Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

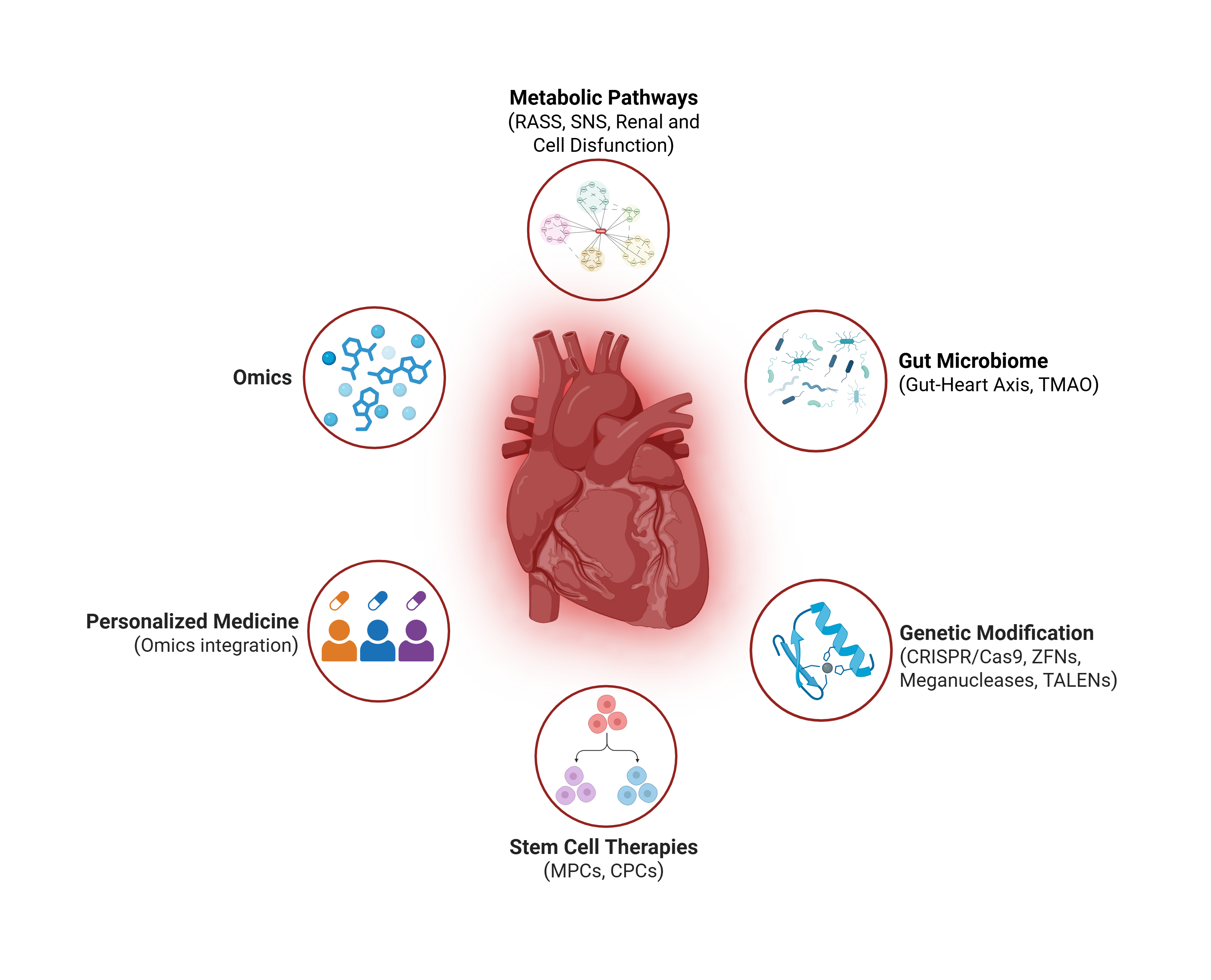

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Classic and Contemporary Metabolic Pathways in Heart Failure

