1. Introduction

Hearing loss and Deafness is defined as the difficulty in the ability to hear sounds at thresholds that are considered normal in pure tones corresponding mainly to the frequencies 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz. The prevalence of hearing loss in newborns has remained stable according to the information provided by the WHO in its world report [

1], although the age of detection has changed thanks to the implementation of neonatal hearing screening [

2,

3]. This early detection allows for rapid hearing implementation with either hearing aids or cochlear implants.

Within the types of hearing loss and their different degrees, we find cases in which this hearing impairment is associated with other pathologies covering a wide range of conditions that can range from visual, motor and cognitive disabilities to language and communication disorders, in these we can also include autism spectrum disorder, developmental delays and behavioral problems. These comorbidities can vary in type and severity, so there is a great heterogeneity of the studies, which complicates the results and the possible evaluation of this group [

4,

5].

In 2011, the Gallaudet Institute Research published a study indicating that approximately 40% of people with hearing impairment will also have an associated developmental disorder, which can lead to a delay in the diagnosis of hearing loss and consequently a delay in appropriate intervention.

The presence of this high proportion of associated disorders is generally because the risk factors for hearing loss coincide in many cases with the risk factors for other disabilities such as genetics syndromes, prematurity, meningitis or congenital infections [

6]. In recent years, this has been described in studies as hearing loss or deafness plus [

7,

8].

According to the study by Núñez-Batalla et al. [

7], in this group of people with deafness plus, 20% will have more than 2 associated disabilities, which will hinder adequate progress in language development, due to the repercussions that these associated disorders may have.

Among the associated disorders that have the greatest impact on the language development of children with hearing loss or deafness include autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, and global developmental delay. In addition to these, other important associated disorders include vision disorders, syndromes without developmental delay, and other medical and health problems [

7].

Unfortunately, this group of children with hearing loss or deafness plus (HL/D+) may have a delay in hearing screening, even when their medical needs are well addressed. In general, it has been found that children with hearing impairment without associated pathologies are screened 25 days earlier than those with HL/D+ and are therefore diagnosed earlier [

8,

9].

For many years, these children were not considered suitable candidates for cochlear implantation, as outcomes were uncertain and pre- and post-implant management was difficult [

10,

11]. Despite this, cochlear implantation in such children has been shown to result in improvements in auditory perception and speech production, along with improved quality of life [

5,

12].

In 2013, Ching et al.[

13] found that the HL/D+ group achieves worse levels of language development when compared to their peers with typical hearing of the same age and maybe 1 to 2 standard deviations behind them.

Studies show that differences in the cognitive abilities of these children will show a wide variability in outcomes, with better language development outcomes being associated with better levels of cognitive development, but also possibly associated with non-verbal skills, the degree of less profound hearing loss, the use of oral communication in early intervention, a higher level of education of the mother and early fitting of either hearing aids or cochlear implants [

14]. This variability in outcomes means that many studies of both auditory speech perception and language development outcomes in cochlear implanted children prefer not to consider those with other associated disabilities [

10,

11,

15,

16]. Currently, there is still little literature on the outcomes of cochlear implantation in this population, which makes more studies on the subject necessary [

17].

The diagnosis of a HL/D+ can generate greater stress in families which will interfere with the acceptance of the situation and decision-making, for this reason, it is very important that the professionals involved guide the family and give adequate emotional support to promote the optimal development of the child’s minor [

7,

8].

One of the important processes that begin after cochlear implant activation is auditory speech perception, which is very important for language development and is the focus of this study.

Auditory speech perception can be assessed with different tests, some of which are very simple to apply, such as the Ling test [

18]. Despite its simplicity, its validity has been proven [

19,

20]. In Chile, where we carried out this study, the tests for the word perception through suprasegments [

21], vowels [

22] and consonants [

23], the open-format sentence list [

24], among others, are also used. The results of these tests are usually summarized in a number that corresponds to the category of speech perception and reflects the skills that the person using hearing aids or cochlear implants has developed.

The Categories of Speech Perception (CAP), developed by Archbold et al. [

25], is a scale that serves to quantify the auditory receptive abilities of hearing-impaired people. The validity, reliability and trustworthiness have been well documented in different studies [

5,

26].

It is very easy to use and understand by non-specialist professionals and parents. It allows monitoring of progress over time.

