1. Introduction

Dyscalculia is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by severe difficulties in numerical cognition, arithmetic reasoning, and mathematical problem-solving, despite adequate intellectual abilities and educational exposure. It is estimated to affect approximately 3-7% of the population, with symptoms ranging from an impaired sense of numerical magnitude to difficulties in understanding arithmetic operations and applying mathematical concepts in daily life [

1].

Based on a cognitive perspective, individuals with dyscalculia often struggle with core numerical processing deficits, including recognizing numerical relationships, estimating quantities, and grasping the concept of numerical magnitude. This impairment affects real-world tasks, such as telling time, handling money, and measuring ingredients while cooking. These difficulties extend beyond the classroom, impacting self-confidence and independence in a society that relies heavily on numerical literacy [

2].

Neurocognitive research has identified specific brain regions associated with dyscalculia, particularly the intraparietal sulcus (IPS), which is crucial for numerical processing [

3]. Neuroimaging studies indicate that children and adults with dyscalculia exhibit reduced activation in the IPS during mathematical tasks, reflecting atypical neural processing of numerical information. Additionally, research highlights the role of working memory and executive functions in mathematical problem-solving, suggesting that interventions should adopt a comprehensive, multi-component approach to learning mathematics [

4].

The consequences of dyscalculia extend to academic, psychological, and career-related domains. Individuals with dyscalculia often experience academic underachievement, leading to low self-esteem and limited career prospects in fields such as science, engineering, finance, and healthcare [

5]. The psychological impact of repeated failure in mathematics can result in math anxiety, frustration, and disengagement from learning, further intensifying the challenges faced by affected individuals [

6].

Mathematical anxiety is a pervasive issue that disproportionately affects students with dyscalculia, creating a negative feedback loop in which fear of failure leads to avoidance behaviours and disengagement from mathematical tasks [

7]. The emotional burden of persistent struggles with mathematics can negatively influence self-perception, confidence, and overall well-being. Addressing dyscalculia through targeted, evidence-based interventions is therefore essential not only for academic success but also for enhancing long-term quality of life [

8].

Traditional interventions for dyscalculia primarily involve structured, repetitive exercises designed to strengthen numerical cognition. However, emerging research highlights the potential of educational robotics and game-based learning as innovative, engaging, and effective approaches [

9]. Educational robotics utilizes programmable robots to facilitate hands-on, experiential learning, promoting spatial reasoning and problem-solving skills [

10]. Simultaneously, game-based learning embeds mathematical concepts within interactive, reward-driven environments, thereby reducing anxiety and fostering persistence [

11]. Preliminary studies indicate that combining these approaches may create a multi-sensory, adaptive learning experience tailored to individual needs [

12].

Existing research on dyscalculia interventions has predominantly focused on cognitive and behavioural approaches, aiming to strengthen numerical processing skills through repetitive drills and explicit instruction. However, recent studies emphasize the importance of integrating technology-enhanced learning methods, particularly educational robotics and game-based learning, to create a more engaging and effective learning experience [

13].

Understanding dyscalculia requires a multidimensional perspective that integrates cognitive theories of numerical processing with practical, evidence-based interventions. Several theoretical models help explain the cognitive underpinnings of dyscalculia, each shedding light on different aspects of numerical cognition and mathematical difficulties. One of the most influential theories is the Defective Number Module Hypothesis [

14] , which suggests that dyscalculia stems from a fundamental impairment in the Approximate Number System (ANS) - the innate ability to estimate and represent numerical magnitudes. This deficit affects a child's ability to intuitively grasp quantities and numerical relationships, making even basic arithmetic challenging.

Another key framework is the Triple-Code Model [

15] which proposes that numerical cognition operates through three distinct representational systems: verbal (spoken and written number words), visual (Arabic numerals), and analogue magnitude representation (non-symbolic quantity estimation). Dyscalculia, according to this model, arises from weaknesses in one or more of these systems, leading to difficulties in understanding, manipulating, or expressing numerical concepts. Additionally, the Working Memory Deficit Hypothesis [

16] highlights the critical role of cognitive load in mathematical reasoning. Given that arithmetic problem-solving relies on working memory to process and store numerical information, deficits in this domain may contribute to the difficulties observed in individuals with dyscalculia. Challenges in retaining multi-step calculations or switching between different strategies may significantly hinder mathematical learning and performance. Recent research has explored how technology-enhanced learning approaches, particularly educational robotics and game-based learning, can support students with dyscalculia by fostering engagement, motivation, and numerical cognition.

