1. Introduction

The computing paradigm revolution has been an inherent force driving technological advancement, impacting scientific research, industrial development, and social progress. Classical transistor-based architectures have enabled exponential growth in computation, but such paradigms are constrained by intrinsic limits of scalability, energy efficiency, and processing rates. With the increasing demand for resolving intricate problems—particularly in fields such as artificial intelligence, cryptography, and molecular modeling—there is an urgent requirement for novel computing paradigms that are capable of handling vast amounts of data and intricate calculations efficiently [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Quantum computing has been a paradigm revolutionizing the way computation is done, leveraging the concepts of quantum mechanics to perform calculations many orders of magnitude faster than classical computers. With quantum bits (qubits) in superposition states and exploiting quantum entanglement, quantum computers have the potential to revolutionize industries by solving problems that are intractable for classical systems. Promising as it is, quantum computing is in its infancy, with significant challenges in hardware development, quantum error correction, and algorithm optimization.

The focus of this paper is to compare the evolution of computing paradigms, encompassing quantum computing, its theory, application, and scalability issues. Through a critical analysis of the current era of quantum computing, the research will delineate its potential in revolutionizing many sectors as well as overcoming today's technological setbacks[

6,

7,

8].

The development of computing paradigms has been dominated by a series of technical catalysts and facilitators that have determined the history of computing systems over several decades. These drivers include a wide range of advances in networking, hardware, software, and methodology, all of which support the growth of computing paradigms and the creation of more powerful and versatile computing systems[

9,

10,

11].

The unrelenting advance of semiconductor technology, fueled by Moore's Law—the hypothesis that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles roughly every two years—is one of the main drivers of technological advancement. Dramatic improvements in computing power have been made possible by the exponential increase in transistor density, which has spurred the creation of processors that are more powerful and less energy-hungry. The performance and computing hardware effectiveness have also been improved through innovations in semiconductor fabrication processes, such as the introduction of new materials and process node shrinkage. Software development practices have caught up to keep with increasing loads on computing systems alongside hardware improvement. Fast testing, iteration, software application deployments are now possible because of the software development lifecycle optimization achieved by virtue of implementing agile methodologies, DevOps practices, and continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipelines. As a result of these agile approaches, software development teams are now more flexible, responsive, and collaborative, and this has resulted in the creation of more stable and scalable software solutions .In addition, technological advancements in networking have also deeply influenced the distributed computing paradigm. Distributed computer resources can now seamlessly communicate and coordinate with each other due to the omnipresent availability of high-bandwidth internet connectivity, standardized communication protocols, and networking infrastructure. As a result, distributed computing paradigms like edge, cloud, and fog computing have become a reality, which leverage distributed architectures to provide computing solutions that are scalable, dependable, and inexpensive[

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

In addition, advances in computer architecture have revolutionized parallel computing by providing new paradigms in concurrency and performance optimization. Multi-core CPUs, GPUs, and accelerators are some instances of these advancements. The advent of highly efficient parallel algorithms and frameworks made possible due to these architectural advancements has made applications use parallelism and achieve substantial performance enhancements in a variety of areas. In this situation, an intersection of technology developments like networking, hardware, software, and methodologies has compelled the evolution of computing paradigms. Such technology drivers from the relentless advance of semiconductor technology to the widespread adoption of agile software development methodologies and distributed computing models, among others, have all been the causes of the construction of computing systems that are stronger, scalable, and more versatile. In order to address the changing demands and challenges of the digital age, it is vital to keep studying and innovating on these many fronts as computer technology evolves[

19,

20].

2. Literature Review

Computer paradigms have seen dramatic developments over the decades, ranging from mechanical computers during the early years to present-day high-performance computing (HPC) capabilities. Von Neumann architecture's invention laid the foundation for conventional computing, which provided sequential processing of information. Distributed and cloud computing further boosted scalability and availability. Recently, emerging paradigms such as edge computing and neuromorphic computing have aimed to optimize processing efficiency[

21,

22].

Moore's Law, a prediction of doubling transistor density every two years, has facilitated the exponential growth of computational power. Physical and thermodynamic constraints are leading to saturation of traditional processing capacities, and therefore a necessity to discover new paradigms of computing such as quantum computing [

23]

Quantum computing is different from classical computing in that it uses quantum mechanical phenomena. Quantum computers are capable of parallel computation through the concept of qubits being in superposition (representing many states at the same time). Entanglement also makes it possible for qubits to be strongly correlated even if they are physically far apart, which again increases computational efficiency [

24,

25,

26].

