1. Introduction

Aging is associated with a decline in some cognitive functions and a slowing of executive functions, although both dimensions are within the parameters of normal evolutionary development. However, increased life expectancy is associated with increased vulnerability to cognitive impairment, furthermore the role of other biographical and contextual cues [

1,

2]. In longer-lived societies, there is a need for early detection in the cognitive continuum from subjective complaints of memory loss through mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to early Alzheimer's disease (AD). One of the key elements, according to the World Report on Dementia, is the high rate of older adults who are unaware of their level of impairment and the consequent risk of dementia [

3].

The purpose of this study is to examine the variables that predict the vulnerability to MCI and to compare the modes of administration between the traditional face-to-face assessment and the virtual assessment. We emphasize the key to screening for MCI as the focus of research, not the diagnosis of MCI, which should be done with neuropsychological assessment procedures and biomarkers. To achieve early detection in large populations, we need screening tests with good sensitivity, specificity, and efficacy, as well as positive and negative predictive values.

The aging of the population has led to an increase in cognitive impairment in the elderly, which has increased the prevalence of dementia, particularly Alzheimer's dementia [

4]. In the continuum of cognitive impairment, MCI is the clinical entity that precedes AD [

5]. Therefore, the detection of MCI is important for a clinical and early approach to the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease.

Research in this area emphasizes that MCI is a transitional stage between normality and dementia, involving problems with higher mental processes but with little functional impact [

6]. Concerning to neuropsychological symptoms, criteria based on amnestic dysfunction were first used to objectify the diagnosis of MCI [

7], and the construct was subsequently expanded [

8] to include MCI-amnestic, MCI-amnestic domain, MCI-amnestic multidomain, and MCI-non-amnestic, domain, or multidomain [

5]. Subsequently, the NIA-AAA [

9] and the National Institute of Alzheimer's Work Group [

10] established new dementia criteria using clinical, neuropsychological, and biomarker criteria that advance the diagnosis of prodromal AD.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a clinical diagnosis [

5]. When clinical suspicion is raised, the first step is to conduct an appropriate screening. In this regard, we highlight two screening tests that are widely accepted in the evaluation of cognitive impairment: the MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) and the Clock Test (CT) in its order and copy versions [

11,

12]. Several studies have pointed out the usefulness of the MoCA, especially in people with a high level of education [

13].

Moreover, the CT, in its two variants (on command and copying), offers a complementary and more ecological perspective to the MoCA, allowing a more precise differentiation of cognitive impairment by analyzing the pattern of improvement [

11,

12,

14]. Along the same lines as the Mini-Clock ([

15] which is the combination of the Mini-Mental plus the CT, we propose, as a complement to the MoCA, the application of the two versions of the CT(on command and copy) and the assessment of the pattern of improvement to expand the accuracy in the screening of cognitive impairment.

The incidence and prevalence of mild cognitive impairment vary according to the diagnostic criteria used [

16], so it is important to promote methodological proposals for assessment updated with the APA criteria [

17]. The increase in the prevalence of cognitive impairment has encouraged the search for non-pharmacological preventive interventions, which represent an emerging therapeutic approach and offer the possibility of preventing or delaying cognitive impairment and functional disability that marks the transition to dementia [

18].

In addition, the DSM-5 includes two criteria: the presence of cognitive deficits in at least one cognitive domain (e.g., memory, language, attention); also, that this impairment causes a significant decline from previous levels of independence in activities of daily living [

19]. The importance of clinically considering the role of subjective memory complaints as an early indicator has also been emphasized [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Updating the criteria for cognitive impairment is under discussion and should be based on empirical evidence and suggestions from professional groups [

4,

24]. As an innovative element, in addition to the diagnostic criteria (DSM-5 or ICD-11), the relevant contributions of the Boston Process Approach (BPA), applicable to screening tasks, should be considered. Therefore, it is necessary to go beyond the quantitative measurement for screening, which should emphasize how the older adult performs in the execution of the test [

25].

For older adults, healthy aging is directly related to their autonomy, understood as the functional capacity required to perform basic, instrumental, and advanced activities of daily living. A study [

26] suggests that deterioration in instrumental activities of daily living has a significant correlation with mild cognitive impairment. Therefore, a basic criterion for establishing the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment is to assess the level of autonomy in activities of daily living, as functionality may be a prognostic factor in determining the degree of progression to dementia in the short or medium term [

16].

Because of the above, it seems necessary to consider as a priority the risk of MCI in the elderly population, considering the pattern of deterioration manifested, to predict its possible evolution into a major neurocognitive disorder [

27]. Cognitive status is the first key identified in the literature as a sensitive indicator, although the cognitive function that deteriorates may differ from case to case, which would characterize the subtype of MCI [

28]. In addition, the literature consistently points to the role that emotional changes play in cognitive decline and overall well-being [

29,

30]. Isolation and lack of social contacts would act as inhibitors of the stimulation that interpersonal relationships provide for cognitive maintenance. In this line, the role of loneliness that may be experienced by elderly people with isolated or impoverished residential habitats should be emphasized [

31].

Finally, the functionality of older adults, whether autonomous or institutionalized, is very relevant given that the most recent revision of the DSM-5 (APA) [

17] established functionality as one of the distinctions between major and minor neurocognitive disorders. Thus, the basic differentiating key between the two is the impact or absence of impairment while performing daily living activities (DLAs). This third key, autonomy in performing DLAs (instrumental, basic, and advanced), is not independent of the previous ones, therefore its impairment could be an indicator of a greater risk of developing a major neurocognitive disorder. This must be considered a risk in cognitive assessment, especially in screening tests [

32], because some protective factors, such as cognitive reserve, may mask the decline and its progression [

33]. This is even more important considering the impact of the pandemic on the cognitive and emotional health of older people, as reflected in recent longitudinal studies showing accelerated decline due to the pandemic [

34].

The use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for screening and intervention (cognitive stimulation) has increased in recent years being beneficial for mild cognitive impairment detection when used in the early stages of mild cognitive impairment [

35]. Due to the increasing familiarity of older adults using mobile devices, new diagnostic scenarios should be available, hence the importance of implementing alternative tele-neuropsychological care for the elderly, especially considering the situation experienced after the COVID-19 pandemic. The proposal presented in this study follows this line, which is characterized by speed, efficiency, and accessibility, and which, because it is online, offers alternative care for the elderly at home, avoiding the risk of personal contact in circumstances like the pandemic.

In summary, although mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a particularly controversial entity, it remains a central construct given the importance of early diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorders [

36]. Given that population-based screening tests for cognitive impairment are impractical, initial detection of mild cognitive impairment will rely heavily on subjective memory complaints (SMC) as a presenting symptom. The problem is that SMC is heterogeneous in its etiology and its significance must be confirmed by a professional [

37]. In this process, the role of key informants (family members or people in the environment), who can corroborate certain changes or dysfunctions and the evolution throughout recent years, is relevant.

This work aims to discriminate the most relevant variables to determine the likely risk of cognitive impairment in the elderly. In addition, these variables were explored in two assessment modalities (face-to-face and online), combining objective information on the elderly's performance with that provided by key informants. This hybrid technology solution alleviates the limitations of the isolation situations resulting from the pandemic, in the absence of the sentinel epidemiological surveillance systems developed by the primary care centers. Having a specific and reliable screening protocol to identify indicators of early cognitive impairment is key to implementing prevention programs and timely care according to the needs of possible cases of MCI, in addition to bridging national and international geographical gaps using ICTs. This approach responds to the gaps identified in the literature in this psychological area [

38].

