1. Introduction

Employment not only serves as a cornerstone for economic subsistence but also plays a critical role in shaping individuals’ social, psychological, and community well-being [

1], [

2]. Consequently, job loss has far-reaching implications, affecting physical, psychological, and social domains [

3], [

4], [

5]. Despite continuous changes in the global economy, unemployment consistently remains above 5% worldwide, reaching nearly 7% during the 2020–2022 pandemic, according to World Bank data (2023). This rise in unemployment rates has been closely linked to significant deterioration in mental health, increasing the risk of conditions such as anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric disorders [

6], [

7], [

8].

The psychosocial impact of unemployment is well-documented. Previous studies have shown that job loss significantly increases psychological distress among affected individuals. Notably, Griffiths et al. (2021) reported that unemployed individuals with limited financial resources are at a heightened risk of experiencing severe psychological distress, with an Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) as high as 8.36 (CI: 3.35–20.87) [

9]. This finding underscores the relationship between unemployment, economic constraints, and mental well-being, highlighting the magnitude of the impact on vulnerable groups. Moreover, mental health issues not only emerge as consequences of unemployment but also act as barriers to reemployment, perpetuating a cycle of poor mental health and unemployment [

10], [

11]. Prolonged unemployment exacerbates vulnerability, with depression rates reaching 50% among individuals who have been unemployed for over 12 months [

12]. However, reemployment, even after long periods of inactivity, can lead to significant improvements in overall mental health [

13], [

14].

Despite extensive research on the impact of unemployment on mental health, the relationship between unemployment and trauma has received relatively less attention. While most trauma studies focus on adverse childhood experiences or exposures in war contexts [

15], [

16], recent findings suggest that unemployment in adulthood can also serve as a significant traumatic stressor. For instance, unemployment has been shown to double the likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [

17]. Some theoretical models propose a linear decline in mental health as the duration of unemployment increases, while others suggest adaptive processes that stabilize mental health at low levels over time [

3], [

4], [

6], [

18].

It is important to acknowledge that standard diagnostic criteria for PTSD and complex PTSD (CPTSD) traditionally require exposure to a high-intensity traumatic event—one that involves a direct threat to life or physical integrity [

19]. However, this study explores the hypothesis that chronic adverse experiences, such as prolonged unemployment, can also induce trauma-related symptoms. Emerging evidence and theoretical work suggest that sustained stress, social isolation, and economic insecurity associated with job loss may elicit psychological responses (e.g., re-experiencing, avoidance, persistent sense of threat) comparable to those seen in classic trauma exposures. This perspective is supported by empirical findings linking unemployment to heightened traumatic stress [

17] and by conceptual models that advocate for an expanded definition of trauma to encompass chronic, non–life-threatening adversities.

Unemployment can act as a catalyst for both simple and complex trauma, particularly in high-stress environments, such as post-disaster contexts [

20]. Individuals with PTSD often face challenges in maintaining employment due to debilitating symptoms, such as severe anxiety and social impairments, creating a negative feedback loop between psychological distress and joblessness [

21]. Furthermore, rapid technological advancements and the increasing integration of artificial intelligence into labor markets exacerbate these concerns. Fears of job displacement generate stress and anxiety, while excessive reliance on technology and social media can intensify feelings of isolation and worsen mental health problems [

22]. These effects are even more pronounced in contexts with high socioeconomic inequality, where limited community resilience magnifies the mental health impact of unemployment [

23], [

24].

In this context, a pertinent question arises: Can unemployment generate symptoms characteristic of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), such as emotional dysregulation, a negative self-concept, and difficulties in establishing relationships with others? Since 2018, the World Health Organization, through the ICD-11 manual, has established that a CPTSD diagnosis requires the presence of three primary symptom clusters: 1) re-experiencing the traumatic event, 2) avoidance of trauma-related memories, and 3) a persistent sense of threat. While CPTSD shares these core symptoms with PTSD, the ICD-11 defines it as a condition that also includes three additional domains specific to disturbances in self-organization (DSO): affective dysregulation, a persistently negative self-concept, and significant interpersonal difficulties. These DSO domains are exclusive to CPTSD, underscoring its clinical complexity.

Understanding this study within a psychosocial context is essential. For this reason, the choice of the GINI index and nominal GDP as moderating variables reflects the need to capture socioeconomic dimensions influencing the experience of unemployment as a stressor. The GINI index, by reflecting income distribution inequality, is associated with access to economic and social resources [

23], [

24]. In contexts with lower inequality, greater access to social support and mental health services mitigates the negative effects of unemployment. Conversely, in societies with high inequality, gaps in social safety nets tend to exacerbate psychological vulnerability and amplify the impact of unemployment [

25]. However, some studies suggest that extreme levels of inequality may lead to a "normalization" of socioeconomic imbalances, attenuating the perception of unemployment as traumatic in certain groups [

26].

Nominal GDP, in turn, provides an approximation of a country’s overall economic development and the strength of its social protection systems. A higher GDP is often associated with robust employment programs, broader healthcare coverage, and better working conditions, which may reduce the impact of unemployment on mental health [

27]. In contrast, low-GDP contexts show resource limitations and greater economic instability, intensifying the psychological burden of unemployment [

24]. Therefore, the combined analysis of the GINI index and nominal GDP allows for an evaluation of both the magnitude of national wealth and its distribution, offering a comprehensive perspective on how structural and cultural conditions modulate the relationship between unemployment and the development of PTSD/CPTSD.

Therefore, this study evaluates unemployment status as a risk factor (adverse experience) for the development of PTSD and CPTSD, while also specifically exploring the moderating roles of the GINI index (a measure of inequality) and nominal GDP. Based on the ICD-11 framework, this research analyzes how unemployment, as a sustained stressor, might influence the emergence of distinctive PTSD symptoms. By integrating broader socioeconomic factors, this work aims to contribute to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of how labor market dynamics and trauma interact within an ever-evolving global economic landscape.

2. Search Strategy

The reporting methods and procedures were carried out in accordance with the PRISMA checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; [

28], [

29]. Articles in English published in peer-reviewed journals up to November 2024 were included. The search was conducted in three scientific literature databases: Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed. The search terms used in these bibliographic databases included the following combinations: TITLE (“complex PTSD” OR “complex posttraumatic stress disorder” OR “CPTSD” OR “PTSD” OR “posttraumatic stress disorder”) AND TITLE (“risk factors” OR “predictors” OR “unemployment”) (

Table 1). Given the quantitative focus of this study, documents such as book chapters, theoretical reviews, systematic reviews, editorial comments, letters or notes, case studies, and other articles that did not provide quantitative information on risk factors for CPTSD were excluded.

Table 1.

Database search syntax.

Table 1.

Database search syntax.

| Scopus |

TITLE(“complex PTSD” OR “complex posttraumatic stress disorder” OR “CPTSD” OR “PTSD” OR “posttraumatic stress disorder”) AND TITLE(“risk factors” OR “predictors” OR “unemployment”). |

| Web of Sciences |

TI=((“complex PTSD” OR “complex posttraumatic stress disorder” OR “CPTSD” OR “PTSD” OR “posttraumatic stress disorder”) AND (“risk factors” OR “predictors” OR “unemployment”)) |

| PubMed |

((“complex PTSD”[Title] OR “complex posttraumatic stress disorder”[Title] OR “CPTSD”[Title] OR “PTSD”[Title] OR “posttraumatic stress disorder”[Title]) AND (“risk factors”[Title] OR “predictors”[Title] OR “unemployment”[Title])) |

3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies included in the meta-analysis met the following criteria. First, they examined unemployment as a possible risk factor (predictor) for the development of PTSD and/or CPTSD. Second, they reported at least one of the following data points: 1) Odds Ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), or 2) the frequency of unemployment as a risk factor in the population with PTSD and/or CPTSD and in the population without PTSD and/or CPTSD, from which a data conversion was carried out for subsequent analysis.

