1. Introduction

Natural language processing (NLP) has become an essential component of modern machine learning, with applications ranging from chatbots to machine translation, sentiment analysis, and information retrieval. The success of these applications depends on the ability of language models to process the text accurately. In the past few years, large-scale pretrained models such as BERT [

1], RoBERTa [

2], and GPT-3 [

3] have demonstrated impressive performance on a wide range of NLP tasks. Nonetheless, these models are insufficient on their own to achieve optimal performance. We often need to fine-tune them on a smaller set of task-specific examples for better downstream results. This process requires full forward and backward propagation through the model and is computationally expensive. Thus,

prompt tuning is proposed to remove the need for updating all model parameters by constructing natural language prompts to elicit specific behavior from the pretrained model [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Specifically, prompts are input texts or questions that are given to the language model to generate corresponding outputs or answers. In prompt tuning, the goal is to find the most effective prompts that will produce the desired outputs of the target task. Manually designing prompts requires extensive domain knowledge and can have high variance. Previous work has shown that changing only one word in a prompt can result in drastically different downstream performance [

3]. As a result,

soft prompt tuning is proposed to learn the prompts in an end-to-end fashion [

4], which is both more parameter-efficient than standard fine-tuning and more effective than existing prompt tuning methods.

While soft prompt tuning has proven to be effective for many applications, it raises concerns about privacy. Indeed, if the data used to learn the prompts contain sensitive information about individuals or organizations represented in the data, the prompt tuning process risks revealing this information to attackers who carefully inspect the learned prompts. Several lines of research have been proposed to address the privacy issue. In particular, differential privacy (DP) has gained significant attention as it provides strong theoretical privacy guarantees [

10]. However, none of the previous work have studied DP in the context of prompt tuning for large-scale pretrained language models.

In this work, we explore how DP can be integrated into the soft prompt tuning framework to develop privacy-preserving language models. Our goal is to strike a balance between parameter efficiency, downstream accuracy, and data privacy. We begin by learning the prompts via DP optimization [

11] and compare it with vanilla fine-tuning and soft prompting on the SuperGLUE benchmark [

12]. Then, we propose techniques to improve the performance of DP prompt tuning. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2 and

Section 3, we provide background information about prompt tuning and differential privacy and survey the related work. Next, we describe our proposed approach of adding DP to soft prompt tuning. In

Section 5, we present our experiment results. We end the paper with a discussion on the limitations and future work of DP prompt tuning.

2. Background

As discussed earlier, fine-tuning or soft prompting the pretrained language models with task-specific datasets is vulnerable to adversarial attacks. One way to mitigate this is to apply differential privacy techniques such as DG-SGD [

11]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no work exploring the integration of DP learning and prompting for language modeling, which motivates our work.

In the midway report, we have implemented vanilla fine tuning and vanilla soft prompt tuning for the T5-small model on the RTE task of the SuperGLUE benchmark. These two methods provide baseline performance for our proposed approach. Our initial experiments reveal the following:

In the setup of the T5-small model tuning, prompt tuning is less effective compared with fine-tuning. The latter updates all parameters but sacrifices learning efficiency.

There is still room to further improve prompt tuning if we can tweak the hyperparameter configurations of the optimizer or allow sample-wise prompts.

In the final report, we make additional contributions on top of the above-mentioned findings:

We extend previous experiments on the RTE task to all tasks in the SuperGLUE benchmark to make a more comprehensive comparison.

We implement DP optimization, which preserves privacy during modeling learning, and combine it with soft prompt tuning. We evaluate this new approach on various tasks and perform thorough ablation studies to understand the privacy-accuracy trade-off.

We propose several improvements for DP prompt tuning and verify their efficacy.

3. Related Work

3.1. Language Modeling and Prompt Tuning

Although recent advancements in pretrained language models have gain great success, heavy computation in the fine-tuning process has impeded their potential for wider applications. To reduce the computational cost, prompting becomes a widely used technique for conditioning frozen models. Recent work has shown the potential of prompt design. For instance, careful design of input text prompts is effective at modulating a frozen GPT-3’s behaviors [

3,

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, the text prompts are normally task descriptions or canonical examples, which require human efforts to design and tend to be erroneous. The performance is also less satisfying compared with fine-tuned models—it has been shown that a frozen GPT-3 with 175 billion parameters performs 5 points worse than a fine-tuned T5 model with 800 times fewer parameters on the SuperGLUE Benchmark [

9].

One way to reduce the human involvement is to automate the prompt design process. Previous work has proposed to search over the discrete word space using downstream task data [

6,

17,

18,

19]. However, while the performance of the automated approach is better than hard-coded prompts, it still somewhat falls behind full fine-tuning of all model parameters.

