Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

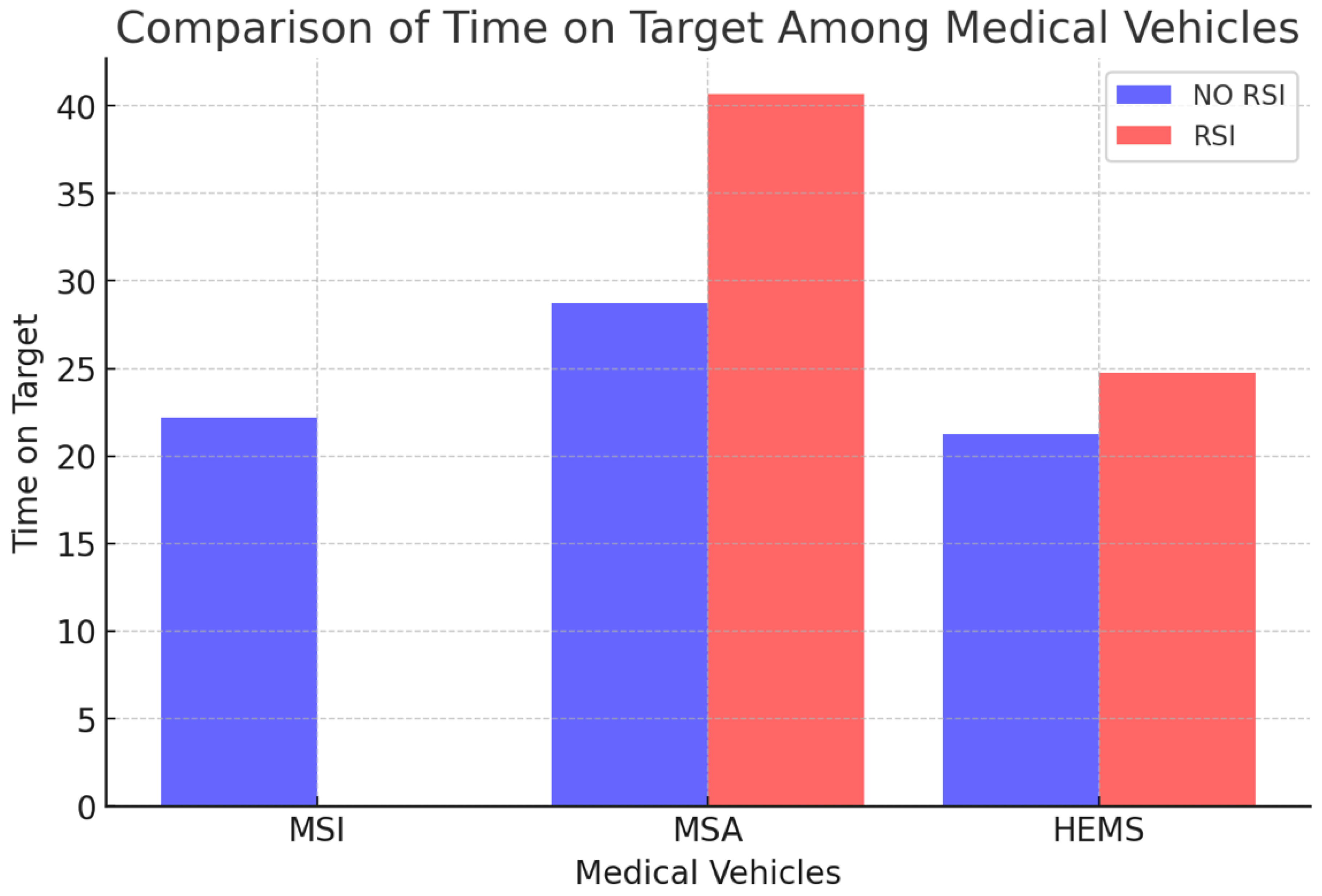

Ischemic stroke represents one of the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with early recognition and timely prehospital intervention playing a crucial role in improving overall patient outcomes. In Italy, stroke continues to be the second leading cause of death, with an annual incidence estimated to range between 95 and 290 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Given the substantial burden of this condition, optimizing prehospital management is of paramount importance. Methods: A retrospective observational study was conducted analyzing 1,051 emergency cards from the calendar year 2023 with a final diagnosis of ischemic stroke. After applying exclusion criteria, 944 cases were evaluated, managed by different emergency medical services: nurse-staffed ambulances (MSI, n=762), helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS, n=20), physician-staffed ambulances (MSAn=33), and medical -car services (n=129). Primary outcomes measured were time on target for each service type and the impact of advanced airway management on these times. Comparative analysis was performed between different service types and between intubated vs. non-intubated patients. Results: Both nurse-staffed (average: 22 min) and physician-staffed ambulances (average: 18 min) demonstrated significantly shorter time on target compared to medical car (average: 41 min for intubated patients, 29 min for non-intubated patients). HEMS maintained comparable times to nurse-staffed ambulances (average: 21 min for non-intubated patients, 25 min for intubated patients). The overall intubation rate for ischemic stroke patients was 1.23% (13/1,051), with similar rates between HEMS (10%) and road-based physician services (9%). Orotracheal intubation increased time on target by an average of 4 minutes for HEMS teams and 12 minutes for road-based physician teams. Conclusions: In conclusion, when responding to patients with a suspected ischemic stroke who are not expected to require advanced airway management, the most efficient and time-sensitive emergency medical response options are ambulances that are staffed either by nurses (MSI) or by physicians (MSA). These types of vehicles enable prompt on-scene assessment, stabilization, and transportation to an appropriate medical facility without unnecessary delays. However, in situations where a patient is experiencing a suspected stroke and is located at a considerable geographical distance from the nearest hospital equipped with a specialized stroke unit, the deployment of a Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) should be prioritized. Due to its ability to cover long distances in a significantly shorter time frame, HEMS represents the most effective pre-hospital transport solution for these patients, ensuring that they reach definitive stroke care as quickly as possible. On the