Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

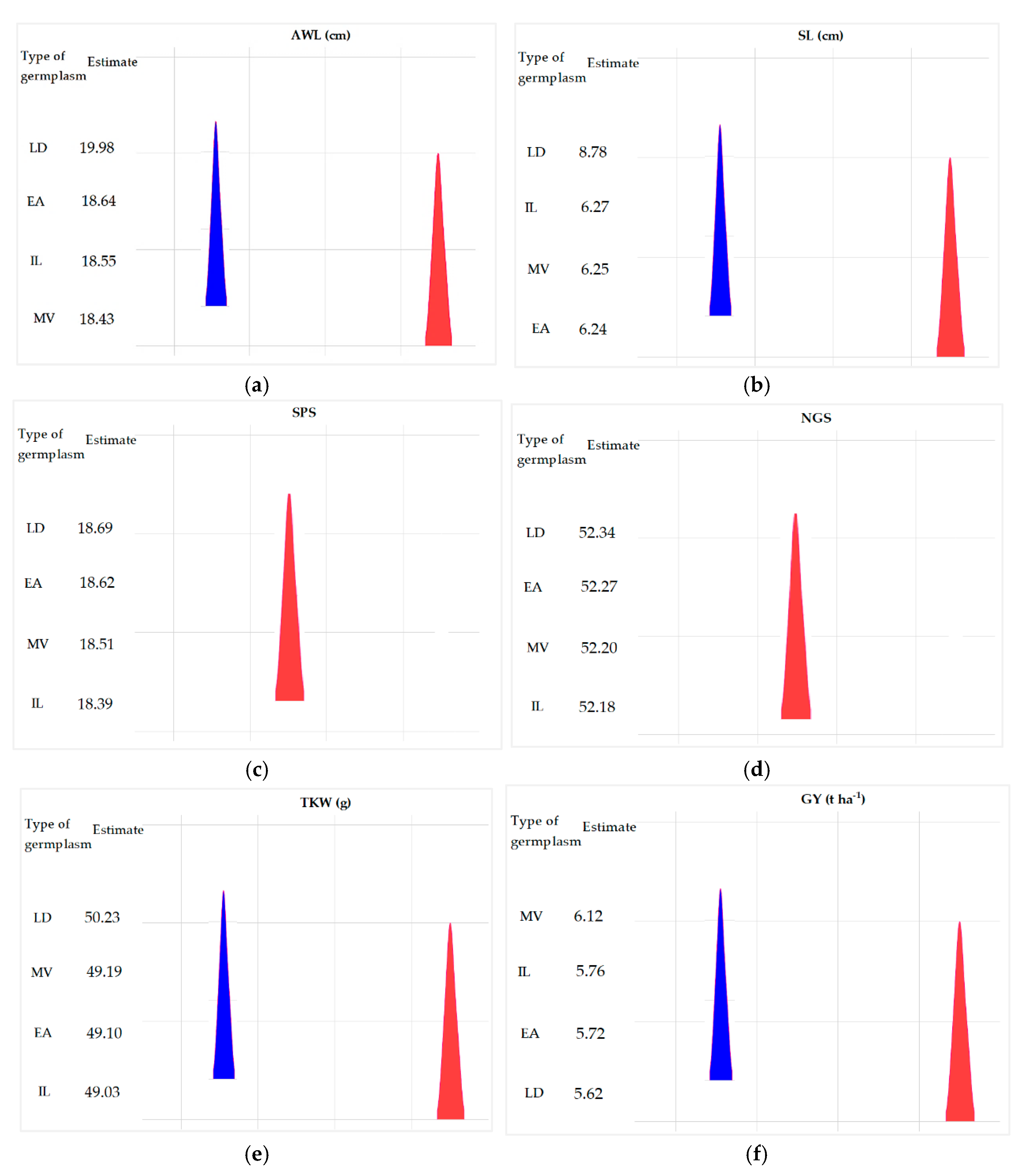

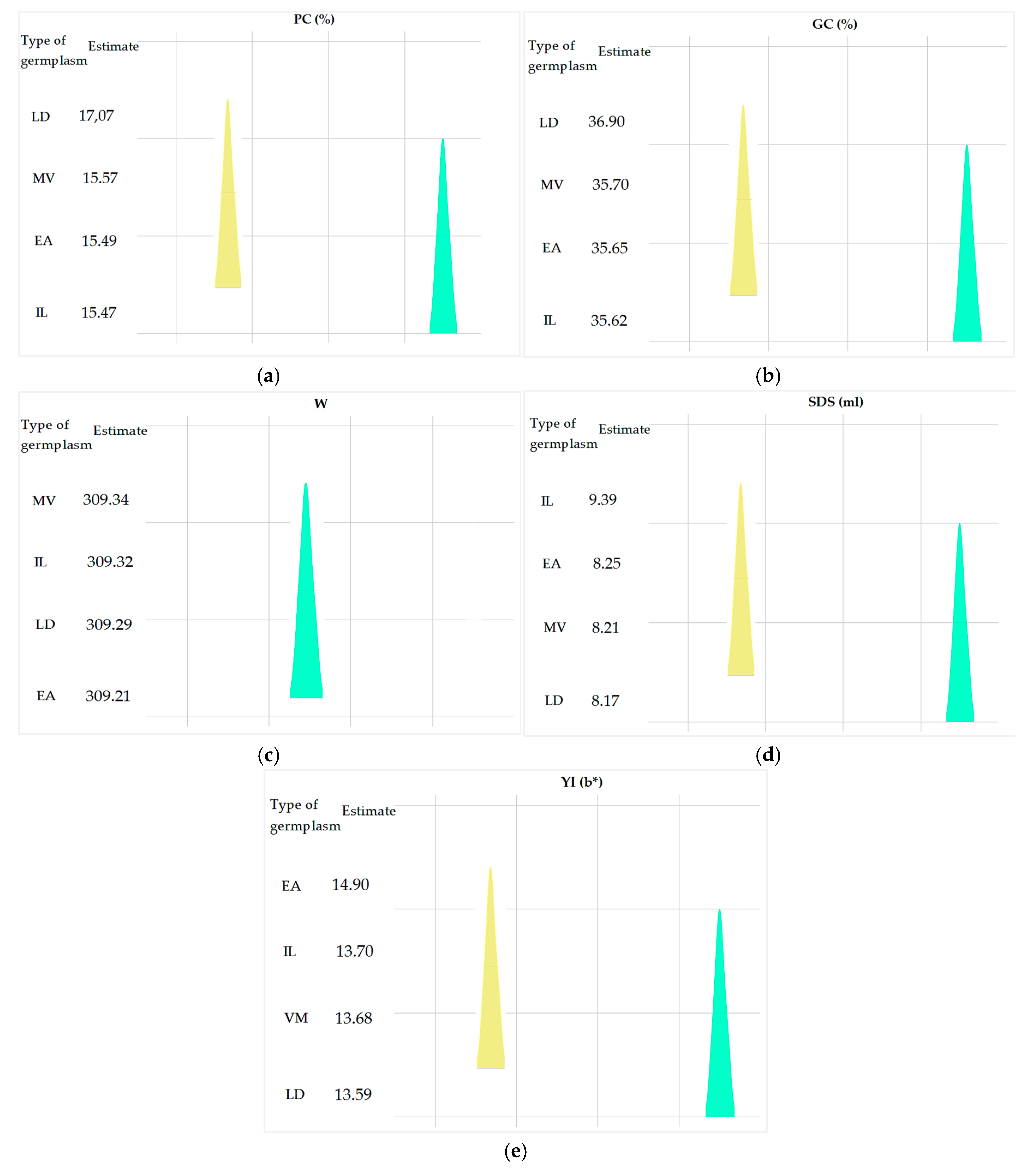

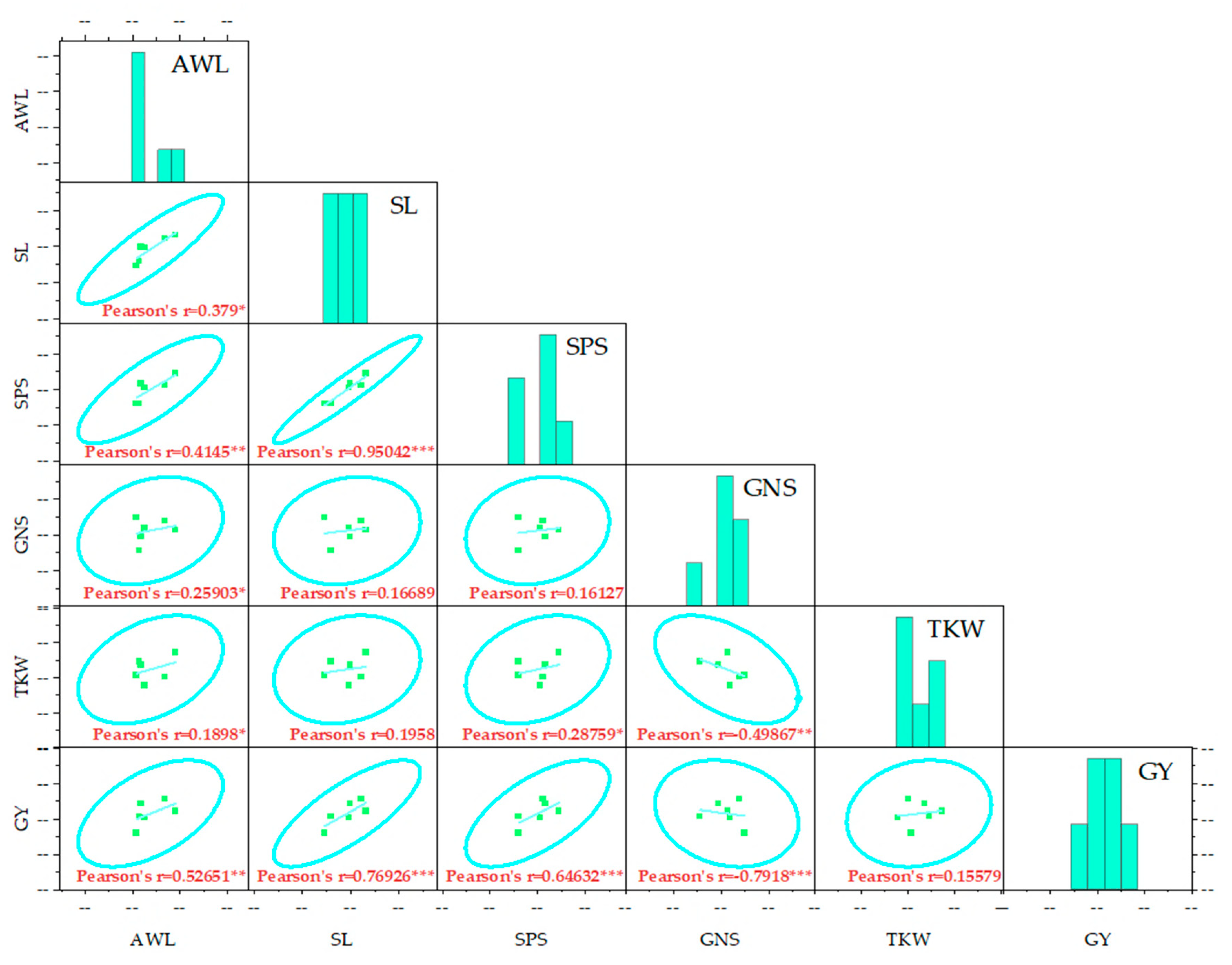

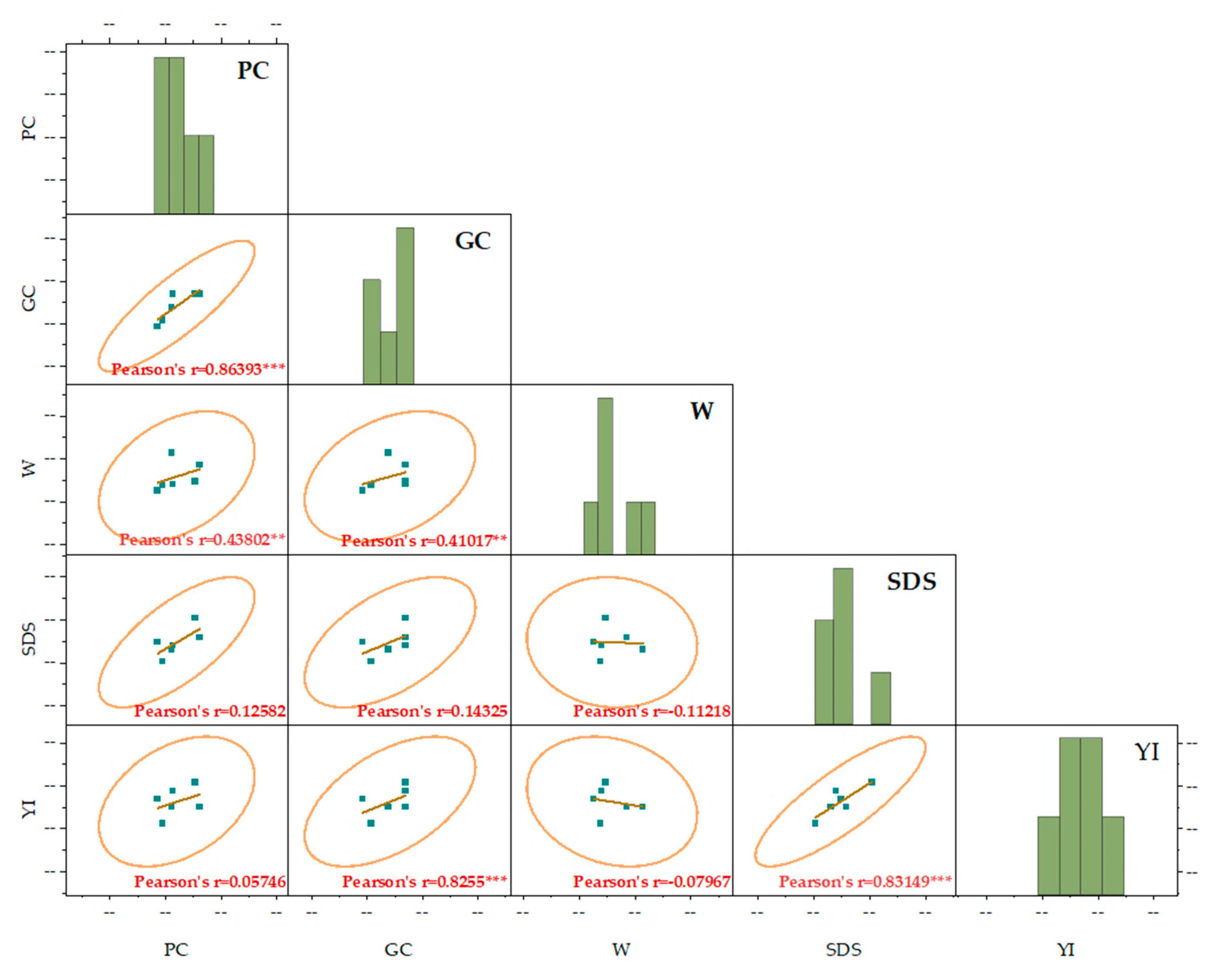

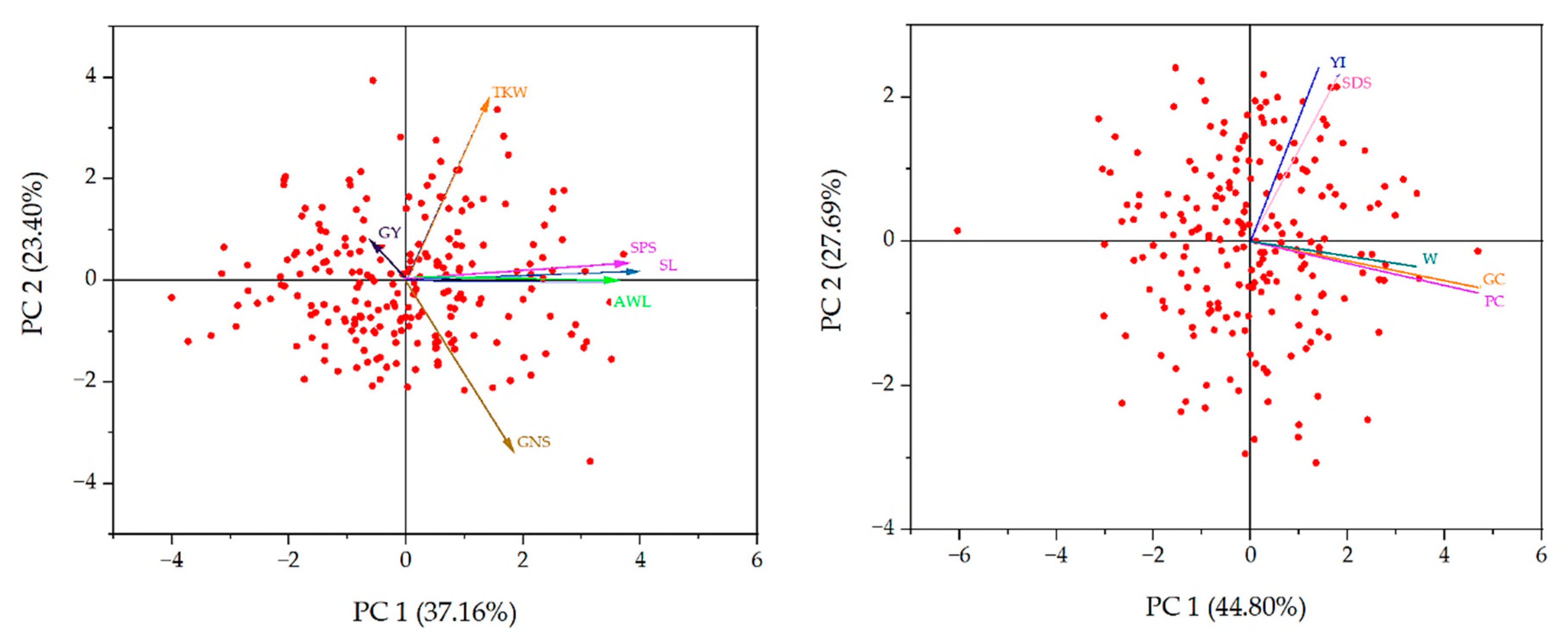

The productivity and resilience of durum wheat have been enhanced through the selection of accessions, optimizing agronomic and quality traits to address environmental challenges. This study investigates the inter-group genetic diversity of 219 durum wheat accessions, including 120 elite lines from a national breeding program, 63 international lines, 27 Moroccan varieties, and 9 landraces. Trials were conducted at the Jemâa Shaïm experimental station (INRA-Morocco) with an "Alpha lattice" design and two replications. Significant correlations were observed between spike length and number of spikelets (r = 0.950; p < 0.001), and between gluten and protein content (r = 0.863; p < 0.001). Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that agro-morphological traits explained 77.12% of variability, while quality traits accounted for 95.54%. Elite lines showed a high yellow pigment index (14.90), important for wheat technological quality. Traditional landraces performed well in spike length (8.78 cm), thousand-grain weight (50.23 g), protein content (17.07%), and gluten content (36.90%). Moroccan varieties achieved a grain yield of 6.12 t/ha. International lines exhibited the highest SDS value (9.39 ml), indicating superior technological quality. These findings emphasize the importance of landraces, Moroccan varieties, and elite accessions for developing high-quality, high-yielding durum wheat varieties adaptable to challenging conditions, contributing significantly to productivity and sustainability.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Analysis of Variance

2.2. ANOVA of Quality Parameters

2.3. Relationships Between the Evaluated Parameters

2.3.1. Correlation Analysis of Various Agro-Morphological Parameters

2.3.2. Correlation Analysis of Various Quality Parameters

2.4. Principal Component Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. Description of the Variability in Agro-Morphological Parameters and Grain Quality Traits