Pioneering research in quantum algorithms, as represented by Shor's algorithm for factorization of integers [

27], and Grover's algorithm for search in an unsorted database (Grover, 1996), has demonstrated the theoretical advantage of quantum computing over classical computing. Experimental demonstrations by companies such as IBM, Google, and Rigetti Computing have reported positive outcomes, e.g., Google's demonstration of quantum supremacy [

28]. Yet practical implementations continue to be plagued by noise, decoherence, and the need for error correction procedures [

29].

Quantum hardware development remains a major obstacle to large-scale realization. A number of approaches, including superconducting qubits, trapped ions, and topological qubits, are being explored for large-scale quantum architectures [

30]. Current advances in photonic quantum processors and atom-based quantum computing indicate promising directions to improve scalability [

31]. Yet, the brief coherence time of qubits and excessive error rates are serious obstacles, and the development of fault-tolerant models of quantum computing is necessary [

32].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Quantum AI holds promise to accelerate deep learning and provide improved pattern detection in data [

33]. Cryptography and Cybersecurity: The ability of the quantum computer to decrypt traditional encryption algorithms poses dangers as well as opportunities, leading to the development of post-quantum cryptographic algorithms [

34]. Healthcare and Drug Discovery: Accelerated molecular simulations enabled by quantum computing aid drug development and personalized medicine [

34]. Financial Modeling: Banks are exploring quantum computing to apply in risk assessment and portfolio optimization [

35].

2.1. Quantum Computing Paradigm

The computation field has undergone a paradigm shift with the advent of quantum computing, which has transformed the way humans process and comprehend information. Quantum computing essentially computes in a very different way compared to conventional computers by using the principles of quantum physics. Quantum bits, or qubits, can exist in an immediate superposition of 0 and 1, unlike traditional bits, which can only be either 0 or 1. Quantum computers can process vast amounts of data concurrently because of this special property of superposition, which could result in exponential speedups for some kinds of applications[

36,

37]. Entanglement is yet another basic quantum computing concept. It allows qubits to get entangled with one another such that, no matter how distant they are from one another, the state of one is contingent upon the state of the other. Because entangled qubits can have non-local correlations that go against classical intuition, this phenomenon allows quantum computers to perform operations that are impossible on classical computers.

The software that is executed on quantum computers, also known as quantum algorithms, uses these quantum effects to perform tasks more effectively than traditional algorithms in most problem-solving scenarios. Shor's algorithm, for instance, discovered by mathematician Peter Shor in 1994, illustrates how it can factor large numbers ten times faster than the best known classical algorithms. The difficulty of factoring large numbers is a fundamental block used in many encryption schemes; hence this result has profound cryptographic implications. Yet another widely used quantum algorithm that yields quadratic speedups for unstructured search problems is Grover's algorithm. Unlike typical search algorithms with linear time complexity, Grover's technique can look for an unsorted list of N elements in approximately √N steps using quantum parallelism and amplitude amplification. A lot of applications including pattern recognition, database search, and optimization are affected by this[

38]. Quantum computer hardware is still in its infancy, and there are numerous platforms and technologies that are being explored. Topological qubits, trapped ions, and superconducting qubits are top candidates for achieving scalable quantum computing. Quantum hardware is actively being researched and developed by organizations such as IBM, Google, and Rigetti Computing. The goal of such a venture is to construct useful quantum computers that can solve real-world problems. In broad terms, quantum computing is a completely different approach to computing that has the potential to revolutionize everything from material science and pharmaceutical research to cryptography and optimization. Accelerated progress in the technology promises practical quantum computers not so far down the road, with whole new directions of computation and exploration, even as there are still significant barriers to crossing in hardware design, error correction, and software development[

38].

2.2. Critical Analysis of Quantum Computing

Programming Model

The esoteric behavior of qubits and laws of quantum mechanics result in the programming paradigm of quantum computers being quite different from any classical computing model. Quantum gates are applied in quantum computers to operate on qubits to carry out actions, whereas in classical computers, data is processed by applying deterministic algorithms as well as logical gates acting on bits. Owing to this intrinsic variation, new programming models specific to the quantum world must be designed.

