Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Interoperability: Ensuring that all devices can communicate and exchange data seamlessly [6].

- Scalability: Designing systems that maintain efficiency as demands increase [6].

- Fast Deployment: Favoring sustainable, portable solutions that reduce implementation time and labor [6].

- Robustness: Rigorously testing technologies to ensure they can overcome limitations and errors [6].

- Eco-Friendliness and Efficiency: Minimizing power consumption and environmental impact while ensuring cost-effective operation [6].

- Multi-Modal Access: Providing diverse interfaces for input and interaction [6].

- Sustainability: Integrating environmental sustainability as a core design principle [11].

- Explore the concept and key components of smart metering infrastructure.

- Analyze the role of smart meters within the broader context of smart city development.

- Identify and discuss the major challenges in deploying and securing smart metering systems.

- Examine the benefits of integrating UAVs with smart metering systems.

- Provide insights into policy implications and future research directions for optimizing smart metering in urban environments.

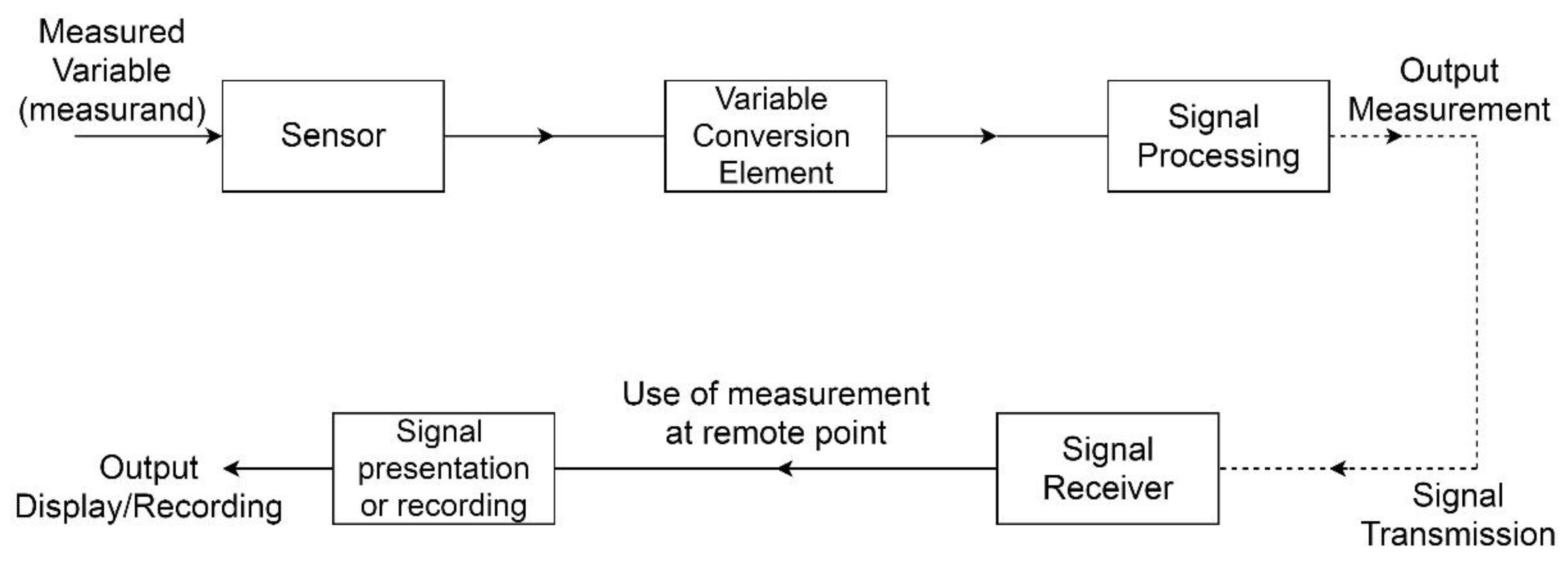

2. A Measuring Instrument: Elements and Features

Traditional and Smart Meters: A Comparison

3. Static Characteristics of Meters

- Accuracy and Uncertainty: This refers to how closely a meter’s reading aligns with the true or accepted value.

- Precision: This describes the degree to which repeated measurements under the same conditions yield the same result, indicating a low spread of values when multiple readings are taken.

- Tolerance: This is the expected maximum error for a given value and is closely related to the concept of accuracy.

- Range or Span: This defines the minimum and maximum limits within which the meter can accurately measure a particular quantity.

- Linearity: This property indicates that the meter’s output is directly proportional to the measured quantity over its operating range.

- Sensitivity: This is the amount of change in the meter’s output that occurs in response to a change in the measured quantity.

- Threshold: This is the minimum level of input required before the meter registers any change in output.

- Resolution: Refers to the relation of measured quantity changes and meter’s output. Where the smallest detectable change in the former results in a discernible change in the latter.

- Sensitivity to Disturbance: Since the validation of a meter’s calibration is considered under standard conditions, such as pressure, temperature, and vibration, any deviation from these conditions may affect its performance. The extent of this effect is measured as sensitivity to disturbance.

- Dead Space: Relates to the range of input values over which there is no observable change in the meter’s output.

