Submitted:

22 February 2025

Posted:

24 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

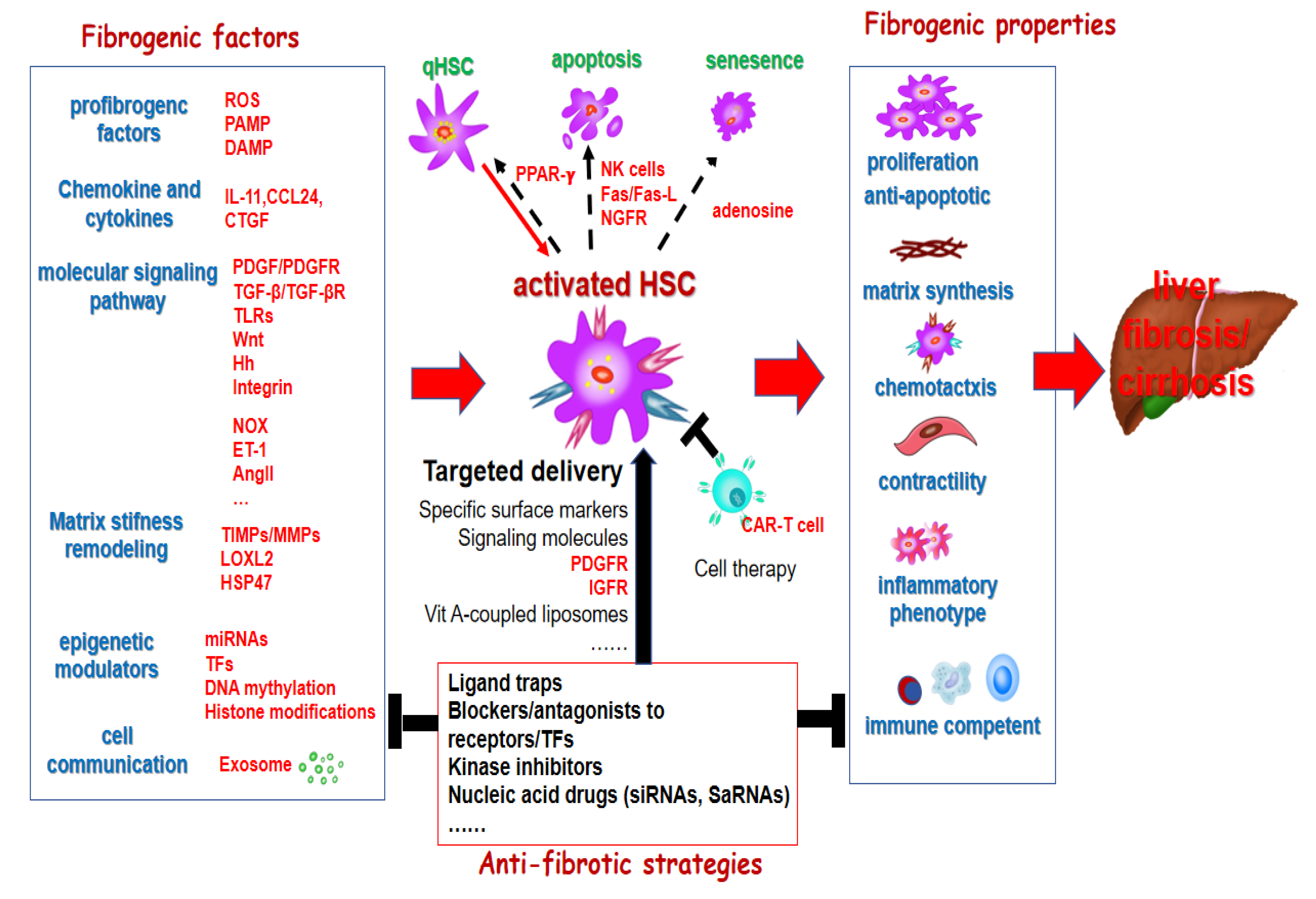

2. The Role of Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSC) in Liver Cirrhosis and HCC

2.1. HSC and Liver Fibrosis

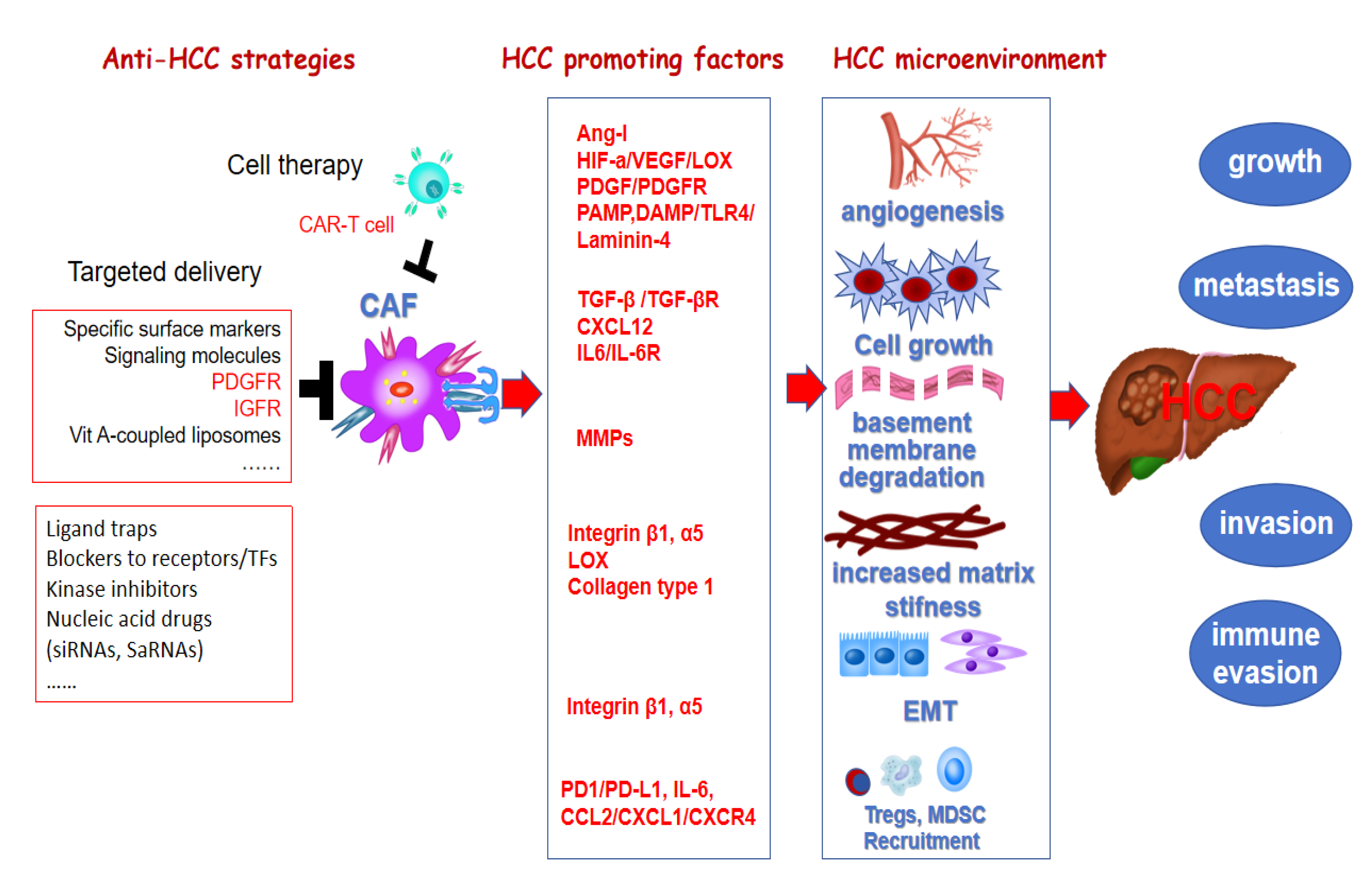

2.2. CAF and HCC

3. Targeting HSC for the Prevention and Treatment of Liver Cirrhosis

3.1. Molecular Signaling Pathways Associated with HSC/MFB Activation

3.1.1. Reactive Oxygen Radicals (ROS)

3.1.2. TOLL-like Receptors (TLRs)

3.1.3. Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

3.1.4. Wnt Signaling Pathway

3.1.5. Chemokine and Cytokine

3.2. Molecular Signaling Pathways Associated with HSC/MFB Proliferation

3.3. Molecular Signaling Pathways Associated with Pro-Liver Fibrosis

3.3.1. Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β)