Superposition and entanglement, the two quantum mechanical properties inherent to the subject, are applied in the theory of quantum programming. With superposition enabling qubits to exist in 0 and 1 states at once, quantum algorithms have the ability to investigate several avenues of computation all at once. Unlike this, classical algorithms tend to take one, deterministic path. Superposition is a process that quantum algorithms use to compact and manipulate information in a highly parallel way, with the potential to deliver exponential speedup on specific classes of problems. Entanglement creates correlations between qubits regardless of the distance from one another, additionally enhancing the computation power of quantum algorithms. Such an effect also opens new pathways for the resolution of difficult tasks by allowing calculations based on non-local correlations within quantum algorithms. In order to preserve quantum states' coherence and efficiently use entanglement, noise suppression, and error correction methodologies must be tested thoroughly[

35,

36,

37,

38].

Quantum programming languages offer the main interface for the specification of quantum algorithms and communication with quantum hardware. They offer software developers high-level abstractions to specify quantum circuits, processes, and quantum algorithms by encapsulating the key difficulties of quantum mechanics. Q#, Quipper, and Qiskit are some of the most widely used quantum programming languages; each offers a distinct set of capabilities and abstractions for quantum algorithm design. Moreover, programmers who wish to harness the power of quantum technology are faced with other challenges due to the absence of well-established programming interfaces and tools for quantum computing. To democratize access to quantum computing resources and speed up the adoption of quantum technology across various domains, there is an effort being made towards standardizing quantum programming interfaces and creating reliable toolchains for the development of quantum algorithms. In summary, the quantum computing model of programming deviates from classical paradigms by using the principles of entanglement and superposition to facilitate novel strategies for addressing computational challenges. The full practical application of quantum computing remains inhibited by issues of error correction, hardware constraint, and standardization efforts, even though quantum programming languages offer levels of abstraction for describing quantum algorithms[

39].

2.3. Performance

Through the use of principles of quantum mechanics to solve advanced problems presently beyond the capability of classical computers, quantum computing can potentially transform computing capability dramatically. A primary component in assessing whether or not quantum computing is practical is its efficiency, including but not limited to speed and variables such as scalability, energy efficiency, and reliability. We address the performance properties of quantum computing in this review, considering both its potential benefits and limitations.

Because quantum systems demonstrate quantum coherence and intrinsic parallelism, quantum computation may achieve exponential speedup of classical computation for some problems, like integer factorization and search in a database. Compared to classical algorithms with exponential time complexity, methods like Shor's and Grover's algorithms can

be capable of resolving these problems in polynomial time. This exponential speedup has dramatic consequences for most areas where quantum computers may yield tremendous computational power, e.g., modeling, optimization, and cryptography. Some barriers do stand in the way of the full potential of quantum computing, however. Quantum systems' sensitivity to noise and error from decoherence, incorrect gates, and external interaction is one of the largest obstacles. Quantum error correction, or the long-term preservation of quantum state coherence, requires fault-tolerant quantum architectures and sophisticated error correction techniques. Such challenges reduce the dependability and scalability of quantum algorithms, particularly for large-scale computations[

40,

41].

Apart from that, several hardware challenges need to be addressed prior to making quantum algorithms practical. The challenges are qubit coherence times, gate fidelities, and connectivity constraints. The scope and complexity of the quantum computations achievable are constrained owing to the current platforms of quantum hardware having a low number of qubits and high error rates in spite of ongoing development. These hardware constraints and showing robust and scalable quantum systems are required to achieve quantum supremacy, which is the point at which quantum computers can solve certain problems faster than classical computers. In addition, there should be R&D to advance efficient quantum algorithms, improve quantum circuits, and reduce quantum errors because the field of quantum algorithm science and quantum software is new. Quantum software development as an area of work has barriers to widespread adoption and skills development because of the demands of specialized quantum physics, linear algebra, and quantum information theory knowledge. In short, while quantum computing has the potential for exponential speedups and revolutionary advances in many fields, achieving that potential would mean surmounting serious technical hurdles with hardware, error correction, and software engineering. In taking advantage of quantum computing for real-world applications and achieving the full performance capabilities of quantum systems, it will be important to solve these problems as the technology of quantum computing matures[

42].

3. Proposed Methodology

This study aims to analyze the development, performance, and scalability of quantum computing using a blended methodology involving theoretical analysis combined with experimental simulations. Comparative analysis of quantum computing paradigms over classical models of computation in terms of computational speed, efficiency of algorithms, and limitations in hardware constitutes the process of the study. In order to accomplish this, the study will utilize quantum development environments such as IBM's Qiskit and Google's Cirq to simulate quantum circuits and measure their computational advantage compared to conventional systems.

