1. Introduction

Oil palm (

Elaeis guineensis Jacq., 2n = 2x = 32) is one of the main vegetable oil sources worldwide. The genus

Elaeis belongs to the palm family Palmae and order

Spadiciflorae, an important monocot member. The word

Elaeis originates from the Greek word Elaion, meaning oil, and guineensis points to the oil palm’s origin on the Guinea coast in Africa [

1]. Oil palm has the highest oil yields per hectare compared to other oil-producing crops, such as sunflower, cottonseed, peanut, soybeans, sesame and rapeseed [

2]. The crop requires 1500 to 3000 mm of rainfall and 25 to 32°C temperatures for optimum growth and production. Databases and existing literatures show that Indonesia and Malaysia are the world’s leading oil palm producing and exporting countries [

3,

4,

5].

Oil palm is mostly used for producing palm oil for food and manufacturing soap, lubricants, medicines, cosmetics, livestock feed, and biofuel. Despite its economic values oil palm production and yield have remained stagnant in Tanzania because of many production constraints. Tanzania’s current total edible palm oil production is 290,000 tons per annum, about 40% of the total annual demand. The country severely relies on imported palm oil, which accounts for 360,000 metric tons, representing 60% of the total demand for edible oil used in the country. The high importation cost of palm oil negatively affects the country’s economy and local production. Hence, there is a need to boost local oil palm production to benefit the agricultural industry and stakeholders involved in edible oil production and value chains.

In 2018, Tanzania produced 40,500 tons of palm oil from oil palm plantations covering 25,312 hectares, contributing to 15% of the total production [

6]. The remaining 85% of the edible oil sources are from other oil crops, including sunflower (

Helianthus annuus L.), groundnut (

Arachis hypogaea L.), cashew nut (

Anacardium occidentale L.), and sesame (

Sesamum indicum L.). Oil palm productivity in Tanzania is 1.6 tons per hectare, lower than the 5 to 8 tons per hectare reported elsewhere [

7]. The low productivity in the country is attributed to the use of low-yielding oil palm varieties, poor agronomic practices, lack of modern production technologies, lack of extension services, lack of modern processing technologies, low-quality planting material and old age of the existing oil palm trees. Most of the oil palm plantations (90%) in Tanzania are very old, leading to reduced productivity and low income.

In Tanzania, most oil palm growers (97.4%) use the Dura type, which is characterized by low palm oil yields. Dura are the oldest plantations established in the 1970s, and have never been replanted or replaced since. However, the Dura type is highly valued locally for its tolerance to drought and insect pests and diseases, adaptation to marginal production conditions, and high nutrient use efficiency.

Oil palm production is mainly concentrated in the Kigoma Region, which accounts for more than 80% of all oil palm production in Tanzania. Other producing regions are Mbeya, Tabora, Morogoro, Tanga and Ruvuma. In Kigoma Region, oil palm production is mainly concentrated in Kigoma Rural, Kigoma urban and Uvinza districts and partly in Buhigwe, Kasulu, and Kibondo districts. Currently, the Government of Tanzania has prioritised the oil palm crop to boost the local production of palm oil for sustainable edible oil supply and marketing. The renewed initiative led to the establishment of the Kihinga Research Center under the Tanzania Agricultural Research Institute (TARI) in 2018, which mandated on conducting and coordinating oil palm research and development in the country. The TARI-Kihinga has started the production of Tenera seeds by crossing selected Dura x Pisifera parents. This was aimed at developing new genetic resources and to deploying better-performing selections and seedlings to farmers. Yet some growers have dependent on farmers saved and recycled planting materials from Dura types due to some of its inherent merits. The oil palm genetic improvement program should be guided by the current and prevalent production constraints of the farmers, market- and consumer-preferred traits. The old oil palm plantations are low-yielding, attributable to several challenges that are yet to be systematically documented to guide large-scale production, breeding and policy support. New varieties should be developed based on the needs and preferences of the value chain, including farmers, traders, processors and consumers.

Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) is the multidisciplinary research approach that helps identify production constraints that focus on the farmers’ needs and value chains. Data gathered through PRA and market research help develop new varieties that meet market demands. Hence, it ensures the successful adoption of newly bred cultivars and their planting materials for enhanced genetic gain and livelihoods. Data acquired through PRA, focus group discussions and key informants help to understand farmers’ knowledge, experiences, production constraints, preferred traits and needs. These requirements will be incorporated in the planning and managing of breeding and agronomy research and development projects and programmes [

8]. Furthermore, the approach aims to strengthen farmers’ capacity to plan, make decisions, and take action to improve their own situation.

Previous PRA studies were conducted to initiate oil palm research programmes and develop policies to optimize oil palm production and improve farmers’ livelihoods in different agro-ecologies [

9,

10,

11,

12]. For instance, a PRA study was conducted in Benin by Akpo, Vissoh [

9], who reported poor genetic quality of the planting materials, poor allocation and geographical distribution of nursery sites, high cost of hybrid planting materials, poor seedlings care in nurseries leading to poor yield and quality gains. De Vos and Delabre [

11] reported unequal access to land and resources and a lack of participation by women during negotiations on land acquisition and production of oil palm in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. In Tanzania, no recent study has documented oil palm production opportunities, constraints, and the major preferred attributes required by farmers, markets, and the value chain in a new oil palm variety and product development. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to appraise oil palm production in Tanzania, focusing on constraints, opportunities and major farmers’ requirements to guide production and current and future crop breeding.

