1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and acute respiratory failure are among the serious clinical conditions associated with high mortality rates in intensive care units (ICUs). Electrolyte imbalances are significant variables that may influence mortality in this patient group. Sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) levels are considered independent prognostic markers in critical illness processes [

1,

2].

Hypochloremia has been independently associated with mortality in critically ill patients. For instance, a study conducted in ICU patients reported that hypochloremia significantly increased ICU mortality [

1]. Similarly, in patients with acute kidney injury, chloride levels demonstrated a nonlinear relationship with mortality, with lower chloride levels being linked to an increased risk of death [

2].

The prognostic impact of sodium is also crucial in this context. Both hyponatremia (low sodium levels) and hypernatremia (high sodium levels) have been identified as markers that increase mortality risk in various critical illness scenarios. In general, medical patients presenting to the emergency department, both extremes of sodium levels, have been shown to be associated with higher mortality rates [

3].

Studies conducted in ICU settings on COPD patients have specifically evaluated the impact of electrolyte imbalances on mortality. For example, research on COPD patients undergoing mechanical ventilation due to acute respiratory failure has demonstrated a strong association between low sodium levels and high mortality rates [

4]. Additionally, the prognostic significance of chloride has been investigated in conditions such as heart failure, where low chloride levels were found to increase mortality risk, whereas sodium alone did not fully explain this relationship [

5].

Electrolyte imbalances play a crucial role not only in predicting mortality but also in guiding treatment processes. A study examining the use of chloride-rich solutions in ICU patients explored the impact of chloride level changes on patient outcomes [

6]. Moreover, metabolic imbalances have been highlighted as key contributors to mortality in adult cystic fibrosis and respiratory failure patients [

7].

The existing literature underscores the independent effects of electrolyte imbalances, particularly serum chloride and sodium levels, on mortality in critically ill COPD patients. A recent study reported an "L-shaped" relationship between serum chloride levels and 90-day and 365-day mortality in critically ill COPD patients, with mortality decreasing as chloride levels increased up to 102 mmol/L [

8]. Similarly, during COPD exacerbations, sodium and potassium imbalances are frequently observed, significantly worsening patient outcomes [

9].

In this context, investigating the impact of sodium and chloride imbalances on mortality in ICU patients with COPD and respiratory failure will contribute significantly to the existing literature and help clarify how these parameters can be utilised in clinical decision-making. In our study, we aimed to explore the relationship between sodium and chloride levels and all-cause mortality in a broad patient population with respiratory failure, while also assessing their associations with disease severity and organ failures due to infections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Study Design

Before commencing the study, compliance with ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki was declared, and ethical approval was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital (approval number: 2024-BÇEK/228, date: 12/02/2025). Following this approval, all patients diagnosed with type 1 and type 2 respiratory failure and monitored in the secondary-level pulmonary intensive care units of Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital between January 2022 and January 2024 were retrospectively screened. Before utilising patient data in this retrospective study (excluding radiological images and photographs), the presence of signed and complete informed consent forms in patient records was verified. Patients who had not signed the consent form or who refused to share their clinical data were excluded from the study.

A total of 1211 patient records with type 1 and type 2 respiratory failure from January 2022 to January 2024 were reviewed. Of these, 46 patients were excluded due to incomplete or unsigned informed consent forms. Additionally, 26 patients who died within the first 24 hours of ICU admission and 22 patients who were transferred to another clinic within the first 24 hours were also excluded. As a result, 1109 patients were included in the study.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Patients younger than 18 years.

Patients who died within the first 24 hours after ICU admission or were transferred to another clinic.

Patients with incomplete or unsigned informed consent forms.

Demographic characteristics such as age and gender were recorded for all included patients. In addition, blood samples obtained during the first days of ICU admission were analysed for sodium and chloride levels, as well as other electrolytes, including magnesium, calcium, and potassium. Venous blood gas parameters, including pH, partial carbon dioxide pressure (pCO₂), base excess (BE), and bicarbonate (HCO₃), were recorded. Disease severity scores, including the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) and Sequential (or Sepsis-related) Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores, were also documented. Additional parameters such as ICU length of stay, survival duration, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, albumin levels, and the need for non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) were recorded.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 27. Categorical data were presented as n (%), while ordinal and non-normally distributed numerical data were expressed as median and minimum-maximum values. For normally distributed numerical data, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were reported.

For categorical variables:

✓ If all cells contained more than 5 patients, the Chi-square test was applied.

✓ If at least one cell contained fewer than 5 patients, the Fisher’s exact test was used.

For numerical variables:

The effect sizes of significantly different means in normally distributed numerical variables were reported as Cohen’s d values. Normality was evaluated through descriptive statistics, including Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, skewness-kurtosis values, histograms, and outlier distributions.

For comparisons involving more than two categorical groups:

✓ If the numerical variable followed a normal distribution, one-way ANOVA was used.

✓ If the numerical variable did not follow a normal distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was applied.

