Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

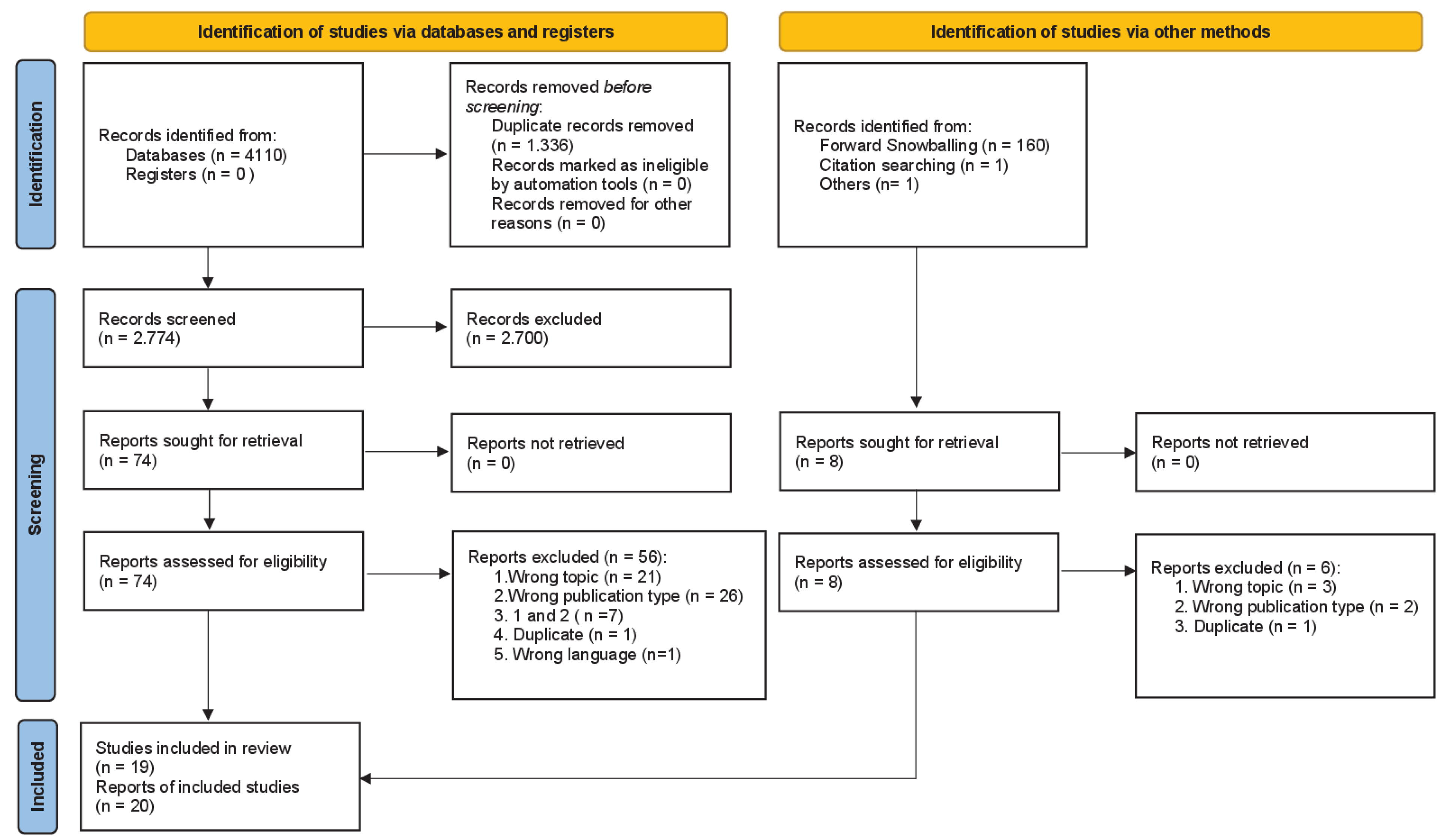

Background/Objectives: Furocoumarins, chemical compounds found in many plant species, have a photosensitizing effect on the skin when topically applied and, in interaction with ultraviolet radiation (UVR), stimulate melanoma cells to proliferate. Whether dietary intake of furocoumarins acts as a melanoma risk factor has been investigated in several epidemiological studies that are synthesized in our systematic review. Methods: The study protocol is registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023428596). We conducted an in-depth literature search in three databases coupled with forward and backward citation tracking and expert consultations to identify all epidemiological studies, irrespective of their design, addressing the association between furocoumarin-containing diet and melanoma risk. We extracted information on the study details and results in a standardized manner and evaluated the risk of bias of the results using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tools. Results: We identified 20 publications based on 19 distinct studies providing information on the furocoumarin-melanoma association. We refrained from a meta-analytical synthesis of the results because of the large heterogeneity in exposure assessment, operationalization of furocoumarin intake in the analyses, and analytical methods of the studies. In a qualitative synthesis, we found moderate evidence supporting the notion that dietary furocoumarin intake at higher levels acts as a risk factor for cutaneous melanoma. Conclusions: Our systematic review provides an overview of the current epidemiological knowledge but could not answer unambiguously whether and, if so, to what extent dietary furocoumarin intake increases melanoma risk. The future epidemiological analysis focusing on this topic requires more comprehensive dietary and UVR exposure data to better characterize the individual total furocoumarin intake and its interplay with individual UVR exposure patterns.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Process

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Furocoumarin Sources in Studies

3.4. Role of UVR Exposure in the Analysis of the Furocoumarin-Melanoma Relationship

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CM | Cutaneous melanoma |

| UV | ultraviolet |

| UVR | Ultraviolet radiation |

References

- Schadendorf, D.; van Akkooi, A.C.J.; Berking, C.; Griewank, K.G.; Gutzmer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Stang, A.; Roesch, A.; Ugurel, S. Melanoma. Lancet 2018, 392, 971-984. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; de Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol 2022, 158, 495-503. [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Keim, U.; Gandini, S.; Amaral, T.; Katalinic, A.; Hollezcek, B.; Martus, P.; Flatz, L.; Leiter, U.; Whiteman, D. Epidemiology of cutaneous melanoma and keratinocyte cancer in white populations 1943-2036. Eur J Cancer 2021, 152, 18-25. [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, S.; Suppa, M.; Gandini, S. Melanoma Epidemiology and Sun Exposure. Acta Derm Venereol 2020, 100, adv00136. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wei, J.; Yang, F.; Qu, Y.; Huang, J.; Shi, D. Nutrient-Based Approaches for Melanoma: Prevention and Therapeutic Insights. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- DeWane, M.E.; Shahriari, N.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Nutrition and melanoma prevention. Clin Dermatol 2022, 40, 186-192. [CrossRef]

- Micek, A.; Godos, J.; Lafranconi, A.; Marranzano, M.; Pajak, A. Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee consumption and melanoma risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2018, 69, 417-426. [CrossRef]

- Vuong, K.; McGeechan, K.; Armstrong, B.K.; Cust, A.E. Risk prediction models for incident primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol 2014, 150, 434-444. [CrossRef]

- Usher-Smith, J.A.; Emery, J.; Kassianos, A.P.; Walter, F.M. Risk prediction models for melanoma: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014, 23, 1450-1463. [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, I.; Pfahlberg, A.B.; Uter, W.; Heppt, M.V.; Veierod, M.B.; Gefeller, O. Risk Prediction Models for Melanoma: A Systematic Review on the Heterogeneity in Model Development and Validation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Sayre, R.M.; Dowdy, J.C. The increase in melanoma: are dietary furocoumarins responsible? Med Hypotheses 2008, 70, 855-859. [CrossRef]

- Melough, M.M.; Cho, E.; Chun, O.K. Furocoumarins: A review of biochemical activities, dietary sources and intake, and potential health risks. Food Chem Toxicol 2018, 113, 99-107. [CrossRef]

- Bellringer, H.E. Phyto-photo-dermatitis. Br Med J 1949, 1, 984-986. [CrossRef]

- Momtaz, K.; Fitzpatrick, T.B. The benefits and risks of long-term PUVA photochemotherapy. Dermatol Clin 1998, 16, 227-234. [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.S.; Nichols, K.T.; Vakeva, L.H. Malignant melanoma in patients treated for psoriasis with methoxsalen (psoralen) and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA). The PUVA Follow-Up Study. N Engl J Med 1997, 336, 1041-1045. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021, 10, 89. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schunemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ Int 2018, 121, 1027-1031. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016, 75, 40-46. [CrossRef]

- Melough, M.M.; Chun, O.K. Dietary furocoumarins and skin cancer: A review of current biological evidence. Food Chem Toxicol 2018, 122, 163-171. [CrossRef]

- Holman, C.D.; Armstrong, B.K.; Heenan, P.J.; Blackwell, J.B.; Cumming, F.J.; English, D.R.; Holland, S.; Kelsall, G.R.; Matz, L.R.; Rouse, I.L.; et al. The causes of malignant melanoma: results from the West Australian Lions Melanoma Research Project. Recent Results Cancer Res 1986, 102, 18-37. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A. The relationship between diet and melanoma in Arizona. University of Arizona, 1992.

