1. Introduction

With increasing global awareness of environmental sustainability and the urgent need to mitigate climate change, many countries and regions have established carbon neutrality targets [

1]. Renewable organic materials, such as biomass, have attracted attention for their potential to sustainably produce chemicals, fuels, and materials, providing significant economic, environmental, and social benefits[

2]. Perennial ryegrass (

Lolium perenne) is an attractive biomass source due to its adaptability, high yield, and widespread availability. Traditionally, ryegrass has been widely used as animal feed in agriculture [

3]. However, with declining livestock numbers in some regions in Germany, its role as a key silage crop is evolving. Beyond its importance in forage production,

Lolium perenne presents new economic opportunities in the bioeconomy, such as biofuel production and biorefinery applications. This aligns with the findings of Conaghan et al., who identified

Lolium perenne as an excellent choice for silage due to its high dry matter yield and water-soluble carbohydrate (WSC) content, which contribute to effective fermentation and preservation [

4].

Lactic acid, a vital organic acid, is widely used in the chemical, pharmaceutical, and food processing industries. The growing demand for biodegradable polylactic acid (PLA) plastics has amplified the importance of lactic acid as a key raw material. By 2025, the lactic acid market is projected to reach 1.96 megatons, with 90–95% of production originating from biomass fermentation [

5,

6,

7].

Silage is an effective method for preserving animal feed and could be used to produce lactic acid. The core principle of silage is anaerobic fermentation, in which lactic acid bacteria (LAB) convert biomass sugars into lactic acid. This process lowers the pH, inhibits the growth of undesirable microorganisms, and ensures long-term preservation of the biomass [

4]. Research has focused on optimizing lactic acid yield per unit of biomass by manipulating factors such as crop selection, environmental conditions, and silage additives. High concentrations of WSC in silage materials, such as

Lolium perenne, significantly enhance LAB activity and fermentation quality [

8]. Similarly, additives like L-tryptophan improve lactic acid production, fermentation quality, and microbial balance by increasing LAB populations and suppressing undesirable microbes [

9]. Environmental factors, including harvest timing and nitrogen management, also affect WSC content and overall fermentation outcomes [

10]. In conclusion, advances in silage research, such as the development of high-sugar grass cultivars and novel additives, have introduced valuable strategies to enhance lactic acid yields and feed quality.

This study investigates the efficient ensiling of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) for a dedicated production of enantiomerically pure lactate, analyzing the interplay among ensiling duration, pH, buffer selection, and raw material characteristics. Various Lolium perenne varieties were analyzed and compared to identify the most suitable candidates for silage and lactic acid production. During the silage process, concentrations of lactic acid, acetic acid, butyric acid, and ethanol were monitored to identify the optimal silage duration and minimize lactic acid loss due to degradation. Different buffering salts and neutralizing agents were incorporated into the silage process to identify the pH conditions that maximize lactic acid yield and to compare their effects on silage performance. Finally, the optimized silage conditions were applied to evaluate and compare the outcomes of silage from different Lolium perenne varieties, ploidy levels, and harvest times.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

A field experiment was conducted at the Julius Kühn Institute in Braunschweig, Germany. The experimental site is located at an altitude of 80 m above sea level, with an annual precipitation of 617 mm and an average temperature of 9.1 °C. The soil consists of silty sand with a topsoil depth of approximately 30 cm.

To ensure a reliable supply of fresh biomass, several

Lolium perenne varieties with different agronomic characteristics were cultivated in large field plots.

Table 1 presents the samples used for silage optimization, while

Table 2 lists those analyzed for the impact of harvest timing on silage (

Section 3.4). The experiment included two separate harvest dates during each scheduled cut throughout the year to assess how harvest timing affects biomass yield and quality, and therefore lactic acid production. After harvest, the biomass samples were immediately vacuum-sealed to preserve their composition and shipped overnight via express delivery for further processing and analysis. Upon arrival at FH Aachen, samples were immediately stored at -21 °C. Before use, they were thawed at room temperature and prepared for experimentation.

2.2. Extraction of Silage Products

The mass content of silage products was measured through sample extraction, followed by HPLC analysis. Approximately 10 g of the grass sample was weighed into the blender container (WMF Kult X Mix & Go) for silage product extraction. Deionized water was added to the container. The water was added until the total mass of the grass and water reached approximately 50 g. The grass sample was blended for 1 minute until it reached a slurry-like consistency. The slurry was then diluted with Deionized water to a total mass of approximately 100 g and left to extract for at least 1 hour. After extraction, the slurry mixture was vacuum-filtered to separate the solid material. The extract was transferred to 2 ml centrifuge tubes and centrifuged. The Eppendorf 5415 D centrifuge (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) was operated at 10,000 rcf for 5 minutes. Finally, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 μm polyethersulfone membrane filter (Wicom Germany GmbH, Germany).

2.3. Measurement of Water-Soluble Carbohydrates

Water-soluble carbohydrates (WSC) were measured using Near Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) in this study. At least 500 g of fresh samples were collected from each field plot, chopped for dry matter (DM) analysis, and ground. Samples were dried at 60 °C for 48 hours in a Memmert oven (Schwabach, Germany) and uniformly milled using a Brabender cutting mill (Anton Paar TorqueTec, Duisburg, Germany). WSC content was then analyzed using a Foss NIRSystem 5000 spectrometer (Foss GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) with a wavelength range of 1100 – 2498 nm and a 2 nm resolution.

2.4. Density of the Extract

The extract liquid, filtered through a 0.2 μm membrane filter, was transferred into a 25 mL pycnometer (Carl Roth GmbH + Co. KG, Germany). An XA204DR analytical balance (Mettler-Toledo, USA), with a precision of 0.1 mg, was used to weigh the empty pycnometer and the pycnometer filled with the extract liquid. The density of the extract liquid was calculated from the measured weights.

