Introduction

In 2017, approximately 109,500 individuals worldwide succumbed to opioid overdose. In the United States, opioid-related overdose fatalities reached 81,806 in 2022, highlighting the escalating public health crisis.[

1,

2] Globally, an estimated 40.5 million individuals were dependent on opioids as of 2017, with the United States reporting approximately 2.4 million individuals affected by active opioid use disorder in 2019.[

1,

3] These figures underscore the substantial burden of opioid dependence and the urgent need for effective prevention, treatment, and policy interventions to mitigate its impact.The relationship between opioids and spine surgery is complex, with significant implications for patient outcomes. Preoperative opioid use is notably common, with studies indicating that more than half of patients undergoing spine surgery report using opioids prior to their procedures.[

4,

5,

6] Chronic preoperative opioid use is associated with diminished postoperative outcomes, including reduced improvements in pain, function, and quality of life, higher rates of dissatisfaction, increased 90-day complications, and prolonged postoperative opioid dependence.[

4] Additionally, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons has noted that preoperative opioid use correlates with worse outcomes, such as greater early postoperative analgesic requirements and poorer long-term functional recovery.[

7] Patients with substantial preoperative opioid consumption also require higher opioid doses during the intraoperative and immediate postoperative periods, which complicates pain management, increases perioperative opioid demand, and may prolong hospital stays, further hindering recovery.[

4,

8]

Opioid-sparing pain management strategies for lumbar fusion (LF) surgery rely on multimodal analgesia (MMA) to optimize pain control while minimizing opioid consumption. MMA regimens incorporate acetaminophen, NSAIDs, gabapentinoids, and NMDA receptor antagonists (e.g., ketamine), which are endorsed by the American Society for Enhanced Recovery and the Society for Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement for their efficacy in reducing opioid requirements and enhancing analgesia.[

9,

10] Regional anesthesia techniques, particularly erector spinae plane (ESP) blocks, have demonstrated significant opioid-sparing effects and improved pain scores when performed surgically or under ultrasound guidance.[

11,

12] Additionally, continuous local anesthetic infusions, such as bupivacaine delivered via infusion pumps at the surgical site, have been associated with lower opioid consumption and superior immediate postoperative pain control.[

13] Collectively, these approaches offer a comprehensive framework for optimizing postoperative pain management while mitigating the risks associated with opioid use following LF surgery.

Despite growing concerns regarding opioid dependence in surgical settings, the literature remains limited on postoperative pain management outcomes specifically among opioid-dependent patients undergoing LF. Previous studies have often combined multiple spinal procedures, including both lumbar and cervical surgeries, thereby confounding direct comparisons. [

14] One notable study utilizing the National Inpatient Sample from 2003 to 2014 analyzed a cohort of 7,963 patients. [

15] Interestingly, despite our study spanning only six years of data, the number of opioid-dependent patients included in our cohort (n = 7,715) is remarkably comparable to that of the previous study. This underscores the rising postoperative opioid utilization following LF surgery. Understanding the causes and complications of LF in opioid versus non- opioid patients is crucial. While previous studies have highlighted the impact of opioid dependence on LF outcomes, our study aims to provide more up-to-date insights by utilizing data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) from 2016 to 2021. This research will perform a comparative analysis of LF procedures in these populations, examining epidemiology, etiology, patient characteristics, comorbidities, postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and hospitalization costs. By providing a comprehensive understanding of the differential outcomes associated with LF in these patient groups, the findings aim to inform clinical practices and improve patient management strategies.

Methods

2.1. Data Source

This study utilized the National Inpatient Sample (NIS), a comprehensive database developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) under the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database in the United States, systematically capturing approximately 20% of inpatient hospitalizations from HCUP-affiliated institutions. This dataset includes approximately 7 million unweighted admissions annually, enabling robust epidemiological analyses and national estimations when adjusted using the discharge sample weights provided by HCUP.

For this study, data from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2021, were analyzed, representing the most recent period available at the time of investigation. Each data entry in the dataset, termed a “case,” represents a weighted discharge record corresponding to approximately five actual patient encounters in the national inpatient population. This weighting methodology ensures accurate extrapolation to national estimates, enhancing the generalizability and statistical reliability of the findings.

2.2. Cohort Definition and Selection Criteria

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was queried for the period 2016–2021 to identify adult patients (aged >18 years) who underwent LF. Surgical cases were categorized based on the presence or absence of opioid dependence, utilizing ICD-10 codes. A total of 119,491 cases of reverse shoulder replacement surgery were identified, corresponding to 597,455 weighted patient encounters. Given the de-identified nature of the NIS database, the study was exempt from institutional review board (IRB) approval, and the requirement for informed consent was waived.

