1. Introduction

The human immune system is a marvel of biological defense, orchestrated by an intricate web of molecules and cells, designed to identify, and eliminate invading pathogens. Key players in this complex immune response are the human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), also known as the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in humans. These proteins are responsible for capturing fragments of pathogens and presenting them to T cells, enabling the adaptive immune system to recognize and mount targeted defenses. The HLA system, characterized by its remarkable polymorphism, offers a vast array of allelic variations, allowing the immune system to engage with a diverse range of microbial peptides. This diversity, in turn, contributes to an individual's unique immune responses and susceptibility or resistance to infections [

1,

2,

3].

HLA genes can significantly impact the outcome of viral infections. Notably, certain HLA alleles have been linked to susceptibility or resistance in the context of viral pathogens such as HIV, hepatitis C, and influenza [

4,

5,

6]. These associations underscore the profound influence of HLA genetics on immune responses and disease outcomes. HLA polymorphism results in differences in epitope binding affinity, and the T cell repertoire developed during thymic selection, affecting the immune system's ability to recognize and respond to viral threats [

7,

8].

The advent of SARS-CoV-2 in late 2019, leading to the global COVID-19 pandemic, has posed unprecedented challenges to public health systems worldwide. While the majority of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 experience mild to moderate symptoms or remain asymptomatic, a subset of patients develops severe, and in some cases, fatal pneumonia. Notably, the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 cannot be fully explained by demographics and pre-existing health conditions alone, suggesting that genetic factors may play a substantial role in determining the severity of the disease [

9].

Recent studies have begun to unravel the relationship between HLA alleles and COVID-19 severity. These investigations have associated specific HLA haplotypes and alleles with either protection or increased risk of severe COVID-19, highlighting the significant influence of HLA genetics on the disease's outcomes [

8,

10,

11]. The proposed mechanism underlying this association lies in the differential binding and presentation of viral epitopes by distinct HLA alleles, which can modulate the efficacy of the host's immune response.

However, it is important to recognize that the relationship between HLA alleles and COVID-19 severity exhibits notable variations across different populations. The Arab world, with a total population of approximately 450 million people [

12], shares significant genetic material due to historical migration patterns and common ancestry [

13]. Saudi Arabia, with a population of about 35.5 million as of 2022 [

14], represents a significant portion of this genetic pool. Despite this large population base, there is limited research examining HLA profiles and COVID-19 outcomes in Arab populations, with most existing studies focusing on Western populations. While substantial research has been conducted in certain populations, such as Italian or American patients, racially diverse non-Western groups like Saudi Arabians have been relatively understudied. Considering the genetic diversity in Saudi Arabia and the limited COVID-19 genetic research in this population, there is a compelling need for population-specific investigations. These studies can offer crucial insights into the intricacies of COVID-19 immunity within diverse genetic backgrounds and reveal unique facets of the disease's epidemiology [

15,

16,

17].

This paper seeks to contribute to the growing body of knowledge on the subject by investigating whether viral mutations in successive SARS-CoV-2 waves have led to escape from common HLA alleles in the Saudi Arabian population, with a primary focus on HLA class I alleles. We aim to explore the binding affinities of SARS-CoV-2 epitope peptides for select common HLA class I alleles prevalent in Saudis. By assessing potential differences in binding affinities across recently dominant SARS-CoV-2 strains, we aim to shed light on the evolution of the virus and its impact on the immune system.

The significance of this research extends beyond its immediate context. It has the potential to uncover patterns of viral evolution and elucidate the mechanisms of immune evasion. Insights gained from this research may not only inform our understanding of T cell immunity in the natural course of infection but also contribute to the design of more effective vaccines tailored to populations with specific HLA profiles.

2. Materials and Methods

This study analyzed HLA allele frequencies in a cohort of 45,457 potential stem cell donors registered at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This donor population had existing HLA genotyping data available. HLA class I (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C) and class II (HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DPB1) allele frequencies were determined for the cohort based on next-generation sequencing of exons 2 and 3, as previously described [

18].

Based on HLA allele frequencies in the Saudi Arabian cohort, the three most common HLA class I alleles were selected for analysis: HLA-A_02:01, HLA-B_51:01, and HLA-C*06:02. These alleles had frequencies of 18.5%, 14.1%, and 16.1% respectively in the population.