3.1. Control Flow

Control Flow using Quantum Charge-Coupled Device (QCCD) Architecture in Quantum Computing. The order of instructions being performed in a program is referred to as control flow. Control flow is essential in quantum computing in order to control the execution of quantum gates and operations so that the desired quantum states and outputs are produced.

3.2. Point of Entry

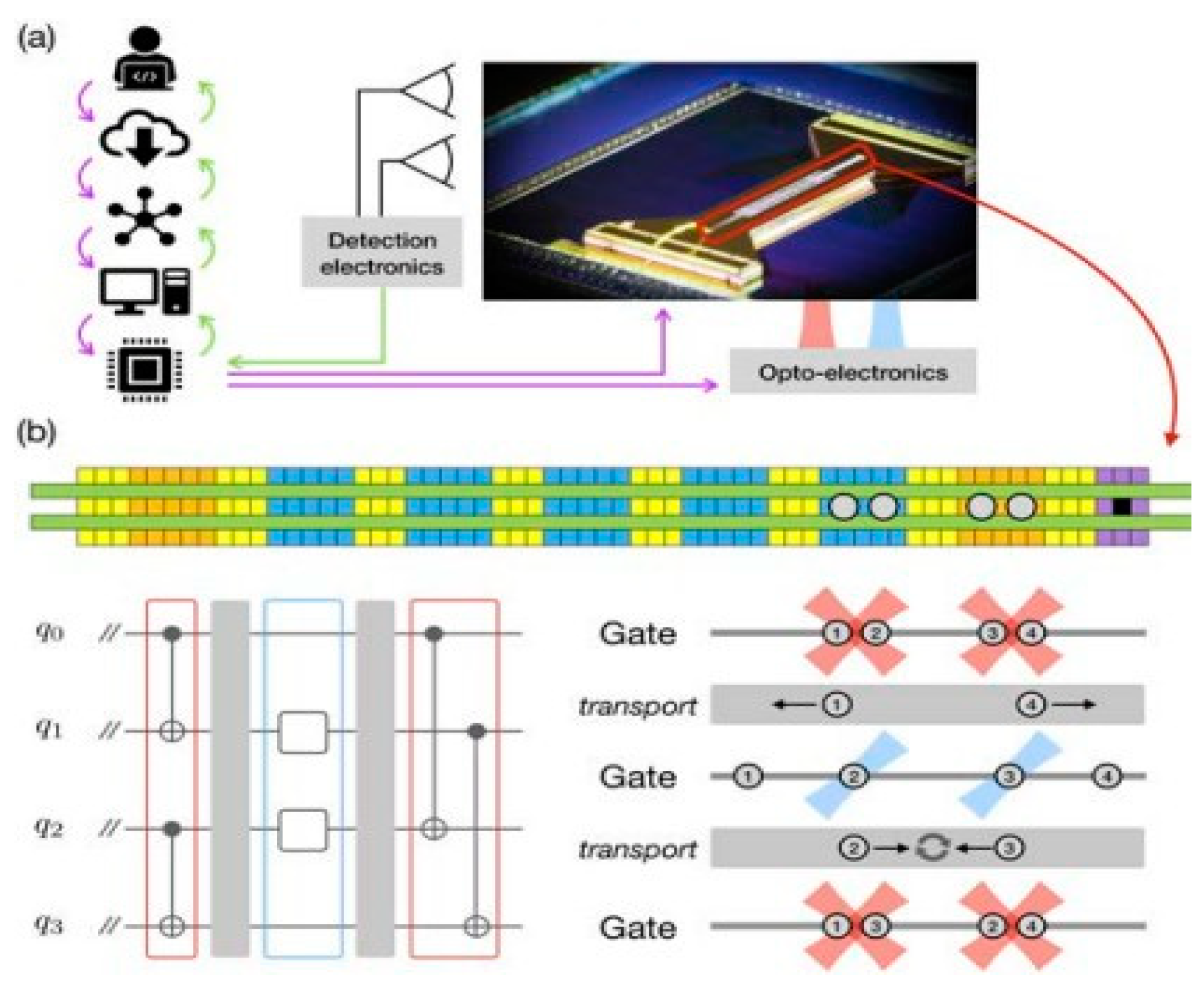

The initialization of qubits, which place them in a known state, is most often the first step in the quantum computing process. Qubits in the QCCD design are initialized by state-dependent fluorescence and optical pumping methods as shown in

Figure 1.

