1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of degenerative dementia in late life and represents a global public health priority. This public health emergency stems from the sharp global increase in the population aged 65 and older. According to epidemiological projections, the number of people with AD is estimated to increase to 131.5 million by 2050 [

1]. According to more recent data, the number of people living with dementia globally is projected to rise from 57.4 million in 2019 to 152.8 million (range: 130.8–175.9 million) by 2050 [

2]. This information not only highlights the significant impact on global public health costs, but also underscores the pressing need to explore strategies for preventing these diseases. AD follows a prolonged, progressive disease course that begins with pathophysiological changes in the brains of affected individuals’ years before any clinical manifestations are observed [

3]. These pathophysiological changes include the accumulation of toxic species of amyloid-β (Aβ), the development of neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein, and neurodegeneration [

4]. The typical form of AD presents insidious with hippocampal memory deficit. As AD progresses, additional neuropsychiatric symptoms may manifest, including periods of confusion, disorientation, mood change, aggression/agitation, and eventually delusion/hallucination in later stages [

5]. The International Working Group (IWG) proposed three stages of AD: (1) the asymptomatic at-risk stage of AD (AD pathology evidenced by biomarkers and no symptoms), (2) prodromal AD (episodic memory deficit with impaired cued recall that can be isolated or in association with other cognitive changes and biomarker evidence for AD), and (3) AD dementia (dementia and biomarker evidence for AD). In addition, these stages were further defined in 2011. In fact, 2011 National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) guidelines defined three phases of AD: preclinical AD (early pathologic changes in the brains of cognitively normal individuals), Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD (symptomatic predementia), and dementia [

6,

7,

8].

Another category includes individuals who report cognitive function alterations without a loss of autonomy, despite the absence of detectable deficits in neuropsychological tests. This entity was characterized and categorized in 2014 when the term subjective cognitive decline (SCD) was coined. SCD has received increasing attention due to evidence of its association with an increased risk of future objective cognitive decline [

9,

10].

The main objectives of the clinical scientific community are to identify preclinical biomarkers of AD and to investigate strategies for identifying and modulating risk and protective factors.

The vast majority of people who develop Alzheimer’s dementia are aged 65 or older, a condition referred to as late-onset AD (LOAD). Alzheimer’s, like other common chronic diseases, develops as a result of multiple factors rather than a single cause. However, exceptions exist in cases of AD due to mutations in disease-causing genes (APP, PSN1 and PSN2).

The main non-modifiable and well-studied risk factors for LOAD are advanced age [

11], the presence of genetic variations, such as the epsilon 4 form of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene [

12,

13] and a positive family history of AD [

14].

Modifiable risk factors have been the focus of discussions by the scientific community as the idea is that by modifying risk factors it is also possible to modify the onset of this disease [

15,

16]. An important concept to keep in mind is that reducing risk does not prevent cognitive decline but may slow down its onset. Among the modifiable risk factors for dementia are cerebrovascular disease and related diseases. Diabetes, high blood pressure, smoking, obesity and hypercholesterolemia not only contribute to the genesis of cerebrovascular disease, but also to the risk of dementia. The mechanisms by which these factors correlate with dementia are not fully understood [

17,

18,

19,

20].

The aim of this door-to-door epidemiological work is to bring to light the percentage of subjects in a population of over-60s, who already have a cognitive deficit, even if unrecognized, and on the other hand to highlight the role of any lifestyles favorable to the development of dementia. The population chosen is that of the municipality of Comiziano. This choice is dictated by the fact that Comiziano is an Italian municipality of 1758 inhabitants in the metropolitan city of Naples in Campania, with an agricultural vocation, without particular housing flows in recent decades that lends itself well to an epidemiological study of communities.

The primary outcomes are:

The secondary outcome is to calculate the prevalence of cognitive decline within the population.

2. Materials and Methods

The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of ASL Napoli 3 Sud (Coordination Service of the Campania Sud Ethics Committee, nr.38), and all patients have signed informed consent for the processing of data according to current legislation. The inclusion criteria were age ≥ 60 years and individuals who had not already received a diagnosis of dementia. A total of 206 participants were recruited from 502 individuals over 60 years old (11 deceased, 20 already diagnosed with dementia were excluded, and 265 refused). Demographic and clinical data were collected (age, gender, education level, body mass index (BMI), presence of comorbidities, weight loss in the last six months).

The inhabitants were assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a global cognitive screening test with 87% specificity and 90% sensitivity. According to MCIand, sensitivity reaches 100% when considering mild AD. [

21] The data establish that it has excellent test-retest reliability and positive and negative predictive values for MCI and AD. It is highly sensitive to the presence of MCI and is practical for use in clinical settings, where assessment time is often limited. Therefore, it is preferred for detecting early stages of the cognitive decline spectrum, whereas the MMSE is considered superior to the MoCA in assessing more advanced stages. [

21] The final version of the MoCA is a 30-point test. The domains explored were: visuospatial functions, assessed through the clock-drawing task and a three-dimensional cube copy; executive functions, evaluated using a shortened version of the Trail Making B task, phonemic fluency, verbal abstraction, and the clock-drawing task; short- and long-term memory (immediate and delayed recall of five words); attention, concentration, and working memory, assessed through a sustained attention task, calculation task, and digits forward and backward; language, evaluated using a naming task and the repetition of two syntactically complex sentences; and finally, orientation to time and place was also assessed. [

21]

Cognitive reserve was analysed using CRIq. This test provides a standardised and psychometrically controlled measure of cognitive reserve, making it widely applicable in both experimental research and clinical practice. It is also an efficient and reliable tool for measuring cognitive reserve, as it requires minimal time to administer. While CR and intelligence are undoubtedly correlated, their focuses differ. Intelligence primarily concerns action and behaviour, described as "adaptive behaviour directed towards a goal." In contrast, cognitive reserve is centered on the accumulation of resources—the potential cognitive abilities acquired throughout life. The questionnaire comprises 20 items grouped into three sections: education, work activity, and leisure time, each generating a subscore. The CRIq questionnaire (available in Italian, French, and English), along with instructions and an Excel file for automatic score calculation, are provided.

