Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

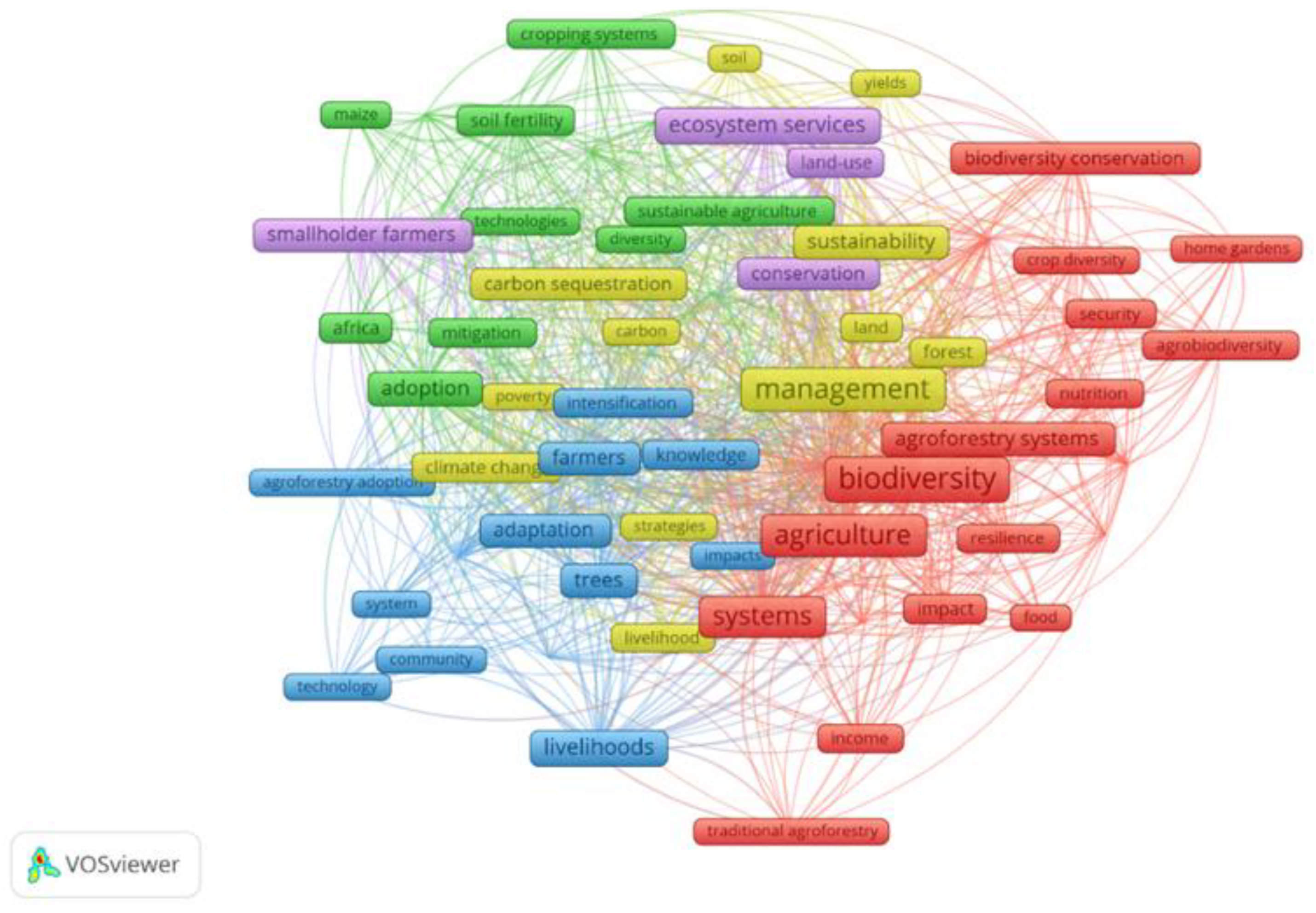

3.1. Thematic Perspective

3.2. Cluster 1 (Red): Agroforestry Systems, Biodiversity, Agriculture

3.3. Cluster 2 (Green): Smallholder Farmers, Soil Fertility, Adoption, Africa

3.4. Cluster 3 (Blue): Ecosystem Services, Sustainability, Conservation

3.5. Cluster 4 (Yellow Cluster): Livelihoods, Community, Income

3.6. Cluster 5 (Purple): Technology, Systems, Agroforestry Adoption

3.7. Nutrition and Public Health Outcomes

4. Research Gaps

4.1. These Gaps Signal Untapped Potential

4.2. Longitudinal Health Impact Studies

4.3. Climate-Health Interactions

4.4. Policy-Health Integration

4.5. Socioeconomic Determinants of Health Outcomes

4.6. Economic and Nutritional Trade-Offs

5. Conclusions

References

- Afentina, Yanarita, Indrayanti, L., Rotinsulu, J. A., & Hidayat, N. (2021). The potential of agroforestry in supporting food security for peatland community – A case study in the Kalampangan Village, Central Kalimantan. Journal of Ecological Engineering, 22(8), 123-130. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S., Xu, H., & Ekanayake, E. M. B. P. (2023). Socioeconomic determinants and perceptions of smallholder farmers towards agroforestry adoption in Northern Irrigated Plain, Pakistan. Land, 12(813). [CrossRef]