2.5. Measurement of Moisture Content

The dry matter content (DM%) of fresh and ensiled

Lolium perenne samples was measured using a KERN DBS 60-3 moisture analyzer (Balingen-Frommern, Germany), with a precision of 0.001 g. Approximately 1 g of the sample was evenly distributed on the weighing. The drying process was conducted at 105 °C and continued until the mass change was less than 0.03% within 30 seconds. The moisture content (MC%) was recorded and converted to dry matter content (DM%) using Eq. 1.

2.6. Calculation of Mass Concentration of Silage Products and Lactic Acid Yield

The concentrations measured by HPLC (were expressed in “g/L” and needed to be converted into mass concentration ( in “g/kg DM” to allow comparison with reference values. Lactic acid yield refers to the mass concentration of lactic acid produced during the silage process. The conversion process is outlined in the following steps.

2.6.1. Dry Mass of the Sample

The dry mass (

) of the

Lolium perenne sample can be calculated (Equation 2) using the dry matter content (DM%) and the wet mass of the sample (

):

2.6.2. Mass of Substance in Silage Products

The mass of substance

in silage products (

) can be calculated (Equation 3) from the concentration obtained through HPLC (

) and the volume of the extract (

):

2.6.3. Volume of the Extract

The volume of the extract (

) can be calculated (Equation 4) from the extract mass (

) and density (

). The mass of the extract (

) is the total mass of the slurry mixture (

) minus the dry matter content (

).

2.6.4. Mass Concentration of Silage Products

The mass concentration of the silage product (

is defined (Equation 5) as the ratio of the silage product’s mass (

) to the total sample dry mass (

):

2.7. Preparation of Pressed Juice

A benchtop screw press (8500 S, Luba, Bad Homburg, Germany) was used for the preparation of pressed Juice. The grass was initially cut into approximately 10 cm-long pieces before being fed into the press. The pressed juice and press cake were collected separately for further processing. Both the pressed juice and press cake were stored at -18 °C until needed for subsequent use.

2.8. pH Measurement of Pressed Juice

Before each measurement, the measuring electrode was sterilized using a disinfectant (Paul Hartmann AG, Bacillol®) and rinsed with deionized water. The pressed juice was evenly divided into three 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and analyzed with a pH meter (LLG-Labware, LLG-pH Meter 5).

2.9. Silage Production

Previously stored Lolium perenne grass was thawed at room temperature before being used for silage production to obtain lactic acid. Two different silage methods were applied in this study and are introduced in the following sections.

2.9.1. Silage in Vacuum Bags

For each trial, 50 g of wet mass (

) of the selected grass was placed into a vacuum bag (

Figure 1 a). 10 mL of a silage additive (diluted with deionized water 1:500) was added to the bag. The additive contained a blend of the bacterial strains

Lactobacillus plantarum,

Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and

Pediococcus pentosaceus (Lactosan, Kapfenberg, Austria). After adding the silage additive, the contents were briefly mixed and sealed using a vacuum sealer (VMKH-300, GGM-Gastro, Ochtrup, Germany). The sealed bags were placed in airtight plastic buckets (

Figure 1 b), purged with nitrogen gas to maintain an anaerobic environment, and then sealed. Silage was carried out at room temperature for 75 days. During sampling, designated bags or trials (

Figure 1 a)were removed from the buckets (

Figure 1 b), and the buckets were subsequently refilled with nitrogen gas. To maintain the nitrogen atmosphere and anaerobic conditions inside the buckets, nitrogen was replenished every three days.

2.9.2. Ensiling in Bottles

In this experiment, two different sizes of glass bottles (

Figure 1 c) were used for silage. The first setup utilized a 1 L bottle with 50 g wet mass (

of the selected grass, to which 10 mL of a silage additive (diluted with deionized water at 1:500 v/v) was added. The second setup used a 10 L bottle with 500 g wet mass (

) of the selected grass, and 100 mL of the same silage additive (diluted 1:500 with deionized water) was added. This setup allowed for sampling during the silage process.

The bottle was sealed at the neck using a rubber stopper and cap. To maintain anaerobic conditions, two cannulas of different lengths were inserted through the rubber stopper into the bottle. The longer cannula reached near the bottom of the bottle, enabling nitrogen gas to mix thoroughly with the silage sample and displace oxygen. The shorter cannula vented gas during nitrogen purging to balance internal pressure. Both cannulas were fitted with valves to ensure an airtight seal. After each sampling, nitrogen gas was reintroduced into the bottles to preserve the anaerobic environment. Nitrogen gas was introduced every three days to maintain anaerobic conditions inside the bottle. To prevent fluctuations in ambient laboratory temperature from impacting the experiment, the bottles were kept in an incubator maintained at 37 °C for the 21-day silage process.

2.10. Analysis of Silage Products

High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to quantify fermentation products in the liquid extract samples, specifically lactic acid, acetic acid, butyric acid, and ethanol. The analysis was performed using a Repromer 300 × 8 mm H+ column (Dr. Maisch GmbH, Germany) at 30 °C on an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, USA).The mobile phase comprised 5 mM sulfuric acid in ultrapure water, with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Analyte detection was carried out using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II Refractive Index Detector (Agilent Technologie, USA), maintained at 35 °C. The sample injection volume was 5 µL, with a total chromatographic analysis time of 35 minutes.

2.11. pH Control and Buffers

To evaluate the effect of pH on silage products, experiments were conducted under controlled pH conditions using buffer solutions or neutralizing agents. Buffer solutions were carefully selected to ensure they were non-toxic and non-harmful to microorganisms, which constrained the available options.