A picture of the trap and a schematic of the programmable QCCD quantum computing device. The picture indicates a schematic of the elements of the trap as well as the information flow from the user to the trapped qubits.

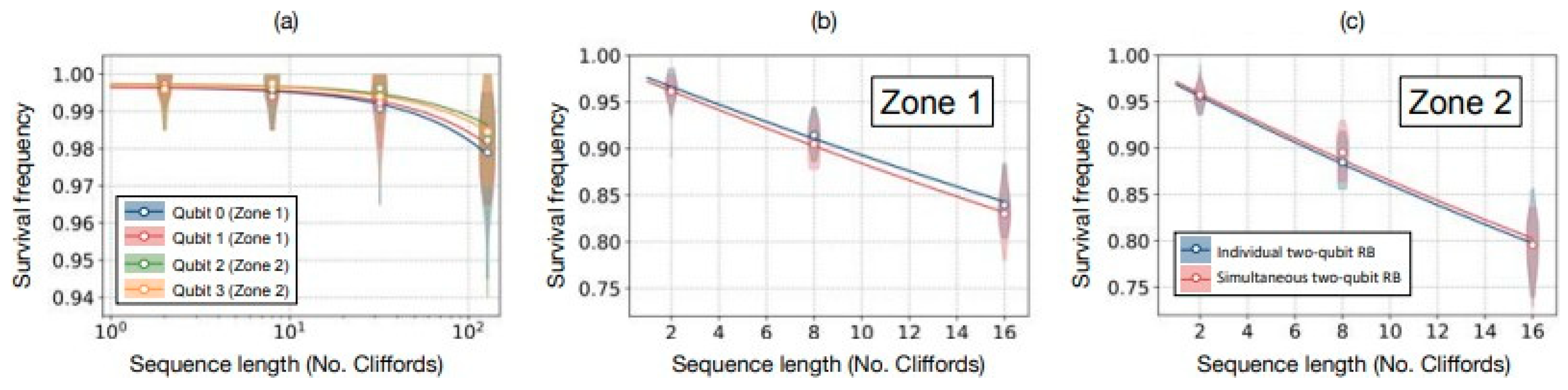

3.3. Trace Execution Path

The execution of a quantum program entails the process of applying quantum gates to the qubits in ain a predefined order. This is managed by a control system that delivers signals to the optoelectronic devices managing laser beams and the trap electrodes. These kinds of operations, which are carried out in different areas of the trap, involve multi-qubit entangling gates and single-qubit rotations as shown in

Figure 2.

3.4. Function Call Management

In conventional programming, subroutine calls are akin to function calls in quantum circuits. They can contain certain gate operations needed for building advanced quantum algorithms, such as Toffoli gates or CNOT gates. They are merged into native gates of the QCCD system and performed between zones with rapid ion transport to dynamically change qubit locations.

3.5. Find Exit Points

Measurement stages, at which qubits' states are being read, are the endpoints of quantum computation. Photons, released upon measurement of the state of qubits, are recorded and counted by the QCCD structure through an array of PMTs. The processed output is then delivered to the user.

3.6. Control Flow graphs

In quantum computing, the order of quantum operations is pictorially expressed in the form of control flow graphs, or CFGs. They help to clarify quantum circuit interdependence and parallelism. CFGs would show the sequence of state preparation, gate operations and transport, to final measurement and result accumulation in the QCCD architecture. These graphs are crucial in the guarantee of error-free operation and quantum algorithm optimization. Finally, the control flow of the QCCD quantum computing architecture includes qubit initialization, execution monitoring through accurate gate operations, management of complex gate subroutine calls, measurement location discovery, and control flow graph optimization. Through the provision of reliable and efficient quantum processing, this structured approach allows for the realization of scalable quantum processors.

3.7. Scalability

Quantum computers need to be useful in practical situations and millions of quantum bits are needed. Maybe the biggest problem with developing future technology is scalability. Quantum computers can do much more than computers can, but one of the things that is wrong with them is that the qubits need to be placed very near each other on the chip so that they can interact with one another. A lot of work remains to be done before they can be employed to assist in solving actual problems.

