Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inhibitors

2.2. Viruses

2.3. Infection Experiments

2.4. Cell Culture

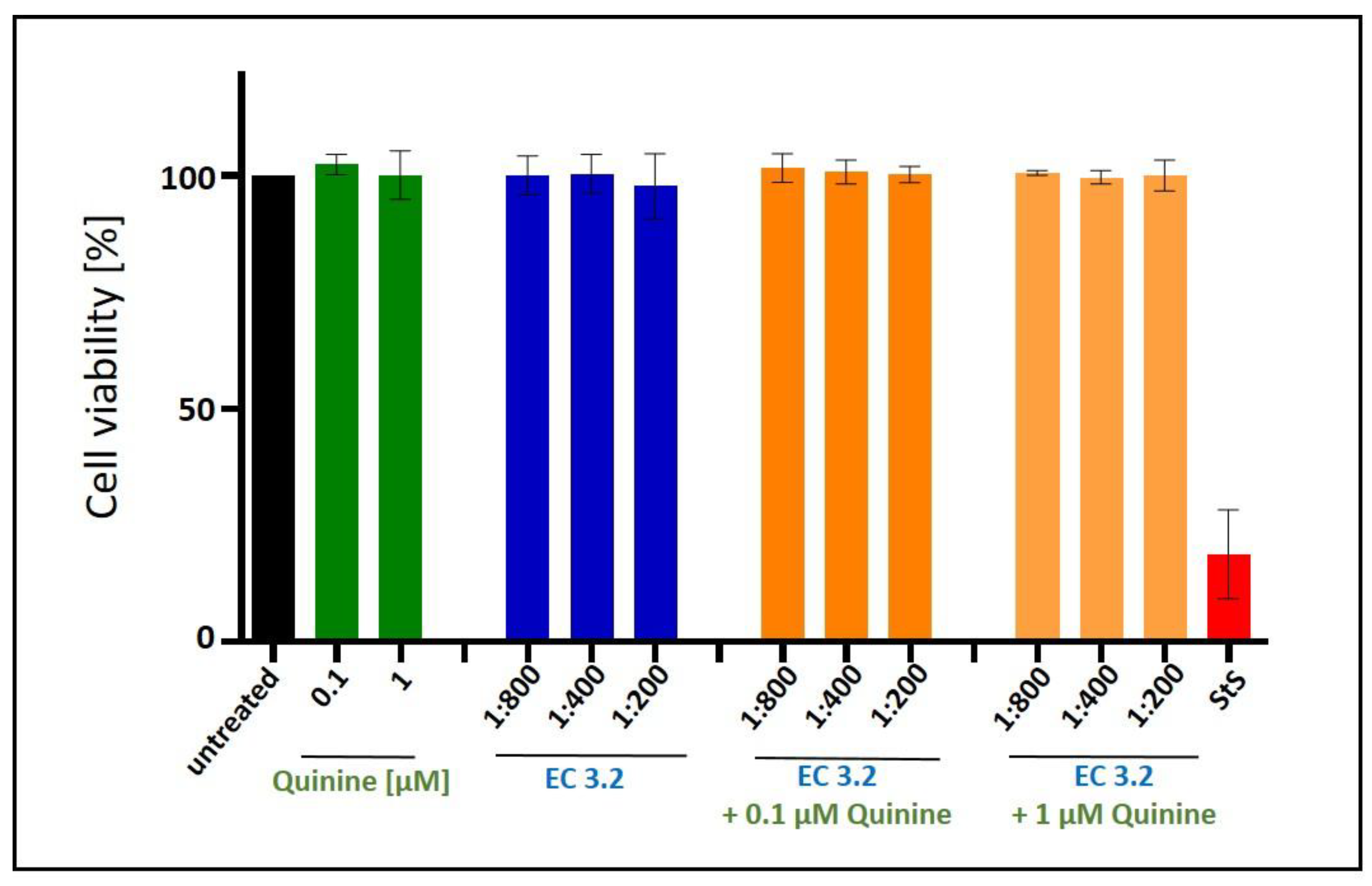

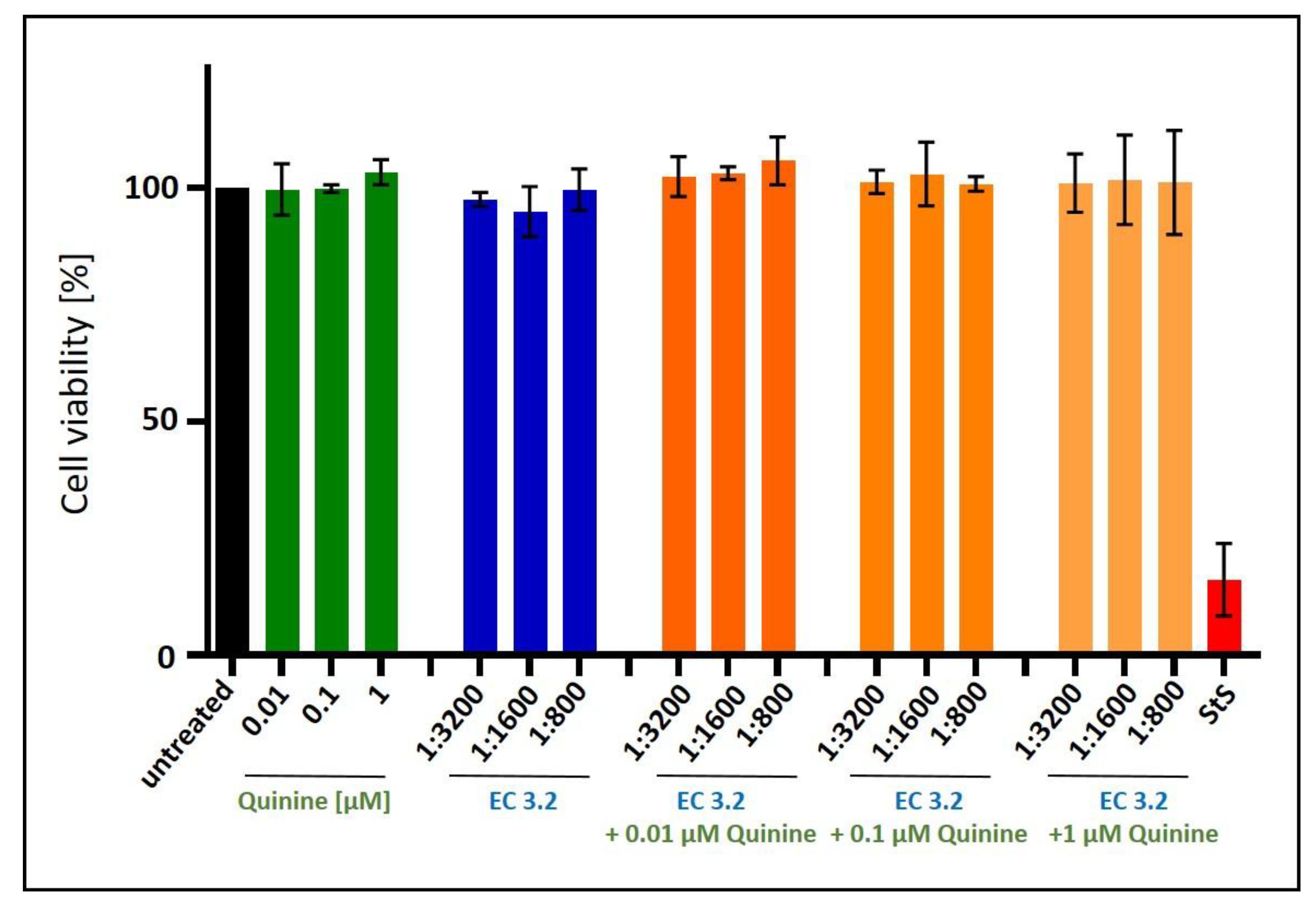

2.5. Assessment of Cell Viability

2.6. Determination of the Amount of Viral RNA Copies from Released Viruses by qRT-PCR