2. Materials and Methods

Participants.

The participants were recruited from March 2021 to July 2022, 148 subjects were cognitively assessed (plus the key informant being a caregiver or a close relative to the participant, a total of 296 subjects participated in the study). Subjects included in the sample were recruited in two ways. Firstly, through the Municipal Centers for the Elderly of the City Council of Salamanca. Secondly, through the users who came directly to request the services from the Memory Unit (MU) at the Psychology Faculty in the Pontifical University of Salamanca (UPSA).

Of the 148 subjects, 23.6% =39 were male and 76.4% =109 were female. The mean age was 72.91 years (SD 6.46). Finally, and given the characteristics of this work, the 148 subjects were assigned to an intervention modality (face-to-face or online) previously requested by the participant. For each one of the modalities, data were selected from 79 subjects who met the above inclusion criteria. In addition, 148 key informants participated, of whom 47.3% =70 were men and 52.7% =78 were women. In terms of relationship to the participants, 77.7% of the key informants were first-degree relatives, while 22.3% were second-degree relatives.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

- Participants must be residents of the city of Salamanca, Spain.

- Be at least 60 years old at the time of selection.

- Not be institutionalized in a nursing home.

- Not have a previous diagnosis of MCI.

- Able to give informed consent.

- Willingness to attend the scheduled appointments and complete the required questionnaires.

Regarding the inclusion criteria, it should be noted that cognitively healthy older adults (without previous diagnosis of cognitive impairment) were included since this is a population-based study on demand. This means that the MU should be available for all situations where an assessment of the SMC is requested since it is a service financed by a public institution to cover a need that is not offered in primary healthcare systems. The basic task of the MU is to become a sentinel epidemiological surveillance unit to refer to specialized services the cases that, according to the above assessment, are at high risk of possible MCI.

Instruments.

A questionnaire was used to obtain the socio-demographic data of the participant and recorded in a card-created ad doc (anonymous and coded); besides this, four tests were administered to the older adult. First, the Yesavage Depression Scale (YDP) was used to screen the emotional status of the subjects and to verify that they could participate since one of the exclusion criteria was to be under psychiatric treatment or with depression.

Before implementing the online protocol, pilot tests were conducted with the population of interest to adapt the instruments from the in-person to the online modality. The cognitive assessment instruments used were the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA), the Cacho Version Clock Drawing Test (CDT), and the Word Accentuation Test (WAT). The Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) and the Activities of Daily Living Questionnaire (IDDD) were used to obtain data about the participants from the perspective of the key informant (family member or caregiver).

The MoCA was found to be valid for the detection of MCI in the Spanish population, with significantly good internal consistency (Cronbach's a: 0.772), high reliability (Spearman correlation coefficient 0.846; P<.01), and high-reliability test-retest reliability: 0.922; P<.001). The MoCA was also effective and valid for detecting MCI (AUC±0.903) and early dementia (AUC±0.957). The cut-off points that would indicate MICI or early-stage dementia were: <21 and <20 respectively, with sensitivity percentages of 75% and specificity of 85% for MCI, whereas in early-stage dementia the sensitivity is 90% and 86% for MCI [

39]. In our study, the ICC between MoCA and CDT was 0.64, while for WAT/MoCA it was 0.810.

For this study, we used the Cacho version of the Clock Drawing Test (CDT), which includes the drawing of a clock on command (CDTcm) and its comparison to the drawing of a copied clock (CDTcp), the Cacho version of the CDT has been validated in the Spanish population with significant sensitivity and specificity indices [

40], and which proposes a cut-off point where a score <6 out of 10 is considered indicative of MCI. As for the WAT, it has not been previously validated in the Spanish population, but it has shown good internal values (alpha=.841) and a reliability of r=.908 when converting the score when comparing the scores obtained in subjects when administering the WAIS-IV scales in the Ecuadorian population (r=.827) [

41].

Regarding the use of Teleneuropsychology in this study, a rigorous approach was applied following the Teleneuropsychology guidelines proposed by the APA [

17,

38] during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological tests were administered and scored using a standardized procedure, online and in person. The main difference is in the method of test administration. While in the face-to-face format, they were administered in writing, in the virtual format the tests were presented by the examinee in front of the camera to provide the necessary screenshots of the task required of the participants.

The transition from in-person to tele-neuropsychology was challenging. During the virtual sessions, technical difficulties arose that required immediate resolution. To overcome these difficulties, specific communication protocols were established. In cases where the connection or platform experienced problems, a phone call was used to continue the session without interruption. In addition, in some cases, family members present at the patient's location provided technical assistance to ensure the uninterrupted flow of the sessions.

This approach, which guarantees the confidentiality, integrity, and validity of the results obtained, has made it possible to maintain high standards while providing neuropsychological services at a distance. To ensure the continuity of neuropsychological assessment in situations of confinement, such as those required during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was necessary to adapt the assessment procedures to the virtual modality.

In addition, it is important to note that the goal of the MU is to identify, through clinical history and screening, patients with suspected cognitive impairment for referral to specialized health centers for subsequent formal neurological and neuropsychological evaluation to establish a diagnosis as early as possible. In the MU, most patients are women with a high level of education, making the MoCA test an ideal screening tool. However, although the MoCA includes a clock drawing on command task, the complementary inclusion of a visuospatial performance task in the version of the CDT (CDTcm/CDTcp) and the CDT improvement pattern (IP) [

11,

12,

14] a more accurate screening for cognitive impairment. On the other hand, it is important to note that the MoCA includes a visuospatial test that consists of drawing a cube.

After the subjects were evaluated, key informants were interviewed using two instruments. To assess indicators of cognitive decline in the subjects, the IQCODE questionnaire was used, which asked informants about their perceptions of changes in intellectual functioning that the patients had experienced in recent years. The IQCODE has been validated in the Spanish-speaking population to determine the functional status of individuals before and after stroke [

42]; for this study, we used the cutoff originally proposed by Jorm, according to which a score >57 would indicate probable MCI, as this score has previously been shown to have high internal reliability in the general population (alpha = 0.95) and reasonably high test-retest reliability over one year in the dementia sample (r = 0.75). The IQCODE total score and each of its 26 items have been used to discriminate cognitive states between healthy populations and populations with dementia [

18].

Regarding the level of autonomy, the IDDD interview was applied to informants because previous studies have shown that people with MCI and early dementia are affected to varying degrees in their initiative and performance in instrumental life activities, also highlighting the importance of social activities for a sense of well-being [

43]. In this regard, Peres et al. [

44] have presented an adaptation and validation of the IDDD for the Spanish-speaking population, obtaining high internal consistency (a=.985) and reproducibility (interclass correlation coefficient = .94).

The correlations were significant (r=.81), showing that the IDDD in its Spanish version is a reliable version of the original IDDD, and can be used effectively in the Spanish population for the early stages of dementia and its follow-up. Therefore, it was used for this study with the same reference cut-off points (33-36 normal, 37-40 MCI indicators, >40 < MCI/dementia indicators in different degrees of severity). The scale's factor structure was also confirmed in MCI and AD populations.

Procedure

Due to the confinement situation resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, the application of the protocol was carried out according to the preference and circumstances of each participating subject, with two options available: face-to-face or online modality. In the first case, the consultation was carried out through a videoconferencing application, consisting of an evaluation with the subject (30-35 minutes), in which the cognitive state was assessed with the instruments described above. Then, in the second part (15 minutes), the key informant interview was conducted. For the online assessments, the adapted versions of the MoCA, CDT, and WAT were used, as well as the IQCODE and IDDD, always following the guidelines suggested by the APA [

45] for adapting instruments used in the face-to-face assessment to the online modality.