3.3.2. FAP

3.3.3. Cannabinoid Receptors (CB)

3.4. Molecular Signaling Pathways Associated with HSC/MFB Contraction Responses

3.5. Molecular Signaling Pathways Associated with Reversal of Liver Fibrosis

3.5.1. Activated HSC Return to Resting Molecular Signaling Pathways

3.5.2. Molecular Signaling Pathways That Induce Apoptosis and Senescence of Activated-HSC/MFB

3.6. ECM and Liver Fibrosis

3.7. Epigenetic Regulation Associated with Liver Fibrosis

3.7.1. DNA Methylation and Related Histone Modifications

3.7.2. MicroRNAs

3.8. Cell Therapies to Treat Fibrosis

4. Targeting Hepatic Stellate Cells for the Prevention and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

4.1. Angiogenesis Provide Basic Survival and Metastasis Condition of Tumor Cells

4.2. Matrix Stiffness Promotes Tumor Growth, Invasion and Metastasis

4.3. Matrix Remodeling via MMP/TIMPs Are Crucial for Tumor Invasion and Metastasis

4.4. Reprogramming of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts

5. Translational Barriers in Targeting HSC for Anti-Fibrosis and Anti-Tumor Therapy

5.1. Heterogeneity of HSC

5.2. Lack of Specific Targeted Methods for HSC

5.3. Barriers to the Translation of Basic Research into Clinical Practice

6. Promoting Targeted Hepatic Stellate Cell-Based Strategies for the Prevention and Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

6.1. Utilizing New Omics Technologies to Identify Markers and Therapeutic Targets for Activated HSCs

6.2. Receptor-Mediated Targeted Treatment Strategies for HSC and Clinical Translation

6.3. Design and Progress of Peptide Drugs

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ginès, P., A. Krag, J. G. Abraldes, E. Solà, N. Fabrellas, and P. S. Kamath. "Liver Cirrhosis." Lancet 398, no. 10308 (2021): 1359-76.

- Marcellin, P. , and B. K. Kutala. "Liver Diseases: A Major, Neglected Global Public Health Problem Requiring Urgent Actions and Large-Scale Screening." Liver Int 38 Suppl 1 (2018): 2-6.

- Wang, S. S., X. T. Tang, M. Lin, J. Yuan, Y. J. Peng, X. Yin, G. Shang, G. Ge, Z. Ren, and B. O. Zhou. "Perivenous Stellate Cells Are the Main Source of Myofibroblasts and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Formed after Chronic Liver Injuries." Hepatology 74, no. 3 (2021): 1578-94.

- Mederacke, I., C. C. Hsu, J. S. Troeger, P. Huebener, X. Mu, D. H. Dapito, J. P. Pradere, and R. F. Schwabe. "Fate Tracing Reveals Hepatic Stellate Cells as Dominant Contributors to Liver Fibrosis Independent of Its Aetiology." Nat Commun 4 (2013): 2823.

- Friedman, S. L. "Hepatic Stellate Cells: Protean, Multifunctional, and Enigmatic Cells of the Liver." Physiol Rev 88, no. 1 (2008): 125-72.

- Guo, J. , and S. L. Friedman. "Hepatic Fibrogenesis." Semin Liver Dis 27, no. 4 (2007): 413-26.

- Barry, A. E., R. Baldeosingh, R. Lamm, K. Patel, K. Zhang, D. A. Dominguez, K. J. Kirton, A. P. Shah, and H. Dang. "Hepatic Stellate Cells and Hepatocarcinogenesis." Front Cell Dev Biol 8 (2020): 709.

- Bárcena, C., M. Stefanovic, A. Tutusaus, G. A. Martinez-Nieto, L. Martinez, C. García-Ruiz, A. de Mingo, J. Caballeria, J. C. Fernandez-Checa, M. Marí, and A. Morales. "Angiogenin Secretion from Hepatoma Cells Activates Hepatic Stellate Cells to Amplify a Self-Sustained Cycle Promoting Liver Cancer." Sci Rep 5 (2015): 7916.

- Santamato, A., E. Fransvea, F. Dituri, A. Caligiuri, M. Quaranta, T. Niimi, M. Pinzani, S. Antonaci, and G. Giannelli. "Hepatic Stellate Cells Stimulate Hcc Cell Migration Via Laminin-5 Production." Clin Sci (Lond) 121, no. 4 (2011): 159-68.

- Lu, Y., J. Xu, S. Chen, Z. Zhou, and N. Lin. "Lipopolysaccharide Promotes Angiogenesis in Mice Model of Hcc by Stimulating Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation Via Tlr4 Pathway." Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 49, no. 11 (2017): 1029-34.

- Zhao, W., L. Zhang, Y. Xu, Z. Zhang, G. Ren, K. Tang, P. Kuang, B. Zhao, Z. Yin, and X. Wang. "Hepatic Stellate Cells Promote Tumor Progression by Enhancement of Immunosuppressive Cells in an Orthotopic Liver Tumor Mouse Model." Lab Invest 94, no. 2 (2014): 182-91.

- Zhou, Z., Y. Hu, Y. Wu, Q. Qi, J. Wang, L. Chen, and F. Wang. "The Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Current Situation and Outlook." Mol Immunol 151 (2022): 218-30.

- Higashi, T., S. L. Friedman, and Y. Hoshida. "Hepatic Stellate Cells as Key Target in Liver Fibrosis." Adv Drug Deliv Rev 121 (2017): 27-42.

- Wiering, L., P. Subramanian, and L. Hammerich. "Hepatic Stellate Cells: Dictating Outcome in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease." Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 15, no. 6 (2023): 1277-92.

- Guo, J., J. Loke, F. Zheng, F. Hong, S. Yea, M. Fukata, M. Tarocchi, O. T. Abar, H. Huang, J. J. Sninsky, and S. L. Friedman. "Functional Linkage of Cirrhosis-Predictive Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of Toll-Like Receptor 4 to Hepatic Stellate Cell Responses." Hepatology 49, no. 3 (2009): 960-8.

- Zeng, Z., Y. Wu, Y. Cao, Z. Yuan, Y. Zhang, D. Y. Zhang, D. Hasegawa, S. L. Friedman, and J. Guo. "Slit2-Robo2 Signaling Modulates the Fibrogenic Activity and Migration of Hepatic Stellate Cells." Life Sci 203 (2018): 39-47.

- Seki, E. , and R. F. Schwabe. "Hepatic Inflammation and Fibrosis: Functional Links and Key Pathways." Hepatology 61, no. 3 (2015): 1066-79.

- Rockey, D. C. "Translating an Understanding of the Pathogenesis of Hepatic Fibrosis to Novel Therapies." Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11, no. 3 (2013): 224-31.e1-5.

- Zhang, Z., C. Lin, L. Peng, Y. Ouyang, Y. Cao, J. Wang, S. L. Friedman, and J. Guo. "High Mobility Group Box 1 Activates Toll Like Receptor 4 Signaling in Hepatic Stellate Cells." Life Sci 91, no. 5-6 (2012): 207-12.

- Guo, J. , and S. L. Friedman. "Toll-Like Receptor 4 Signaling in Liver Injury and Hepatic Fibrogenesis." Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 3 (2010): 21.

