1. Introduction

Magnesium alloys possess characteristics such as lightweight, high strength, excellent electrical conductivity, and thermal conductivity, making them highly promising materials in aerospace, defense, and other high-end applications[

1,

2,

3]. However, the HCP crystal structure of magnesium alloys results in strong anisotropy and poor cold workability, which significantly limits their practical applications[

4,

5]. In 2016, Ogawa et al.[

6] discovered that β-type Mg-20.5 at.% Sc alloy exhibits a shape memory effect in space environments, with its parent phase being a BCC structure. The bcc structure features 12 independent slip systems, endowing the alloy with excellent plasticity[

7]. Studies have shown that the microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-Sc alloys can be effectively tuned through heat treatment[

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Ando et al.[

8,

9] reported that β-Mg-16.8 at.% Sc alloy and dual-phase Mg-20.5 at.% Sc alloy exhibited pronounced age hardening due to the formation of needle-like α phases in the β phase during low-temperature aging. Ogawa et al.[

10] further demonstrated that heat treatment temperature significantly affects the phase fraction and grain size in Mg-20 at.% Sc alloy, achieving superior mechanical properties in dual-phase Mg-Sc alloys. Therefore, investigating the microstructural evolution of dual-phase Mg-Sc alloys during heat treatment and its influence on mechanical properties is of great significance for optimizing the heat treatment process of Mg-Sc alloys.

In recent years, the rational design and introduction of heterogeneous structures in materials have become an effective strategy to overcome the strength-ductility trade-off in metallic materials[

13,

14,

15]. In heterogeneous structured materials, coarse-grained/soft phases and fine-grained/hard phases form distinct "soft" and "hard" regions, respectively. During plastic deformation, these heterogeneous regions induce non-uniform deformation, resulting in the heterogeneous deformation-induced (HDI) strengthening effect while maintaining good ductility. For example, Wang et al.[

16] obtained a heterogeneous structure with alternating coarse-grained (CG) and fine-grained (FG) layers in a Mg-9Al-1Zn-1Sn alloy through simple rolling and precisely controlled annealing processes, achieving excellent mechanical properties with a yield strength of 251 MPa, ultimate tensile strength of 393 MPa, and elongation of 23 %. Regarding Mg-Sc alloys, their inherent dual-phase components provide a natural advantage for optimizing mechanical properties through heterogeneous structure design. Therefore, regulating the microstructure of Mg-Sc alloys through heat treatment to achieve a favorable strength-ductility synergy is of paramount importance for developing high-performance Mg-Sc alloys.

2. Experimental Methods

The Mg-Sc alloy with a nominal composition of Mg-19.2 at.% Sc was fabricated from 99.99 % pure Mg and Sc in a vacuum induction furnace under an argon atmosphere. To achieve a homogeneous composition, the ingot was remelted four times and then slowly cooled within the furnace. The resulting ingot, with a thickness of 15 mm, was hot-rolled at 650 °C to reduce its thickness to 3 mm. Subsequently, repeated cycles of cold rolling and annealing at 600 °C for 15 minutes were applied until the sheet thickness was further reduced to 2 mm, with both hot and cold rolling conducted along the same rolling direction. The thin sheets were then cut into pieces and annealed at 500 °C, 550 °C, and 600 °C for 30 minutes before being water quenched, alloys with different proportions of hcp/bcc dual phases. The crystal structure was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using Cu K-α radiation on a Regaku Ultima, with a scan speed of 2 º/min over a 20º-80º range. In addition, the microstructure was examined by electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) using a field emission scanning electron microscope. Tensile tests were performed at room temperature with an initial strain rate of 10⁻³ s⁻¹, using specimens with a gauge length of 10 mm and a width of 3 mm.

