Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

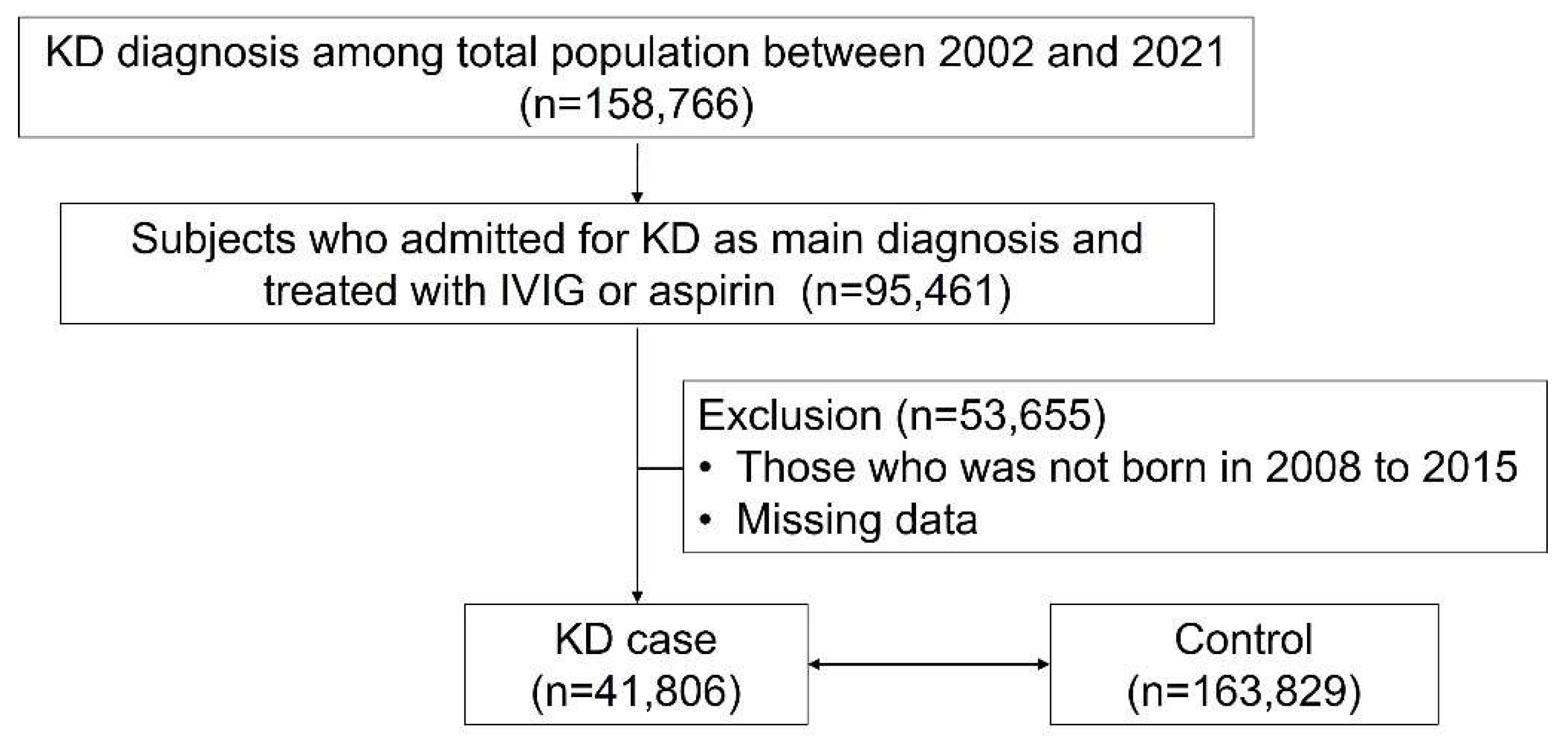

2.2. Study Design and Population

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics of Study Participants

3.2. Risk of Neuropsychiatric Disorders

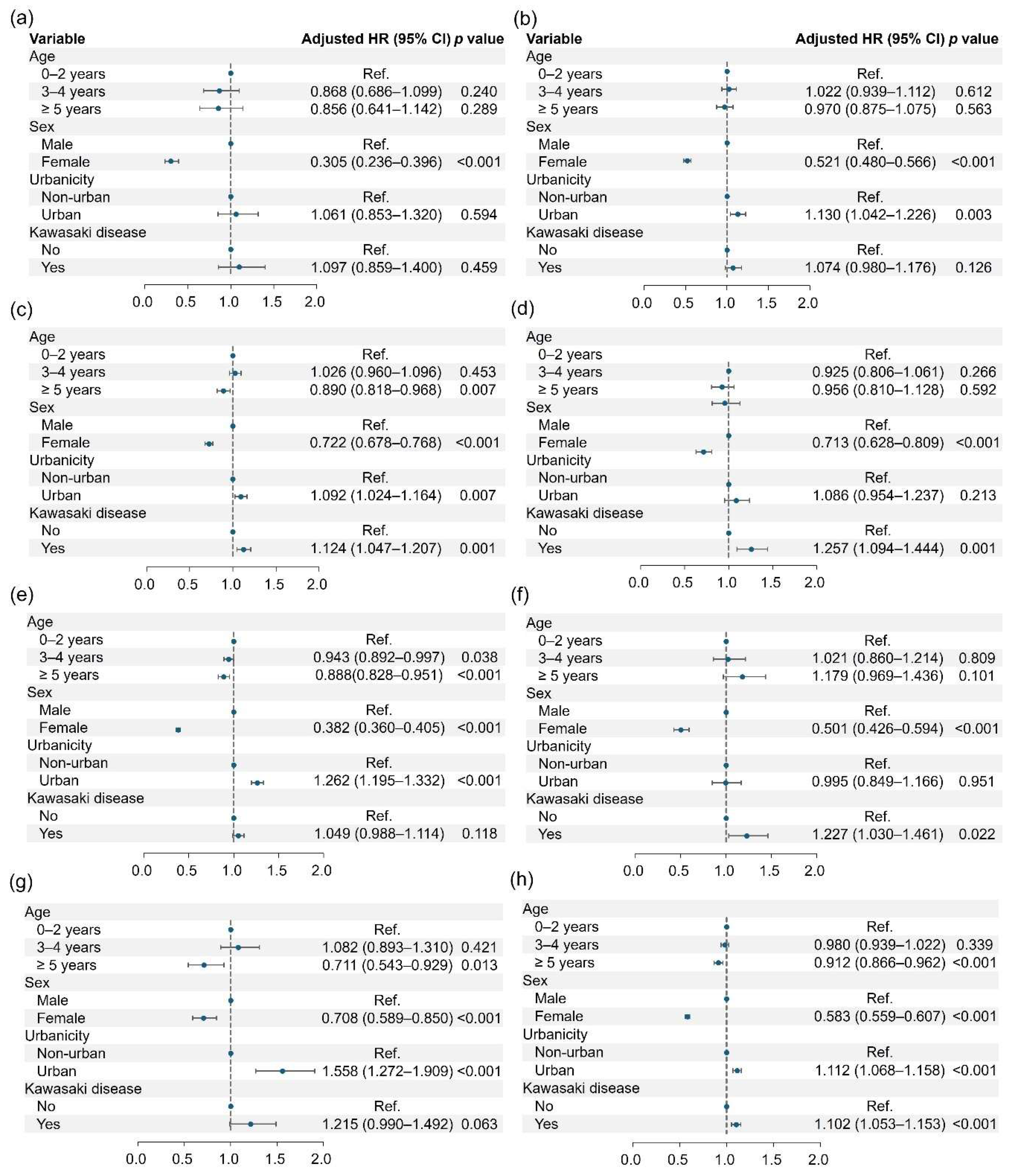

