Introduction: Process Heat, GHG Emissions, and the Climate Crisis

The Earth’s ecosystems have a natural carbon cycle by which carbon is constantly recycled. This natural carbon cycle moves large amounts of CO2 and, in the past, could maintain a near-steady state of CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere. This cycle permitted a certain annual predictability of weather and climate. However, emissions from human activities have increased. The totality of global CO2 production can no longer be fully recycled, leading to a net increase in atmospheric CO2 levels. Emissions have dramatically increased in the past seventy years [

1,

2,

3,

4,

29,

45,

65]. For 2024, the projected global carbon budget indicates that human-made CO2 emissions will significantly exceed the amount that can be absorbed in the carbon cycle. The tropospheric increase in CO2 concentration has led to rapid global warming and its unwelcome consequences. Accelerated warming increases the entropy generation rate in the troposphere, contributing to unpredictable severe weather. CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion are estimated at 37.4 billion metric tons in 2024, leading to a record high of approximately ~422 ppm in the troposphere. The rate of CO2 accumulation is related to the Earth’s average temperature and the entropy generation rate [

4,

19]. An increase in greenhouse gas concentration in the troposphere could have catastrophic consequences for humanity if the GHG emissions rate remains unchecked.

Combustion heating methods for power generation, industrial heating, and transportation account for over 75% of the pollutants and nearly 90% of all carbon dioxide emissions that drive global warming [

1,

65]. Almost 25% of all emissions, or about 11 billion tons per year of CO2, result from fossil fuel combustion in

industrial operations [

1,

86]. While the ocean and land plants may eventually absorb much of the carbon dioxide humans have introduced into the atmosphere, this process will take time. Despite the long-term potential for absorption, up to 20% or more of the excess carbon dioxide could linger in the atmosphere for thousands of years. There is thus an urgent need for immediate reductions in emissions. A decrease in concentration will be gradual, even with drastic cuts in CO2 emissions. Nevertheless, total levels can be stabilized through prompt actions that lower both the emissions rate and the rate of temperature rise. Eventually, the troposphere could return to a steady state, improving climate and weather predictability [

19]. The annual rate of rise of tropospheric CO2 exceeds the average for the past decade [

108], thus making it essential to examine all new technical ways of reducing such emissions. Industrial process heating is an area where CO2 emissions could be reduced substantially. This article examines such possibilities.

Process heat generation (thermal energy) is vital in industrial sectors such as transportation, aerospace, mineral drying and processing, metallurgical operations, electronics, power generation, turbine operation, and chemical production. This process heat is primarily produced by the exothermic combustion of fossil fuels, leading to significant GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions. The main fuel options include natural gas (CH4-methane) and C2H6-propane. When one mole (~17g) of natural gas (methane) is burned with oxygen gas (from the air) to release about 803.9 kJ of exothermic thermal energy, 64g of oxygen is consumed from the atmosphere, and approximately 44g of CO is emitted as a byproduct. In any industrial heater, even a simple exothermic reaction like burning natural gas requires ten times the amount of excess air to complete the chemical reaction, which makes energy inefficiency unavoidable with fossil fuel heaters [

1,

52,

65,

95]. The effects of these CO2 emissions on climate change are substantial. Avoiding fossil fuels and enhancing energy efficiency is critical for decarbonization, i.e., preventing carbon-containing GHG emissions.

In 2018, a total of 7,576 trillion kJ of fuel, steam, and electric energy were estimated to be consumed by U.S. manufacturers, comprising 51% of the total onsite energy used for manufacturing purposes [

1]. This represents a significant amount of non-electrical energy consumed directly at an industrial product manufacturer’s site, primarily for heating. Since all this energy use produces CO2 (i.e., local to a manufacturer), it results in highly dispersed emission sources, making it challenging to sequester emissions. Additionally, there is growing evidence that direct carbon capture from air is an expensive and, more importantly, highly energy-intensive technology [

48]. Worldwide emissions continue to rise. Although some countries like the United States have reduced their greenhouse gas emissions compared to their peak in 2007, the total global greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere continue to show a net increase [

98,

108].

This increase is partly due to rising industrial GHG emissions in the U.S. and globally, which is hindering meaningful changes in the rate of tropospheric CO2 accumulation. Recent 2024 reports [

83,

84,

85] demonstrate how energy efficiency, energy use timing for optimal energy rates, productivity, and efficiency are interrelated and influenced by process changes. Such reports underscore the need for energy-efficient electrification and process management at industrial sites. Eliminating flames and combustion heating will expedite decarbonization and reduce harmful emissions. Nevertheless, fossil fuel heating remains the dominant fuel choice in the industrial heating sector mainly because of its lower cost. The use of biofuels could be even more risky, as these fuels may replace other carbon-containing fuels while contributing to deforestation; reforestation cycles are lengthy, and deforestation is a complex disruption to many critical ecosystems. Moreover, biomass combustion leads to considerable haze and adverse effects on human health [

67,

68,

69,

108] and considerable CO2 emissions.

This article discusses the technical paths to decarbonization through the electrification of industrial heating and improving energy conversion efficiency. The focus is solely on the technical part of processes, including radical technical innovation in key market sectors that consume significant energy for delivering industrial process outcomes. The article consists of five sections: (1) Introduction (this section): Process heat, GHG emissions, and the climate crisis; (2) Technical trends in electrical heating; (3) Energy-efficiency related payback period for new electrical heaters; (4) Examples that illustrate the future role of radical innovation in meeting large power requirements and mitigating GHG emissions and (5) Summary and conclusions.

Environmental policies have significantly boosted innovation and adoption of cleaner technologies while discouraging dirty technologies. However, this article solely concentrates on technical trends and improvements for climate mitigation without directly addressing policy issues. Policies and regulations have fostered sustainable energy-related innovations that are more accessible to industries, contributing to the larger movement toward net-zero carbon emissions [

90]. Despite recent changes in the U.S., the global trend toward decarbonization appears to be progressing well. The motivation to tackle climate issues arises from government or policy-making bodies and organically from society, including citizen activists, climate engineers, and farming communities [

19]. While there is no doubt that green policies have improved climate and economic outcomes [

1,

4,

81,

85,

86,

90,

91], some reports suggest these policies may have led to unintended consequences [

92]. A brief overview of the primary drivers for technical innovations is presented first.

Transportation, power generation, and industrial heating are the three primary sectors responsible for nearly equal amounts of GHG emissions [

1,

2,

3,

29]. Among these three sectors, the electrification of industrial heating equipment will likely offer the fastest route to reducing global emissions. This is due to the significant advancements in efficiency and sustainable energy production that are now achievable [

1,

2,

3,

20,

34,

45,

52,

98]. Achieving stabilization of tropospheric GHG concentrations can only be accomplished through a large-scale reduction in the industrial use of fossil fuel combustion heating, including natural gas, propane, diesel, and gasoline. Large-power electrical industrial heaters are the most cost-effective solution for mitigating GHG emissions, as their costs typically range from US

$ 500 to

$1000 per kW of heating power, compared to

$2000 to

$5000 per kW for electric vehicles.

Energy-intensive industries encompass ore drying/calcination, general-purpose heat treating, cement, aluminum, steel, chemicals, fuels, and fertilizers, which rely on fossil fuel or flame-heating methods. There is significant interest in replacing CO2-emitting combustion fuels for thermal energy production with electrical heating methods. The goal of achieving 0% CO2 emissions from industrial processes and improving energy efficiency by at least 25% over fossil fuel heating methods for all electrical substitutions now is the quickest path to decarbonization.

Energy efficiency and energy productivity are interconnected. When energy productivity surpasses industry growth, energy requirements will decrease for various objectives, reducing total industrial energy-related GHG emissions [

31,

39,

72,

76,

82]

. High-temperature convection heating above 900°C and large megawatt electric heaters are essential to enabling technologies that present both technical challenges and commercial potential. Enhancing efficiency and productivity from an industrial heater may boost overall process efficiencies and productivity downstream, significantly improving GHG mitigation rates.

Estimates of the world’s asset losses from each kilogram of CO2 and methane emitted are astonishingly high, ranging from

$51 to over

$3,000 per kilogram of CO2 equivalent emitted [

1,

5,

16,

18,

21,

45]. The social drivers for providing heat (thermal energy) with clean electric heaters are becoming increasingly compelling due to the continuous rise in heat waves and climate extremes associated with greenhouse gas emissions. The global decarbonization market is estimated to be at least

$1.3 trillion and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 12.7% from 2021 to 2036. Some estimates suggest that the global market for decarbonized products and services will exceed

$40 trillion by 2040. Reducing or limiting CO2 emissions offers a promising and economically viable business opportunity, in addition to its role in mitigating climate change. This article examines the techno-economic aspects of advanced engineering principles in industrial heating.

On December 2, 2023, and updated later, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released a final report [

20,

45] that significantly raised estimates of the social cost of greenhouse gases (GHG), including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide (collectively referred to as SC-GHG). The report defines SC-GHG as “the monetary value of the net harm to society from emitting one metric ton of that GHG into the atmosphere in a given year” [

21,

45]. These estimates serve as a resource for decision-makers, assisting in the cost-benefit analysis of actions that reduce or increase GHG emissions. On March 6, 2024, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission introduced new climate disclosure rules, requiring companies to disclose climate-related risks that could materially affect their business or financial statements. New climate fines and taxes based on the amount of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere will go to

Climate Superfunds [

62]. Such fines are direct expenditures in project costs discussed in Sections 1 and 2 below. A process heater provides an essential industrial function and is a critical investment. A gamut of electrical heaters for industrial (process) heating requirements across a wide temperature range is shown in

Figure 1. One of the objectives of this article is to recognize the value of electrified thermal energy conversion machines and processes to manufacturers and society.

(2) Technical Trends and Energy Efficiencies in Electrical Heating and Waste Recovery Methods

Electrification Power Requirements for Industrial Heating-Process Sectors

While industry-specific needs may influence the types of improvements and new technologies relevant to different sectors, heating remains a universal requirement that is not confined to specific industry demands. On average, one million KJ of combustion energy from fossil fuel combustion results in approximately 60 kg of CO2 emissions (see

Table 1 for various fuels). Thus, transitioning to electric heating (see

Table 2) will benefit all industrial sectors by offering comparable energy efficiency enhancements and the ability to achieve near-zero GHG emission goals. A United Nations report [

65], among many others [

1,

52], explicitly emphasizes that converting fossil fuel-burning methods to electric heating is an essential global objective. The energy efficiencies of high-power electric heaters are explored in detail in various sections of this article. High-temperature electric heat can be applied across numerous industrial applications, delivering significant advantages such as reduced emissions, improved efficiency, and outstanding durability of critical heater components. The role of waste heat recovery is also discussed in detail below for energy reuse, considering both the work-energy transfer and the recyclability of thermal energy (heat energy transfer) from waste heat. This article does not consider heat pumps as their exit temperature output typically does not exceed comfort-heating temperatures (generally lower than ~27°C (300K)). Growing evidence also indicates that a heat pump’s very high predicted efficiencies are unrealistic [

99,

100], and a heat pump’s impact on the electrical grid is more complex than conventional heating systems. In contrast, electrical industrial heaters are typically used for temperatures between 100°C (373K) and 1800°C (3272K) with predictable efficiency and grid impact (

Table 2). Most heavy-industrial heating processes consume considerable power and operate with heater exit temperatures between 200°C (food sector) and 1200°C (industrial calcining and sintering) sectors. This includes the steam and process gas heating requirements. This market is currently heavily dominated by fossil fuel heaters. Beyond 1200°C to about 230°0C, the market is smaller, addressing melting, heat treating, and sintering metallurgical operations with radiative heating. It uses more electric heating than the lower and mid-temperature range sectors.

