Submitted:

26 February 2025

Posted:

27 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0. INTRODUCTION

2.0. SUSTAINABILITY DEVELOPMENT LIMITATIONS IN MATERIAL UTILISATION.

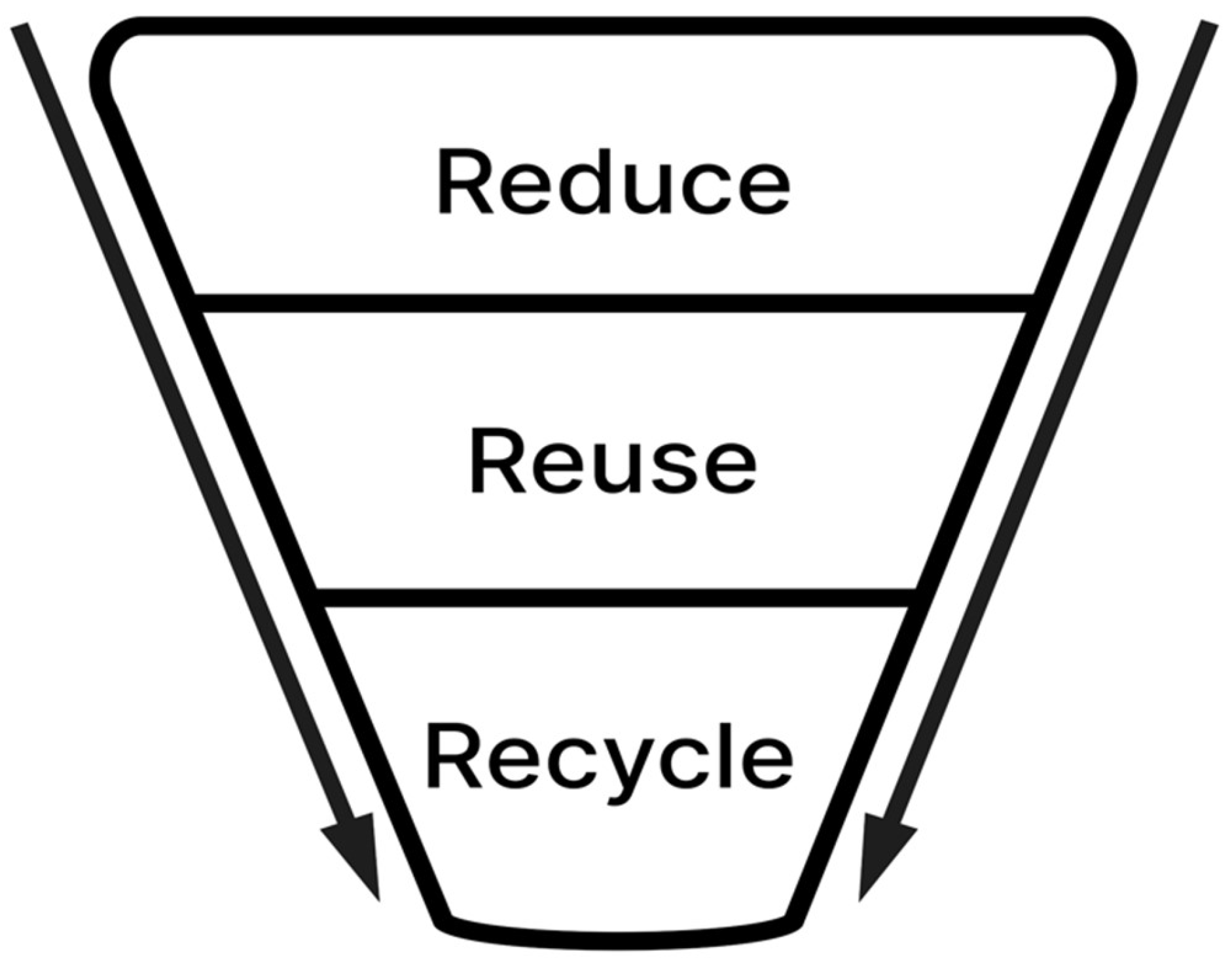

2.1. REDUCE

2.2. REUSE

2.3. RECYCLE

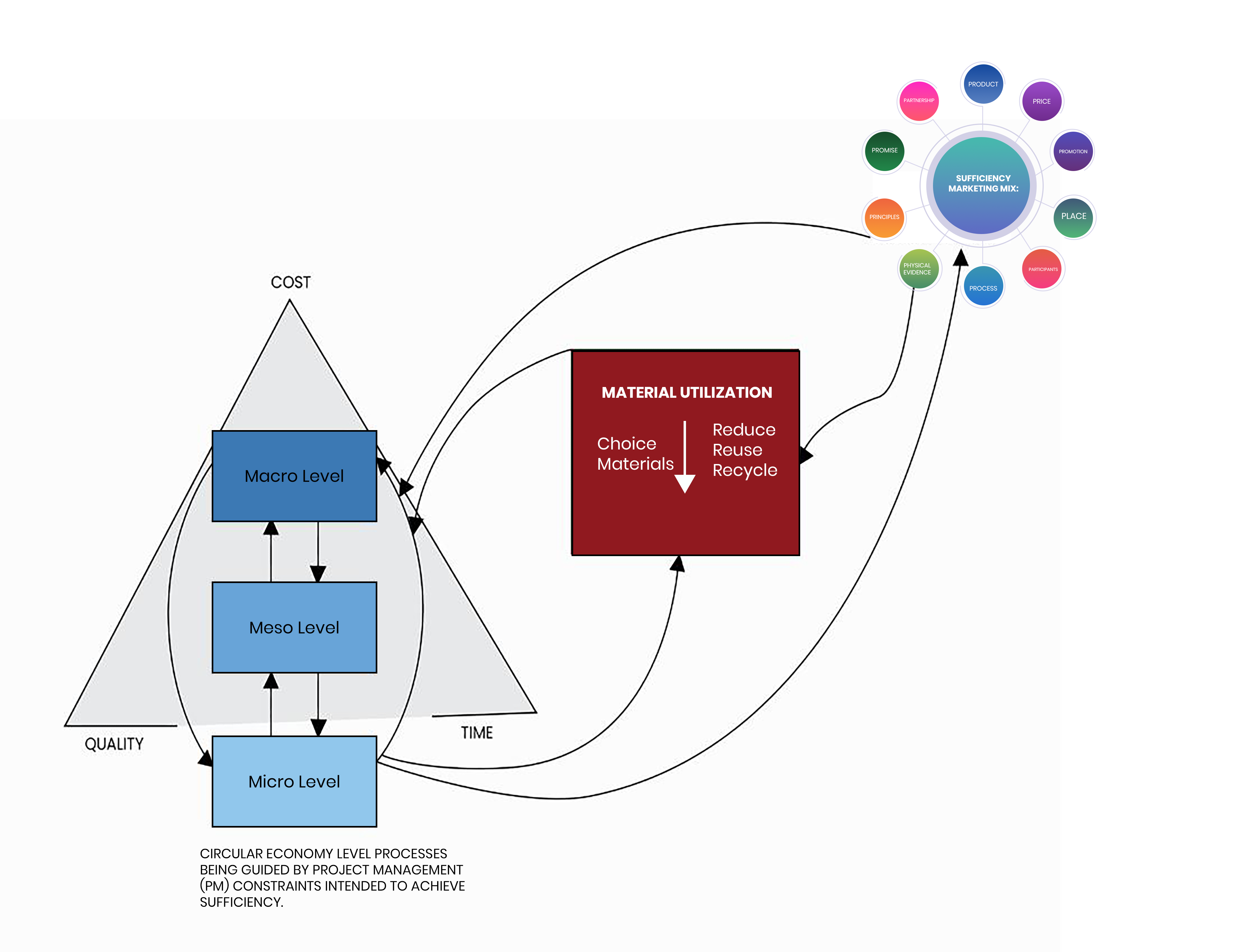

3.0. ACHIEVING SUFFICIENCY IN MATERIAL UTILISATION

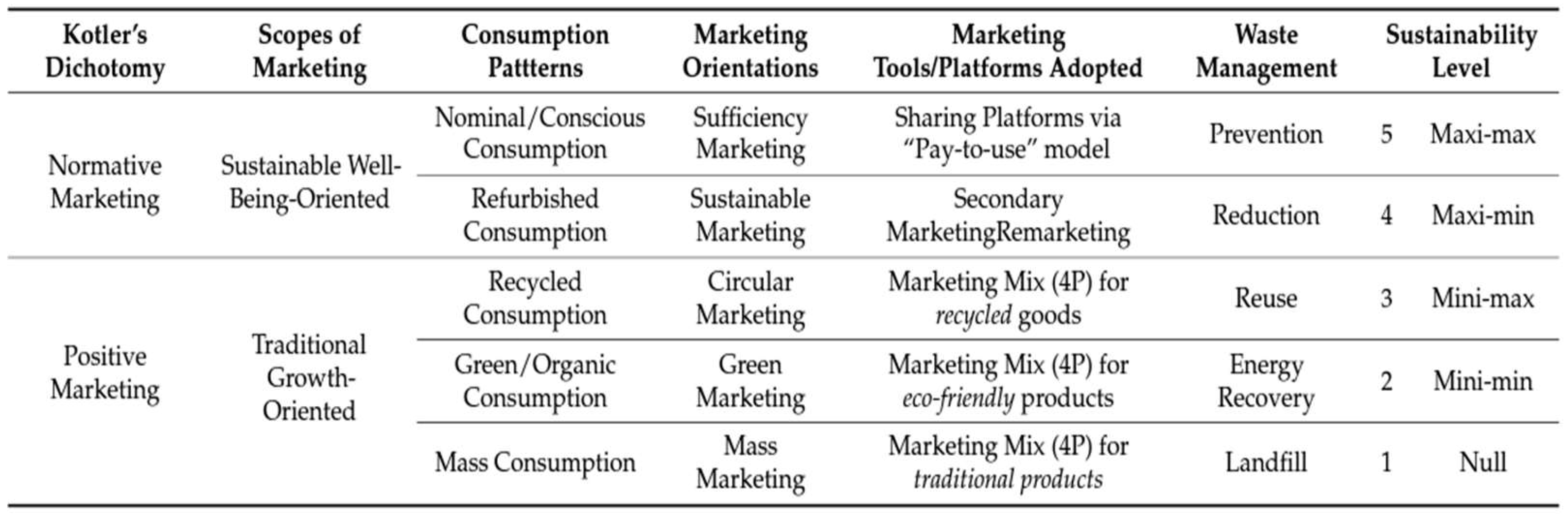

3.1. SUFFICIENCY MARKETING

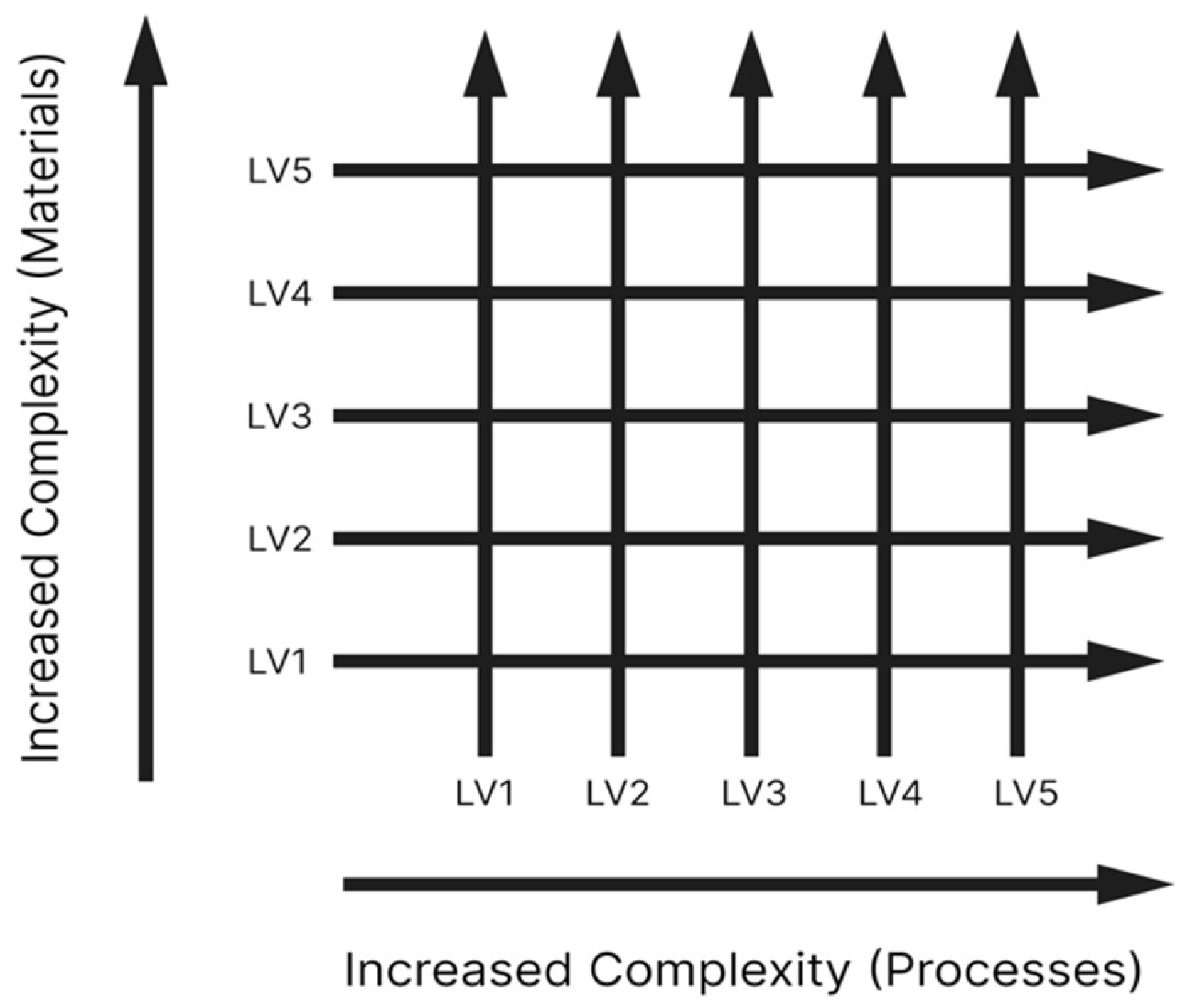

3.2. CIRCULAR ECONOMY LEVELS

3.2.1. Micro-Level or Intra-firm operation

3.2.2. Meso-Level or inter-firm operations

3.2.3. Macro-level or national and regional level

4.0. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATION

5.0. LIMITATIONS

Funding

COMPETING INTERESTS

ETHICS APPROVAL

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION STATEMENTS

References

- Adami, L. and Schiavon, M. (2021) ‘From circular economy to circular ecology: a review on the solution of environmental problems through circular waste management approaches’, Sustainability, 13(2), p. 925. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/2/925 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Agarwal, S., Tyagi, M. and Garg, R.K. (2023) ‘Conception of circular economy obstacles in context of supply chain: a case of rubber industry’, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 72(4), pp. 1111–1153. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJPPM-12-2020-0686/full/html (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Aktaş, C.B. (2022) ‘Dematerialization: Needs and Challenges’, in W. Leal Filho et al. (eds) Handbook of Sustainability Science in the Future. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ali, T. et al. (2020) ‘IoT-Based Smart Waste Bin Monitoring and Municipal Solid Waste Management System for Smart Cities’, Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 45(12), pp. 10185–10198. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.M. (2014) ‘Squaring the circular economy: the role of recycling within a hierarchy of material management strategies’, in Handbook of recycling. Elsevier, pp. 445–477. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780123964595000301 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Allwood, J.M. (2024) ‘Material efficiency—Squaring the circular economy: Recycling within a hierarchy of material management strategies’, in Handbook of Recycling. Elsevier, pp. 45–78. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323855143000166 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Bélanger-Gravel, A. et al. (2019) ‘Pattern and correlates of public support for public health interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages’, Public health nutrition, 22(17), pp. 3270–3280. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/public-health-nutrition/article/pattern-and-correlates-of-public-support-for-public-health-interventions-to-reduce-the-consumption-of-sugarsweetened-beverages/B167B42E16C9F84B72518AB817013E34 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Bianchini, A., Rossi, J. and Pellegrini, M. (2019) ‘Overcoming the main barriers of circular economy implementation through a new visualization tool for circular business models’, Sustainability, 11(23), p. 6614. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/11/23/6614 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Bosangit, C., Iyanna, S. and Koenig-Lewis, N. (2023) ‘Psst! Don’t tell anyone it’s second-hand: drivers and barriers of second-hand consumption in emerging markets’, Research Handbook on Ethical Consumption: Contemporary Research in Responsible and Sustainable Consumer Behaviour, p. 225. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=uki-EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA225&dq=secod+hand+market+Africa+clothes+vehicles+and+appliances+&ots=wtbLnMZzea&sig=wb6hkErhNzvCg9CRUqHo2XNBnHU (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Boulding, K.E. (2013) ‘The economics of the coming spaceship earth’, in Environmental quality in a growing economy. RFF Press, pp. 3–14. Available online: https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/chapters/edit/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.4324/9781315064147-2&type=chapterpdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Bouman, T., Steg, L. and Dietz, T. (2021) ‘Insights from early COVID-19 responses about promoting sustainable action’, Nature Sustainability, 4(3), pp. 194–200. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-020-00626-x (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Braungart, M.; McDonough, W. Cradle to cradle; Random House, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, T.-D. et al. (2022) ‘Opportunities and challenges for solid waste reuse and recycling in emerging economies: A hybrid analysis’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 177, p. 105968. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344921005772 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Cordella, M. et al. (2020) ‘Improving material efficiency in the life cycle of products: a review of EU Ecolabel criteria’, The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 25(5), pp. 921–935. [CrossRef]