3.3. Risk of Neurodevelopment

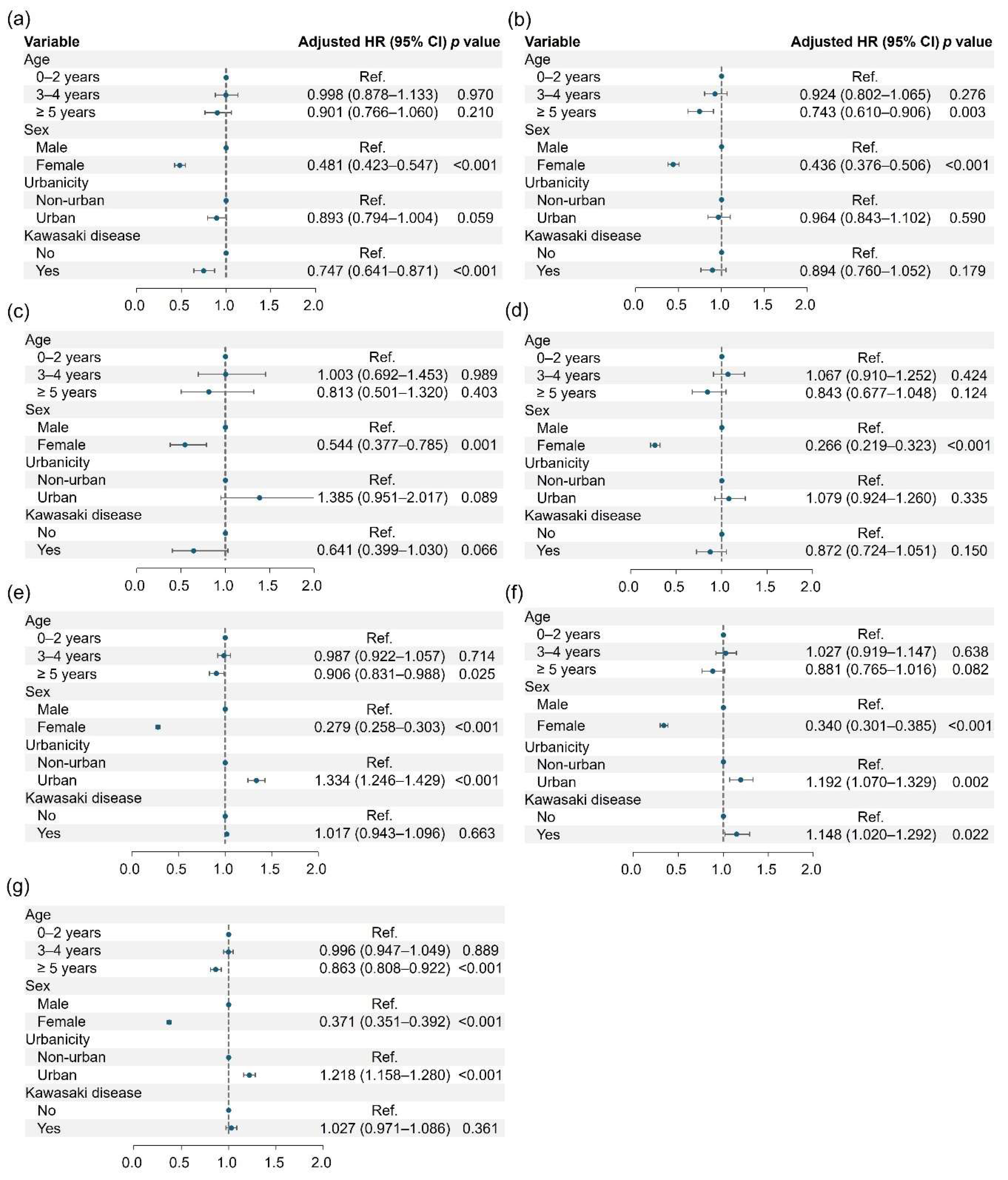

3.3. Risk of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KD | Kawasaki Disease |

| ADHD | Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| HR OR SPECT NHIS |

Hazard Ratio Odds Ratio Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography National Health Insurance Service |

References

- Kawasaki, T.; Kosaki, F.; Okawa, S.; Shigematsu, I.; Yanagawa, H. A new infantile acute febrile mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (MLNS) prevailing in Japan. Pediatrics 1974, 54, 271-276.