Figure 1 illustrates the significant application of industrial heaters across various sectors, where reducing CO2 emissions and promoting sustainable development alongside enhanced industrial practices is feasible. These sectors include iron and steel, glass, cement, aluminum, polymers, stucco, and mineral processing, encompassing activities from drying to calcining. Additionally, key sectors where significant industrial heat is utilized encompass (a) power plants, where high-temperature heat is essential for steam turbine operations; (b) chemical production, including energy generation from wood chips, where high-temperature heat facilitates chemical reactions; (c) mineral processing, where high-temperature heat is crucial for drying, extracting valuable minerals, and refining raw materials; (d) food processing, which relies on high-temperature heat in bakeries, dairy operations, and other food sanitation industries; and (e) metalworking, where high-temperature heat is critical for melting, casting, and shaping metals.

Electrifying industrial heating processes includes the use of electric process-gas heaters, high-temperature industrial furnaces, steam boilers, many shown in

Figure 1. While advancements in battery technology, particularly MW batteries, are vital for decarbonization, this article does not address battery development. Life optimization, compactness, and scalability of single-stage electric heaters to the 50 MW range and beyond, along with optimized auxiliary equipment [

38,

75,

76], as well as the scalability of electric heaters to the 100 MW power range with enhanced auxiliary equipment such as fans, blowers, and pumps [

38,

75,

76], are active areas of research. For context, 100 MW equals about 5000 to 10,000 average-sized electric vehicles. Large-scale MW installations may, therefore, have the quickest impact on decarbonization, whether for low-temperature centrally produced heat for entire communities or large-scale high-temperature industrial processes [

23,

27].

Several countries have set ambitious goals for reducing emissions [

12]. This will necessitate substantial new capacity for electrification. These targets, while challenging, are achievable within context. The U.S. has set climate goals to cut greenhouse gas emissions below 2005 levels by 2030, marking a move toward a sustainable future [

66]. For example, assuming the U.S. accounts for approximately 13-15% of global industrial emissions, only a relatively small segment of U.S. industrial methods needs to be electrified to mitigate the CO2 issue [

83,

84,

85] significantly. A 50% reduction in emissions is widely recognized as a target [

66], which will require optimizing existing electrification capacity or adding new capacity. In 2023, capacity additions in the U.S. (35.8 GW) surpassed retirements (15.7 GW), with around 65% of the retired capacity coming from coal-fired facilities [

46,

47]. Although this is a positive development, the pace of change still falls short of the required conversion rate to achieve the 50% reduction in GHGs. Several adjustments must be made to electric distribution and optimize or synchronize available power capacity with the use time. The development of electric and thermal batteries will undoubtedly become crucial. Regardless, the electrification of industrial heating methods with energy efficiencies possible from electric heating methods could be a vastly financially attractive proposition, as shown in Section 3 of this article.

Efficiency

Thermodynamic efficiencies vary across different industrial process heaters and technologies. Measuring the exergy loss and assigning a value to it for any process is one way to quantify its efficiency when a work (chemical process) objective is foremost (6). However, it is often adequate for ROI (Return on Investment) calculations to consider only the energy or enthalpy balances when the objective of the process is heating (temperature increase as opposed to work creation).

Energy conversion efficiency plays a crucial role in considering ROI scenarios. The energy efficiency (η) in this article is defined as [1- (energy input—useful energy output) / energy input)]. The efficiency of electrical heater systems reflects the socket power draw in relation to the output’s thermal objectives. For fossil-fuel heater systems, it represents the enthalpy supplied plus the combustion enthalpy released relative to the usable enthalpy after accounting for radiation and conduction losses and flue gas losses.

The overall efficiency of the process depends on the efficiencies of the individual sections. When analyzing a system with multiple components, the overall efficiency reflects the cumulative effect of each component’s efficiency; the combined effectiveness of each stage directly influences the total output of the system. Essentially, the efficiency of each stage acts as a multiplier for the output of the next stage, leading to a final overall efficiency that represents the entire system’s performance. Heaters often require auxiliary control systems that can significantly affect the heater’s overall efficiency. For example, in a fossil-fuel heater, the overall efficiency ηoverall = ηburner’ηauillliary-equipment·ηthermal·ηdischarge.ηheat-exchanger. For example, several semiconductor devices called SCRs (Silicon Controlled Rectifiers) and VFDs (Variable Frequency Drives) regulate the power and output in modern automated heaters. The main objective of such controls is to enhance life and assist proportional controls; regenerative and modular SCRs and VFDs offer enhanced efficiency and adaptability and may also cut down the panel wiring by sharing circuitry. Such equipment also optimizes the performance of blowers and pumps. In fluid-based systems, the power demand is proportional to the cube of the motor’s speed. Even small reductions in speed result in significant energy savings.

Trends in Heater Materials

The technical trends in developing materials for industrial processes [

1] are focused on improved materials for longer life and use at higher temperatures (>2000K) in specific gas environments like carbonaceous or other reducing gases. High-temperature materials for hydrogen heating and their use in novel air propulsion systems or green steel production are active research areas worldwide.

There are well-recognized limitations of high-temperature materials that can withstand higher temperatures in oxidative, reducing, and erosive atmospheres [

72]. The key limitations of developing high-temperature heaters are like those required for jet engines and related blade and vane materials when oxidation and erosion resistance are essential [

50]. Almost always, the life of an industrial heater is limited by the life of its critical high-temperature components, e.g., the heating element. Consequently, life improvements that impact durability directly influence the payback periods discussed in Section 3. In the waste-heat reutilization section below, typical examples demonstrate the importance of operating at high temperatures to achieve high efficiencies. Artificial intelligence techniques could enhance refractory formulations because insulation (refractory) materials are usually multi-elemental and consist of various crystal structures and grain morphologies.

Acceptable heating materials (compositions) have upper-temperature limits of approximately 2000K in oxidative atmospheres and about 2300K in reducing environments (see

Table 2). The higher the temperature, the faster the kinetics of a chemical or metallurgical process can occur. A heater’s effective productivity, measured as parts made per unit time, is logarithmically related to its temperature capability [

24,

26,

27,

83,

84,

85].

Table 2 lists the commonly used heating materials. All the heating elements shown in this Table enable the formation of highly impermeable oxide layers of Cr2O3, SiO2, or Al2O3, depending on the heater material. Therefore, nano-coatings for high heater material emissivity and erosive or oxidative life represent a key area of trending patents and research [

73,

77].

Trends in Sustainable Process Optimization and Water Savings

Process optimization involves electrification, the development of efficient ancillary equipment, flexible heater placement, and automation to enhance productivity. An example of ancillary equipment is blowers for convective heaters. The energy used by blowers (process fluid movers) is directly on the pressure needed for the gas flow (such as air or hydrogen) to be heated by passing it through an array of heating elements. The pressure drop can be significant in traditional electrical heaters or indirect heat exchanger systems. A high-pressure drop requirement necessitates using costly multistage blowers that can consume much energy for a given flow rate. Newer electric heating processes use direct gas heating methods, with pressure drops of less than ~10 kPa required for a gas flow of ~300 tons of air per hour, i.e., for large 10MW process gas heating devices.

Process optimization through integrated digital electronic controls and IoT technologies is currently a trending goal for remote monitoring and Environmental and Governance (EG) reporting requirements. This approach enables companies to communicate their EG practices to stakeholders and emission monitoring agencies. Digitization has increased energy consumption for information processing and frictionless improved process control, which is particularly feasible with electrical heating methods. The overall impact of digitization on energy usage and climate effects remains unclear. However, new process controls and EG reporting would not be feasible without digitization. This serves as a means for companies and users to demonstrate their commitment to sustainable business practices and environmental responsibility.

A direct consequence of electrification for steam generators replacing traditional fossil fuel-heated pressure boilers is that the heat-up and cool-down times are very rapid (minutes vs. hours). This feature, along with the higher steam temperatures available, has allowed for new processes for antimicrobial steam with sterilization-level efficacy and process steam productivity benefits [

106,

107]. The energy efficiency leads to water savings, as discussed in Section 3.

Waste Heat Utilization

Along with materials and process improvement trends, many technical improvements are directed towards energy efficiency improvements by recirculating the heated waste gas to recover energy e.g., flue gas waste energy - also called retrofit technology for waste heat utilization. Recycling is difficult for gas outputs from fossil fuel heater-enabled systems because the exhaust gases are no longer the original gas after the combustion process that generates the heat. Methane CH4 (natural gas) becomes CO2, H2O, and NOx, mixed with particulates (soot) after a combustion event, thus immediately losing the exergy (work potential) of the input gas and making it unsuitable for direct recirculation. However, it can still be used to heat the incoming air. The overall efficiencies of various standard heating systems are shown in

Table 3, discussed below. Section 3 provides numerical estimates of recycling-enhanced efficiencies.

Waste heat recovery involves capturing and utilizing at least the thermal energy that would otherwise be discarded during industrial operations. To achieve energy benefits, several methods and technologies are commonly considered, e.g., (a) combining heat sources and sinks within a facility to maximize heat utilization and minimize waste; (b) using heat exchangers where heat is transferred from one medium to another via a physical barrier, allowing the heat to be utilized elsewhere, (c) utilizing an organic fluid with a lower boiling point to turn waste heat into electrical power, (d) thermoelectric generation, i.e., directly converting heat into electricity using thermocouples or solid-state thermoelectric materials (e) transforming low-quality waste heat into mechanical motion or electricity with shape-memory alloys, (f) capturing waste heat to drive steam turbines and generate electricity, (g) preheating boiler feed water using waste heat to increase boiler efficiency and reduce fuel consumption, and (h) hydronic heating discussed in Section 3 of this article.

