1. Introduction

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is a lentivirus that primarily infects CD4

+ T- T-lymphocytes, leading to progressive immune system deterioration and, if left untreated, the onset of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDs). In 2023, approximately 1.3 million people contracted HIV, and 630,000 deaths were attributed to HIV-related complications [

1].

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) is considered the standard for HIV treatment, working to suppress viral replication of infected cells, thereby preventing the virus from replicating and infecting adjacent cells. cART is composed of 6 primary drug classes, each of which targets a phase of the HIV-1 life cycle in active HIV-1 cells [

2,

3]. cART has been shown to be extremely effective in reducing the detectable viral reservoir, as measured by the number of virion-producing cells. However, it is important to recognize that while cART is highly effective in reducing viremia, it has no cytotoxic impact on the cells it affects. Therefore, while cART can severely diminish the number of detectable cells, the actual active cell population remains stable and remains viable (even if they are undetectable), capable of rekindling infection or seeding new reservoirs upon treatment cessation [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

This phenomenon is corroborated by several recent studies which propose that during antiretroviral therapies, non-quiescent cells retain the capacity for replication within certain “sanctuary sites” in lymphoid tissues, thus sustaining the presence of the viral reservoir [

13,

14]. Lorenzo-Redondo et al. (2016) provided evidence that HIV-1 can continue to replicate in such tissues even when potent cART is being implemented. Through longitudinal analysis of peripheral blood and lymph node samples from patients over a six-month period, they posit that viral rebound detected in blood may arise not from the stochastic reactivation of latent cells, but from ongoing replication within these sanctuary sites [

12].

Moreover, cART is unable to achieve complete viral eradication of HIV-1 from infected individuals due to the persistence of quiescent reservoirs. Latency is maintained when HIV-1 integrates itself into the host’s genome but does not produce virions, hampering the ability of cART treatments to detect and attack it, therefore necessitating lifelong cART treatment to maintain viral suppression. Then, at any given moment, the latent reservoir can reactivate and proliferate throughout the body [

15,

16]. Since cART is only able to prevent viral replication and the spread of HIV-1 when the virus is active, latency is the downfall of such treatments and the primary focus of contemporary HIV-1 research [

2].

To address the challenge of persistent HIV-1 reservoirs, researchers have developed “shock-and-kill” treatments, which aim to induce viral reactivation, thereby exposing latently infected cells to immune clearance and antiretroviral-mediated suppression. These approaches rely on latency-reversing agents (LRAs) to disrupt viral latency, followed by cART and immune-mediated cytotoxicity to eliminate reactivated cells [

15,

17]. Despite their promise, LRAs remain a developing field and have shown relatively low efficacy in reactivating latent HIV-1 [

18]. Although recent breakthroughs in chromatin-modulating drugs, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis), have improved LRA potency, their effectiveness in clearing reservoirs remains limited, with most treatments showing little to no reduction in the viral reservoir following LRA treatment [

19]. Even when LRAs successfully induce reactivation, cART is still incapable of eliminating the reactivated cells. Instead, it merely suppresses new virion production, preventing further infection but leaving both active and reactivated cells intact and capable of reseeding reservoirs [

7,

8,

9,

10,

12,

13,

14].

These challenges underscore that while LRAs are becoming increasingly effective at reactivating latent HIV-1, their practical ability to eliminate active and reactivated cells remains minimal due to the lack of cytotoxicity from cART. Consequently, there is a growing demand for treatments capable of directly killing both active and reactivated HIV-1 cells with high cytotoxic efficacy, addressing the fundamental limitations of current LRA and cART-based approaches [

20,

21]. The research that has been done on directly eliminating active and reactivated HIV-1 cells largely focuses on CRISPR-mediated strategies [

22,

23,

24]. One widely cited study utilizes a CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) mediated shock-and-kill approach to eliminate reactivated HIV- 1 cells. In this approach, CRISPRa targets the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (HIV-1 LTR) promoter, inducing latent HIV-1 transcription and upregulating the expression of Tat and Rev, two viral regulatory proteins. Tat then binds to the HIV-1 LTR, further amplifying transcription, while Rev facilitates the nuclear export of viral mRNA. This dual activation triggers the expression of a tBid suicide gene, leading to the apoptosis of reactivated cells [

23]. While this study exemplifies the commonly presented CRISPR-mediated shock-and-kill approaches, they also come with a number of challenges, such as immunogenicity, delivery, and high mutation rates [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Therefore, although such CRISPR-mediated strategies have shown potential in targeting latent HIV-1, further research is needed to assess their feasibility, safety, and effectiveness in clinical settings.

Given these challenges concerning latent HIV-1 clearance and room to grow in the field of shock-and-kill treatment methods, this study aims to introduce and evaluate the effectiveness of a novel HIV-1 LTR-driven therapeutic construct capable of directly reactivating latent cells and then eliminating these reactivated cells, as well as directly eliminating active HIV-1 cells, without reliance on immune clearance. This marker system uses the HIV-1 LTR promoter to drive the expression of the diphtheria toxin A (DTA) suicide gene. Upon reactivation, LTR transcription triggers DTA expression, which inhibits protein synthesis and induces apoptosis in infected cells. Unlike cART, which only suppresses viral replication, this system actively kills HIV-1-infected cells with supreme cytotoxicity, offering a more direct and effective approach to reducing the infected cell population. Through computational simulations validated with experimental data, we assess its impact on viral reservoir depletion, active HIV-1 suppression, and CD4+ T-cell restoration. Our findings indicate that the novel construct, particularly in combination with cART, significantly reduces latent and active HIV-1 populations while improving immune function. These results highlight its potential as a promising adjunct to existing shock-and-kill strategies, addressing key limitations in current HIV-1 eradication efforts.