Educational Robotics has shown promise in helping students develop spatial reasoning and problem-solving skills, both of which are crucial for mathematical understanding. Studies indicate that hands-on, experiential learning with programmable robots enhances numerical cognition by offering concrete, interactive experiences with mathematical concepts. Moreover, robotics-based interventions have been particularly effective in reducing math anxiety and increasing engagement among students with dyscalculia [

17,

18].

Similarly, game-based learning provides an interactive and adaptive environment where students can practice mathematical concepts through real-time feedback and dynamic difficulty adjustments. Research suggests that digital games not only reinforce numerical understanding but also promote persistence and motivation, key factors in overcoming learning difficulties in mathematics [

19].

Interestingly, a combined approach - integrating educational robotics with game-based learning - has shown early promise in enhancing mathematical understanding, engagement, and self-efficacy. While preliminary findings support this integration as a holistic, technology-enhanced intervention for dyscalculic students, further large-scale, longitudinal studies are needed to assess its long-term effectiveness.

Despite the promising potential of these technology-driven strategies, research on their combined effectiveness in dyscalculia interventions remains limited. This study seeks to address this gap by:

Evaluating the impact of a technology-enhanced intervention that merges educational robotics and game-based learning on numerical cognition and arithmetic performance.

Investigating student engagement and motivation in interactive, technology-enhanced learning environments.

Assessing the feasibility of integrating these strategies into formal educational settings to ensure accessibility and long-term sustainability.

By tackling these objectives, this research aims to contribute valuable insights to the growing body of literature on technology-enhanced learning for students with mathematical learning disabilities. Ultimately, it seeks to inform more inclusive and effective pedagogical interventions for dyscalculic learners, bridging the gap between cognitive theories and classroom practice [

20].

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Setting

The participants were 73 students among 10 and 13 years old at the beginning of the study. The classes involved were three from lower secondary school:

Class 1 was composed of 26 students, including one student with high-functioning autism, two certified with specific learning disabilities (SLD), one certified with special educational needs (SEN) (borderline between the normal intellectual functioning and mild intellectual impairments and the remaining students were typically developed children.

Class 2 was composed of 25 students, including one student with mild cognitive delay, two certified with SEN (borderline intellectual quotient), four certified with SLD (one severe), and the remaining students with normal abilities.

Class 3 was composed of 22 students, including two students (mild cognitive delay, one also with selective mutism), two certified with SLD, and the remaining students were typically developed children.

The study was carried out within school context, with the cooperation of their support teacher. The academic activities (see below) were selected upon concordance between parents, support teachers and participants. The families and the schools staff considered the rehabilitative program highly desirable. In fact, a formal consent was signed by the legal representatives and the study was approved by a local ethical scientific committee.

2.2. Selection of Stimuli and Academic Activities

The selection of stimuli and academic activities was carried out based on the latest empirical evidence regarding interventions for dyscalculia [

21]. The selected stimuli included numerical and arithmetic tasks, adapted to progressive difficulty levels, to assess the impact of the intervention on students' cognitive and mathematical skills. The academic activities included exercises in numerical recognition, basic arithmetic operations, and mathematical problems contextualized in daily life situations.

2.3. Technology and Response

The intervention utilized an approach based on educational robotics and game-based learning, incorporating both structured lessons and exploratory activities. Participants engaged with digital platforms and programmable educational robots, specifically designed to reinforce numerical cognition and arithmetic reasoning. These tools provided adaptive challenges that adjusted in complexity based on individual performance, ensuring a personalized learning trajectory for each student.

Throughout the intervention, students received immediate, multimodal feedback, combining visual, auditory, and haptic cues to reinforce correct responses and guide error correction. Real-time monitoring was implemented using embedded analytics within the digital platforms, allowing researchers and educators to track response accuracy, reaction times, and engagement levels. This continuous assessment enabled the identification of persistent difficulties, such as misconceptions in numerical magnitude representation or difficulties in procedural calculations.

Furthermore, the intervention incorporated peer collaboration elements, where students worked in pairs or small groups to complete problem-solving tasks using the robots. This aspect aimed to enhance social learning, resilience, and motivation, particularly beneficial for students with learning difficulties. Sessions were structured into progressive modules, beginning with fundamental mathematical concepts and advancing toward more complex applications, ensuring a scaffolded learning experience tailored to individual needs.