Kaplan-Meier analysis was used for survival analysis, while Cox regression analysis was performed to determine the hazard ratio (HR) for mortality risk. A 95% confidence interval (CI) was applied in all statistical analyses, and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Among the patients included in the study, 692 (62.4%) were male, and 417 (37.6%) were female. The median age of all patients was 71 years (22-99). The median age was 73 years (22-96) in females and 68 years (24-99) in males. The median APACHE II score was 15 (range: 3-34) for all patients, with a median of 15 (5-34) in females and 15 (3-34) in males. The median SOFA score was 1 (range: 1-9) for all patients, 2 (1-7) in females, and 1 (1-9) in males.

Among the patients diagnosed with respiratory failure, 858 (77.4%) had type 2 respiratory failure, while 251 (22.6%) had type 1 respiratory failure. A total of 738 patients (66.5%) had a COPD diagnosis, whereas 371 (33.5%) did not. Non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) was applied to 740 patients (66.7%), while 367 (33.1%) did not receive NIV.

At the end of ICU follow-up, 85 patients (7.7%) died (exitus) during their ICU stay. A total of 745 patients (67.2%) were discharged, while 150 patients (13.5%) were transferred to the pulmonary disease clinic (wards), and 129 patients (11.6%) were transferred from the secondary-level ICU to a tertiary-level ICU for further management.

When analysing the relationship between electrolyte levels and all-cause ICU mortality, no significant differences were found in the median values of sodium, chloride, or magnesium between patients who survived and those who did not. However, potassium and calcium levels were significantly lower in patients who died in the ICU compared to survivors. The effect size for potassium was calculated as Cohen’s d = 0.33 (95% CI [0.11, 0.55]), indicating a small to moderate effect size. Similarly, calcium levels were significantly lower in the ICU mortality group (

Table 1).

Sodium, chloride, and magnesium electrolytes did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, these electrolytes were ranked from the lowest to the highest values within the patient population. They were then divided into quartiles, with the lowest 25% of values classified as Q1 (0-25%), followed by Q2 (25-50%), Q3 (50-75%), and Q4 (75-100%). Each quartile was considered a subgroup, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox regression analysis were performed separately for sodium, chloride, and magnesium to assess ICU mortality across these quartiles. Additionally, statistical comparisons were made to determine whether there were significant differences in mortality presence between the quartile groups of these electrolytes.