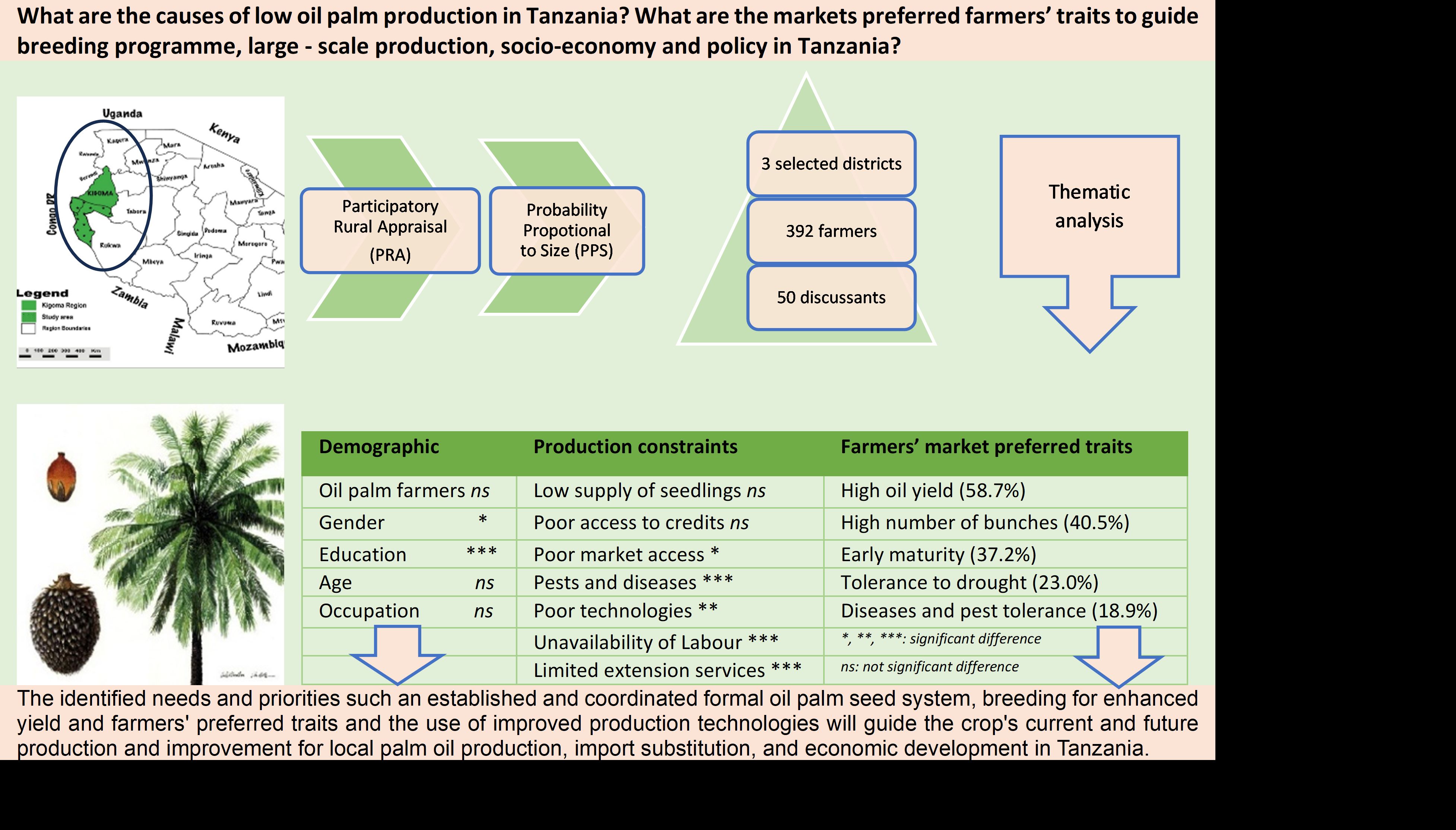

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Sites

The study was conducted in the Kigoma region, which is the leading oil palm-producing region in Tanzania. The Region is located in western Tanzania on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, between 3.6

0 and 6.5

0 South and longitude 29.5

0 and 30.5

0 East (

Figure 1). The region contributes 73% to the total oil palm production in the country [

6]. The regions have eight district councils that are involved in oil palm production.

Table 1 presents the details of the three districts, including Kigoma Urban, Kigoma Rural and Uvinza selected as major producers of oil palm in the region.

The districts are characterized by a tropical climate with unimodal rainfall from late October to May. During the study period, the mean annual rainfall in the area ranged from 986 mm to 1112.7 mm. Daily mean temperature ranged between 21.3° C to 23.8°C and varies with altitude. The soils are sand loamy, deep, and well-drained, especially in Kigoma urban. In high-altitude areas, soils are black and brown alluvial, while in low altitudes, soils are dark red loams with good drainage. Relative humidity ranged from 75.67 to 89.05%, whereas wind speed ranged from 2.40 to 2.77 meters per second.

2.2. Sampling Method

The Kigoma region was purposively selected for the study, given the high levels of oil palm production. The region contributes to 73% of the country’s total oil palm production. The Uvinza, Kigoma Rural and Kigoma Urban districts councils are the major palm oil producers in the Region and were selected for the study [

6]. The three district were represented by wards and villages as presented in

Table 2. The 29 villages were selected using a probability proportional to size (PPS) method from each selected district [

13]. A systematic random sampling procedure (SRS) was used to select smallholder oil palm farming households. The sample size was determined using Krejcie and Morgan [

14] method as shown in section 2.3.

2.3. Sample Size Determination

According to the National Statistical Bureau [

6], 29,255 households were involved in oil palm production in the 2021/2022 cropping season. The study adopted the method reported by Krejcie and Morgan [

14] to determine an adequate sample size. This method considered a sample size to provide accurate statistical estimates with a 5% sampling error and allow comparisons and stratification for significant associates. The following equation was used to derive the appropriate sample size for the survey.

where: -

n = required sample size,

= the table value of chi-square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841), i.e. (1.96 x 1.96 = 3.8416); confidence level at 95% (standard value is 1.96),

N = population size,

P = the population proportion/variance in the population (that is set at 0.50 to provide maximum sample size),

= the degree of accuracy/margin of error at 5% (standard value of 0.05).

During data collection, the sample size covered was 392 smallholder oil palm farmers to cater for the non-response error between the number of valid responses against the number of subjects selected to participate in the research [

15].

2.4. Data Collection

Quantitative data were collected from sampled smallholder oil palm farming households using a semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaires were coded using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and uploaded to the Kobo Collect Server for data collection. The questionnaire was programmed into Kobo Collect mobile data collection, where the validation rules, including skip pattern rules, mandatory rules, GPS location, drop-down menu, ranging rules, and logic of numbers between one variable and another, were created in the system. Using mobile data collection tools minimizes data entry errors and monitors the data collection.

With the help of agricultural extension officers, data were collected from the selected farming households at their households or farms or workplaces. The survey activities included introducing the research objective, verifying eligibility, obtaining informed consent, and conducting face-to-face interviews. Data collected involved the socio-economic status of the households, types of oil palm grown, production constraints, crop management practices, access to agro-inputs and farmers’ preferred traits.

The Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and Key Informants Interviews (KIIs) were used to collect qualitative data. One FGD was held in each of the selected districts, with each group comprising at least 18 participants. The FGD was comprised predominantly of open-ended and deep probing questions. In addition, tablets and voice recorders were used to collect FGD participants’ voices, photographs, and GPS locations, which were stored in the cloud server for reference and backup. Key informants’ interviews involved in-depth interviews conducted with selected knowledgeable individuals in the oil palm sector guided by a checklist of questions for data collection. A total of 54 farmers (18 from each district) participated both in FGDs and KIIs. Selected individuals were experienced farmers and community leaders known for their rich indigenous and technical knowledge of oil palm production. Data quality checks included data check and cleaning to produce reliable data files. The cleaning involved detecting and correcting inconsistencies and outliers in the data since extreme values are major contributors to sampling variability in survey estimates.