The pH levels of the buffers were determined based on sample quantities and the equipment volume used in this part of the experiment. Three pH levels were selected: pH 4.5, pH 6, and pH 7.

2.11.1. Silage at pH 7

To maintain a pH of 7, organic acids produced during the silage process were neutralized. Calcium carbonate (Honeywell Specialty Chemicals Seelze GmbH, Germany) was selected for this purpose due to its suitability for cultivating Lactobacillus and its cost-effectiveness [

12]. The pH 7 group was adjusted with 2.3 g of calcium carbonate, which was suspended in 20 mL of deionized water before being added to the silage bottles to ensure uniform distribution.

2.11.2. Silage at pH 4.5 and pH 6 Using Citrate Buffer

The citrate buffer, comprising citric acid and sodium citrate, was chosen as a promising candidate due to its triprotic nature, offering three

values. This property allows for the preparation of citrate buffers over a wide pH range (pH 3.0 to pH 6.2) [

13]. Moreover, research by Zi et al. (2021) demonstrated that citrate buffer addition enhances lactate yield and improves silage quality [

14]. Citrate buffers were prepared following the protocol in [

13], using citric acid (Honeywell Specialty Chemicals Seelze GmbH, Germany) and sodium citrate dihydrate (Duchefa Biochemie, Netherlands). The pH 4.5 and pH 6 groups were adjusted using 20 mL of 1 M citrate buffer solution.

2.11.3. Silage at pH 6 Using Phosphate Buffer

Considering the importance of raw material costs in industrial applications, phosphate buffer was evaluated as a potential replacement for citrate buffer due to its lower cost. Phosphate buffers were prepared from disodium hydrogen phosphate (Honeywell Specialty Chemicals Seelze GmbH, Germany) and sodium dihydrogen phosphate (Honeywell Specialty Chemicals Seelze GmbH, Germany). The pH 6 group was adjusted using 20 mL of 1 M phosphate buffer solution.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Validation of the Optimal Silage Duration

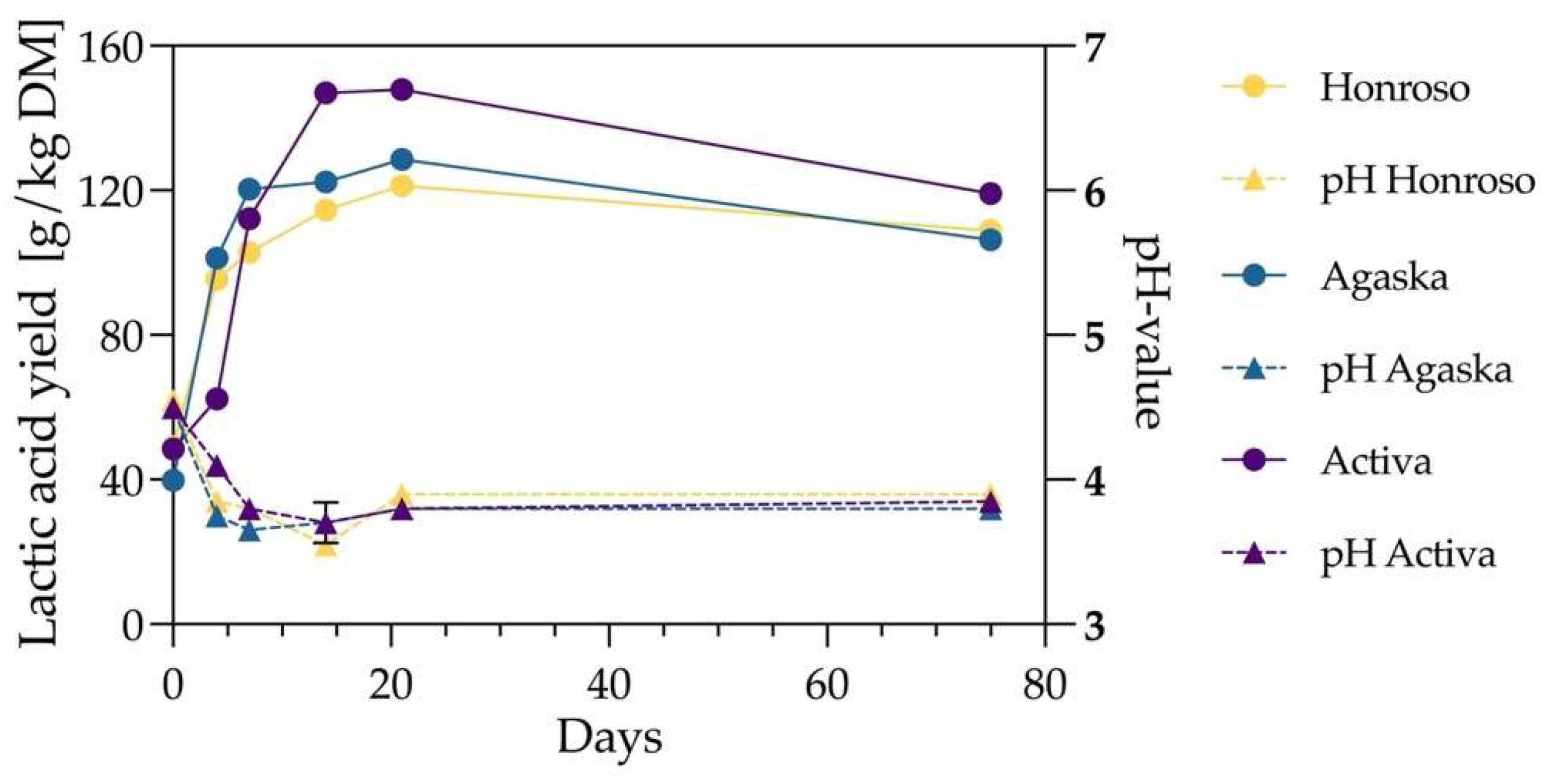

As a preliminary study, three Lolium perenne varieties—Honroso, Agaska, and Activa—were selected for silage production. The objective was to evaluate the lactic acid yield of the selected Lolium perenne varieties at varying silage durations and to determine the optimal silage time. The silage process utilized the vacuum bag method described in Section 0, with a total duration of 75 days. Samples were collected at six time points (0, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 75 days) to analyze lactic acid production and silage pH.

