Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

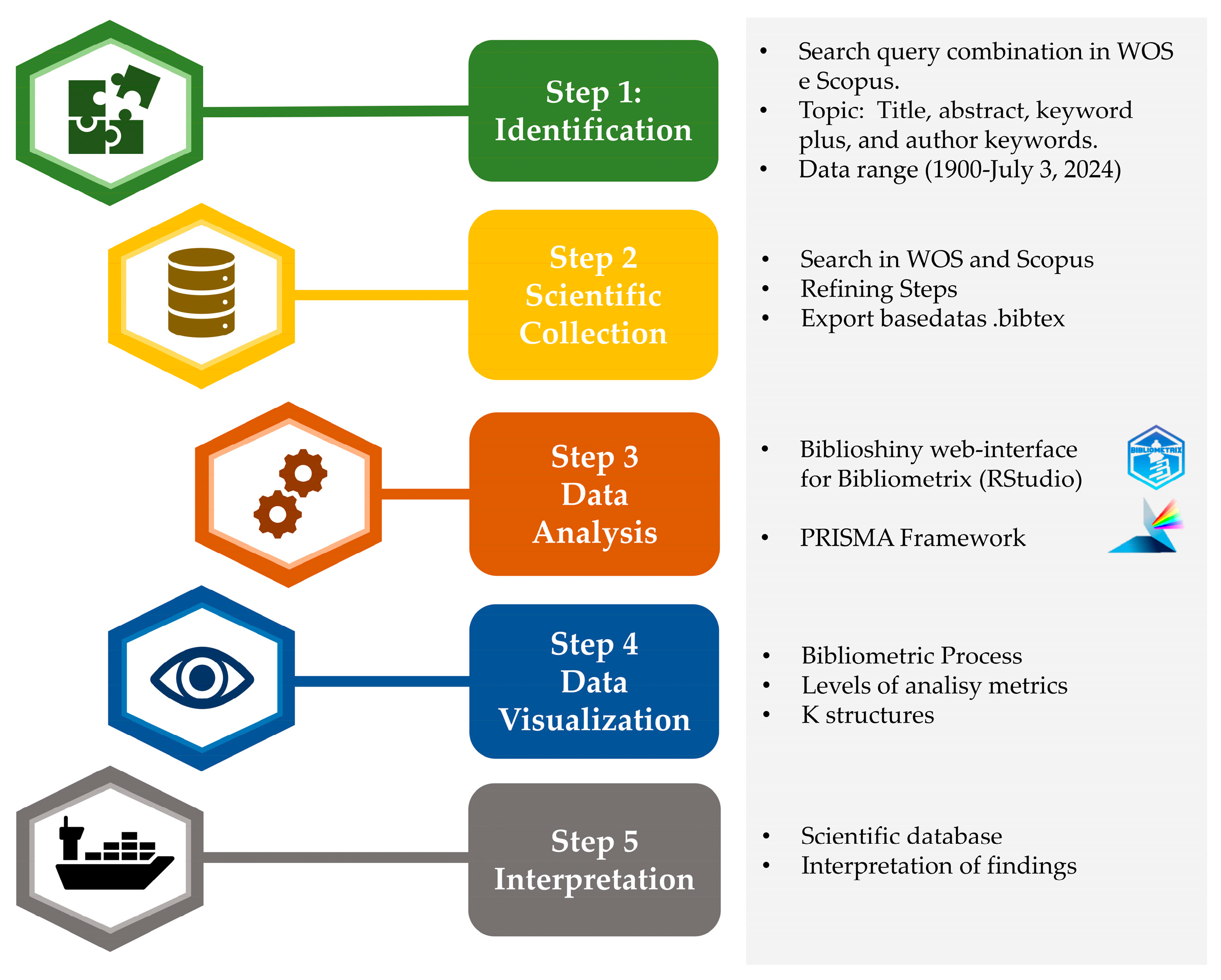

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bibliometric method

2.1.1. Step 1: Search strategy

- Key question: “In the maritime-port logistics interface, how are Spatial Data Infrastructures (SDI) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) integrated into collaborative geovisualization platforms?”. In a systemic review, the key question aims to provide a holistic understanding of the theoretical, practical aspects and ideas of the application of GIS in the monitoring, sensing and analysis of maritime spatial management, to support researchers and experts in identifying future research directions.

