1. Introduction

Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis (BPT) is a condition present in infancy. It is described as periodic episodes of torticollis, a head tilt with head rotation that may randomly alter sides. BPT was first described by Snyder 1969 [

1]. It may be associated with other symptoms: vomiting, ataxia, pallor, drowsiness, or irritability [

2,

3]. Episodes can last from hours to days [

3]. The episodes are more frequent and last longer in the earlier months [

4]. The condition is self-limiting and resolves spontaneously by 2-3 years of age [

2,

3]. In a review from 2024, family history for migraine was found in 25% to 100% of cases [

3]. Since 2013, BPT has belonged to a group of “episodic syndromes that may be associated with migraine” [

5].

The aetiology of BPT is unknown, and the prevalence is difficult to establish as the diagnosis is underestimated [

3]. Hadjipanayis et al found 2015 that child neurologists are aware of BPT while pediatricians are not. A telephone survey with eighty-two Cypriot pediatricians showed that only 2.4 % of them were aware of BPT and none was confident regarding its management [

6]. Bratt and Menelaus conclude that no treatment is indicated for BPT. They recommend that these children are kept under review until the episodes are completely resolved [

2]. Neurological findings and motor development have been found to be normal [

4,

7]. Headache is common in childhood [

8] and BPT has been found to give a small to moderate risk of developing migraine [

7,

9,

10].

In pediatric physical therapy settings, a Physical Therapist (PT) meets a lot of infants with torticollis, mostly Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT). It is not uncommon to meet infants with torticollis that alter sides, they usually have a normal passive range of motion in neck rotation and lateral flexion (

clinical experience AÖ). Greve et al found that infants with torticollis that alter sides appear to have a lower cervical range of motion limitations than those that always tilt to the same side [

11]. These infants with torticollis that alter sides are likely to have mild BPT.

Unfamiliarity with BTP among pediatricians can delay diagnosis, lead to unnecessary tests and anxiety for parents [

6]. Likewise, a PT who is not aware of BTP can give an unnecessary training program, treating BPT as CMT. The only action necessary from the PT is to follow progress and motor development, and to react if needed. There are several differential diagnoses other than CMT, some can be life threatening. Even if these are rare we need to be aware of them and react early if indicated [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

The Muscle Function Scale (MFS) is a scale constructed to measure muscle function/strength in lateral flexors of the neck in infants with CMT. An infant with CMT scores higher on the affected side, the side they tilt toward [

17,

18]. Infants that alter sides also show a side difference on the MFS, which the evaluator may interpret as CMT. However, infants with suspected BPT have higher MFS scores on the right side when they tilt toward the right and higher on the left side when they tilt to the left. (

clinical experience AÖ). This means there is probably tension on one side, and this tension alters sides. This may partly be a muscular problem but what really happens in the muscle during a period of tilting is unknow.

2. Case description

An infant aged one and a half months was referred to the clinic for a mild plagiocephaly. He had a severe lack of head control, a wobbly head that he often held in extension. Parents supported his head all the time, meaning there was no natural training of head control. A home training program for head control and tummy time was given.

The infant had colic and vomited a lot according to parents (his older sister had not vomited at all as an infant) otherwise, he was healthy. At two and a half months, his head control had improved but at this age he started to tilt his head severely toward the right (

Figure 1).

The tilting toward the right disappeared and about two weeks later he developed a mild tilt toward the left (

Figure 2).

According to the daily diary they kept, this pattern continued with notes about which side was tilted and if it was mild or severe (

Table 1).

He alternated between the right and left side and between a mild and severe tilt. In the end the tilting was mainly toward the right. The MFS score was always higher on the side he was currently tilting toward. The score changed along with the tilting (

Table 2).

The infant’s mother had migraine, there were no other known health problems in the family.

At the age of six and a half months, his head was mostly in a straight position (

Figure 3).