3. Discussion

Current shock-and-kill treatments consist of CRISPR-based interventions, as explained in

Section 1. However, CRISPR-based therapies face substantial logistical and mechanistic barriers. One challenge presents in the form of HIV-1's high mutation rate, which facilitates the emergence of CRISPR-resistant escape variants [

25,

28]. Additionally, CRISPR components pose immunogenicity risks due to their bacterial origin, which can provoke host immune responses thus reducing therapeutic efficacy [

27]. Finally, delivery remains a critical obstacle. CRISPR constructs are large and complex genetic systems and therefore require large genetic payloads, which often exceed the packaging capacity of clinically approved vectors [

25].

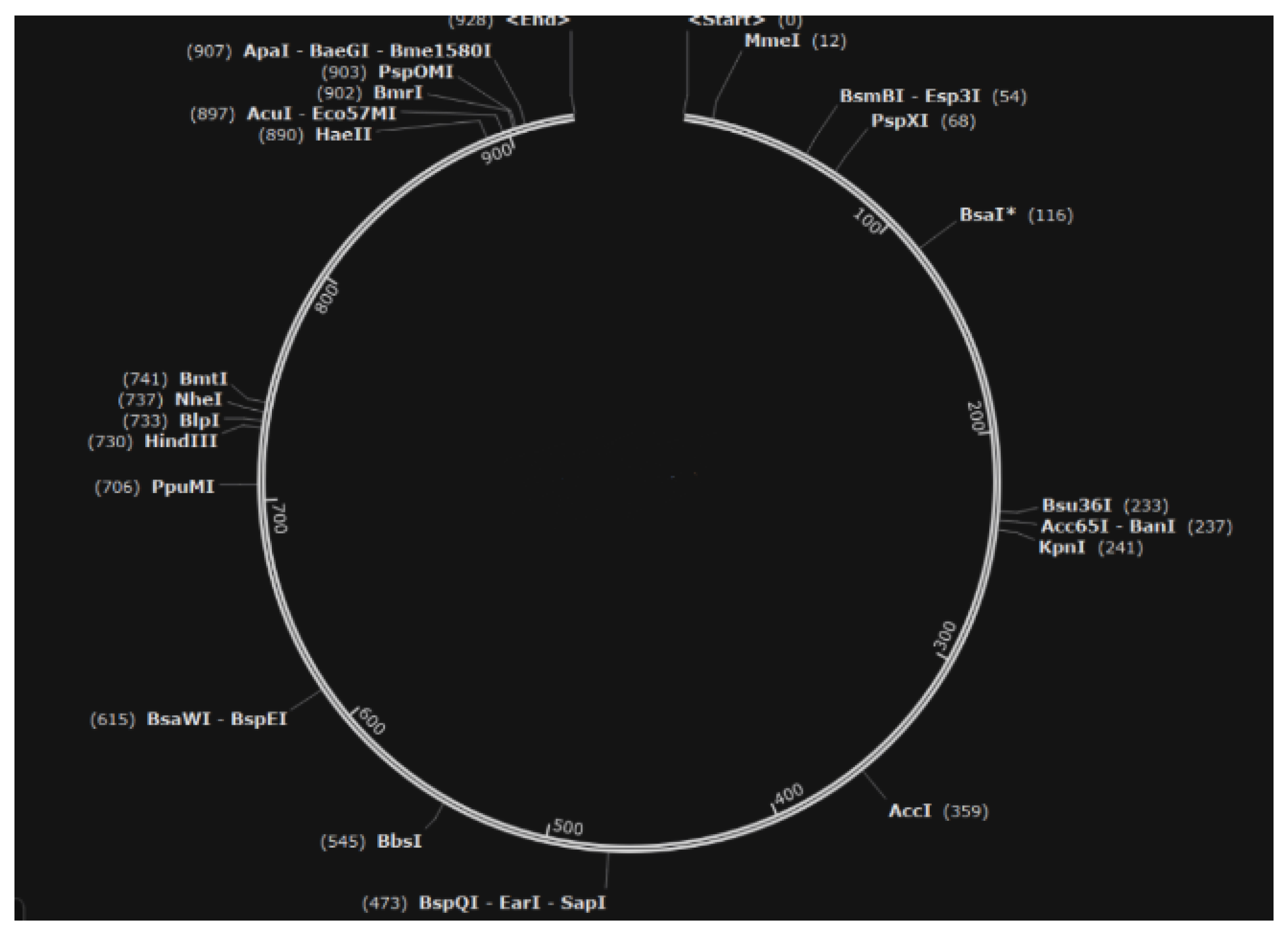

To overcome these challenges, our study presents a novel HIV-1 LTR-driven therapeutic construct designed to exploit the virus’s own transcriptional machinery. This construct targets both latent and active HIV-1 reservoirs through a cytotoxic, all-in-one, shock-and-kill mechanism, which triggers apoptosis in HIV-infected cells via the expression of a diphtheria toxin A (DTA) suicide gene under the control of the HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) promoter. The construct was designed specifically to overcome aforementioned challenges with current shock and kill treatments. Immunogenicity is not a barrier for this construct given its reliance on human and viral regulatory elements rather than bacterial components, thus avoiding host immune activation and the compact, streamlined structure of the construct (only 928 basepairs) enhances the efficiency of delivery, as it requires a smaller genetic payload compared to CRISPR systems (5000-6000 base pairs), making it compatible with clinically approved viral vectors.

Figure 8.

Structure of the Novel Construct (modeled with Snapgene 7.2.1).

Figure 8.

Structure of the Novel Construct (modeled with Snapgene 7.2.1).

To test the efficacy of our marker in reducing both the detectable and total viral reservoir, we carefully constructed two in silico models. The first utilized ABMs to simulate based population dynamics in an HIV-1 system. The second utilized Tellurium, a Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) Python platform, which enabled us to precisely simulate intracellular kinetics and cell to cell interactions. To capture system level dynamics, we employed NetLogo, an agent based model that simulates the behavior of individual cells in a heterogeneous population over time. The ABM simulations allowed us to assess the construct’s impact on the overall CD4+ T-cell, latent HIV-1 reservoirs, and active HIV-1 reservoir dynamics. These programs work together to validate the treatment on both a cellular level and a wider, systemic level. The convergence of these independent methodologies provides robust evidence that our HIV-1 LTR-driven construct effectively targets both latent and active HIV-1 reservoirs, supporting its potential as a transformative strategy for HIV-1 eradication.