2.1.2. Step 2: Data collection

2.1.3. Step 3: Data analysis

2.1.4. Data Visualization

2.1.5. Step 4. Interpretation

3. Results

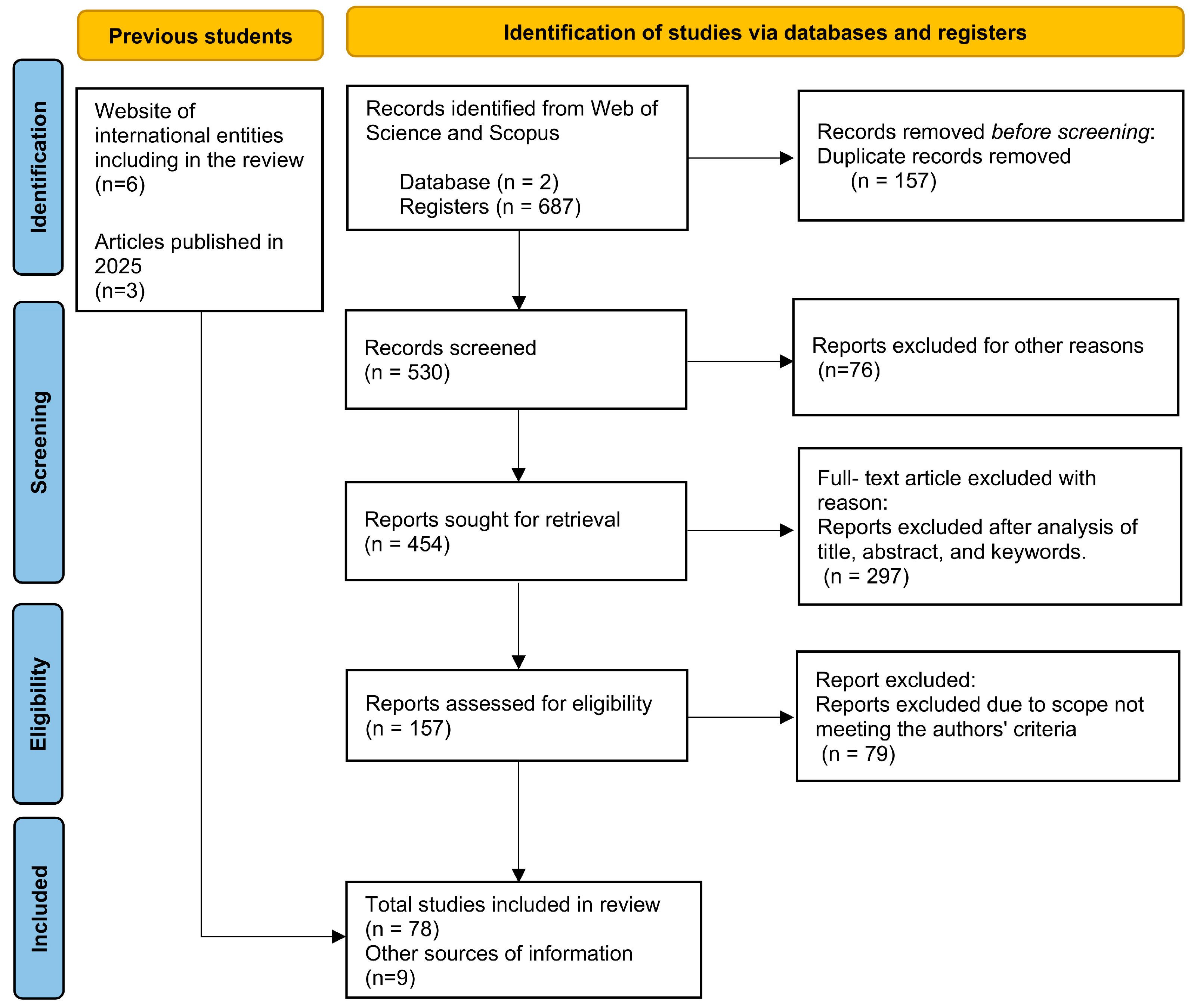

3.1. Bibliometric analysis

3.1.1. Descriptive bibliometric analysis

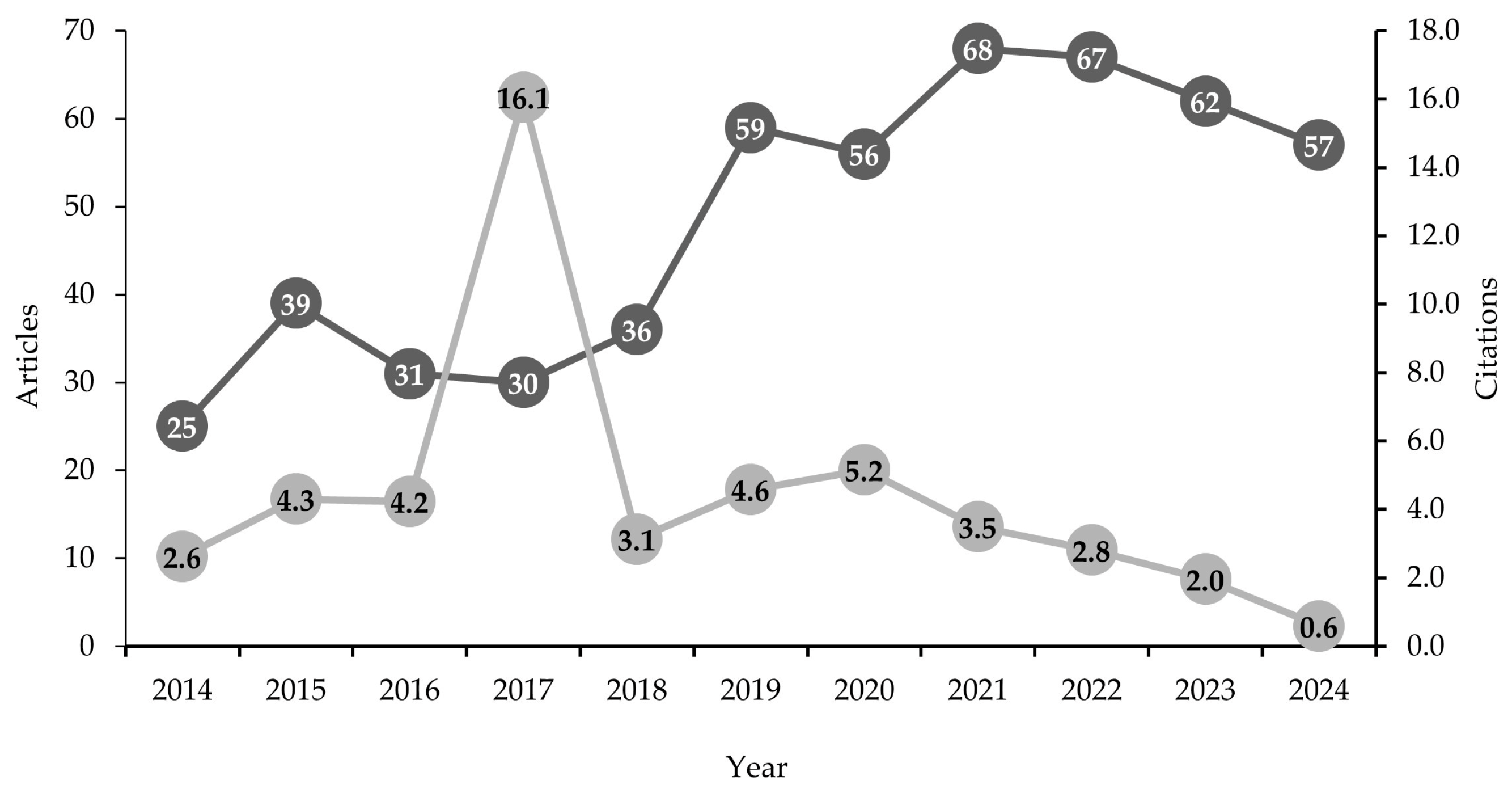

3.1.2. Distribution of annual documents and citations

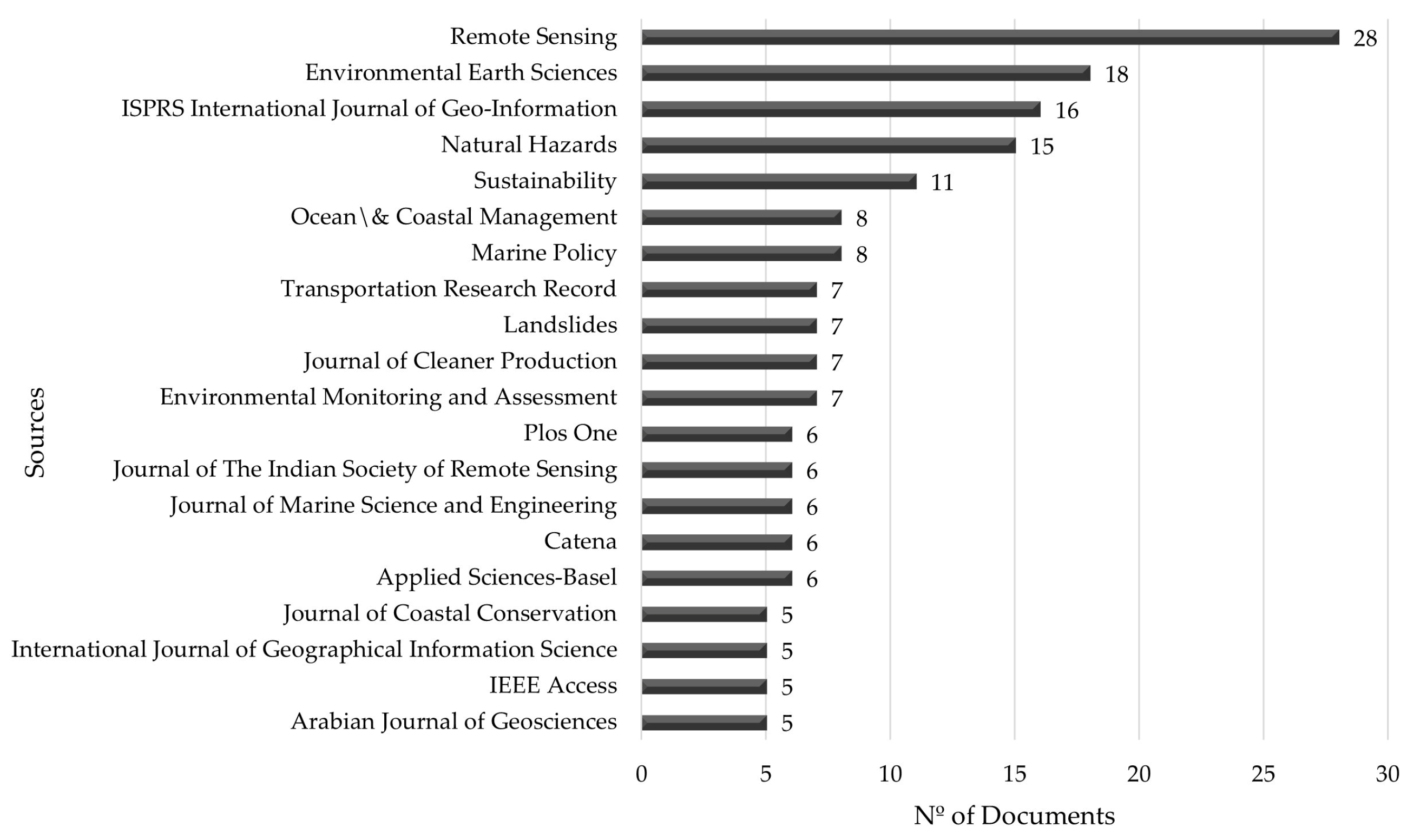

3.1.3. Most influential journals

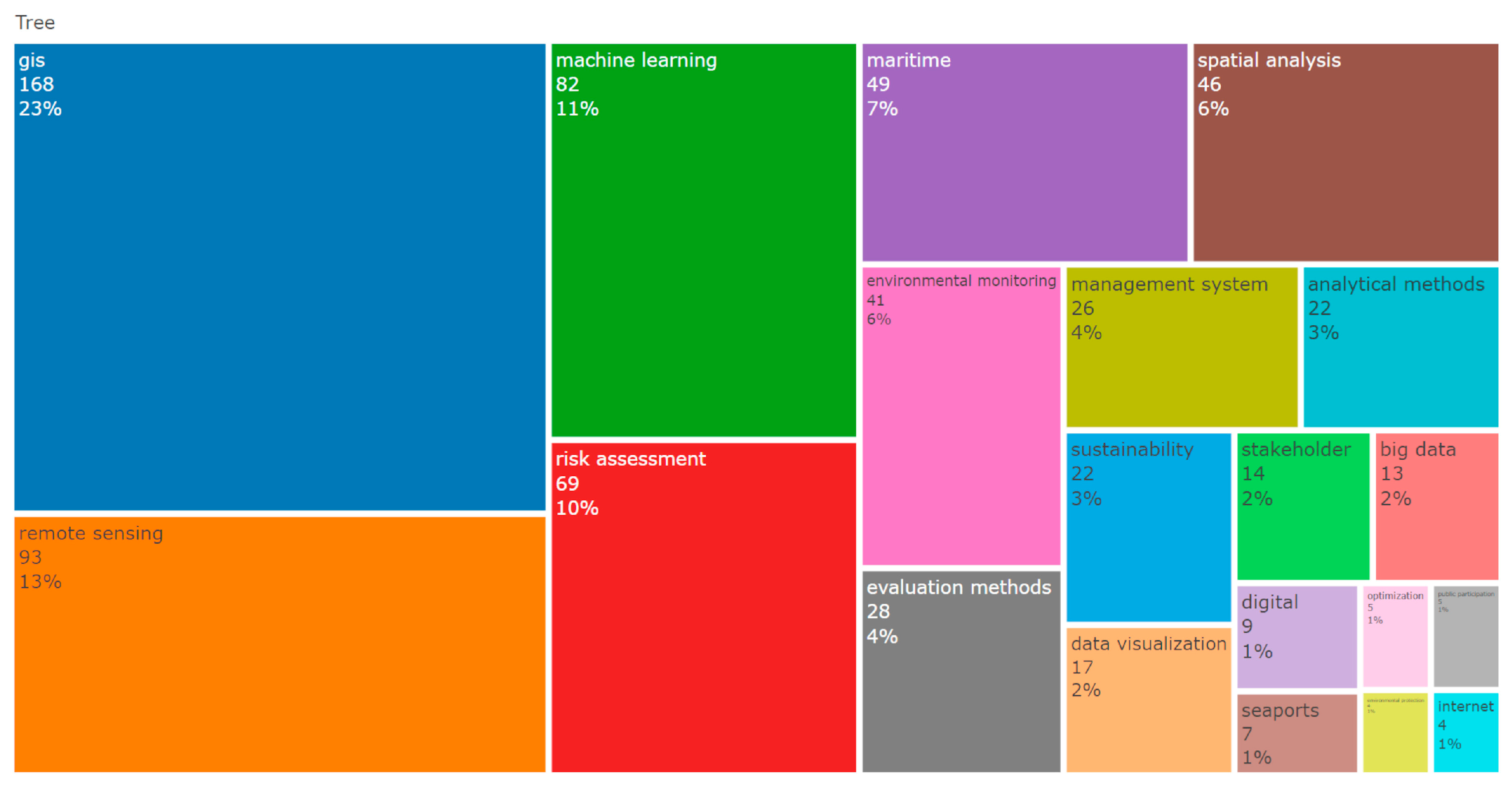

3.1.4. Authors' keywords

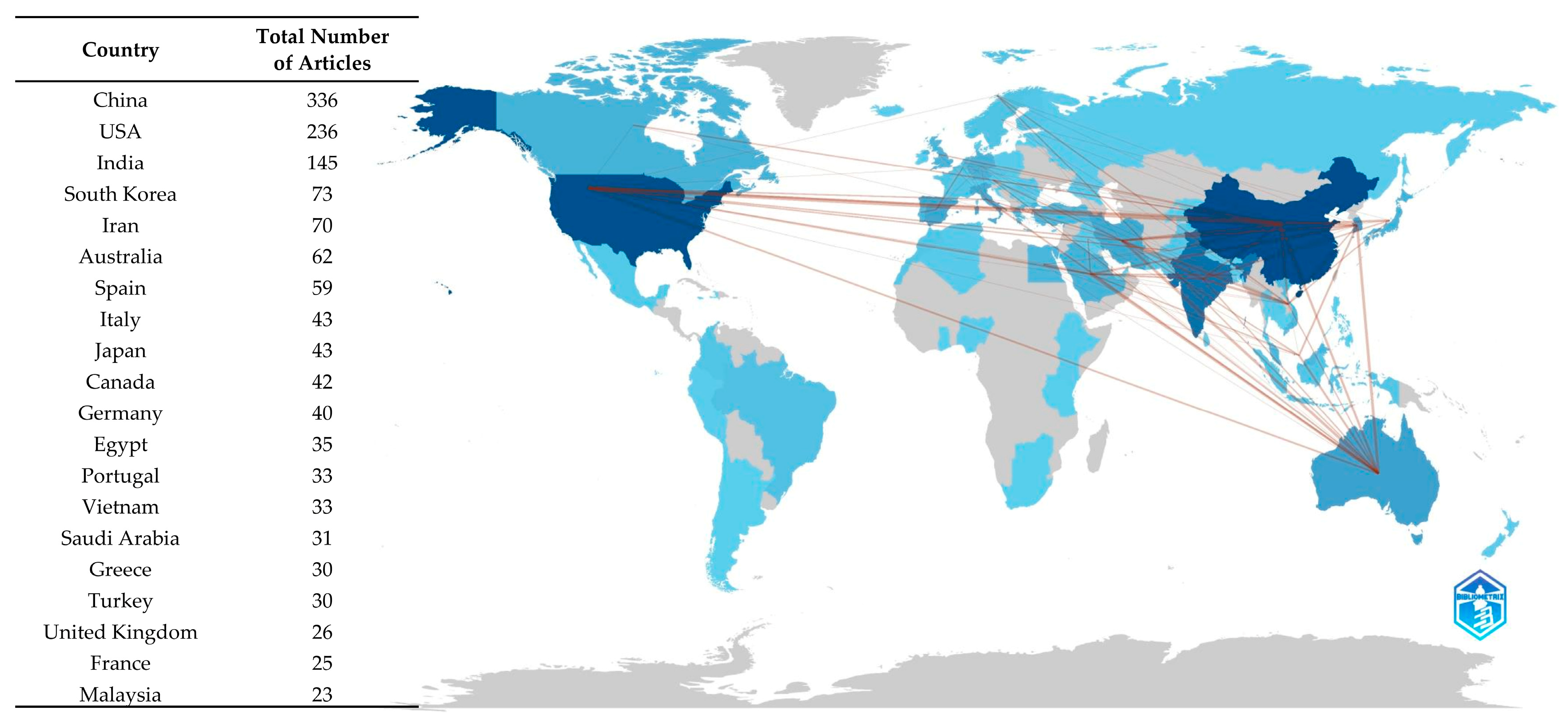

3.1.5. Mapping scientific collaboration between countries

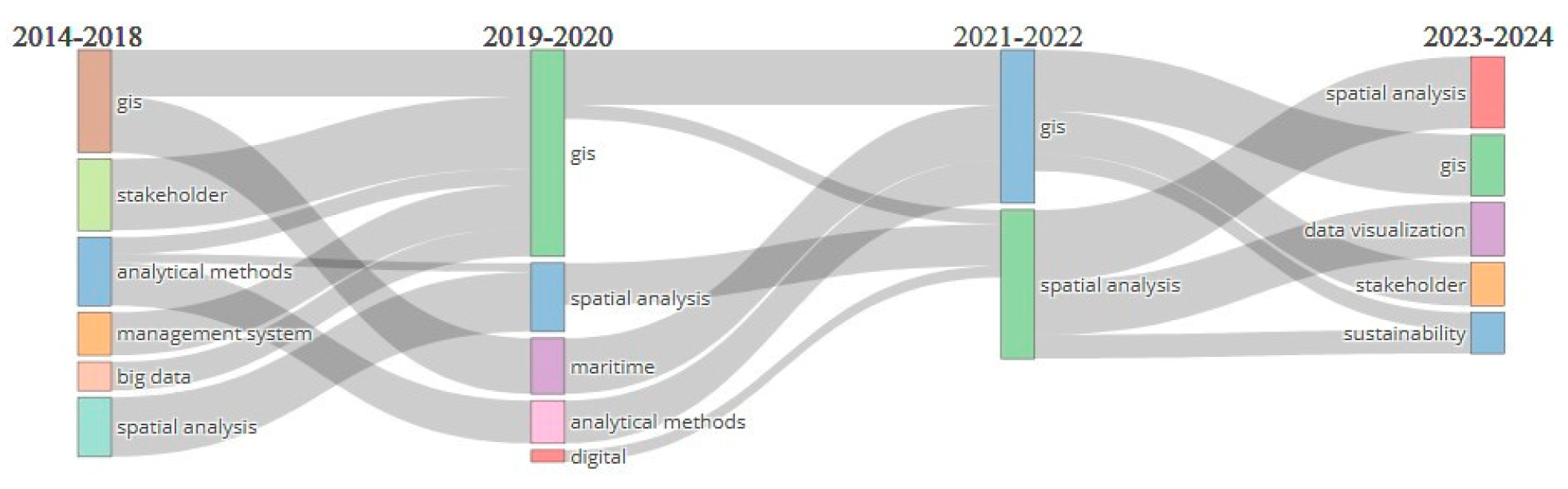

3.1.6. Evolution of the main themes and trends

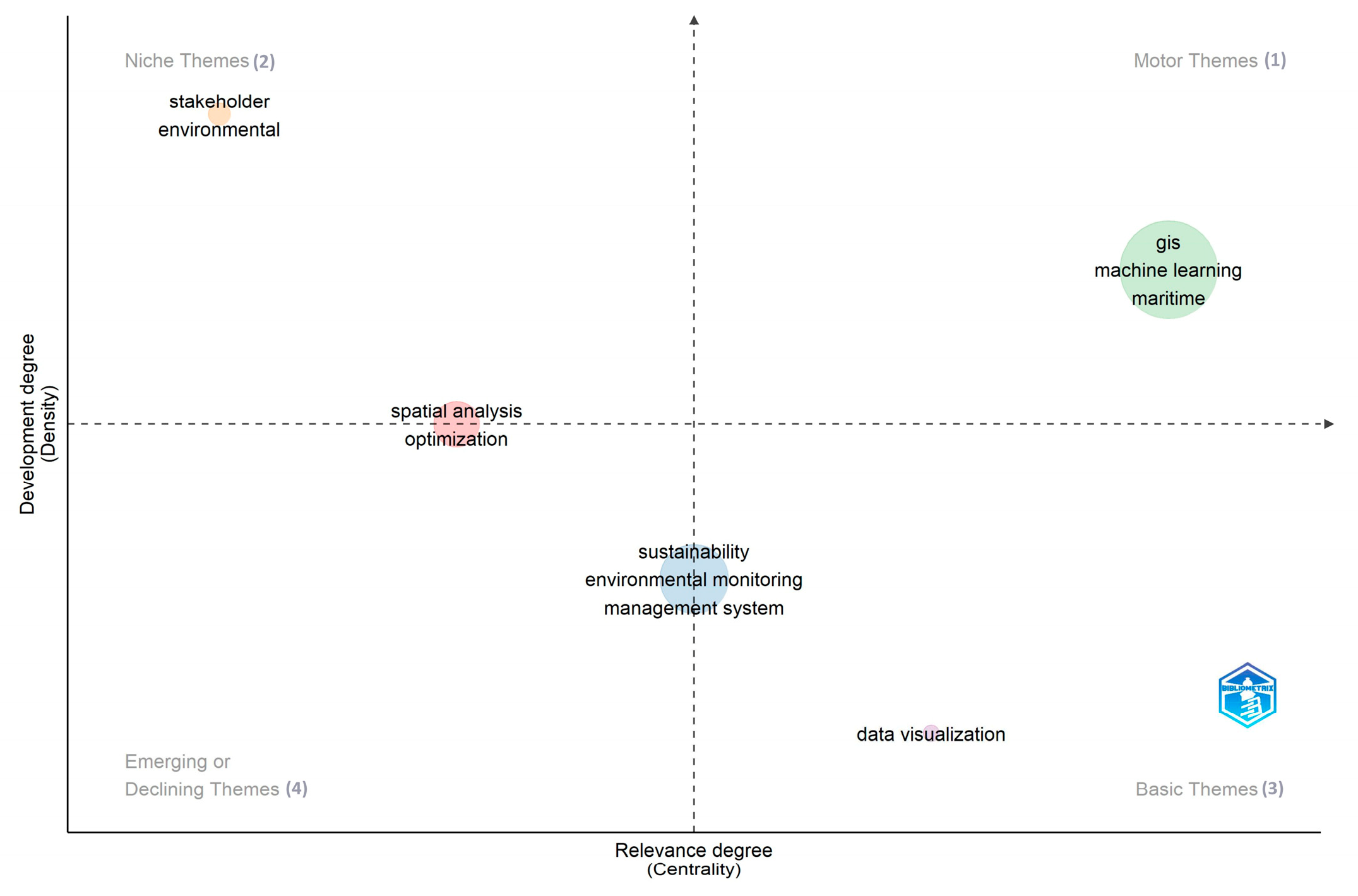

4. Discussion

4.1. Thematic Analysis

4.1.1. Spatial data interoperability infrastructures

4.1.2. GIS in the maritime sector

4.1.3. Implementation of digital technologies and artificial intelligence

4.1.4. Challenges and Trends in Maritime Information System Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Global Maritime Trade Could Suffer Biggest Decline in Decades in 2023. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Wu, F.; Bai, J.; Zhu, B.; Ma, W.; Sun, J.; Zheng, G. Reviewing Geo-Information Science for Port Information Management in China. In Proc. ICTIS 2013: Improving Multimodal Transp. Syst.—Information, Safety, and Integration, Chengdu, China, 2013; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2013; pp. 2139-2145. [CrossRef]

- Ray, Cyril; Dréo, Richard; Camossi, Elena; Jousselme, Anne-Laure; Iphar, Clément. Heterogeneous Integrated Dataset for Maritime Intelligence, Surveillance, and Recon-naissance. Data Brief 2019, 25, 104141. [CrossRef]