3. Results

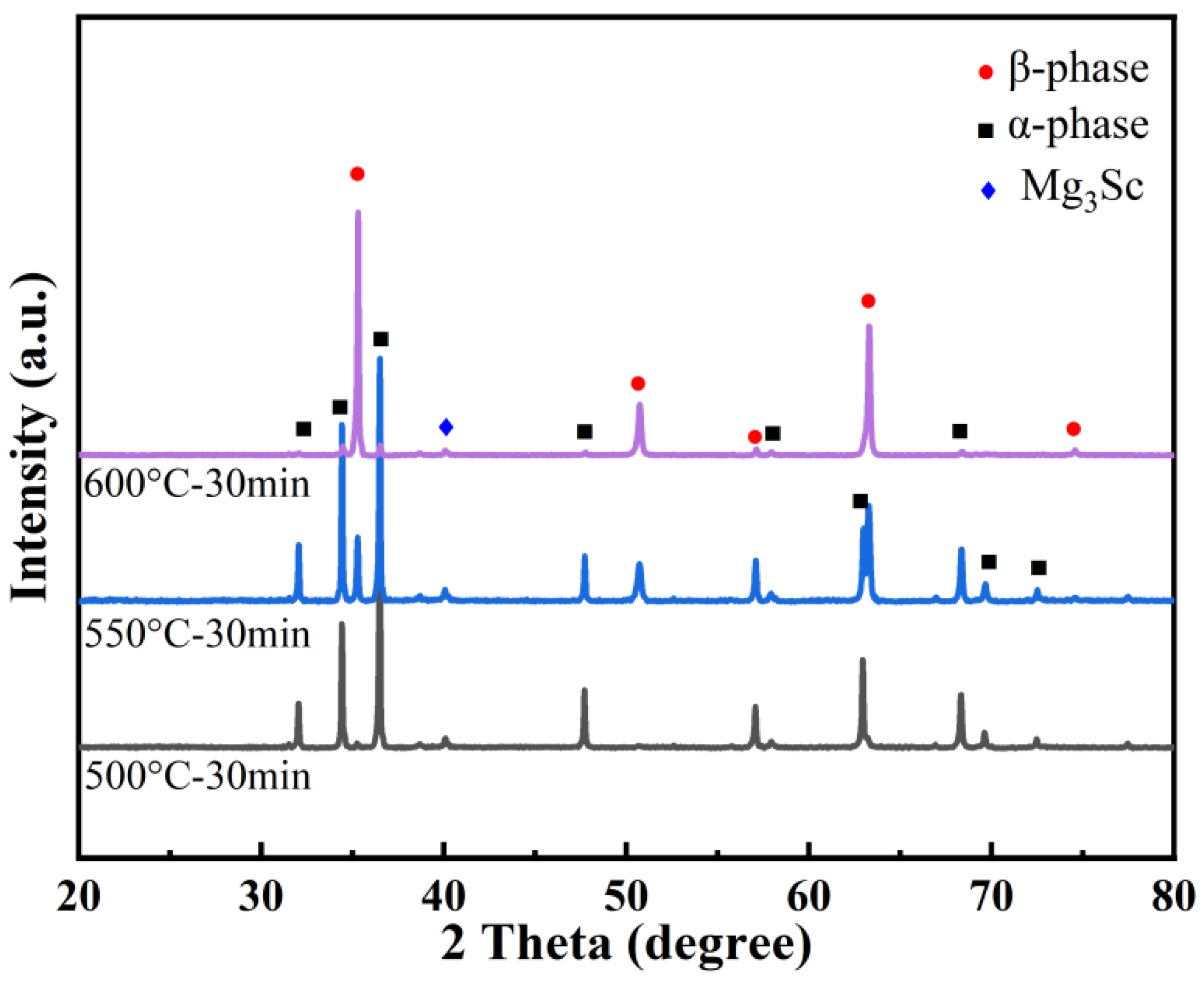

As shown in

Figure 1, for the sample annealed at 550°C, the diffraction peaks are predominantly from the α phase, accompanied by several diffraction peaks of the β phase. With the increase in annealing temperature, the proportion of the β phase significantly increases based on the relative intensity of the diffraction peaks. When the sample annealed at 600°C, the diffraction peak intensity of the β phase increased dramatically, indicating a microstructure predominantly composed of the β phase. X-ray diffraction analysis indicates that elevating the annealing temperature effectively accelerates the transformation of the α phase into the β phase, as evidenced by the enhanced diffraction intensity of the β phase.