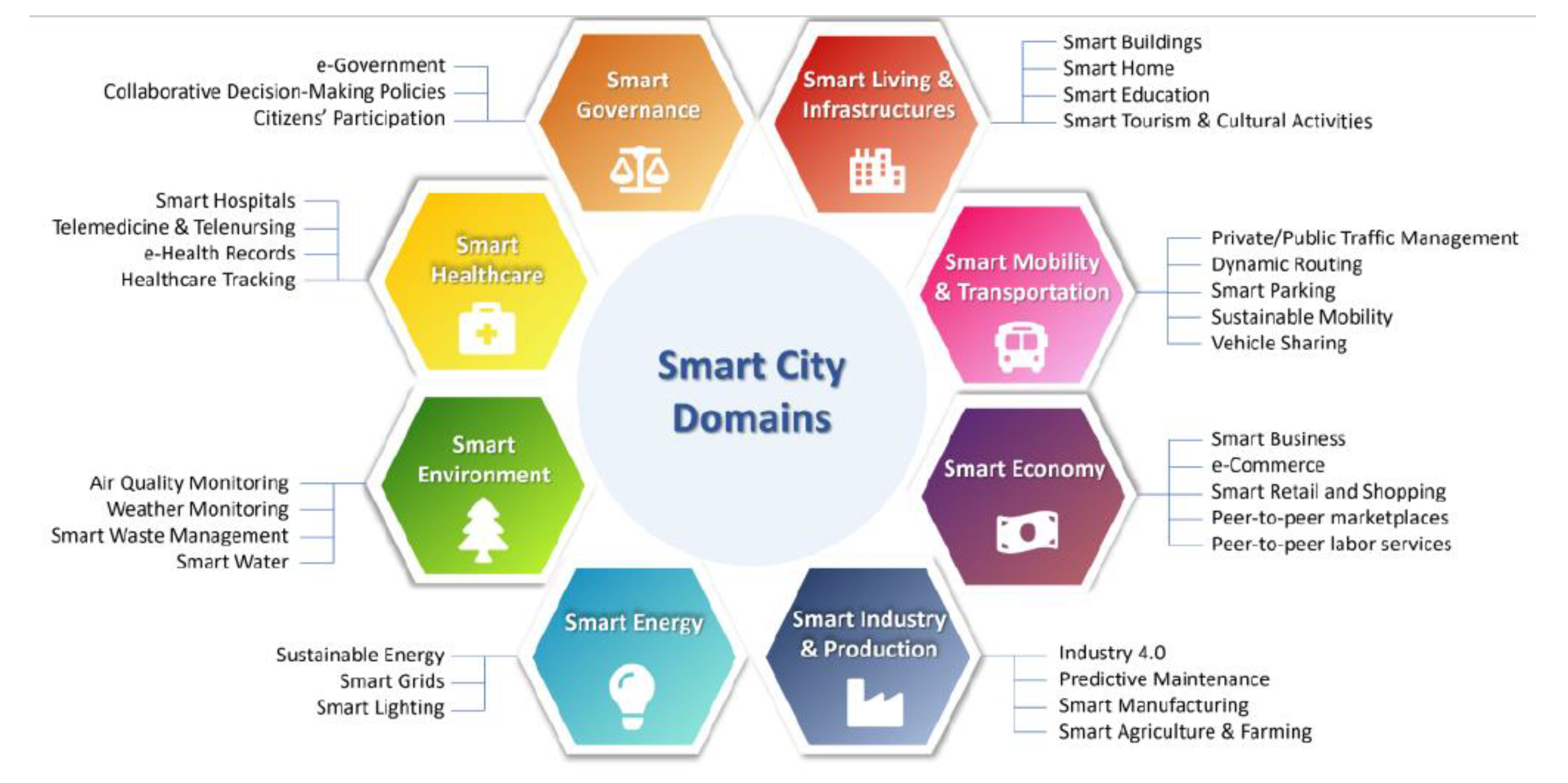

4. Smart City Concept

4.1. Smart City Definitions

- Green: Commitment to protecting the environment and reducing of CO2 emissions.

- Interconnected: A robust, broadband-enabled infrastructure that supports a modern, digitally-driven economy.

- Intelligent: The capacity to process and manage data collected from sensor networks.

- Innovative: Fostering creativity and leveraging the expertise of a skilled population.