- Zrodowski, C.; Kniat, A.; Pyszko, R. Geographic Information System (GIS) Tools for Aiding Development of Inland Waterways Fleet. Pol. Marit. Res. 2006, 13(S2), 102–112. Available online: https://journal.mostwiedzy.pl/pmr/article/view/1269 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- McCabe, R.; Flynn, B. Under the radar: Ireland, maritime security capacity, and the governance of subsea infrastructure. Eur. Secur. 2023, 33, 324–344. [CrossRef]

- Ovando, Daniel; Bradley, Darcy; Burns, Echelle; Thomas, Lennon; Thorson, James T. Simulating Benefits, Costs and Trade-offs of Spatial Management in Marine Social-ecological Systems. Fish Fish. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bonnevie, Ida Maria; Hansen, Henning Sten; Schrøder, Lise. SEANERGY - A Spatial Tool to Facilitate the Increase of Synergies and to Minimise Conflicts Between Human Uses at Sea. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kao, Sheng-Long; Chang, Ki-Yin; Hsu, Tai-Wen. A Marine GIS-based Alert System to Prevent Vessels Collision with Offshore Platforms. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Lipeng; Zhang, Zhi; Zhu, Qidan; Ma, Shan. Ship Route Planning Based on Dou-ble-Cycling Genetic Algorithm Considering Ship Maneuverability Constraint. IEEE Ac-cess 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fagerholt, Kjetil; Lindstad, Haakon. TurboRouter: An Interactive Optimization-Based Decision Support System for Ship Routing and Scheduling. Mar. Econ. Logist. 2007, 9, 214-233. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, X. A Short-Term Vessel Traffic Flow Prediction Based on a DBO-LSTM Model. Sustainability. 2024, 16, 5499. [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.