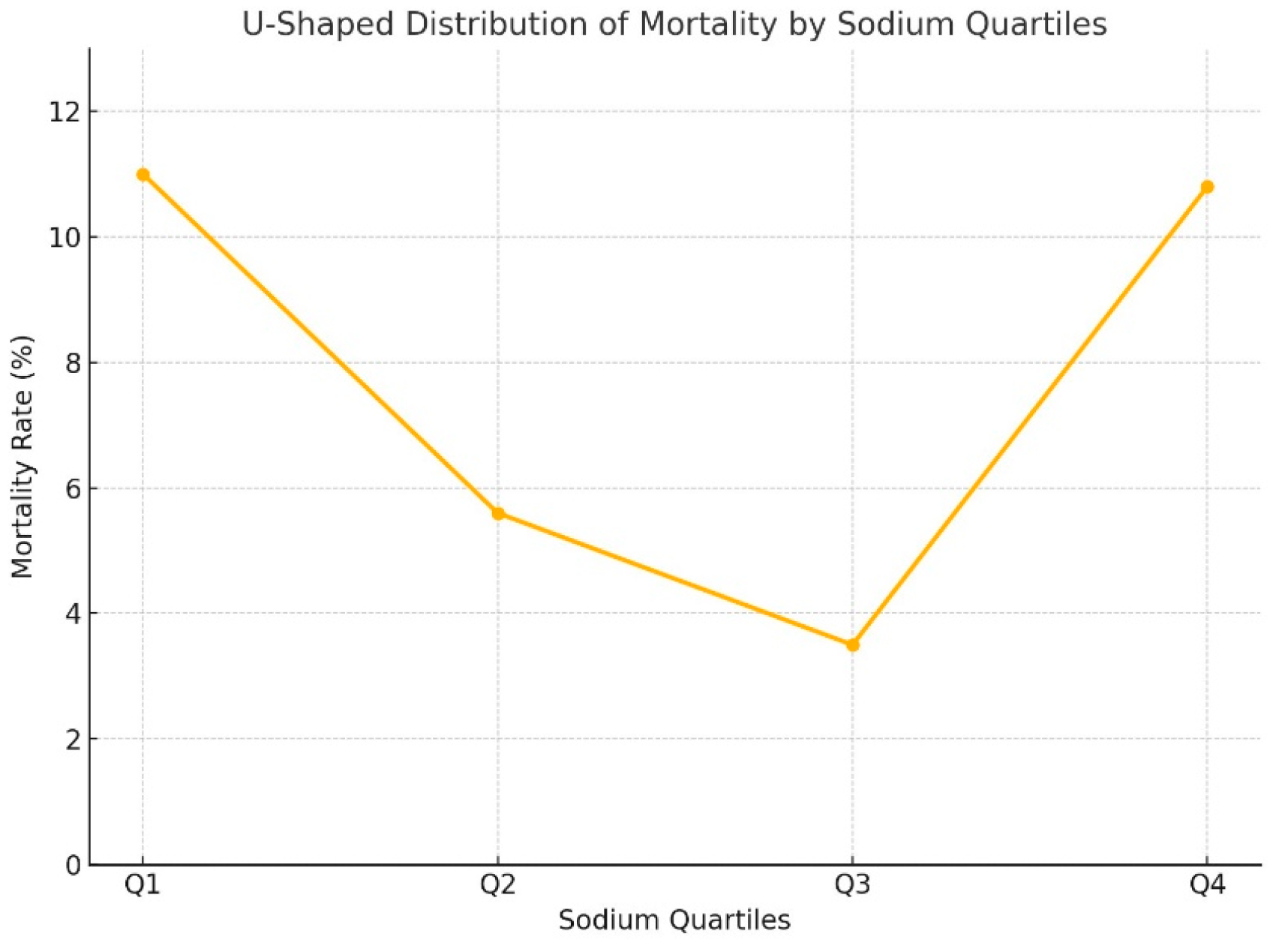

While no significant differences were found between the quartiles for magnesium and chloride in terms of mortality, sodium levels in the Q1 and Q4 groups were significantly associated with higher mortality compared to Q2 and Q3 (p<0.001) (

Table 2). In other words, the relationship between sodium levels and mortality in our patient population followed a "U-shaped" pattern (

Figure 1).