Viral epitope peptides with predicted or experimentally validated HLA binding for the alleles of interest were identified from the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) [

19]. Epitopes located in the spike (S) protein were prioritized, as this is the major target of neutralizing antibodies and T-cell responses [

20]. 7 epitopes were selected for each allele based on the strength of predicted affinity and coverage of key regions like the receptor binding domain.

The binding affinity between the selected HLA class I alleles and corresponding SARS-CoV-2 epitope peptides was analyzed using the NetMHCpan 4.1 server [

21]. NetMHCpan uses artificial neural networks to predict peptide-HLA binding based on training with affinity and mass spectrometry data. For each allele, 7 epitope peptides were selected based on their predicted binding affinity scores. Epitopes were categorized as strong binders (scores < 0.5), weak binders (scores between 0.5 and 2.0), and non-binders (scores > 2.0).

Four globally dominant SARS-CoV-2 strains were selected for comparison: Alpha, Epsilon, Gamma, and Omicron. The predicted binding affinity for each epitope-HLA allele pair was determined across the four strains.

One-way ANOVA was performed to assess differences in binding affinity scores among SARS-CoV-2 strains for each HLA allele. Additionally, one-sample t-tests were conducted to compare the mean binding affinity scores of the 7 selected epitopes to a theoretical mean of 0 for each strain and HLA allele combination. Pairwise chi-square tests were used to compare the distribution of epitope binding categories (strong binders, weak binders, and non-binders) between each pair of SARS-CoV-2 strains for each HLA allele. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. Overall Binding Affinity Analysis

This study analyzed binding affinities between three common HLA class I alleles in the Saudi Arabian population (HLA-A02:01, HLA-C06:02, and HLA-B*51:01) and viral epitopes from four major SARS-CoV-2 strains (Alpha, Epsilon, Gamma, and Omicron). The binding affinities were predicted using the NetMHCpan 4.1 server, with 7 epitope peptides selected for each allele based on frequency in the spike protein. They predicted HLA binding according to the Immune Epitope Database.