- Bansal, M. B. , and N. Chamroonkul. "Antifibrotics in Liver Disease: Are We Getting Closer to Clinical Use?" Hepatol Int 13, no. 1 (2019): 25-39.

- Cannito, S., E. Novo, and M. Parola. "Therapeutic Pro-Fibrogenic Signaling Pathways in Fibroblasts." Adv Drug Deliv Rev 121 (2017): 57-84.

- Richter, K. , and T. Kietzmann. "Reactive Oxygen Species and Fibrosis: Further Evidence of a Significant Liaison." Cell Tissue Res 365, no. 3 (2016): 591-605.

- Liang, S., T. Kisseleva, and D. A. Brenner. "The Role of Nadph Oxidases (Noxs) in Liver Fibrosis and the Activation of Myofibroblasts." Front Physiol 7 (2016): 17.

- Crosas-Molist, E., E. Bertran, and I. Fabregat. "Cross-Talk between Tgf-Β and Nadph Oxidases during Liver Fibrosis and Hepatocarcinogenesis." Curr Pharm Des 21, no. 41 (2015): 5964-76.

- Liu, C., X. Chen, L. Yang, T. Kisseleva, D. A. Brenner, and E. Seki. "Transcriptional Repression of the Transforming Growth Factor Β (Tgf-Β) Pseudoreceptor Bmp and Activin Membrane-Bound Inhibitor (Bambi) by Nuclear Factor Κb (Nf-Κb) P50 Enhances Tgf-Β Signaling in Hepatic Stellate Cells." J Biol Chem 289, no. 10 (2014): 7082-91.

- Yang, J. J., H. Tao, and J. Li. "Hedgehog Signaling Pathway as Key Player in Liver Fibrosis: New Insights and Perspectives." Expert Opin Ther Targets 18, no. 9 (2014): 1011-21.

- Du, K., J. Hyun, R. T. Premont, S. S. Choi, G. A. Michelotti, M. Swiderska-Syn, G. D. Dalton, E. Thelen, B. S. Rizi, Y. Jung, and A. M. Diehl. "Hedgehog-Yap Signaling Pathway Regulates Glutaminolysis to Control Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells." Gastroenterology 154, no. 5 (2018): 1465-79.e13.

- El-Agroudy, N. N., R. N. El-Naga, R. A. El-Razeq, and E. El-Demerdash. "Forskolin, a Hedgehog Signalling Inhibitor, Attenuates Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Rats." Br J Pharmacol 173, no. 22 (2016): 3248-60.

- Lian, N., Y. Jiang, F. Zhang, H. Jin, C. Lu, X. Wu, Y. Lu, and S. Zheng. "Curcumin Regulates Cell Fate and Metabolism by Inhibiting Hedgehog Signaling in Hepatic Stellate Cells." Lab Invest 95, no. 7 (2015): 790-803.

- Moon, R. T., B. Bowerman, M. Boutros, and N. Perrimon. "The Promise and Perils of Wnt Signaling through Beta-Catenin." Science 296, no. 5573 (2002): 1644-6.

- Kweon, S. M., F. Chi, R. Higashiyama, K. Lai, and H. Tsukamoto. "Wnt Pathway Stabilizes Mecp2 Protein to Repress Ppar-Γ in Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells." PLoS One 11, no. 5 (2016): e0156111.

- Yu, F., Z. Lu, K. Huang, X. Wang, Z. Xu, B. Chen, P. Dong, and J. Zheng. "Microrna-17-5p-Activated Wnt/Β-Catenin Pathway Contributes to the Progression of Liver Fibrosis." Oncotarget 7, no. 1 (2016): 81-93.

- Lin, X., L. N. Kong, C. Huang, T. T. Ma, X. M. Meng, Y. He, Q. Q. Wang, and J. Li. "Hesperetin Derivative-7 Inhibits Pdgf-Bb-Induced Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Proliferation by Targeting Wnt/Β-Catenin Pathway." Int Immunopharmacol 25, no. 2 (2015): 311-20.

- Dong, S., C. Wu, J. Hu, Q. Wang, S. Chen, Zhirong Wang, and W. Xiong. "Wnt5a Promotes Cytokines Production and Cell Proliferation in Human Hepatic Stellate Cells Independent of Canonical Wnt Pathway." Clin Lab 61, no. 5-6 (2015): 537-47.

- Widjaja, A. A., B. K. Singh, E. Adami, S. Viswanathan, J. Dong, G. A. D'Agostino, B. Ng, W. W. Lim, J. Tan, B. S. Paleja, M. Tripathi, S. Y. Lim, S. G. Shekeran, S. P. Chothani, A. Rabes, M. Sombetzki, E. Bruinstroop, L. P. Min, R. A. Sinha, S. Albani, P. M. Yen, S. Schafer, and S. A. Cook. "Inhibiting Interleukin 11 Signaling Reduces Hepatocyte Death and Liver Fibrosis, Inflammation, and Steatosis in Mouse Models of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis." Gastroenterology 157, no. 3 (2019): 777-92.e14.

- Mor, A., S. Friedman, S. Hashmueli, A. Peled, M. Pinzani, M. Frankel, and R. Safadi. "Targeting Ccl24 in Inflammatory and Fibrotic Diseases: Rationale and Results from Three Cm-101 Phase 1 Studies." Drug Saf 47, no. 9 (2024): 869-81.

- De Lorenzis, E., A. Mor, R. L. Ross, S. Di Donato, R. Aricha, I. Vaknin, and F. Del Galdo. "Serum Ccl24 as a Biomarker of Fibrotic and Vascular Disease Severity in Systemic Sclerosis." Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 76, no. 9 (2024): 1269-77.

- Segal-Salto, M., N. Barashi, A. Katav, V. Edelshtein, A. Aharon, S. Hashmueli, J. George, Y. Maor, M. Pinzani, D. Haberman, A. Hall, S. Friedman, and A. Mor. "A Blocking Monoclonal Antibody to Ccl24 Alleviates Liver Fibrosis and Inflammation in Experimental Models of Liver Damage." JHEP Rep 2, no. 1 (2020): 100064.

- Borkham-Kamphorst, E. , and R. Weiskirchen. "The Pdgf System and Its Antagonists in Liver Fibrosis." Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 28 (2016): 53-61.

- Massagué, J. , and D. Sheppard. "Tgf-Β Signaling in Health and Disease." Cell 186, no. 19 (2023): 4007-37.

- Munger, J. S., X. Huang, H. Kawakatsu, M. J. Griffiths, S. L. Dalton, J. Wu, J. F. Pittet, N. Kaminski, C. Garat, M. A. Matthay, D. B. Rifkin, and D. Sheppard. "The Integrin Alpha V Beta 6 Binds and Activates Latent Tgf Beta 1: A Mechanism for Regulating Pulmonary Inflammation and Fibrosis." Cell 96, no. 3 (1999): 319-28.

- Stockis, J., S. Liénart, D. Colau, A. Collignon, S. L. Nishimura, D. Sheppard, P. G. Coulie, and S. Lucas. "Blocking Immunosuppression by Human Tregs in Vivo with Antibodies Targeting Integrin Avβ8." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, no. 47 (2017): E10161-e68.

- Guo, W., H. Liu, Y. Yan, D. Wu, H. Yao, K. Lin, and X. Li. "Targeting the Tgf-Β Signaling Pathway: An. Updated Patent Review (2021-Present)." Expert Opin Ther Pat 34, no.

- Dickson, M. C., J. S. Martin, F. M. Cousins, A. B. Kulkarni, S. Karlsson, and R. J. Akhurst. "Defective Haematopoiesis and Vasculogenesis in Transforming Growth Factor-Beta 1 Knock out Mice." Development 121, no. 6 (1995): 1845-54.

- Danielpour, D. "Advances and Challenges in Targeting Tgf-Β Isoforms for Therapeutic Intervention of Cancer: A Mechanism-Based Perspective." Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 17, no. 4 (2024).