The experimental results showed (

Figure 2) that lactic acid concentrations in the three

Lolium perenne varieties increased most rapidly during the first 14 days of silage, peaking at 21 days. At 21 days, the lactic acid yield reached 148.4 g/kg DM for Activa, 128.4 g/kg DM for Agaska, and 121.0 g/kg DM for Honroso, which produced the least. When comparing the WSC values of the three

Lolium perenne varieties, Activa had the highest WSC content (27.9% DM), followed by Agaska (24.4% DM), while Honroso had the lowest (23.2% DM). This trend aligns with their respective lactic acid yields, further supporting the correlation (p < 0.01) between WSC content and fermentation efficiency. These findings suggest that

Lolium perenne varieties with higher WSC concentrations are more suitable for lactic acid fermentation, as they offer increased substrate availability for microbial conversion, ultimately enhancing lactic acid production. After 21 days, a significant decline in lactic acid content was observed. For instance, Activa showed a 24.2% reduction, decreasing to 119.1 g/kg DM. On average, the lactic acid content across all three samples decreased by 18.8%. The reduction in lactic acid yield between days 21 and 75 was attributed to anaerobic degradation. Heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria (LAB) can convert lactic acid into acetic acid, 1,2-propanediol, and ethanol under acidic conditions [

15]. Although homofermentative LAB were exclusively introduced through the silage additive [

16,

17] the nature of the naturally occurring LAB in the samples before the experiment—whether heterofermentative or homofermentative—remains unknown. Furthermore, even homofermentative LAB have been shown to degrade lactic acid under anaerobic conditions. For instance,

Lactobacillus plantarum, used in this experiment, has been shown to convert lactic acid into acetic acid during extended incubation periods (7–30 days) [

18]. Other strains, such as

Lactobacillus pentosus, also exhibit this capability, and

L. rhamnosus and

Pediococcus pentosaceus are likely contributors to anaerobic lactic acid degradation [

15]. The pH of the three samples reached a minimum of approximately 3.6 by day 14, followed by a slight increase to 3.8 by day 21. Subsequently, the pH remained relatively stable until the silage process concluded at day 75. Based on these findings, subsequent experiments limited the maximum silage duration to 21 days to avoid the adverse effects of lactic acid degradation. Notably, lactic acid was already present in the samples on day 0 of silage, with a pH of approximately 4.5. This showed that the silage process began prior to the start of the experiment. Possible causes include delayed freezing of

Lolium perenne samples after harvesting or inadequate temperature control during transportation. However, these issues were effectively resolved and prevented in subsequent experiments using new batches of samples.