2.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data collected through questionnaires were downloaded from the server, saved in MS Excel, and then exported to the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS Inc, 2020) for alignment with the code book and value labels. Statistical analyses were done to summarise the category of the variables and their significant associations. The chi-square goodness of fit statistic was computed using significance tests to discern the association among the variables. The descriptive statistics analysis included proportions, frequencies, percentages, tabulations and cross-tabulations of critical variables. This allowed empirical analyses and descriptions of associations between the collected parameters across the study districts.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Households

A total of 392 smallholder farmers were interviewed during the study. All respondents indicated that they were involved in oil palm production. The results showed that 82.4% of interviewed oil palm growers were males, while 17.6% were females (

Table 3). The proportion of sampled males and females exhibited a similar trend across the study. The Pearson chi-square results revealed that gender and location of residence (district) significantly affected whether an oil palm farmer would be male or female (

X2 = 7.36;

p = 0.025). Education level significantly differed across the study area (

X2 = 25.087;

p = 0.000). Most respondents had attained primary school (80%), and a few had reached secondary school (7%). Conversely, 1% of the respondents had reached tertiary education, while 11.7% did not achieve formal education. Also, the age of respondents did not differ significantly among the studied districts (

X2 = 3.34;

p = 0.189).

Overall, 95.6% of the interviewed farmers were adults above 35 years old and able to make decisions on crop cultivation. Among the respondents, an average age of 56 years had an experience of about 24 years in oil palm farming activities. Other variable features of smallholder respondent farmers existed in the study area, including farming experience, farm size, and the number of oil palm trees owned by the farmer’s household. On average, a farmer had small land holdings of 1.45 hectares with 222 oil palm trees. The results showed a mean of 153 oil palm tree populations per hectare, above the recommended 123 oil palm trees in a rectangular or 142 in a triangular planting pattern at inter and inter-row spacing of 9 m x 9 m.

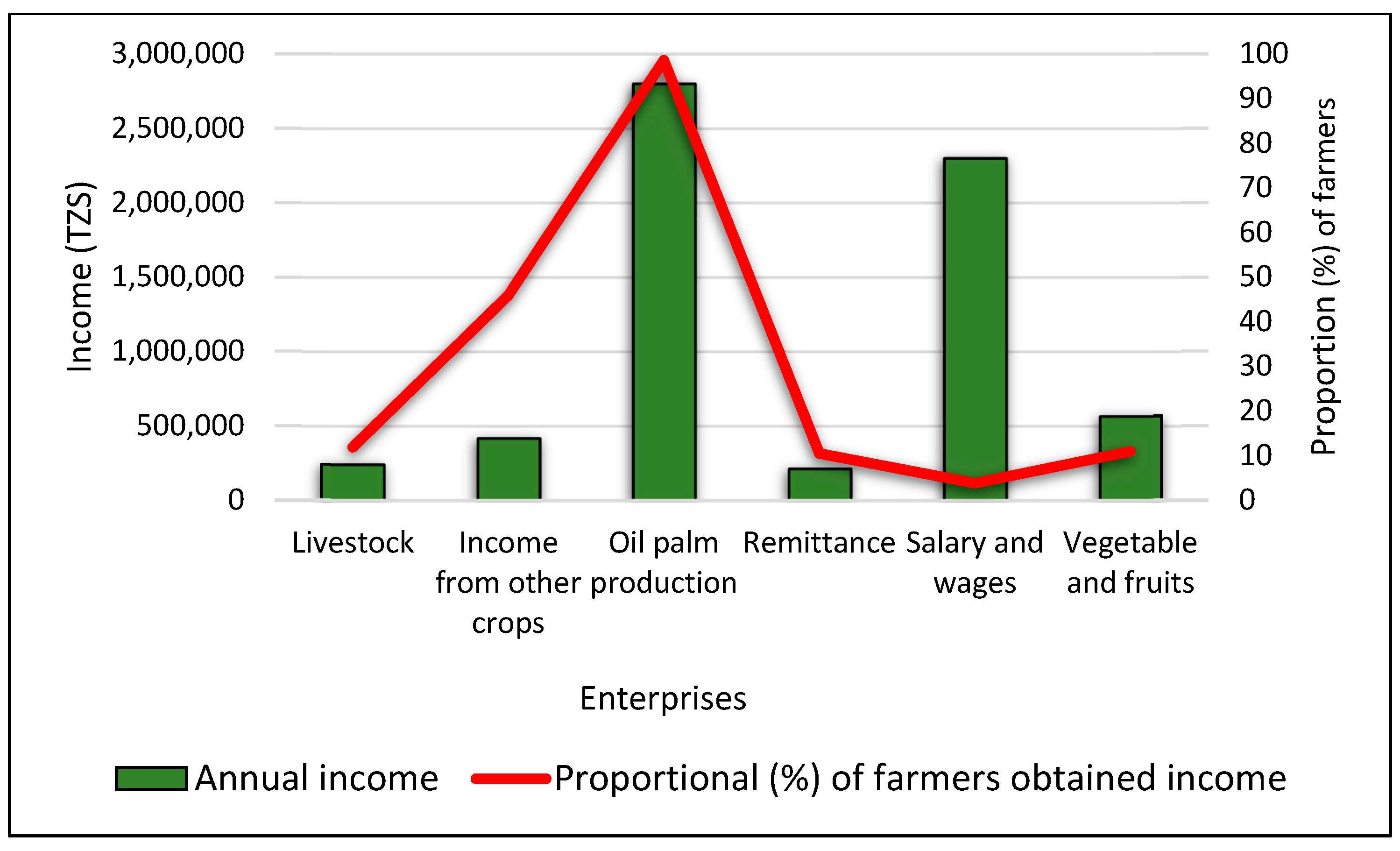

3.2. Socio-Economic Activities

The main economic activities identified in the study area were crop and livestock production, trade and hired workers (

Table 4). There were non-significant (

X2 = 5.36;

p = 0.499) differences in the respondent farmers engaged in different economic activities in the study area. About 96% of the respondents were involved in crop production as the main socio-economic activity, indicating a high contribution to the community livelihood compared with trade (3%), livestock production (<1%) and hired workers (<1%). When comparing income generated from different enterprises, oil palm production had the highest annual income for smallholder farmers across the districts. Each household earned an average income of about 2.8 million Tanzanian Shillings yearly (

Figure 2). This is attributed to 98.5% of the farmers being involved in oil palm production activities. However, 45.9% of the respondent farmers earned incomes from selling other produce, especially grain maize and beans and cassava roots. The average household income from the sale of the produce was 418,956 Tanzanian Shillings. Livestock, vegetables and fruits production and remittances provided an income of 10%. Only 4% of the respondent farmers earned income from salaries and wages. Their average annual income from salaries and wages was 2.3 million Tanzanian Shillings. The results support oil palm enterprise as the primary income source for farming households.