2.7. Software and Statistics

3. Results

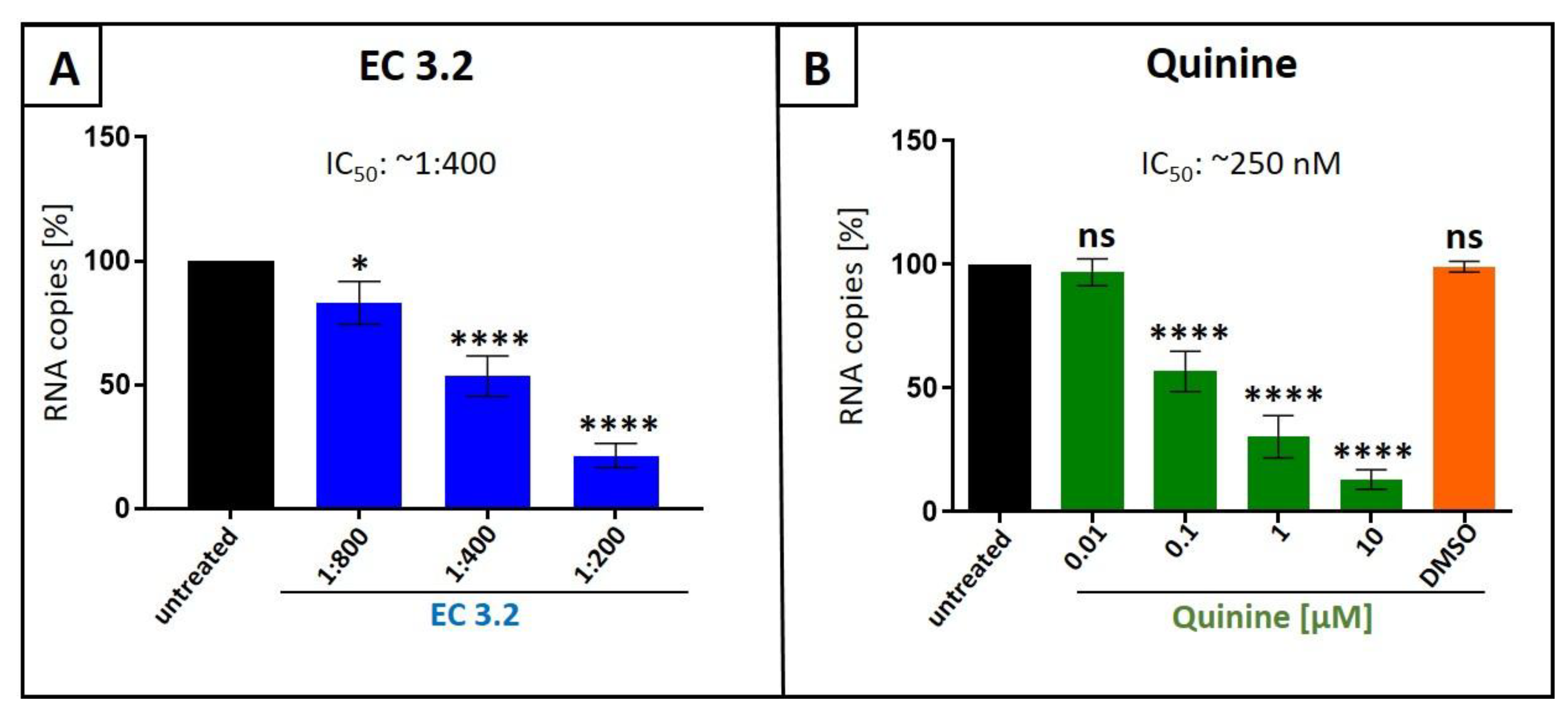

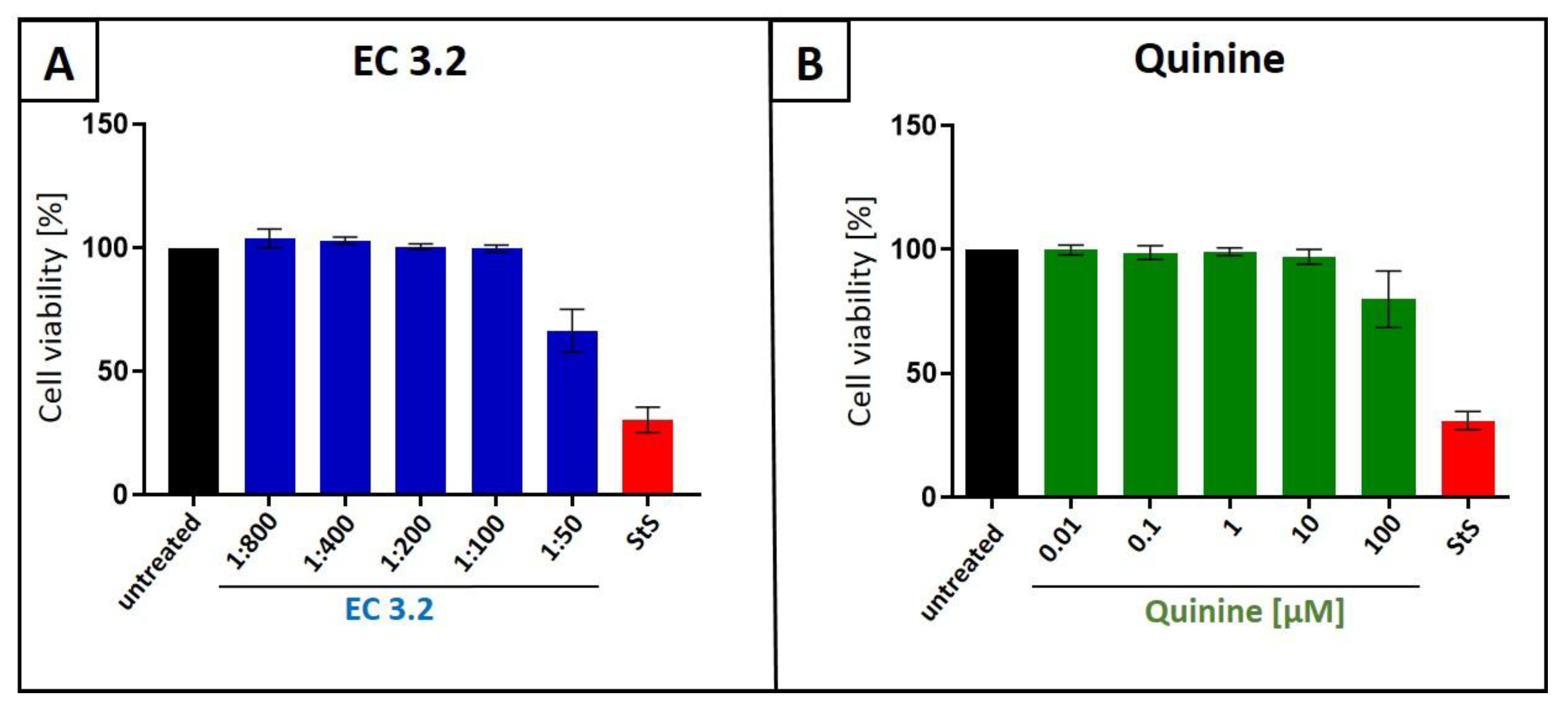

3.1. European Black Elderberry Fruit Extract and Quinine Exhibits Antiviral Activity Against Influenza A Virus in MDCKII Cells