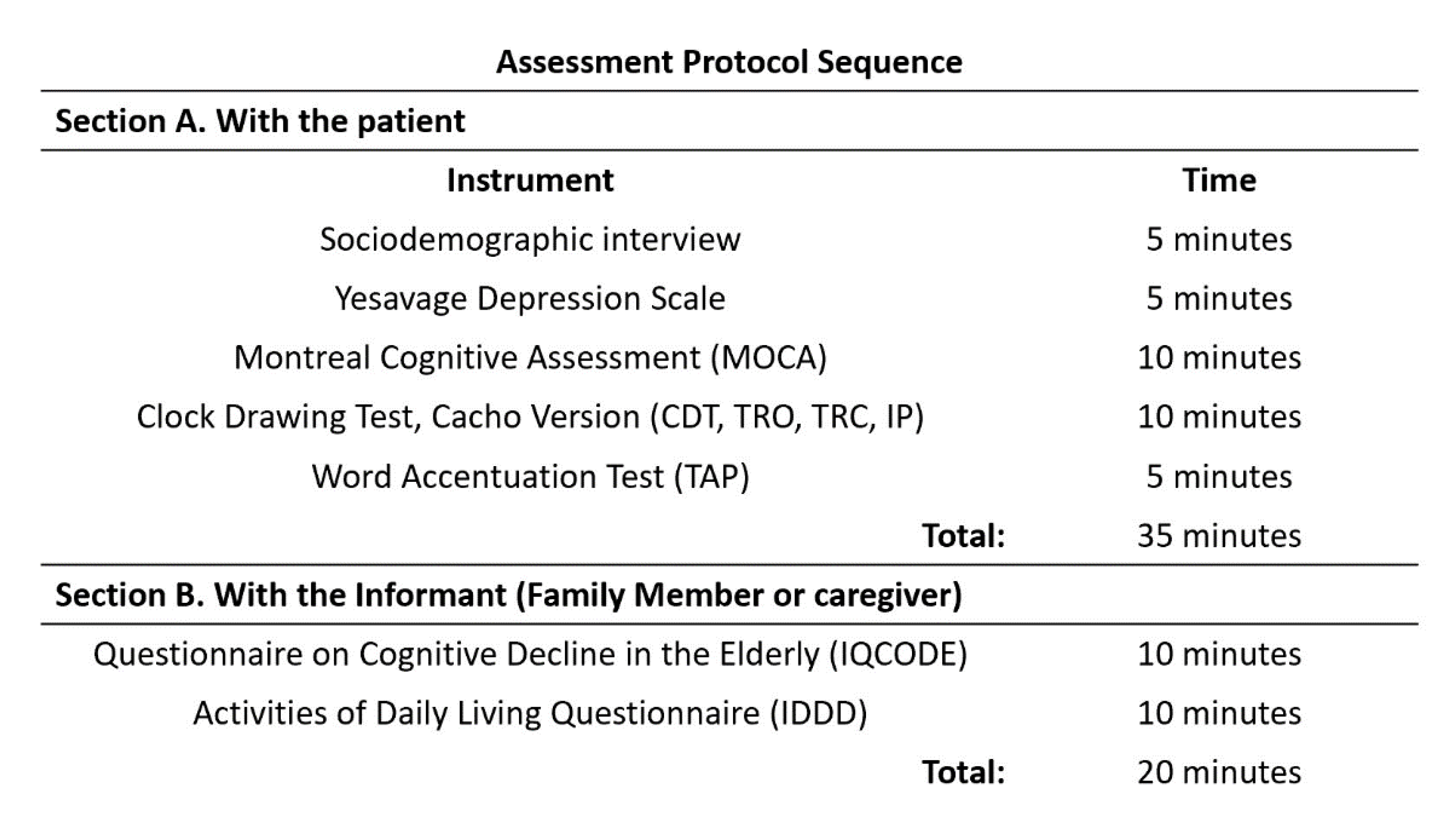

The face-to-face evaluation and the order in which the protocol was administered were the same and followed the same sequence as the online evaluation. (

Figure 1). Before the assessment, all subjects completed the informed consent form. At the end of the process, they received a report on their cognitive status with appropriate recommendations for referral to other levels of care according to their results, as specified in the protocol of the unit services.

Therefore, it should be emphasized that the protocol used in this study does not allow the diagnosis of MCI, but is used to explore indicators of vulnerability (previous stage from a prodromic MCI – early stage dementia). As described, this screening was not done solely based on the MoCA score, but with the full set of tests and sources of information (older adult and key informant). This is an important aspect to highlight as many of the studies like the one that we are presenting here are based on only one source, usually the older adult, ignoring the key fact that relevant data may be forgotten due to the amnesic problem, hence the importance of the information corroborated with the informant (relative or caregiver).

Data analysis

All results presented in this study were obtained using the IBM SPSS Statistics version 28 statistical analysis package. The significance level used for the analyses was p ≤ 0.05 and p≤ 0.01.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and the Leven test were used to test the distribution and homogeneity of the cognitive variables before statistical analysis. The results of these analyses were significant, indicating that each of the cognition status variables under study had a normal distribution and was suitable for the parametric statistical analyses.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and health variables defining the sample. Most of the subjects were women (76.4%), with higher education (41.2), living alone (62.2%), without cardiovascular risk (81.1%), diabetes (87.8%), or hypertension (77%), most of them are not taking any medication (78.4%), nor consuming alcohol (81.1%) or tobacco (95.3%).

Table 2 shows the results obtained on the different indicators of MCI of the participants from the instruments used: MoCA, CDTcm, CDTcp, IP, and the WAT, as well as the IQCODE and the IDDD.

The statistical analysis (Pearson correlation) performed to test the first objective of this study shows the relationship between the variables associated with cognitive impairment. The results show a moderate and positive correlation between MoCA, CDTcm (.743), and CDTcp (.587), which confirms that both the general cognitive assessment provided by the screening test and the additional measures (visual-constructive aspects and cognitive reserve) provide a consistent profile of the participant's risk situation or lack thereof.

Since the MoCA scores appear to have a large standard deviation,

Table 3 shows the range of scores, by educational intervals.

On the other hand, moderate and negative values were found between the MoCA and the IDDD questionnaire (-.456 p-value .001) and IQCODE (-.484 p-value .001), indicating that the results of the participant's assessment were consistent with the key informant's observations.