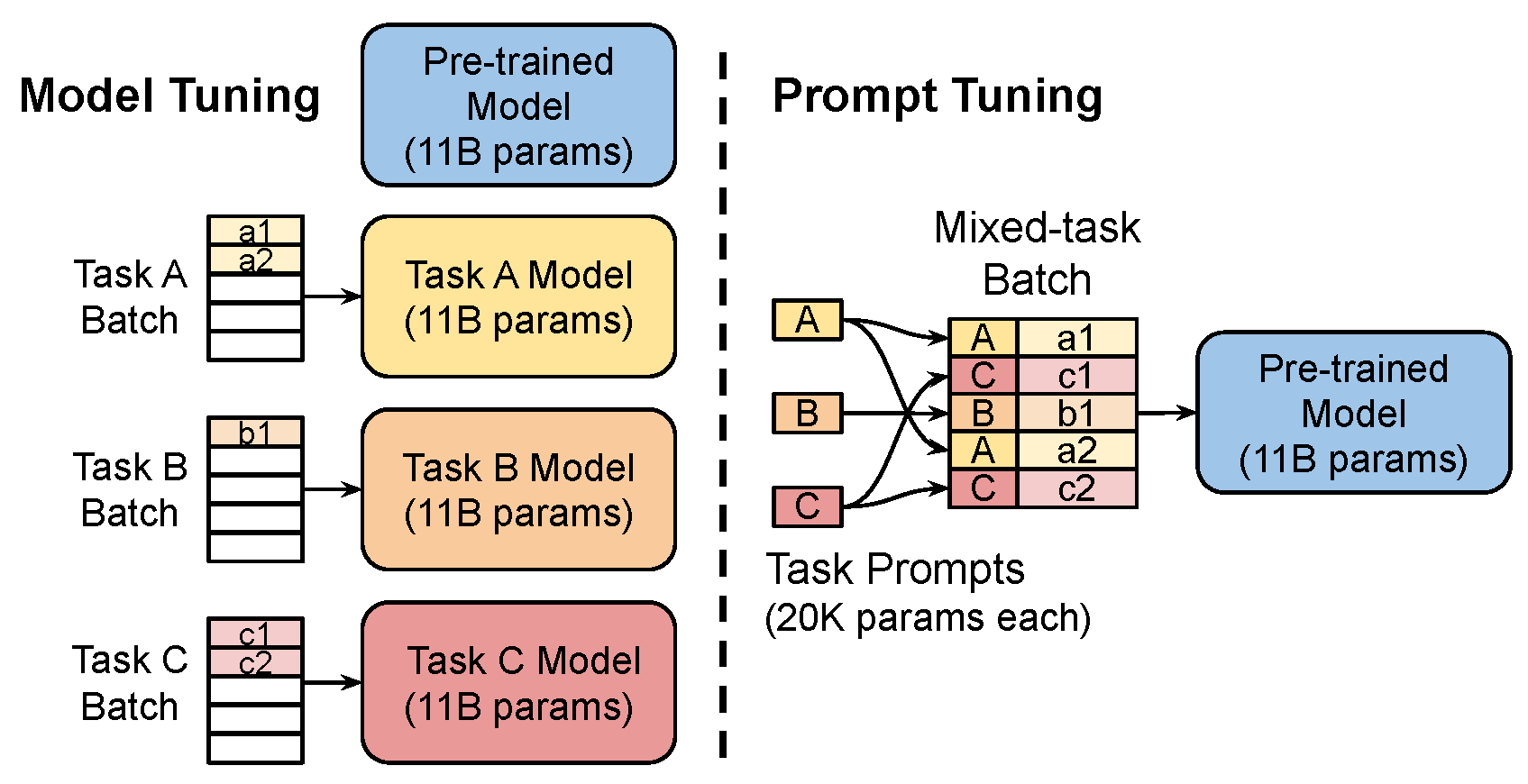

As a result, prompt tuning is proposed to condition frozen models using learnable soft prompts (

Figure 1) [

4,

5,

8,

20,

21,

22]. Unlike hand-designed prompts that are selected from existing vocabulary items, the “tokens” of the soft prompt can be optimized end-to-end over a training dataset to condense information from large datasets. These tokens are then concatenated to the input text to generate the desired outputs. Recent work has studied how soft prompt tuning can be improved. For instance, prefix tuning [

8] learns continuous task-specific vectors prepended to the inputs of the frozen model via back-propagation and demonstrates good results on generative tasks. However, this continuous prefix-based learning paradigm is very sensitive to the learning rate and initialization. Another line of work focuses on exploring different initialization schemes, e.g., via discovered discrete vocabularies [

5], to improve task accuracy. In this work, we build on top of the soft prompt tuning algorithm [

4] and inject privacy guarantees into it.

3.2. Differential Privacy

The concept of differential privacy was proposed to achieve privacy preservation of individuals in a database with a mathematical guarantee [

10]. To make a model differentially private, a randomization mechanism should be designed so that the randomized model guarantees

-Differential Privacy (DP) for any possible outputs. A model is considered

-DP if it satisfies:

where

D and

denotes two datasets differing in only one record, and

and

are two non-negative values parameterizing the mathematical guarantee.

is also known as the privacy budget—the probability ratio of outputting the same results with the neighboring datasets

D and

is bounded by

.

indicates the tolerance probability that the output ratio goes beyond the bound. The smaller

and

are, the stronger the private protection is against adversarial attacks. As

-DP is achieved by adding noise to the model, selecting

faces a trade-off between privacy preservation and the utility. That is, a tight bound with too much noise can make the model useless, while a loose bound with too little noise may weaken the privacy protection.

Plentiful research has been conducted to explore methods preserving differential privacy in ML. These approaches can be categorized as following. Some methods add noise on top of clean models to release noisy model with DP guarantees [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Some output the model at the minimum/maximum of a noisy target function [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Some leverage the idea of aggregating sampled models with noise to generate a DP model [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Among these different types of approaches, a common and easy-to-use one is DP-SGD [

11]. With a pre-defined set of

, DP-SGD clips the gradients gradients by

norm and adds noise to the gradients in each iteration.

In light of works that combine DP with NLP, Lyu et al. propose to provide a DP guarantee by perturbing binary vector text representations [

36]. Weggenmann et al. create synthetic term frequency vectors for the input documents that can be used in lieu of the original text vectors to achieve text anonymization [

37]. Beigi et al. introduce a discriminator in a two-auto-encoder setting to approach the privacy-accuracy trade-off [

38]. Yu et al. use a customized DP-SGD method to train deep language models [

39]. Nonetheless, none of the previous approaches have explored integrating DP learning into prompting for language modeling.

4. Methods

In this project, we aim to combine DP with prompt tuning to achieve privacy-preserving language modeling. Following previous work [

4], we build our method on top of the pretrained T5-small model (we leave experimenting with larger models as future work due to computational constraints). We leverage the public T5.1.1 checkpoints, as it is shown to have less variance and yield higher performing models. For the baselines, we evaluate (1) vanilla fine-tuning and (2) vanilla soft prompt tuning. Then, we implement soft prompt tuning with differentially private optimizers and propose improvements on top of it to complete the project. Now, we illustrate each method in detail.

4.1. Vanilla Fine-Tuning

To establish the baseline performance, we fetch a pretrained T5-small model and update all parameters by further training it on each dataset. This vanilla fine-tuning approach provides an initial assessment of the model’s capability on the downstream task and serve as a baseline for our proposed method.

4.2. Vanilla Soft Prompt Tuning

To approach prompt tuning from a differential privacy perspective, we start by reproducing the soft prompt tuning algorithm on the T5 model. Formally, given a series of tokens , T5 first embeds the tokens into sequence features , where e is the embedding dimension, i.e., 512 in our case. To soft-prompt the pretrained model, we prepend with a learned parameter , where p is a tunable hyperparameter and denotes the length of the prompt. Hence, the embedded input used to query the transformer is . Note that is learned on a per-task basis, so it is fixed for different training samples.

Denote the sequence of tokens representing the class label as Y. Then, is learned to optimize using the cross entropy loss. Note that the gradient updates are only applied to to the learnable prompt, and the core model is kept frozen. At test time, we generate the prediction with the maximum probability using greedy search or beam search.

4.3. Our Approach: DP Prompt Tuning

As discussed in the introduction, we propose to combine the differential privacy optimization with the soft prompt tuning algorithm and then study whether we can make improvements to achieve a better accuracy-privacy trade-off. Transformers are typically trained using AdamW [

40] or Adafactor [

41]. Thus, we start by augmenting these optimizers with privacy-preserving components. Though the original DP paper focuses on DP-SGD, the techniques used are optimizer-agnostic. Specifically, there is an inner loop (mini-batch) and an outer loop (micro-batch) for optimization.

In the inner loop, instead of actually performing gradient descent, we accumulate the gradients of the mini-batch samples. Based on the gradient norms, we scale the gradients and perform gradient clipping to limit the impact of any single example on the gradients.

In the outer loop, we add Gaussian noise to the accumulated gradients, average them across all mini-batches, and then perform gradient descent. The Gaussian noise provides additional privacy by making it more difficult to recover the true gradients in each optimization step.

Based on the above techniques, we implement a DP wrapper in PyTorch that can take any optimizer class as input and output the DP version of it. Specifically, the constructor specifies several hyperparameters such as the norm-clipping threshold c, the noise multiplier , and the mini/micro-batch sizes. We rewrite the step and the zero_grad functions to account for gradient normalization, clipping, and the added noise. In the next section, we will perform ablation studies on different hyperparameters of DP optimization.

After obtaining the DP optimizers, we can then train the prompts with it, so that we adapt to the downstream task without revealing much information about the training data. However, as we will show later, naively applying DP learning to prompt tuning noticeably degrades the performance. Therefore, we propose improvements to strike a balance between model effectiveness and privacy.