Table 1 shows the 8 levels of the scale.

Archbold et al., 1995

The aim of this study was to investigate the progress in auditory speech perception in a group of cochlear implanted children with other concomitant pathology, implanted in a public hospital in the south of Chile.

The study has a longitudinal approach, as we compared the scores obtained before IC surgery and 12 months after activation.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants:

All paediatric patients implanted at the Dr. Guillermo Grant Benavente Regional Clinical Hospital of Concepción from the start of its cochlear implant programme in August 2013 until December 2019 were considered. During that period, 64 children between 1 year 6 months and 16 years 11 months received a cochlear implant through public funds.

Parents, caregivers or legal guardians were informed about the study and asked to sign an informed consent form during their regular cochlear implant check-ups. In addition, those older than 12 years had to sign an informed consent form. Of the initial target group, 57 gave their consent for data collection from their medical records.

The inclusion criteria for this study were:

- (a)

Diagnosis of severe or profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss.

- (b)

Presence of an associated pathology.

- (c)

Who received a cochlear implant through a public programme.

- (d)

Have an auditory speech perception assessment pre cochlear implant and 12 months after implant.

- (e)

Consistent use of the sound processor.

The final group consisted of 18 children who met these criteria. The associated pathologies present in the group were autism spectrum disorder (ASD), cerebral palsy, global developmental delay, Usher Syndrome and Waardenburg Syndrome. All of them were unilaterally implanted.

Speech perception ability was measured with the speech perception categories (Archbold et al., 1995).

For statistical analyses, the Jamovi program was used.

3. Results

The results of the 18 children in the study group are presented below.

Figure 1 shows the gender distribution of the group studied.

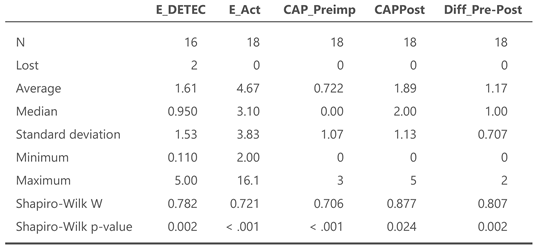

The mean age at detection was 1.6 years, but the median is 0.9 years, suggesting a possible skewness of the data. Only in two cases is the age at detection (E_detec) missing, which is considered a low loss rate overall, in the other data we have the information for all 18 children.

The minimum age of activation (E_Act) was 2 years, and the maximum age was 16.1 years. The median age of activation was 3.10 years.

The median of the preimplant CAP (CAP_Preimp) was 0, meaning that there was no detection of the presence of sounds and at 12 months post implant (CAPPost), the median is 2. The maximum improvement between both periods was two categories, although the median is 1 (Dif_Pre-Post), so it can be said that there is an evident improvement.

Table 2 summarizes these descriptive data and sample distribution.

The standard deviations indicate a high dispersion for the age of detection and implant activation, these variables have a very wide range of values.

To assess the distribution of the sample we use the nonparametric Shapiro-Wilk test, for small samples. It shows that the variables do not follow a normal distribution, as their p-values for all variables are <0.05.