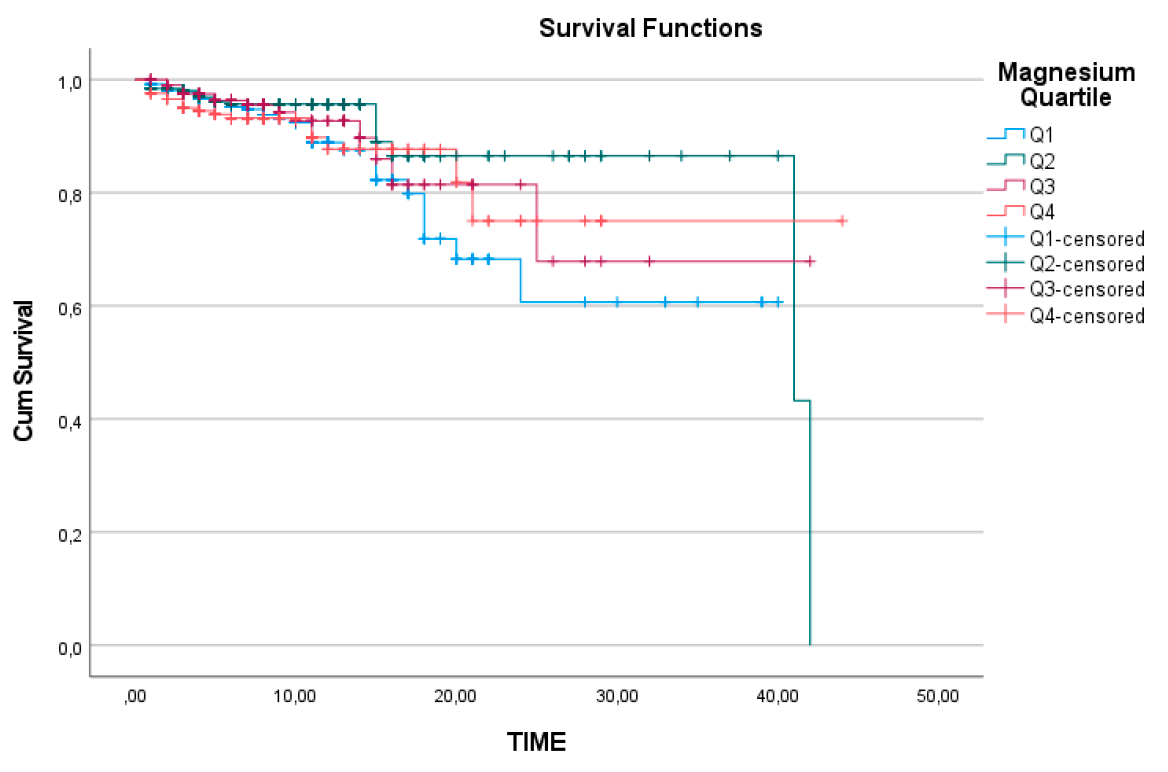

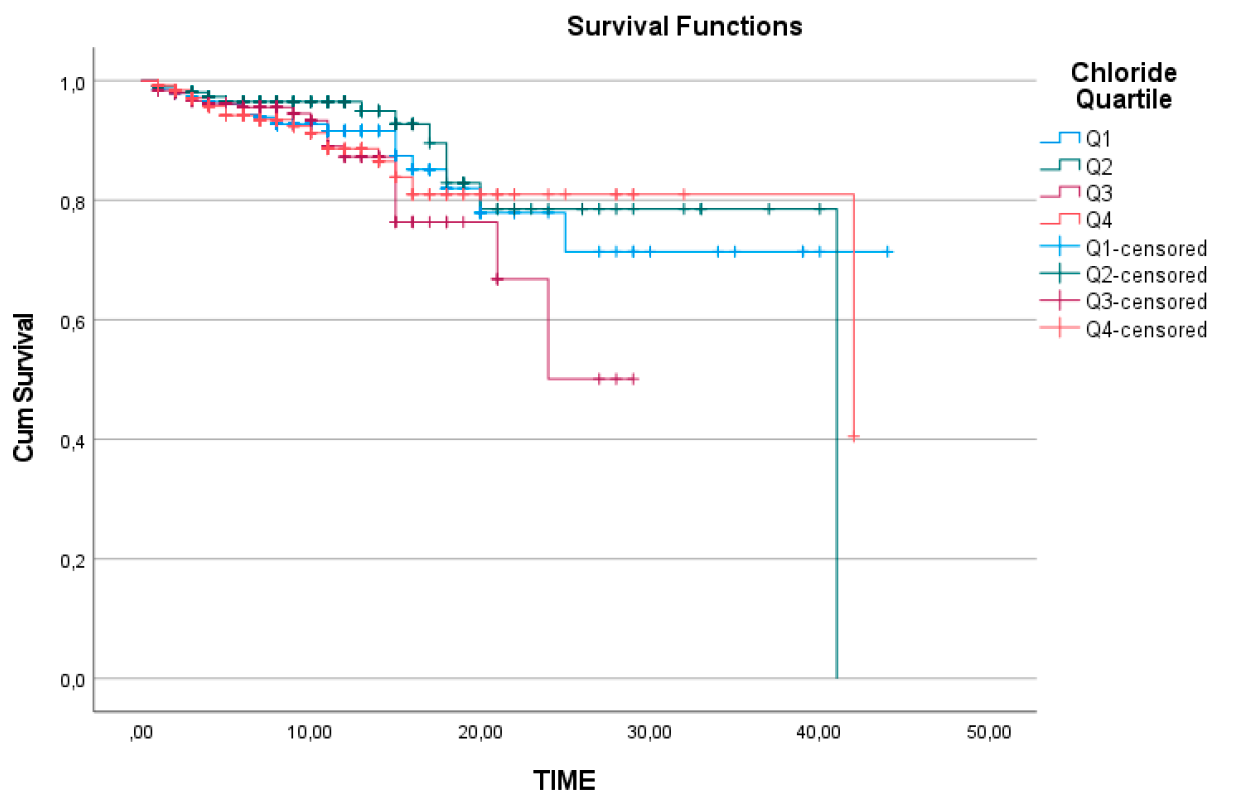

When analysing the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the quartile subgroups of sodium, chloride, and magnesium separately, the survival analysis for magnesium was found to be statistically insignificant, with a log-rank value of 0.259 (

Figure 2). Similarly, chloride levels did not show a significant relationship with survival, with a log-rank value of 0.320 (

Figure 3).