-L.; Lee, M.-C.; Chang, L.; Huang, J.-C. Development and Application of an Advanced Automatic Identification System (AIS)-Based Ship Trajectory Extraction Framework for Maritime Traffic Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1672. [CrossRef]

- Veldman, S.; Buckmann, E. A model on container port competition : an application for the West European container hub-ports. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2003, 5, 3–22. [CrossRef]

- Benedecti, R.C.; Silva, V.M.D.; da Costa, G.A.A. Integrated simulation of an inland container terminal and waterway service for enhancing the maritime supply chain connectivity between Joinville and Itapoá Port. Lat. Am. Transp. Stud. 2024, 2, 100019. [CrossRef]

- Önden, İ.; Pamucar, D.; Deveci, M.; As, Y.; Birol, B.; Yıldız, F.Ş. Prioritization of transfer centers using GIS and fuzzy Dombi Bonferroni weighted Assessment (DOBAS) model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121827. [CrossRef]

- Claramunt, C.; Devogele, T.; Fournier, S.; Noyon, V.; Petit, M.; Ray, C. Maritime GIS: From monitoring to simulation systems. In Information Fusion and Geographic Information Systems, Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Popovich, V.V., Schrenk, M., Korolenko, K.V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 34–44. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, H.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Liu, K.; Ng, A.K.Y.; Chen, W.; Liao, Q.; Dulebenets, M.A. A Geographic Information System (GIS)-Based Investigation of Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Pirate Attacks in the Maritime Industry. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2295. [CrossRef]