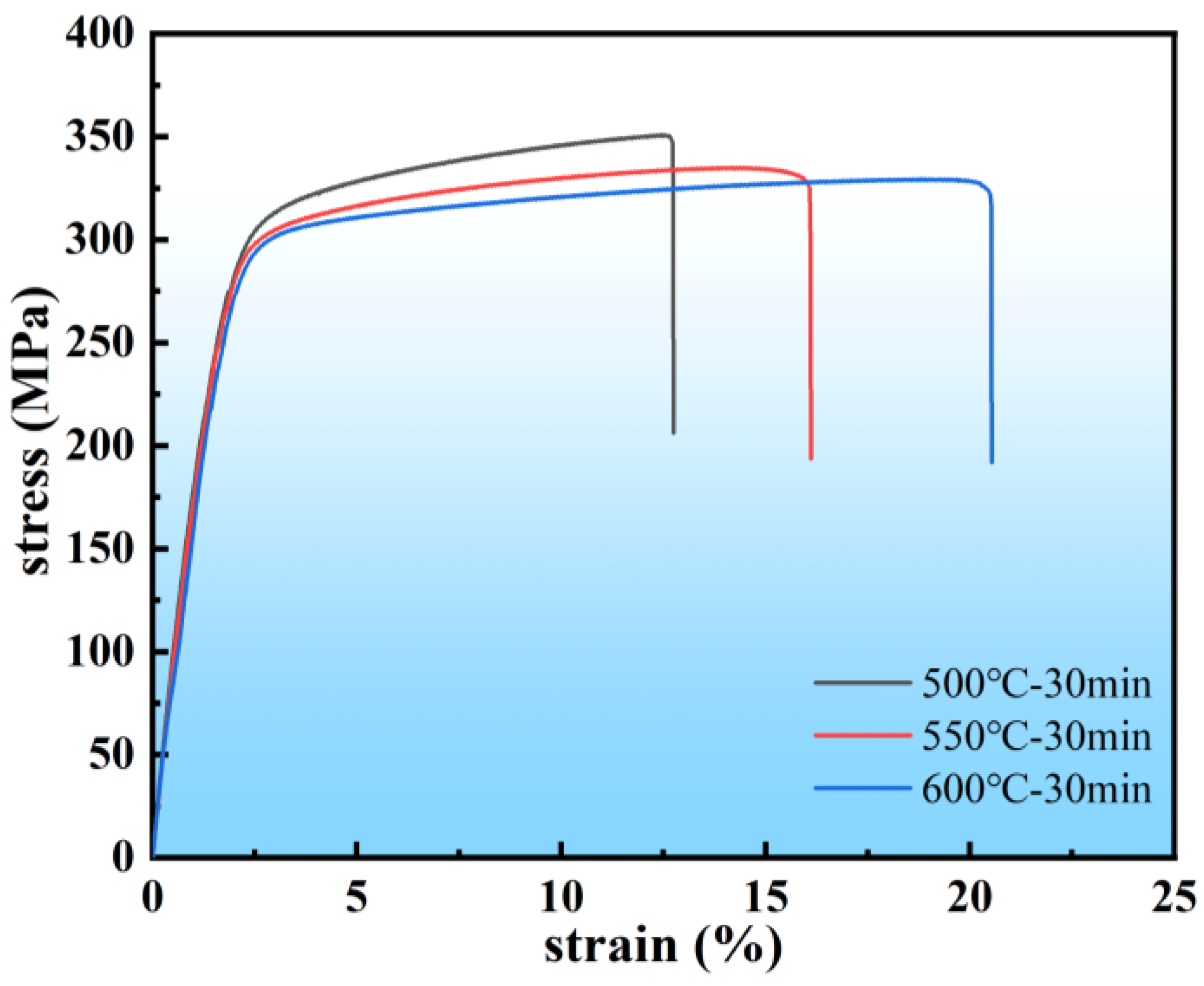

Figure 2 displays the room temperature tensile engineering stress-strain curves, and comprehensive summaries of the detailed mechanical property values is presented in

Table 1. The Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy annealed at 600 °C for 30 minutes exhibits a high ultimate tensile strength (329 MPa) and an excellent fracture elongation (20.5 %). Interestingly, the elongation of the alloy gradually increases with the rising annealing temperature, while the yield strength remains nearly unchanged, which contradicts the conventional strength-ductility trade-off theory of alloys. Therefore, the underlying microstructural mechanisms responsible for the improved ductility without yield strength degradation in the 600 °C annealed sample require further investigation.