Studies were excluded if they addressed physical traumas (specifically musculoskeletal and/or neurological pathologies) and not PTSD and/or CPTSD; if they did not present meta-analyzable data (OR or frequencies); or if they contained insufficient data to calculate univariate effect sizes and it was not possible to obtain such information from the study’s author. Likewise, any studies that did not include unemployment as a risk factor or examined unemployment experienced by someone other than the study sample (e.g., a relative) were excluded, as were reviews or qualitative studies that did not present new data or only included qualitative analyses. Further exclusions involved single-case designs. Finally, if more than one article presented data from the same sample, the most recent and comprehensive article was included in the meta-analysis.

4. Quality Assessment

The quality assessment process was carried out using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (National Institute of Health, 2021). This tool comprises 14 items that evaluate aspects such as the formulation of the research question, the composition of the population, recruitment procedures, sample size, methods for measuring exposures and outcomes, attrition rates, and the statistical methods used. Each item is rated as “yes,” “no,” or partial (“cannot determine,” “not applicable,” or “not reported”). Following the recommendations of Katy Gaythorpe and colleagues [

30], a score of 1.0 was assigned to “yes” responses, 0.5 to partial responses, and 0 to “no” responses. Based on the total score, studies were classified as high quality when they scored 7.0 points or higher, moderate quality when they scored between 5.0 and 6.0 points, and low quality when they scored below 5.0 points (Supplementary

Table 1).

5. Data Extraction

The initial search was performed by one of the authors, who identified articles based on the established search terms. A subsequent manual review was carried out to select articles that met the inclusion criteria. This review was conducted independently by three authors, who examined the titles, abstracts, or, when necessary, the full text of relevant articles. Discrepancies in interpretation were resolved through discussion with an additional reviewer, reaching a final consensus for selection and coding.

The selected articles were thoroughly reviewed in accordance with the inclusion criteria. For classification purposes, a color-coding system was used based on Cochrane’s recommendations [

31]: included articles were marked in green, excluding articles in red, those with uncertainties in yellow, and those not found in orange. Several tools were used for data extraction and management, including Microsoft Excel 2021 to organize and compile data, Mendeley Reference Manager (version 2.88) to manage the articles (selection, eligibility, and inclusion; [

32], and Review Manager (RevMan) (version 5.4.1) for analysis and reporting of results.

From each eligible study, the following data were extracted: the first author’s last name, year of publication, study location, sample size, percentage of female participation, participant ages and standard deviations, prevalence of CPTSD, number of individuals exposed to potentially traumatic factors, estimated effect size (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), adjusted covariates in the statistical analysis, and the frequency of exposure to the risk factor. Additionally, the variance of the logarithm of each effect size was calculated for the analysis.

6. Statistical Analysis

Odds ratios (OR) were used as the primary measure of effect size in this analysis. OR values were extracted directly from the studies whenever they were reported. In cases where OR values were not provided, they were calculated from the reported exposure frequencies. Additionally, other effect size measures, such as correlations between risk factors and PTSD and/or CPTSD, as well as mean differences between exposed and unexposed groups, were converted to ORs to ensure methodological consistency. The variance of the natural logarithm of the OR (logOR) was calculated using rESCMA, an open-access web-based calculator for effect size conversions (rescma.com) [

33].

A random-effects model was adopted as the analytical framework, under the assumption that true effect sizes vary among the included studies [

34]. To stabilize variances and ensure uniform distributions, OR values were transformed into natural logarithms (logOR), and their variances (VarLogOR) were calculated prior to analysis. The results were then back-transformed to OR values to facilitate interpretation [

34], [

35]. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s regression test. Symmetry in the funnel plots indicates the absence of bias, whereas asymmetry suggests the possibility of publication bias. The analyses were conducted in RStudio version 2023.06.0 and R version 4.3.1, using the metafor package [

36].

To explore the impact of socioeconomic variables on the relationship between unemployment and the development of PTSD and/or CPTSD, a meta-regression analysis was performed using mixed-effects models, which consider both within-study and between-study variability. The selected variables included nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as an indicator of inflation-adjusted economic growth and the Gini coefficient (GINI) as a measure of income inequality [

37], with data extracted from the World Bank databases [

38]. The significance of the moderators was evaluated using β values (p < .05), classified as low (<24%), moderate (25–64%), or high (>65%) [

39]. This analysis provided deeper insight into how these moderating factors influence the overall effect estimates.

In both the meta-analyses and meta-regressions, Cochran’s Q test and the I² index were used to evaluate heterogeneity. A significant p-value in the Q statistic indicates heterogeneity among studies, while the I² index quantifies the percentage of variation attributable to this heterogeneity. I² values were interpreted according to established thresholds: low (<40%), moderate (40–60%), and substantial (>60%) [

40]. The results of the meta-analyses were presented through forest plots, which visually compare individual effect sizes and the combined effect. Additionally, publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s test (p < .05). This systematic approach ensures that the conclusions drawn are robust and reliable in the face of potential biases or external influences.

7. Results

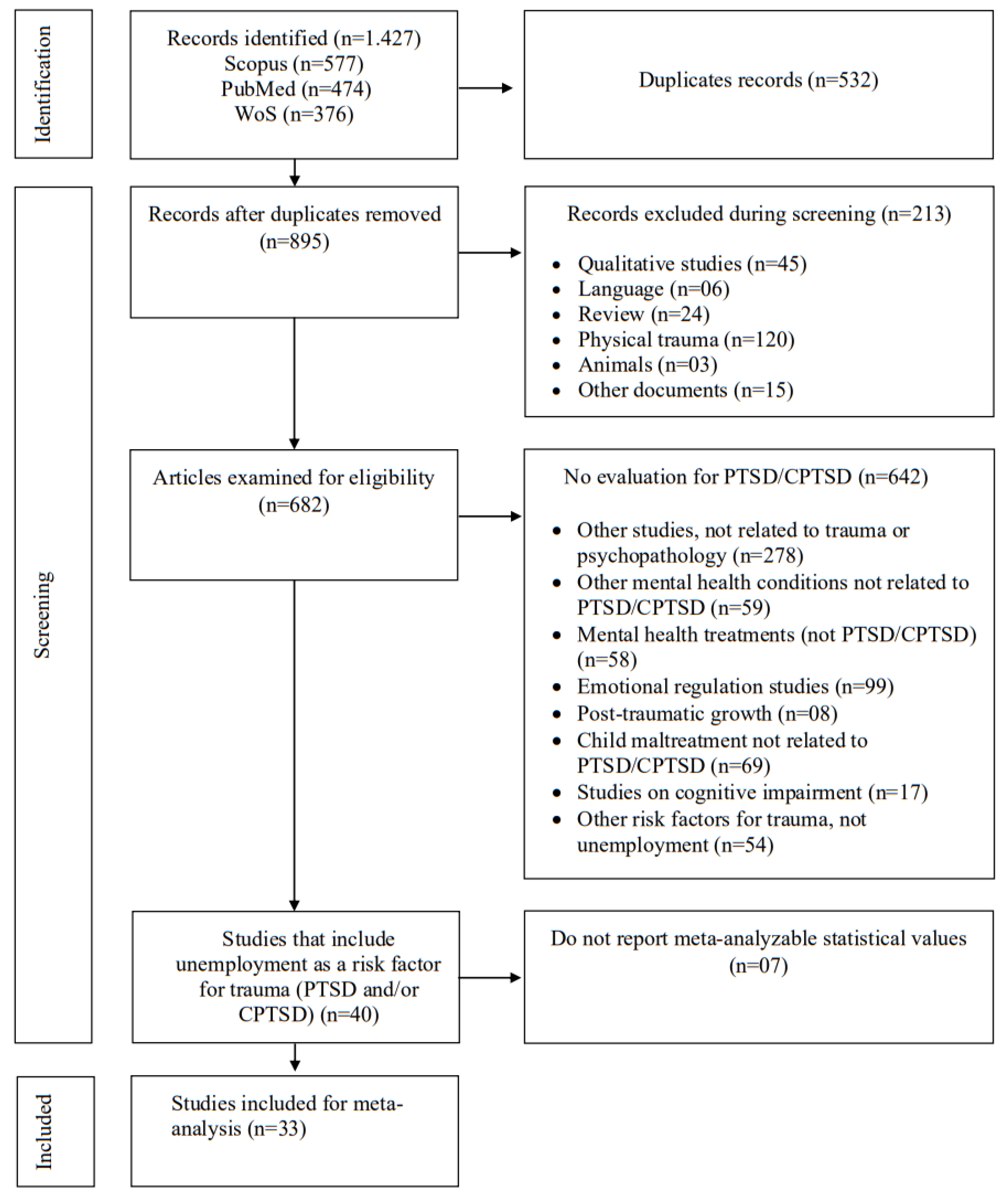

A total of 1,427 records were identified in the Web of Science, SCOPUS, and PubMed databases. Of these, 34 studies were included (

Figure 1), representing 59,844 individuals from 21 countries and various populations, including general, clinical, and trauma-exposed groups (

Table 2). Regarding study quality, the average score was 6.83, indicating an overall assessment of study quality as fair (

Table 3; Supplementary

Table 1 and

Table 2).

8. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies varied.

Table 2 provides a summary of the 14 quality assessment areas and the general rating for each study, indicating the potential risk of bias. According to the guidelines provided by the National Institutes of Health tool (2021), out of the 34 studies analyzed, 21 studies were rated as “good” quality, suggesting a low risk of bias, while 13 studies received a “moderate” quality rating, indicating a moderate risk of bias.

In this research, a significant number of the included studies are cross-sectional in design. It is important to note that cross-sectional designs have inherent limitations in assessing changes over time, as they capture information at a single point in time. This explains the minimal scores on questions pertaining to characteristics typical of longitudinal studies: sufficient time to observe associations (Item Q7), whether exposures were evaluated more than once over time (Item Q10), and assessment of participant loss during follow-up (Item Q13).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies with unemployment as a risk factor for PTSD and CPTSD.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies with unemployment as a risk factor for PTSD and CPTSD.

| ID |

Authors |

Desing |

Sample type |

N |

% female |

Age (M±SD) |

N

Unemp |

Identification of PTSD/CPTSD |

| 01 |

Ali et al (2012) [41] |

Cross-sectional |

Survivors |

300 |

39.3% |

37.8±14.0 |

234 |

Davidson Trauma Scale |

| 02 |

Astill et al (2021) [42] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

222 |

- |

16 |

137 |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 03 |

Ayazi et al (2012) [43] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

1200 |

44% |

- |

111 |

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) |

| 04 |

Baek et al (2022) [44] |

Cross-sectional |

Defectors |

503 |

84.5% |

46±13.2 |

- |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 05 |

Bronner et al (2010) [45] |

Longuitudinal |

Clinical |

588 |

56.8% |

36.5±7.0 |

150 |

Self-Rating Scale for PTSD (SRS-PTSD) |

| 06 |

Cenat et al (2014) [46] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

1355 |

48.7% |

31.57 |

221 |

Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R) |

| 07 |

Cerdá et al (2013) [47] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

1315 |

71.1% |

- |

- |

Lifetime Violent Traumatic Event Experience |

| 08 |

Cheng et al (2015) [48] |

Cross-sectional |

Survivors |

182 |

65.2% |

- |

88 |

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders |

| 09 |

Choi et al (2021) [49] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

800 |

- |

- |

- |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 10 |

Cohen et al (2009) [50] |

Cross-sectional |

Clinical |

850 |

100% |

36.4±8.3 |

637 |

Harvard Trauma Questionnairem (HTQ) |

| 11 |

Cofini er al (2015) [51] |

Cross-sectional |

Survivors |

281 |

54% |

43 |

103 |

Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) |

| 12 |

Eşsizoglu et al (2017) [52] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

93 |

34.4% |

28.28±9.8 |

63 |

Traumatic Stress Symptom Scale (TSSC) |

| 13 |

Facer-Irwin et al (2022) [53] |

Cross-sectional |

Imprisoned |

221 |

0% |

31.3±9.0 |

116 |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 14 |

Frost et al (2019) [16] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

1051 |

68.4% |

47.18 |

- |

Life Events Checklist (LEC). |

| 15 |

Gros et al (2013) [54] |

Cross-sectional |

Veterans |

92 |

6.5% |

33.2±9.0 |

48 |

Clinician Administered PTSD Scale |

| 16 |

Hyland et al (2017) [55] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

2591 |

54.6% |

24 |

- |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 17 |

Hyland et al (2018) [56] |

Cross-sectional |

Refugees |

110 |

51% |

- |

- |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 18 |

Hyland et al (2021) [57] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

1020 |

51% |

43.1±15.1 |

- |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 19 |

Karatzais et al (2019) [58] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

1051 |

68.4% |

47.18±15 |

- |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 20 |

Kimerling et al (2009) [59] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

6698 |

100% |

- |

- |

Harvard Trauma Questionnaire (HTQ) |

| 21 |

Kvedaraite et al (2022) [60] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

885 |

63.4% |

37.96±14.67 |

205 |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

Table 2.

(continued).

| ID |

Authors |

Desing |

Sample type |

N |

% female |

Age (M±SD) |

N

Unemp |

Identification of PTSD/CPTSD |

| 22 |

Lee et al (2009) [61] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

196 |

- |

- |

- |

Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry |

| 23 |

Mills et al (2016) [62] |

Longitudinal |

Clinical |

103 |

60% |

33.4±7.40 |

79 |

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale |

| 24 |

Murphy et al (2016) [63] |

Cross-sectional |

Veterans |

177 |

4.90% |

- |

127 |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 25 |

Nandi et al (2004) [64] |

Longitudinal |

General |

1939 |

54.3% |

- |

- |

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders |

| 26 |

Pazderka et al (2022) [65] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

159 |

100% |

- |

- |

Lifetime Violent Traumatic Event Experience |

| 27 |

Powers et al (2014) [66] |

Longitudinal |

Clinical |

327 |

36% |

46±18.00 |

141 |

Primary Care Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Screen |

| 28 |

Rybojad et al (2016) [67] |

Cross-sectional |

Paramedics |

100 |

14% |

33.6±9.30 |

- |

Impact of Event Scale - Revised (IES-R) |

| 29 |

Serrano et al (2021) [21] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

26213 |

68.7% |

49.5±17.0 |

- |

Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) |

| 30 |

Simon et al (2019) [68] |

Cross-sectional |

Clinical |

246 |

50% |

47.37±12 |

235 |

International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) |

| 31 |

Stuber et al (2010) [69] |

Cross-sectional |

Childhood |

6542 |

52.3% |

31.85±7.5 |

1439 |

Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale |

| 32 |

Teramoto et al (2015) [70] |

Cross-sectional |

General |

296 |

57.1% |

57.10 |

- |

Kessler Psychological Distress Scale |

| 33 |

Weiss et al (2011) [71] |

Cross-sectional |

Clinical |

245 |

69.6% |

43.7±10.9 |

- |

Clinician Administered PTSD Scale |

Table 3.

Statistics used for each included study, for meta-analysis and meta-regression.

Table 3.

Statistics used for each included study, for meta-analysis and meta-regression.