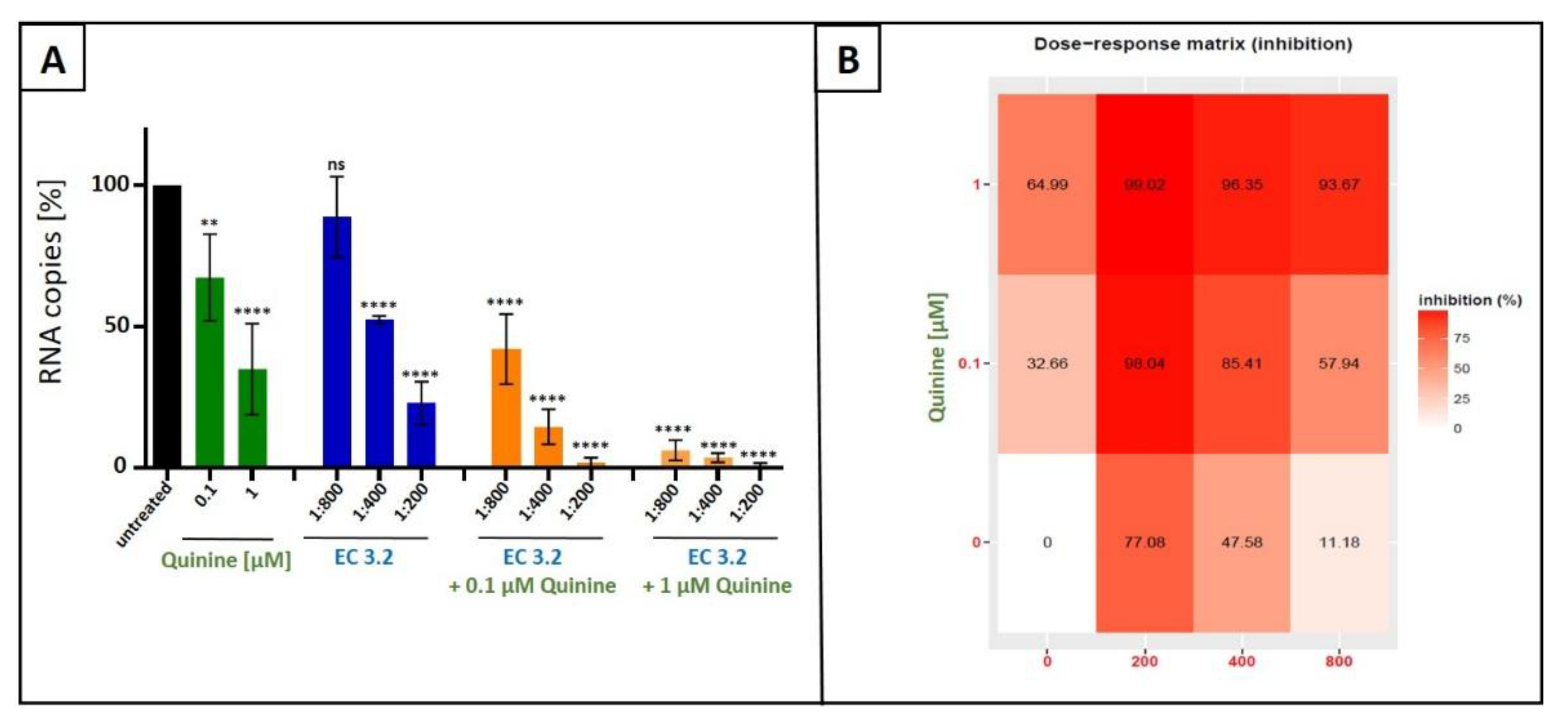

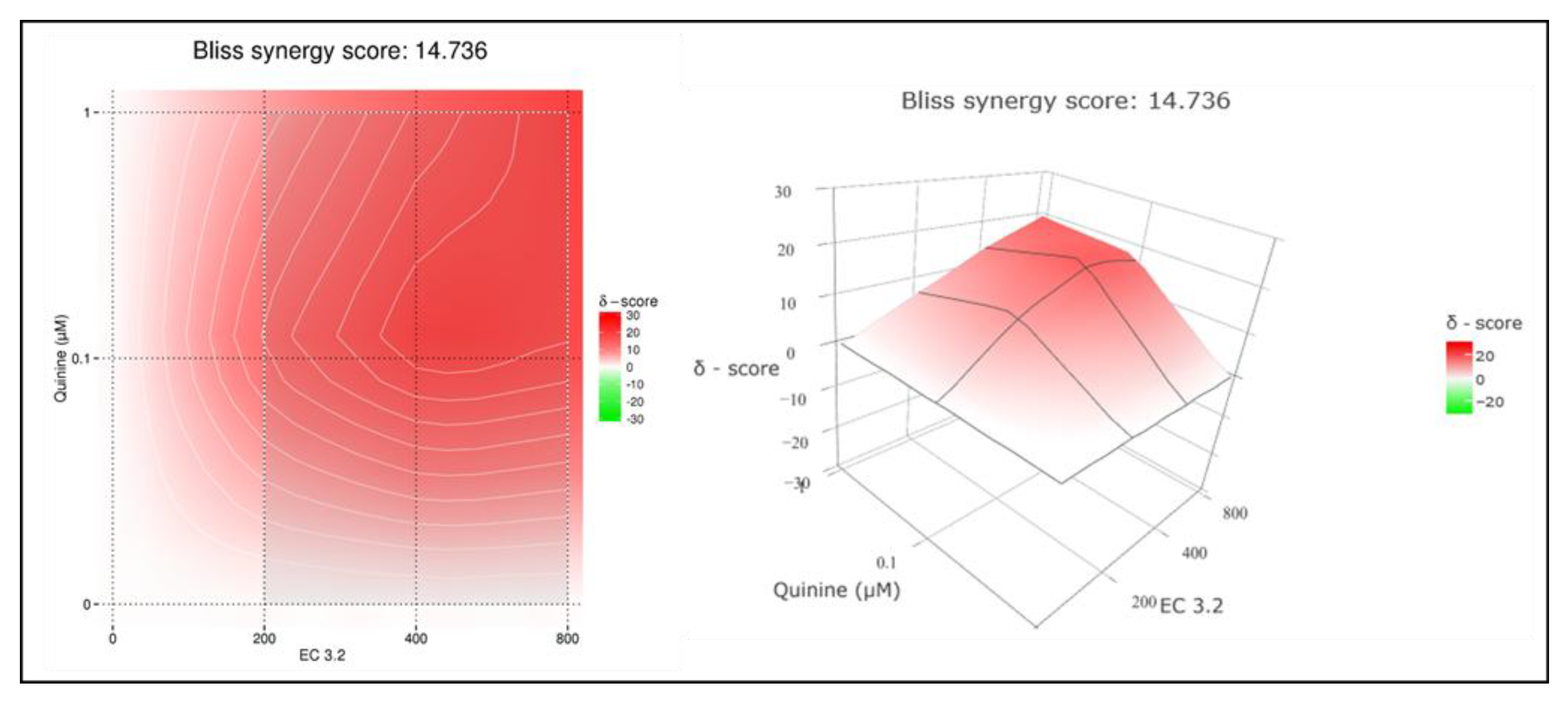

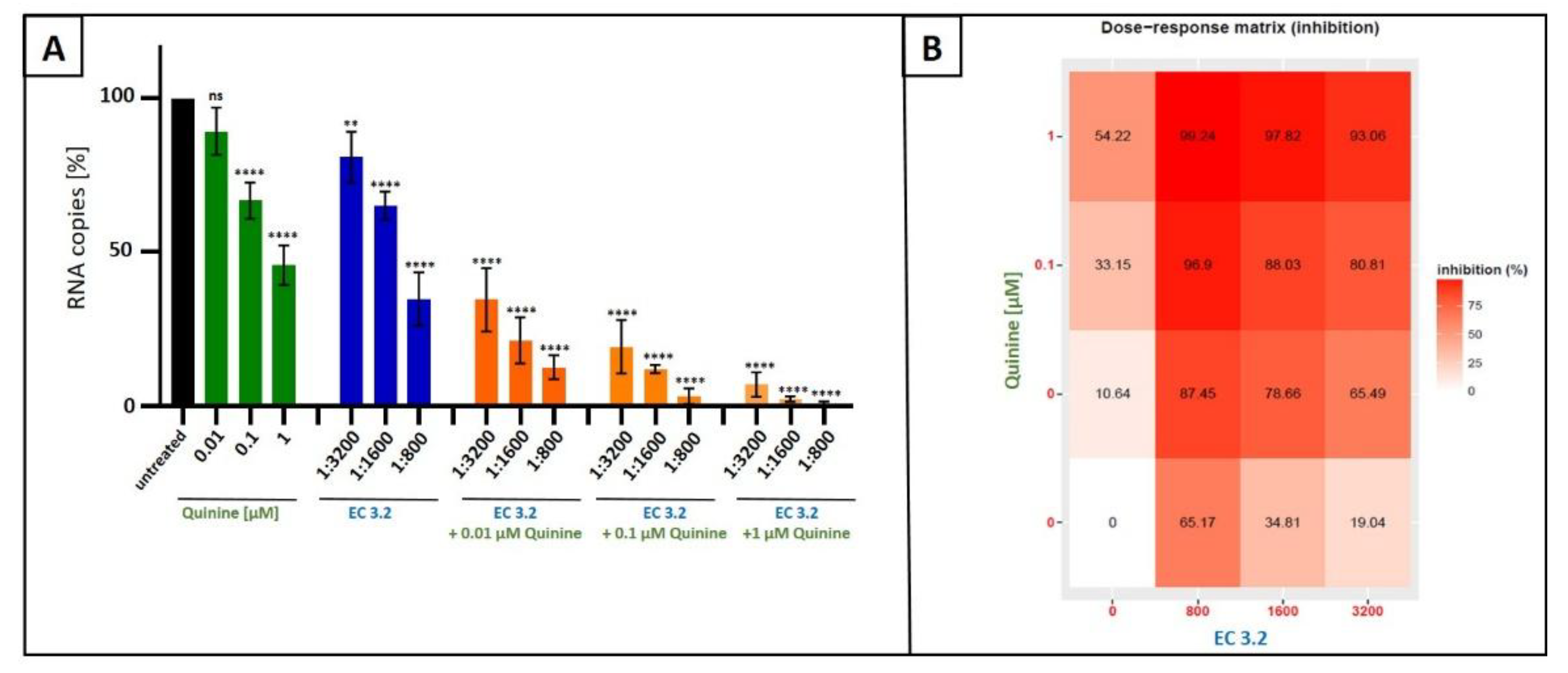

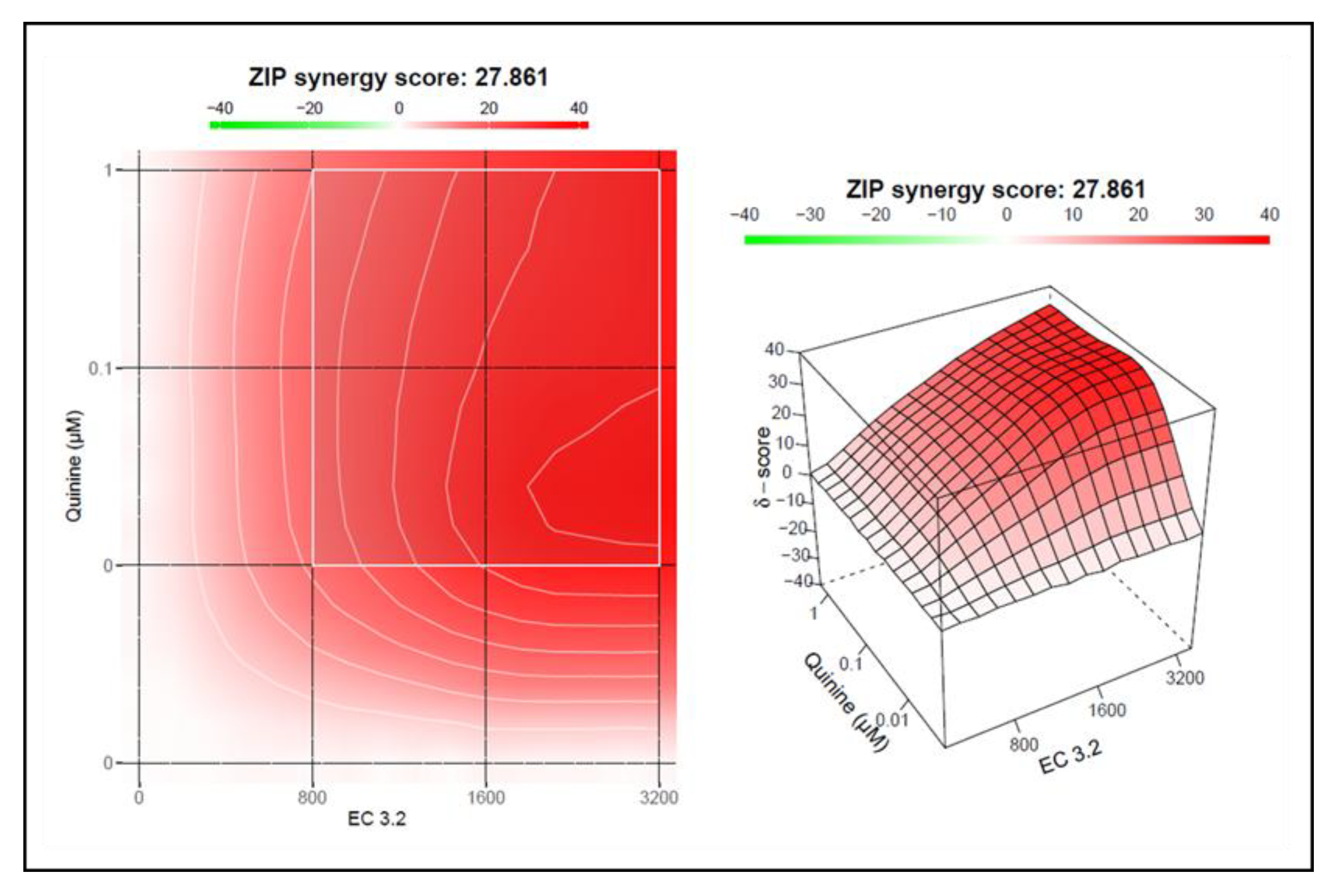

3.2. Combination Treatment with Black Elderberry Fruit Extract and Quinine Exhibits Synergistic Antiviral Activity Against IAV