- Halder, B.; Juneng, L.; Abdul Maulud, K.N.; et al. Remote Sensing-Based Decadal Landform Monitoring in Island Ecosystem. J. Coast. Conserv. 2024, 28, 74. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Umprasoet, W.; Sun, Y.; Plathong, S.; Jantharakhantee, C.; Zhang, Z. Integrating Issue-Oriented Solution of Marine Spatial Planning (MSP): A Case Study of Koh Sichang in Thailand. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 258, 107381. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Nanson, R.A.; McNeil, M.; Wenderlich, M.; Gafeira, J.; Post, A.L.; Nichol, S.L. Rule-Based Semi-Automated Tools for Mapping Seabed Morphology from Bathymetry Data. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Parra, L. Remote Sensing and GIS in Environmental Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8045. [CrossRef]

- Photis, M.; Panayides, M.; Song, D.-W. Port Integration in Global Supply Chains: Measures and Implications for Maritime Logistics. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2009, 12, 133–145. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, J.; Mangaiyarkarasi, V.; Mahalakshmi, S.; Sandhiya, Karthigeyan, G.; Var-sha, G. Development of an Integrated Water Body Surveillance System for Environmen-tal Monitoring and Resource Management. Proceedings of IC3IoT. 2024. 1–5. doi:10.1109/ic3iot60841.2024.10550378.

- Huang, I.-L.; Lee, M.-C.; Chang, L.; Huang, J.-C. Development and Application of an Advanced Automatic Identification System (AIS)-Based Ship Trajectory Extraction Framework for Maritime Traffic Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1672. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, M.; Aziz, F.; Yap, P.S. Digitalization and Innovation in Green Ports: A Review of Current Issues, Contributions and the Way Forward in Promoting Sustainable Ports and Maritime Logistics. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169075. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.R.; Zhang, W.; Shi, W. A Sustainable Port-Hinterland Container Transport System: The Simulation-Based Scenarios for CO2 Emission Reduction. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 9444. [CrossRef]

- Buonomano, A.; Del Papa, G.; Giuzio, G.F.; Palombo, A.; Russo, G. Future Pathways for Decarbonization and Energy Efficiency of Ports: Modelling and Optimization as Sustainable Energy Hubs. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138389. [CrossRef]

- Sarabia-Jácome, D.; Palau, C.E.; Esteve, M.; Boronat, F. Seaport Data Space for Improving Logistic Maritime Operations. IEEE Access. 2020, 8, 4372–4382. [CrossRef]

- Marine Traffic – AIS Data. Available online: https://www.marinetraffic.com/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- ECDIS. Maritime Navigation Specialists. Available online: https://ecdis.org/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- MDA. Situational Indication Linkages. Available online: https://www.msil.go.jp/msil/htm/main.html?Lang=1 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Lam, S.Y.W.; Yip, T.L. The Role of Geomatics Engineering in Establishing the Marine Information System for Maritime Management. Marit. Policy Manag. 2008, 35(1), 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Maudire, G.; Nys, C.; Sudre, J.; Harscoat, V.; Dibarboure, G.; Huynh, F. Streamlining Data and Service Centers for Easier Access to Data and Analytical Services: The Strategy of ODATIS as the Gateway to French Marine Data. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020. 7:548126,1-10. [CrossRef]

- Emani, C.K.; Cullot, N.; Nicolle, C. Big Data Understandable: A Survey. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2015, 17, 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Tavra, M.; Jajac, N.; Cetl, V. Marine Spatial Data Infrastructure Development Framework: Croatia Case Study. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 117. [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, C.; Ioanid, A.; Andrei, N. Use of the Geospatial Technologies and Its Implications in the Maritime Transport and Logistics. Int. Marit. Transp. Logist. J. 2023, 12, 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Santana, J.M.; Ortega, S.; Trujillo, A.; Suárez, J.P.; Domínguez, C.; Santana, J.; Sánchez, A. SmartPort: A Platform for Sensor Data Monitoring in a Seaport Based on FIWARE. Sensors. 2016, 16, 417. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Idol, T. Development of Spatial Data Infrastructures for Marine Data Management; OGC-IHO Marine SDI Concept Development Study (CDS). Available online: https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/handle/11329/1551 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Lu, B.; Xu, X. Digital Transformation and Port Operations: Optimal Investment Under Incomplete Information. Transp. Policy. 2024, 151, 134–146. [CrossRef]

- Lytra, I.; Vidal, M.-E.; Orlandi, F.; Attard, J. A Big Data Architecture for Managing Oceans of Data and Maritime Applications. Proc. ICE/ITMC 2017. 2017, 1216–1226. [CrossRef]

- Erasmus University. SmartPort. Available online: http://www.erim.eur.nl/research/centres/smart-port/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Hamburg Port Authority. SmartPORT Logistics. Available online: http://www.hamburg-port-authority.de/en/smartport/logistics/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Nexus Lab. Nexus Agenda Project. Available online: https://nexuslab.pt/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Tanger Med Port Authority. Vessel Reception Services. Available online: https://www.tangermedport.com/en/service/vessel-reception/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Paraskevas, A.; Madas, M.; Zeimpekis, V.; Fouskas, K. Smart Ports in Industry 4.0: A Systematic Literature Review. Logistics 2024, 8, 28. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Feng, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, L.; Ma, F.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y. Multi-Terminal Berth and Quay Crane Joint Scheduling in Container Ports Considering Carbon Cost. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 5018. [CrossRef]

- Farah, M.B.; Ahmed, Y.; Mahmoud, H.; Shah, S.A.; Al-Kadri, M.O.; Taramonli, S.; Bellekens, X.; Abozariba, R.; Idrissi, M.; Aneiba, A. A survey on blockchain technology in the maritime industry: Challenges and future perspectives. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 157, 618–637. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, K.; Rawat, D.B.; Wu, J.; Imran, M.A. Guest Editorial: Security, Reliability, and Safety in IoT-Enabled Maritime Transportation Systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 2275–2281. [CrossRef]

- Zeneli, M.; Marinova, G. Navigating the Future: Digital Twin in Maritime Industry. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Broadband Communications for Next Generation Networks and Multimedia Applications (CoBCom). 2024,1–6. [CrossRef]

- Kavallieratos, G.; Diamantopoulou, V.; Katsikas, S.K. Shipping 4.0: Security Requirements for the Cyber-Enabled Ship. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16(10), 6617–6625. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, M.; Zun, Z.; Qian, X. Multi-Aspect Applications and Development Challenges of Digital Twin-Driven Management in Global Smart Ports. Case Stud. Transp. Policy. 2021, 9, 1298–1312. [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, D.; Weng, M.L. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009 ; pp. 671–689. Available online:https://books.google.com.br/books?hl=ptPT&lr=&id=vVs2EoDjm78C&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=In+The+Sage+Handbook+of+Organizational+Research+Methods&ots=8S17tOPDUJ&sig=vKV7t8ZfSWr3FlEXcUbnMVJLphU (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications. 2021, 9, 12. [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-Tool for Comprehensive Science Mapping Analysis. J. Informetrics. 2017, 11(4), 959–975. [CrossRef]

- Ampah, J.D.; Yusuf, A.A.; Afrane, S.; Jin, C.; Liu, H. Reviewing Two Decades of Cleaner Alternative Marine Fuels: Towards IMO's Decarbonization of the Maritime Transport Sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128871. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Salcedo, M.; Martínez, M.Á.; Moral-Muñoz, J.A.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Cobo, M.J. Some Bibliometric Procedures for Analyzing and Evaluating Research Fields. Appl. Intell. 2018, 48, 1275–1287. [CrossRef]

- Moshiul, A.M.; Mohammad, R.; Hira, F.A.; Maarop, N. Alternative Marine Fuel Research Advances and Future Trends: A Bibliometric Knowledge Mapping Approach. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 4947. [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. Conducting Systematic Literature Reviews and Bibliometric Analyses. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45(2), 175–194. [CrossRef]

- Web of Science – WoS. WoS Search. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/ (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Scopus. Scopus Search. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/ (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Chadegani, A.A.; Salehi, H.; Md Yunus, M.M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ale Ebrahim, N. A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 18–26. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n5p18.

- Mingers, J.; Leydesdorff, L. A Review of Theory and Practice in Scientometrics. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 246, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green Supply Chain Management: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 101–114. [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222.

