1. Introduction

Communication competency, which refers to the ability to interact effectively with others through various communication methods, is considered one of the most essential skills in modern society (Lee et al., 2011; Son, 2016). Furthermore, communication between healthcare professionals and patients is a fundamental aspect of medical practice. Recent changes in the healthcare landscape, along with increasing public awareness and expectations regarding healthcare services, have expanded the roles of dental hygienists within dental institutions (Heo, 2014). Dental care presents unique challenges, including financial burden, dental phobia, and the necessity of patient cooperation, making patient communication a crucial factor (Kim, 2007). Effective communication is particularly important for dental hygienists in areas such as counseling, patient management, and oral health education (Kang et al., 2014). Among communication skills, empathic communication plays a crucial role in patient-centered care, as it helps establish trust between healthcare providers and patients (Howick et al., 2018). Studies have demonstrated that patient-centered communication enhances patient satisfaction and increases the likelihood of treatment adherence (Haribhai-Thompson et al., 2022; Kang et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011; Moon et al., 2014). Furthermore, communication competency in dental hygienists has been identified as influencing both organizational effectiveness and job satisfaction (Gwon & Han, 2015; Jeong, 2022; Lee & Kang, 2019).

Recognizing the significance of communication skills, the Korean Dental Hygienists Association and the Commission on Dental Accreditation of the American Dental Education Association emphasize them as a core competency for dental hygienists (Choi et al., 2015). As further evidence of its importance, communication is included in the Dental Middle Manager Job Competency Model (Moon & Lim, 2017). To meet these competency requirements, dental hygienists need to adopt effective communication strategies, which must be preceded by a comprehensive understanding of their own communication skills. Those strategies and skills need to be objectively measurable, to ensure systematic and accurate evaluations.

Given that communication interventions can have broad and generalized effects across different conditions, evaluating their impact on various outcomes within a consistent analytical framework is essential (Moon et al., 2014). Various communication competency scales have been developed and used across different healthcare professions (Hur, 2003; Kim & Oh, 2023; Nam-Kung & Kim, 2010). In dentistry, a scale has been developed to assess how patients perceive dental hygienists’ communication skills (Moon et al., 2014); however, the need remains for a self-assessment scale specifically designed to measure the communication competency of dental hygienists as they do their jobs (Kim & Jang, 2024). Higher patient-centered communication competency among dental hygienists is particularly important, as it can enhance self-efficacy, improve the quality of dental services, and ultimately increase job satisfaction. The Patient-Centered Communication Competency Scale (PCCS) for dental hygienists is essential for evaluating their communication competency, developing training programs to improve it, and conducting research on its relationship with various influencing factors. Against this backdrop, our study aimed to develop PCCS items based on empathic communication and then test their reliability and validity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Ethical Considerations

This study employed a methodological research design to test the reliability and validity of the PCCS in dental hygienists. To ensure ethical compliance, the study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and its protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dankook University (DKU_2022-10-041). All participants were informed of the study’s objectives and provided written informed consent before participation. The consent form outlined the study’s purpose, methodology, and key details concerning data anonymity, confidentiality, and the exclusive use of data for research purposes. Participants were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. Only those who provided consent were included in the survey.

2.2. Scale Development

The scale development process followed the framework proposed by DeVellis (2017), consisting of two key stages: (1) conducting a literature review and expert content validation to generate PCCS items for dental hygienists and (2) performing EFA and CFA to assess reliability and validity. This process followed these steps: clarifying measurement concepts, generating scale items, determining the scale structure, conducting content validity assessments, reviewing and refining items, applying the scale, evaluating its effectiveness, and optimizing it for implementation.

2.2.1. Conceptual Framework and Initial Item Generation

Communication competency is strongly emphasized as a core job skill for healthcare professionals (Heo, 2014), as provider-patient interactions—shaped by healthcare providers’ professionalism and their attitudes toward patients—play a crucial role in fostering patient trust, enhancing treatment effectiveness, and establishing and maintaining rapport (Park et al., 2000).

In this study, patient-centered communication is defined as a dental hygienist’s ability to perceive and manage patient care through verbal and nonverbal interactions. Communication competency encompasses not only grammatical knowledge but also pragmatic knowledge related to language use in various social contexts (Hymes, 1974). The key elements of patient-centered communication include: (1) empathic understanding, which involves recognizing and reflecting the patient’s emotions and perspectives; (2) open dialogue, which entails actively listening to patients and providing meaningful feedback; (3) information provision, which focuses on delivering explanations in a clear and accessible manner; (4) shared decision-making, which involves collaborating with patients to determine treatment options; and (5) trust-building, which aims to establish rapport to enhance treatment satisfaction.

