Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Culture-Based Assessment of Bacteriological Contamination

2.2. Concentration of Antimicrobial Agents

| Chemical group | Antibiotic | BDF_W | BDF_R | BDF_S | B1_W | B1_R | B1_S | R_W | R_S | B3_W | B3_S | BDZ_W | BDZ_S | frequency of detection (% of all samples) |

Total concentration of antibiotic in all samples (ng/l) |

| 2nd gen. cephalosporins | cefoxitin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 112.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 73.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.7 | 519.05 |

| fluoroquinolones | ciprofloxacin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 65.20 | 24.31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 15.37 | 9.7 | 314.65 |

| enrofloxacin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.67 | 6.09 | 3.04 | 626.28 | 34.95 | 3.38 | 0.95 | 2.94 | 0.00 | 3.2 | 204.78 | |

| ofloxacin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 95.64 | 28.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.00 | 6.29 | 29.0 | 2030.53 | |

| lincosamids | clindamycin | 0.51 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.83 | <LOQ | 2.47 | 37.66 | 9.96 | 5.80 | 0.00 | 15.59 | 11.18 | 29.0 | 3.71 |

| macrolides | erythromycin | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.30 | 0.20 | 71.0 | 251.15 |

| tylosin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 56.59 | 10.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 22.6 | 64.45 | |

| tetracyclines | doxycycline | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 68.26 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 16.1 | 413.43 |

| oxytetracycline | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 61.36 | 6.5 | 224.46 | |

| tetracycline | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 9.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 35.5 | 214.61 | |

| sulphonamids | sulfamethoxazole | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.56 | 20.90 | 4.69 | 1.48 | 0.00 | 34.05 | 8.83 | 3.2 | 27.70 |

| antifolates | trimethoprim | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.10 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 38.57 | 7.70 | 2.59 | 0.00 | 8.61 | 4.93 | 35.5 | 188.63 |

| glycopeptides | vancomycin | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 142.66 | 21.84 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.23 | 0.00 | 9.7 | 506.19 |

| oxazolidinones | linezolid | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.33 | 17.40 | 1.48 | 1.63 | 0.00 | 3.99 | 1.55 | 6.5 | 200.44 |

| number of antibiotics detected | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 8 | |||

| total concentration of antibiotics | 1.21 | 0 | 225.19 | 15.45 | 12.17 | 328.40 | 3559.06 | 431.37 | 29.77 | 1.90 | 230.14 | 329.10 | |||

