Submitted:

01 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

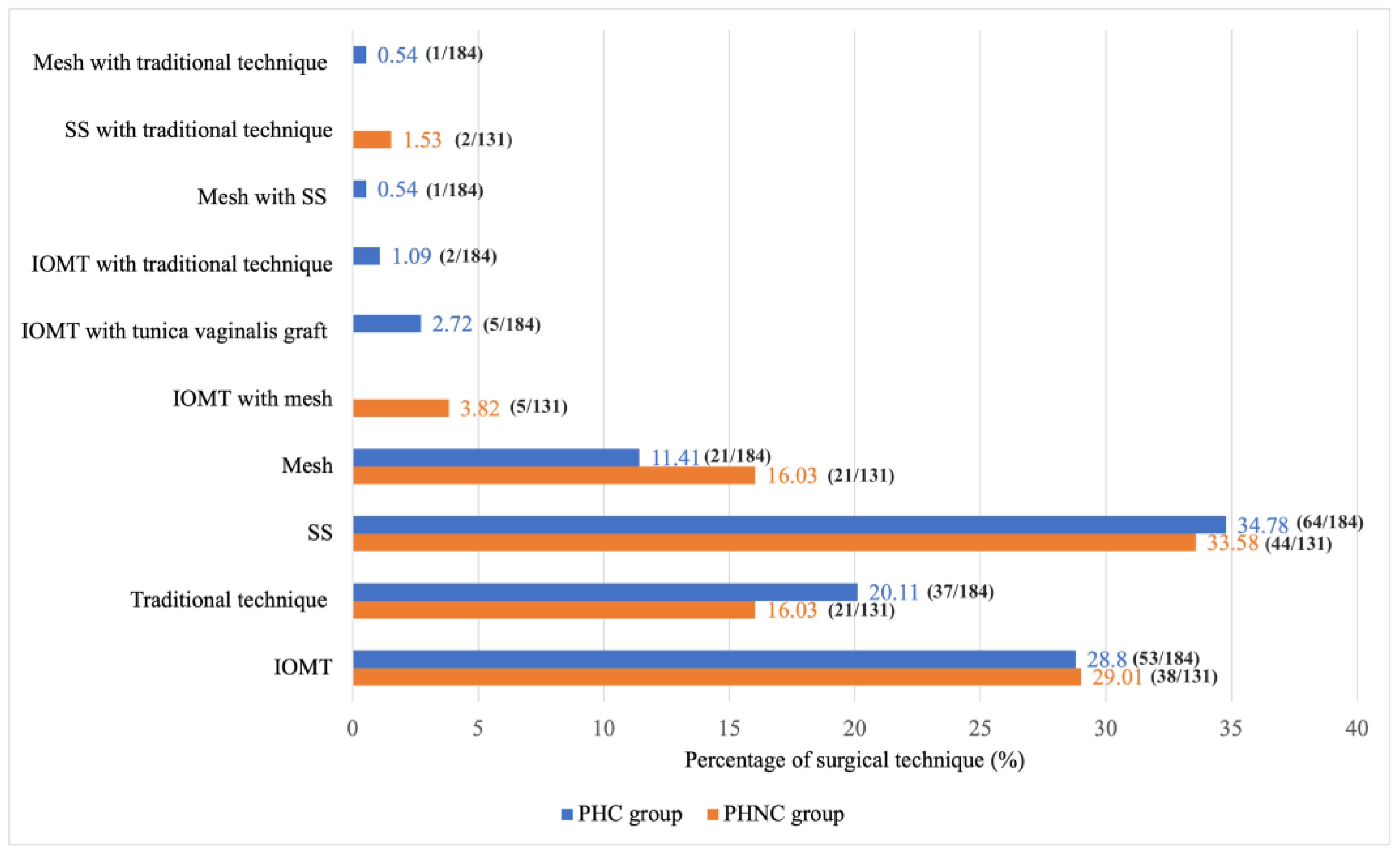

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Case Selection