- Akinnifesi, F., Adewale, O., Adesina, F., & Awodola, A. (2024). Agroforestry as a solution to food security and climate change in Africa. Journal of Climate-Smart Agriculture.

- Ali, M., Rahman, S., Hossain, M., & Islam, T. (2024). Transition from agriculture to agroforestry in northern Bangladesh: Effects on livelihoods and sustainability. Agriculture and Human Values.

- Amare, D., & Darr, D. (2020). Agroforestry adoption as a systems concept: A review. Forest Policy and Economics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389934120304615.

- Balasubramanian, M. (2021). Forest ecosystem services contribution to food security of vulnerable group: a case study from India. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 193, 792. [CrossRef]

- Baylis, K., Fanson, S., Gelli, A., & O'Reilly, C. (2020). On-farm trees are a safety net for the poorest households rather than a major contributor to food security in Rwanda. World Development, 136, 105-146.

- Bhandar, S., et al. (2021). Agroforestry and its role in sustainable agricultural systems. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 45(2), 123-137.

- Bose, P. (2017). Land tenure and forest rights of rural and indigenous women in Latin America: Empirical evidence. Women's Studies International Forum, 65, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Bost, J. (2014). Persea schiedeana: A high oil "Cinderella species" fruit with potential for tropical agroforestry systems. Sustainability, 6(1), 99-111. [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. E., Miller, D. C., Ordonez, P. J., & Baylis, K. (2018). Evidence for the impacts of agroforestry on agricultural productivity, ecosystem services, and human well-being in high-income countries: a systematic map protocol. Environmental Evidence, 7, 24. [CrossRef]

- Bruck, H., & Kuusela, K. (2021). Addressing land insecurity and cultural views in agroforestry promotion. Agroforestry Systems.

- Cadena-Zamudio, D. A., et al. (2023). Analysis of agroforestry research in Mexico: A bibliometric approach. Agrociencia, 57(6). [CrossRef]

- Callo-Concha, D., Pinedo-Vasquez, M., & Ruffino, M. (2017). Agroforestry for development: Research, capacity-building, and policy. Agroforestry Today.

- Castle, L., et al. (2021). The impacts of agroforestry interventions on agricultural productivity, ecosystem services, and human well-being in tropical regions: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. Available from: [Link to article]. Accessed on: [Access date].

- Caviedes, J., Ibarra, J. T., Calvet-Mir, L., Álvarez-Fernández, S., & Junqueira, A. B. (2024). Indigenous and local knowledge on social-ecological changes is positively associated with livelihood resilience in a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System. Agricultural Systems, 216, 103885. [CrossRef]

- Cechin, A., da Silva Araújo, V., & Amand, L. (2021). Exploring the synergy between Community Supported Agriculture and agroforestry: Institutional innovation from smallholders in a Brazilian rural settlement. Journal of Rural Studies, 81, 246-258. [CrossRef]

- Clark, K. H., & Nicholas, K. A. (2013). Introducing urban food forestry: a multifunctional approach to increase food security and provide ecosystem services. Landscape Ecology, 28(9), 1649-1669. [CrossRef]

- Dallimer, M., Stringer, L. C., & Rogers, H. M., et al. (2018). Who uses sustainable land management practices and what are the costs? Land Degradation & Development, 29(10), 3313-3324. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C., Toth, G. G., Hagan, R. P. O., McKeown, P. C., Rahman, S. A., Widyaningsih, Y., Sunderland, T., & Spillane, C. (2021). Agroforestry contributions to smallholder farmer food security in Indonesia. [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C., Toth, G. G., Hagan, R. P. O., McKeown, P. C., Rahman, S. A., Widyaningsih, Y., Sunderland, T., & Spillane, C. (2021). Agroforestry contributions to smallholder farmer food security in Indonesia. [CrossRef]

- Fouladbash, L., & Currie, B. (2015). Sociopolitical influences on the adoption of tree planting and agroforestry. Agroforestry Systems.