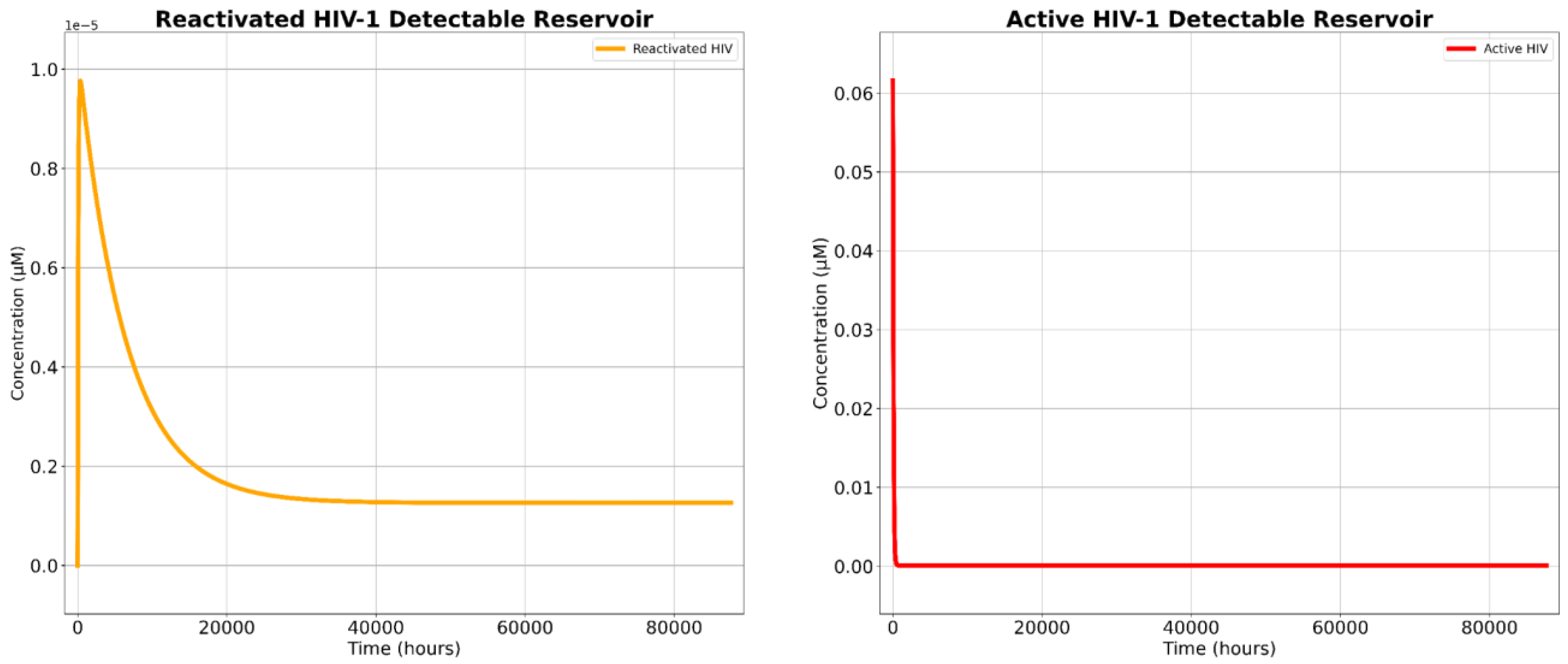

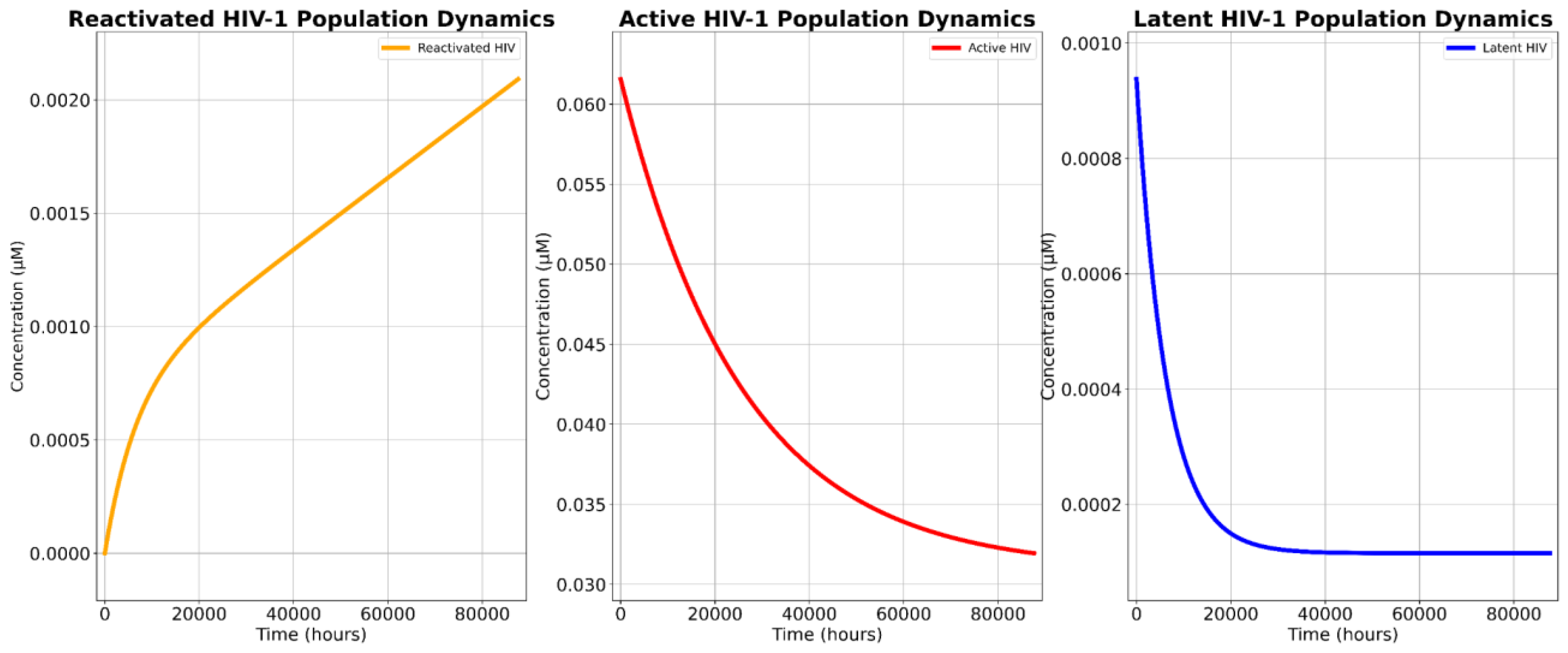

Our SBML simulations projected the novel treatment’s potent cytotoxicity, confirming its ability to significantly deplete both the detectable HIV-1 reservoir and the total HIV-1 reservoir population.

The two critical parameters for assessing the therapeutic viability of this novel approach are (1) the projected cytotoxic effect in targeted cells and (2) its capacity to reduce both the total and detectable reservoir populations. Our findings validate the first criterion, but not the second. Comparative analyses reveal that the novel therapy reduced the total viral reservoir by 96.26% and exhibited a cytotoxic efficacy of 99.27%. This indicates that nearly ten out of ten infected cells targeted by the construct were eradicated, even when accounting for mutational escape pathways, which is a persistent obstacle in conventional shock-and-kill strategies [

17]. In contrast, cART-LRA combination therapy resulted in a reduction of the total reservoir population by 44.72% due to cART’s lack of cytotoxic ability [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Consequently, the novel therapy demonstrated a 93.17% greater efficacy in reservoir depletion compared to the cART-LRA polytherapy.

However, cART-LRA polytherapy was capable of reducing the detectable reservoir by 99.66% while the novel treatment was only capable of reducing the detectable reservoir by 99.27%, indicating that the cART-LRA polytherapy is 0.39% better at mitigating the detectable reservoir when compared to the novel therapy. Yet, this marginally greater reduction in the detectable reservoir does not undermine the therapeutic potential of the proposed construct. The primary limitation of cART-based regimens remains their inability to eliminate the latent reservoir, leading to inevitable viral rebound upon treatment cessation [

4,

6]. Although cART-LRA polytherapy is 0.39% more effective in reducing the detectable reservoir, this advantage is clinically insignificant in the context of long-term viral control, as cART alone does not contribute to reservoir eradication. In contrast, the novel therapy’s ability to reduce the total reservoir by 96.26% suggests a fundamental shift in treatment outcomes, as a smaller latent reservoir and infectious reservoir directly correlates with a lower likelihood of post-treatment viral resurgence [

29,

30]. Given that sustained viral suppression under cART necessitates lifelong adherence, the novel approach has the potential to minimize or even prevent viral rebound, rather than delaying it, thus shifting HIV treatment away from indefinite management and towards curative intervention.