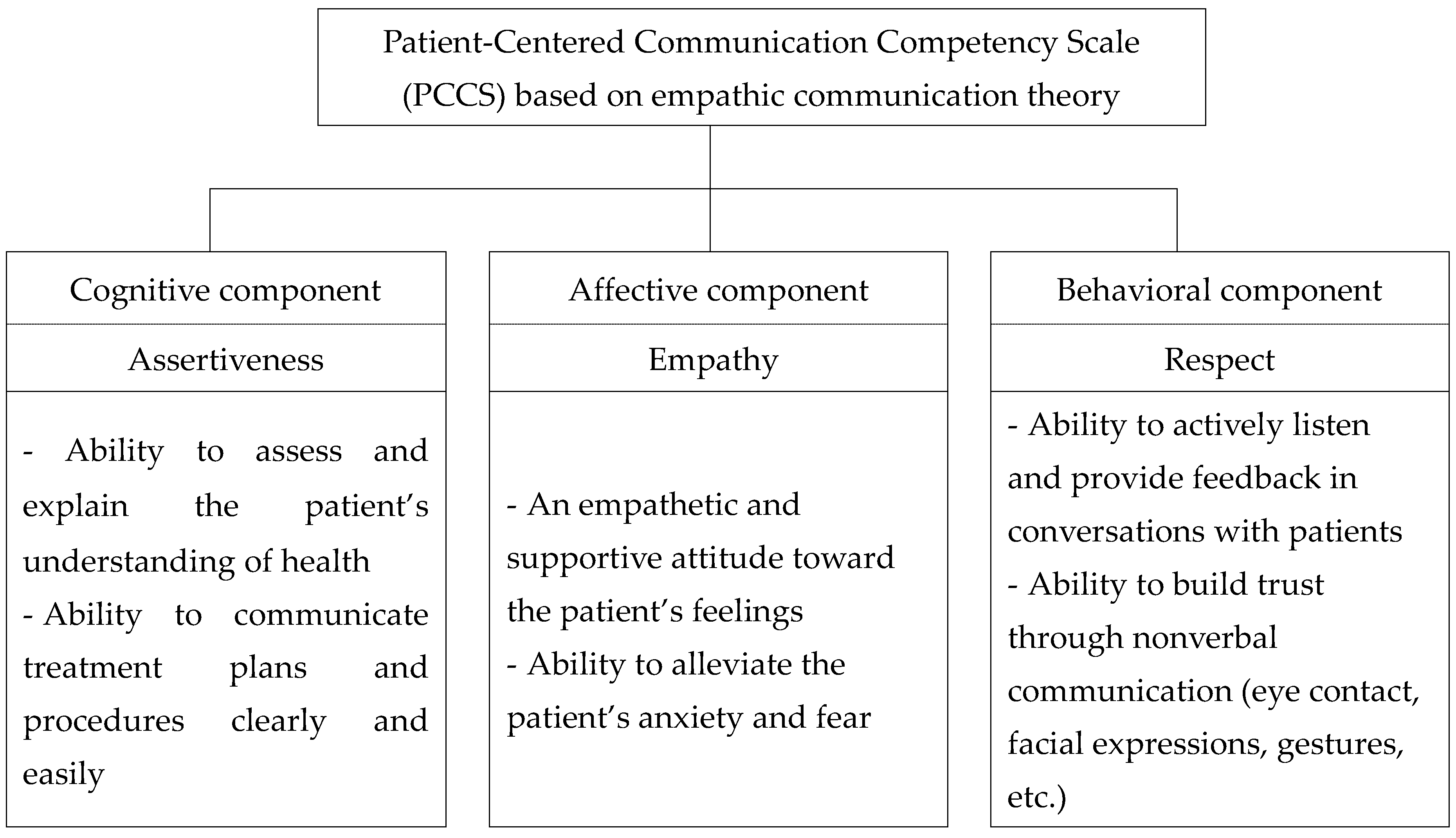

According to empathic communication theory, empathy plays a crucial role in healthcare by enabling providers to understand and appropriately respond to patients’ emotions, particularly those with dental anxiety (Haribhai-Thompson et al., 2022; Howick et al., 2018). This study builds on existing communication competency scales (Gwon & Han, 2015; Kim, 2021; Kim & Oh, 2023; Lee et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2011; Lee & Kang, 2019) and incorporates concepts from Rogers’ (1951) client-centered therapy to develop a comprehensive framework consisting of items structured into three domains, representing the cognitive, affective, and behavioral components of communication. The final items were designed to effectively assess communication competency in dental hygienists and were tested for validity and reliability (

Figure 1).

The PCCS is expected to be a valuable tool for assessing and improving communication skills in both dental hygienists and dentists (Moon et al., 2014). Unlike traditional information-based communication, patient-centered communication emphasizes respect for patients’ emotions, values, and needs, facilitating active patient participation in the treatment decision-making process.