2.1. Neurohormonal Activation

2.2. Renal Function

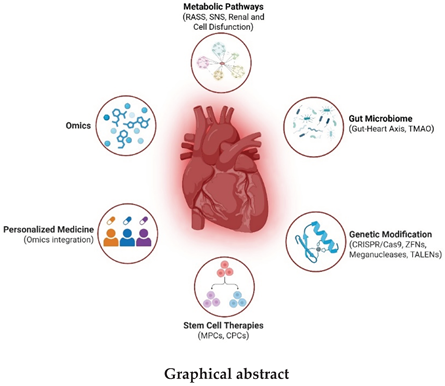

3. Microbiome in Heart Failure: The Gut-Heart Axis

3.1. Gut Microbiome and Heart-Gut Axis

3.2. Disorders of Intestinal Metabolism in HF

3.3. Trimethylamine N-Oxide

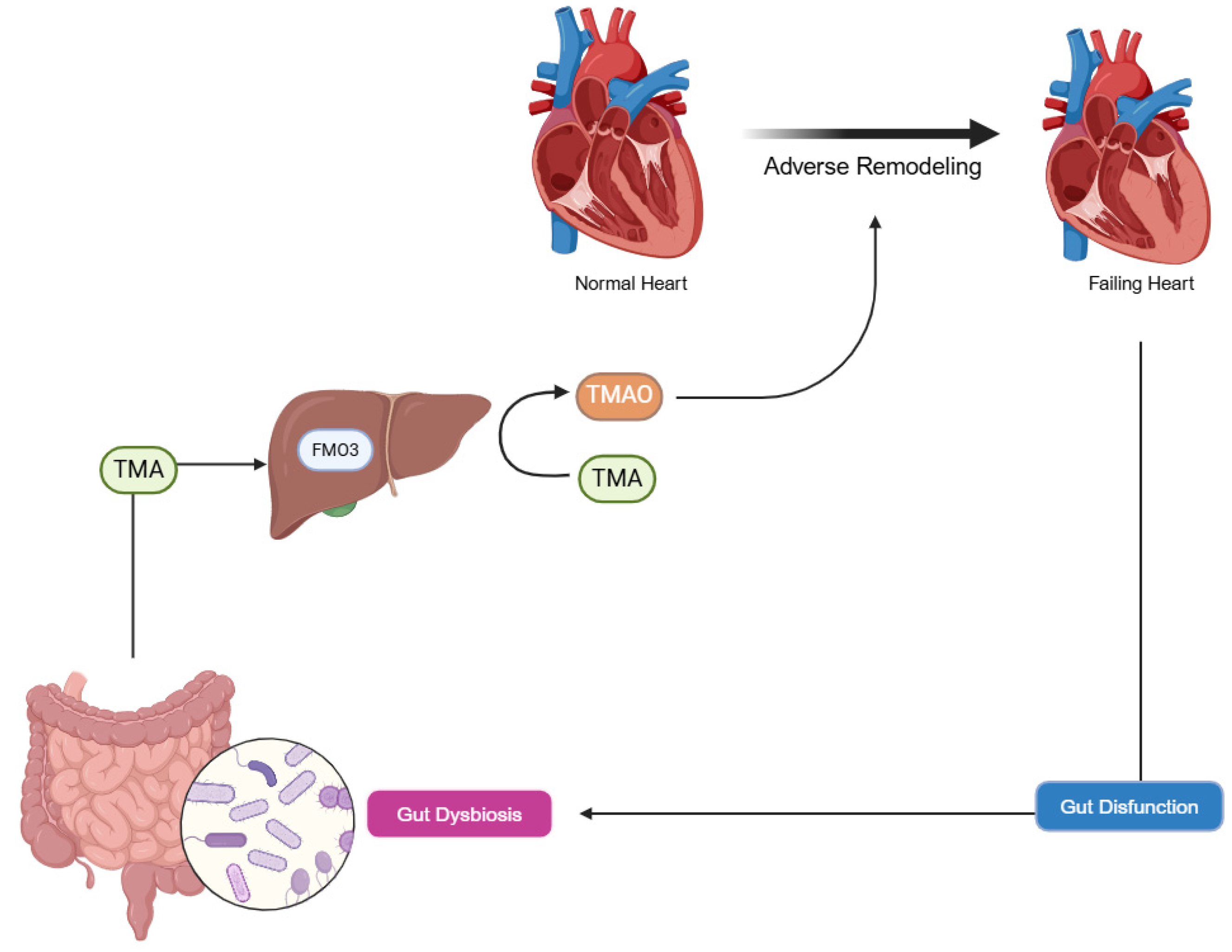

4. The Evolution of Omics in Heart Failure Research

4.1. Genomic Foundations and Environmental Interactions

4.2. Advances in Transcriptomics and Regulatory RNA Networks

4.3. Proteomic Insights and Post-Translational Modifications

4.4. Metabolomic Alterations and Cellular Energetics

5. Advanced Molecular Therapies

5.1. Stem Cell Therapy in Heart Failure

5.2. Genetic Modification in Heart Failure

| Therapy | Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Current Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Cell Therapy | ||||