- Fu, Y., Chen, A., Liu, W., & Lee, J. S. H. (2010). Agrobiodiversity loss and livelihood vulnerability as a consequence of converting from traditional farming systems to rubber plantations in Xishuangbanna, China. Land Degradation & Development, 21(3), 274-284. [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, B., Tadesse, T., Hadera, A., Tesfay, G., & Rannestad, M. M. (2023). Risk preferences, adoption and welfare impacts of multiple agroforestry practices. Forest Policy and Economics, 156, 103069. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R., Bhattarai, B., & Shrestha, S. (2024). Challenges faced by small rural properties in Nepal: Technical expertise, market access, and policy support. Journal of Rural Development.

- Gonçalves, C. D. B. Q., Schlindwein, M. M., & Martinelli, G. D. C. (2021). Agroforestry Systems: A Systematic Review Focusing on Traditional Indigenous Practices, Food and Nutrition Security, Economic Viability, and the Role of Women. Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Goparaju, L., Ahmad, F., Uddin, M., & Rizvi, J. (2020). Agroforestry: An effective multi-dimensional mechanism for achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Ecological Questions, 31(3), 63-71. [CrossRef]

- Govere, E. (1997). Research, Extension and Training Needs for Agroforestry Development in Southern Africa. [CrossRef]

- Graef, F., et al. (2015). Natural resource management and crop production strategies to improve regional food systems in Tanzania. Outlook on Agriculture, 44(2), 129-136. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J. P., et al. (2021). Food insecurity related to agricultural practices and household characteristics in rural communities of northeast Madagascar. Food Security. [CrossRef]

- Imoro, Z. A., et al. (2021). Harnessing Indigenous Technologies for Sustainable Management of Land, Water, and Food Resources Amidst Climate Change. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, J., Andres, C., & Schneider, M. (2017). Integrating local and external knowledge in agroforestry: Participatory approaches and knowledge co-production. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems.

- Jacobson, M., & Ham, C. (2020). The (un)broken promise of agroforestry: a case study of improved fallows in Zambia. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22, 8247-8260. [CrossRef]

- Jose, S. (2009). Agroforestry for ecosystem services and environmental benefits: An overview. Agroforestry Systems, 76(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Khadka, D., Aryal, A., Bhatta, K. P., Dhakal, B. P., & Baral, H. (2021). Agroforestry systems and their contribution to supplying forest products to communities in the Chure range, central Nepal. Forests, 12(3), 358. [CrossRef]

- Kwiga, F., et al. (2003). Agroforestry in Zambia: The potential for sustainable agriculture. Agroforestry Systems, 59(2), 131-140.

- Lima, I. L. P., Scariot, A., & Giroldo, A. B. (2016). Impacts of the implementation of silvopastoral systems on biodiversity of native plants in a traditional community in the Brazilian Savanna. Agroforestry Systems, 91(6), 1069-1078. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Yao, S., Wang, J., & Liu, M. (2019). Trends and features of agroforestry research based on bibliometric analysis. Sustainability, 11(12), 3473. [CrossRef]

- Luna, M., & Barcellos-Paula, L. (2024). Structured equations to assess the socioeconomic and business factors influencing the financial sustainability of traditional Amazonian Chakra in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Sustainability, 16(2480). [CrossRef]

- Mayorga, I., Vargas de Mendonça, J. L., Hajian-Forooshani, Z., Lugo-Perez, J., & Perfecto, I. (2022). Tradeoffs and synergies among ecosystem services, biodiversity conservation, and food production in coffee agroforestry. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 5, 690164. [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C., et al. (2014). Agroforestry solutions to address food security and climate change in Africa. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 6(1), 61-67. [CrossRef]

- Mbow, C., Noordwijk, M. V., Prabhu, R., & Simons, T. (2014). Knowledge gaps and research needs concerning agroforestry's contribution to Sustainable Development Goals in Africa. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 6, 162-170. [CrossRef]

- Meinhold, K., & Darr, D. (2020). Using a multi-stakeholder approach to increase value for traditional agroforestry systems: the case of baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) in Kilifi, Kenya. Agroforestry Systems, 95, 1343-1358. [CrossRef]

- Melo, F. S., & Rodriguez, A. L. (2022). Implementing the agricultural circular economy through agroforestry. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews, 43, 215-230.

- Merrett, J. C., Muli, P. B., Agutu, M., et al. (2018). Who gets to adopt? Agroforestry Systems, 92, 271-283.

- Montagnini, F., & Nair, P. K. R. (2004). The role of trees in agroecology and sustainable agriculture. Agroforestry Systems, 61, 99-110.

