Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Research Overview

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Contextualizing the Current Research with Insights from Our Previous Study

1.3. Focus of the Present Study

1.4. Research Questions

1.5. Literature Review

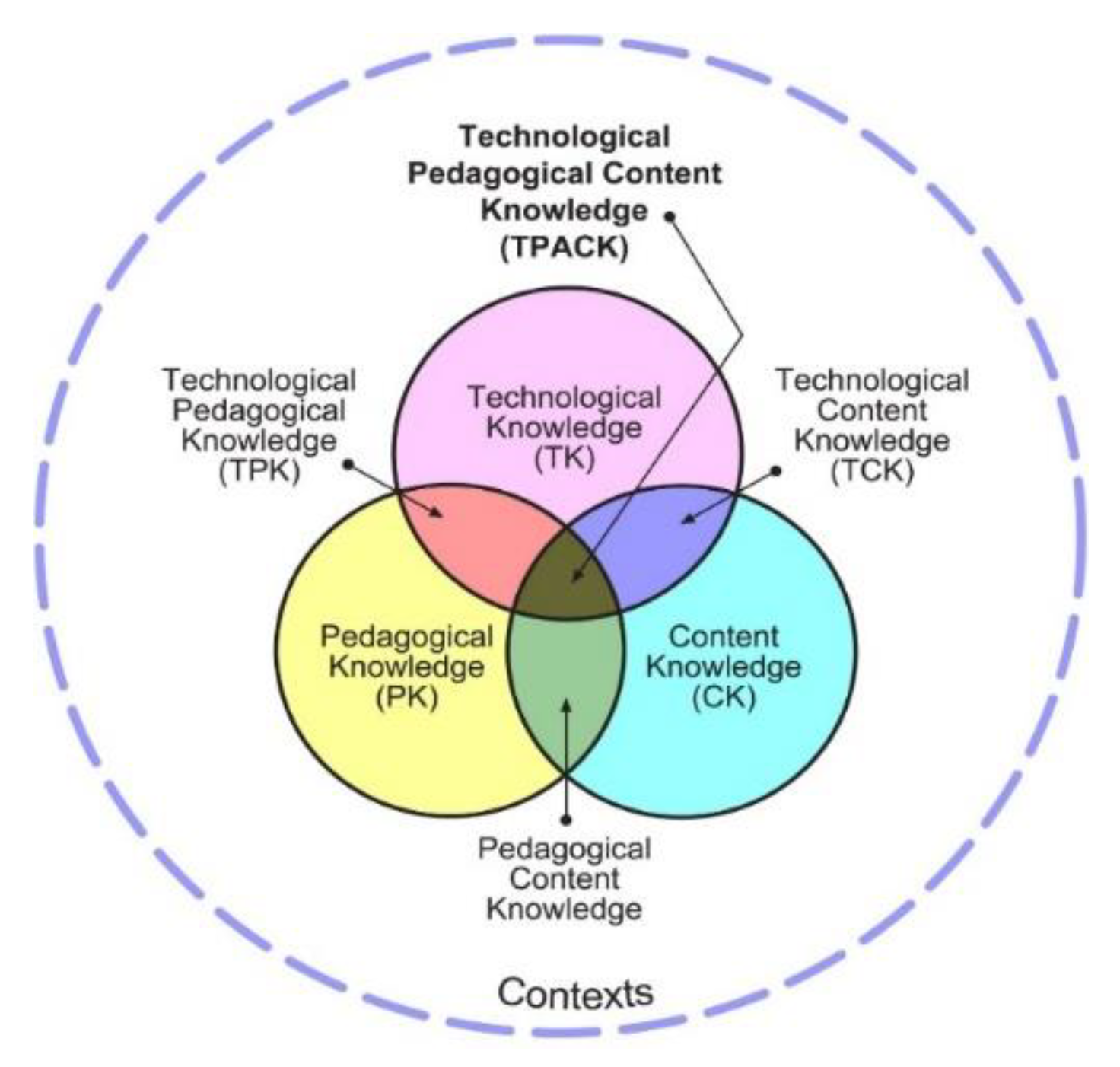

1.6. Theoretical Structure

2. Methodology

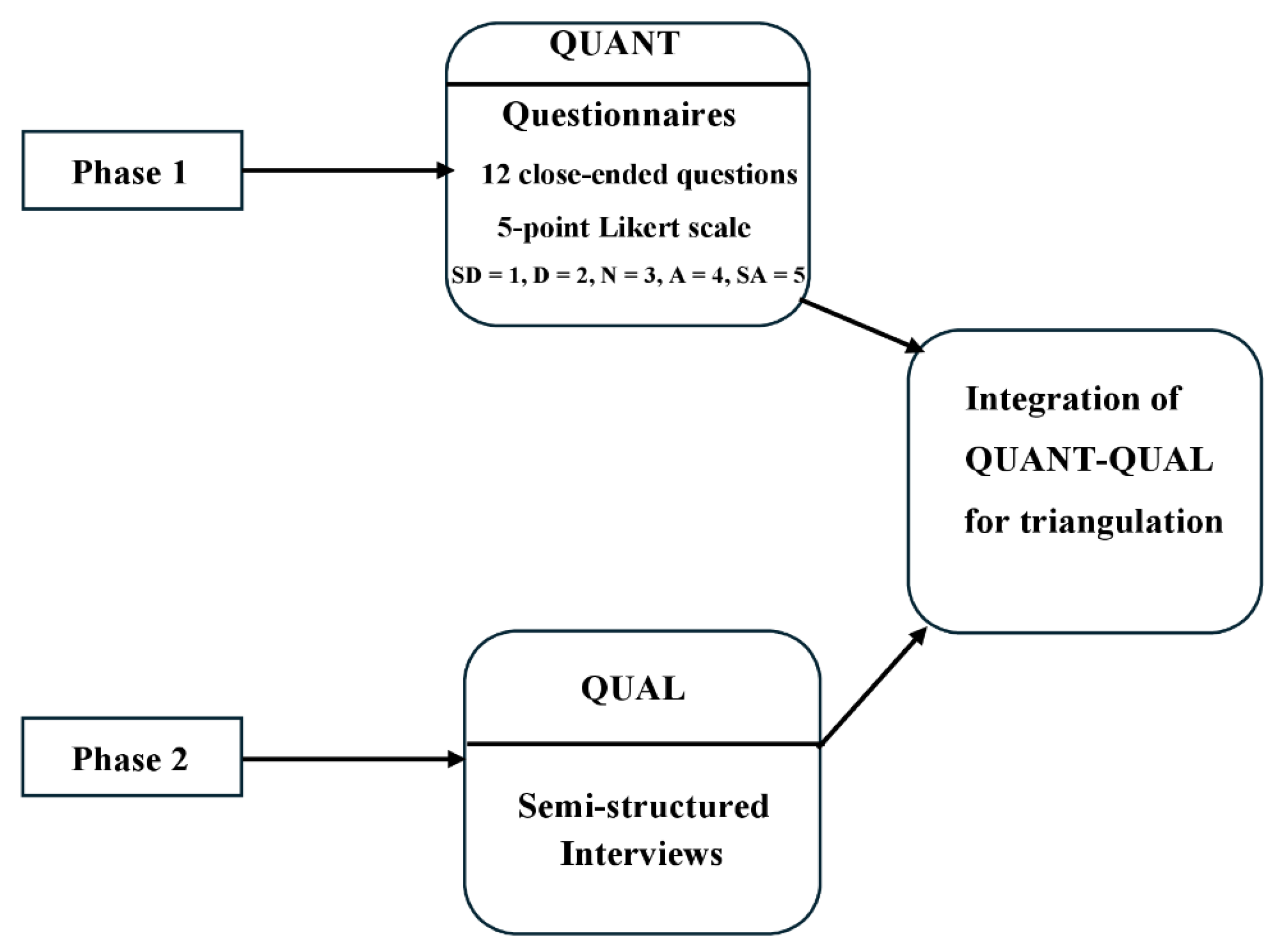

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Instrument Development and Validation