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Derived from bone marrow or adipose tissue; delivered via intracoronary, intramyocardial, or intravenous routes; exert paracrine effects via cytokines (VEGF, HGF, IL-10). | Promotes angiogenesis, reduces inflammation and fibrosis; modest LVEF improvement (3.8% at 6 months) in post-MI HF [67]. | Poor cell retention (<10% survival at 30 days); minimal differentiation into cardiomyocytes (<1%); no mortality reduction [67,68,74]. | Clinical trials; experimental preconditioning with hypoxia or IGF-1 [67,75]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Reprogrammed somatic cells (fibroblasts) into cardiomyocytes; used in bioengineered cardiac patches [69]. | Scalable autologous production; significant LVEF increase (12% at 12 weeks) in porcine MI models with electrical integration [69]. | Risks of teratoma formation (5-10%) and arrhythmias (15%) due to electrical immaturity [70]. | Preclinical models; maturation strategies reducing arrhythmias by 50% [71]. |

| Cardiac Progenitor Cells (CPCs) | Isolated from human cardiac tissue; intramyocardial delivery of allogeneic cells [72]. | Tissue-specific repair; reduces LV end-systolic volume (-8.1 mL at 6 months) in chronic post-MI HF [72]. | No significant impact on major adverse events (death, hospitalization) at 12 months [72]. | Clinical trials. |

| Genetic Modification | ||||

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Targeted genome editing to correct mutations or silence genes; delivered via AAV9 or iPSCs [78]. | High precision; restores contractility (90% in vitro), reduces fibrosis (45%), improves LVEF (14%) in models [76,77,78]. | Off-target effects (4% in porcine trials); low delivery efficiency (15-25% of cardiomyocytes) [79]. | Preclinical; base/prime editing (95% precision) under evaluation [80]. |

| Zinc Finger Nucleases | Early genome-editing tool to correct TTN mutations or silence CTGF; delivered to iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes [81]. | Improves contractility (70% in vitro); reduces fibrosis (20%) in ischemic HF models [81,82]. | Labor-intensive design; less flexible than CRISPR [83]. | Limited use; largely superseded by CRISPR [81]. |

| TALENs & Meganucleases | Precision editing to overexpress VEGF-A or promote proliferation; delivered in murine models [84,85,86,87]. | Increases capillary density (35%) and LVEF (8%) in post-MI models; alternative to CRISPR [84]. | Complex design; limited scalability compared to newer tools [86]. | Preclinical |

| Viral Vectors (e.g., AAV9) | Non-integrative gene delivery of VEGF-A or SERCA2a; intracoronary or intramyocardial injection [88]. | Boosts angiogenesis (40% capillary density) and LVEF (11%) in porcine HF; robust expression [88]. | Limited cargo capacity (4.7 kb); pre-existing immunity in 50% of humans [89]. | Clinical trials (CUPID for SERCA2a); ongoing optimization [91]. |

| Synthetic mRNA | Transient gene expression (VEGF-A) via lipid nanoparticles; intramyocardial injection [92]. | Enhances capillary density (45%) and LVEF (11%) in mice; safe, no genomic integration [92,93,94]. | High cost, storage challenges; transient effect limits duration [93]. | Preclinical; adapted from mRNA vaccine technology [94]. |

| Transposons (e.g., PiggyBac) | Non-viral gene integration to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation [95]. | Versatile; enhances regeneration in murine models [97]. | Potential mutagenicity; less precise than CRISPR [96]. | Early preclinical; combined with stem cells [97]. |

| Synergistic Approaches | Combines stem cells with genetic editing (e.g., CRISPR-iPSCs with GATA4/TBX5, TALEN-MSCs with HGF) [93,94]. | High differentiation efficiency (92%); reduces apoptosis (35%), increases angiogenesis (40%) [93,94]. | Combines limitations of both approaches (e.g., retention, off-target effects) [93]. | Preclinical; advancing toward phase II/III trials by 2025 [95]. |