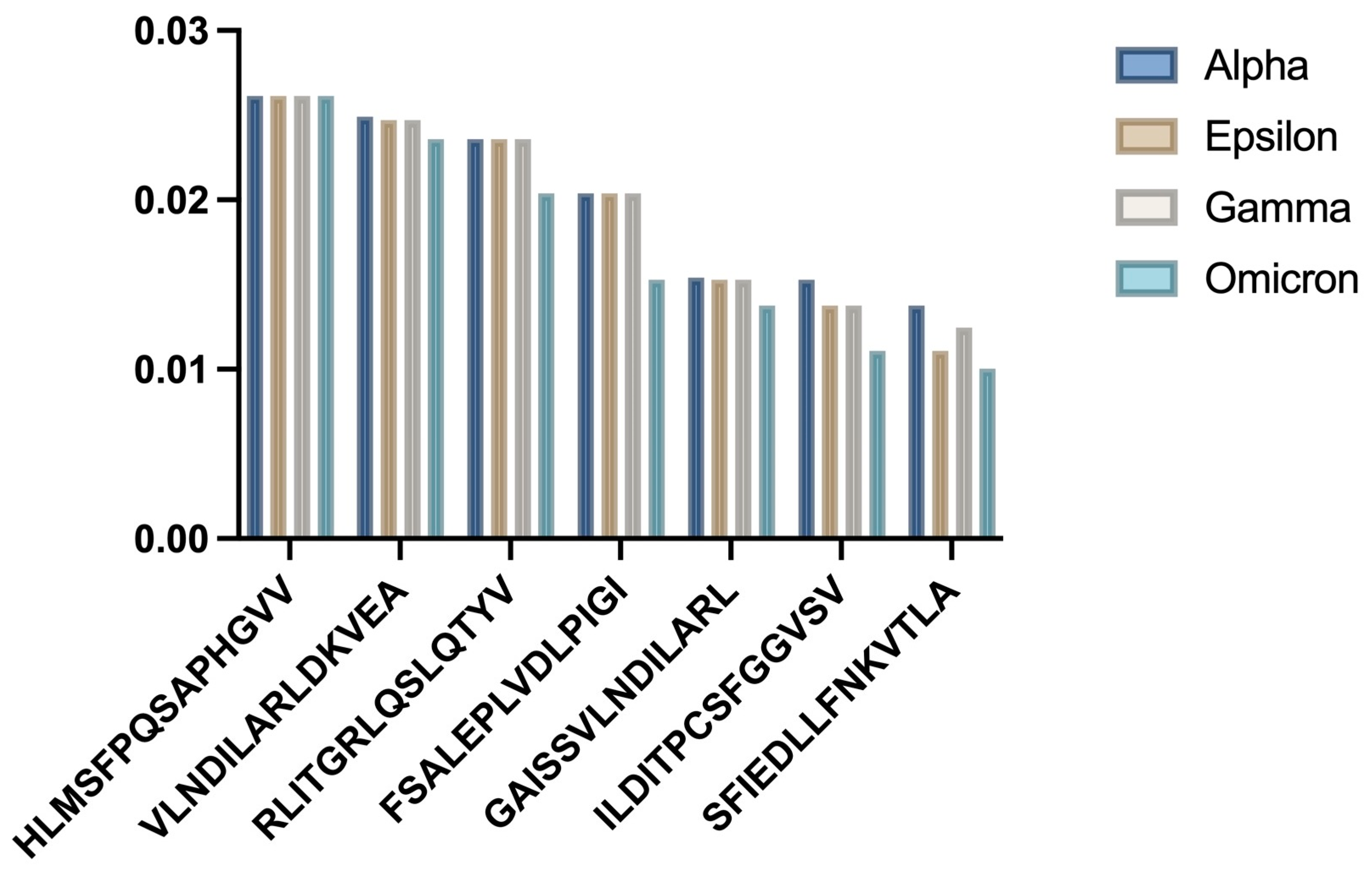

3.2. HLA-A02:01 Analysis

Analysis of the frequent allele HLA-A02:01 showed statistically significant differences in binding affinities for the 7 selected epitopes across SARS-CoV-2 strains (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. HLA-A02:01 Binding Affinity Analysis:

- a)

Bar chart showing comparative binding affinities across SARS-CoV-2 variants

- b)

Statistical distribution of binding patterns

One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences among the strains (p = 0.009954). The Alpha variant epitopes generally showed the strongest predicted binding, which weakened for later strains like Omicron. One-sample t-tests comparing the mean binding affinity scores showed significant differences for all strains (

Table 1).