5. Results

In the following, we detail the experiments we have performed and discuss the results. For the evaluation tasks, we use the SuperGLUE benchmark [

12], a collection of eight challenging language understanding datasets designed to be summarized into a single metric. Due to memory issues, we did not evaluate the ReCoRD task, so there are seven tasks in total for our experiments. To fit the classification tasks in the SuperGLUE benchmark into T5’s text-to-text framework, we formulate these classification problems as text-to-text problems (see

Appendix A.1 for an example). For each dataset, we use the metric specified in the benchmark (classification accuracy or F1 score). We reuse the evaluation code from the publicly available T5 release

1 to compute these metrics. Our code can be found at

https://github.com/sjunhongshen/DP-SoftPromptTuning.

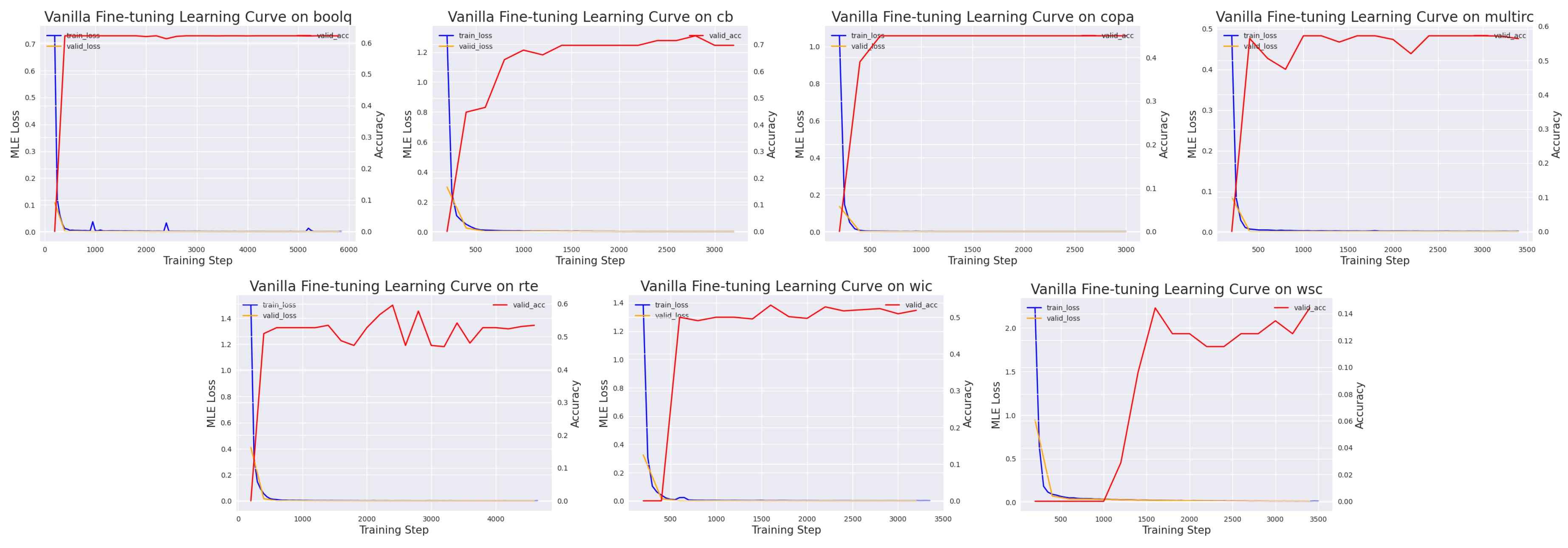

5.1. Fine-Tuning

We first run the fine-tuning baseline on T5-small, using the hyperparameters listed in

Appendix A.3. The test losses and accuracies are shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 2, respectively. In principle, the performance of vanilla fine-tuning should serves as an upper bound for the other prompt tuning methods, since we have more degree of freedom for learning a task-specific model. We observe that the accuracy metrics for some of the binary classification tasks are less than 50%. This is normal, as T5-small is a seq2seq model but not a standard classification model. It is likely that the seq2seq output does not correspond to either the true or the false label.

5.2. Soft Prompt Tuning

Next, we evaluate the vanilla prompt tuning algorithm. Following [

4], we train the prompts for 100 epochs using a batch size of 32. We use the Adafactor optimizer [

41] and the linear warm-up scheduler with a warm-up step of 500. Since the

official implementation of soft prompt-tuning is in JAX but we use the PyTorch framework, we implement the code by ourselves, referring to several

unofficial resources. Other experiment details can be found in

Appendix A.3.

As shown in

Table 1, prompt tuning in general performs worse than fine-tuning, because the number of tunable parameters is much smaller (see

Appendix A.2 for details). However, on the Word-in-Context (WiC) dataset, prompt tuning performs better than fine-tuning, possibly because the training set size is small and fine-tuning does not obtain enough signals to update the weights properly. Next, to conduct a more in-depth analysis on the prompt tuning paradigm, we study how the prompt length and initialization affect downstream performance. For presentation clarity, the following experiments are done on the RTE task only.

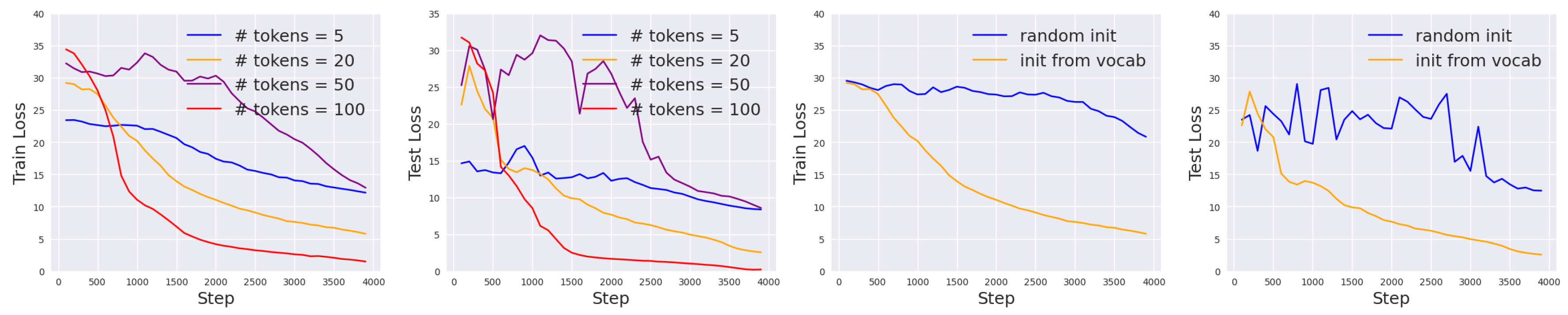

Efficiency-Effectiveness Trade-off for Different Prompt Lengths.

Given that the prompt length

p is tunable, we first experiment with

while holding the other configurations fixed. The loss curves for training and evaluation are shown in

Figure 3 (left). We can observe that increasing prompt length generally leads to a smaller final loss, but the improvement is much smaller when

p goes from 20 to 100 than when

p goes from 5 to 20. In the meantime, using longer prompts means that we have a larger computational and storage cost. Therefore, there is a sweet spot for choosing the optimal prompt length to balance accuracy and efficiency. In our case, we choose

and use this in the subsequent DP experiments.