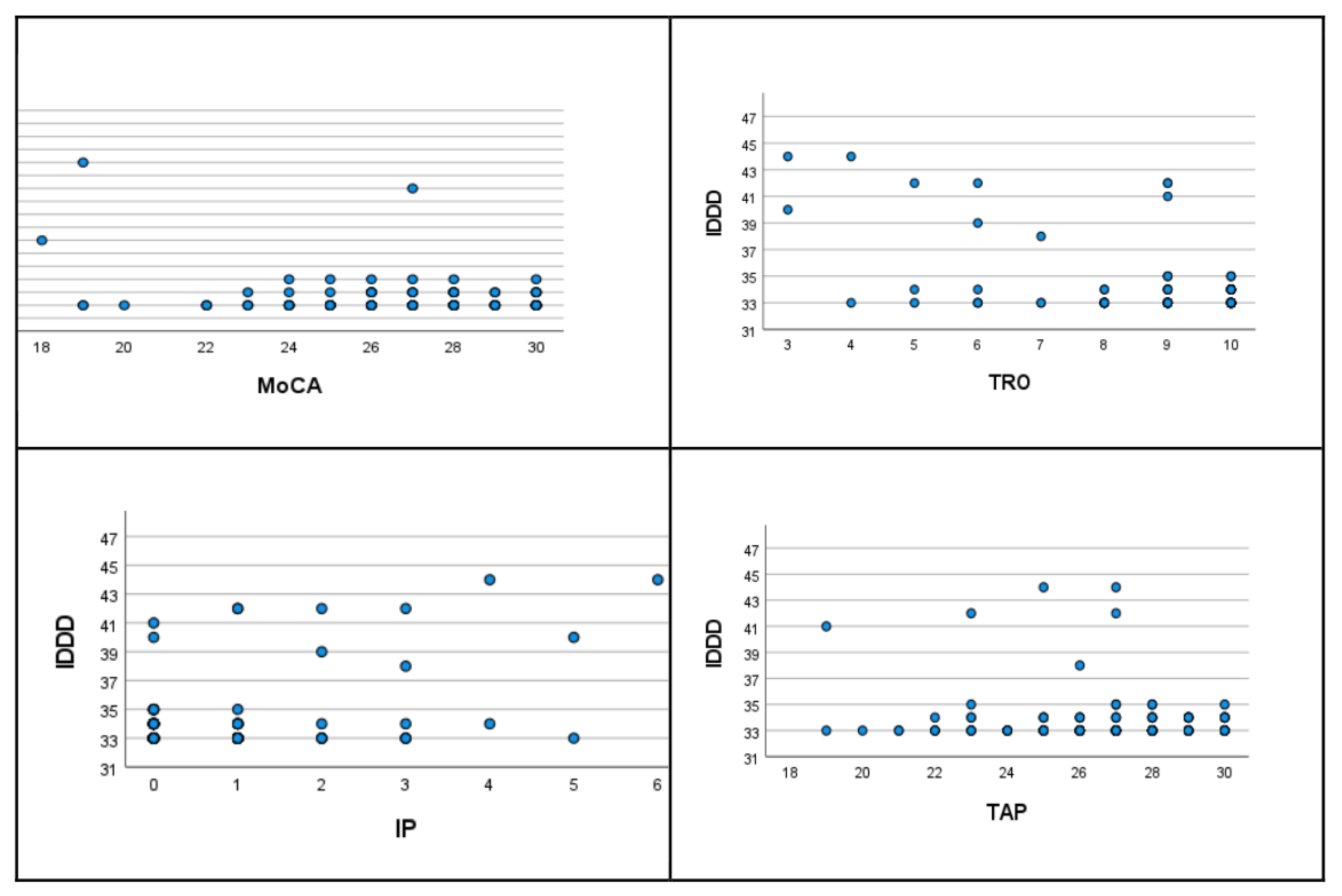

Finally, we highlight the negative correlation obtained between the CDTcm, IP, IQCODE, and IDDD scores. As can be seen in

Table 4, the most relevant associative key for the deterioration in the protocol is the correlation between the performance in the CDTcm and the IP index (-.803) resulting from comparing the drawing of the CDT cm and the CDTcp.

Also important is the association of this index with the cognitive reserve assessed with the WAT (-.417). Of lesser magnitude, but very significant, is the correlation between cognitive status according to MoCA, IP, and WAT with the key informant's assessment of the patient's cognitive decline (IQCODE .395) and autonomy (IDDD .260). These aspects are illustrated in

Figure 2.

Regarding the second objective, the statistical analyses performed (Student's t-test) show that the type of evaluation modality (face-to-face or online) does not significantly alter the results in any of the variables analyzed. Therefore, we can say that the evaluation results are not influenced by the modality chosen (

Table 5).

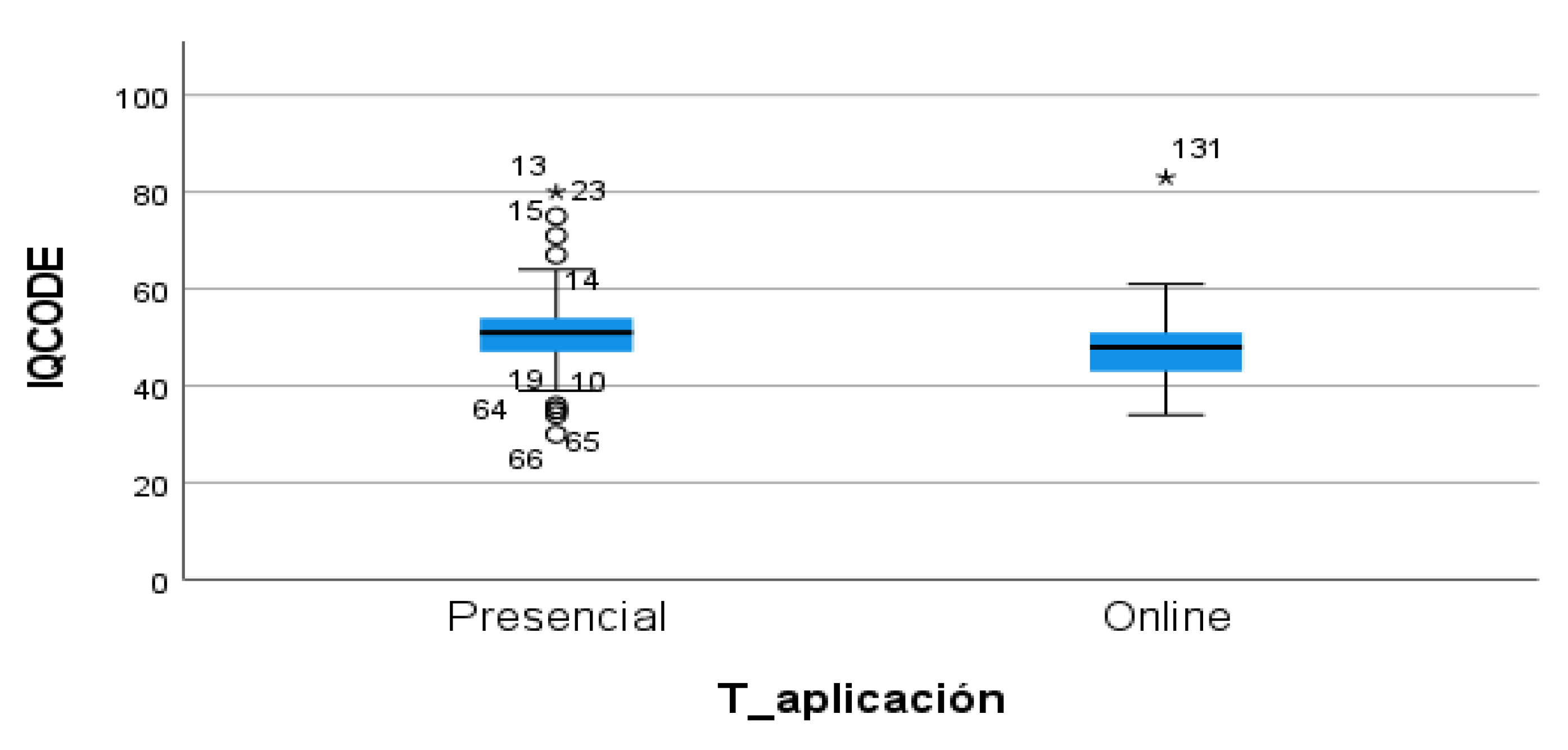

It should be noted that significant differences in the IQCODE scores were found only in the in-person modality (t=2.050 and p-value=.042). Informants of participants who attended in person had a higher perception of their relative's cognitive impairment (50.84 and SD: 8.74) than those who attended online (48.18 and SD: 6.95). Data is shown in

Figure 3.