The superior efficacy of the novel approach in reducing the population stems from its mechanistic advantage over cART-LRA therapy. LRAs facilitate latency reversal by inducing the transition of quiescent infected cells into a transcriptionally active state thus transiently increasing the size of the reactivated reservoir. While cART is capable of effectively inhibiting viral replication and preventing de novo infection, it lacks direct cytotoxicity, allowing reactivated and actively infected cells to persist, maintaining the potential for viral rebound upon treatment cessation [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. In contrast, the novel construct exhibits direct cytotoxicity against infected cells, leading to both depletion of the detectable reservoir and substantial reduction of the total viral reservoir. This dual mechanism not only prevents ongoing viral propagation but also serves to actively eradicate HIV-infected cells, whether latent, reactivated, or actively replicating, rather than merely suppressing them.

The sensitivity analyses provided crucial insights into the mechanistic drivers of treatment efficacy, particularly regarding the impact of latent cell reactivation (kLRA) and DTA-induced apoptosis (k₃).

The findings derived from the sensitivity analyses underscore a distinct advantage of the novel construct over contemporary therapies: the efficacy of the novel treatment is directly enhanced by improvements in latency reversal whereas cART-LRA combination therapy becomes less effective under the same conditions.

The sensitivity analysis of k

LRA in the novel treatment monotherapy revealed that as the efficacy of the LRA increased, so did the overall reservoir depletion, with HIV-1 population reductions improving from 95.98% to 96.51% as k

LRA increased by 20% (-10% to +10% range). This indicates that a 1% increase in LRA efficacy correlates with a 0.027% rise in reservoir reduction. Yet, this trend suggests that as the field of LRA development advances and we develop the ability to reactivate more latent cells, the cytotoxic effects of the marker will become even more pronounced. However, the findings also highlight that, while the novel treatment demonstrates strong cytotoxicity, the persistence of the latent reservoir remains dependent on effective reactivation. Even at the highest k

LRA tested, a residual latent population persisted, indicating that current LRAs may still be suboptimal for achieving full eradication, a severe limiting factor for the novel treatment. In stark contrast to the marker-based monotherapy, increasing k

LRA in the cART-LRA combination therapy paradoxically expanded the total viral reservoir, with reductions ranging from 44.848% to 44.839% (-10% to 10%). This result aligns with the fundamental limitation of cART: while it prevents viral replication, it lacks intrinsic cytotoxicity, meaning that the reactivation of latent cells simply increases the pool of infected cells rather than eliminating them. In other words, cART is unable to keep up with higher efficacy rates of LRA. This phenomenon is particularly problematic given that persistent reactivated cells remain viable and capable of viral rebound upon treatment cessation. Thus, a key distinction between the two therapies emerges. For the marker-based treatment, increasing k

