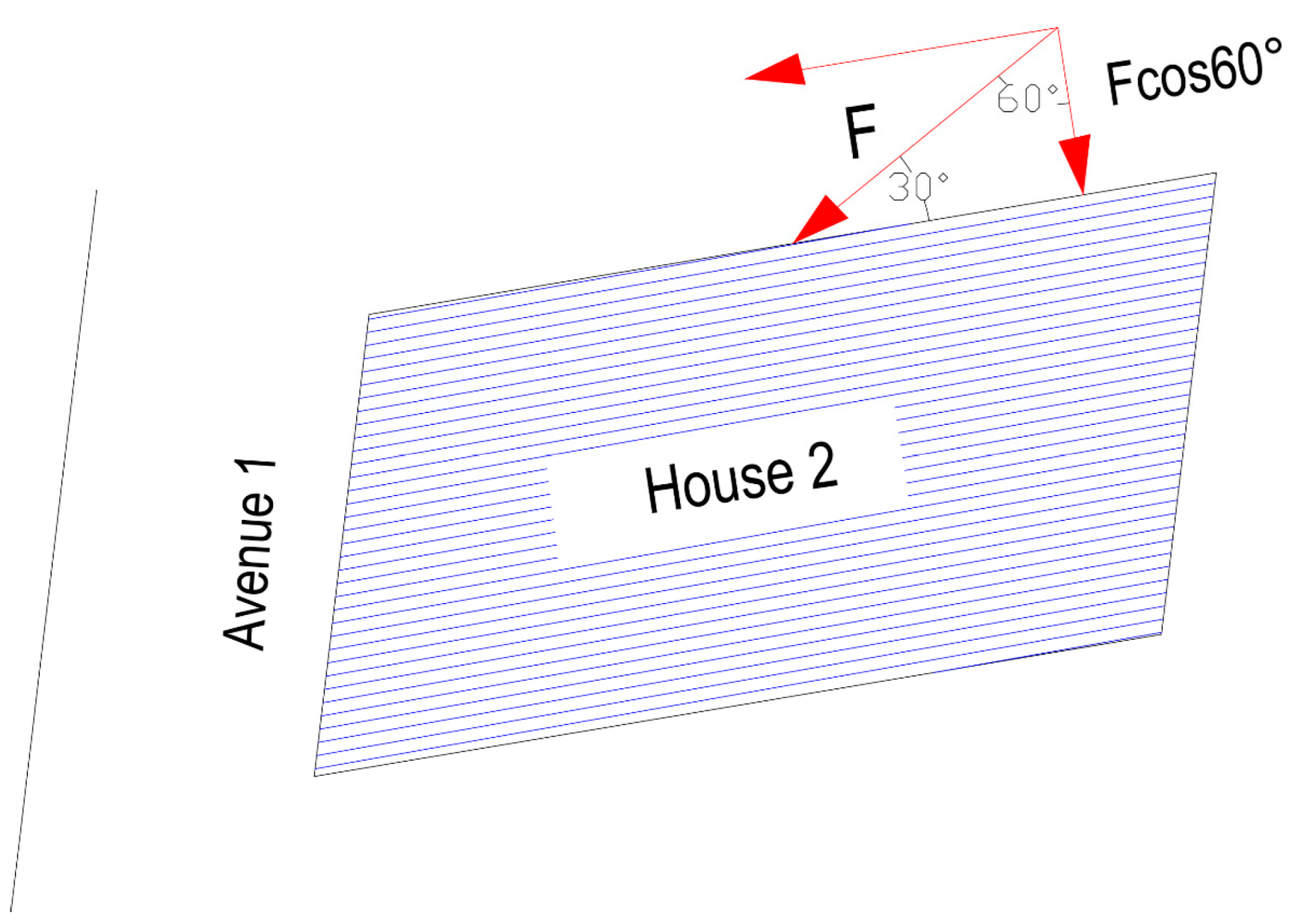

Figure 19.

Location of house 2 and landslide angle of attack. 1st Avenue, 7th Street.

Figure 19.

Location of house 2 and landslide angle of attack. 1st Avenue, 7th Street.