5.3. DP Prompt Tuning

After implementing the vanilla soft prompt tuning, we proceed with implementing the differential privacy optimizers. As discussed earlier, we implement an optimizer wrapper that takes in an arbitrary optimizer class, such as SGD, AdamW, or Adafactor, and outputs the DP version of it. Therefore, compared to the vanilla prompt tuning workflow, the DP workflow only requires an addition step to wrap the optimizer. In the default setting, we optimize the cross-entropy loss using the Adafactor optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-3. The prompts are trained for 100 epochs. The mini-batch size is 32 (inner loop) and the micro-batch size is 320 (outer loop). Note that these hyperparameters are not perfect, i.e., we do not do extensive hyperparameter tuning due to compute limitations. However, we believe that we can already make a lot of interesting observations in this controlled setting.

Before studying the effect of each DP component, we first present the overall results of DP prompt tuning on the SuperGLUE tasks (

Table 1, bottom row). We see that the final losses are higher than vanilla prompt tuning except for the CB and WSC tasks. This performance loss is due to the improved privacy during learning. In the following, we first analyze the privacy gain in theory and then perform ablation studies on each DP component to get a better sense of the privacy-accuracy trade-off.

5.3.1. Theoretical Perspective: Is Privacy Preserved After Using the DP Optimizer?

Similar to the DP-SGD paper, we use the

-differential privacy framework (Equation

1) to analyze whether our optimizers achieve the desired properties. In our experiments, we set

1e-5. We calculate

for gradient descent based on

, noise scale, number of examples, batch size, and number of epochs. We report

for different noise scales:

|

noise scale

|

achieved

|

| 0.01 |

3.8e9 |

| 0.1 |

2.1e5 |

| 1 |

18 |

Just as we have expected, the larger the noise added to the gradients, the more privacy we obtain. Based on the theoretical work in [

11], we conclude that the DP optimizers can indeed lead to better privacy for the training data. Next, we study three factors that affect the learning outcome under the DP framework—noise perturbation, gradient clipping, and gradient accumulation.

5.3.2. Empirical Perspective: Privacy-Accuracy Trade-off

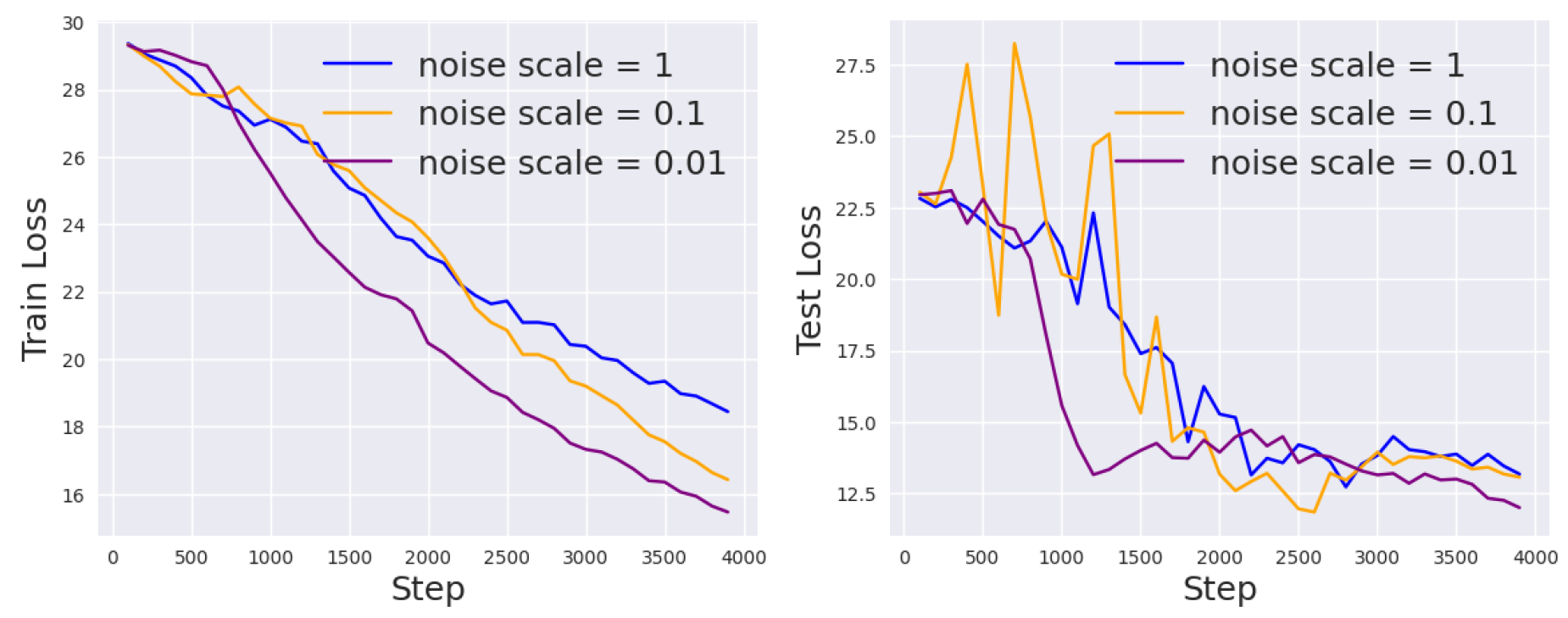

Noise Scale

First, we specifically study the effect of different noise scales on the model performance. As motivated earlier, the larger the noise scale, the more privacy we preserve for the training data, but the more difficult the optimization process becomes.

Statistically, a Gaussian noise distribution with higher variance will have more spread, making it less likely that a gradient update value comes from its immediate vicinity, thereby making it harder to model the unnoised gradient. In the most extreme cases, if the noise is arbitrarily close to a point mass, then an adversary will be able to obtain a very good estimate of the true gradient. On the other hand, if the variance of the noise goes to infinity, then no useful information is conveyed in the gradient and no learning happens. The above analysis is supported by

Figure 4, where we fix the other hyperparameters but tune the noise scale so that

. Indeed, as

becomes smaller, the performance for DP prompt tuning becomes better, but the privacy guarantee becomes weaker.