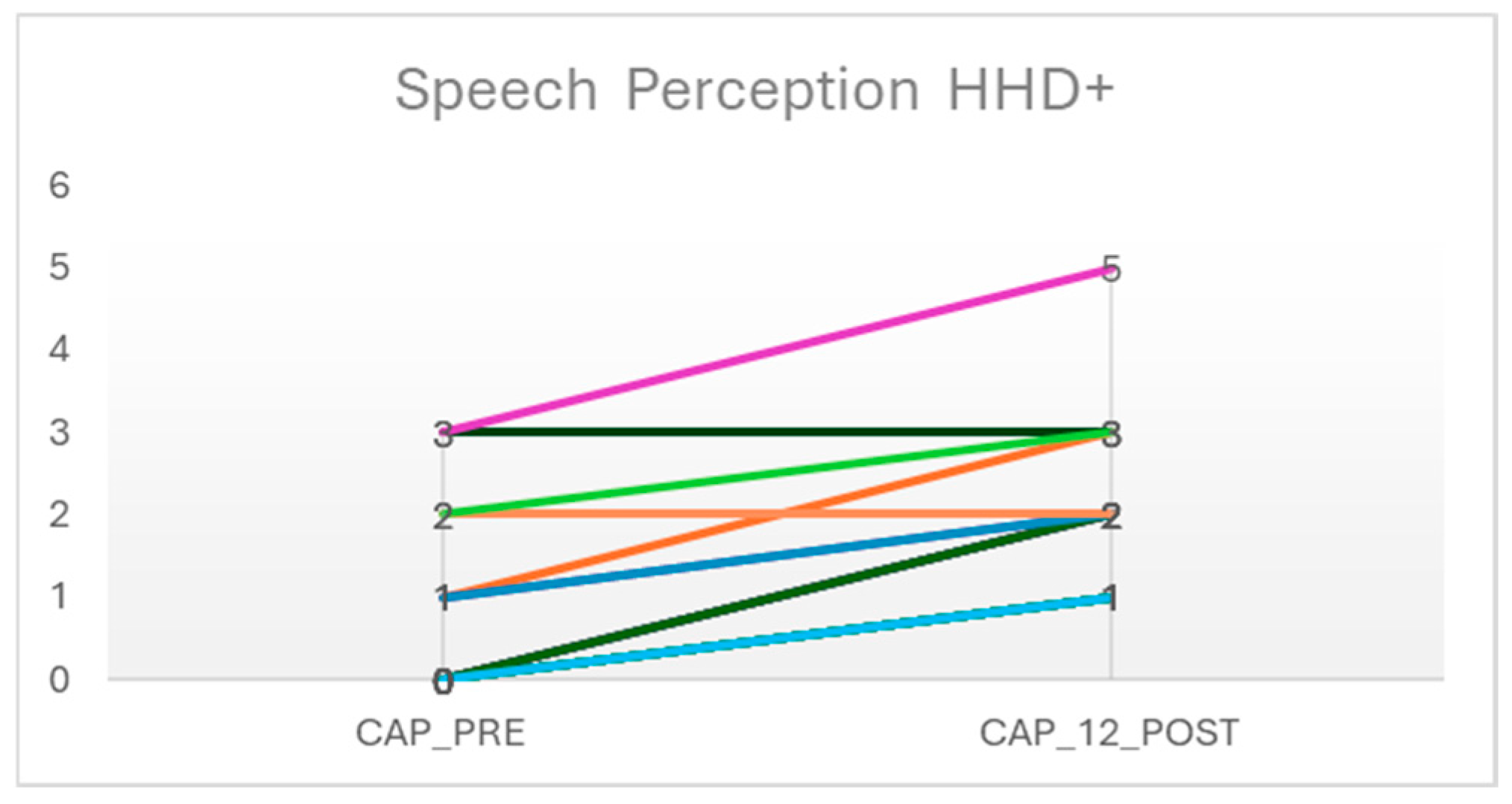

Figure 2 compares the acoustic speech perception results measured with the CAP. There is a clear trend towards improvement observed. Although there are two cases that after 12 months remain at the same level of auditory speech perception.