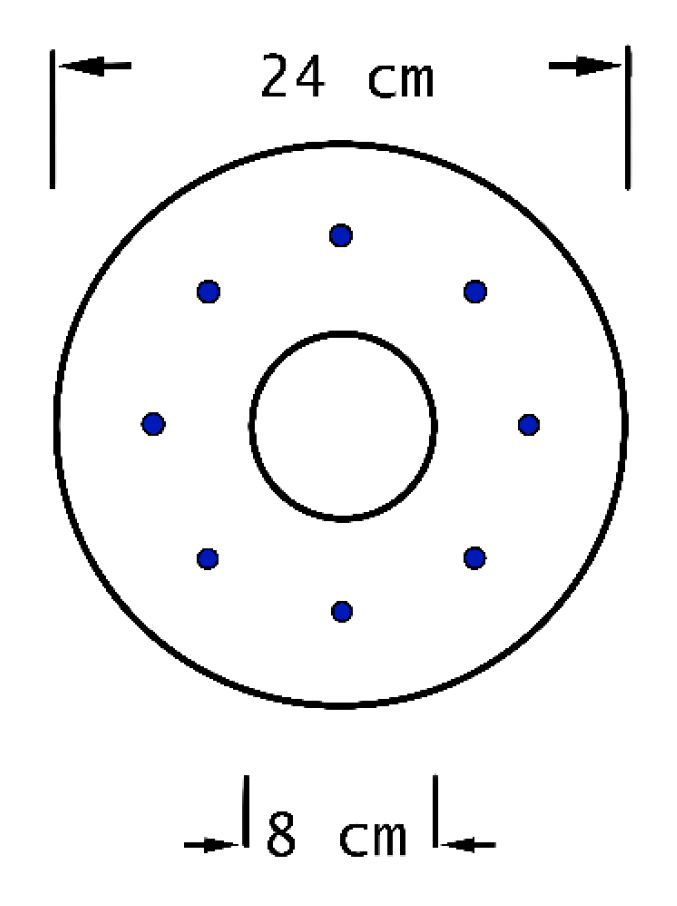

Figure 21.

Cross section of the power pole located on 6th Street on the slope of Las Nubes Hill.

Figure 21.

Cross section of the power pole located on 6th Street on the slope of Las Nubes Hill.

Table 5.

Mixed hydraulic models.

Table 5.

Mixed hydraulic models.

| Reference |

Equation |

|

| Arattano and Franzi (2003) |

|

(38) |

| Hübl and Holzinger (2003) |

|

(19) |

| Cui et al (2015) |

|

(20) |

| Gong, 2020 |

|

(21) |

Table 6.

Field parameters for velocity calculation.

Table 6.

Field parameters for velocity calculation.

| Variable |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Setting function |

| φ (˚) |

2.29 |

14 |

uniform |

| β (˚) Houses 1, 6 y 7 |

14 |

15 |

uniform |

| β (˚) House 4 |

16 |

17 |

uniform |

| h' (m) Houses 1, 6 y 7 |

5 |

7 |

uniform |

| h' (m) House 4 |

3 |

4 |

uniform |

Table 7.

Statistical parameters for the calculation of velocity, houses 1, 6 and 7.

Table 7.

Statistical parameters for the calculation of velocity, houses 1, 6 and 7.

| Setting function |

|

Triangular |

| Minimum |

|

0.53 |

| Maximum |

|

10.78 |

| Mode |

|

9.15 |

| Mean |

|

6.82 |

| Median |

|

7.18 |

| Standard deviation |

|

2.25 |

Table 8.

Statistical parameters for the calculation of velocity, house 4.

Table 8.

Statistical parameters for the calculation of velocity, house 4.

| Setting function |

|

Pert |

| Minimum |

|

1.75 |

| Maximum |

|

8.32 |

| Mode |

|

6.22 |

| Mean |

|

5.83 |

| Median |

|

5.92 |

| Standard deviation |

|

1.21 |

Table 9.

Field parameters for dynamic thrust calculation.

Table 9.

Field parameters for dynamic thrust calculation.

| Input parameter |

Minimum |

Probable |

Maximum |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Setting function |

| v (m/s), Houses 1, 6 y 7 |

0.53 |

9.15 |

10.78 |

|

|

Triangular |

| v (m/s), House 4 |

1.75 |

6.22 |

8.32 |

|

|

Pert |

| h (m), Houses 6 y 7 |

1 |

|

2.5 |

|

|

Uniform |

| h (m), House 4 |

1 |

|

2 |

|

|

Uniform |

| B (m) |

6 |

|

8 |

|

|

Uniform |

| ρ (kg/m3) |

|

|

|

1700 |

204.74 |

Log normal |

| Kd |

|

|

|

1.2 |

0.67 |

Log normal |

| Cd |

|

|

|

2 |

0.77 |

Log normal |

Table 10.