3.3. Oil Palm Production Constraints

The major farmers oil palm production constraints were inadequate supply of improved planting materials (reported by 82.7% of the respondents), poor access to credits (72.4%), high cost of production inputs (59.4%), poor market access (56.4%), insect pests and diseases (53.6%), and backward production technologies and knowledge gaps (45.4%). Relatively, the least ranked constraints were limited labour availability (38.3%), limited extension services (33.2%), soil infertility problem (21.2%), limited land size (20.4%), inadequate water for irrigation (13.8%) and erratic weather pattern (12.8%). The Chi–square analysis revealed unavailability of labour (X2 = 41.181; p = 0.000), limited extension services (X2 = 29.074; p = 0.000) and diseases and pests (X2 = 19.582; p = 0.000), differed significantly across the study areas. Additionally, lack of fertilizers (X2 = 14.218; p = 0.001), inappropriate technology and knowledge gap (X2 = 10.529; p = 0.005) and poor market access (X2 = 6.621; p = 0.036) differed significantly across districts.

3.4. Access to Extension Service and Improved Oil Palm Seedlings

Extension services are of paramount importance to oil palm farmers. Extension officers link researchers and farmers, guiding good crop management practices. In the study area, 31.8%, 37.9%, and 31.2% out of 88, 211 and 93 of the interviewed oil palm farmers in Uvinza, Kigoma Rural, and Kigoma Urban benefited from extension services in the 2021/22 planting season, respectively. About 35% out of the 392 respondents benefited from extension services. The Chi-square analysis revealed that there were non-significant differences between districts on access to extension services (X

2 = 1.776;

p = 0.441) and access to improved varieties of oil palm seedlings (X

2 = 5.580;

p = 0.061) (

Table 6). Field visits by extension officers, training offered by TARI staff, various popular articles published in newspapers, radios, television, and annual agricultural exhibitions (locally referred to as Nane Nane) were among the sources of information to crop growers. The sources enabled some farmers to make decisions, including using improved oil palm varieties, fertilizers and good agronomic practices, replacing old oil palm trees, accessing new agricultural lands and forming Agricultural Marketing Cooperative Society (AMCOS). However, most of the interviewed extension officers admitted inadequate knowledge of oil palm production and management practices due to a lack of relevant information on oil palm production to both farmers, extension officers and other stakeholders caused by the newness of the crop as the crop was not included in the curriculum of schools, colleges or universities.

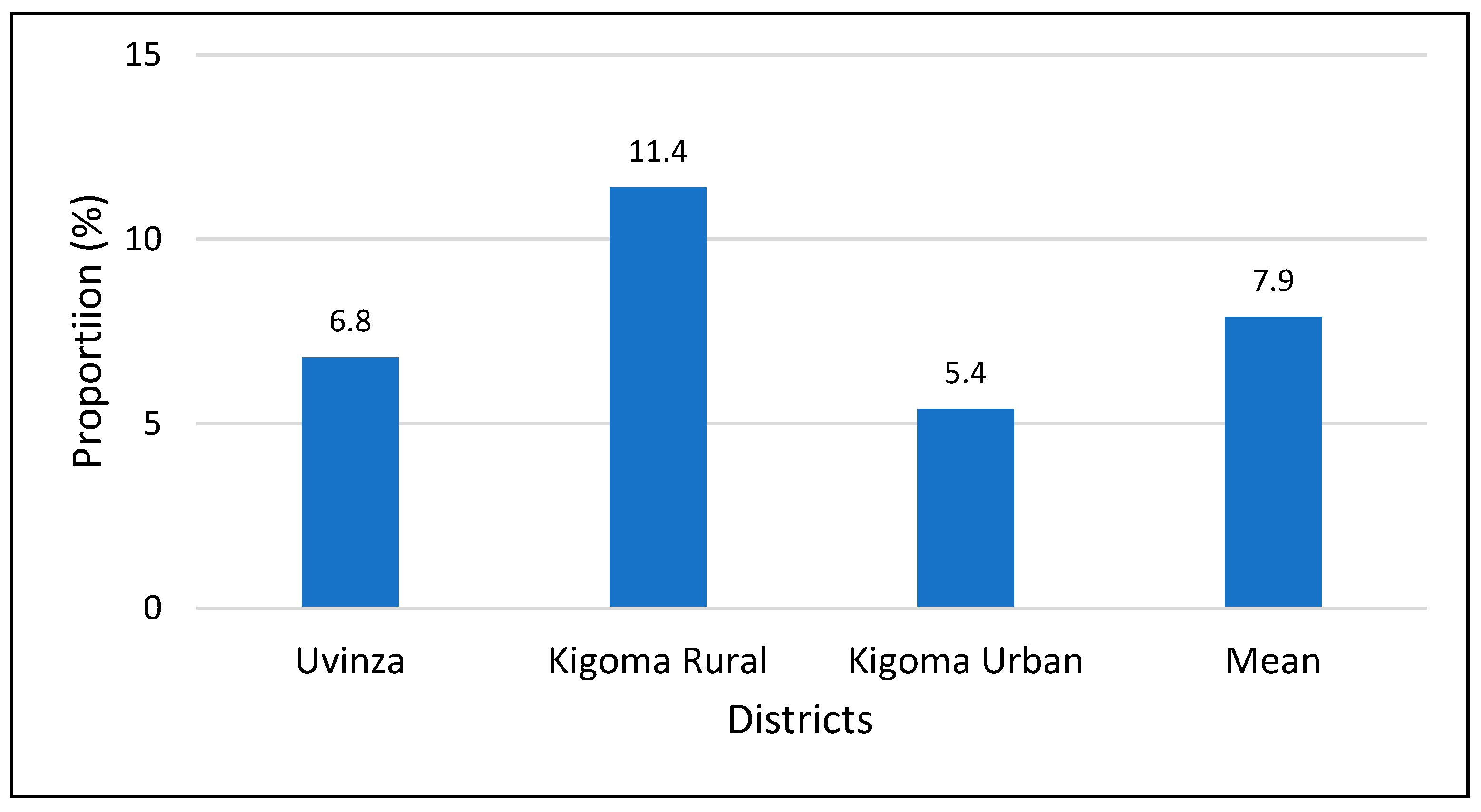

3.5. Use of Fertilizers for Oil Palm Production

The use of fertilizers in oil palm production in the study area was limited. Only 8.9% of respondents used organic fertilizer only (

