Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

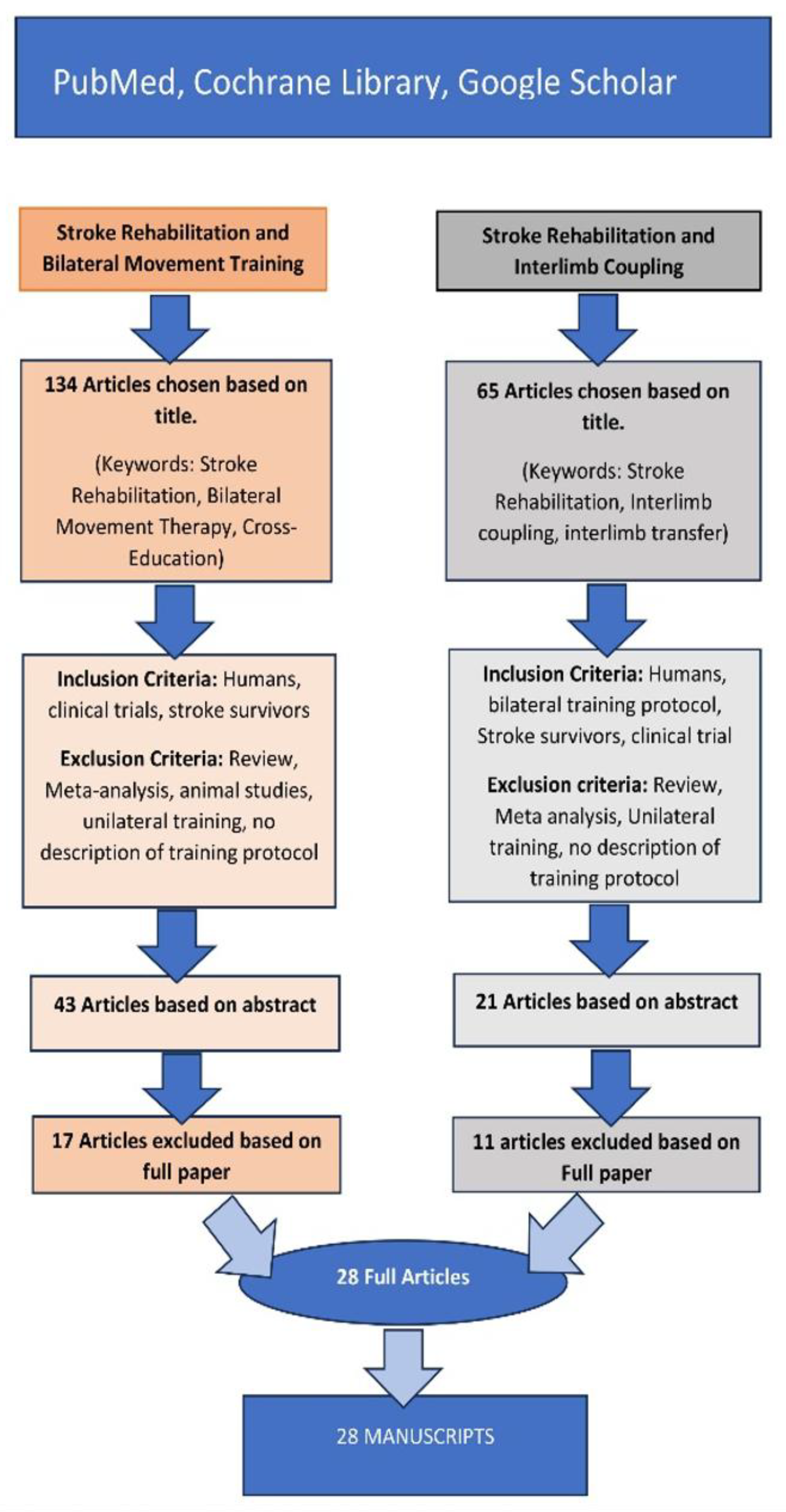

2. Method

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Bilateral Movement Training

3.1.1. Neurophysiological Processes Underpinning Bilateral Movement Training

| Intervention Type & Authors | Participants(Sex/Number/Age) | Measurement(s) | Effect on Stroke Condition | Neurophysiological, Interlimb Coupling, and Transfer Effects * | No. of Potential Facilitating Neurophysiological Mech. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. BILATERAL ARM TRAINING | |||||

| Bruyneel, et al. [71] | n/a-15 poststroke 17 healthy volunteers-n/a | CMSA/Levin Scale/Ashworth/Semmes-Weinstein/Box and Blocks | Bilateral pushing with gradual efforts induces impaired postural strategies and coordination between limbs in individuals after a stroke. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 | 7 |

| Dhakate, D., & Bhattad, R. [72] | n/a-40 post-stroke subjects-45–65 | FIM (Functional Independence Measure) and FMA UE (Fugl-Meyer et al.) | Bilateral Arm Training proved more effective than the Conventional Training program in improving affected upper extremity motor function. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 | 7 |

| Duff, et al. [73] | M/F, 20 post-stroke/20 healthy controls | Adult Assisting Hand Assessment (Ad-AHA Stroke) and UE Fugl-Meyer (UEFM) | Algorithm and sensor data analyses distinguished task types within and between groups and predicted clinical scores. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 | 8 |

| Han, K. J., & Kim, J. Y. [29] | n/a, 30 post-stroke subjects, n/a | FMA UE/ Box and Blocks/ MBI (Modified Barthel Index | In both the experimental and control groups, the FMA, BBT, and MBI scores were significantly higher after the intervention than before the intervention (p < 0.05). The changes in the FMA, BBT, and MBI scores were more significant in the experimental group than in the control group (p < 0.05). | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 | 7 |

| Itkonen, M., et al. [74] | M/F, 11 post-stroke subjects, 52–90 |

Surface EMG measurements | The paretic arms of the patients were more strongly affected by the task conditions compared with the non-paretic arms. These results suggest that in-phase motion may activate neural circuits that trigger recovery. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 | 7 |

| Kim, N., et al. [75] | n/a, 13 hemiparetic stroke patients and 12 healthy participants), n/a | EMG data | The upper extremity muscle activities of stroke patients during bimanual tasks varied between the paretic and non-paretic sides. Interestingly, the non-paretic side muscle activities also differed from regular participants. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 | 7 |

| Kumagai, M., et al. [76] | M/F, 24 subjects, n/a | NHPT, Purdue Pegboard task, Box and Blocks test, FMA UE | Alternating bilateral training may augment training effects and improve upper-limb motor function in patients with left hemiparesis. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 | 7 |

| Lee, M. J., et al. [38] | M/F, 15 pos stroke, 15 healthy, n/a | FMA UE, Box and Blocks test, MBI | Bilateral arm training and general occupational therapy might be more effective than alone for improving upper limb function and ADL performance. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 | 7 |

| Meng, G., et al. [77] | M/F, 128 subjects | FMA UE and Action research Reach Test Secondary: Neurophysiological improvement TMS | Hand-arm intensive bilateral training significantly improved motor functional and neuro-physiological outcomes in patients with acute stroke. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 | 7 |

| Kaupp, C., et al. [24] | M/F, 19 subjects, 57–87 y/o | MAS, Chedoke, Monofilaments sensory discrimination, Berg Balance Test | Results show significant changes in function and neurophysiological integrity. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 13, 14 and 15 | 9 |

| II. BILATERAL ARM TRAINING AND SENSORY ENHANCEMENT | |||||

| Lin, C.H, et al. [78] | M/F, 33 subjects, mean age = 55.1 ± 10.5, | BI, FMA UE, WMFT, MAS | Computer-aided interlimb force coupling training improves the motor recovery of a paretic hand. It facilitates motor control and enhances functional performance in the paretic upper extremity of people with chronic stroke. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 11 | 9 |

| Rodrigues, L. C., et al. [79] | M/F, 26 subjects, n/a | The primary outcome measure was unilateral and bilateral UL activity according to the Test d’Évaluation des Membres Supérieurs de Personnes Âgées (TEMPA). | The total TEMPA score showed the main effect of time. Significant improvement was found for bilateral but not unilateral tasks. Both groups showed gains after training, with no differences between them. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 | 7 |