- Corona, B. et al. (2019) ‘Towards sustainable development through the circular economy—A review and critical assessment on current circularity metrics’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 151, p. 104498. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344919304045 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- D’Adamo, I., Gastaldi, M. and Rosa, P. (2020) ‘Recycling of end-of-life vehicles: Assessing trends and performances in Europe’, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 152, p. 119887. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0040162519320311 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Daehn, K. et al. (2022) ‘Innovations to decarbonize materials industries’, Nature Reviews Materials, 7(4), pp. 275–294. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41578-021-00376-y (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Dahanni, H. et al. (2024) ‘Life cycle assessment of cement: Are existing data and models relevant to assess the cement industry’s climate change mitigation strategies? A literature review’, Construction and Building Materials, 411, p. 134415. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095006182304134X (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- De Giovanni, P. and Folgiero, P. (2023) Strategies for the circular economy: Circular districts and networks. Taylor & Francis. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=siWnEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT9&dq=squaring+the+circular+economy:+the+role+of+recycling+within+a+heirarchy+of+material+management+strategies+&ots=_uh2-hLC-8&sig=XReOXRxAf2r5VRfMCy5eMittipU (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Degli Esposti, P., Mortara, A. and Roberti, G. (2021) ‘Sharing and Sustainable Consumption in the Era of COVID-19’, Sustainability, 13(4), p. 1903. 1903. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/4/1903 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Dhar, S., Pathak, M. and Shukla, P.R. (2020) ‘Transformation of India’s steel and cement industry in a sustainable 1.5 C world’, Energy Policy, 137, p. 111104. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421519306913 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Diwan, H. and Unnikrishnan, S. (2023) ‘Prospects of Circularity in Steel Industry: Mapping Through LCA Approach’, in S.S. Muthu (ed.) Life Cycle Assessment & Circular Economy. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland (Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes), pp. 35–46. [CrossRef]

