Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

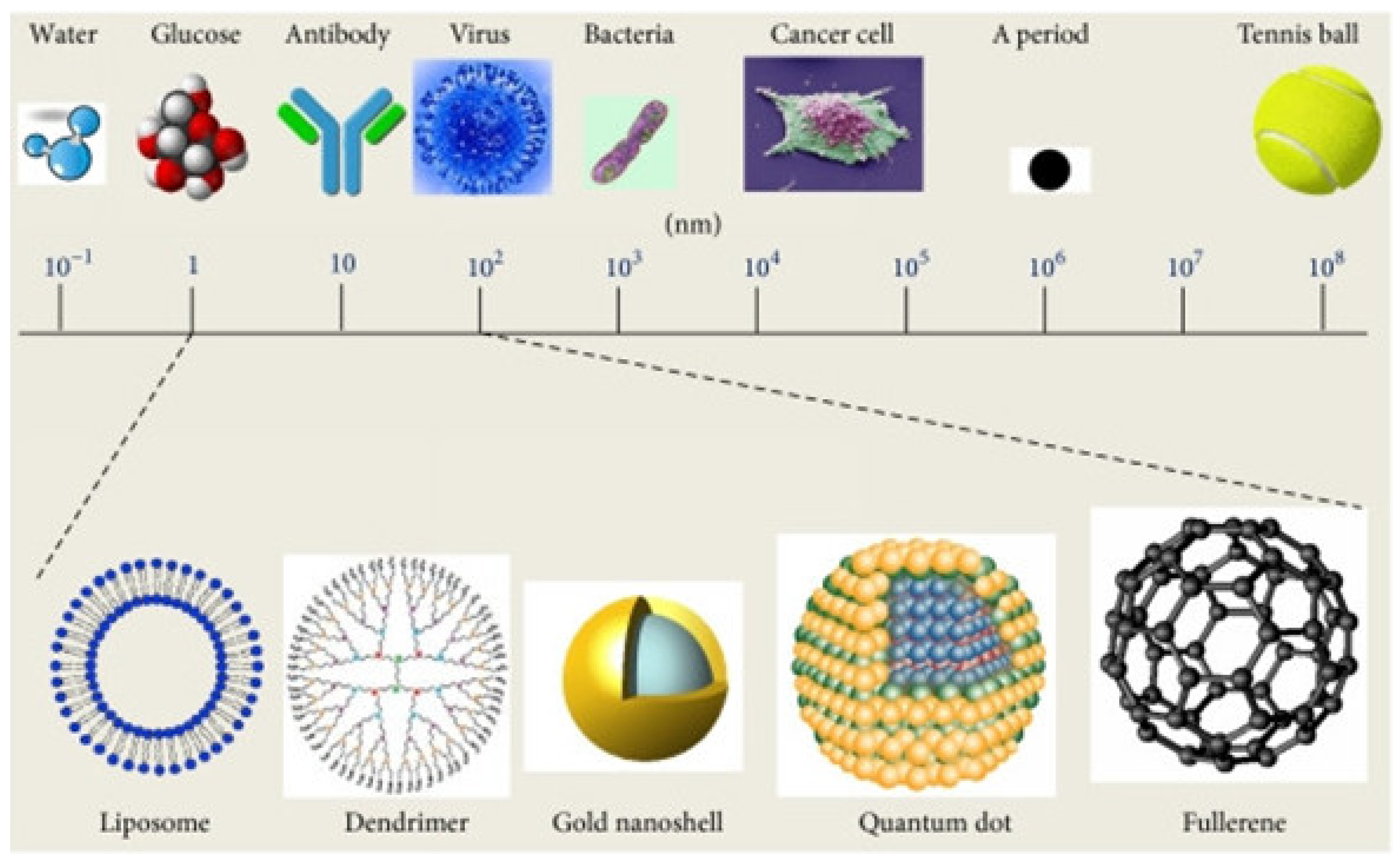

Nanomaterials have revolutionized various biological applications, including cosmeceuticals, enabling the development of smart nanocarriers for enhanced skin delivery. This review focuses on the role of nanotechnologies in skincare and treatments, providing a concise overview of smart nanocarriers, including thermo-, pH-, and multi-stimuli sensitive systems, focusing on their design, fabrication, and applications in cosmeceuticals. These nanocarriers offer controlled release of active ingredients, addressing challenges like poor skin penetration and ingredient instability. This work discusses the unique properties and advantages of various nanocarrier types, highlighting their potential in addressing diverse skin concerns. Furthermore, we address the critical aspect of biocompatibility, examining potential health risks associated with nanomaterials. Finally, this review highlights current challenges, including precise control of drug release, scalability, and the transition from in vitro to in vivo applications. We also discuss future perspectives, such as the integration of digital technologies and artificial intelligence for personalized skincare to further advance in the technology of smart nanocarriers in cosmeceuticals.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Smart Nanomaterials