2.4. Sessions and Data Collection

Sessions were conducted twice a week over a 12-week period. Each session lasted approximately 45 minutes and was divided into three phases: (1) introduction and explanation of activities, (2) execution of activities with the support of educational technology, and (3) discussion and consolidation of acquired knowledge. Data collection was carried out through pre- and post-intervention tests, video recordings of sessions, and self-assessment questionnaires completed by the students.

The data collection for this study was conducted through a combination of observational analysis, practical exercises, and student performance assessments. The primary tools included SAM Labs and Ozobot Evo, which were integrated into mathematics lessons to evaluate their impact on student learning, engagement, and problem-solving abilities.

The study was carried out in a secondary school setting during the 2023/2024 academic year. Participants included students from a first-year middle school class, with a diverse range of learning needs, including students with Dyscalculia and SEN.

Data were collected using the following methods:

Pre- and post-tests to assess mathematical competency improvements.

Student observation during activities, focusing on engagement and problem-solving strategies.

Teacher feedback through structured interviews regarding student progress.

Performance analysis of students' ability to calculate and visualize perimeters using SAM Labs.

The dependent variables in this study are the learning outcomes and cognitive engagement of students participating in the robotics-enhanced mathematics curriculum. These include:

Mathematical Performance – Measured through accuracy in calculating perimeters and other geometric properties before and after the intervention.

Problem-Solving Skills – Evaluated based on students’ ability to program and apply SAM Labs and Ozobot Evo in solving geometric problems.

Engagement and Motivation – Assessed through student participation levels, interaction with the technological tools, and responses in post-activity feedback sessions.

Error Reduction in Calculations – Comparing student errors in manual calculations versus technology-assisted calculations to determine the impact of digital tools.

Collaboration and Interaction – Observing how students work in teams to complete activities, reflecting the role of robotics in fostering cooperative learning.

The results from these variables will contribute to understanding how educational robotics can enhance mathematical learning, particularly for students with learning difficulties such as dyscalculia.

2.5. Materials and Procedures

The materials used included:

Ozobot EVO: a small robot capable of moving on physical and digital surfaces, following coloured lines. Only about 3 cm in size, the bot can recognize over 1000 instructions in the form of coloured lines drawn, for example, with a marker on paper or displayed on a tablet; it can avoid obstacles, change direction, and much more.

SAM Labs Platform: an educational technology ecosystem that combines hardware and software to facilitate interactive, hands-on learning experiences. The platform includes wireless, Bluetooth-enabled blocks (such as sensors, motors, and lights) that can be connected through an intuitive drag-and-drop programming interface. This system enables students to explore mathematical and computational concepts through real-world applications, fostering problem-solving, logical reasoning, and algorithmic thinking. By engaging with SAM Labs, students develop foundational STEM skills in an accessible and adaptable environment that supports personalized learning paths.

2.6. Experimental Conditions

To ensure a balanced and methodologically sound comparison, the three participating classes were evenly distributed across the two groups, maintaining an equivalent number of students in each condition. This stratified allocation accounted for factors such as age, baseline mathematical performance, and cognitive profiles, thereby minimizing potential confounding variables and ensuring the internal validity of the study.

The first group followed a traditional mathematics curriculum, where lessons were conducted using conventional teaching methods, such as textbook exercises, teacher-led explanations, and written assignments. This group served as the control, providing a baseline for evaluating the impact of the intervention.

The second group, in contrast, engaged with a curriculum enriched through the integration of educational robotics. These students participated in hands-on activities using programmable robots designed to reinforce numerical concepts, arithmetic operations, and problem-solving strategies. The robotics-based curriculum incorporated game-based learning elements, interactive challenges, and real-world problem-solving scenarios to enhance engagement and motivation.

Both groups received instruction over the same period, ensuring consistency in exposure to mathematical content. The intervention was structured to allow for direct comparisons between traditional and robotics-enhanced learning environments, focusing on key performance indicators such as numerical accuracy, problem-solving efficiency, and overall engagement. Pre- and post-intervention assessments were conducted to measure improvements in mathematical skills, processing speed, and student motivation. Additionally, qualitative observations and student feedback were collected to better understand their experiences and attitudes toward mathematics in both conditions.