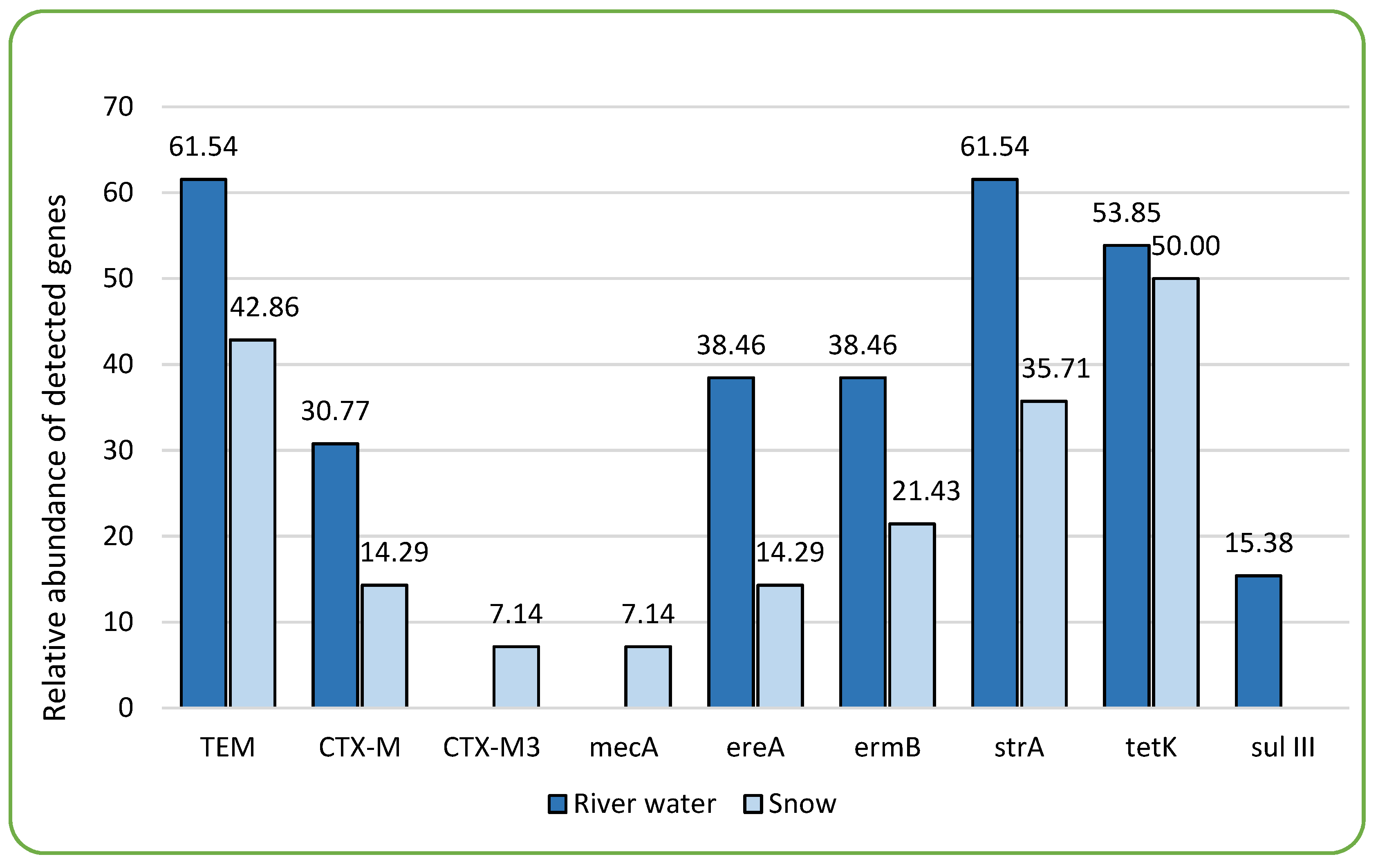

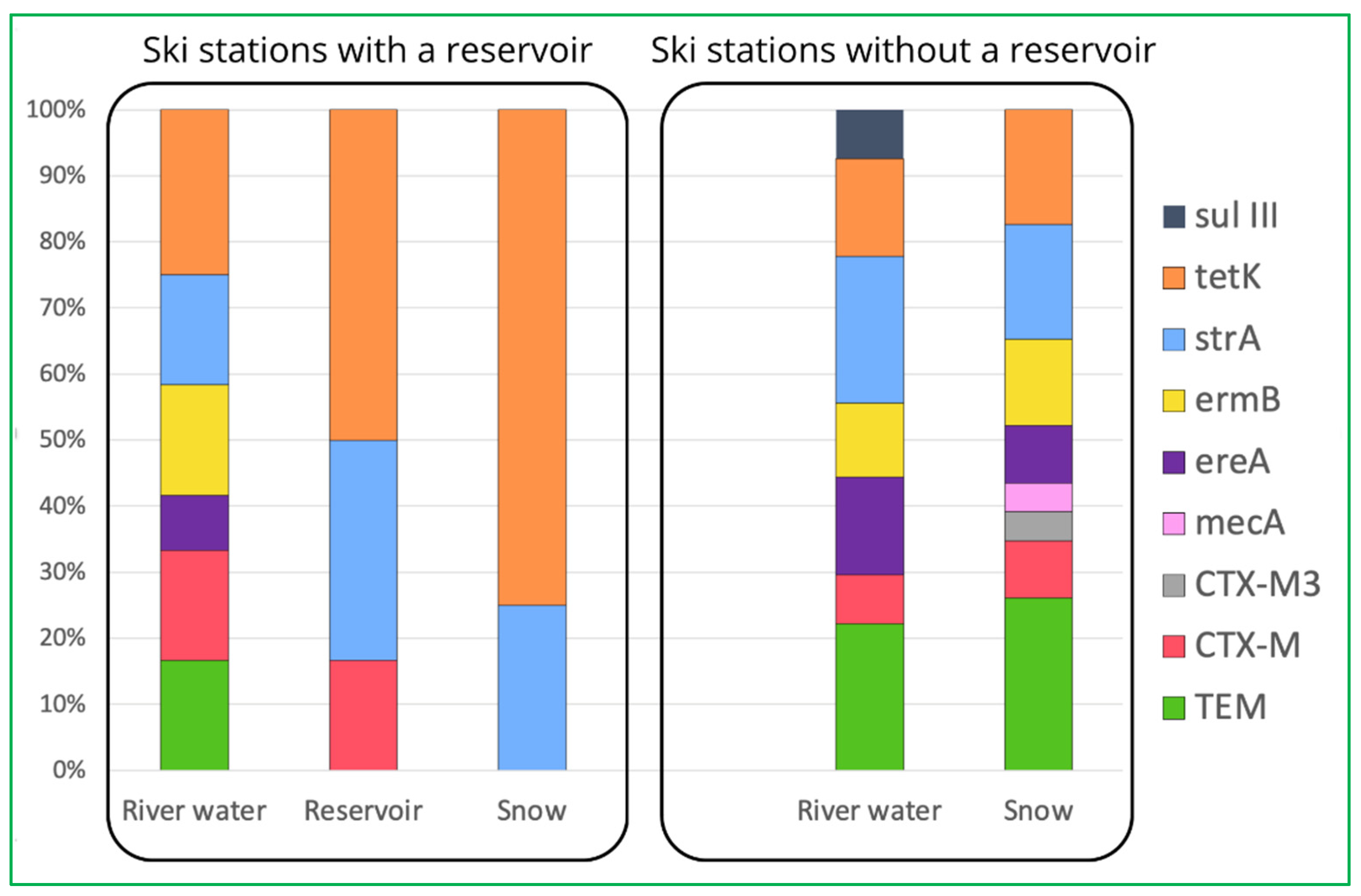

2.3. Detection and Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs)

| Site | beta-lactamases | altered penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a) | erythromycin esterase | macrolide ribosomal methylase | Aminoglycoside 3'-phosphotransferase | tetracycline efflux protein | dihydropteroate synthase | ||

| blaTEM | blaCTX-M | blaCTX-M3 | mecA | ereA | ermB | strA | tetK | sulIII | |

| BDF | 16.7 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16.7 | 50.0 | 0 |

| B3 | 50.0 | 25.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50.0 | 0 |

| B1 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | 37.5 | 75 | 0 |

| R | 66.7 | 16.7 | 0 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 0 | 66.7 | 33.3 | 16.7 |

| BDZ | 100 | 33.3 | 16.7 | 0 | 83.3 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 | 16.7 |

| total share | 46.7 | 20.0 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 20.0 | 23.3 | 46.7 | 56.7 | 6.7 |