Thermo-Sensitive Nanocarriers

pH-Sensitive Nanocarriers

Other Stimuli-Sensitive Nanocarriers

Multiple Stimuli-Sensitive Systems

4. Biocompatibility of Nanocarriers

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Conflicts of Interest

References

- V. Gupta et al., “Nanotechnology in Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals-A Review of Latest Advancements,” (in eng), Gels, vol. 8, no. 3, Mar 10 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. A. A. Aziz et al., “Role of Nanotechnology for Design and Development of Cosmeceutical: Application in Makeup and Skin Care,” (in eng), Front Chem, vol. 7, p. 739, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhou et al., “Current Advances of Nanocarrier Technology-Based Active Cosmetic Ingredients for Beauty Applications,” (in eng), Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol, vol. 14, pp. 867-887, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Martel-Estrada, A. Morales-Cardona, C. Vargas-Requena, J. Rubio-Lara, C. Martínez-Pérez, and F. Jimenez-Vega, “Delivery systems in nanocosmeceuticals,” (in English), Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Review vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 901-930, DEC 27 2022 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Golubovic-Liakopoulos, S. R. Simon, and B. Shah, “Nanotechnology use with cosmeceuticals,” (in eng), Semin Cutan Med Surg, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 176-80, Sep 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mohammed et al., “Advances and future perspectives in epithelial drug delivery,” (in English), Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, Review vol. 186, JUL 2022 2022, Art no. ARTN 114293. [CrossRef]

- C. Puglia and D. Santonocito, “Cosmeceuticals: Nanotechnology-Based Strategies for the Delivery of Phytocompounds,” (in English), Current Pharmaceutical Design, Review vol. 25, no. 21, pp. 2314-2322, 2019 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Marianecci et al., “Niosomes from 80s to present: the state of the art,” (in eng), Adv Colloid Interface Sci, vol. 205, pp. 187-206, Mar 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Katz, K. Dewan, and R. Bronaugh, “Nanotechnology in cosmetics,” (in English), Food and Chemical Toxicology, Article vol. 85, pp. 127-137, NOV 2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mihranyan, N. Ferraz, and M. Stromme, “Current status and future prospects of nanotechnology in cosmetics,” (in English), Progress in Materials Science, Review vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 875-910, JUN 2012 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Raszewska-Famielec and J. Flieger, “Nanoparticles for Topical Application in the Treatment of Skin Dysfunctions-An Overview of Dermo-Cosmetic and Dermatological Products,” (in eng), Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 24, Dec 15 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Sethi, R. Rana, S. Sambhakar, and M. Chourasia, “Nanocosmeceuticals: Trends and Recent Advancements in Self Care,” (in English), Aaps Pharmscitech, Review vol. 25, no. 3, FEB 29 2024 2024, Art no. ARTN 51. [CrossRef]

- Pareek et al., “Advancing lipid nanoparticles: A pioneering technology in cosmetic and dermatological treatments,” (in English), Colloid and Interface Science Communications, Article vol. 64, JAN 2025 2025, Art no. ARTN 100814. [CrossRef]

- G. Fytianos, A. Rahdar, and G. Kyzas, “Nanomaterials in Cosmetics: Recent Updates,” (in English), Nanomaterials, Review vol. 10, no. 5, MAY 2020 2020, Art no. ARTN 979. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, R. Bansal, N. Jindal, and A. Jindal, “Nanocarriers and nanoparticles for skin care and dermatological treatments,” (in eng), Indian Dermatol Online J, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 267-72, Oct 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Tenchov, R. Bird, A. E. Curtze, and Q. Zhou, “Lipid Nanoparticles─From Liposomes to mRNA Vaccine Delivery, a Landscape of Research Diversity and Advancement,” ACS Nano, vol. 15, no. 11, pp. 16982-17015, 2021/11/23 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Oliveira, C. Coelho, J. A. Teixeira, P. Ferreira-Santos, and C. M. Botelho, “Nanocarriers as Active Ingredients Enhancers in the Cosmetic Industry-The European and North America Regulation Challenges,” (in eng), Molecules, vol. 27, no. 5, Mar 3 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Antunes, P. Pereira, C. Reis, and P. Rijo, “Nanosystems for Skin Delivery: From Drugs to Cosmetics,” (in eng), Curr Drug Metab, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 412-425, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Khezri, M. Saeedi, and S. Dizaj, “Application of nanoparticles in percutaneous delivery of active ingredients in cosmetic preparations,” (in English), Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, Review vol. 106, pp. 1499-1505, OCT 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Piluk, G. Faccio, S. Letsiou, R. Liang, and M. Freire-Gormaly, “A critical review investigating the use of nanoparticles in cosmetic skin products,” (in English), Environmental Science-Nano, Review vol. 11, no. 9, pp. 3674-3692, SEP 12 2024 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. R. Maghraby, A. H. Ibrahim, R. M. El-Shabasy, and H. M. E.-S. Azzazy, “Overview of Nanocosmetics with Emphasis on those Incorporating Natural Extracts,” ACS Omega, vol. 9, no. 34, pp. 36001-36022, 2024/08/27 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. I. Martin and D. A. Glaser, “Cosmeceuticals: the new medicine of beauty,” (in eng), Mo Med, vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 60-3, Jan-Feb 2011.

- Goyal et al., “Bioactive-Based Cosmeceuticals: An Update on Emerging Trends,” (in eng), Molecules, vol. 27, no. 3, Jan 27 2022. [CrossRef]

- 24 A. Pandey, G. K. Jatana, and S. Sonthalia, “Cosmeceuticals,” in StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC., 2025.

- M. Manela-Azulay and E. Bagatin, “Cosmeceuticals vitamins,” (in eng), Clin Dermatol, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 469-74, Sep-Oct 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. Pandey, D. Bawiskar, and V. Wagh, “Nanocosmetics and Skin Health: A Comprehensive Review of Nanomaterials in Cosmetic Formulations,” (in eng), Cureus, vol. 16, no. 1, p. e52754, Jan 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. P. Vinardell and M. Mitjans, “Nanocarriers for Delivery of Antioxidants on the Skin,” Cosmetics, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 342-354doi: 10.3390/cosmetics2040342.