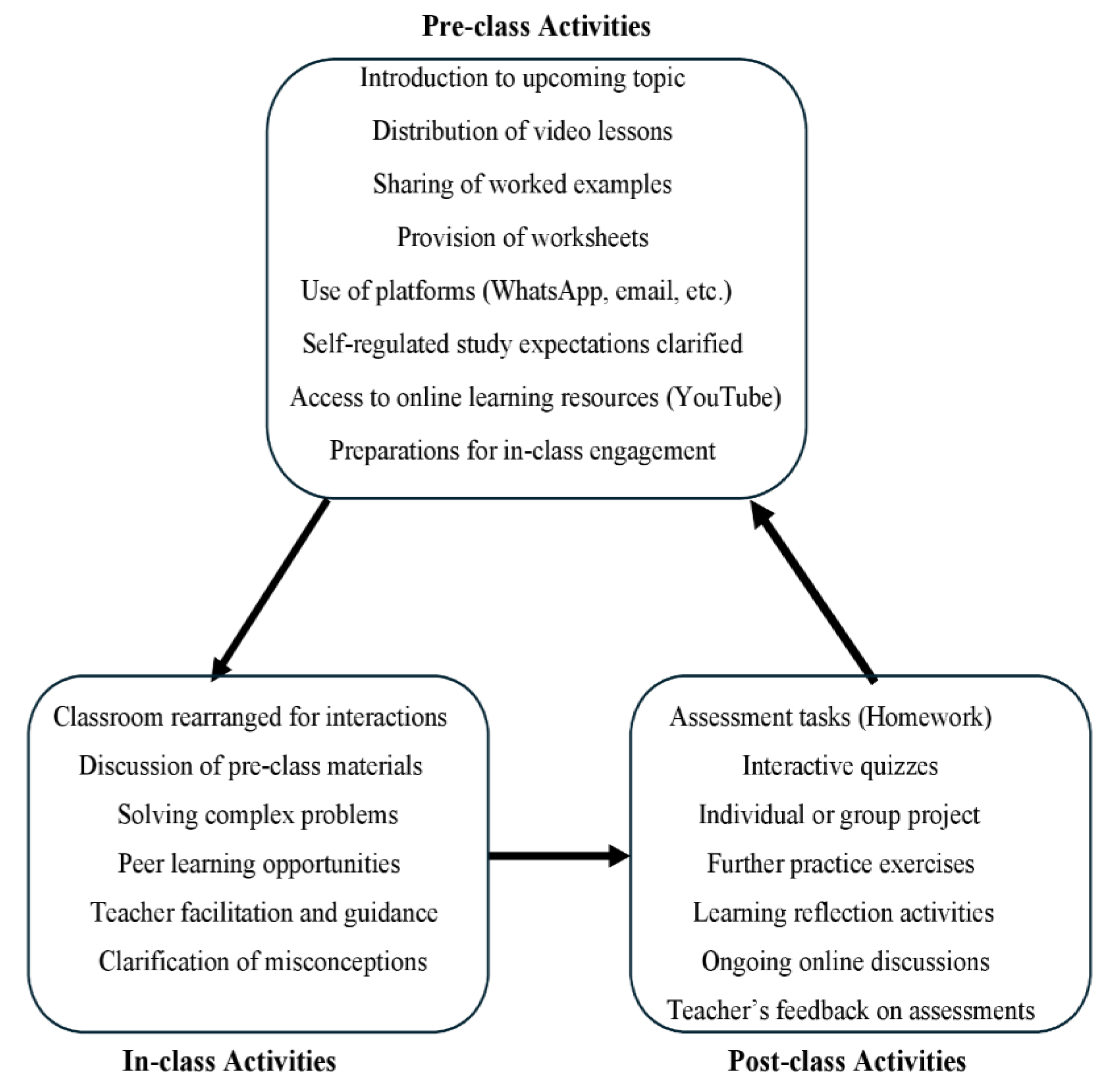

2.4. Prominent Strategies Implemented in the Flipped Mathematics Classrooms

2.5. Procedure for GatheringTeachers’ Flipped Mathematics Classroom Experiences

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Participants’ Demographic Details (n = 8)

3.2. Analysis of Teachers’ Responses to Questionnaire Items

| Rating Description | Score | Mean Rating | Interpretation |

| Strongly Disagree (SD) | 1 | 1.00 - 1.80 | Very Negative |

| Disagree (D) | 2 | 1,81 - 2.60 | Negative |

| Neutral (N) | 3 | 2.61 - 3.40 | Moderate |

| Agree (A) | 4 | 3.41 - 4.20 | Positive |

| Strongly Agree (SA) | 5 | 4.21 5.00 | Very Positive |

| S/N | Questionnaire-item | SD | D | N | A | SA | Mean | SD | Rating |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | x̅ | σ | |||

| Section B: Teaching Practices in Flipped Classrooms | |||||||||

| 1. | I find teaching in an FC setting easy, exciting and enjoyable. | 0 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 15 | 3.88 | 1.13 | Positive |

| 2. | I often provided structured guidance to my students for pre-class tasks. | 0 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 20 | 4.25 | 0.89 | Very Pos. |

| 3. | FC has enhanced my ability to clarify complex mathematics concepts. | 0 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 20 | 4.13 | 1.13 | Positive |

| 4. | I encouraged group work during in-class sessions. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 25 | 4.63 | 0.52 | Very Pos. |

| 5. | I adopted after-class online discussion for continued collaboration. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 4.63 | 0.52 | Very Pos. |

| 6. | The FC model has positively impacted my teaching practices. | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 20 | 4.38 | 0.74 | Very Pos. |

| Rating Average | 4.32 | 0.82 | Very Pos. | ||||||

| Section C: Opportunities in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | |||||||||

| 7. | Adopting FC model has resulted in a higher student engagement. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 25 | 4.63 | 0.52 | Very Pos. |

| 8. | FC approach fosters a greater student ownership of learning. | 0 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 20 | 4.13 | 1.13 | Positive |

| 9. | FC approach promotes collaborative learning among students | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 25 | 4.5 | 0.76 | Very Pos. |

| 10. | FC strategies develop students’ critical thinking & problem-solving skills | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 25 | 4.5 | 0.76 | Very Pos. |

| 11. | FC enables me to meet my students' individual needs better. | 0 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 15 | 4.13 | 0.83 | Positive |

| Rating Average | 4.38 | 0,8 | Very Pos. | ||||||

| Section D: Challenges in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | |||||||||

| 12. | Developing instructional materials such as video lessons and online content for flipped classes is challenging for me. | 2 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 1.69 | Moderate |

| 13. | Students often struggle with completing their pre-class tasks before class | 2 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 1.69 | Moderate |

| 14. | Limited technological resources hinder successful adoption of the FC model | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 20 | 4.5 | 0.53 | Very Pos. |