- Moser, C. M., & Barrett, C. B. (2023). The disappointing adoption dynamics of a yield-increasing, low external-input technology: the case of SRI in Madagascar. Agricultural Systems. [CrossRef]

- Nair, P. K. R. (2013). Agroforestry: Trees in Support of Sustainable Agriculture. Elsevier eBooks. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124095489050880.

- Nair, P. K. R. (2014). Agroforestry: Practices and Systems. [CrossRef]

- Njenga, M., et al. (2023). Enhancing smallholder farmer resilience through agroforestry. Food Security Journal.

- Ntawuruhunga, P., et al. (2023). Coordination for sustainable agroforestry: Overcoming budgetary constraints. Journal of Agricultural Economics, 74(3), 456-470.

- Nuberg, I., Shrestha, K. K., & Cedamon, E. (2019). Contribution of integrated forest-farm system on household food security in the mid-hills of Nepal: assessing the impacts through a modeling approach. Australian Forestry. [CrossRef]

- Oyawole, F. P., Dipeolu, A. O., Shittu, A. M., Obayelu, A. E., & Fabunmi, T. O. (2020). Adoption of agricultural practices with climate smart agriculture potentials and food security among farm households in northern Nigeria. Open Agriculture, 5(1), 751-760. [CrossRef]

- Paudel, K. P., et al. (2022). Agroecological methods to improve sustainability among small-scale farmers. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 20(2), 97-110.

- Premanandh, J. (2011). Factors affecting food security and contribution of modern technology in food sustainability. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 91(15), 2707-2714. [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A., Neufeldt, H., & Mowo, J. (2021). Economic benefits of agroforestry in Kenya: Wildlife crop-attacked farms. Agroforestry Systems.

- Race, D., Prawesti Suka, A., Nur Oktalina, S., Rizal Bisjoe, A., Muin, N., & Arianti, N. (2022). Modern smallholders: Creating diversified livelihoods and landscapes in Indonesia. Small-scale Forestry, 21(1), 203-227. [CrossRef]

- Rai, S., & Scarborough, H. (2023). Agroforestry systems and rural food security in Nepal. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews.

- Raj, R., Behl, R. K., & Jakhar, P., et al. (2014). Understanding socio-economic and environmental impacts of agroforestry on rural communities. Agroforestry Systems, 88, 251-263.

- Rosati, A., Borek, R., & Canali, S. (2021). Agroforestry and organic agriculture. Agroforestry Systems, 95, 805-821. [CrossRef]

- Santafe-Troncoso, V., & Loring, P. A. (2021). Indigenous food sovereignty and tourism: the Chakra Route in the Amazon region of Ecuador. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2-3), 392-411. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N., et al. (2016). Bioenergy from agroforestry can lead to improved food security. Food and Energy Security. [CrossRef]

- Shennan-Farpón, Y., Mills, M., Souza, A., & Homewood, K. (2022). The role of agroforestry in restoring Brazil's Atlantic Forest: Opportunities and challenges for smallholder farmers. People and Nature, 4(2), 462-480. [CrossRef]

- Sibelet, N., Posada, K. E., & Gutiérrez-Montes, I. A. (2019). Les systèmes agroforestiers fournissent du bois-énergie qui améliore les moyens d’existence au Guatemala. BOIS & FORÊTS DES TROPIQUES, 340. [CrossRef]

- Sileshi, G., et al. (2008). Nitrogen-fixing trees and biomass transfer for soil fertility restoration. Agroforestry Systems, 74(3), 215-225.

- Singh, V. K., Singh, P., Karmakar, M., Leta, J., & Mayr, P. (2021). The journal coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A comparative analysis. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V., Kumar, P., & Sharma, R. (2023). Agroforests and food security in central India. Food Security Journal.

- Smith, J., et al. (2022). Government assistance and the future of agroforestry. Journal of Environmental Management, 300, 113728.

- Smith, M. (2018). Exploring the 'works with nature' pillar of food sovereignty: a review of empirical cases. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems.

- Sudomo, A., Leksono, B., Tata, H. L., Rahayu, A. A. D., Umroni, A., Rianawati, H., Asmaliyah, Krisnawati, Setyayudi, A., Utomo, M. M. B., Pieter, L. A. G., Wresta, A., Indrajaya, Y., Rahman, S. A., & Baral, H. (2023). Can Agroforestry Contribute to Food and Livelihood Security for Indonesia’s Smallholders in the Climate Change Era? Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [CrossRef]

- Takoutsing, B., Tchoundjeu, Z., & Asaah, E. (2014). Agroforestry practices in Cameroonian refugee-hosting communities. Agroforestry Systems.