- Mauro, A.; Di Mari, C.; Casini, F.; Giani, T.; Sandini, M.; Biondi, L.; Calcaterra, V.; Zuccotti, G.V.; Bernardo, L. Neurological manifestations of Kawasaki disease and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with COVID-19: a comparison of two different clinical entities. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 1088773. [CrossRef]

- Ogihara, Y.; Ogata, S.; Nomoto, K.; Ebato, T.; Sato, K.; Kokubo, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Ishii, M. Transcriptional regulation by infliximab therapy in Kawasaki disease patients with immunoglobulin resistance. Pediatr. Res. 2014, 76, 287-293. [CrossRef]

- Ichiyama, T.; Nishikawa, M.; Hayashi, T.; Koga, M.; Tashiro, N.; Furukawa, S. Cerebral hypoperfusion during acute Kawasaki disease. Stroke 1998, 29, 1320-1321. [CrossRef]

- Sundquist, K.; Li, X.; Hemminki, K.; Sundquist, J. Subsequent risk of hospitalization for neuropsychiatric disorders in patients with rheumatic diseases: a nationwide study from Sweden. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 65, 501-507. [CrossRef]

- Benros, M.E.; Eaton, W.W.; Mortensen, P.B. The epidemiologic evidence linking autoimmune diseases and psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 300-306. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, W.W.; Byrne, M.; Ewald, H.; Mors, O.; Chen, C.Y.; Agerbo, E.; Mortensen, P.B. Association of schizophrenia and autoimmune diseases: linkage of Danish national registers. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 521-528. [CrossRef]

- Khandaker, G.M.; Zammit, S.; Lewis, G.; Jones, P.B. A population-based study of atopic disorders and inflammatory markers in childhood before psychotic experiences in adolescence. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 152, 139-145. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.T.; Chang, J.P.; Cheng, S.W.; Chang, H.C.; Hsu, J.H.; Chang, H.H.; Chiu, W.C.; Su, K.P. Kawasaki disease in childhood and psychiatric disorders: a population-based case-control prospective study in Taiwan. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 100, 105-111. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.; Lao, F.; Chanchlani, R.; Gayowsky, A.; Darling, E.; Batthish, M. Long-term hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes following Kawasaki disease: a population-based cohort study. Brain Dev. 2021, 43, 735-744. [CrossRef]

- Kambeitz, J.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Modelling the impact of environmental and social determinants on mental health using generative agents. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 36. [CrossRef]

- Werner, M.C.F.; Wirgenes, K.V.; Shadrin, A.; Lunding, S.H.; Rodevand, L.; Hjell, G.; Ormerod, M.; Haram, M.; Agartz, I.; Djurovic, S., et al. Immune marker levels in severe mental disorders: associations with polygenic risk scores of related mental phenotypes and psoriasis. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 38. [CrossRef]

- Cheol Seong, S.; Kim, Y.Y.; Khang, Y.H.; Heon Park, J.; Kang, H.J.; Lee, H.; Do, C.H.; Song, J.S.; Hyon Bang, J.; Ha, S., et al. Data resource profile: the national health information database of the National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 799-800. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Cho, Y.J.; Yun, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Yu, J.; Yang, H.J.; Suh, D.I.; Korean childhood Asthma, REsearch team. Leukotriene receptor antagonists and risk of neuropsychiatric events in children, adolescents and young adults: a self-controlled case series. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2102467. [CrossRef]

- Straub, L.; Bateman, B.T.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; York, C.; Zhu, Y.; Suarez, E.A.; Lester, B.; Gonzalez, L.; Hanson, R.; Hildebrandt, C., et al. Validity of claims-based algorithms to identify neurodevelopmental disorders in children. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2021, 30, 1635-1642. [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Tang, H.; Ding, Y. Kawasaki disease involving both the nervous system and cardiovascular system: a case report and literature review. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1459143. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Lai, J.N.; Lee, I.C.; Chou, I.C.; Lin, W.D.; Lin, M.C.; Hong, S.Y. Kawasaki disease may increase the risk of subsequent cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 2022, 53, 1256-1262. [CrossRef]

- Correction to: Update on diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2025, 151, e677-e679. [CrossRef]

- Lersch, R.; Mandilaras, G.; Schrader, M.; Anselmino, F.; Haas, N.A.; Jakob, A. Have we got the optimal treatment for refractory Kawasaki disease in very young infants? A case report and literature review. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1210940. [CrossRef]

- Takekoshi, N.; Kitano, N.; Takeuchi, T.; Suenaga, T.; Kakimoto, N.; Suzuki, T.; Kada, T.T.; Shibuta, S.; Tachibana, S.; Murayama, Y., et al. Analysis of age, sex, lack of Response to intravenous immunoglobulin, and development of coronary artery abnormalities in children with Kawasaki disease in Japan. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2216642. [CrossRef]