| 15. | Utilizing FC makes effective management of class time more difficult compared to traditional teaching methods. | 2 | 4 | 0 | 12 | 5 | 2.88 | 1.55 | Moderate |

| 16. | With FC, assessing student learning outcomes is more difficult relative to traditional teaching methods. | 3 | 4 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 2.5 | 1.6 | Negative |

| Rating Average | 3.18 | 1.41 | Moderate | ||||||

| Section E: General Perception of flipped mathematics classrooms | |||||||||

| 17. | FC approach can help senior secondary students understand and perform better in mathematics than traditional teaching methods. | 1 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 20 | 3.88 | 1.55 | Positive |

| 18. | I recommend the adoption of the FC model in senior secondary schools. | 0 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 20 | 4.13 | 1.13 | Positive |

| Rating Average | 4.01 | 1.34 | Positive | ||||||

| Overall | 3.98 | 1.04 | Positive | ||||||

| S/N | Questionnaire Item | Q | R | S | T | ||||

| Section B: Teaching Practices in Flipped Mathematics. Classroom | Q1 | Q2 | R1 | R2 | S1 | S2 | T1 | T2 | |

| 1. | I find teaching in a FC setting easy, exciting and enjoyable. | SA | SA | D | N | N | A | A | SA |

| 2. | I often provided structured guidance to my students for pre-class tasks. | SA | SA | N | N | A | SA | A | SA |

| 3. | FC has enhanced my ability to clarify complex mathematics concepts. | A | SA | N | D | A | SA | SA | SA |

| 4. | I encouraged group work activities during in-class sessions. | SA | SA | A | A | A | SA | SA | SA |

| 5. | I adopted after-class online discussion for continued collaboration. | SA | SA | A | A | A | SA | SA | SA |

| 6. | FC model has positively impacted my teaching practices. | A | SA | N | A | SA | SA | SA | A |

| Section C: Opportunities in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | |||||||||

| 7. | Adopting FC has resulted in a higher student engagement in my classes. | SA | SA | A | A | A | SA | SA | SA |

| 8. | FC approach fosters a greater student ownership of learning. | SA | A | D | N | A | SA | SA | SA |

| 9. | FC promotes collaborative learning among students | SA | SA | D | A | A | SA | SA | SA |

| 10. | FC strategies develop students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. | SA | SA | D | A | A | SA | SA | SA |

| 11. | FC enables me to meet my students' individual needs better. | SA | A | D | A | A | SA | SA | SA |

| Section D: Challenges in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | |||||||||

| 12. | Developing instructional materials such as video lessons and online content for flipped classes is challenging for me. | SD | SD | SA | SA | A | A | D | D |

| 13. | Students often struggle with completing their pre-class tasks before class. | SD | D | SA | SA | A | A | D | SD |

| 14. | Limited technological resources hinder successful adoption of the FC model. | SA | SA | A | SD | A | A | A | SA |

| 15. | Utilizing FC approach makes effective management of class time more difficult compared to traditional teaching methods. | SD | SD | SA | A | A | A | D | D |

| 16. | With FC, assessing student learning outcomes is more difficult relative to traditional teaching methods. | SD | SD | SA | A | A | D | D | SD |

| Section E: General Perception of flipped mathematics classrooms | |||||||||

| 17. | FC approach can help senior secondary students understand and perform better in mathematics than traditional teaching methods. | SA | SA | SD | D | A | A | SA | SA |

| 18. | I recommend the adoption of the FC model in senior secondary schools. | SA | SA | D | N | A | A | SA | SA |

| S/N | Questionnaire-item | Q1 | Q2 | R1 | R2 | S1 | S2 | T1 | T2 |

| Section B: Teaching Practices in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | |||||||||

| 1. | I find teaching in an FC setting easy, exciting and enjoyable. | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. | I often provided structured guidance to my students for pre-class tasks. | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. | FC has enhanced my ability to clarify complex mathematics concepts. | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 4. | I encouraged group work activities during in-class sessions. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 5. | I adopted after-class online discussion for continued collaboration. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 6. | FC model has positively impacted my teaching practices. | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Section C: Opportunities in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | |||||||||

| 7. | Adopting FC model has resulted in a higher student engagement in my classes. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 8. | FC approach fosters a greater student ownership of learning. | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 9. | FC approach promotes collaborative learning among students | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 10. | FC strategies develop students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. | 5 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 11. | FC enables me to meet my students' individual needs better. | 5 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Section D: Challenges in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | |||||||||

| 12. | Developing instructional materials such as video lessons and online content for flipped classes is challenging for me. | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 13. | Students often struggle with completing their pre-class tasks before class. | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 14. | Limited technological resources hinder successful adoption of the FC model. | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 15. | Utilizing the FC approach makes effective management of class time more difficult compared to traditional teaching methods. | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 16. | With FC, assessing student learning outcomes is more difficult relative to traditional teaching methods. | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Section E: General Perception of flipped mathematics classrooms | |||||||||

| 17. | FC approach can help senior secondary students understand and perform better in mathematics than traditional teaching methods. | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 18. | I recommend the adoption of the FC model in senior secondary schools. | 5 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