- Lancaster, L., V. Cottin, M. Ramaswamy, W. A. Wuyts, R. G. Jenkins, M. B. Scholand, M. Kreuter, C. Valenzuela, C. J. Ryerson, J. Goldin, G. H. J. Kim, M. Jurek, M. Decaris, A. Clark, S. Turner, C. N. Barnes, H. E. Achneck, G. P. Cosgrove, A. Lefebvre É, and K. R. Flaherty. "Bexotegrast in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: The Integris-Ipf Clinical Trial." Am J Respir Crit Care Med 210, no. 4 (2024): 424-34.

- Duan, Z., X. Lin, L. Wang, Q. Zhen, Y. Jiang, C. Chen, J. Yang, C. H. Lee, Y. Qin, Y. Li, B. Zhao, J. Wang, and Z. Zhang. "Specificity of Tgf-Β1 Signal Designated by Lrrc33 and Integrin A(V)Β(8)." Nat Commun 13, no. 1 (2022): 4988.

- Liénart, S., R. Merceron, C. Vanderaa, F. Lambert, D. Colau, J. Stockis, B. van der Woning, H. De Haard, M. Saunders, P. G. Coulie, S. N. Savvides, and S. Lucas. "Structural Basis of Latent Tgf-Β1 Presentation and Activation by Garp on Human Regulatory T Cells." Science 362, no. 6417 (2018): 952-56.

- Lack, J., J. M. O'Leary, V. Knott, X. Yuan, D. B. Rifkin, P. A. Handford, and A. K. Downing. "Solution Structure of the Third Tb Domain from Ltbp1 Provides Insight into Assembly of the Large Latent Complex That Sequesters Latent Tgf-Beta." J Mol Biol 334, no. 2 (2003): 281-91.

- Jackson, J. W., C. Streich Frederick, Jr., A. Pal, G. Coricor, C. Boston, C. T. Brueckner, K. Canonico, C. Chapron, S. Cote, K. B. Dagbay, F. T. Danehy, Jr., M. Kavosi, S. Kumar, S. Lin, C. Littlefield, K. Looby, R. Manohar, C. J. Martin, M. Wood, A. Zawadzka, S. Wawersik, S. B. Nicholls, A. Datta, A. Buckler, T. Schürpf, G. J. Carven, M. Qatanani, and A. I. Fogel. "An Antibody That Inhibits Tgf-Β1 Release from Latent Extracellular Matrix Complexes Attenuates the Progression of Renal Fibrosis." Sci Signal 17, no. 844 (2024): eadn6052.

- Sun, T., Z. Huang, W. C. Liang, J. Yin, W. Y. Lin, J. Wu, J. M. Vernes, J. Lutman, P. Caplazi, S. Jeet, T. Wong, M. Wong, D. J. DePianto, K. B. Morshead, K. H. Sun, Z. Modrusan, J. A. Vander Heiden, A. R. Abbas, H. Zhang, M. Xu, E. N. N'Diaye, M. Roose-Girma, P. J. Wolters, R. Yadav, S. Sukumaran, N. Ghilardi, R. Corpuz, C. Emson, Y. G. Meng, T. R. Ramalingam, P. Lupardus, H. D. Brightbill, D. Seshasayee, Y. Wu, and J. R. Arron. "Tgfβ2 and Tgfβ3 Isoforms Drive Fibrotic Disease Pathogenesis." Sci Transl Med 13, no. 605 (2021).

- Sun, T., J. A. Vander Heiden, X. Gao, J. Yin, S. Uttarwar, W. C. Liang, G. Jia, R. Yadav, Z. Huang, M. Mitra, W. Halpern, H. S. Bender, H. D. Brightbill, Y. Wu, P. Lupardus, T. Ramalingam, and J. R. Arron. "Isoform-Selective Tgf-Β3 Inhibition for Systemic Sclerosis." Med 5, no. 2 (2024): 132-47.e7.

- Spagnolo, P. , and T. M. Maher. "The Future of Clinical Trials in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis." Curr Opin Pulm Med 30, no. 5 (2024): 494-99.

- Richeldi, L., E. R. Fernández Pérez, U. Costabel, C. Albera, D. J. Lederer, K. R. Flaherty, N. Ettinger, R. Perez, M. B. Scholand, J. Goldin, K. H. Peony Yu, T. Neff, S. Porter, M. Zhong, E. Gorina, E. Kouchakji, and G. Raghu. "Pamrevlumab, an Anti-Connective Tissue Growth Factor Therapy, for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (Praise): A Phase 2, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial." Lancet Respir Med 8, no. 1 (2020): 25-33.

- Levy, M. T., G. W. McCaughan, C. A. Abbott, J. E. Park, A. M. Cunningham, E. Müller, W. J. Rettig, and M. D. Gorrell. "Fibroblast Activation Protein: A Cell Surface Dipeptidyl Peptidase and Gelatinase Expressed by Stellate Cells at the Tissue Remodelling Interface in Human Cirrhosis." Hepatology 29, no. 6 (1999): 1768-78.

- Levy, M. T., G. W. McCaughan, G. Marinos, and M. D. Gorrell. "Intrahepatic Expression of the Hepatic Stellate Cell Marker Fibroblast Activation Protein Correlates with the Degree of Fibrosis in Hepatitis C Virus Infection." Liver 22, no. 2 (2002): 93-101.

- Yang, A. T., Y. O. Kim, X. Z. Yan, H. Abe, M. Aslam, K. S. Park, X. Y. Zhao, J. D. Jia, T. Klein, H. You, and D. Schuppan. "Fibroblast Activation Protein Activates Macrophages and Promotes Parenchymal Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis." Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 15, no. 4 (2023): 841-67.

- Williams, K. H., A. J. Viera de Ribeiro, E. Prakoso, A. S. Veillard, N. A. Shackel, Y. Bu, B. Brooks, E. Cavanagh, J. Raleigh, S. V. McLennan, G. W. McCaughan, W. W. Bachovchin, F. M. Keane, A. Zekry, S. M. Twigg, and M. D. Gorrell. "Lower Serum Fibroblast Activation Protein Shows Promise in the Exclusion of Clinically Significant Liver Fibrosis Due to Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Diabetes and Obesity." Diabetes Res Clin Pract 108, no. 3 (2015): 466-72.

- Teixeira-Clerc, F., B. Julien, P. Grenard, J. Tran Van Nhieu, V. Deveaux, L. Li, V. Serriere-Lanneau, C. Ledent, A. Mallat, and S. Lotersztajn. "Cb1 Cannabinoid Receptor Antagonism: A New Strategy for the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis." Nat Med 12, no. 6 (2006): 671-6.

- Mallat, A., F. Teixeira-Clerc, and S. Lotersztajn. "Cannabinoid Signaling and Liver Therapeutics." J Hepatol 59, no. 4 (2013): 891-6.

- Khimji, A. K. , and D. C. Rockey. "Endothelin and Hepatic Wound Healing." Pharmacol Res 63, no. 6 (2011): 512-8.

- He, C., X. Miao, J. Li, and H. Qi. "Angiotensin Ii Induces Endothelin-1 Expression in Human Hepatic Stellate Cells." Dig Dis Sci 58, no. 9 (2013): 2542-9.

- Lee, Y. A., M. C. Wallace, and S. L. Friedman. "Pathobiology of Liver Fibrosis: A Translational Success Story." Gut 64, no. 5 (2015): 830-41.

- Staels, B., A. Rubenstrunk, B. Noel, G. Rigou, P. Delataille, L. J. Millatt, M. Baron, A. Lucas, A. Tailleux, D. W. Hum, V. Ratziu, B. Cariou, and R. Hanf. "Hepatoprotective Effects of the Dual Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha/Delta Agonist, Gft505, in Rodent Models of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease/Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis." Hepatology 58, no. 6 (2013): 1941-52.