| ID |

Autor |

PTSD |

CPTSD |

Country |

GINI |

NPIB |

Quality score |

| OR |

Log |

VarLog |

OR |

Log |

VarLog |

| 01 |

Ali et al (2012) |

3.72 |

1.31370 |

0.0497 |

- |

|

- |

Pakistan |

29.6 |

1588 |

6.0 |

| 02 |

Astill et al (2021) |

1.58 |

0.45742 |

0.1555 |

2.22 |

0.79750 |

0.06235 |

United Kingdom |

32.6 |

46125 |

6.0 |

| 03 |

Ayazi et al (2012) |

4.25 |

1.44690 |

0.0127 |

- |

- |

- |

South Sudan |

44.1 |

1071 |

7.0 |

| 04 |

Baek et al (2022) |

1.30 |

0.26236 |

0.0263 |

2.90 |

1.06471 |

0.02847 |

South Korea |

31.4 |

32422 |

6.0 |

| 05 |

Bronner et al (2010) |

2.56 |

0.94001 |

0.0951 |

- |

- |

- |

Netherlands |

26.0 |

57025 |

10 |

| 06 |

Cenat et al (2014) |

0.84 |

-0.17435 |

0.0007 |

- |

- |

- |

Haiti |

41.1 |

1742 |

6.0 |

| 07 |

Cerdá et al (2013) |

1.44 |

0.36464 |

0.0100 |

- |

- |

- |

Haiti |

41.1 |

1742 |

7.0 |

| 08 |

Cheng et al (2015) |

0.55 |

-0.59784 |

0.0746 |

- |

- |

- |

China |

37.1 |

12720 |

7.0 |

| 09 |

Choi et al (2021) |

- |

- |

- |

6.17 |

1.81969 |

0.02061 |

South Korea |

31.4 |

32422 |

5.0 |

| 10 |

Cohen et al (2009) |

1.00 |

0.00000 |

0.0154 |

- |

- |

- |

Rwanda |

43.7 |

966 |

7.0 |

| 11 |

Cofini et al (2015) |

2.10 |

0.74194 |

0.0489 |

- |

- |

- |

Italy |

35.2 |

34776 |

8.0 |

| 12 |

Eşsizoglu et al (2017) |

1.47 |

0.38526 |

0.3908 |

- |

- |

- |

Turkey |

41.9 |

10674 |

7.0 |

| 13 |

Facer-Irwin et al (2022) |

1.90 |

0.64185 |

0.0309 |

2.00 |

0.69314 |

0.05981 |

United Kingdom |

32.6 |

46125 |

7.0 |

| 14 |

Frost et al (2019) |

1.48 |

0.39204 |

0.1264 |

0.88 |

-0.12783 |

0.01258 |

United Kingdom |

32.6 |

46125 |

5.0 |

| 15 |

Gros et al (2013) |

1.87 |

0.62594 |

0.1489 |

- |

- |

- |

United States |

39.8 |

76329 |

9.0 |

| 16 |

Hyland et al (2017) |

1.66 |

0.50682 |

0.0045 |

6.99 |

1.94448 |

0.00654 |

Denmark |

27.5 |

67790 |

7.5 |

| 17 |

Hyland et al (2018) |

4.96 |

1.60141 |

0.1442 |

4.27 |

1.46161 |

0.13962 |

Lebanon |

31.8 |

4136 |

6.5 |

| 18 |

Hyland et al (2020) |

1.20 |

0.18232 |

0.0110 |

2.21 |

0.79299 |

0.01353 |

Ireland |

31.8 |

103983 |

6.5 |

| 19 |

Karatzais et al (2018) |

0.98 |

-0.02020 |

0.0120 |

1.37 |

0.31481 |

0.01259 |

United Kingdom |

32.6 |

46125 |

8.0 |

| 20 |

Kimerling et al (2009) |

1.60 |

0.47000 |

0.0019 |

- |

- |

- |

United States |

39.8 |

76329 |

5.0 |

| 21 |

Kvedaraite et al (2020) |

0.89 |

-0.11653 |

0.1226 |

1.99 |

0.68813 |

0.01542 |

Lithuanian |

36 |

25064 |

7.0 |

Table 3.

(continued).

| ID |

Autor |

PTSD |

CPTSD |

Country |

GINI |

NPIB |

Quality score |

| OR |

Log |

VarLog |

OR |

Log |

VarLog |

| 22 |

Lee et al (2009) |

1.60 |

0.47000 |

0.0051 |

- |

- |

- |

Taiwan |

34.2 |

35513 |

7.0 |

| 23 |

Mills et al (2016) |

1.74 |

0.55389 |

0.1320 |

- |

- |

- |

Australia |

34.3 |

52084 |

7.0 |

| 24 |

Murphy et al (2021) |

0.25 |

-1.38629 |

0.0085 |

0.50 |

-0.69314 |

0.07749 |

United Kingdom |

32.6 |

46125 |

7.5 |

| 25 |

Nandi et al (2004) |

1.00 |

0.00000 |

0.0067 |

- |

- |

- |

United States |

39.8 |

76329 |

9.0 |

| 26 |

Pazderka et al (2022) |

5.18 |

1.64481 |

0.1004 |

- |

- |

- |

Canada |

31.7 |

54917 |

6.0 |

| 27 |

Powers et al (2014) |

1.03 |

0.02956 |

0.0403 |

- |

- |

- |

United States |

39.8 |

76329 |

7.0 |

| 28 |

Rybojad et al (2016) |

3.27 |

1.18479 |

0.2235 |

- |

- |

- |

Poland |

28.8 |

18688 |

7.0 |

| 29 |

Serrano et al (2021) |

1.18 |

0.16551 |

0.0005 |

- |

- |

- |

Chile |

44.9 |

15355 |

7.0 |

| 30 |

Simon et al (2019) |

- |

- |

- |

1.75 |

0.55961 |

0.05499 |

United Kingdom |

32.6 |

46125 |

8,0 |

| 31 |

Stuber et al (2010) |

2.01 |

0.69813 |

0.0232 |

- |

- |

- |

United States |

39.8 |

76329 |

6.0 |

| 32 |

Teramoto et al (2015) |

1.23 |

0.20701 |

0.0061 |

- |

- |

- |

Japan |

32.9 |

33950 |

6.5 |

| 33 |

Weiss et al (2011) |

1.57 |

0.45108 |

0.0547 |

- |

- |

- |

United States |

39.8 |

76329 |

5.0 |

9. Meta-Analysis

Among the 34 studies included in this meta-analysis, unemployment was evaluated as a risk factor for the development of PTSD and CPTSD, integrating both combined odds ratio (OR) estimates and the exploration of socioeconomic moderator variables (e.g., nominal GDP and the GINI coefficient). Below, the main findings of each meta-analysis are presented, highlighting their heterogeneity, potential publication bias, and the robustness of the associations.