Statistical parameters for dynamic thrust calculation.

Table 10.

Statistical parameters for dynamic thrust calculation.

| Event |

Setting function |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Standard deviation |

| Houses 1, 6 y 7 |

Lognormal |

1327 |

841.8 |

315.53 |

1622.9 |

| House 4 |

Lognormal |

761 |

556.64 |

294.26 |

713.51 |

Table 11.

Statistical parameters for momentum flux calculation (hv2).

Table 11.

Statistical parameters for momentum flux calculation (hv2).

| Setting function |

General Beta (houses 1,6,7) |

General Beta (houses 4) |

| α1 |

1.35 |

2.65 |

| α2 |

2.91 |

5.53 |

| Minimum |

0.56 |

4.3 |

| Maximum |

282.71 |

155.05 |

| Mean |

89.91 |

53.14 |

| Median |

81.26 |

50.89 |

| Mode |

44.15 |

44.56 |

| Standard deviation |

57.22 |

23.28 |

Table 12.

Field parameters, ultimate out-of-plane load capacity for infill walls by landslide.

Table 12.

Field parameters, ultimate out-of-plane load capacity for infill walls by landslide.

| Input parameter |

Minimum |

Probable |

Maximum |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Setting function |

| f’m (MPa) |

|

|

|

3 |

0.9 |

Log normal |

| H (m) |

2.3 |

|

2.6 |

|

|

Uniform |

| B (m) |

2.7 |

|

2.9 |

|

|

Uniform |

| t (m) |

0.1 |

|

0.12 |

|

|

Uniform |

Table 13.

Statistical parameters, ultimate out-of-plane load capacity for infill walls by landslide.

Table 13.

Statistical parameters, ultimate out-of-plane load capacity for infill walls by landslide.

| Event |

Setting function |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Standard deviation |

| House 2 |

Lognormal |

11.3 |

10.75 |

9.72 |

3.73 |

Table 14.

Field parameters, infill walls fragility curve due to out-of-plane loads by landslide, complete damage state.

Table 14.

Field parameters, infill walls fragility curve due to out-of-plane loads by landslide, complete damage state.

| Input parameter |

Minimum |

Probable |

Maximum |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Setting function |

| Fu (kN) |

|

|

|

10.75 |

3.73 |

Log normal |

| Kd |

|

|

|

1.2 |

0.67 |

Log normal |

| Cd |

|

|

|

2 |

0.77 |

Log normal |

| ρ (kg/m3) |

|

|

|

1700 |

204.74 |

Log normal |

| B (m) |

2.7 |

|

2.9 |

|

|

Uniform |

Table 15.

Statistical parameters for the calculation of the infill walls fragility curve due to out-of-plane loads by landslide, complete damage state.

Table 15.

Statistical parameters for the calculation of the infill walls fragility curve due to out-of-plane loads by landslide, complete damage state.

| Event |

Setting function |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Standard deviation |

| House 2 |

Lognormal |

0.47 |

0.46 |

0.45 |

0.08 |

Table 16.

Parameters for calculating the debris flow velocity over 6th street coming from Las Nubes Hill.

Table 16.

Parameters for calculating the debris flow velocity over 6th street coming from Las Nubes Hill.

| Variable |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Setting function |

| Cv |

0.1 |

0.9 |

uniform |

| h (m) |

1.0 |

2.0 |

uniform |

| p (%) |

2.0 |

14 |

uniform |

| C |

0.0025 |

0.014 |

uniform |

Table 17.

Statistical data for debris flow velocity calculation.

Table 17.

Statistical data for debris flow velocity calculation.

| Setting function |

|

General Beta |

| α1 |

|

16.80 |

| α2 |

|

18.56 |

| Minimum |

|

3.29 |

| Maximum |

|

6.42 |

| Mean |

|

4.78 |

| Median |

|

4.78 |

| Mode |

|

4.77 |

| Standard deviation |

|

0.26 |

Table 18.