3.3. Treatment with a Combination of European Black Elderberry Fruit Extract and Quinine Exhibits Synergistic Antiviral Activity Against SARS-CoV-2

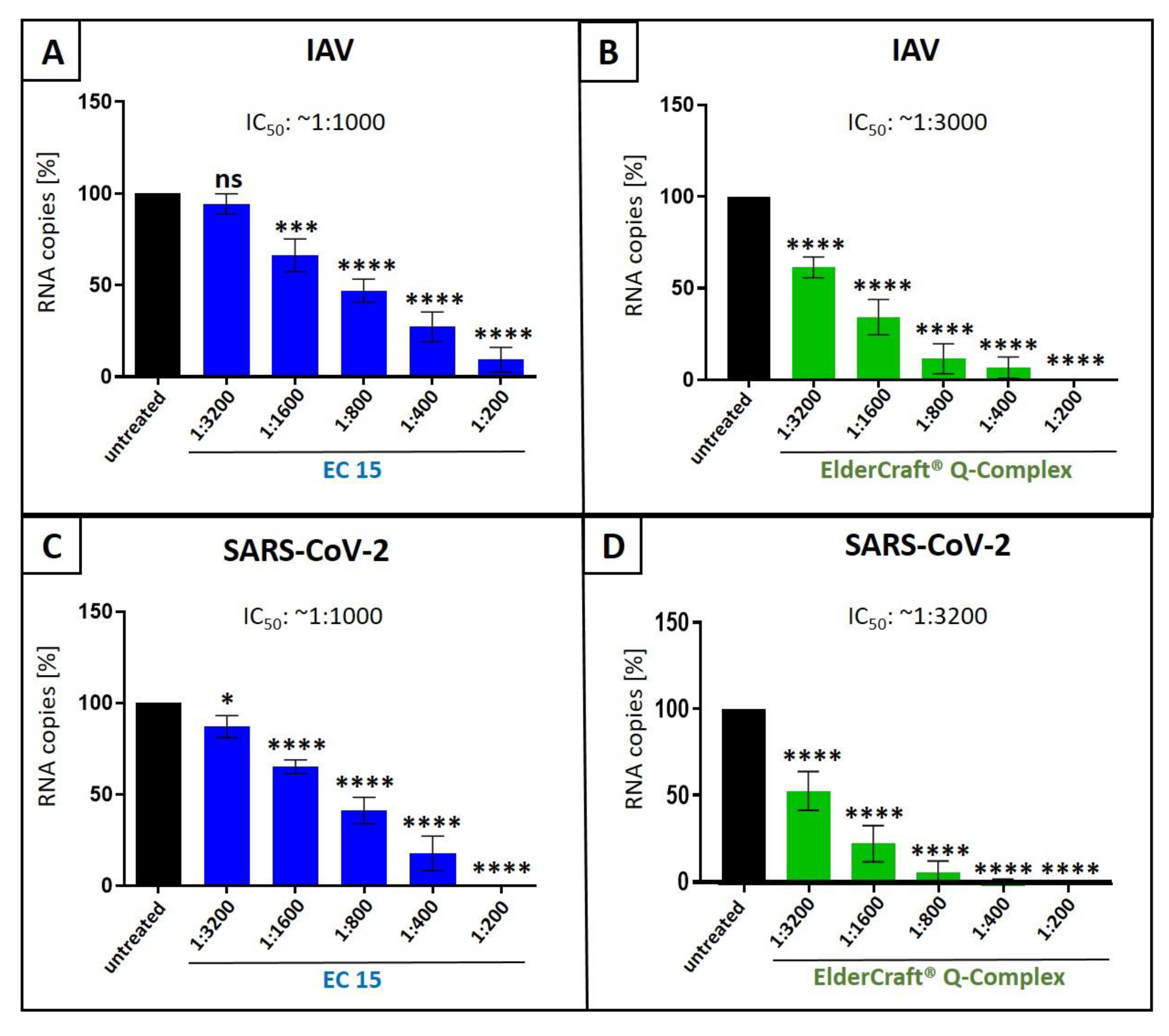

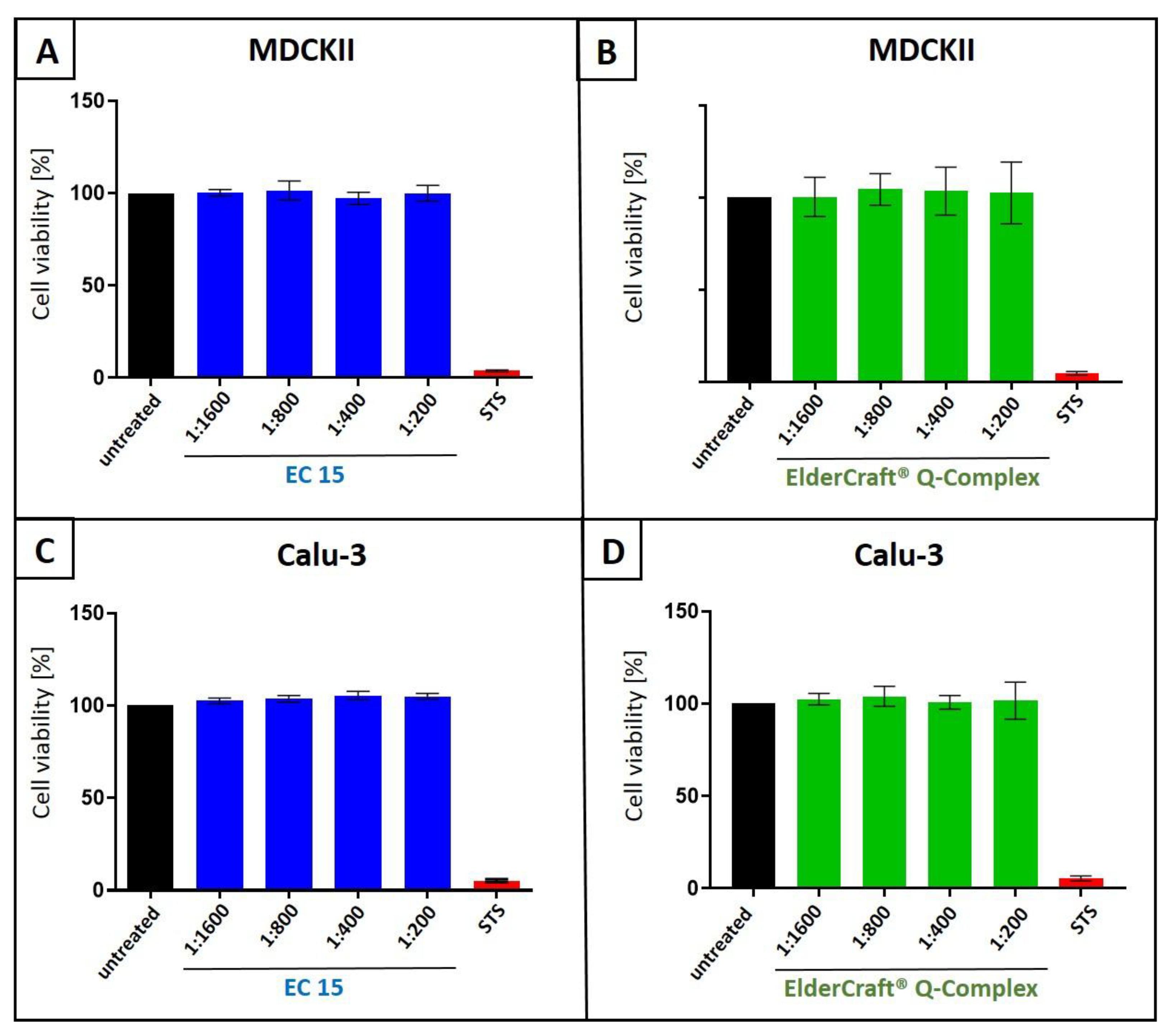

3.4. Antiviral Activity of ElderCraft® Q-Complex Against IAV and SARS-CoV-2 in Comparison to ElderCraft® Without Quinine

4. Discussion

5. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, B. A.; Jones, C. H.; Welch, V.; True, J. M. , Outlook of pandemic preparedness in a post-COVID-19 world. npj Vaccines 2023, (1), 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibmer, C. K.; Ayres, F.; Hermanus, T.; Madzivhandila, M.; Kgagudi, P.; Oosthuysen, B.; Lambson, B. E.; de Oliveira, T.; Vermeulen, M.; van der Berg, K.; Rossouw, T.; Boswell, M.; Ueckermann, V.; Meiring, S.; von Gottberg, A.; Cohen, C.; Morris, L.; Bhiman, J. N.; Moore, P. L., SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, (4), 622-625.

- Blumental, S.; Debré, P. , Challenges and Issues of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines. Frontiers in medicine 2021, 8, 664179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunagar, R.; Singh, A.; Kumar, S., SARS-CoV-2: Immunity, Challenges with Current Vaccines, and a Novel Perspective on Mucosal Vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, (4).

- Chan, J. F.-W.; Yuan, S.; Chu, H.; Sridhar, S.; Yuen, K.-Y. , COVID-19 drug discovery and treatment options. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2024, (7), 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanian, M.; Barary, M.; Ghebrehewet, S.; Koppolu, V.; Vasigala, V.; Ebrahimpour, S. , A brief review of influenza virus infection. Journal of medical virology 2021, (8), 4638–4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyeki, T. M.; Hui, D. S.; Zambon, M.; Wentworth, D. E.; Monto, A. S. , Influenza. The Lancet 2022, (10353), 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, L.; E, O. M.; Jordan, K.; Hawkshaw, S.; Marshall, L.; O’Neill, M.; Teljeur, C.; Ryan, M.; Carnahan, A.; Pérez Martín, J. J.; Robertson, A. H.; Johansen, K.; de Jonge, J.; Krause, T.; Nicolay, N.; Nohynek, H.; Pavlopoulou, I.; Pebody, R.; Penttinen, P.; Soler-Soneira, M.; Wichmann, O.; Harrington, P. , Systematic review of the efficacy, effectiveness and safety of high-dose seasonal influenza vaccines for the prevention of laboratory-confirmed influenza in individuals ≥18 years of age. Reviews in medical virology 2023, (3), e2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L., Plant-Derived Natural Products: A Source for Drug Discovery and Development. In Drugs and Drug Candidates, 2024; Vol. 3, pp 184-207.

- Dias, D. A.; Urban, S.; Roessner, U. , A historical overview of natural products in drug discovery. Metabolites 2012, (2), 303–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A. G.; Zotchev, S. B.; Dirsch, V. M.; Orhan, I. E.; Banach, M.; Rollinger, J. M.; Barreca, D.; Weckwerth, W.; Bauer, R.; Bayer, E. A.; et al. Natural products in drug discovery: advances and opportunities. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2021, (3), 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.; Baker, C.; Cherry, L.; Dunne, E. , Black elderberry (Sambucus nigra) supplementation effectively treats upper respiratory symptoms: A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials. Complementary therapies in medicine 2019, 42, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiralongo, E.; Wee, S. S.; Lea, R. A. , Elderberry Supplementation Reduces Cold Duration and Symptoms in Air-Travellers: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2016, (4), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakay-Rones, Z.; Thom, E.; Wollan, T.; Wadstein, J. , Randomized study of the efficacy and safety of oral elderberry extract in the treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. The Journal of international medical research 2004, (2), 132–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, E.; Hayashi, K.; Katayama, H.; Hayashi, T.; Obata, A., Anti-influenza virus effects of elderberry juice and its fractions. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 2012, 76, (9), 1633-8.

- Setz, C.; Fröba, M.; Große, M.; Rauch, P.; Auth, J.; Steinkasserer, A.; Plattner, S.; Schubert, U. , European Black Elderberry Fruit Extract Inhibits Replication of SARS-CoV-2 In Vitro. Nutraceuticals 2023, (1), 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zuckerman, D. M.; Brantley, S.; Sharpe, M.; Childress, K.; Hoiczyk, E.; Pendleton, A. R. , Sambucus nigra extracts inhibit infectious bronchitis virus at an early point during replication. BMC veterinary research 2014, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, K.; Dyason, J. C.; Maggioni, A.; von Itzstein, M.; Downard, K. M. , Binding of a natural anthocyanin inhibitor to influenza neuraminidase by mass spectrometry. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2013, (20), 6563–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschek, B., Jr.; Fink, R. C.; McMichael, M. D.; Li, D.; Alberte, R. S. , Elderberry flavonoids bind to and prevent H1N1 infection in vitro. Phytochemistry 2009, (10), 1255–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Große, M.; Ruetalo, N.; Layer, M.; Hu, D.; Businger, R.; Rheber, S.; Setz, C.; Rauch, P.; Auth, J.; Fröba, M.; Brysch, E.; Schindler, M.; Schubert, U., Quinine Inhibits Infection of Human Cell Lines with SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 2021,13, (4).

- Latarissa, I. R.; Barliana, M. I.; Meiliana, A.; Lestari, K., Potential of Quinine Sulfate for COVID-19 Treatment and Its Safety Profile: Review. Clinical pharmacology : advances and applications 2021, 13, 225-234.

- Miller, L. H.; Rojas-Jaimes, J.; Low, L. M.; Corbellini, G. , What Historical Records Teach Us about the Discovery of Quinine. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2023, (1), 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achan, J.; Talisuna, A. O.; Erhart, A.; Yeka, A.; Tibenderana, J. K.; Baliraine, F. N.; Rosenthal, P. J.; D’Alessandro, U. , Quinine, an old anti-malarial drug in a modern world: role in the treatment of malaria. Malaria journal 2011, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. A.; Al-Balushi, K. , Combating COVID-19: The role of drug repurposing and medicinal plants. Journal of infection and public health 2021, (4), 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, S.; Sreelatha, L.; Dechtawewat, T.; Noisakran, S.; Yenchitsomanus, P.-t.; Chu, J. J. H.; Limjindaporn, T. , Drug repurposing of quinine as antiviral against dengue virus infection. Virus Research 2018, 255, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, S.; Scaccabarozzi, D.; Signorini, L.; Perego, F.; Ilboudo, D. P.; Ferrante, P.; Delbue, S., The Use of Antimalarial Drugs against Viral Infection. Microorganisms 2020, 8, (1).