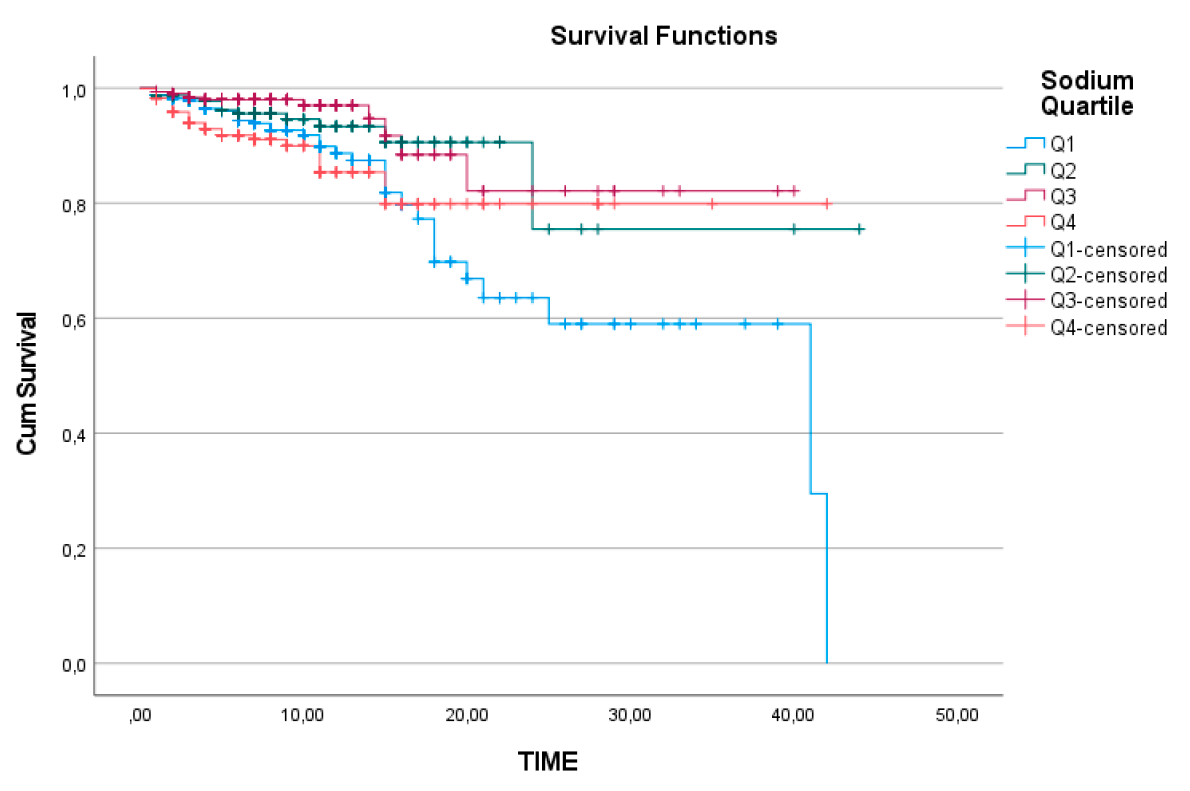

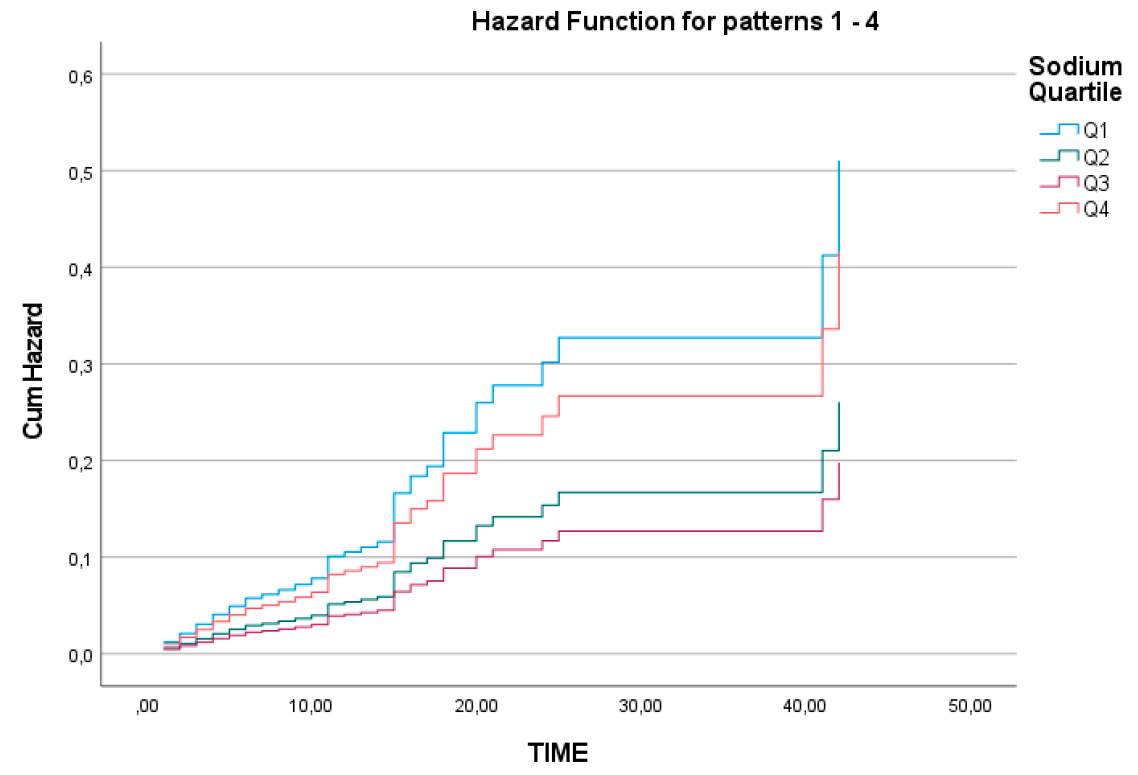

However, for sodium levels, survival analysis between the quartiles revealed that the cumulative survival rate over time was significantly lower in the Q1 group compared to the other subgroups (log-rank=0.002) (

Figure 4). In the Cox regression analysis for ICU mortality, which included adjustments for APACHE II and SOFA scores, the model was found to be statistically significant (p<0.001) (

Table 3).