3.2. Relationship Between Agronomic Traits and Yield Components

3.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

4. Materials and Methods

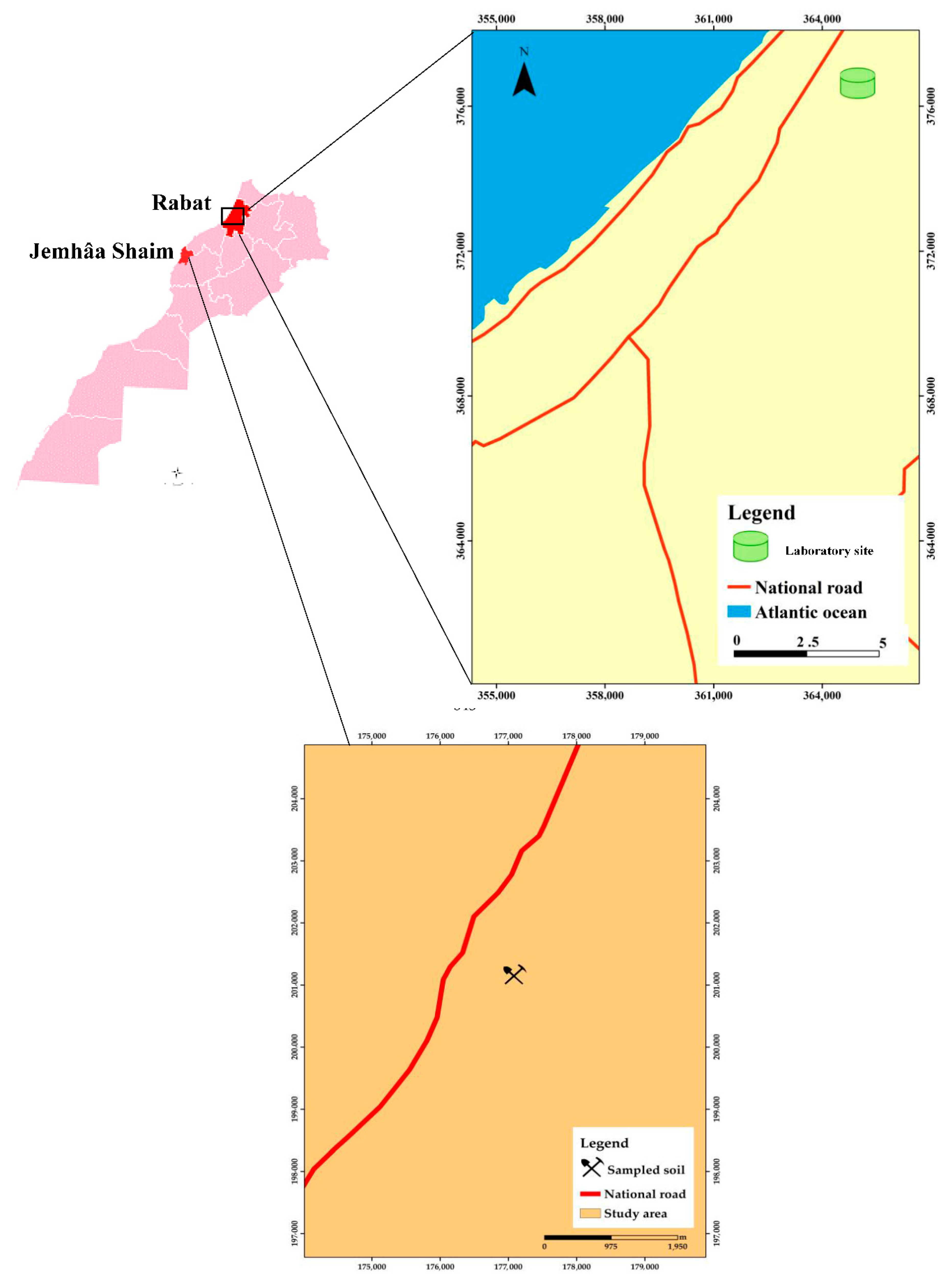

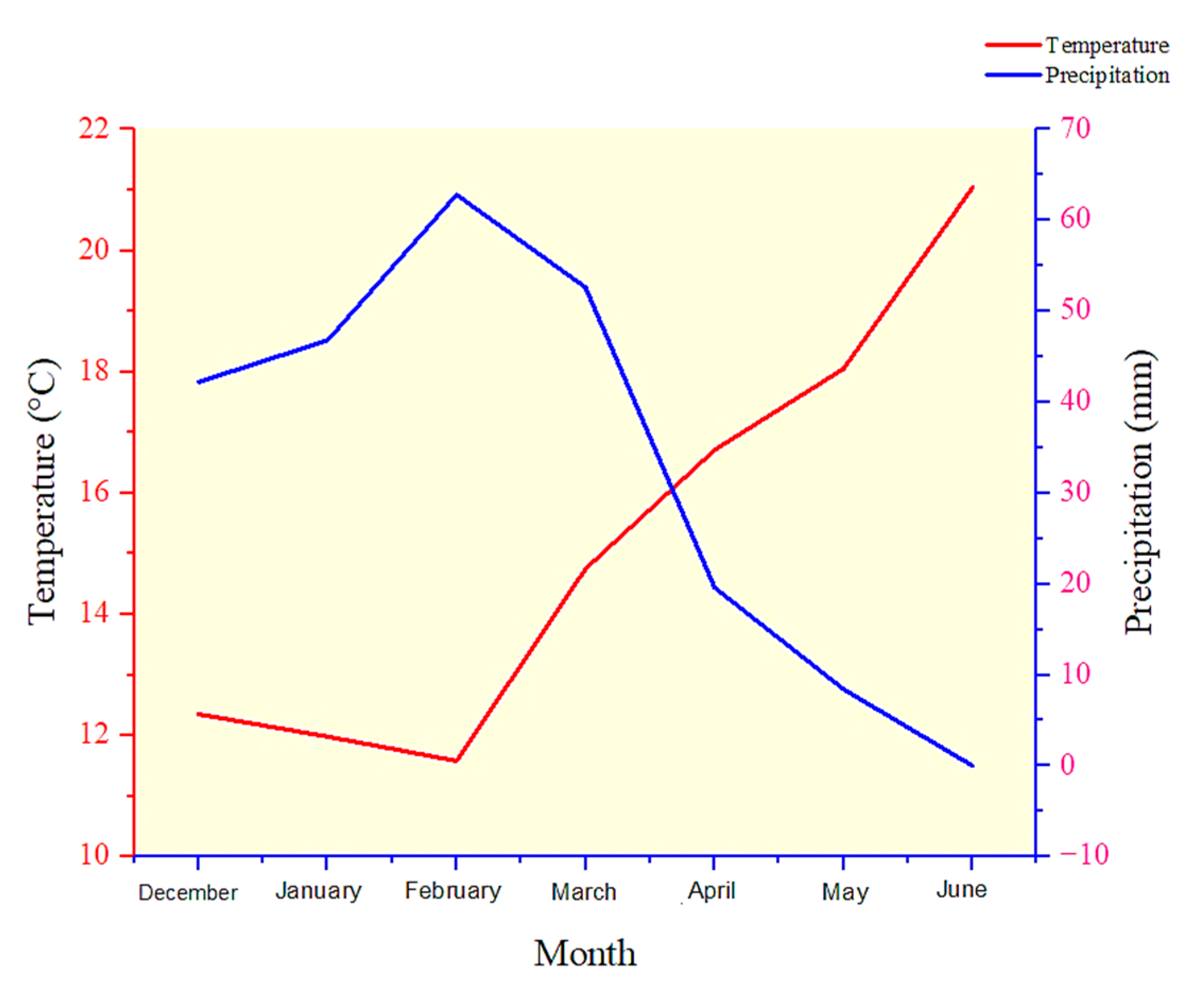

4.1. Experimental Site

4.2. Plant Material

4.3. Experimental Design

4.4. Agro-Morphological Characterization

4.5. Quality Parameters Characterization

4.5.1. Whole Grain-Based Parameters

4.5.2. Flour-Based Parameters

4.5.3. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smutka, L.; Steininger, M.; Miffek, O. World Agricultural Production and Consumption. AGRIS on-line Papers in Economics and Informatics 2009, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Smutka, L.; Steininger, M.; Maitah, M.; Škubna, O. The Czech Agrarian Foreign Trade—Ten Years after the EU Accession. In Agrarian Perspectives XXIV: Proceedings of the 24th International Scientific Conference; Glasgow, UK, 2015; pp. 385–392.