3.8. Qubit Technology Advances

Scalability requires advances in qubit technology, such as the creation of light-based quantum processors. Because they enable secure and efficient data transfer—a necessary function for processing more workloads—these processors reduce light losses and improve scalability.

3.9. Atom-Based Quantum Computers

A milestone of 1,000 atomic qubits was recently achieved in atom-based quantum computing. Researchers are looking to take this to 10,000 and even higher by fine-tuning the laser sources utilized in the systems. This is a significant step towards unlocking the computing power and efficiency that quantum computing promises.

3.10. Photonic Processors

have been proven to improve quantum computing scalability and performance by leveraging light to manipulate qubits. These processors reduce error and noise, which are essential to upholding the purity of quantum processes at scale.

3.11. Potential Application

Quantum computers effortlessly solve complex issues that are out of the reach of classical computers. Despite the fact that large-scale quantum computers are still in the early phases of development and small-scale quantum processors are the only ones presently accessible, researchers and companies are already actively pursuing a wide range of promising applications. A few of the possible applications are as follows:

3.12. Artificial Intelligence and machine learning

There is a tremendous potential for quantum computing to influence artificial intelligence. Complex computations that would take a long time for ordinary computers to solve can be solved by quantum computers. This can speed up the training of more complex AI models. Quantum computing can also allow AI to handle vast amounts of data in new and different ways, which can result in more advanced applications of the technology in natural language processing, image recognition, and predictive analytics. Overall AI system quality is usually established by the quality and volume of data on which they were trained; quantum computing can expand AI by enhancing the training.

3.13. Cybersecurity

Quantum computing holds immense possibilities to revolutionize cybersecurity. While it endangers current encryption methods, it also guarantees new potential for creating ultra-secure solutions. The modern digital economy relies on the factors of safety and trust. Yet the most common cybersecurity technologies and methods—RSA cryptography, to be exact—won't be quantum-resistant to advanced quantum technology. Should superposition and entanglement, two intrinsic performance bottlenecks of quantum computers, be circumvented, it could be much easier for hackers to bypass algorithmic trapdoors. Financial institutions should rethink their means of data security and look for RSA alternatives in the form of Quantum Key Distribution (QKD). QKD can be utilized today to provide very secure encryption keys, building networks that are able to withstand the threat posed by quantum, which online companies are exposed to.

3.14. Healthcare

Personalized medicine is now a reality thanks to the extremely fast DNA sequencing capability of a quantum computer. With proper modeling, it can enable the design of new medicines and treatments easily. Quantum computing can potentially contribute significantly to the development of efficient imaging systems that will be able to provide medical physicians better, real-time, fine-grained visibility. Complicated optimization issues involving the search for the optimal radiation therapy to kill the cancer cells with least damage to the surrounding normal tissues can be addressed by it as well.

Quantum computing will make it possible to investigate the molecular interactions at the most fundamental level, which will lead to new possibilities in medical research and the discovery of drugs. Whole-genome sequencing and analytics can be made faster though whole-genome sequencing is a time-consuming task by the help of qubits. By the next-generation technologies enabling on-demand computing, remapping medical data security, and discovering novel medicines with precision, quantum computing is able to completely revolutionize the healthcare sector.

3.15. Financial Services

The capacity to examine a broad spectrum of possible outcomes is needed for many financial use cases. Financial institutions use statistical models and algorithms to forecast future events to some extent. These methods are fairly good but not infallible. Computers that are accurate at making predictive computations are increasingly important in an era where enormous amounts of data are generated every day. Because quantum computing can handle enormous volumes of data and compute results faster and more accurately than any conventional computer has ever been able to, some financial institutions are choosing it because of this aspect. Financial organizations anticipate enormous advantages once they will be able to utilize quantum computing effectively.

4. Experimental Setup

The experimental component of this study will involve the implementation of quantum algorithms on cloud-based quantum computing platforms, such as IBM Quantum Experience and Rigetti’s Quantum Cloud Services. The selected algorithms include Shor’s algorithm for integer factorization and Grover’s algorithm for database search, which serve as benchmarks for assessing quantum computational efficiency. Simulations will be executed on Python-based quantum programming libraries where quantum circuits will be designed, optimized, and executed to measure execution time, coherence stability, and error rates. Quantum state visualizations and probability distributions will also be analyzed to identify the impact of superposition and entanglement on computation performance.