- Baroni, A.; Paoletti, I.; Ruocco, E.; Ayala, F.; Corrado, F.; Wolf, R.; Tufano, M. A.; Donnarumma, G. , Antiviral effects of quinine sulfate on HSV-1 HaCat cells infected: Analysis of the molecular mechanisms involved. Journal of Dermatological Science 2007, (3), 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeler, A. O.; Graessle, O.; Ott, W. H. , Effect of Quinine on Influenza Virus Infections in Mice. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 1946, (2), 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, L. J. M., H. , A Simple Method Of Estimating Fifty Per Cent Endpoints. American Journal of Epidemiology 1936, (3), 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Corman, V. M.; Landt, O.; Kaiser, M.; Molenkamp, R.; Meijer, A.; Chu, D. K.; Bleicker, T.; Brünink, S.; Schneider, J.; Schmidt, M. L.; Mulders, D. G.; Haagmans, B. L.; van der Veer, B.; van den Brink, S.; Wijsman, L.; Goderski, G.; Romette, J. L.; Ellis, J.; Zambon, M.; Peiris, M.; Goossens, H.; Reusken, C.; Koopmans, M. P.; Drosten, C., Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2020, 25, (3).

- Ianevski, A.; He, L.; Aittokallio, T.; Tang, J., SynergyFinder: a web application for analyzing drug combination dose-response matrix data. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2017, 33, (15), 2413-2415.

- Liu, Q.; Yin, X.; Languino, L. R.; Altieri, D. C. , Evaluation of drug combination effect using a Bliss independence dose-response surface model. Statistics in biopharmaceutical research 2018, (2), 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaush, C. R.; Hard, W. L.; Smith, T. F., Characterization of an established line of canine kidney cells (MDCK). Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1966, 122, (3), 931-5.

- Wit, E. d.; Spronken, M. I. J.; Bestebroer, T. M.; Rimmelzwaan, G. F.; Osterhaus, A. D. M. E.; Fouchier, R. A. M. , Efficient generation and growth of influenza virus A/PR/8/34 from eight cDNA fragments. Virus Research 2004, (1), 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morán-Santibañez, K.; Peña-Hernández, M. A.; Cruz-Suárez, L. E.; Ricque-Marie, D.; Skouta, R.; Vasquez, A. H.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C.; Trejo-Avila, L. M., Virucidal and Synergistic Activity of Polyphenol-Rich Extracts of Seaweeds against Measles Virus. Viruses 2018, 10, (9).

- Aguiar, J. A.; Tremblay, B. J.; Mansfield, M. J.; Woody, O.; Lobb, B.; Banerjee, A.; Chandiramohan, A.; Tiessen, N.; Cao, Q.; Dvorkin-Gheva, A.; Revill, S.; Miller, M. S.; Carlsten, C.; Organ, L.; Joseph, C.; John, A.; Hanson, P.; Austin, R. C.; McManus, B. M.; Jenkins, G.; Mossman, K.; Ask, K.; Doxey, A. C.; Hirota, J. A. , Gene expression and in situ protein profiling of candidate SARS-CoV-2 receptors in human airway epithelial cells and lung tissue. The European respiratory journal.

- Owen, L.; Laird, K.; Shivkumar, M. , Antiviral plant-derived natural products to combat RNA viruses: Targets throughout the viral life cycle. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2022, (3), 476–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarra-Pizzo, M.; Pennisi, R.; Ben-Amor, I.; Mandalari, G.; Sciortino, M. T., Antiviral Activity Exerted by Natural Products against Human Viruses. Viruses 2021, 13, (5).

- Antonelli, G.; Turriziani, O. , Antiviral therapy: old and current issues. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2012, (2), 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, B.; Kartal, M.; Orhan, I. , Cytotoxicity, antiviral and antimicrobial activities of alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. Pharmaceutical Biology 2011, (4), 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Pour, P.; Fakhri, S.; Asgary, S.; Farzaei, M. H.; Echeverría, J. , The Signaling Pathways, and Therapeutic Targets of Antiviral Agents: Focusing on the Antiviral Approaches and Clinical Perspectives of Anthocyanins in the Management of Viral Diseases. Frontiers in pharmacology 2019, 10, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassauer, A.; Weinmuellner, R.; Meier, C.; Pretsch, A.; Prieschl-Grassauer, E.; Unger, H. , Iota-Carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of rhinovirus infection. Virol J 2008, 5, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibbrandt, A.; Meier, C.; König-Schuster, M.; Weinmüllner, R.; Kalthoff, D.; Pflugfelder, B.; Graf, P.; Frank-Gehrke, B.; Beer, M.; Fazekas, T.; Unger, H.; Prieschl-Grassauer, E.; Grassauer, A. , Iota-carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of influenza A virus infection. PloS one 2010, (12), e14320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morokutti-Kurz, M.; Graf, C.; Prieschl-Grassauer, E. , Amylmetacresol/2,4-dichlorobenzyl alcohol, hexylresorcinol, or carrageenan lozenges as active treatments for sore throat. Int J Gen Med 2017, 10, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morokutti-Kurz, M.; Fröba, M.; Graf, P.; Große, M.; Grassauer, A.; Auth, J.; Schubert, U.; Prieschl-Grassauer, E. , Iota-carrageenan neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 and inhibits viral replication in vitro. PLOS ONE 2021, (2), e0237480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, D.; Conzelmann, C.; Fois, G.; Groß, R.; Weil, T.; Wettstein, L.; Stenger, S.; Zelikin, A.; Hoffmann, T. K.; Frick, M.; Müller, J. A.; Münch, J., Carrageenan-containing over-the-counter nasal and oral sprays inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection of airway epithelial cultures. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 2021, 320, (5), L750-L756.

- Fröba, M.; Große, M.; Setz, C.; Rauch, P.; Auth, J.; Spanaus, L.; Münch, J.; Ruetalo, N.; Schindler, M.; Morokutti-Kurz, M.; Graf, P.; Prieschl-Grassauer, E.; Grassauer, A.; Schubert, U., Iota-Carrageenan Inhibits Replication of SARS-CoV-2 and the Respective Variants of Concern Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, (24).