3.2.1. Test Interpretation

3.3. Analysis of Teachers’ Responses to Semi-structured Interviews

|

1. Can you explain briefly how you implemented the flipped classroom model in your mathematics classes? 2. Have there been any changes in student engagement or performance resulting from flipping your mathematics classroom? Elaborate on your answer please. 3. Can you identify any major factors that adversely affected your ability to implement the approach fully? 4. What tools or resources were most helpful in your adoption of the flipped classroom? 5. How were you able to obtain or develop those tools or resources? 6. Are there particular tools, materials or platforms you wish were available that could have improved your flipped classroom teaching? 7. What changes would you suggest are needed to improve the implementation of flipped classrooms in senior secondary mathematics? |

3.3.1. Teacher Support Needs for Effective Flipping of Mathematics Classrooms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions, Limitations and Recommendations

6. Implications of the Study for Policy and Practice

- ∗

- This research expands current knowledge on innovative pedagogical strategies by examining the implementation of flipped classrooms in Nigerian senior secondary schools, a context typical of developing nations.

- ∗

- By examining teacher-identified opportunities and challenges in flipped mathematics classrooms, this study pinpoints the key factors affecting student engagement and academic achievement, which can optimize the approach to meet students' educational needs more effectively.

- ∗

- Teacher insights may guide recommendations for professional development initiatives supporting successful adoption of the flipped classroom model in Nigerian senior secondary schools, with applications extending beyond Mathematics to other subjects.

- ∗

- The study’s findings offer valuable pedagogical practices for flipped classrooms, shaping future educational policies for improved mathematics education in Nigeria and worldwide

Conflicts of Interests

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Diri, E.A. Flipped classroom model and senior secondary school students’ mathematics achievement in Kolokuma/Opokuma LGA, Bayelsa State, Nigeria. Faculty of Natural and Applied Sciences. Journal of Mathematics, and Science Education 2024, 5, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Paragoo, S.; Sevnarayan, K. Flipped classrooms for engaged learning during the pandemic: Teachers' perspectives and challenges in a South African high school. Technology-mediated Learning During the Pandemic 2024, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, K.K.; Chang, C.-N.; Chang, C.-Y. The impact of the flipped classroom on mathematics concept learning in high school. Educational Technology & Society 2016, 19, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Mazana, M.Y.; Montero, C.S.; Casmir, R.O. Investigating students’ attitude towards learning mathematics. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education 2018, 14, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, J.; Sams, A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. International Society for Technology in Education. 2012.

- Timayi, J.M.; Bolaji, C.; Kajuru, Y.K. Flipped classroom model and multiplicative thinking among middle basic pupils of varied abilities in Gombe State, Nigeria. Faculty of Natural and Applied Sciences Journal of Mathematics, and Science Education 2024, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K.R. The effects of the flipped model of instruction on student engagement and performance in the secondary mathematics classroom. Journal of Educators online 2015, 12, 91–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igcasama, R.; Amante, E.; Benigay DJ, P.; Mabanag, B.; Monilar, D.I.; Kilag, O.K. A paradigm shift in education: Impact of flipped classrooms on high school mathematics conceptual mastery. Excellencia: International Multi-Disciplinary Journal of Education (2994-9521) 2023, 1, 465–476. [Google Scholar]

- Sablan, J.R.; Prudente, M. Traditional and flipped learning: Which enhances students' academic performance better. International Journal of Information and Education Technology 2022, 12, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraets, J. The Effects That a flipped classroom has on engagement and academic performance for high school mathematics students. [Master’s Dissertation, Minnesota State University Moorhead]. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Unal, A.; Unal, Z.; Bodur, Y. Using flipped classroom in middle schools: Teachers' perceptions. Journal of Research in Education 2021, 30, 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- O'Flaherty, J.; Phillips, C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: A scoping review. The Internet and Higher Education 2015, 25, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satparam, J.; Apps, T. A systematic review of the flipped classroom research in K-12: Implementation, challenges and effectiveness. Journal of Education, Management and Development Studies 2022, 2, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, A.; Saleem, M. Implementation of FCM approach: Challenges before teachers and identification of gaps. Contemporary Educational Technology 2022, 14, ep394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, T. Flipping the learning of mathematics: Different enactments of mathematics instruction in secondary classrooms. International Journal for Mathematics Teaching and Learning 2019, 20, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.T.; Chai, C.S.; Wang, L.J. Exploring secondary school teachers’ TPACK for video-based flipped learning: The role of pedagogical beliefs. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 27, 8793–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppong, E.K.; Quansah, F.; Boachie, S. Improving Pre-Service Science Teachers' Performance in Nomenclature of Aliphatic Hydrocarbons Using Flipped Classroom Instruction. Science Education International 2022, 33, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baingana, J.K. The impact of flipped classroom models on K-12 education in African countries: Challenges, opportunities, and effectiveness. Research Invention Journal of Research in Education 2024, 3, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Barakabitze, A.A.; William-Andey Lazaro, A.; Ainea, N.; Mkwizu, M.H.; Maziku, H.; Matofali, A.X.; Sanga, C. Transforming African education systems in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) using ICTs: Challenges and opportunities. Education Research International 2019, 2019, 6946809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterhalter, E. Measuring education for the millennium development goals: Reflections on targets, indicators, and a post-2015 framework. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 2014, 15, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Republic of Nigeria. National Policy on Education (6th ed.). NERDC Press. 2013.