LRA enhances efficacy by exposing more infected cells to cytotoxic elimination. In contrast, For cART-LRA therapy, increasing k

LRA exacerbates the challenge of persistence by expanding the infected cell population. These findings indicate that cART-LRA therapy may become less effective as LRA potency improves, while the novel construct continues to grow in efficacy. The primary limitation of the marker-based treatment lies in the current effectiveness of LRAs, but this constraint is only temporary. As next-generation LRAs with greater potency and specificity are developed, the novel construct will disproportionately benefit, further enhancing its ability to eliminate the reservoir and reduce detectable HIV. This adaptability makes it a more scalable and future-proof strategy for long-term HIV-1 eradication. Meanwhile, as LRAs with greater potency and specificity are developed, cART-LRA polytherapies will not yield an enhanced ability to eliminate HIV-1 reservoirs without some complementary cytotoxic therapy [

20,

21].

The sensitivity analysis of k₃ further confirmed the robustness of the novel treatment.

Table 3 reveals that increasing k₃ (rate of DTA-induced apoptosis) enhances viral reservoir reduction, albeit marginally (96.20% to 96.33% over a ±10% k₃ range). Active cell populations decrease monotonically with higher k₃, while reactivated cells show minimal fluctuations (5.45–6.35 × 10⁻⁶ µM). The marker’s cytotoxicity is robust but not highly sensitive to k₃ variations, suggesting its efficacy depends more on reactivation efficiency (k_LRA) than apoptosis kinetics. Notably, the latent reservoir remained largely unchanged across k₃ variations, reinforcing the conclusion that LRA efficacy, rather than marker-induced cytotoxicity alone, is the primary bottleneck for complete reservoir clearance.