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Analysis. Scientometrics. 2016, 106, 213–228. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.S.d.; Parise, C.K.; Duarte, L.; Teodoro, A.C. Bibliometric Analysis of Global Research on Port Infrastructure Vulnerability to Climate Change (2012–2023): Key Indices, Influential Contributions, and Future Directions. Sustainability. 2024, 16, 8622. [CrossRef]

- Barianaki, E.; Kyvelou, S.S.; Ierapetritis, D.G. How to Incorporate Cultural Values and Heritage in Maritime Spatial Planning: A Systematic Review. Heritage. 2024, 7, 380–411. [CrossRef]

- Jović, M.; Tijan, E.; Brčić, D.; Pucihar, A. Digitalization in Maritime Transport and Seaports: Bibliometric, Content and Thematic Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 486. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Alarcón, C.H.; Bodero-Poveda, E.; Villa-Yánez, H.M.; Buñay-Guisñan, P.A. Blockchain and Its Application in the Peer Review of Scientific Works: A Systematic Review. Publications. 2024, 12, 40. [CrossRef]

- Bibliometrix. Bibliometrix Home. Available online: https://www.bibliometrix.org/home/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Moral-Muñoz, J.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Santisteban-Espejo, A.; Cobo, M. Software Tools for Conducting Bibliometric Analysis in Science: An Up-to-Date Review. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290103. [CrossRef]

- McLaren, C.D.; Bruner, M.W. Citation Network Analysis. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 15, 179–198. [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Kargina, M. A User-Friendly Method to Merge Scopus and Web of Science Data During Bibliometric Analysis. J. Mark. Anal. 2022, 10, 82–88. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Rani, S.; Awadh, M.A. Exploring the Application Sphere of the Internet of Things in Industry 4.0: A Review, Bibliometric and Content Analysis. Sensors. 2022, 22, 4276. [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Chandra, B. Two Decades of M-Commerce Consumer Research: A Bibliometric Analysis Using R Biblioshiny. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 11835. [CrossRef]

- Sheela, S.; Alsmady, A.A.; Tanaraj, K.; Izani, I. Navigating the Future: Blockchain’s Impact on Accounting and Auditing Practices. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 16887. [CrossRef]

- David, L.O.; Nwulu, N.; Aigbavboa, C.; Adepoju, O. Towards Global Water Security: The Role of Cleaner Production. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 10, 100695. [CrossRef]

- Alka, T.A.; Raman, R.; Suresh, M. Research Trends in Innovation Ecosystem and Circular Economy. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 323. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.d.S.T.; de Oliveira, V.M.; Correia, S.É.N. Scientific Mapping in Scopus with Biblioshiny: A Bibliometric Analysis of Organizational Tensions. Context. Rev. Contemp. Econ. Gestão. 2022, 20, 54–71.

- Bibliometrix. Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: https://www.bibliometrix.org/home/index.php/faq# (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). PRISMA Statement. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/ (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Yusop, S.R.M.; Rasul, M.S.; Mohamad Yasin, R.; Hashim, H.U.; Jalaludin, N.A. An Assessment Approaches and Learning Outcomes in Technical and Vocational Education: A Systematic Review Using PRISMA. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 5225. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. The BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

- Callon, M.; Courtial, J.P.; Laville, F. Co-Word Analysis as a Tool for Describing the Network of Interactions Between Basic and Technological Research: The Case of Polymer Chemistry. Scientometrics. 1991, 22, 155–205. [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. An Approach for Detecting, Quantifying, and Visualizing the Evolution of a Research Field: A Practical Application to the Fuzzy Sets Theory Field. J. Informetr. 2011, 5, 146–166. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Ben Said, F.; Alkathiri, N.A.; et al. A Scientometric Analysis of Entrepreneurial and the Digital Economy Scholarship: State of the Art and an Agenda for Future Research. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 70. [CrossRef]

- Szomszor, M.; Adams, J.; Fry, R.; Gebert, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Potter, R.W.K.; Rogers, G. Interpreting Bibliometric Data. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2021, 5, 628703. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, H.M.; Cooper, J.A.G. Coastal and Marine Management–Navigating Islands of Data. Mar. Policy. 2024, 169, 106279. [CrossRef]

- Contarinis, S.; Nakos, B.; Pallikaris, A. Introducing Smart Marine Ecosystem-Based Planning (SMEP)—How SMEP Can Drive Marine Spatial Planning Strategy and Its Implementation in Greece. Geomatics. 2022, 2, 197–220. [CrossRef]

- Vaitis, M.; Kopsachilis, V.; Tataris, G.; Michalakis, V.I.; Pavlogeorgatos, G. The Development of a Spatial Data Infrastructure to Support Marine Spatial Planning in Greece. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 218, 106025. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. INSPIRE Knowledge Base. Available online: https://knowledge-base.inspire.ec.europa.eu/overview_en (accessed on 26 December 2024).

- Abramic, A.; Bigagli, E.; Barale, V.; Assouline, M.; Lorenzo-Alonso, A.; Norton, C. Maritime Spatial Planning Supported by Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe (INSPIRE). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 152, 23–36. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, H.M.; Cooper, J.A.G. On the Centrality of Tenure in Spatial Data Systems for Coastal/Marine Management: International Exemplars versus Emerging Practice in Ireland. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 257, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Taramelli, A.; Valentini, E.; Sterlacchini, S. A GIS-Based Approach for Hurricane Hazard and Vulnerability Assessment in the Cayman Islands. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 108, 116–130. [CrossRef]

- Giorgetti, A.; Partescano, E.; Barth, A.; Buga, L.; Gatti, J.; Giorgi, G.; Wenzer, M. EMODnet Chemistry Spatial Data Infrastructure for Marine Observations and Related Information. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 166, 9–17. [CrossRef]

- Mamode, S.A.; Runghen, H.; Munnaroo, S.; Bissessur, D.; Coopen, P.; von Arnim, Y.; Badal, R. Mapping of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Geophysical Survey and Data Management of HMS Sirius Shipwreck. In OCEANS 2022-Chennai; IEEE. 2022; 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Kazimierski, W. On Using Spatial Data Infrastructure Concept for Exchange of Navigational Information on Ships. In Proceedings of the 2017 Baltic Geodetic Congress (Geomatics); IEEE. 2017; pp. 267–272. [CrossRef]

- Ogryzek, M.; Tarantino, E.; Rząsa, K. Infrastructure of the Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE) Based on Examples of Italy and Poland. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 755. [CrossRef]

- UN-GGIM. Standards Guide. Available online: https://standards.unggim.ogc.org/index.php (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Open Geospatial Consortium. Home. Available online: https://www.ogc.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Agrawal, S.; Gupta, R.D. Web GIS and Its Architecture: A Review. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 518. [CrossRef]

- Patera, A.; Pataki, Z.; Kitsiou, D. Development of a WebGIS Application to Assess Conflicting Activities in the Framework of Marine Spatial Planning. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 389. [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, Y.; Dalaklis, D.; Kitada, M.; Christodoulou, A. Shipping in the Era of Digitalization: Mapping the Future Strategic Plans of Major Maritime Commercial Actors. Digit. Bus. 2022, 2, 100022. [CrossRef]

- Fast, V.; Hossain, F. An Alternative to Desktop GIS? Evaluating the Cartographic and Analytical Capabilities of WebGIS Platforms for Teaching. Cartogr. J. 2020, 57, 175–186. [CrossRef]

- Thanopoulou, H.; Patera, A.; Moresis, O.; Georgoulis, G.; Lioumi, V.; Kanavos, A.; Papadimitriou, O.; Zervakis, V.; Dagkinis, I. Supporting Informed Public Reactions to Shipping Incidents with Oil Spill Potential: An Innovative Electronic Platform. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 15035. [CrossRef]

- Dawidowicz, A.; Kulawiak, M. The Potential of Web-GIS and Geovisual Analytics in the Context of Marine Cadastre. Surv. Rev. 2017, 50, 501–512. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Santana, J.M.; Ortega, S.; Trujillo, A.; Suárez, J.P.; Santana, J.A.; Domínguez, C. Web-Based GIS Through a Big Data Open-Source Computer Architecture for Real-Time Monitoring Sensors of a Seaport. In The Rise of Big Spatial Data; Springer. 2017; pp. 41–53. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Suárez, J.P.; Trujillo, A.; Domínguez, C.; Santana, J.M. 3D-Monitoring Big Geo Data on a Seaport Infrastructure Based on FIWARE. J. Geogr. Syst. 2018, 20, 139–157. [CrossRef]

