Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

04 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Vaccines are biological products that contain antigens capable of inducing specific and active immunity against an infectious agent or the toxin produced by some pathogens. For over a century, passive immunotherapy with polyclonal antibodies has been em-ployed in the treatment and post-exposure prophylaxis against various microorgan-isms and toxins. This study aims to evaluate the quantity and types of antigens and sera distributed by the National Immunization Program (NIP) and to analyze both the duration and challenges associated with technology transfer in vaccine production within Brazil. Furthermore, it assesses the impact of ongoing technology transfers. Methods: The study collected data from official systems for information on vaccine lots and their origin from 2014 to 2024, as well as the production stages in which pharmaceutical laboratories were certified by the national regulatory authority. Re-sults: Out of the 25 antigens provided by the NIP, 4 are produced using biotechnology methods, while the remaining 21 utilize conventional technology. The process of tech-nology transfer to Brazilian manufacturers takes between 3 to 15 years. Moreover, public laboratories still face challenges regarding physical infrastructure and acquir-ing the necessary qualifications certificates for production. Conclusions: Technology transfer in vaccine production is a high-risk endeavor that requires long-term plan-ning and investment. The ongoing technology transfers in Brazil have contributed to the NIP, but challenges remain in terms of infrastructure and qualifications. Ongoing advancements in technology are essential to remain aligned with progress.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Vaccines

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID | Corona Virus Desease |

| rDNA | Recombinant Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| PAHO | Pan American Health Organization |

| NSPI | National Self-Sufficiency Program in Immunobiologicals |

| PDPs | Productive Development Partnerships |

| TOCs | Technical Operating Conditions |

| MMRV | Measles, Mumps, Rubella and Varicella |

| INIP | Imported by Nacional Immunization Program |

| DTwP-HepB-Hib | Diphtheria, Tetanus, whole-cell Pertussis, Hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b |

| NIP | National Immunization Program |

| LNP | Lipid Nanoparticle |

| NRA | National Regulatory Authority |

| DTP | Diphtheria, Tetanus and Pertussis |

| Hib | Haemophilus influenzae |

| MMR | Measles, Mumps and Rubella |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practices |

| RFV | Revolving Fund for Vaccines |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| BCG | Bacilo de Calmette-Guérin |

| BMA | Brazilian Manufacturer A |

| BMB | Brazilian Manufacturer B |

| BMC | Brazilian Manufacturer C |

| BMD | Brazilian Manufacturer D |

| BME | Brazilian Manufacturer E |

| BMF | Brazilian Manufacturer F |

| BMG | Brazilian Manufacturer G |

| BMH | Brazilian Manufacturer H |

| dT | reduced diphtheria and Tetanus antigen |

References

- Anvisa. Dispõe sobre o registro de produtos biológicos novos e produtos biológicos. Resolução da Diretoria colegiada nº 55, 2010.

- Strugnell, R; Zepp, F.; Cunningham, A.; Tantawichien, T. Vaccines Antigens. Chapter 3. In Understanding Modern Vaccines: Perspectives in Vaccinology; Garçon N., Stern, P.L., Cunningham, A.L., Eds.; Elsevier B.V., 2011; Volume 1, pp. 61-88.

- European Pharmacopoeia. Monograph 0153. Vaccines for human use. In Ph.Eur., 11th Ed.; European Department for the Quality of Medicines within the Council of Europe, Strasbourg, France, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 952-955.

- Greenwood, B. The Contribution of Vaccination to Global Health: Past, Present and future. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2014, 369. [CrossRef]

- Amanna, I.J.; Slifka, M.K. Successful Vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2020, 428, pp. 1–30.

- United States Pharmacopoeia. Monography 1235. Vaccines for human use-General Considerations, 2023.

- World Health Organization. A Brief History of Vaccination. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/a-brief-history-of-vaccination?topicsurvey=ht7j2q)&gclid=CjwKCAjw1YCkBhAOEiwA5aN4AVQ_6RCpU_-K83mkDaPh03iNbcRKfo8wjzPpyG-DRNNjzF3KcKETzRoC1d0QAvD_BwE. (Accessed on 7 june 2024).