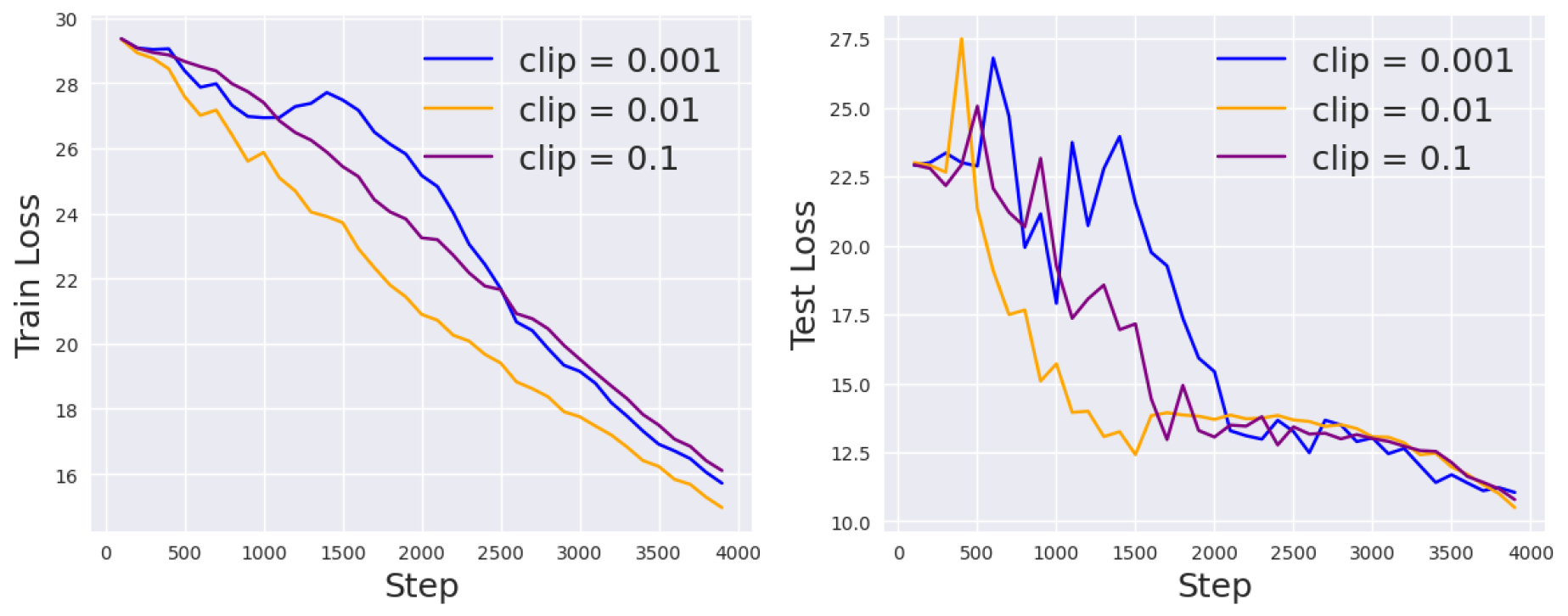

Gradient Clipping

The second factor we investigate is the clipping threshold

c, which regularizes the gradients and prevents a single training example from contributing too much to learning the parameters. For ablation study, we fix the noise scale and vary

. The results on the RTE task are shown in

Figure 5. Evidently, using a small clipping threshold will slow down the convergence rate but make the learning curve more stable.

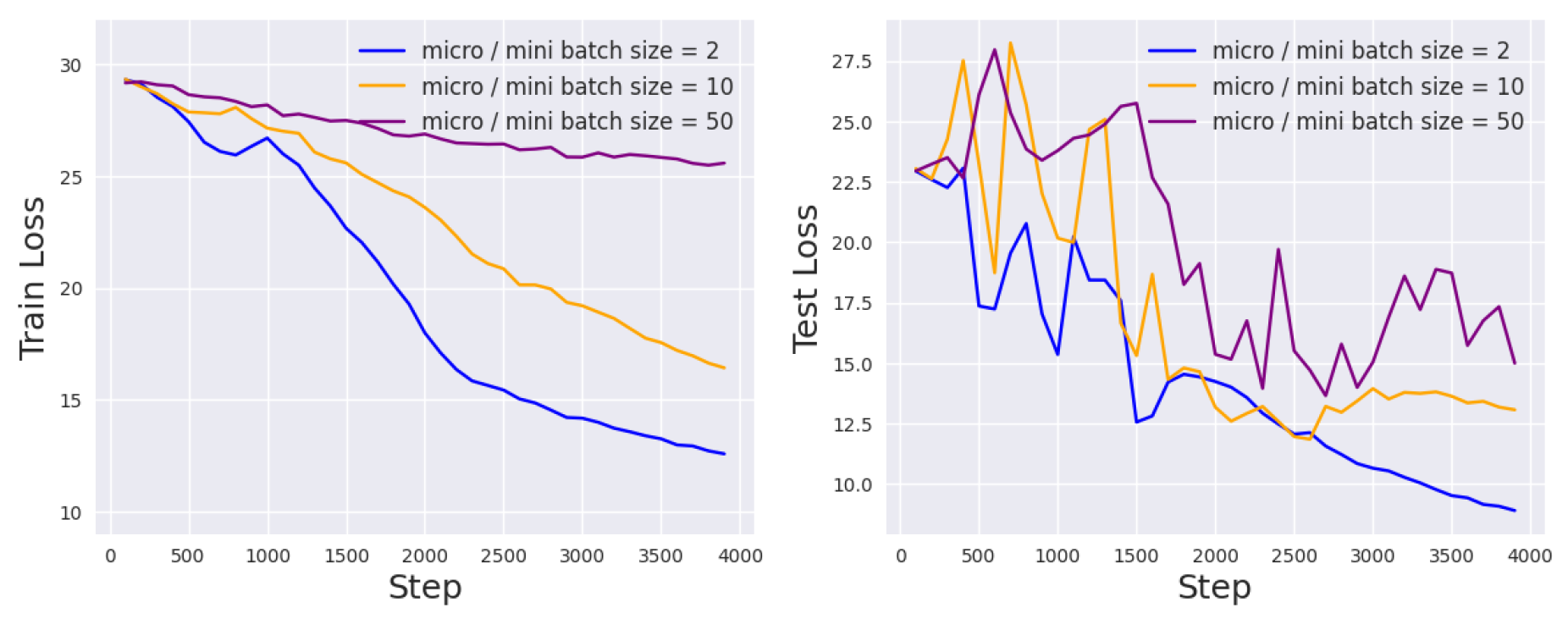

Micro-Batch Size

Lastly, we study the effect of the micro-batch size, which determines whether we accumulate individual gradients or averaged gradients in the inner loop optimization. While differentially private optimization of convex objective functions is best achieved using batch sizes as small as 1, non-convex learning, which is inherently less stable, benefits from aggregation into larger batches. Also, Theorem 1 in [

11] suggests that making batches too large increases the privacy cost, and a reasonable trade-off is to take the number of batches per epoch to be of the same order as the desired number of epochs.

In

Figure 6, we plot the learning curves for different micro-batch sizes, while the mini-batch size is fixed to 32. We see that for DP-Adafactor, the best micro-batch size is 64. Note that increasing micro-batch size in spirit hurts privacy: clipping the gradient limits the impact of each example on the gradient update, and aggregating more samples before clipping lessens this effect.

Summary

To sum up, when we use larger noise scale, smaller gradient clipping threshold, and larger micro-batch size, we obtain a more privacy-preserving model, but the cost is that we may sacrifice learning accuracy and computational efficiency.

5.3.3. Proposed Improvements: Mitigating Privacy-Accuracy Trade-off

In this section, we introduce several remedies for the privacy-accuracy trade-off based on previous observations. Specifically, we notice that the test loss decreases more rapidly at the beginning, which means that the size of the gradient update steps is larger in the earlier epochs. This makes sense intuitively—starting from a randomly initialized point in the parameter space, we would first expect gradient descent to lead us to a region where the local optimum roughly resides. Then, via more precise optimization, we can arrive at the exact optimal point. Such a hierarchical optimization process makes us wonder whether we can also do privacy enhancement in a hierarchical way as well.