To identify the initial scale items, a review of 196 domestic and international studies on communication competency published between 2013 and 2023 was conducted. Based on this review, 90 preliminary items were selected, drawing from the Communication Competency Scale for Medical Students developed by Nam-Kung and Kim (2010) and the Communication Competency Scale for Nurses developed by Kim (2021). These items were then refined and adapted for self-assessment by dental hygienists working in dental clinics and hospitals. To enhance validity and reliability, two experts reviewed and refined the wording of each item, finalizing the initial scale.

2.2.2. Content Validity

The content validity of the initial scale items was evaluated using a Delphi survey conducted with an expert panel comprising 10 professors and 8 dental hygienists holding a master’s degree or higher, all currently employed in dental clinics and hospitals. Content validity was measured using the content validity index for items (I-CVI), with each item rated on a 4-point scale (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 4 = highly relevant). The I-CVI for each item was determined by calculating the proportion of experts who assigned a rating of 3 or 4 (Kim, 2021).

A validity assessment was conducted using an I-CVI threshold of 0.80, as recommended by Ko and Hong (2022). Additionally, open-ended feedback from experts was incorporated to refine wording, eliminate redundant items, and remove items with low relevance. After three Delphi rounds, a final set of 38 items was selected, with an average I-CVI of 0.88.

2.2.3. Preliminary survey

A preliminary survey was conducted to assess readability, item comprehension, and potential errors in the questionnaire layout. Following Nunnally and Bernstein’s (1994) recommendation that a sample size of 20–50 is appropriate for a preliminary survey, 20 dental hygienists working in dental clinics and hospitals were randomly selected.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) dental hygienists working in clinics and hospitals who regularly communicate with patients and (2) those who understood the study’s purpose and voluntarily agreed to participate. The exclusion criteria were: (1) healthcare professionals who were not dental hygienists, (2) dental hygienists who did not engage in patient communication, and (3) respondents who completed less than 50% of the survey items.

Survey completion took approximately five minutes. All respondents indicated that the items were clear and easy to understand, necessitating no further modifications. The overall Cronbach’s α value was 0.922, confirming strong internal consistency.

2.3. Validity and Reliability

2.3.1. Participants

For participant selection, the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as in the preliminary survey were applied. The sample size was determined based on established guidelines, which recommend a minimum of 100 participants for EFA (Hair et al., 2010) and 10 to 20 times the number of factors for CFA (Arrindell & Van der Ende, 1985). Accordingly, a total of 400 participants were randomly selected, with 200 allocated to EFA and 200 to CFA.

2.3.2. Measurement

The PCCS for dental hygienists consisted of 38 items, finalized through a content validity assessment from an expert panel and a preliminary survey (

Table S1). Sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age, education, workplace, work experience, and current position.

Criterion validity was assessed using the 24-item Dental Hygienist Job Satisfaction Scale developed by Park (2020). Each item on this measure is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much), with higher scores indicating greater job satisfaction. Cronbach’s α for this instrument was 0.910 in Park’s (2020) study and 0.933 in this study.

Self-efficacy was measured using an eight-item scale originally developed by Chen et al. (2001) and adapted by Cho (2016). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much), with higher scores indicating greater self-efficacy. Cronbach’s α for this scale was 0.844 in Cho’s (2016) study and 0.904 in this study.

2.3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through an online survey conducted between March 27 and April 16, 2023. Fifty dental clinics and hospitals in South Korea were randomly selected. The survey included an information sheet detailing the study’s purpose, procedure, and estimated completion time. Of the 417 responses received, 17 were excluded due to incomplete or inconsistent answers, resulting in a final dataset of 400 responses (95.9%) for analysis.

2.3.4. Validity and Reliability Tests

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 23.0 and AMOS 23.0. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage. Normality was assessed based on skewness (< 2) and kurtosis (< 7) (Mishra et al., 2019). Normal distribution was confirmed for all items with skewness ranging from -0.263 to -0.981 and kurtosis from -0.387 to 1.51. Additionally, internal consistency was evaluated by examining item-total correlation coefficients, with values below 0.30 indicating low internal consistency within the scale (Lee et al., 2018), and all of the correlation coefficients were high.

Construct validity was assessed through EFA and CFA. EFA was conducted using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure, followed by principal component analysis with varimax rotation. Factors were retained based on eigenvalues greater than 1 and a cumulative variance explained of at least 50–60% (Hair et al., 2010). A factor loading threshold of 0.4 was applied (Field, 2013).