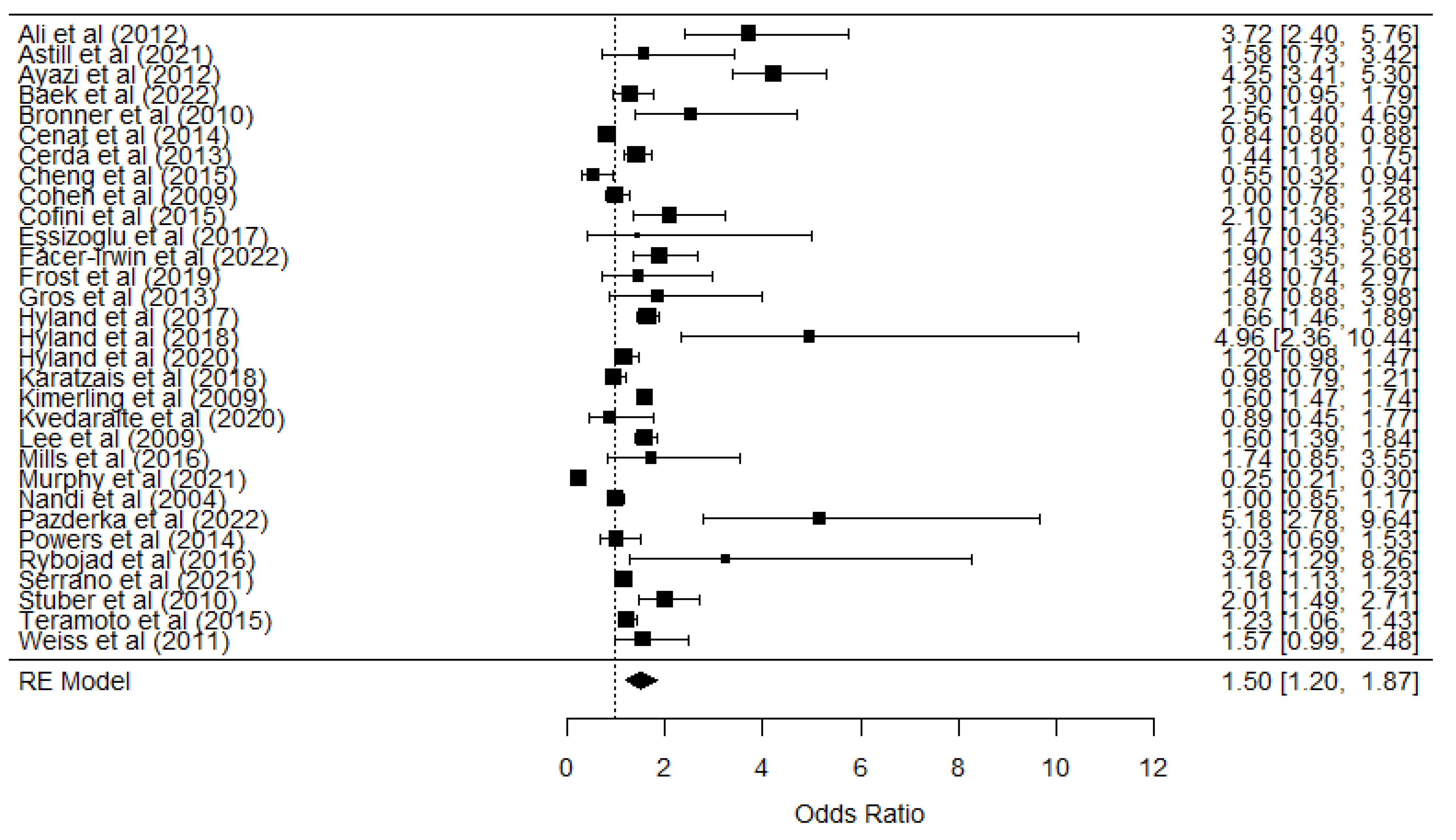

For PTSD, 32 studies were analyzed, encompassing a total of n = 58,400 participants. This combined sample offers a broad perspective across various contexts (general populations, clinical settings, and trauma-exposed groups) and types of research designs (cross-sectional and longitudinal). The odds ratio (OR) obtained was 1.47 (logOR = 0.3826, p < 0.000; 95% CI: 0.165 - 0.600), suggesting that unemployment is associated with an approximately 47% increase in the likelihood of developing PTSD.

However, the prediction interval (0.457 - 4.702) revealed considerable variation among the studies, indicating that the effect may fluctuate according to factors such as duration of unemployment, resilience of social support networks, and specific sociocultural environments. Moreover, substantial heterogeneity was observed (Q = 804.155, p < 0.000; I² = 98.02), reflecting notable differences in study designs and populations. This dispersion could be explained by variability in diagnostic criteria, sample sizes, or the combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Finally, Egger’s test (Z = 2.0813, p = 0.037) indicated a potential publication bias, necessitating caution when interpreting the robustness of this finding.

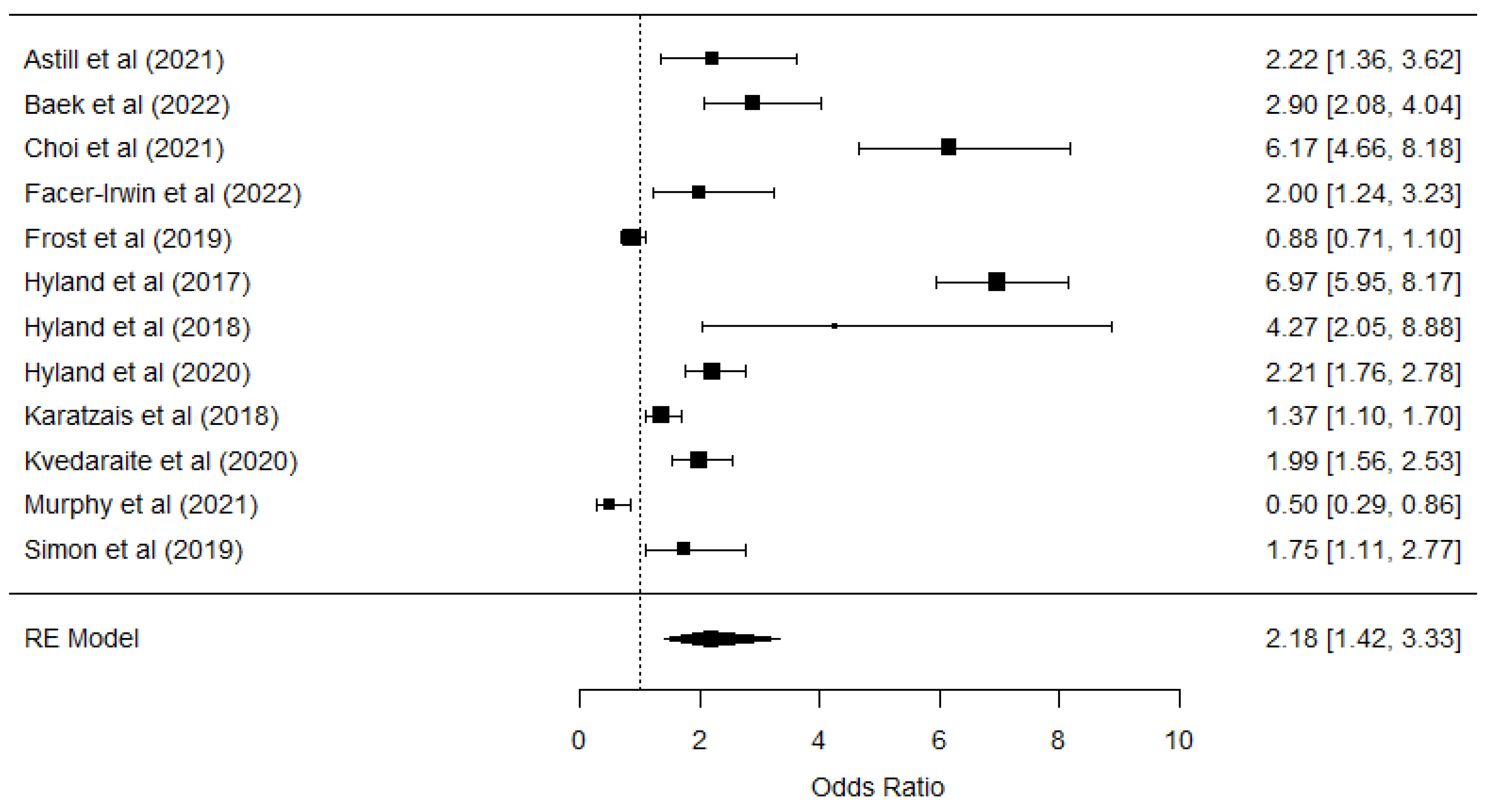

For CPTSD, 13 studies were included (n = 10,770), focusing on diverse populations (refugees, general communities, and clinical groups). A combined OR of 2.101 was found (logOR = 0.743, p < 0.000; 95% CI: 0.346 - 1.138), indicating that unemployment may double the likelihood of developing CPTSD. The prediction interval (0.501 - 8.808) was even broader than for PTSD, underscoring the influence of specific contextual factors and the high variability in the manifestation of complex symptoms.

The heterogeneity analysis showed very high levels (Q = 405.014, p = 0.000; I² = 96.42), suggesting significant differences among the studies in terms of methodology, characteristics of the populations, and possible clinical cofactors (e.g., previous traumas or concurrent mental health conditions). Similarly, Egger’s test (Z = -0.2670, p = 0.789) did not detect publication bias.

The meta-analyses on PTSD and CPTSD reinforce the significant association between unemployment and the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorders, including their more complex form. Despite recognizing high heterogeneity and the presence of publication bias, the overall estimates (OR of 1.470 and 2.101, respectively) demonstrate that unemployment acts as a stressor with the potential to exacerbate traumatic symptoms.

Table 4.

Results of the meta-analysis of unemployment as a risk factor for PTSD & CPTSD.

Table 4.

Results of the meta-analysis of unemployment as a risk factor for PTSD & CPTSD.

| |

REM |

Heterogeneity tests |

Publication bias |

| k |

n |

logOR |

OR |

p |

PIlower

|

PIupper

|

IClower

|

ICupper

|

Q |

p |

I2

|

ZEgger |

p |

| PTSD |

31 |

56507 |

0.402 |

1.493 |

.000 |

0.464 |

4.821 |

1.198 |

1.868 |

791.936 |

.001 |

98.02% |

1.6516 |

0.1094 |

| CPTSD |

12 |

8877 |

0.778 |

2.177 |

.000 |

0.495 |

9.593 |

1.423 |

3.330 |

359.423 |

.001 |

96.14% |

-1.0071 |

0.3376 |

Table 5 presents the results of the meta-regression aimed at assessing the impact of two economic variables. The Gini index and nominal gross domestic product (nominal GDP, NGDP) on the relationship between unemployment and the onset of PTSD and CPTSD. The interpretation of each moderation model is described below, considering the estimator values, their confidence intervals, and statistical significance levels.