| Song, G. B. [80]. | M/F, 40 subjects, mean age 51.15 ± 14.81 years, | Box and Block test (BBT), Jebsen Taylor test (JBT), and Modified Barthel Index (MBI) | Upper limb function and the ability to perform activities of daily living improved significantly in both groups. Although there were significant differences between the groups, the task-oriented group showed more remarkable improvement in upper limb function and activities of daily living. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 17 | 10 |

| Van Delden, A. L. E. Q, et al. [81] | M/F, 60 subjects, n/a | Potentiometer, smoothness, and harmony mean amplitude and bimanual coordination measurements. | The coupling between both hands was not significantly higher after bilateral than unilateral training and control treatment. BATRAC group showed greater movement harmonicity and larger amplitudes. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9 and 17 | 9 |

| III. BILATERAL ARM TRAINING AND ROBOTICS | |||||

| Abdollahi, F., et al. [82] | M/F, 26 subjects, 26–77 y/o | FMA/ Wolf Motor Functional Ability Scale (WMFAS)/Motor activity log | Subjects’ 2-week gains in Fugl-Meyer score averaged 2.92, and we also observed improvements in Wolf Motor Functional Ability Scale average of 0.21 and Motor Activity Log of 0.58 for quantity and 0.63 for quality of life scores. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11 and 16 | 10 |

| Huang, J. J., et al. [83] | n/a, 40 subjects, n/a | EEG measurements | The results showed that stroke duration might influence the effects of hand rehabilitation in bilateral cortical corticocortical communication with significant main effects under different alpha and beta band conditions. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 and 10 | 9 |

| Li, Y. C., et al. [13] | F/M, 72 subjects, 20 to 80 y/o |

FMA UE/MAS/ABIL hand stroke impact scale/lateral pinch/accelerometer | Only between-group differences were detected for the primary outcome, FMA-UE. R-mirr enhanced upper limb motor improvement more effectively, and the effect could be maintained at 3 months of follow-up. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 and 16 | 9 |

| IV. BAT. AND VIRTUAL REALITY/VIDEO GUIDANCE | |||||

| Jayasinghe, S. A., et al. [84] | M/F, 15 stroke survivors and seven age-matched neurologically intact adults, 45–79 y/o | Fugl-Meyer, Jebsen Taylor | Chronic stroke survivors with mild hemiparesis show significant deficits in reaching aspects of bilateral coordination, However, there are no deficits in stabilizing against a movement-dependent spring load. |

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8 | 6 |

| V. BILATERAL LEG TRAINING | |||||

| Ardestani, et al. [85] | M/F, 50 subjects, 18–85 y/o | FMA UE, Changes in spatiotemporal, joint kinematics, and kinetics plus heart physiology variables were measured | High-intensity LT results in greater changes in kinematics and kinetics than lower-intensity interventions. The results may suggest greater paretic-limb contributions. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 13 and 15 | 10 |

| Jo, P. Y. [86] | M/F, 20 subjects, n/a | The primary clinical measure was a 10-m walk time. Additional measures were the Timed and test and the Stroke Impact Scale 3.0 | Interlimb symmetry and knee-ankle Variability post-stroke relate to walking performance. Interlimb angle-angle asymmetry does not relate to walking performance post-stroke. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 13 and 15 | 10 |

| VI. BILATERAL LEG TRAINING PLUS SENSORY ENHANCEMENT | |||||

| Kwong, P.W.H., et al. [87] | M/F, 72 subjects, 55–85 y/0 | The muscle strength of paretic ankle dorsiflexors (pDF) and plantarflexors (pPF) and paretic knee extensors (pKE) and flexors (pKF) were selected as the primary outcome measures of this study. | The application of bilateral TENS over the common peroneal nerve combined with TOT was superior to that of unilateral TENS combined with TOT in improving paretic ankle dorsiflexion strength. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 12 | 10 |

| VII. COMBINED BILATERAL ARM AND LEG TRAINING | |||||

| Arya et al. [15] | M/F, 50 subjects, n/a | The outcome measures were feasibility of activities, Fugl-Meyer assessment (FMA), Rivermead visual gait assessment (RVGA), Functional ambulation category (FAC), and modified Rankin scale (mRS). | The interlimb coupling training, a feasible program, may enhance stroke recovery of the upper and lower limbs and gait. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16 | 13 |

| VIII. BILATERAL RHYTHMIC LEG AND ARM TRAINING | |||||

| Klarner, T., et al. [25] | M/F, 19 subjects, 45–86 y/o | Test for muscle tone (modified Ashworth), functional ambulation (FAC), physical impairment (Chedoke–McMaster scale), touch discrimination (monofilament test), and reflex function for stroke participants. | Arm and leg cycling training induces plasticity and modifies reflex excitability after stroke. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 12, 13, 14 and 15 | 10 |

| IX. BILATERAL MOVEMENT PRIMING | |||||

| Stoykov, M. E., et al. [88] | F/M, 76 subjects, | The primary outcome measure is the Fugl-Meyer Test of Upper Extremity Function. The secondary outcome is the Chedoke Arm and Hand Activity Index-Nine, an assessment of bimanual functional tasks. | The first large-scale clinical trial of bilateral priming plus task-specific training. The authors have previously completed a feasibility intervention study of bilateral motor priming plus task-specific training and have considerable experience using this protocol. Outcome follows. | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 13, 15 and 16 | 10 |

3.1.2. Bilateral Arm Training

- Neurophysiological processes underpinning bilateral upper extremity (arms) training

3.1.3. Bilateral Arm Training Plus Sensory Enhancement

- Neurophysiological processes underpinning bilateral upper extremity plus sensory enhancement training

3.1.4. Bilateral Arm Training and Robotics

- Neurophysiological processes underpinning bilateral arm plus robotics training

3.1.5. Bilateral Arm Training and Virtual Reality/Computer Guidance

- Neurophysiological processes underpinning bilateral arm training and virtual reality—computer guidance

3.2. Bilateral Leg Training

3.2.1. Bilateral Leg Training and Sensory Enhancement

- Neurophysiological mechanisms underpinning Bilateral leg training and sensory enhancement

3.3. Bilateral Arm and Leg Training

3.3.1. Combined Bilateral Rhythmic Arm and Leg Training

- Neurophysiological mechanisms underpinning combined bilateral rhythmic arm and leg training