- Weiser, M.J.; Butt, C.M.; Mohajeri, M.H. Docosahexaenoic acid and cognition throughout the lifespan. Nutrients 2016, 8, 99. [CrossRef]

- Rowley, A.H.; Shulman, S.T. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of Kawasaki disease. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 374. [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Su, Z.; Wang, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, S.; Li, Y. Immune regulation based on sex differences in ischemic stroke pathology. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1087815. [CrossRef]

- Engemann, K.; Pedersen, C.B.; Arge, L.; Tsirogiannis, C.; Mortensen, P.B.; Svenning, J.C. Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 5188-5193. [CrossRef]

- Vassos, E.; Agerbo, E.; Mors, O.; Pedersen, C.B. Urban-rural differences in incidence rates of psychiatric disorders in Denmark. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 208, 435-440. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.M.; Cowan, M.; Moonah, S.N.; Petri, W.A., Jr. The impact of systemic inflammation on neurodevelopment. Trends Mol. Med. 2018, 24, 794-804. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, B.C.; Beltrao-Braga, P.C.B.; Marchetto, M.C. Modeling inflammation on neurodevelopmental disorders using pluripotent stem cells. Adv. Neurobiol. 2020, 25, 207-218. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.E.; Teixeira, A.L. Inflammation in psychiatric disorders: what comes first? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1437, 57-67. [CrossRef]

- Korematsu, S.; Uchiyama, S.; Miyahara, H.; Nagakura, T.; Okazaki, N.; Kawano, T.; Kojo, M.; Izumi, T. The characterization of cerebrospinal fluid and serum cytokines in patients with Kawasaki disease. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2007, 26, 750-753. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yue, Y.; Wang, L.; Deng, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yuan, Z.; Tan, C.; Cao, Y. Altered gut microbiota correlated with systemic inflammation in children with Kawasaki disease. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14525. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Zeng, M.Y.; Nunez, G. The interplay between host immune cells and gut microbiota in chronic inflammatory diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e339. [CrossRef]

- Ouabbou, S.; He, Y.; Butler, K.; Tsuang, M. Inflammation in mental disorders: is the microbiota the missing link? Neurosci. Bull. 2020, 36, 1071-1084. [CrossRef]

- Beroun, A.; Mitra, S.; Michaluk, P.; Pijet, B.; Stefaniuk, M.; Kaczmarek, L. MMPs in learning and memory and neuropsychiatric disorders. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3207-3228. [CrossRef]

- Carrizzo, A.; Lenzi, P.; Procaccini, C.; Damato, A.; Biagioni, F.; Ambrosio, M.; Amodio, G.; Remondelli, P.; Del Giudice, C.; Izzo, R., et al. Pentraxin 3 induces vascular endothelial dysfunction through a P-selectin/matrix metalloproteinase-1 pathway. Circulation 2015, 131, 1495-1505, discussion 1505. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.A.; Shin, K.S.; Kim, Y.W. Polymorphism of matrix metalloproteinase-3 promoter gene as a risk factor for coronary artery lesions in Kawasaki disease. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2005, 20, 607-611. [CrossRef]

- Small, C.D.; Crawford, B.D. Matrix metalloproteinases in neural development: a phylogenetically diverse perspective. Neural Regen. Res. 2016, 11, 357-362. [CrossRef]

| Variables | KD cases (n = 41,806) |

Controls (n = 163,829) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (years) | 2.63 ± 1.84 | 2.64 ± 1.85 | 0.119 |

| ≤ 2 years | 22,038 (52.71) | 85,992 (52.49) | 0.225 |

| 3–4 years | 13,376 (32.00) | 52,226 (31.88) | |

| ≥ 5 years | 6,392 (15.29) | 25,611 (15.63) | |

| Sex (female) | 17,643 (42.20) | 69,709 (42.55) | 0.199 |

| Urbanicity | 0.025 | ||

| Urban | 28,054 (67.11) | 108,991 (66.53) | |

| Non-urban | 13,752 (32.89) | 54,838 (33.47) |

| Kawasaki disease | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case (n, %) | No | Yes | HR (95% CI) |

p | HR (95% CI) |

p |

| Psychotic disorder (-) | 163,536 (95.82) | 41,722 (99.80) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Psychotic disorder (+) | 293 (0.18) |