Table 5.

Meta-regression for unemployment, PTSD and CPTSD.

Table 5.

Meta-regression for unemployment, PTSD and CPTSD.

| |

|

Heterogeneity tests |

| k |

Mod |

Estimate |

SE |

p |

IClower

|

ICupper

|

Q |

p |

I2

|

| PTSD |

31 |

GINI |

-0.0218 |

0.0225 |

0.3338 |

-0.0659 |

0.0224 |

787.3114 |

0.001 |

97.77% |

| NGDP |

-0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.6253 |

-0.0000 |

0.0000 |

717.5710 |

0.001 |

97.84% |

| CPTSD |

12 |

GINI |

-0.2125 |

0.1014 |

0.0362 |

-0.4113 |

-0.0136 |

167.8064 |

0.001 |

94.06% |

| NGDP |

-0.0000 |

0.0000 |

0.8294 |

-0.0000 |

0.0000 |

345.4163 |

0.001 |

96.32% |

First, the estimated value for the Gini index (Estimate = −0.0242, SE = 0.0221, p = 0.2733, CI: −0.0659 to 0.0224) did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that economic inequality, as measured by the Gini index, does not conclusively alter the impact of unemployment on the development of PTSD across the studies analyzed.

On the other hand, nominal GDP (NGDP) also did not exhibit a significant moderating effect (Estimate = −0.0000, SE = 0.0000, p = 0.4926, CI: −0.0000 to 0.0000). In both cases, the heterogeneity tests (Q = 799.9109, p < .001, I² = 97.76% for Gini; Q = 750.4517, p < .001, I² = 97.83% for NGDP) reveal substantial variability among the studies. This very high level of heterogeneity suggests the presence of methodological, clinical, or contextual factors not captured by the meta-regression models.

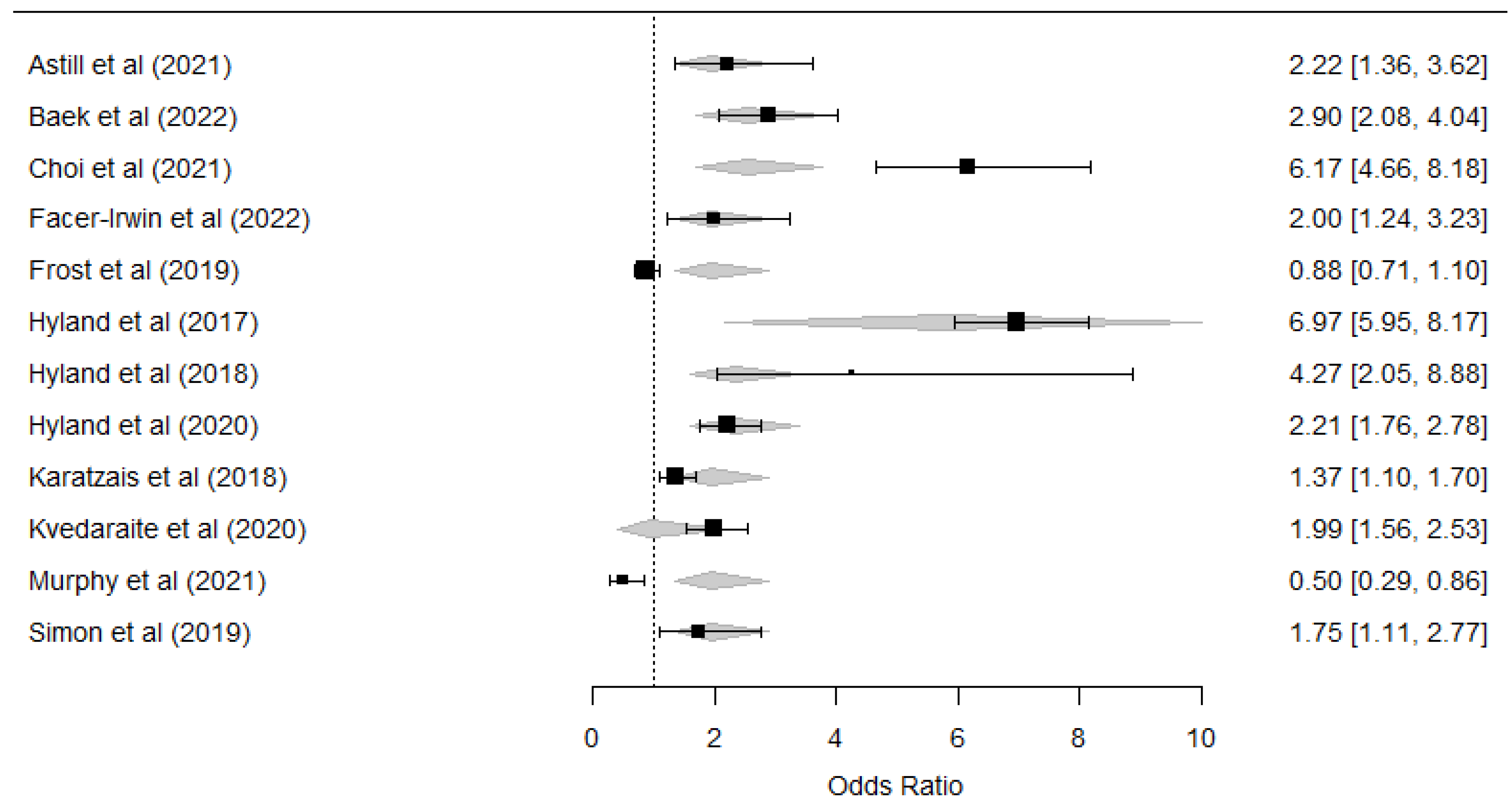

Regarding the Gini index, the estimation (Estimate = −0.2125, SE = 0.1014, p = 0.0649, CI: −0.4113 to −0.0136) produced a p-value above the conventional threshold of p < .05 and thus is not considered statistically significant. Although the confidence interval mostly lies below zero, which could imply a tendency toward a negative moderating effect, the p-value does not confirm this moderation conclusively.

As for nominal GDP (Estimate = −0.0000, SE = 0.0000, p = 0.682, CI: −0.0000 to 0.0000), no statistically significant moderating effect was observed on the unemployment–CPTSD relationship. Similar to the findings for PTSD, heterogeneity was again very high (Q = 223.8095, p < .001, I² = 94.94% for Gini; Q = 404.1999, p < .001, I² = 96.58% for NGDP). Overall, the results show that neither of the two moderators (Gini nor NGDP) reached statistical significance (p < .05) in modifying the association between unemployment and the onset of PTSD or CPTSD.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the unemployment and PTSD relationship.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the unemployment and PTSD relationship.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the unemployment and CPTSD relationship.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the unemployment and CPTSD relationship.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the GINI’s moderation on unemployment and CPTSD relationship.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the GINI’s moderation on unemployment and CPTSD relationship.

10. Discussion

This meta-analysis had two main objectives: 1) to quantify the association between unemployment and the risk of developing both PTSD and CPTSD, and 2) to evaluate whether economic inequality (measured by the Gini index) and nominal GDP act as possible moderators of this relationship. By including 32 studies with 58,400 participants for PTSD and 13 studies with 10,770 participants for CPTSD, a solid foundation was established for examining these objectives.

Regarding the first objective, the findings indicate that unemployed individuals face a significantly higher risk of developing PTSD—approximately 47% higher—compared to those who are employed. Similarly, the likelihood of presenting CPTSD doubles among unemployed individuals relative to their employed counterparts. This increase in the risk of CPTSD underscores the potential magnitude of the psychosocial impact of unemployment, likely tied to the loss of structure, purpose, and support networks often accompanying joblessness. Our results, consistent with previous analyses [

20], strengthen the notion that prolonged unemployment can serve as a precipitating factor for chronic trauma.