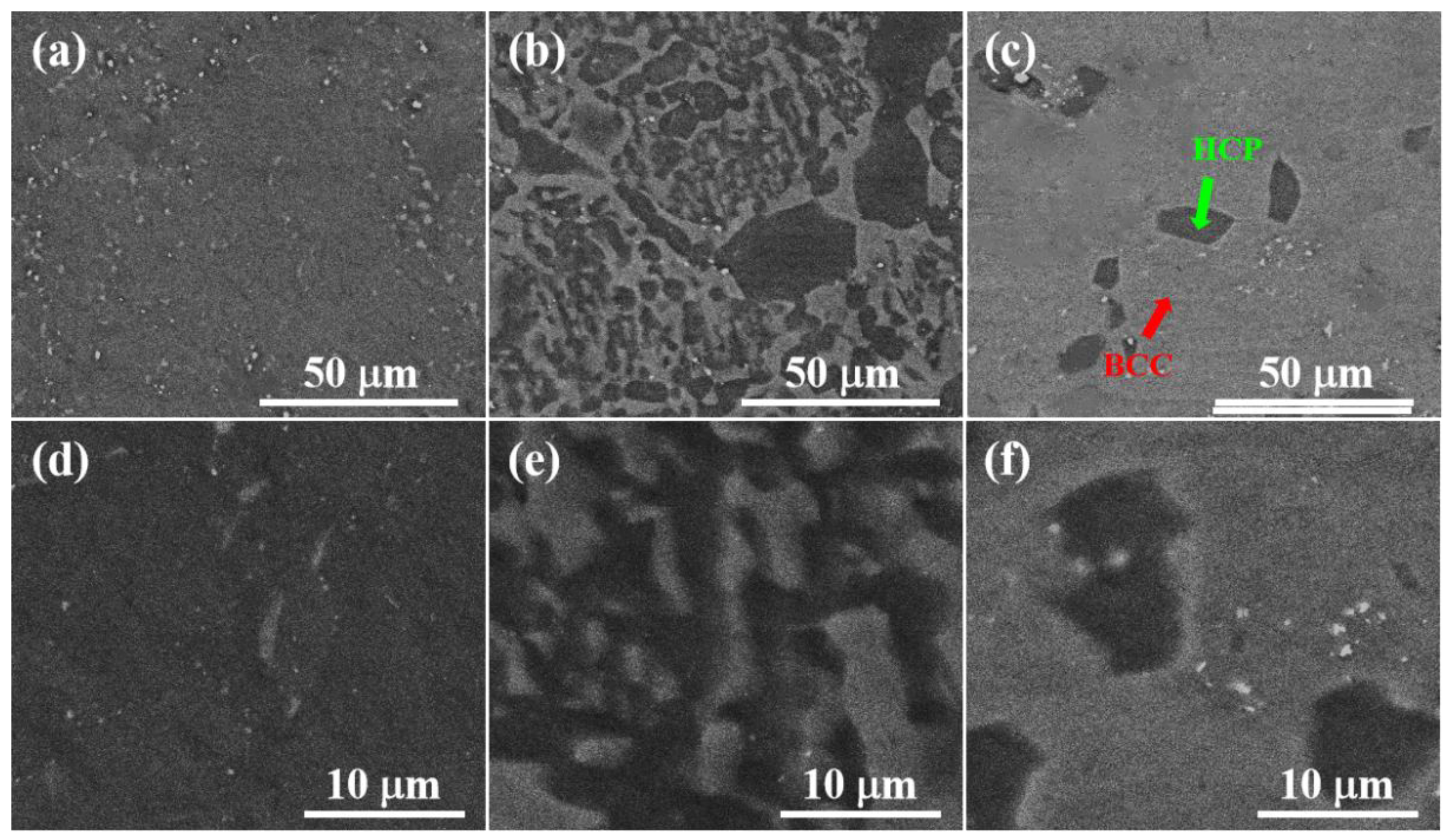

To investigate the microstructural evolution during the annealing process, BSE image analysis was performed on Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy annealed at 500 °C, 550 °C, and 600 °C for 30 minutes, as shown in

Figure 3(a)-(f). The dark regions represent the α phase, while the bright regions indicate the β phase.

Figure 3(a) displays the α single-phase microstructure of the sample annealed at 500°C, and

Figure 3(d) shows a magnified view where a small amount of β phase is observed within the α phase.

Figure 3(b) and (c) present the α + β dual-phase microstructures of the samples annealed at 550 °C and 600 °C, respectively. However, the volume fraction of the β phase at 600 °C is significantly lower than that at 550 °C. As the annealing temperature increases, the volume fraction of the β phase increases, which is consistent with the XRD results.