Finally, an attempt was made to clarify the variables associated with cognitive impairment that could be predictors of cognitive impairment. For this purpose, a regression was performed with the predictor variables CDTcm, CDTcp, IP, WAT, IQCODE, and IDDD, with the criterion (dependent) variable MoCA. Of these, only the statistical solution found includes the variables WAT, IQCODE, and IDDD as part of a stable model (Y'=9.302-0.317X1 -0.017X2 +0.128X3, (2: .516 and F (p-value:) 51.273 (<.001)). (

Table 6).

Thus, sensitivity in detecting suspected MCI, according to the model results, would fall on cognitive reserve as it relates to the older adult measure and the two key informant measures (cognitive status and level of autonomy).

In addition, given that the sample has a high level of education, subsample analyses were performed in a split group for face-to-face and virtual administration for low and high education. This was done to see the differences in performance between the education groups. We used a multivariate general linear model in which we included as dependent variables the variables analyzed in the study and as independent variables the level of education (low and high) and the type of application of the workshop (face-to-face and online).

First, we checked the assumption of homoscedasticity in the multivariate vector using the box test (p=.000 <0.05), which was significant, therefore the assumption of homoscedasticity is not fulfilled for the multivariate manager. On the other hand, Leven's Contrast was calculated for the variables of the study, and significant values were found for some of the variables, so this assumption is not met CDTcm (p=.040 <0.05), CDTcp (p=.037 <0.05) and WAT (p=.001 <0.05).

However, given the balanced size of the groups (high education 63 subjects and low education 85 subjects; face-to-face 74 subjects and online 74 subjects), we can assume that the test is robust to the violation of this assumption, so we present below the results obtained from the multivariate general linear model.

Significant differences were found only in the variable "

education" (Pillai trace p=.001 <0.05), with an observed power of 0990. No significant differences were found in the assessment modality or the interaction between the two variables. In the tests of between-subjects effects, we found differences in the variables MOCA, CDTcm, IP, WAT, and IQCODE as a function of the variable education (

Table 7).

Subjects with a high level of education (university and high school) score higher on the MoCA and CDTcm than those with a low level of education (primary and secondary school) and have lower scores. Among key informants, those who are key informants of highly educated participants score higher on the WAT and lower on the IDDD than those who are key informants of participants with lower education.

Recent work confirms the role of Cognitive Reserve (CR) in cognitive and motor function [

46], a relationship that is justified as an underlying mechanism, as an opening to experience, to mitigate cognitive decline [

47]. In the preclinical stage of dementia or MCI, it is essential to develop strategies that lessen the consequences of deterioration in cellular homeostasis, brain functions, and behavioral/cognitive patterns [

48].

Increased CR counteracts age-related changes in neural activity, as noted in previous studies [

49]. This pattern of neural activity is characteristic of young adults in whom interhemispheric asymmetry does not occur. This may be related to active coping strategies and lower perceived stress in individuals with greater cognitive reserve [

50]. Studies of the brain mechanisms underlying CR [

51] also explain how a superior ability to flexibly adjust activation as the cognitive demand of the task increases (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Given the situation when COVID-19 stoke, one of the main measures to mitigate the spread of the virus in the elderly population was confinement. However, this significantly reduced the opportunities for social interaction and autonomy, and the detection of possible cases of incipient cognitive impairment. Given that an active and autonomous life can ensure better cognitive functioning and greater cognitive neuroplasticity in the elderly, the restrictions on mobility and isolation resulting from the pandemic have had the opposite effect [

26].

It is important to note that the characteristics of the sample used in this study represent a specific profile: women, with higher education, living alone, without cardiovascular risk or diabetes and hypertension, and not taking any medication or consuming alcohol or tobacco. Therefore, the results correspond to a population segment of older adults that would represent a certain "bias" of a healthy sample, unlike those obtained by other authors, where the sociodemographic characteristics or the presence of pathologies, such as diabetes, offer a less benign picture [

18,

20,

38,

46].

Regarding the first objective of this study, the results obtained support the clinical and diagnostic interest of the screening protocol, due to the relationship between the variables measured. Thus, the MOCA is a more valid screening tool than the Mini-Mental or other screening tests for the assessment of visual-constructive functions (CDTcp), an aspect already pointed out by Aguilar et al. [

39]. It is also useful to analyze the concordance with key informants, both in cognitive decline and autonomy (IQCODE and IDDD), a dimension also reflected in previous work [

42,

44]. And, very relevant is the discrepancy index, highlighted in the model of Cacho et al. [

39], because of its inverse logic, i.e., the higher the IP, the higher the risk of impairment, in this regard MOCA’s scores are less sensitives with this population.

The use of different tests in the protocol was intended to correct the limitation criticized in many studies based on a single test (the example of the Mini-Mental is very common in this field). In our case, the screening battery combines measures of cognitive performance (memory, visuoconstructive functions, etc.) with others focused on evolutionary and biographical dimensions (contextual, emotional, illness, medication use, etc.). To this end, two screening tests that are useful in the assessment of MCI were used: the MoCA, CDTcm, and CDTcp [

11,

12].

Given that, MoCA helps to find indicators of MCI rather than a formal diagnosis. In this study, three levels of MCI (zero, intermediate, high) could be obtained by combining the results of the cognitive test given to the patients (MOCA, CDTcm/cp, and WAT) with the information obtained from the key informant (IQCODE and IDDD).

Regarding the correlations between the MoCA and the CDTcm/cp, the results support the usefulness of using both tests, which could be repetitive. The CDTcm/cp, offers a complementary and more sensitive perspective than MoCA, allowing a more precise differentiation of cognitive impairment through the IP analysis [

11,

12].

Along the same lines as the Mini-Clock [

15], which is the combination of the Mini-Mental and the CT, therefore, we propose, as a complement to the MoCA, the application of the two versions of the CDTcm/cp and the IP analysis to improve the accuracy in the MCI screening.

On the other hand, it is important to note that the MoCA includes a visuospatial test that consists of drawing a cube. It has been shown that the ability to copy the cube is influenced by the level of education since this drawing is learned from childhood and tends to become automatic. This is not the case with the CDTcm/CDTcp, which is particularly dependent on the good functioning of the parietal areas of the cortex and is therefore of great differential value in screening cognitive function [

32].

The contribution of the CR measured with the WAT and correlated to visual-constructive functioning (VFC) is also significant and, as we highlighted in the results, its inverse correlation is very high [

46]. This is a consistent aspect of the buffering role that CR plays in modulating vulnerability to decline, both in the population of older adults in a situation of autonomy or institutionalization [

49], and in earlier evolutionary stages, along with other psychological factors such as a sense of purpose in life [

43]. In addition to the cognitive cues, the Rotterdam Study [

52] showed that greater cognitive and brain reserve may be protective factors against depressive events in aging.