The cumulative hazard ratio graph for sodium quartiles is presented in

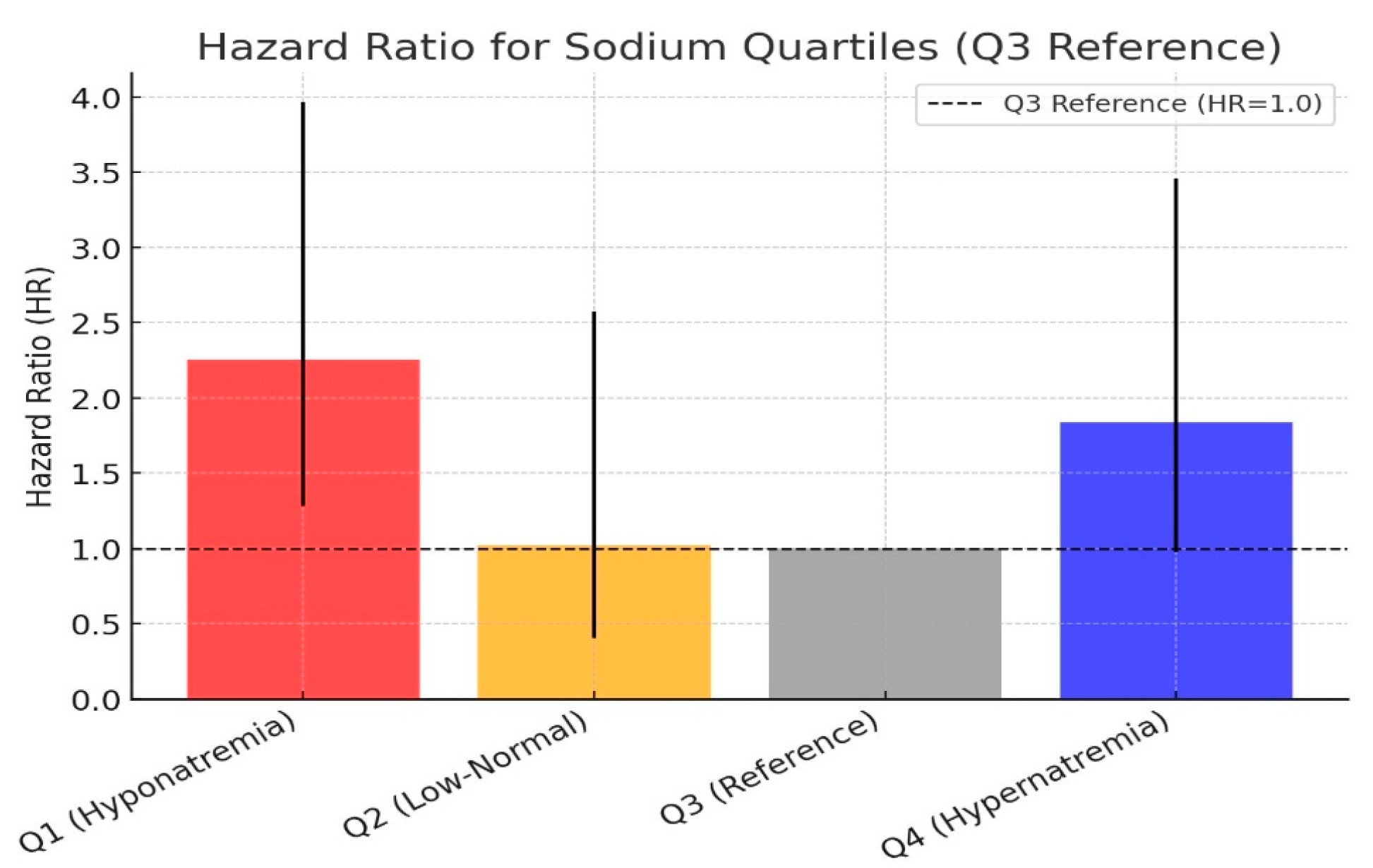

Figure 5. Using the Q3 quartile (139-142 mEq/L) as the reference group, the hazard ratio for Q2 was calculated as 1.02, which was not statistically significant. However, the mortality risk in the Q1 group was approximately 2.2 times higher than in the Q3 group (p=0.005). In the Q4 group, the mortality risk was approximately 1.8 times higher, but the result remained on the borderline of statistical significance (p=0.06). The hazard ratio comparison of the sodium quartile groups is shown in

Figure 6.

Since potassium and calcium electrolytes, along with sodium quartiles, emerged as significant factors in ICU mortality, we further analysed other variables statistically to understand how sodium quartiles might influence mortality. For variables following a normal distribution, one-way ANOVA was used, while for non-normally distributed variables, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was applied for comparisons between groups.

In the Q4 group, albumin and potassium levels were significantly lower compared to the other quartiles (p=0.003 and p<0.001, respectively). When examining arterial blood gas parameters, pCO₂ levels were significantly lower in Q1 and higher in Q4 compared to Q2 and Q3 (p<0.001). Similarly, bicarbonate levels were lower in Q1 and higher in Q4 compared to Q2 and Q3 (p<0.001).

BUN levels were also significantly higher in the Q4 group compared to the other three groups (p=0.003). Base excess values were lower in Q1, indicating metabolic acidosis, and higher in Q4 compared to Q2 and Q3 (p<0.001). While no significant differences were found in APACHE II scores among the sodium quartiles, SOFA scores were significantly higher in the Q4 group compared to the other three groups (p=0.001).

Another striking finding was that the Q4 sodium group had significantly older patients compared to the other sodium quartiles (p<0.001). When evaluating the need for non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) among sodium quartiles, the Q1 group had a significantly lower requirement for NIV compared to the other groups (p<0.001).

4. Discussion

In our study, when we reviewed all electrolyte levels measured during the ICU stay of patients diagnosed with respiratory failure, we found that patients with lower potassium and calcium levels had higher mortality rates. A study conducted in 2023 on 104 patients with COPD exacerbation reported that hypokalaemia was a risk factor for mortality. The same study also identified hyponatremia as a mortality risk factor [

10]. Initially, our findings were interpreted as consistent with the literature.

A study conducted in a surgical ICU identified hypocalcemia as a risk factor for respiratory failure; however, it did not specify the impact of hypocalcemia on mortality in respiratory failure patients. In our study, we determined that patients with low calcium levels in the respiratory failure group had higher mortality rates. This finding may indicate the presence of additional metabolic comorbidities in this patient population [

11].