CRI-Education (CRI-E): years of formal education plus any relevant training courses (lasting at least six months). CRI-Working Activity (CRI-W): adult professions, categorised into five levels.

CRI-Leisure-time (CRI-L): cognitively stimulating activities carried out during leisure time, categorized by weekly, monthly, or annual frequency. [

22]

The MoCA was administered to all the inhabitants of Comiziano and was corrected for age and education level in accordance with the standardisation for the Italian population as reported in the literature. [

23] Cutoff: MoCA: normal >17.54; borderline 17.54-15.5; impaired <15.5.

Cognitive reserve (CR) was then measured using the Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire. [

22] Cutoff CRIq: low <70; medium-low 70-84; medium 85-114; medium-high 115-130; high >130). [

22]

The continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while the qualitative variables were presented as numbers and percentages. The association between cognitive reserve and cognitive decline was studied using parametric statistics (Student’s t-test for independent samples) and non-parametric statistics (Mann Whitney test). All tests were two-tailed. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The χ² association test was performed for the qualitative variables.

3. Results

3.1. Results and Statistical Analysis

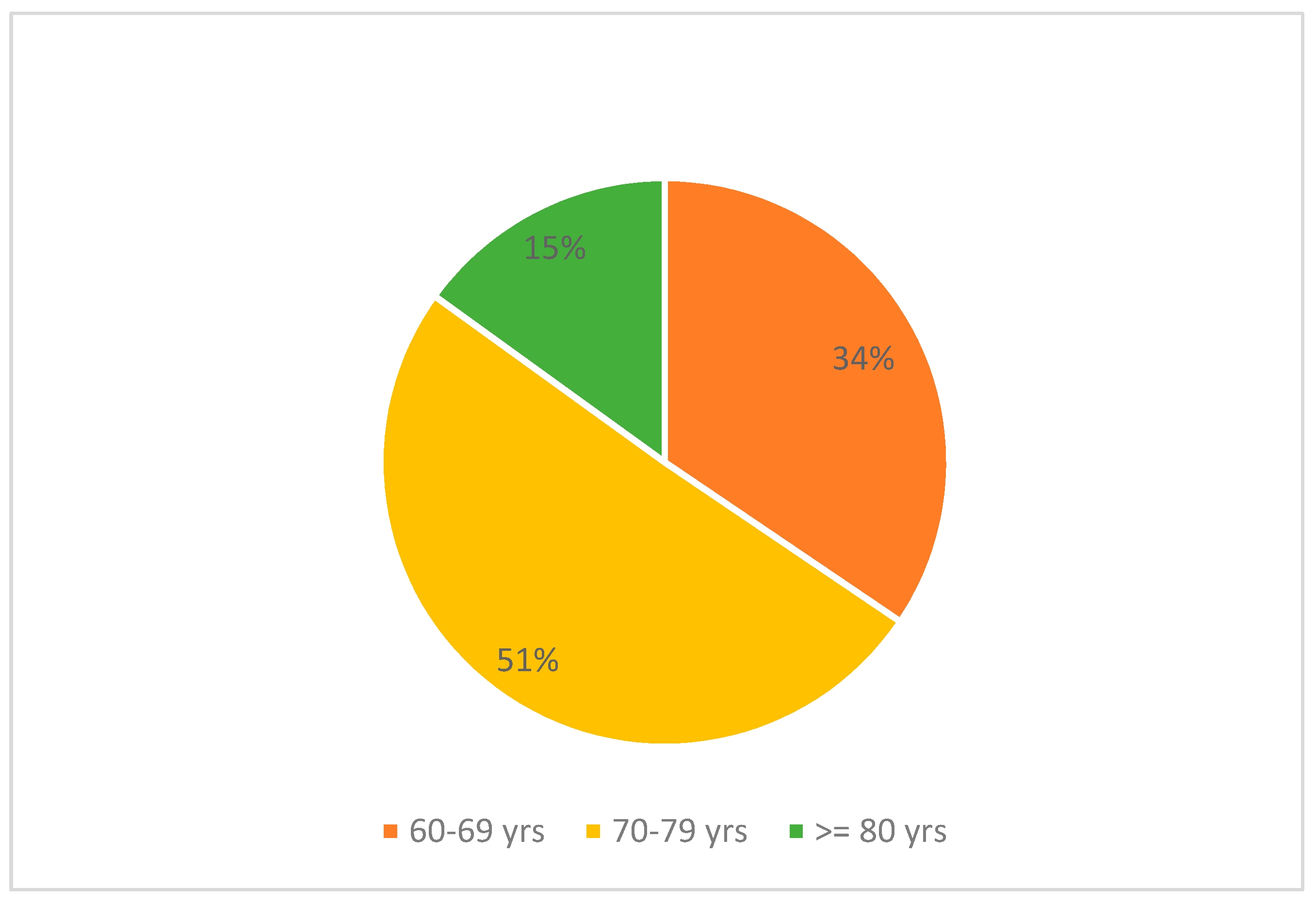

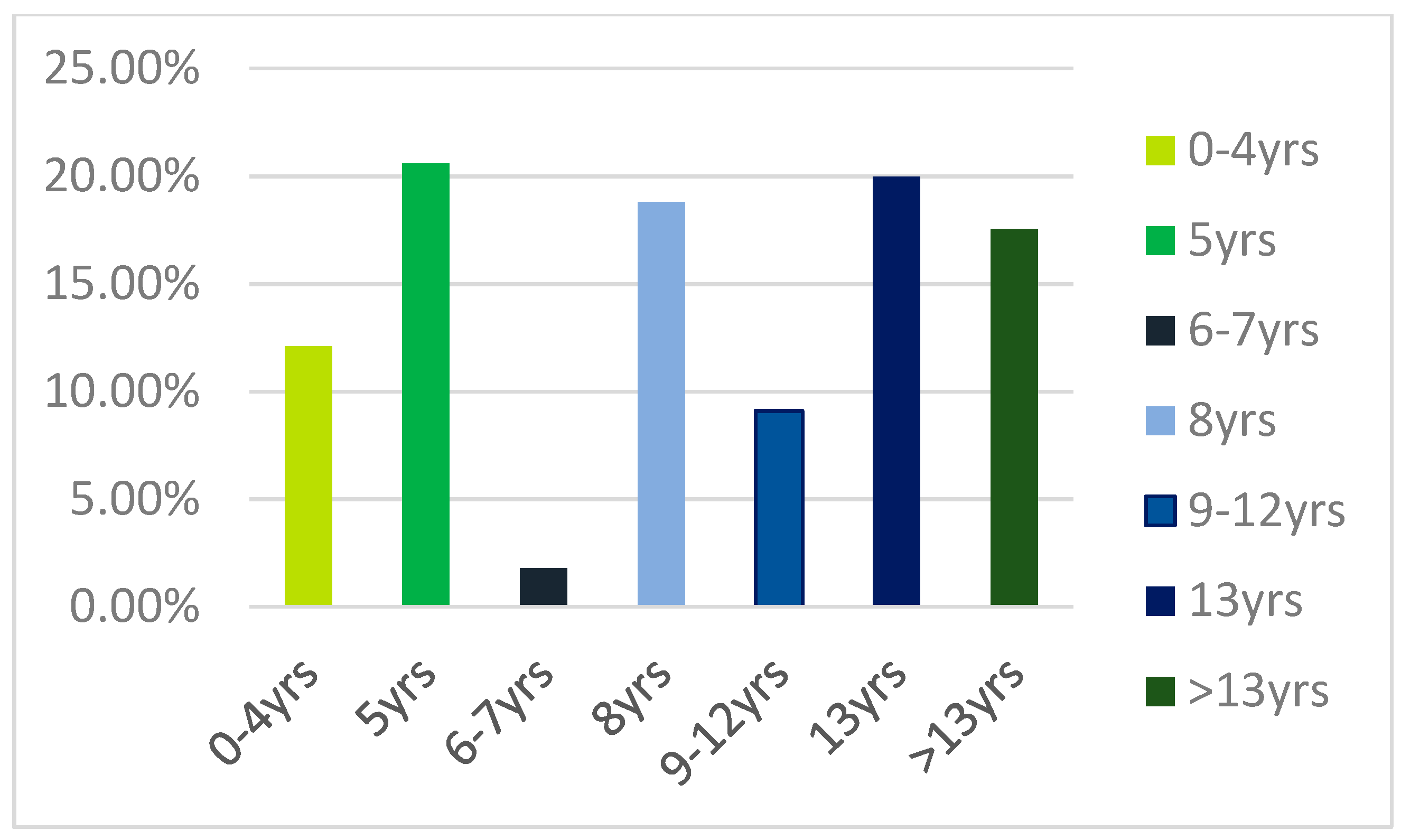

We recruited 206 individuals over the age of 60, of whom 51.9% were women. The average age of the participants was 72 ± 6.77 years (

Figure 1), and the average level of education was 9.45 ± 4.85 years (

Figure 2). The average BMI was 27.7 ± 4.22 kg/m²; 36.4% reported having lost weight in the over the past six months. 10.7% felt they had a cognitive deficit. 83% of the participants had comorbidities (

Table 1;

Table 2). The average score on the MoCA, corrected for age and education, was 21.7 ± 3.57. The mean total CRIq score was 93.9 ± 18.8. (

Table 3)