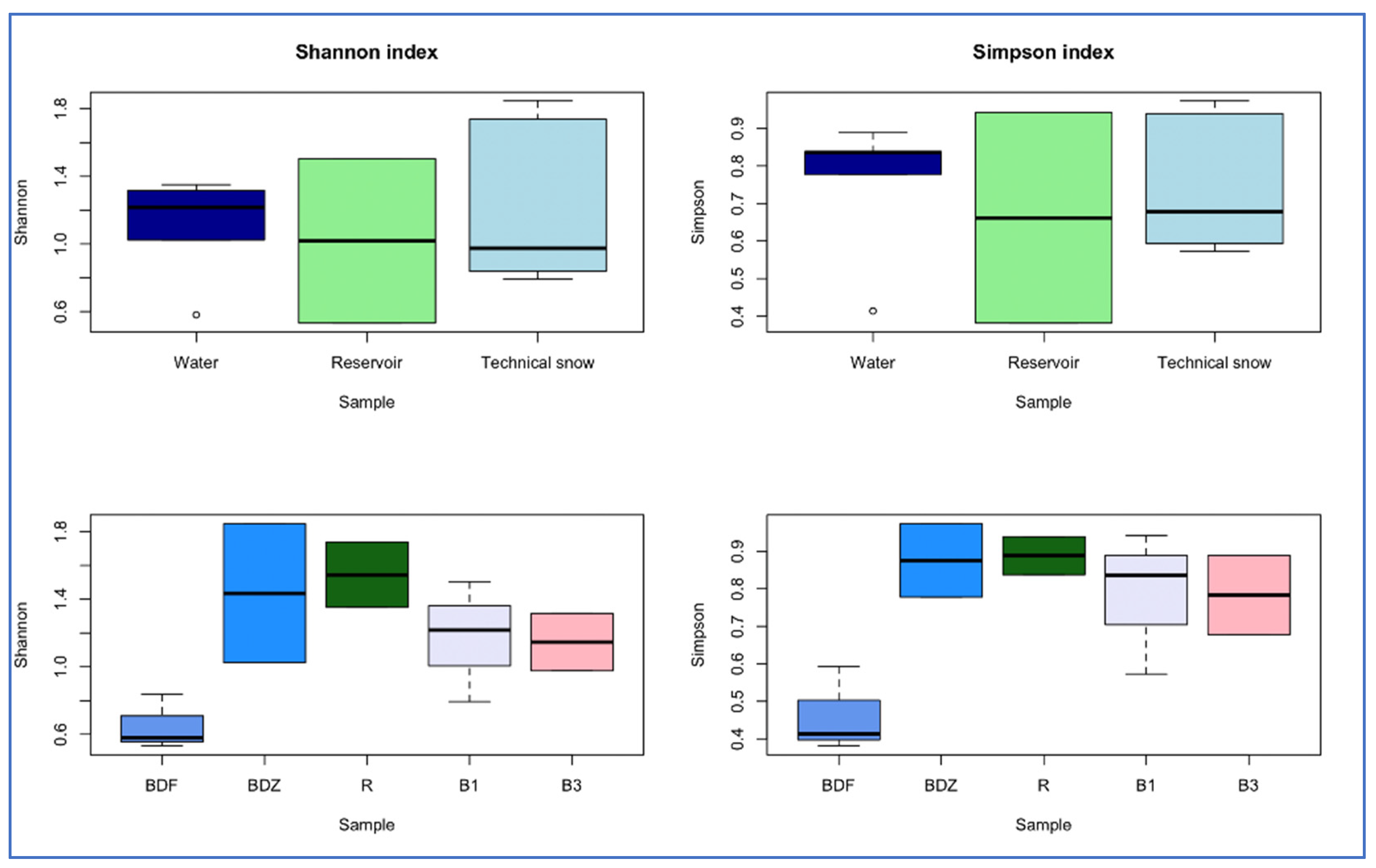

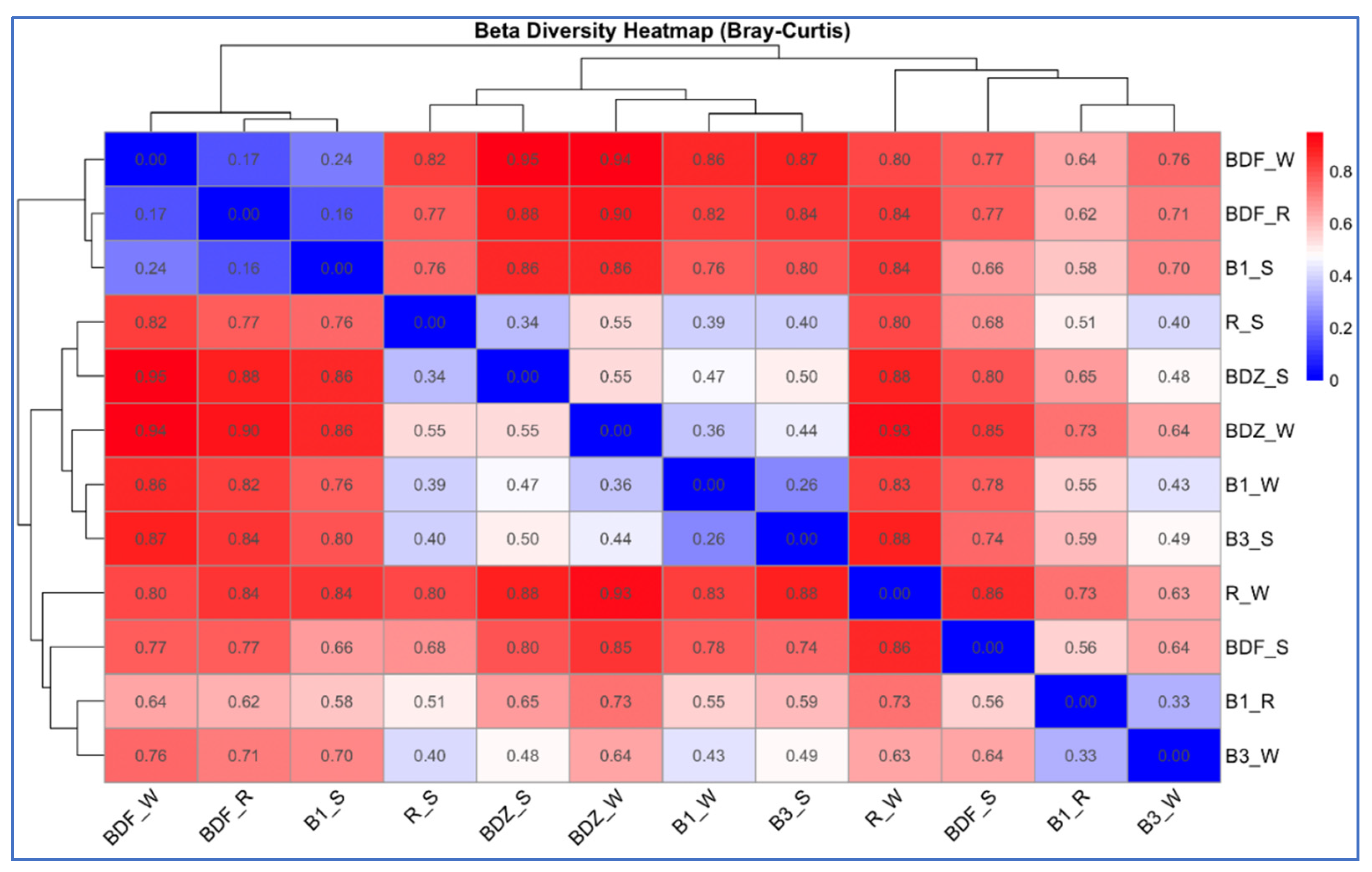

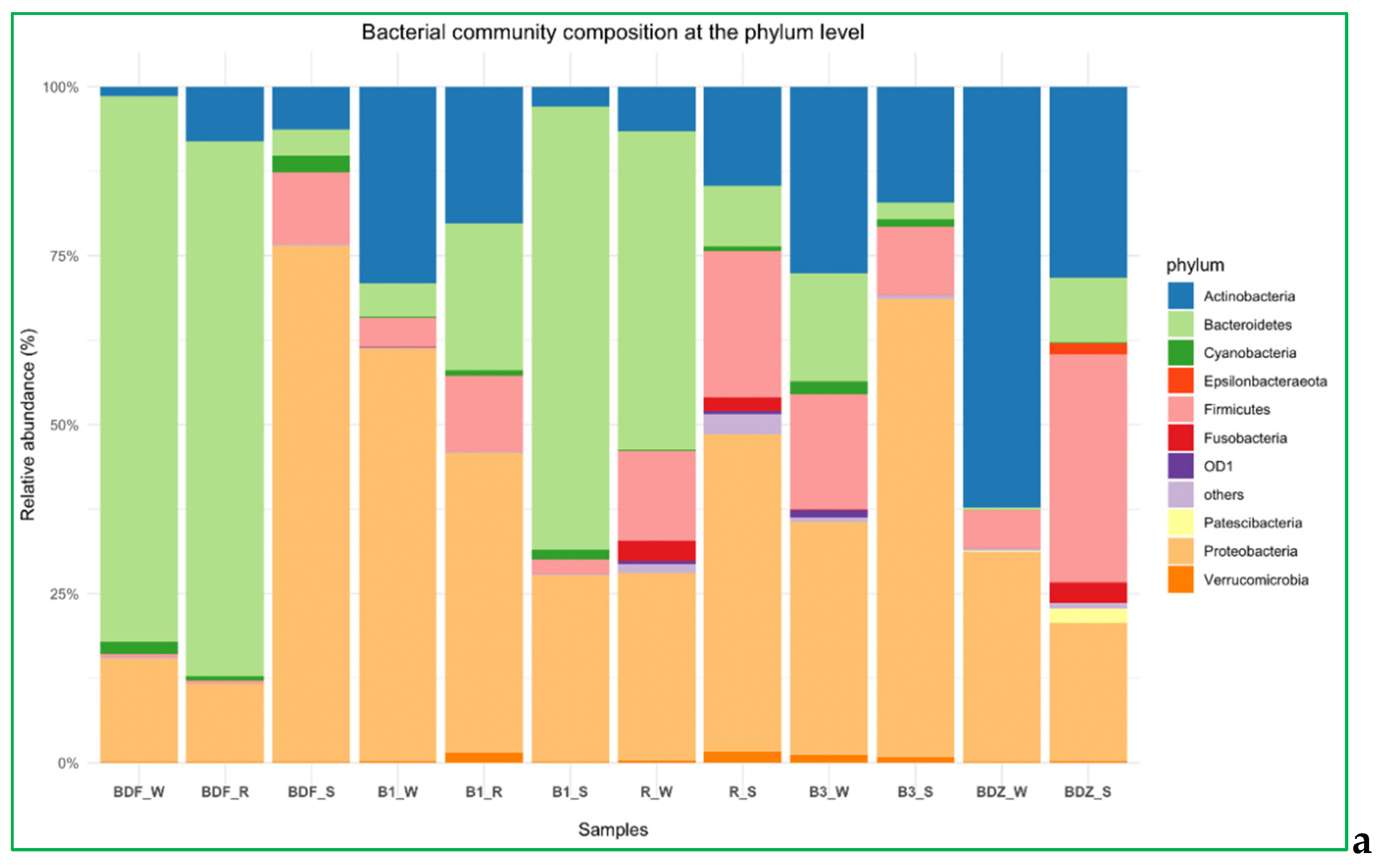

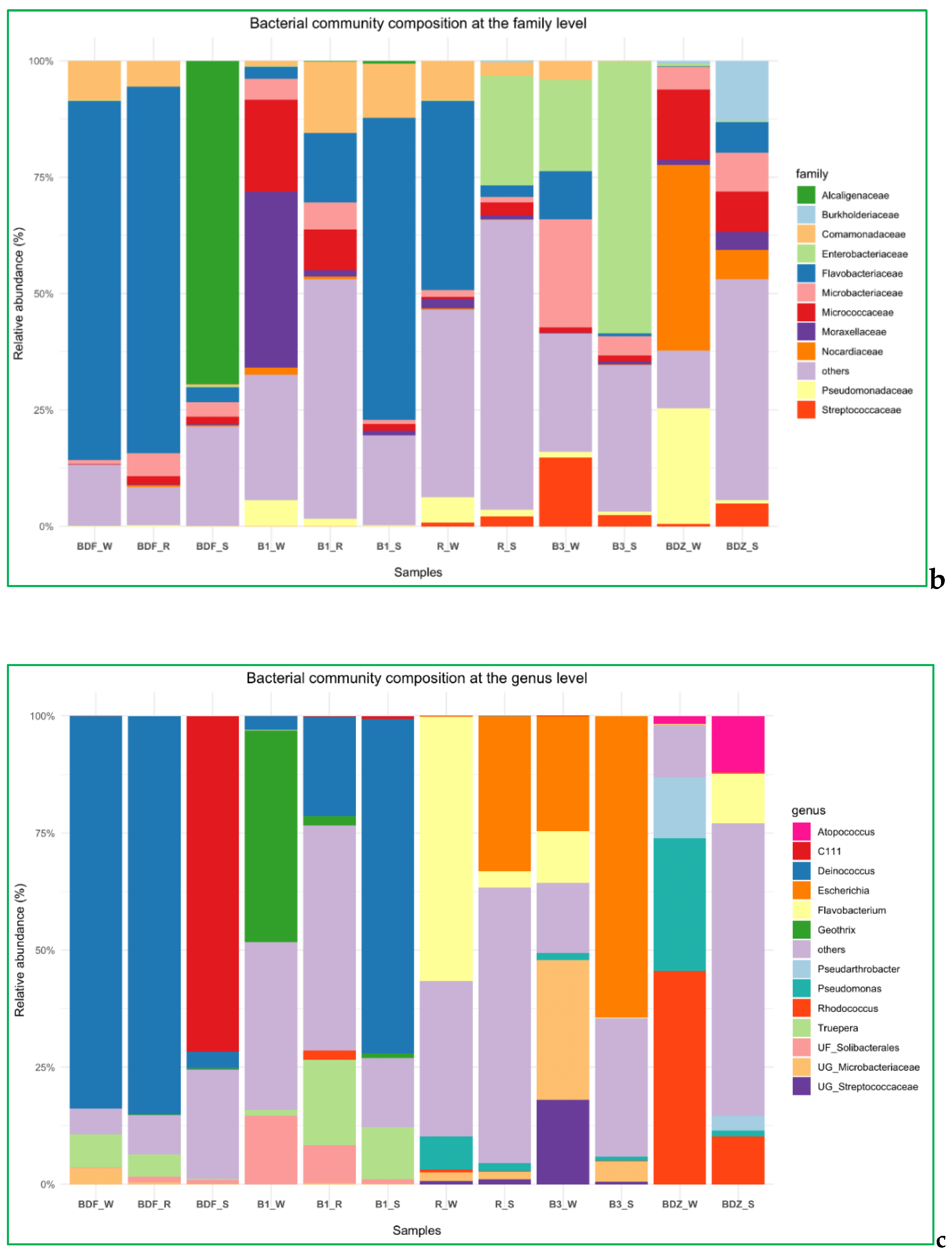

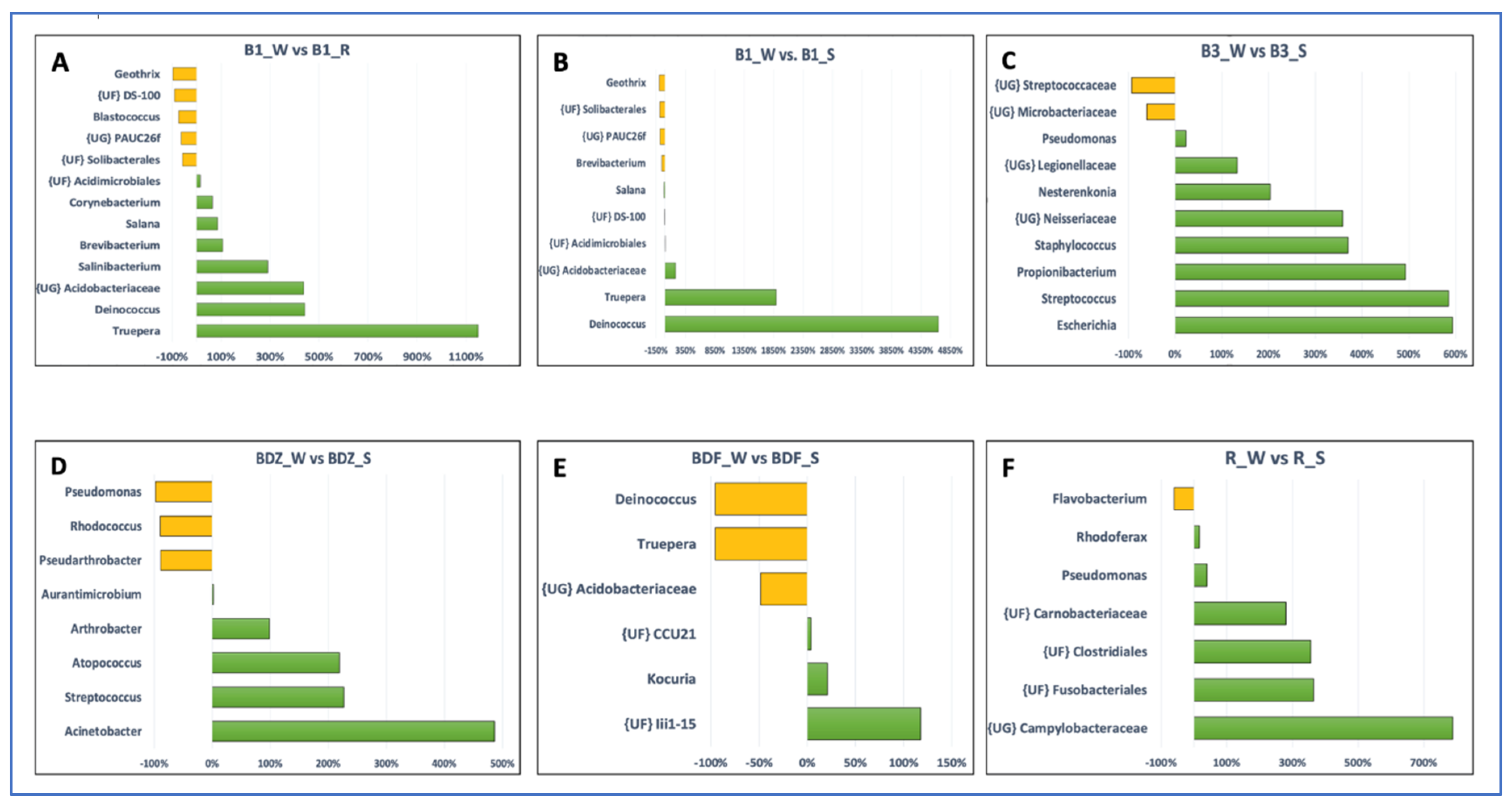

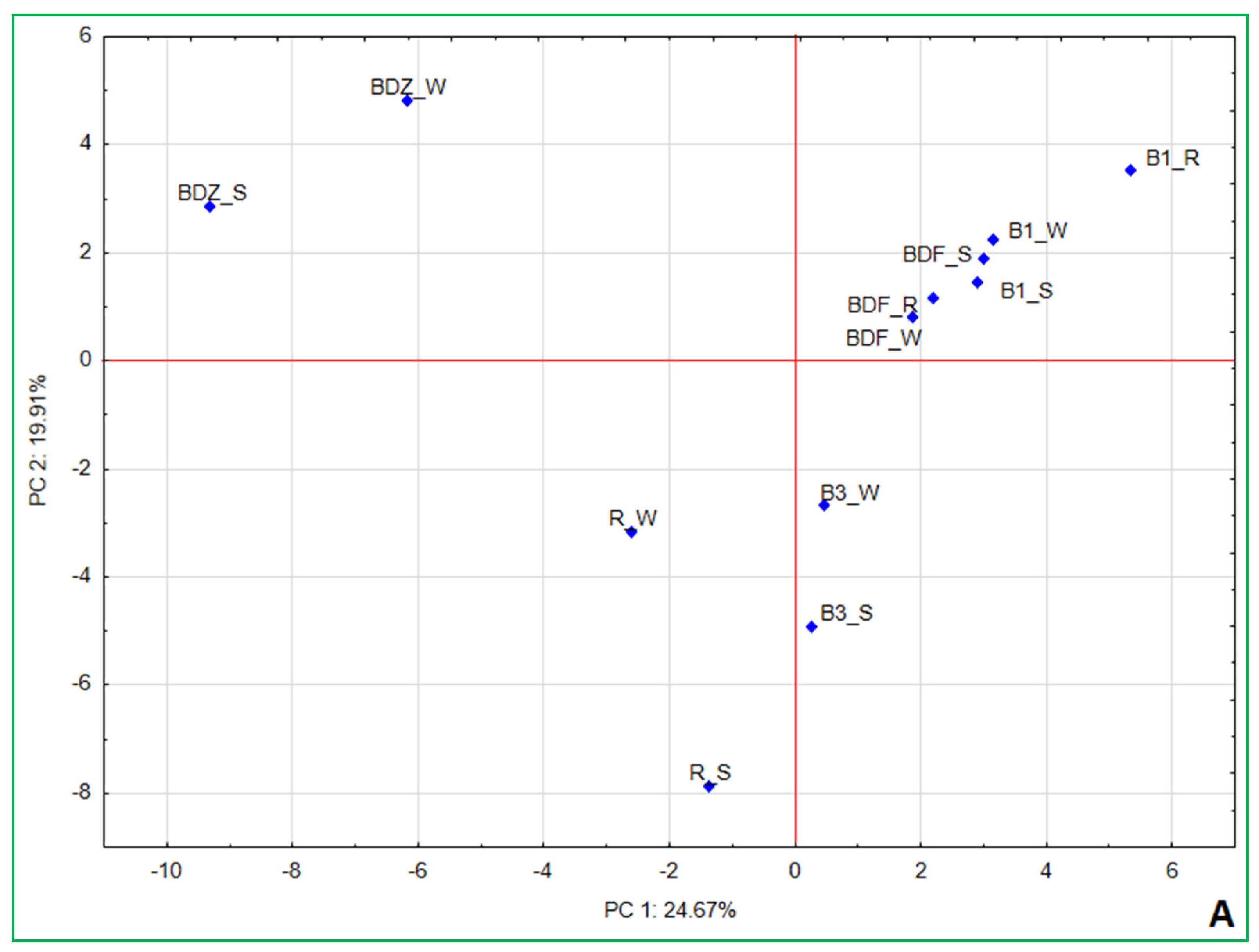

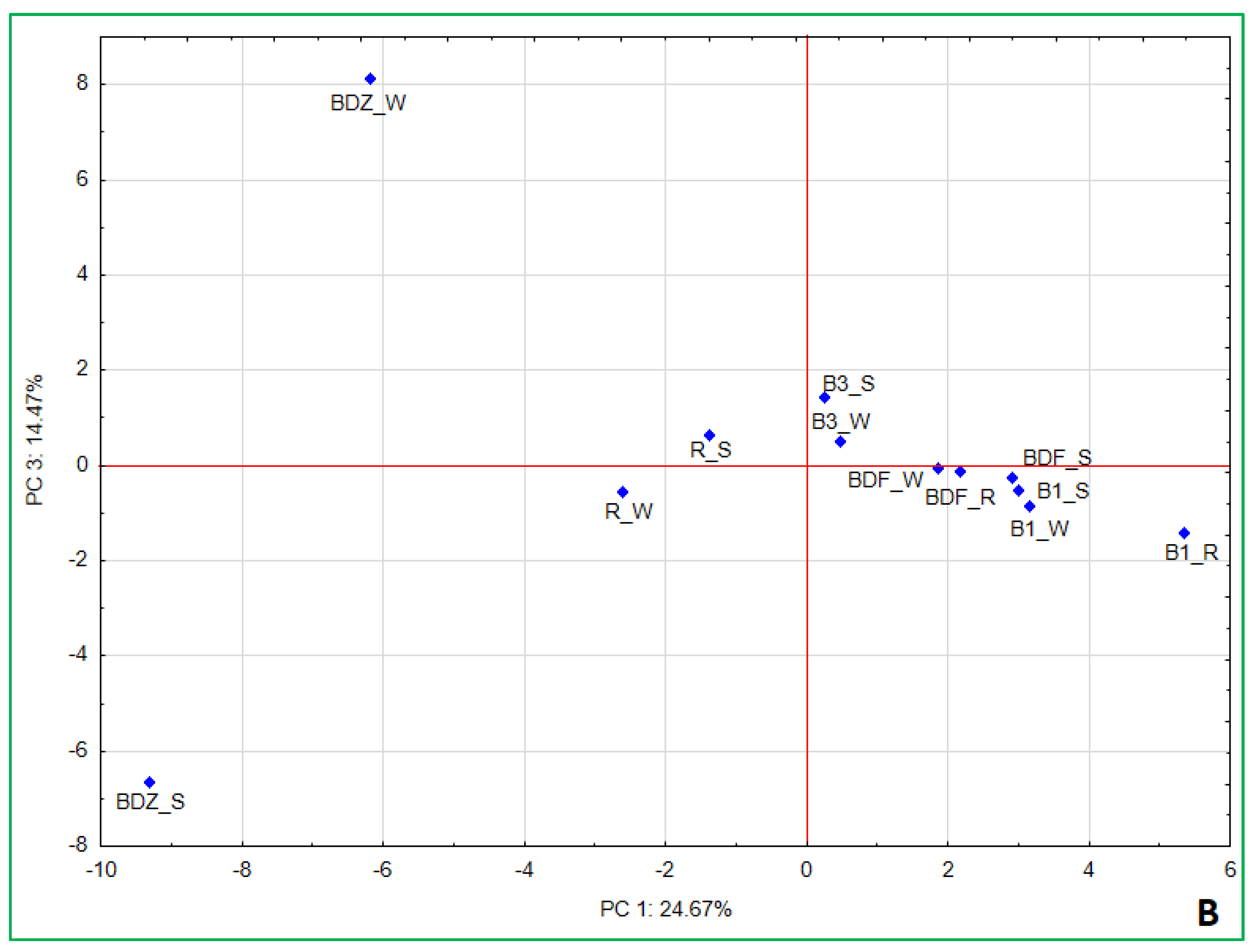

2.4. Bacterial Community Diversity, Composition and Multivariate Data Analyses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Sites

3.2. Sample Collection

3.3. Culture-Based Microbiological Analysis of Samples

3.4. Determining the Presence and Concentration of Antimicrobial Agents in Water and Snowmelt Samples

3.5. PCR Determination of Genetic Antimicrobial Resistance Determinants in Total Genomic DNA

3.6. Illumina Sequencing of V3-V4 16S rRNA Amplicon

3.7. Statistical Analyses

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lenart-Boroń, A.; Wolanin, A.; Jelonkiewicz, Ł.; Chmielewska-Błotnicka, D.; Zelazny, M. Spatiotemporal Variability in Microbiological Water Quality of the Białka River and Its Relation to the Selected Physicochemical Parameters of Water. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution 2016, 227. [CrossRef]

- Lenart-Boroń, A.; Prajsnar, J.; Guzik, M.; Boroń, P.; Chmiel, M. How Much of Antibiotics Can Enter Surface Water with Treated Wastewater and How It Affects the Resistance of Waterborne Bacteria: A Case Study of the Białka River Sewage Treatment Plant. Environmental research 2020, 191, 110037. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, C. Artificial Production of Snow. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series 2011, Part 3, 61–66. [CrossRef]

- Rixen, C.; Stoeckli, V.; Ammann, W. Does Artificial Snow Production Affect Soil and Vegetation of Ski Pistes? A Review. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 2003, 5, 219–230. [CrossRef]