- Anvisa. Dispõe sobre a aprovação da Farmacopeia Brasileira 6ª edição. Resolução da Diretoria colegiada nº 298, 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/farmacopeia/farmacopeia-brasileira (Accessed on 7 june 2024).

- Josefsberg, J.O.; Buckland B. Vaccine process technology. Biotechnology&Bioengineering. 2012, 109 (6), pp. 1443-1460.

- Kallon, S.; Shahryar, S.; Goonetilleke, N. Vaccines: Underlying Principles of Design and Testing. Clinical Pharmacology & Theapeutics. 2021, 109(4), pp.997-999. [CrossRef]

- Alcolea, P.J.; Alonso, A.; Larraga, V. The Antibiotic Resistance-Free Mammalian Expression Plasmid Vector PPAL for Development of Third Generation. Vaccines. 2019, 101, pp. 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Alcolea, P.J.; Larraga, J.; Rodríguez-Martín, D.; Alonso, A.; Loayza, F.J.; Rojas, J.M.; Ruiz-García, S.; Louloudes-Lázaro, A.; Carlón, A.B.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J. Non-Replicative Antibiotic Resistance-Free DNA Vaccine Encoding S and N Proteins Induces Full Protection in Mice against SARS-CoV-2. Front. Immunol., 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Y.K.; Mohammed, A.; Khalid, A.; Ishtiaq, Q. Biotechnology and Its Applications in Vaccine Development. Biomed J Sci& Tech Res. 2021, 37(1), pp. 29114-16.

- Sahin, U.; Karikó, K.; Türeci, O. mRNA-based therapeutics — developing a new class of drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2014, 13, pp. 759–780. [CrossRef]

- Kirtane, A.R.; Verma, M.; Karandikar, P.; Furin, J.; Langer R, Traverso, G. Nanotechnology Approaches for Global Infectious Diseases. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, pp. 369–384. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.E; Titball, R.; Williamson, D. Vaccine Delivery Using Nanoparticles. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 3, pp.13.

- Zhao, L.; Seth, A.; Wibowo, N.; Zhao, C.X.; Mitter, N.; Yu, C.Z.; Middelberg, A.P.J. Nanoparticle Vaccines. Vaccine 2014, 32, pp. 327–337.

- Lozano, D.; Larraga, V.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Manzano, M.N. A Overview of the Use of Nanoparticles in Vaccine Development. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, pp. 1828. [CrossRef]

- Strohl, W.R.; Knight, D.M. Discovery and development of biopharmaceuticals: current issues. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009, 20(6), pp. 668–72. [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.D.; Gaudet, R.G. Antibodies in infectious diseases: polyclonals, monoclonals and niche biotechnology. N Biotechnol. 2011, 28 (5), pp. 489–501. [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia. Monograph 0084. Immunoserum for human use, animal. In Ph.Eur., 11th Ed.; European Department for the Quality of Medicines within the Council of Europe, Strasbourg, France, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 929-932.

- Casadevall, A.; Dadachova, E.; Pirofski, L.A. Passive antibody therapy for infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004, 2(9), pp. 695–703. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the production, control and regulation of snake antivenom. WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization: sixty-seventh report. WHO Technical Report Series, 1004. Annex 5. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017.

- Da Silva Junior, J.B. ‘40 anos do programa nacional de imunizações: uma conquista da saúde pública brasileira’. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 2013, 22(1), pp. 7–8.

- Domingues, C.A.S.; Maranhão, A.G.K.; Teixeira, A.M.; Fantinato, F.F.S.; Domingues, R.A. 46 anos do Programa Nacional de Imunizações: uma história repleta de conquistas e desafios a serem superados. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36 (2), pp. 1-17.