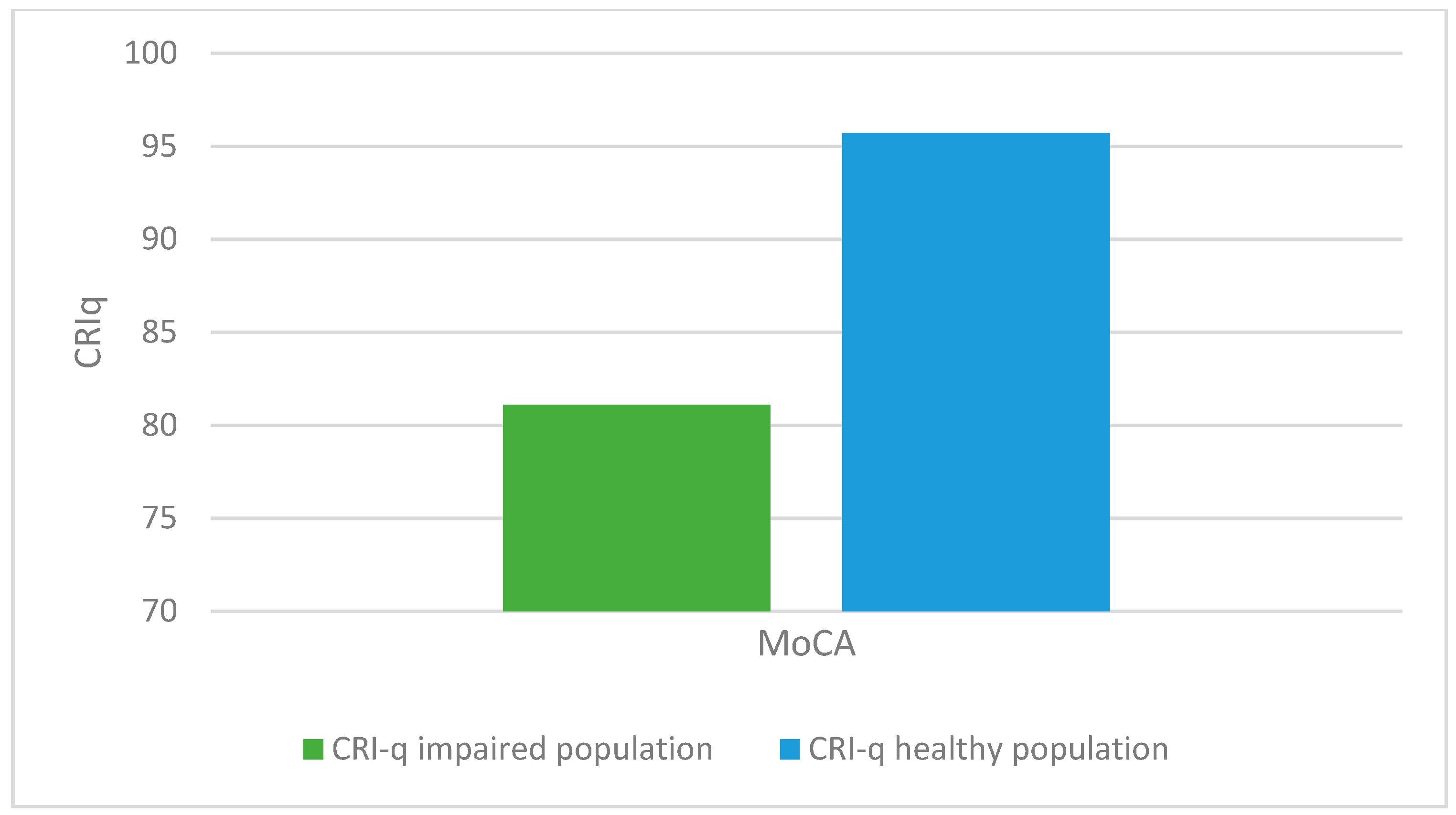

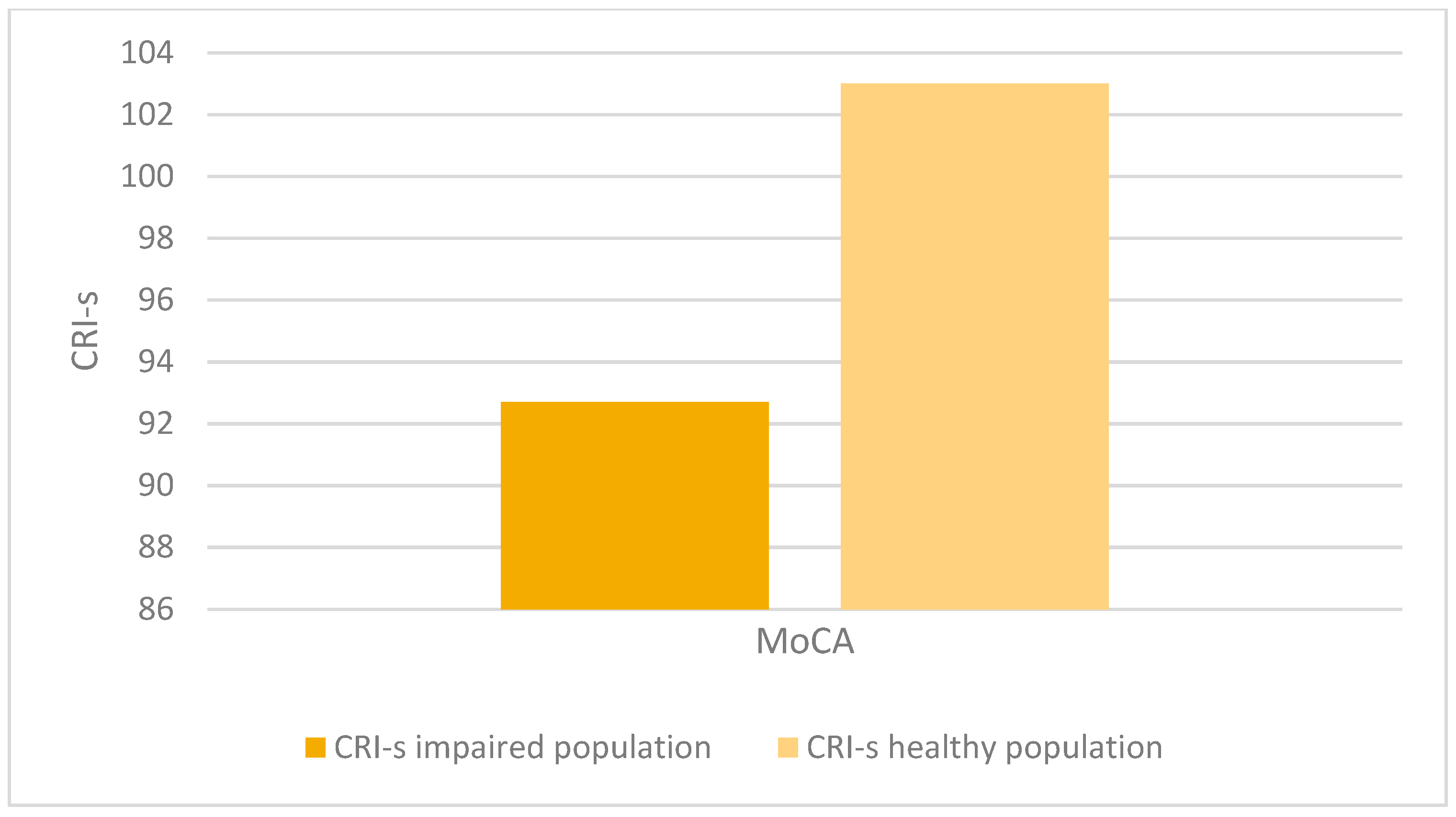

We considered two populations: one with a normal MoCA score corrected for age and education (>17.54) and another that includes both the altered MoCA (<15.5) and borderline MoCA (15.5–17.54), as the latter also require further in-depth testing.

Twenty-six out of 206 (12.6%) subjects had an impaired or borderline MoCA, corrected for age and education.