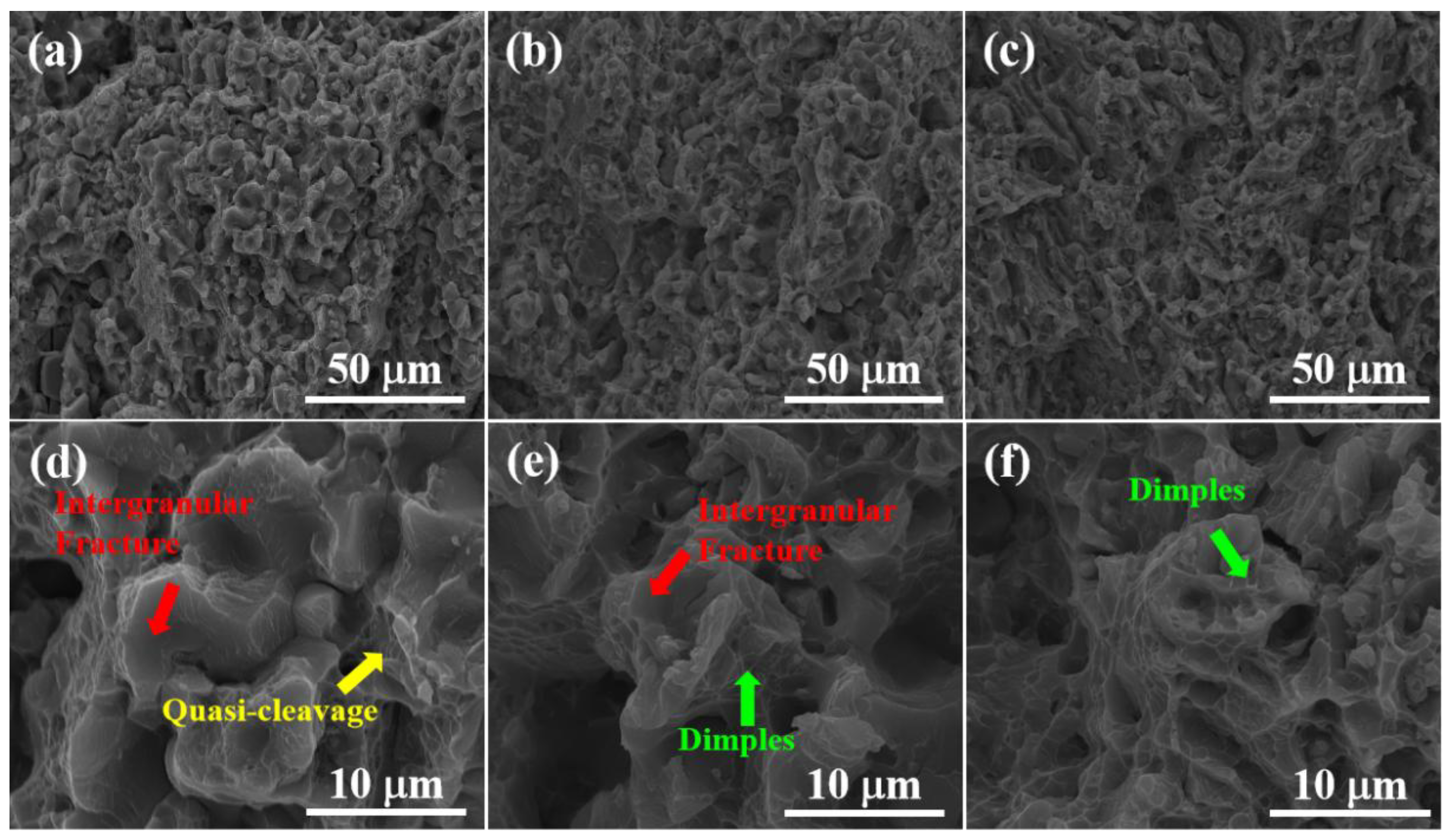

To reveal the damage and fracture mechanisms,

Figure 4 shows the typical fracture morphologies of the Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy annealed at different temperatures. The fracture surface of the Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy annealed at 500°C mainly exhibits intergranular fracture and quasi-cleavage fracture. For the alloy annealed at 550 °C, the quasi-cleavage fracture region decreases, while dimple fracture regions begin to appear. When the annealing temperature reaches 600 °C, the fracture surface is predominantly composed of ductile dimples, with an increased number of dimples, smaller sizes, and greater depths.