- Malavolti, M.; Malagoli, C.; Fiorentini, C.; Longo, C.; Farnetani, F.; Ricci, C.; Albertini, G.; Lanzoni, A.; Reggiani, C.; Virgili, A.; et al. Association between dietary vitamin C and risk of cutaneous melanoma in a population of Northern Italy. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2013, 83, 291-298. [CrossRef]

- Malagoli, C.; Malavolti, M.; Farnetani, F.; Longo, C.; Filippini, T.; Pellacani, G.; Vinceti, M. Food and Beverage Consumption and Melanoma Risk: A Population-Based Case-Control Study in Northern Italy. Nutrients 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Feskanich, D.; Willett, W.C.; Hunter, D.J.; Colditz, G.A. Dietary intakes of vitamins A, C, and E and risk of melanoma in two cohorts of women. Br J Cancer 2003, 88, 1381-1387. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.Y.; Rice, M.S.; Park, M.K.; Chun, O.K.; Melough, M.M.; Nan, H.M.; Willett, W.C.; Li, W.Q.; Qureshi, A.A.; Cho, E.Y. Intake of Furocoumarins and Risk of Skin Cancer in 2 Prospective US Cohort Studies. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1535-1544. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.W.; Han, J.L.; Feskanich, D.; Cho, E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Qureshi, A.A. Citrus Consumption and Risk of Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2500-U2532. [CrossRef]

- Østerlind, A.; Tucker, M.A.; Stone, B.J.; Jensen, O.M. The Danish case-control study of cutaneous malignant melanoma. IV. No association with nutritional factors, alcohol, smoking or hair dyes. International Journal of Cancer 1988, 42, 825-828. [CrossRef]

- Stryker, W.S.; Stampfer, M.J.; Stein, E.V.; Kaplan, L.; Louis, T.A.; Sober, A.; Willett, W.C. Diet, Plasma-Levels of Beta-Carotene and Alpha-Tocopherol and Risk of Malignant-Melanoma. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1988, 128, 889-890.

- Veierød, M.B.; Thelle, D.S.; Laake, P. Diet and risk of cutaneous malignant melanoma: a prospective study of 50,757 Norwegian men and women. Int J Cancer 1997, 71, 600-604. [CrossRef]

- Naldi, L.; Gallus, S.; Tavani, A.; Imberti, G.L.; La Vecchia, C. Risk of melanoma and vitamin A, coffee and alcohol: A case-control study from Italy. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 2004, 13, 503-508. [CrossRef]

- Millen, A.E.; Tucker, M.A.; Hartge, P.; Halpern, A.; Elder, D.E.; Guerry Iv, D.; Holly, E.A.; Sagebiel, R.W.; Potischman, N. Diet and melanoma in a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 2004, 13, 1042-1051.

- Fortes, C.; Mastroeni, S.; Melchi, F.; Pilla, M.A.; Antonelli, G.; Camaioni, D.; Alotto, M.; Pasquini, P. A protective effect of the Mediterranean diet for cutaneous melanoma. Int J Epidemiol 2008, 37, 1018-1029. [CrossRef]

- Vinceti, M.; Bonvicini, F.; Pellacani, G.; Sieri, S.; Malagoli, C.; Giusti, F.; Krogh, V.; Bergomi, M.; Seidenari, S. Food intake and risk of cutaneous melanoma in an Italian population. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008, 62, 1351-1354. [CrossRef]

- Grasgruber, P.; Hrazdira, E.; Sebera, M.; Kalina, T. Cancer Incidence in Europe: An Ecological Analysis of Nutritional and Other Environmental Factors. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 151. [CrossRef]

- Mahamat-Saleh, Y.; Cervenka, I.; Al-Rahmoun, M.; Mancini, F.R.; Severi, G.; Ghiasvand, R.; Veierod, M.B.; Caini, S.; Palli, D.; Botteri, E.; et al. Citrus intake and risk of skin cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort (EPIC). Eur J Epidemiol 2020, 35, 1057-1067. [CrossRef]