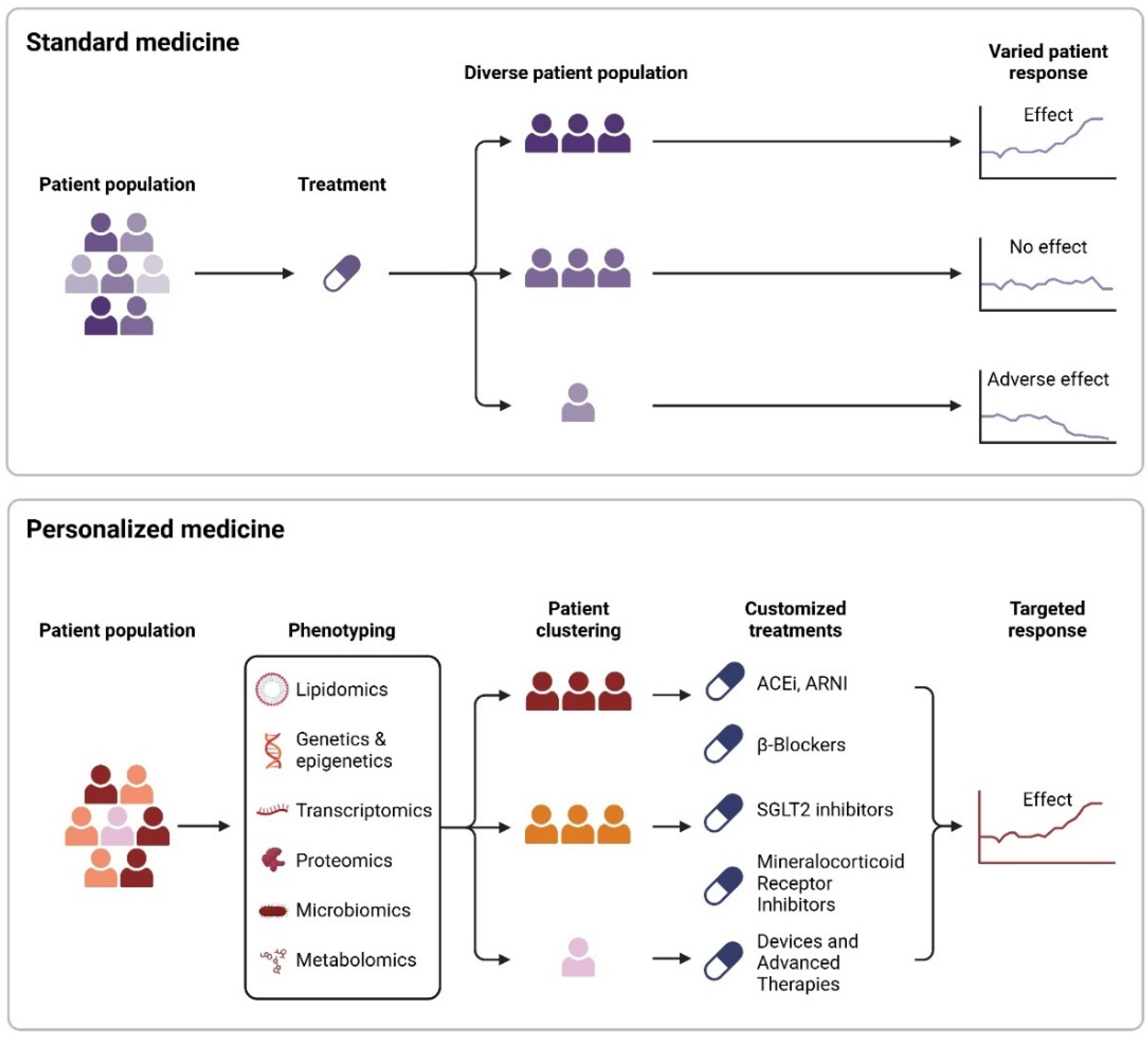

6. Personalized Medicine in Heart Failure

6.1. Therapeutic Interventions

7. Conclusions, Challenges and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| ACEIs | ACE inhibitors |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ARBs | Angiotensin II receptor blockers |

| ARNI | Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor |

| AT1 | Angiotensin II type 1 receptor |

| cGMP | Cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CPCs | Cardiac progenitor cells |

| CRISPR | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats |

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| DRP-1 | Dynamin-related protein-1 |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| ET-1 | Endothelin-1 |

| FMO | Flavin-containing monooxygenase |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFrEF | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| HFpEF | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor-1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| iPSCs | Induced pluripotent stem cells |

| lncRNAs | Long non-coding RNAs |

| LVEF | Left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MI | Myocardial infarction |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| RAAS | Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SGLT2i | Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors |

| SNS | Sympathetic nervous system |

| TALENs | Transcription activator-like effector nucleases |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine N-oxide |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VO₂ | Peak oxygen consumption |