At first glance, sodium, chloride, and magnesium appeared to be insignificant in terms of mortality. However, considering that both high and low levels of these electrolytes might be clinically relevant, we performed statistical analyses by categorising them into quartiles. For sodium, we obtained striking results—both high and low sodium levels were associated with all-cause ICU mortality.

A similar relationship has been previously reported for chloride levels in COPD patients, where chloride levels were linked to 90-day and 365-day all-cause mortality. In a Cox regression analysis using 102 mmol/L as a reference point, the hazard ratio for hypochloremic levels increased up to 3, decreased below 1 at slightly higher chloride levels, and then rose again beyond 102 mmol/L, forming an "L-shaped" hazard ratio graph rather than a linear correlation [

12]. In our study, sodium followed a "U-shaped" hazard ratio curve, with the hyponatremic side of the "U" being more extended and showing higher hazard ratios.

Thongprayoon et al. examined sodium levels at hospital discharge and found that both hyponatremia and hypernatremia were associated with one-year mortality risk. Their study also described a "U-shaped" relationship between sodium and mortality [

13]. Interestingly, a study on cardiovascular diseases demonstrated a similar "U-shaped" relationship, not with serum sodium levels but with sodium intake, indicating poor health outcomes [

14].

To account for the possibility that certain conditions specific to respiratory failure patients might increase mortality and falsely attribute this effect to sodium quartiles, we compared sodium quartiles based on APACHE II and SOFA scores. In statistical analyses, we found notable findings for the hypernatremic Q4 group. This group had higher partial pCO₂ levels, BUN levels, and SOFA scores and consisted of older patients compared to other groups. However, for the Q1 group, the only significant finding was low pH, while pCO₂ levels were significantly lower, indicating metabolic acidosis. Moreover, despite the increased mortality risk in the sodium Q1 group, the lower need for NIV compared to other groups emerged as a striking finding. In the literature, the need for mechanical ventilation has been associated with increased mortality in patients admitted to the ICU with type 1 respiratory failure and monitored with a diagnosis of acute idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis exacerbation [

15]. Considering this information, the fact that we identified a lower attributable mortality risk factor in hyponatremic patients with respiratory failure supports the notion that hyponatremia is an independent prognostic factor.

A study investigating independent risk factors for hyponatremia in COPD patients identified pneumonia, hypomagnesemia, and metabolic acidosis as closely related to hyponatremia [

16]. Additionally, numerous studies in the literature have reported that hyponatremia serves as a poor prognostic indicator in pediatric patients with lower respiratory tract infections [

17,

18,

19]. Hyponatremia is also frequently observed in lung malignancies, particularly in small-cell lung cancer and, to a lesser extent, in non-small-cell lung cancer, where it presents as a paraneoplastic syndrome and is considered a poor prognostic marker [

20,

21].

As seen in various pulmonary pathologies, hyponatremia frequently occurs and is associated with worse disease outcomes. In our study, we found that patients with the lowest sodium levels had approximately 2.2 times higher mortality rates compared to those with normal sodium levels. Although the hypernatremic group also exhibited a borderline significant increase in mortality risk, these patients had multiple additional risk factors that could contribute to mortality. Increased SOFA scores indicated sepsis, while elevated renal function markers suggested acute kidney injury, a well-known predictor of mortality and morbidity. Furthermore, the hypernatremic group consisted of older patients, further contributing to their poor outcomes.

These findings suggest that rather than hypernatremia itself being the direct cause of increased mortality, it may be a consequence of underlying clinical conditions such as hypovolemic hypernatremia, prerenal acute kidney injury, and infections. In contrast, hyponatremia has diverse and complex aetiologies, all of which can serve as mortality predictors. However, persistent hypernatremia should not be overlooked, as it has been associated with prolonged ICU stay, increased ICU mortality, and higher post-discharge mortality [22].

4.1. Study Limitations

In this study, we evaluated the impact of electrolyte levels on all-cause ICU mortality in patients with respiratory failure. However, ICU physicians are well aware that ICU mortality can result from a wide range of factors. In some cases, acute coronary syndrome or cerebrovascular events, which may develop independently of the patient’s primary clinical condition, can also contribute to mortality in ICU patients. Large prospective studies that comprehensively investigate the causes of mortality would help address this major limitation of our study.

Additionally, the term “respiratory failure” describes a broad clinical condition rather than a specific disease group. More specific studies focusing on individual diseases could provide more valuable contributions to the literature.

5. Conclusion

The importance of serum electrolyte levels in the ICU is well recognised by physicians. However, electrolyte imbalances are so frequently encountered in ICU settings that electrolyte and fluid replacement therapies have become a routine part of daily practice for ICU physicians. Similar to the phenomenon of “ICU alarm fatigue” in response to invasive mechanical ventilator alarms, clinicians may become desensitised to electrolyte imbalances, leading to replacement therapies that are prescribed almost automatically without much consideration.