- L. Van Gheluwe, I. Chourpa, C. Gaigne, and E. Munnier, “Polymer-Based Smart Drug Delivery Systems for Skin Application and Demonstration of Stimuli-Responsiveness,” (in English), Polymers, Review vol. 13, no. 8, APR 2021 2021, Art no. ARTN 1285. [CrossRef]

- D. Liu, F. Yang, F. Xiong, and N. Gu, “The Smart Drug Delivery System and Its Clinical Potential,” (in eng), Theranostics, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 1306-23, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Mura, J. Nicolas, and P. Couvreur, “Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery,” (in English), Nature Materials, Review vol. 12, no. 11, pp. 991-1003, NOV 2013 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Klee, M. Farwick, and P. Lersch, “Triggered release of sensitive active ingredients upon response to the skin’s natural pH,” (in English), Colloids and Surfaces a-Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, Article vol. 338, no. 1-3, pp. 162-166, APR 15 2009 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Nastiti, T. Ponto, Y. Mohammed, M. S. Roberts, and H. A. E. Benson, “Novel Nanocarriers for Targeted Topical Skin Delivery of the Antioxidant Resveratrol,” (in eng), Pharmaceutics, vol. 12, no. 2, Jan 29 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Dubey, A. Dey, G. Singhvi, M. Pandey, V. Singh, and P. Kesharwani, “Emerging trends of nanotechnology in advanced cosmetics,” (in English), Colloids and Surfaces B-Biointerfaces, Article vol. 214, JUN 2022 2022, Art no. ARTN 112440. [CrossRef]

- K. Elkhoury, P. Koçak, A. Kang, E. Arab-Tehrany, J. Ellis Ward, and S. R. Shin, “Engineering Smart Targeting Nanovesicles and Their Combination with Hydrogels for Controlled Drug Delivery,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 12, no. 9. [CrossRef]

- R. Parhi, “Development and optimization of pluronic® F127 and HPMC based thermosensitive gel for the skin delivery of metoprolol succinate,” (in English), Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, Article vol. 36, pp. 23-33, DEC 2016 2016. [CrossRef]

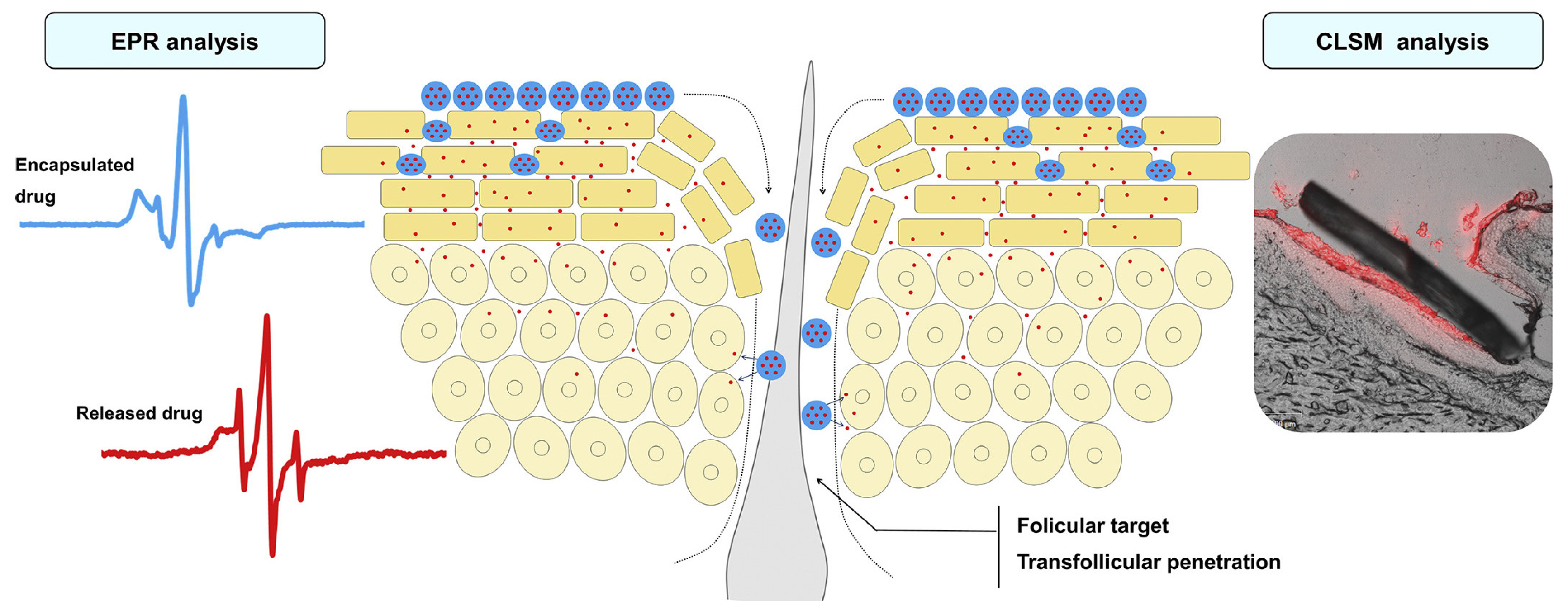

- F. Rancan, M. Giulbudagian, J. Jurisch, U. Blume-Peytavi, M. Calderón, and A. Vogt, “Drug delivery across intact and disrupted skin barrier: Identification of cell populations interacting with penetrated thermoresponsive nanogels,” (in eng), Eur J Pharm Biopharm, vol. 116, pp. 4-11, Jul 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Op ’t Veld et al., “Thermosensitive biomimetic polyisocyanopeptide hydrogels may facilitate wound repair,” (in eng), Biomaterials, vol. 181, pp. 392-401, Oct 2018. [CrossRef]