CFA evaluated model fit using absolute and incremental fit indices. Convergent validity was assessed by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE) and construct reliability (CR) (Heo, 2018). Model fit indices were interpreted based on the following criteria: for CFA model fit, a root mean residual (RMR) ≤ 0.05 was considered good, and a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.05 was classified as excellent, ≤ 0.08 as acceptable, and ≤ 0.10 as moderate (Song & Kim, 2012). Additionally, values ≥ 0.90 were considered very good and values ≥ 0.80 were deemed acceptable for goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and incremental fit index (IFI) (Choi & Yoo, 2017). Convergent validity was considered to have been established when the following criteria were met: standardized factor loadings ≥ 0.50, critical ratio ≥ 1.96 (p < 0.05), AVE ≥ 0.50, and CR ≥ 0.70 (Kim et al., 2020). Discriminant validity, which indicates that measures of different constructs exhibit low correlations, was assessed using correlation coefficients and the square root of the AVE (√AVE) (Cohen, 1992).

Criterion validity was examined by analyzing the correlations between the PCCS and measures of job satisfaction and self-efficacy. A correlation coefficient range of 0.40–0.80 was considered appropriate for criterion-related validation (DeVellis, 2017). Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s α.

2.4. Optimization of the PCCS

To optimize the PCCS with established validity and reliability, a professor of Korean language education was consulted to review the grammar, readability, and overall clarity of the finalized items. The review confirmed that the items were free of grammatical errors and were suitable for assessing the communication competency of dental hygienists, requiring no further modifications.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Participants

Regarding age and sex, the largest age group included participants in their 30s (n = 212, 53%), and the majority were female (n = 362, 90.5%). Most participants held associate degrees (n = 222, 55.5%), followed by bachelor’s degrees (n = 132, 33%) and master’s degrees or higher (n = 46, 11.5%). The most common workplace setting was private dental clinics (n = 300, 75.0%). Most participants worked as clinical dental hygienists (n = 257, 64.3%) (

Table 1).

3.2. Item Analysis

Item analysis was conducted using the mean and standard deviation of each item. With skewness ranging from -0.263 to -0.981 and kurtosis from -0.387 to 1.51, normality was confirmed for all items. The corrected item-total correlation coefficient for the developed scale ranged from 0.948 to 0.951. The overall Cronbach’s α value for the scale was 0.951, indicating strong internal consistency.

3.3. Construct Validity

3.3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

EFA was performed five times using eigenvalues as a criterion, with a factor loading threshold set at 0.4, as follows:

In the first EFA, the KMO coefficient was 0.86, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 3624.297, p < 0.001), with a cumulative variance explained of 60.30%. Seven items that exhibited double loadings on multiple factors and two items with factor loadings below 0.4 were removed, resulting in 29 retained items.

In the second EFA, the KMO coefficient was 0.91, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 2433.630, p < 0.001), with a cumulative variance explained of 61.05%. Five items that exhibited double loadings on multiple factors and one item with a communality value below 0.4 were removed, resulting in 23 retained items.

In the third EFA, the KMO coefficient was 0.90, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 1727.543, p < 0.001), with a cumulative variance explained of 60.96%. Five items that exhibited double loadings on multiple factors and one item with a factor loading below 0.4 were removed, resulting in 17 retained items.

In the fourth EFA, the KMO coefficient was 0.87, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 1113.588, p < 0.001), with a cumulative variance explained of 49.84%. Three items that exhibited double loadings on multiple factors and three items with a communality value below 0.4 were removed, resulting in 11 retained items.

In the fifth EFA, the KMO coefficient was 0.84, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 674.772, p < 0.001), with a cumulative variance explained of 60.51%. The final 11 items had communality values above 0.4, maximum factor loadings above 0.7, and no items with double loadings. The items were categorized into three factors (

Table 2).

The three final factors were reviewed and labeled as follows: Factor 1 – “Respect,” referring to listening, providing feedback, and building trust with patients; Factor 2 – “Assertiveness,” representing the process of clarifying communication for effective patient interactions; and Factor 3 – “Empathy,” reflecting the ability to understand patient expectations and perspectives, engage in discussion, and negotiate for relationship-oriented communication in healthcare.