Economically feasible power augmentation from waste heat has been limited primarily to medium- to high-temperature waste heat sources (i.e., where the waste heat temperature is higher than 230°C). Lower-temperature waste heat streams (below 100°C) are generally not practical or economical to recover. Regardless, waste heat reclamation and recycling are practiced today wherever they can provide additional energy efficiency. Research on economies of scale and process improvement efficiency by retrofits/recycling-related energy efficiencies is widespread.

Waste heat is recovered as thermal energy or work. Batteries, both electrical and thermal, are helpful in these processes. Thermal batteries are used for thermal waste heat storage from recovered waste heat. Thermal batteries store energy at a high temperature. The discharge is at a lower temperature. The use, for example, could be in building heat or medium temperature polymer or aluminum processing.

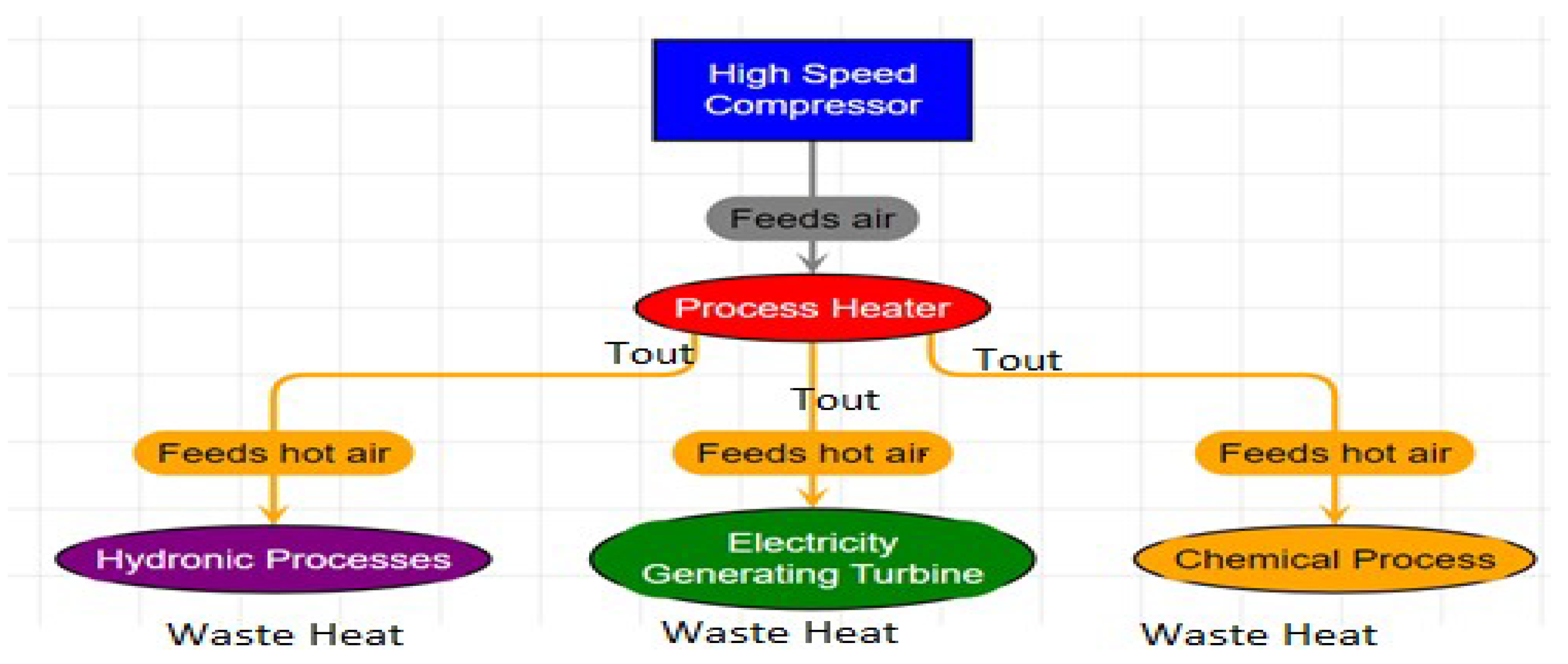

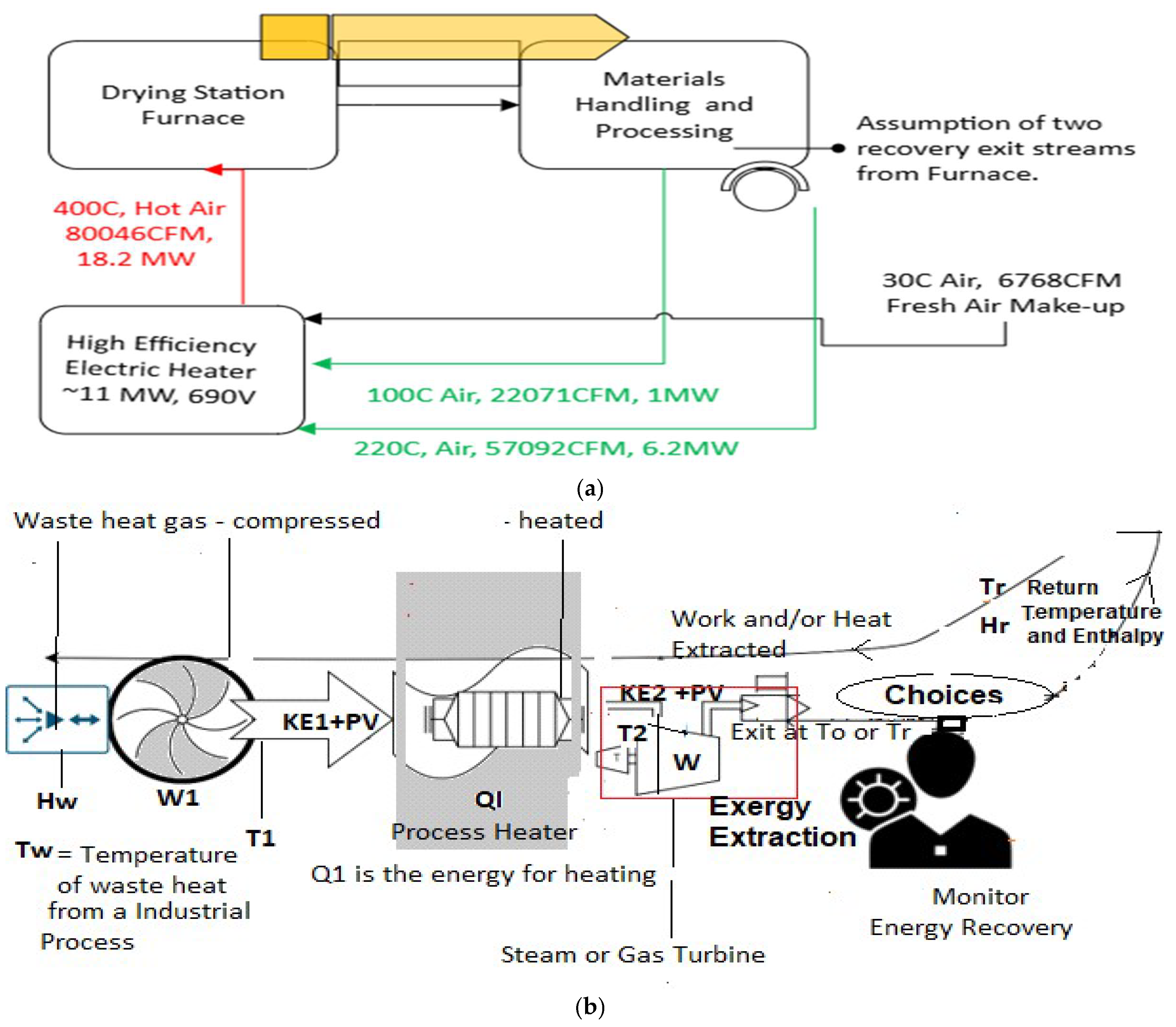

Figure 2 (b) shows a diagram for waste heat-to-work recovery. Electric batteries (that store electric charge or potential) store work in the form of chemical energy discharging again as work (electricity). A re-imagination of the cycle shown in

Figure 2(a) indicates the nature of a thermal battery operation even without a physical thermal battery if the process is continuous. The diagram in

Figure 2(b) shows a schematic for reheating low-temperature waste gas heat and recovering the waste energy in the form of work. Here, the reclaiming work from waste heat is subject to Carnot efficiency limits. An example would be where the waste heat is captured for power lighting, or for room heating with a heat pump, or even for heavy industrial use (

Figure 2(b)).

Efficient reheating or waste recycling is a complicated undertaking for fossil-fueled heating systems. Typically, gas heaters require ten times the amount of stoichiometric air [

52] to enable a complete burn of the hydrocarbon fuel. The exothermic heat release heats this excess air and becomes a part of the flue gas loss. A gas heater’s overall efficiency (η

overall) will comprise the efficiency of various stages of the burner device. Regardless, a few currently used systems capture some waste flue-gas energy. Typically, reheating the incoming combustion air with exhaust (flue gas) can add only about η

burner ~5% to the fossil-fired heater efficiencies [

11,

13,

14,

52]. The overall efficiency gained by reheating incoming air with exhaust air is limited. For example, the overall efficiency,

ηoverall = ηburner·ηthermal·ηdischarge.ηheat-exchanger can be a low

0.7x0.7x0.85x0.6 = 0.25 (25%) [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Note that a 5% increase in burner efficiency with waste heat recycling would not significantly improve overall efficiency. It would increase the overall efficiency to 26.25% from the original 25%, i.e., only an improvement of

1.05%.

Reheating can also be performed for existing electrical systems to lower overall energy use with a closed or near-closed loop system similar to that shown in

Figure 2(a). Here, the gains are meaningful.

Figure 2 (a) shows a typical reheating for a drying operation of powders. In such operations, the efficiency of about 95% is maintained for the heater, and recycling of waste gases can be carried out if it is unchanged in composition. Thus, recycling can save additional power by reclaiming the energy lost from the furnace and materials handling operations. This dramatically enhances overall efficiency. The efficiency without reheating would have been

ηoverall = ηheater.ηfurnace = 0.95 x~0.75 = 0.71 (71%). With the reclamation of waste heat by a reintroduced stream (green lines in

Figure 2(a)), the furnace part of the efficiency may be enhanced to 0.95, making the overall efficiency equal ~

0.90 (90%). An improvement of

19%.