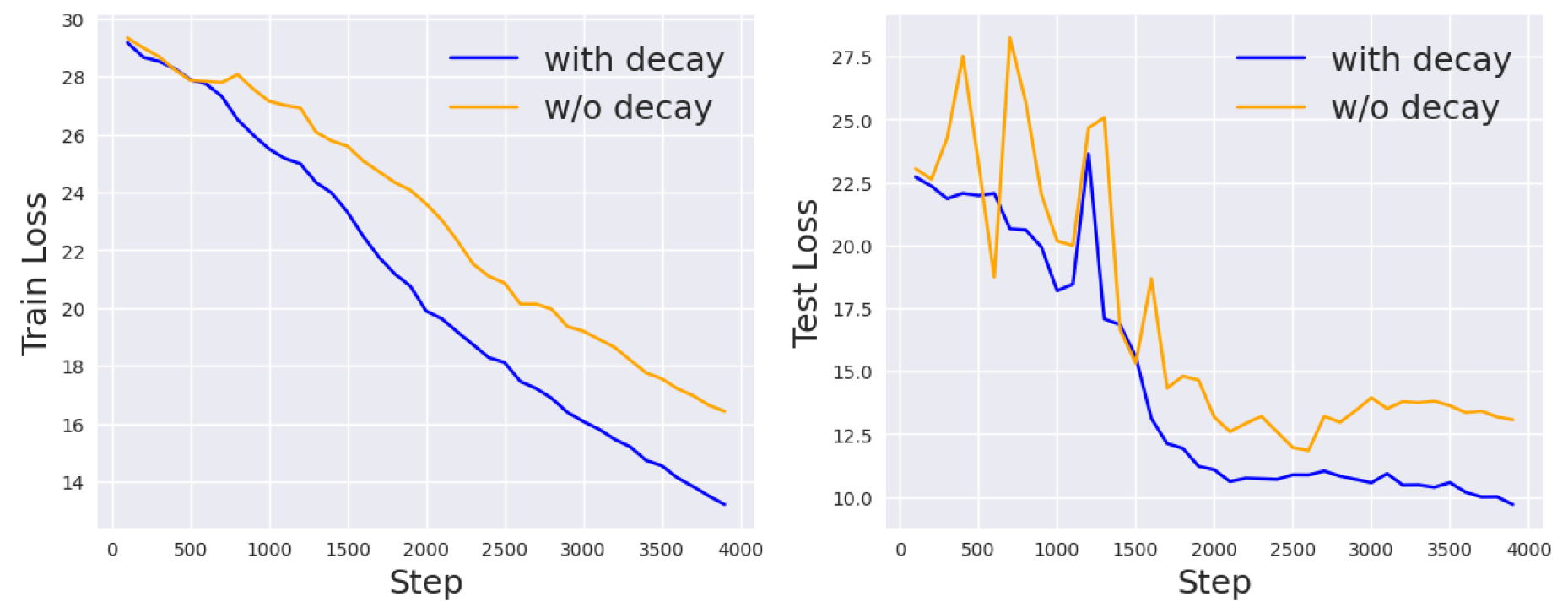

Hierarchical Privacy Learning

We propose to decrease the privacy requirements in the

-differential privacy framework at different stages of training. The intuition is that gradient updates at the beginning of training will have a larger effect on the final learned parameters, so we want to make sure that enough privacy constraints, such as the random noise, are added at each step. However, at the later stage of training, the gradient scales are already small, and adding the same amount of noise as the beginning stage might distort the learned weights, leading to slower convergence or worse performance. Therefore, we might want to loosen the privacy constraints to achieve better accuracy. To test this idea, we follow the previous experiments to initialize the noise scale

and gradient clipping threshold

c. Then, we add linear decay for both

and

so that they approach 0 at the end of training. Th results are shown in

Figure 7. Compared to the original DP setting, the linear decay setting achieves better results.

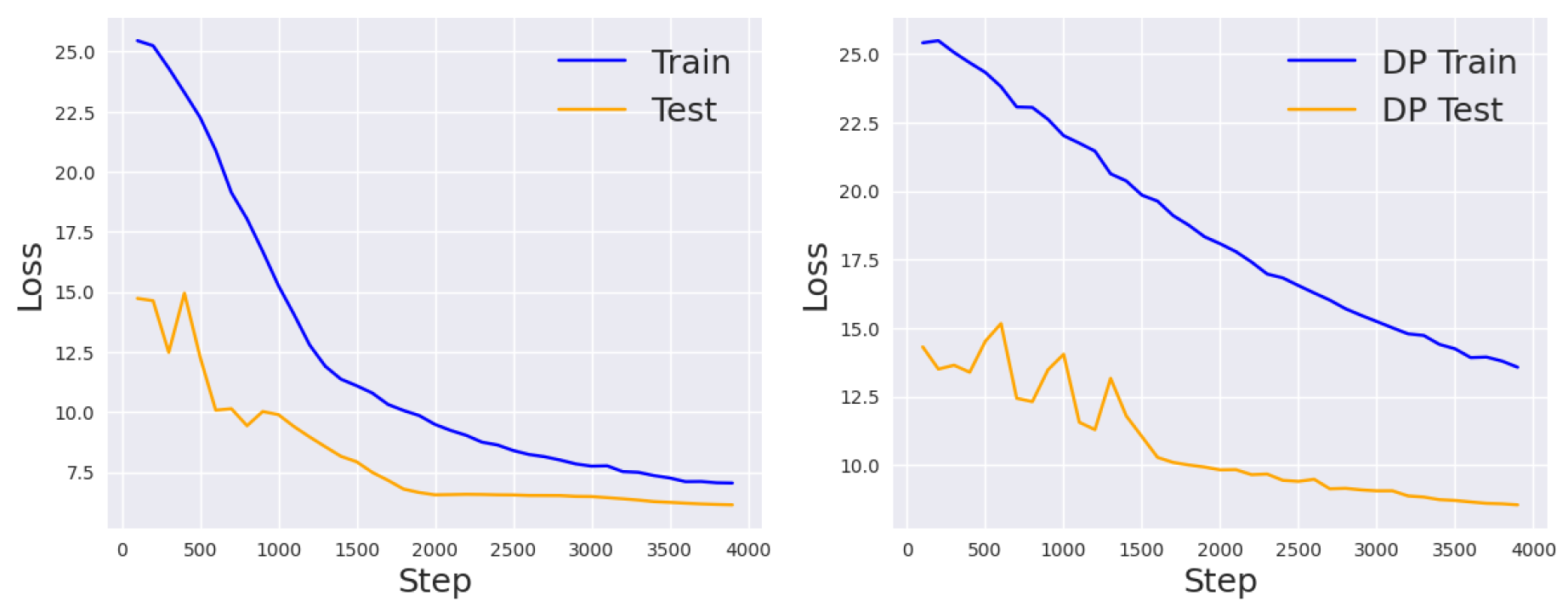

Strategic Initialization

To generally improve prompt tuning, we also propose to use a more informative initialization scheme than the random or vocabulary initialization. In particular, the latter methods do not give any information about the task of interest, and we indeed observe that it takes a long time for the model to output relevant class labels, regardless of whether the labels are correct or not. Thus, given the class labels

in words, we propose to initialize the prompts in the following format “

or

or

.” In

Figure 8, we show the learning curves of this new strategy for both the DP and non-DP settings. Compared with

Figure 3 (right), we see that the performance improve for both settings.