The added value of the protocol used in this study, which combines the assessment of the older adult with data from the key informant, is consolidated by the inverse association of all the cognitive variables of the participant (MoCA, CDTcm/cp, WAT) with those of the external evaluator (IQCODE and IDDD), except, logically, with the one whose greater magnitude indicates impairment. This aspect provides the strongest argument for the need to use a hybrid protocol in MCI screening tasks, as justified by the approach of this paper and supported by previous research [

28,

36].

Regarding the second objective, the results are important to show that the scores are similar regardless of the assessment modality (in-person/online). In this line, with some of the tests used (MoCA or CDTcm/cp), the consistency index in test-retest applications is confirmed by Pérez et al. [

44].

Only the IQCODE mean is different in the face-to-face modality, which may be due to the greater perceived severity of the participant's cognitive status by the key informants. The face-to-face choice would also be justified by the consequences derived from the limitations of on-site access to the different levels of the health system, with the prevalence of telephone consultations in primary or specialized care, which would explain the opportunity offered by this resource open by the dual modality at the choice of users.

Overall, the results would confirm the validity of the protocol regardless of the application modality, this aspect has been repeatedly verified for some of the tests used (such as the MOCA or the CDTccm/cp) [

13]. The innovation in this work is the evidence for other indicators (WATS, IQCODE, IDDD) for which there are no specific results in online applications, but which have demonstrated their predictive usefulness in traditional and online assessments [

38].

Finally, the regression models used indicate that CR (WAT) in terms of older adult variables and key informant assessments of cognitive status and perceived autonomy would be most relevant for discriminating potential cases of MCI that could later evolve into dementia.

Regarding the role of CR, we reiterate the importance already reflected in the literature and supported by the enormous wealth of assessment instruments [

47]. On the second point, our work brings an element of innovation, given that the accumulated evidence on the involvement of key informants in screening tests in a combined manner is not so abundant. In most cases, epidemiologic data are based on one or another source but not on both (patients/key informants).

Many factors are identified as generators of reserve, one of which is education, but this is a construct in full development. In an inclusive line, we understand that Kempermann's [

33] proposal is currently one of the most globalized because his formulation of "embodied mind in motion" adds to the variables related to lifestyle (education, diet, non-toxic behaviors, etc.) others centered on quality of life (social engagement, autonomy, participation, or life purpose).

In our work, given that it was not possible to use biomarker indicators, we opted for the use of the WAT as a direct measure of CR, corroborated in previous research, due to its high correlation with tests of fluid and crystallized intelligence (Wechsler scales).

It should be noted, however, that not all the literature is consistent with these findings. For example, Volk et al. [

53] combined memory measures and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a large study of middle-aged Dutch adults followed for 12 years. The results suggest that a higher CR (with indicators of education and reading tests) is a better predictor of risk of impairment than the intracranial volume used in many studies.

By establishing the correlation between variables, it has been possible to identify critical variables of MCI in a way that does not represent the risk of contagion with the COVID-19 virus by doing it online during the pandemic. In addition, having an alternative tool for early detection helps to preserve CR and delay the progression of MCI to dementia in older adults [

48,

49,

50]. This adds empirical evidence for the role of cognitive reserve as a protective factor [

51] to the relationship established in the literature between cognitive status and the maintenance of executive and visual-constructive functions [

40].

5. Conclusions

The results found with the two supportive tests are of great importance, as has been reviewed in previous work, including subjective memory complaints as a warning cue [

20].

Moreover, the screening model used (cross-matching of personal cues from the older adult with the key informant) represents an innovative conceptual element by balancing attention to other cognitive domains, such as constructional and visuospatial skills, beyond memory, which is no longer the most sensitive data for detecting dementia according to DSM-5 [

17].

On the other hand, the implementation of this online protocol can solve the problem of late diagnosis of dementia, which is usually detected in very advanced stages of the disease. Therefore, the novelty of using Teleneuropsychology during the pandemic situation is supported. It is also in line with the literature on the need to incorporate ICTs in psychological assessment in general [

54]. We would like to emphasize the importance, from the point of view of professional performance, that the screening tests have been applied in strict compliance with the indications established by the APA (2020) in the field of tele-neuropsychology.

The conclusions that can be drawn from the results obtained, following the objectives set at the beginning, firstly confirm the suitability of the protocol designed, since the mix of sources of evaluation (older adults and key informants) provides significant clues that give greater certainty to the screening task. In addition, the different modalities, face-to-face or online, do not reflect changes in terms of prognostic value. In a situation such as the pandemic period, having a tool with this potential for use in cases of contact deprivation or geographical distance (rural areas) is a highly relevant contribution.

Regarding the internal structure of the variables that make up the battery of instruments, to point out the predictive capacity of the deterioration manifested by the IP between the two forms included in the CDTcm/cp (with the differential visual constructive assessment involved), the great relevance of cognitive reserve, and the high correspondence between performance measures in the older adult, which is corroborated in the cognitive assessments and the level of autonomy verified by the key informant.

The limitations of the present study are, first, related to the nature of the study, since, as a cross-sectional study, the results only allow us to reflect a glimpse of a specific evolutionary moment. It would have increased the explanatory power if a longitudinal design had been used to determine the evolutionary pattern of risk situations. We are currently conducting a longitudinal follow-up of a significant portion of the sample used, which will allow us to determine stability or change according to the typified risk assessment.

The second limitation is the strength of a screening study that does not allow for formal diagnosis. This limitation does not allow confirmation of the diagnosis of MCI nor the specific subtype of the existing typology (amnestic, multidomain, etc.). This critical screening methodology is the one we have followed in screening studies with ICTs in previous international studies [

38,

54].

Despite this limitation, and as argued by the Cognitive Decline Group of the European Innovation Partnership for Active and Healthy Ageing [

55], early detection is necessary, even if screening cannot reflect the complexity inherent in a complex clinical entity and an uneven evolutionary process in terms of the parameters involved (cognitive, executive and functional performance). In the same sense, the results of specific aspects, such as the evaluation of the convergent and discriminant validity of the online screening protocol for the detection of mild cognitive impairment in elderly people in Chile, have proven to offer very positive results [

56].

It should be noted that we have followed the considerations of previous studies to avoid contamination by false positives, it would be appropriate to expand the sample size with a representation of older adults in residences to determine differences in the parameters evaluated. Samples should also include older adults with less healthy profiles or more vulnerable socio-cultural and economic conditions. In addition to using neuropsychological screening tests, the protocol should be extended to include neuroimaging techniques or biological markers [

57,

58] that provide greater discriminative power.