- Makris, C.; Papadimitriou, A.; Baltikas, V.; Spiliopoulos, G.; Kontos, Y.; Metallinos, A.; Androulidakis, Y.; Chondros, M.; Klonaris, G.; Malliouri, D.; et al. Validation and Application of the Accu-Waves Operational Platform for Wave Forecasts at Ports. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 220. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Park, S. E-Navigation-Supporting Data Management System for Variant S-100-Based Data. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2015, 74, 6573–6588. [CrossRef]

- Johansen, T.; Blindheim, S.; Torben, T.R.; Utne, I.B.; Johansen, T.A.; Sørensen, A.J. Development and Testing of a Risk-Based Control System for Autonomous Ships. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 234, 109195. [CrossRef]

- Ban, H.; Kim, H.J. Analysis and Visualization of Vessels’ Relative Motion (REMO). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 115. [CrossRef]

- Tsaimou, C.N.; Sartampakos, P.; Tsoukala, V.K. UAV-Driven Approach for Assisting Structural Health Monitoring of Port Infrastructure. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023. 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mou, J.; Chen, P.; Chen, L.; van Gelder, P.H.A.J.M. Real-Time Collision Risk-Based Safety Management for Vessel Traffic in Busy Ports and Waterways. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 234, 106471. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Tang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L. A Big Data Analytics Method for the Evaluation of Maritime Traffic Safety Using Automatic Identification System Data. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107077. [CrossRef]

- Thill, J.-C.; Venkitasubramanian, K. Multi-Layered Hinterland Classification of Indian Ports of Containerized Cargoes Using GIS Visualization and Decision Tree Analysis. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2014, 17, 265–291. [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-C.; Wang, C.-N.; Hsu, H.-P.; Ding, J.-F.; Tseng, W.-J.; Yeh, C.-Y. Integrating AIS, GIS, and E-Chart to Analyze the Shipping Traffic and Marine Accidents at the Kaohsiung Port. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1543. [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Che, T.; Li, X.; Zhu, X. A Ship Navigation Information Service System for the Arctic Northeast Passage Using 3D GIS Based on Big Earth Data. Big Earth Data. 2022, 6, 453–479. [CrossRef]

- Karountzos, O.; Kagkelis, G.; Kepaptsoglou, K. A Decision Support GIS Framework for Establishing Zero-Emission Maritime Networks: The Case of the Greek Coastal Shipping Network. J. Geovisualization Spat. Anal. 2023, 7, 16. [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Cumo, F.; Nezhad, M.M.; Orsini, G.; Piras, G. Renewable Energy System Controlled by Open-Source Tools and Digital Twin Model: Zero Energy Port Area in Italy. Energies. 2022, 15, 1817. [CrossRef]

- Edih, U.O.; Faghawari, N.; Agboro, D.O. Port Operation’s Efficiency and Revenue Generation in Global Maritime Trade: Implications for National Growth and Development in Nigeria. J. Money Bus. 2023, 3, 184–196. [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi, S.; Al-Ahmadi, K.; Almeshari, M. Spatial Variation in the Association between NO₂ Concentrations and Shipping Emissions in the Red Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 676, 131–143. [CrossRef]

- El-Magd, I.A.; Mohamed, Z.; Elham, M.A.; Abdulaziz, M.A. An Open-Source Approach for Near-Real-Time Mapping of Oil Spills along the Mediterranean Coast of Egypt. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2733. [CrossRef]

- Hadipour, M.; Morteza, N.; Mokhtar, M.; Ern, L.K. Geospatial Analyzing of Straits Shipping Paths for Integration of Air Quality and Marine Wildlife Conservation. J. Wildl. Biodivers. 2021, 5, 63–80. [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.L.; Chung, W.C.; Chen, C.W. AIS-Based Scenario Simulation for the Control and Improvement of Ship Emissions in Ports. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 129. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. GIS-Based Analysis on the Spatial Patterns of Global Maritime Accidents. Ocean Eng. 2022, 245, 110569. [CrossRef]

- Guiziou, F.H. Assessing the Effects of a War on a Container Terminal: Lessons from Al Hudaydah, Yemen. TransNav. 2024, 18, 195–204. [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.A. Seeing Like an Algorithm: The Limits of Using Remote Sensing to Link Vessel Movements with Worker Abuse at Sea. Marit. Stud. 2024, 23, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kalyvas, C.; Kokkos, A.; Tzouramanis, T. A Survey of Official Online Sources of High-Quality Free-of-Charge Geospatial Data for Maritime Geographic Information Systems Applications. Inf. Syst. 2017, 65, 36–51. [CrossRef]

- Salminen, E.A.; Murguzur, F.J.A.; Ollus, V.M.S.; Engen, S.; Hausner, V.H. Using Public Participation GIS (PPGIS) to Relate Local Concerns over Growth in Tourism and Aquaculture to Integrated Coastal Zone Management in the Tromsø Region, Norway. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 261, 107510. [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Strickland-Munro, J.; Kobryn, H.; Moore, S.A. Stakeholder Analysis for Marine Conservation Planning Using Public Participation GIS. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 67, 77–93. [CrossRef]

- Morse, W.C.; Cox, C.; Anderson, C.J. Using Public Participation Geographic Information Systems (PPGIS) to Identify Valued Landscapes Vulnerable to Sea Level Rise. Sustainability. 2020, 12, 6711. [CrossRef]

- Ettorre, B.; Daldanise, G.; Giovene di Girasole, E.; Clemente, M. Co-Planning Port–City 2030: The InterACT Approach as a Booster for Port–City Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2023, 15, 15641. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Yao, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Bai, J. GIS-Based Simulation Methodology for Evaluating Ship Encounters Probability to Improve Maritime Traffic Safety. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 323–337. [CrossRef]

- Min, H. Developing a Smart Port Architecture and Essential Elements in the Era of Industry 4.0. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2022, 24, 189–207. [CrossRef]

- Alcatel-Lucent Enterprise. Smart Ports and Logistics Solutions. Alcatel-Lucent Enterprise. Available online: https://www.al-enterprise.com/en/industries/transportation/ports (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- McKinsey & Company, 2017. The case for digital reinvention. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/the-case-for-digital-reinvention (accessed 12 January 2024).

- Grzelakowski, A.S. The COVID 19 Pandemic–Challenges for Maritime Transport and Global Logistics Supply Chains. TransNav. 2022, 16, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, Z.; Efremochkina, M.; Liu, X.; Lin, C. Study on City Digital Twin Technologies for Sustainable Smart City Design: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Geographic Information System and Building Information Modeling Integration. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104009. [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, J.; Heilig, L.; Voß, S. Digital Twins in the Context of Seaports and Terminal Facilities. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2024, 36, 821–917. [CrossRef]

- Freire, W.P.; Melo, W.S., Jr.; do Nascimento, V.D.; Nascimento, P.R.M.; de Sá, A.O. Towards a Secure and Scalable Maritime Monitoring System Using Blockchain and Low-Cost IoT Technology. Sensors 2022, 22, 4895. [CrossRef]

- Monzon Baeza, V.; Ortiz, F.; Herrero Garcia, S.; Lagunas, E. Comunicações aprimoradas em sistemas de IoT baseados em satélite para dar suporte a serviços de transporte marítimo. Sensors. 2022, 22, 6450. [CrossRef]

- Argyriou, I.; Tsoutsos, T. Avaliação de entidades críticas: gerenciamento de risco para dispositivos de IoT em portos. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1593. [CrossRef]

- Durlik, I.; Miller, T.; Cembrowska-Lech, D.; Krzemińska, A.; Złoczowska, E.; Nowak, A. Navigating the Sea of Data: A Comprehensive Review on Data Analysis in Maritime IoT Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9742. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, R.; Ungo, R.; Smith, K.; Haghnegahdar, L.; Singh, B.; Phuong, T. Applications of AI/ML in Maritime Cyber Supply Chains. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 3247–3257. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. Spatial Risk Assessment of Maritime Transportation in Offshore Waters of China Using Machine Learning and Geospatial Big Data. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 247, 106934. [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, D.; Alesheikh, A.A.; Sharif, M. Vessel Trajectory Prediction Using Historical Automatic Identification System Data. J. Navig. 2020, 1, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Last, P.; Bahlke, C.; Hering-Bertram, M.; Linsen, L. Comprehensive Analysis of Automatic Identification System (AIS) Data in Regard to Vessel Movement Prediction. J. Navig. 2014, 67, 791–809. [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.-L.; Lee, M.-C.; Nieh, C.-Y.; Huang, J.-C. Ship Classification Based on AIS Data and Machine Learning Methods. Electronics. 2024, 13, 98. [CrossRef]