3.4. Bilateral Movement Priming

3.5. Interlimb Coupling and Quadrupedal Transfer

3.6. High-Intensity Versus Low-Intensity Bilateral Movement Post-Stroke Rehabilitation Training

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stoykov, M.E.; Madhavan, S. Motor priming in neurorehabilitation. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2015, 39, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, K.C.; Cauraugh, J.H.; Summers, J.J. Bilateral movement training and stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006, 244, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D.; Ward, S.H. An update on predicting motor recovery after stroke. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2014, 57, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, G.; Veerbeek, J.M.; Van Wegen, E.E.H.; Wolf, S.L. Constraint-induced movement therapy after stroke. The Lancet Neurology 2015, 14, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farthing, J.P.; Zehr, E.P. Restoring symmetry: Clinical applications of cross-education. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 42, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Carroll, T.J. Cross education: Possible mechanisms for the contralateral effects of unilateral resistance training. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjpal, P.; Qureshi, M.d.I.; Kovela, R.K.; Jain, M. Bilateral lower limb training for post-stroke survivors: A bibliometric analysis. Cureus 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauraugh, J.H.; Lodha, N.; Naik, S.K.; Summers, J.J. Bilateral movement training and stroke motor recovery progress: A structured review and meta-analysis. Human Movement Science 2010, 29, 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, P.; Wang, C.; Zeng, L.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, L. Optimal acupuncture methods for lower limb motor dysfunction after stroke: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1415792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, A.A.; Seelen, H.A.; Willmann, R.D.; Kingma, H. Technology-assisted training of arm-hand skills in stroke: Concepts on reacquisition of motor control and therapist guidelines for rehabilitation technology design. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2009, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, E.V.; Kirk, E.M. Jensen, W., Andersen, O.K., Akay, M., Eds.; Improving interlimb coordination following stroke: How can we change how people walk (and why should we). In Replace, repair, restore, relieve – bridging clinical and engineering solutions in neurorehabilitation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 7, pp. 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Zehr, E.P.; Barss, T.S.; Kaupp, C.; Klarner, T.; Mezzarane, R.A.; Nakajima, T.; Sun, Y.; Komiyama, T. Neuromechanical interlimb interactions and rehabilitation of walking after stroke. In Replace, repair, restore, relieve – bridging clinical and engineering solutions in neurorehabilitation; Jensen, W., Andersen, O.K., Akay, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 7, pp. 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.-P.; Wu, J.-J.; Zhou, Z.-L.; Xu, D.-S.; Zheng, M.-X.; Hua, X.-Y.; Xu, J.-G. Noninvasive brain stimulation for neurorehabilitation in post-stroke patients. Brain Sciences 2023, 13, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maceira-Elvira, P.; Popa, T.; Schmid, A.-C.; Hummel, F.C. Wearable technology in stroke rehabilitation: Towards improved diagnosis and treatment of upper-limb motor impairment. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, K.N.; Pandian, S.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Kashyap, V.K. Interlimb coupling in poststroke rehabilitation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2020, 27, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Malik, A.; Yaseen, A.; Mahmood, T.; Nazir, M.; Khan, S. Mobility related confidence level in chronic stroke patients through task oriented walking intervention. The Superior Journal of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, A.B.; Piitz, M.; Semrau, J.A.; Hill, M.D.; Scott, S.H.; Dukelow, S.P. Robot enhanced stroke therapy optimizes rehabilitation (restore): A pilot study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, S.; Mehrholz, J.; Werner, C. Robot-assisted upper and lower limb rehabilitation after stroke: Walking and arm/hand function. Deutsches Arzteblatt international 2008, 105, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauraugh, J.H.; Kang, N. Bimanual movements and chronic stroke rehabilitation: Looking back and looking forward. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 10858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatem, S.M.; Saussez, G.; Della Faille, M.; Prist, V.; Zhang, X.; Dispa, D.; Bleyenheuft, Y. Rehabilitation of motor function after stroke: A multiple systematic review focused on techniques to stimulate upper extremity recovery. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, B.; Thomas, L.H.; Coupe, J.; McMahon, N.E.; Connell, L.; Harrison, J.; Sutton, C.J.; Tishkovskaya, S.; Watkins, C.L. Repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.A.; Koo, B.I.; Shin, M.J.; Shin, Y.B.; Ko, H.-Y.; Shin, Y.-I. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy and mirror therapy for patients with subacute stroke. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine 2014, 38, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, V. Spinal cord pattern generators for locomotion. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaupp, C.; Pearcey, G.E.P.; Klarner, T.; Sun, Y.; Cullen, H.; Barss, T.S.; Zehr, E.P. Rhythmic arm cycling training improves walking and neurophysiological integrity in chronic stroke: The arms can give legs a helping hand in rehabilitation. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 119, 1095–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klarner, T.; Barss, T.; Sun, Y.; Kaupp, C.; Loadman, P.; Zehr, E. Long-term plasticity in reflex excitability induced by five weeks of arm and leg cycling training after stroke. Brain Sciences 2016, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitall, J.; Waller, S.M.; Silver, K.H.C.; Macko, R.F. Repetitive bilateral arm training with rhythmic auditory cueing improves motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Stroke 2000, 31, 2390–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauraugh, J.H.; Summers, J.J. Neural plasticity and bilateral movements: A rehabilitation approach for chronic stroke. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005, 75, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.J.; Kagerer, F.A.; Garry, M.I.; Hiraga, C.Y.; Loftus, A.; Cauraugh, J.H. Bilateral and unilateral movement training on upper limb function in chronic stroke patients: A tms study. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007, 252, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.J.; Kim, J.Y. The effects of bilateral movement training on upper limb function in chronic stroke patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2016, 28, 2299–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjpal, P.; Qureshi, M.d.I.; Kovela, R.K.; Jain, M. Efficacy of bilateral lower limb training over unilateral to re-educate balance and walking in post-stroke survivors: A protocol for randomized clinical trial. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 2021, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.Y.; Lang, C.E. Using dual tasks to test immediate transfer of training between naturalistic movements: A proof-of-principle study. Journal of Motor Behavior 2012, 44, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauraugh, J.H.; Kim, S. Two coupled motor recovery protocols are better than one: Electromyogram-triggered neuromuscular stimulation and bilateral movements. Stroke 2002, 33, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.N.; Perreault, E.J. Side of lesion influences bilateral activation in chronic, post-stroke hemiparesis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2007, 118, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schick, T.; Kolm, D.; Leitner, A.; Schober, S.; Steinmetz, M.; Fheodoroff, K. Efficacy of four-channel functional electrical stimulation on moderate arm paresis in subacute stroke patients—results from a randomized controlled trial. Healthcare 2022, 10, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, D.A.E.; Cauraugh, J.H.; Hausenblas, H.A. Electromyogram-triggered neuromuscular stimulation and stroke motor recovery of arm/hand functions: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2004, 223, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, V.; Holliger, N.S.; Christen, A.; Geissmann, M.; Filli, L. Neural coordination of bilateral hand movements: Evidence for an involvement of brainstem motor centres. The Journal of Physiology 2024, 602, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.L.; Ting, L.H.; Kesar, T.M. Gait rehabilitation using functional electrical stimulation induces changes in ankle muscle coordination in stroke survivors: A preliminary study. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Park, S.H.; Han, J.W. Effect of bilateral upper extremity exercise on trunk performance in patients with stroke. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2017, 29, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.C.; Tears, C.; Morris, A.; Alexanders, J. The effects of unilateral versus bilateral motor training on upper limb function in adults with chronic stroke: A systematic review. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Lin, K.-c.; Li, Y.-c.; Lin, C.-J. Predicting patient-reported outcome of activities of daily living in stroke rehabilitation: A machine learning study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, C.I.E.; Brendel, C.; Hummelsheim, H. Bilateral arm training vs unilateral arm training for severely affected patients with stroke: Exploratory single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qiu, Y.; Bassile, C.C.; Lee, A.; Chen, R.; Xu, D. Effectiveness and success factors of bilateral arm training after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 875794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembele, J.; Triccas, L.T.; Amanzonwé, L.E.R.; Kossi, O.; Spooren, A. Bilateral versus unilateral upper limb training in (sub)acute stroke: A systematic and meta-analysis. South African Journal of Physiotherapy 2024, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethy, D.; Bajpai, P.; Kujur, E.S.; Mohakud, K.; Sahoo, S. Effectiveness of modified constraint induced movement therapy and bilateral arm training on upper extremity function after chronic stroke: A comparative study. Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 2016, 04, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.D.; Marrocco, S.; Brown, J.; Patterson, K.K. A novel bilateral lower extremity mirror therapy intervention for individuals with stroke. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.H.; Kim, Y.-H. Robot-assisted therapy in stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Stroke 2013, 15, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiner, C.T.; Byblow, W.D.; McNulty, P.A. Bilateral priming before wii-based movement therapy enhances upper limb rehabilitation and its retention after stroke: A case-controlled study. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2014, 28, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-m.; Kwong, P.W.H.; Lai, C.K.Y.; Ng, S.S.M. Comparison of bilateral and unilateral upper limb training in people with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0216357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinear, C.M.; Petoe, M.A.; Anwar, S.; Barber, P.A.; Byblow, W.D. Bilateral priming accelerates recovery of upper limb function after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2014, 45, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, M.S.; Whitall, J.; Jenkins, T.; Magder, L.S.; Hanley, D.F.; Goldberg, A.; Luft, A.R. Sequencing bilateral and unilateral task-oriented training versus task oriented training alone to improve arm function in individuals with chronic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Delden, A.L.E.Q.; Peper, C.L.E.; Kwakkel, G.; Beek, P.J. A systematic review of bilateral upper limb training devices for poststroke rehabilitation. Stroke Research and Treatment 2012, 2012, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, N.; Biswas, A.; Hanifa, N.; Rv, P.; Sundaram, P. Bilateral versus unilateral upper extremity training on upper limb motor activity in hemiplegia. International journal of neurorehabilitation 2015, 02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.-C.; Steele, C.J.; Hoepfel, D.; Muffel, T.; Villringer, A.; Sehm, B. The impact of lesion side on bilateral upper limb coordination after stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2023, 20, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Lei, Y.; Xiong, K.; Marek, K. Substantial generalization of sensorimotor learning from bilateral to unilateral movement conditions. PLoS One 2013, 8, e58495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-y.; Chuang, L.-l.; Lin, K.-c.; Chen, H.-c.; Tsay, P.-k. Randomized trial of distributed constraint-induced therapy versus bilateral arm training for the rehabilitation of upper-limb motor control and function after stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2011, 25, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, J.; Doyle, S.T.; Hurvitz, E.A.; Brown, S.H. Influence of task on interlimb coordination in adults with cerebral palsy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardin, E.; Bontemps, D.; Babuin, N.-T.; Herman, B.; Denis, A.; Bihin, B.; Regnier, M.; Leeuwerck, M.; Deltombe, T.; Riga, A.; et al. Bimanual motor skill learning with robotics in chronic stroke: Comparison between minimally impaired and moderately impaired patients, and healthy individuals. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, R.G.; Kelly, S.P. Neurophysiology of human perceptual decision-making. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2021, 44, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, S.; Böttcher, A.; Adelhöfer, N.; Raab, M.; Beste, C.; Hoffmann, S. Neural oscillations guiding action during effects imagery. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 469, 115063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repp, B.H.; Su, Y.-H. Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006–2012). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2013, 20, 403–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ji, C.; Gu, L.; Wu, X. Auditory over visual advantage of sensorimotor synchronization in 6- to 7-year-old children but not in 12- to 15-year-old children and adults. JExPH 2018, 44, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, K.; Asai, T.; Amemiya, Y. An analog cmos central pattern generator for interlimb coordination in quadruped locomotion. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks 2003, 14, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillner, S. Biological pattern generation: The cellular and computational logic of networks in motion. Neuron 2006, 52, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKay-Lyons, M. Central pattern generation of locomotion: A review of the evidence. Phys. Ther. 2002, 82, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morquette, P.; Verdier, D.; Kadala, A.; Féthière, J.; Philippe, A.G.; Robitaille, R.; Kolta, A. An astrocyte-dependent mechanism for neuronal rhythmogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.A.; DeWeerth, S.P. A comparison of resonance tuning with positive versus negative sensory feedback. Biol. Cybern. 2007, 96, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guertin, P.A. Central pattern generator for locomotion: Anatomical, physiological, and pathophysiological considerations. Front. Neurol. 2013, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D.; Stel, M. If they move in sync, they must feel in sync: Movement synchrony leads to attributions of rapport and entitativity. Soc. Cogn. 2011, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschersleben, G. Temporal control of movements in sensorimotor synchronization. Brain Cogn. 2002, 48, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachykov, A.; Henaff, P.; Shachykov, A.; Popov, A.; Shulyak, A. Neuro-musculoskeletal simulator of human rhythmic movements. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE First Ukraine Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (UKRCON), 5/2017, 2017; pp. 278–283.