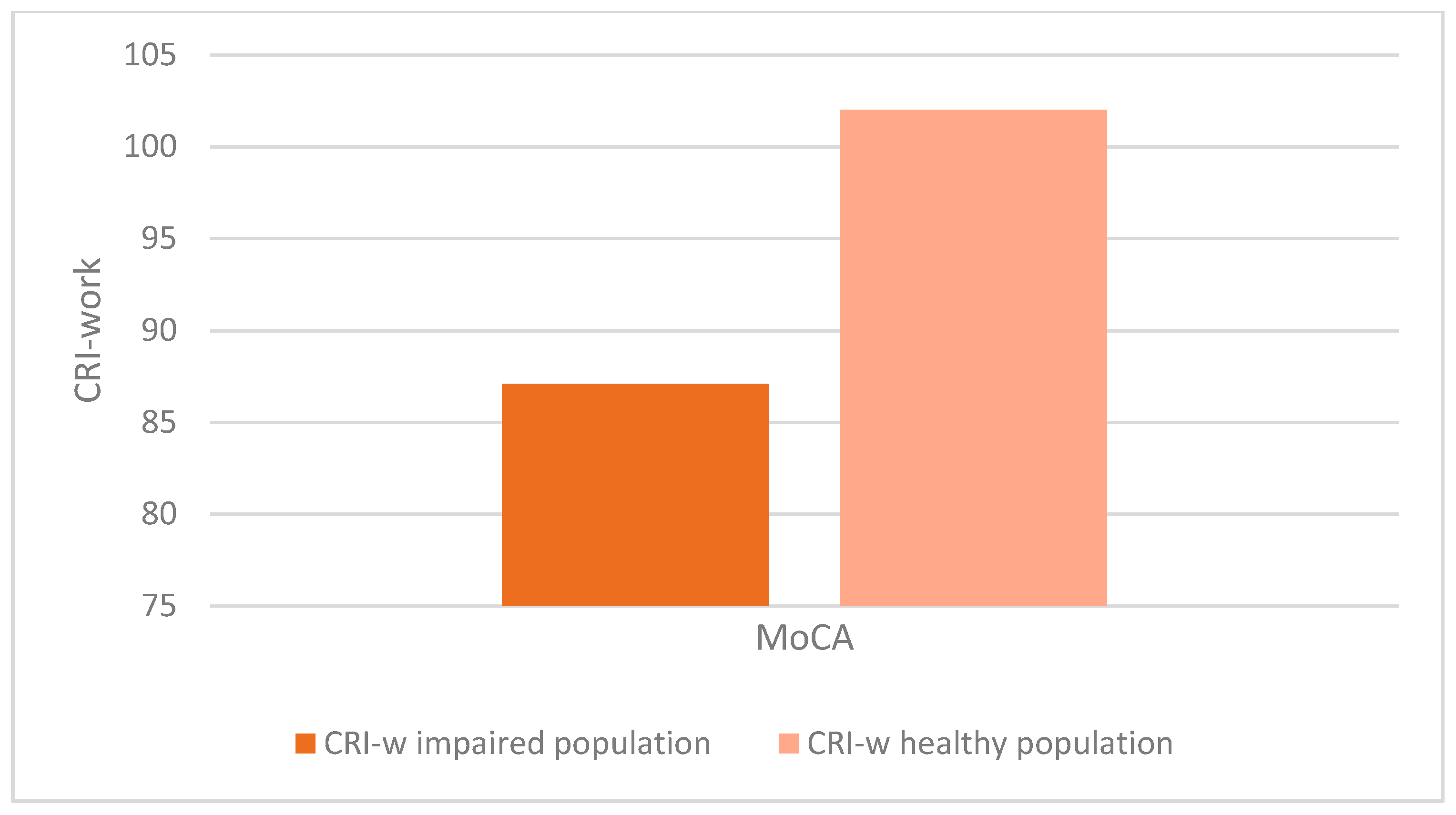

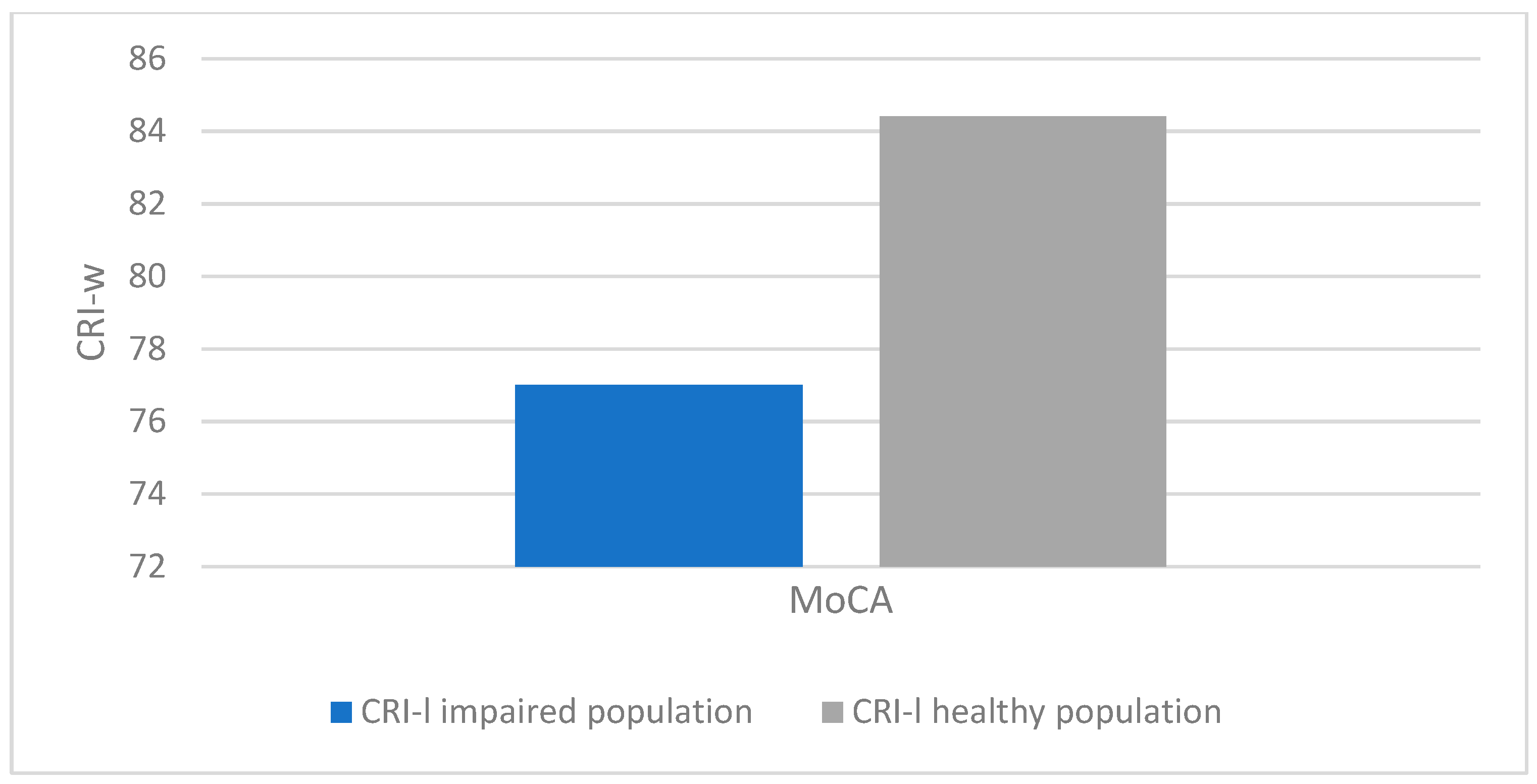

There was a statistically significant association between altered MoCA scores (corrected for age and education) and lower CRIq scores (impaired population: µ = 81.1; σ = 15.5; healthy population: µ = 95.7; σ = 18.5; p < 0.001), which was also confirmed in CRI items: School (impaired population: µ = 92.7; σ = 11.5; healthy population: µ = 102.6; σ = 14.5; p < 0.003), Work (impaired population: µ = 87.1; σ = 16.2; healthy population: µ = 102.1; σ = 24.5; p < 0.008), Leisure-time (impaired population: µ = 77; σ = 15.2; healthy population: µ = 84.4; σ = 13.7; p < 0.03), as confirmed by the Kruskal-Wallis test (

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Regarding the factors associated with cognitive decline, there was a statistically significant association between older age and impairment in MoCA scores corrected for age and education (impaired population: µ = 75.08; σ = 7.15; healthy population: µ = 71.59; σ = 6.62; p < 0.014).