2.3. Outcome Variables (End Points)

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of opioid dependence on postoperative outcomes and complications following LF. Key outcome measures included inpatient mortality, length of stay (LOS), hospital charges, and inpatient postoperative complications. The complications assessed in this study included venous thromboembolism, encompassing deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), as well as surgical site infections, cardiac complications such as myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest, respiratory complications including pneumonia and respiratory failure, and renal and urinary complications such as acute renal failure and urinary tract infection (UTI).

For analytical purposes, continuous variables such as LOS and hospital charges were dichotomized. Patients whose LOS exceeded the 75th percentile were classified as having prolonged LOS, while those whose hospital charges surpassed the 75th percentile were categorized as having high-end hospital charges.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean value ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) when the normal distribution was met, if not, median with interquartile range (IQR) was used. Continuous variables were analyzed using the two-sample t-test or nonparametric Wilcoxon test, while statistical analysis for categorical variables was performed using the Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test. Prior to primary analysis, missing data was handled using single multivariate imputation by regression method. The percentage of missing data was low: age (0.17%), female sex (2.01%), total hospital charges (0.69%), with no missing data for other variables.

To minimize the impact of selection bias and potential confounding, we performed propensity score weighting using a generalized boosted model (GBM) for propensity score estimation. The propensity score model included demographics (age, sex), comorbidities (type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, chronic anemia, alcohol abuse, smoking status, chronic kidney disease, COPD), hospital characteristics (bed size, location/teaching status, region), and insurance type. The sampling weights from the original dataset were incorporated into the propensity score estimation. Balance between weighted groups was assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD), with values <0.1 indicating good balance. Survey-weighted generalized linear models were used to estimate the effects of opioid use on various postoperative outcomes, accounting for the propensity score weights. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.1, with two-tailed statistical tests and an alpha level of ≤0.05 considered statistically significant.

2.5. Ethical Consideration

The study was granted exempt status by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) due to the de-identified nature of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) dataset, ensuring full compliance with ethical guidelines for human subject research. Artificial intelligence (AI) tools were utilized solely to enhance linguistic clarity, grammatical accuracy, and stylistic refinement of the manuscript. These tools were not employed for data analysis, statistical interpretation, or content generation, thereby preserving the scientific integrity and methodological rigor of the study.

Table 1.

ICD-10 and Procedure Codes Used for Case Selection and Variable Definition.

Table 1.

ICD-10 and Procedure Codes Used for Case Selection and Variable Definition.

| Category |

Variable |

Codes |

| Lumbar Fusion Procedures |

Lumbar Fusion |

0SG0070, 0SG0071, 0G007J |

| |

|

0SG00A0, 0SG00AJ, 0SG00J0 |

| |

0SG00J1, 0SG00JJ, 0SG00K0 |

| |

0SG00K1, 0SG0370, 0SG0371 |

| |

0SG037J, 0SG03A0, 0SG03AJ |

| |

0SG03J0, 0SG03J1, 0SG03K0 |

| |

0SG03K1, 0SG03KJ, 0SG0471 |

| Comorbidities |

Opioid Dependence |

F11.2x |

| |

Type 2 Diabetes |

E11.x |

| |

Hypertension |

I10 |

| Dyslipidemia |

E78.x |

| Sleep Apnea |

G47.3x |

| Anemia |

D64.x |

| Alcohol Abuse |

F10.x |

| Smoking |

Z72.0 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease |

N18.x |

| COPD |

J44.x |

| Complications |

Surgical Site Infection |

T81.4x |

| |

Urinary Tract Infection |

N39.x |

| Respiratory Complications |

J96.x, J95.x, J80.x, J15.x, J18.x |

| Dural Tear/CSF Leak/Nerve Root Injury |

G96.11, G96.00, G96.02, S34.x |

| Acute Renal Failure |

N17.x |

| Embolism (PE, DVT) |

I26.x, I82.4x |

| Blood Loss |

D62.x |

| Cardiac Complications |

I44.x, I20.x, I49.x, I50.x, I51.x, I23.x, R96.x, I21.x, I22.x, I24.x, I46.x, T81.1 |

| Stroke |

I63.x, G45.x |

| |

|

Results

Among 597,455 patients who underwent spinal surgery, 7,715 (1.3%) had documented opioid dependence.

Table 2 presents that opioid-dependent patients were significantly younger (mean age 58.2 vs 62.2 years, p<.001) and received care in different hospital settings compared to non-dependent patients. Notably, opioid-dependent patients were more likely to be treated at large hospitals (63.6% vs 47.2%, p<.001) and urban teaching facilities (80.2% vs 73.4%, p<.001). There were also marked regional differences, with opioid-dependent patients having higher representation in the West (29.6% vs 18.7%) and Midwest (27.3% vs 23.9%) but lower in the South (31.7% vs 41.2%, p<.001 for regional distribution). Insurance coverage patterns differed significantly between groups (p<.001). While Medicare was the primary payer for both groups (50.4% opioid-dependent vs 48.9% non-dependent), opioid-dependent patients had notably higher Medicaid utilization (12.8% vs 5.8%) and lower private insurance coverage (29.5% vs 37.9%).