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Medical Treatments

2.6. Surgical Procedure

2.7. Postoperative Outcome and Follow-Up

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

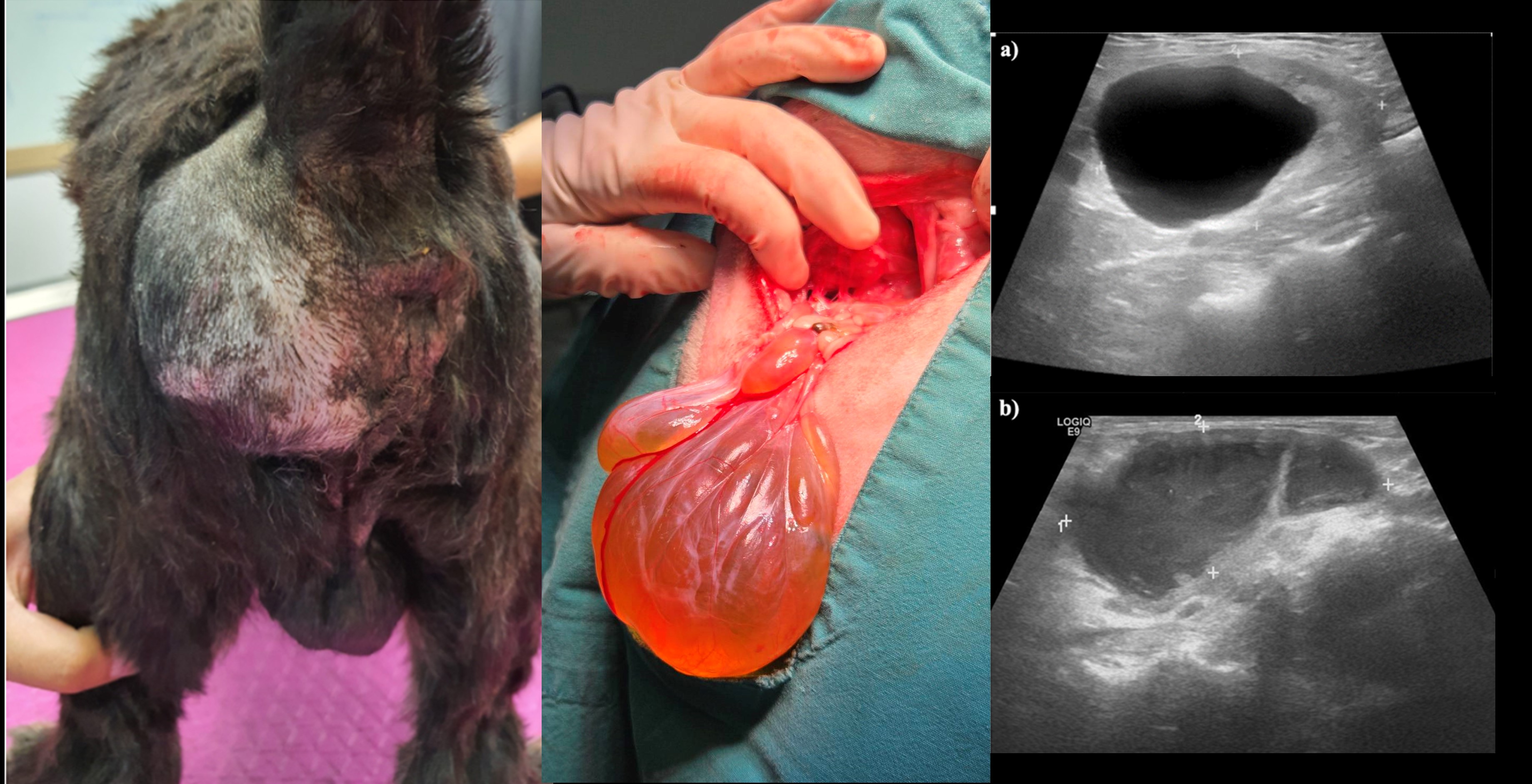