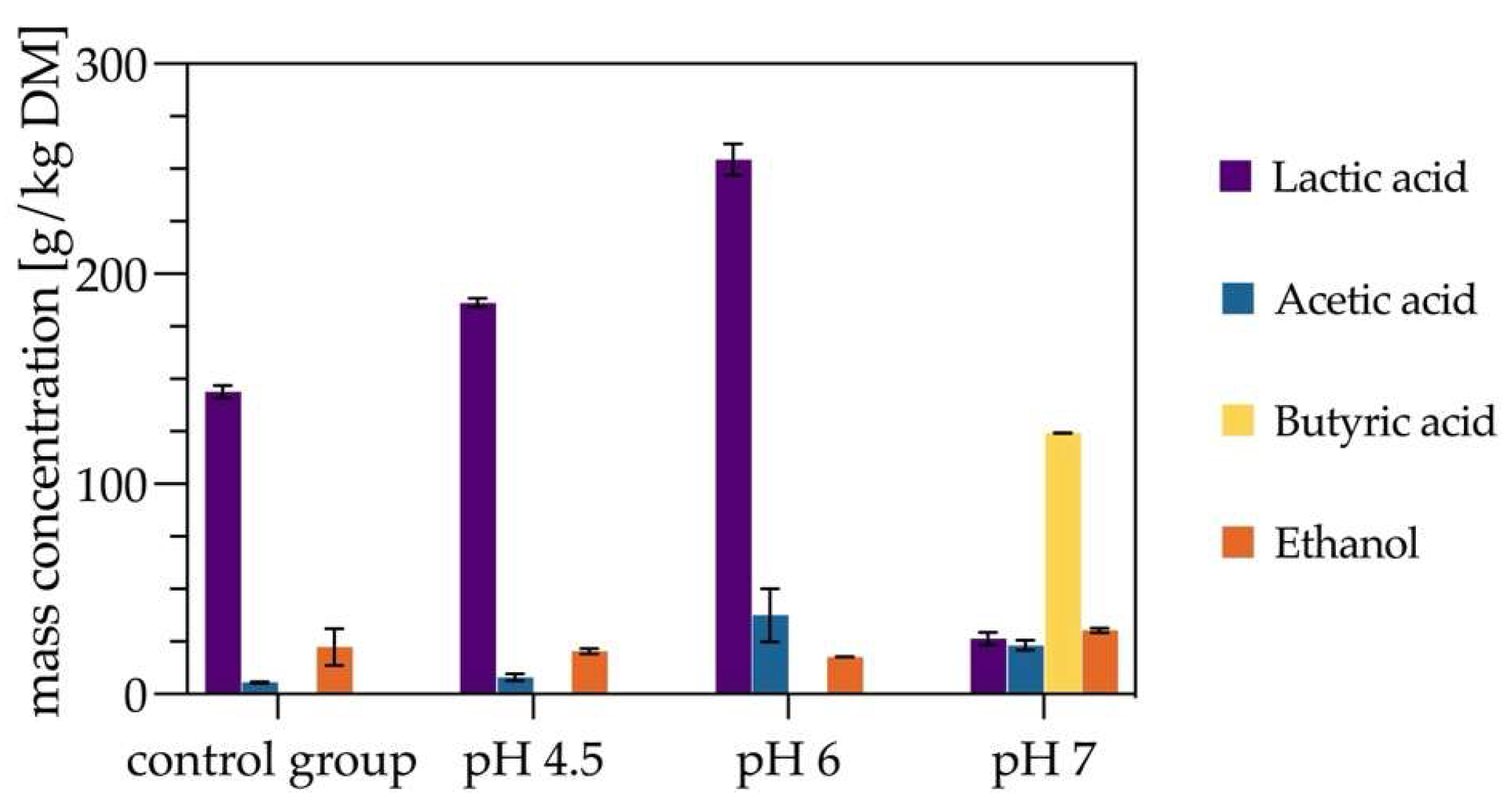

3.2. Evaluating the Effect of pH on Silage Quality

Investigations on the effects of different pH values and various buffering solutions or neutralizing agents on lactic acid outcomes was done with a larger batch of

Lolium perenne variety Arvicola. During the ensiling process, the concentrations of lactic acid, acetic acid, butyric acid, and ethanol in the samples where evaluated. Four silage groups were prepared using the 1 L bottle method described in

Section 2.9.2. The experimental groups included pH 4.5, pH 6, pH 7, and a control group without pH adjustment.

The experimental results demonstrate (

Figure 3) that citrate buffers at pH 4.5 and pH 6 significantly enhanced lactic acid production in silage compared to the control group without buffer addition. At pH 4.5, the lactic acid yield after 21 days was 186.2 g/kg DM, a 27.5% increase over the control group’s yield of 146.1 g/kg DM. At pH 6, the lactic acid yield peaked at 254.4 g/kg DM, marking a 74% increase over the control group. Conversely, with calcium carbonate as a neutralizing agent to maintain pH 7, the lactic acid yield dropped to the lowest value of 26.3 g/kg DM. The pH 6 group exhibited the highest acetic acid concentration at 37.5 g/kg DM, a 710% increase over the control group’s 5.25 g/kg DM. The pH 7 group produced a significant acetic acid concentration of 23.2 g/kg DM, whereas both the pH 4.5 and control groups had concentrations below 10 g/kg DM. Ethanol concentrations in the pH 4.5, pH 6, and control groups remained relatively stable at approximately 20 g/kg DM. However, in the pH 7 group, ethanol concentration was 50% higher than in the other groups, reaching 31 g/kg DM. Notably, butyric acid was detected exclusively in the pH 7 samples and was absent in all other groups. The distinct odor of the pH 7 samples further confirmed the presence of undesirable fermentation by-products. A relatively low pH during silage likely inhibits the growth of non-lactic acid bacteria, reducing competition for lactic acid bacteria and resulting in higher lactic acid yields and lower levels of undesirable organic acids, such as butyric acid. In contrast, maintaining pH 7 with calcium carbonate created an unsuitable environment for lactic acid bacteria, as their metabolic activity and intracellular pH regulation are disrupted in neutral pH environments, leading to reduced growth and lactic acid production [

19]. Moreover, the inhibitory substances produced by some lactic acid bacteria are less stable and lose their effectiveness at neutral or alkaline pH, further exacerbating the suppression of lactic acid bacteria and allowing other undesirable bacteria to proliferate [

20]. At pH 4.5, the low pH effectively suppressed competing bacteria growth; however, as the buffer was consumed during silage, the pH dropped further. Once the pH fell below a critical threshold, lactic acid bacteria growth was inhibited, leading to lower lactic acid yields than the pH 6 group. Buffering salts in silage effectively enhance lactic acid production while slightly reducing ethanol concentrations. However, buffer selection is critical for silage outcomes. Extremely low pH values suppress lactic acid bacteria growth and reduce yields, whereas neutral pH or calcium carbonate fails to inhibit non-lactic acid bacteria, resulting in the production of other organic acids and reduced silage quality. Optimal buffering conditions, such as pH 6, balance the support for lactic acid bacteria growth with minimized activity of competing microorganisms.