Figure 3). The number of farmers who do not use chemical fertilisers was the highest in Kigoma Rural (11.4%) compared to Kigoma Urban (5.4%) and Uvinza (6.8%) districts. The Chi–square statistics analysis indicated a non-significant (X2 = 3.477; p = 0.176) difference on the use of fertilizers across districts (

Table 6). Most respondent farmers (80%) used farmyard manure, while Nitrogen: Phosphorus: Potassium (NPK), Calcium Ammonium Nitrate (CAN), Urea, Sulphate Ammonium (SA), and Minjingu Rock Phosphate (MRP) were used by only 20% respondent farmers. The fertilisers used by farmers were intended for the intercrops (e.g. maize, common beans and groundnuts) but not that of oil palm. The main reasons for the limited use of fertilizers in oil palm production were a lack of awareness and recommendations for fertilizer use in oil palm trees, negative perceptions about fertilizer use, prioritizing fertilizer over other food crops, high costs of fertilizers and inadequate capital.

3.6. Weed Management in Oil Palm Production

Most oil palm farmers (96%) are engaged in weed management of oil palm fields (

Table 7). Weeding was integrated into oil palm fields intercropped with the annual crops. The main weeding methods included hand hoe, slashing, burning, biological control, herbicides and cover crops as reported by 93%, 52.8%, 0.8%, 0.5%, 0.3%, and 0.3% of the respondents, respectively. Use of chemical herbicides was reported only in the Uvinza district, whereas burning was reported in the Uvinza and Kigoma Rural districts. The Chi – square test analysis showed that the number of farmers who weed (X

2 = 0.99;

p = 0.952) and the frequency of weeding per year (X

2 = 9.531;

p = 0.324) were not significantly different across the study area. In addition, the methods of weeding such as i.e. hand hoe (X

2 = 1.729;

p = 0.421), chemicals (X

2 = 3.444;

p = 0.179), burning (X

2 = 1.644;

p = 0.441), cover crops (X

2 = 1.240;

p = 0.538) and biological control (X

2 = 1.358;

p = 0.507) did not differ significantly across districts except for slashing (X

2 = 10.619;

p = 0.005).

3.7. Intercropping of Oil Palm with Major Annual Crops

Some 50% of the respondent farmers reported intercropping of oil palm trees with other major annual crops such as maize, cassava and common bean (

Table 8). However, intercropping has advantages and disadvantages depending on the age of the oil palm and the type of crop intercropped. Some intercropping was widely practised in the Kigoma Rural (reported by 61.1% of the respondents) compared to Kigoma Urban (51.6%) and Uvinza (45.5%) Districts (

Table 8). The major crops intercropped with oil palm were maize (reported by 35.7% of the respondents), cassava (26.8%), and common beans (24.7%) (

Table 8). Annual crops are widely intercropped, mainly at the early oil palm growth stages (1 to 7 years after planting), which is the tree establishment phase. Other crops intercropped with oil palm were pigeon pea (reported by 10.5% of the respondents), groundnut (10.5%), sweet potatoes (5.4%), cocoyam (8.9%), banana (5.6%), pineapple (1.3%), pawpaw (1.3%), cowpea (3.1%), passion fruit (1.0%) and avocado (0.5%). The Chi-square test analysis revealed that among the intercrops, cocoyam (X

2 = 27.773;

p = 0.000), banana (X

2 = 10.040;

p = 0.000), cassava (X

2 = 13.665;

p = 0.001), maize (X

2 = 10.690;

p = 0.005) and passion fruit (X

2 = 6.350;

p = 0.042) were practised significantly different across districts. There were non-significant differences for other remaining intercrops such as sweet potatoes (X

2 = 0.476; p = 0.788), pineapple (X

2 = 1.432;

p = 0.489), cowpea (X

2 = 0.640;

p = 0.969), pawpaw (X

2 = 1.432;

p = 0.489) and avocado (X

2 = 1.051;

p = 0.591). However, intercropping was mainly practised in Kigoma Rural and Kigoma Urban compared to the Uvinza District.

3.8. Oil Palm Types Cultivated in the Study Areas

The

Dura type was cultivated by most interviewed farmers (97.4%) in the study districts. However, more than 50% of the oil palm farmers had grown the

Tenera type. Conversely, the

Pisifera oil palm were cultivated by a limited number (2%) of respondents across the studied areas. The Chi–square test analysis revealed non-significant (

X2 = 7.325;

p = 0.835) differences among the farmers who cultivated

Dura, Tenera and

Pisifera types across Districts (

Table 9). No institute or company reported to breed or import the

Pisifera type for production or research purposes. The

Pisifera type appears by chance in

Dura and

Tenera fields. Farmers do not cultivate

Pisifera types because they are female sterile and only used by breeders as male parents during

Tenera hybrid seed production.

3.9. Farmers Preferred Traits of Oil Palm Types

Through focused group discussions farmers across the study areas voted for their ideal oil palm types for commercial production (Table 10). The main reported traits of preferences identified were high oil content and oil yield (reported by 58.7% of the respondents), high number of bunches per plant (40.5%), early maturity (37.2%), drought tolerance (23%) and diseases and pests’ resistance (18.9%). The chi–square test analysis revealed that the farmers preferred traits did not differ significantly (X2 = 7.621; p = 0.861) across districts. High oil content and many bunches per plant were commercially important traits across districts. Short stem height eases bunch harvesting. The overall ranks through FGD indicated diseases and pests’ resistance as the least rated traits. Fungal diseases such as ganoderma (Ganoderma boninense) and insect pests known as rhinoceros beetles (Oryctes rhinoceros) were the most common biotic constraints reported in Kigoma Rural and Kigoma Urban, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Description of Households

The results of this study showed that most of the respondents (95.6%) cultivating oil palm fields were adults (above 35 years old), while 4.34% were youth (> 35 years old). Elderly people have influence on making decisions regarding the size of land to cultivate, the time of planting, and the types of oil palm to cultivate. This indicated that experienced people were mostly undertaking oil palm farming activities. These results are further supported by Mwatawala, Maguta [

16] who reported a majority (74.1%) of respondents in Kigoma district had experience of more than 10 years in cultivation of oil palm regardless of technology adoption.