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics and Hospital Charges by Opioid Use.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics and Hospital Charges by Opioid Use.

| Characteristic |

Not Opioid Dependent

n=589,740 |

Opioid Dependent

n=7,715 |

P value |

| Demographics |

|

|

|

| Age, mean (SD) |

62.16 (12.09) |

58.23 (11.36) |

<.001 |

| Female, n (%) |

331,750 (56.3) |

4,450 (57.7) |

.25 |

| Hospital Bed Size, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Small |

162,105 (27.5) |

1,165 (15.1) |

<.001 |

| Medium |

149,380 (25.3) |

1,645 (21.3) |

<.001 |

| Large |

278,255 (47.2) |

4,905 (63.6) |

<.001 |

| Hospital Location/Teaching, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Rural |

23,100 (3.9) |

305 (4.0) |

<.001 |

| Urban non-teaching |

133,695 (22.7) |

1,220 (15.8) |

<.001 |

| Urban Teaching |

432,945 (73.4) |

6,190 (80.2) |

<.001 |

| Hospital Region, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Northeast |

95,440 (16.2) |

880 (11.4) |

<.001 |

| Midwest |

140,800 (23.9) |

2,110 (27.3) |

<.001 |

| South |

242,980 (41.2) |

2,445 (31.7) |

<.001 |

| West |

110,520 (18.7) |

2,280 (29.6) |

<.001 |

| Race, n (%) |

|

|

|

| White |

471,060 (79.9) |

6,225 (80.7) |

.008 |

| Black |

47,125 (8.0) |

650 (8.4) |

.008 |

| Hispanic |

31,300 (5.3) |

415 (5.4) |

.008 |

| Asian |

7,295 (1.2) |

15 (0.2) |

.008 |

| Other |

32,960 (5.6) |

410 (5.3) |

.008 |

| Primary Payer, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Medicare |

288,315 (48.9) |

3,885 (50.4) |

<.001 |

| Medicaid |

34,490 (5.8) |

990 (12.8) |

<.001 |

| Private |

223,510 (37.9) |

2,275 (29.5) |

<.001 |

| Other |

43,425 (7.4) |

565 (7.3) |

<.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Type 2 Diabetes |

129,170 (21.9) |

1,715 (22.2) |

.75 |

| Hypertension |

314,400 (53.3) |

4,045 (52.4) |

.49 |

| Dyslipidemia |

247,720 (42.0) |

3,030 (39.3) |

.02 |

| Sleep Apnea |

95,790 (16.2) |

1,455 (18.9) |

.005 |

| Chronic Anemia |

27,720 (4.7) |

475 (6.2) |

.01 |

| Alcohol Abuse |

6,085 (1.0) |

265 (3.4) |

<.001 |

| Smoker |

4,220 (0.7) |

60 (0.8) |

.77 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease |

36,770 (6.2) |

595 (7.7) |

.02 |

| COPD |

43,690 (7.4) |

985 (12.8) |

<.001 |

The comorbidity profile revealed several significant differences. Opioid-dependent patients had markedly higher rates of alcohol abuse (3.4% vs 1.0%, p<.001) and COPD (12.8% vs 7.4%, p<.001). They also demonstrated higher prevalence of sleep apnea (18.9% vs 16.2%, p=.005), chronic anemia (6.2% vs 4.7%, p=.01), and chronic kidney disease (7.7% vs 6.2%, p=.02). Interestingly, traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension (52.4% vs 53.3%, p=.49) and type 2 diabetes (22.2% vs 21.9%, p=.75) showed similar prevalence between groups, while dyslipidemia was actually lower in the opioid-dependent group (39.3% vs 42.0%, p=.02).

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics After Propensity Score Weighting.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics After Propensity Score Weighting.