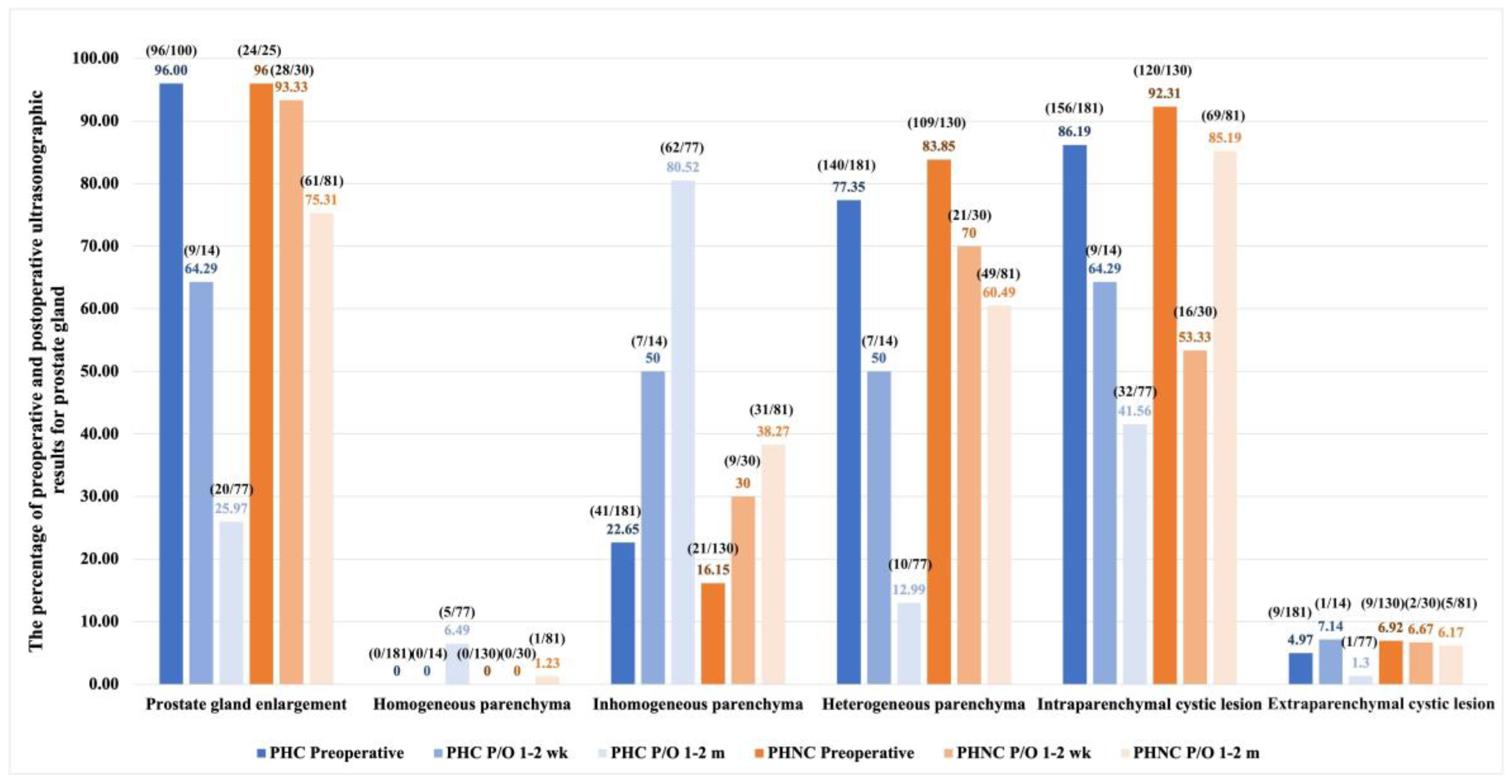

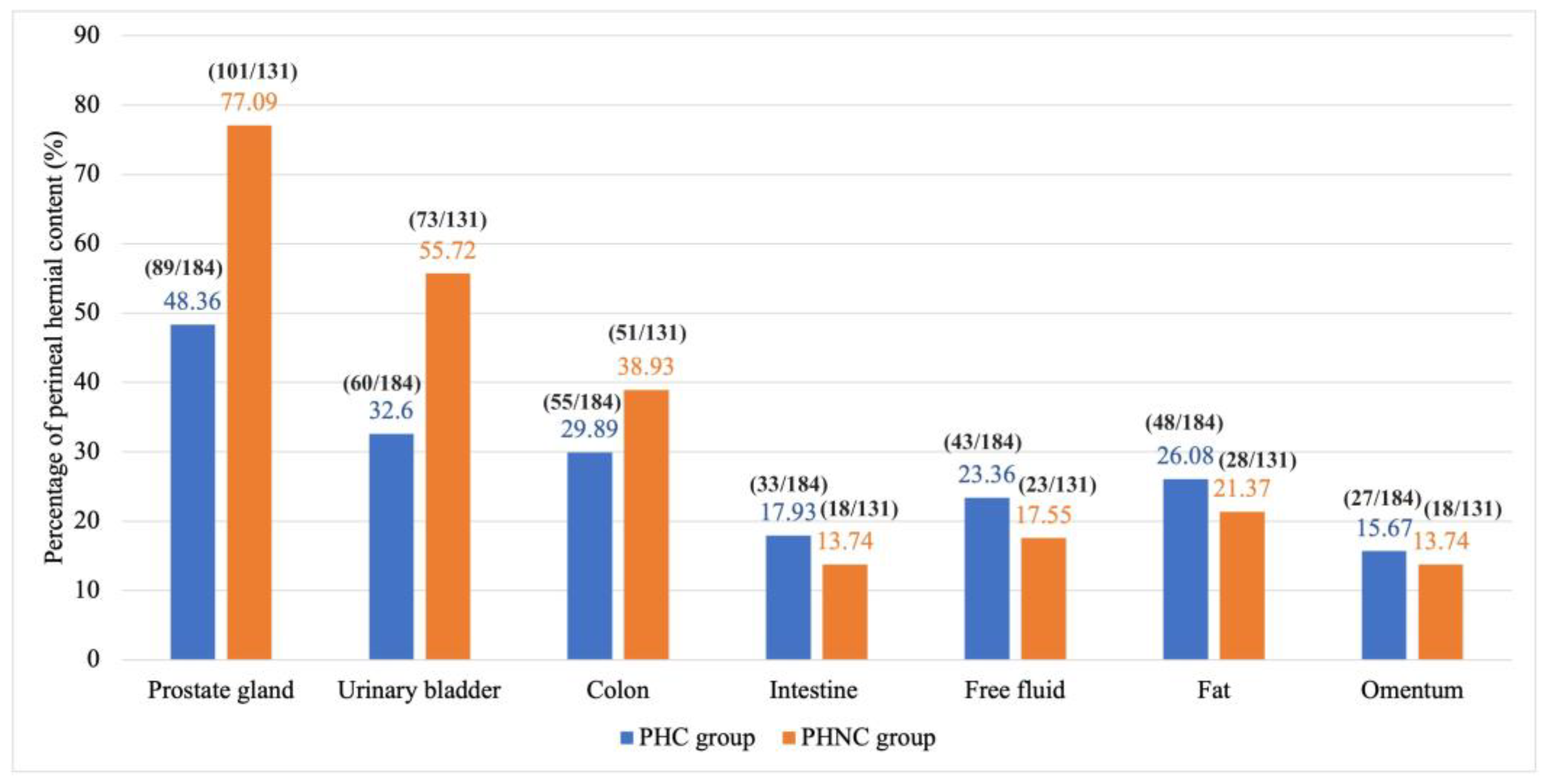

3.1. Signalment and Pre-Operative Findings

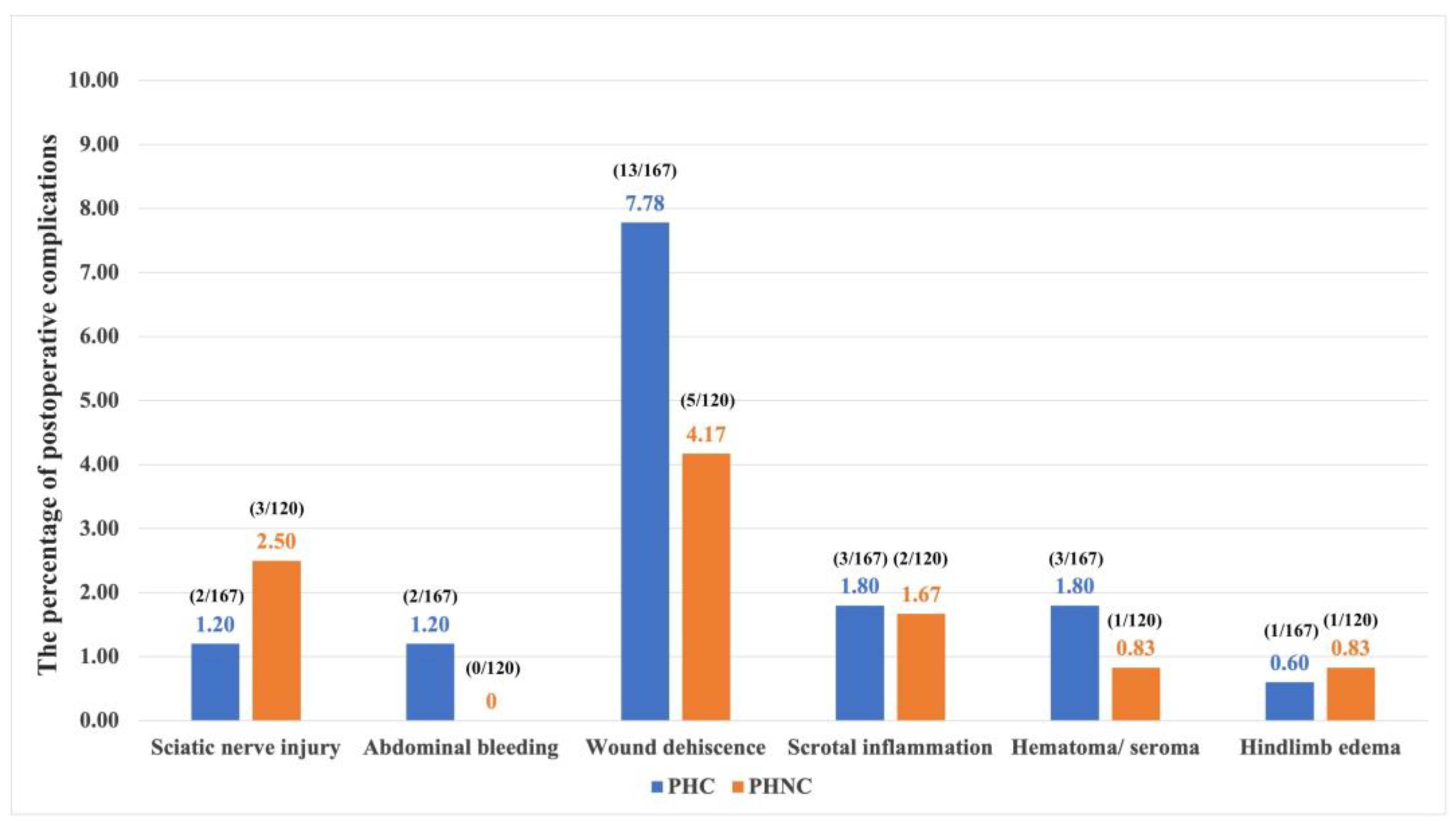

3.3. Postoperative Outcome and Follow-Up