- Lagriffoul, A.; Boudenne, J.-L.; Absi, R.; Ballet, J.-J.; Berjeaud, J.-M.; Chevalier, S.; Creppy, E.E.; Gilli, E.; Gadonna, J.-P.; Gadonna-Widehem, P.; et al. Bacterial-Based Additives for the Production of Artificial Snow: What Are the Risks to Human Health? Science of The Total Environment 2010, 408, 1659–1666. [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, A.; Nebot, C.; Miranda, J.M.; Vázquez, B.I.; Abuín, C.M.F.; Cepeda, A. Determination of the Presence of Three Antimicrobials in Surface Water Collected from Urban and Rural Areas. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 2013, 2, 46–57. [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.; Kannan, A.; Holton, E.; Jagadeesan, K.; Mageiros, L.; Standerwick, R.; Craft, T.; Barden, R.; Feil, E.J.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B. Antimicrobials and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in a One-Year City Metabolism Longitudinal Study Using Wastewater-Based Epidemiology. Environmental Pollution 2023, 333, 122020. [CrossRef]

- Osorio, V.; Marcé, R.; Pérez, S.; Ginebreda, A.; Cortina, J.L.; Barceló, D. Occurrence and Modeling of Pharmaceuticals on a Sewage-Impacted Mediterranean River and Their Dynamics under Different Hydrological Conditions. Science of The Total Environment 2012, 440, 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Mutuku, C.; Gazdag, Z.; Melegh, S. Occurrence of Antibiotics and Bacterial Resistance Genes in Wastewater: Resistance Mechanisms and Antimicrobial Resistance Control Approaches. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2022, 38, 152. [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, T.; Wolfsperger, F. Water Losses During Technical Snow Production: Results From Field Experiments. Frontiers in Earth Science 2019, 7.

- Kim, S.H.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, G.E.; Jho, E.H. Effect of PH and Temperature on the Biodegradation of Oxytetracycline, Streptomycin, and Validamycin A in Soil. Applied Biological Chemistry 2023, 66, 63. [CrossRef]

- Loftin, K.A.; Adams, C.D.; Meyer, M.T.; Surampalli, R. Effects of Ionic Strength, Temperature, and PH on Degradation of Selected Antibiotics. Journal of environmental quality 2008, 37, 378–386. [CrossRef]

- Felis, E.; Kalka, J.; Sochacki, A.; Kowalska, K.; Bajkacz, S.; Harnisz, M.; Korzeniewska, E. Antimicrobial Pharmaceuticals in the Aquatic Environment - Occurrence and Environmental Implications. European Journal of Pharmacology 2020, 866, 172813. [CrossRef]

- Kümmerer, K. Antibiotics in the Aquatic Environment – A Review – Part II. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 435–441. [CrossRef]

- Cortes, L.G.; Marinov, D.; Sanseverino, I.; Cuenca, A.N.; Niegowska, M.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Lettieri, T. Selection of Substances for the 4th Watch List under the Water Framework Directive; 2020; ISBN 9789276194262.

- Arsand, J.B.; Hoff, R.B.; Jank, L.; Bussamara, R.; Dallegrave, A.; Bento, F.M.; Kmetzsch, L.; Falção, D.A.; do Carmo Ruaro Peralba, M.; de Araujo Gomes, A.; et al. Presence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Its Association with Antibiotic Occurrence in Dilúvio River in Southern Brazil. The Science of the total environment 2020, 738, 139781. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheng, W.; Xu, L.; Strong, P.J.; Chen, H. Antibiotic-Resistant Genes and Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the Effluent of Urban Residential Areas, Hospitals, and a Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant System. Environmental science and pollution research international 2015, 22, 4587–4596. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Chamorro, S.; Marti, E.; Huerta, B.; Gros, M.; Sànchez-Melsió, A.; Borrego, C.M.; Barceló, D.; Balcázar, J.L. Occurrence of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Hospital and Urban Wastewaters and Their Impact on the Receiving River. Water Research 2015, 69, 234–242. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.J.L.; Perez-Zabaleta, M.; Owusu-Agyeman, I.; Kumar, A.; Ghosh, A.; Polya, D.A.; Gooddy, D.C.; Cetecioglu, Z.; Richards, L.A. Discovery of Sulfonamide Resistance Genes in Deep Groundwater below Patna, India. Environmental Pollution 2024, 356, 124205. [CrossRef]

- Pazda, M.; Rybicka, M.; Stolte, S.; Piotr Bielawski, K.; Stepnowski, P.; Kumirska, J.; Wolecki, D.; Mulkiewicz, E. Identification of Selected Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Two Different Wastewater Treatment Plant Systems in Poland: A Preliminary Study. Molecules 2020, 25.

- Liu, H.; Zhou, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Their Association with Antibiotics in a Wastewater Treatment Plant: Process Distribution and Analysis. Water 2019, 11.

- Su, H.; Li, W.; Okumura, S.; Wei, Y.; Deng, Z.; Li, F. Transfer, Elimination and Accumulation of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Decentralized Household Wastewater Treatment Facility Treating Total Wastewater from Residential Complex. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 912, 169144. [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Cha, J.; Carlson, K.H.; Pruden, A. Response of Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARG) to Biological Treatment in Dairy Lagoon Water. Environmental science & technology 2007, 41, 5108–5113. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, E.; Zhang, K.; Gong, W.; Xia, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, G.; Xie, J. Water Treatment Effect, Microbial Community Structure, and Metabolic Characteristics in a Field-Scale Aquaculture Wastewater Treatment System. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 930. [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Liang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Y. Bacterial Community and Eutrophic Index Analysis of the East Lake. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex : 1987) 2019, 252, 682–688. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Mo, L.; Lek, S.; Chen, B.; Fu, Q.; Guo, Z. The Spatiotemporal Variations of Microbial Community in Relation to Water Quality in a Tropical Drinking Water Reservoir, Southmost China. Frontiers in microbiology 2024, 15, 1354784. [CrossRef]

- Bernardet, J.-F.; Nakagawa, Y.; Holmes, B.; Prokaryotes, S.O.T.T.O.F.A.C.-L.B.O.T.I.C.O.S.O. Proposed Minimal Standards for Describing New Taxa of the Family Flavobacteriaceae and Emended Description of the Family. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 2002, 52, 1049–1070. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.J.; Howington, J.P.; McFeters, G.A. Survival, Physiological Response and Recovery of Enteric Bacteria Exposed to a Polar Marine Environment. Applied and environmental microbiology 1994, 60, 2977–2984. [CrossRef]

- Gerber, E.; Bernard, R.; Castang, S.; Chabot, N.; Coze, F.; Dreux-Zigha, A.; Hauser, E.; Hivin, P.; Joseph, P.; Lazarelli, C.; et al. Deinococcus as New Chassis for Industrial Biotechnology: Biology, Physiology and Tools. Journal of applied microbiology 2015, 119, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Xiao, A.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, H.; Jiang, L. The Diversity and Commonalities of the Radiation-Resistance Mechanisms of Deinococcus and Its up-to-Date Applications. AMB Express 2019, 9, 138. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lu, W.; Ping, S.; Dai, Q.; Yuan, M.; Feng, B.; et al. IrrE, a Global Regulator of Extreme Radiation Resistance in Deinococcus Radiodurans, Enhances Salt Tolerance in Escherichia Coli and Brassica Napus. PloS one 2009, 4, e4422. [CrossRef]