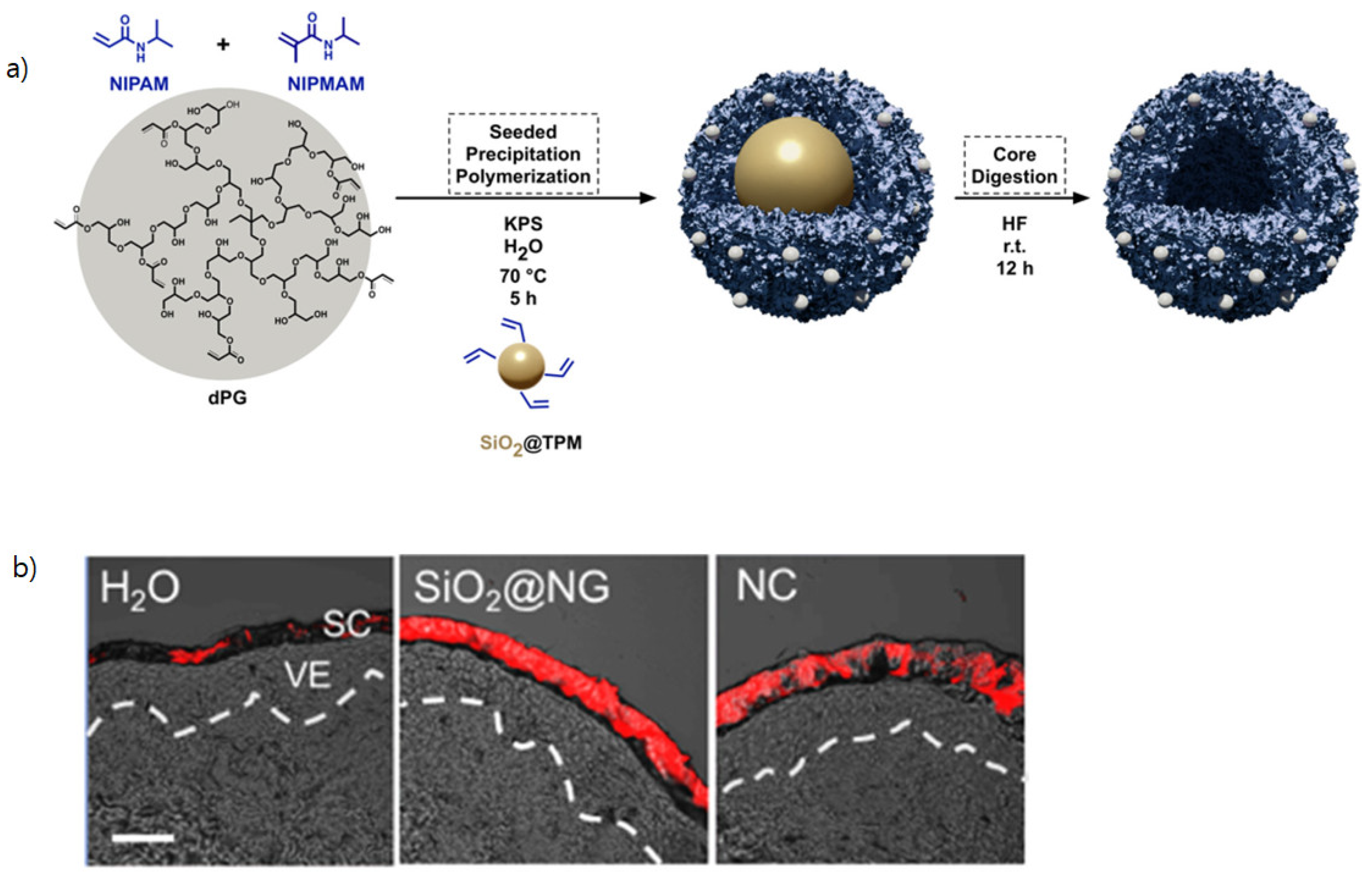

- M. Asadian-Birjand et al., “Engineering thermoresponsive polyether-based nanogels for temperature dependent skin penetration,” (in English), Polymer Chemistry, Article vol. 6, no. 32, pp. 5827-5831, 2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Kang, S. Hong, and J. Kim, “Release property of microgels formed by electrostatic interaction between poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-methacrylic acid) and poly(N-isopropylacrylamide-co-dimethylaminoethylmethacrylate),” (in English), Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Article vol. 125, no. 3, pp. 1993-1999, AUG 5 2012 2012. [CrossRef]

- N. Ferreira, L. Ferreira, V. Cardoso, F. Boni, A. Souza, and M. Gremiao, “Recent advances in smart hydrogels for biomedical applications: From self-assembly to functional approaches,” (in English), European Polymer Journal, Review vol. 99, pp. 117-133, FEB 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Neumann et al., “Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels: The Dynamic Smart Biomaterials of Tomorrow,” (in eng), Macromolecules, vol. 56, no. 21, pp. 8377-8392, Nov 14 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A. Paul, S. Sen, and K. Sen, “Studies on thermoresponsive polymers: Phase behaviour, drug delivery and biomedical applications,” (in English), Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Review vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 99-107, APR 2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Ghosh and G. Chakrabarti, “Applications of Targeted Nano Drugs and Delivery Systems,” in Thermoresponsive Drug Delivery Systems, Characterization and Application, D. D. Ghosh and G. Chakrabarti Eds. Oxford, UK: Elsevier, 2019, pp. 133-155.