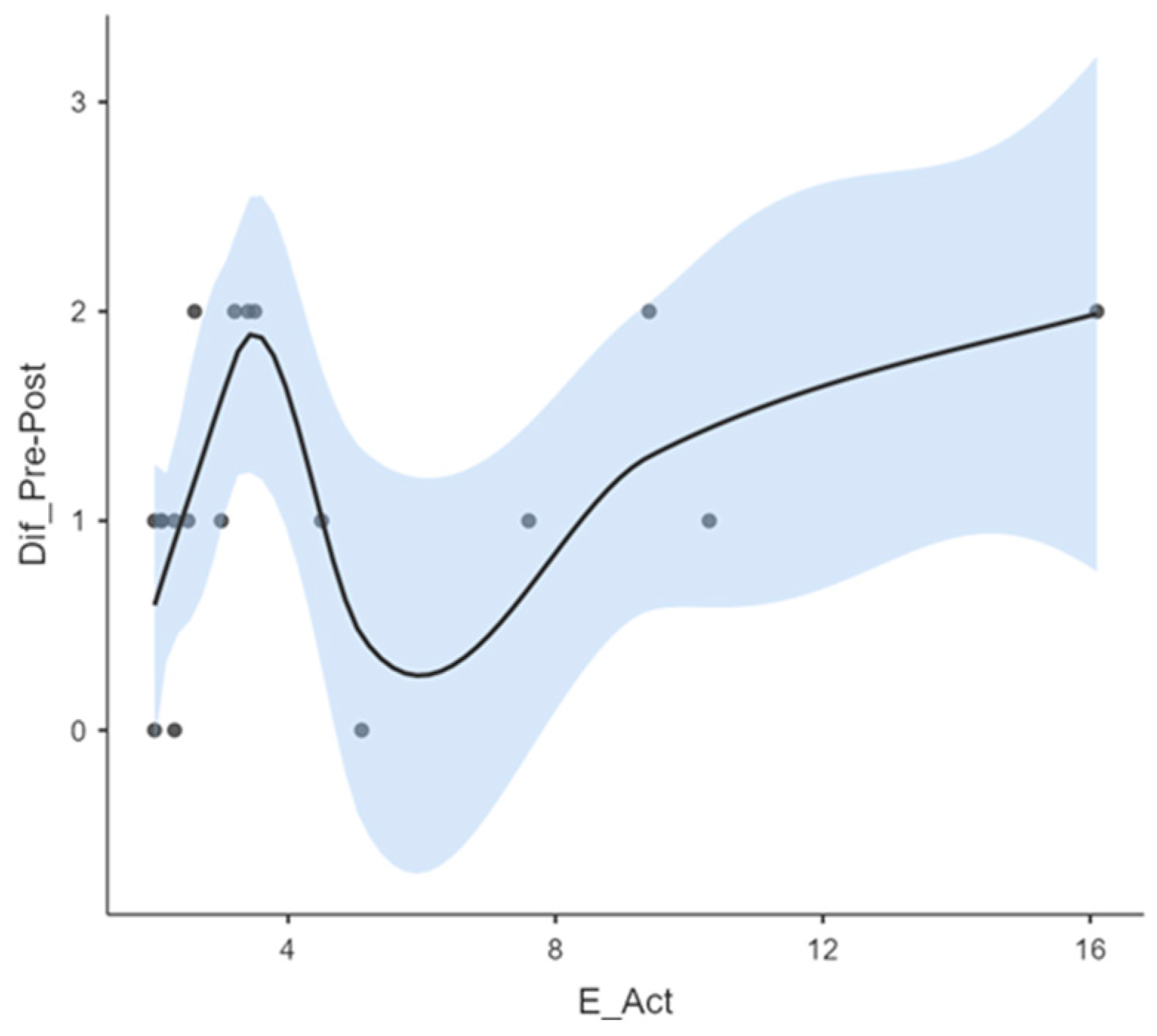

According to the age of activation, it can be seen in graph 3 how quickly activated children progress at an early age, up to around 4 years old, so that the effectiveness of the CI is associated with the age of activation. After that age, progress occurs more slowly. Specifically, between the ages of 4 and 8 years, where a decrease in the difference of the CAP pre and post CI is observed, indicating a non-linear relationship and therefore the improvement in this group is not so evident, but after 8 years of age the relationship is positive again, with a greater and consistent effectiveness.

The smoothed curve shows the general trend in the relationship between activation age and the difference between pre-post CAP. The blue shaded area indicates the confidence interval around the curve. At younger ages the confidence interval is narrower, indicating greater certainty in the estimates within this range. At older ages the confidence interval is wider, showing greater uncertainty in the estimates.

The results show that the clear relationship between activation age and improvement in auditory speech perception is complex and non-linear. The data suggests that the impact of activation age on improvement may depend on the specific age range. This explains why there might be inflection points at which the activation age has a more pronounced effect on the observed improvements.

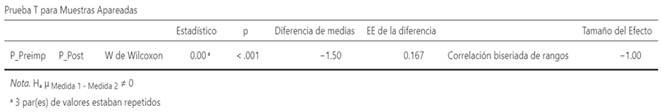

Table 3 below shows the t-test performed to complement the results presented in the previous tables and graphs. This table shows that children with D+ have a p-value <.001, which assures us that the difference found is not due to chance. There is a statistically significant difference in the perception of the studied group, confirming that the auditory perception of speech increased significantly after the CI.

Auditory speech perception is the recognition, awareness, and interpretation of sounds in the brain [

27]. This perception is the basis for the development of normal communication [

28], playing an important role in language development [

29]. For children with deafness, the cochlear implant is a tool to enable them to access auditory speech perception, although the age of implantation has been found to be a determining factor for a good prognosis [

30,

31,

32].