- Dourado, I. Cinco décadas do Programa Nacional de Imunizações (PNI). Correio Braziliense, 2023. Available online: https://sindusfarma.org.br/noticias/indice/exibir/20988-cinco-decadas-do-programa-nacional-de-imunizacoes-pni. (Accessed on 7 november 2024).

- Brasil. Manual de Normas e Procedimentos para Vacinação. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Vigilância das Doenças Transmissíveis. Brasília, 2014. 176 p.

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/campanhas-da-saude/2022/calendario-nacional-de-vacinacao/calendario-nacional-de-vacinacao.pdf/ (Accessed on 20 january 2024).

- Brasil. Manual dos centros de referência para imunobiológicos especiais. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Imunização e Doenças Transmissíveis. 5th ed., Brasília, 2019.

- Brasil. Define o Sistema Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, cria a Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, e dá outras providências. Lei 9.782. January 1999.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for national authorities on quality assurance for biological products. WHO Technical Report Series 822. Annex 2, 1992.

- World Health Organization. WHO good manufacturing practices for biological products. WHO Technical Report Series 999. Annex 2, 2016.

- European Comission – EU. Guidelines for good manufacturing practice for medicinal products for human and veterinary use. Brussels: European Comission; 2012. (Available online: https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/vol4-chap1_2013-01_en_0.pdf (Accessed on 20 january 2024.

- World Health Organizatio. WHO guideline on the implementation of quality management systems for national regulatory authorities. WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations: fifty fourth report. WHO Technical Report Series 1025. Annex 13, Geneva, 2020. (Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-000182-4. (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- World Health Organization. Good regulatory practices in the regulation of medical WHO. Technical Report Series 1033, 2021.

- Anvisa. Dispõe sobre as Diretrizes Gerais de Boas Práticas de Fabricação de Medicamentos. Resolução RDC Nº 658, 2022.

- Brasil. Programa nacional de imunizações - 30 anos. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Brasília, 2003.

- PAHO. (Available online: https://www.paho.org/pt/fundo-rotatorio. (Accessed on 20 january 2024).

- Gadelha, C.A.B. Desenvolvimento tecnológico: elo deficiente na inovação tecnológica de vacinas no Brasil. Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos 2003, 10 (suppl 2).