Hardware constraints will also be considered by implementing quantum circuit implementations on a range of quantum processors, such as superconducting qubits and trapped-ion quantum computers. The experimental setup will also include a side-by-side comparison with classical computing models on traditional high-performance computing (HPC)[

43] infrastructure. Performance metrics such as qubit fidelity, gate error rates, and quantum volume will be quantified to determine the feasibility of widespread deployment of quantum computing.

5. Results and Discussion

The anticipated results are expected to demonstrate the quantum computational advantage of quantum algorithms in some problem classes, particularly for cryptography and optimization problems. Shor's algorithm is expected to demonstrate exponential speedup over the classical factorization algorithms, indicating the implications of security for cryptography systems. Similarly, Grover's algorithm is expected to exhibit quadratic speedup in the unstructured search problems, supporting the potential for data analysis through quantum computing.

Nevertheless, experimental results will also highlight current quantum hardware limitations, including qubit decoherence, gate errors, and issues of scalability. The controversy will revolve around quantum speedup versus practicality in maintaining quantum coherence across long computational processes. The results will be interpreted to determine the threshold at which quantum supremacy can be practically demonstrated for practical applications. The study will also conclude with a critical examination of the preparedness of quantum computing for widespread adoption and recommendations for overcoming existing technological limitations.

6. Conclusion

Overall, the rapid expansion of technology is driving the continuous evolution of computing paradigms, each of which offers a particular benefit optimized for a particular set of computational needs. Drawing on the postulates of quantum mechanics, quantum computing is an emerging paradigm that can solve problems that are beyond classical computers. The core nature of quantum computing, such as its programming model, performance, control flow, scalability, and applications, were investigated in this study. Quantum computing holds great promise to transform many fields and deliver exponential accelerations, yet it remains beset by significant technological hurdles, especially in hardware engineering, error correction, and algorithmic breakthroughs. This research critique and research demonstrate the complexity of the quantum computer and its significance for technological advancements in the future. It underscores the significance of taking a multi-dimensional approach in designing, deploying, and optimizing paradigms of quantum computing to deliver their full potential. With time, incorporation of quantum computing into increasingly diverse fields will be anticipated to yield profound findings and offer new dimensions of computation.

References

- Yuan, C.; Villanyi, A.; Carbin, M. (2024). Quantum control machine: The limits of control flow in quantum programming. Association for Computing Machinery. Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/154392.

- Pino, J.M.; Dreiling, J.M.; Figgatt, C.; Gaebler, J.P.; Moses, S.A.; Allman, M.S.; Baldwin, C.H.; Foss-Feig, M.; Hayes, D.; Mayer, K.; Ryan-Anderson, C.; Neyenhuis, B. Demonstration of the trapped-ion quantum CCD computer architecture. Nature 2021, 592, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, D.; Googin, C.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y.; Galda, A.; Safro, I.; Pistoia, M.; Alexeev, Y. Quantum computing for finance. Nature Reviews Physics 2023, 5, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rasool, R.; Ahmad, H.F.; Rafique, W.; Qayyum, A.; Qadir, J.; Anwar, Z. Quantum computing for healthcare: A review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dura Digital. (n.d.). Building the future: Key applications for quantum computing. Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://www.duradigital.com/post/building-the-future-key-applications-for-quantum-computing.

- Alferidah, D.K.; Jhanjhi, N.Z. (2020, October). Cybersecurity impact over big data and IoT growth. In 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI) (pp. 103–108). IEEE.

- Jena, K.K.; Bhoi, S.K.; Malik, T.K.; Sahoo, K.S.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Bhatia, S.; Amsaad, F. E-learning course recommender system using collaborative filtering models. Electronics 2022, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherwadi, N.; Mittal, U.; Singla, J.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Yassine, A.; Hossain, M.S. Prediction of fruit maturity, quality, and its life using deep learning algorithms. Electronics 2022, 11, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S.; Vimal, S.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Dhanabalan, S.S.; Alhumyani, H.A. Blockchain-based peer-to-peer communication in autonomous drone operation. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 7925–7939. [Google Scholar]

- Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Humayun, M.; Almuayqil, S.N. Cybersecurity and privacy issues in industrial Internet of Things. Computer Systems Science & Engineering 2021, 37. [Google Scholar]

- University, R. (2024). Quantum computing takes a giant leap with light-based processors. SciTechDaily. Retrieved from https://scitechdaily.com/quantum-computing-takes-a-giant-leap-with-light-based-processors.