- Ukpong, J.S.; Alabekee, C.; Ugwumba, E.; Ed, M. The challenges and prospects in the implementation of the national education system: The case of 9-3-4. The Pacific Journal of Science and Technology 2023, 24, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Egugbo, C.C.; Salami, A.T. Policy Analysis of the 6-3-3-4 Policy on Education in Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa 2021, 23, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi, T.O. Credit in mathematics in senior secondary certificate examinations as a predictor in educational management in universities in Ondo and Ekiti States. Nigeria. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 2010, 5, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.F.; Yahaya, L.A.; Adewara, A.A. Mathematics education in Nigeria: Gender and spatial dimensions of enrolment. International Journal of Embedded Systems 2011, 3, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agah, M.P. The relevance of mathematics education in the Nigerian contemporary society: Implications to secondary education. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science 2020, 33, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, S.O. Impact of flipped classroom on mathematics learning outcome of senior secondary school students in Lagos, Nigeria. African Journal of Teacher Education 2020, 9, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obienyem, B.I.; Ugwuanyi, C.C. Use of flipped classroom instructional approach in teaching and learning of mathematics in secondary schools: Challenges and prospects. African Journal of Science, Technology and Mathematics Education 2024, 10, 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Egara, F.O.; Mosimege, M. Effect of flipped classroom learning approach on mathematics achievement and interest among 822 secondary school students. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 8131–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efiuvwere, R.A.; Fomsi, E.F. Flipping the mathematics classroom to enhance senior secondary students’ interest. International Journal of Mathematics Trends and Technology 2019, 65, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; O'Brien, D. The importance of crafting a good introduction to scholarly research: Strategies for creating an effective and impactful opening statement. International Journal of Medical Education 2023, 14, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiyantoro, S. Analysis of teachers' perceptions of the benefits and challenges of adopting the flipped learning model. Indonesian Journal of Instructional Media and Model 2023, 5, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnish, K. Privacy in research ethics. Handbook of research ethics and scientific integrity 2020, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge.

- Holmes, S.R.; Reinke, W.M.; Herman, K.C.; David, K. An examination of teacher engagement in intervention training and sustained intervention implementation. School Mental Health, 2022, 14, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. The ethics of educational and social research. In Research methods in education (8th ed., pp. 111-143). Routledge. 2017.

- Elangovan, N.; Sundaravel, E. Method of preparing a document for survey instrument validation by experts. MethodsX 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A. (2017). Reliability, Cronbach’s alpha. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods (Vol. 4, pp. 1415-1417). SAGE Publications, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Arias, F.D.; Navarro, M.; Elfanagely, Y.; Elfanagely, O. (2023). Biases in research studies. In Translational Surgery (pp. 191-194). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Naccarato, E.; Karakok, G. Expectations and implementations of the flipped classroom model in undergraduate mathematics courses. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology 2015, 46, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen E, Ö. Perspectives of mathematics instructors on the flipped learning model. Cukurova University Faculty of Education Journal 2022, 51, 566–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, E.; DeJong, D.; Grundmeyer, T.; Baron, M. K-12 teacher perceptions regarding the flipped classroom model for teaching and learning. Journal of Educational Technology Systems 2017, 45, 390–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmawati, V.; Setyaningrum, W.; Retnawati, H. (2019, October). Flipped classroom in mathematics instruction: Teachers’ perception. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1320, No. 1, p. 012088). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voithofer, R.; Nelson, M.J. Teacher educator technology integration preparation practices around TPACK in the United States. Journal of Teacher Education 2021, 72, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, E.; Göre, B.T. A scale development study to use the flipped classroom model in mathematics education. Necatibey Faculty of Education Electronic Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 2024, 18, 503–533.387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. (2022). Exploring the relationship between teachers’ subjects and technology self-efficacy in the flipped classroom in TPACK framework and Rasch model [Master's dissertation, The Ohio State University].

- Ramadhani, R.; Syahputra, E.; Simamora, E. Ethnomathematics approach integrated flipped classroom model: Culturally contextualized meaningful learning and flexibility. Jurnal Elemen 2023, 9, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Services Research 2013, 48 Pt 2, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes-Brown, T.K. Using theoretical models in mixed methods research: An example from an explanatory sequential mixed methods study exploring teachers' beliefs and use of technology. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 2023, 17, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maforah, N.; Leburu-Masigo, G. (2018). Application of the mixed methods research using sequential explanatory design. In ICERI2018 Proceedings (pp. 9710-9715). IATED.