Field parameters for calculating debris flow dynamic thrust on the collapse of a power pole.

Table 18.

Field parameters for calculating debris flow dynamic thrust on the collapse of a power pole.

| Input parameter |

α1 |

α2 |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Setting function |

| v (m/s) |

16.80 |

18.56 |

3.29 |

6.42 |

|

|

General Beta |

| h (m) |

|

|

1.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

Uniform |

| ρ (kg/m3) |

|

|

|

|

1700 |

204.74 |

Log normal |

| Kd |

|

|

|

|

1.2 |

0.67 |

Log normal |

| Cd |

|

|

|

|

2 |

0.77 |

Log normal |

Table 19.

Statistical data for calculating the debris flow dynamic thrust on the power pole.

Table 19.

Statistical data for calculating the debris flow dynamic thrust on the power pole.

| Setting function |

|

Log normal |

| Mean |

|

26.58 |

| Median |

|

21.01 |

| Mode |

|

13.14 |

| Standard deviation |

|

20.58 |

Table 20.

Statistical data for calculating the power pole's debris flow momentum flux (hv2).

Table 20.

Statistical data for calculating the power pole's debris flow momentum flux (hv2).

| Setting function |

|

Pert |

| Minimum |

|

17.04 |

| Maximum |

|

59.93 |

| Mean |

|

34.46 |

| Median |

|

33.98 |

| Mode |

|

32.44 |

| Standard deviation |

|

7.96 |

Table 21.

Statistical data for calculating the debris flow overturning moment (h2 v2).

Table 21.

Statistical data for calculating the debris flow overturning moment (h2 v2).

| Setting function |

|

Pert |

| Minimum |

|

17.71 |

| Maximum |

|

119.16 |

| Mean |

|

53.41 |

| Median |

|

51.09 |

| Mode |

|

41.96 |

| Standard deviation |

|

20.43 |

Table 22.

Field parameters, ultimate power pole load capacity.

Table 22.

Field parameters, ultimate power pole load capacity.

| Input parameter |

Minimum |

Probable |

Maximum |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Setting function |

| f’c (MPa) |

|

|

|

14 |

4 |

Log normal |

| De (m) |

0.2 |

|

0.21 |

|

|

Uniform |

| Di (m) |

0.06 |

|

0.08 |

|

|

Uniform |

Table 23.

Statistical parameters, ultimate power pole load capacity.

Table 23.

Statistical parameters, ultimate power pole load capacity.

| Event |

Setting function |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Standard deviation |

| Power pole |

Lognormal |

18.33 |

18.13 |

17.75 |

2.66 |

Table 24.

Field parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to momentum flux.

Table 24.

Field parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to momentum flux.

| Input parameter |

Minimum |

Probable |

Maximum |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Setting function |

| Fu (kN) |

|

|

|

18.13 |

2.66 |

Log normal |

| Kd |

|

|

|

1.2 |

0.67 |

Log normal |

| Cd |

|

|

|

2 |

0.77 |

Log normal |

| ρ (kg/m3) |

|

|

|

1700 |

204.74 |

Log normal |

| B (m) |

0.375 |

|

0.375 |

|

|

Uniform |

Table 25.

Statistical parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to momentum flux.

Table 25.

Statistical parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to momentum flux.

| Event |

Setting function |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Standard deviation |

| Power pole |

Lognormal |

36.15 |

28.87 |

17.54 |

26.31 |

Table 26.

Field parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to overturning moment.

Table 26.

Field parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to overturning moment.

| Input parameter |

Minimum |

Probable |

Maximum |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Setting function |

| fy (MPa) |

|

|

|

240 |

15 |

Log normal |

| Kd |

|

|

|

1.2 |

0.67 |

Log normal |

| Cd |

|

|

|

2 |

0.77 |

Log normal |

| ρ (kg/m3) |

|

|

|

1700 |

204.74 |

Log normal |

| B (m) |

0.375 |

|

0.375 |

|

|

Uniform |

| As (cm2) |

3 |

|

5 |

|

|

Uniform |

Table 27.

Statistical parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to overturning moment.

Table 27.

Statistical parameters, power pole complete damage threshold due to overturning moment.

| Event |

Setting function |

Mean |

Median |

Mode |

Standard deviation |

| Power pole |

Lognormal |

70.79 |

56.46 |

35.91 |

53.55 |