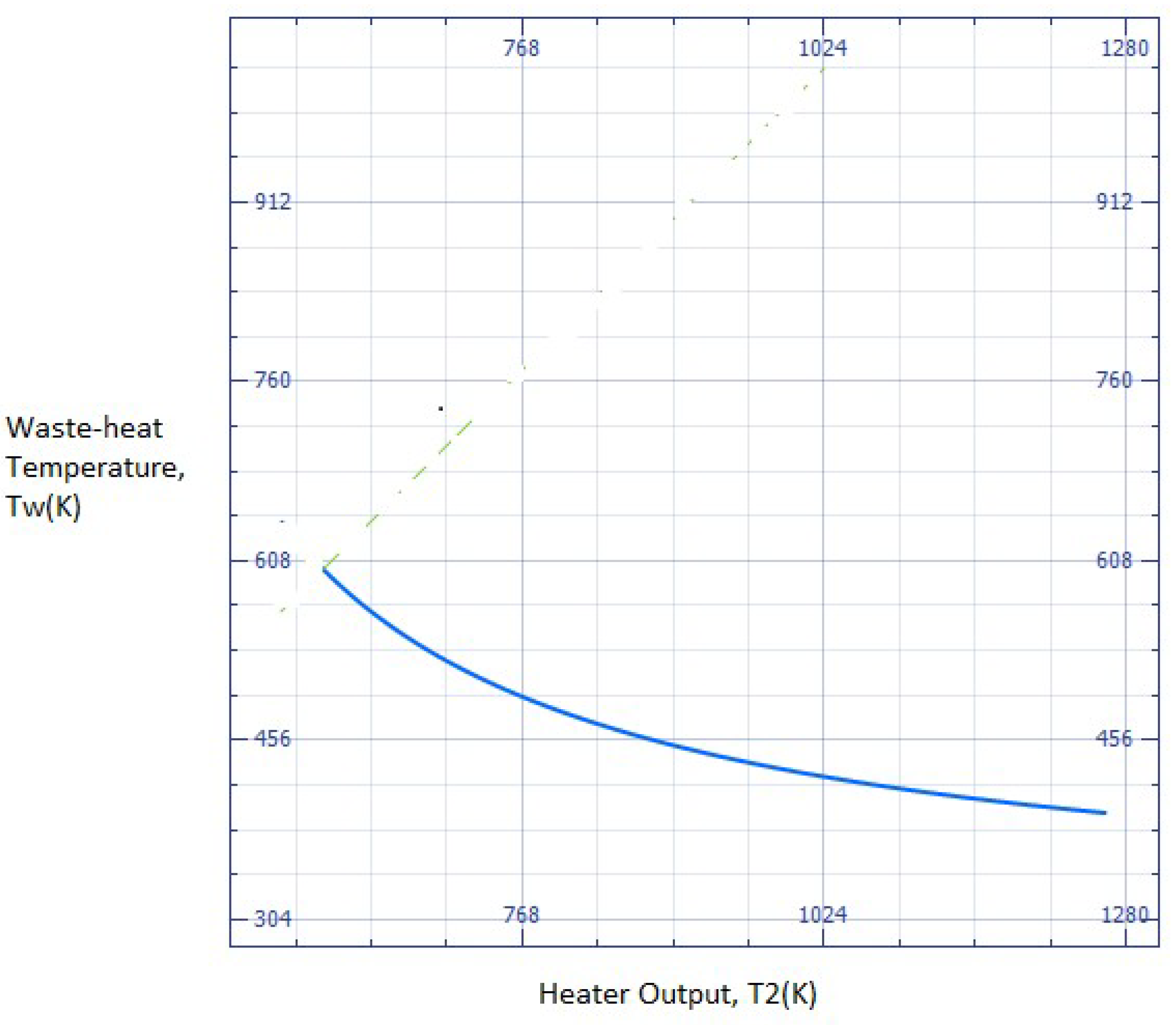

The energy balance for

Figure 2 (b) yields a condition for relating the minimum T2 (K) temperature required to a particular available Tw(K) temperature. A complete energy reuse is possible if a To temperature less than Tw (K) is available. The waste heat has an enthalpy of Hw (kJ/kg) and a temperature of Tw (see symbols definition below). Assume the mass transfer rate is dm/dt, and the specific heat is Cp. The energy entering the turbine in

Figure 2(b) is (Hw + W1+ Q1) ~ m.Cp.(T2-To), but the excess energy added is only m.Cp.(T2-Tw), the rest coming from waste energy. Equation 1, plotted in

Figure 3, shows the minimum heater T2 temperature where the extracted work exceeds the energy input, as discussed below (this is possible because waste heat contains energy above the outside temperature). If a Carnot efficiency device is available, then in principle, the waste heat can be utilized fully at low T2 – for lower work efficiencies, the T2 will correspondingly increase. The Carnot efficiency case is analyzed below, and the minimum heater exit temperature is shown in

Figure 3 for any available waste heat temperature that must be efficiently converted to work. The energy out is W + (Hr + H

use) ~ m.Cp.(T2-To). The H

use can be employed in a chemical or hydronic application for waste heat reclamation. The assumptions made to obtain the T2 temperature as a function of the waste heat temperature are below. It should be noted that these assumptions have low influence when the waste heat recovery system operates at high powers, i.e., above 500 kW (i.e., 500 KJ/s of waste heat recovery, typically above about ~700SCFM or ~110Nm

3/hr. airflow recovery rates) (a)

Q1>> W1 (almost always the case for high KW and MW process heaters), (b)

Tw approximates T1, and (c) Hr is the enthalpy at Tr, i.e., after H

use has been deployed. The work output is m.Cp.(T2-To). (1- To/T2) and the rest of the thermal energy is discharged to To (a reservoir). The ratio of energy input to the energy obtained by work yields the condition of a minimum heating temperature for complete waste heat recovery by work (electricity) as:

The following symbols are used for energy and enthalpy balances to illustrate work-based waste-heat utilization (Equation (1)).

Cp (kJ/kg.K): is the specific heat at constant pressure.

Hw (kJ/kg): is the Enthalpy of waste heat. The waste heat is at a temperature of Tw (K)

H

use (kJ/kg): Enthalpy used in the hydronic plus chemical process use (see

Figure 5)

Hr (kJ/kg) is the waste heat released after the generator output is used hydronically. This heat is returned from the hydronic process at a temperature Tr and can be recycled at a lower temperature Tw.

KE (kJ/kg): is the kinetic energy, and P and V are the pressure and volume, respectively.

KE1 (kJ/kg): The blower/compressor imparted kinetic energy.

M (kg): is the mass, and dm/dt (kg/s) is the mass flow rate

Q1 (kJ/kg): Energy is added to raise the temperature from T1(K) to T2 (K), the heater outlet.

To or Ta (K): is the lowest ambient temperature available. (Assumed to be 300K in the example below)

T1 (K): is the temperature of air/gas that exits the compressor.

T2 (K) is the process heater’s exit temperature, which is also approximated as the turbine inlet temperature.

W (kJ/kg): is the work output from the turbine.

W1 (kJ/kg): Work to isothermally pressurize and provide kinetic energy by the Compressor. This is equal to the kinetic energy and PV energy (KE1+PV).

q = Carnot efficiency of the Turbine =(1-T0/T2)

l = Energy or Enthalpy recovery from waste heat for direct heating.

Hr and Huse are zero for Carnot efficiencies between T2 and To as the turbine discharges to To, in this case. Equation 1 thus assumes none of the energy is used for down-process heating, i.e., l = 0, and all energy recovery is in the form of work. Should heat be required for downstream processes, it is simple to modify Equation (1) accordingly with a thermal term that will modify the numerator in Equation 1. The main conclusion from the analysis of heat processes for recycling, namely Figure (2b) and similar work processes, is that a high heater temperature is required as the waste heat temperature becomes closer to To. This is why several devices like heat pumps have been perfected for low-temperature use, where work is input into the system to move the fluid, not to heat it.

Of course, the main drawback of utilizing any waste heat in the form of electrical or thermal energy-conserving method lies in the fact that there are no readily available Carnot-efficiency devices (i.e., the theoretically most efficient turbines) or invariably high-temperature recirculation associated with thermal losses. Advanced developments for better and safer refractory materials without containing harmful fibers (FiberFree

®)

1 are expected to become a technical research trend for materials.

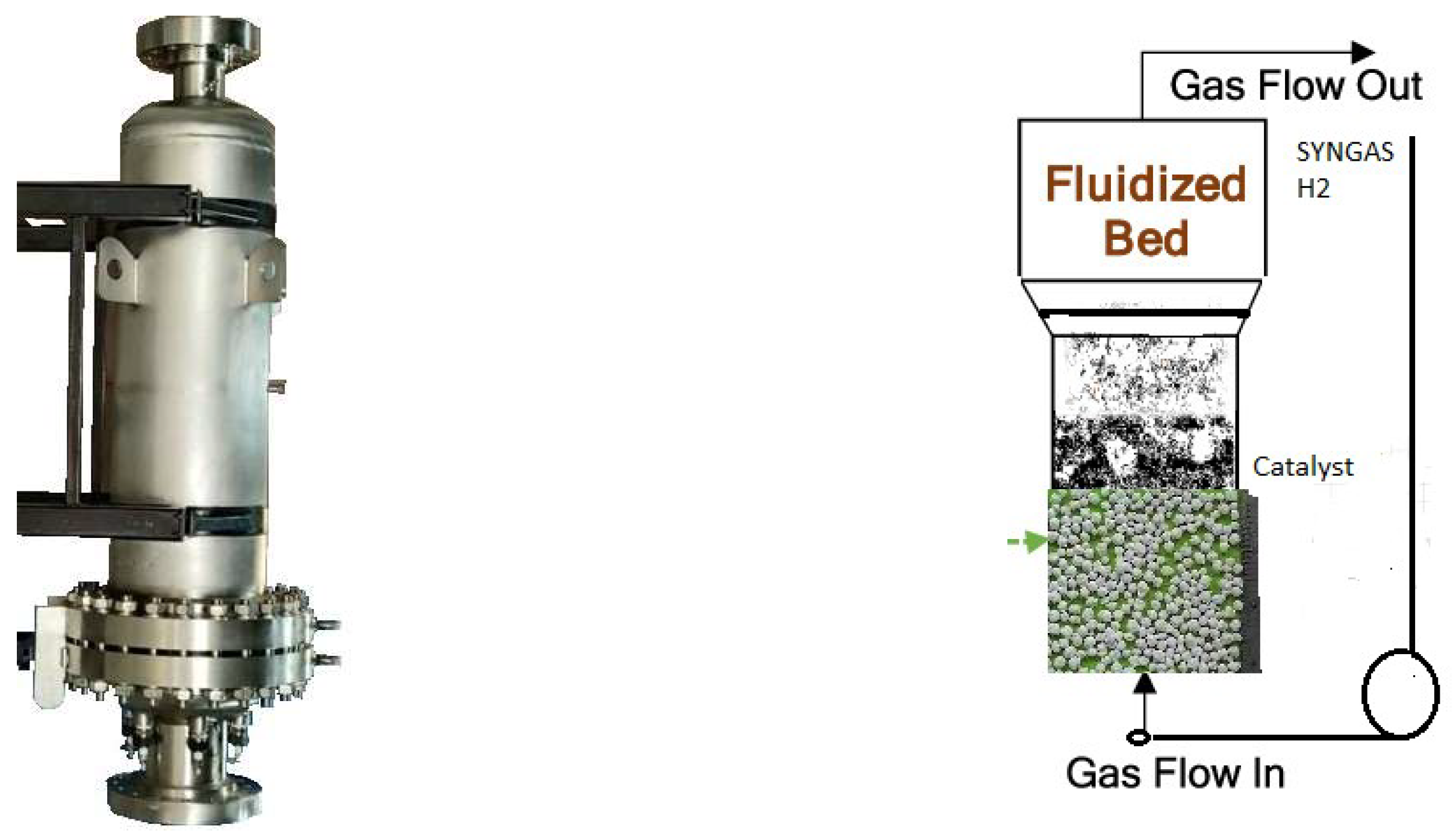

Electric Heating for Sustainability-Driven Methods for Performance Chemicals and Fuels (hybrid methods):