- Le, L.T. Discovering Supply Chain Operation Towards Sustainability Using Machine Learning and DES Techniques: A Case Study in Vietnam Seafood. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2024, 9, 243–262. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Li, W.; Xu, Y. Port Planning and Sustainable Development Based on Prediction Modelling of Port Throughput: A Case Study of the Deep-Water Dongjiakou Port. Sustainability. 2022, 14, 4276. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Bai, X.; Yang, D.; Yuen, K.F.; Wu, J. A Deep Learning Approach for Port Congestion Estimation and Prediction. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 50, 835–860. [CrossRef]

- Thennakoon, K.; Bandaranayake, N.; Kiridena, S.; Kulatunga, A.K. Quantification of Landside Congestion in Ports: An Analysis Based on GPS Data. J. South Asian Logist. Transp. 2024, 4, 1. [CrossRef]

- Irannezhad, E.; Prato, C.G.; Hickman, M. An Intelligent Decision Support System Prototype for Hinterland Port Logistics. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 130, 113227. [CrossRef]

- Novaes Mathias, T.; Sugimura, Y.; Kawasaki, T.; Akakura, Y. Topological Resilience of Shipping Alliances in Maritime Transportation Networks. Logistics. 2025, 9, 6. [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, M.; Shibasaki, R. Can AIS Data Improve the Short-Term Forecast of Weekly Dry Bulk Cargo Port Throughput? A Machine-Learning Approach. Marit. Policy Manag. 2023, 51, 1788–1804. [CrossRef]

- Reggiannini, M.; Righi, M.; Tampucci, M.; Lo Duca, A.; Bacciu, C.; Bedini, L.; D’Errico, A.; Di Paola, C.; Marchetti, A.; Martinelli, M.; et al. Remote Sensing for Maritime Prompt Monitoring. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 202. [CrossRef]

- Reggiannini, M.; Salerno, E.; Bacciu, C.; D’Errico, A.; Lo Duca, A.; Marchetti, A.; Martinelli, M.; Mercurio, C.; Mistretta, A.; Righi, M.; et al. Remote Sensing for Maritime Traffic Understanding. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 557. [CrossRef]

- a_Rawson, A.; Brito, M. Developing Contextually Aware Ship Domains Using Machine Learning. J. Navig. 2021, 74, 515–532. [CrossRef]

- b_Rawson, A.; Brito, M.; Sabeur, Z. Spatial Modeling of Maritime Risk Using Machine Learning. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 2291–2311. [CrossRef]

- c_Rawson, A.; Sabeur, Z.; Brito, M. Intelligent Geospatial Maritime Risk Analytics Using the Discrete Global Grid System. Big Earth Data. 2021, 6, 294–322. [CrossRef]

- d_Rawson, A.; Brito, M.; Sabeur, Z.; Tran-Thanh, L. A Machine Learning Approach for Monitoring Ship Safety in Extreme Weather Events. Safety Sci. 2021, 141, 105336. [CrossRef]

- Alshareef, M.H.; Aljahdali, B.M.; Alghanmi, A.F.; Sulaimani, H.T. Spatial Analysis and Risk Evaluation for Port Crisis Management Using Integrated Soft Computing and GIS-Based Models: A Case Study of Jazan Port, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability. 2024, 16, 5131. [CrossRef]

- Temitope Yekeen, S.; Balogun, A.-L. Advances in Remote Sensing Technology, Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Marine Oil Spill Detection, Prediction and Vulnerability Assessment. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3416. [CrossRef]

- Najafizadegan, S.; Danesh-Yazdi, M. Variable-Complexity Machine Learning Models for Large-Scale Oil Spill Detection: The Case of Persian Gulf. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 195, 115459. [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, L.C.; Veloso, G.V.; Ferreira, I.O. Comparison of Deterministic, Probabilistic and Machine Learning-Based Methods for Bathymetric Surface Modeling. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Leveraging digital tools in the age of supply chain disruption. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/supply-chain-disruption-digital-winners-losers/ (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Zhang, C.; Zhao, T.; Li, W. Geospatial Data Interoperability, Geography Markup Language (GML), Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG), and Geospatial Web Services. In Geospatial Semantic Web; Springer, Cham. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Durlik, I.; Miller, T.; Cembrowska-Lech, D.; Krzemińska, A.; Złoczowska, E.; Nowak, A. Navigating the Sea of Data: A Comprehensive Review on Data Analysis in Maritime IoT Applications. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9742. [CrossRef]

- Gourmelon, F.; Le Guyader, D.; Fontenelle, G. A Dynamic GIS as an Efficient Tool for Integrated Coastal Zone Management. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2014, 3, 391–407. [CrossRef]

- Hatlas-Sowinska, P.; Wielgosz, M. Ontology-Based Approach in Solving Collision Situations at Sea. Ocean Eng. 2022, 260, 111941. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wen, K.; Zhao, J.; Bian, Z.; Lu, T.; Ko Ko Latt, M.; Wang, C. Ontology-Based Method for Identifying Abnormal Ship Behavior: A Navigation Rule Perspective. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 881. [CrossRef]

- Pagano, P.; Antonelli, S.; Tardo, A. C-Ports: A Proposal for a Comprehensive Standardization and Implementation Plan of Digital Services Offered by the “Port of the Future.” Comput. Ind. 2022, 134, 103556. [CrossRef]

- Andrei, N.; Scarlat, C.; Ioanid, A. Transforming E-Commerce Logistics: Sustainable Practices through Autonomous Maritime and Last-Mile Transportation Solutions. Logistics. 2024, 8, 71. [CrossRef]

| Screening | WOS | Scopus |

| Final Boolean Equation | TS=((("spatial data infrastructure" OR "marine sdi" OR "geogra* information system" OR "gis*" OR "geospatial data integration") AND ("seaport" OR "port" OR (("smart" OR "green" OR "intelligent" OR "automated ") AND "port*") OR "maritime*" OR "logistic*" OR "terminal*" OR "ship*" OR "vessel*" OR "berth*" OR "container*") AND ("interoperability" OR "visualiz*" OR "open data" OR "digital*" OR ("web" AND ("map" OR "service" OR "gis" OR "based gis")) AND ( "map*" OR "dataset" OR "tool" OR "ais" OR "iot")))) | TITLE-ABS-KEY (("spatial data infrastructure" OR "marine sdi" OR "geogra* information system" OR "gis*" OR "geospatial data integration") AND ("seaport" OR "port" OR (("smart" OR "green" OR "intelligent" OR "automated ") AND "port*") OR "maritime*" OR "logistic*" OR "terminal*" OR "ship*" OR "vessel*" OR "berth*" OR "container*") AND ("interoperability" OR "visualiz*" OR "stakeholder*" OR "open data" OR "digital*" OR ("web" AND ("map" OR "service" OR "gis" OR "based gis")) AND ( "map*" OR "dataset" OR "tool" OR "ais" OR "iot"))) AND PUBYEAR AFT 2014 |

| Languages | English | English |

| Document Types | Articles and Review Article | Articles and Review Article |

| Research Areas | Environmental Sciences Ecology, Engineering, Water Resources, Remote Sensing, Computer Science, Imaging Science Photographic Technology, Science Technology Other Topics, Meteorology Atmospheric Sciences, Oceanography, Geography, Transportation, Marine Freshwater Biology, Biodiversity Conservation, Energy Fuels, Operations Research Management Science. | Environmental Science, Earth and Planetary Sciences, Engineering, Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Computer Science, Energy, Business, Management and Accounting, Decision Sciences e Multidisciplinary. |

| Type | Description | Results |

| Main information about data | ||

| Period | Years of publication | 2014:2024 |

| Sources (Journals, Books, etc) | Frequency distribution of sources as journals | 279 |

| Documents | Total number of documents | 530 |

| Annual Growth Rate % | Average number of annual growth | 8.59 |

| Document Average Age | Average age of the document | 5.14 |

| Average citations per doc | Average total number of citations per document | 28.65 |

| References | Total number of references or citations | 0 |

| Document contents | ||

| Keywords Plus (ID) | Total number of phrases that frequently appear in the title of an article’s references | 2429 |

| Author's Keywords (DE) | Total number of keywords | 2194 |

| Authors | ||

| Authors | Total number of authors | 2205 |

| Authors of single-authored docs | Number of single authors per article | 26 |

| Authors collaboration | ||

| Single-authored docs | Number of documents written by a single author | 26 |

| Co-Authors per Doc | Average number of co-authors in each document | 4.72 |

| International co-authorships % | Average number of international co-authorships | 24.72 |

| Document types | ||

| Article | Number of articles | 514 |

| Article; early access | Number of early access articles | 6 |

| Review | Number of review articles | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).