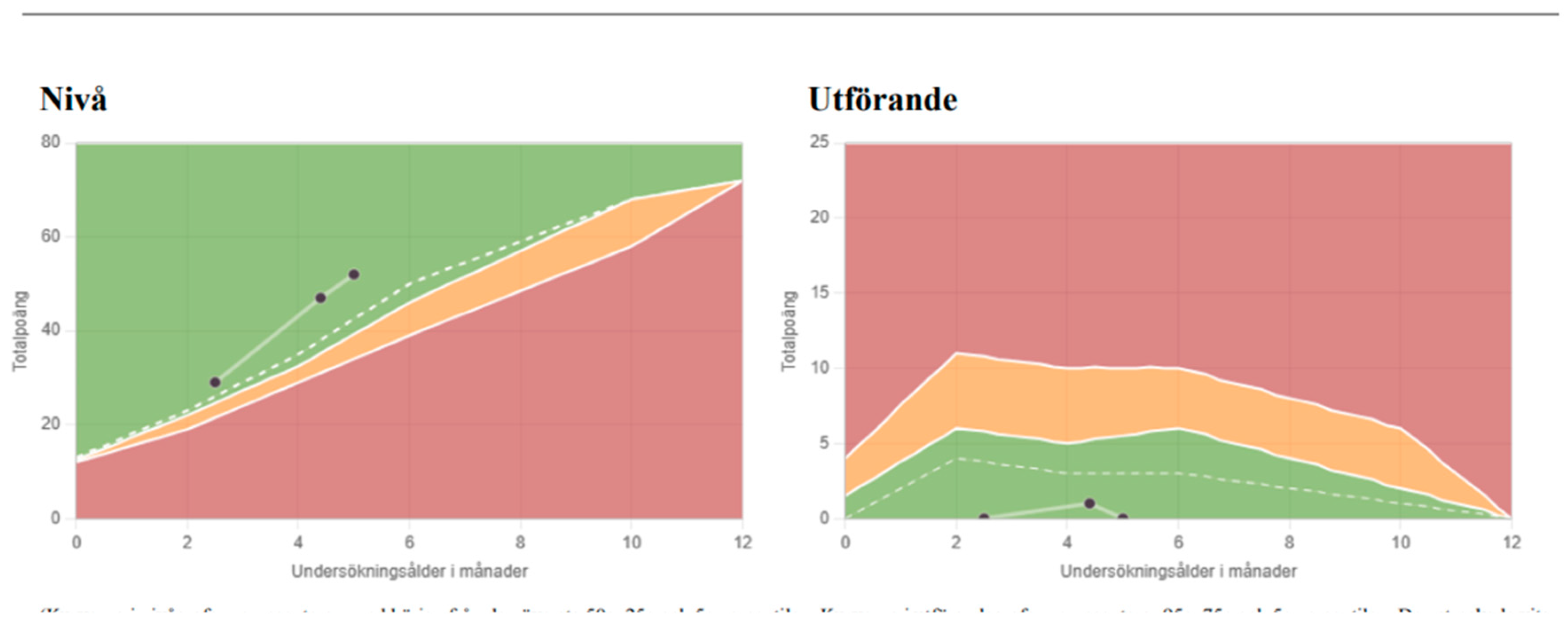

Colic had ended at four months of age and vomiting ended at the same time that he ceased tilting his head. After he gained head control, he had normal motor development (

Figure 4); motor function was above the median using the SOMP-I method (Structured Observation of Motor Performance in Infants) [

19,

20].

3. Discussion

For a pediatric PT it is not uncommon to meet infants with torticollis that alters sides, possibly without obvious associated symptoms. Some parents say on their first visit that the infant’s head has tilted toward alternate sides. Other parents have not noticed this difference; it is discovered when they come to the clinic and the infant suddenly tilts to the opposite side compared with earlier records. These infants are suspected to have mild BPT. Bratt and Menelaus described four cases 1992, the symptoms of the two youngest resolved earlier, before one year of age. Only one of them had associated symptoms [

2], corresponding well with infants with suspected BPT seen by a PT. Infants with severe attacks are probably referred to a neurologist and not to a PT. It is likely that milder cases first mistaken for CMT are referred to a PT.

When the MFS shows a side difference in infants with torticollis, we can’t take for granted that it is CMT. Suspected BPT also gets a higher score on the side the infants currently tilt toward. All PTs working with infants and especially with torticollis need to be aware of BPT. There is a risk of confusion among professionals in child health care as well as for parents. These infants may get unnecessary treatment, as recovery is spontaneous. We need to assure parents about the natural progress of BPT and avoid anxiety [

4]. However, it would be very interesting to know what happens in the muscle during a period of tilting. As there is a difference on the MFS scale during a period of titling, the muscle is affected in some way.

Minor problems with vomiting, irritability, colic may be missed if not asked about. Vomiting is not unusual for infants with or without torticollis. Vomiting, irritability, and drowsiness could in some degree be common to any infant. If they only occur when an infant has a tilting episode, they can be regarded as associated symptoms, but if they occur all the time, it may be within the normal variation. PTs ought to consider standardized questions for all infants with torticollis to catch associated symptoms that may otherwise be missed. Routine control of motor development for all infants with torticollis could also be included. The SOMP-I method evaluating motor performance at ages 0-12 months [

19,

20] or the Alberta Infant Motor Scale (AIMS) at ages 0-18 months [

21,

22] could be used to follow motor development in infants.

Backed up by 30 years’ clinical and research experience, I have used clinical experience for two statements. I am aware that referral to studies is preferable. However, there is a lack of studies about BPT in PT settings. The first statement is: Infants with suspected BPT have no limitation in their passive range of motion. And the second: that suspected BPT is not uncommon. During 2023 I met 193 infants with torticollis and 10% of them altered sides, this was more than I expected. This fits well with Tozzi et al and Hadjipanayis et al conclusions that BPT is underestimated [

3,

6].