4.2. Crop Management Practices

In Tanzania, most oil palm land is owned by smallholder farmers and a few government facilities in Kwitanga and Kimbiji prisons in Kigoma and Dar es Salaam, respectively. Poorly managed plants with low productivity characterise the fields. High yields were reported in large-scale farmers whose fields are equipped with adequate infrastructures for weeding, fertilization, harvesting, diseases and pests management, postharvest loss management, and basic amenities to attract plantation workers [

17]. This is contrary to interviewed farmers who reported low use of fertilizers, low frequencies of weeding, and poor knowledge oil palm crop production, intercropping techniques and postharvest loss management.

4.3. Fertilizer Application

The use of fertilisers was erratic and low in Uvinza, Kigoma Urban and Kigoma Rural. Only 9% of farmers applied fertilizers. The Ministry of Agriculture has subsidized fertilisers effective since 15 August 2022. However, the high cost of fertilizers, unavailability, and lack of technical knowledge on its importance to soil nutrient improvement were identified as the main reasons for limited use in oil palm production. Enhancing oil palm yields hinges on good and improved planting material and best agronomic management practices, especially on efficient and optimal fertilizer use [

18,

19,

20]. The quantity of fertilizer applied is influenced by farming practices, soil fertility, and farmers’ knowledge of application rates [

19]. The study revealed that fertiliser management on oil palm farms is often based on traditional methods rather than scientific recommendations, attributed to limited research information on optimal fertiliser dosages. Therefore, education on the best fertiliser types and application rates for oil palm production is crucial for enhancing farmers’ knowledge, increasing yield per unit area, and boosting farmer income and national agricultural productivity.

4.4. Weeding

Weeds are harmful and unwanted plant species that reduce crop growth performance and yield in the field, including oil palm plantations. Weeds interfere with other agricultural operations such as fertilisation, harvesting, pest control, and disease control [

21,

22]. They indirectly affect crops by harbouring parasitic plants, pathogen and insect pests and eventually reducing the value of the cropland. In addition, weed decreases the yield of the plantation, increases the cost of production and exposes the oil palm field to fire [

23].

In the current study, 96% of the respondents control weeds by hand hoe (93.1%), herbicides (0.3%), burning (0.8%) and cover crops (0.3%). However, weeds were removed only once in oil palm fields intercropped with other crops. Weeding once yearly is less effective than four times reported in other plantations [

24]. Inefficient weeding is attributed to a lack of awareness of good management practices, high cost of inputs, lack of capital, and prioritisation of oil palm cultivation over other food crops. Since the 2020/21 season, the oil palm sector in Tanzania has grown remarkably due to support from the government through TARI and the private sector on the input supply chain. Distribution of improved seedlings, training on good agronomic practices and dissemination of related technologies to farmers and extension officers by TARI has recently engaged many new farmers along with improvement in oil palm production knowledge.

The expansion of new farms is accelerating the commercial mono-cropping farming system, and farmers have to adopt an integrated eco-friendly approach for weed control, especially in young trees, to prevent growth inhibition and reduced yield. Iddris, Formaglio [

22] reported productivity of 50% higher in large-scale plantations compared to smallholder-owned farms, which was primarily driven by fertilisation and weed control. More studies on identifying weed species density, composition and population change, community dynamics, species diversity, and efficacy of different control measures will lead to appropriate management decisions.

4.5. Intercropping in Oil Palm

Apart from providing farmers with additional food and income, intercropping promotes multiple livelihood options that benefit smallholder farmers and other stakeholders [

25]. Crops such as beans, maize, sweet potatoes, banana, soyabean, peas and groundnuts do not compete when planted between rows of young oil palm plants. At the early development stage, usually 4 to 5 years after planting, intercropping reduces the cost of weeding, improves soil fertility through nitrogen fixation when intercropped with legumes and improves nutritional requirements, biodiversity, and sustainability and resilience for price fluctuation of fresh fruit bunch (FFBs) [

25]. However, when intercropping with perennial crops, planting densities and crop integration/combination must be carefully considered to minimize the competition effect, which can lead to reduced oil palm yield. The general observations from the current intercrops revealed that farmers intercrop without technical know-how. This was confirmed with some farmers who intercrop cassava and pineapples in the oil palm field without a proper fertilization program for potassium replacement. It has been reported that intercropping of cassava and pineapples with oil palm is not profitable unless there is an appropriate fertilisation program that would ensure the replacement of potassium, which is constantly under competition with oil palm with such intercrops [

26,

27,

28]. Dhandapani, Girkin [

29] reported that intercropping reduces the negative environmental impacts of monoculture oil palm production. However, reduced yields were reported due to competition for nutrients, water and light [

30]. The current analysis indicated that farmers’ need to be educated on the advantages and disadvantages of intercropping the crops and the choice of relevant intercrops in the oil palm fields. Training of farmers on intercropping technologies that increase income, resilience and biodiversity is required.

4.6. Access to Extension Services

Efficient extension service is the best approach to accelerate agricultural technologies and knowledge transfer from research to smallholder farmers [

31,

32,

33,

34]. In Tanzania, the government offers extension service through the District Agricultural, Livestock and Fishery Officer (DALFO). One extension officer coordinates and delivers services in one ward, an administrative sub-unit within a district comprising two or three villages. The current average ratio of extension officers to farmers is 1: 2000. Reportedly, the government extension officers represent only 10% of farming households in Tanzania. In addition, an extension officer works on different crops with a biased priority depending on the district’s priority. Most of the interviewed extension officers were new and inexperienced and had an inadequate understanding of good agronomic practices in oil palm production. Before 2018, oil palm in Tanzania was not a priority crop; it was traditionally cultivated and not even taught in schools, colleges, and universities. The crop is still new to most extension officers except those recently trained by TARI. In this regard, the government should adopt a new teaching curriculum to prepare teachers in schools, colleges and universities for oil palm production and improvement. Basaruddin, Kannan [

34] suggested that an extension officer needs to be well-trained and equipped with the proper knowledge and skills. Extension officers should be trained occasionally to update them on modern oil palm farming and technologies so that they can act as trainers and advisors of farmers in their working areas. Cloete, Bahta [

35] stated that the success of extension works needs clear goals, principles, teaching methods and teaching tools for smallholder farmers. Similarly, Basaruddin, Kannan [

34] reported that an ineffective extension system resulted from an inadequate number of extension workers, additional assigned duties, poor coordination and supervision of farmers and a lack of knowledge of extension officers. Extension officers need to improve their skills and knowledge on oil palm production through access to training programs organized by TARI, partners and networking with smallholder farmers through diverse teaching methods and time dedication.

4.7. Farmer’s Perceptions of Types of Oil Palm Genotypes Grown

Across the study area, farmers acknowledged the importance of

Tenera hybrid. Among the interviewed farmers, 97.4%, 54.6% and 2% planted

Dura,

Tenera and

Pisifera, respectively.