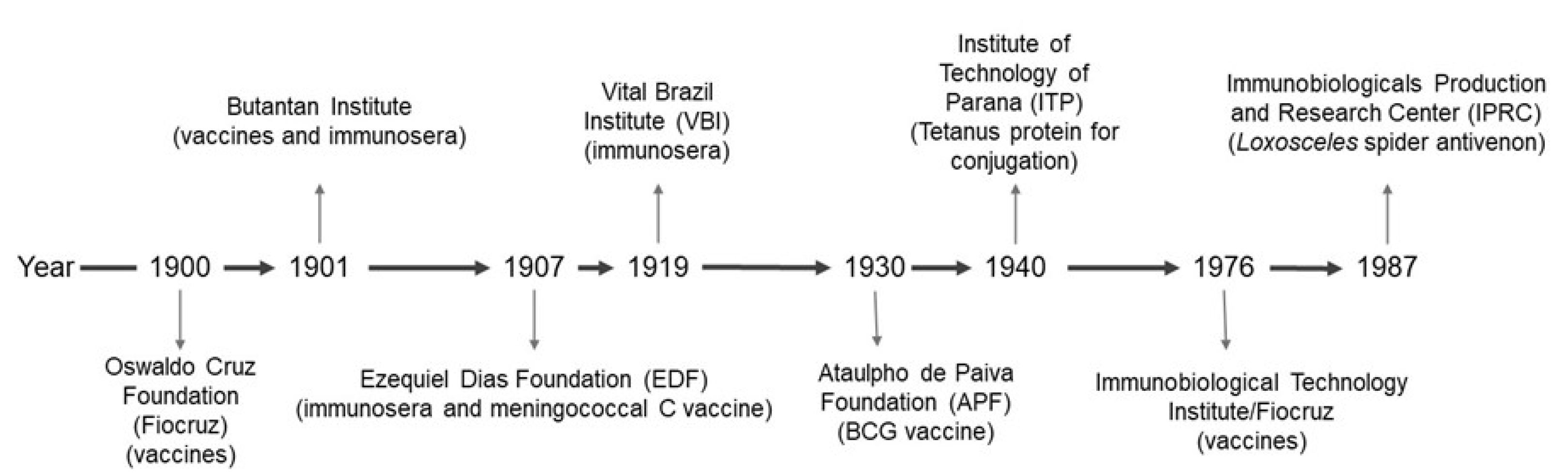

- Homma, A.; Martins, R.M.; Jessouroum, E.; Oliva, O. Desenvolvimento tecnológico: elo deficiente na inovação tecnológica de vacinas no Brasil. Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos 2003, 10 (2), pp. 671-96. [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, C.; Temporão, J.G. A indústria de vacinas no Brasil: desafios e perspectivas. BNDES conference, 1999.