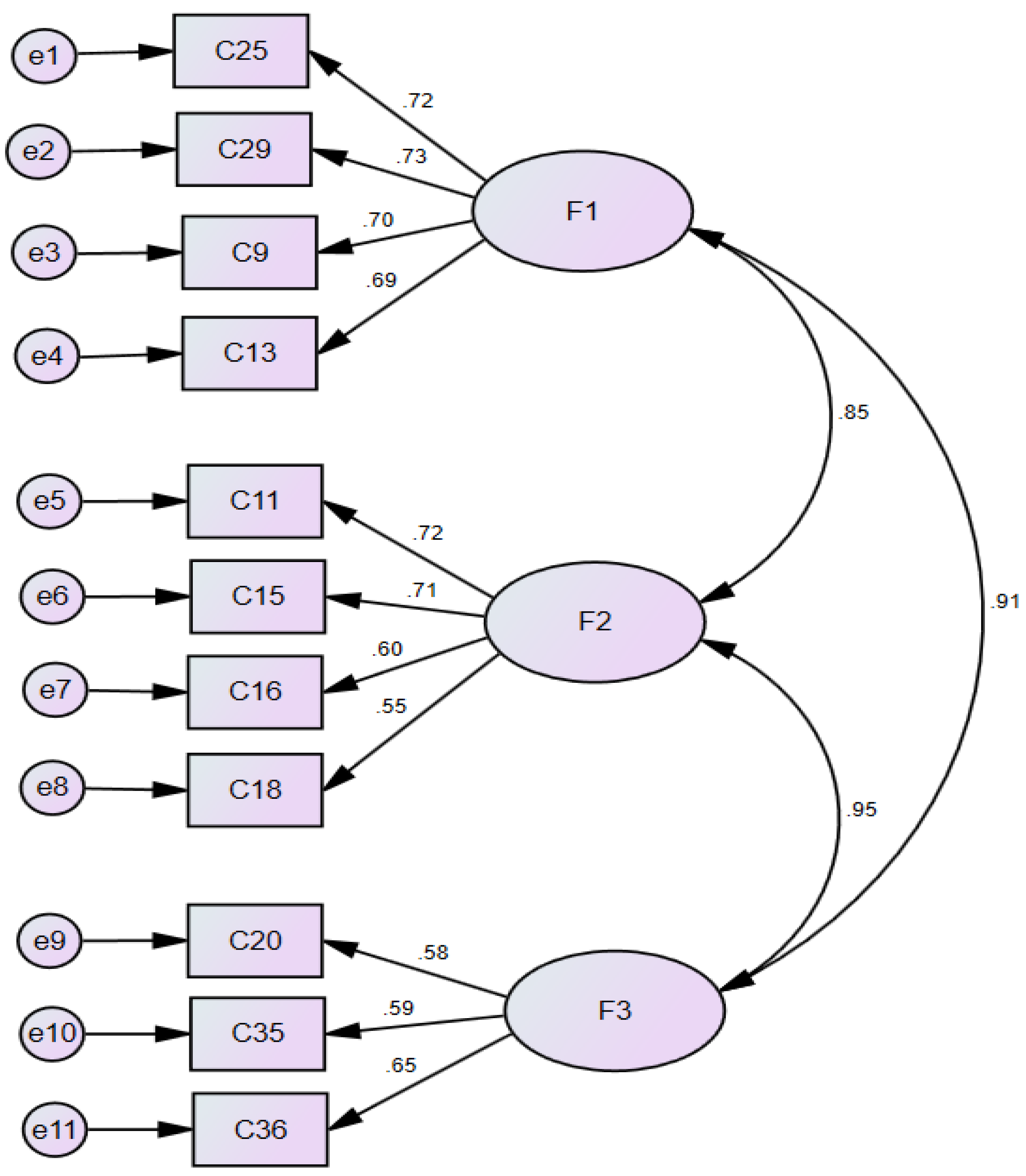

3.3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Validity (CFA)

In model fit assessment, while a significant chi-square test (χ² = 71.721, p < 0.05) may suggest a discrepancy between the model and observed data, the χ²/df ratio was 1.749, which falls within the acceptable range, indicating an adequate model fit. Other model fit indices also satisfied their respective thresholds: RMSEA = 0.061, TLI = 0.949, RMR = 0.027, GFI = 0.941, NFI = 0.911, RFI = 0.880, IFI = 0.960, and CFI = 0.959 (Choi & Yoo, 2010) (

Table 3).

For convergent validity, all standardized lambda (λ) values exceeded 0.50. AVE values were 0.533 for Assertiveness, 0.472 for Empathy, and 0.614 for Respect. CR values were 0.818 for Assertiveness, 0.728 for Empathy, and 0.864 for Respect, all meeting the convergent validity criteria (

Table 3 and

Figure 2).

For discriminant validity, all factor correlation coefficients ranged from 0.551 to 0.584, which were lower than the corresponding √AVE values (0.687–0.783), confirming that discriminant validity criteria were met (

Table 4).

3.4. Criteria Validity and Reliability of PCCS

The final PCCS items developed in this study are presented in

Table S2. To assess criterion validity, correlations between the PCCS and measures of self-efficacy and job satisfaction were examined using data from the full analysis set (n = 400) (

Table 5). The PCCS demonstrated strong positive correlations with both self-efficacy (r = 0.603) and job satisfaction (r = 0.624). Additionally, correlations between the PCCS subscales and their corresponding criterion measures were also positive, further supporting criterion validity.