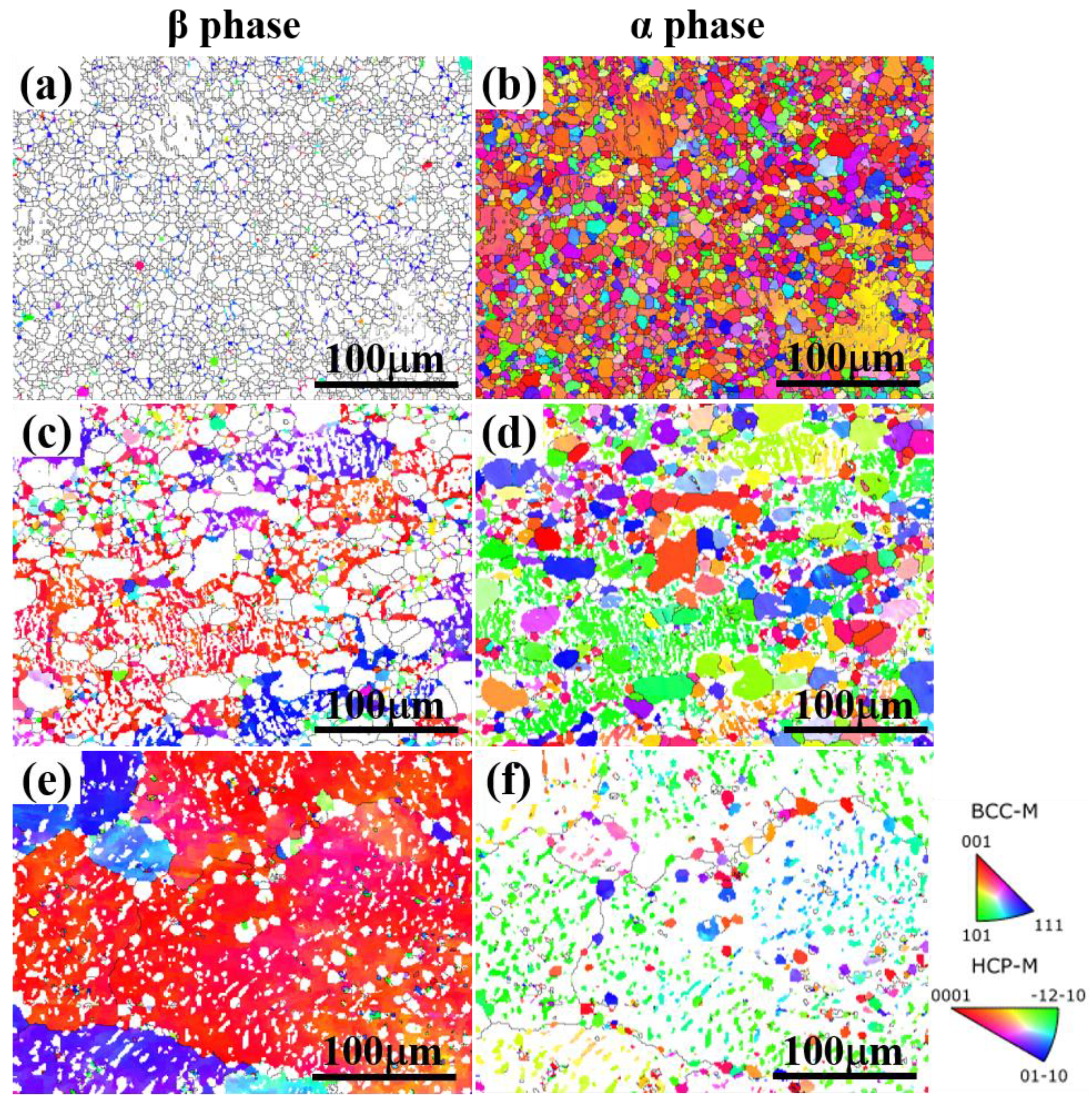

Figure 5 presents the Inverse Pole Figure (IPF) maps of the alloy, illustrating the texture orientations of the α and β grains. For the sample annealed at 500°C, distinct differences in the texture orientations of the α and β grains are observed. The texture proportion of β grains along the <111> direction is significantly higher than that along other directions, while the α grains exhibit a more diverse range of texture orientations.Further analysis of the texture orientation changes of α and β grains at different temperatures reveals that with increasing temperature, the texture proportion of β grains along the <111> direction gradually decreases, while the texture proportion along the <001> direction gradually increases. In contrast, the texture proportion of α grains along the <-12-10> direction significantly increases. However, overall, the Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy still exhibits a multi-orientation texture distribution at different temperatures, consistent with previous studies[

17,

18], indicating that its texture has a limited impact on the mechanical properties.