84 (0.20) |

1.096 (0.859–1.400) |

0.459 | 1.097 (0.859–1.400) |

0.459 |

| Mood disorder (-) |

161,639 (98.66) |

41,218 (98.59) |

1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Mood disorder (+) |

2,190 (1.34) |

588 (1.41) |

1.068 (0.975–1.170) |

0.156 | 1.074 (0.980–1.176) |

0.126 |

| Anxiety disorder (-) |

160,403 (97.91) |

40,835 (97.68) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Anxiety disorder (+) |

3,426 (2.09) |

971 (2.32) | 1.124 (1.046–1.207) |

0.001 | 1.124 (1.047–1.207) |

0.001 |

| Sleep-related disorder (-) | 163,027 (99.51) | 41,539 (99.36) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Sleep-related disorder (+) | 802 (0.49) |

267 (0.64) | 1.254 (1.091–1.441) |

0.001 | 1.257 (1.094–1.444) |

0.001 |

| Cognitive disorder (-) | 158,718 (96.88) | 40,446 (96.75) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Cognitive disorder (+) | 5,111 (3.12) |

1,360 (3.25) |

1.046 (0.985–1.111) |

0.140 | 1.049 (0.988–1.114) |

0.118 |

| Movement disorder (-) | 163,309 (99.68) |

41,636 (99.59) |

1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Movement disorder (+) | 520 (0.32) |

170 (0.41) |

1.222 (1.026–1.454) |

0.025 | 1.227 (1.030–1.461) |

0.022 |

| Personality disorder (-) | 163,439 (96.76) |

41,686 (99.71) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Personality disorder (+) | 390 (0.24) |

120 (0.29) | 1.219 (0.993–1.496) |

0.058 | 1.215 (0.990–1.492) |

0.063 |

| Any disorder (-) |

155,234 (94.75) | 39,400 (94.24) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Any disorder (+) |

8,595 (5.25) |

2,406 (5.76) | 1.101 (1.053–1.152) |

<0.001 | 1.102 (1.053–1.153) |

<0.001 |

| Kawasaki disease | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case (n, %) | No | Yes | HR (95% CI) |

p | HR (95% CI) |

p |

| Intellectual disorder (-) | 162,817 (99.38) | 41,612 (99.54) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Intellectual disorder (+) | 1,012 (0.62) |

194 (0.46) |

0.747 (0.640–0.871) |

<0.001 | 0.747 (0.641–0.871) |

<0.001 |

| Communication disorder (-) |

163,051 (99.53) |

41,628 (99.57) |

1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Communication disorder (+) |

778 (0.47) |

178 (0.43) |

0.897 (0.762–1.056) |

0.192 | 0.894 (0.760–1.052) |

0.179 |

| Specific learning disorder (-) | 163,708 (99.93) |

41,785 (99.95) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Specific learning disorder (+) | 121 (0.07) |

21 (0.05) | 0.643 (0.400–1.033) |

0.068 | 0.641 (0.399–1.030) |

0.066 |

| Autism spectrum disorder (-) | 163,226 (99.63) | 41,670 (99.67) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Autism spectrum disorder (+) | 603 (0.37) |

136 (0.33) | 0.876 (0.727–1.056) |

0.165 | 0.872 (0.724–1.051) |

0.150 |

| ADHD (-) |

160,512 (97.98) | 40,951 (97.95) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| ADHD (+) |

3,317 (2.02) |

855 (2.05) |

1.021 (0.947–1.101) |

0.580 | 1.017 (0.943–1.096) |

0.663 |

| Tic disorder (-) |

162,608 (99.25) |

41,451 (99.15) |

1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Tic disorder (+) |

1,221 (0.75) |

355 (0.85) |

1.154 (1.025–1.298) |

0.018 | 1.148 (1.020–1.292) |

0.022 |

| Any disorder (-) |

157,926 (96.40) | 40,262 (96.31) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| Any disorder (+) |

5,903 (3.60) |

1,544 (3.69) | 1.029 (0.973–1.088) |

0.322 | 1.027 (0.971–1.086) |

0.361 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).