- Fassett, K.T.; Wolcott, M.D.; Harpe, S.E.; McLaughlin, J.E. Considerations for writing and including demographic variables in education research. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 2022, 14, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegenfuss, J.Y.; Easterday, C.A.; Dinh, J.M.; JaKa, M.M.; Kottke, T.E.; Canterbury, M. Impact of demographic survey questions on response rate and measurement: A randomized experiment. Survey Practice 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asún, R.A.; Rdz-Navarro, K.; Alvarado, J.M. Developing multidimensional Likert scales using item factor analysis: The case of four-point items. Sociological Methods & Research 2016, 45, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, L.; Mohamed, H.B. Enhancing student motivation in a flipped classroom: An investigation of innovative teaching strategies to improve student learning. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice 2023, 29, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, K.; Choi, M. Qualitative interviews. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection 2018, 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kakilla, C. Strengths and weaknesses of semi-structured interviews in qualitative research: A critical essay. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Schuele, C. (2010). Demographics. In Encyclopedia of Research Design (Vol. 0, pp. 347-347). SAGE Publications, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A.S.; Broussard, K.A.; Sterns, J.L.; Sanders, K.K.; Shardy, J.C. Who are we studying? Sample diversity in teaching of psychology research. Teaching of Psychology 2015, 42, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etebu, E.; Amatari, V.O. Impact of teachers’ educational qualification on senior secondary students’ academic achievement in biology in Bayelsa State. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) 2020, 25, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, G.; Hayfield, N.; Clarke, V.; Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. In C. Willig & W. S. Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology (pp. 17-36). SAGE Publications Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Oakes, D.; Davies, A.; Joubert, M.; Lyakhova, S. Exploring teachers’ and students’ responses to the use of a flipped classroom teaching approach in mathematics. BSRLM Proceedings, King’s Col. London 2018, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Şen E, Ö.; Hava, K. Prospective middle school mathematics teachers’ points of view on the flipped classroom. Education and Information Technologies 2020, 25, 3465–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhandl, R.; Lavicza, Z.; Schallert, S. Towards flipped learning in upper secondary mathematics education. Journal of Mathematics Education) 2020, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elian, Y.B. Flipped Learning: A teacher’s perspective. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Attard, C.; Holmes, K. An exploration of teacher and student perceptions of blended learning in four secondary mathematics classrooms. Mathematics Education Research Journal 2022, 34, 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivola, M.K. Flipped learning – Why teachers flip and what are their worries? Experiences of teaching with Mathematics. Sciences and Technology 2016, 2, 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Debacco, M. Teachers’ and administrators’ perspectives on the flipped classroom: A qualitative study in a high school setting. [Doctoral thesis, Ashford University]. 2020.

- Suebwongsuwan, W.; Nomnian, S. Thai hotel undergraduate interns’ awareness and attitudes towards English as a lingua franca. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics 2020, 9, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Category | Q1 | Q2 | R1 | R2 | S1 | S2 | T1 | T2 | Total |

| Gender | Male | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 4 | ||||

| Female | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 4 | |||||

| Age | Below 30 | 0 | ||||||||

| 30 - 50 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 6 | |||

| 51 - 55 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 2 | |||||||

| Above 55 | 0 | |||||||||

| Years of Teaching Experience |

0 - 10 | 0 | ||||||||

| 11 - 20 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 6 | |||

| 21 - 35 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 2 | |||||||

| Highest Qualification |

B.Ed. | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 3 | |||||

| B.A./B.Sc. | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 🗸 | 5 |

| S/N | Questionnaire-item | SD | D | N | A | SA |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Section B: Teaching Practices in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | ||||||

| 1. | I find teaching in an FC setting easy, exciting and enjoyable. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 2. | I often provided structured guidance to my students for pre-class tasks. | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| 3. | FC has enhanced my ability to clarify complex mathematical concepts during class time. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 4. | I encouraged group work activities during in-class sessions. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| 5. | I adopted after-class online discussion for continued collaboration. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| 6. | The flipped classroom model has positively impacted my teaching practices. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Section C: Opportunities in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | ||||||

| 7. | Adopting FC model has resulted in a higher student engagement. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| 8. | FC approach fosters a greater student ownership of learning. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 9. | FC approach promotes collaborative learning among students | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 10. | FC strategies develop students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 11. | FC enables me to meet my students' individual needs better. | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Section D: Challenges in Flipped Mathematics Classrooms | ||||||

| 12. | Developing instructional materials such as video lessons and online content for flipped classes is challenging for me. | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 13. | Students often struggle with completing their pre-class tasks before class. | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 14. | Limited technological resources hinder successful adoption of FC for mathematics instruction. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 15. | Utilizing FC approach makes effective management of class time more difficult compared to traditional teaching methods. | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 16. | With FC, assessing student learning outcomes is more difficult relative to traditional methods. | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Section E: General Perception of flipped mathematics classrooms | ||||||