The internal consistency of the PCCS, as measured by Cronbach’s α, was 0.862 for the overall scale, and, when broken down into subscales, 0.731 for Assertiveness, 0.701 for Empathy, and 0.771 for Respect, indicating satisfactory reliability (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to develop and validate the PCCS for dental hygienists. Toward that end, 38 assessment items were extracted from existing literature for scale development and categorized into cognitive, affective, and behavioral domains (Rogers, 1951). The scale components included factors such as effective communication and presentation skills, active listening and comprehension, and discussion and negotiation skills, which reflect self-expression, acceptance of others’ opinions, and interaction and coordination with others (Lee, 2019). Through five rounds of EFA, the final model was refined to include 11 PCCS items structured into three factors (subscales): Respect, Assertiveness, and Empathy. These 11 items encapsulate the essential competencies that dental hygienists should possess.

The PCCS represents a communication approach that respects patients’ values, preferences, and needs, thus encouraging their active participation in the decision-making regarding their health and treatment strategies. Rather than simply transmitting information, the PCCS emphasizes understanding patients’ emotions and expectations while fostering collaborative decision-making throughout the treatment process. The patient-dental hygienist relationship is grounded in human dignity, and within this interaction, empathic communication, based on person-centered care theory, plays a crucial role (Howick et al., 2018; Rogers, 1951).

Factor 1, Respect, refers to the ability to focus on a patient’s words, utilize verbal and nonverbal cues for understanding, and express acknowledgment and empathy toward their emotions and concerns. The corresponding items (n = 4) in the Respect subscale of the PCCS assess whether these skills are effectively conveyed. Notably, when healthcare providers use overly complex or lengthy explanations, patients may perceive it as a lack of respect. Therefore, providing information at a level the patient can understand and verifying the response fosters trust and conveys respect (Heo & Im, 2019; McCabe, 2004). The inclusion of the item “Encourage patients to express their emotions freely” under Respect is supported by previous research, which suggests that when dental hygienists establish trust as oral health professionals, they foster positive therapeutic relationships and facilitate effective communication (Lee et al., 2011).

Factor 2, Assertiveness, reflects dental hygienists’ ability to explain treatment processes and options clearly and comprehensibly, empowering patients to make informed decisions. The items of this subscale (n = 4) assess the ability to encourage patients’ proactive participation in developing treatment plans that align with their values and preferences. The item “Summarize key points throughout the conversation” aligns with previous research indicating that providing essential information, including potential risks and symptoms, can mitigate medical disputes and strengthen patient trust in healthcare providers (Moon et al., 2014).

Factor 3, Empathy, represents the ability of dental hygienists to recognize patients’ anxiety and fear, provide psychological reassurance, and maintain a supportive attitude throughout the treatment process. The items of this subscale (n = 3) assess communication strategies that help alleviate patient concerns and manage expectations. The inclusion of the item “Ask if the patient has any additional questions or concerns” aligns with prior research indicating that by acknowledging patient discomfort, dental hygienists can establish stronger trust-based relationships (Lee & Choi, 2012).

The PCCS developed in this study was validated through CFA, confirming model fit, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Criterion validity was supported by strong positive correlations between the PCCS and measures of job satisfaction and self-efficacy, and internal consistency was confirmed with Cronbach’s α of 0.862. These findings align with previous studies demonstrating the positive correlation between communication competence, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction (Jang, 2023; Kim et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2013). Despite the inherent overlap and conceptual ambiguity among communication components, the PCCS successfully achieved discriminant validity, which is a notable strength of this study. Therefore, the PCCS is expected to be a valuable tool for assessing the communication competency of dental hygienists.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The PCCS developed in this study was specifically designed for dental hygienists working in dental clinics and hospitals. Unlike existing tools, the PCCS captures the interactional outcomes of communication between dental hygienists and patients rather than focusing solely on individual communication skills (Moon et al., 2014). Additionally, the PCCS was developed as a concise 11-item scale that incorporates essential communication competencies for dental hygienists, making it both easy to understand and practical for use in clinical settings. The PCCS can serve as a foundational resource for research on improving communication skills in dental hygienists and can facilitate the development of training programs. The PCCS can also serve as an effective educational and assessment tool for further research aimed at developing training programs to enhance patient satisfaction and treatment adherence. Furthermore, the scale has the potential to contribute to structural equation modeling and theory validation studies related to communication skills in dental hygienists.

However, the generalizability of this study is limited, as it only included dental hygienists working in clinics and hospitals who directly communicate with patients. In particular, communication methods may vary when interacting with special populations, such as patients with disabilities, long-term care facility residents, or home-based oral care recipients (Heo & Im, 2019). Future research should consider developing additional communication competency scales that account for the diverse roles of dental hygienists and the specific needs of various patient populations.. Furthermore, intervention and longitudinal studies on how competency in patient-centered communication affects dental fear and anxiety would efficiently support the development of policies to improve patient-centered service in dental clinics and hospitals.

In summary, the PCCS is expected to contribute to the promotion of patient-centered care in dental practice and, ultimately, to the improvement of patients’ oral health.