3.3.1. Postoperative Phase (1-2 Weeks)

3.3.2. Short-Term Phase (1-2 Months)

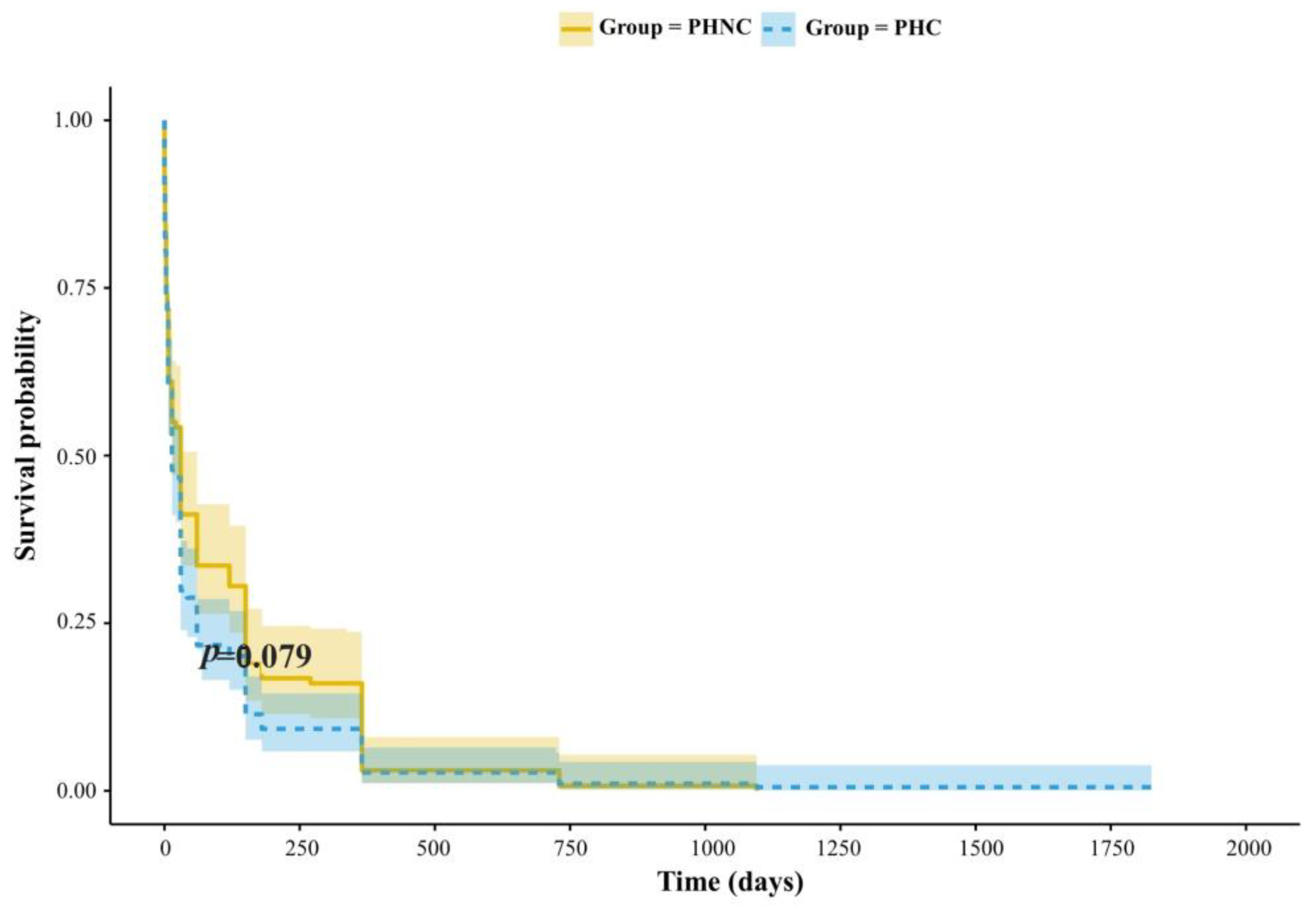

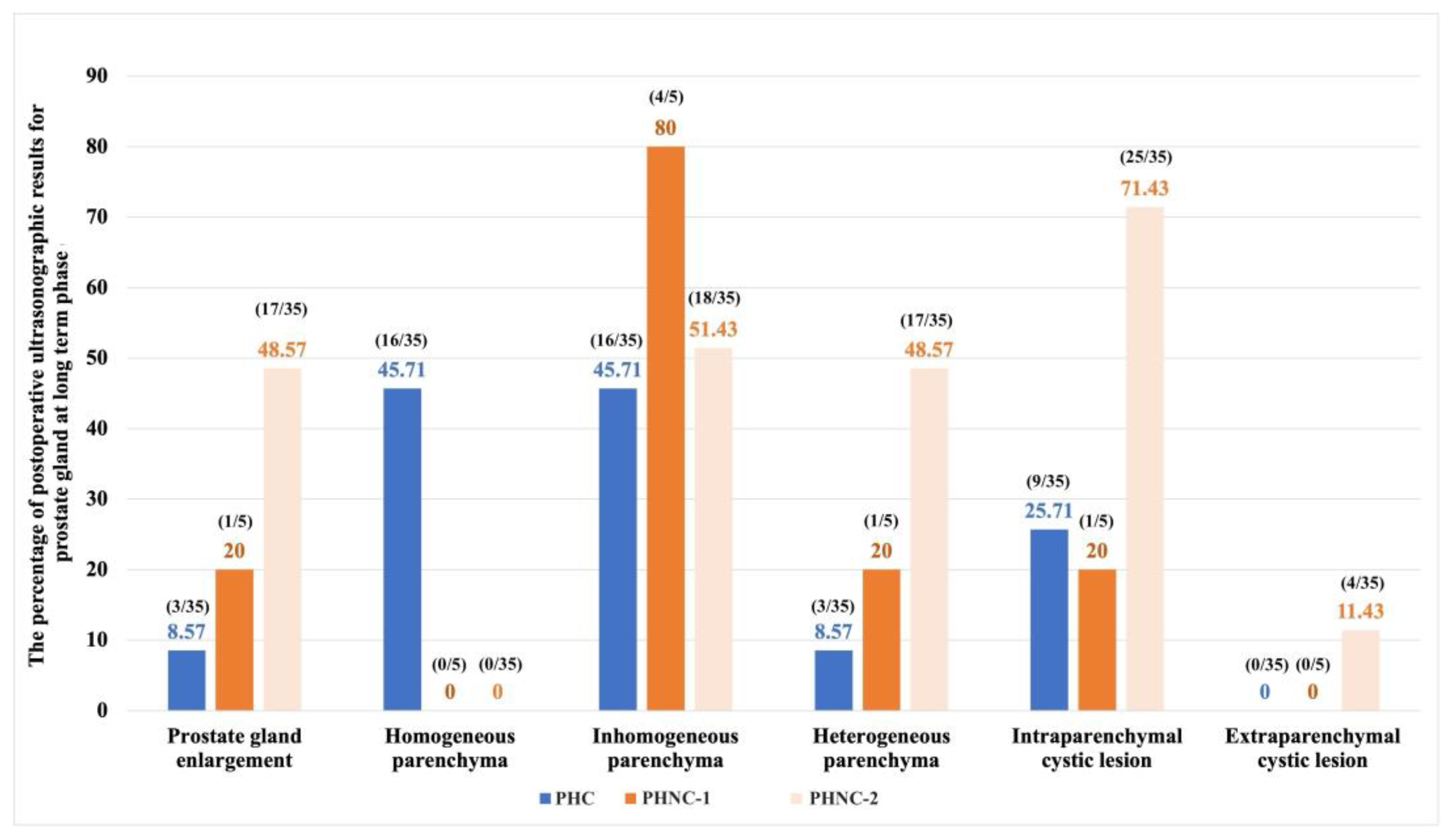

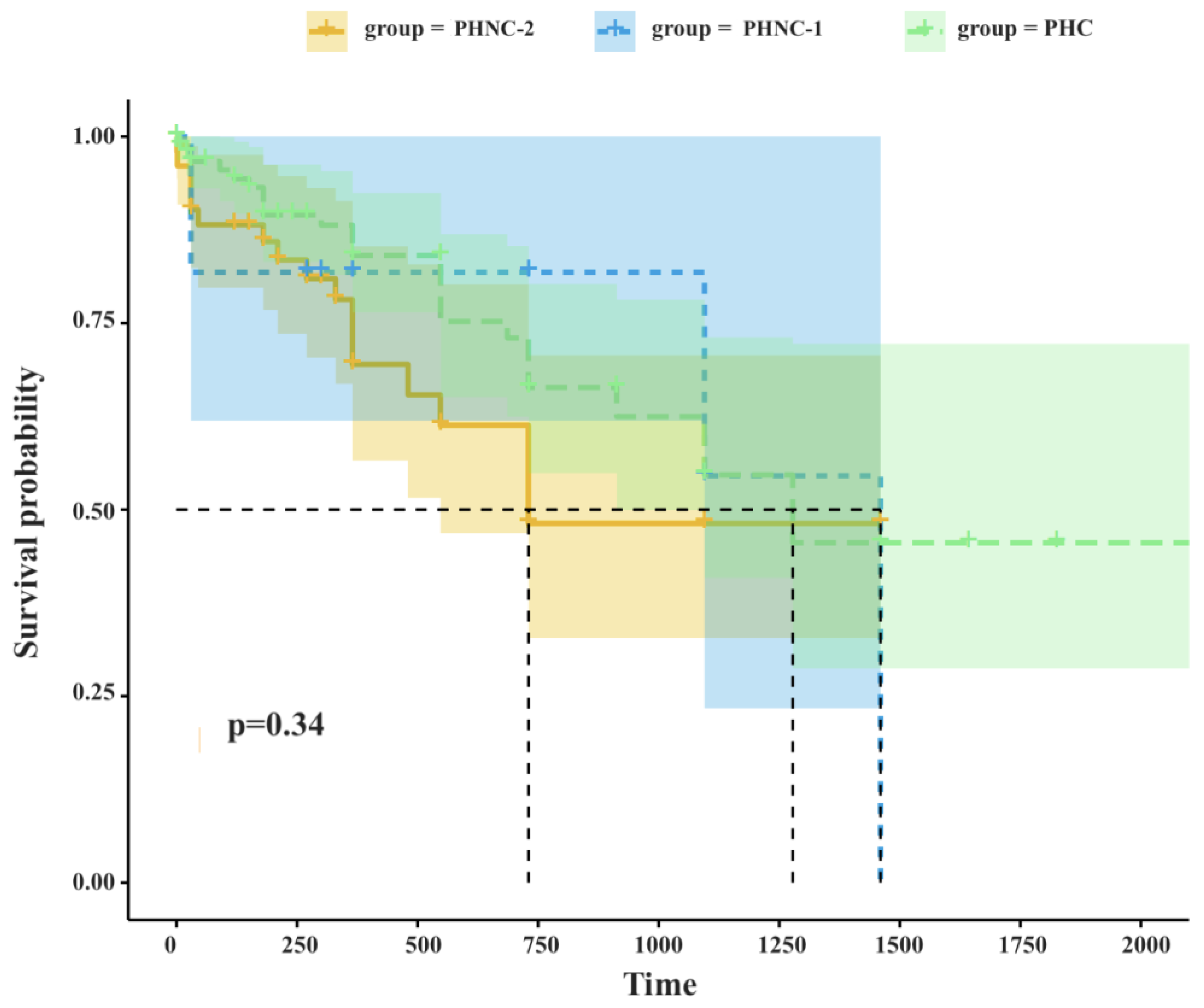

3.3.3. Long-Term Phase (>6 Months to the Last Examination)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPH | Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| PH | Perineal hernia |