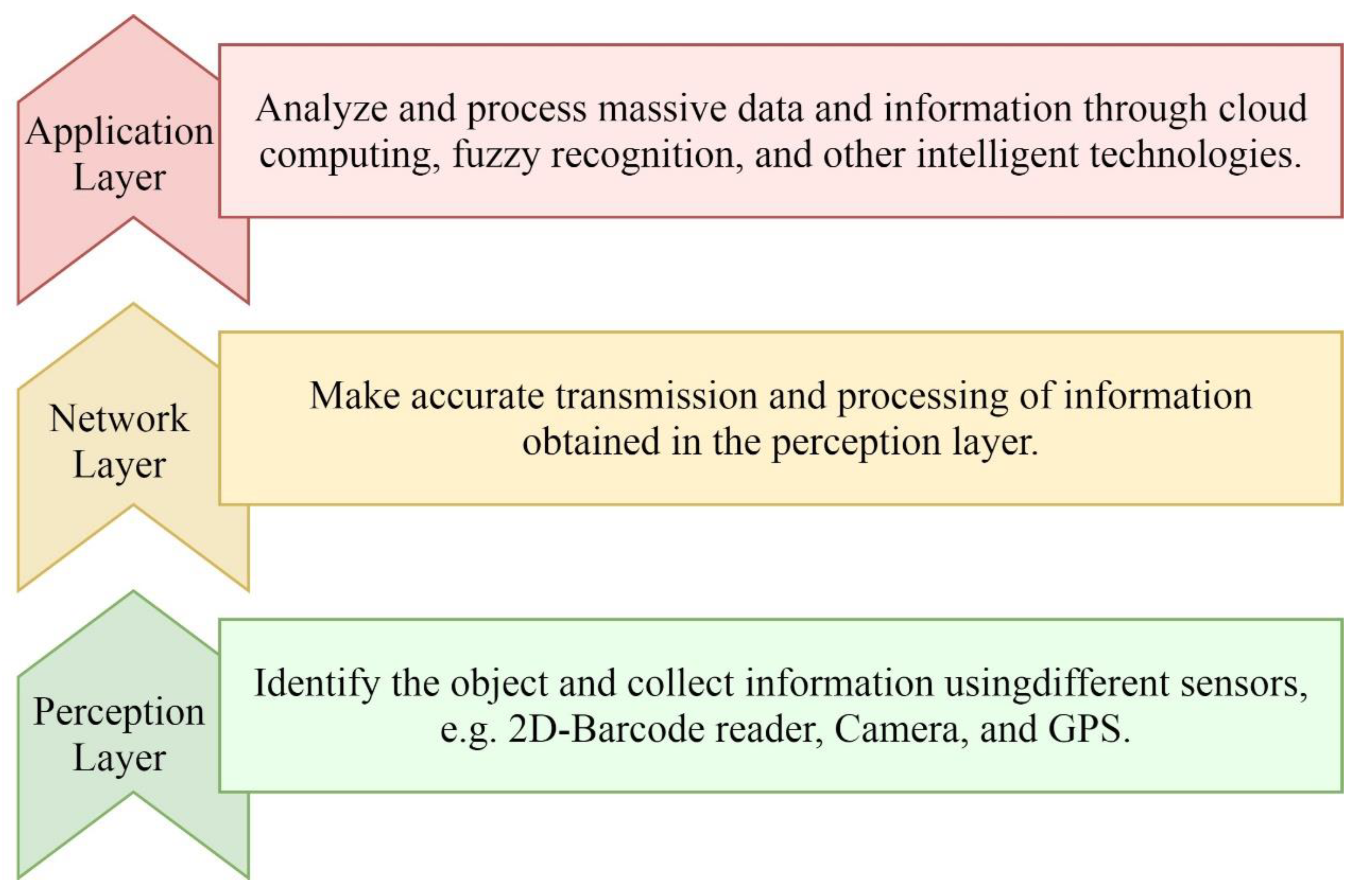

4.2. Smart City Architecture

4.3. Domains and Applications of a Smart City

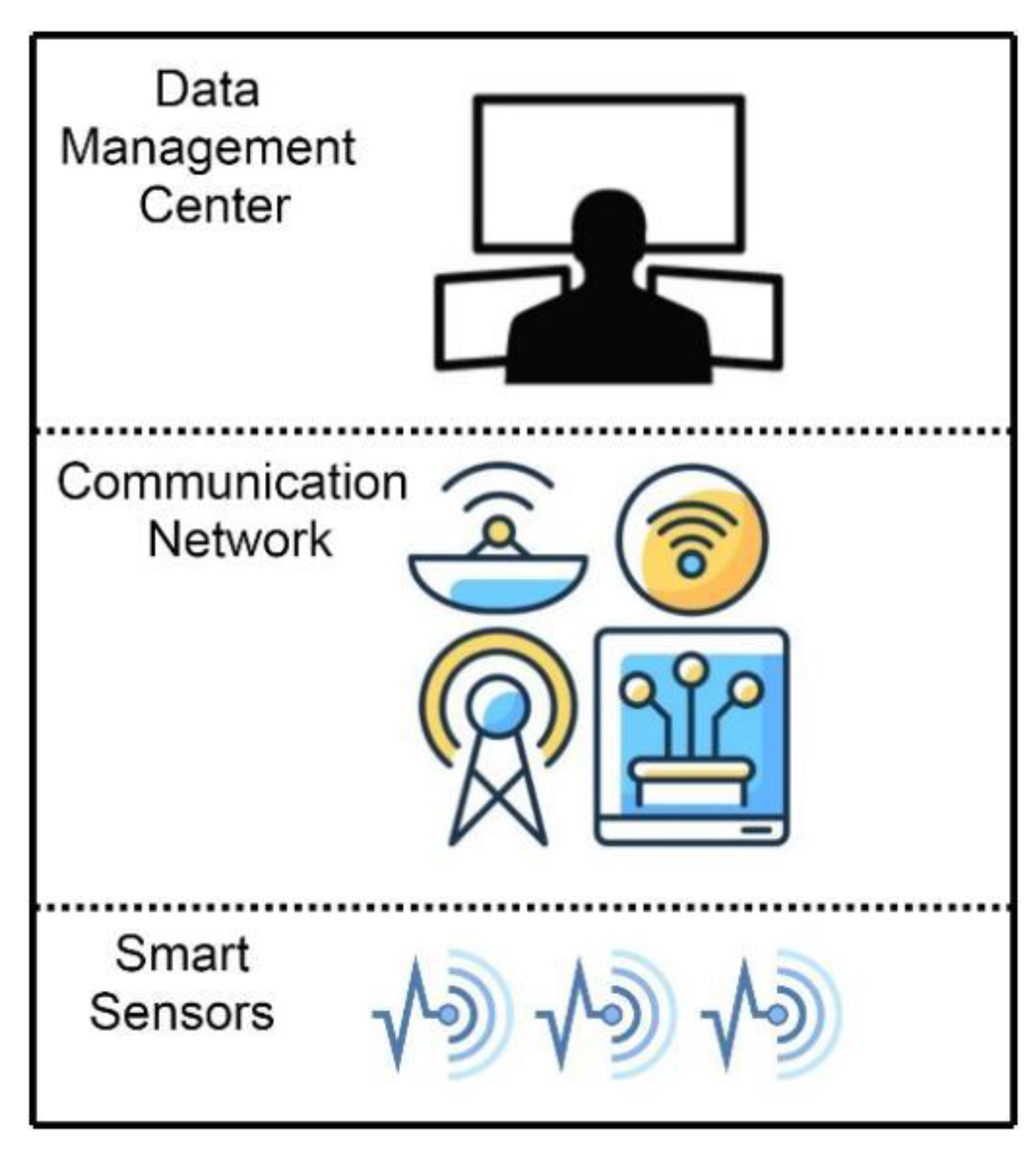

5. The Concept of Smart Metering Infrastructure

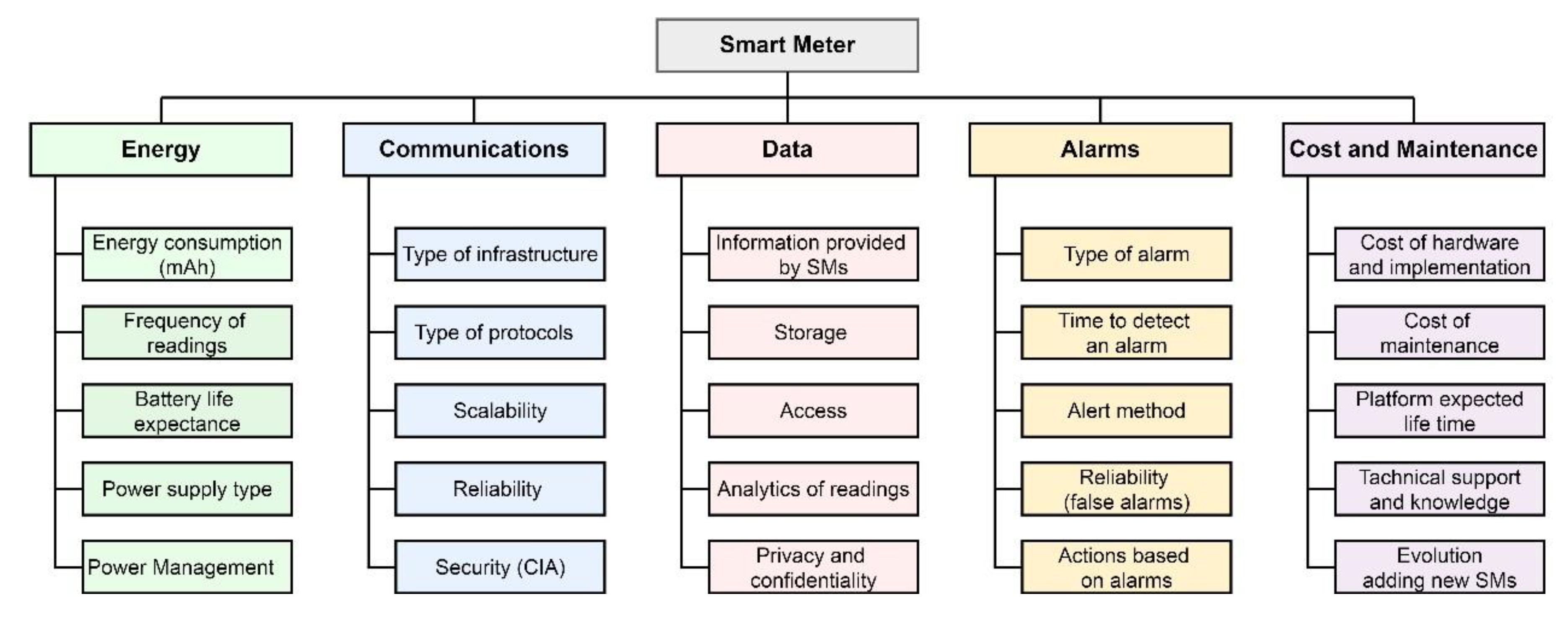

5.1. Smart Meters (SMs)

5.2. Data Management Center (DMC)

- Data Center Infrastructure: The physical facility that houses the primary system along with auxiliary systems such as backup power supplies, ventilation, and alarm systems.

- Servers: Hardware that processes the incoming data.