Considerable heating is required even for fossil fuel production. When heating naphtha and other fuels for reaction or decomposition, the primary heating method is through heat exchangers [

95], often using a hot utility like steam. This raises the temperature of the fuel to the desired level for processing or combustion by utilizing its relatively low boiling point to efficiently transfer heat and ensure proper viscosity for handling and atomization in the next stage of the process. This is particularly important in refineries where naphtha is a key component of gasoline production. Several electrically heated direct hot gas heating methods and new materials that prevent coking are under development. Eliminating indirect heating considerably improves the energy efficiency. With indirect heating methods (heat exchangers), layers of coke may deposit on the surface walls, thus further reducing the efficiency of energy transfer. In contrast, precise temperature control is possible with electric heating and avoids overheating or excessive vaporization that may otherwise occur. Even creating syngas (a mixture of H2 and CO, both reducing gases) or green-hydrogen while eliminating CO2 is now efficient and possible with material or plasma catalysts when used with direct electrically heated gas (that runs through fluidized or particle beds in a heater gas state or ionized state).

Syngas (synthesis gas) is a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide in various ratios where electrically heated hydrogen or plasma-dissociated CO2 or steam is employed, depending on the type of reaction. Electrically heated hydrogen, or sometimes high-temperature carbon monoxide, is often used as an ore reduction fuel [

95,

97]. Such gases may contain some carbon dioxide and methane. Alcohol and its derivatives are regularly produced with a two-step industrial process for catalytic hydrogenation of syngas into methanol (CO/CO

2 + 3H

2 → CH3OH + H2O). Subsequent catalytic dehydration of the methanol over catalysts can produce DME (2CH3OH → CH3OCH3 + H2O), which is often considered an alternative to diesel fuel. Multi-functional catalysts can be used in scalable electrically heated reactors. An illustration is shown in

Figure 4.

Payback Calculation for Investments in Heaters

The capital costs and payback periods of investments are discussed in this section. Higher energy-efficient devices are more expensive but could offer a significantly better long-term return. The overall energy efficiency of fossil fuel heaters, depending on their deployment, ranges from 30% to 85% [

7,

8,

9,

10,

70]. Such heaters invariably emit greenhouse gases (GHGs), regardless of the burner’s efficiency. As mentioned, GHGs are linked to significant global asset losses [

16,

21,

22,

45]. However, these costs are shouldered by societal groups [

4,

16,

17,

18,

45], not solely by the industrial units that produce them. For instance, some island nations suffer the consequences of rising sea levels even though they are not responsible for GHG emissions. Regardless, there are various reasons for selecting fossil fuels or electric methods unrelated to climate pollution or energy efficiency. In countries like the US, fossil fuels like natural gas are typically inexpensive for consumers today, although this may change. In countries like Finland, the fossil fuel supply may not be secure, and electric methods are preferred because of climate change and national security. Fossil fuel heaters (that use low-exergy fuels) generally cost less than high-exergy heaters (e.g., electric heaters) for the initial capital expenditure. However, considering only the initial cost may not be the best financial decision, as the poor efficiency of low-cost, low-efficiency heaters (see

Table 3) could compromise the payback.

As discussed in other parts of this article, for any fossil fuel gas heater, there will always be a flue gas output and excess air that limits energy efficiency, the primary cause of the heating inefficiency.

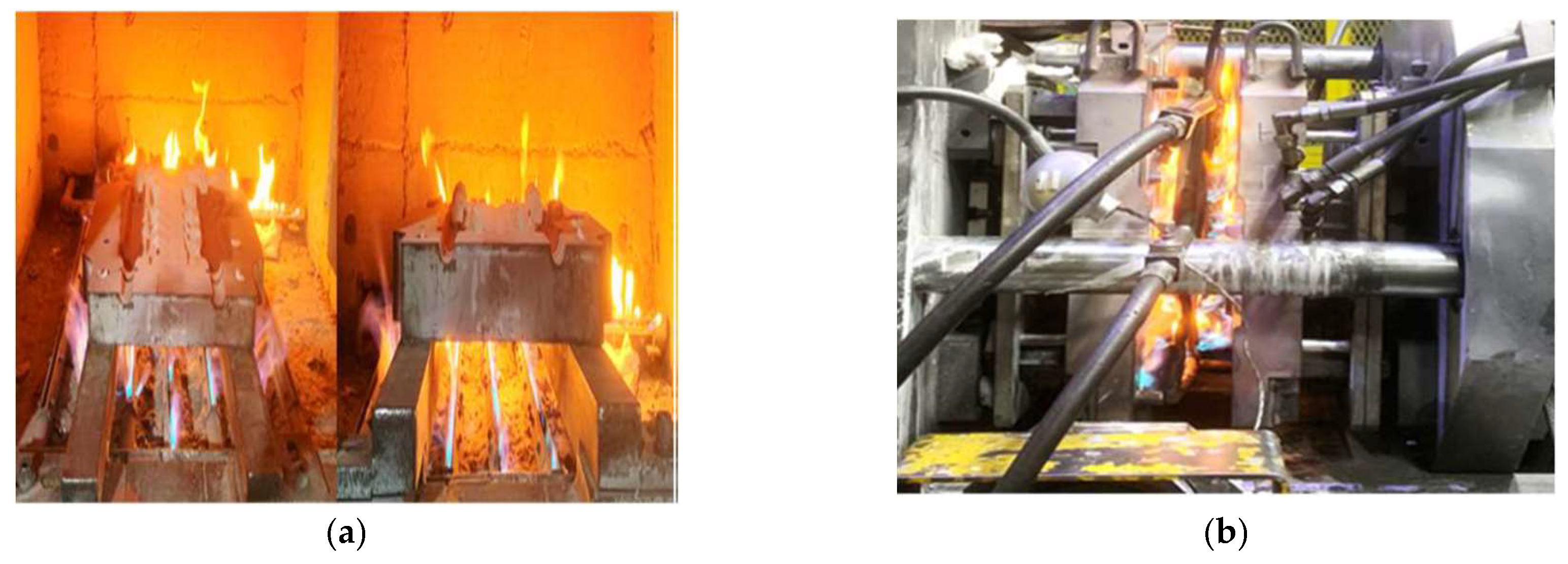

Figure 5 (a) and (b) show a fossil fuel-fired die-heating operation. This open flame condition could be typical of fossil fuel heaters, adding safety concerns to the calculations presented below. Considerable energy (heat) is wasted in such a process through radiation and with the emitted flue gas that carries waste energy with it. Besides efficiency improvements, electric heaters eliminate emissions of CO2 and CO2eq gases such as CH4, SO2, Nox, and particulate emissions. Should climate pollution by GHGs be taxed by society, such taxation disincentive would be another way to justify using electric heaters [

4,

17,

18,

45,

71]. The energy efficiency of a process is a key measure in choosing an economical heater system. First, a few straightforward examples highlighting the importance of efficiency gains with financial calculations for process gas heaters are discussed.

In aluminum, smelting and refining furnaces are powered by direct fossil fuel heating; the current efficiency of ~13% can increase to over 95% with electric heating. A 1MW electric system will prevent 0.25-0.6 tons of CO2 per hour from being emitted if it replaces a fossil fuel heater. Replacing a 5 MW burner (typical burner size in aluminum melting) with a 1.2 MW Electric heater will save 76% of energy [

14,

15]. Even if electric energy is 1.5X (multiplier) the price of equivalent fossil energy, there are approximately 3 times the savings in energy costs per year with the conversion. Because of their efficiency and climate mitigation potential, efficient electric heaters have become a part of all new process development (such as hot hydrogen) technologies. Electric resistance heaters (

Table 2 and

Table 3) offer the best overall efficiencies, generally exceeding 95% for well-built and properly managed processes.

The overall efficiency of an electrical induction heating method [

17] can be determined by multiplying the efficiency (η) of various stages that comprise the heating process (supply, thermal, and coil). The overall efficiency η

overall = η

supply·η

thermal·η

coil. Here, η

supply accounts for losses in cables, power factor correction capacitors, and frequency conversion equipment; the thermal efficiency, η

thermal represents thermal losses from the workpiece, which is critically dependent on operating temperature, quality of thermal insulation, and method of operation of the heater and η

coil is the coil efficiency that depends on the AC frequency, induction coupling, magnetic susceptibility and the ratio of the perimeter of the coil to the substrate. Even if all of these were 0.9 (90% efficient), the overall efficiency could not exceed 0.729 (72.9%).

Similarly, a gas heater’s overall efficiency (ηoverall) will comprise several terms. It can only be determined by multiplying the efficiency of various stages, namely, ηburner·ηthermal·ηdischarge.ηheat-exchanger. Here, the ηburner is the combustion burner efficiency that depends on excess air, burner construction, adequate containment, burner radiation losses, burner quality of combustion, and the humidity of the oxidant gas. The ηthermal captures radiation and other heat losses from the furnace chamber, not including the flue gas losses, ηdischarge is a range of loss processes that could contain terms that include the enthalpy loss in the combusted air (including flue gas losses), ηheat-exchanger is the efficiency of the heat exchanger for indirect heating (a practice that is followed when the combustion gases cannot be allowed to encounter the chemicals being heated or dried directly or cannot be allowed to pollute the plant). Even if these were 0.9 (90% efficient) individually, the overall efficiency could not exceed 0.65 (65%). As Section 2 Part (iv) discussed, heat-exchanger efficiencies are rarely that high. They could be more like 50%, placing the overall efficiency closer to a low 40% for gas (fossil fuel) heating systems.

Figure 5 shows commonly experienced open radiation and gas discharge that typical fossil fuel heaters display. Such open flame heaters are not unusual to deploy when only the capital price is considered, and clear calculations have not been made as to the long-term financial paybacks, climate pollution, or safety concerns.