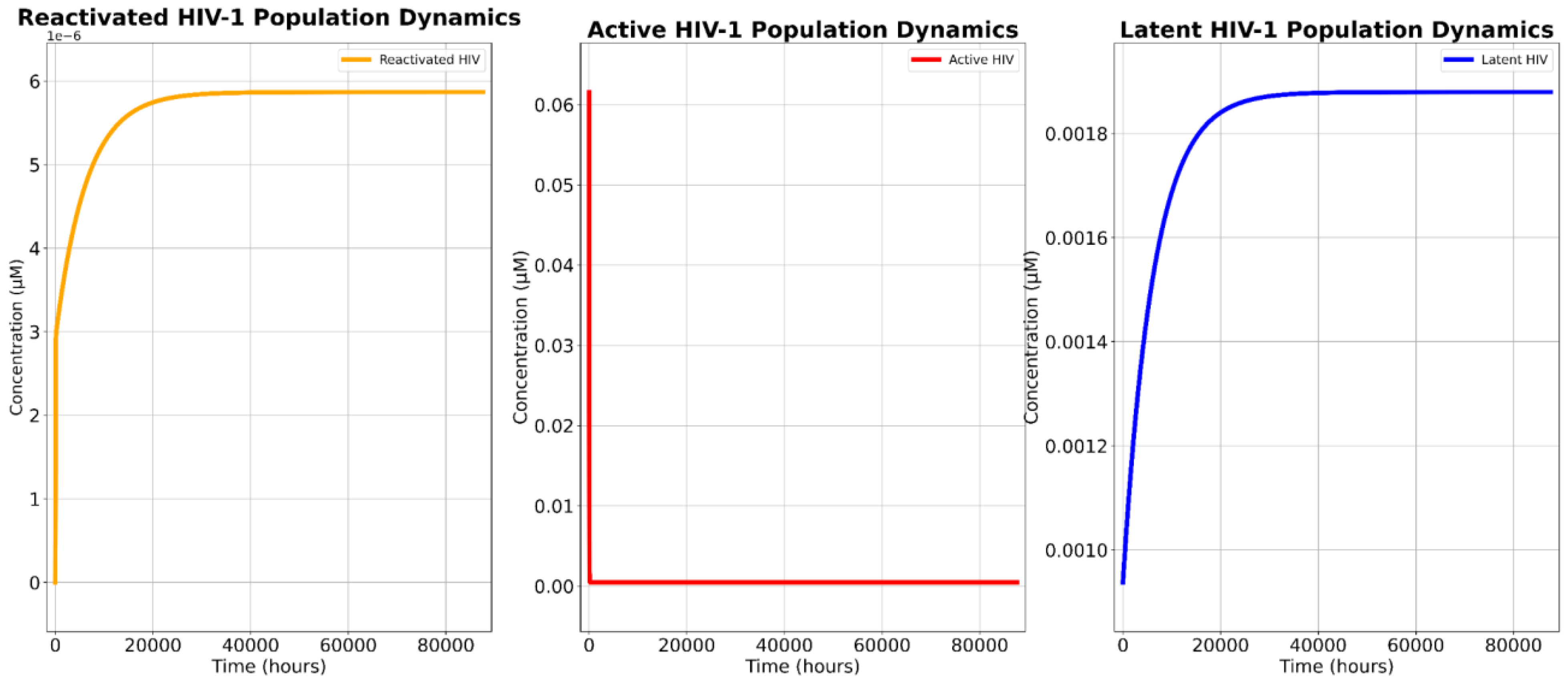

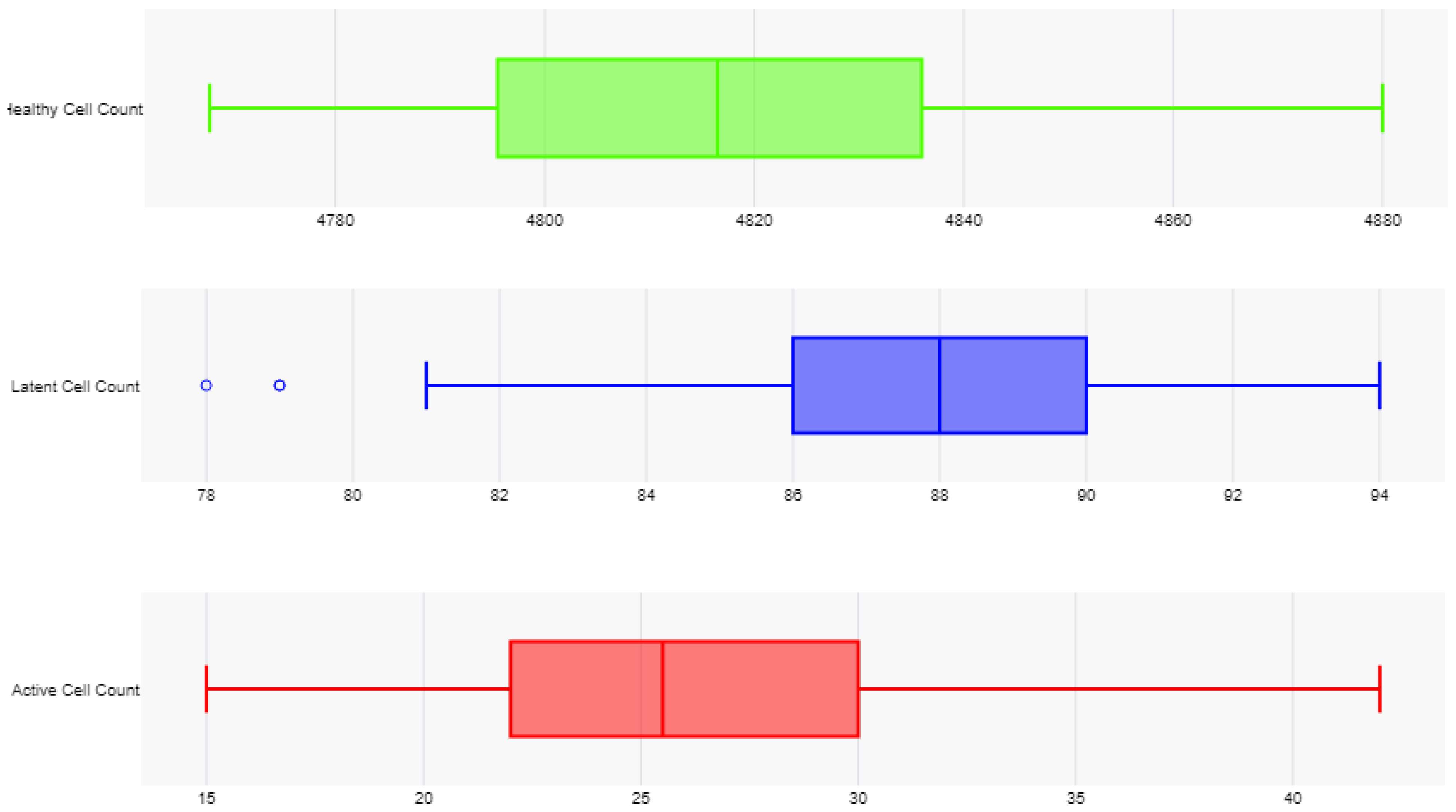

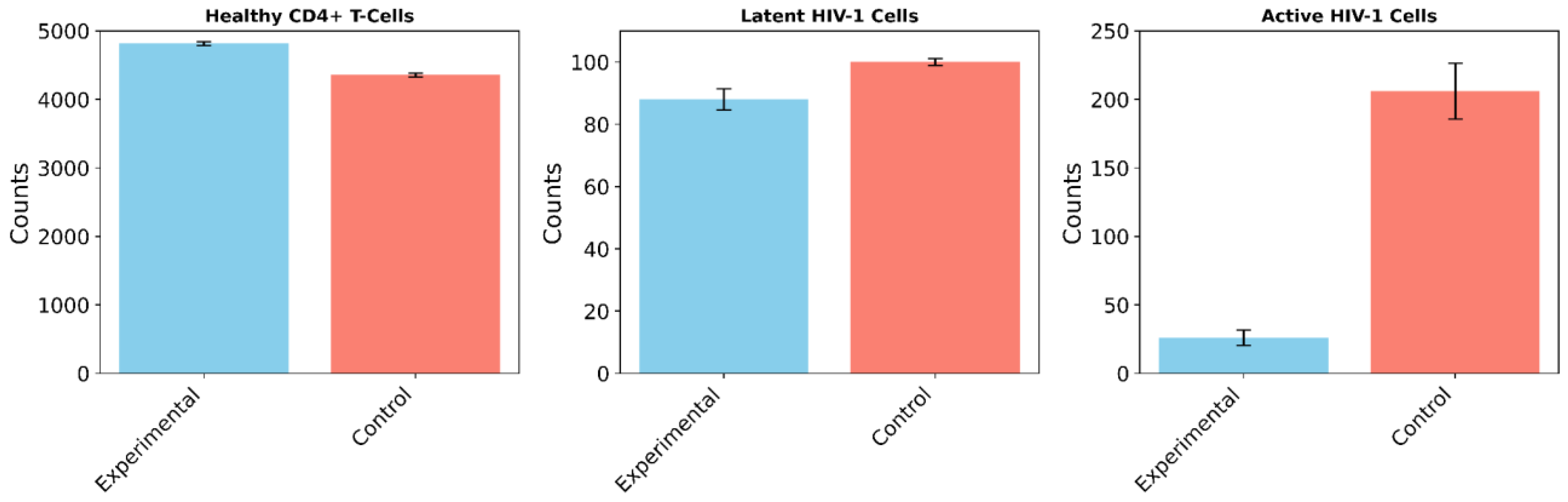

While SBML modeling captures molecular-level kinetics, Agent Based Modeling (ABM) simulations provide insight into population-level dynamics over time, allowing us to evaluate the broader effects of the construct across multiple cell populations and introduce stochasticity not seen in the SBML models.