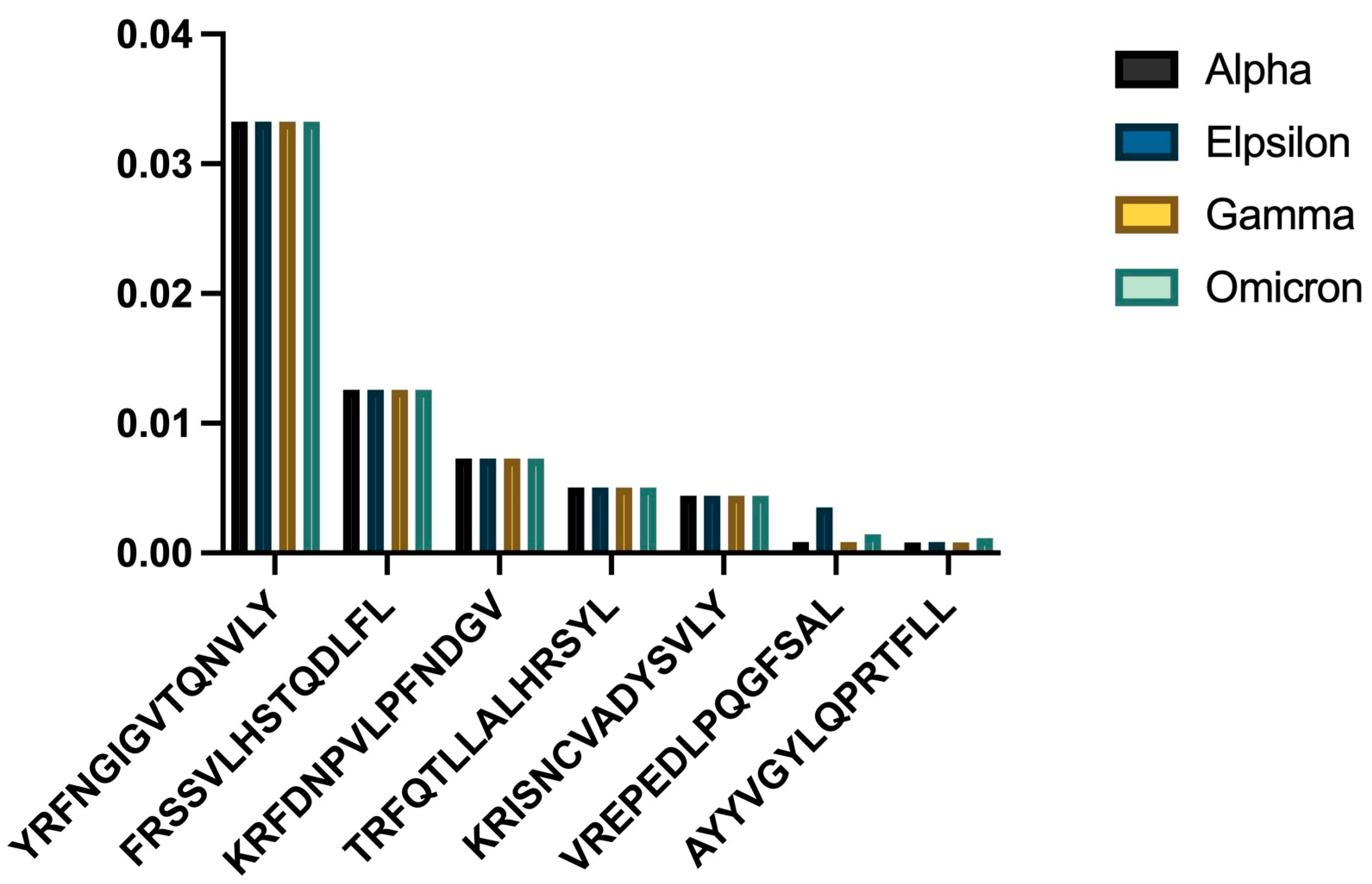

3.3. HLA-C06:02 Analysis

HLA-C06:02 demonstrated a similar trend of declining binding affinities in newer viral strains (

Figure 2).

- a)

Comparative binding strengths across variants

- b)

Trend analysis showing temporal changes

One-way ANOVA showed significant differences among the strains (p = 0.025474). The Omicron variant showed the weakest HLA-C06:02 binding for many epitopes. One-sample t-tests revealed significant differences in mean binding affinity scores for all strains (

Table 2).