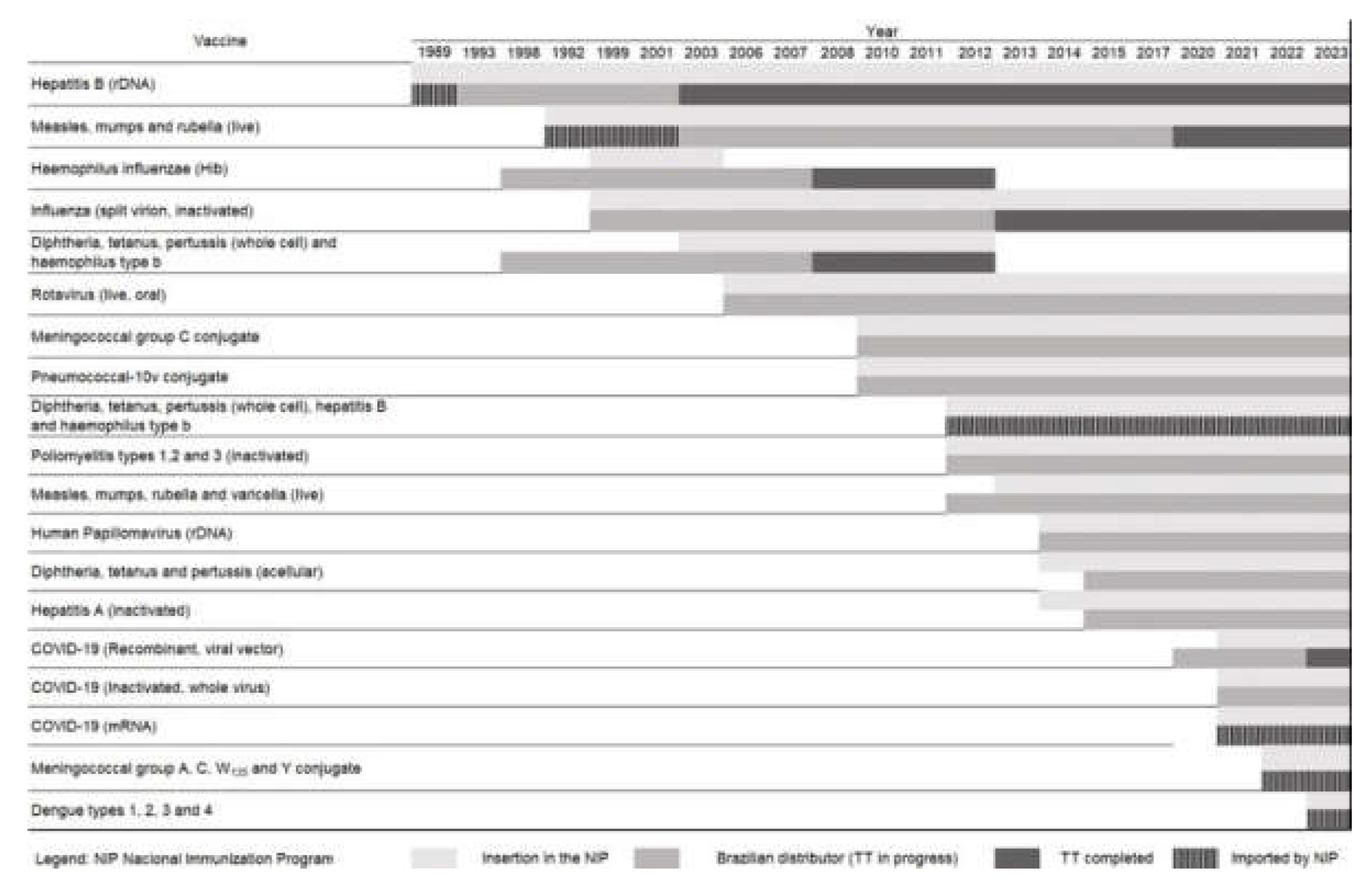

- Domingues, C.A.S.; Woycicki, J.R.; Rezende, K.S.; Henriques, C.M.P. Programa Nacional de Imunização: a política de introdução de novas vacinas. Revista Eletronica Gestão & Saúde 2015, 6, pp. 3250-74.

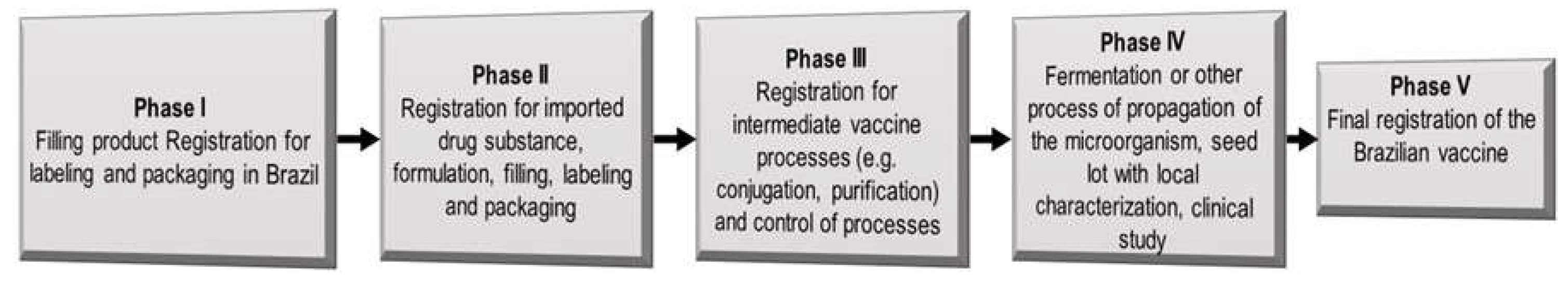

- Homma, A.; Moreira, M. New challenges for national capability in vaccine technology: domestic technological innovation versus technology transfer. Cadernos de Saúde Pública 2008, 24(2), pp. 238-9.

- World Health Organization. Increasing access to vaccines through technology transfer and local production. Vaccine technology transfer in a global health crisis. World Health Organization, 2011.

- Moreira, M. PDP: uma solução que não pode ser única. Notícias e Artigos, 2017. (Available online: https://www.bio.fiocruz.br/index.php/br/noticias/1533-pdp-uma-solucao-que-nao-pode-ser-unica. (Accessed on 20 january 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on technology transfer in pharmaceutical manufacturing. WHO Technical Report Series 1044, Annex 4, 2022.

- Andrade, A. Avaliação e controle de riscos à qualidade nas operações de embalagem secundária da vacina rotavírus humano G1 P[8] (atenuada) unidose, Master's degree, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, 2015.

- Portes, J.V.A. O processo de transferência internacional de tecnologia no setor de imunobiológicos: um estudo de caso, Master's degree, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2012.