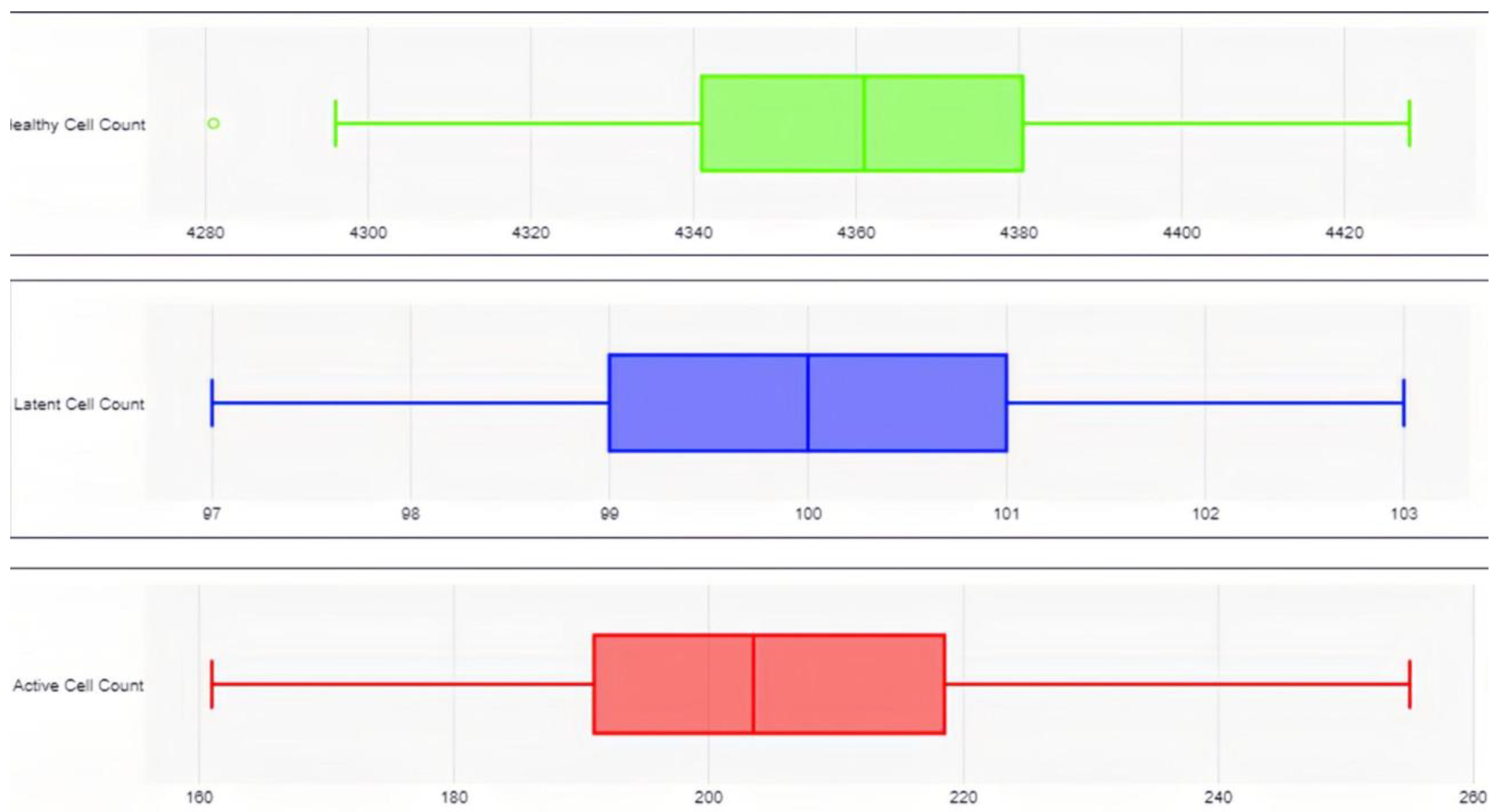

In the cART-only control group, 100 independent trials demonstrated an 8.25% decline in healthy CD4+ T-cells (from 4,750 to 4,358 ± 29.18 cells; paired t-test: t(99) = 134.3, p < 0.0001, 95% CI [387.2, 396.8]), no significant change in the latent reservoir (100 ± 1.07 cells; paired t-test: t(99) = 0, p = 1, 95% CI [-0.21, 0.21]), and a 48.50% reduction in active HIV-1 cells (from 400 to 206 ± 20.22 cells; paired t-test: t(99) = 95.9, p < 0.0001, 95% CI [190.0, 198.0]). These findings align with known cART dynamics seen in experimental studies, where active replication is suppressed but latent reservoirs persist, further validating both models [

2].

In the experimental group, which simulated the novel treatment monotherapy, the results showed a 1.39% increase in healthy CD4+ T-cells (to 4,816 ± 26.01 cells; paired t-test: t(99) = 25.4, p < 0.0001, 95% CI [60.8, 71.2]), a 12% reduction in the latent reservoir (88 ± 3.40 vs. 100 ± 1.07 cells; Mann-Whitney U = 0, p < 0.0001, r = 0.86), and a 93.50% reduction in active HIV-1 cells (26 ± 5.80 vs. 206 ± 20.22 cells; Mann-Whitney U = 0, p < 0.0001, r = 0.86). Notably, all of these changes, from the increased proliferation of healthy CD4+ T-cells to the reduction in the active HIV-1 reservoir were statistically significant.

Comparing the two groups, the experimental treatment resulted in a 10.51% increase in healthy CD4+ T-cells relative to the control (4,816 vs. 4,358 cells; unpaired t-test: t(198) = 123.7, p < 0.0001, 95% CI [451.7, 464.3]), a 12% reduction in the latent reservoir compared to no change in the control, and an 87.38% greater reduction in active HIV-1 cells compared to the control group. In total, it mitigated the total HIV-1 reservoir 72.20% better than the cART-LRA combination therapy.