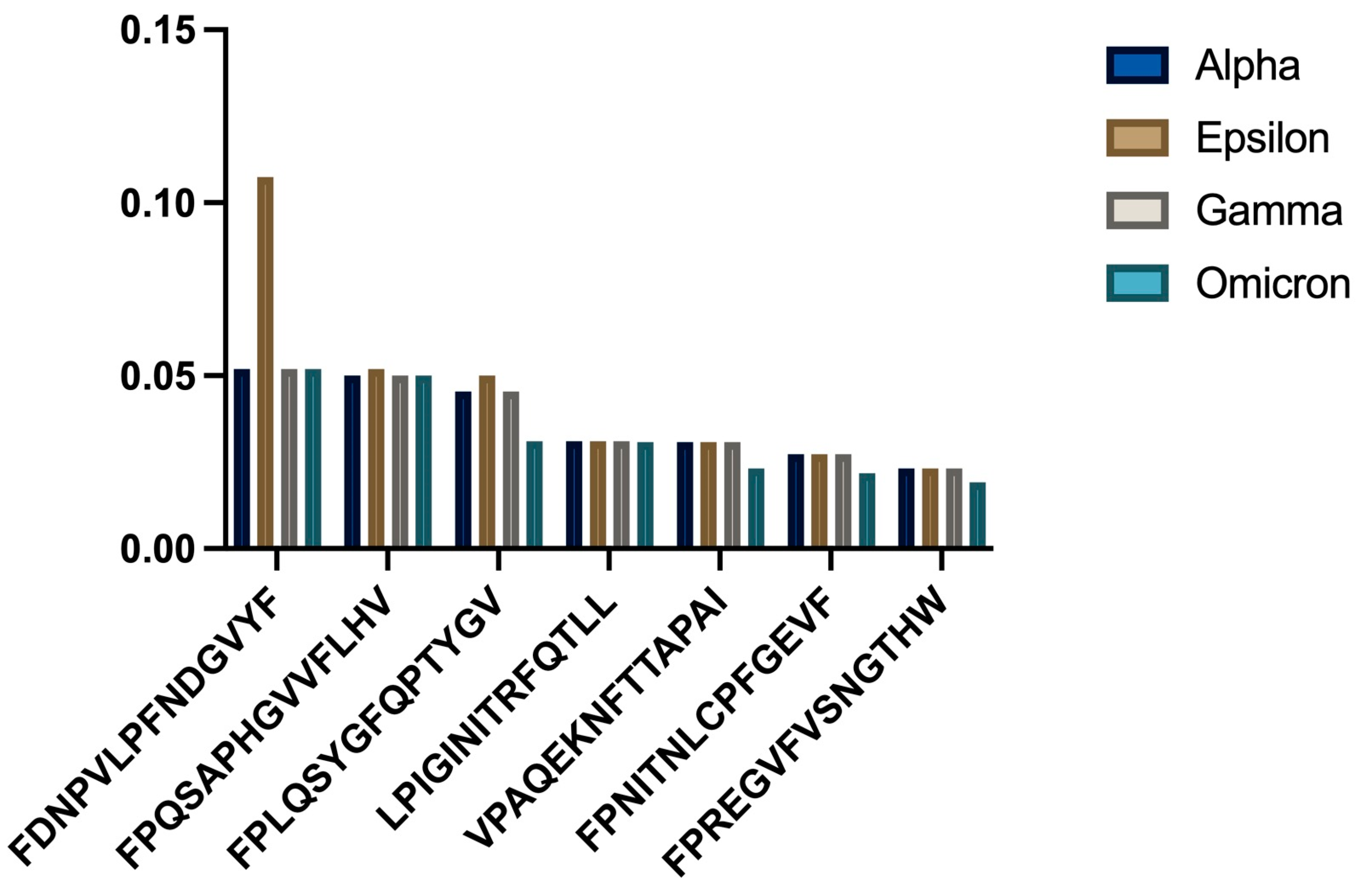

3.4. HLA-C06:02 Analysis

HLA-B51:01 showed different patterns from the other alleles (

Figure 3).

- c)

Consistency analysis across variants

- d)

Statistical comparison of binding affinities

One-way ANOVA gave non-significant P values for all strains (p = 0.967107). One-sample t-tests showed no significant differences in mean binding affinity scores (

Table 3).

3.5. Comparative Analysis Across Variants

Pairwise chi-square analyses were performed to compare the distribution of epitope binding categories between SARS-CoV-2 strains (

Table 4). Significant differences were observed between Alpha-Epsilon and Epsilon-Gamma strains for HLA-B*51:01 (p = 0.030197).

4. Discussion

This study investigated whether mutations in successive waves of SARS-CoV-2 have led to viral escape from common HLA class I alleles in the Saudi Arabian population. The results provide evidence of significant differences in binding affinities among SARS-CoV-2 strains for HLA-A02:01 and HLA-C06:02, but not for HLA-B51:01, as demonstrated by the one-way ANOVA. However, the pairwise chi-square analyses did not reveal significant differences in the distribution of specific peptides presented by HLA-A02:01 and HLA-C*06:02 across the strains.

The significant differences in binding affinities among strains for HLA-A02:01 and HLA-C06:02 suggest that SARS-CoV-2 mutations may impact the overall strength of epitope binding to these alleles. This could potentially affect the efficiency of antigen presentation and subsequent T-cell responses. These findings align with previous studies showing SARS-CoV-2 mutations that confer resistance to CD8+ T cell responses, particularly in the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein, where most analyzed epitopes were located [

22,

23]. Our results provide novel evidence that this viral escape is occurring in the context of common HLA alleles in Saudis. Population-specific analyses are critical, as HLA binding is dependent on the unique peptide-binding pockets of alleles that vary in frequency across ethnicities.