5. Conclusions

The PCCS developed in this study consists of 11 items categorized into the Respect, Assertiveness, and Empathy subscales, with the reliability and content, construct and criterion validities successfully established. This tool is distinct from existing measures as it focuses on empathic interactions and relationship-building between dental hygienists and patients in clinical settings and can be used as a self-assessment tool. By utilizing the PCCS to enhance communication competency, dental hygienists may improve their job satisfaction and contribute to better patient care. As a concise and efficient tool, the PCCS is easy to administer and can be widely applied to various research studies on communication in dental hygiene practice. Furthermore, its applicability extends to training programs and performance assessments, supporting the development of patient-centered care models in dentistry.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Preliminary questions for developing a PCCS scale for dental hygienists.; Table S2: Final PCCS scale for dental hygienists.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-H.J.; methodology, J.-H.J.; software, D.-E.K.; validation, J.-H.J. and D.-E.K.; formal analysis, D.-E.K.; investigation, D.-E.K.; resources, D.-E.K.; data curation, D.-E.K. and J.-H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, D.-E.K. and J.-H.J.; writing—review and editing, J.-H.J. and D.-E.K.; visualization, J.-H.J.; supervision, J.-H.J.; project administration, J.-H.J.; funding acquisition, J.-H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the research fund of Dankook University in 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Dankook University (DKU: 2022-10-041).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVE |

average variance extracted |

| CFA |

confirmatory factor analysis |

| CFI |

comparative fit index |

| CR |

construct reliability |

| EFA |

exploratory factor analysis |

| GFI |

goodness-of-fit index |

| IFI |

incremental fit index |

| NFI |

normed fit index |

| PCCS |

Patient-Centered Communication Competency Scale |

| RMR |

root mean residual |

| RMSEA |

root mean square error of approximation |

| TLI |

Tucker-Lewis index |

References

- Arrindell, W. A., & Van der Ende, J. (1985). An empirical test of the utility of the observations-to-variables ratio in factor and components analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9(2),165-178.

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62-83. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H. J. (2016). A study of the effects of resilience factor on flight attendants' job performance and organizational effectiveness, Focused on the mediating effects of self-efficacy [Doctoral dissertation, Kyonggi University, Seoul, South Korea].

- Choi, C. H., & Yoo, Y.Y. (2017). The study on the comparative analysis of EFA and CFA. Journal of Digital Convergence, 15(10), 103-111. [CrossRef]

- Choi, D. S., Kim, S. H.,& Kim, J. S. (2015). A comparative analysis of competencies in American dental education association and American dental hygiene schools. Journal of Korean Society of Dental Hygiene, 15(3), 547-53. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J. A power primer. (1992). Psychological Bulletin. 112(1), 155-159. [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R. F. (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Field A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: And sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll. 4th ed. London, UK: Sage publications.

- Gwon, A. R., & Han, S. J. (2015). Effect of communication competence on the organizational effectiveness in dental hygienists, Journal of Korean society of Dental Hygiene, 15(6), 1009-1017. [CrossRef]

- Hair JR, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. 7th ed. Edinburgh Gate, Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Haribhai-Thompson, J., McBride-Henry, K., Hales, C., & Rook, H. (2022). Understanding of empathetic communication in acute hospital settings: A scoping review. BMJ Open, 12: e063375. [CrossRef]

- Heo, M. L. (2018). Development of the patient caring communication scale [Doctoral dissertation, Eulji University, Daejeon, South Korea].

- Heo, M. L., & Im, S. B. (2019). Development of the patient caring communication scale. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 49(1), 80-90. [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y. J. (2014). Doctor’s competency and empowerment measures desired by the state and society. Journal of the Korean Medical Association, 57(2), 121-7. [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. C. Y., Chai, H. H., Luo, B. W., Lo, E. C. M., Huang, M. Z., & Chu, C. H. (2025). An Overview of Dentist–Patient Communication in Quality Dental Care. Dentistry Journal, 13(1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Howick, J., Moscrop, A., Mebius, A., Fanshawe, T. R, Lewith, G., Bishop, F.L., Mistiaen, P., Roberts, N.W., Dieninytė, E., Hu, X.Y., Aveyard, P., & Onakpoya, I. J. (2018). Effects of empathic and positive communication in healthcare consultations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 111(7), 240–252. [CrossRef]

- Hur, G. H. (2003). Construction and validation of a global interpersonal communication competence scale. Korean Society for Journalism and Communication Studies, 47(6), 380-408.

- Hymes, D. (1974). Foundation in sociolinguistics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Jang, J. Y. (2023). The effect of nurses’ communication skills and self-efficacy on job satisfaction [Master’s Thesis, Changwon University, Gyeongsangnam-do, South Korea].