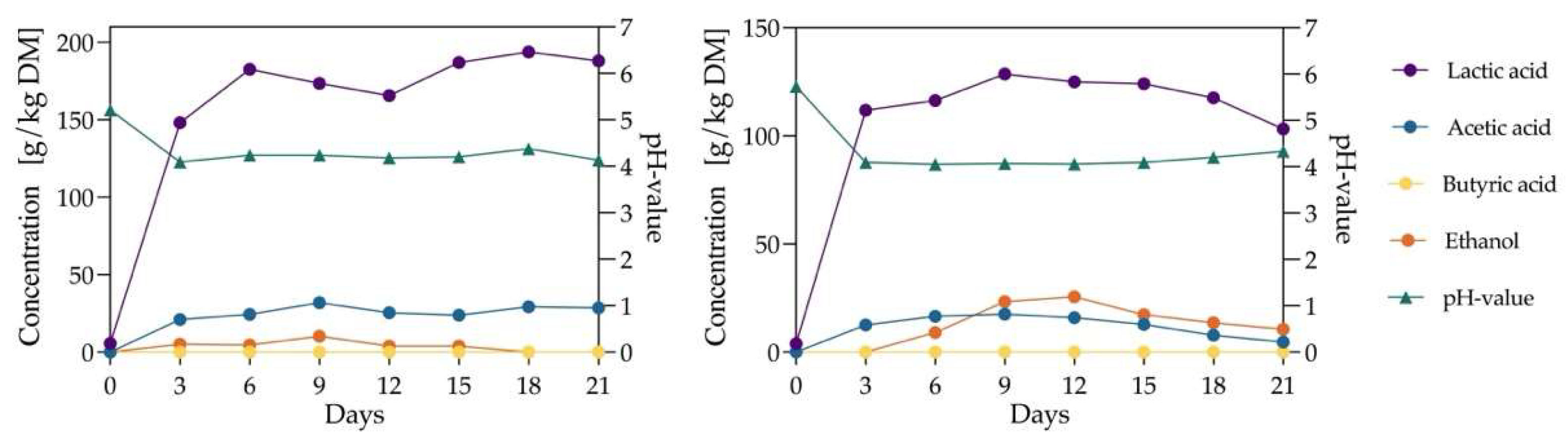

3.3. Silage Dynamics at pH 6 Using Citrate and Phosphate Buffers

This experiment investigated the effects of pH 6 buffer solutions on silage outcomes, using 1 M citrate and phosphate buffers for silage production in 10 L glass bottles, as described in

Section 2.9.2. The silage process lasted 21 days, with samples collected every three days.

The experiment showed (

Figure 4) that silage with citrate or phosphate buffers exhibited a rapid increase in lactic acid concentration within the first three days. In citrate-buffered silage, the lactic acid concentration increased by 143 g/kg DM during this period, 32.4% higher than the 108 g/kg DM observed in phosphate-buffered silage. Additionally, citrate-buffered silage reached its peak lactic acid yield of 193.9 g/kg DM on day 18, while phosphate-buffered silage peaked earlier, on day 9, at 128.5 g/kg DM—a 50.1% lower yield than citrate-buffered silage. This yield was also lower than the 143.9 g/kg DM observed in a previous experiment without buffer solutions. Notably, both groups in this experiment reached their peak lactic acid levels more quickly than vacuum-bag silage. However, the peak lactic acid yield in the citrate-buffered group was lower than that in the earlier experiment using 1 L bottles. This could be attributed to sampling disrupting the anaerobic environment in the bottles, which adversely affected lactic acid bacteria activity. Additionally, the larger 10 L bottles may have been less effective at displacing oxygen during nitrogen purging, and sampling likely removed portions of the silage additive and buffer solution, impacting subsequent samples.

Citrate-buffered silage showed significantly lower ethanol concentrations, peaking at 10.2 g/kg DM on day 9, compared to 25.5 g/kg DM for phosphate-buffered silage on day 12. However, the acetic acid concentration in citrate-buffered silage was relatively higher, reaching 31.9 g/kg DM on day 9, yet lower than the 37.5 g/kg DM in the previous experiment with 1 L bottles. Butyric acid was undetected in either group throughout the 21-day silage period.

The findings suggest that citrate buffers can accelerate lactic acid production during silage. Citrate buffer at pH 6 demonstrated a positive effect on silage quality by enhancing lactic acid production and reducing ethanol concentration. In contrast, phosphate buffer had a significant negative impact on silage outcomes. While it accelerated the time to peak lactic acid concentration, the peak lactic acid yield was significantly lower than in the control group without buffers. Thus, phosphate buffer is unsuitable for silage applications.

3.4. Impact of Lolium perenne Varieties and Harvest Time on Silage Quality

To evaluate the effects of Lolium perenne harvest times on silage outcomes, two varieties, Honroso and Explosion, harvested in 2022 from the Julius Kühn Institute, were selected. Samples from these varieties were subjected to silage under two harvest timings in their main growing period: early cut and late cut, with a 14-day interval between harvests.

Comparison of the experimental results (

Table 3) shows that early-cut samples consistently produced higher lactic acid yields after ensiling. In both Honroso and Explosion, early harvesting resulted in significantly greater lactic acid production, with relative increases of 40.6% and 18%, respectively, compared to the late-cut samples.

Notably, measurements of WSC indicated that earlier harvests, regardless of variety, consistently exhibited higher WSC content. During the early harvest, WSC levels reached 26.4% DM in Explosion and 23.5% DM in Honroso. In contrast, a 14-day harvest delay led to a decline to 23.2% and 21.6% DM, respectively, corresponding to an average reduction of 10.1%. It is noteworthy that Explosion is a tetraploid variety, whereas Honroso is diploid. Previous studies by Gilliland et al. (2002) and Smith et al. (2001) have similarly reported that tetraploid

Lolium perenne varieties generally exhibit higher WSC levels [

21,

22]. Moreover, across both harvest times, the tetraploid variety consistently maintained a 10.0% higher WSC content than the diploid variety, directly contributing to its superior lactic acid yield after ensiling. In the early harvest, the tetraploid variety exhibited a 15.3% higher lactic acid yield than the diploid variety. This gap widened further in the late harvest, reaching 37.3%. The higher WSC content is evidently beneficial for lactic acid production during silage, highlighting the inherent advantage of tetraploid

Lolium perenne varieties in achieving superior fermentation efficiency and silage quality.

These findings confirm that earlier harvesting promotes better fermentation conditions, primarily due to higher WSC availability, while tetraploid varieties outperform diploid ones in terms of fermentation efficiency and silage quality.