Dura has a thick shell (2 – 8 mm), thin mesocarp (35 – 55%) with low oil content, whereas

Pisifera is shell-less with a 95% mesocarp. Despite having a high mesocarp,

Pisifera does not produce bunches and may bear fruits with a low oil-to-bunch ratio compared to

Tenera [

17].

Pisifera is a female sterile or semi-fertile with varying degrees of sterility but used as a male parent in

Tenera hybrid seed production since its male inflorescence produces viable pollens [

1,

17].

Tenera has thin shell (0.5 – 4 mm), thick mesocarp (50 – 96%), and high oil content, and the only form of oil palm fruits used for commercial planting. The thick-shell in

Dura genotype is controlled by the dominant homozygote gene (

sh+sh+), whereas the shell-less in

Pisifera is controlled by the recessive homozygote gene (

sh-sh-). The cross between

Dura and

Pisifera (D x P) results in a heterozygote

Tenera hybrid (

sh+sh-) with a thin-shell and thick mesocarp [

1,

17].

Generally, access to improved Tenera in the study area was limited, suggesting the need to disseminate an improved hybrid to replace Dura. Many farmers reported the need for Tenera hybrid for their field expansion and replacing old trees planted in the 1970s. However, few farmers claimed that improved Tenera hybrid planting materials have a shorter life span than their locally grown Dura.

4.8. Farmers Preferred Traits of Oil Palm

Farmers in the study area preferred oil palm trees with high oil contents and many bunches. Goh, Mahamooth [

17] reported high oil yield and many bunches per tress, high bunch weight and oil-to-bunch ratio as breeder’s traits of preference. These traits were reported to be controlled by many minor genes. Goh, Mahamooth [

17] proposed that recurrent selection, like modified or reciprocal recurrent selection (RRS), is a useful method for improving oil palm. Conversely, farmers preferred short-stem oil palm to reduce labour costs during pruning and harvesting. Farmers in Kalenge and Kandaga in Uvinza claimed oil palm harvesting costs to be charged based on plant height where, harvesting from taller tree was expensive than shot trees. Somyong, Walayaporn [

36] proposed an oil palm breeding program focusing on short varieties that may reduce harvesting costs. Other farmers’ preferred traits were tolerance to drought and disease tolerance, such as Ganoderma, basal stem rot and

Fusarium wilt. These diseases were primarily reported in Kigoma Rural and Kigoma Urban. The importance of considering farmers’ traits of preferences were reported in earlier studies. Mrema, Shimelis [

37] and Kagimbo, Shimelis [

38] proposed that any crop improvement program should consider the farmers preferred traits in a newly developed variety for a high adoption rate and food security. Kagimbo, Shimelis [

38] pinpointed that, in some cases in Africa, farmers reject variety with superlative agronomic performance if the newly released variety lack their traits of interest. Therefore, developing an improved

Tenera genotype resilient to climate change with farmers preferred traits is key for increased adoption in the study area.

4.9. Oil Palm Production Constraints

The oil palm industry involves different actors in production, processing and marketing. However, this study focused on the production challenges, opportunities and farmers’ perceptions and preferred traits of oil palm. Several challenges along the oil palm value chain affected production and marketing such as inadequate supply of improved seedlings which 82.7% farmers reported, the need for capital/credit to finance oil palm production reported by 72.4% of the respondents. Other challenges included are high input costs (59.4%), unreliable markets (56.4%), and the prevalence of pests and disease infestation (53.6%), especially rhinoceros beetles (rhinoceros oryctes) and Ganoderma (Ganoderma boninense) respectively, which affects most oil palm plants. These findings imply that enabling access to financial services for oil palm farmers and access to improved seeds/seedlings will increase the efficiency of the oil palm industry in the country. Therefore, the intervention should target developing improved oil palm planting material with tolerance to pests and diseases for farmers and improving access to financial services relevant to oil palm farmers.

5. Conclusions

Oil palm is one of the primary vegetable oil sources worldwide, including in Tanzania. It is a mostly high oil-producing crop compared to other vegetable oil crops. Despite its lucrative and potential uses, oil palm production has remained stagnant in Tanzania because of many production constraints. In this study, inadequate supply of improved planting materials, poor access to credits, high cost of production inputs, poor market access, insect pests and diseases, poor production technologies and knowledge gaps were the main reasons affecting oil palm production and productivity. Furthermore, limited use of fertilizers, use of an improved planting materials, low frequency of weeding, inadequate extension services, intercropping that does not follow proper crop combination, poor methods of weed control and lack of farmers’ preferred traits were additional challenges for oil palm production. Other constraints may need further government interventions such as generating enabling policies and institutional environments to enhance productivity, profitability, and competitive value chain development driven by strengthened public and private sector participation.

Currently, TARI Kihinga is producing improved seeds of oil palm of Tenera type through crossing between Dura and Pisifera for distribution to farmers. In this study, the use of local planting material was high and primarily reported in the fields that were planted before the institute’s existence. While these initiatives are enduring, the institute should ensure a systematic breeding programme aiming at improving oil palm varieties for high yield and farmers’ preferred traits. Also, there should be other initiatives such as training programs for smallholder farmers and extension officers on good agricultural practices to support the expansion of new farms, and replanting/replacement efforts of Dura by improved Tenera hybrid. The government should create enabling policies that effectively coordinate the relevant public and private sectors in improving the oil palm sector at the local, national and international levels. Also, there is a need to ensure an established and coordinated formal oil palm seed system to prevent farmers from planting locally unimproved material. This will help to increase the adoption of the newly improved varieties for local palm oil production, import substitution, and economic development in Tanzania.

Author Contributions

Writing – original draft, M.S.S; Methodology, M.S.S. and H.S.; Formal analysis, M.S.S, Validation, E.J.M.; Result estimation, M.S.S. and H.S.; Writing – review and editing, F.M.K., E.J.M. and H.S.; Conceptualization, M.S.S. and H.S.; Resources, F.M.K and E.J.M.; Supervision, H.S., E.J.M. and F.M.K.; Funding acquisition F.M.K and E.J.M.

Funding

This work was funded by the Government of Tanzania through the Ministry of Agriculture under the Oil Palm Development Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to farmers in the study area who made this participatory rural appraisal study possible. The local government authority through Regional Administrative Office (RAS), the offices of District Agricultural and Livestock and Fishery officer (DALFO) under the District Executive Directors (DEDs) offices in the study area are also gratefully acknowledged. We gratefully thanks to Dr Nicholaus Kuboja and Dr Joseph Kangile for their methodological guidance on the data collection activities and analysis. We extend our appreciation to TARI – Kihinga scientists for participating in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Corley, R.H.V. and P.B. Tinker, The oil palm. 2008: John Wiley & Sons.