- Jeong, M. A. (2022). The study on effect of communication ability of dental hygienist on job satisfaction and turnover intention. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 22(8), 579-586. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. O., Kim, J. H., Hwang, J. M, Kwon, H. J., Seong, J. M., Lee, S. K., Kim, C. H., Kim, H.Y., Cho, Y. S., & Park, Y. D. (2010). Recognition about communication of dental personnels in dental clinics and hospitals in the capital. Journal of the Korean Academy of Oral Health, 34(3), 318-326.

- Kang, S. K., Bae, K. H., & Lim., S. R. (2014). Analysis of communication of dental hygienist in oral hygiene instruction during scaling. Journal of Dental Hygiene Science, 14(4), 546-553. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. J., Lee, S. Y., An, G. J., Lee, G. A., & Yun, H. J. (2019). Influence of communication competency and nursing work environment on job satisfaction in hospital nurses. Journal of Health Informatics and Statistics, 44(2):189-197. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J. (2021). Development and validation of a self-assessment tool for communication skills needed in nursing assessment [Doctoral dissertation, Eulji University, Daejeon, South Korea].

- Kim, H. J., Ha, J. H., & Jue, J. (2020). Compassion satisfaction and fatigue, emotional dissonance, and burnout in therapists in rehabilitation hospitals. Psychology, 11, 190-203. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., & Oh, H. Y. (2023). The Validity and Reliability of Nursing Assessment Communication-Competence Scale for Clinical Nurses. Journal of Korean Academy of Fundamentals of Nursing, 30(1), 78-89. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. E., Jang, J. H. (2024). Communication competency for dental hygienists in Korea: A scoping review. Journal of Korean society of Dental Hygiene, 12(5), 361-372. [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y. J., & Hong, G. R. (2022). Development and evaluation of nursing work environment scale of clinical nurses. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 28(5), 576-585. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. K., Yeo, J. Y., Jung, S. W., & Byun, S. S. (2013). Relations on Communication Competence, Job-stress and Job-satisfaction of Clinical Nurse. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 13(12):299-308. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. S., Eo, Y. S., & Lee, M. A. (2018), Development of job satisfaction scale for clinical nurses. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 48(1), 12-25. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. H. (2019). The sub-elements of communication competency as core competence reflected in the 2015 revised curriculum. Journal of Curriculum and Evaluation, 22(3):1-29. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., & Choi, J. M. (2012). A study on the relationship between patient's medical communication, reliance and satisfaction to dental hygienist. Journal of Korean society of Dental Hygiene, 12(5), 1017-1027. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., & Kang, Y. J. (2019). A study on factors affecting job satisfaction of dental hygienists. The Journal of the Korea Contents Association, 19(7), 478-488. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. K., Hwang, K. S., Park, Y. D., & Beom, K. C. (2011). The relationship between factors influencing smooth communication among dental workers. Journal of the Korean Academy of Oral Health, 35(1), 85-92.

- Lee, Y. H., Lee, Y. M., & Park. Y, G. (2011). Patients’ expectations of a good dentist: The views of communication. Korean Journal of Health Communication, 6(2), 89-104. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., Pandey, C. M., Singh, U., Gupta, A., Sahu, C., & Keshri, A. (2019). Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Annals of Cardiac Anaesthesia, 22(1): 67-72. [CrossRef]

- McCabe C. (2004). Nurse-patient communication: An exploration of patients’ experiences. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(1), 41-49. [CrossRef]

- Moon H. J., & Lim S.R. (2017). Development of a job competency model of a dental intermediary-manager using the Delphi method. Journal of Dental Hygiene Science, 17(2), 150-159. [CrossRef]

- Moon, H. J., Lee, S. Y., & Lim, S. R. (2014). Validity and reliability of the assessment tool for measuring communication skills of dental hygienist. Journal of dental hygiene science, 14(2):198-206.

- Namkung, J., & Kim, J. H. (2010). The developing and validation of communication ability scale. Korean Society for Creativity Education, 10(1), 85-109.

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed). New York: McGraw Hill.

- Park, J. H. (2020). Development of dental hygienists job satisfaction scale and path analysis of psychological ownership, job engagement, job performance [Doctoral dissertation, Namseoul University, Chungcheongnam-do, South Korea].

- Park, J. H., Sung, Y. H., Song, M. S., Cho, J. S., & Sim, W. H. (2000). The classification of standard nursing activities in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 30(6), 1411-1426. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Carl R. (1951). Client-centered therapy. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, pp. 560. [CrossRef]

- Song, T. M., & Kim, G. S. (2012). Structural equation modeling for health & welfare research: From beginner to advanced. Seoul: Hannarae academy.

- Son, Y. H. (2016). An exploratory study for development of tools to measure university students’ communication competence. Journal of Speech, Media & Communication Association, 15(1), 83-107.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).