3.5. Evaluation of Field Yield and Harvest Timing Effects on Lactic Acid Production in Different Lolium perenne Varieties

In practical agricultural production, evaluating and comparing actual yields are essential for scaling up production and assessing economic feasibility. This chapter an-alyzes the two Lolium perenne varieties examined in previous sections, integrating re-al-field yield data and assessing the impact of harvest timing on final lactic acid pro-duction.

Table 5.

Field yield and lactic acid production in different Lolium perenne varieties under varying harvest timing. Error indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 2).

Table 5.

Field yield and lactic acid production in different Lolium perenne varieties under varying harvest timing. Error indicate standard deviations of the mean (n = 2).

| Sample |

Field Yield |

Lactic acid yield |

| [t DM/ha] |

[g/kg DM] |

[kg/ha] |

| HonrosoE |

3.33 ± 0.2 |

151. 2 |

503 ± 3 |

| HonrosoL |

4.43 ± 0.2 |

107.5 |

476 ± 3 |

| ExplosionE |

4.06 ± 0.5 |

174.4 |

707 ± 8 |

| ExplosionL |

4.85 ± 0.0 |

147.6 |

716 ± 0 |

A comparative analysis of dry matter (DM) yield showed that both varieties benefited from later harvesting, but to different extents. The diploid variety (Honroso) exhibited a DM yield increase of 1.1 t/ha, corresponding to a 33.3% gain compared to the earlier harvest. The tetraploid variety (Explosion) also showed an increase, but by a smaller margin of 0.7 t/ha, equivalent to 17.1%. Despite these improvements, Explosion maintained a higher total DM yield than Honroso, reinforcing the inherent advantage of tetraploid varieties in biomass production.

When examining lactic acid yield per hectare, a more complex trend emerged. In Explosion, lactic acid concentration per kg DM declined by 15.4% after the harvest was postponed. However, due to the increase in total DM yield, total lactic acid yield per hectare rose slightly 9 kg DM/hectare, reflecting a 1.3% improvement. This suggests that Explosion’s higher biomass production compensated for the decline in lactic acid concentration, maintaining a stable overall lactic acid yield per hectare. In contrast, Honroso exhibited a different response to delayed harvesting. Although DM yield increased, lactic acid concentration per kg DM decreased by 28.9%, resulting in a 27 kg/ha reduction in total lactic acid yield per hectare, equivalent to a 5.4% decline. This indicates that, unlike Explosion, the increase in DM yield could not offset the reduction in lactic acid concentration, leading to an overall loss in lactic acid production.

These findings indicate that even when considering actual field yield, tetraploid Lolium perenne varieties maintain a distinct advantage over diploid varieties in terms of total lactic acid production per hectare. Furthermore, the increase in harvested dry matter per hectare due to delayed harvesting plays a crucial role in determining final lactic acid yield. While the increase in field yield among tetraploid varieties resulted in only a marginal improvement in lactic acid production, the yield reduction in diploid varieties was more pronounced. Therefore, in practical agricultural production, optimizing harvest timing should be carefully balanced with overall production planning and cost efficiency to maximize both economic and environmental benefits.

4. Conclusion

This study evaluated the suitability of different Lolium perenne varieties for lactic acid production and silage use, focusing on the effects of harvest timing, water-soluble carbohydrate content, and pH regulation. The results highlighted significant differences between diploid and tetraploid varieties in terms of lactic acid yield and their response to delayed harvesting. Limiting silage duration to 21 days proved to be the optimal condition, as peak lactic acid yields were consistently observed at this stage across all tested varieties. Maintaining a slightly acidic environment with a pH range of 4.5 to 6 was crucial for maximizing lactic acid production while minimizing undesirable by-products such as ethanol and butyric acid. Among the tested buffering strategies, citrate buffering at pH 6 was the most effective, leading to higher lactic acid yields and improved fermentation stability.

Harvest timing had a substantial impact on lactic acid yield per hectare, but the effects varied between the studied varieties. While delaying the harvest increased dry matter (DM) yield in both diploid and tetraploid varieties, its impact on total lactic acid yield per hectare was variety-dependent. Tetraploid varieties like Explosion were able to compensate for the decline in lactic acid concentration per kg DM through increased biomass production, maintaining a stable or slightly improved total lactic acid yield per hectare. In contrast, diploid varieties like Honroso experienced a net reduction in total lactic acid yield per hectare, despite the increase in DM yield, indicating that earlier harvesting is more advantageous for fermentation efficiency in these varieties. This suggests that tetraploid varieties offer greater flexibility in harvest timing, whereas diploid varieties require more precise timing to maximize lactic acid production.

These findings emphasize the importance of variety selection and tailored harvest strategies to balance biomass production and fermentation efficiency, ensuring optimal lactic acid yields without compromising silage quality. From an agronomic perspective, the decision on harvest timing should carefully consider both total biomass accumulation and lactic acid yield per hectare. While delayed harvesting can increase overall DM yield, its impact on fermentation efficiency varies between diploid and tetraploid varieties. Optimizing these factors can contribute to economic and environmental benefits in agricultural production systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.G. and N.T.; methodology, T.G., T.N. and N.T.; validation, T.G., T.N. and N.T.; formal analysis, T.G.; investigation, T.G. and T.N.; data curation, T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, T.G. K.K., and N.T.; writing—review and editing, T.G. K.K., and N.T.; visualization, T.G.; supervision, N.T.; project administration, K.K. and N.T.; funding acquisition, K.K. and N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was financially supported by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture and the Agency for Renewable Resources (BMEL/FNR) through the grant number 220NR026A/B/C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Antar: M.; Lyu, D.; Nazari, M.; Shah, A.; Zhou, X.; Smith, D.L. Biomass for a Sustainable Bioeconomy: An Overview of World Biomass Production and Utilization. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 139, 110691. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.G.; Yadav, G.D.; Patankar, S.C. The Production of Fuels and Chemicals in the New World: Critical Analysis of the Choice between Crude Oil and Biomass Vis-à-Vis Sustainability and the Environment. Clean Techn Environ Policy 2020, 22, 1757–1774. [CrossRef]

-

Advances in Biorefineries: Biomass and Waste Supply Chain Exploitation; Waldron, K.W., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing series in energy; Elsevier/Woodhead Publishing: Amsterdam, 2014; ISBN 978-0-85709-521-3.