Children with D+ face greater barriers in this regard [

33,

34] and as mentioned above, were long excluded from both CI candidacy and subsequently from studies reporting CI results to improve the homogeneity of samples [

17]. For this reason, there are few studies in this regard to help families and the professionals working with them.

In general, studies of CI effectiveness in children with D+ have traditionally focused on measuring speech perception, speech intelligibility, and language development, as well as questionnaires and structured interviews for parents. Among the studies that can be found, there are some that include a wide range of additional conditions, while others focus exclusively on a particular disability [

4,

17,

35]. In our case, we will focus on auditory speech perception.

In the study group, the mean age of detection was 1.6 years, which is considered an early age. Although the range of the activation age (and therefore of implantation) is quite wide, ranging from 2.0 years to 16.1 years, the majority were able to receive the implant at a relatively early age. The median of 3.10 years exceeds by a couple of months what is usually considered an early and timely age, which is mentioned in some studies as being up to 3.0 years [

36,

37], but considering that there are studies indicating that children with D+ may delay their diagnosis and implementation compared to those who are only deaf [

8,

9], we consider the median to be early.

In our sample, the comorbidities we found were autism spectrum disorder (ASD), pervasive developmental delay, cerebral palsy, Waardenburg syndrome and Usher syndrome. For each of these pathologies, we found mixed evidence regarding progress in auditory speech perception, with some reporting results similar to those of deaf children with CI without another pathology [

8,

38] and others reporting slower progress [

39]. The review by Cejas et al.[

4] brings together studies in this regard, of which, regardless of comorbidity and degree of impairment, the summary is that all have advances in auditory speech perception, although not at the same speed.

In our study we found a clear improvement in speech perception in most of the children, only two of them remained in the same category of perception at 12 months after activation, in all the others the improvement was between one and two categories. The majority of our group started from a CAP 0 before cochlear implantation, that is, they had no sound awareness. At 12 months after activation we found that the highest categories achieved by most of the group were in response to speech sounds (category 2) and identification of environmental sounds (category 3). Only one reached sentence comprehension without lip-reading (category 5), but his starting point was in category 3, so the improvement within the first year of use was within the same range of improvement as the others. Rafferty et al. [

40] found in their study that at 12 months after the CI there were children who reached a maximum category 3, a similar progress to what we found, who improved between 2 and 3 categories during the first year.

We also found that those who were implanted up to around 4 years of age made greater and faster progress than those implanted later. This is consistent with the findings of Jatana et al. [

41].

It is important to encourage families to use the processor consistently and to clarify the expectations that can be expected from using the CI. While many parents may expect their children to develop spoken language similar to other children in their environment, associated disabilities may interfere with the developmental outcomes of auditory perception and therefore language, and so ideally other ways to measure the results , such as improvements in quality of life, social interaction and adaptive skills, should be sought that are not reflected in standard measures of progress [

17].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we can say that there is a clear benefit of cochlear implantation in children with D+, although in some cases this benefit, at least in terms of auditory perception, is more limited, but it allows them access to the world of sound and, although they do not achieve oral language development, parents often mention that they notice changes in the way they relate to their environment, which is already an improvement in their quality of life.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research is part of the study approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Health Service of Concepción (Chile), "Evaluation of speech perception in children implanted at the Dr. Guillermo Grant Benavente Regional Clinical Hospital", number 20-03-10. The study is part of an ongoing doctoral thesis at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parents and caregivers of minors participating in the study; those over 12 years of age were also asked to sign an informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not available because the data are part of an ongoing PhD thesis.

Acknowledgments

To the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Health Service of Concepción (Chile) and to the parents and caregivers of the children who agreed to participate. This work has been carried out within the framework of the PhD programme in Psychology of Communication and Change of the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASD |

Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| CAP |

Category of Auditory Performance |

| CI |

Cochlear implant |

| D+ |

Deafness Plus |

| HHD+ |

Hard of hearing or deafness plus |

References

-

World report on hearing. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021.