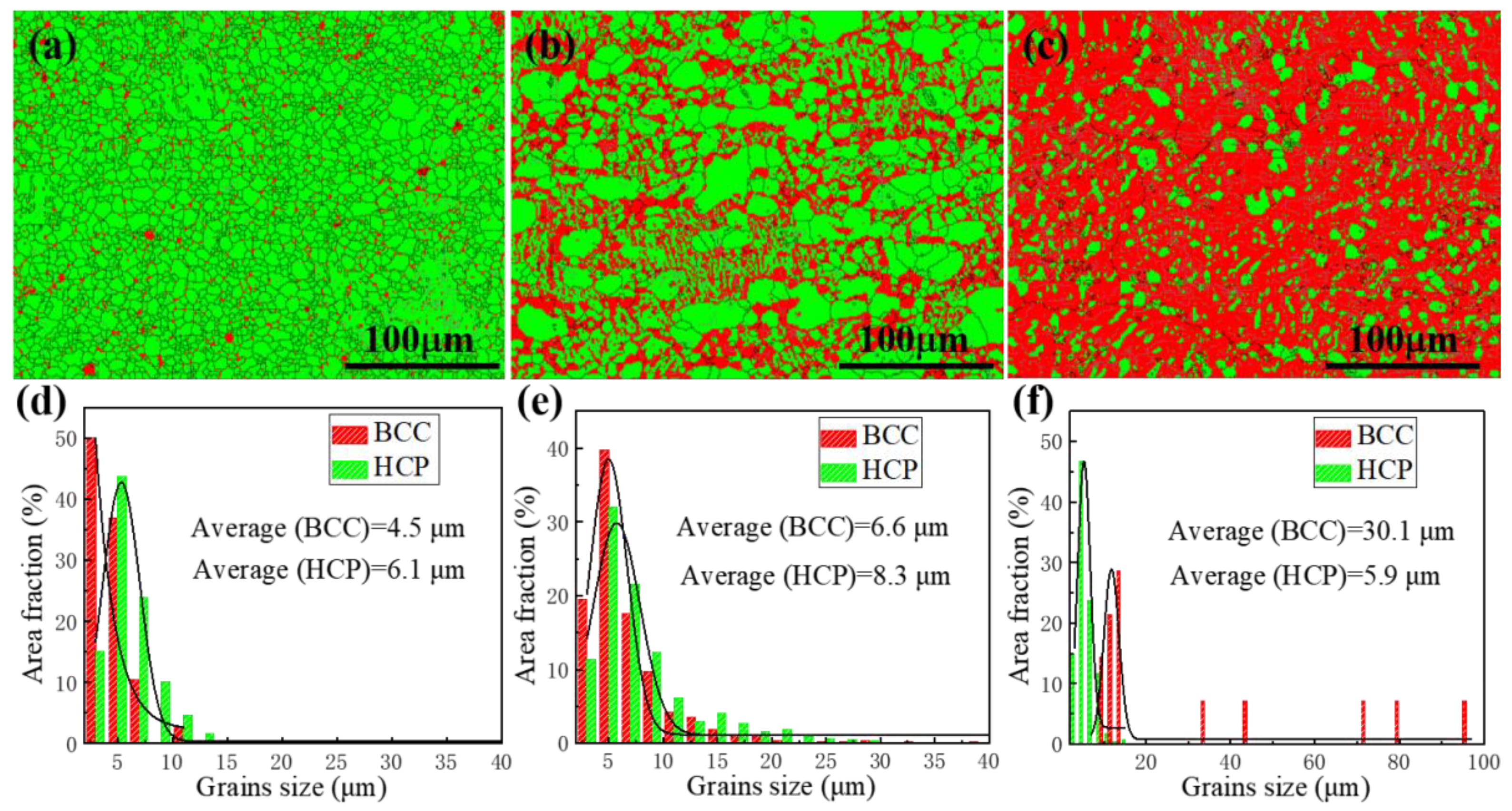

To further reveal the microscopic mechanisms behind the high strength and plasticity of the alloy after annealing at 600 °C, EBSD tests were conducted to investigate the evolution of the α and β phases and their corresponding grain sizes, as shown in

Figure 6. The green regions represent the α phase, while the red regions represent the β phase. With increasing annealing temperature, the volume fraction of the β phase increases, which is consistent with the XRD and BSE results. As shown in

Table 1, the volume fractions of the β phase in the samples annealed at 500 °C, 550 °C, and 600 °C are 5.2 %, 34.7 %, and 80 %, respectively. Compared to the α phase with a HCP structure, which possesses limited slip systems at room temperature, the β phase with a BCC structure exhibits 12 independent slip systems. Therefore, the elongation of the alloy increases with the increasing volume fraction of the β phase.

After annealing at 500 °C and 550 °C, the average grain size of the alloy remains below 10 μm. However, after annealing at 600 °C, the average grain size of the HCP phase is 5.9 μm, while the grain size of the BCC phase significantly increases to 30.1 μm, as shown in

Table 2. Notably, the grain size distribution of the HCP and BCC phases at 600°C exhibits a bimodal structure, where smaller HCP grains are uniformly distributed around the larger BCC grain boundaries, forming a "soft + hard" dual-phase heterogeneous structure. During tensile deformation, dislocation slip is first activated in the soft BCC phase regions, while the hard HCP phase regions remain in the elastic state. Due to the difference in mechanical behavior between these two regions, plastic incompatibility is generated between the soft and hard regions, where the plastic deformation of the soft regions is constrained by the hard regions. Although the soft regions bear more strain due to plastic deformation, the interfaces between the soft and hard regions must maintain continuity. Therefore, strain gradients are generated in the soft regions near the interfaces to satisfy the medium continuity, which requires the accumulation of geometrically necessary dislocations (GNDs) to coordinate the deformation. When the hard regions begin to undergo plastic deformation, GNDs mainly accumulate in the soft regions near the heterogeneous interfaces. Since GNDs cannot penetrate across the interfaces, back stress is generated in the soft regions to counteract the applied stress, making the soft regions appear stronger. Meanwhile, forward stress is formed in the hard regions, making the hard regions appear weaker. The coupling of these two effects manifests as macroscopic heterogeneous deformation-induced (HDI) strengthening, providing additional strength and strain hardening capacity. HDI strain hardening helps prevent necking during deformation, improving ductility and enhancing the synergy between heterogeneous strength and plasticity[

19,

20]. Therefore, the HDI strengthening effect is the key strengthening mechanism of the Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy after annealing.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the effect of annealing temperature on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy, aiming to explore the microstructure evolution and strengthening mechanisms of the α+β dual-phase structure. With the increase in annealing temperature, the volume fraction of the β phase increases, while the volume fraction of the α phase decreases. The β phase with a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure provides more favorable slip systems during tensile deformation, enhancing the alloy's ductility. As the annealing temperature increases from 500 °C to 600 °C, the grain size of the β phase grows to 30 μm, while the α phase reaches its minimum grain size of 5.9 μm, forming a "soft + hard" heterogeneous structure. The plasticity of the alloy gradually improves with increasing annealing temperature, while the yield strength slightly decreases. The alloy annealed at 600 °C exhibits the best combination of yield strength (280.1 MPa) and ductility (20.5 %). Further EBSD analysis reveals that the "soft + hard" heterogeneous microstructure composed of coarse-grained BCC phase and fine-grained HCP phase achieves an excellent balance of yield strength and ductility in the Mg-19.2 at.% Sc alloy annealed at 600 °C.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; methodology, W.Z., M.Z., and R.L.; software, W.Z. and M.Z.; validation, W.Z., M.Z., and R.L.; formal analysis, W.Z., M.Z., and R.L.; investigation, W.Z. and M.Z.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, W.Z., M.Z., and R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and M.Z.; visualization, N/A; supervision, N/A; project administration, N/A; funding acquisition, N/A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52401136)