- van Overbeek, L.; Duhamel, M.; Aanstoot, S.; van der Plas, C.L.; Nijhuis, E.; Poleij, L.; Russ, L.; van der Zouwen, P.; Andreo-Jimenez, B. Transmission of Escherichia Coli from Manure to Root Zones of Field-Grown Lettuce and Leek Plants. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Banach, J.L.; van Bokhorst-van de Veen, H.; van Overbeek, L.S.; van der Zouwen, P.S.; van der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Groot, M.N.N. The Efficacy of Chemical Sanitizers on the Reduction of Salmonella Typhimurium and Escherichia Coli Affected by Bacterial Cell History and Water Quality. Food Control 2017, 81, 137–146. [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.-M.; Lee, S.-W. The Plant-Associated Flavobacterium: A Hidden Helper for Improving Plant Health. The plant pathology journal 2024, 40, 251–260. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Aman, S.; Singh, B. Unveiling the Positive Impacts of the Genus Rhodococcus on Plant and Environmental Health. Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences 2024, 12, 557–572. [CrossRef]

- Huerta, B.; Marti, E.; Gros, M.; López, P.; Pompêo, M.; Armengol, J.; Barceló, D.; Balcázar, J.L.; Rodríguez-Mozaz, S.; Marcé, R. Exploring the Links between Antibiotic Occurrence, Antibiotic Resistance, and Bacterial Communities in Water Supply Reservoirs. The Science of the total environment 2013, 456–457, 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Cheng, W.; Huang, C.; Ren, J.; Wan, T.; Gao, K. Effects of Water Environmental Factors and Antibiotics on Bacterial Community in Urban Landscape Lakes. Aquatic Toxicology 2023, 265, 106740. [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Huang, Z.; Ohore, O.E.; Yang, J.; Peng, K.; Li, S.; Li, X. Impact of Antibiotics on Microbial Community in Aquatic Environment and Biodegradation Mechanism: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 66431–66444. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Te, S.H.; He, Y.; Gin, K.Y. The Effects of Antibiotics on Microbial Community Composition in an Estuary Reservoir during Spring and Summer Seasons. Water 2018, 10.

- Santos, R.G.; Hurtado, R.; Gomes, L.G.R.; Profeta, R.; Rifici, C.; Attili, A.R.; Spier, S.J.; Mazzullo, G.; Morais-Rodrigues, F.; Gomide, A.C.P.; et al. Complete Genome Analysis of Glutamicibacter Creatinolyticus from Mare Abscess and Comparative Genomics Provide Insight of Diversity and Adaptation for Glutamicibacter. Gene 2020, 741, 144566. [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.H.; Yoon, A.R.; Oh, H.E.; Park, Y.G. Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganism Pseudarthrobacter Sp. NIBRBAC000502770 Enhances the Growth and Flavonoid Content of Geum Aleppicum. Microorganisms 2022, 10.

- Issifu, M.; Songoro, E.K.; Onguso, J.; Ateka, E.M.; Ngumi, V.W. Potential of Pseudarthrobacter Chlorophenolicus BF2P4-5 as a Biofertilizer for the Growth Promotion of Tomato Plants. Bacteria 2022, 1, 191–206.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Antimicrobial Consumption in the EU / EEA ( ESAC-Net )- Annual Epidemiological Report 2020. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control 2021.

- European Medicines Agency; Agency, E.M. Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial Agents in 31 European Countries in 2019 and 2020 (EMA/294674/2019); 2021; ISBN 9789291550685.

- Lenart-Boroń, A.M.; Boroń, P.M.; Prajsnar, J.A.; Guzik, M.W.; Żelazny, M.S.; Pufelska, M.D.; Chmiel, M.J. COVID-19 Lockdown Shows How Much Natural Mountain Regions Are Affected by Heavy Tourism. The Science of the total environment 2022, 806, 151355. [CrossRef]

- Sáenz, Y.; Briñas, L.; Domínguez, E.; Ruiz, J.; Zarazaga, M.; Vila, J.; Torres, C. Mechanisms of Resistance in Multiple-Antibiotic-Resistant Escherichia Coli Strains of Human, Animal, and Food Origins. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2004, 48, 3996–4001. [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, M.; Hopkins, K.; Threlfall, E.J.; Clifton-Hadley, F.A.; Stallwood, A.D.; Davies, R.H.; Liebana, E. BlaCTX-M Genes in Clinical Salmonella Isolates Recovered from Humans in England and Wales from 1992 to 2003. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2005, 49, 1319–1322. [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Poeta, P.; Sáenz, Y.; Vinué, L.; Rojo-Bezares, B.; Jouini, A.; Zarazaga, M.; Rodrigues, J.; Torres, C. Detection of Escherichia Coli Harbouring Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases of the CTX-M, TEM and SHV Classes in Faecal Samples of Wild Animals in Portugal. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2006, 58, 1311–1312. [CrossRef]

- Bouallègue-Godet, O.; Ben Salem, Y.; Fabre, L.; Demartin, M.; Grimont, P.A.D.; Mzoughi, R.; Weill, F.-X. Nosocomial Outbreak Caused by Salmonella Enterica Serotype Livingstone Producing CTX-M-27 Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase in a Neonatal Unit in Sousse, Tunisia. Journal of clinical microbiology 2005, 43, 1037–1044. [CrossRef]

- Dallenne, C.; Da Costa, A.; Decré, D.; Favier, C.; Arlet, G. Development of a Set of Multiplex PCR Assays for the Detection of Genes Encoding Important Beta-Lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2010, 65, 490–495. [CrossRef]

- Cattoir, V.; Poirel, L.; Rotimi, V.; Soussy, C.-J.; Nordmann, P. Multiplex PCR for Detection of Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance Qnr Genes in ESBL-Producing Enterobacterial Isolates. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2007, 60, 394–397. [CrossRef]

- Geha, D.J.; Uhl, J.R.; Gustaferro, C.A.; Persing, D.H. Multiplex PCR for Identification of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococci in the Clinical Laboratory. Journal of clinical microbiology 1994, 32, 1768–1772. [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, J.; Grebe, T.; Tait-Kamradt, A.; Wondrack, L. Detection of Erythromycin-Resistant Determinants by PCR. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 1996, 40, 2562–2566. [CrossRef]

- Lina, G.; Quaglia, A.; Reverdy, M.E.; Leclercq, R.; Vandenesch, F.; Etienne, J. Distribution of Genes Encoding Resistance to Macrolides, Lincosamides, and Streptogramins among Staphylococci. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 1999, 43, 1062–1066. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F.; Ingenfeld, A.; Zampicolli, M.; Hilber-Bodmer, M.; Frey, J.E.; Duffy, B. Real-Time PCR Methods for Quantitative Monitoring of Streptomycin and Tetracycline Resistance Genes in Agricultural Ecosystems. Journal of microbiological methods 2011, 86, 150–155. [CrossRef]

- Szczepanowski, R.; Linke, B.; Krahn, I.; Gartemann, K.-H.; Gützkow, T.; Eichler, W.; Pühler, A.; Schlüter, A. Detection of 140 Clinically Relevant Antibiotic-Resistance Genes in the Plasmid Metagenome of Wastewater Treatment Plant Bacteria Showing Reduced Susceptibility to Selected Antibiotics. Microbiology 2009, 155, 2306–2319. [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, A.D.; Jenabi, A.; Montazeri, E.A. Distribution of Genes Encoding Resistance to Aminoglycoside Modifying Enzymes in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Strains. The Kaohsiung journal of medical sciences 2017, 33, 587–593. [CrossRef]

- Warsa, U.C.; Nonoyama, M.; Ida, T.; Okamoto, R.; Okubo, T.; Shimauchi, C.; Kuga, A.; Inoue, M. Detection of Tet(K) and Tet(M) in Staphylococcus Aureus of Asian Countries by the Polymerase Chain Reaction. The Journal of antibiotics 1996, 49, 1127–1132. [CrossRef]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of General 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene PCR Primers for Classical and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based Diversity Studies. Nucleic acids research 2013, 41, e1. [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; Wagner, H.; Barbour, M.; Bedward, M.; Bolker, B.; et al. Package ‘ Vegan .’ 2025.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016;

- Kolde, R. Package “Pheatmap”: Pretty Heatmaps. Version 1.0.12 2019, 1–8.