- Dobre, C. et al. (2021) ‘The common values of social media marketing and luxury brands. The millennials and generation z perspective’, Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(7), pp. 2532–2553. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/0718-1876/16/7/139 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Ellsworth-Krebs, K. (2020) ‘Implications of declining household sizes and expectations of home comfort for domestic energy demand’, Nature Energy, 5(1), pp. 20–25. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41560-019-0512-1 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Emas, R. (2015) ‘The concept of sustainable development: definition and defining principles’, Brief for GSDR, 2015, pp. 10–13140. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/documents/5839GSDR%25202015_SD_concept_definiton_rev.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Etzioni, A. (2021) ‘Capitalism Needs to Be Re-encapsulated’, Society, 58(1), pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, Y.A. et al. (2020) ‘Industry 4.0 based sustainable circular economy approach for smart waste management system to achieve sustainable development goals: A case study of Indonesia’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 269, p. 122263. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652620323106 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Fellner, J. and Brunner, P.H. (2022) ‘Plastic waste management: is circular economy really the best solution?’, Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 24(1), pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, W.; et al. Ferdous, W. et al. (2021) ‘Recycling of landfill wastes (tyres, plastics and glass) in construction–A review on global waste generation, performance, application and future opportunities’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 173, p. 105745. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344921003542 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Ghisellini, P., Cialani, C. and Ulgiati, S. (2016) ‘A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems’, Journal of Cleaner production, 114, pp. 11–32. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652615012287 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Giannetti, B.F. et al. (2020) ‘Cleaner production for achieving the sustainable development goals’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 271, p. 122127. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652620321740 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Gielen, D. et al. (2020) ‘Renewables-based decarbonization and relocation of iron and steel making: A case study’, Journal of Industrial Ecology, 24(5), pp. 1113–1125. [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.D. and Brungard, E. (2021) ‘Consumer adoption of plug-in electric vehicles in selected countries’, Future Transportation, 1(2), pp. 303–325. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-7590/1/2/18 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Han, S.-L. and Kim, K. (2020) ‘Role of consumption values in the luxury brand experience: Moderating effects of category and the generation gap’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, p. 102249. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0969698920312571 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Hansen, K.T. and Le Zotte, J. (2022) ‘Introduction: Changing Secondhand Economies’, in Global Perspectives on Changing Secondhand Economies. Routledge, pp. 1–16. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003258285-1/introduction-karen-tranberg-hansen-jennifer-le-zotte (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Holappa, L. (2020) ‘A general vision for reduction of energy consumption and CO2 emissions from the steel industry’, Metals, 10(9), p. 1117. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4701/10/9/1117?ref=boiling-cold (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Howarth, C. et al. (2020) ‘Building a Social Mandate for Climate Action: Lessons from COVID-19’, Environmental and Resource Economics, 76(4), pp. 1107–1115. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, I.-Y.L., Pan, M.S. and Green, W.H. (2020) ‘Transition to electric vehicles in China: Implications for private motorization rate and battery market’, Energy policy, 144, p. 111654. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421520303852 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Husain, I. et al. (2021) ‘Electric drive technology trends, challenges, and opportunities for future electric vehicles’, Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(6), pp. 1039–1059. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9316773/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Iacovidou, E. et al. (2017) ‘Metrics for optimising the multi-dimensional value of resources recovered from waste in a circular economy: A critical review’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 166, pp. 910–938. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652617315421 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Iacovidou, E., Hahladakis, J.N. and Purnell, P. (2021) ‘A systems thinking approach to understanding the challenges of achieving the circular economy’, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(19), pp. 24785–24806. [CrossRef]

- Ikromjonovich, B.I. (2023) ‘Sustainable Development in The Digital Economy: Balancing Growth and Environmental Concerns’, Al-Farg’oniy avlodlari, 1(3), pp. 42–50. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/sustainable-development-in-the-digital-economy-balancing-growth-and-environmental-concerns (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Islam, M.M. and Hasanuzzaman, M. (2020) ‘Introduction to energy and sustainable development’, in Energy for sustainable development. Elsevier, pp. 1–18. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128146453000018 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Jiang, P., Van Fan, Y. and Klemeš, J.J. (2021) ‘Impacts of COVID-19 on energy demand and consumption: Challenges, lessons and emerging opportunities’, Applied energy, 285, p. 116441. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030626192100009X (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Kelleci, A. and Yıldız, O. (2021) ‘A guiding framework for levels of sustainability in marketing’, Sustainability, 13(4), p. 1644. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/4/1644 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Keßler, L., Matlin, S.A. and Kümmerer, K. (2021) ‘The contribution of material circularity to sustainability—Recycling and reuse of textiles’, Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry, 32, p. 100535. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2452223621000912 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Khalid, M.Y. et al. (2022) ‘Recent trends in recycling and reusing techniques of different plastic polymers and their composite materials’, Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 31, p. e00382. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214993721001378 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Khalife, M.A. and Dunay, A. (2019) ‘Project business model with the role of digitization and circular economies in project management’, Modern Science, 6, pp. 106–113. Available online: https://www.nemoros.cz/_files/ugd/b7f2f7_fc43f5e7f6ba4bd3a7520918908abfb9.pdf#page=106 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Kisku, N. et al. (2017) ‘A critical review and assessment for usage of recycled aggregate as sustainable construction material’, Construction and building materials, 131, pp. 721–740. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950061816317810 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Kravchenko, M., Pigosso, D.C. and McAloone, T.C. (2020) ‘A trade-off navigation framework as a decision support for conflicting sustainability indicators within circular economy implementation in the manufacturing industry’, Sustainability, 13(1), p. 314. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/1/314 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Kumar, P. and Shukla, S. (2023) ‘Utilization of steel slag waste as construction material: A review’, Materials Today: Proceedings, 78, pp. 145–152. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214785323000317 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Lamba, P. et al. (2022) ‘Recycling/reuse of plastic waste as construction material for sustainable development: a review’, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(57), pp. 86156–86179. [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, V.S. (2020) ‘Digital Economy as a Factor in the Technological Development of the Mineral Sector’, Natural Resources Research, 29(3), pp. 1521–1541. [CrossRef]