The experiment was structured into different phases to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention. By ensuring the equitable distribution of the three classes between the two experimental conditions, the study design facilitated a robust and unbiased assessment of how educational robotics influences mathematical learning outcomes compared to traditional instructional methods.

2.6.1. First Baseline

During this initial phase, students' numerical and arithmetic skills were assessed using standardized tests, which included both computational fluency tasks and problem-solving exercises. Additionally, motivational assessments were administered to evaluate students' attitudes towards mathematics, their levels of math-related anxiety, and their self-efficacy in numerical tasks. These tests provided critical insights into the affective factors influencing mathematical performance and engagement. No technological support was provided at this stage to establish a clear baseline for comparison.

2.6.2. First Intervention

In this phase, students were introduced to the educational robotics and game-based learning program. The intervention was designed to enhance engagement and comprehension through interactive activities that incorporated visual, auditory, and kinaesthetic learning modalities. Their interactions with the technology were systematically observed, and performance data were collected to evaluate potential improvements in their mathematical skills.

2.6.3. Second Baseline

Following the first intervention, students underwent a second evaluation baseline phase, which was identical to the initial baseline assessment, to determine whether the previously observed improvements were sustained or if any regressions occurred. This phase also aimed to analyse retention rates by assessing students' ability to apply the skills learned during the first intervention to new mathematical tasks.

2.6.4. Second Intervention

During this phase, an increased level of complexity was introduced. Students were presented with more advanced mathematical problems that required logical reasoning and abstract thinking. For example, rather than simple arithmetic operations, students were challenged with multi-step word problems involving real-world applications, such as budgeting a shopping list or calculating distances and travel times. These tasks required them to integrate different mathematical concepts and develop strategic problem-solving approaches.

Additionally, greater autonomy in using educational technology was encouraged to assess students’ ability to navigate problem-solving scenarios independently. For instance, students were given open-ended challenges where they had to program an educational robot to follow a sequence of commands that simulated a mathematical function, such as computing an optimal path based on numerical inputs. This hands-on interaction reinforced abstract mathematical principles through tangible applications.

Adaptive learning elements were incorporated, allowing the technology to tailor difficulty levels based on each student's progress. For example, if a student demonstrated proficiency in fraction operations, the system dynamically increased the complexity by introducing problems involving ratio and proportion. Conversely, if difficulties were detected, the program provided scaffolding through step-by-step hints and visual representations to reinforce conceptual understanding before progressing further.

2.6.5. Third Intervention

In this phase, students continued to use technological tools, but with an emphasis on the generalization of acquired mathematical skills in real-life contexts. Tasks involved practical applications, such as financial literacy exercises, measurement activities, and data interpretation. The aim was to bridge the gap between academic learning and real-world mathematical problem-solving.

2.6.6. Maintenance and Generalization

This phase assessed students' ability to retain acquired skills over time and apply them in various contexts, including other academic subjects and daily life situations. Retention was evaluated through delayed post-tests, administered several weeks after the intervention, to measure the long-term stability of numerical and problem-solving skills. These assessments aimed to determine whether students could independently recall and apply learned mathematical concepts without additional support, providing critical insights into the effectiveness and sustainability of the intervention.

Beyond formal testing, qualitative feedback was gathered to explore the perceived transferability of these skills. Through structured interviews and focus group discussions, students were encouraged to share how their engagement with educational robotics influenced their confidence and ability to approach mathematical tasks in different settings. Teachers and parents also provided valuable observations on whether students demonstrated increased problem-solving independence, logical reasoning, and numerical fluency in everyday activities, such as managing personal finances, estimating measurements, or interpreting graphical data.

Additionally, self-assessment surveys were implemented to foster metacognitive awareness and encourage students to reflect on their own learning process. These surveys included prompts requiring students to evaluate their progress, identify areas where they still faced challenges, and articulate strategies they found helpful during problem-solving. The goal was to empower students to become more aware of their cognitive strengths and weaknesses while promoting a sense of ownership over their learning journey. This reflective practice not only supported skill consolidation but also provided educators with deeper insights into individual learning trajectories, informing potential refinements in instructional approaches.