- Storage Systems: Resource used to store data and enable connection with other system components.

- Database Systems: Software tools used for analyzing stored data.

- Virtualization Systems: Technologies that enhance computing resource utilization and optimize storage management.

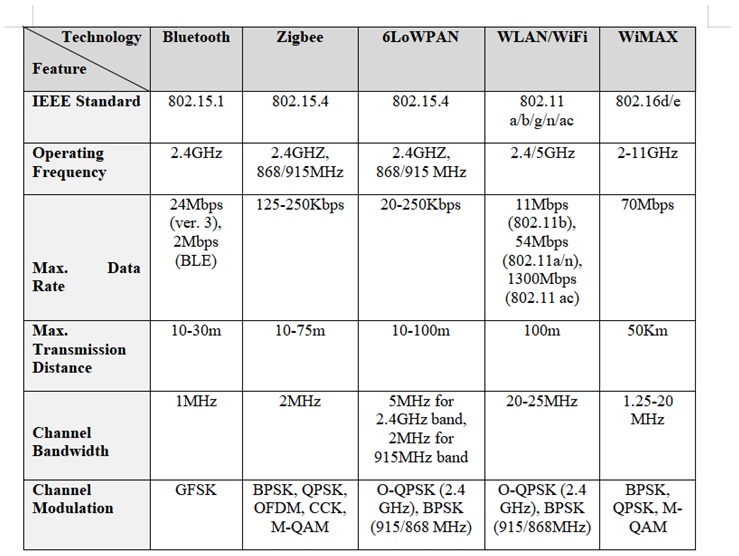

5.3. Communication Structure

5.4. Opportunities for UAVs as Part of SMI

6. SMIs Issues: Privacy, Security, and Policy Issues

6.1. Privacy

6.2. Security

6.3. Policy Issues

7. Challenges in Smart Meters Infrastructure

- Cost: The expenses associated with implementing, deploying, and maintaining SMs must be justified by their benefits.

- Privacy Issues: SMIs continue to grapple with data handling and security concerns, particularly in encountering different network attacks.

- Data Analytics: Effective data analysis needs adequate hardware and software, with requirements varying based on the application, data volume, and desired response time [5].

8. Literature Review

General UAV Review

- RP-CDMA: A MAC layer protocol for AANETs, with simulation results demonstrating its effectiveness over classical routing algorithms [33].

- Hybrid Approaches: Studies indicate that while greedy geographic forwarding is effective for densely deployed networks, incorporating methods like face routing may be necessary for 100% reliability in sparse deployments [36].

- Application Domains: AANET applications span a broad range of fields:

- Forest Management: Single aircraft have been used for managing forests in rural environments [73].

- Emergency Networks: In disaster scenarios, UAVs can establish emergency wireless networks, overcoming spatial and environmental constraints thanks to their mobility and flexibility [74].

- Delivery Services: UAVs are also applied in delivery contexts—indoors (e.g., offices or factories [78]) and outdoors (e.g., postal services [79], pizza [80], beer [81]). They are integral to urban package delivery (e.g., Amazon [82]) and rural logistics (e.g., Matternet [83]). Various delivery schemes and routing approaches have been proposed [84], including a hybrid delivery scheme designed to dynamically control and reduce air traffic based on current operational conditions.

9. UAV as a Platform in Smart Cities Review

| Paper Title | Objective | Methodology | Conclusion | Future Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAV-Based System for Indoor Human Localization (2018) [87] | Experimentally testing external localization of individuals in enclosed spaces. | A piloted UAV equipped with Ultra-Wideband (UWB) radio technology. | The proposed system offers high mobility and simultaneously tracks the positions of team members. | Deploying the proposed technique in real-world applications and incorporating 3D position estimation for moving people. |

| Swarm of Quadcopters for Search Operations (2019) [89] | Finding a missing person within a 10 km radius by determining precise coordinates. | Utilizing a Pixhawk 4 flight controller, multispectral cameras, thermal imaging, and YOLO CNN running on Nvidia Jetson TX2 at the operator’s end. | The system successfully detected individuals and navigated obstacles during collision avoidance tests. | Enabling onboard video processing on UAVs and testing UAVs as radio relays for communication and navigation. |

| MUSCOP: A Mission-Based UAV Swarm Coordination Protocol (2020) [92] | Introducing a new protocol (MUSCOP) for synchronizing UAV swarms in flight. | Developing a conceptual framework and validating it using the ArduSim simulator. | Achieves stable swarm formation, high resilience to channel losses, and scalable performance. | Implementing the protocol across multiple computing systems and optimizing swarm takeoff to minimize collisions. |

| UAV-Based Network and Methods for COVID-19 Response (2021) [94] | Investigating UAV-based solutions for COVID-19 scenarios and proposing an architecture for pandemic management in simulations and real-world applications. | Simulation: UAVs gather data from wearable sensors. Real-world: A piloted drone equipped with a thermal camera scans individuals and sanitizes areas when infection is detected. | Real-world: The approach enables rapid large-area COVID-19 testing. Simulation: Thermal imaging effectively identifies individuals in COVID-19 scenarios. | Implementing indoor screening with multiple mini-drones for scenarios where individuals cannot travel for testing. Testing drone endurance for prolonged indoor operations. |

| Micro Indoor-Drones (MINs) for First Responder Localization (2021) [88] | Assisting SAR operations by tracking FRs inside buildings without GNSS access. | Establishing an indoor UWB network for precise FR localization. | MINs effectively address GNSS-denied localization challenges, enabling accurate FR tracking indoors. | Developing swarm algorithms to facilitate self-deployment of MINs. |

| Drone Swarm Mission Planning and Execution in Hostile Environments (2021) [95] | Designing swarm route planning strategies and detecting hazardous objects. | Route planning via MILP and object detection using EO/IR camera images, SAR, YOLO CNN, and rule-based classification. | The developed detection and classification algorithms are compatible with lightweight mobile platforms and UAV systems. | Adapting mission strategies when detecting threats. Comparing drone-captured images with digital maps for precise localization. |

| Conceptual Framework for Drone Swarms in Fire Suppression (2021) [91] | Utilizing UAV swarms to minimize human risks in wildfires by simulating rainfall effects. | Employing a GD-40X drone, which communicates with a DMC via 4G/5G and autonomously returns for battery replacement and refueling. | Effective implementation requires advanced technology, necessitating further research. | Investigating the impact of rainfall on aircraft, studying UAV resistance to wind and high temperatures, and designing hybrid UAVs with increased payload capacity. |

| Adaptive and Resilient Swarm Management Model (2021) [93] | Enhancing swarm robustness and scalability through reconfigurable formations and fault tolerance. | Establishing a scalable and reliable framework, validated via the ArduSim simulator. | Ensures effective failure handling, minimizes collision risks during reconfiguration, and is applicable across diverse environments. | Exploring AI-based collision avoidance techniques and evaluating UAV integration into swarms during flight. |