In many cases, ICU physicians do not reflect on the prognostic implications of these imbalances or hesitate to order additional diagnostic tests for differential diagnosis. However, electrolyte imbalances remain one of the most common challenges ICU patients face, regardless of their reason for admission. Therefore, we believe that each electrolyte should be assessed individually to effectively predict disease prognosis and guide appropriate treatment interventions.

Financial Support

No financial support was received from any individual or institution during any stage of this study.

Consent for publication

This study has not been previously published in another journal and is not currently under review for publication elsewhere. It has not been presented at any scientific congress or conference. Additionally, all authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and have provided their consent for publication.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical norms of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital under the protocol number 2024-BÇEK/228, dated 12/02/2025.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ji, Y.; Li, L. Lower serum chloride concentrations are associated with increased risk of mortality in critically ill cirrhotic patients: an analysis of the MIMIC-III database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zhou, S.; An, S. Lower serum chloride concentrations are associated with an increased risk of death in ICU patients with acute kidney injury: an analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Minerva Anestesiol. 2023, 89, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, B.; Bennett, K.; O'Riordan, D.; Silke, B. Serum sodium as a risk factor for in-hospital mortality in acute unselected general medical patients. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 2008, 102, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añón, J.M.; de Lorenzo, A.G.; Zarazaga, A.; Gómez-Tello, V.; Garrido, G. Mechanical ventilation of patients on long-term oxygen therapy with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prognosis and cost-utility analysis. Intensiv. Care Med. 1999, 25, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, R.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z. Serum chloride as a novel marker for adding prognostic information of mortality in chronic heart failure. Clin. Chim. Acta 2018, 483, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Regenmortel, N.; Verbrugghe, W.; Wyngaert, T.V.D.; Jorens, P.G. Impact of chloride and strong ion difference on ICU and hospital mortality in a mixed intensive care population. Ann. Intensiv. Care 2016, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; Wilson, J.W.; Kotsimbos, T.C.; Naughton, M.T. Metabolic Alkalosis Contributes to Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure in Adult Cystic Fibrosis*. Chest 2003, 124, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, W. L-shaped association between serum chloride levels with 90-day and 365-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with COPD: a retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.K.; Ali, Y.; Islm, M.S.U.; Arif, K.M.; Hawlader, M.A.R.; Quader, M.R.; Saha, P. Pattern of Serum Electrolytes Imbalance among Patients with Acute Exacerbation of COPD Admitted in a Tertiary Level Hospital. Faridpur Med Coll. J. 2020, 15, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Jain, M.; Sharma, A.; Khippal, N. Electrolyte disturbances in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at SMS Medical College, Jaipur2023, 31–33. Global Journal for Research Analysis 2023, 12, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hossary, Z.I.; Eldin, S.M.S.; Matar, H.H.; Askar, I.A.-H. Risk Factors of Hypocalcemic Patients at Surgical Intensive Care Unit of Zagazig University Hospitals. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2021, 85, 3753–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, W. L-shaped association between serum chloride levels with 90-day and 365-day all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with COPD: a retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thongprayoon, C.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Petnak, T.; Ghamrawi, R.; Thirunavukkarasu, S.; Chewcharat, A.; Bathini, T.; Vallabhajosyula, S.; Kashani, K.B. The prognostic importance of serum sodium levels at hospital discharge and one-year mortality among hospitalized patients. Int. J. Clin. Pr. 2020, 74, e13581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graudal, N. The Data Show a U-Shaped Association of Sodium Intake With Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 28, 424–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ari, M.; Ozyurek, B.A.; Yildiz, M.; Ozdemir, T.; Hosgun, D.; Ozdemirel, T.S.; Ensarioglu, K.; Erdogdu, M.H.; Doganay, G.E.; Doganci, M.; et al. Mean Platelet Volume-to-Platelet Count Ratio (MPR) in Acute Exacerbations of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Novel Biomarker for ICU Mortality. Medicina 2025, 61, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Du, F.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Xiong, W.; Wang, Q.; et al. Risk factors for hyponatremia in acute exacerbation chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD): a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobeih, A.A.; Elfiky, O.A.E.; Elalim, M.A.A.; Zakaria, R.M. Role of Hyponatremia in Prediction of Outcome in Children with Severe Lower Respiratory Tract Infections. Benha Med J. 2025, 42, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkmenoglu, Y.; Kacar, A.; Bezen, D.; Kırar, H.; Ozdemir, E.M.; Irdem, A.; Petmezci, M.T.; Dursun, H. Study on the relationship between respiratory scores and hyponatremia in children with bronchiolitis. Asian J. Med Sci. 2021, 12, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, C.; Sharma, V.K.; Singhal, S.; Jangid, R.K.; Laxminath, T.K. Risk Factors of Hyponatremia in Children with Lower Respiratory Tract Infection (LRTI). J. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 8, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandfeld-Paulsen, B.; Aggerholm-Pedersen, N.; Winther-Larsen, A. Hyponatremia in lung cancer: Incidence and prognostic value in a Danish population-based cohort study. Lung Cancer 2021, 153, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chand, R.; Chand, R.; Goldfarb, D.S. Hypernatremia in the intensive care unit. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2021, 31, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).