- Bruyneel, A.-V.; Higgins, J.; Akremi, H.; Aissaoui, R.; Nadeau, S. Postural organization and inter-limb coordination are altered after stroke when an isometric maximum bilateral pushing effort of the upper limbs is performed. Clin. Biomech. 2021, 86, 105388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakate, D.; Bhattad, R. Study the effectiveness of bilateral arm training on upper extremity motor function and activity level in patients with sub-acute stroke. International Journal of Current Research and Review 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, S.V.; Miller, A.; Quinn, L.; Youdan, G.; Bishop, L.; Ruthrauff, H.; Wade, E. Quantifying intra- and interlimb use during unimanual and bimanual tasks in persons with hemiparesis post-stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itkonen, M.; Costa, Á.; Yamasaki, H.; Okajima, S.; Alnajjar, F.; Kumada, T.; Shimoda, S. Influence of bimanual exercise on muscle activation in post-stroke patients. ROBOMECH Journal 2019, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Jo, S.; Bae, K.; Song, C. Comparison of upper extremity muscle activity between stroke patients and healthy participants while performing bimanual tasks. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science 2022, 11, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, M.; Uehara, S.; Kurayama, T.; Kitamura, S.; Sakata, S.; Kondo, K.; Shimizu, E.; Yoshinaga, N.; Otaka, Y. Effects of alternating bilateral training between non-paretic and paretic upper limbs in patients with hemiparetic stroke: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 54, jrm00336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, G.; Meng, X.; Tan, Y.; Yu, J.; Jin, A.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X. Short-term efficacy of hand-arm bimanual intensive training on upper arm function in acute stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 2018, 8, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Chou, L.-W.; Luo, H.-J.; Tsai, P.-Y.; Lieu, F.-K.; Chiang, S.-L.; Sung, W.-H. Effects of computer-aided interlimb force coupling training on paretic hand and arm motor control following chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0131048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.C.; Farias, N.C.; Gomes, R.P.; Michaelsen, S.M. Feasibility and effectiveness of adding object-related bilateral symmetrical training to mirror therapy in chronic stroke: A randomized controlled pilot study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2016, 32, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.B. The effects of task-oriented versus repetitive bilateral arm training on upper limb function and activities of daily living in stroke patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2015, 27, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Delden, A.L.E.Q.; Beek, P.J.; Roerdink, M.; Kwakkel, G.; Peper, C.L.E. Unilateral and bilateral upper-limb training interventions after stroke have similar effects on bimanual coupling strength. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2015, 29, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, F.; Corrigan, M.; Lazzaro, E.D.C.; Kenyon, R.V.; Patton, J.L. Error-augmented bimanual therapy for stroke survivors. NeuroRehabilitation 2018, 43, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-J.; Pei, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Tseng, S.-S.; Hung, J.-W. Bilateral sensorimotor cortical communication modulated by multiple hand training in stroke participants: A single training session pilot study. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, S.A.L.; Maenza, C.; Good, D.C.; Sainburg, R.L. Deficits in performance on a mechanically coupled asymmetrical bilateral task in chronic stroke survivors with mild unilateral paresis. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardestani, M.M.; Henderson, C.E.; Mahtani, G.; Connolly, M.; Hornby, T.G. Locomotor kinematics and kinetics following high-intensity stepping training in variable contexts poststroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, P.Y. Intralimb coordination and intermuscular coherence in walking after stroke. Dissertation, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, 2019.