| ZFNs | Zinc finger nucleases |

References

- McMurray, J.J.; Adamopoulos, S.; Anker, S.D.; Auricchio, A.; Böhm, M.; Dickstein, K.; Falk, V.; Filippatos, G.; Fonseca, C.; Gomez-Sanchez, M.A.; et al. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1787–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020, 141, e139–e596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart. 2007, 93, 1137–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, R.; Kario, K.; Inoue, T.; Kanai, H.; Ohashi, N.; Ito, H.; et al. Epidemiology of heart failure in Japan: A systematic review. J Cardiol. 2021, 77, 447–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchi, E.A.; Arias, A.; Verdejo, H.; Diez, M.; Gómez, E.; Castro, P. The Reality of Heart Failure in Latin America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013, 62, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.; Pinsky, J.L.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. The epidemiology of heart failure: The Framingham Study. Circ. 1993, 22, A6–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Albert, N.M.; Allen, L.A.; Bluemke, D.A.; Butler, J.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013, 6, 606–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.; Cole, G.; Asaria, P.; Jabbour, R.; Francis, D.P. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014, 171, 368–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, D.L. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: A combinatorial approach. Circulation 1999, 100, 999–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Xu, W.W.; Hu, S.J. Heart failure and the microbiome: A new frontier in cardiovascular disease. World J Cardiol. 2021, 13, 447–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, D.L. Innate immunity and the failing heart: the cytokine hypothesis revisited. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouleau, J.L.; Moyé, L.A.; de Champlain, J.; Klein, M.; Bichet, D.; Packer, M.; Sussex, B.; Arnold, J.; Sestier, F.; Parker, J.O.; et al. Activation of neurohumoral systems following acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1991, 68, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepoli, M.; et al. Contribution of muscle afferents to the hemodynamic, autonomic, and ventilatory responses to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: effects of physical training. Circulation 1996, 93, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoni, A.; Emdin, M.; Bramanti, F.; Iudice, G.; Francis, D.P.; Barsotti, A.; Piepoli, M.; Passino, C. Combined Increased Chemosensitivity to Hypoxia and Hypercapnia as a Prognosticator in Heart Failure. Circ. 2009, 53, 1975–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponikowski, P.P.; Chua, T.P.; Francis, D.P.; Capucci, A.; Coats, A.J.; Piepoli, M.F. Muscle Ergoreceptor Overactivity Reflects Deterioration in Clinical Status and Cardiorespiratory Reflex Control in Chronic Heart Failure. Circulation 2001, 104, 2324–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.N.; Levine, T.B.; Olivari, M.T.; Garberg, V.; Lura, D.; Francis, G.S.; Simon, A.B.; Rector, T. Plasma Norepinephrine as a Guide to Prognosis in Patients with Chronic Congestive Heart Failure. New Engl. J. Med. 1984, 311, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzau, V.J.; Colucci, W.S.; Hollenberg, N.K.; Williams, G.H. Relation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system to clinical state in congestive heart failure. Circulation 1981, 63, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, G.S.; Benedict, C.; E Johnstone, D.; Kirlin, P.C.; Nicklas, J.; Liang, C.S.; Kubo, S.H.; Rudin-Toretsky, E.; Yusuf, S. Comparison of neuroendocrine activation in patients with left ventricular dysfunction with and without congestive heart failure. A substudy of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). Circulation 1990, 82, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartupee, J.; Mann, D.L. Neurohormonal activation in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarius, C.F.; Millar, P.J.; Floras, J.S. Muscle sympathetic activity in resting and exercising humans with and without heart failure. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, M.H.; Aoi, W.; Henry, D.P. Direct effect of beta-adrenergic stimulation on renin release by the rat kidney slice in vitro. Circ. Res. 1975, 37, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekheirnia, M.R.; Schrier, R.W. Pathophysiology of water and sodium retention: edematous states with normal kidney function. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.M.; Mann, D.L. In search of new therapeutic targets and strategies for heart failure: recent advances in basic science. Lancet 2011, 378, 704–712. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, D.L.; Bristow, M.R. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biomechanical model and beyond. Circulation 2005, 111, 2837–2849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arai, M.; Alpert, N.R.; MacLennan, D.H.; Barton, P.; Periasamy, M. Alterations in sarcoplasmic reticulum gene expression in human heart failure. Circ. Res. 1993, 72, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenfuss, G.; Reinecke, H.; Studer, R.; Meyer, M.; Pieske, B.; Holtz, J.; Holubarsch, C.; Posival, H.; Just, H.; Drexler, H. Relation between myocardial function and expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ. Res. 1994, 75, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.W.; Hazen, S.L. The contributory role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 4204–4211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Kinross, J.; Burcelin, R.; Gibson, G.; Jia, W.; Pettersson, S. Host-Gut Microbiota Metabolic Interactions. Science 2012, 336, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trøseid, M.; Andersen, G.; Broch, K.; et al. The gut microbiome in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023, 81, 371–382. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, E.K.; Stagaman, K.; Dethlefsen, L.; et al. Diversity and stability of the human gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0233872. [Google Scholar]