| Characteristic |

Overall |

Not Opioid Dependentn=7,715 |

Opioid Dependentn=7,715 |

P value |

| Age, mean (SD) |

61.88 (11.83) |

62.11 (12.08) |

61.62 (11.54) |

.20 |

| Female, (%) |

55.7 |

56.3 |

55.0 |

.45 |

| DM type 2, (%) |

22.2 |

21.9 |

22.5 |

.65 |

| Hypertension, (%) |

53.3 |

53.3 |

53.3 |

.98 |

| Dyslipidemia, (%) |

42.7 |

42.0 |

43.5 |

.33 |

| Sleep apnea, (%) |

16.2 |

16.3 |

16.2 |

.92 |

| Anemia, (%) |

4.6 |

4.7 |

4.4 |

.66 |

| Alcohol abuse, (%) |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.2 |

.60 |

| Smoking, (%) |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

.93 |

| Renal disease, (%) |

6.2 |

6.3 |

6.1 |

.85 |

| Lung disease, (%) |

7.8 |

7.5 |

8.1 |

.40 |

| Hospital Size, (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Small |

27.2 |

27.3 |

27.0 |

.88 |

| Medium |

24.9 |

25.3 |

24.5 |

|

| Large |

47.9 |

47.4 |

48.5 |

|

| Hospital Type, (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Rural |

4.3 |

3.9 |

4.7 |

.71 |

| Urban non-teaching |

22.2 |

22.6 |

21.8 |

|

| Urban teaching |

73.5 |

73.5 |

73.5 |

|

| Region, n(%) |

|

|

|

|

| Northeast |

15.8 |

16.1 |

15.4 |

.62 |

| Midwest |

23.0 |

23.9 |

21.9 |

|

| South |

41.6 |

41.1 |

42.2 |

|

| West |

19.6 |

18.9 |

20.5 |

|

| Insurance, (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Medicare |

48.2 |

48.9 |

47.4 |

.73 |

| Medicaid |

6.0 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

|

| Private |

38.2 |

37.8 |

38.6 |

|

| Other |

7.6 |

7.4 |

7.9 |

|

Propensity-weighted cohort analysis revealed considerable variation in overall complication rates, with blood loss being the most frequent adverse event (17.8%), followed by cardiac complications (5.3%), respiratory complications (3%), acute renal failure (2.8%), and urinary tract infections (2.6%). Less common complications included dural tears (0.9%), surgical site infections (0.2%), and stroke (0.2%).

When comparing groups, opioid-dependent patients demonstrated significantly higher rates of certain postoperative complications compared to non-dependent patients. Most notably, blood loss complications were substantially more frequent in the opioid-dependent group (20.5% vs 15.0%). Similarly, respiratory complications occurred at a higher rate among opioid-dependent patients (3.8% vs 2.3%).

Hospital resource utilization also differed between the groups. Opioid-dependent patients had significantly longer lengths of stay (mean 4.04 ± 3.50 days vs 3.41 ± 2.47 days), and showed a trend toward higher total hospital charges ($154,263 ± $121,227 vs $141,971 ± $104,409).

Other complications occurred at similar rates between the groups, including surgical site infections (0.3% vs 0.1%), urinary tract infections (2.7% vs 2.5%), dural tears (1.2% vs 0.6%), acute renal failure (2.9% vs 2.7%), cardiac complications (5.8% vs 4.7%), and stroke (0.2% vs 0.1%). In-hospital mortality was rare in both groups (0.06% vs 0.19%).

Results of Propensity Score Weight (PSW)