- Y. Ding, S. M. Pyo, and R. H. Müller, “smartLipids(®) as third solid lipid nanoparticle generation - stabilization of retinol for dermal application,” (in eng), Pharmazie, vol. 72, no. 12, pp. 728-735, Dec 1 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Schäfer-Korting, W. Mehnert, and H. C. Korting, “Lipid nanoparticles for improved topical application of drugs for skin diseases,” (in eng), Adv Drug Deliv Rev, vol. 59, no. 6, pp. 427-43, Jul 10 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Kang et al., “Preparation and evaluation of tacrolimus-loaded thermosensitive solid lipid nanoparticles for improved dermal distribution,” (in English), International Journal of Nanomedicine, Article vol. 14, pp. 5381-5396, 2019 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Gerecke et al., “Biocompatibility and characterization of polyglycerol-based thermoresponsive nanogels designed as novel drug-delivery systems and their intracellular localization in keratinocytes,” (in English), Nanotoxicology, Article vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 267-277, MAR 2017 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Jadhav, D. Scalarone, V. Brunella, E. Ugazio, S. Sapino, and G. Berlier, “Thermoresponsive copolymer-grafted SBA-15 porous silica particles for temperature-triggered topical delivery systems,” (in English), Express Polymer Letters, Article vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 96-105, FEB 2017 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Witting et al., “Thermosensitive dendritic polyglycerol-based nanogels for cutaneous delivery of biomacromolecules,” (in English), Nanomedicine-Nanotechnology Biology and Medicine, Article vol. 11, no. 5, pp. 1179-1187, JUL 2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. Osorio-Blanco et al., “Polyglycerol-Based Thermoresponsive Nanocapsules Induce Skin Hydration and Serve as a Skin Penetration Enhancer,” (in English), Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces, Article vol. 12, no. 27, pp. 30136-30144, JUL 8 2020 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Ugazio et al., “Thermoresponsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a carrier for skin delivery of quercetin,” (in English), International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Article vol. 511, no. 1, pp. 446-454, SEP 10 2016 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Pelegrino, D. de Araújo, and A. Seabra, “S-nitrosoglutathione-containing chitosan nanoparticles dispersed in Pluronic F-127 hydrogel: Potential uses in topical applications,” (in English), Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, Article vol. 43, pp. 211-220, FEB 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zavgorodnya, C. Carmona-Moran, V. Kozlovskaya, F. Liu, T. Wick, and E. Kharlampieva, “Temperature-responsive nanogel multilayers of poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) for topical drug delivery,” (in English), Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, Article vol. 506, pp. 589-602, NOV 15 2017 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Chen, H. Zhang, S. Cheng, G. Zhai, and C. Shen, “Development of curcumin loaded nanostructured lipid carrier based thermosensitive <i>in situ</i> gel for dermal delivery,” (in English), Colloids and Surfaces a-Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, Article vol. 506, pp. 356-362, OCT 5 2016 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Lambers, S. Piessens, A. Bloem, H. Pronk, and P. Finkel, “Natural skin surface pH is on average below 5, which is beneficial for its resident flora,” (in eng), Int J Cosmet Sci, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 359-70, Oct 2006. [CrossRef]

- E. Jones, C. Cochrane, and S. Percival, “The Effect of pH on the Extracellular Matrix and Biofilms,” (in English), Advances in Wound Care, Review vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 431-439, JUL 2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Eberlein-König et al., “Skin surface pH, stratum corneum hydration, trans-epidermal water loss and skin roughness related to atopic eczema and skin dryness in a population of primary school children,” (in eng), Acta Derm Venereol, vol. 80, no. 3, pp. 188-91, May 2000. [CrossRef]

- N. Schürer, “pH and Acne,” (in eng), Curr Probl Dermatol, vol. 54, pp. 115-122, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Karimi et al., “pH-Sensitive stimulus-responsive nanocarriers for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents,” (in English), Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology, Review vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 696-716, SEP-OCT 2016 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Abri Aghdam et al., “Recent advances on thermosensitive and pH-sensitive liposomes employed in controlled release,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 315, pp. 1-22, 2019/12/10/ 2019. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D. Mishra, T. Das, and T. Maiti, “Wound pH-Responsive Sustained Release of Therapeutics from a Poly(NIPAAm-co-AAc) Hydrogel,” (in English), Journal of Biomaterials Science-Polymer Edition, Article vol. 23, no. 1-4, pp. 111-132, 2012 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Jeong, S. Nam, J. Song, and S. Park, “Synthesis and physicochemical properties of pH-sensitive hydrogel based on carboxymethyl chitosan/2-hydroxyethyl acrylate for transdermal delivery of nobiletin,” (in English), Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, Article vol. 51, pp. 194-203, JUN 2019 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Soriano-Ruiz et al., “Design and evaluation of a multifunctional thermosensitive poloxamer-chitosan-hyaluronic acid gel for the treatment of skin burns,” (in eng), Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 142, pp. 412-422, Jan 1 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Alexis, E. Pridgen, L. Molnar, and O. Farokhzad, “Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles,” (in English), Molecular Pharmaceutics, Article|Proceedings Paper vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 505-515, JUL-AUG 2008 2008. [CrossRef]

- W. Gao et al., “Hydrogel containing nanoparticle-stabilized liposomes for topical antimicrobial delivery,” (in eng), ACS Nano, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 2900-7, Mar 25 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Yoshida, T. C. Lai, G. S. Kwon, and K. Sako, “pH- and ion-sensitive polymers for drug delivery,” (in eng), Expert Opin Drug Deliv, vol. 10, no. 11, pp. 1497-513, Nov 2013. [CrossRef]