- Fernández-Álvarez, S., V. Gutiérrez-de Juan, I. Zubiete-Franco, L. Barbier-Torres, A. Lahoz, A. Parés, Z. Luka, C. Wagner, S. C. Lu, J. M. Mato, M. L. Martínez-Chantar, and N. Beraza. "Trail-Producing Nk Cells Contribute to Liver Injury and Related Fibrogenesis in the Context of Gnmt Deficiency." Lab Invest 95, no. 2 (2015): 223-36.

- Ahsan, M. K. , and W. Z. Mehal. "Activation of Adenosine Receptor A2a Increases Hsc Proliferation and Inhibits Death and Senescence by down-Regulation of P53 and Rb." Front Pharmacol 5 (2014): 69.

- Yashaswini, C. N., T. Qin, D. Bhattacharya, C. Amor, S. Lowe, A. Lujambio, S. Wang, and S. L. Friedman. "Phenotypes and Ontogeny of Senescent Hepatic Stellate Cells in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis." J Hepatol 81, no. 2 (2024): 207-17.

- Huang, X., H. Cai, R. Ammar, Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, K. Ravi, J. Thompson, and G. Jarai. "Molecular Characterization of a Precision-Cut Rat Liver Slice Model for the Evaluation of Antifibrotic Compounds." Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 316, no. 1 (2019): G15-g24.

- Yamagishi, R., F. Kamachi, M. Nakamura, S. Yamazaki, T. Kamiya, M. Takasugi, Y. Cheng, Y. Nonaka, Y. Yukawa-Muto, L. T. T. Thuy, Y. Harada, T. Arai, T. M. Loo, S. Yoshimoto, T. Ando, M. Nakajima, H. Taguchi, T. Ishikawa, H. Akiba, S. Miyake, M. Kubo, Y. Iwakura, S. Fukuda, W. Y. Chen, N. Kawada, A. Rudensky, S. Nakae, E. Hara, and N. Ohtani. "Gasdermin D-Mediated Release of Il-33 from Senescent Hepatic Stellate Cells Promotes Obesity-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma." Sci Immunol 7, no. 72 (2022): eabl7209.

- Hu, J. J., X. Liu, S. Xia, Z. Zhang, Y. Zhang, J. Zhao, J. Ruan, X. Luo, X. Lou, Y. Bai, J. Wang, L. R. Hollingsworth, V. G. Magupalli, L. Zhao, H. R. Luo, J. Kim, J. Lieberman, and H. Wu. "Fda-Approved Disulfiram Inhibits Pyroptosis by Blocking Gasdermin D Pore Formation." Nat Immunol 21, no. 7 (2020): 736-45.

- Robert, S., T. Gicquel, T. Victoni, S. Valença, E. Barreto, B. Bailly-Maître, E. Boichot, and V. Lagente. "Involvement of Matrix Metalloproteinases (Mmps) and Inflammasome Pathway in Molecular Mechanisms of Fibrosis." Biosci Rep 36, no. 4 (2016).

- Urtasun, R., A. Lopategi, J. George, T. M. Leung, Y. Lu, X. Wang, X. Ge, M. I. Fiel, and N. Nieto. "Osteopontin, an Oxidant Stress Sensitive Cytokine, up-Regulates Collagen-I Via Integrin A(V)Β(3) Engagement and Pi3k/Pakt/Nfκb Signaling." Hepatology 55, no. 2 (2012): 594-608.

- Chen, W., A. Yang, J. Jia, Y. V. Popov, D. Schuppan, and H. You. "Lysyl Oxidase (Lox) Family Members: Rationale and Their Potential as Therapeutic Targets for Liver Fibrosis." Hepatology 72, no. 2 (2020): 729-41.

- Meissner, E. G., M. McLaughlin, L. Matthews, A. M. Gharib, B. J. Wood, E. Levy, R. Sinkus, K. Virtaneva, D. Sturdevant, C. Martens, S. F. Porcella, Z. D. Goodman, B. Kanwar, R. P. Myers, M. Subramanian, C. Hadigan, H. Masur, D. E. Kleiner, T. Heller, S. Kottilil, J. A. Kovacs, and C. G. Morse. "Simtuzumab Treatment of Advanced Liver Fibrosis in Hiv and Hcv-Infected Adults: Results of a 6-Month Open-Label Safety Trial." Liver Int 36, no. 12 (2016): 1783-92.

- Muir, A. J., C. Levy, H. L. A. Janssen, A. J. Montano-Loza, M. L. Shiffman, S. Caldwell, V. Luketic, D. Ding, C. Jia, B. J. McColgan, J. G. McHutchison, G. Mani Subramanian, R. P. Myers, M. Manns, R. Chapman, N. H. Afdhal, Z. Goodman, B. Eksteen, and C. L. Bowlus. "Simtuzumab for Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: Phase 2 Study Results with Insights on the Natural History of the Disease." Hepatology 69, no. 2 (2019): 684-98.

- Harrison, S. A., M. F. Abdelmalek, S. Caldwell, M. L. Shiffman, A. M. Diehl, R. Ghalib, E. J. Lawitz, D. C. Rockey, R. A. Schall, C. Jia, B. J. McColgan, J. G. McHutchison, G. M. Subramanian, R. P. Myers, Z. Younossi, V. Ratziu, A. J. Muir, N. H. Afdhal, Z. Goodman, J. Bosch, and A. J. Sanyal. "Simtuzumab Is Ineffective for Patients with Bridging Fibrosis or Compensated Cirrhosis Caused by Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis." Gastroenterology 155, no. 4 (2018): 1140-53.

- Bian, E. B., B. Zhao, C. Huang, H. Wang, X. M. Meng, B. M. Wu, T. T. Ma, L. Zhang, X. W. Lv, and J. Li. "New Advances of DNA Methylation in Liver Fibrosis, with Special Emphasis on the Crosstalk between Micrornas and DNA Methylation Machinery." Cell Signal 25, no. 9 (2013): 1837-44.

- Kuang, Y., A. El-Khoueiry, P. Taverna, M. Ljungman, and N. Neamati. "Guadecitabine (Sgi-110) Priming Sensitizes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Oxaliplatin." Mol Oncol 9, no. 9 (2015): 1799-814.

- Hardy, T. , and D. A. Mann. "Epigenetics in Liver Disease: From Biology to Therapeutics." Gut 65, no. 11 (2016): 1895-905.

- Hyun, J., J. Park, S. Wang, J. Kim, H. H. Lee, Y. S. Seo, and Y. Jung. "Microrna Expression Profiling in Ccl₄-Induced Liver Fibrosis of Mus Musculus." Int J Mol Sci 17, no. 6 (2016).

- Roderburg, C., G. W. Urban, K. Bettermann, M. Vucur, H. Zimmermann, S. Schmidt, J. Janssen, C. Koppe, P. Knolle, M. Castoldi, F. Tacke, C. Trautwein, and T. Luedde. "Micro-Rna Profiling Reveals a Role for Mir-29 in Human and Murine Liver Fibrosis." Hepatology 53, no. 1 (2011): 209-18.

- Tu, X., X. Zheng, H. Li, Z. Cao, H. Chang, S. Luan, J. Zhu, J. Chen, Y. Zang, and J. Zhang. "Microrna-30 Protects against Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis by Attenuating Transforming Growth Factor Beta Signaling in Hepatic Stellate Cells." Toxicol Sci 146, no. 1 (2015): 157-69.

- Høydahl, L. S., G. Berntzen, and GÅ Løset. "Engineering t-Cell Receptor-Like Antibodies for Biologics and Cell Therapy." Curr Opin Biotechnol 90 (2024): 103224.

- Amor, C., J. Feucht, J. Leibold, Y. J. Ho, C. Zhu, D. Alonso-Curbelo, J. Mansilla-Soto, J. A. Boyer, X. Li, T. Giavridis, A. Kulick, S. Houlihan, E. Peerschke, S. L. Friedman, V. Ponomarev, A. Piersigilli, M. Sadelain, and S. W. Lowe. "Senolytic Car T Cells Reverse Senescence-Associated Pathologies." Nature 583, no. 7814 (2020): 127-32.