| UTIs | Urinary tract infections |

| BW | Body weight |

| GI | Gastrointestinal tract |

| CBC | Complete blood count |

| cm3 | Cubic centimeter |

| UB | Urinary bladder |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| PHC | Castrated group which underwent castration in conjunction with perineal herniorrhaphy |

| PHNC | Non-castrated group which underwent perineal herniorrhaphy only |

| kg | Kilogram |

| cm | Centimeter |

| P/O | Postoperative |

| SS | The sacro-ischial sling method |

| IOMT | The Internal obturator muscle transposition technique |

| FNA | Fine needle aspiration |

| PHNC-1 | PHNC group which castrated within 2 months after perineal herniorrhaphy |

| PHNC-2 | PHNC group which remained intact or castrated 2 months after perineal herniorrhaphy |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| DIC | Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| CT scan | Computerized Tomography Scan |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Fernando Leis-Filho, A., & E. Fonseca-Alves, C.. Anatomy, histology, and physiology of the canine prostate gland. In Veterinary Anatomy and Physiology; IntechOpen: 2018.

- Verma, A.; Singh, R.; Jawre, S.; Khan, A.; Namdev, N.; Vishvakarma, S.; Sinha, A. Prostate disorders in dogs, with a focus on benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): An overview. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husb. 2024, 9, 868–875. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, C.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E.; Laufer-Amorim, R. A review on canine and feline prostate pathology. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 881232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. Canine prostatic disease: A review of anatomy, pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, S.D.; Kamolpatana, K.; Root-Kustritz, M.V.; Johnston, G.R. Prostatic disorders in the dog. Anim Reprod Sci 2000, 60-61, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryman-Tubb, T.; Lothion-Roy, J.H.; Metzler, V.M.; Harris, A.E.; Robinson, B.D.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Jeyapalan, J.N.; James, V.H.; England, G.; Rutland, C.S.; et al. Comparative pathology of dog and human prostate cancer. J Vet Med Sci 2022, 8, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Magno, S.; Pisani, G.; Dondi, F.; Cinti, F.; Morello, E.; Martano, M.; Foglia, A.; Giacobino, D.; Buracco, P. Surgical treatment and outcome of sterile prostatic cysts in dogs. Vet Surg 2021, 50, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruetten, H.; Wehber, M.; Murphy, M.; Cole, C.; Sandhu, S.; Oakes, S.; Bjorling, D.; Waller, K., 3rd; Viviano, K.; Vezina, C. A retrospective review of canine benign prostatic hyperplasia with and without prostatitis. Clin Theriogenology 2021, 13, 360–366. [Google Scholar]

- Polisca, A.; Troisi, A.; Fontaine, E.; Menchetti, L.; Fontbonne, A. A retrospective study of canine prostatic diseases from 2002 to 2009 at the Alfort Veterinary College in France. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, X.; Nizanski, W.; von Heimendahl, A.; Mimouni, P. Diagnosis of common prostatic conditions in dogs: an update. Reprod Domest Anim 2014, 49, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, C.; Foster, R.A.; Grieco, V.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E.; Wood, G.A.; Culp, W.T.N.; Murua Escobar, H.; De Marzo, A.M.; Laufer-Amorim, R. Histopathological terminology standards for the reporting of prostatic epithelial lesions in dogs. J Comp Pathol 2019, 171, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, B.W. Canine Prostate Disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2018, 48, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunto, M.; Ballotta, G.; Zambelli, D. Benign prostatic hyperplasia in the dog. Anim Reprod Sci 2022, 247, 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, C.; Walker, D.; Blazquez, C.A.; Zaghloul, O.; Tappin, S.; Kelly, D. Prostatitis and prostatic abscessation in dogs: retrospective study of 82 cases. Aust Vet J 2022, 100, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, W.B.; Tipler, A.E. Surgical excision and omentalisation of mineralised paraprostatic cysts with concurrent ureteroneocystostomy and perineal herniorrhaphy in a 9-year-old male entire Bearded Collie. Aust Vet J 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, E.M.; Kirby, B.M.; Simpson, J.W.; Munro, E. Surgical management of perineal paraprostatic cysts in three dogs. J Small Anim Pract 2000, 41, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Barstad, R.D. A review of the surgical management of perineal hernias in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018, 54, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjollema, B.E.; Venker-van Haagen, A.J.; van Sluijs, F.J.; Hartman, F.; Goedegebuure, S.A. Electromyography of the pelvic diaphragm and anal sphincter in dogs with perineal hernia. Am J Vet Res 1993, 54, 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hosgood, G.; Hedlund, C.S.; Pechman, R.D.; Dean, P.W. Perineal herniorrhaphy: perioperative data from 100 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1995, 31, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brissot, H.N.; Dupré, G.P.; Bouvy, B.M. Use of laparotomy in a staged approach for resolution of bilateral or complicated perineal hernia in 41 dogs. Vet Surg 2004, 33, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlberg, T.M.; Jokinen, T.S.; Salonen, H.M.; Laitinen-Vapaavuori, O.M.; Molsa, S.H. Exploring the association between canine perineal hernia and neurological, orthopedic, and gastrointestinal diseases. Acta Vet Scand 2022, 64, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, S.; Aronson, L.; Johnston, S.; Tobias, K. Rectum, anus and perineum. In Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal, 2nd ed.; Johnston SJ, T.K., Ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, Missouri, 2017; pp. 1783–1827. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, C.F.; Harvey, C.E. Perineal hernia in the dog. J Small Anim Pract 1973, 14, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaughnessy, M.; Monnet, E. Internal obturator muscle transposition for treatment of perineal hernia in dogs: 34 cases (1998-2012). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015, 246, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambelli, D.; Ballotta, G.; Valentini, S.; Cunto, M. Total Perineal Prostatectomy: A Retrospective Study in Six Dogs. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, K.M.; Crombie, K. Perineal hernia repair in dorsal recumbency in 23 dogs: Description of technique, complications, and outcome. Vet Surg 2022, 51, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobias, K.M.; Johnston, S.A. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal - E-BOOK: 2-Volume Set; Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bernarde, A.; Rochereau, P.; Matres-Lorenzo, L.; Brissot, H. Surgical findings and clinical outcome after bilateral repair of apparently unilateral perineal hernias in dogs. J Small Anim Pract 2018, 59, 734–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, A.M.; Rosner, S.A.; de Assumpcao, T.C.; Stopiglia, A.J.; Matera, J.M. Retrospective study (2009-2014): perineal hernias and related comorbidities in bitches. Top Companion Anim Med 2016, 31, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heishima, T.; Asano, K.; Ishigaki, K.; Yoshida, O.; Sakurai, N.; Terai, K.; Seki, M.; Teshima, K.; Tanaka, S. Perineal herniorrhaphy with pedunculated tunica vaginalis communis in dogs: Description of the technique and clinical case series. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 931088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatch, A.L.; Wallace, M.L.; Carroll, K.A.; Grimes, J.A.; Sutherland, B.J.; Schmiedt, C.W. Dogs neutered prior to perineal herniorrhaphy or that develop postoperative fecal incontinence are at an increased risk for perineal hernia recurrence. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, T.; Jerram, R.M.; Walker, A.M.; Warman, C.G. Surgical management of common canine prostatic conditions. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 2007, 29, 656–658. [Google Scholar]