- Maes, T. and Preston-Whyte, F. (2022) ‘E-waste it wisely: lessons from Africa’, SN Applied Sciences, 4(3), p. 72. [CrossRef]

- Maitre-Ekern, E. (2018) ‘Exploring the spaceship Earth: a circular economy for products’. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3330526 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Mancini, L. et al. (2019) ‘Mapping the role of raw materials in sustainable development goals’, A Preliminary Analysis of Links, Monitoring Indicators, and Related Policy Initiatives, 3, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/f8602990-72dd-4177-a331-68994ea28a79/mapping%20the%20role%20of%20raw%20materials%20in%20sustainable%20development-KJ1A29595ENN.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Manieson, L.A. and Ferrero-Regis, T. (2023) ‘Castoff from the West, pearls in Kantamanto? A critique of second-hand clothes trade’, Journal of Industrial Ecology, 27(3), pp. 811–821. [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, M. et al. (2021) ‘Life cycle assessment (LCA) of concrete prepared with sustainable cement-based materials’, Materials Today: Proceedings, 47, pp. 3637–3644. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214785321003370 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Mariotti, N. et al. (2020) ‘Recent advances in eco-friendly and cost-effective materials towards sustainable dye-sensitized solar cells’, Green chemistry, 22(21), pp. 7168–7218. Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2020/gc/d0gc01148g (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Meza, J.K.S. et al. (2019) ‘Predictive analysis of urban waste generation for the city of Bogotá, Colombia, through the implementation of decision trees-based machine learning, support vector machines and artificial neural networks’, Heliyon, 5(11). Available online: https://www.cell.com/heliyon/pdf/S2405-8440 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Mohammed, M. et al. (2020) ‘A review on achieving sustainable construction waste management through application of 3R (reduction, reuse, recycling): A lifecycle approach’, in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing, p. 012010. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/476/1/012010/meta (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Nikolaou, I.E. and Tsagarakis, K.P. (2021) ‘An introduction to circular economy and sustainability: Some existing lessons and future directions’, Sustainable Production and Consumption. Elsevier. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352550921001834 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Ogunmakinde, O.E., Egbelakin, T. and Sher, W. (2022a) ‘Contributions of the circular economy to the UN sustainable development goals through sustainable construction’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 178, p. 106023. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344921006315 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Ogunmakinde, O.E., Egbelakin, T. and Sher, W. (2022b) ‘Contributions of the circular economy to the UN sustainable development goals through sustainable construction’, Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 178, p. 106023. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344921006315 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Panchal, R., Singh, A. and Diwan, H. (2021) ‘Does circular economy performance lead to sustainable development?–A systematic literature review’, Journal of Environmental Management, 293, p. 112811. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479721008732 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Pomering, A. (2017) ‘Marketing for Sustainability: Extending the Conceptualisation of the Marketing Mix to Drive Value for Individuals and Society at Large’, Australasian Marketing Journal, 25(2), pp. 157–165. [CrossRef]

- Puntillo, P. (2023) ‘Circular economy business models: Towards achieving sustainable development goals in the waste management sector—Empirical evidence and theoretical implications’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(2), pp. 941–954. [CrossRef]

- Rahla, K.M., Mateus, R. and Bragança, L. (2021) ‘Selection criteria for building materials and components in line with the circular economy principles in the built environment—A review of current trends’, Infrastructures, 6(4), p. 49. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2412-3811/6/4/49 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Rattanachu, P. et al. (2020) ‘Performance of recycled aggregate concrete with rice husk ash as cement binder’, Cement and Concrete Composites, 108, p. 103533. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095894652030024X (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Reis, D.C. et al. (2021) ‘Potential CO 2 reduction and uptake due to industrialization and efficient cement use in Brazil by 2050’, Journal of Industrial Ecology, 25(2), pp. 344–358. [CrossRef]