- Aghajanian, H., T. Kimura, J. G. Rurik, A. S. Hancock, M. S. Leibowitz, L. Li, J. Scholler, J. Monslow, A. Lo, W. Han, T. Wang, K. Bedi, M. P. Morley, R. A. Linares Saldana, N. A. Bolar, K. McDaid, C. A. Assenmacher, C. L. Smith, D. Wirth, C. H. June, K. B. Margulies, R. Jain, E. Puré, S. M. Albelda, and J. A. Epstein. "Targeting Cardiac Fibrosis with Engineered T Cells." Nature 573, no. 7774 (2019): 430-33.

- Amrute, J. M., X. Luo, V. Penna, S. Yang, T. Yamawaki, S. Hayat, A. Bredemeyer, I. H. Jung, F. F. Kadyrov, G. S. Heo, R. Venkatesan, S. Y. Shi, A. Parvathaneni, A. L. Koenig, C. Kuppe, C. Baker, H. Luehmann, C. Jones, B. Kopecky, X. Zeng, T. Bleckwehl, P. Ma, P. Lee, Y. Terada, A. Fu, M. Furtado, D. Kreisel, A. Kovacs, N. O. Stitziel, S. Jackson, C. M. Li, Y. Liu, N. A. Rosenthal, R. Kramann, B. Ason, and K. J. Lavine. "Targeting Immune-Fibroblast Cell Communication in Heart Failure." Nature 635, no. 8038 (2024): 423-33.

- Friedman, S. L. "Fighting Cardiac Fibrosis with Car T Cells." N Engl J Med 386, no. 16 (2022): 1576-78.

- Rurik, J. G., I. Tombácz, A. Yadegari, P. O. Méndez Fernández, S. V. Shewale, L. Li, T. Kimura, O. Y. Soliman, T. E. Papp, Y. K. Tam, B. L. Mui, S. M. Albelda, E. Puré, C. H. June, H. Aghajanian, D. Weissman, H. Parhiz, and J. A. Epstein. "Car T Cells Produced in Vivo to Treat Cardiac Injury." Science 375, no. 6576 (2022): 91-96.

- Basalova, N., N. Alexandrushkina, O. Grigorieva, M. Kulebyakina, and A. Efimenko. "Fibroblast Activation Protein Alpha (Fapα) in Fibrosis: Beyond a Perspective Marker for Activated Stromal Cells?" Biomolecules 13, no. 12 (2023).

- Zhao, X., J. Lin, M. Liu, D. Jiang, Y. Zhang, X. Li, B. Shi, J. Jiang, C. Ma, H. Shao, Q. Xu, H. Ping, J. Li, and Y. Gao. "Targeting Fap-Positive Chondrocytes in Osteoarthritis: A Novel Lipid Nanoparticle Sirna Approach to Mitigate Cartilage Degeneration." J Nanobiotechnology 22, no. 1 (2024): 659.

- Eriksson, O. , and I. Velikyan. "Radiotracers for Imaging of Fibrosis: Advances during the Last Two Decades and Future Directions." Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 16, no. 11 (2023).

- Trinh, V. Q., T. F. Lee, S. Lemoinne, K. C. Ray, M. D. Ybanez, T. Tsuchida, J. K. Carter, J. Agudo, B. D. Brown, K. M. Akat, S. L. Friedman, and Y. A. Lee. "Hepatic Stellate Cells Maintain Liver Homeostasis through Paracrine Neurotrophin-3 Signaling That Induces Hepatocyte Proliferation." Sci Signal 16, no. 787 (2023): eadf6696.

- Li, M., B. Wu, L. Li, C. Lv, and Y. Tian. "Reprogramming of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Combined with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Cancers." Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1878, no. 5 (2023): 188945.

- Krenkel, O., J. Hundertmark, T. P. Ritz, R. Weiskirchen, and F. Tacke. "Single Cell Rna Sequencing Identifies Subsets of Hepatic Stellate Cells and Myofibroblasts in Liver Fibrosis." Cells 8, no. 5 (2019).

- Khan, M. A., J. Fischer, L. Harrer, F. Schwiering, D. Groneberg, and A. Friebe. "Hepatic Stellate Cells in Zone 1 Engage in Capillarization Rather Than Myofibroblast Formation in Murine Liver Fibrosis." Sci Rep 14, no. 1 (2024): 18840.

- Yamagata, K., S. Takasuga, M. Tatematsu, A. Fuchimukai, T. Yamada, M. Mizuno, M. Morii, and T. Ebihara. "Foxd1 Expression Identifies a Distinct Subset of Hepatic Stellate Cells Involved in Liver Fibrosis." Biochem Biophys Res Commun 734 (2024): 150632.

- Rosenthal, S. B., X. Liu, S. Ganguly, D. Dhar, M. P. Pasillas, E. Ricciardelli, R. Z. Li, T. D. Troutman, T. Kisseleva, C. K. Glass, and D. A. Brenner. "Heterogeneity of Hscs in a Mouse Model of Nash." Hepatology 74, no. 2 (2021): 667-85.

- Cogliati, B., C. N. Yashaswini, S. Wang, D. Sia, and S. L. Friedman. "Friend or Foe? The Elusive Role of Hepatic Stellate Cells in Liver Cancer." Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 20, no. 10 (2023): 647-61.

- Wang, S., K. Li, E. Pickholz, R. Dobie, K. P. Matchett, N. C. Henderson, C. Carrico, I. Driver, M. Borch Jensen, L. Chen, M. Petitjean, D. Bhattacharya, M. I. Fiel, X. Liu, T. Kisseleva, U. Alon, M. Adler, R. Medzhitov, and S. L. Friedman. "An Autocrine Signaling Circuit in Hepatic Stellate Cells Underlies Advanced Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis." Sci Transl Med 15, no. 677 (2023): eadd3949.

- Filliol, A., Y. Saito, A. Nair, D. H. Dapito, L. X. Yu, A. Ravichandra, S. Bhattacharjee, S. Affo, N. Fujiwara, H. Su, Q. Sun, T. M. Savage, J. R. Wilson-Kanamori, J. M. Caviglia, L. Chin, D. Chen, X. Wang, S. Caruso, J. K. Kang, A. D. Amin, S. Wallace, R. Dobie, D. Yin, O. M. Rodriguez-Fiallos, C. Yin, A. Mehal, B. Izar, R. A. Friedman, R. G. Wells, U. B. Pajvani, Y. Hoshida, H. E. Remotti, N. Arpaia, J. Zucman-Rossi, M. Karin, N. C. Henderson, I. Tabas, and R. F. Schwabe. "Opposing Roles of Hepatic Stellate Cell Subpopulations in Hepatocarcinogenesis." Nature 610, no. 7931 (2022): 356-65.

- Merens, V., E. Knetemann, E. Gürbüz, V. De Smet, N. Messaoudi, H. Reynaert, S. Verhulst, and L. A. van Grunsven. "Hepatic Stellate Cell Single Cell Atlas Reveals a Highly Similar Activation Process across Liver Disease Aetiologies." JHEP Rep 7, no. 1 (2025): 101223.

- Fallowfield, J. A. "Therapeutic Targets in Liver Fibrosis." Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300, no. 5 (2011): G709-15.

- Friedman, S. L., D. Sheppard, J. S. Duffield, and S. Violette. "Therapy for Fibrotic Diseases: Nearing the Starting Line." Sci Transl Med 5, no. 167 (2013): 167sr1.

- Ramachandran, P., K. P. Matchett, R. Dobie, J. R. Wilson-Kanamori, and N. C. Henderson. "Single-Cell Technologies in Hepatology: New Insights into Liver Biology and Disease Pathogenesis." Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 17, no. 8 (2020): 457-72.