- Kwong, P.W.H.; Ng, G.Y.F.; Chung, R.C.K.; Ng, S.S.M. Bilateral transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation improves lower-limb motor function in subjects with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Heart Association 2018, 7, e007341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoykov, M.E.; King, E.; David, F.J.; Vatinno, A.; Fogg, L.; Corcos, D.M. Bilateral motor priming for post stroke upper extremity hemiparesis: A randomized pilot study. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2020, 38, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiper, P.; Godart, N.; Cavalier, M.; Berard, C.; Cieślik, B.; Federico, S.; Kiper, A.; Pellicciari, L.; Meroni, R. Effects of immersive virtual reality on upper-extremity stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazac, G.I. Virtual reality based-therapy: Targeting balance impairments to improve gait in stroke. Știința și arta mișcării 2022, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zehr, E.P. Sensory enhancement amplifies interlimb cutaneous reflexes in wrist extensor muscles. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 122, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-M.; Lee, B.-H. Effects of virtual reality-based bilateral upper-extremity training on brain activity in post-stroke patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2015, 27, 2285–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-H.; Lee, H.-M. Effect of immersive virtual reality-based bilateral arm training in patients with chronic stroke. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigon, A.; Collins, D.F.; Zehr, E.P. Effect of rhythmic arm movement on reflexes in the legs: Modulation of soleus h-reflexes and somatosensory conditioning. J. Neurophysiol. 2004, 91, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehr, E.P.; Balter, J.E.; Ferris, D.P.; Hundza, S.R.; Loadman, P.M.; Stoloff, R.H. Neural regulation of rhythmic arm and leg movement is conserved across human locomotor tasks. The Journal of Physiology 2007, 582, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragert, K.; Zehr, E.P. Rhythmic arm cycling modulates hoffmann reflex excitability differentially in the ankle flexor and extensor muscles. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 450, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Alvarado, L.; Kim, S.; Chong, S.L.; Mushahwar, V.K. Modulation of corticospinal input to the legs by arm and leg cycling in people with incomplete spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 2017, 118, 2507–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, H.T.; Stinear, C.M. Effects of bilateral priming on motor cortex function in healthy adults. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 120, 2858–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, S.; Stinear, J.W.; Kanekar, N. Effects of a single session of high intensity interval treadmill training on corticomotor excitability following stroke: Implications for therapy. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, S.; Ghai, I. Effects of rhythmic auditory cueing in gait rehabilitation for multiple sclerosis: A mini systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoykov, M.E.; Corcos, D.M. A review of bilateral training for upper extremity hemiparesis. Occup. Ther. Int. 2009, 16, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoykov, M.E.; Lewis, G.N.; Corcos, D.M. Comparison of bilateral and unilateral training for upper extremity hemiparesis in stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2009, 23, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Lee, J.-H.; Koo, H.-M.; Lee, S.-M. Effectiveness of bilateral arm training for improving extremity function and activities of daily living performance in hemiplegic patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 26, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Liew, B.; Chaabene, H.; Behm, D.G.; García-Hermoso, A.; Izquierdo, M.; Granacher, U. Effects of bilateral and unilateral resistance training on horizontally orientated movement performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; He, J.; Shu, B.; Jia, J. Multi-sensory feedback therapy combined with task-oriented training on the hemiparetic upper limb in chronic stroke: Study protocol for a pilot randomized controlled trial. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bayona, N.A.; Bitensky, J.; Salter, K.; Teasell, R. The role of task-specific training in rehabilitation therapies. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2005, 12, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, H.; Rosén, B.; Björkman, A.; Pessah-Rasmussen, H.; Brogårdh, C. Sensory re-learning of the upper limb (sensupp) after stroke: Development and description of a novel intervention using the tidier checklist. Trials 2021, 22, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amki, M.; Baumgartner, P.; Bracko, O.; Luft, A.R.; Wegener, S. Task-specific motor rehabilitation therapy after stroke improves performance in a different motor task: Translational evidence. Translational Stroke Research 2017, 8, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkenmeier, R.L.; Prager, E.M.; Lang, C.E. Translating animal doses of task-specific training to people with chronic stroke in 1-hour therapy sessions: A proof-of-concept study. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2010, 24, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolbow, D.R.; Gorgey, A.S.; Recio, A.C.; Stiens, S.A.; Curry, A.C.; Sadowsky, C.L.; Gater, D.R.; Martin, R.; McDonald, J.W. Activity-based restorative therapies after spinal cord injury: Inter-institutional conceptions and perceptions. Aging Dis. 2015, 6, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.; Turton, A.J.; Van Wijck, F.; Van Vliet, P. Task-specific reach-to-grasp training after stroke: Development and description of a home-based intervention. Clin. Rehabil. 2016, 30, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khallaf, M.E. Effect of task-specific training on trunk control and balance in patients with subacute stroke. Neurol. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grefkes, C.; Fink, G.R. Recovery from stroke: Current concepts and future perspectives. Neurological Research and Practice 2020, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demers, M.; Varghese, R.; Winstein, C.J. Retrospective exploratory analysis of task-specific effects on brain activity after stroke. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Saeed, A.; Batool, S.; Waqqar, S.; Khattak, H.G.; Jabeen, H. Effects of task-oriented balance training with sensory integration in post stroke patients. The Rehabilitation Journal 2023, 07, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaramonte, R.; Bonfiglio, M.; Leonforte, P.; Coltraro, G.; Guerrera, C.; Vecchio, M. Proprioceptive and dual-task training: The key of stroke rehabilitation, a systematic review. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, D.M.; Bassetti, C.L. Role of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep-wake disturbances for stroke and stroke recovery. Neurology 2016, 87, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinear, C.M.; Byblow, W.D.; Steyvers, M.; Levin, O.; Swinnen, S.P. Kinesthetic, but not visual, motor imagery modulates corticomotor excitability. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 168, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosp, J.A.; Luft, A.R. Cortical plasticity during motor learning and recovery after ischemic stroke. Neural Plast. 2011, 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, M.N.; Koblar, S.; Ward, N.S.; Rothwell, J.C.; Hordacre, B.; Ridding, M.C. An investigation of cortical neuroplasticity following stroke in adults: Is there evidence for a critical window for rehabilitation? BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleimen-Malkoun, R.; Temprado, J.-J.; Thefenne, L.; Berton, E. Bimanual training in stroke: How do coupling and symmetry-breaking matter? BMC Neurol. 2011, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, R.; Gebara, R.; Andary, M.; Sylvain, J. Chronic stroke survivors show task-dependent modulation of motor variability during bimanual coordination. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 121, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metrot, J.; Mottet, D.; Hauret, I.; Van Dokkum, L.; Bonnin-Koang, H.-Y.; Torre, K.; Laffont, I. Changes in bimanual coordination during the first 6 weeks after moderate hemiparetic stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2013, 27, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaki, L.; Boroojerdi, B.; Kaelin-Lang, A.; Burstein, A.H.; Bütefisch, C.M.; Kopylev, L.; Davis, B.; Cohen, L.G. Cholinergic influences on use-dependent plasticity. J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 87, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaki, L.; Wu, C.W.-H.; Kaelin-Lang, A.; Cohen, L.G. Effects of somatosensory stimulation on use-dependent plasticity in chronic stroke. Stroke 2006, 37, 246–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldelari, P.; Lemon, R.; Dietz, V. Differential neural coordination of bilateral hand and finger movements. Physiological Reports 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, C.M.; Doyle, O.N.; Gallegos, N.E.; Irwin, Z.T.; Olson, J.W.; Gonzalez, C.L.; Knight, R.T.; Ivry, R.B.; Walker, H.C. Differential contribution of sensorimotor cortex and subthalamic nucleus to unimanual and bimanual hand movements. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhad492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstein, C.J.; Wolf, S.L.; Dromerick, A.W.; Lane, C.J.; Nelsen, M.A.; Lewthwaite, R.; Cen, S.Y.; Azen, S.P.; Team, f.t.I.C.A.R.E.I.I. Effect of a task-oriented rehabilitation program on upper extremity recovery following motor stroke: The icare randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Winckel, A.; Ehrlich-Jones, L. Measurement characteristics and clinical utility of the motor evaluation scale for upper extremity in stroke patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2657–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisoli, A.; Procopio, C.; Chisari, C.; Creatini, I.; Bonfiglio, L.; Bergamasco, M.; Rossi, B.; Carboncini, M. Positive effects of robotic exoskeleton training of upper limb reaching movements after stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, R.; Melegari, C.; De Cola, M.C.; Bramanti, A.; Bramanti, P.; Calabrò, R.S. Effects of robot-assisted upper limb rehabilitation in stroke patients: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Cui, F.; Zou, Y.; Bai, L. Acupuncture enhances effective connectivity between cerebellum and primary sensorimotor cortex in patients with stable recovery stroke. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 2014, 603909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.H.; Song, W.-K. Robot-assisted reach training for improving upper extremity function of chronic stroke. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine 2015, 237, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, K.P.; Asis, K.D.; Mang, C.S.; Neva, J.L.; Peters, S.; Lakhani, B.; Boyd, L.A. Predicting motor sequence learning in individuals with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2017, 31, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullick, A.A.; Subramanian, S.K.; Levin, M.F. Emerging evidence of the association between cognitive deficits and arm motor recovery after stroke: A meta-analysis. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2015, 33, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cai, H.; Leelayuwat, N. Intervention effect of rehabilitation robotic bed under machine learning combined with intensive motor training on stroke patients with hemiplegia. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 865403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, S.M.; Whitall, J. Bilateral arm training: Why and who benefits? NeuroRehabilitation 2008, 23, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.-L.; Chen, Y.-L.; Chen, C.-C.; Li, Y.-C.; Wong, A.M.-K.; Hsu, A.-L.; Chang, Y.-J. Effect of emg-triggered neuromuscular electrical stimulation with bilateral arm training on hemiplegic shoulder pain and arm function after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, C.; Morales-Quezada, L.; Fregni, F. A combined therapeutic approach in stroke rehabilitation: A review on non-invasive brain stimulation plus pharmacotherapy. International journal of neurorehabilitation 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Luo, J.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guo, S. Vibrotactile enhancement in hand rehabilitation has a reinforcing effect on sensorimotor brain activities. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 935827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, N.D.; Jahanshahi, H.; Yao, Q.; Mou, J.; Bekiros, S. Identification and control of rehabilitation robots with unknown dynamics: A new probabilistic algorithm based on a finite-time estimator. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.S.; Pelled, G. Novel neuromodulation techniques to assess interhemispheric communication in neural injury and neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in Neural Circuits 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J. Exploration on neurobiological mechanisms of the central–peripheral–central closed-loop rehabilitation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 982881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, F.; Yan, Z.; Cheng, S.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Therapeutic effects of sensory input training on motor function rehabilitation after stroke. Medicine 2018, 97, e13387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognini, N.; Russo, C.; Edwards, D.J. The sensory side of post-stroke motor rehabilitation. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2016, 34, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, R.; Zhao, X.; Yin, R.; Song, P.; Liu, B.; Song, R.; Chen, W.; et al. Bilateral upper limb robot-assisted rehabilitation improves upper limb motor function in stroke patients: A study based on quantitative eeg. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdat, S.; Darainy, M.; Thiel, A.; Ostry, D.J. A single session of robot-controlled proprioceptive training modulates functional connectivity of sensory motor networks and improves reaching accuracy in chronic stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2019, 33, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Delden, A.; Peper, C.; Beek, P.; Kwakkel, G. Unilateral versus bilateral upper limb exercise therapy after stroke: A systematic review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 44, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Gao, X.; Pan, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, B.; Li, J. Anxiety detection and training task adaptation in robot-assisted active stroke rehabilitation. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2018, 15, 1729881418806433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, S.; Battaglino, A.; Sinatti, P.; Sánchez-Romero, E.A.; Ruiz-Rodriguez, I.; Manca, M.; Gargano, S.; Villafañe, J.H. The effectiveness of robotic rehabilitation for the functional recovery of the upper limb in post-stroke patients: A systematic review. Retos 2023, 50, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khor, K.X.; Chin, P.J.H.; Hisyam, A.R.; Yeong, C.F.; Narayanan, A.L.T.; Su, E.L.M. Development of cr2-haptic: A compact and portable rehabilitation robot for wrist and forearm training. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES), 12/2014, 2014; pp. 424–429.