- Wegren, S.K.; Elvestad, C. Russia’s Food Self-Sufficiency and Food Security: An Assessment. Post-Communist Economies 2018, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.C.; Fraser, R.W.; Paini, D.R.; Warden, A.C.; Lonsdale, W.M.; De Barro, P.J. Biosecurity and Yield Improvement Technologies Are Strategic Complements in the Fight against Food Insecurity. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocking, M.A. Tropical Soils and Food Security: The Next 50 Years. Science 2003, 302, 1356–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinstrup-Andersen, P.; Pandya-Lorch, R. Food Security and Sustainable Use of Natural Resources: A 2020 Vision. Ecological Economics 1998, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T.R.; Slotkin, T.A. Maturation of the Adrenal Medulla--IV. Effects of Morphine. Biochem Pharmacol 1975, 24, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corwin, D.L. Climate Change Impacts on Soil Salinity in Agricultural Areas. European J Soil Science 2021, 72, 842–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Kumar, R. Soil Salinity: A Serious Environmental Issue and Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria as One of the Tools for Its Alleviation. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2015, 22, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.; Yang, J. Biosystematics of Triticeae: Volume I. Triticum-Aegilops Complex; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.D.; Koo, W.W. 2015 Outlook of the U.S. and World Wheat Industries, 2015-2024. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcfadden, E.S.; Sears, E.R. THE ORIGIN OF TRITICUM SPELTA AND ITS FREE-THRESHING HEXAPLOID RELATIVES*. Journal of Heredity 1946, 37, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, F.; Ammar, K.; Solís, I. Global Changes in Cultivated Area and Breeding Activities of Durum Wheat from 1800 to Date: A Historical Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xynias, I.N.; Mylonas, I.; Korpetis, E.G.; Ninou, E.; Tsaballa, A.; Avdikos, I.D.; Mavromatis, A.G. Durum Wheat Breeding in the Mediterranean Region: Current Status and Future Prospects. Agronomy 2020, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, S.; Marando, S.; Prandi, B.; Boukid, F.; Marmiroli, N.; Francia, E.; Pecchioni, N.; Sforza, S.; Visioli, G.; Gullì, M. Technological Quality and Nutritional Value of Two Durum Wheat Varieties Depend on Both Genetic and Environmental Factors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 2384–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidiane Sall, A.; Chiari, T.; Legesse, W.; Seid-Ahmed, K.; Ortiz, R.; Van Ginkel, M.; Bassi, F.M. Durum Wheat (Triticum Durum Desf.): Origin, Cultivation and Potential Expansion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Agronomy 2019, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanavičiūtė, I.; Bonfiglioli, L.; Pagnotta, M.A. Diversity in Root Architecture of Durum Wheat at Stem Elongation under Drought Stress. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzouk, F.Z.; Gracia-Romero, A.; Kefauver, S.C.; Nieto-Taladriz, M.T.; Serret, M.D.; Araus, J.L. Durum Wheat Ideotypes in Mediterranean Environments Differing in Water and Temperature Conditions. Agricultural Water Management 2022, 259, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghouti, M.; Bassi, F.M.; Nasrellah, N.; Amri, A.; Motawaj, J.; Nachit, M. ‘Nachit’, a Wild-relative-derived Durum Wheat Resilient to Climate Change in Morocco. J of Plant Registrations 2023, 17, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhou, K.; Moussadek, R.; Yachou, H.; Zouahri, A.; Douaik, A.; Hilal, I.; Ghanimi, A.; Hmouni, D.; Dakak, H. Assessing the Impact of Saline Irrigation Water on Durum Wheat (Cv. Faraj) Grown on Sandy and Clay Soils. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannachi, S.; Steppe, K.; Eloudi, M.; Mechi, L.; Bahrini, I.; Van Labeke, M.-C. Salt Stress Induced Changes in Photosynthesis and Metabolic Profiles of One Tolerant (‘Bonica’) and One Sensitive (‘Black Beauty’) Eggplant Cultivars (Solanum Melongena L.). Plants 2022, 11, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabti, A.; Mekaoussi, R.; Fellahi, Z.E.A.; Hannachi, A.; Benbelkacem, A.; Benmahammed, A.; Bouzerzour, H. Characterization of Old And Recent Durum Wheat [Triticum Turgidum (L.) Tell. Convar. Durum (Desf.) Mackey] Varieties Assessed under South Mediterranean Conditions. Egypt. J. Agron. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellahi, Z.E.A.; Hannachi, A.; Bouzerzour, H. Analysis of Direct and Indirect Selection and Indices in Bread Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) Segregating Progeny. International Journal of Agronomy 2018, 2018, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, C.R.; Mezzomo, H.C.; Silva, C.M.; Lima, G.W.; Souza, D.J.P.; Borém, A.; Nardino, M. Selection Indexes Based on Genotypic Values Applied to Brazilian Tropical Wheat Breeding. Agron. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, A.A.; Safhi, F.A.; El-Hity, M.A.; Kamara, M.M.; Gamal El-Din, E.M.; Rehan, M.; Farid, M.; Behiry, S.I.; El-Soda, M.; Mansour, E. Molecular Genetic Diversity of Local and Exotic Durum Wheat Genotypes and Their Combining Ability for Agronomic Traits under Water Deficit and Well-Watered Conditions. Life 2023, 13, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroupin, P.Yu.; Bespalova, L.A.; Kroupina, A.Yu.; Yanovsky, A.S.; Korobkova, V.A.; Ulyanov, D.S.; Karlov, G.I.; Divashuk, M.G. Association of High-Molecular-Weight Glutenin Subunits with Grain and Pasta Quality in Spring Durum Wheat (Triticum Turgidum Spp. Durum L.). Agronomy 2023, 13, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICARDA (International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas) Morocco and ICARDA: Collaboration since 1977; 2005.

- International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) ICARDA Annual Report; ICARDA: Aleppo, Syria, 1989.

- International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) Landraces in Crop Breeding; ICARDA: Aleppo, Syria, 1996.

- Mona, T.; Nsarellah, N. ; F., G.; Atmane, R. Multi-Environment Assessment of the Impact of Genetic Improvement on Agronomic Performance and on Grain Quality Traits in Moroccan Durum Wheat Varieties of 1949 to 2017. 2017.

- Nsarellah, N.; Amamou, A.; Mona, T.; Annicchiarico, P. Adaptation of Moroccan Durum Wheat Varieties from Different Breeding Eras. Journal of Plant Breeding and Crop Science 2011, 3, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Broccanello, C.; Bellin, D.; DalCorso, G.; Furini, A.; Taranto, F. Genetic Approaches to Exploit Landraces for Improvement of Triticum Turgidum Ssp. Durum in the Age of Climate Change. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katerji, N.; Van Hoorn, J.W.; Hamdy, A.; Mastrorilli, M.; Nachit, M.M.; Oweis, T. Salt Tolerance Analysis of Chickpea, Faba Bean and Durum Wheat Varieties. Agricultural Water Management 2005, 72, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters Haugrud, A.R.; Achilli, A.L.; Martínez-Peña, R.; Klymiuk, V. Future of Durum Wheat Research and Breeding: Insights from Early Career Researchers. The Plant Genome 2025, 18, e20453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazco, R.; Villegas, D.; Ammar, K.; Peña, R.J.; Moragues, M.; Royo, C. Can Mediterranean Durum Wheat Landraces Contribute to Improved Grain Quality Attributes in Modern Cultivars? Euphytica 2012, 185, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.S.; El-Basyoni, I.; Baenziger, P.S.; Singh, S.; Royo, C.; Ozbek, K.; Aktas, H.; Ozer, E.; Ozdemir, F.; Manickavelu, A.; et al. Exploiting Genetic Diversity from Landraces in Wheat Breeding for Adaptation to Climate Change. EXBOTJ 2015, 66, 3477–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.M.; Villegas, D.; Sorrells, M.E.; Royo, C. Durum Wheat Landraces from East and West Regions of the Mediterranean Basin Are Genetically Distinct for Yield Components and Phenology. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bellido, L.; López-Bellido, R.J.; Redondo, R. Nitrogen Efficiency in Wheat under Rainfed Mediterranean Conditions as Affected by Split Nitrogen Application. Field Crops Research 2005, 94, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantha, S.; Kilian, B.; Özkan, H.; Zeibig, F.; Frei, M. Physiological and Biochemical Changes Induced by Drought Stress during the Stem Elongation and Anthesis Stages in the Triticum Genus. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2024, 228, 106047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridi, E.; Kapazoglou, A.; Gerakari, M.; Kleftogianni, K.; Passa, K.; Sarri, E.; Papasotiropoulos, V.; Tani, E.; Bebeli, P.J. Crop Landraces and Indigenous Varieties: A Valuable Source of Genes for Plant Breeding. Plants 2024, 13, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, M.A.; Adubi, A.O.; Durodola, F.A. Landraces and Crop Genetic Improvement. In Rediscovery of Landraces as a Resource for the Future; Grillo, O., Ed.; InTech, 2018 ISBN 978-1-78923-724-5.