| 17. | FC approach can help senior secondary students understand and perform better in mathematics than traditional teaching methods. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| 18. | I recommend the adoption of the flipped mathematics classrooms in senior secondary schools. | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Groups: | Q1 | Q2 | R1 | R2 | S1 | S2 | T1 | T2 |

| Skewness | -1.339 | -1.3872 | .07073 | -.8744 | 0 | -1.856 | -1.1674 |

-1.4822 |

| Excess kurtosis | -.07969 | .1825 | -1.3485 | 0.6432 | 8.5 | 4.5886 | -0.3885 | .4972 |

| Normality | .000006745 | .00001096 | .03274 | .01608 | 5.14e-7 | .00004464 | .00002742 | .000006112 |

| Outliers | 1, 1, 1, 1 | 1, 2, 1, 1 | 1 | 3, 5 | 2 | 2, 2, 2, 2 | 2, 1, 2, 1 |

|

| Median | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Sample size (n) | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 |

| Rank sum (R) Mean Rank |

1483 82.39 |

1496.5 83.14 |

895.5 49.75 |

912.5 50.69 |

1063.5 59.08 |

1542 85.67 |

1482.5 82.36 |

1564.5 86.92 |

| R2/n |

122182.72 |

124417.35 | 44551.15 | 46258.68 | 62835.13 | 132098 | 122100.345 | 135981.123 |

| Pair | Mean Rank difference |

Z | SE | Critical value |

p-value | p-value/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x1 - x2 | -0.75 | 0.05758 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.9541 | 0.477 |

| x1 - x3 | 32.6389 | 2.5058 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.01222 | 0.006109 |

| x1 - x4 | 31.6944 | 2.4333 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.01496 | 0.007481 |

| x1 - x5 | 23.3056 | 1.7892 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.07358 | 0.03679 |

| x1 - x6 | -3.2778 | 0.2516 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.8013 | 0.4007 |

| x1 - x7 | 0.02778 | 0.002133 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.9983 | 0.4991 |

| x1 - x8 | -4.5278 | 0.3476 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.7281 | 0.3641 |

| x2 - x3 | 33.3889 | 2.5634 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.01037 | 0.005183 |

| x2 - x4 | 32.4444 | 2.4909 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.01274 | 0.006372 |

| x2 - x5 | 24.0556 | 1.8468 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.06477 | 0.03239 |

| x2 - x6 | -2.5278 | 0.1941 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.8461 | 0.4231 |

| x2 - x7 | 0.7778 | 0.05971 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.9524 | 0.4762 |

| x2 - x8 | -3.7778 | 0.29 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.7718 | 0.3859 |

| x3 - x4 | -0.9444 | 0.07251 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.9422 | 0.4711 |

| x3 - x5 | -9.3333 | 0.7165 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.4737 | 0.2368 |

| x3 - x6 | -35.9167 | 2.7574 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.005826 | 0.002913 |

| x3 - x7 | -32.6111 | 2.5037 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.01229 | 0.006146 |

| x3 - x8 | -37.1667 | 2.8534 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.004325 | 0.002163 |

| x4 - x5 | -8.3889 | 0.644 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.5195 | 0.2598 |

| x4 - x6 | -34.9722 | 2.6849 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.007255 | 0.003627 |

| x4 - x7 | -31.6667 | 2.4312 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.01505 | 0.007525 |

| x4 - x8 | -36.2222 | 2.7809 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.005421 | 0.00271 |

| x5 - x6 | -26.5833 | 2.0409 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.04126 | 0.02063 |

| x5 - x7 | -23.2778 | 1.7871 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.07392 | 0.03696 |

| x5 - x8 | -27.8333 | 2.1369 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.03261 | 0.0163 |

| x6 - x7 | 3.3056 | 0.2538 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.7997 | 0.3998 |

| x6 - x8 | -1.25 | 0.09597 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.9235 | 0.4618 |

| x7 - x8 | -4.5556 | 0.3497 | 13.0254 | 40.6872 | 0.7265 | 0.3633 |

| Group | Q2 | R1 | R2 | S1 | S2 | T1 | T2 |

| Q1 | -0.75 | 32.64 | 31.69 | 23.31 | -3.28 | 0.028 | -4.53 |

| Q2 | 0 | 33.39 | 32.44 | 24.06 | -2.53 | 0.78 | -3.78 |

| R1 | 33.39 | 0 | -0.94 | -9.33 | -35.92 | -32.61 | -37.17 |

| R2 | 32.44 | -0.94 | 0 | -8.39 | -34.97 | -31.67 | -36.22 |

| S1 | 24.06 | -9.33 | -8.39 | 0 | -26.58 | -23.28 | -27.83 |

| S2 | -2.53 | -35.92 | -34.97 | -26.58 | 0 | 3.31 | -1.25 |

| T1 | 0.78 | -32.61 | -31.67 | -23.28 | 3.31 | 0 | -4.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).