Escape from dominant HLA alleles could have important consequences for SARS-CoV-2 immunity at a population level. HLA-A02:01 and HLA-C06:02 are predicted to present a significant proportion of viral epitopes to CD8+ T cells in Saudis based on their gene frequencies. Mutations reducing binding to these alleles may thus diminish viral control by compromising antigen presentation to cytotoxic T cells. This evasion of cellular immunity likely contributes to the increased transmissibility and ability to re-infect previously exposed individuals observed in newer SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Moreover, understanding HLA escape mutations provides insights that could optimize COVID-19 vaccines for the Saudi population. The use of ancestral Wuhan or Alpha spike immunogens may lead to relatively ineffective T-cell responses against newer viral strains. Vaccine design efforts should consider incorporating spike protein mutations that restore HLA binding lost due to viral evolution [

24]. Functional analysis of how identified mutations impact antigen processing and presentation is also warranted.

However, the lack of significant differences in the distribution of specific peptides presented by HLA-A02:01 and HLA-C06:02 across the strains indicates that the mutations may not substantially alter the repertoire of epitopes presented by these alleles. This underscores the importance of considering both the strength of epitope binding and the diversity of presented peptides when assessing viral escape from HLA-mediated immunity.

For HLA-B51:01, the absence of significant differences in both binding affinities and peptide distribution suggests that this allele may be less affected by SARS-CoV-2 mutations, potentially indicating a lower level of immune pressure on the virus. However, the pairwise chi-square analyses did reveal some differences in the distribution of epitope binding categories between certain SARS-CoV-2 strains for HLA-B51:01, specifically between Alpha and Epsilon strains and between Epsilon and Gamma strains. This suggests that the impact of viral mutations on HLA binding may vary across different alleles and highlights the importance of considering allele-specific effects when assessing immune escape.

Overall, this study demonstrates the ongoing interplay between SARS-CoV-2 evolution and human immunity. Tracking HLA escape will be vital for containing COVID-19 in diverse populations globally. Integrating HLA genetics into epidemiologic, therapeutic, and vaccine research remains an important frontier in comprehensively understanding and combating this pandemic.

5. Limitations and Future Directions

While this study provides novel insights into the impact of SARS-CoV-2 mutations on HLA-mediated immune responses in the Saudi Arabian population, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. One key limitation is the reliance on computational predictions of binding affinities, which may not fully capture the complexity of in vivo antigen presentation. Experimental validation of the predicted impact of mutations on HLA binding and T cell recognition is necessary to confirm these findings. In vitro assays using HLA-typed cells and patient-derived T cells could provide valuable functional data to complement the computational analyses.

Another limitation is the lack of clinical data to directly assess the impact of the observed differences in binding affinities on T cell responses and disease outcomes. Future studies should aim to integrate binding affinity data with clinical measures of disease severity, viral load, and immune responses in infected individuals. Such analyses would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the functional consequences of SARS-CoV-2 mutations on HLA-mediated immunity and their potential implications for disease progression and transmission.

Furthermore, this study focused on a limited set of common HLA class I alleles in the Saudi Arabian population. Extending the analysis to a broader range of HLA alleles, including class II alleles, would provide a more comprehensive picture of the impact of SARS-CoV-2 mutations on HLA-mediated immunity across diverse genetic backgrounds. Class II HLA molecules present viral epitopes to CD4+ T cells, which play crucial roles in orchestrating adaptive immune responses and providing help to B cells and CD8+ T cells. Investigating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 mutations on class II HLA binding and presentation could reveal additional insights into viral immune escape mechanisms and inform vaccine design strategies.

Future studies should also consider the potential impact of SARS-CoV-2 mutations on other aspects of the immune response, such as antibody recognition and neutralization. Integrating data on HLA binding escape with information on antibody epitopes and neutralizing antibody responses could provide a more holistic view of how viral evolution shapes immune evasion and protection.