4. Conclusion

Mild cases of BPT may be mistaken for CMT and referred to a PT. The PT needs to distinguish BPT from CMT at an early stage to avoid unnecessary treatment. It is important to follow infants with BPT to exclude more severe cause of torticollis. Further studies are needed to get better knowledge of how the SCM muscle is affected in infants with suspected BPT.

Funding

This case report received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to Swedish Ethical Review Authority Statement: “If the intended publication contains only accounts of diagnosis and treatment, or of some other course of events, this practice should be understood not to be a matter of research that must be ethically tested” (

https://etikprovningsmyndigheten.se/faq/kravs-etikprovning-for-fallrapporter/).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the parents to use photos of the infant.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Snyder, C.H. Paroxysmal torticollis in infancy. A possible form of labyrinthitis. Am J Dis Child 1969, 117, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, H.D.; Menelaus, M.B. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992, 74, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozzi, E.; Olivieri, L.; Silva, P. Benign Paroxysmal Torticollis. Life (Basel) 2024, 14, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatanovic, D.; Dimitrijevic, L.; Stankovic, A.; Balov, B. Benign paroxysmal torticollis in infancy – diagnostic error possibility. Vojnosanit Pregl 2017, 74, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 629–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjipanayis AEfstathiou ENeubauer, D. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy: An underdiagnosed condition. J Paediatr Child Health 2015, 51, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, A.; Anderlid, B.-M.; Stödberg, T.; Lagerstedt-Robinson, K.; Klackenberg Arrhenius, E.; Tedroff, K. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy does not lead to neurological sequelae. Dev Med Child Neurol 2018, 60, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, P.E.; Mack, K.J. Episodic and chronic migraine in children. Dev Med Child Neurol 2020, 62, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, L.; von Kries, R.; Straube, A.; Heinen, F.; Obermeier, V.; Landgraf, M.N. Do pre-school episodic syndromes predict migraine in primary school children? A retrospective cohort study on health care data. Cephalgia 2019, 39, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moavero, R.; Papetti, L.; Berucci, M.C.; Cenci, C.; FerilliMAN; Sforza, G. ; Vigevano, F.; Valeriani, M. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and benign paroxysmal torticollis are associated with a high risk of developing primary headache: A longitudinal study. Cephalalgia 2019, 39, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, K.R.; Perry, R.A.; Mischnick, A.K. Infants with torticollis who changed head presentation during physical therapy episode. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2022, 34, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coopermann, D.R. The Differential Diagnosis of Torticollis in Children. Children, Physical & Occupational Therapy Pediatrics, 1997, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumturk, A.; Ozcora, G.K.; Bayram, A.K.; Bayram, A.K.; Kabaklioglu, M.; Dogaanay, S.; Canpolat, M.; Gumus, H.; Kumandas, S.; Unal, E.; Kurtsoy, A.; Per, H. Torticollis in children: an alert symptom not to be turned away. Childs Nerv Syst. 2015, 31, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fąfara-Leś A, Kwiatkowski S, Maryńczak L, Kawecki Z, Adamek D, Herman-Sucharska I and Kobylarz K. Torticollis as a first sign of posterior fossa and cervical spinal cord tumors in children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014, 30, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zvi, B.; Thompson, D.N.P. Torticollis in childhood—a practical guide for initial assessment. Eur J Pediatr 2022, 181, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.K.; Oh, T.; Han, K.J.; Chang, D.; Sun, P.P. A Case of Torticollis in an 8-Month-Old Infant Caused by Posterior Fossa Arachnoid Cyst: An Important Entity for Differential Diagnosis. Pediatr Rep 2021, 13, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A.; Beckung, E. Reference values for range of motion and muscle function in the neck - in infants. Pediatr Phys Ther 2008, 20, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A.; Nilsson, S.; Beckung, E. Validity and reliability of the Muscle Function Scale, aimed to assess the lateral flexors of the neck in infants. Physiother Theory Pract. 2009, 25, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, K.; Strömberg, B. A protocol for structure observation of motor performance in preterm and term infants. Ups J Med Sci 1993, 98, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.; Persson, K.; Sonnander, K.; Magnusson, M.; Sarkadi, A.; Lucas, S. Clinical utility of the structured observation of motor performance in infants within the child health services. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper M, Darrah J, Motor Assessment of the Developing Infant, WB Saunders Company, Philadelphia, 1994.

- Eliks, M.; Gajewska, E. The Alberta Infant Motor Scale: A tool for the assessment of motor aspects of neurodevelopment in infancy and early childhood. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 927502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).