Figure 6 shows a flow diagram for a more controlled electrically heated process gas heater that could be used for many applications, including hydronic, electric generation, and chemical processes. The effective financial payback scenarios are discussed in Section 3 with

Table 4 and

Table 5. A quick note to consider is that the overall efficiency and speed of heating will always depend on the T

out temperature (the effective heater exit temperature), whether for direct heating, a work output that is related to turbine efficiency, or when considering productivity from the chemical kinetics [

24,

25,

26,

30]. Processes that provide a higher uniformity in temperature with the highest conversion efficiency will offer the best overall efficiencies.[9,10,11,24,25.26,30,70].

There are three ways to improve energy efficiency in industrial heaters: (i) by utilizing well-built and well-insulated machinery that converts and delivers thermal energy (heat) without much loss of heat, (ii) by improving the efficiency of the final objective, and (iii) by methods that directly utilize waste heat without degrading it, or recycling waste heat into work (electric energy). To improve the overall energy efficiency, (i) change to an electric heating process, (ii) increase the Tout temperature capability, and (iii) recirculate any waste heat that is dissipated after the process objectives.

Figure 5.

Images of fossil fuel flame heating of (a) molds and (b) dies with gas burners. This is a typical non-optimized and unhealthy environment. CO2, NOx, SO2, carbon, sulfur, and ammonium particles impact the local health of humans and global warming [

1,

2,

3,

66]. In comparison, clean heating with electrically heated process gases with no direct flames ensures a cleaner and more uniform die-heating process [

28].

Figure 5.

Images of fossil fuel flame heating of (a) molds and (b) dies with gas burners. This is a typical non-optimized and unhealthy environment. CO2, NOx, SO2, carbon, sulfur, and ammonium particles impact the local health of humans and global warming [

1,

2,

3,

66]. In comparison, clean heating with electrically heated process gases with no direct flames ensures a cleaner and more uniform die-heating process [

28].

All new greenfield and green initiative innovative manufacturing processes, such as hydrogen reduction for clean steel production or clean molecular cracking methods, will likely be designed or modified to minimize thermal energy losses and optimize process control with digital methods. While this seems logical today, nearly all large-power heater processes from the past were not designed with energy efficiency in mind. The calculations below demonstrate how energy conversion can impact investment decisions in electric heating methods.

If electric heaters are to be deployed quickly as a substitute for fossil-fired heaters, they must offer attractive payback economics. Such payback can come from better heater efficiency (generally close to 95% or better with resistance electric heating, sometimes exceeding 100%). Electric heaters are often resistant-type heaters (see

Table 2) and transform energy efficiently to thermal energy (heat) that can be used directly without intermediary heat exchangers. Only the methods shown in

Table 2 are helpful for large-scale industrial electric heating where temperatures above 100°C are required.

Heaters can have a wide range of initial and operational costs depending on their construction, location of use, temperature, and other control features. The payback depends on energy efficiency and productivity, which include the heater’s performance, such as the achievable temperature, size, or manpower required to operate and maintain the equipment. Energy efficiency enhances the payback period, which is one method of calculating the benefits of investing in any energy-efficient heating process compared to a lower-cost, lower-efficiency process [

13,

14]. Equation 2 calculates an energy-efficient investment’s Net Present Value (NPV). Here, the NPV is an additional investment (

-I0) that exceeds an investment in a low-efficiency, low-cost fossil fuel heater.

Δ(CF) reflects the benefit from improved efficiency and other savings. In Equation (2), the symbol i is the discount rate, and t is the number of years the machine is expected to work before a significant equipment overhaul becomes necessary.

Figure 6.

Typical use scenarios for process-gas heating. Although the heating of air is shown in the chart, the same principles apply to other gases. Waste heat (in the surrounding environment) is sent back to the High-Speed Compressor for additional efficiency gains.

Figure 6.

Typical use scenarios for process-gas heating. Although the heating of air is shown in the chart, the same principles apply to other gases. Waste heat (in the surrounding environment) is sent back to the High-Speed Compressor for additional efficiency gains.

In the US, the cost of natural gas delivered varies by location and other factors, but the average cost per

Therm is US

$0.95, or US

$9.52 per MMBTU (293kWh). With 50% efficiency, the price of Natural gas energy (delivered price) could be about half that of electric energy. CAPEX (capital-related costs) and OPEX (operation-related costs) are shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The discount rate is taken to be 10%. It should be noted that the calculations are highly conservative. The US EPA [

71] has suggested using

$190 for CO2,

$1600 for CH4, and

$54,000 for Nox per metric ton emitted in 2023 with a 2% discount rate. We have used a 10% discount rate and a climate cost of

$283 per ton [

45], which adds approximately

$0.1/kWh to the cost of natural gas-based fossil fuel energy. Four years for investment is considered. An online payback calculator is available in Reference 87. This calculator examined various scenarios with and without climate costs and varying energy costs for heating scenarios. Two scenarios for payback are examined in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The high-efficiency (electrical) equipment is about 40% more expensive than the alternate low-efficiency equipment. Electric equipment is 90% energy efficient compared to the lower-efficiency equipment, for which the energy efficiency is 50%.

In Scenario 1, the assumed energy costs for both energy sources ) are the same (

$0.10/kWh typical in the US Midwest regions). A 100 kW electric heater is chosen over a fossil-fuel heater for an additional investment of

$5000. The additional investment is recovered within the first year. Scenario 2 (

Table 5) compares a larger investment with significantly different fuel costs. The energy cost of the fossil-fuel equipment is a fraction (1/4th) of the energy cost of the electric heater. However, higher emissions-related costs add to the potential savings from choosing the electric option. The climate costs could be GHG penalties, taxes, or locally offered mitigation-related incentives.

The savings from improved energy efficiency are compelling in most cases, and the returns appear attractive for scenarios with high energy efficiency. In practice, it is generally accepted that high-efficiency electric heaters outlast low-efficiency ones, for example, because fossil-fuel heaters always have nozzles that deteriorate, while electric heaters do not require nozzles. Nevertheless, the calculations for payback periods in

Table 3 and

Table 4 assume a similar heater lifespan yet indicate a substantial return from investing in higher efficiencies.

One of the most extensive uses of industrial heating is in the steam generator sector. High-temperature steam is used in comfort heating, sanitation, controlled drying of textiles, consumer packing (shrink packaging), curing concrete, soy production, antimicrobial uses, food processing, food safety, meat tenderizing, milk processing, laundry, skincare, pyrolysis-gasification of municipal waste and other areas. Industrial systems use a considerable amount of steam, not all of which can be recycled. In the past, steam was made by fossil fuel-heated pressure boilers, which are typically inefficient and produce water droplet-laden saturated steam, implying a significant loss in energy and water management efficiencies. New superheated steam generators can produce steam with zero water content [

106,

107]. Consequently, less water and energy can be used for many steam operations. A comparison of a shrink tunnel packaging operation that could use a conventional electric pressure vessel boiler or an electric steam generator for energy and water savings is given in

Table 6 from reference 107. Because of the various features mentioned in Table 7, the electric steam generator presents an opportunity to meet the same objectives but with much less water and energy than conventional pressure vessel boilers.

Sustainability and Reduced Energy Use with Radical Innovations

Sections 1, 2, and 3 above examined the impact of energy efficiency, CO2eq emissions reduction in electrical heating processes, and the payback economics of climate-centric innovations. Following key ideas by Dismukes [

31], radical innovation can cause disruptive industrial changes [

38,

39,

75]. A radical innovation is the creation of new products, services, or processes that significantly impact an industry or market. It often challenges established practices and norms and can replace inefficient systems and processes. Radical Industrial Heater Innovations can include a series of inventions that can save energy by improving the downstream processes to achieve the same objectives that older processes did but with radically improved efficiencies [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

93,

94,

95].

Although not thoroughly examined as a fundamental scientific principle, various self-organization mechanisms driven by the entropy generation maximization principle across multiple length scales could be thought to play a role in radical innovation processes from process to final use [

34,

38,

39,

40,

41,

93]. This new paradigm was briefly explored in an article [

34] for the possibility of entropy generation rate maximization as a principle that governs self-similar or self-organized patterns that can lead to various forms of optimization [

101,

102,

103,

104,

105], including that of flight formations for energy conservation or friction-controlling asperities that reduce pair friction or wear. In such cases, the exergy loss financial calculation [

6] could be helpful for financial payback calculations.