- Melough, M.M.; Kim, K.; Cho, E.; Chun, O.K. Relationship between Furocoumarin Intake and Melanoma History among US Adults in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2012. Nutr Cancer 2020, 72, 24-32. [CrossRef]

- Melough, M.M.; Wu, S.W.; Li, W.Q.; Eaton, C.; Nan, H.M.; Snetselaar, L.; Wallace, R.; Qureshi, A.A.; Cho, E.; Chun, O.K. Citrus Consumption and Risk of Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma in the Women's Health Initiative. Nutr. Cancer 2020, 72, 568-575. [CrossRef]

- Marley, A.R.; Li, M.; Champion, V.L.; Song, Y.; Han, J.; Li, X. The association between citrus consumption and melanoma risk in the UK Biobank*. British Journal of Dermatology 2021, 185, 353-362. [CrossRef]

- Melough, M.M.; Sakaki, J.; Liao, L.M.; Sinha, R.; Cho, E.; Chun, O.K. Association between Citrus Consumption and Melanoma Risk in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 1613-1620. [CrossRef]

- Melough, M.M.; Sakaki, J.; Liao, L.D.M.; Sinha, R.; Cho, E.; Chun, O.K. Association between Citrus Consumption and Melanoma Risk in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 1613-1620. [CrossRef]

- Mullen, M.P.; Pathak, M.A.; West, J.D.; Harrist, T.J.; Dall'Acqua, F. Carcinogenic effects of monofunctional and bifunctional furocoumarins. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1984, 66, 205-210.

- Aubin, F.; Donawho, C.K.; Kripke, M.L. Effect of psoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation on in vivo growth of melanoma cells. Cancer Res 1991, 51, 5893-5897.

- Fang, X.; Han, D.; Yang, J.; Li, F.; Sui, X. Citrus Consumption and Risk of Melanoma: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 904957. [CrossRef]

- Melough, M.M.; Lee, S.G.; Cho, E.; Kim, K.; Provatas, A.A.; Perkins, C.; Park, M.K.; Qureshi, A.; Chun, O.K. Identification and Quantitation of Furocoumarins in Popularly Consumed Foods in the U.S. Using QuEChERS Extraction Coupled with UPLC-MS/MS Analysis. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 5049-5055. [CrossRef]

- Lauharanta, J.; Juvakoski, T.; Kanerva, L.; Lassus, A. Pharmacokinetics of 8-methoxypsoralen in serum and suction blister fluid. Arch Dermatol Res 1982, 273, 111-114. [CrossRef]

- Tegeder, I.; Brautigam, L.; Podda, M.; Meier, S.; Kaufmann, R.; Geisslinger, G.; Grundmann-Kollmann, M. Time course of 8-methoxypsoralen concentrations in skin and plasma after topical (bath and cream) and oral administration of 8-methoxypsoralen. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002, 71, 153-161. [CrossRef]

| Aspect | Eligibility criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Animal studies were excluded. No further restrictions regarding human study populations. |

| Exposure | Consumption of furocoumarin-containing foods: fig, carrot, parsley, turnip, celery, parsley, dill, coriander, cumin, citrus fruits (lemon, lime, grapefruit, orange or tangerines (mandarin and clementine)) and drinks containing furocoumarin (carrot juice, orange juice, lemon juice, lime juice and grapefruit juice). |

| Comparison | Other human population with different exposure level |

| Outcome | Development of cutaneous melanoma |

| Study design | Observational studies i.e. cohort studies, case-cohort studies, (nested) case-control studies, analytical cross-sectional studies, ecological studies |

| First author of publication and reference | Recruiting period |

Country | Study type | Sample size (cases) | Foods and food combinations investigated | ROB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holman [20] | January 1980 - November 1981 | Australia | case-control | 1,022 (511) | carrot | low |

| Østerlind [27] | 1982 - 1985 | Denmark | case-control | 1,400 (474) | carrot | low |

| Stryker [28] | July 1982 - August 1985 | USA | case-control | 452 (204) | carrot | low |

| Soliman [21] | February 1987 - January 1992 | USA | case-control | 873 (261) | grapefruit†, carrot, orange juice, orange | low / high† |

| Veierød [29] | 1977 - 1983 | Norway | cohort | 50,757 (108) | orange | low |

| Feskanich [24] | 1980 - 1998 | USA | cohort | 162,078 (414) | orange juice | low |

| Naldi [30] | 1992 - 1994 | Italy | case-control | 1,080 (542) | carrot | low |

| Millen [31] | 1991 - 1992 | USA | case-control | 1,058 (497) | citrus fruits and juices | high |