- Luzia, A.B. Transferência de tecnologia e parceria para o desenvolvimento produtivo no setor de biotecnologia: um estudo de caso na Fundação Ezequiel Dias, Master's degree, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2015.

- Cruz, M.V.O. Gerenciamento de processos na gestão de contratos de transferência de tecnologia da produção de vacinas virais: Estudo de caso da vacina contra rotavírus humano G1 P[8] (atenuada), Master's degree, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, 2018.

- Brasil. (Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/leiturajornal. (Accessed from 10 january 2023 to November 2024).

- Anvisa. (Available online: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/medicamentos/. (Accessed from 10 january 2023 to November 2024).

- Brasil. Guia de Vigilância em Saúde. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Articulação Estratégica de Vigilância em Saúde. 5th ed., Brasília, 2022. P.126.

- Homma, A.; Martins, R.; Leal M.L.; Freire, M.S.; Couto, A.R. Atualização em vacinas, imunizações e inovação tecnológica. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva 2011, 16(2), pp. 445–458.

- Sato, A.P.S. National Immunization Program: Computerized Systemas a tool for newchallenges. Revista de Saúde Pública 2015, 49, pp.1–5.

- Brasil. Resolução RE 3.403/2016. Federal Official Journal, July 4, 2022.

- Nascimento, L.F.; Queiroz Filho, A.P. Parceria de desenvolvimento produtivo da vacina influenza no instituto butantan: análise da origem da infraestrutura biotecnológica e dos componentes. Revista Brasileira de Geografia Médica e da Saúde 2017, 13 (25), pp. 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Luchese, M.D.; Bertolini, S.R.; Moro, A.M.; Laurentis, A.L. Dependência tecnológica na produção de imunobiológicos no Brasil: transferência de tecnologia versus pesquisa nacional. Universidade e sociedade. ANDES-SN 2017, 59, pp. 46-59.

- Homma, A.; Freire, M.S.; Possa, C. Vacinas para doenças negligenciadas e emergentes no Brasil até 2030: o “vale da morte” e oportunidades para PD&I na Vacinologia. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36 Sup 2.

- Greiner, M.A.; Franza, R.M. “Barriersand bridges for successful environmental Technology Transfer”. The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2003, 28 (2), pp.167-77. [CrossRef]

- Homma, A. The Brazilian vaccine manufacturers’ perspective and its current status. Biologicals 2009, 37 (3), pp. 173-6. [CrossRef]

- Gadelha, CAB.; Desenvolvimento, complexo industrial da saúde e política industrial. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2006; 40:11-23.

- Gutiérrez, J.M. Global Availability of Antivenoms: The Relevance of Public Manufacturing Laboratories. Toxins 2019, 11 (5), pp. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Aswathy, A.; Karthika, R.; Bipin, G.N. Snake antivenom: Challenges and alternate approaches. Review. Biochemical Pharmacology 2020, 181, 114-135.

- Vargas M, Segura A, Villalta M, Herrera M, Gutiérrez JM, León G. Purificationofequinewhole IgG snake antivenom by using an aqueous two-phase system as a primary purification step. Biologicals 2015, 43(Issue 1), pp. 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.S.Q. Avaliação da pureza de soros antiofídicos Brasileiros e Desenvolvimento de nova metodologia para essa finalidade, Master's degree, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, 2008.

| Types of antigens | Offered by NIP |

| Live attenuated bacteria or virus | BCG, oral rotavirus, yellow fever, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, oral poliomyelitis, dengue tetravalente |

| Inactivated bacteria or vírus | Influenza, pertussis, hepatitis A, rabies, whole virus Covid-19 and poliomyelitis |

| Inactivated toxins | Diphtheria and tetanus |

| Conjugated Polysaccharide to carrier protein | Meningococcal group C, pneumococcal 10- valent, Meningococcal group ACW135Y and haemophilus type b |

| - Recombinant technology through genetic modification in which the DNA encodes the antigen gene, using a vector (bacterial, yeast, viral, cells of human, insect or plant origin); - Antigenic proteins in nanoparticles (mRNA); - Viral vector |