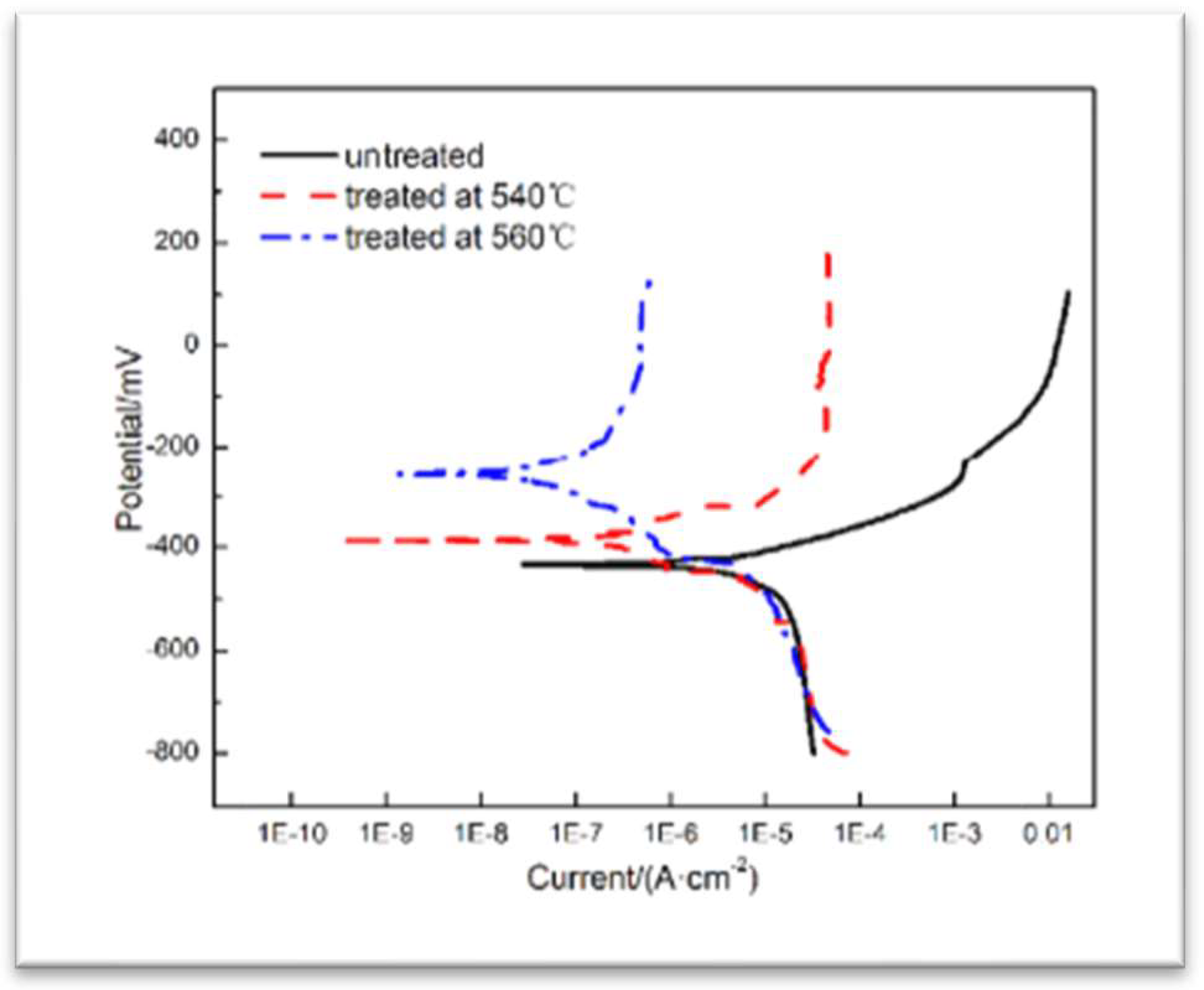

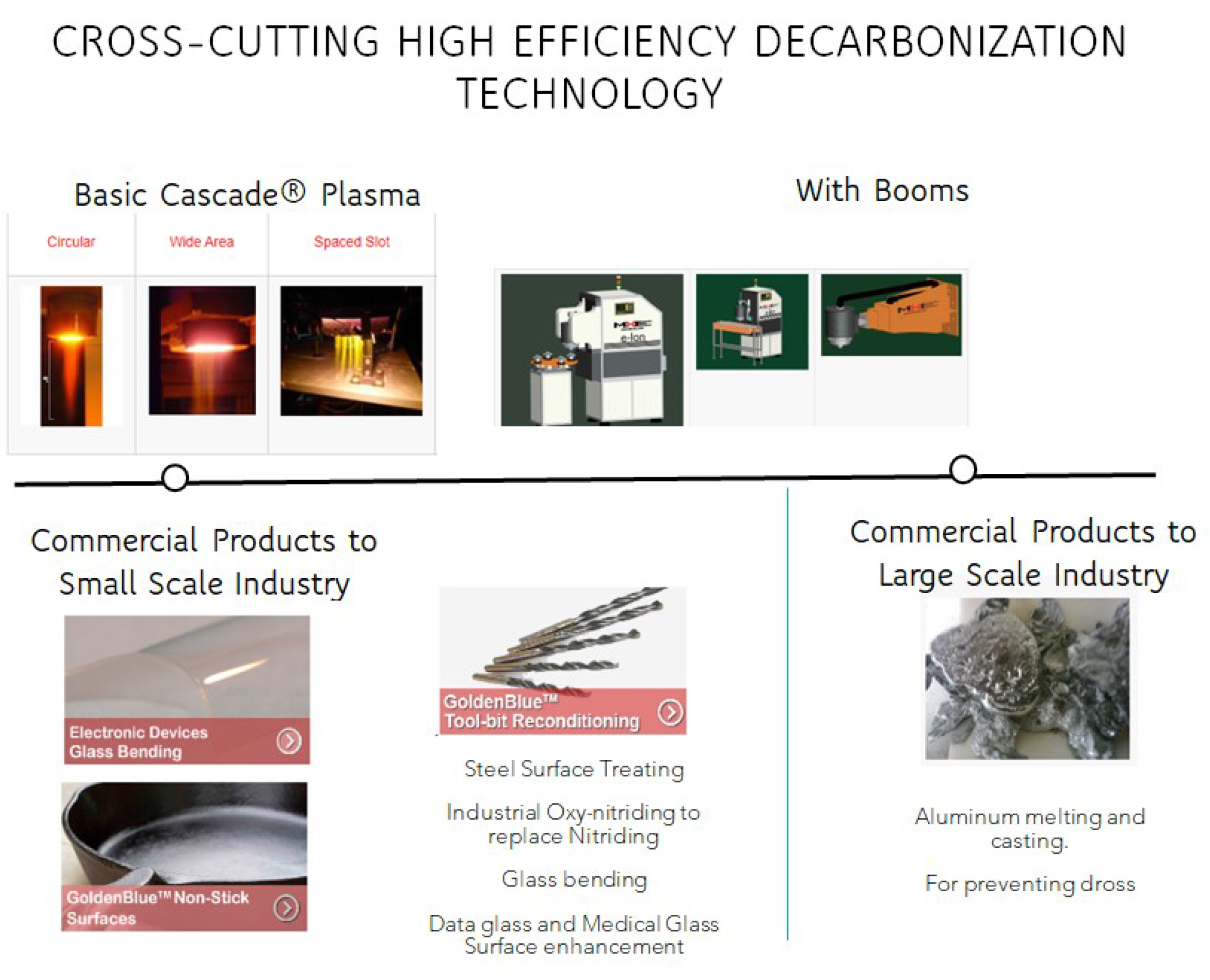

This section briefly discusses one such process where Ro-Vib (Rotaional-Vibrational) EION-activated plasma plumes can significantly reduce manufacturing energy and downstream friction and wear or catalysis actions. Some previously unpublished results from the process are shown in

Appendix A, with supporting results from recently published articles from independent international research groups. The EION process is used for the surface modification of commonly used items, some of which are illustrated in

Figure A1 (

Appendix A) [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82]. The EION process utilizes the unique thermal properties of Ro-Vib plasmas with activated species and requires only air and electric input [

36,

42,

43,

44]. This process was initially developed to address energy and productivity challenges faced in surface nitriding applications, where material wear and energy loss due to high friction are significant concerns. The importance of the EION nitriding process lies in its avoidance of energy-intensive ammonia gas decomposition, ionization, or cracking to release nascent nitrogen onto the steel surface. Instead, it employs extremely low power to produce Ro-Vib-activated species that can meet nitriding requirements.

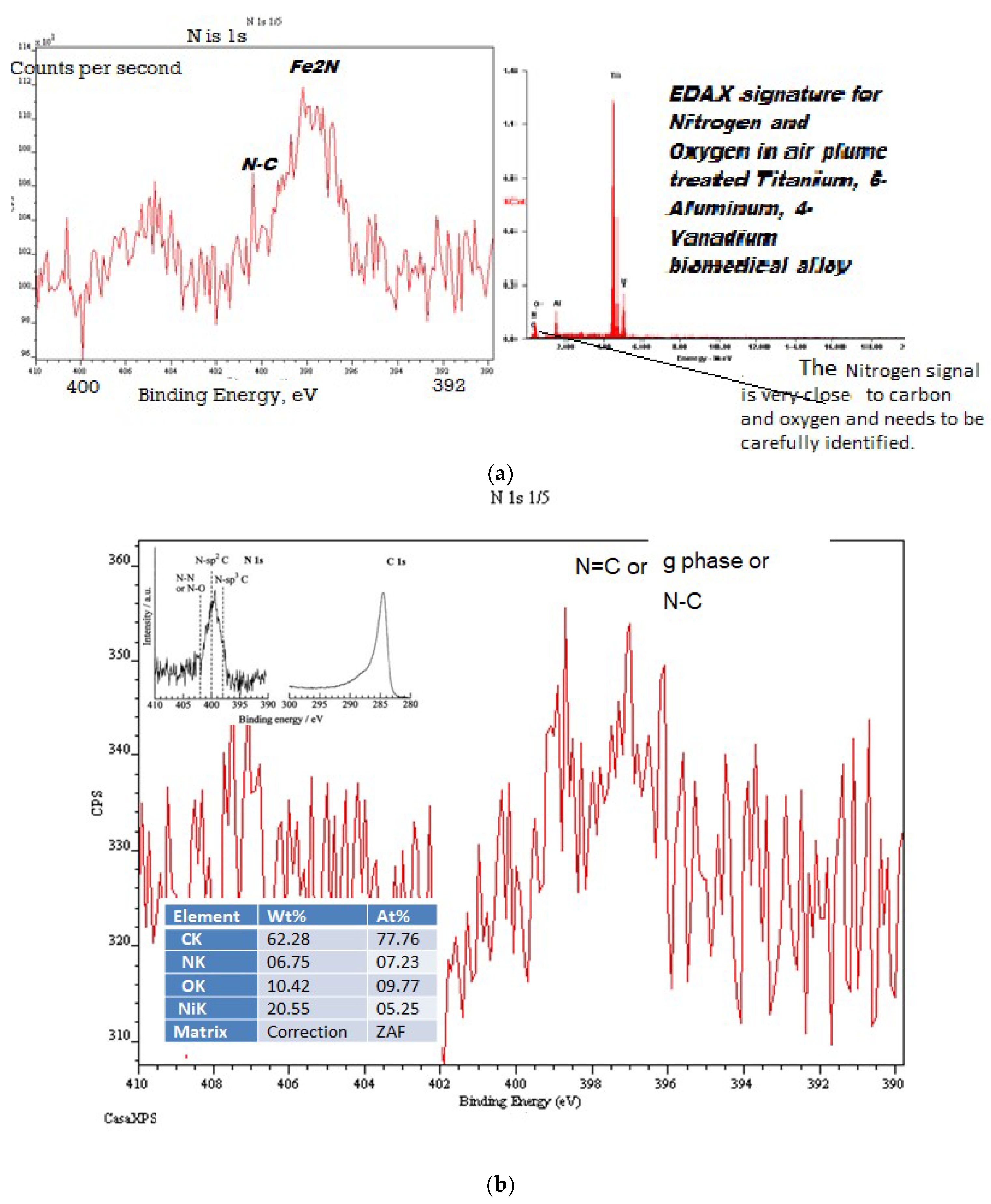

The EION plume species shown in

Figure A1 (

Appendix A) can provide rapid surface nitriding, particularly on iron and iron alloys, by directly impinging it to a surface requiring hardening or other property improvements. The plume interaction times are in order of seconds for obtaining hard and low friction surfaces. The time taken for conventional nitride processing is several hours (a closed chamber is required in traditional nitriding processes, both gas and microwave plasma-assisted conventional nitriding processes). In closed chamber processes, the parts that require nitriding (typically gears, shafts, and valves) are arranged inside a large chamber that can only be emptied or filled very slowly. The EION is an open plume process where the parts are exposed to the plume only for a few seconds. Productivity and energy savings benefits are significant with the EION method, assuming a part is treated every 3 seconds in the EION plume. Significant energy savings are gleaned when a batch of ten tool bits can be treated in a 10 kW EION beam at a time (

Figure 1A in

Appendix A). Based on thermal and energy studies [37,51,52,53,54,55.56,57,58,59,60], the beam-power density of an open directable plume (Ro-Vib plasma plume) from a 10KW electrical input yields plumes with a power density of ~

106-109 W/m2. This power is higher than even the most high-power concentrated continuous laser beams. The beam size is large (compared to focused lasers), thus permitting a large impact area on a surface. No electrodes are bombarded or degraded, as is common in arc and microwave plasma nitriding systems. The EION plasma plume can use air or a benign gas like nitrogen for the plume production.