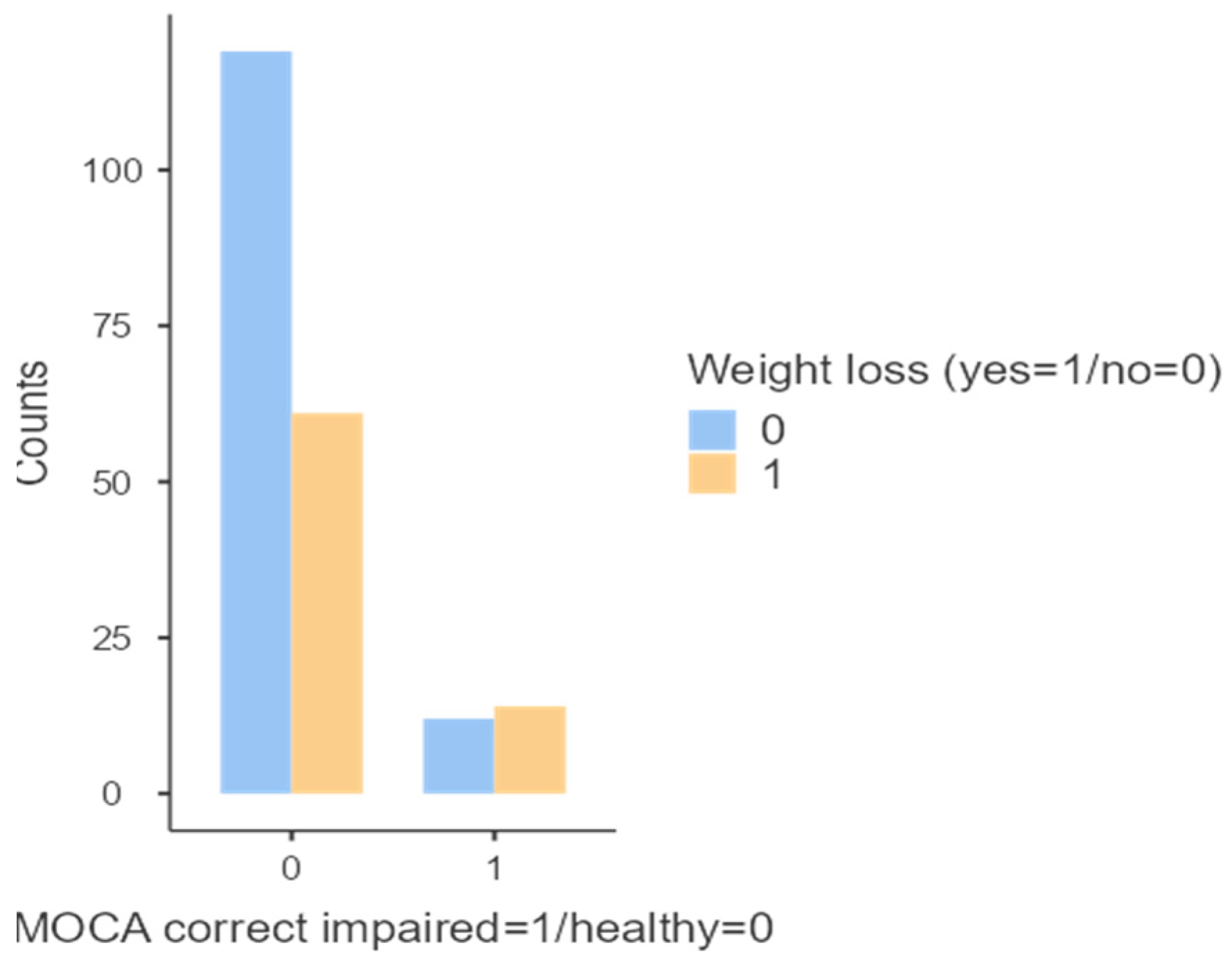

Additionally, a statistically significant association was found between altered MoCA scores, corrected for age and education, and weight loss over the past six months (p < 0.048;

Figure 7).

No significant differences were observed in BMI (p = 0.680) or between genders (p = 0.142) (

Table 4).

No significant differences were found regarding the presence (p = 0.371) or type of comorbidities between the two populations (Normal MoCA corrected for age and education / altered and borderline MoCA). (

Table 5)

A statistically significant association was found between altered MoCA scores and the perception of cognitive deficit (p < 0.029).

The prevalence of individuals with impaired or borderline MoCA scores in the total population was 12.6% (26/206).