Human papilomavírus (rDNA), hepatitis B (rDNA), covid-19 (viral vector) and covid-19 (mRNA) |

| Vaccine | INIP | TT completed | TT in progress | ||||

| BMA | BMB | BMC | BMB | BMC | BMD | ||

| BCG | 120 | 388 | - | - | - | - | - |

| COVID-19 (whole virus) | - | - | - | - | 439 | - | - |

| COVID-19 (viral vector) | 75 | - | - | 162 | - | 412 | - |

| COVID-19 (mRNA) | 239 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dengue types 1, 2, 3 and 4 | 283 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Diphtheria and tetanus (reduced antigen) | 232 | - | 15 | - | - | - | - |

| Diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (whole cell) | 147 | - | 6 | - | - | - | - |

| Diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (acellular) | 152 | - | - | - | 107 | - | - |

| Haemophilus influenza b | 20 | - | - | 4 | - | - | - |

| Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (whole cell), hepatitis B and haemophilus influenzae type b | 722 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hepatitis A | 38 | - | - | - | 162 | - | - |

| Hepatitis B (rDNA) | 118 | - | 111 | - | - | - | - |

| Human Papillomavírus (rDNA) | 42 | - | - | - | 702 | - | - |

| Influenza (split virion) | - | - | 767 | - | - | - | - |

| Measles, mumps and rubella | - | - | - | 1,010 | - | - | - |

| Measles, mumps, rubella and varicella | 71 | - | - | - | - | 201 | - |

| Meningococcal group C conjugate | - | - | - | - | - | - | 918 |

| Meningococcal group A, C, W135 and Y conjugate | 187 | - | - | - | - | 103 | - |

| Pneumococcal-10 valente conjugate | - | - | - | - | - | 1,233 | - |

| Poliomyelitis types 1 and 3 (oral) | - | - | - | 333 | - | - | - |

| Poliomyelitis types 1,2 and 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 196 | - |

| Rabies (cell culture) | 4 | - | 329 | - | - | - | - |

| Rotavirus (oral) | - | - | - | - | - | 576 | - |

| Varicella | 1,045 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yellow fever | - | - | - | 1,058 | - | - | - |