- Figueroa, J. M.; Lombardo, M. E.; Dogliotti, A.; Flynn, L. P.; Giugliano, R.; Simonelli, G.; Valentini, R.; Ramos, A.; Romano, P.; Marcote, M.; Michelini, A.; Salvado, A.; Sykora, E.; Kniz, C.; Kobelinsky, M.; Salzberg, D. M.; Jerusalinsky, D.; Uchitel, O. , Efficacy of a Nasal Spray Containing Iota-Carrageenan in the Postexposure Prophylaxis of COVID-19 in Hospital Personnel Dedicated to Patients Care with COVID-19 Disease. Int J Gen Med 2021, 14, 6277–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahla, R. E.; Medina Ruiz, L.; Ortega, E. S.; Morales Rn, M. F.; Barreiro, F.; George, A.; Mancilla Rn, C.; S, D. A. R.; Barrenechea, G.; Goroso, D. G.; Peral de Bruno, M. , Intensive Treatment With Ivermectin and Iota-Carrageenan as Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for COVID-19 in Health Care Workers From Tucuman, Argentina. Am J Ther 2021, (5), e601–e604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhi, V. P.; Sriramavaratharajan, V.; Murugan, R.; Masilamani, P.; Gurav, S. S.; Sarasu, V. P.; Parthiban, S.; Ayyanar, M., Edible fruit extracts and fruit juices as potential source of antiviral agents: a review. Food Measure. 2021;15(6):5181-90. Epub 2021 Aug 3. [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, C.; Basch, E.; Cheung, L.; Goldberg, H.; Hammerness, P.; Isaac, R.; Khalsa, K. P.; Romm, A.; Rychlik, I.; Varghese, M.; Weissner, W.; Windsor, R. C.; Wortley, J. , An evidence-based systematic review of elderberry and elderflower (Sambucus nigra) by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. Journal of dietary supplements 2014, (1), 80–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakay-Rones, Z.; Varsano, N.; Zlotnik, M.; Manor, O.; Regev, L.; Schlesinger, M.; Mumcuoglu, M., Inhibition of several strains of influenza virus in vitro and reduction of symptoms by an elderberry extract (Sambucus nigra L.) during an outbreak of influenza B Panama. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.) 1995, 1, (4), 361-9.

- Krawitz, C.; Mraheil, M. A.; Stein, M.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Domann, E.; Pleschka, S.; Hain, T. , Inhibitory activity of a standardized elderberry liquid extract against clinically-relevant human respiratory bacterial pathogens and influenza A and B viruses. BMC complementary and alternative medicine 2011, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R. S.; Bode, R. F., A Review of the Antiviral Properties of Black Elder (Sambucus nigra L.) Products. Phytotherapy research : PTR 2017, 31, (4), 533-554.

- Swaminathan, K.; Müller, P.; Downard, K. M. , Substituent effects on the binding of natural product anthocyanidin inhibitors to influenza neuraminidase with mass spectrometry. Analytica chimica acta 2014, 828, 61–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stich, L.; Plattner, S.; McDougall, G.; Austin, C.; Steinkasserer, A., Polysaccharides from European Black Elderberry Extract Enhance Dendritic Cell Mediated T Cell Immune Responses. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, (7).

- Ho, G. T.; Ahmed, A.; Zou, Y. F.; Aslaksen, T.; Wangensteen, H.; Barsett, H. , Structure-activity relationship of immunomodulating pectins from elderberries. Carbohydrate polymers 2015, 125, 314–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, P. G.; Mungthin, M.; Hastings, I. M.; Biagini, G. A.; Saidu, D. K.; Lakshmanan, V.; Johnson, D. J.; Hughes, R. H.; Stocks, P. A.; O’Neill, P. M.; Fidock, D. A.; Warhurst, D. C.; Ward, S. A. , PfCRT and the trans-vacuolar proton electrochemical gradient: regulating the access of chloroquine to ferriprotoporphyrin IX. Molecular microbiology 2006, (1), 238–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauthe, M.; Orhon, I.; Rocchi, C.; Zhou, X.; Luhr, M.; Hijlkema, K. J.; Coppes, R. P.; Engedal, N.; Mari, M.; Reggiori, F. , Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy 2018, (8), 1435–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraha, R. V.; Ridwansyah, H.; Ghozali, M.; Khairani, A. F.; Atik, N., Traditional Herbal Medicine Candidates as Complementary Treatments for COVID-19: A Review of Their Mechanisms, Pros and Cons. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2020, 2020, (1), 2560645.

- Savarino, A.; Boelaert, J. R.; Cassone, A.; Majori, G.; Cauda, R. , Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today’s diseases? The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2003, (11), 722–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- law, E. U. Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on flavourings and certain food ingredients with flavouring properties for use in and on foods and amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 1601/91, Regulations (EC) No 2232/96 and (EC) No 110/2008 and Directive 2000/13/EC. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02008R1334-20190521.

- Hall, A. P.; Czerwinski, A. W.; Madonia, E. C.; Evensen, K. L. , Human plasma and urine quinine levels following tablets, capsules, and intravenous infusion. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 1973, (4), 580–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyinka, J. O.; Onyeji, C. O.; Omoruyi, S. I.; Owolabi, A. R.; Sarma, P. V.; Cook, J. M. , Effects of concurrent administration of nevirapine on the disposition of quinine in healthy volunteers. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology 2009, (4), 439–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shyr, Z. A.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Lo, D. C.; Zheng, W. , Drug combination therapy for emerging viral diseases. Drug Discovery Today 2021, (10), 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, G.; Salam, A.; Horby, P.; Hayden, F. G.; Chen, C.; Pan, J.; Zheng, J.; Lu, B.; Guo, L.; Wang, C.; Cao, B.; Network, C.-A. P. C. , Comparative Effectiveness of Combined Favipiravir and Oseltamivir Therapy Versus Oseltamivir Monotherapy in Critically Ill Patients With Influenza Virus Infection. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019, (10), 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulon, R.; Mazeaud, C.; Farahani, M. D.; Broquière, M.; Iddir, M.; Charpentier, T.; Anton, A.; Ayotte, Y.; Woo, S.; Lamarre, A.; Chatel-Chaix, L.; LaPlante, S. R., Repurposing Drugs and Synergistic Combinations as Potential Therapies for Inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 and Coronavirus Replication. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 2024.

- Cho, W.-K.; Lee, M.-M.; Ma, J. Y. , Antiviral Effect of Isoquercitrin against Influenza A Viral Infection via Modulating Hemagglutinin and Neuraminidase. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, (21), 13112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, V.; Brognaro, H.; Prabhu, P. R.; de Souza, E. E.; Günther, S.; Reinke, P. Y. A.; Lane, T. J.; Ginn, H.; Han, H.; Ewert, W.; Sprenger, J.; Koua, F. H. M.; Falke, S.; Werner, N.; Andaleeb, H.; Ullah, N.; Franca, B. A.; Wang, M.; Barra, A. L. C.; Perbandt, M.; Schwinzer, M.; Schmidt, C.; Brings, L.; Lorenzen, K.; Schubert, R.; Machado, R. R. G.; Candido, E. D.; Oliveira, D. B. L.; Durigon, E. L.; Niebling, S.; Garcia, A. S.; Yefanov, O.; Lieske, J.; Gelisio, L.; Domaracky, M.; Middendorf, P.; Groessler, M.; Trost, F.; Galchenkova, M.; Mashhour, A. R.; Saouane, S.; Hakanpää, J.; Wolf, M.; Alai, M. G.; Turk, D.; Pearson, A. R.; Chapman, H. N.; Hinrichs, W.; Wrenger, C.; Meents, A.; Betzel, C. , Antiviral activity of natural phenolic compounds in complex at an allosteric site of SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease. Communications Biology 2022, (1), 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, A.; Brunton, N. P.; O’Donnell, C.; Tiwari, B. K., Effect of thermal processing on anthocyanin stability in foods; mechanisms and kinetics of degradation. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2010, 21, (1), 3-11.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).