- Su, D.; Hu, Z.; Wu, J.; Shang, P.; Luo, Z. Review of adaptive control for stroke lower limb exoskeleton rehabilitation robot based on motion intention recognition. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17, 1186175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Park, G.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Ham, Y.; Hwang, D.; Kwon, S.; Shin, J.-H. A comparison of the effects and usability of two exoskeletal robots with and without robotic actuation for upper extremity rehabilitation among patients with stroke: A single-blinded randomised controlled pilot study. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Chung, Y. The effects of providing visual feedback and auditory stimulation using a robotic device on balance and gait abilities in persons with stroke: A pilot study. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science 2016, 5, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wu, Y.-N.; Yang, C.-Y.; Xu, T.; Harvey, R.L.; Zhang, L.-Q. Developing a wearable ankle rehabilitation robotic device for in-bed acute stroke rehabilitation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017, 25, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-c.; Lin, K.-c.; Chen, C.-l.; Yao, G.; Chang, Y.-j.; Lee, Y.-y.; Liu, C.-t.; Chen, W.-S. Three ways to improve arm function in the chronic phase after stroke by robotic priming combined with mirror therapy, arm training, and movement-oriented therapy. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-c.; Li, Y.-c.; Lin, K.-c.; Yao, G.; Chang, Y.-j.; Lee, Y.-y.; Liu, C.-t.; Hsu, W.-l.; Wu, Y.-h.; Chu, H.-t.; et al. Effects of robotic priming of bilateral arm training, mirror therapy, and impairment-oriented training on sensorimotor and daily functions in patients with chronic stroke: Study protocol of a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Trials 2022, 23, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fan, T.; Qi, Q.; Wang, J.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Ye, J.; Chen, G.; Long, J.; et al. Efficacy of a novel exoskeletal robot for locomotor rehabilitation in stroke patients: A multi-center, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 706569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.-H.; Kim, K.-M.; Oh, J.-S.; Chang, M. The effects of bilateral arm training on reaching performance and activities of daily living of stroke patients. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2013, 25, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, E.-K.; Lee, S.-H. Effects of virtual reality training with modified constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function in acute stage stroke: A preliminary study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2016, 28, 3168–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D. Construction of sports music integration training and performance practice system based on virtual reality technology. Journal of Electrical Systems 2024, 20, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, G.H.; Hwangbo, G.; Shin, H.S. The effects of virtual reality-based balance training on balance of the elderly. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2014, 26, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. Impact of instant visual guidance via video technology on the correction of some offensive skills performance errors in basketball أثر التوجيه البصري الفوري عبر تقنية الفيديو في تصحيح بعض أخطاء أداء المهارات الهجومية في كرة السلة. Asian J. Sports Med. 2023, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhorne, P.; Coupar, F.; Pollock, A. Motor recovery after stroke: A systematic review. The Lancet Neurology 2009, 8, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrholz, J.; Pohl, M.; Platz, T.; Kugler, J.; Elsner, B. Electromechanical and robot-assisted arm training for improving activities of daily living, arm function, and arm muscle strength after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonsetler, E.C.; Bowden, M.G. A systematic review of mechanisms of gait speed change post-stroke. Part 2: Exercise capacity, muscle activation, kinetics, and kinematics. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2017, 24, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Miyoshi, S.; Chen, C.-H.; Lee, K.-C.; Chang, L.-C.; Chung, J.-H.; Shi, H.-Y. Walking ability and functional status after post-acute care for stroke rehabilitation in different age groups: A prospective study based on propensity score matching. Aging 2020, 12, 10704–10714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M.A.; Moore, M.F.; Pohlig, R.; Reisman, D. Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between balance/walking performance, activity, and participation after stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2015, 23, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.J.; Hwang, B.Y. Effect of bilateral lower limb strengthening exercise on balance and walking in hemiparetic patients after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2018, 30, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellaiche, S.; Ibarolla, D.; Redouté, J.; Comte, J.-C.; Medée, B.; Arsenault, L.; Mayel, A.; Revol, P.; Delporte, L.; Cotton, F.; et al. Upper limb rehabilitation after stroke: Constraint versus intensive training. A longitudinal case-control study correlating motor performance with fmri data. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, G.; Shin, J.-H.; You, J.H. Neuroplastic effects of end-effector robotic gait training for hemiparetic stroke: A randomised controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyana, S.; Lohar, D.; Khan, J.; Rao, L.S. Effectiveness of supplemented backward walking training along with conventional therapy on balance and functional outcome in patients with stroke. International Journal of Current Pharmaceutical Research 2023, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, D.R.; Mortenson, W.B.; Durocher, M.; Schneeberg, A.; Teasell, R.; Yao, J.; Eng, J.J. Efficacy of an exoskeleton-based physical therapy program for non-ambulatory patients during subacute stroke rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, H.-J. Effect of robot-assisted wearable exoskeleton on gait speed of post-stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a randomized controlled trials. Physical Therapy Rehabilitation Science 2022, 11, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, K.J.; Karunakaran, K.K.; Roberts, P.; Tefertiller, C.; Walter, A.M.; Zhang, J.; Leslie, D.; Jayaraman, A.; Francisco, G.E. Utilization of robotic exoskeleton for overground walking in acute and chronic stroke. Front. Neurorobot. 2021, 15, 689363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesing, C.; Fisch, G.; O’Donnell, M.; Shahidi, I.; Thomas, L.; Mummidisetty, C.K.; Williams, K.J.; Takahashi, H.; Rymer, W.Z.; Jayaraman, A. Effects of a wearable exoskeleton stride management assist system (sma®) on spatiotemporal gait characteristics in individuals after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2015, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacksteit, R.; Stöckel, T.; Behrens, M.; Feldhege, F.; Bergschmidt, P.; Bader, R.; Mittelmeier, W.; Skripitz, R.; Mau-Moeller, A. Low-load unilateral and bilateral resistance training to restore lower limb function in the early rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized active-controlled clinical trial. Frontiers in Medicine 2021, 8, 628021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterno, M.V.; Rauh, M.J.; Schmitt, L.C.; Ford, K.R.; Hewett, T.E. Incidence of contralateral and ipsilateral anterior cruciate ligament (acl) injury after primary acl reconstruction and return to sport. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2012, 22, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.A.; Gabriel, D.A. The effect of unilateral training on contralateral limb strength in young, older, and patient populations: A meta-analysis of cross education. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2018, 23, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.B.; Behm, D.G.; Chaouachi, A. Evidence of homologous and heterologous effects after unilateral leg training in youth. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilp, M.; Ringler, S.; Mariacher, H.; Rafolt, D. Unilateral strength training after total knee arthroplasty leads to similar or better effects on strength and flexibility than bilateral strength training – a randomized controlled pilot study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 55, jrm00381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.S.; Yamada, Y.; Kataoka, R.; Hammert, W.B.; Kang, A.; Spitz, R.W.; Wong, V.; Seffrin, A.; Kassiano, W.; Loenneke, J.P. Does unilateral high-load resistance training influence strength change in the contralateral arm also undergoing high-load training? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2024, 34, e14772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coratella, G.; Galas, A.; Campa, F.; Pedrinolla, A.; Schena, F.; Venturelli, M. The eccentric phase in unilateral resistance training enhances and preserves the contralateral knee extensors strength gains after detraining in women: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 788473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Onishi, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Yamauchi, J.; Kawada, S. Effects of motor imagery combined with action observation training on the lateral specificity of muscle strength in healthy subjects. Biomedical Research 2019, 40, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Song, B.-W.; Yang, W. Design of exoskeleton-type wrist human–machine interface based on over-actuated coaxial spherical parallel mechanism. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2018, 10, 1687814017753896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peurala, S.H.; Kantanen, M.P.; Sjögren, T.; Paltamaa, J.; Karhula, M.; Heinonen, A. Effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy on activity and participation after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Rehabil. 2012, 26, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ji, Q.; Xin, R.; Zhang, D.; Na, X.; Peng, R.; Li, K. Contralesional cortical structural reorganization contributes to motor recovery after sub-cortical stroke: A longitudinal voxel-based morphometry study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwill, A.M.; Teo, W.-P.; Morgan, P.; Daly, R.M.; Kidgell, D.J. Bihemispheric-tdcs and upper limb rehabilitation improves retention of motor function in chronic stroke: A pilot study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starosta, M.; Cichoń, N.; Saluk-Bijak, J.; Miller, E. Benefits from repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in post-stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustin, M.; Hensel, L.; Fink, G.R.; Grefkes, C.; Tscherpel, C. Individual contralesional recruitment in the context of structural reserve in early motor reorganization after stroke. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Grefkes, C.; Nowak, D.A.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Dafotakis, M.; Küst, J.; Karbe, H.; Fink, G.R. Cortical connectivity after subcortical stroke assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.; Schranz, C.; Seo, N.J. Associating functional neural connectivity and specific aspects of sensorimotor control in chronic stroke. Sensors 2023, 23, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, R.; Cunningham, D.A.; Hogue, O.; Schroedel, M.; Campbell, B.A.; Plow, E.B.; Baker, K.B.; Machado, A.G. Cortico-cerebellar connectivity underlying motor control in chronic poststroke individuals. The Journal of Neuroscience 2022, 42, 5186–5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek, S.; Siegel, J.S.; Gordon, E.M.; Raut, R.V.; Gratton, C.; Newbold, D.J.; Ortega, M.; Laumann, T.O.; Adeyemo, B.; Miller, D.B.; et al. Spatial and temporal organization of the individual human cerebellum. Neuron 2018, 100, 977–993.e977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkeltaub, P.E.; Swears, M.K.; D’Mello, A.M.; Stoodley, C.J. Cerebellar tdcs as a novel treatment for aphasia? Evidence from behavioral and resting-state functional connectivity data in healthy adults. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2016, 34, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, T.; Qin, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Meng, L.; Ji, X.; Yu, C. Altered functional connectivity of cognitive-related cerebellar subregions in well-recovered stroke patients. Neural Plast. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.A.; Peltier, S.J.; Wiggins, J.L.; Jaeggi, S.M.; Buschkuehl, M.; Fling, B.W.; Kwak, Y.; Jonides, J.; Monk, C.S.; Seidler, R.D. Disrupted cortico-cerebellar connectivity in older adults. Neuroimage 2013, 83, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Madhavan, S. Non-paretic leg movements can facilitate cortical drive to the paretic leg in individuals post stroke with severe motor impairment: Implications for motor priming. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2023, 58, 2853–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.W.; Tang, Z.Y.; Zhang, F.R.; Li, H.; Kong, Y.Z.; Iannetti, G.D.; Hu, L. Neurobiological mechanisms of tens-induced analgesia. Neuroimage 2019, 195, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. PsychologR 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Cleary, T.J. Adolescents ’ development of personal agency the role of self-efficacy beliefs and self-regulatory skill. In Adolescence and education: Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents, Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, 2006; Volume 5, pp. 45–69.