4. Discussion

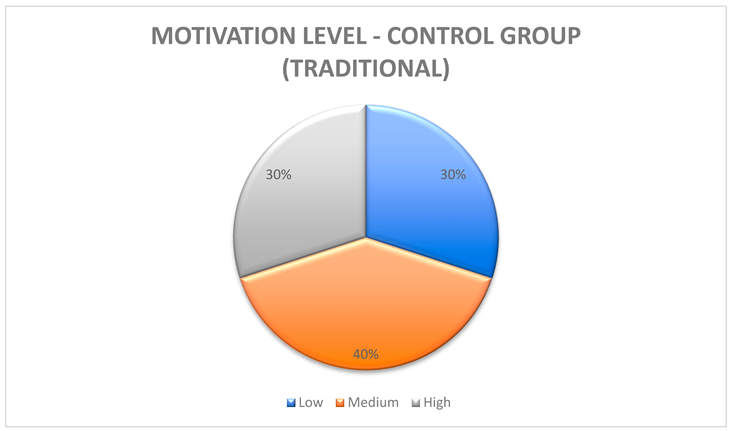

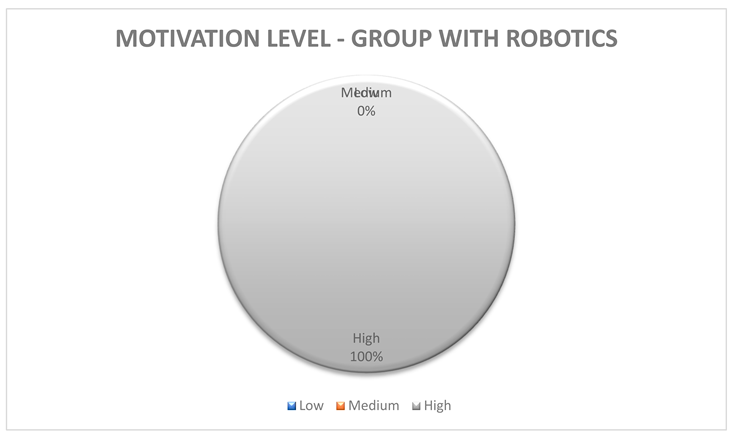

The results evidenced that the group that participated in lessons supported by robotics showed a significant improvement in numerical skills, with a 75% increase from the baseline, compared to 50% for the traditional group. Additionally, motivation levels increased significantly, reaching 85% compared to 60% for the traditional group. These data highlight not only the effectiveness of robotics in teaching mathematics but also its potential to make learning more stimulating and inclusive. Educational robotics stands out for its ability to create interactive and personalized learning environments. Using programmable robots, students can explore complex mathematical concepts in a practical and engaging way. This approach overcomes traditional teaching barriers, promoting self-efficacy and a sense of competence among students with specific learning difficulties. Beyond academic improvements, the use of robotics has a positive impact on students' emotional spheres. Technological tools transform learning into a positive experience, helping to reduce math-related anxiety and improve self-esteem. These benefits also extend to teachers, who find in robotics a valuable support to diversify teaching methodologies and make lessons more dynamic [

22]. The data indicate a clear advantage for students engaged in robotics-based learning. In addition to improving numerical skills, the approach positively impacted students' self-efficacy and emotional engagement with mathematics. The robotics-enhanced group reported higher confidence levels in tackling mathematical problems and displayed a greater willingness to participate in learning activities. Beyond academic performance, the integration of robotics helped reduce math-related anxiety and fostered a more positive learning experience [

23]. The interactive nature of the intervention allowed students to explore problem-solving in a non-threatening, exploratory manner, reinforcing perseverance and self-confidence. Furthermore, teachers reported that educational robotics provided a valuable tool to diversify instructional methods, making lessons more dynamic and adaptive to individual learning needs [

24]. These findings underscore the necessity of incorporating innovative educational technologies to support students with learning difficulties, ultimately promoting more inclusive and effective pedagogical practices.

Table 1 clearly shows the effectiveness of educational robotics in improving numerical skills and student motivation compared to the traditional approach.