Typical 200 kW power conventional nitriding machines require a minimum of 3 hours of total operation. Such conventional nitriding machines can simultaneously treat about 100-200 parts (albeit over several hours). As the EION is an open beam, the part change-over can happen within 30 seconds in a continuous mode, e.g., on a moving mesh belt. The total energy use decreases from 600 kWh (assuming 3 hours of treatment with conventional techniques) to 0.13 kWh (10 KW EION machine and 5-20s exposure time). This implies a ~36X productivity benefit in time. Assume both processes require one or two people at an aggregate rate of $80/hr. for labor rate. The conventional nitriding will, therefore, price at approximately $2-$6 per part, whereas EION offers approximately $0.08-$0.16 per part. This is a significant saving in addition to the almost 300% energy savings per manufactured part, which translates to climate emissions savings, as noted in the introduction sections of this article.

Appendix A presents several previously unpublished nitrided properties of surfaces exposed to the EION beam. The hardness of many steel alloys increases by over 50% after just 5 to 20 seconds of exposure to the plume (as shown in

Table A1,

Appendix A). This increase is due to the formation of nanoscale nitrides and oxynitrides. The hardness increase is at least comparable to that achieved through the conventional nitriding process. For high-strength steels containing molybdenum, hardness rises from a Nano Vickers Hardness of Hv=800 to Hv=1300 with only 15 seconds of exposure to a 10-kW beam, as illustrated in

Table A1 of

Appendix A. When the EION process was first patented and disclosed, there was considerable concern regarding the presence of nitrogen in a process that took only a few seconds to complete. This concern was later addressed by careful X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, which confirmed the presence of nitrogen. Short exposures with the Ro-Vib EION-activated plasmas can create several Fe-N phases and carbon-nitrogen bonds, as shown in

Figure A2 (a) and (b), respectively.

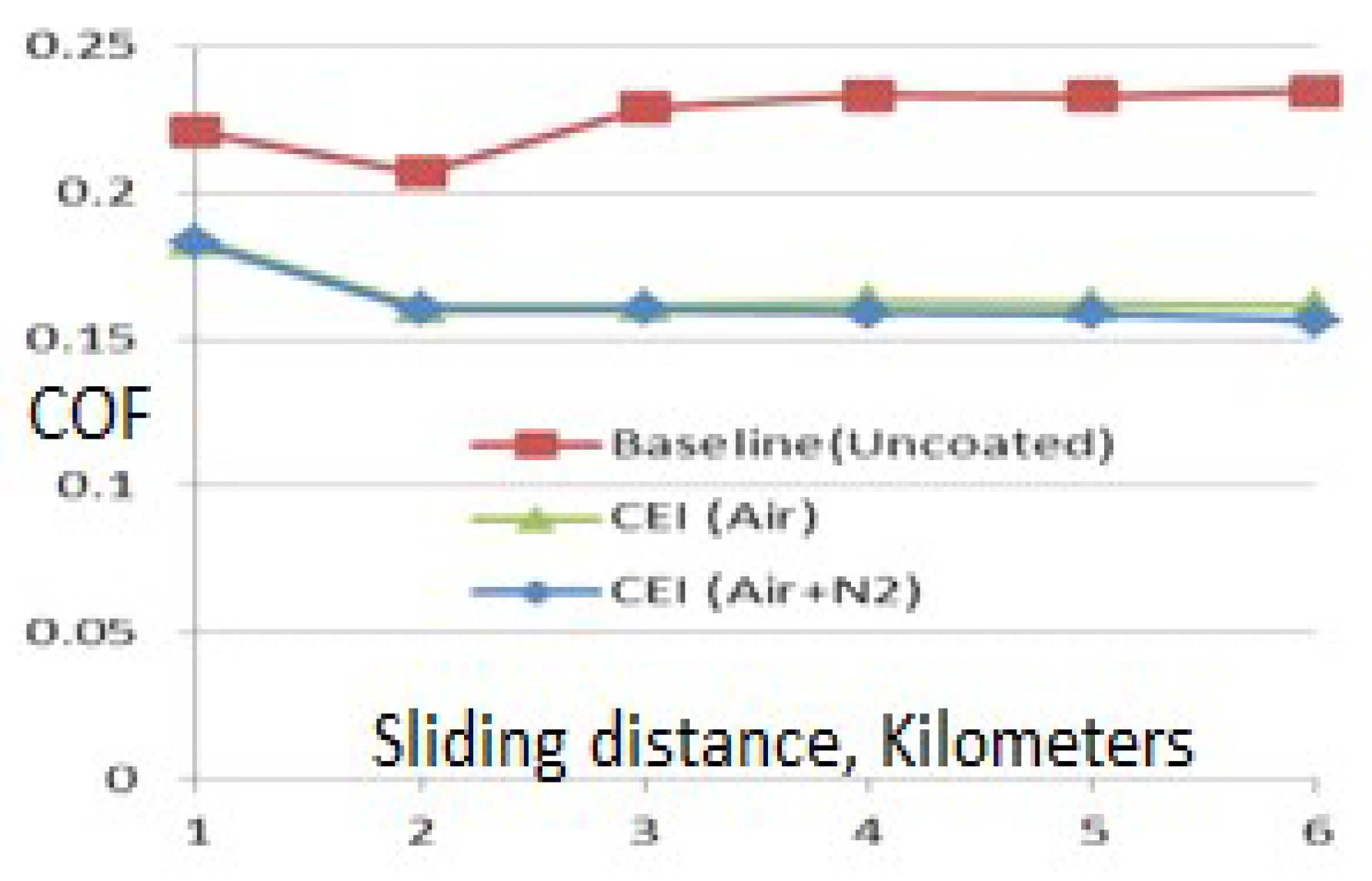

The new processing approach has further downstream benefits, such as in the coefficient of friction. Reducing the coefficient of friction (COF) significantly boosts efficiency, especially for tool bit use and automotive components. Approximately 23% of the world’s total energy consumption (exceeding 575 Exajoules per year) arises from tribological contacts [

82]. About 20% of this energy (around 114 Exajoules per year) is utilized to overcome friction, while roughly 3% (about 17 Exajoules per year) is allocated for remanufacturing worn parts and spare equipment.

Appendix A,

Figure A4 illustrates that the COF benefits could reach up to 50%. Improved tribological technologies are projected to cut harmful emissions by as much as 1,460 MT globally for energy production [

82]. The impact of low friction on climate is examined in detail in several studies [

55,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

88,

90]. Traditional nitrogen ion nitriding parts exhibit a COF of about 0.38.

The COF for the treated surfaces is ~0.15 (

Figure A3 in

Appendix A), indicating a drop of approximately 60% compared to similar treatments using conventional processes with base steel, which is low-cost steel compared to the current higher-price nitridable steels. The COF almost always increases in conventional nitriding processes compared to untreated surfaces unless a secondary smoothing operation is performed. Based on limited studies, secondary operations can be avoided when EION technology is utilized.

All these features make the EION process one of the most efficient energy conversion and high-productivity plasma devices for enhancing metal surfaces, establishing it possibly as a groundbreaking radical-innovative technology for heaters. Such innovations offer dramatic energy savings during a process and significant energy efficiencies in downstream processes. For example, tool bits conditioned by such technologies can half the drilling time, improve the drilled hole characteristics, and dramatically increase productivity [

77,

93].

Such novel Ro-Vib plasma heater devices have an impact beyond surface treatment, e.g., in glass-bending and aluminum melting [

77] (see

Figure 7). Any dross savings in the aluminum melting sector equals substantial energy savings for both primary and secondary melting. Because of the creation of Ro-Vib activated species, the output activated-air gas from the EION can be used instead of an expensive inert or nitrogen gas cover during aluminum melting processes, leading to low dross formation. Although energy-efficient aluminum melting of 0.2kWhr/lb is routinely possible with electrically heated aluminum melting, the low dross and clean atmosphere are significant benefits of the EION source in aluminum processing [

51]. The savings from dross reduction, regardless of climate costs, are significant. For example, if the price of 1 metric ton of aluminum is ~

$1000, a 2% savings in dross leads to

$20 in savings per ton of aluminum. Most small-scale aluminum plants process about 10 tons a day per furnace. Assume one year has 200 working days; this equals 2000 tons a year per furnace. The savings per year are

$40,000 with a 2% dross savings. It is common for a gas-fired furnace to make as much as 8-10% of dross. This means the savings in the lost dross correspondingly would be about 8%-10% by weight for a 10-ton per day aluminum furnace, ~ ~US

$160,000-US

$200,000 per year. This is another example of radical innovation.

5. Summary and Conclusions

The industrial heating sector is where anthropological emissions have not yet been fully addressed. This article highlights the environmental crisis caused by rising CO₂ emissions from fossil fuel heating equipment and emphasizes the need for industrial decarbonization by reducing their use. Transitioning to electrified industrial heating is essential for swiftly lowering global carbon emissions. Electric heating methods are recognized for their commercial advantages. The article concentrates on electrification as a practical solution to reduce emissions, driven by efficiency improvements, technical advancements, and the economic viability of large-scale electric heating.

The technical issues addressed in this article are:

Industrial Heat and Emissions: Process heat is essential for metallurgy, power generation, and chemical production industries. However, industrial heating using fossil fuels significantly contributes to global CO₂ emissions.

Electrification of Heating: Transitioning from fossil fuel-based heating to electric heating is the quickest way to decarbonize industrial processes, considering that electric methods provide higher efficiency and zero emissions.

Technical Advances and Waste Heat Recovery: Waste heat recovery methods, enhanced heating materials, and advanced control systems are identified as key areas for energy efficiency, both for work-enabled reuse, like conversion to electricity, and thermal energy-enabled reuse, which boosts overall energy use.

Economic Considerations and Payback Analysis: The cost-benefit analysis indicates that high-efficiency electric heaters, despite their higher initial costs, offer rapid payback periods due to energy savings, reduced ancillary equipment and piping requirements, and lowered emissions. The scenarios considered include equal fossil fuel energy prices and situations where fossil fuel is priced at one-fourth of electric energy.

Radical Innovations: Emerging technologies like EION plasma and Ro-Vib activated species processing showcase how disruptive innovations can significantly enhance efficiency, decrease energy use, and improve industrial productivity.

Decarbonization: Decarbonizing industrial heating is vital in combating climate change and presents opportunities for technological advancements and substantial economic benefits. Electrification paves the way for a more sustainable and efficient industrial landscape.