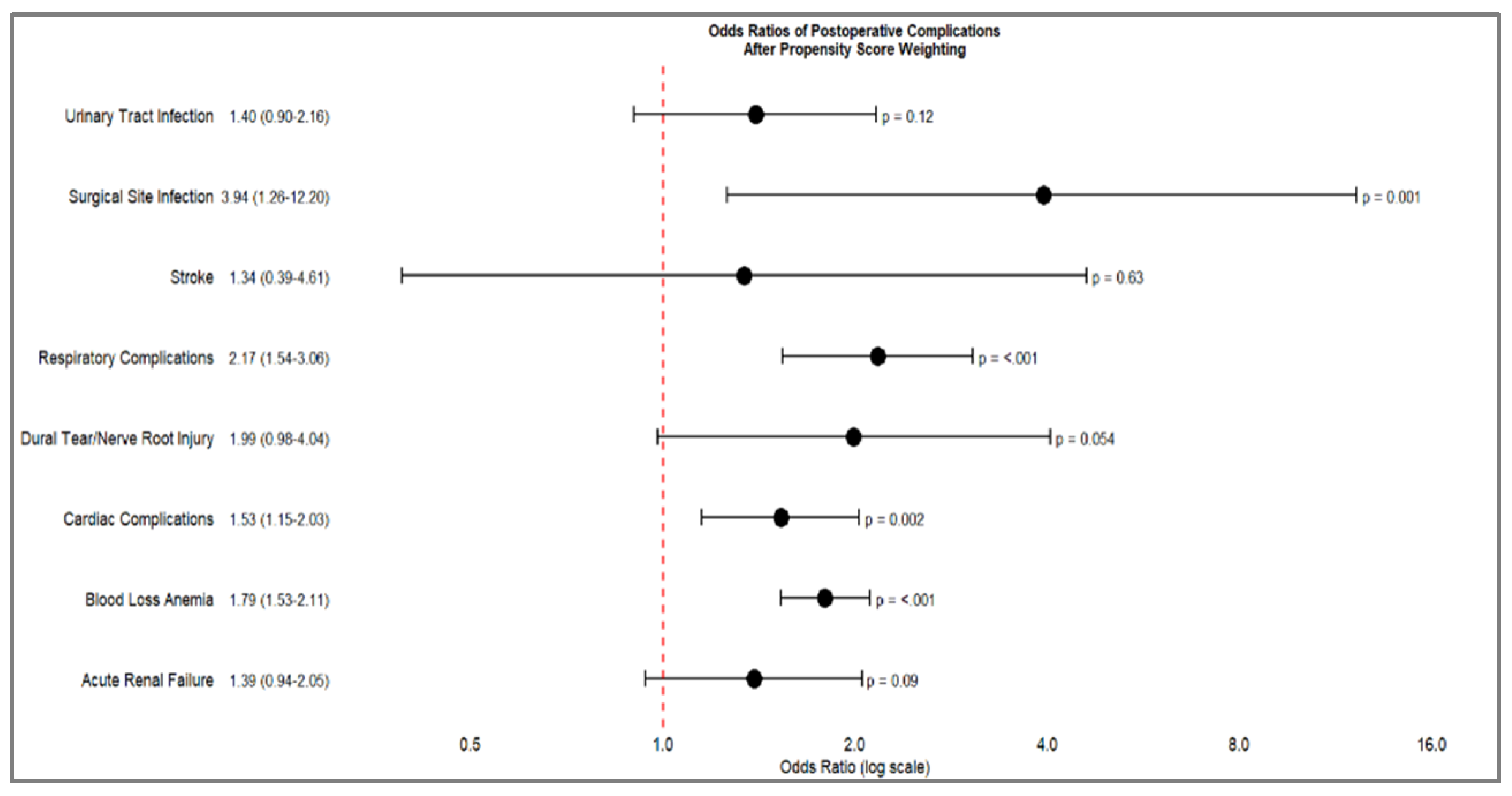

After propensity score weighting (PSW), the results detailed in

Table 5 demonstrate significant differences in postoperative complications between opioid-dependent and non-dependent patients. Blood loss anemia remained the most pronounced complication, with a substantially increased odds ratio (OR 1.79, 95% CI 1.53-2.11, p<.001). Respiratory complications also showed a marked increase (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.54-3.06, p<.001), along with surgical site infections (OR 3.94, 95% CI 1.26-12.2, p=.001) and cardiac complications (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.15-2.03, p=.002).

Table 4.

Postoperative Complications and Hospital Outcomes by Opioid Use Status before PSW.

Table 4.

Postoperative Complications and Hospital Outcomes by Opioid Use Status before PSW.

| Complications |

ES |

Estimate |

Lower CI |

Upper CI |

P-value |

| Stroke |

OR |

1.51 |

0.48 |

4.74 |

.48 |

| Blood Loss Anemia |

OR |

1.84 |

1.62 |

2.08 |

<.001 |

| Cardiac Complications |

OR |

1.32 |

1.07 |

1.64 |

.01 |

| Acute Renal Failure |

OR |

1.36 |

1.00 |

1.84 |

.04 |

| Dural Tear/Nerve Root Injury |

OR |

2.21 |

1.40 |

3.49 |

<.001 |

| Respiratory Complications |

OR |

2.10 |

1.61 |

2.73 |

<.001 |

| Urinary Tract Infection |

OR |

1.49 |

1.09 |

2.03 |

.01 |

| Surgical Site Infection |

OR |

3.27 |

1.34 |

8.02 |

.009 |

| Hospital Outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

| Total charges$

|

MD |

21,779.05 |

15,679.70 |

27,878.40 |

<.001 |

| Length of stay |

MD |

0.94 |

0.76 |

1.11 |

<.001 |

Table 5.

Postoperative Complications and Hospital Outcomes by Opioid Use Status after PSW.

Table 5.

Postoperative Complications and Hospital Outcomes by Opioid Use Status after PSW.

| Complications |

(%) |

Effect |

Estimate |

Lower CI |

Upper CI |

P-value |

| Urinary Tract Infection |

2.6 |

OR |

1.40 |

0.90 |

2.16 |

.12 |

| Stroke |

17.8 |

OR |

1.34 |

0.39 |

4.61 |

.63 |

| Surgical Site Infection |

0.2 |

OR |

3.94 |

1.26 |

12.2 |

.001 |

| Blood Loss Anemia |

17.8 |

OR |

1.79 |

1.53 |

2.11 |

<.001 |

| Cardiac Complications |

5.3 |

OR |

1.53 |

1.15 |

2.03 |

.002 |

| Acute Renal Failure |

2.8 |

OR |

1.39 |

0.94 |

2.05 |

.09 |

| Dural Tear/Nerve Root Injury |

0.9 |

OR |

1.99 |

0.98 |

4.04 |

0.054 |

| Respiratory Complications |

3 |

OR |

2.17 |

1.54 |

3.06 |

<.001 |

| Hospital Outcomes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total charges$

|

|

MD |

17,739.2 |

10791.26 |

24687.15 |

<.001 |

| Length of stay |

|

MD |

0.83 |

0.58 |

1.08 |

<.001 |

Hospital outcomes continued to reflect these differences, with opioid-dependent patients experiencing significantly higher total hospital charges (mean difference $17,739.2, 95% CI $10,791.26-$24,687.15, p<.001) and slightly longer lengths of stay (mean difference 0.83 days, 95% CI 0.58-1.08, p<.001).