10. Findings and Analysis

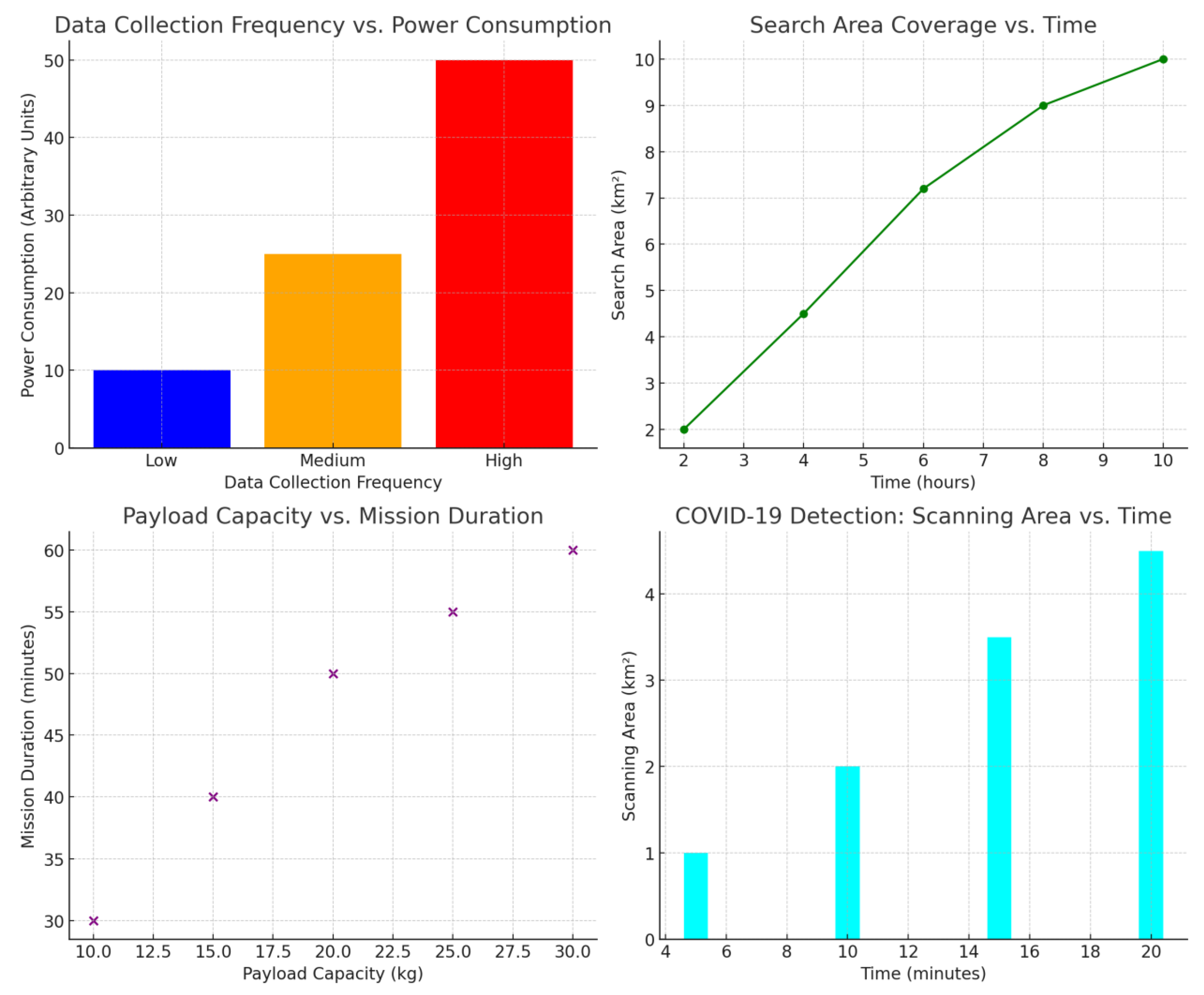

10.1. Smart Metering Infrastructure (SMI) Performance

10.2. UAV-Assisted Smart Metering and Surveillance

10.3. UAVs in Public Health and Security

- The system successfully scanned a 2 km² area in approximately 10 minutes, demonstrating its efficiency in rapidly identifying potential cases.

- The drone-based scanning method significantly reduced human contact risks, making it a viable tool for high-density urban environments.

11. Conclusions

References

- Czichos, H.; Saito, T.; Smith, L.E., Springer handbook of metrology and testing, 2nd edition ed.: Springer Science & Business Media, 2011.

- Aleem, S.A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Zobaa, A.F.; Bansal, R., Decision Making Applications in Modern Power Systems: Academic Press, 2019.

- Hurson, A.R., Advances in Computers vol. 116: Academic Press, 2020.

- Lloret, J.; Tomas, J.; Canovas, A.; Parra, L. An integrated IoT architecture for smart metering. IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 54, pp. 50-57, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ibhaze, A.E.; Akpabio, M.U.; Akinbulire, T.O. A review on smart metering infrastructure. Int. J. Energy Technology and Policy, vol. 16, p. 277, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.R.; Zikria, Y.B.; Rehman, S.U.; Shahzad, F.; Jalil, Z. Future Smart Cities: Requirements, Emerging Technologies, Applications, Challenges, and Future Aspects. 2021.

- Mohammed, F.; Idries, A.; Mohamed, N.; Al-Jaroodi, J.; Jawhar, I. UAVs for smart cities: Opportunities and challenges. in 2014 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), 2014, pp. 267-273.

- Khan, M.A.; Alvi, B.A.; Safi, A.; Khan, I.U. Drones for good in smart cities: a review. in International conference on electrical, electronics, computers, communication, mechanical and computing (EECCMC), 2018.

- Talari, S.; Shafie-Khah, M.; Siano, P.; Loia, V.; Tommasetti, A.; Catalão, J.P. A review of smart cities based on the internet of things concept. Energies, vol. 10, p. 421, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Eremia, M.; Toma, L.; Sanduleac, M. The smart city concept in the 21st century. Procedia Engineering, vol. 181, pp. 12-19, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Höjer, M.; Wangel, J. Smart sustainable cities: definition and challenges. in ICT innovations for sustainability, ed: Springer, 2015, pp. 333-349.

- Morris, A.S. Measurement and instrumentation principles. ed: IOP Publishing, 2001.

- Cagno, E.; Micheli, G.J.; Di Foggia, G. Smart metering projects: an interpretive framework for successful implementation. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pitì, A.; Bettenzoli, E.; De Min, M.; Schiavo, L.L. Smart metering: an evolutionary perspective. Paper prepared as application to, 2016.

- Mohassel, R.R.; Fung, A.; Mohammadi, F.; Raahemifar, K. A survey on advanced metering infrastructure. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, vol. 63, pp. 473-484, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, K.W.; Abdalkafor, A.S.; Nassar, A.M. Smart city applications: A survey. in Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, 2019, pp. 1-4.