4. Discussion

This study provides insights into the prevalence and characteristics of cognitive decline in an aging population within the rural municipality of Comiziano. Using cognitive assessments like the MoCA and CRIq, we identified a significant proportion of individuals with impaired or borderline cognitive function. The findings highlight important differences between people with cognitive impairment and those without, particularly in relation to cognitive reserve, age, and recent weight loss. These results are consistent with existing literature on the interplay between modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for dementia, offering a localized perspective that contributes to the broader understanding of cognitive decline in older adults.

The concept of CR has been proposed to explain individual differences in susceptibility to age-related brain changes and pathological conditions such as AD. The original concept of brain reserve (BR) was primarily quantitative, referring to factors such as having more neurons or synapses to lose. In contrast, CR suggests that the brain actively attempts to compensate for damage by using pre-existing cognitive strategies or by adopting compensatory mechanisms. BR and CR therefore appear to make independent yet synergistic contributions, which may explain the varying resilience to neurodegenerative diseases. However, it remains unclear how these two components interact with each other. [

24]

The CR accumulated by individuals with high cognitive reserve throughout their lives results in changes in local grey matter, reflecting the rich neuroplastic properties developed under conditions of cognitive stimulation. These mechanisms have already been demonstrated in animal models. For instance, it has been shown that exposure to an enriched environment induces an increase in neurogenesis and brain volume in mice. [

25] Moreover, it has been shown that behavioural stimulation increases neuroplasticity in the hippocampus of transgenic mice affected by AD. [

26]

For individuals with higher CR, the onset of cognitive decline occurs later compared to those with lower CR. However, once AD manifests, individuals with higher reserves tend to experience a more rapid decline, as their cognitive deterioration begins when the disease is already at a more advanced stage. Epidemiological studies suggest that, at any level of clinical severity of AD, an individual with a higher level of CR is likely to have a greater extent of AD pathology. [

24] In our study, cognitive reserve was associated with differences in cognitive performance between groups. These differences were observed across three fundamental aspects of an individual

’s life: education, work, and leisure time.

Advanced age remains a significant risk factor, even in our rural community. With ageing, the brain undergoes various structural and functional changes, the most evident being a gradual reduction in brain volume, accompanied by an increase in ventricular space and cerebrospinal fluid.

Additionally, there may be a decline in the integrity of white matter during ageing, which can compromise the transfer of information between cortical regions—a process essential for higher cognitive function. Furthermore, the ageing of the microbiota-gut-brain axis may also play a role in cognitive health and the development of disease. [

27]

In our study, weight loss was identified as associated with the development of cognitive deficits. Longitudinal cohort studies have observed that obesity or a high BMI at age 65 or older is associated with a reduced risk of dementia, leading to the emergence of the concept known as the "obesity paradox." [

28]

Protective effects of excess adipose tissue on the risk of dementia in the elderly population have been suggested. For instance, studies have shown that the adipokine leptin exerts neuroprotective effects by preventing neuronal death and improving cognitive performance in rodents.

Higher levels of leptin have been associated with a lower risk of dementia and AD, possibly due to its role in regulating synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and amyloid processing. [

29] In postmenopausal women, adipose tissue serves as the primary source of estrogen, which has been linked to brain health. [

30] Moreover, longitudinal cohort studies have shown that weight loss often begins 6–10 years before a dementia diagnosis, suggesting that weight loss may serve as a prodromal sign of dementia. [

28]

Several epidemiological studies have investigated the prevalence of dementia in the general population, particularly in industrialized urban areas. In contrast, fewer studies have focused on the prevalence of dementia in rural populations, often yielding conflicting results.

For example, an epidemiological study conducted among 1,181 inhabitants in northern rural China found that 127 individuals developed dementia over five years: 75 with AD and 32 with vascular dementia (VaD). The incidence of dementia was estimated at 22.48 per 1,000 person-years, and 13.2 per 1,000 person-years for AD across the total sample, figures higher than those reported in previous studies. Increased age was associated with a higher risk of dementia and AD incidence. Additionally, low education levels were linked to an increased risk of VaD and AD. A history of stroke was identified as a risk factor for the incidence of VaD, but not for AD. Moreover, engagement in social activities was observed to be a protective factor against vascular dementia. [

31]

Another study conducted in San Teodoro, a rural village in central Sicily with 1,500 inhabitants, examined the prevalence of dementia in 374 elderly individuals aged between 60 and 85 years. The prevalence of dementia was 7.1% (20 individuals, 8 males and 12 females), with 60% diagnosed with Alzheimer

’s disease and 15% with vascular dementia—a figure slightly higher than the average observed in European countries (6%). The high prevalence of hypertension (80.3%) and low levels of education, two well-known risk factors for dementia, could partially explain this observed difference. [

32]

In our homogeneous community, a low prevalence of cognitive decline was observed, with cognitive reserve playing an important protective role, while advanced age, weight loss, and subjective cognitive deficit were identified as risk factors. Additionally, a low prevalence of cognitive deficits emerged, which may be associated with the habits and lifestyle of the inhabitants. The main aim of this study was to investigate, from an epidemiological perspective, a small rural community without migratory flows, which could influence the impact of cognitive disorders. Consequently, the primary limitation of the study is that cognitive deficits were not contextualised in relation to their underlying pathogenic basis. Nonetheless, the primary objective was to assess the impact of cognitive reserve and risk factors on the occurrence of cognitive function deficits, regardless of their underlying cause, in this specific community.

Moreover, other limitations of our study stem from the lack of additional data regarding the specific characteristics of cognitive deficits and the number of tests used to assess them. Further in-depth assessments, along with additional laboratory and instrumental data, would be valuable for a more detailed characterisation and accurate diagnosis of cognitive deficits, which were identified in 12.6% of the population of Comiziano.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, due to the socio-economic impact of neurodegenerative diseases, it is crucial to focus on the prevention of modifiable risk factors. The results of our study highlight that cognitive reserve may represent a factor in modulating cognitive decline, emphasising the important role of social activities carried out throughout life. This finding becomes even more evident when considering a population such as the one we studied, namely a small rural community with no migration flows.