other hand, the use of self-medication services or the dispatch of a medical car (automedica) for this patient population has been associated with an average delay of approximately 10 minutes in initiating critical pre-hospital care, without offering any significant additional treatment advantages compared to nurse-staffed ambulances. These findings offer essential insights and practical guidance for emergency medical dispatchers, enabling them to make more strategic and informed decisions regarding the optimal allocation of emergency resources. By improving pre-hospital response efficiency, these optimized dispatch strategies could contribute to reducing treatment delays, ultimately enhancing the overall quality of time-sensitive stroke care and improving patient outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Prehospital Response System

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Inclusion Criteria

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Timings

5.2. Airway Management

6. Discussion

6.1. Timing

- The medicalised ambulance has a lower time on target than other medical vehicles in that, as the crew consists of at least three figures (doctor, nurse and driver), unlike nursing ambulances which consist of only two figures (nurse and driver), they are able to transport the patient from the scene to the ambulance more quickly.

- The medicalised ambulance has a lower time-on-target than other medical vehicles because, as it always accompanies the patient from the target to the hospital, no time is used to write a report on the spot but this is likely to be done en route.

- Nursing ambulances have a lower time-on-target than ambulances because the nursing assessment is closely linked to pre-hospital assessment scales and therefore quicker than a medical assessment, which is certainly more thorough but less effective in terms of timing.

- Nursing ambulances have a shorter time-on-target than self-medications because they do not need to draw up the report on site as is necessary for self-medications if they decide not to accompany the patient by medicalising the vehicle, but to entrust the vehicle with the patient. The possibility of drawing up the report during transport can lead to a decrease in time on target.

- Helicopter rescue has a comparable time-on-target with nursing ambulances in that it, too, when transporting the patient, does not have to write the report on the spot but can write it during transport.

- Helicopter rescue has a time on target comparable with nursing ambulances in that it has a team of at least three members (doctor, nurse, mountain rescue technician) and, like the ambulances, can transport the patient from the target to the vehicle more quickly.

6.2. Airway Management

- Intubation rates are comparable between MSA road vehicles and HEMS vehicles.

- Overall intubation rates are very low, it is a condition that rarely requires the need for advanced airway management.