References

- F. Xing, S. Li, D.D. Yin, et al. Recent progress in Mg-based alloys as a novel bioabsorbable biomaterials for orthopedic applications. Journal of Magnesium and Alloys, 2022, 10: 1428-1456. [CrossRef]

- B. Kim, C.H. Hong, J.C. Kim, et al. Factors affecting the grain refinement of extruded Mg-6Zn-0.5Zr alloy by Ca addition. Scripta Materialia, 2020, 187: 24-29. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhao, X. Chen, W. Ci, et al. Effect of Al element on microstructure, mechanical properties and damping capacity of LPSO-containing Mg-Y-Zn-Li alloy. Materials Characterization, 2024, 207: 113542. [CrossRef]

- R.X. Liu, W. Zhao, G.L. Wu, et al. A high-performance TRIP Mg-Sc-Zn alloy enhanced by fine grain strengthening and nano-precipitate strengthening. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2024, 33: 3874-3881. [CrossRef]

- H. Ovri, J. Markmann, J. Barthel, et al. Mechanistic origin of the enhanced strength and ductility in Mg-rare earth alloys. Acta Materialia, 2023, 224: 118550. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ogawa, D. Ando, Y. Sutou, et al. A lightweight shape-memory magnesium alloy. Science, 2016, 353 (6297): 368-370. [CrossRef]

- K. Yamagishi, Y. Ogawa, D. Ando, Y.J. Sutou. Adjustable room temperature deformation behavior of Mg-Sc alloy: From superelasticity to slip deformation via TRIP effect. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2023, 931: 167507. [CrossRef]

- D. Ando, Y. Ogawa, T. Suzuki, et al. Age-hardening effect by phase transformation of high Sc containing Mg alloy. Materials Letters, 2015, 161: 5-8. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ogawa, D. Ando, Y. Sutou, et al. Aging Effect of Mg-Sc Alloy with α+β Two-Phase Microstructure. Materials Transactions, 2016, 57 (7): 1119-1123. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ogawa, D. Ando, Y. Sutou,et al. Determination of α/β phase boundaries and mechanical characterization of Mg-Sc binary alloys. Materials Science & Engineering A, 2016, 670: 335-341. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ogawa, A. Singh, H. Somekawa. Activation of non-basal <c+a> slip incoarse-grained Mg-Sc alloy. Scripta Materialia, 2022, 218: 114830. [CrossRef]

- C. Xu, J.F. Wang, C. Wang, et al. Martensitic transformation behavior during tensile testing at room temperature in β-type Mg-35 wt%Sc alloy. Materials Science & Engineering: A, 2023, 865: 144602. [CrossRef]

- Z.M. Li, K.G. Pradeep, Y. Deng, et al. Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength-ductility trade-off. Nature, 2016, 534: 227-230. [CrossRef]

- Y.T. Zhu, X.L. Wu. Perspective on hetero-deformation induced (HDI) hardening and back stress. Materials Research Letters, 2019, 7: 393. [CrossRef]

- X.L. Wu, M.X. Yang, F.P. Yuan, et al. Heterogeneous lamella structure unites ultrafine-grain strength with coarse-grain ductility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112: 14501. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, D.T. Zhang, C. Qiu, et al. Achieving superior strength-ductility synergy in a heterostructured magnesium alloy via low-temperature extrusion and low-temperature annealing. Journal of Materials Science & Technology, 2023, 163: 32-44. [CrossRef]

- K. Yamagishi, D. Ando, Y. Sutou, Y. Ogawa. Texture formation through thermomechanical treatment and its effect on superelasticity in Mg-Sc shape memory alloy. Materials Transactions, 2020, 61: 2270-2275. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ogawa, D. Ando, Y. Sutou, J. Koike. Texture randomization of hexagonal close packed phase through hexagonal close packed/body centered cubic phase transformation in Mg-Sc alloy. Scripta Materialia, 2017, 128: 27-31. [CrossRef]

- L. Romero-Resendiz, M. El-Tahawy, T. Zhang, et al. Heterostructured stainless steel: Properties, current trends, and future perspectives. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports, 2022, 150: 100691. [CrossRef]

- L. Lu, H.Z. Zhao. Research Progress on Strengthening and Toughening Mechanisms of Heterogeneous Nanostructured Metals. Acta Metallurgica Sinica, 2022, 58(11): 1360-1370. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).