- P. Dong et al., “pH-sensitive Eudragit® L 100 nanoparticles promote cutaneous penetration and drug release on the skin,” (in English), Journal of Controlled Release, Article vol. 295, pp. 214-222, FEB 2019 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rizi, R. Green, M. Donaldson, and A. Williams, “Using pH Abnormalities in Diseased Skin to Trigger and Target Topical Therapy,” (in English), Pharmaceutical Research, Article vol. 28, no. 10, pp. 2589-2598, OCT 2011 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. Shields et al., “Encapsulation and controlled release of retinol from silicone particles for topical delivery,” (in English), Journal of Controlled Release, Article vol. 278, pp. 37-48, MAY 28 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

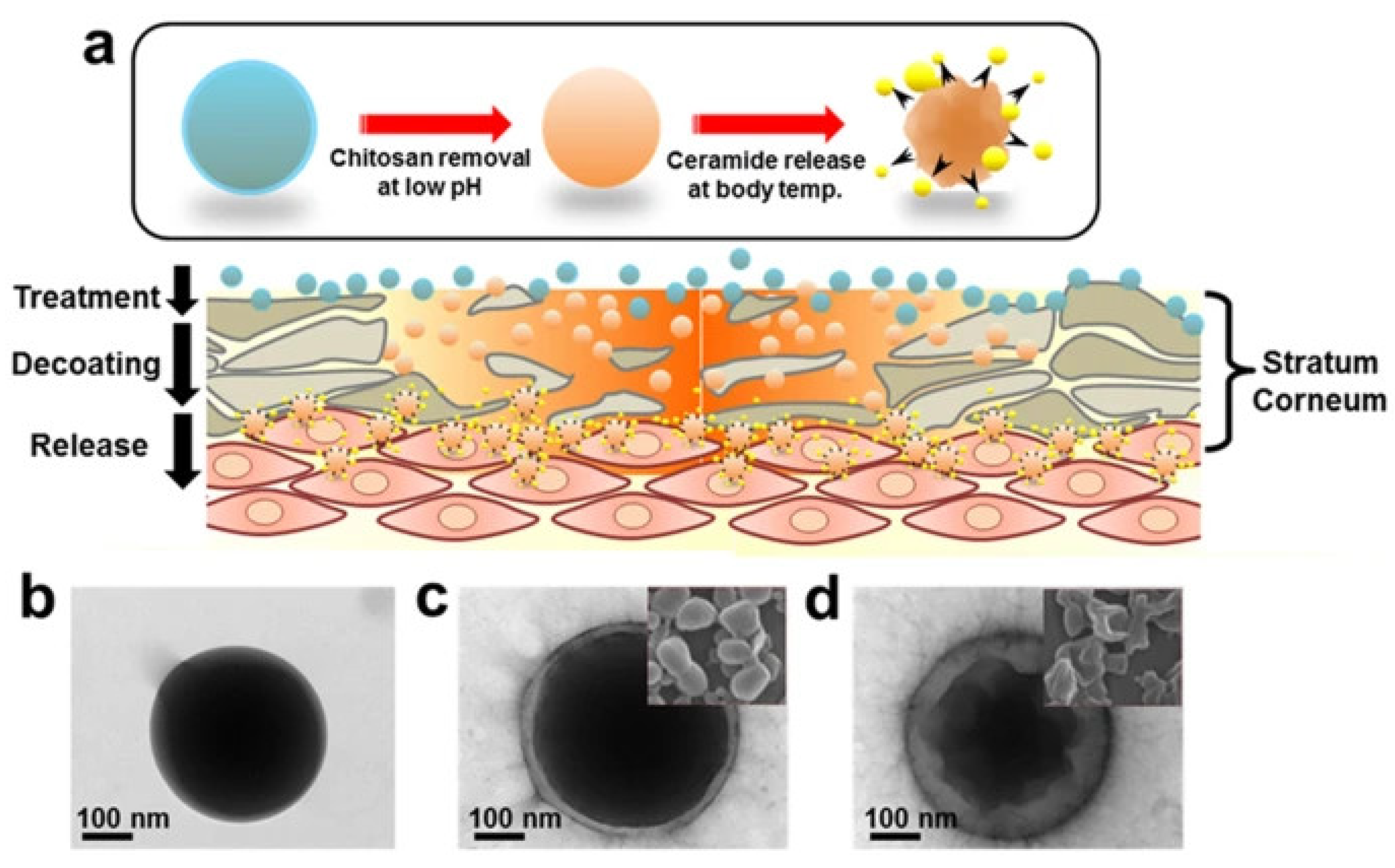

- S. Jung et al., “Thermodynamic Insights and Conceptual Design of Skin-Sensitive Chitosan Coated Ceramide/PLGA Nanodrug for Regeneration of Stratum Corneum on Atopic Dermatitis,” (in English), Scientific Reports, Article vol. 5, DEC 15 2015 2015, Art no. ARTN 18089. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kang et al., “Nanocarrier-Based Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems for Dermatological Therapy,” (in English), Pharmaceutics, Review vol. 16, no. 11, NOV 2024 2024, Art no. ARTN 1384. [CrossRef]

- Van Gheluwe, E. Buchy, I. Chourpa, and E. Munnier, “Three-Step Synthesis of a Redox-Responsive Blend of PEG-block-PLA and PLA and Application to the Nanoencapsulation of Retinol,” (in eng), Polymers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 10, Oct 14 2020. [CrossRef]