- Brunkwall, L.; Orho-Melander, M. The gut microbiome in cardiovascular disease and health. Endocr Rev. 2023, 44, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.W.; Kitai, T.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1183–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeth, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Levison, B.S.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide and risk of atherosclerosis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023, 30, 892–900. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrestein, P.C.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Knight, R. Gut microbiome and host immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2020, 13, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, E.A.; Tillisch, K.; Gupta, A. Gut-brain axis and mental health. Microbiome Res. 2021, 14, 285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; et al. Gut microbiota in obesity and metabolic disorders. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2023, 33, 687–699. [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid, Y.; Hand, T.W. Role of the Microbiota in Immunity and Inflammation. Cell 2021, 184, 4168–4180. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Yao, M.; Lv, L.; et al. The gut microbiota's role in cardiovascular disease. Transl Res. 2020, 226, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, A.; Chiu, S.; Jenkins, N.; et al. Anesthesia and gut microbiota. Br J Anaesth. 2002, 89, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, S. Bacterial infections and diabetes. JCHF. 2015, 3, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An Obesity-Associated Gut Microbiome with Increased Capacity for Energy Harvest. Nature 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haiser, H.J.; Seim, K.L.; Balskus, E.P.; et al. Molecular basis for gut microbiome interactions with digoxin therapy. Science. 2013, 341, 295–298. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, K.A.; Martinez-Del Campo, A.; Kasahara, K.; et al. Metabolic, epigenetic, and transgenerational effects of gut microbiota. Sci China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Schugar, R.C.; Gliniak, C.M.; Osborn, L.J.; et al. Gut microbiota metabolism and cardiovascular disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e011347. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter, S.E.; O’Mara, M. Mechanisms of drug metabolism in heart failure patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, S.; Alden, N.; Lee, K. Metabolomics and cardiovascular disease. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Trøseid, M.; Ueland, T.; Hov, J.R.; Svardal, A.; Gregersen, I.; Dahl, C.P.; Aakhus, S.; Gude, E.; Bjørndal, B.; Halvorsen, B.; et al. Microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide is associated with disease severity and survival of patients with chronic heart failure. Am J Clin Nutr. 2022, 114, 571–580. [Google Scholar]

- Tebani, A.; Afonso, C.; Marret, S.; Bekri, S. Omics-Based Strategies in Precision Medicine: Toward a Paradigm Shift in Inborn Errors of Metabolism Investigations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Gill, R.; Lu, D.; Eres, I.; Lu, J.; Cui, J.; et al. Dissecting regulatory non-coding GWAS loci reveals fibroblast causal genes with pathophysiological relevance to heart failure.

- Gill, R.; Lu, D.; Eres, I.; Lu, J.; Cui, J.; Yu, Z.; et al. Dissecting regulatory non-coding heart disease GWAS loci with high-resolution 3D chromatin interactions reveals causal genes with pathophysiological relevance to heart failure.