6. Discussion and Analysis

6.1. Limitations

In the previous section, we showed the performance of fine-tuning and soft prompt tuning on the SuperGLUE tasks. We make the following observations. First, compared with fine-tuning, where all model parameters are allowed to be updated, prompt tuning is less effective. In particular, the loss scale of prompt tuning is an order of magnitude larger than the loss achieved by fine-tuning. This shows that, at least for the T5-small model, adapting as many parameters as possible is preferred for getting better performance, though this sacrifices learning efficiency. However, it is unknown whether larger models will close the gap between fine-tuning and prompt tuning.

Second, soft prompt tuning can be improved in several ways. For instance, we have observed that the optimizer and scheduler configuration can have a great impact on the learning curve, so it might be beneficial to apply hyperparameter search algorithms such as ASHA [

42,

43,

44] before tuning the prompts. Besides, in the current approach, the learned soft prompts are the same for all samples in the target dataset. One solution is to learn sample-dependent prompts by learning a prompt generator network.

Lastly, as we have expected, adding DP further decreases the downstream performance due to the added noise and the gradient clipping scheme. Even though we have proposed several solutions, we have not verified how they affect the -framework theoretically. Therefore, it remains an open question how we can further improve the current DP learning framework for prompt tuning and justify the method in theory.

6.2. Future Work

In this study, we propose the idea of a privacy-preserving soft prompt tuning that upholds data privacy without compromising much downstream accuracy. The motivation behind this framework is to identify an optimal equilibrium point among downstream accuracy, fine-tuning parameter efficiency, and privacy considerations in language models. In the current report, we have evaluated the proposed method thoroughly. However, there are still improvements we can make based on the existing work. First, we can try more optimizer classes, such as Adam or AdamW, to determine the most effective one for our framework. Besides, we can investigate the effect of using different sizes of T5 models on the performance of our method. More importantly, we can combine more recent work that applies DP learning to non-language settings with prompt tuning. Hopefully, there is a way to balance the privacy and accuracy of the learned model for language modeling tasks.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Formulating Classification Problems in SuperGLUE to Text-to-Text Problems

The following is an example for the RTE task:

input: hypothesis: Bacteria is winning the war against antibiotics. premise: Yet, we now are discovering that antibiotics are losing their effectiveness against illness. Disease-causing bacteria are mutating faster than we can come up with new antibiotics to fight the new variations.

output: entailment

Appendix A.2. Parameter Counts for Prompting T5-Small

Table A1.

Number of parameters used for various prompt lengths on the T5-small model. Trainable parameters is the number of parameters in the prompt itself, while total parameters includes the prompt plus the original T5 parameters. The rightmost column is the percentage of total parameters that are trainable.

Table A1.

Number of parameters used for various prompt lengths on the T5-small model. Trainable parameters is the number of parameters in the prompt itself, while total parameters includes the prompt plus the original T5 parameters. The rightmost column is the percentage of total parameters that are trainable.

| T5 Size |

Prompt Length |

Trainable Parameters |

Total Parameters |

Percent Trainable |

| Small |

5 |

|

|

% |

| |

20 |

|

|

% |

| |

50 |

|

|

% |

| |

100 |

|

|

% |

Appendix A.3. Experiment Details

Appendix A.3.1. Hyperparameters for Fine-Tuning

For every dataset, we use the

google/t5-v1_1-small checkpoints and train the model using a batch size of 8. In general, we make sure that each dataset is trained for at least 3000 steps at a batch size of 8 to ensure reasonable convergence. We use the AdamW optimizer with weight decay

and learning rate

. Please refer to

Table A2 for epochs and steps trained for each task.

Table A2.

Number of epochs and steps trained for each task.

Table A2.

Number of epochs and steps trained for each task.

| Dataset |

Epochs |

Steps |

| BoolQ |

5 |

5895 |

| CB |

100 |

3200 |

| COPA |

60 |

3000 |

| MultiRC |

1 |

3406 |

| RTE |

15 |

4695 |

| WiC |

5 |

3000 |

| WSC |

50 |

3500 |

Appendix A.3.2. Hyperparameters for Prompt Tuning and DP Prompt Tuning

Following [

4], we train the prompts for 100 epochs using a batch size of 32. We use the Adafactor optimizer with the default hyperparameter configuration and the linear warm-up scheduler with a warm-up step of 500.

For the DP setting, we set the gradient clipping threshold c to 1 and the noise scale to 0.1. The mini-batch size is 32 and the micro-batch size is 320.

Appendix A.3.3. SuperGLUE Fine-Tuning Accuracy

Table A3.

Fine-tuning accuracy for 7 tasks in the SuperGLUE benchmark.

Table A3.

Fine-tuning accuracy for 7 tasks in the SuperGLUE benchmark.

| Dataset |

BoolQ |

CB |

COPA |

MultiRC |

RTE |

WiC |

WSC |

| Fine-Tuning |

0.6217 |

0.7321 |

0.4500 |

0.5720 |

0.5957 |

0.5329 |

0.1442 |

References

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. CoRR, abs/1810.04805, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yinhan Liu, Myle Ott, Naman Goyal, Jingfei Du, Mandar Joshi, Danqi Chen, Omer Levy, Mike Lewis, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Veselin Stoyanov. Roberta: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. CoRR, abs/1907.11692, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tom B. Brown, Benjamin Mann, Nick Ryder, Melanie Subbiah, Jared Kaplan, Prafulla Dhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Sandhini Agarwal, Ariel Herbert-Voss, Gretchen Krueger, T. J. Henighan, Rewon Child, Aditya Ramesh, Daniel M. Ziegler, Jeff Wu, Clemens Winter, Christopher Hesse, Mark Chen, Eric Sigler, Mateusz Litwin, Scott Gray, Benjamin Chess, Jack Clark, Christopher Berner, Sam McCandlish, Alec Radford, Ilya Sutskever, and Dario Amodei. Language models are few-shot learners. ArXiv, abs/2005.14165, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Brian Lester, Rami Al-Rfou, and Noah Constant. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. CoRR, abs/2104.08691, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Karen Hambardzumyan, Hrant Khachatrian, and Jonathan May. WARP: Word-level Adversarial ReProgramming. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4921–4933, Online, August 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Taylor Shin, Yasaman Razeghi, Robert L. Logan IV, Eric Wallace, and Sameer Singh. AutoPrompt: Eliciting Knowledge from Language Models with Automatically Generated Prompts. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 4222–4235, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Junhong Shen, Neil Tenenholtz, James Brian Hall, David Alvarez-Melis, and Nicolo Fusi. Tag-llm: Repurposing general-purpose llms for specialized domains, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Lisa Li and Percy Liang. Prefix-tuning: Optimizing continuous prompts for generation. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4582–4597, Online, August 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Colin Raffel, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J. Liu. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 21(140):1–67, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cynthia Dwork. Differential privacy. In 33rd International Colloquium on Automata, Languages and Programming, part II (ICALP 2006), volume 4052 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 1–12. Springer Verlag, July 2006.

- Martin Abadi, Andy Chu, Ian Goodfellow, H. Brendan McMahan, Ilya Mironov, Kunal Talwar, and Li Zhang. Deep learning with differential privacy. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. ACM, oct 2016.