- Bellini, P.; Nesi, P.; Pantaleo, G. IoT-enabled smart cities: A review of concepts, frameworks and key technologies. Applied Sciences, vol. 12, p. 1607, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Heng, T.M.; Low, L. The intelligent city: Singapore achieving the next lap: Practitoners forum. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 5, pp. 187-202, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Abadía, J.J.P.; Walther, C.; Osman, A.; Smarsly, K. A systematic survey of Internet of Things frameworks for smart city applications. Sustainable Cities and Society, p. 103949, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Law, K.H.; Lynch, J.P. Smart city: Technologies and challenges. IT Professional, vol. 21, pp. 46-51, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Hollands, R.G. Will the real smart city please stand up?: Intelligent, progressive or entrepreneurial?. in The Routledge companion to smart cities, ed: Routledge, 2020, pp. 179-199.

- Kebotogetse, O.; Samikannu, R.; Yahya, A. Review of key management techniques for advanced metering infrastructure. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, vol. 17, p. 15501477211041541, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tsantilas, S.; Spandonidis, C.; Giannopoulos, F.; Galiatsatos, N.; Karageorgiou, D.; Giordamlis, C. A Comparative Study of Wireless Communication Protocols in a Computer Vision System for improving the Autonomy of the Visually Impaired. Journal of Engineering Science & Technology Review, vol. 13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lipošćak, Z.; Bošković, M. Survey of smart metering communication technologies. in Eurocon 2013, 2013, pp. 1391-1400.

- Manju, P.; Pooja, D.; Dutt, V. Drones in smart cities. AI and IoT-Based Intelligent Automation in Robotics, pp. 205-228, 2021.

- Ismael, G.R.J.; Gabriel, G.S.J. A SURVEY ON SMART METERING SYSTEMS USING HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION. Congr. Int. en Ing. Electrónica. Mem. ELECTRO, vol. 42, pp. 78-82, 2020.

- Custers, B. Drones here, there and everywhere introduction and overview. in The future of drone use, ed: Springer, 2016, pp. 3-20.

- Yenne, B., Attack of the drones: a history of unmanned aerial combat: Zenith Imprint, 2004.

- Clarke, R. Understanding the drone epidemic. Computer Law & Security Review, vol. 30, pp. 230-246, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.X.; Doshi, S.; Jadhav, S.; Henkel, D.; Thekkekunnel, R.-G. A full scale wireless ad hoc network test bed. in Proc. of International Symposium on Advanced Radio Technologies, Boulder, CO, 2005, pp. 50-60.

- Johnson, D.B.; Maltz, D.A. Dynamic source routing in ad hoc wireless networks. in Mobile computing, ed: Springer, 1996, pp. 153-181. [CrossRef]

- Khare, V.R.; Wang, F.Z.; Wu, S.; Deng, Y.; Thompson, C. Ad-hoc network of unmanned aerial vehicle swarms for search & destroy tasks. in 2008 4th International IEEE Conference Intelligent Systems, 2008, pp. 6-65-6-72.

- Vey, Q.; Pirovano, A.; Radzik, J. Performance analysis of routing algorithms in AANET with realistic access layer. in International Workshop on Communication Technologies for Vehicles, 2016, pp. 175-186.

- Hyland, M.; Mullins, B.E.; Baldwin, R.O.; Temple, M.A. Simulation-based performance evaluation of mobile ad hoc routing protocols in a swarm of unmanned aerial vehicles. in 21st International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops (AINAW’07), 2007, pp. 249-256.

- Mahmoud, M.S.B.; Larrieu, N. An ADS-B based secure geographical routing protocol for aeronautical ad hoc networks. in 2013 IEEE 37th annual computer software and applications conference workshops, 2013, pp. 556-562.

- Shirani, R.; St-Hilaire, M.; Kunz, T.; Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Lamont, L. The performance of greedy geographic forwarding in unmanned aeronautical ad-hoc networks. in 2011 Ninth Annual Communication Networks and Services Research Conference, 2011, pp. 161-166.

- Hadiwardoyo, S.A.; Dricot, J.-M.; Calafate, C.T.; Cano, J.-C.; Hernandez-Orallo, E.; Manzoni, P. UAV mobility model for dynamic UAV-to-car communications. in Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Symposium on Performance Evaluation of Wireless Ad Hoc, Sensor, & Ubiquitous Networks, 2019, pp. 1-6.

- Nawaz, H.; Ali, H.M. A study of mobility models for UAV communication networks. 3c Tecnología: glosas de innovación aplicadas a la pyme, vol. 8, pp. 276-297, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bettstetter, C.; Hartenstein, H.; Pérez-Costa, X. Stochastic properties of the random waypoint mobility model. Wireless networks, vol. 10, pp. 555-567, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Biomo, J.-D.M.M.; Kunz, T.; St-Hilaire, M. An enhanced Gauss-Markov mobility model for simulations of unmanned aerial ad hoc networks. in 2014 7th IFIP Wireless and Mobile Networking Conference (WMNC), 2014, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Bouachir, O.; Abrassart, A.; Garcia, F.; Larrieu, N. A mobility model for UAV ad hoc network. in 2014 international conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS), 2014, pp. 383-388.

- Kuiper, E.; Nadjm-Tehrani, S. Mobility models for UAV group reconnaissance applications. in 2006 International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Communications (ICWMC’06), 2006, pp. 33-33.

- Sánchez-García, J.; García-Campos, J.M.; Toral, S.; Reina, D.; Barrero, F. A self organising aerial ad hoc network mobility model for disaster scenarios. in 2015 international conference on developments of E-systems engineering (DeSE), 2015, pp. 35-40.

- Chmaj, G.; Selvaraj, H. Distributed processing applications for UAV/drones: a survey. in Progress in Systems Engineering, ed: Springer, 2015, pp. 449-454.

- Bekmezci, I.; Sahingoz, O.K.; Temel, Ş. Flying ad-hoc networks (FANETs): A survey. Ad Hoc Networks, vol. 11, pp. 1254-1270, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, L.; Jain, R.; Vaszkun, G. Survey of important issues in UAV communication networks. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 18, pp. 1123-1152, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.; Kim, K.-I. A survey on three-dimensional wireless ad hoc and sensor networks. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, vol. 10, p. 616014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Nayak, A. ACPM: An associative connectivity prediction model for AANET. in 2016 Eighth International Conference on Ubiquitous and Future Networks (ICUFN), 2016, pp. 605-610.

- Shen, C.; Chang, T.-H.; Gong, J.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, R. Multi-UAV interference coordination via joint trajectory and power control. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, vol. 68, pp. 843-858, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Alejo, D.; Cobano, J.A.; Heredia, G.; Ollero, A. Collision-free 4D trajectory planning in unmanned aerial vehicles for assembly and structure construction. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems, vol. 73, pp. 783-795, 2014. [CrossRef]

- ARCAS. (2020, 7 April). The ARCAS project. Available: http://www.arcas-project.eu/.