Some complications showed less pronounced or non-significant differences after PSW, including urinary tract infections (OR 1.40, p=.12), acute renal failure (OR 1.39, p=.09), dural tear/nerve root injury (OR 1.99, p=.054), and stroke (OR 1.34, p=.63). These findings, presented in

Table 4, suggest that while propensity score weighting attenuated some of the differences observed in the initial analysis, significant disparities in postoperative outcomes between opioid-dependent and non-dependent patients persisted.

Figure 1.

Forest Plot of Odds Ratio of Postoperative complications after Propensity Score Weighting.

Figure 1.

Forest Plot of Odds Ratio of Postoperative complications after Propensity Score Weighting.

Discussion

In this large, national cohort study of 597,455 patients undergoing spinal surgery, opioid dependence was associated with distinct demographic, clinical, and perioperative characteristics that influenced postoperative outcomes. Opioid-dependent patients were significantly younger and more likely to be treated in large, urban teaching hospitals, with a notable geographic concentration in the West and Midwest regions. These patients exhibited a distinct comorbidity profile, with higher rates of alcohol abuse, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sleep apnea, chronic anemia, and chronic kidney disease, while traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes were comparably prevalent between groups. Propensity-adjusted analyses confirmed that opioid dependence was an independent risk factor for increased postoperative complications, particularly blood loss anemia, respiratory complications, surgical site infections, and cardiac events. Moreover, opioid-dependent patients demonstrated prolonged hospital stays and higher healthcare costs, reinforcing the economic burden associated with opioid-related morbidity in surgical populations. While some complications, such as urinary tract infections and acute renal failure, showed attenuated differences after adjustment, the overall trend suggests that opioid dependence is a significant determinant of adverse perioperative outcomes.

Opioid dependence, recognized as a public health epidemic, has been the subject of extensive research and institutional guidelines (13,15,16,21,22). Its impact on surgical outcomes has been examined across multiple disciplines (9,10,14,23). While prior studies have suggested a correlation between opioid dependence and adverse surgical outcomes, many were limited by small cohort sizes or have become outdated (9,10,24,12). One study reported an increasing prevalence of opioid dependence among lumbar fusion patients, identifying higher postoperative complication rates and prolonged hospital stays. (20) Their study utilized the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2003 to 2014, relying on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). In contrast, our study leverages the Tenth Revision (ICD-10-CM), which provides more precise and comprehensive coding for diagnoses and procedures, allowing for a more accurate assessment of contemporary trends in opioid dependence among lumbar fusion patients.

Opioid use trends have evolved significantly in recent years. Studies examining opioid prescriptions from 2016 to 2021 indicate a notable reduction in opioid prescriptions and a decline in the prevalence of chronic opioid users (25,26). However, another study reported a simultaneous increase in nonfatal opioid-involved overdoses, highlighting the complex and multifaceted nature of opioid use trends. (27) Given these findings, the impact of opioid dependence on lumbar fusion patients requires further investigation to determine whether evolving prescribing practices translate into improved perioperative outcomes.

Our study identified a significantly higher incidence of blood loss anemia among opioid-dependent patients (OR 1.79, p < .001). We initially hypothesized that opioids may interfere with the clotting cascade, potentially contributing to increased perioperative blood loss. However, our findings did not support this hypothesis. Conversely, existing literature suggests that opioid use may impair antiplatelet medication absorption, which could exacerbate perioperative hemostatic challenges (28–30). These findings underscore the need for further research into the interplay between opioid dependence and coagulation mechanisms in surgical patients.

From a clinical perspective, our findings emphasize the critical importance of preoperative screening for opioid dependence and the potential perioperative complications associated with chronic opioid use. The growing body of evidence supporting non-opioid-based pain management protocols demonstrates promising results in postoperative pain control (17–19). As such, multimodal analgesic strategies should be considered to mitigate the adverse impact of opioid dependence on surgical outcomes and facilitate enhanced recovery following lumbar spine fusion.