The methodology used in the study included cooperative learning and tutoring approaches to maximize teaching effectiveness. Students were divided into small heterogeneous groups, where they worked together to solve mathematical problems using educational robots. This approach allowed students to learn from each other, improving their skills through collaboration and mutual support. The findings of this study provide compelling empirical evidence supporting the role of educational robotics as an effective intervention for students with dyscalculia. The significant improvement in numerical skills and motivation levels observed in the experimental group underscored the importance of integrating technology-based learning strategies into traditional curricula. These results align with prior research indicating that multimodal, interactive learning environments can enhance mathematical cognition and engagement, particularly for students with learning difficulties [

25]. One of the key advantages of educational robotics was its ability to make abstract mathematical concepts more tangible and interactive. By engaging students in hands-on, experiential learning experiences, robotics fostered deeper cognitive processing and conceptual understanding. This approach leveraged embodied cognition principles, which suggested that learning was more effective when it involved physical interaction with the environment. As students manipulated robotic elements to solve mathematical problems, they developed spatial reasoning, numerical fluency, and procedural accuracy, all of which were critical for mathematical competence. This approach not only benefited students with dyscalculia but also supported a broader range of learners, including those with diverse cognitive profiles and learning styles [

26].

Beyond academic improvements, the use of robotics had a profound impact on students' emotional well-being. The integration of technological tools transformed mathematics learning into a positive and engaging experience, helping to reduce math-related anxiety and improve self-esteem. These findings are consistent with previous studies suggesting that technology-enhanced learning environments can foster resilience and shift students' perceptions of their mathematical abilities. Importantly, these benefits were not limited to students alone - teachers also experienced positive outcomes, as robotics provided a valuable resource for diversifying instructional methodologies and making lessons more dynamic and interactive. The ability to tailor learning experiences using adaptive robotics-based interventions empowered educators to effectively address the heterogeneous needs of students with specific learning disorders [

27].

Additionally, the results highlighted the psychosocial benefits of robotics-enhanced education. The observed reduction in math-related anxiety and increase in student confidence suggested that robotics can contribute to a more inclusive and psychologically supportive learning environment. The interactive and exploratory nature of robotics-based learning allowed students to take ownership of their educational experiences, promoting a sense of autonomy, competence, and intrinsic motivation [

28]. This aspect was particularly relevant in addressing the affective barriers often associated with mathematical learning difficulties, where negative emotions and self-doubt could hinder academic progress [

29]. The interactive and exploratory nature of robotics-based learning enabled students to take ownership of their educational experiences and promoted a sense of autonomy and competence.

Moreover, the collaborative nature of robotics-based learning enhanced peer-mediated learning and social skill development. Unlike traditional instructional methods that emphasize individual performance, robotics-based activities often required students to work in teams, negotiate solutions, and communicate their reasoning processes [

30]. These interactions encouraged the development of teamwork, problem-solving discussions, and knowledge-sharing strategies, which could be particularly beneficial for students with learning difficulties. The creation of a supportive peer-learning environment supported motivation, improved resilience, and promoted a sense of belonging within the classroom [

31]. From a clinical perspective, these collaborative dynamics could contribute to the development of social and cognitive skills in students with learning difficulties, potentially mitigating the negative impact of specific learning disorders on academic and social integration. Future research should further explore how structured peer-learning interventions can be optimized to enhance executive functioning, emotional regulation, and long-term academic performance in students with neurodevelopmental disorders [

32].

However, despite these promising findings, some challenges remained. Implementing educational robotics requires adequate teacher training, access to technological resources, and pedagogical adaptations. Educators should be equipped with the necessary technical and instructional competencies to seamlessly integrate robotics into their teaching practices. Additionally, disparities in school funding, technological infrastructure, and institutional readiness may hinder the widespread adoption of these innovations. Addressing these barriers requires strategic policy interventions, professional development programs, and cross-sector collaborations to ensure equitable access to robotics-based education [

33].

Future research should explore the long-term cognitive and behavioural effects of robotics interventions and examine their scalability across diverse educational settings. Further studies might investigate how different types of educational robots, programming tools, and gamified elements influence learning trajectories for students with dyscalculia. Additionally, longitudinal research is necessary to assess whether the observed improvements in numerical skills, motivation, and self-efficacy are sustained over time. Integrating neuroscientific approaches - such as neuroimaging and eye-tracking - could provide deeper insights into the neural mechanisms underlying robotics-based mathematical learning. Furthermore, AI-driven adaptive learning models could be explored to enhance personalization, automate feedback mechanisms, and optimize instructional design. By examining these factors, future research can contribute to the development of evidence-based, scalable, and technologically enhanced pedagogical models that support students with dyscalculia and beyond [

34].

5. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

To evaluate the acceptability and perceived effectiveness of the intervention, qualitative data were collected through structured interviews with students, teachers, and parents. This phase represented a descriptive and initial work, aimed at gathering preliminary insights into the intervention’s impact. The structured interviews were designed to explore multiple dimensions, including students' emotional engagement, motivation, and perception of the usefulness of the educational technologies used. Specific attention was given to identifying factors that facilitated learning, as well as potential barriers that could hinder the effectiveness of robotics-based instruction. Teachers were asked to provide feedback on the feasibility of implementing the intervention within their regular curriculum, while parents shared their observations on any changes in their children's confidence and attitude towards mathematics. To complement these qualitative insights, a Likert-scale questionnaire was administered to quantify stakeholders' satisfaction levels. This questionnaire included items evaluating ease of use, perceived usefulness, and overall enjoyment of the educational robotics experience. The results provided a structured way to measure subjective experiences and identify areas requiring refinement, such as improving technological accessibility, optimizing task difficulty, or incorporating additional scaffolding strategies for students with more pronounced difficulties. Future research will focus on the expansion of the sample and more in-depth analysis, allowing for a broader generalization of findings and a more detailed examination of individual differences in response to the intervention. Expanding the sample size will enable researchers to investigate whether factors such as age, cognitive profiles, or prior exposure to technology influence the effectiveness of robotics-based learning. Moreover, further studies will incorporate longitudinal designs to assess the durability of improvements over time, exploring whether students retain their acquired numerical skills and whether their attitudes toward mathematics remain positively influenced in the long run. By integrating these elements, future research will contribute to the development of evidence-based, scalable models for enhancing mathematical learning through technology-driven approaches.

6. Conclusions

This study contributed to the growing body of research advocating for the use of educational robotics in mathematics education. By demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing numerical skills, boosting motivation, and reducing anxiety, educational robotics emerged as a valuable tool for fostering inclusive and engaging learning environments. The integration of robotics-based learning provided students with opportunities to develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills, essential competencies for the modern digital era [

35].

As educational institutions continue to explore innovative pedagogical strategies, integrating robotics into mainstream curricula could represent a significant step toward making mathematics education more accessible and effective for all students. However, for this approach to reach its full potential, sustained investment is required in teacher training, technological infrastructure, and curriculum development. Ensuring that educators have the necessary skills to incorporate robotics effectively is crucial for the long-term success of such interventions [

36].

Further research is needed to explore the longitudinal effects of robotics-based interventions on mathematical learning, as well as their applicability to diverse educational settings. Studies should also examine how robotics can be integrated with other emerging educational technologies, such as artificial intelligence and adaptive learning systems, to create even more personalized learning experiences [

37].

The combination of educational robotics with AI-driven solutions could further enhance the personalization and scalability of interventions, reducing the cognitive load on educators and support staff. AI-based adaptive learning systems can analyse student performance in real-time, providing individualized feedback and dynamically adjusting the difficulty of exercises based on each learner’s progress [

38]. This integration could be particularly beneficial for students with learning disabilities, allowing for more responsive and targeted support while optimizing the efficiency of intervention programs [

39].

Additionally, future research should investigate the cognitive mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of robotics-based learning in mathematics. Understanding how hands-on interaction with robots enhances conceptual understanding, memory retention, and cognitive flexibility could provide valuable insights into optimizing instructional design. Comparative studies across different age groups and educational levels would also be beneficial in determining the most effective implementation strategies [

40]. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaborations between educators, psychologists, and technology experts could lead to the development of more tailored interventions that address the specific needs of students with learning difficulties, such as dyscalculia [

41].

Since this study is a pilot, its findings serve as a preliminary step toward more extensive investigations. Future research should include larger and more diverse targeted populations to collect more generalizable and reliable conclusions regarding the effectiveness of robotics-based interventions. Expanding the sample size and conducting studies across different educational contexts will help the results’ validation and refine the implementation strategies for broader applicability. Pilot studies play a crucial role in paving the way for large-scale research, highlighting key variables and methodological considerations that should be addressed in subsequent investigations [

42].

By fostering a learning environment that is interactive, student-centred, and adaptable to individual needs, educational robotics holds promise as a transformative tool in mathematics education. The findings of this study highlight the need for continuous innovation in teaching methodologies, ensuring that all students, regardless of their learning challenges, can develop strong mathematical foundations and achieve academic success.