- Srinivasan, S.; Latchman, H.; Shea, J.; Wong, T.; McNair, J. Airborne traffic surveillance systems: video surveillance of highway traffic. in Proceedings of the ACM 2nd international workshop on Video surveillance & sensor networks, 2004, pp. 131-135.

- Ro, K.; Oh, J.-S.; Dong, L. Lessons learned: Application of small uav for urban highway traffic monitoring. in 45th AIAA aerospace sciences meeting and exhibit, 2007, p. 596. [CrossRef]

- Granlund, G.; Nordberg, K.; Wiklund, J.; Doherty, P.; Skarman, E.; Sandewall, E. Witas: An intelligent autonomous aircraft using active vision. in UAV 2000 International Technical Conference and Exhibition, Paris, France, June 2000, 2000.

- Yanmaz, E.; Guclu, H. Stationary and mobile target detection using mobile wireless sensor networks. in 2010 INFOCOM IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops, 2010, pp. 1-5.

- Gil, A.E.; Passino, K.M.; Jr, J.B.C. Stable cooperative surveillance with information flow constraints. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology, vol. 16, pp. 856-868, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.-M.; Kvarnström, J.; Doherty, P.; Burdakov, O.; Holmberg, K. Generating UAV communication networks for monitoring and surveillance. in 2010 11th international conference on control automation robotics & vision, 2010, pp. 1070-1077.

- Schleich, J.; Panchapakesan, A.; Danoy, G.; Bouvry, P. UAV fleet area coverage with network connectivity constraint. in Proceedings of the 11th ACM international symposium on Mobility management and wireless access, 2013, pp. 131-138.

- Corcoran, M. Drone Journalism: Newsgathering applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in covering conflict, civil unrest and disaster. Flinders Univ. Adelaide, vol. 201, p. 202014, 2014.

- Abdelkader, M.; Shaqura, M.; Claudel, C.G.; Gueaieb, W. A UAV based system for real time flash flood monitoring in desert environments using Lagrangian microsensors. in 2013 International conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS), 2013, pp. 25-34.

- Casbeer, D.W.; Beard, R.W.; McLain, T.W.; Li, S.-M.; Mehra, R.K. Forest fire monitoring with multiple small UAVs. in Proceedings of the 2005, American Control Conference, 2005., 2005, pp. 3530-3535.

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, R. Energy minimization for wireless communication with rotary-wing UAV. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 18, pp. 2329-2345, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Augugliaro, F.; Mirjan, A.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M.; D’Andrea, R. Building tensile structures with flying machines. in 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 2013, pp. 3487-3492.

- Lindsey, Q.; Mellinger, D.; Kumar, V. Construction with quadrotor teams. Autonomous Robots, vol. 33, pp. 323-336, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Willmann, J.; Augugliaro, F.; Cadalbert, T.; D’Andrea, R.; Gramazio, F.; Kohler, M. Aerial robotic construction towards a new field of architectural research. International journal of architectural computing, vol. 10, pp. 439-459, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Tomic, T.; Schmid, K.; Lutz, P.; Domel, A.; Kassecker, M.; Mair, E., et al. Toward a fully autonomous UAV: Research platform for indoor and outdoor urban search and rescue. IEEE robotics & automation magazine, vol. 19, pp. 46-56, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Waharte, S.; Trigoni, N.; Julier, S. Coordinated search with a swarm of UAVs. in 2009 6th ieee annual communications society conference on sensor, mesh and ad hoc communications and networks workshops, 2009, pp. 1-3.

- Berger, J.; Happe, J. Co-evolutionary search path planning under constrained information-sharing for a cooperative unmanned aerial vehicle team. in IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, 2010, pp. 1-8.

- Goodrich, M.A.; Morse, B.S.; Gerhardt, D.; Cooper, J.L.; Quigley, M.; Adams, J.A., et al. Supporting wilderness search and rescue using a camera-equipped mini UAV. Journal of Field Robotics, vol. 25, pp. 89-110, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Molina, P.; Colomina, I.; Vitoria, T.; Freire, P.; Skaloud, J.; Kornus, W., et al. CLOSE-SEARCH: ACCURATE AND SAFE EGNOS-SOL NAVIGATION FOR UAV-BASED LOW-COST SAR OPERATIONS. 2011.

- Ghafoor, S.; Sutton, P.D.; Sreenan, C.J.; Brown, K.N. Cognitive radio for disaster response networks: survey, potential, and challenges. IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 21, pp. 70-80, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Puri, A. A survey of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) for traffic surveillance. Department of computer science and engineering, University of South Florida, pp. 1-29, 2005.

- Hormigo, T. A micro-UAV system for forest management. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Lu, W.; Sheng, M.; Chen, Y.; Tang, J.; Yu, F.R., et al. UAV-assisted emergency networks in disasters. IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 26, pp. 45-51, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kunovjanek, M.; Wankmüller, C. Containing the COVID-19 pandemic with drones-Feasibility of a drone enabled back-up transport system. Transport Policy, vol. 106, pp. 141-152, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Project, C.2006, 8 May). Real-time coordination and control of multiple heterogeneous unmanned aerial vehicles. Available: http://www.comets-uavs.org/.

- Sujit, P.; Ghose, D. Search using multiple UAVs with flight time constraints. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. 40, pp. 491-509, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.2020, 3 April). CARGO DRONES: THE FUTURE OF PARCEL DELIVERY. Available: https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Point-of-View/Cargo-drones-.

- DHL. (2020, 29 March). UNMANNED AERIAL VEHICLES Ready for Take-off? Available: https://www.dhl.com/global-en/home/insights-andinnovation/thought-leadership/trend-reports/unmanned-aerialvehicles.

- html.

- Cargo, U.2020, 2 April). Pizza Pie in the Sky! – A Brief History of the Goal to Use Drones to Deliver Pizzas. Available: http://unmannedcargo.org/pizza-pie-in-the-sky-the-use-of-dronesto-deliver-pizzas-commercially/.

- ADVERTISER, T.M.2020, 5 April). BrewDog ‘exploring drone delivery’ in UK. Available: https://www.morningadvertiser.co.uk/Article/2020/06/17/BrewDog-exploring-drone-delivery-in-UK.

- D’Andrea, R. Guest editorial can drones deliver?. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, vol. 11, pp. 647-648, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, E. Matternet wants to deliver meds with a network of quadrotors. Automaton blog on IEEE Spectrum, 2011.

- Kuru, K.; Ansell, D.; Khan, W.; Yetgin, H. Analysis and optimization of unmanned aerial vehicle swarms in logistics: An intelligent delivery platform. Ieee Access, vol. 7, pp. 15804-15831, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-I.; Hyeon, S.; Yang, S.; Yi, J. Development of simulator for aircraft ad hoc networks. in 2011 IEEE/AIAA 30th Digital Avionics Systems Conference, 2011, pp. 5B1-1-5B1-8.