- Roehlen, N., E. Crouchet, and T. F. Baumert. "Liver Fibrosis: Mechanistic Concepts and Therapeutic Perspectives." Cells 9, no. 4 (2020).

- Dobie, R., J. R. Wilson-Kanamori, B. E. P. Henderson, J. R. Smith, K. P. Matchett, J. R. Portman, K. Wallenborg, S. Picelli, A. Zagorska, S. V. Pendem, T. E. Hudson, M. M. Wu, G. R. Budas, D. G. Breckenridge, E. M. Harrison, D. J. Mole, S. J. Wigmore, P. Ramachandran, C. P. Ponting, S. A. Teichmann, J. C. Marioni, and N. C. Henderson. "Single-Cell Transcriptomics Uncovers Zonation of Function in the Mesenchyme during Liver Fibrosis." Cell Rep 29, no. 7 (2019): 1832-47.e8.

- Su, T., Y. Yang, S. Lai, J. Jeong, Y. Jung, M. McConnell, T. Utsumi, and Y. Iwakiri. "Single-Cell Transcriptomics Reveals Zone-Specific Alterations of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Cirrhosis." Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 11, no. 4 (2021): 1139-61.

- Saviano, A., N. C. Henderson, and T. F. Baumert. "Single-Cell Genomics and Spatial Transcriptomics: Discovery of Novel Cell States and Cellular Interactions in Liver Physiology and Disease biology." J Hepatol 73, no. 5 (2020): 1219-30.

- Ramachandran, P., R. Dobie, J. R. Wilson-Kanamori, E. F. Dora, B. E. P. Henderson, N. T. Luu, J. R. Portman, K. P. Matchett, M. Brice, J. A. Marwick, R. S. Taylor, M. Efremova, R. Vento-Tormo, N. O. Carragher, T. J. Kendall, J. A. Fallowfield, E. M. Harrison, D. J. Mole, S. J. Wigmore, P. N. Newsome, C. J. Weston, J. P. Iredale, F. Tacke, J. W. Pollard, C. P. Ponting, J. C. Marioni, S. A. Teichmann, and N. C. Henderson. "Resolving the Fibrotic Niche of Human Liver Cirrhosis at Single-Cell Level." Nature 575, no. 7783 (2019): 512-18.

- Chen, Z., A. Jain, H. Liu, Z. Zhao, and K. Cheng. "Targeted Drug Delivery to Hepatic Stellate Cells for the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis." J Pharmacol Exp Ther 370, no. 3 (2019): 695-702.

- Bansal, R. , and K. Poelstra. "Hepatic Stellate Cell Targeting Using Peptide-Modified Biologicals." Methods Mol Biol 2669 (2023): 269-84.

- Qian, T., N. Fujiwara, B. Koneru, A. Ono, N. Kubota, A. K. Jajoriya, M. G. Tung, E. Crouchet, W. M. Song, C. A. Marquez, G. Panda, A. Hoshida, I. Raman, Q. Z. Li, C. Lewis, A. Yopp, N. E. Rich, A. G. Singal, S. Nakagawa, N. Goossens, T. Higashi, A. P. Koh, C. B. Bian, H. Hoshida, P. Tabrizian, G. Gunasekaran, S. Florman, M. E. Schwarz, S. P. Hiotis, T. Nakahara, H. Aikata, E. Murakami, T. Beppu, H. Baba, Warren Rew, S. Bhatia, M. Kobayashi, H. Kumada, A. J. Fobar, N. D. Parikh, J. A. Marrero, S. H. Rwema, V. Nair, M. Patel, S. Kim-Schulze, K. Corey, J. G. O'Leary, G. B. Klintmalm, D. L. Thomas, M. Dibas, G. Rodriguez, B. Zhang, S. L. Friedman, T. F. Baumert, B. C. Fuchs, K. Chayama, S. Zhu, R. T. Chung, and Y. Hoshida. "Molecular Signature Predictive of Long-Term Liver Fibrosis Progression to Inform Antifibrotic Drug Development." Gastroenterology 162, no. 4 (2022): 1210-25.

- Guo, J., W. Liu, Z. Zeng, J. Lin, X. Zhang, and L. Chen. "Tgfb3 and Mmp13 Regulated the Initiation of Liver Fibrosis Progression as Dynamic Network Biomarkers." J Cell Mol Med 25, no. 2 (2021): 867-79.

- Schnittert, J., R. Bansal, G. Storm, and J. Prakash. "Integrins in Wound Healing, Fibrosis and Tumor Stroma: High Potential Targets for Therapeutics and Drug Delivery." Adv Drug Deliv Rev 129 (2018): 37-53.

- Kurniawan, D. W., R. Booijink, L. Pater, I. Wols, A. Vrynas, G. Storm, J. Prakash, and R. Bansal. "Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Conjugated Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Fgf2-Spions) Ameliorate Hepatic Stellate Cells Activation in Vitro and Acute Liver Injury in Vivo." J Control Release 328 (2020): 640-52.

- Huang, L., J. Xie, Q. Bi, Z. Li, S. Liu, Q. Shen, and C. Li. "Highly Selective Targeting of Hepatic Stellate Cells for Liver Fibrosis Treatment Using a D-Enantiomeric Peptide Ligand of Fn14 Identified by Mirror-Image Mrna Display." Mol Pharm 14, no. 5 (2017): 1742-53.

- Moreno, M., T. Gonzalo, R. J. Kok, P. Sancho-Bru, M. van Beuge, J. Swart, J. Prakash, K. Temming, C. Fondevila, L. Beljaars, M. Lacombe, P. van der Hoeven, V. Arroyo, K. Poelstra, D. A. Brenner, P. Ginès, and R. Bataller. "Reduction of Advanced Liver Fibrosis by Short-Term Targeted Delivery of an Angiotensin Receptor Blocker to Hepatic Stellate Cells in Rats." Hepatology 51, no. 3 (2010): 942-52.

- Lee, J., J. Byun, G. Shim, and Y. K. Oh. "Fibroblast Activation Protein Activated Antifibrotic Peptide Delivery Attenuates Fibrosis in Mouse Models of Liver Fibrosis." Nat Commun 13, no. 1 (2022): 1516.

- Klein, S., M. M. Van Beuge, M. Granzow, L. Beljaars, R. Schierwagen, S. Kilic, I. Heidari, S. Huss, T. Sauerbruch, K. Poelstra, and J. Trebicka. "Hsc-Specific Inhibition of Rho-Kinase Reduces Portal Pressure in Cirrhotic Rats without Major Systemic Effects." J Hepatol 57, no. 6 (2012): 1220-7.

- Bansal, R., J. Prakash, E. Post, L. Beljaars, D. Schuppan, and K. Poelstra. "Novel Engineered Targeted Interferon-Gamma Blocks Hepatic Fibrogenesis in Mice." Hepatology 54, no. 2 (2011): 586-96.

- Sato, Y., K. Murase, J. Kato, M. Kobune, T. Sato, Y. Kawano, R. Takimoto, K. Takada, K. Miyanishi, T. Matsunaga, T. Takayama, and Y. Niitsu. "Resolution of Liver Cirrhosis Using Vitamin a-Coupled Liposomes to Deliver Sirna against a Collagen-Specific Chaperone." Nat Biotechnol 26, no. 4 (2008): 431-42.

- Salvati, A. , and K. Poelstra. "Drug Targeting and Nanomedicine: Lessons Learned from Liver Targeting and Opportunities for Drug Innovation." Pharmaceutics 14, no. 1 (2022).

- Bansal, R., J. Prakash, M. De Ruiter, and K. Poelstra. "Targeted Recombinant Fusion Proteins of Ifnγ and Mimetic Ifnγ with Pdgfβr Bicyclic Peptide Inhibits Liver Fibrogenesis in Vivo." PLoS One 9, no. 2 (2014): e89878.

- Yazdani, S., R. Bansal, and J. Prakash. "Drug Targeting to Myofibroblasts: Implications for Fibrosis and Cancer." Adv Drug Deliv Rev 121 (2017): 101-16.