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. AmP 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.M.; Elliot, A.J.; Kim, Y.; Kasser, T. What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. JPSP 2001, 80, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, H.; Sun, H.; Ren, L.; Jiang, H.; Chen, M.; Dong, C. Influencing factors of psychological resilience in stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2024, 39, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Dong, F.; Wu, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, F. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (tens) alleviates brain ischemic injury by regulating neuronal oxidative stress, pyroptosis, and mitophagy. Mediators Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, K.; Takahashi, T.; Koga, T.; Osu, R. Somatosensory stimulation on the wrist enhances the subsequent hand-choice by biasing toward the stimulated hand. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Noble, J.W.; Eng, J.J.; Boyd, L.A. Bilateral motor tasks involve more brain regions and higher neural activation than unilateral tasks: An fmri study. Exp. Brain Res. 2014, 232, 2785–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grefkes, C.; Fink, G.R. Reorganization of cerebral networks after stroke: New insights from neuroimaging with connectivity approaches. Brain 2011, 134, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taud, B.; Lindenberg, R.; Darkow, R.; Wevers, J.; Höfflin, D.; Grittner, U.; Meinzer, M.; Flöel, A. No add-on effects of unilateral and bilateral transcranial direct current stimulation on fine motor skill training outcome in chronic stroke. A randomized controlled trial. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Safdar, A.; Smith, M.-C.; Byblow, W.D.; Stinear, C.M. Applications of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to improve upper limb motor performance after stroke: A systematic review. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2023, 37, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Prasad, M.; Das, A.; Vibha, D.; Garg, A.; Goyal, V.; Srivastava, A.K. Utility of transcranial magnetic stimulation and diffusion tensor imaging for prediction of upper-limb motor recovery in acute ischemic stroke patients. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 2022, 25, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle, C.E.; Baumer, F.M.; Jordan, J.T.; Berry, K.; Garcia, M.; Monusko, K.; Trivedi, H.; Wu, W.; Toll, R.; Buckwalter, M.S.; et al. Mapping causal circuit dynamics in stroke using simultaneous electroencephalography and transcranial magnetic stimulation. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambreen, H.; Tariq, H.; Amjad, I. Effects of bilateral arm training on upper extremity function in right and left hemispheric stroke. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprile, I.; Guardati, G.; Cipollini, V.; Papadopoulou, D.; Monteleone, S.; Redolfi, A.; Garattini, R.; Sacella, G.; Noro, F.; Galeri, S.; et al. Influence of cognitive impairment on the recovery of subjects with subacute stroke undergoing upper limb robotic rehabilitation. Brain Sciences 2021, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krabben, T.; Prange, G.B.; Molier, B.I.; Stienen, A.H.; Jannink, M.J.; Buurke, J.H.; Rietman, J.S. Influence of gravity compensation training on synergistic movement patterns of the upper extremity after stroke, a pilot study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, T.; Xing, Z.; Li, Q.; Li, Q. Case report: Virtual reality-based arm and leg cycling combined with transcutaneous electrical spinal cord stimulation for early treatment of a cervical spinal cord injured patient. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1380467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutai, H.; Furukawa, T.; Araki, K.; Misawa, K.; Hanihara, T. Factors associated with functional recovery and home discharge in stroke patients admitted to a convalescent rehabilitation ward. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 2012, 12, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Szaflarski, J.P.; Eliassen, J.C.; Pan, H.; Cramer, S.C. Cortical plasticity following motor skill learning during mental practice in stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2009, 23, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calautti, C.; Baron, J.-C. Functional neuroimaging studies of motor recovery after stroke in adults: A review. Stroke 2003, 34, 1553–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresser, L.P.; Kohn, M.A. Artificial intelligence and the evaluation and treatment of stroke. Delaware Journal of Public Health 2023, 9, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, S. Technological advancements in neurorehabilitation. The Rehabilitation Journal 2019, 3, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyai, A.D.; Brișan, C. Robotics in physical rehabilitation: Systematic review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasada, S.; Tazoe, T.; Nakajima, T.; Futatsubashi, G.; Ohtsuka, H.; Suzuki, S.; Zehr, E.P.; Komiyama, T. A common neural element receiving rhythmic arm and leg activity as assessed by reflex modulation in arm muscles. J. Neurophysiol. 2016, 115, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thant, A.A.; Wanpen, S.; Nualnetr, N.; Puntumetakul, R.; Chatchawan, U.; Hla, K.M.; Khin, M.T. Effects of task-oriented training on upper extremity functional performance in patients with sub-acute stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2019, 31, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balter, J.E.; Zehr, E.P. Neural coupling between the arms and legs during rhythmic locomotor-like cycling movement. J. Neurophysiol. 2007, 97, 1809–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumru, H.; Flores, Á.; Rodríguez-Cañón, M.; Edgerton, V.R.; García, L.; Benito-Penalva, J.; Navarro, X.; Gerasimenko, Y.; García-Alías, G.; Vidal, J. Cervical electrical neuromodulation effectively enhances hand motor output in healthy subjects by engaging a use-dependent intervention. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salse-Batán, J.; Sanchez-Lastra, M.A.; Suarez-Iglesias, D.; Varela, S.; Ayán, C. Effects of nordic walking in people with parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health & Social Care in the Community 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, V. Quadrupedal coordination of bipedal gait: Implications for movement disorders. J. Neurol. 2011, 258, 1406–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxton, J.D.; Prins, P.J.; Miller, M.G.; Moreno, A.; Welton, G.L.; Atwell, A.D.; Talampas, T.R.; Elsey, G.E. The effects of a novel quadrupedal movement training program on functional movement, range of motion, muscular strength, and endurance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 2186–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, A.C. Quadrupedal movement training: A brief review and practical guide. ACSM’S Health & Fitness Journal 2023, 27, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhennoufa, I.; Zhai, X.; Utti, V.; Jackson, J.; McDonald-Maier, K.D. Wearable sensors and machine learning in post-stroke rehabilitation assessment: A systematic review. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 71, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrassé, N.; Proietti, T.; Crocher, V.; Robertson, J.; Sahbani, A.; Morel, G.; Roby-Brami, A. Robotic exoskeletons: A perspective for the rehabilitation of arm coordination in stroke patients. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoykov, M.E.; Corcos, D.M.; Madhavan, S. Movement-based priming: Clinical applications and neural mechanisms. Journal of Motor Behavior 2017, 49, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.-w.; Wu, C.-y.; Wang, W.-e.; Lin, K.-c.; Chang, K.-c.; Chen, C.-c.; Liu, C.-t. Bilateral robotic priming before task-oriented approach in subacute stroke rehabilitation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Xiong, C.-H.; Chen, Z.-J.; Fan, W.; Huang, X.-L. Postural synergy-based exoskeleton reproducing natural human movements to improve upper limb motor control after stroke. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Z.F.; Damiano, D.L.; Bulea, T.C. A lower-extremity exoskeleton improves knee extension in children with crouch gait from cerebral palsy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaam9145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehr, E.P.; Duysens, J. Regulation of arm and leg movement during human locomotion. Neuroscientist 2004, 10, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elftman, H.O. The function of the arms in walking. Hum. Biol. 1939, 11, 529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, N.; Nozaki, D.; Abe, M.O.; Nakazawa, K. Shaping appropriate locomotive motor output through interlimb neural pathway within spinal cord in humans. J. Neurophysiol. 2008, 99, 2946–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Son, K.J.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.S. Effect of the frequency of rehabilitation treatments on the long-term mortality of stroke survivors with mild-to-moderate disabilities under the korean national health insurance service system. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzi, Y.; Zehr, E.P. Rhythmic arm cycling suppresses hyperactive soleus h-reflex amplitude after stroke. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerbeek, J.M.; Langbroek-Amersfoort, A.C.; Van Wegen, E.E.H.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Kwakkel, G. Effects of robot-assisted therapy for the upper limb after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2017, 31, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudo, R.J.; Wise, B.M.; SiFuentes, F.; Milliken, G.W. Neural substrates for the effects of rehabilitative training on motor recovery after ischemic infarct. Science 1996, 272, 1791–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyne, P.; Billinger, S.A.; Reisman, D.S.; Awosika, O.O.; Buckley, S.; Burson, J.; Carl, D.; DeLange, M.; Doren, S.; Earnest, M.; et al. Optimal intensity and duration of walking rehabilitation in patients with chronic stroke: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurology 2023, 80, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formaggio, E.; Storti, S.F.; Boscolo Galazzo, I.; Gandolfi, M.; Geroin, C.; Smania, N.; Spezia, L.; Waldner, A.; Fiaschi, A.; Manganotti, P. Modulation of event-related desynchronization in robot-assisted hand performance: Brain oscillatory changes in active, passive and imagined movements. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2013, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjellesvik, T.I.; Becker, F.; Tjønna, A.E.; Indredavik, B.; Lundgaard, E.; Solbakken, H.; Brurok, B.; Tørhaug, T.; Lydersen, S.; Askim, T. Effects of high-intensity interval training after stroke (the hiit stroke study) on physical and cognitive function: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R. Muscle strength and muscle training after stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 2007, 39, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Definition | Relevance | Authors/Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral Movement Training (BMT) | Bilateral movement training in post-stroke rehabilitation involves the simultaneous use of both limbs to perform tasks, promoting coordination and functional recovery. | This method leverages the concept of neural plasticity, facilitating the reorganization of the brain’s neural networks to improve motor function in the affected limb. | Cauraugh, J. H., & Summers, J. J. Neural plasticity and bilateral movements: A rehabilitation approach for chronic stroke. Progress in Neurobiology, 75(5), 309–320. [27] |