- Aiyer, S.; Kalutskaya, E.; Agdamag, A.C.; Tang, W.H.W. Genetic Evaluation and Screening in Cardiomyopathies: Opportunities and Challenges for Personalized Medicine. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Feng, J.; Lan, W.; Shi, H.; Sun, W.; Sun, W. CircRNA and lncRNA-encoded peptide in diseases, an update review. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Spatial transcriptomics in development and disease. Mol. Biomed. 2023, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppe, C.; Flores, R.O.R.; Li, Z.; Hayat, S.; Levinson, R.T.; Liao, X.; Hannani, M.T.; Tanevski, J.; Wünnemann, F.; Nagai, J.S.; et al. Spatial multi-omic map of human myocardial infarction. Nature 2022, 608, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzau, V.J.; Hodgkinson, C.P. RNA Therapeutics for the Cardiovascular System. Circulation 2024, 149, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Myhre, P.L.; Arthur, V.; Dorbala, P.; Rasheed, H.; Buckley, L.F.; Claggett, B.; Liu, G.; Ma, J.; Nguyen, N.Q.; et al. Large scale plasma proteomics identifies novel proteins and protein networks associated with heart failure development. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K. Research progress on post-translational modification of proteins and cardiovascular diseases. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karpov, O.A.; Stotland, A.; Raedschelders, K.; Chazarin, B.; Ai, L.; Murray, C.I.; Van Eyk, J.E. Proteomics of the heart. Physiol. Rev. 2024, 104, 931–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wende, A.R.; Brahma, M.K.; McGinnis, G.R.; Young, M.E. Metabolic Origins of Heart Failure. JACC: Basic Transl. Sci. 2017, 2, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.M.; Neubauer, S.; Rider, O.J. Myocardial metabolism in heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2023, 20, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Huang, W.; Pan, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z. Intercellular Mitochondrial transfer: Therapeutic implications for energy metabolism in heart failure. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 211, 107555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tian, Q.; Guo, S.; Xie, D.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chu, H.; Qiu, S.; Tang, S.; Zhang, A. Metabolomics for Clinical Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Target Identification. Molecules 2024, 29, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopaschuk, G.D.; Karwi, Q.G.; Tian, R.; Wende, A.R.; Abel, E.D. Cardiac Energy Metabolism in Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1487–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomi, L.; Huang, Y.; Ohno-Machado, L. Privacy challenges and research opportunities for genomic data sharing. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, G.; Bitew, M. Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine: Synergy with Multi-Omics Data Generation, Main Hurdles, and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, M.R.; Samadani, U.; Han, R.; et al. Stem cell therapy for heart failure: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022, 79, 873–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.K.; Rhee, J.-W.; Wu, J.C. Adult stem cell therapy and heart failure, 2000 to 2016: A systematic review. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, T.; Miyagawa, S.; Fukushima, S.; et al. Cardiomyocyte maturation in human iPSC-derived cardiac tissue constructs. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 3525. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, J.J.H.; Yang, X.; Don, C.W.; Minami, E.; Liu, Y.W.; Weyers, J.J.; Mahoney, W.M.; Van Biber, B.; Cook, S.M.; Palpant, N.J.; et al. Human embryonic-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes regenerate non-human primate hearts. Nature 2014, 510, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bolli, R. Preconditioning of stem cells for cardiac repair: a new frontier. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2023, 174, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Makkar, R.R.; Kereiakes, D.J.; Aguirre, F.; et al. Allogeneic cardiosphere-derived cells for chronic ischemic heart failure: results of the ALLSTAR trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022, 79, 1445–56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; et al. Engineering 3D hydrogels for cardiac tissue repair: advances and challenges. Bioact Mater. 2023, 15, 123–34. [Google Scholar]

- Madonna, R.; Van Laake, L.W.; Davidson, S.M.; et al. Position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group Cellular Biology of the Heart: cell-based therapies for heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 1626–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mosqueira, D.; Mannhardt, I.; Bhagwan, J.R.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing in human iPSCs corrects MYH7 mutation and restores cardiomyocyte function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2022, 145, 927–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, E.; Lei, Y.H.; Shang, J.Y.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated correction of LMNA mutation attenuates fibrosis in dilated cardiomyopathy mice. Mol Ther. 2022, 30, 1834–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated TGF-β1 knockdown reduces myocardial fibrosis post-infarction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2023, 133, e165432. [Google Scholar]

- Musunuru, K.; Chadwick, A.C.; Mizoguchi, T.; et al. In vivo CRISPR editing for cardiovascular disease: promises and perils. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023, 20, 245–58. [Google Scholar]