| Fortes [32] | May 2001 - May 2003 | Italy | case-control | 609 (304) | citrus fruits (orange, mandarine), parsley, carrot | low |

| Vinceti [33] | not reported | Italy | case-control | 118 (59) | citrus fruits | low |

| Malavolti‡ [22] | 2005 - 2006 | Italy | case-control | 1,099 (380) | tangerine, orange and grapefruit, orange juice and grapefruit juice | low |

| Wu* [26] | NHS 1984 -1998, HPFS 1986 -1998 | USA | cohort | 105,432 (1,840) | citrus fruits and juices (grapefruit, grapefruit juice, orange, orange juice), grapefruit, grapefruit juice, orange, orange juice | low |

| Grasgruber [34] | 1993 - 2011 | Europe | ecological | -§ | orange and mandarine | high |

| Malagoli‡ [23] | 2005 - 2006 | Italy | case-control | 1,099 (380) | citrus fruits | low |

| Mahamat-Saleh* [35] | 1992 - 2000 | Europe | cohort | 270,112 (1,371) | citrus fruits and juices, citrus fruits, citrus juices | low |

| Sun* [25] | NHS 1984 - 1998, HPFS 1986 - 1998 | USA | cohort | 122,744 (1,593) | total furocoumarin consumption | low |

| Melough* [36] | 2003 - 2012 | USA | cross sectional | 11,696 (75) | total furocoumarin consumption | high |

| Melough* [37] | 1993 - 1998 | USA | cohort | 56,205 (956) | citrus fruits and juices (orange, grapefruit, tangerine, orange juice, grapefruit juice), citrus fruits (orange, grapefruit, tangerine), citrus juices (orange juice, grapefruit juice) | low |

| Marley* [38] | 2006 - 2010 | UK | cohort | 198,964 (1,592) | citrus fruits and juices (grapefruit, grapefruit juice, mandarine, orange, orange juice), grapefruit, grapefruit juice, mandarine, orange, orange juice | unclear |

| Melough* [39] | 1995 - 1996 | USA | cohort | 388,467 (3,894) | citrus fruits and juices (grapefruits, orange, tangerine, tangelo, orange and grapefruit juice), citrus fruits (grapefruits, orange, tangerine, tangelo), citrus juices (orange and grapefruit juice), grapefruit, orange/tangerine/tangelo | low |

| N (n)* | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of study | ||

| case-control studies | 9 (0) | 47.4 |

| cohort studies | 8 (6) | 42.1 |

| cross-sectional studies | 1 (1) | 5.3 |

| ecological studies | 1 (0) | 5.3 |

| Geographic region | ||

| USA | 9 (5) | 47.4 |

| Italy | 4 (0) | 21.1 |

| Europe | 2 (1) | 10.5 |

| Australia | 1 (0) | 5.3 |

| Denmark | 1 (0) | 5.3 |

| Norway | 1 (0) | 5.3 |

| UK | 1 (1) | 5.3 |

| Publication period† | ||

| before 1990 | 3 (0) | 15.0 |

| 1990 - 1999 | 2 (0) | 10.0 |

| 2000 - 2009 | 5 (0) | 25.0 |

| 2010 - 2019 | 4 (1) | 20.0 |

| 2020 and later | 6 (6) | 30.0 |

| Publications | Association | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | n (nsig) | |||||

| Furocoumarin food/beverage category | + | o | - | |||

| Citrus fruits and juices | 6 | 3 (2) | 2 | 1 (0) | ||

| Citrus fruits | 6 | 2 (1) | 3 | 1 (1) | ||

| Citrus juices | 3 | 1 (0) | 2 | |||

| Grapefruit and grapefruit juice | ||||||

| Grapefruit | 4 | 3 (1) | 1 | |||

| Grapefruit juice | 2 | 1 (0) | 1 | |||

| Oranges and orange juice | ||||||

| Orange | 4 | 1 (1) | 3 | |||

| Orange juice | 5 | 3 (3) | 2 | |||

| Other citrus fruits | ||||||

| Orange, tangerine, tangelo | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Mandarine | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Orange and grapefruit | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Orange and mandarine | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Orange juice and grapefruit juice | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Tangerine | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Others | ||||||

| Parsley | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Carrot | 6 | 4 | 2 (2) | |||

| Total furocoumarin consumption | 2 | 2 (0) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).