- Xu, Z.; Lai, X.; Ren, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Xia, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Geng, H.; et al. Impact of Drought Stress on Yield-Related Agronomic Traits of Different Genotypes in Spring Wheat. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Ceccarelli, S.; Blair, M.W.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Are, A.K.; Ortiz, R. Landrace Germplasm for Improving Yield and Abiotic Stress Adaptation. Trends in Plant Science 2016, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Gallego, G.; Guzmán, G.I.; Garcia-Ruíz, R.; González De Molina, M.; Aguilera, E. Addressing the Role of Landraces in the Sustainability of Mediterranean Agroecosystems. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marone, D.; Russo, M.A.; Mores, A.; Ficco, D.B.M.; Laidò, G.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Borrelli, G.M. Importance of Landraces in Cereal Breeding for Stress Tolerance. Plants 2021, 10, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnaw, T.; Mulugeta, B.; Haileselassie, T.; Geleta, M.; Ortiz, R.; Tesfaye, K. Genetic Diversity of Durum Wheat (Triticum Turgidum L. Ssp. Durum, Desf) Germplasm as Revealed by Morphological and SSR Markers. Genes 2023, 14, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, A.; Corinzia, S.A.; Caruso, P.; Cosentino, S.L.; Testa, G. Productivity of Wheat Landraces in Rainfed and Irrigated Conditions under Conventional and Organic Input in a Semiarid Mediterranean Environment. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corinzia, S.A.; Caruso, P.; Scandurra, A.; Anastasi, U.; Cosentino, S.L.; Testa, G. Yield Response and Leaf Gas Exchange of Sicilian Wheat Landraces. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slafer, G.A.; Andrade, F.H. Changes in Physiological Attributes of the Dry Matter Economy of Bread Wheat (Triticum Aestivum) through Genetic Improvement of Grain Yield Potential at Different Regions of the World: A Review. Euphytica 1991, 58, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.; Mares, D.; Moss, H.; Ellison, F. Effects of Grain Shape and Size on Milling Yields in Wheat. II. Experimental Studies. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1986, 37, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantová, N.; Rábek, M.; Elzner, P.; Středa, T.; Jovanović, I.; Holková, L.; Martinek, P.; Smutná, P.; Prášil, I.T. Different Drought Tolerance Strategy of Wheat Varieties in Spike Architecture. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Egidio, M.G.; Mariani, B.M.; Nardi, S.; Novaro, P.; Cubadda, R. Chemical and Technological Variables and Their Relationships: A Predictive Equation for Pasta Cooking Quality. Cereal Chemistry 1990, 67, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, A.; Mangini, G.; Giancaspro, A.; Giove, S.; Colasuonno, P.; Simeone, R.; Signorile, A.; De Vita, P.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Cattivelli, L.; et al. Relationships between Grain Protein Content and Grain Yield Components through Quantitative Trait Locus Analyses in a Recombinant Inbred Line Population Derived from Two Elite Durum Wheat Cultivars. Mol Breeding 2012, 30, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, J.E.; Matsuo, R.R. INFLUENCE OF PROTEIN CONTENT ON SOME DURUM WHEAT QUALITY PARAMETERS. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1977, 57, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, J.E.; Matsuo, R.R. Relationship between Durum Wheat Protein Properties and Pasta Dough Rheology and Spaghetti Cooking Quality. J Agric Food Chem 1980, 28, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrão Martins, R.; Nunes, M.C.; M. Ferreira, L.M.; A. Peres, J.; R. N. A. Barros, A.I.; Raymundo, A. Impact of Acorn Flour on Gluten-Free Dough Rheology Properties. Foods 2020, 9, 560. [CrossRef]

- Delcour, J.A.; Joye, I.J.; Pareyt, B.; Wilderjans, E.; Brijs, K.; Lagrain, B. Wheat Gluten Functionality as a Quality Determinant in Cereal-Based Food Products. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 3, 469–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamat, H.; Hill, S.E. Effect of Fat Types on the Structural and Textural Properties of Dough and Semi-Sweet Biscuit. J Food Sci Technol 2014, 51, 1998–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficco, D.B.M.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Trono, D.; Borrelli, G.M.; De Vita, P.; Fares, C.; Beleggia, R.; Platani, C.; Papa, R. The Colours of Durum Wheat: A Review. Crop Pasture Sci. 2014, 65, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage (CIE) Colorimetry; 2nd Edition.; Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage: Vienna, 1986.