This study comes with certain limitations due to the use of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, which may affect its applicability in orthopedic surgery research. First, coding inaccuracies remain a persistent challenge, as administrative datasets rely on procedural and diagnostic codes rather than direct clinical validation. Such discrepancies may introduce misclassification bias, potentially affecting the reliability of reported outcomes. Second limitation of our study is the spectrum of opioid dependence, which varies based on the duration and intensity of opioid consumption. Additionally, we are unable to determine whether a patient previously underwent rehabilitation or successful opioid cessation but still retains an opioid dependence diagnostic code in their medical records. This limitation may lead to potential misclassification and affect the accuracy of our analysis regarding the true burden of opioid dependence in patients undergoing lumbar spine fusion. Third, the NIS database exclusively captures inpatient encounters, thereby precluding the assessment of outpatient perioperative factors that could significantly influence surgical outcomes. This limitation may result in an underestimation of postoperative complications that manifest beyond the index hospitalization or are managed in ambulatory settings. Third, the absence of longitudinal follow-up restricts our ability to evaluate critical postoperative endpoints, such as implant longevity, late-onset infections, or delayed mechanical failures. Consequently, conclusions regarding long-term LF outcomes, particularly among opioid-dependent patients, remain incomplete. Future research integrating linked databases or prospective cohort designs is warranted to overcome these limitations and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing long-term surgical success.

This study also possesses several noteworthy strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to comprehensively analyze multiple years of data utilizing the ICD-10 coding system, thereby ensuring the applicability of our findings to contemporary clinical practice and healthcare reimbursement frameworks. The use of standardized coding methodologies enhances the comparability of our results with future research and facilitates robust epidemiological assessments. Moreover, the inclusion of an extended temporal dataset strengthens the statistical power of our analyses, providing a broader and more representative sample than prior studies. By incorporating six years of data, we offer a comprehensive evaluation of trends in hospitalization costs and length of stay, yielding valuable insights into the economic and institutional determinants influencing lumbar fusion outcomes. These factors are critical for optimizing resource allocation, refining perioperative management strategies, and informing health policy decisions.

In conclusion, opioid dependence remains a complicating factor in postoperative outcomes of LF, imposing additional burdens on healthcare systems through prolonged hospitalizations and increased costs. Future studies are warranted to investigate the impact of opioids on coagulation mechanisms, as opioid use may influence thrombotic or bleeding tendencies, potentially affecting postoperative outcomes. Additionally, further research should explore the spectrum of opioid dependence and its varying degrees of impact on surgical complications, recovery trajectories, and long-term functional outcomes. Understanding these relationships could lead to optimized perioperative pain management strategies and improve risk stratification for opioid-dependent patients undergoing lumbar spine fusion.

Conflict of Interest

None declared

References

- Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, Hickman M, Vickerman P, Marshall BDL, et al. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet. 2019 Oct 26;394(10208):1560–79. [CrossRef]

- Dowell D, Brown S, Gyawali S, Hoenig J, Ko J, Mikosz C, et al. Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: Population Estimates—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024 Jun 27;73(25):567–74.

- Alexander GC, Ballreich J, Mansour O, Dowdy DW. Effect of reductions in opioid prescribing on opioid use disorder and fatal overdose in the United States: a dynamic Markov model. Addiction. 2022 Apr;117(4):969–76. [CrossRef]

- Hills JM, Pennings JS, Archer KR, Wick JB, Daryoush J, Butler M, et al. Preoperative Opioids and 1-year Patient-reported Outcomes After Spine Surgery. Spine. 2019 Jun 15;44(12):887–95. [CrossRef]

- Armaghani SJ, Lee DS, Bible JE, Archer KR, Shau DN, Kay H, et al. Preoperative opioid use and its association with perioperative opioid demand and postoperative opioid independence in patients undergoing spine surgery. Spine. 2014 Dec 1;39(25):E1524-30. [CrossRef]

- Uhrbrand P, Helmig P, Haroutounian S, Vistisen ST, Nikolajsen L. Persistent opioid use after spine surgery: A prospective cohort study. Spine. 2021 Oct 15;46(20):1428–35.

- Elsamadicy AA, Sandhu MRS, Reeves BC, Freedman IG, Koo AB, Jayaraj C, et al. Association of inpatient opioid consumption on postoperative outcomes after open posterior spinal fusion for adult spine deformity. Spine Deform. 2023 Mar;11(2):439–53. [CrossRef]

- Berg J, Wahood W, Zreik J, Yolcu YU, Alvi MA, Jeffery M, et al. Economic Burden of Hospitalizations Associated with Opioid Dependence Among Patients Undergoing Spinal Fusion. World Neurosurg. 2021 Jul;151:e738–46.

- Jain N, Phillips FM, Weaver T, Khan SN. Preoperative Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Risk Factor for Complications, Readmission, Continued Opioid Use and Increased Costs After One- and Two-Level Posterior Lumbar Fusion. Spine. 2018 Oct 1;43(19):1331–8.

- Idrizi A, Paracha N, Lam AW, Gordon AM, Saleh A, Razi AE. Association of opioid use disorder on postoperative outcomes following lumbar laminectomy: A nationwide retrospective analysis of the medicare population. Int J Spine Surg. 2022 Dec;16(6):1034–40. [CrossRef]

- Pirkle S, Reddy S, Bhattacharjee S, Shi LL, Lee MJ. Chronic opioid use is associated with surgical site infection after lumbar fusion. Spine. 2020 Jun 15;45(12):837–42.