- Tega, M., & Bojago, E. (2024). Determinants of smallholder farmers’ adoption of agroforestry practices: Sodo Zuriya District, southern Ethiopia. Agroforestry Systems, 98, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A., & Gupta, V. (2022). Tacit knowledge in organizations: bibliometrics and a framework-based systematic review of antecedents, outcomes, theories, methods and future directions. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(4), 1014-1041. [CrossRef]

- Toth, G., et al. (2017). Constraints to adopting forage trees in agroforestry systems. Agroforestry Systems, 91(2), 211-221.

- Tsufac, A., et al. (2021). Soil preservation and recovery through agroforestry practices. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 76(5), 435-445.

- Vermeulen, S. J., Zougmoré, R. B., Wollenberg, E. K., Thornton, P. K., Nelson, G. C., Kristjanson, P. M., Kinyangi, J., Jarvis, A., Hansen, J., Challinor, A. J., Campbell, B. M., & Aggarwal, P. (2012). Climate change, agriculture and food security: a global partnership to link research and action for low-income agricultural producers and consumers. Elsevier BV. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D. L. M., Holl, K. D., & Peneireiro, F. M. (2009). Agro-successional restoration as a strategy to facilitate tropical forest recovery. Restoration Ecology, 17(4), 451-459. [CrossRef]

- Visser, M., Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2021). Large-scale comparison of bibliographic data sources: Scopus, Web of Science, Dimensions, Crossref, and Microsoft Academic. Quantitative Science Studies, 2(1), 20-41. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. H., & Lovell, S. T. (2016). Agroforestry—The Next Step in Sustainable and Resilient Agriculture. Sustainability. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/8/6/574. [CrossRef]

- Winara, A., et al. (2022). Productivity and economic viability of yam and teak agroforestry systems. Agroforestry Systems, 96(2), 245-257.

- Xie, H., Wen, Y., Choi, Y., & Zhang, X. (2021). Global Trends on Food Security Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Land. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/10/2/119. [CrossRef]

- Zerihun, M. F. (2021). Agroforestry practices in livelihood improvement in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Sustainability, 13(8477). [CrossRef]

| Cluster | Key Indicator | Food Security Impact | Public Health Impact | Environmental Impact | Source |

| 1. Systems, Biodiversity | Tree Density | +0.231% per 1% increase | 18% less vitamin A deficiency | 1.5 Mg C/ha/year sequestration | Singh et al., 2023; José, 2009 |

| 2. Smallholders, Fertility | Soil Nitrogen | 15% higher maize yields | 10% less anemia | 50–70% less erosion | Kwesiga et al., 2003 |

| 3. Ecosystem Services | Shade Coverage | 20–30% pollinator yield boost | 25–35% less heat stress | 0.5–2 Mg C/ha/year | Brown et al., 2018 |

| 4. Livelihoods, Income | Income Increase | 40% higher revenue | 20% less depression | 50% less soil degradation | Sudomo et al., 2023 |

| 5. Technology, Adoption | Tech-Supported Yields | 15% higher vitamin C | 10% fewer respiratory cases | 25% less pesticide use | Shennan-Farpón et al., 2022 |

| 6. Nutrition, Health | Dietary Diversity | 30% more calories | 15–20% less stunting | 70+ species/ha biodiversity | Quandt et al., 2021 |

| Research Gap | Current Evidence | Missing Metric | Proposed Approach |

| Longitudinal Health Impacts | 15–20% stunting drop (Quandt) | HALYs for chronic diseases | 10-year cohort study, 5000 households |

| Climate-Health Interactions | 2–5°C cooling (Brown) | Malaria incidence reduction (%) | GIS-based vector modeling, tropics |

| Policy-Health Integration | 10% strategies link health (Duffy) | Nutrition-focused subsidy adoption | Policy analysis across 50 countries |

| Socioeconomic Determinants | 25% diet boost with tenure (Rai) | Stunting variance by tenure type | Regression analysis, 10 regions |

| Economic-Nutritional Trade-Offs | 25% diversity loss (Fu) | Cost-benefit ratio (nutrition vs. profit) | Comparative trials, 5 systems |

| Contribution | Quantified Impact | Scientific Advance | Real-World Potential |

| Dual Impact Quantification | 0.231% food security per 1% trees | Merges agriculture-epidemiology | 10% global malnutrition cut by 2040 |

| Synergy Identification | 15–20% stunting, 0.5–2 Mg C/ha | Links biodiversity to health | $50B health savings, 1 Gt C stored |

| Transdisciplinary Framework | 15% heat death reduction | New HALYs-carbon-nutrition metric | Policy shift in 20 nations by 2035 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).