Scientific literature on CPTSD has documented clear differences from PTSD, particularly in the realms of emotional and behavioral disturbances, negative self-perception, and significant interpersonal difficulties [

56], [

72], [

73]. Our results suggest that these disturbances may be aggravated in unemployed individuals, supporting the hypothesis of a closer link between unemployment and CPTSD than between unemployment and PTSD. In this vein, chronic lack of employment emerges as a source of trauma that can be not just acute but also ongoing, influencing self-esteem, social relationships, and psychological resources [

10], [

12], [

14]. These findings underscore the importance of distinguishing between PTSD and CPTSD, as each involves unique psychological and psychosocial processes.

The psychosocial impact of trauma model applied to unemployment [

74], [

75] provides additional insight: beliefs about oneself, work, personal merit, and social justice affect the psychological response to job loss. While some individuals develop resilience, seeking new employment, strengthening social networks, or engaging in activities that restore their sense of efficacy—others may experience PTSD or CPTSD symptoms, even when protective factors such as government or family support are present. These individual differences explain why, in seemingly similar contexts (e.g., countries with robust welfare policies vs. those with weaker systems), divergent responses are observed.

Another point of interest lies in the relationship between unemployment, social stigmatization, and self-esteem [

76]. The stigma associated with being unemployed may intensify among those who have recently lost their jobs or who have been unable to find work for an extended period, negatively affecting perceptions of self-worth [

77] At the same time, the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution brings new challenges for mental health and employment, such as techno-anxiety and techno-stress, heightening the perception of vulnerability in the face of automation and artificial intelligence [

78].

With respect to the second objective, the study explored whether the Gini index and nominal GDP moderate the association between unemployment and the development of PTSD/CPTSD. Although previous literature has suggested that economic inequality may influence various mental health conditions [

25], [

26], our analyses did not yield statistically significant results for either of these indicators. In other words, neither income inequality (Gini) nor nominal GDP showed a conclusive moderating effect on the unemployment–PTSD or unemployment–CPTSD relationship. These findings partially contrast with certain theoretical studies suggesting that, in contexts of high inequity, a “normalization” of precarious employment may exist, reducing the guilt or shame associated with job loss (Lerner, 1980; Marmot, 2005). However, the p-values from our meta-regressions do not support a statistically robust moderation. This does not rule out, from a conceptual standpoint, the relevance of exploring how unemployment is perceived in environments with greater or lesser socioeconomic gaps. In societies with high levels of inequality, chronic exposure to shortages and lower expectations for job mobility could theoretically alter the way unemployment is experienced (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2015). Moreover, the absence of formal protection could be offset by informal community or family support networks [

79], partially mitigating the psychological impact of joblessness [

23].

From an applied perspective, the conclusions of this meta-analysis have implications for public policies and health interventions. Recognizing unemployment as a risk factor for post-traumatic stress disorders, particularly in their complex form, could guide prevention strategies and care that focus on vulnerable groups. Additionally, it is essential to encourage lines of research examining the interaction of cultural, cognitive, and social variables—beyond purely economic ones—that may influence the subjective experience of unemployment.

Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. The high clinical and statistical heterogeneity indicates that the results should be interpreted cautiously, and the lack of longitudinal studies makes it difficult to establish clear causal relationships. Furthermore, factors such as gender, age, family situation, the specific duration of unemployment, or the type of employment are not always reported in a standardized manner in the literature, preventing more detailed analysis. Lastly, publication bias and wide confidence intervals highlight the need to increase the number of studies with large, representative samples following rigorous protocols.

Overall, the findings of this meta-analysis underscore the urgency of considering unemployment as a trauma trigger capable of severely affecting mental health. Although no significant moderating effect of the Gini index or nominal GDP was observed, understanding the psychosocial foundations of unemployment and its relationship to the development of PTSD and CPTSD offers a starting point for designing prevention strategies more attuned to the realities of unemployed individuals. Ultimately, the confluence of labor, social, economic, and cultural factors emphasize the complexity of the relationship between unemployment and trauma, and points to the need for further research exploring the nuances of this interaction.

References

- Arena, A.F.; et al. Mental health and unemployment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to improve depression and anxiety outcomes. Elsevier B.V. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.I.; Batinic, B. The need for work: Jahoda’s latent functions of employment in a representative sample of the German population. J Organ Behav 2010, 31, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelink, V.H.M.; Ya, K.Z.; Guldbrandsson, K.; Bremberg, S. Unemployment among young people and mental health: A systematic review. SAGE Publications Ltd. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jebb, A.T.; Morrison, M.; Tay, L.; Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being Around the World: Trends and Predictors Across the Life Span. Psychol Sci 2020, 31, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, G.E.; Eum, M.J.; Huh, Y.; Jung, J.H.; Choi, M.J. The Association Between Employment Status and Mental Health in Young Adults: A Nationwide Population-Based Study in Korea. J Affect Disord 2021, 295, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammer, A.; Packham, A. Effects of unemployment insurance duration on mental and physical health. J Public Econ 2023, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drydakis, N. The effect of unemployment on self-reported health and mental health in Greece from 2008 to 2013: A longitudinal study before and during the financial crisis. Soc Sci Med 2015, 128, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedikli, C.; Miraglia, M.; Connolly, S.; Bryan, M.; Watson, D. The relationship between unemployment and wellbeing: an updated meta-analysis of longitudinal evidence. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 2023, 32, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.A. The Griffith Empathy Measure Does Not Validly Distinguish between Cognitive and Affective Empathy in Children. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Olesen, S.C.; Butterworth, P.; Leach, L.S.; Kelaher, M.; Pirkis, J. Mental health affects future employment as job loss affects mental health: Findings from a longitudinal population study. BMC Psychiatry 2013, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolove, C.A.; Galatzer-Levy, I.R.; Bonanno, G.A. Emergence of depression following job loss prospectively predicts lower rates of reemployment. Psychiatry Res 2017, 253, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmela, K.; Mattila, A.; Heikkinen, V.; Uitti, J.; Ylinen, A.; Virtanen, P. Identification of depression and screening for work disabilities among long-term unemployed people. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee-Ryan, F.M.; Song, Z.; Wanberg, C.R.; Kinicki, A.J. “Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology 2005, 90, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steed, L.B.; Swider, B.W.; Keem, S.; Liu, J.T. “Leaving Work at Work: A Meta-Analysis on Employee Recovery From Work. J Manage 2021, 47, 867–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorahy, M.J.; et al. Complex PTSD, interpersonal trauma and relational consequences: Findings from a treatment-receiving Northern Irish sample. J Affect Disord 2009, 112, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, R.; Vang, M.L.; Karatzias, T.; Hyland, P.; Shevlin, M. “The distribution of psychosis, ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD symptoms among a trauma-exposed UK general population sample. Psychosis 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruya, B.; Tang, Y.Y. Is attention really effort? Revisiting Daniel Kahneman’s influential 1973 book attention and effort. Front Psychol 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, A.; Osgood, N.D.; Occhipinti, J.-A.; Ju, Y.; Song, C.; Hickie, I.B. E P I D E M I O LO G Y Unemployment and underemployment are causes of suicide. 2023. Available online: https://www.science.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. 2018.

- Leiva-Bianchi, M.; Nvo-Fernandez, M.; Villacura-Herrera, C.; Miño-Reyes, V.; Varela, N.P. What are the predictive variables that increase the risk of developing a complex trauma? A meta-analysis. Elsevier B.V. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.; Leiva-Bianchi, M.; Ahumada, F.; Araque-Pinilla, F. What Is The Association Between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder And Unemployment After A Disaster? Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2021, 34, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.T.P. Existential positive psychology and integrative meaning therapy. International Review of Psychiatry 2020, 32, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgard, S.A.; Kalousova, L. Effects of the Great Recession: Health and Well-Being. Annu Rev Sociol 2015, 41, 181–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Burns, J.K.; Dhingra, M.; Tarver, L.; Kohrt, B.A.; Lund, C. Income inequality and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. 2018.