Additionally, longitudinal studies that track HLA binding affinities and immune responses over time in infected individuals or vaccinated cohorts could shed light on the dynamics of viral escape and the durability of HLA-mediated immunity. Such studies could also help identify key epitopes or HLA alleles that are associated with better clinical outcomes or more robust and long-lasting immune protection.

Lastly, expanding the study to include more diverse populations and HLA allele frequencies would enable a better understanding of the generalizability of these findings and the potential for population-specific immune escape patterns. Collaborative efforts to share data and integrate findings across different study cohorts could accelerate progress in this area and inform global vaccine and immunotherapy development efforts.

In conclusion, while this study provides valuable insights into the impact of SARS-CoV-2 mutations on HLA-mediated immunity in the Saudi Arabian population, further research is needed to validate these findings experimentally, expand the scope of the analysis, and translate the results into actionable strategies for vaccine design and pandemic control. Addressing these limitations and pursuing the identified future directions will be crucial for advancing our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 immune escape and developing more effective interventions to combat this ongoing global health threat.

6. Conclusion

This study analyzed binding affinities between common HLA class I alleles in Saudi Arabia (HLA-A02:01, HLA-C06:02, and HLA-B51:01) and epitopes from major SARS-CoV-2 strains (Alpha, Epsilon, Gamma, and Omicron). The results demonstrate significant differences in binding affinities among strains for HLA-A02:01 and HLA-C*06:02, as evidenced by the nested one-way ANOVA, suggesting that viral evolution may impact the overall strength of epitope binding to these alleles. However, pairwise chi-square analyses did not reveal significant differences in the distribution of specific peptides presented by these alleles across the strains.

In contrast, HLA-B*51:01 did not show evidence of significant differences in either binding affinities or peptide distribution among the strains, indicating that this allele may be less affected by SARS-CoV-2 mutations.

These findings provide novel insights into the complex interplay between SARS-CoV-2 evolution and HLA-mediated immune responses in the Saudi Arabian population. While mutations may impact the overall binding affinity of epitopes to certain HLA alleles, the specific peptides presented by these alleles may remain relatively conserved. This highlights the importance of considering both the strength of epitope binding and the diversity of presented peptides when assessing viral escape from HLA-mediated immunity.

Mapping HLA escape mutations will be important for tracking viral evolution and understanding population-level immunity. The insights gained from this study can guide vaccine design efforts by informing the selection of epitopes that are less susceptible to escape mutations and more likely to elicit effective T-cell responses across diverse HLA profiles.

Further research is warranted to validate the predicted impact of mutations on HLA binding experimentally and to investigate the functional consequences of the observed differences in binding affinities on T-cell responses and clinical outcomes. Additionally, extending the analysis to include HLA class II alleles and integrating clinical data would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of SARS-CoV-2 mutations on immune responses in the Saudi Arabian population.

Overall, this study highlights the ongoing interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and human HLA genetics, emphasizing the importance of population-specific analyses in deciphering the complex dynamics of viral evolution and host immunity. The findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge on SARS-CoV-2 immune escape and underscore the need for integrating HLA genetics into epidemiologic, therapeutic, and vaccine research to develop effective interventions that account for the genetic diversity of global populations and are resilient to viral escape mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and S.M.; methodology, A.H.; software, A.H.; validation, A.H. and S.M.; formal analysis, A.H.; investigation, A.H.; resources, S.M.; data curation, A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and T.A.; visualization, A.H.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study involved computational analysis of publicly available genomic data and did not involve human subjects or animal experiments.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the GISAID Initiative and all the data contributors who made SARS-CoV-2 sequence data available for this research. We also thank the developers of NetMHCpan for providing access to their prediction server.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Parham, P. MHC class I molecules and KIRs in human history, health and survival. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5:201–14. [CrossRef]

- Horton R, Wilming L, Rand V, Lovering RC, Bruford EA, Khodiyar VK, et al. Gene map of the extended human MHC. Nat Rev Genet 2004;5:889–99. [CrossRef]

- Robinson J, Halliwell JA, Hayhurst JD, Flicek P, Parham P, Marsh SGE. The IPD and IMGT/HLA database: allele variant databases. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:D423–31. [CrossRef]

- Kaslow RA, Carrington M, Apple R, Park L, Muñoz A, Saah AJ, et al. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat Med 1996;2:405–11. [CrossRef]