- Conaghan, P.; O’Kiely, P.; Howard, H.; O’Mara, F.P.; Halling, M.A. Evaluation of Lolium Perenne L. Cv. AberDart and AberDove for Silage Production. IRISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD RESEARCH 2008, 47.

- Alves De Oliveira, R.; Komesu, A.; Vaz Rossell, C.E.; Maciel Filho, R. Challenges and Opportunities in Lactic Acid Bioprocess Design—From Economic to Production Aspects. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2018, 133, 219–239. [CrossRef]

- López-Gómez, J.P.; Alexandri, M.; Schneider, R.; Venus, J. A Review on the Current Developments in Continuous Lactic Acid Fermentations and Case Studies Utilising Inexpensive Raw Materials. Process Biochemistry 2019, 79, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Varriale, L.; Hengsbach, J.-N.; Guo, T.; Kuka, K.; Tippkötter, N.; Ulber, R. Sustainable Production of Lactic Acid Using a Perennial Ryegrass as Feedstock—A Comparative Study of Fermentation at the Bench- and Reactor-Scale, and Ensiling. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8054. [CrossRef]

- Moorby, J.M.; Evans, R.T.; Scollan, N.D.; MacRae, J.C.; Theodorou, M.K. Increased Concentration of Water-soluble Carbohydrate in Perennial Ryegrass ( Lolium Perenne L.). Evaluation in Dairy Cows in Early Lactation. Grass and Forage Science 2006, 61, 52–59. [CrossRef]

- Przemieniecki, S.W.; Purwin, C.; Mastalerz, J.; Borsuk, M.; Lipiński, K.; Kurowski, T. Biostimulating Effect of l- Tryptophan on the Yield and Chemical and Microbiological Quality of Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne) Herbage and Silage for Ruminant. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 101, 3969–3974. [CrossRef]

- Keating, T.; O’kiely, P. Comparison of Old Permanent Grassland, Lolium Perenne and Lolium Multiflorum Swards Grown for Silage: 4. Effects of Varying Harvesting Date. Irish Journal of Agricultural and Food Research 2000, 39, 55–71.

- Beschreibende Sortenliste Futtergräser Esparsette, Klee, Luzerne 2024.

- Yang, P.-B.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cong, W. Effect of Different Types of Calcium Carbonate on the Lactic Acid Fermentation Performance of Lactobacillus Lactis. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2015, 98, 38–46. [CrossRef]

- AAT Bioquest Inc. Citrate Buffer (pH 3.0 to 6.2) Preparation and Recipe Available online: https://www.aatbio.com/resources/buffer-preparations-and-recipes/citrate-buffer-ph-3-to-6-2 (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Zi, X.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Lv, R.; Zhou, H.; Tang, J. Effects of Citric Acid and Lactobacillus Plantarum on Silage Quality and Bacterial Diversity of King Grass Silage. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 631096. [CrossRef]

- Oude Elferink, S.J.W.H.; Krooneman, J.; Gottschal, J.C.; Spoelstra, S.F.; Faber, F.; Driehuis, F. Anaerobic Conversion of Lactic Acid to Acetic Acid and 1,2-Propanediol by Lactobacillus Buchneri. Appl Environ Microbiol 2001, 67, 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ding, W.; Ke, W.; Li, F.; Zhang, P.; Guo, X. Modulation of Metabolome and Bacterial Community in Whole Crop Corn Silage by Inoculating Homofermentative Lactobacillus Plantarum and Heterofermentative Lactobacillus Buchneri. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3299. [CrossRef]

- Boontawan, P.; Kanchanathawee, S.; Boontawan, A. Extractive Fermentation of L-(+)-Lactic Acid by Pediococcus Pentosaceus Using Electrodeionization (EDI) Technique. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2011, 54, 192–199. [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, S. Anaerobic ?-Lactate Degradation by Lactobacillus Plantarum. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1990, 66, 209–213. [CrossRef]

- Nannen, N.L.; Hutkins, R.W. Intracellular pH Effects in Lactic Acid Bacteria. Journal of Dairy Science 1991, 74, 741–746. [CrossRef]

- Baribo, L.E.; Foster, E.M. Some Characteristics of the Growth Inhibitor Produced by a Lactic Streptococcus. Journal of Dairy Science 1951, 34, 1128–1135. [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, T.J.; Barrett, P.D.; Mann, R.L.; Agnew, R.E.; Fearon, A.M. Canopy Morphology and Nutritional Quality Traits as Potential Grazing Value Indicators for Lolium Perenne Varieties. J. Agric. Sci. 2002, 139, 257–273. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.F.; Simpson, R.J.; Culvenor, R.A.; Humphreys, M.O.; Prud’Homme, M.P.; Oram, R.N. The Effects of Ploidy and a Phenotype Conferring a High Water-Soluble Carbohydrate Concentration on Carbohydrate Accumulation, Nutritive Value and Morphology of Perennial Ryegrass ( Lolium Perenne L.). J. Agric. Sci. 2001, 136, 65–74. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).