Consistent with what we said about using the protocol in different countries, the accumulation of data will allow for generalization and particularization according to cross-cultural cues to expand our research. This future possibility is supported in the present work by the originality of the methodological approach (mixed assessment of MCI risk with the older adult and the key informant), technological (use of procedures based on telepsychology), psychometric (evidence of the validity of the tests regardless of the modality) and clinical (relationship between cognitive performance variables or the role of cognitive reserve as a modulator of the process).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Rosalia García-García, Lizbeth De La Torre, Jesús Cacho-Gutiérrez and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Data curation, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Beatriz Palacios-Vicario, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Formal analysis, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Beatriz Palacios-Vicario, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Funding acquisition, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco; Investigation, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Methodology, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Beatriz Palacios-Vicario, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Project administration, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Resources, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Rosalia García-García, Lizbeth De La Torre, Jesús Cacho-Gutiérrez and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Software, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco and Beatriz Palacios-Vicario; Supervision, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco; Validation, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Visualization, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco; Writing – original draft, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández; Writing – review & editing, Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Lizbeth De La Torre and Paula Prieto-Fernández. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has been funded within the framework of the agreement between the City of Salamanca and the Pontifical University of Salamanca (2020-2023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca for the favorable report on the performance of this work (registered: 12/3/2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MCI |

Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s Disease |

| MCI-amnestic |

Mild Cognitive Impairment-amnestic |

MCI-

Non amnestic |

Mild Cognitive Impairment non-amnestic |

| NIA-AAA |

National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test |

| CT |

Clock Test |

| APA |

American Psychological Association |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Revision |

| ICD-11 |

International of Diseases 11th Revision |

| BPA |

Boston Process Approach |

| DLAs |

Daily Living Activities |

| ICTs |

Information and communication technologies |

| SMC |

Subjective Memory Complaints |

| MU |

Memory Unit |

| UPSA |

Pontifical University of Salamanca |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| YPD |

Yesavage Depression Scale |

| CDT |

Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version |

| WAT |

Word Accentuation Test |

| IQCODE |

Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly |

| IDDD |

Interview for Deterioration in Daily Living in Dementia |

| ICC |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| CDTcm |

Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version on Command |

| CDTcp |

Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version copied |

| WAIS-IV |

Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th Edition |

| IP |

Improvement Pattern of the Clock Drawing Test Cacho Version |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| CR |

Cognitive Reserve |

| CDTcm/cp |

Clock Drawing Test Cacho version on command and copied |

| VFC |

Visual Constructive Functions |

References

- Borrás Blasco C, Viña Ribes J. Neurofisiología y envejecimiento. Concepto y bases fisiopatológicas del deterioro cognitivo. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología. 2016 Jun;51:3–6.

- Cancino M, Rehbein L. Factores de riesgo y precursores del Deterioro Cognitivo Leve (DCL): Una mirada sinóptica. Terapia psicológica. 2016 Dec;34(3):183–9. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P, Morais JA, & Webster C. 2021. World Alzheimer Report 2021, Abridged version: Journey through the diagnosis of dementia. London, England: Alzheimer's Disease International.

- González Martínez P, Oltra Cucarella J, Sitges Maciá E, Bonete López B. Revisión y actualización de los criterios de deterioro cognitivo objetivo y su implicación en el deterioro cognitivo leve y la demencia. Revista de Neurología. 2021;72(08):288.

- Petersen, RC. Mild Cognitive Impairment. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2016 Apr;22(2, Dementia):404–18. [CrossRef]

- Feldberg C, Tartaglini MF, Hermida PD, Moya-García L, Licenciada-Caruso D, Stefani D, et al. El rol de la reserva cognitiva en la progresión del deterioro cognitivo leve a demencia: un estudio de cohorte. Neurología Argentina. 2021 Jan;13(1):14–23.

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Archives of Neurology. 1999 Mar 1;56(3):303.

- Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Geda YE, Ivnik RJ, et al. Mild Cognitive Impairment. Archives of Neurology [Internet]. 2009 Dec 1;66(12). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3081.

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia [Internet]. 2011 May;7(3):270–9. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect. 1552.

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia [Internet]. 2011 May;7(3):263–9. Available from: https://www.alzheimersanddementia. 1552.

- Martin E, Velayudhan L. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Literature Review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2020 Apr 14;1–13.

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 TM guidebook the essential companion to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition. 5th ed. Washington, DC American Psychiatric Publishing; 2022.

- Giebel CM, Challis DJ, Montaldi D. A revised interview for deterioration in daily living activities in dementia reveals the relationship between social activities and well-being. Dementia. 2016 Jul 27;15(5):1068–81.

- González Palau F, Buonanotte F, Cáceres MM. Del deterioro cognitivo leve al trastorno neurocognitivo menor: avances en torno al constructo. Neurología Argentina. 2015 Jan;7(1):51–8.

- Ávila-Villanueva M, Rebollo-Vázquez A, Ruiz-Sánchez de León JM, Valentí M, Medina M, Fernández-Blázquez MA. Clinical Relevance of Specific Cognitive Complaints in Determining Mild Cognitive Impairment from Cognitively Normal States in a Study of Healthy Elderly Controls. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2016 Oct 4;8.

- Denney DA, Prigatano GP. Subjective ratings of cognitive and emotional functioning in patients with mild cognitive impairment and patients with subjective memory complaints but normal cognitive functioning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2019 Apr 8;41(6):565–75.

- Mitchell AJ, Beaumont H, Ferguson D, Yadegarfar M, Stubbs B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2014 Sep 13;130(6):439–51.

- Rojas-Zepeda C, López-Espinoza M, Cabezas-Araneda B, Castillo-Fuentes J, Márquez-Prado M, Toro-Pedreros S, Vera-Muñoz M. Factores de riesgo sociodemográficos y mórbidos asociados a deterioro cognitivo leve en adultos mayores. Cuadernos de Neuropsicología/Panamerican Journal of Neuropsychology. 2021;15(2).

- Borda Miguel Germán, Ruíz de Sánchez Carolina, Gutiérrez Santiago, Samper-Ternent Rafael, Cano-Gutiérrez Carlos. Relación entre deterioro cognoscitivo y actividades instrumentales de la vida diaria: Estudio SABE-Bogotá, Colombia. Acta Neurol Colomb. [Internet]. 2016 Jan [cited 2023 Nov 04] ; 32( 1 ): 27-34. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-87482016000100005&lng=en.

- Ruiz-Sánchez de León, JM. Estimulación cognitiva en el envejecimiento sano, el deterioro cognitivo leve y las demencias: estrategias de intervención y consideraciones teóricas para la práctica clínica. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología. 2012 Apr;32(2):57–66.

- Montenegro Peña M, Montejo Carrasco P, Llanero Luque M, Reinoso García AI. Evaluación y diagnóstico del deterioro cognitivo leve. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatría y Audiología [Internet]. 2012 Apr 1 [cited 2021 Apr 7];32(2):47–56. Available from: https://www.elsevier. 0214.

- Araújo JR, Martel F, Borges N, Araújo JM, Keating E. Folates and aging: Role in mild cognitive impairment, dementia and depression. Ageing Research Reviews. 2015 Jul;22:9–19.

- Frutos Alegría MaT, Moltó Jordà JM, Morera Guitart J, Sánchez Pérez A, Ferrer Navajas M. Perfil neuropsicológico del deterioro cognitivo leve con afectación de múltiples áreas cognitivas. Importancia de la amnesia en la distinción de dos subtipos de pacientes. Revista de Neurología. 2007;44(08):455.

- Vicente Arruebarrena A, Sánchez Cabaco A. La soledad y el aislamiento social en las personas mayores. studiazamo [Internet]. 14 de enero de 2021 [citado 4 de noviembre de 2023];19:15-32. Disponible en: https://revistas.uned.es/index. 2936.

- Antonio Sánchez Cabaco, Marina Wöbbeking Sánchez, Mejía-Ramírez M, Urchaga D, Castillo-Riedel E, Bonete-López B. Mediation effects of cognitive, physical, and motivational reserves on cognitive performance in older people. Frontiers in Psychology. 2023 Jan 17;13.

- Kempermann, G. Embodied Prevention. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022 Mar 4;13.

- Amieva H, Retuerto N, Hernandez-Ruiz V, Meillon C, Dartigues JF, Pérès K. Longitudinal Study of Cognitive Decline before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the PA-COVID Survey. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2022 Feb 16;1–7.

- Xue H, Sun Q, Liu L, Zhou L, Liang R, He R, et al. Risk factors of transition from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease and death: A cohort study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2017 Oct;78:91–7.