- Paradowski, S.; Darmstadt, T.U. (n.d.). A new record for atom-based quantum computers: 1,000 atomic qubits and rising. phys.org. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2024-02-atom-based-quantum-atomic-qubits.html.

- Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Babbush, R.; Bacon, D.; Bardin, J.C.; Barends, R.; Boixo, S.; Broughton, M.; Buckley, B.B.; Buell, D.A.; Burkett, B.; Bushnell, N.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chiaro, B.; Collins, R.; Courtney, W.; Demura, S.; Dunsworth, A.; Farhi, E. Hartree-Fock on a superconducting qubit quantum computer. Science 2020, 369, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, R.; Roos, C.F. Quantum simulations with trapped ions. Nature Physics 2012, 8, 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Buyya, R.; Broberg, J.; Goscinski, A.M. (2011). Cloud computing: Principles and paradigms. John Wiley & Sons.

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ju, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y.; Munro, W.J. Quantum programming languages: From a survey towards the future. ACM Computing Surveys 2021, 54, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cerf, V.G.; Navascués, M. Testing the efficiency of quantum information processing with linear optics. Physical Review Letters 2017, 118, 010502. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, J.; Corrado, G.S.; Monga, R.; Chen, K.; Devin, M.; Mao, M.; Ng, A.Y. Large-scale distributed deep networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2012, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Devitt, S.J.; Munro, W.J.; Nemoto, K. Quantum error correction for beginners. Reports on Progress in Physics 2013, 76, 076001. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, K.; Matsuo, S. (2020). Edge computing: Enabling distributed intelligence in IoT and sensor networks. CRC Press.

- Saeed, S.; Abdullah, A. Combination of brain cancer with hybrid K-NN algorithm using statistical analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surgery. International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security 2021, 21, 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, S.; Abdullah, A. Analysis of lung cancer patients for data mining tool. International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security 2019, 19, 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, S.; Abdullah, A.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Naqvi, M.; Nayyar, A. New techniques for efficiently k-NN algorithm for brain tumor detection. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2022, 81, 18595–18616. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, S. (2021). Optimized hybrid prediction method for lung metastases. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine.

- Saeed, S.; Abdullah, A.; Naqvi, M. Implementation of Fourier transformation with brain cancer and CSF images. Indian Journal of Science & Technology 2019, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gantz, J.; Reinsel, D. The digital universe in 2020: Big data, bigger digital shadows, and biggest growth in the Far East. IDC iView: IDC Analyze the Future 2012, 2007, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, L.K. (1996). A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on the Theory of Computing (pp. 212–219). ACM.

- Guo, Y.; Herold, S.; Wegscheider, W.; Haug, R.J. Experimental investigation of a quantum dot quantum computer architecture. Nature Communications 2013, 4, 1456. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.; Yoo, J. (2014). Cloud computing: Concepts, technology & architecture. Pearson Education.

- IBM Quantum Experience. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://quantum-computing.ibm.com/.

- Ladd, T.D.; Jelezko, F.; Laflamme, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Monroe, C.; O'Brien, J.L. Quantum computers. Nature 2010, 464, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Quantum. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/quantum.

- Microsoft Quantum Development Kit. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/quantum/development-kit.

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. (2010). Quantum computation and quantum information. Cambridge University Press.

- Patterson, D.A.; Hennessy, J.L. (2018). Computer organization and design: The hardware/software interface. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2018, 2, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Qiskit. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://qiskit.org/.

- Rigetti Computing. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.rigetti.com/.

- Shor, P.W. (1994). Algorithms for quantum computation: Discrete logarithms and factoring. Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (pp. 124–134). IEEE.

- Smith, A.M.; Curtis, M.J.; Zeng, W.J. A practical quantum instruction set architecture. Quantum Science and Technology 2017, 2, 015006. [Google Scholar]

- Stonebraker, M.; Çetintemel, U.; Zdonik, S.B. The 8 requirements of real-time stream processing. ACM SIGMOD Record 2005, 34, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, V.; Heim, B.; Rebentrost, P.; Wolf, S. (2021). Quantum computing applications in industry. EPJ Quantum Technology, 8(1), 19. Retrieved from https://epjquantumtechnology.springeropen.com/articles/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-021-000.

- Aldughayfiq, B.; Ashfaq, F.; Jhanjhi, N.Z.; Humayun, M. Explainable AI for retinoblastoma diagnosis: interpreting deep learning models with LIME and SHAP. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).