- Kuniholm MH, Gao X, Xue X, Kovacs A, Marti D, Thio CL, et al. The Relation of HLA Genotype to Hepatitis C Viral Load and Markers of Liver Fibrosis in HIV-Infected and HIV-Uninfected Women. J Infect Dis 2011;203:1807. [CrossRef]

- Jia X, Han B, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Chen WM, Concannon PJ, Rich SS, et al. Imputing Amino Acid Polymorphisms in Human Leukocyte Antigens. PLoS One 2013;8:e64683. [CrossRef]

- Hill AVS, Allsopp CEM, Kwiatkowski D, Anstey NM, Twumasi P, Rowe PA, et al. Common west African HLA antigens are associated with protection from severe malaria. Nature 1991;352:595–600. [CrossRef]

- Basir HRG, Majzoobi MM, Ebrahimi S, Noroozbeygi M, Hashemi SH, Keramat F, et al. Susceptibility and Severity of COVID-19 Are Both Associated With Lower Overall Viral-Peptide Binding Repertoire of HLA Class I Molecules, Especially in Younger People. Front Immunol 2022;13.

- Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, Bujanda L, Buti M, Albillos A, Invernizzi P, et al. Genomewide Association Study of Severe Covid-19 with Respiratory Failure. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 17];383:1522–34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32558485/.

- Novelli A, Andreani M, Biancolella M, Liberatoscioli L, Passarelli C, Colona VL, et al. HLA allele frequencies and susceptibility to COVID-19 in a group of 99 Italian patients. HLA 2020;96:610–4. [CrossRef]

- Urzua CA, Herbort CP, Takeuchi M, Schlaen A, Concha-del-Rio LE, Usui Y, et al. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: the step-by-step approach to a better understanding of clinicopathology, immunopathology, diagnosis, and management: a brief review. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect 2022;12:17. [CrossRef]

- World Population Prospects 2022 World Population Prospects 2022 Summary of Results.

- Tadmouri GO, Sastry KS, Chouchane L. Arab gene geography: From population diversities to personalized medical genomics. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2014;2014. [CrossRef]

- Saudi Arabia Census Shows Total Population of 32.2 Million, of Which 18.8 Million are Saudis [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 10];Available from: https://www.spa.gov.sa/w1911463.

- Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:533–4.

- Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 2];Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern.

- Shields AM, Burns SO, Savic S, Richter AG, Anantharachagan A, Arumugakani G, et al. COVID-19 in patients with primary and secondary immunodeficiency: The United Kingdom experience. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021;147:870-875.e1. [CrossRef]

- Saini SK, Hersby DS, Tamhane T, Povlsen HR, Amaya Hernandez SP, Nielsen M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 genome-wide T cell epitope mapping reveals immunodominance and substantial CD8+ T cell activation in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol 2021;6:7550. [CrossRef]

- Vita R, Mahajan S, Overton JA, Dhanda SK, Martini S, Cantrell JR, et al. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB): 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47:D339–43. [CrossRef]

- Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020;181:281-292.e6. [CrossRef]

- Andreatta M, Nielsen M. Gapped sequence alignment using artificial neural networks: application to the MHC class I system. Bioinformatics [Internet] 2016 [cited 2023 Nov 3];32:511–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26515819/.

- Shomuradova AS, Vagida MS, Sheetikov SA, Zornikova K V., Kiryukhin D, Titov A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Epitopes Are Recognized by a Public and Diverse Repertoire of Human T Cell Receptors. Immunity [Internet] 2020 [cited 2023 Nov 3];53:1245-1257.e5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33326767/.

- Zuo J, Dowell AC, Pearce H, Verma K, Long HM, Begum J, et al. Robust SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity is maintained at 6 months following primary infection. Nat Immunol [Internet] 2021 [cited 2023 Nov 3];22:620–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33674800/.

- Tarke A, Sidney J, Methot N, Zhang Y, Dan JM, Goodwin B, et al. Negligible impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on CD4 + and CD8 + T cell reactivity in COVID-19 exposed donors and vaccinees. bioRxiv [Internet] 2021 [cited 2023 Nov 3];Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33688655/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).