- Pringle, T. A., E. Ramon-Gil, J. Leslie, F. Oakley, M. C. Wright, J. C. Knight, and S. Luli. "Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of a (89)Zr-Labelled Human Single Chain Antibody for Non-Invasive Detection of Hepatic Myofibroblasts in Acute Liver Injury." Sci Rep 14, no. 1 (2024): 633.

- Lin, C. Y., U. F. Mamani, Y. Guo, Y. Liu, and K. Cheng. "Peptide-Based Sirna Nanocomplexes Targeting Hepatic Stellate Cells." Biomolecules 13, no. 3 (2023).

- Jain, A., A. Barve, Z. Zhao, J. P. Fetse, H. Liu, Y. Li, and K. Cheng. "Targeted Delivery of an Sirna/Pna Hybrid Nanocomplex Reverses Carbon Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Fibrosis." Adv Ther (Weinh) 2, no. 8 (2019).

- Zhao, Z., Y. Li, A. Jain, Z. Chen, H. Liu, W. Jin, and K. Cheng. "Development of a Peptide-Modified Sirna Nanocomplex for Hepatic Stellate Cells." Nanomedicine 14, no. 1 (2018): 51-61.

- Lawitz, E. J., D. E. Shevell, G. S. Tirucherai, S. Du, W. Chen, U. Kavita, A. Coste, F. Poordad, M. Karsdal, M. Nielsen, Z. Goodman, and E. D. Charles. "Bms-986263 in Patients with Advanced Hepatic Fibrosis: 36-Week Results from a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial." Hepatology 75, no. 4 (2022): 912-23.

- Hill, T. A., N. E. Shepherd, F. Diness, and D. P. Fairlie. "Constraining Cyclic Peptides to Mimic Protein Structure Motifs." Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 53, no. 48 (2014): 13020-41.

- Petta, I., S. Lievens, C. Libert, J. Tavernier, and K. De Bosscher. "Modulation of Protein-Protein Interactions for the Development of Novel Therapeutics." Mol Ther 24, no. 4 (2016): 707-18.

- Lee, A. C., J. L. Harris, K. K. Khanna, and J. H. Hong. "A Comprehensive Review on Current Advances in Peptide Drug Development and Design." Int J Mol Sci 20, no. 10 (2019).

- Geppert, T., B. Hoy, S. Wessler, and G. Schneider. "Context-Based Identification of Protein-Protein Interfaces and "Hot-Spot" Residues." Chem Biol 18, no. 3 (2011): 344-53.

- Bhat, A., L. R. Roberts, and J. J. Dwyer. "Lead Discovery and Optimization Strategies for Peptide Macrocycles." Eur J Med Chem 94 (2015): 471-9.

- Villar, E. A., D. Beglov, S. Chennamadhavuni, J. A. Porco, Jr., D. Kozakov, S. Vajda, and A. Whitty. "How Proteins Bind Macrocycles." Nat Chem Biol 10, no. 9 (2014): 723-31.

- Liu, D., D. Xu, M. Liu, W. E. Knabe, C. Yuan, D. Zhou, M. Huang, and S. O. Meroueh. "Small Molecules Engage Hot Spots through Cooperative Binding to Inhibit a Tight Protein-Protein Interaction." Biochemistry 56, no. 12 (2017): 1768-84.

- Wang, L., N. Wang, W. Zhang, X. Cheng, Z. Yan, G. Shao, X. Wang, R. Wang, and C. Fu. "Therapeutic Peptides: Current Applications and Future Directions." Signal Transduct Target Ther 7, no. 1 (2022): 48.

- Mantovani, A., C. D. Byrne, and G. Targher. "Efficacy of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Agonists, Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists, or Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors for Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review." Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 7, no. 4 (2022): 367-78.

- Malm-Erjefält, M., I. Bjørnsdottir, J. Vanggaard, H. Helleberg, U. Larsen, B. Oosterhuis, J. J. van Lier, M. Zdravkovic, and A. K. Olsen. "Metabolism and Excretion of the Once-Daily Human Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Analog Liraglutide in Healthy Male Subjects and Its in Vitro Degradation by Dipeptidyl Peptidase Iv and Neutral Endopeptidase." Drug Metab Dispos 38, no. 11 (2010): 1944-53.

| targeting HSC activation Target | Drug name | Drug category | Population(n) | Highest status (phase) | NCT | Status |

| TGF-β/TGFβR | Hydronidone | Small molecule | Liver fibrosis (248) | III | NCT05115942 | Completed |

| FGF21 | BIO89-100 | Fusion proteins | MASH (101) | II | NCT04048135 | Completed |

| Efruxifermin | Fusion proteins | MASH (110) | II | NCT03976401 | Completed | |

| Pergbelfermin | Fusion proteins | Liver cirrhosis andMASH (155) | II | NCT03486912 | Completed | |

| FGF19 | Aldafermin | Fusion proteins | MASH (171) | II | NCT03912532 | Completed |

| WNT/β-catenin | PRI-724 | Small molecule | Liver cirrhosis (27) | II | NCT03620474 | Completed |

| LOXL2 | PXS-5382A | Small molecule | MASH (18) | I | NCT04183517 | Completed |

| PPARα/γ | Saroglitazar | Small molecule | MASH (20) | II | NCT03639623 | Completed |

| PPARα/δ/γ | Lanifibranor | Small molecule | MASH (1000) | III | NCT04849728 | Recruiting |

| PPARα | Pemafibrate | Small molecule | MASH (118) | II | NCT03350165 | Completed |

| PPARα/δ | ZSP0678 | Small molecule | MASH (104) | I | NCT04137055 | Completed |

| TLR4 | JKB-121 | Small molecule | MASH (65) | II | NCT02442687 | Completed |

| JKB-122 | Small molecule | MASH (300) | II | NCT04255069 | Unknown | |

| GLP-1 receptor | Semaglutide | Small molecule | MASH (1200) | III | NCT04822181 | Active, not recruiting |

| GLP-1/GIP receptor | Trizepatide | Small molecule | MASH (190) | II | NCT04166773 | Completed |

| GLP-1/Glucagon receptor | Cotadutide | Small molecule | MASH (54) | II | NCT05364931 | Completed |

| GLP-1/GIP/Glucagon | HM-15211 | Small molecule | MASH (240) | II | NCT04505436 | Recruiting |

| THRβ | Resmetirom | Small molecule | MASH (1759) | III | NCT03900429 | Active, not recruiting |

| VK2809 | Small molecule | MASH (248) | II | NCT04173065 | Completed | |

| MPC | Azemiglitazone | Small molecule | NASH (1800) | III | NCT03970031 | Unknown |

| Deuterium-stabilized (R)-Piglitazone | Small molecule | MASH (117) | II | NCT04321343 | Completed | |

| PDEs (mainly PED2) | NZSP1601 | Small molecule | MASH (37) | II | NCT04140123 | Completed |

| LOXL2, PDE3/4 | Epeleuton | Small molecule | MAFLD (96) | II | NCT02941549 | Completed |

| AMPK | PXL-770 | Small molecule | MAFLD (211) | II | NCT03763877 | Completed |

| MMP(MMP2,MMP9. VEGF-A) | ALS-L1023 | Small molecule | MASH (60) | II | NCT04342793 | Completed |

| A3AR | Namodenoson | Small molecule | MASH (60) | II | NCT02927314 | Completed |

| FASN | TVB-2640 | Small molecule | MASH and MAFLD (2000) | III | NCT06692283 | Not yet recruiting |

| Biodentical testosterone | LPCN1144 | Small molecule | MASH (56) | II | NCT04134091 | Completed |

| Stem cell | HepaStem | Cell transplant therapies | MASH (23) | II | NCT03963921 | Completed |

| HSP47 | BMS-986263 | siRNA | MASH (124) | II | NCT04267393 | Terminated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).