- C. Yoshinaga-Itano, V. Manchaiah, y C. Hunnicutt, «Outcomes of Universal Newborn Screening Programs: Systematic Review», J. Clin. Med., vol. 10, n.o 13, p. 2784, jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Edmond et al., «Effectiveness of universal newborn hearing screening: A systematic review and meta-analysis», J. Glob. Health, vol. 12, p. 12006, oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Cejas, M. Hoffman, y A. Quittner, «Outcomes and benefits of pediatric cochlear implantation in children with additional disabilities: a review and report of family influences on outcomes», Pediatr. Health Med. Ther., p. 45, may 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Rawes, L. M. Ngaage, R. Mackenzie, J. Martin, A. Cordingley, y C. Raine, «A review of the outcomes of children with designated additional needs receiving cochlear implantation for severe to profound hearing loss», Cochlear Implants Int., vol. 22, n.o 6, pp. 338-344, nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, «Year 2019 JCIH Position Statement.pdf». 2019. [En línea]. Disponible en. [CrossRef]

- F. Núñez-Batalla, C. Jáudenes-Casaubón, J. M. Sequí-Canet, A. Vivanco-Allende, y J. Zubicaray-Ugarteche, «Sordera infantil con discapacidad asociada (DA+): recomendaciones CODEPEH», Acta Otorrinolaringológica Esp., p. S0001651923000043, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Wiley, R. S. John, y C. Lindow-Davies, «Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing PLUS», 2022, [En línea]. Disponible en: https://www.infanthearing.org/ehdi-ebook/.

- D. A. Chapman et al., «Impact of Co-Occurring Birth Defects on the Timing of Newborn Hearing Screening and Diagnosis», Am. J. Audiol., vol. 20, n.o 2, pp. 132-139, dic. 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Lachowska, A. Pastuszka, Z. Łukaszewicz-Moszyńska, L. Mikołajewska, y K. Niemczyk, «Cochlear implantation in autistic children with profound sensorineural hearing loss», Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol., vol. 84, n.o 1, pp. 15-19, ene. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Wakil, E. M. Fitzpatrick, J. Olds, D. Schramm, y J. Whittingham, «Long-term outcome after cochlear implantation in children with additional developmental disabilities», Int. J. Audiol., vol. 53, n.o 9, pp. 587-594, sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. V. Hayward, K. Ritter, J. Grueber, y T. Howarth, «Outcomes That Matter for Children With Severe Multiple Disabilities who use Cochlear Implants: The First Step in an Instrument Development Process», 2013.

- T. Y. C. Ching et al., «Outcomes of Early- and Late-Identified Children at 3 Years of Age: Findings From a Prospective Population-Based Study», Ear Hear., vol. 34, n.o 5, pp. 535-552, sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Cupples et al., «Spoken language and everyday functioning in 5-year-old children using hearing aids or cochlear implants», Int. J. Audiol., vol. 57, n.o sup2, pp. S55-S69, mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Ashori, «Speech intelligibility and auditory perception of pre-school children with Hearing Aid, cochlear implant and Typical Hearing», J. Otol., vol. 15, n.o 2, pp. 62-66, jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Majorano et al., «Preverbal Production and Early Lexical Development in Children With Cochlear Implants: A Longitudinal Study Following Pre-implanted Children Until 12 Months After Cochlear Implant Activation», Front. Psychol., vol. 11, p. 591584, nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Young, C. Weil, y E. Tournis, «Redefining Cochlear Implant Benefits to Appropriately Include Children with Additional Disabilities», en Pediatric Cochlear Implantation, Springer, 2016, pp. 213-224. [En línea]. Disponible en:. [CrossRef]

- D. Ling, «Speech and the hearing-impaired child theory and practice.pdf». Washington : Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf, 1976. [En línea]. Disponible en: https://archive.org/details/speechhearingim00ling.

- K. B. Agung, S. C. Purdy, y C. Kitamura, «The ling sound test revisited», Aust. N. Z. J. Audiol., vol. 27, n.o 1, pp. 33-41, 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. McDonnell, «The Ling Sound Test: What Is Its Relevance in the New Zealand Classroom?.», Kairaranga, vol. 15, n.o 2, pp. 48-55, 2014.

- F. H. M. Furmanski, C. Berneker, M. A. Levato, y M. Oderigo, «PIP S.pdf». 1999.

- H. Furmanski y S. Yebra, «PIP V.pdf». 2000.

- H. Furmanski, M. Flandin, M. Howlin, M. Sterin, y S. Yebra, «PIP-C.pdf». 1997.