This statistically significant reduction in the overall HIV-1 reservoir population suggests that the construct effectively clears actively replicating, latent, and reactivated cells. The CD4+ T-cell rebound reflects the impacts of the novel construct on reducing infection spread, thus promoting an increase in healthy cell proliferation.

Although these findings are promising, computational models inherently oversimplify the biological complexity of HIV-1 infection. For instance, our models assume ideal delivery and sustained construct expression which are factors that may vary in vivo. In vivo studies are therefore critical to validate these results, particularly to assess pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of cells expressing the construct and to capture the unpredictability of such HIV-1 systems.

To mitigate the inherent limitations of in silico modeling and establish a robust foundation for experimental validation, we ensured that all control simulations accurately reflected empirical findings. Specifically, we implemented a baseline SBML simulation to isolate the effects of cART on latent and active HIV-1 reservoirs and compare the results to those derived from experimental studies. The simulation demonstrated that cART monotherapy reduced the detectable viral reservoir by 99.84%, a finding consistent with numerous experimental studies [

31,

32]. Notably, the cART-LRA polytherapy model also yielded biologically consistent results, projecting a detectable reservoir reduction of 99.66%, a calculation that closely aligns with the 99.84% projection found in the baseline cART monotherapy simulation. These close alignments corroborate experimental evidence that LRA administration alongside cART does not significantly alter the HIV-1 viral reservoir [

15]. Similarly, control simulations for the ABM model exhibited strong concordance with experimental data, as previously mentioned. By validating these control models against established benchmarks, we ensured confidence in our experimental simulations, wherein the only variables that changed were those associated with the novel therapeutic intervention, whose parameters were also derived from empirical data [

33,

34,

35].

An additional consideration in the development of novel HIV-1 therapeutics is off-target cytotoxicity [

36]. While the HIV-1 LTR promoter provides a degree of HIV-1 specific targeting, there remains a potential risk of unintended apoptosis in uninfected cells. Further experimental validation is therefore required to assess the construct’s specificity and quantify any collateral cytotoxicity. However, it is also important to note that existing research on DTA demonstrates a low incidence of off-target effects coupled with a high cytotoxic efficacy against infected cells. Given that unintended cytotoxicity in shock-and-kill strategies primarily stems from the lytic mechanism (in this case DTA), these findings suggest that the proposed therapy is unlikely to exhibit significant off-target effects [

37,

38]. Nevertheless, in vitro and in vivo studies remain essential to confirm its safety profile.

Beyond off-target toxicity, the emergence of viral resistance represents a substantial challenge in contemporary HIV-1 therapeutics [

17]. The high mutation rate of HIV-1 raises the concern that genetic variants with altered LTR sequences could evade construct recognition, thereby compromising treatment efficacy. While we have included rate constants for HIV-1 LTR mutations in the SBML models (see

Appendix A.7), HIV-1 mutations are unpredictable and vary from cell to cell making it hard to predict the probability that a mutation will occur that hampers the efficacy of the novel treatment [

39]. However, our calculated mutation rate is an overestimation which serves to provide a degree of certainty for the result.

Beyond off-target toxicity, the potential for viral resistance remains a significant challenge in contemporary HIV-1 therapeutics. Given the high mutation rate of HIV-1, there is concern that genetic variants with altered LTR sequences would enable HIV-1 to evade construct recognition, ultimately diminishing treatment efficacy. While our SBML models incorporate rate constants for HIV-1 LTR mutations (see

Appendix A.7), the stochastic nature of viral mutations makes it difficult to precisely determine the likelihood of resistance-compromising mutations. However, our calculated mutation rate represents a deliberate overestimation, providing a conservative framework that enhances the robustness of our findings. Additionally, CRISPR-based approaches for HIV treatment are inherently more vulnerable to viral mutations due to their dependence on precise DNA sequence recognition [

40]. Given HIV’s exceptionally high mutation rate, empirical studies have demonstrated the rapid emergence of CRISPR-resistant HIV-1 strains, as even single-nucleotide variations can disrupt Cas9 target recognition [

23,

28]. In contrast, the novel construct is structurally simpler and less susceptible to resistance development since the primary avenue for potential resistance is limited to mutations within the LTR sequence, significantly narrowing the potential for viral escape.

Finally, from a translational perspective, delivery optimization is paramount. Current gene therapy platforms face practical barriers such as vector size limitations and immunogenicity [

25,

41]. Ensuring scalable, cost-effective delivery will be crucial for advancing this therapeutic toward clinical trials. In line with several other shock-and-kill strategies, we propose a lentiviral vector to be developed for effective delivery of this construct. Their efficiency in transducing non-dividing cells makes them well-suited for targeting latent HIV reservoirs. [

6,

23].

Our study demonstrates that the HIV-1 LTR-driven therapeutic construct achieves significant viral reservoir depletion by directly targeting both actively infected and latent cells. SBML kinetic modeling and ABM simulations consistently revealed a substantial reduction in the total and detectable HIV-1 reservoir, alongside a marked increase in healthy CD4+ T-cell populations – an outcome not observed with the cART-LRA polytherapy. Sensitivity analyses further highlighted the construct’s mechanistic advantages, showing that its efficacy scales with improvements in latency reversal, unlike cART-LRA therapy, which paradoxically expands the reservoir under enhanced LRA potency. While concerns regarding off-target toxicity and viral resistance remain, existing evidence suggests that the construct exhibits a high degree of specificity and is less prone to resistance emergence compared to CRISPR-based approaches. Although further in vitro and in vivo studies are essential to validate these findings, particularly in optimizing delivery mechanisms and assessing long-term efficacy, this study represents a significant advancement in the development of a scalable and durable HIV-1 eradication strategy.