- U. Ahmad, Z. Ahmad, A. A. Khan, J. Akhtar, S. P. Singh, and F. J. Ahmad, “Strategies in Development and Delivery of Nanotechnology Based Cosmetic Products,” (in eng), Drug Res (Stuttg), vol. 68, no. 10, pp. 545-552, Oct 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Kim, P. W. Lee, and J. K. Pokorski, “Biologically Triggered Delivery of EGF from Polymer Fiber Patches,” (in eng), ACS Macro Lett, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 593-597, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Im, B. Bai, and Y. S. Lee, “The effect of carbon nanotubes on drug delivery in an electro-sensitive transdermal drug delivery system,” (in eng), Biomaterials, vol. 31, no. 6, pp. 1414-9, Feb 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. Kim, S. L. Lee, and S. N. Park, “Properties and in vitro drug release of pH- and temperature-sensitive double cross-linked interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels based on hyaluronic acid/poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) for transdermal delivery of luteolin,” (in eng), Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 118, no. Pt A, pp. 731-740, Oct 15 2018. [CrossRef]

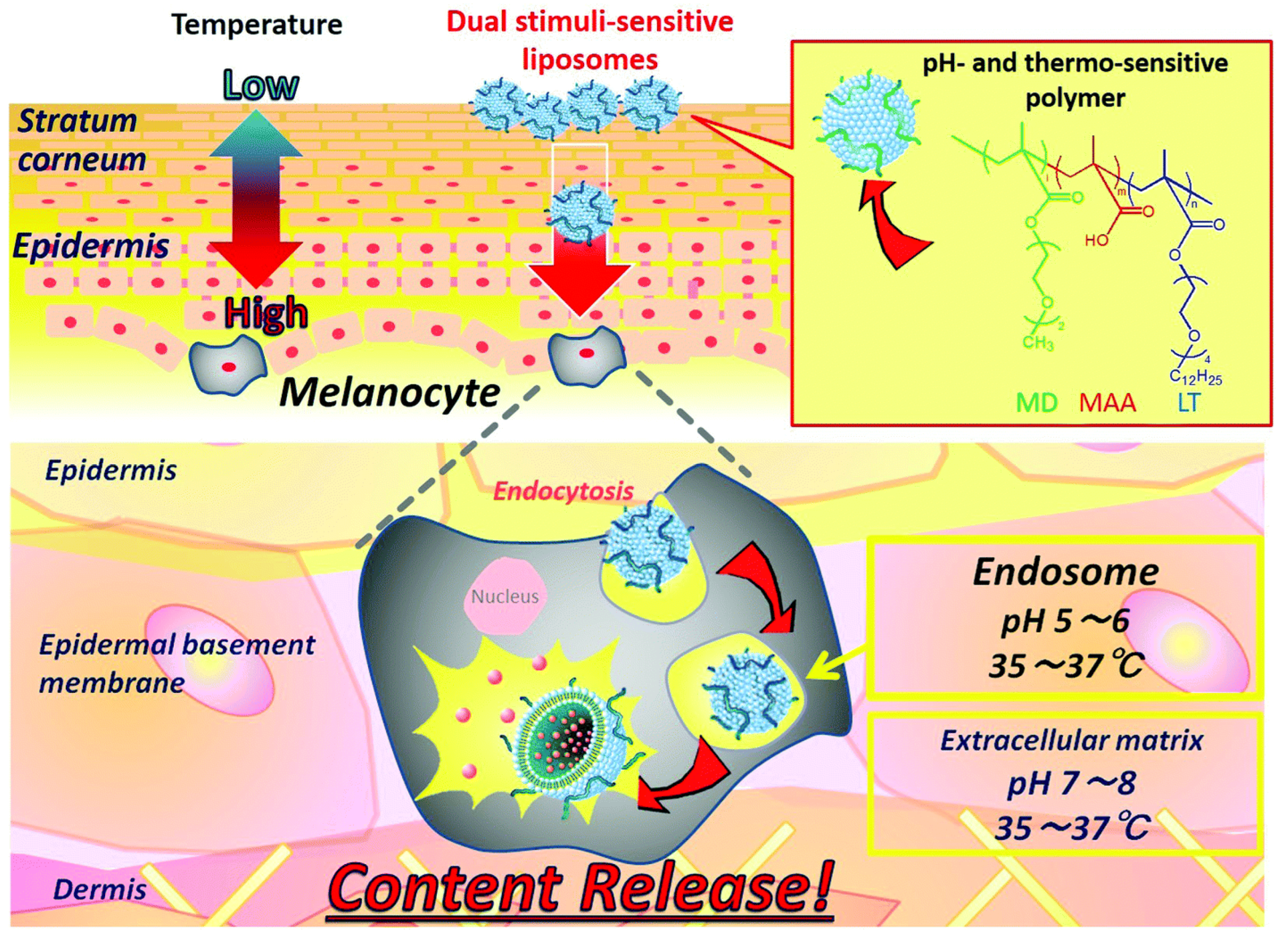

- Yamazaki et al., “Dual-stimuli responsive liposomes using pH- and temperature-sensitive polymers for controlled transdermal delivery,” (in English), Polymer Chemistry, Article vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 1507-1518, MAR 7 2017 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Lee, and S. Park, “Properties and <i>in vitro</i> drug release of pH- and temperature-sensitive double cross-linked interpenetrating polymer network hydrogels based on hyaluronic acid/poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) for transdermal delivery of luteolin,” (in English), International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, Article vol. 118, pp. 731-740, OCT 15 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Lopez, J. Hadgraft, and M. Snowden, “The use of colloidal microgels as a (trans)dermal drug delivery system,” (in English), International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Article vol. 292, no. 1-2, pp. 137-147, MAR 23 2005 2005. [CrossRef]