- T. Mansilla, «OFA-N.pdf». [En línea]. Disponible en: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/0573bf74-211e-4b39-9795-380b9d5cfc1a/downloads/OFA-N.pdf.

- Archbold y S., «Categories of Auditory Performance.», Ann. Otol. Rhinol., vol. 166, Accedido: 6 de agosto de 2020. [En línea]. Disponible en: http://mendeley.csuc.cat/fitxers/ecc1f003dbd9e4fdca4d0bddc8a614c3.

- S. Archbold, T. P. Nikolopoulos, G. M. O’Donoghue, y M. E. Lutman, «Educational placement of deaf children following cochlear implantation», Br. J. Audiol., vol. 32, n.o 5, pp. 295-300, 1998. [CrossRef]

- G. Ciscare, E. Mantello, C. Fortunato-Queiroz, M. Hyppolito, y A. Reis, «Auditory Speech Perception Development in Relation to Patient’s Age with Cochlear Implant», Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol., vol. 21, n.o 03, pp. 206-212, jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Davidson, «La audición Acústica temprana y el papel de la percepción segmental y suprasegmental del habla en el lenguaje hablado y la alfabetización», 2020.

- F. Chen, D. Zheng, y Y. Tsao, «Effects of noise suppression and envelope dynamic range compression on the intelligibility of vocoded sentences for a tonal language», J. Acoust. Soc. Am., vol. 142, n.o 3, pp. 1157-1166, sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Y. Albalawi, M. Nidami, F. Almohawas, A. Hagr, y S. N. Garadat, «Categories of Auditory Performance and Speech Intelligibility Ratings in Prelingually Deaf Children With Bilateral Implantation», Am. J. Audiol., vol. 28, n.o 1, pp. 62-68, mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Y. C. C. Ching, H. Dillon, G. Leigh, y L. Cupples, «Learning from the Longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Impairment (LOCHI) study: summary of 5-year findings and implications», Int. J. Audiol., vol. 57, n.o sup2, pp. S105-S111, mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Dettman et al., «Long-term Communication Outcomes for Children Receiving Cochlear Implants Younger Than 12 Months», Otol. Neurotol., vol. 37, n.o 2, pp. e82-e95, feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Jalil-Abkenar, M. Ashori, M. Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi, y S. Hasanzadeh, «Auditory Perception and Verbal Intelligibility in Children with Cochlear Implant, Hearing Aids and Normal Hearing», Pract. Clin. Psychol., vol. 1, n.o 3, pp. 141-147, 2013.

- D. J. Van de Velde et al., «Prosody perception and production by children with cochlear implants», J. Child Lang., vol. 46, n.o 1, pp. 111-141, ene. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Magalhães, P. Samuel, M. Goffi-Gomez, R. Tsuji, R. Brito, y R. Bento, «Audiological outcomes of cochlear implantation in Waardenburg Syndrome», Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol., vol. 17, n.o 03, pp. 285-290, ene. 2014. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Fitzpatrick, J. Ham, y J. Whittingham, «Pediatric Cochlear Implantation: Why Do Children Receive Implants Late?», vol. 36, n.o 6, 2015.

- A. Kral y A. Sharma, «Developmental neuroplasticity after cochlear implantation», Trends Neurosci., vol. 35, n.o 2, pp. 111-122, feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. Amirsalari, M. Ajallouyean, A. Saburi, A. Haddadi Fard, M. Abed, y Y. Ghazavi, «Cochlear implantation outcomes in children with Waardenburg syndrome», Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol., vol. 269, n.o 10, pp. 2179-2183, oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Hiraumi, N. Yamamoto, T. Sakamoto, S. Yamaguchi, y J. Ito, «The effect of pre-operative developmental delays on the speech perception of children with cochlear implants», Auris. Nasus. Larynx, vol. 40, n.o 1, pp. 32-35, feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Rafferty, J. Martin, D. Strachan, y C. Raine, «Cochlear implantation in children with complex needs – outcomes», Cochlear Implants Int., vol. 14, n.o 2, pp. 61-66, mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. R. Jatana, D. Thomas, L. Weber, M. B. Mets, J. B. Silverman, y N. M. Young, «Usher Syndrome: Characteristics and Outcomes of Pediatric Cochlear Implant Recipients», Otol. Neurotol., vol. 34, n.o 3, pp. 484-489, abr. 2013. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).