- Alex Wang, Yada Pruksachatkun, Nikita Nangia, Amanpreet Singh, Julian Michael, Felix Hill, Omer Levy, and Samuel R. Bowman. Superglue: A stickier benchmark for general-purpose language understanding systems. ArXiv, abs/1905.00537, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Luyao Yuan, Zipeng Fu, Jingyue Shen, Lu Xu, Junhong Shen, and Song-Chun Zhu. Emergence of pragmatics from referential game between theory of mind agents, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Luyao Yuan, Dongruo Zhou, Junhong Shen, Jingdong Gao, Jeffrey L Chen, Quanquan Gu, Ying Nian Wu, and Song-Chun Zhu. Iterative teacher-aware learning. In M. Ranzato, A. Beygelzimer, Y. Dauphin, P.S. Liang, and J. Wortman Vaughan, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 34, pages 29231–29245. Curran Associates, Inc., 2021.

- Junhong Shen, Liam Li, Lucio M. Dery, Corey Staten, Mikhail Khodak, Graham Neubig, and Ameet Talwalkar. Cross-modal fine-tuning: align then refine. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023.

- Junhong Shen, Tanya Marwah, and Ameet Talwalkar. Ups: Towards foundation models for pde solving via cross-modal adaptation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07187, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Junhong Shen, Mikhail Khodak, and Ameet Talwalkar. Efficient architecture search for diverse tasks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Renbo Tu, Nicholas Roberts, Mikhail Khodak, Junhong Shen, Frederic Sala, and Ameet Talwalkar. NAS-bench-360: Benchmarking neural architecture search on diverse tasks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) Datasets and Benchmarks Track, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas Roberts, Samuel Guo, Cong Xu, Ameet Talwalkar, David Lander, Lvfang Tao, Linhang Cai, Shuaicheng Niu, Jianyu Heng, Hongyang Qin, Minwen Deng, Johannes Hog, Alexander Pfefferle, Sushil Ammanaghatta Shivakumar, Arjun Krishnakumar, Yubo Wang, Rhea Sanjay Sukthanker, Frank Hutter, Euxhen Hasanaj, Tien-Dung Le, Mikhail Khodak, Yuriy Nevmyvaka, Kashif Rasul, Frederic Sala, Anderson Schneider, Junhong Shen, and Evan R. Sparks. Automl decathlon: Diverse tasks, modern methods, and efficiency at scale. In Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021.

- Junhong Shen and Lin F. Yang. Theoretically principled deep rl acceleration via nearest neighbor function approximation. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 35(11):9558–9566, May 2021.

- Zongzhe Xu, Ritvik Gupta, Wenduo Cheng, Alexander Shen, Junhong Shen, Ameet Talwalkar, and Mikhail Khodak. Specialized foundation models struggle to beat supervised baselines, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Junhong Shen, Atishay Jain, Zedian Xiao, Ishan Amlekar, Mouad Hadji, Aaron Podolny, and Ameet Talwalkar. Scribeagent: Towards specialized web agents using production-scale workflow data, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jaideep Vaidya, Basit Shafiq, Anirban Basu, and Yuan Hong. Differentially private naive bayes classification. In 2013 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conferences on Web Intelligence (WI) and Intelligent Agent Technologies (IAT), volume 1, page 571–576, 2013.

- Alessandra Sala, Xiaohan Zhao, Christo Wilson, Haitao Zheng, and Ben Y. Zhao. Sharing graphs using differentially private graph models. In Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM conference on Internet measurement conference, IMC ’11, page 81–98, New York, NY, USA, Nov 2011. Association for Computing Machinery.

- Darakhshan, J. Mir and Rebecca N. Wright. A differentially private graph estimator. In 2009 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops, page 122–129, Dec 2009.

- Xiaoqian Jiang, Zhanglong Ji, Shuang Wang, Noman Mohammed, Samuel Cheng, and Lucila Ohno-Machado. Differential-private data publishing through component analysis. Transactions on Data Privacy, 6(1):19–34, Apr 2013.

- Zhanglong Ji and Charles Elkan. Differential privacy based on importance weighting. Machine Learning, 93(1):163–183, Oct 2013. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin I., P. Rubinstein, Peter L. Bartlett, Ling Huang, and Nina Taft. Learning in a large function space: Privacy-preserving mechanisms for svm learning, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kamalika Chaudhuri, Claire Monteleoni, and Anand D. Sarwate. Differentially private empirical risk minimization, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kamalika Chaudhuri and Claire Monteleoni. Privacy-preserving logistic regression. In D. Koller, D. Schuurmans, Y. Bengio, and L. Bottou, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 21. Curran Associates, Inc., 2008.

- Jun Zhang, Zhenjie Zhang, Xiaokui Xiao, Yin Yang, and Marianne Winslett. Functional mechanism: Regression analysis under differential privacy. CoRR, abs/1208.0219, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Jacek Czerniak and Hubert Zarzycki. Application of rough sets in the presumptive diagnosis of urinary system diseases. In Jerzy Sołdek and Leszek Drobiazgiewicz, editors, Artificial Intelligence and Security in Computing Systems, pages 41–51, Boston, MA, 2003. Springer US.

- Kobbi Nissim, Sofya Raskhodnikova, and Adam Smith. Smooth sensitivity and sampling in private data analysis. pages 75–84, 06 2007. [CrossRef]

- Junhong Shen, Abdul Hannan Faruqi, Yifan Jiang, and Nima Maftoon. Mathematical reconstruction of patient-specific vascular networks based on clinical images and global optimization. IEEE Access, 9:20648–20661, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wenduo Cheng, Junhong Shen, Mikhail Khodak, Jian Ma, and Ameet Talwalkar. L2g: Repurposing language models for genomics tasks. bioRxiv, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lingjuan Lyu, Xuanli He, and Yitong Li. Differentially private representation for NLP: formal guarantee and an empirical study on privacy and fairness. CoRR, abs/2010.01285, 2020.

- Benjamin Weggenmann and Florian Kerschbaum. Syntf: Synthetic and differentially private term frequency vectors for privacy-preserving text mining. CoRR, abs/1805.00904, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ghazaleh Beigi, Kai Shu, Ruocheng Guo, Suhang Wang, and Huan Liu. I am not what I write: Privacy preserving text representation learning. CoRR, abs/1907.03189, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Da Yu, Saurabh Naik, Arturs Backurs, Sivakanth Gopi, Huseyin A. Inan, Gautam Kamath, Janardhan Kulkarni, Yin Tat Lee, Andre Manoel, Lukas Wutschitz, Sergey Yekhanin, and Huishuai Zhang. Differentially private fine-tuning of language models. CoRR, abs/2110.06500, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter. Decoupled weight decay regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017.

- Noam M. Shazeer and Mitchell Stern. Adafactor: Adaptive learning rates with sublinear memory cost. ArXiv, abs/1804.04235, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Liam Li, Kevin Jamieson, Afshin Rostamizadeh, Ekaterina Gonina, Jonathan Ben-Tzur, Moritz Hardt, Benjamin Recht, and Ameet Talwalkar. A system for massively parallel hyperparameter tuning. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems, 2:230–246, 2020.

- Weixin Liang, Junhong Shen, Genghan Zhang, Ning Dong, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Lili Yu. Mixture-of-mamba: Enhancing multi-modal state-space models with modality-aware sparsity, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Junhong Shen, Kushal Tirumala, Michihiro Yasunaga, Ishan Misra, Luke Zettlemoyer, Lili Yu, and Chunting Zhou. Cat: Content-adaptive image tokenization, 2025. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).