- Murphy, D.J., K. Goggin, and R.R.M. Paterson, Oil palm in the 2020s and beyond: challenges and solutions. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience, 2021. 2: p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H., et al., Oil palm-and rubber-driven deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia (2000–2021) and efforts toward zero deforestation commitments. Agroforestry Systems, 2025. 99(1): p. 20.

- Trend, G.M. and L. Outlook, 1 Palm Oil Business. The Palm Oil Export Market: Trends, Challenges, and Future Strategies for Sustainability, 2025: p. 1.

- Ali, M.S., S.K. Vaiappuri, and S. Tariq, Malaysian Oil Palm Industry: A View on the Economic, Social, and Environmental Aspects, in Economics and Environmental Responsibility in the Global Beverage Industry. 2024, IGI Global. p. 268-284.

- NBS, National Sample Census of Agriculture 2019/20: National Report. 2021, National Bureau of Statistics (NBS): Dodoma, Tanzania. p. 361.

- Kannan, P., et al., A review on the malaysian sustainable palm oil certification process among independent oil palm smallholders. J. Oil Palm Res, 2021. 33: p. 171-180. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R., Rural appraisal: rapid, relaxed and participatory. Vol. 311. 1992: Institute of Development Studies Brighton.

- Akpo, E., et al., A participatory diagnostic study of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) seed system in Benin. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 2012. 60: p. 15-27. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.O., et al., Negotiating development narratives within large-scale oil palm projects on village lands in Sarawak, Malaysia. The Geographical Journal, 2016. 182(4): p. 364-374. [CrossRef]

- De Vos, R. and I. Delabre, Spaces for participation and resistance: gendered experiences of oil palm plantation development. Geoforum, 2018. 96: p. 217-226.

- Delabre, I. and C. Okereke, Palm oil, power, and participation: The political ecology of social impact assessment. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 2020. 3(3): p. 642-662. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, C.J., Probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling. Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, 2014: p. 1-5.

- Krejcie, R. and D. Morgan, Sample size determination table. Educational and psychological Measurement, 1970. 30: p. 607-610.

- Al-Subaihi, A.A., Sample size determination. Influencing factors and calculation strategies for survey research. Neurosciences Journal, 2003. 8(2): p. 79-86.

- Mwatawala, H.W., M.M. Maguta, and A.E. Kazanye, Factors Influencing the Adoption of Improved Oil Palm Variety in Kigoma Rural District of Tanzania. 2022.

- Goh, K., et al., Managing soil environment and its major impact on oil palm nutrition and productivity in Malaysia. Advanced Agriecological Research Sdn. Bhd, 2016. 11: p. 1-71.

- Azahari, D. Impact of chemical fertilizer on soil fertility of oil palm plantations in relation to productivity and environment. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2023. IOP Publishing.

- Damayanti, Y., et al., Technical Efficiency Analysis of Fertilizer use for Oil Palm Plantations Self-Help Patterns in Muaro Jambi Regency using Methods Data Envelopment Analysis. International Journal of Horticulture, Agriculture and Food Science (IJHAF), 2023. 7(1): p. 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Wahyuningsih, R., L. Marchand, and J. Caliman. Impact of inorganic fertilizer to soil biological activity in an oil palm plantation. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2019. IOP Publishing.

- Sahari, B., et al. Weed diversity in oil palm plantation: benefit from the unexpected ground cover community. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2023. IOP Publishing.

- Iddris, N.A.-A., et al., Mechanical weeding enhances ecosystem multifunctionality and profit in industrial oil palm. Nature Sustainability, 2023. 6(6): p. 683-695. [CrossRef]

- Ali, N., et al. Weeds diversity in oil palm plantation at Segamat, Johor. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2021. IOP Publishing.

- Formaglio, G., et al., Mulching with pruned fronds promotes the internal soil N cycling and soil fertility in a large-scale oil palm plantation. Biogeochemistry, 2021. 154(1): p. 63-80. [CrossRef]

- Namanji, S., C. Ssekyewa, and M. Slingerland, Intercropping food and cash crops with oil palm–Experiences in Uganda and why it makes sense. 2021.

- van Leeuwen, S., Analysis of a pineapple-oil palm intercropping system in Malaysia. 2019, MSc dissertation, Wageningen University.

- Agele, S.O., et al., Oil Palm-Based Cropping Systems of the Humid Tropics: Addressing Production Sustainability, Resource Efficiency, Food Security and Livelihood Challenges. Elaeis guineensis, 2022: p. 279.

- Razak, S.A., et al., Smallholdings with high oil palm yield also support high bird species richness and diverse feeding guilds. Environmental Research Letters, 2020. 15(9): p. 094031. [CrossRef]

- Dhandapani, S., et al., Is intercropping an environmentally-wise alternative to established oil palm monoculture in tropical peatlands? Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 2020. 3: p. 70.

- Koussihouèdé, H., et al., Comparative analysis of nutritional status and growth of immature oil palm in various intercropping systems in southern Benin. Experimental Agriculture, 2020. 56(3): p. 371-386. [CrossRef]

- PENG, T., et al., The role of social media applications in palm oil extension services in Malaysia. Akademika, 2021: p. 145-156.

- Somanje, A.N., G. Mohan, and O. Saito, Evaluating farmers’ perception toward the effectiveness of agricultural extension services in Ghana and Zambia. Agriculture & Food Security, 2021. 10: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Lawal, K.F., Perceived Effectiveness of Public Extension Services Among Maize Based Smallholder Farmers in Kwara State, Nigeria. 2023, Kwara State University (Nigeria).

- Basaruddin, N.H., et al., Acceptance Level of Independent Oil Palm Smallholders in Malaysia Towards Extension Services. Int. J. Mod. Trends Soc. Sci, 2021. 4: p. 17-33. [CrossRef]

- Cloete, P., et al., Perception and understanding of agricultural extension: perspective of farmers and public agricultural extension in Taba Nchu. South African Journal of Agricultural Extension, 2019. 47(3): p. 14-31. [CrossRef]

- Somyong, S., et al., Identifying a DELLA gene as a height controlling gene in oil palm. Chiang Mai J Sci, 2019. 46(1): p. 32-45.

- Mrema, E., et al., Farmers’ perceptions of sorghum production constraints and Striga control practices in semi-arid areas of Tanzania. International Journal of Pest Management, 2017. 63(2): p. 146-156. [CrossRef]

- Kagimbo, F., H. Shimelis, and J. Sibiya, Sweet potato weevil damage, production constraints, and variety preferences in western Tanzania: Farmers’ perception. Journal of Crop Improvement, 2018. 32(1): p. 107-123.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).