- Cunto, M.; Mariani, E.; Anicito Guido, E.; Ballotta, G.; Zambelli, D. Clinical approach to prostatic diseases in the dog. Reprod Domest Anim 2019, 54, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamolpatana, K.; Johnston, G.R.; Johnston, S.D. Determination of canine prostatic volume using transabdominal ultrasonography. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2000, 41, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannamwong, N.; Saengklub, N.; Sriphuttathachot, P.; Ponglowhapan, S. Formula derived prostate volume determination of normal healthy intact dogs in comparison to dogs with clinical BPH. Proceeding of the 7th International Symposium on Canine and Feline Reproduction 2012, 226. [Google Scholar]

- Sirinarumitr, K.; Johnston, S.D.; Kustritz, M.V.; Johnston, G.R.; Sarkar, D.K.; Memon, M.A. Effects of finasteride on size of the prostate gland and semen quality in dogs with benign prostatic hypertrophy. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001, 218, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, W.L.; Orsher, R.J.; Larenza-Menzies, M.P.; Popovitch, C.A. Comparison of caudal and pre-scrotal castration for management of perineal hernia in dogs between 2004 and 2014. N Z Vet J 2015, 63, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swieton, N.; Singh, A.; Lopez, D.; Oblak, M.; Hoddinott, K. Retrospective evaluation on the outcome of perineal herniorrhaphy augmented with porcine small intestinal submucosa in dogs and cats. Can Vet J 2020, 61, 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Fossum, T.W. Small Animal Surgery Textbook - E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlberg, T.M.; Salonen, H.M.; Laitinen-Vapaavuori, O.M.; Molsa, S.H. CT imaging of dogs with perineal hernia reveals large prostates with morphological and spatial abnormalities. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2022, 63, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand JG, B.S., Monnet E. Effects of urinary bladder retroflexion and surgical technique on postoperative complication rates and long-term outcome in dogs with perineal hernia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013, 243, 1442-1447. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchav, R.; Feuermann, Y.; Shamay, A.; Ranen, E.; Stein, U.; Johnston, D.E.; Shahar, R. Expression of relaxin receptor LRG7, canine relaxin, and relaxin-like factor in the pelvic diaphragm musculature of dogs with and without perineal hernia. Vet Surg 2005, 34, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haverkamp, K.; Harder, L.K.; Kuhnt, N.S.M.; Lupke, M.; Nolte, I.; Wefstaedt, P. Validation of canine prostate volumetric measurements in computed tomography determined by the slice addition technique using the Amira program. BMC Vet Res 2019, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, J.; Thieman Mankin, K.M.; Parambeth, J.C.; Edwards, J.; Cook, A. Urine-Filled Large Prostatic Cystic Structure in Two Unrelated Male Miniature Dachshunds. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2018, 54, e54606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantziaras, G. Imaging of the male reproductive tract: Not so easy as it looks like. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phongphaew, W.; Kongtia, M.; Kim, K.; Sirinarumitr, K.; Sirinarumitr, T. Association of bacterial isolates and antimicrobial susceptibility between prostatic fluid and urine samples in canine prostatitis with concurrent cystitis. Theriogenology 2021, 173, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.J.; Chung, W.H.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, K.P.; Suh, H.J.; Do, S.H.; Eom, K.D.; Kim, H.Y. Use of canine small intestinal submucosa allograft for treating perineal hernias in two dogs. J Vet Sci 2012, 13, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zedda, M.T.; Bogliolo, L.; Antuofermo, E.; Falchi, L.; Ariu, F.; Burrai, G.P.; Pau, S. Hypoluteoidism in a dog associated with recurrent mammary fibroadenoma stimulated by progestin therapy. Acta Vet. Scand. 2017, 59, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, S.; Wilkens, B.; Radasch, R.M. Use of polypropylene mesh in addition to internal obturator transposition: a review of 59 cases (2000-2004). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2007, 43, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand, J.G.; Bureau, S.; Monnet, E. Effects of urinary bladder retroflexion and surgical technique on postoperative complication rates and long-term outcome in dogs with perineal hernia: 41 cases (2002-2009). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2013, 243, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weese, J.S.; Blondeau, J.; Boothe, D.; Guardabassi, L.G.; Gumley, N.; Papich, M.; Jessen, L.R.; Lappin, M.; Rankin, S.; Westropp, J.L.; et al. International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases (ISCAID) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of bacterial urinary tract infections in dogs and cats. Vet J 2019, 247, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pre-operative clinical signs | PHC % (n=184) | PHNC% (n=131) |

|---|---|---|

|

Urogenital signs - Pollakiuria - Stranguria/ dysuria - Hematuria - Urinary incontinence - Bloody preputial discharge - Testis/ scrotal swelling |

2.71% (n=5) 14.13% (n=26) 4.89% (n=9) 7.60% (n=14) 1.08% (n=2) 1.63% (n=3) |

3.81% (n=5) 32.82% (n=43) 4.58% (n=6) 7.63% (n=10) 0.76% (n=1) 0% (n=0) |

|

Gastrointestinal signs - Anorexia - Vomiting - Diarrhea - Dyschezia - Tenesmus - Constipation - Small or ribbon-like-shaped feces - Hematochezia - Fecal incontinence - Rectal prolapse - Rectal tear |