| Total | 3,495 | 388 | 1,228 | 2,567 | 1,410 | 2,721 | 918 |

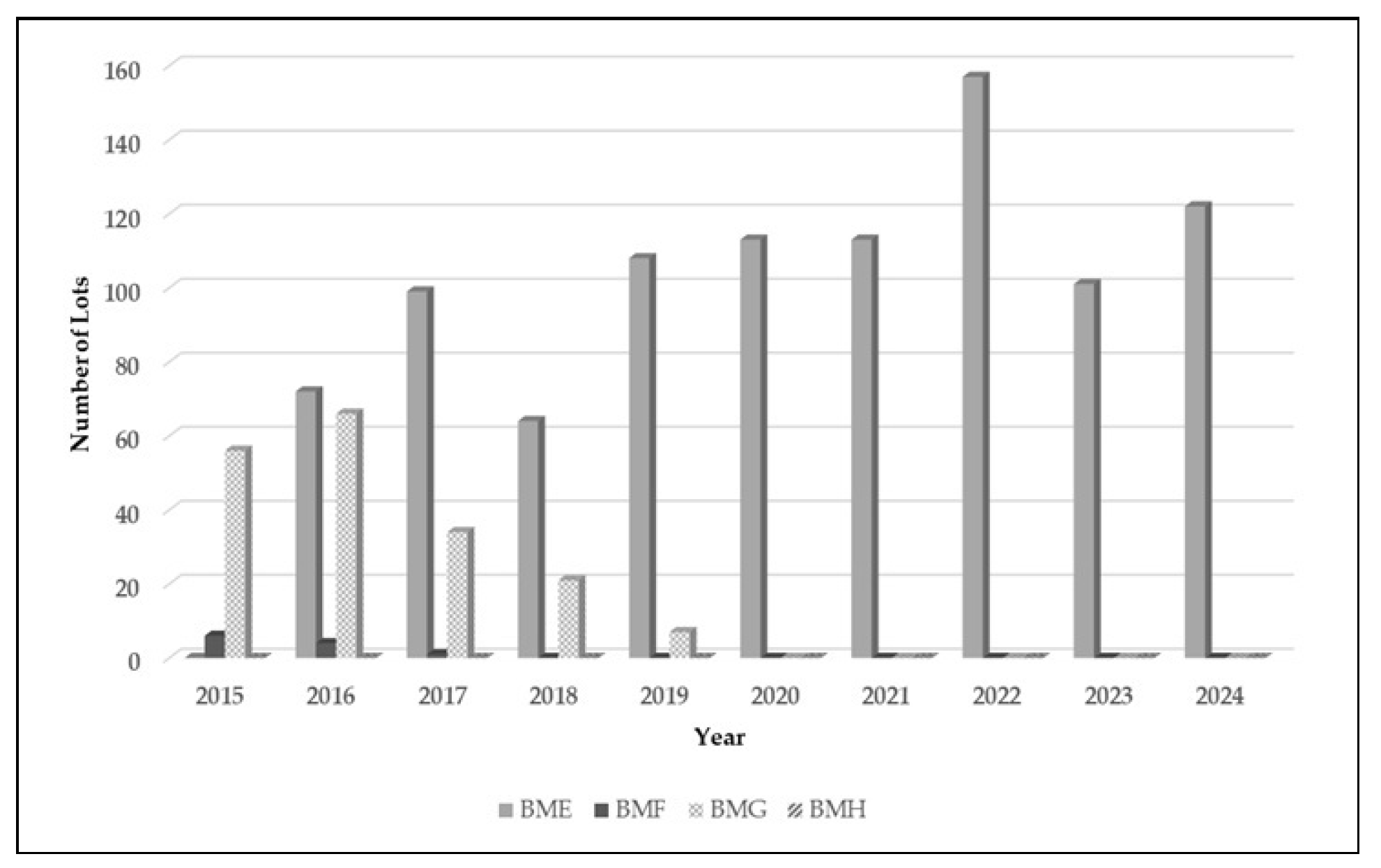

| Manufacturer | Heterologous immunoserum | Recommendation |

| BME | Anti arachnoid (trivalent) | Scorpions of the genus Tityus and spiders Phoneutria and Loxosceles. |

| Botulinum antitoxin | Eliminate circulating toxin and Clostridium botulinum. | |

| Diphtheria antitoxin | Treatment of diphtheria. There is no indication for the prevention of diphtheria in vaccinated individuals. | |

| Antilonomic | L. obliqua caterpillar. | |

| BME and BMF | Antielapidic (bivalent) | Snakes of the genus M. frontalis and M. corallinus. |

| BME/BMF/BMG | Antibotropic (pentavalent) | Snakes of the genus Bothrops: B. jararaca, B. jararacussu, B. moojeni, B. alternates and B. neuwiedi. |

| Antibotropic (pentavalent) and anticrothalic | Snakes of the genus Bothrops and Crotalus. | |

| Antibotropic (pentavalent) and antilaquetic | Snakes of the genus Bothrops and Lachesis muta. | |

| Anticrothalic | Snakes of the genus Crotalus. | |

| Antiscorpionic | Scorpions of the genus Tityus. | |

| Anti-rabies | Rabies virus exposure, depending on the nature of the exposure. | |

| Tetanus antitoxin | Treatment of tetanus depending on the number of doses of tetanus toxoid previously received. | |

| BMH | Antiloxoscelic (trivalent) | Accidents with spiders L. gaucho, L. intermedia e L. laeta. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).