- Sharma, C.; Kamle, M.; Kumar, P. Microbial-Derived Carotenoids and Their Health Benefits. Microbiology Research 2024, 15, 1670–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazco, R.; Peña, R.J.; Ammar, K.; Villegas, D.; Crossa, J.; Moragues, M.; Royo, C. Variability in Glutenin Subunit Composition of Mediterranean Durum Wheat Germplasm and Its Relationship with Gluten strengthVariability. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 152, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, V.; Kranl, K.; Hollmann, J.; Lindhauer, M.G.; Böhm, V.; Bitsch, R. Spectrophotometric Determination of Yellow Pigment Content and Evaluation of Carotenoids by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography in Durum Wheat Grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6663–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.-A. Global Synthesis of Drought Effects on Maize and Wheat Production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, H.; Lan, L.; Huang, R.; Deng, X.; Peng, Y. Effects of Exponential N Application on Soil Exchangeable Base Cations and the Growth and Nutrient Contents of Clonal Chinese Fir Seedlings. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktaş, H. drought tolerance indices of selected landraces and bread wheat (triticum aestivum l.) genotypes derived from synthetic wheats. Appl Ecol Env Res 2016, 14, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Jiang, C.; Tang, C.; Nie, X.; Du, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H.; Kang, Z.; et al. Wheat Adaptation to Environmental Stresses under Climate Change: Molecular Basis and Genetic Improvement. Molecular Plant 2023, 16, 1564–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Zazueta, C.A.; Crespo-Herrera, L.A.; Piñera-Chavez, F.J.; Rivera-Amado, C.; Aradottir, G.I. Climate Change Impacts on Crop Breeding: Targeting Interacting Biotic and Abiotic Stresses for Wheat Improvement. The Plant Genome 2024, 17, e20365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltaher, S.; Sallam, A.; Emara, H.A.; Nower, A.A.; Salem, K.F.M.; Börner, A.; Baenziger, P.S.; Mourad, A.M.I. Genome-Wide Association Mapping Revealed SNP Alleles Associated with Spike Traits in Wheat. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, Y.A.; Anley, A.M.; Abebe, T.D. Genetic Variability and Association of Traits in Ethiopian Durum Wheat (Triticum Turgidium L. Var. Durum) Landraces at Dabat Research Station, North Gondar. Cogent Food & Agriculture 2020, 6, 1778604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, J.S. Plant Productivity and Environment. Science 1982, 218, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustos, D.V.; Hasan, A.K.; Reynolds, M.P.; Calderini, D.F. Combining High Grain Number and Weight through a DH-Population to Improve Grain Yield Potential of Wheat in High-Yielding Environments. Field Crops Research 2013, 145, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Sharifi, P.; Karimizadeh, R.; Shefazadeh, M.K. Relationships between Grain Yield and Yield Components in Bread Wheat under Different Water Availability (Dryland and Supplemental Irrigation Conditions). Not Bot Hort Agrobot Cluj 2012, 40, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisslitz, S.; Longin, C.F.H.; Scherf, K.A.; Koehler, P. Comparative Study on Gluten Protein Composition of Ancient (Einkorn, Emmer and Spelt) and Modern Wheat Species (Durum and Common Wheat). Foods 2019, 8, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwinski, E.L.; Kolster, P.; Prins, A.; Vliet, T. van On the Relationship between Gluten Protein Composition of Wheat Flours and Large-Deformation Properties of Their Doughs. Journal of Cereal Science 2004, 39, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, L.; Cardós, M.; Campaña, L.; Ferrero, C. Effect of Glutens of Different Quality on Dough Characteristics and Breadmaking Performance. LWT—Food Science and Technology 2012, 46, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.; Vazquez, J.; Orkellana, J. Relationship Between Gluten Strength and Glutenin Proteins in Durum Wheat Cultivars. Plant Breeding 2006, 104, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, J.M.; Vazquez, J.F.; Orkellana, J. Relationship Between Gluten Strength and Glutenin Proteins in Durum Wheat Cultivars. Plant Breeding 1990, 104, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.; Alshegaihi, R.; Mahgoub, El.; Mansour, E.; Atallah, O.; Sattar, M.; Al-Mssallem, M.; Alessa, F.; Aldaej, M.; Hassanin, A. Association of High and Low Molecular Weight Glutenin Subunits with Gluten Strength in Tetraploid Durum Wheat (Triticum Turgidum Spp. Durum L.). Plants 2023, 12, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Singh, N.; Kaur, S.; Katyal, M.; Virdi, A.S.; Kaur, D.; Ahlawat, A.K.; Singh, A.M. Relationship of Various Flour Properties with Noodle Making Characteristics among Durum Wheat Varieties. Food Chemistry 2015, 188, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Taladriz, M.T.; Perretant, M.R.; Rousset, M. Effect of Gliadins and HMW and LMW Subunits of Glutenin on Dough Properties in the F6 Recombinant Inbred Lines from a Bread Wheat Cross. Theoret. Appl. Genetics 1994, 88, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Kumar, A.; Oladzad-Abbasabadi, A.; Salsman, E.; Aoun, M.; Manthey, F.A.; Elias, E.M. Association Mapping for 24 Traits Related to Protein Content, Gluten Strength, Color, Cooking, and Milling Quality Using Balanced and Unbalanced Data in Durum Wheat [Triticum Turgidum L. Var. Durum (Desf).]. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadizadeh, M.; Valizadeh, M.; Shahbazy, H.; Zaefizadeh, M.; Habibpor, M. Morphological Diversity and Interrelationships Traits in Durum Wheat Landraces under Normal Irrigation and Drought Stress Conditions. Advances in Environmental Biology 2011, 5, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Sourour, A.; Chahine, K.; Youssef, T.; Olfa, S.; Hajer, S. Phenotypic Diversity of Tunisian Durum Wheat Landraces. African Crop Science Journal 2010, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Chhikara, N.; Khatkar, B.S. Characterisation of Indian Wheat Varieties for Chapatti (Flat Bread) Quality. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences 2019, 18, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailu, F.; Merker, A.; Singh, H.; Belay, G.; Johansson, E. Multivariate Analysis of Diversity of Tetraploid Wheat Germplasm from Ethiopia. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2006, 53, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) Descriptors for Wheat (Revised); International Board for Plant Genetic Resources, 1985; p. 12 p.

- AOAC Association of Official Analytical Chemists Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; 20th ed.; AOAC International: Benjamin Franklin Station, Washington, DC, 2016.

- International Organization for Standardization Cereals and Cereal Products—Determination of Moisture Content (Reference Method) 2009.

- International Organization for Standardization Cereals and Cereal Products—Determination of the Gluten Content—Part 2: Spectrometric Method 2015.

- American Association of Cereal Chemists International (AACC) Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists, 10th Ed.; AACC International.; St. Paul, MN, 2000.

- Santra, M.; Rao, V.S.; Tamhankar, S.A. Modification of AACC Procedure for Measuring β-Carotene in Early Generation Durum Wheat. Cereal Chem 2003, 80, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Variation | Parameters | Df | SS | MS | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWL | 4 | 5.58 | 9.93 | < 0.05* | |

| SL | 4 | 6.10 | 1.55 | < 0.05* | |

| Inter-group | SPS | 4 | 1.92 | 0.48 | > 0.05 ns |

| GNS | 4 | 379.35 | 97.13 | > 0.05 ns | |

| TKW | 4 | 559.12 | 136.56 | < 0.01** | |

| GY | 4 | 13.67 | 3.58 | < 0.05* |

| Source of Variation | Parameters | Df | SS | MS | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-group | PC | 4 | 9.56 | 2.37 | < 0.01** |

| GC | 4 | 64.92 | 16.23 | < 0.01** | |

| W | 4 | 12686.25 | 3174.06 | > 0.05 ns | |

| SDS | 4 | 21.22 | 5.59 | < 0.05* | |

| YI | 4 | 5.37 | 1.39 | < 0.01** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).