- Ren, L. et al. (2021) ‘A review of CO2 emissions reduction technologies and low-carbon development in the iron and steel industry focusing on China’, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 143, p. 110846. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032121001404 (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Sakalasooriya, N. (2021) ‘Conceptual analysis of sustainability and sustainable development’, Open Journal of Social Sciences, 9(03), p. 396. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/html/26-1764360_108042.htm (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Saleh, H. (2020) ‘Implementation of sustainable development goals to makassar zero waste and energy source’, International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy [Preprint]. Available online: http://www.zbw.eu/econis-archiv/bitstream/11159/8450/1/1756272727_0.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Sanchez, B. and Haas, C. (2018) ‘Capital project planning for a circular economy’, Construction Management and Economics, 36(6), pp. 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Sariatli, F. (2017) ‘Linear Economy Versus Circular Economy: A Comparative and Analyzer Study for Optimization of Economy for Sustainability’, Visegrad Journal on Bioeconomy and Sustainable Development, 6(1), pp. 31–34. [CrossRef]

- Schrijvers, D. et al. (2020) ‘A review of methods and data to determine raw material criticality’, Resources, conservation and recycling, 155, p. 104617. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921344919305233 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Severo, E.A., De Guimarães, J.C.F. and Dellarmelin, M.L. (2021) ‘Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on environmental awareness, sustainable consumption and social responsibility: Evidence from generations in Brazil and Portugal’, Journal of cleaner production, 286, p. 124947. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095965262034991X (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Shen, Z. et al. (2023) ‘Quantifying Sustainability and Landscape Performance: A Smart Devices Assisted Alternative Framework’, Sustainability, 15(17), p. 13239. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/17/13239 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Shola, A.T.I. and Olanrewaju, D.K. (2020) ‘Effects of the informal cross border trade in Western Africa: A study of Nigeria and Niger’, Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen, Ekonomi Dan Bisnis, 4(2), pp. 34–42. Available online: http://www.jameb.stimlasharanjaya.ac.id/JAMEB/article/view/102 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Shulla, K. et al. (2021) ‘Effects of COVID-19 on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)’, Discover Sustainability, 2(1), p. 15. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K. and Chudasama, H. (2021) ‘Conceptualizing and achieving industrial system transition for a dematerialized and decarbonized world’, Global Environmental Change, 70, p. 102349. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S095937802100128X (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Smil, V. (2023) Materials and Dematerialization: Making the Modern World. John Wiley & Sons. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=llO-EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=dematerialisation+of+steel+in+construction+and+automobile+industry&ots=U-gipAWn0h&sig=RIcil2olCc5YyEp2Eutb227WFto (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Sodiq, A. et al. (2019) ‘Towards modern sustainable cities: Review of sustainability principles and trends’, Journal of Cleaner Production, 227, pp. 972–1001. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652619311837 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Tao, M. et al. (2020) ‘Major challenges and opportunities in silicon solar module recycling’, Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications, 28(10), pp. 1077–1088. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.K. et al. (2020) ‘Time-frequency causality and connectedness between international prices of energy, food, industry, agriculture and metals’, Energy Economics, 85, p. 104529. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S014098831930324X (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Valentine, M. (2020) Conscious consumerism: How brands are rising to the challenge, Marketing Week. Available online: https://www.marketingweek.com/conscious-consumerism-brand-challenge/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Van Fan, Y. et al. (2019) ‘Cross-disciplinary approaches towards smart, resilient and sustainable circular economy’, Journal of cleaner production, 232, pp. 1482–1491. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652619318025 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Velenturf, A.P. and Purnell, P. (2021) ‘Principles for a sustainable circular economy’, Sustainable Production and Consumption, 27, pp. 1437–1457. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352550921000567 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Velvizhi, G. et al. (2022) ‘Integrated biorefinery processes for conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to value added materials: Paving a path towards circular economy’, Bioresource technology, 343, p. 126151. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960852421014930 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Yu, K.H. et al. (2021) ‘Environmental planning based on reduce, reuse, recycle and recover using artificial intelligence’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 86, p. 106492. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195925520306132 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Zorpas, A.A. (2020) ‘Strategy development in the framework of waste management’, Science of the total environment, 716, p. 137088. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969720305982 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).