| Interlimb Coupling | Interlimb coupling in stroke rehabilitation refers to the coordination between the movements of both limbs, which can influence motor recovery and functional performance. | Interlimb coupling exercises aim to exploit neural mechanisms that link the movements of the limbs, thereby facilitating the recovery of motor function in the affected limb through synchronized bilateral activities. | Schaefer, S. Y., & Lang, C. E. Using dual tasks to test immediate transfer of training between naturalistic movements: a proof-of-principle study. Journal of Motor Behavior, 44(5), 313–318. [31] |

| Interlimb Transfer | Interlimb transfer in stroke rehabilitation refers to the phenomenon where training or practicing a motor skill with one limb improves the performance of the same skill with the untrained contralateral limb. | This allows therapists to leverage the unaffected limb to enhance motor recovery in the affected limb(s). | Cauraugh, J. H., Kim, S. Two coupled motor recovery protocols are better than one: Electromyogram-triggered neuromuscular stimulation and bilateral movements. Stroke, 33(6). [32] |

| Cross Education | Cross-education in post-stroke rehabilitation refers to the phenomenon where strength training of one limb can lead to strength gains in the contralateral, untrained limb. | This effect is particularly beneficial in stroke rehabilitation, as exercising the unaffected limb can help improve strength and function in the affected limb, aiding overall recovery. | Farthing, J. P., & Zehr, E. P. Restoring symmetry: Clinical applications of cross-education. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 42(2), 70–75. [5] |

| Bilateral Synergy | Bilateral synergy in post-stroke rehabilitation refers to the coordinated and simultaneous use of both limbs to enhance motor recovery and functional performance. | This concept leverages the interconnectedness of the hemispheres in the brain, encouraging the non-affected limb to assist in rehabilitating the affected limb, thereby improving overall motor function and reducing asymmetry in movement patterns. | Lewis, G. N., & Perreault, E. J. The side of stroke affects interlimb coordination during passive movement. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 21(4), 280–285. [33] |

| Interlimb Connections | Interlimb connections in post-stroke rehabilitation refer to the neural pathways and mechanisms that facilitate communication and coordination between the limbs. Function. | Interlimb connections are crucial for motor recovery. They enable the unaffected limb to support the rehabilitation of the affected limb by promoting symmetrical movement patterns and improving overall motor function and recovery. | Cauraugh, J. H., & Summers, J. J. Neural plasticity and bilateral movements: A rehabilitation approach for chronic stroke. Progress in Neurobiology, 75(5), 309–320. [27] |

| Central Pattern Generators (CPG) | Central pattern generators (CPGs) in stroke rehabilitation refer to neural networks in the spinal cord that can produce rhythmic patterned outputs, such as walking or other repetitive movements, without sensory feedback. | These neural circuits facilitate motor recovery by enabling rhythmic and coordinated movement patterns. Therapeutic interventions can harness and retrain these patterns to improve functional mobility in stroke patients. | Dietz, V. Spinal cord pattern generators for locomotion. Clinical Neurophysiology, 114(8), 1379–1389. [23] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).