- Qi, F.; Zhu, X.; Mang, G.; Kadoch, M.; Li, W. UAV network and IoT in the sky for future smart cities. IEEE Network, vol. 33, pp. 96-101, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, P.; Kraszewski, T. Drone-based system for localization of people inside buildings. in 2018 14th International Conference on Advanced Trends in Radioelecrtronics, Telecommunications and Computer Engineering (TCSET), 2018, pp. 46-51.

- Paliotta, C.; Ening, K.; Albrektsen, S.M. Micro indoor-drones (mins) for localization of first responders. 2021.

- Meshcheryakov, R.; Trefilov, P.; Chekhov, A.; Diane, S.; Rusakov, K.; Lesiv, E., et al. An application of swarm of quadcopters for searching operations. IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 52, pp. 14-18, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.; Kothari, A.; Gupta, V. YOLO based human action recognition and localization. Procedia computer science, vol. 133, pp. 831-838, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ausonio, E.; Bagnerini, P.; Ghio, M. Drone swarms in fire suppression activities: a conceptual framework. Drones, vol. 5, p. 17, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Fabra, F.; Zamora, W.; Reyes, P.; Sanguesa, J.A.; Calafate, C.T.; Cano, J.-C., et al. MUSCOP: Mission-based UAV swarm coordination protocol. IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 72498-72511, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wubben, J.; Fabra, F.; Calafate, C.T.; Cano, J.-C.; Manzoni, P. A novel resilient and reconfigurable swarm management scheme. Computer Networks, vol. 194, p. 108119, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.; Singh, H.; Naugriya, S.G.; Gill, S.S.; Buyya, R. A drone-based networked system and methods for combating coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 115, pp. 1-19, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Siemiatkowska, B.; Stecz, W. A framework for planning and execution of drone swarm missions in a hostile environment. Sensors, vol. 21, p. 4150, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.I. Design, implementation & optimization of an energy harvesting system for VANETs’ road side units (RSU). IET Intelligent Transport Systems, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 298-307, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.I. An efficient simulation methodology of networked industrial devices. in Proc. 5th Int. Multi-Conference on Systems, Signals and Devices, 2008, pp. 1-6.

- Ali, Q.I. Security issues of solar energy harvesting road side unit (RSU). Iraqi Journal for Electrical & Electronic Engineering, vol. 11, no. 1, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.I. Securing solar energy-harvesting road-side unit using an embedded cooperative-hybrid intrusion detection system. IET Information Security, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 386-402, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Q. Design & Implementation of High-Speed Network Devices Using SRL16 Reconfigurable Content Addressable Memory (RCAM). Int. Arab. J. e Technol., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 72-81, 2011.

- Alhabib, M.H.; Ali, Q.I. Internet of autonomous vehicles communication infrastructure: a short review. Diagnostyka, vol. 24, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.I. Realization of a robust fog-based green VANET infrastructure. IEEE Systems Journal, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 2465-2476, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.I.; Jalal, J.K. Practical design of solar-powered IEEE 802.11 backhaul wireless repeater. in Proc. 6th Int. Conf. on Multimedia, Computer Graphics and Broadcasting, 2014.

|

| Paper Title | Objective | Methodology | Conclusion | Future Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development of a Simulator for Aircraft Ad Hoc Networks [85] | Improving current simulation tools to achieve more reliable AANET outcomes. | Enhancing existing AANET simulation frameworks. | Identified key obstacles in simulator development. | Proposed potential improvements and additional functionalities to refine current simulators. |

| Secure Geographical Routing Protocol for AANET using ADS-B [35] | Addressing security challenges in AANET routing. | Combining Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) with GPSR. | The proposed protocol provides cost-effective cryptographic solutions to protect aircraft position data and transmitted packets. | Strengthening the hybrid ADS-B/GPSR security model by integrating additional security mechanisms. |

| UAV Ad Hoc Network Mobility Model [41] | Investigating real-world AANET mobility challenges. | Paparazzi Mobility Model (PPRZM) and Random Waypoint (RWP) model. | PPRZM exhibits behavior closer to actual Paparazzi movement patterns compared to RWP. | Evaluating PPRZM in diverse scenarios and benchmarking it against other UAV mobility models. |

| Self-Organizing Aerial Ad Hoc Network for Disaster Response [43] | Developing a flexible airborne network for disaster relief. | Utilizing Jaccard distance for mobility modeling. | The mobility model enables drones to disperse effectively from a central disaster point, improving coverage for affected individuals. | Applying computational intelligence techniques to optimize Jaccard threshold selection for maximizing victim coverage. |

| Associative Connectivity Prediction Model (ACPM) for AANET [48] | Reducing network setup time and improving self-healing capabilities. | FCM clustering approach. | ACPM operates within a hybrid AANET topology to enhance network awareness, monitor end-to-end connectivity, and assist network agents. | Increasing network stability by improving aircraft connectivity levels. |

| Optimizing UAV Swarm Logistics: An Intelligent Delivery Framework [84] | Analyzing and optimizing UAV delivery systems. | Implementing dynamic multiple assignments in multi-dimensional space (dMAiMD), along with the Hungarian algorithm and Cross-Entropy Monte Carlo methods. | The Cross-entropy Monte Carlo method is introduced as a novel approach for determining optimal UAV delivery routes, improving autonomous air traffic control. | Conducting real-world experiments and adopting the Internet of Drones (IoD) technology for a comprehensive cyber-physical delivery framework. |

| UAV and IoT Integration for Future Smart Cities [86] | Establishing a 5G-enabled drone network to address the leader UAV bottleneck issue. | Enhancing leader UAV antenna configurations and leveraging multiple millimeter-wave ground station connections for better handover management. | The proposed architecture manages swarm coordination, navigation, task allocation, and data processing, positioning the leader UAV as a network gateway and control center. | Future research should focus on optimizing the leader UAV’s altitude and trajectory prediction. |

| UAV-Assisted Communication Networks for Disaster Management [74] | Overcoming environmental and spatial communication barriers in disaster scenarios. | Joint Trajectory and Scheduling Optimization. | Deploying drones for emergency communication improves network efficiency during disaster situations. | Further exploration is needed in managing interference and minimizing energy consumption when scaling up drone deployments. |

| Energy-Efficient Wireless Communication with Rotary-Wing UAVs [62] | Minimizing UAV energy consumption while ensuring adequate communication for ground nodes. | Optimizing mission duration, trajectory, and communication scheduling. | The proposed strategy outperforms conventional benchmarks in rotary-wing UAV wireless communication systems. | Future studies should refine trajectory and altitude adjustments and develop more comprehensive power consumption models. |

| Coordinated Multi-UAV Interference Management via Joint Trajectory and Power Control [49] | Mitigating severe cross-link interference in UAV networks. | Joint trajectory and power control (TPC). | The SCA algorithm continuously adapts the UAV’s trajectory and transmission power in each cycle. By using parallel TPC and segment-wise strategies, it enhances network throughput while also cutting down on computation time. | Future research should focus on developing an adaptive UAV framework that switches between spectrum sharing and FDMA with minimal power usage by including multi-antenna ground terminals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).