| Code | Height above sea level | number of inhabitants | Anthropogenic pressure description | Technical reservoir | sample description and code | E. coli | E. faecalis/ E. faecium | Salmonella | Coagulase-positive Staphylococci |

| [m a.s.l] | [yes/no] | CFU/100 ml | CFU/ml | ||||||

| BDF | 850 | 540 | upstream of a small village next to the Tatra National Park, upstream of wastewater discharge sites | yes | river water (BDF_W) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| storage reservoir (BDF_R) | 0 | 5 | 0 | 350 | |||||

| snowmelt water (BDF_S) | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| B3 | 760 | 950 | upstream of a small village next to the Tatra National Park and the Polish/Slovakian border | no | river water (B3_W) | 119 | 45 | 0 | 2 |

| snowmelt water (B3_S) | 0 | 26 | 0 | 2 | |||||

| B1 | 700 | 2,300 | center of a popular tourist resort, c.a. 3 km downstream of a WWTP | yes | river water (B1_W) | 186 | 94 | 0 | 0 |

| storage reservoir (B1_R) | 14 | 13 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| snowmelt water (B1_S) | 2 | 7 | 0 | 12 | |||||

| R | 315 | 17,500 | center of a medium-sized town, downstream of several ski resorts, c.a. 5 km downstream of a hospital, c.a. 10 km of a WWTP | no | river water (R_W) | 298 | 45 | 56 | 328 |

| snowmelt water (R_S) | 87 | 26 | 5 | 232 | |||||

| BDZ | 750 | 25,000 | center of a popular tourist resort, c.a. 3 km downstream of a WWTP, c.a. 2 km downstream of a hospital | no | river water (BDZ_W) | 224067 | 273641 | 10785 | 8667 |

| snowmelt water (BDZ_S) | 153 | 286 | 4 | 190 | |||||

| No. | Resistance mechanism | Gene | Primer | Sequence (5’-3’) | Annealing temp. (°C) | Product length (bp) | Reference |

| 1. | Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) | blaTEM | blaTEM-F | ATTCTTGAAGACGAAAGGGC ACGCTCAGTGGAACGAAAAC |

60 | 1150 | [46] |

| blaTEM-R | |||||||

| 2. | blaCTX-M | blaCTX-M-F | CGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA TTAGTGACCAGAATCAGCGG |

55 | 585 | [47] | |

| blaCTX-M-R | |||||||

| 3. | blaCTX-M3 | blaCTX-M3-F | GTTACAATGTGTGAGAAGCAG CCGTTTCCGCTATTACAAAC |

50 | 1049 | [48] | |

| blaCTX-M3-R | |||||||

| 4. | blaCTX-M9 | blaCTX-M9-F | GTGACAAAGAGAGTGCAACGG ATGATTCTCGCCGCTGAAGCC |

54 | 856 | [49] | |

| blaCTX-M9-R | |||||||

| 5. | blaSHV | blaSHV-F | CACTCAAGGATGTATTGTG TTAGCGTTGCCAGTGCTCG |

52 | 885 | [46] | |

| blaSHV-R | |||||||

| 6. | blaOXA-1 | blaOXA-1-F | ACACAATACATATCAACTTCGC AGTGTGTTTAGAATGGTGATC |

61 | 813 | [46] | |

| blaOXA-1-R | |||||||

| 7. | Carbapenemases class D | blaOXA-48 | blaOXA-48-F | GCTTGATCGCCCTCGATT GATTTGCTCCGTGGCCGAAA |

60 | 281 | [50] |

| blaOXA-48-R | |||||||

| 8. | Carbapenemases class A | blaKPC | blaKPC-F | TGTTGCTGAAGGAGTTGGGC ACGACGGCATAGTCATTTGC |

57 | 340 | [50] |

| blaKPC-R | |||||||

| 9. | Carbapenemases class B | blaIMP | blaIMP-F | TTGACACTCCATTTACAG GATCGAGAATTAAGCCACCC |

56 | 139 | [50] |

| blaIMP-R | |||||||

| 10. | blaVIM | blaVIM-F | GATGGTGTTTGGTCGCATA CGAATGCGCAGCACCAG |

60 | 390 | [50] | |

| blaVIM-R | |||||||

| 11. | blaNDM | blaNDM-F | GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC |

60 | 621 | [51] | |

| blaNDM-R | |||||||

| 12. | Methicillin-resistance | mecA | mecA-F | GTAGAAAATGACTGAACGTCCGATAA CCAATTCCACATTGTTTCGGTCTAA |

55 | 310 | [52] |

| mecA-R | |||||||

| 13. | Macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSb) resistance genes | ereA | ereA -F ereA -R |

AACACCCTGAACCCAAGGGACG CTTCACATCCGGATTCGCTCGA | 57 | 420 | [53] |

| 14. | ereB | ereB -F ereB -R |

AGAAATGGAGGTTCATACTTACCA CATATAATCATCACCAATGGCA |

52 | 546 | [53] | |

| 15. | ermA | ermA -F ermA -R |

TCTAAAAAGCATGTAAAAGAA CTTCGATAGTTTATTAATATTAGT |

52 | 645 | [53] | |

| 16. | ermB | ermB -F ermB -R |

GAAAAGGTACTCAACCAAATA AGTAACGGTACTTAAATTGTTTAC |

55 | 639 | [53] | |

| 17. | msrA | msrA -F msrA -R |

GGCACAATAAGAGTGTTTAAAGG AAGTTATATCATGAATAGATTGTCCTGTT |

50 | 940 | [54] | |

| 18. | msrB | msrB -F msrB -R |

TATGATATCCATAATAATTATCCAATC AAGTTATATCATGAATAGATTGTCCTGTT |

50 | 595 | [54] | |

| 19. | mphA | mphA -F mphA -R |

AACTGTACGCACTTGC GGTACTCTTCGTTACC |

50 | 837 | [53] | |

| 20. | lnuA | lnuA -F lnuA -R |

GGTGGCTGGGGGGTAGATGTATTAACTGG GCTTCTTTTGAAATACATGGTATTTTTCGATC |

57 | 323 | [54] | |

| 21. | vatA | vatA -F vatA -R |

CAATGACCATGGACCTGATC CTTCAGCATTTCGATATCTC |

52 | 619 | [54] | |

| 22. | vatB | vatB -F vatB -R |

CCCTGATCCAAATAGCATATATCC CTAAATCAGAGCTACAAAGT |

52 | 602 | [54] | |

| 23. | vga | vga -F vga -R |

CCAGAACTGCTATTAGCAGATGAA AAGTTCGTTTCTCTTTTCGACG |

54 | 470 | [54] | |

| 24. | vgb | vgb -F vgb -R |

ACTAACCAAGATACAGGACC TTATTGCTTGTCAGCCTTCC |

53 | 734 | [54] | |

| 25. | Streptomycin resistance | strA | strA -F strA -R |

TCAATCCCGACTTCTTACCG CACCATGGCAAACAACCATA |

52 | 126 | [55] |

| 26. | Trimetophrim resistance | dfrA12 | dfrA12 -F dfrA12 -R |

TTTATCTCGTTGCTGCGATG AGGCTTGCCGATAGACTCAA |

50 | 155 | [56] |

| 27. | Aminoglycoside resistance | aac(6')/ aph(2'') | aac(6')/ aph(2'') -F aac(6')/ aph(2'')-R | CAGAGCCTTGGGAAGATGAAG CCTCGTGTAATTCATGTTCTGGC |

55 | 348 | [57] |

| 28. | Tetracyclines resistance | tetK | tetK -F tetK -R |

TCGATAGGAACAGCAGTA CAGCAGATCCTACTCCTT |

55 | 169 | [58] |

| 29. |

Sulfonamides resistance |

sulIII | sulIII -F sulIII -R |

ACCACCGATAGTTTTTCCGA TGCCTTTTTCTTTTAAAGCC |

62 | 199 | [56] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).