- Mierke A, Chung JH, Cheng WK, Danisa OA. 218. Preoperative opioid use is associated with increased readmission and reoperation rates following lumbar decompression, instrumentation and fusion. Spine J. 2020 Sep;20(9):S108. [CrossRef]

- Wang MC, Harrop JS, Bisson EF, Dhall S, Dimar J, Mohamed B, et al. Congress of Neurological Surgeons Systematic Review and Evidence-Based Guidelines for Perioperative Spine: Preoperative Opioid Evaluation. Neurosurgery. 2021 Oct 13;89(Suppl 1):S1–8.

- Kha ST, Scheman J, Davin S, Benzel EC. The impact of preoperative chronic opioid therapy in patients undergoing decompression laminectomy of the lumbar spine. Spine. 2020 Apr 1;45(7):438–43. [CrossRef]

- Edwards DA, Hedrick TL, Jayaram J, Argoff C, Gulur P, Holubar SD, et al. American society for enhanced recovery and perioperative quality initiative joint consensus statement on perioperative management of patients on preoperative opioid therapy. Anesth Analg. 2019 Aug;129(2):553–66. [CrossRef]

- Wu CL, King AB, Geiger TM, Grant MC, Grocott MPW, Gupta R, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Perioperative Opioid Minimization in Opioid-Naïve Patients. Anesth Analg. 2019 Aug;129(2):567–77.

- Chin KJ, Lewis S. Opioid-free Analgesia for Posterior Spinal Fusion Surgery Using Erector Spinae Plane (ESP) Blocks in a Multimodal Anesthetic Regimen. Spine. 2019 Mar 15;44(6):E379–83.

- Kaciroglu A, Ekinci M, Gurbuz H, Ulusoy E, Ekici MA, Dogan Ö, et al. Surgical vs ultrasound-guided lumbar erector spinae plane block for pain management following lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Eur Spine J. 2024 Jul;33(7):2630–6. [CrossRef]

- Elder JB, Hoh DJ, Wang MY. Postoperative continuous paravertebral anesthetic infusion for pain control in lumbar spinal fusion surgery. Spine. 2008 Jan 15;33(2):210–8.

- Tank A, Hobbs J, Ramos E, Rubin DS. Opioid Dependence and Prolonged Length of Stay in Lumbar Fusion: A Retrospective Study Utilizing the National Inpatient Sample 2003-2014. Spine. 2018 Dec 15;43(24):1739–45.

- Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain—United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022 Nov 4;71(3):1–95.

- Livingston CJ, Berenji M, Titus TM, Caplan LS, Freeman RJ, Sherin KM, et al. American college of preventive medicine: addressing the opioid epidemic through a prevention framework. Am J Prev Med. 2022 Sep;63(3):454–65. [CrossRef]

- Weick J, Bawa H, Dirschl DR, Luu HH. Preoperative Opioid Use Is Associated with Higher Readmission and Revision Rates in Total Knee and Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018 Jul 18;100(14):1171–6.

- Martini ML, Nistal DA, Deutsch BC, Caridi JM. Characterizing the risk and outcome profiles of lumbar fusion procedures in patients with opioid use disorders: a step toward improving enhanced recovery protocols for a unique patient population. Neurosurg Focus. 2019 Apr 1;46(4):E12.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Munigala S, Gong J, Schoenfeld RJ, Banaag A, Coles C, et al. Reductions in sustained prescription opioid use within the US between 2017 and 2021. Sci Rep. 2024 Jan 16;14(1):1432. [CrossRef]

- Larochelle MR, Jones CM, Zhang K. Change in opioid and buprenorphine prescribers and prescriptions by specialty, 2016-2021. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023 Jul 1;248:109933. [CrossRef]

- Casillas SM, Pickens CM, Stokes EK, Walters J, Vivolo-Kantor A. Patient-Level and County-Level Trends in Nonfatal Opioid-Involved Overdose Emergency Medical Services Encounters—491 Counties, United States, January 2018-March 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Aug 26;71(34):1073–80.

- Kuczyńska K, Boncler M. Emerging role of fentanyl in antiplatelet therapy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020 Sep;76(3):267–75. [CrossRef]

- Hobl E-L, Stimpfl T, Ebner J, Schoergenhofer C, Derhaschnig U, Sunder-Plassmann R, et al. Morphine decreases clopidogrel concentrations and effects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 Feb 25;63(7):630–5.

- McEvoy JW, Ibrahim K, Kickler TS, Clarke WA, Hasan RK, Czarny MJ, et al. Effect of intravenous fentanyl on ticagrelor absorption and platelet inhibition among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PACIFY randomized clinical trial (platelet aggregation with ticagrelor inhibition and fentanyl). Circulation. 2018 Jan 16;137(3):307–9.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).