- Cubillo-Leivas1 AM, Olivares-Olivares1 P, Rosa-Alcázar1 Á. Telepsychological Mobile Applications in the Spanish Android Market. [cited 2022 Nov 23]; Available from: https://www.psicothema.com/pdf/4771.

- Sánchez Cabaco A, De La Torre L, Alvarez Núñez DN, Mejía Ramírez MA, Wöbbeking Sánchez M. Tele neuropsychological exploratory assessment of indicators of mild cognitive impairment and autonomy level in Mexican population over 60 years old. PEC Innovation [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2023 Jun 4];2:100107. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect. 2772.

- Aguilar-Navarro SG, Mimenza-Alvarado AJ, Palacios-García AA, Samudio-Cruz A, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez LA, Ávila-Funes JA. Validez y confiabilidad del MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) para el tamizaje del deterioro cognoscitivo en méxico. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría. 2018 Oct;47(4):237–43.

- Cacho JL, Ricardo García García, Bernardino Fernández-Calvo, Gamazo S, Rodríguez-Pérez R, Almeida A, et al. Improvement Pattern in the Clock Drawing Test in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. European Neurology. 2005 Jan 1;53(3):140–5.

- Pluck, Graham & Almeida-Meza, Pamela & Andrea Gonzalez-Lorza, & A. Muñoz-Ycaza, Rafael & Trueba, Ana. (2017). Estimación de la Función Cognitiva Premórbida con el Test de Acentuación de Palabras. Estimation Of Premorbid Cognitive Function With The Word Accentuation Test. Revista Ecuatoriana de Neurologia. 26. 226-234.

- Jorm AF, Jacomb PA. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): socio-demographic correlates, reliability, validity and some norms. Psychological Medicine. 1989 Nov;19(4):1015–22.

- Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The heart’s content: The association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychological Bulletin. 2012 Jul;138(4):655–91.

- Peres K, Chrysostome V, Fabrigoule C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Barberger-Gateau P. Restriction in complex activities of daily living in MCI: Impact on outcome. Neurology. 2006 Aug 7;67(3):461–6.

- Atención a las necesidades comunitarias para la salud. 2017.

- Bilder RM, Postal KS, Barisa M, Aase DM, Cullum CM, Gillaspy SR, et al. Inter Organizational Practice Committee Recommendations/Guidance for Teleneuropsychology in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic†. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2020 Jul 15;35(6):647–59.

- Pal K, Mukadam N, Petersen I, Cooper C. Mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia in people with diabetes, prediabetes and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology [Internet]. 2018 Sep 4;53(11):1149–60. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10. 1007.

- Vega Alonso T, Miralles Espí M, Mangas Reina JM, Castrillejo Pérez D, Rivas Pérez AI, Gil Costa M, et al. Prevalencia de deterioro cognitivo en España. Estudio Gómez de Caso en redes centinelas sanitarias. Neurología [Internet]. 2018 Oct 1 [cited 2022 Jan 24];33(8):491–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect. 0213.

- Pérez Delgadillo, Paula & Usuga, Daniela & Arango-Lasprilla, Juan. (2021). Teleneuropsicología en países de habla hispana: Una mirada crítica al uso de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en la evaluación neuropsicológica.

- Parsey CM, Schmitter-Edgecombe M. Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses of the Clock Drawing Test in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer Disease: Evaluation of a Modified Scoring System. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2011 ;24(2):108–18. 5 May.

- Wöbbeking-Sánchez M, Bonete-López B, Cabaco AS, Urchaga-Litago JD, Afonso RM. Relationship between Cognitive Reserve and Cognitive Impairment in Autonomous and Institutionalized Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Aug 10;17(16):5777.

- Cattaneo G, Solana-Sánchez J, Abellaneda-Pérez K, Portellano-Ortiz C, Delgado-Gallén S, Alviarez Schulze V, et al. Sense of Coherence Mediates the Relationship Between Cognitive Reserve and Cognition in Middle-Aged Adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022 Mar 28;13.

- Schade N, Medina F, Ramírez-Vielma R, Sanchez-Cabaco A, De La L. ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 4]. Available from: https://www.sonepsyn.cl/uploads/60-4-4.

- García-García-Patino R, Benito-León J, Mitchell AJ, Pastorino-Mellado D, García García R, Ladera-Fernández V, et al. Memory and Executive Dysfunction Predict Complex Activities of Daily Living Impairment in Amnestic Multi-Domain Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020 Jun 2;75(3):1061–9.

- Nogueira J, Gerardo B, Santana I, Simões MR, Freitas S. The Assessment of Cognitive Reserve: A Systematic Review of the Most Used Quantitative Measurement Methods of Cognitive Reserve for Aging. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022 Mar 31;13.

- López ÁG, Calero MD. Predictores del deterioro cognitivo en ancianos. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología [Internet]. 2009 Jul;44(4):220–4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect. 0211.

- Perrote FM, Brochero NN, Concari IA, García IE, Assante ML, Lucero CB. Asociación entre pérdida subjetiva de memoria, deterioro cognitivo leve y demencia. Neurología Argentina. 2017 Jul;9(3):156–62.

- Zancada-Menéndez C, Sampedro-Piquero P, Begega A, López L, Arias JL. Atención e inhibición en el Deterioro Cognitivo Leve y Enfermedad de Alzheimer. Escritos de Psicología / Psychological Writings. 2013;6(3):43–50.

- Kochhann R, Bartrés-Faz D, Fonseca RP, Stern Y. Editorial: Cognitive reserve and resilience in aging. Frontiers in Psychology. 2023 Jan 5;13.

- Elosua P, Aguado D, Fonseca-Pedrero E, Abad F, Santamaría P. New Trends in Digital Technology-Based Psychological and Educational Assessment. Psicothema [Internet]. 2023;35(1):50–7. Available from: https://redined.educacion.gob.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11162/240307/50-57_v35n1.pdf?

- Ferrer-Cairols I, Montoliu T, Crespo-Sanmiguel I, Pulopulos MM, Hidalgo V, Gómez E, et al. Depression and Suicide Risk in Mild Cognitive Impairment: The Role of Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers. Psicothema [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2023 Jan 13];34(4):553–61. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. 3626.

- Stokin GB, Krell-Roesch J, Petersen RC, Geda YE. Mild Neurocognitive Disorder: An Old Wine in a New Bottle. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015 Sep-Oct;23(5):368-76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, A., MD. (2023, ). Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA) test for dementia. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth. 17 August 9861. [Google Scholar]

- Yener GG, Emek-Savaş DD, Lizio R, Çavuşoğlu B, Carducci F, Ada E, Güntekin B, Babiloni CC, Başar E. Frontal delta event-related oscillations relate to frontal volume in mild cognitive impairment and healthy controls. Int J Psychophysiol. 2016 May;103:110-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiloni C, Frisoni G, Steriade M, Bresciani L, Binetti G, Del Percio C, Geroldi C, Miniussi C, Nobili F, Rodriguez G, Zappasodi F, Carfagna T, Rossini PM. Frontal white matter volume and delta EEG sources negatively correlate in awake subjects with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006 May;117(5):1113-29. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fide E, Yerlikaya D, Güntekin B, Babiloni C, Yener GG. Coherence in event-related EEG oscillations in patients with Alzheimer's disease dementia and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Cogn Neurodyn. 2023 Dec;17(6):1621-1635. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).