- Anzalone, A.V.; Koblan, L.W.; Liu, D.R. Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 824–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maeder, M.L.; Thibodeau-Beganny, S.; Osiak, A.; Wright, D.A.; Anthony, R.M.; Eichtinger, M.; Jiang, T.; Foley, J.E.; Winfrey, R.J.; Townsend, J.A.; et al. Rapid “Open-Source” Engineering of Customized Zinc-Finger Nucleases for Highly Efficient Gene Modification. Mol. Cell 2008, 31, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. ZFN-mediated CTGF silencing attenuates fibrosis in ischemic heart failure models. Cardiovasc Res. 2019, 115, 1345–55. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, D. Genome engineering with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics 2011, 188, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, J.K.; Sander, J.D. TALENs: a widely applicable technology for targeted genome editing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 14, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Zhao, H.; Ren, X.; et al. TALEN-mediated VEGFA overexpression enhances angiogenesis in post-myocardial infarction mice. Circ Res. 2021, 129, 412–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove, A.J.; Voytas, D.F. TAL Effectors: Customizable Proteins for DNA Targeting. Science 2011, 333, 1843–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard, B.L. Homing Endonucleases: From Microbial Genetic Invaders to Reagents for Targeted DNA Modification. Structure 2011, 19, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Poirot, L.; Galetto, R.; Smith, J.; Montoya, G.; Duchateau, P.; Paques, F. Meganucleases and Other Tools for Targeted Genome Engineering: Perspectives and Challenges for Gene Therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 2011, 11, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilemann, L.; Ishikawa, K.; Weber, T.; Hajjar, R.J. Gene Therapy for Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2012, 110, 777–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacchigna, S.; Zentilin, L.; Giacca, M. Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors as Therapeutic and Investigational Tools in the Cardiovascular System. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1827–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlesworth, C.T.; Deshpande, P.S.; Dever, D.P.; et al. Identification of pre-existing adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. Nat Med. 2019, 25, 249–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Lentiviral vector platforms for gene therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019, 12, 245–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jessup, M.; Greenberg, B.; Mancini, D.; et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID): a phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2011, 124, 304–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zangi, L.; Lui, K.O.; von Gise, A.; et al. Modified mRNA directs the fate of heart progenitor cells in myocardial infarction models. Nat Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 898–907. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, U.; Karikó, K.; Türeci, Ö. mRNA-based therapeutics—Developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Porter, F.W.; et al. mRNA vaccines—a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 261–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yusa, K.; Zhou, L.; Li, M.A.; Bradley, A.; Craig, N.L. A hyperactive piggyBac transposase for mammalian applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivics, Z.; Izsvák, Z. Transposons for gene therapy! Curr Gene Ther. 2006, 6, 593–607. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific transposon-mediated gene delivery enhances cardiac repair in mice. Mol Ther. 2022, 30, 2134–45. [Google Scholar]

- Sena-Esteves, M.; Gao, G. Introducing Genes into Mammalian Cells: Viral Vectors. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020, 17, 431–438. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudelli, N.M.; Komor, A.C.; Rees, H.A.; et al. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017, 551, 464–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shiba, Y.; Gomibuchi, T.; Seto, T.; et al. CRISPR-enhanced iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes for cardiac tissue engineering. Sci Transl Med. 2023, 15, eabn4215. [Google Scholar]

- Knowlton, A.A.; Chen, L.; Malik, Z.A. Heart failure and mitochondrial dysfunction: The role of mitochondrial fission/fusion abnormalities and new therapeutic strategies. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2014, 63, 196–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bisaccia, G.; Ricci, F.; Gallina, S.; Di Baldassarre, A.; Ghinassi, B. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Heart Disease: Critical Appraisal of an Overlooked Association. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Rubattu, S.; Volpe, M. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Heart Failure: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwinger, R.H.G. Pathophysiology of heart failure. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah, H.N. Targeting the Mitochondria in Heart Failure: A Translational Perspective. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2020, 5, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsigkou, V.; Oikonomou, E.; Anastasiou, A.; Lampsas, S.; Zakynthinos, G.E.; Kalogeras, K.; Katsioupa, M.; Kapsali, M.; Kourampi, I.; Pesiridis, T.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications of Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients with Heart Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-H.; Fang, K.-F.; Lin, P.-H.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Huang, Y.-X.; Jie, H. Effect of sacubitril valsartan on cardiac function and endothelial function in patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2021, 77, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Bristow, M.R.; Cohn, J.N.; Colucci, W.S.; Fowler, M.B.; Gilbert, E.M.; Shusterman, N.H. The Effect of Carvedilol on Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. New Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolijn, D.; Pabel, S.; Tian, Y.; Lódi, M.; Herwig, M.; Carrizzo, A.; Zhazykbayeva, S.; Kovács, Á.; Fülöp, G.Á.; Falcão-Pires, I.; et al. Empagliflozin improves endothelial and cardiomyocyte function in human heart failure with preserved ejection fraction via reduced pro-inflammatory-oxidative pathways and protein kinase Gα oxidation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 117, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmazyn, M.; Gan, X.T. Probiotics as potential treatments to reduce myocardial remodelling and heart failure via the gut-heart axis: State-of-the-art review. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2023, 478, 2539–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).