Finally, another interesting point is that in a community like Comiziano, there is a low incidence of cognitive alterations. This latter observation is closely related to the recognised risk factors, including, primarily, the lifestyle that can influence the development of dementia.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, P.A.; methodology, C.C. and P.A.; formal analysis, E.S. and D.A.; investigation, R.C and D.A.; resources, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C. and D.A.; writing—review and editing, C.C.; supervision, G.A. and S.B.; project administration, M.R. and S.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of ASL Napoli 3 Sud (Coordination Service of the Campania Sud Ethics Committee, nr.38 on 7th March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Ainat Onlus, Ageas Onlus, Municipality of Comiziano.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| SCD |

Subjective cognitive decline |

| MCI |

Mild cognitive impairment |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| MMSE |

Mini Mental State Examination |

| CR |

Cognitive reserve |

| CRIq |

Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire |

| CRI-E |

Cognitive Reserve Index Education |

| CRI-W |

Cognitive Reserve Index Work |

| CRI-L |

Cognitive Reserve Index Leisure |

| BR |

Brain reserve |

| Vad |

Vascular dementia |

References

- Cummings J, Aisen PS, DuBois B, et al. Drug development in Alzheimer’s disease: the path to 2025. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016; 8:39. Published 2016 Sep 20. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022; 7(2): E105-E125. [CrossRef]

- Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’s disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207–216. [CrossRef]

- Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):505-517. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, Bruno et al. “Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria.” The Lancet. Neurology vol. 13,6 (2014): 614-29. [CrossRef]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(8):734-746. [CrossRef]

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Revising the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1118-1127. [CrossRef]

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263-269. [CrossRef]

- Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):844-852. [CrossRef]

- Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Buckley RF, et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(3):271-278. [CrossRef]

- National Institute on Aging. What causes Alzheimer’s disease. Avail- able at: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what- causes- Alzheimers- disease. Accessed December 18, 2021; 2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2022; 18(4):700-789. [CrossRef]

- Mayeux R, Saunders AM, Shea S, et al. Utility of the apolipoprotein E genotype in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Disease Centers Consortium on Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s Disease [published correction appears in N Engl J Med 1998 Apr 30; 338(18):1325]. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338(8):506-511. [CrossRef]

- Loy CT, Schofield PR, Turner AM, Kwok JB. Genetics of dementia. Lancet. 2014; 383(9919):828-840. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60630-3; Allwright M, Mundell HD, McCorkindale AN, et al. Ranking the risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease; findings from the UK Biobank study. Aging Brain. 2023; 3:100081. Published 2023 Jun 17. [CrossRef]

- Wolters FJ, van der Lee SJ, Koudstaal PJ, et al. Parental family history of dementia in relation to subclinical brain disease and dementia risk. Neurology. 2017; 88(17):1642-1649. [CrossRef]

- Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019; Baumgart M, Snyder HM, Carrillo MC, Fazio S, Kim H, Johns H. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: A population-based perspective. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(6):718-726. [CrossRef]

- Blazer DG, Yaffe K, Liverman CT, Committee on the Public Health Dimensions of Cognitive Aging; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine, eds. Cognitive Aging: Progress in Understanding and Opportunities for Action. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); July 21, 2015. N: Washington (DC).

- Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Gamaldo AA, Teel A, Zonderman AB, Wang Y. Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14:643. Published 2014 Jun 24. [CrossRef]

- Lewis CR, Talboom JS, De Both MD, et al. Smoking is associated with impaired verbal learning and memory performance in women more than men. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10248. Published 2021 May 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-88923-z; Arnold SE, Arvanitakis Z, Macauley-Rambach SL, et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(3):168-181. [CrossRef]

- Gottesman RF, Schneider AL, Zhou Y, et al. Association Between Midlife Vascular Risk Factors and Estimated Brain Amyloid Deposition. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1443-1450. [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki M, Luukkonen R, Batty GD, et al. Body mass index and risk of dementia: Analysis of individual-level data from 1.3 million individuals. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(5):601-609. [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 Apr;53(4):695-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221. x. Erratum in: J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019 Sep;67(9):1991. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucci M, Mapelli D, Mondini S. Cognitive Reserve Index questionnaire (CRIq): a new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012 Jun;24(3):218-26. Epub 2011 Jun 20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santangelo G, Siciliano M, Pedone R, Vitale C, Falco F, Bisogno R, Siano P, Barone P, Grossi D, Santangelo F, Trojano L. Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in an Italian population sample. Neurol Sci. 2015 Apr;36(4):585-91. Epub 2014 Nov 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012 Nov;11(11):1006-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Serra L, Cercignani M, Petrosini L, Basile B, Perri R, Fadda L, Spanò B, Marra C, Giubilei F, Carlesimo GA, Caltagirone C, Bozzali M. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive reserve in Alzheimer disease. Rejuvenation Res. 2011 Apr;14(2):143-51. Epub 2011 Jan 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herring A, Ambrée O, Tomm M, Habermann H, Sachser N, Paulus W, Keyvani K. Environmental enrichment enhances cellular plasticity in transgenic mice with Alzheimer-like pathology. Exp Neurol. 2009 Mar;216(1):184-92. Epub 2008 Dec 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell E, Le Gall G, Pontifex MG, Sami S, Cryan JF, Clarke G, Müller M, Vauzour D. Microbial-derived metabolites as a risk factor of age-related cognitive decline and dementia. Mol Neurodegener. 2022 Jun 17;17(1):43. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim KY, Ha J, Lee JY, Kim E. Weight loss and risk of dementia in individuals with versus without obesity. Alzheimers Dement. 2023 Dec;19(12):5471-5481. Epub 2023 May 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmerzaal TL, Kiliaan AJ, Gustafson DR. 2003-2013: a decade of body mass index, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(3):739-55. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooldijk SS, de Crom TOE, Ikram MK, Ikram MA, Voortman T. Adiposity in the older population and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2023 May;19(5):2047-2055. Epub 2022 Nov 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu X, Shi Z, Liu S, Guan Y, Lu H, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Liu S, Yue W, Wu H, Wang X, Zhang Y, Ji Y. Incidence and risk factors of dementia and the primary subtypes in northern rural China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Apr 2;100(13):e25343. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spada RS, Stella G, Calabrese S, Bosco P, Anello G, Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Benamghar L, Guéant JL. Prevalence of dementia in mountainous village of Sicily. J Neurol Sci. 2009 Aug 15;283(1-2):62-5. Epub 2009 Mar 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).