13.58% (n=25) 14.13% (n=26) 14.67% (n=27) 64.67% (n=119) 52.71% (n=97) 9.23% (n=17) 14.67% (n=27) 10.32% (n=19) 0% (n=0) 1.63% (n=3) 1.08% (n=2) |

17.55% (n=23) 9.16% (n=12) 5.34% (n=7) 72.51% (n=95) 50.38% (n=66) 5.34% (n=7) 6.10% (n=8) 9.92% (n=13) 0.76% (n=1) 0% (n=0) 0.76% (n=1) |

|

Systemic signs - Sepsis - DIC - Azotemia |

0.54% (n=1) 0% (n=0) 18.47% (n=34) |

0% (n=0) 0% (n=0) 21.37% (n=28) |

|

Other - Perineal swelling - Perineal necrosis, severe inflammation - Perineal rupture - Hindlimb lameness |

100% (n=184) 9.23% (n=17) 2.17% (n=4) 1.08% (n=2) |

100 % (n=131) 8.39% (n=11) 0.76% (n=1) 0.76% (n=1) |

| Post-operative outcome | 1-2 weeks | 1-2 months | >6 months | ||||||||

|

PHC % (n/ total) |

PHNC % (n/total) |

PHC % (n/ total) |

PHNC % (n/total) |

PHC % (n/ total) |

PHNC-1 % (n/total) |

PHNC-2 % (n/total) |

|||||

| Urogenital system | |||||||||||

| - Pollakiuria | 0 (0/165) |

0 (0/115) |

0 (0/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Stranguria/ dysuria | 0.60 (1/165) |

0.86 (1/115) |

0 (0/103) |

1.11 (1/90) |

1.33 (1/75) |

14.29 (1/7) |

2.50 (1/40) |

||||

| - Hematuria | 0.60 (1/165) |

0.86 (1/115) |

0 (0/103) |

1.11 (1/90) |

1.33 (1/75) |

0 (0/7) |

2.50 (1/40) |

||||

| - Urinary incontinence | 4.24 (7/165) |

7.82 (9/115) |

1.94 (2/103) |

6.66 (6/90) |

6.66 (5/75) |

14.29 (1/7) |

7.50 (3/40) |

||||

| - Bloody preputial discharge | 0 (0/165) |

0 (0/115) |

0 (0/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Testis / scrotal swelling | 1.21 (2/165) |

1.74 (2/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - UTIs/ cystitis | 64.29 (9/14) |

80 (28/35) |

19.48 (15/77) |

41.98 (34/81) |

31.43 (11/35) |

20 (1/5) |

28.57 (10/35) |

||||

| - Cystic calculi/ sediment | 28.57 (4/14) |

26.67 (8/30) |

12.99 (10/77) |

29.63 (24/81) |

22.86 (8/35) |

40 (2/5) |

34.29 (12/35) |

||||

| - Ureter dilate | 0 (0/14) |

6.67 (2/30) |

0 (0/77) |

1.23 (1/81) |

0 (0/35) |

0 (0/5) |

0 (0/35) |

||||

| - Prostatic urethral dilate | 0 (0/14) |

0 (0/30) |

3.90 (3/77) |

0 (0/81) |

0 (0/35) |

0 (0/5) |

0 (0/35) |

||||

| - Hydronephrosis | 0.60 (1/14) |

0 (0/30) |

1.30 (1/77) |

0 (0/81) |

2.86 (1/35) |

0 (0/5) |

0 (0/35) |

||||

| - Urethral rupture | 0 (0/165) |

0 (0/115) |

0 (0/103) |

1.11 (1/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - UB rupture | 0 (0/165) |

0.86 (1/115) |

0 (0/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| Post-operative outcome | 1-2 weeks | 1-2 months | >6 months | ||||||||

|

PHC % (n/ total) |

PHNC % (n/total) |

PHC % (n/ total) |

PHNC % (n/total) |

PHC % (n/ total) |

PHNC-1 % (n/total) |

PHNC-2 % (n/total) |

|||||

| Gastrointestinal system | |||||||||||

| - Anorexia | 2.42 (4/165) |

2.60 (3/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

2.22 (2/90) |

4 (3/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Vomiting | 3.03 (5/165) |

2.60 (3/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Diarrhea | 3.63 (6/165) |

3.47 (4/115) |

0 (0/103) |

2.22 (2/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

2.12 (1/40) |

||||

| - Dyschezia | 0.60 (1/165) |

4.35 (5/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

1.11 (1/90) |

5.33 (4/75) |

0 (0/7) |

6.38 (3/40) |

||||

| - Tenesmus | 3.03 (5/165) |

6.96 (8/115) |

1.94 (2/103) |

5.56 (5/90) |

4 (3/75) |

0 (0/7) |

6.38 (3/40) |

||||

| - Constipation | 0 (0/165) |

0 (0/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

0 (0/90) |

2.67 (2/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Small or ribbon-like-shaped feces | 0 (0/165) |

0.86 (1/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

2.12 (1/40) |

||||

| - Hematochezia | 1.81 (3/165) |

0.86 (1/115) |

0 (0/103) |

1.11 (1/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Fecal incontinence | 3.63 (6/165) |

2.60 (3/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

4.44 (4/90) |

1.33 (1/75) |

0 (0/7) |

2.12 (1/40) |

||||

| - Rectal prolapse | 1.81 (3/165) |

5.21 (6/115) |

0.97 (1/103) |

0 (0/90) |

1.33 (1/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Rectal tear | 0 (0/165) |

0 (0/115) |

0 (0/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| Systemic signs | |||||||||||

| - Sepsis | 0.60 (1/165) |

0.86 (1/115) |

0 (0/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - DIC | 0.60 (1/165) |

0 (0/115) |

0 (0/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

| - Azotemia | 1.81 (3/165) |

2.60 (3/115) |

4.85 (5/103) |

2.22 (2/90) |

5.33 (4/75) |

0 (0/7) |

4.25 (2/40) |

||||

| - Pancreatitis | 0.60 (1/165) |

1.73 (2/115) |

0 (0/103) |

0 (0/90) |

0 (0/75) |

0 (0/7) |

0 (0/40) |

||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).