- Barbalat, G.; Franck, N. Ecological study of the association between mental illness with human development, income inequalities and unemployment across OECD countries. BMJ Open 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L.; Wibbels, E.; Wilkinson, R. Economic inequality is related to cross-national prevalence of psychotic symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015, 50, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riumallo-Herl, C.; Basu, S.; Stuckler, D.; Courtin, E.; Avendano, M. Job loss, wealth and depression during the Great Recession in the USA and Europe. Int J Epidemiol 2014, 43, 1508–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaythorpe, K.A.M.; et al. Children’s role in the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of early surveillance data on susceptibility, severity, and transmissibility. Sci Rep 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. Manual Cochrane de Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones, versión 5.1. 0. Manual Cochrane de Revisiones Sistemáticas de Intervenciones, versión 5.1.0, 2012, 1–639.

- Thelwall, M. Early Mendeley readers correlate with later citation counts. Springer Netherlands. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Villacura-Herr, C.; Kenner, N. rESCMA: A brief summary on effect size conversion for meta-analysis. 2020.

- Riley, R.D.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Deeks, J.J. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ 2011. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Online), 2011; 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W.; Cheung, M.W.L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2010, 1, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solt, F. Measuring Income Inequality Across Countries and Over Time: The Standardized World Income Inequality Database. Soc Sci Q 2020, 101, 1183–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Health Organization Global Health Expenditure database. World Bank Group - Open Knowledge Repository.

- Ferguson, C.J. An Effect Size Primer: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2009, 40, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huedo-Medina, T.B.; Sánchez-Meca, J.; Marín-Martínez, F.; Botella, J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I 2 Index? Psychol Methods 2006, 11, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Farooq, N.; Bhatti, M.A.; Kuroiwa, C. Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of earthquake in Pakistan using Davidson trauma scale. J Affect Disord 2012, 136, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.A.; et al. High prevalence of somatisation in ICD-11 complex PTSD: A cross sectional cohort study. J Psychosom Res 2021, 148, 110574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayazi, T.; Lien, L.; Eide, A.H.; Ruom, M.; Hauff, E. What are the risk factors for the comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in a war-affected population? a cross-sectional community study in South Sudan. 2012. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/12/175.

- Baek, J.; et al. The validity of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in North Korean defectors using the International Trauma Questionnaire. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronner, M.B.; Peek, N.; Knoester, H.; Bos, A.P.; Last, B.F.; Grootenhuis, M.A. Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in parents after pediatric intensive care treatment of their child. J Pediatr Psychol 2010, 35, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Derivois, D. Assessment of prevalence and determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression symptoms in adults survivors of earthquake in Haiti after 30 months. J Affect Disord 2014, 159, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, M.; Paczkowski, M.; Galea, S.; Nemethy, K.; Péan, C.; Desvarieux, M. Psychopathology in the aftermath of the Haiti earthquake: A population-based study of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Depress Anxiety 2013, 30, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; et al. Depression and posttraumatic stress disorder in temporary settlement residents 1 year after the sichuan earthquake. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015, 27, NP1962–NP1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Lee, W.; Hyland, P. Factor structure and symptom classes of ICD-11 complex posttraumatic stress disorder in a South Korean general population sample with adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse Negl 2021, 114, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.H.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Depression in HIV-Infected and At-Risk Rwandan Women. 2009.

- Cofini, V.; Carbonelli, A.; Cecilia, M.R.; Binkin, N.; di Orio, F. Post traumatic stress disorder and coping in a sample of adult survivors of the Italian earthquake. Psychiatry Res 2015, 229, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eşsizoğlu, A.; Altınöz, A.E.; Sonkurt, H.O.; Kaya, M.C.; Köşger, F.; Kaptanoğlu, C. The risk factors of possible PTSD in individuals exposed to a suicide attack in Turkey. Psychiatry Res 2017, 253, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facer-Irwin, E.; Karatzias, T.; Bird, A.; Blackwood, N.; MacManus, D. PTSD and complex PTSD in sentenced male prisoners in the UK: Prevalence, trauma antecedents, and psychiatric comorbidities. Psychol Med 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gros, D.F.; Price, M.; Yuen, E.K.; Acierno, R. Predictors of completion of exposure therapy in OEF/OIF veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety 2013, 30, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; et al. Variation in post-traumatic response: the role of trauma type in predicting ICD-11 PTSD and CPTSD symptoms. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017, 52, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; et al. Are posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex-PTSD distinguishable within a treatment-seeking sample of Syrian refugees living in Lebanon? Global Mental Health 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; et al. Trauma, PTSD, and complex PTSD in the Republic of Ireland: prevalence, service use, comorbidity, and risk factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2021, 56, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, T.; et al. Risk factors and comorbidity of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: Findings from a trauma-exposed population based sample of adults in the United Kingdom. Depress Anxiety 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimerling, R.; Alvarez, J.; Pavao, J.; MacK, K.P.; Smith, M.W.; Baumrind, N. Unemployment among women: Examining the relationship of physical and psychological intimate partner violence and posttraumatic stress disorder. J Interpers Violence 2009, 24, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvedaraite, M.; Gelezelyte, O.; Kairyte, A.; Roberts, N.P.; Kazlauskas, E. Trauma exposure and factors associated with ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD in the Lithuanian general population. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; et al. Acculturation, psychiatric comorbidity and posttraumatic stress disorder in a Taiwanese aboriginal population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009, 44, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, K.L.; et al. Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance dependence: Predictors of change in PTSD symptom severity. J Clin Med 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.; Karatzias, T.; Busuttil, W.; Greenberg, N.; Shevlin, M. ICD-11 posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD) in treatment seeking veterans: risk factors and comorbidity. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2021, 56, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ;Nandi, A.; et al. Job loss, unemployment, work stress, job satisfaction, and the persistence of posttraumatic stress disorder one year after the september 11 attacks. J Occup Environ Med 2004, 46, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazderka, H.; et al. Isolation, Economic Precarity, and Previous Mental Health Issues as Predictors of PTSD Status in Females Living in Fort McMurray During COVID-19. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ;Powers, M.B.; et al. Predictors of PTSD symptoms in adults admitted to a Level I trauma center: A prospective analysis. J Anxiety Disord 2014, 28, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybojad, B.; Aftyka, A.; Baran, M.; Rzońca, P. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in Polish paramedics: A pilot study. Journal of Emergency Medicine 2016, 50, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.; Roberts, N.P.; Lewis, C.E.; van Gelderen, M.J.; Bisson, J.I. Associations between perceived social support, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD (CPTSD): implications for treatment. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2019, 10, 1573129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, M.L.; et al. Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatrics 2010, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramoto, C.; Matsunaga, A.; Nagata, S. Cross-sectional study of social support and psychological distress among displaced earthquake survivors in Japan. Japan Journal of Nursing Science 2015, 12, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, T.; et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome in an impoverished urban population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011, 33, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; et al. Validation of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD using the International Trauma Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2017, 136, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, T.; et al. Adverse and benevolent childhood experiences in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex PTSD (CPTSD): implications for trauma-focused therapies. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Bianchi, M.; Ahumada, F.; Araneda, A.; Botella, J. What is the Psychosocial Impact of Disasters? A Meta-Analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2018, 39, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Bianchi, M.; et al. Diseño y validación de una escala de impacto psicosocial de los desastres (SPSI-D). Revista de Sociología 2019, 34, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, G.; Drasch, K.; Jungbauer-Gans, M. The social stigma of unemployment: consequences of stigma consciousness on job search attitudes, behaviour and success. J Labour Mark Res 2019, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanos-Garrido, R.M.; Lopez-Valcarcel, B.G. The influence of the economic crisis on the association between unemployment and health: an empirical analysis for Spain. European Journal of Health Economics 2015, 16, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, Ó.R.; Buenadicha-Mateos, M.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. Overwhelmed by technostress? Sensitive archetypes and effects in times of forced digitalization. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasquilho, D.; et al. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: A systematic literature review Health behavior, health promotion and society. Feb. 03, 2016, BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).