- The difference in intubation times between MSA road vehicles and HEMS vehicles could be explained by a different level of technical preparation for advanced orotracheal intubation manoeuvres between the teams of the two vehicles; in the case of the HEMS vehicle the team doctor is a doctor who is always a specialist in Anaesthesia and Resuscitation, in Emergency-Urgency Medicine or in other specialities but with proven experience in pre-hospital emergency-urgency, while in the case of the MSA vehicle on wheels he may not be a specialist doctor and therefore may not have a high level of experience in pre-hospital emergency-urgency.

7. Conclusions

- When determining the most effective and competitive emergency medical vehicles to be deployed as the primary response for patients presenting with a suspected ischemic stroke, it is essential to consider the patient’s anticipated medical needs. In cases where there is no suspicion that the patient will require advanced airway management, the most suitable and efficient first-choice options are nursing ambulances (MSI) and medical ambulances (MSA). These vehicles are capable of providing immediate on-site medical assistance while ensuring that the patient is transported to an appropriate facility without unnecessary delays.

- However, when a patient is suspected of having a stroke and, at the same time, is located a significant distance away from the nearest hospital equipped with a specialized stroke unit, the preferred mode of transportation should be a rotary-wing medical vehicle (HEMS). The rapid airborne transport offered by HEMS is particularly advantageous in these scenarios, as it substantially reduces pre-hospital time and facilitates quicker access to specialized stroke care.

References

- M.G. Balzanelli, Medicina di Emergenza e di Pronto Soccorso, I fondamenti, IV edizione.

- https://www.salute.gov.

- IU 304015 1002 Rev. R: 1 del 10/01/2023, 2023.

- Harrison, Principi di medicina interna, volume II.

- Brott, T.; Adams, H.P.; Olinger, C.P.; Marler, J.R.; Barsan, W.G.; Biller, J.; Spilker, J.; Holleran, R.; Eberle, R.; Hertzberg, V. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: A clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989, 20, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. D. Li khim kwah, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS).

- L. S. G. Goldstein, Reliability of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale: Extension to non-neurologists in the context of a clinical trial.

- S. S. e. al., Relationship between Ischemic Lesion Volume and Functional Status in the 2nd Week after Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke.

- Pezzella, F.R.; Picconi, O.; De Luca, A.; Lyden, P.D.; Fiorelli, M. Development of the Italian Version of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Stroke 2009, 40, 2557–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. P. H. M. e. a. Adams H, “Lesion characteristics, NIH Stroke Scale, and functional recovery after stroke“, 1999.

- B. L. E. K. F. M. G. T. F. K. Glymour M, “Lesion characteristics, NIH Stroke Scale, and functional recovery after stroke“.

- A Brotons, A.; Motola, I.; Rivera, H.F.; E Soto, R.; Schwemmer, S.; Issenberg, S.B. Abstract 3468: Correlation of the Miami Emergency Neurologic Deficit (MEND) Exam Performed in the Field by Paramedics with an Abnormal NIHSS and Final Diagnosis of Stroke for Patients Airlifted from the Scene. Stroke 2012, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/str.49.suppl_1.WP222#:~:text=Introduction%3A%20The%20Miami%20Emergency%20Neurologic,anterior%20and%20posterior%20circulation%20strokes.

- Antonino Bodanza, Advanced Medical Life Support, NAEMT.

- Albers GW et al: Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines, 8th ed. 6: Chest 133, 2008.

- Del Zoppo, Gj et al: Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminoen activator: a science advisory frome the AHA/ASA, Stroke 40:2945, 2009.

- Zoppo, Gj et al: Expansion of the time window for treatment of acute ischemic stroke with intravenous tissue plasminoen activator: a science advisory frome the AHA/ASA, Stroke 40.

- ASL Brescia, Emergenza stroke: il percorso per la gestione integrata dello stroke Archiviato il 13 aprile 2014 in Internet Archive.

- AREU Lombardia, Le nuove relazioni di soccorso MSB regionali Archiviato il 13 aprile 2014 in Internet Archive.

- Y: Schottke, First Responder.

- Pistoia.it - Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale Archiviato l'8 maggio 2006 in Internet Archive.

- P. Interaz 01 Stroke nel territorio di Verona e Provincia.

- Adams HP Jr, et al: Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke. 1: Stroke 38, 1655.

| MSI | MSA | HEMS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO RSI | 22.18 | 28.74 | 21.24 |

| RSI | -- | 40.69 | 24.76 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).