- Abu Samah and C. Heard, “Enhanced <i>in vitro</i> transdermal delivery of caffeine using a temperature- and pH-sensitive nanogel, poly(NIPAM-<i>co</i>-AAc),” (in English), International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Article vol. 453, no. 2, pp. 630-640, SEP 10 2013 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Mavuso et al., “<i>In Vitro</i>, <i>Ex Vivo</i>, and <i>In Vivo</i> Evaluation of a Dual pH/Redox Responsive Nanoliposomal Sludge for Transdermal Drug Delivery,” (in English), Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Article vol. 107, no. 4, pp. 1028-1036, APR 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, C. Rimicci, S. Garelli, E. Ugazio, and L. Battaglia, “Nanosystems in Cosmetic Products: A Brief Overview of Functional, Market, Regulatory and Safety Concerns,” (in English), Pharmaceutics, Review vol. 13, no. 9, SEP 2021 2021, Art no. ARTN 1408. [CrossRef]

- Hubbs et al., “Nanotoxicology-A Pathologist’s Perspective,” (in English), Toxicologic Pathology, Review vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 301-324, FEB 2011 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Mogharabi, M. Abdollahi, and M. Faramarzi, “Toxicity of nanomaterials; an undermined issue,” (in English), Daru-Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Editorial Material vol. 22, AUG 15 2014 2014, Art no. ARTN 59. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Schneider and H. W. Lim, “A review of inorganic UV filters zinc oxide and titanium dioxide,” (in eng), Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 442-446, Nov 2019. [CrossRef]

- Melo, M. Amadeu, M. Lancellotti, L. de Hollanda, and D. Machado, “THE ROLE OF NANOMATERIALS IN COSMETICS: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL LEGISLATIVE ASPECTS,” (in English), Quimica Nova, Article vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 599-603, MAY 2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Ajazzuddin, G. Jeswani, and A. Kumar Jha, “Nanocosmetics: Past, Present and Future Trends,” Recent Patents on Nanomedicine, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 3-11, // 2015.

- Guidance, “Guidance for Industry Considering Whether an FDA-Regulated Product Involves the Application of Nanotechnology,” (in English), Biotechnology Law Report, Article vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 613-616, SEP 2011 2011. [CrossRef]

- Buzea, Pacheco, II, and K. Robbie, “Nanomaterials and nanoparticles: sources and toxicity,” (in eng), Biointerphases, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. Mr17-71, Dec 2007. [CrossRef]

- Joudeh and D. Linke, “Nanoparticle classification, physicochemical properties, characterization, and applications: a comprehensive review for biologists,” Journal of Nanobiotechnology, vol. 20, no. 1, p. 262, 2022/06/07 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Gebel et al., “Manufactured nanomaterials: categorization and approaches to hazard assessment,” (in English), Archives of Toxicology, Review vol. 88, no. 12, pp. 2191-2211, DEC 2014 2014. [CrossRef]

- W. W. Chan et al., “Grand Plans for Nano,” (in eng), ACS Nano, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 11503-5, Dec 22 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Shokri, “Nanocosmetics: benefits and risks,” (in English), Bioimpacts, Editorial Material vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 207-208, 2017 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Schneider, F. Stracke, S. Hansen, and U. F. Schaefer, “Nanoparticles and their interactions with the dermal barrier,” (in eng), Dermatoendocrinol, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 197-206, Jul 2009. [CrossRef]

- M. Wang, X. Lai, L. Shao, and L. Li, “Evaluation of immunoresponses and cytotoxicity from skin exposure to metallic nanoparticles,” (in eng), Int J Nanomedicine, vol. 13, pp. 4445-4459, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Groso, A. Petri-Fink, A. Magrez, M. Riediker, and T. Meyer, “Management of nanomaterials safety in research environment,” (in English), Particle and Fibre Toxicology, Review vol. 7, DEC 10 2010 2010, Art no. ARTN 40. [CrossRef]

- Drasler, P. Sayre, K. Steinhäuser, A. Petri-Fink, and B. Rothen-Rutishauser, “In vitro approaches to assess the hazard of nanomaterials (vol 8, pg 99, 2017),” (in English), Nanoimpact, Correction vol. 9, pp. 51-51, JAN 2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. H. Lee and Y. Yeo, “Controlled drug release from pharmaceutical nanocarriers,” Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 125, pp. 75-84, 2015/03/24/ 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Adepu and S. Ramakrishna, “Controlled Drug Delivery Systems: Current Status and Future Directions,” (in eng), Molecules, vol. 26, no. 19, Sep 29 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Gupta, U. Agrawal, and S. P. Vyas, “Nanocarrier-based topical drug delivery for the treatment of skin diseases,” (in eng), Expert Opin Drug Deliv, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 783-804, Jul 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Phan and A. J. Haes, “What Does Nanoparticle Stability Mean?,” The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, vol. 123, no. 27, pp. 16495-16507, 2019/07/11 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Akombaetwa, A. B. Ilangala, L. Thom, P. B. Memvanga, B. A. Witika, and A. B. Buya, “Current Advances in Lipid Nanosystems Intended for Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery Applications,” (in eng), Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 2, Feb 15 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. John, J. Monpara, S. Swaminathan, and R. Kalhapure, “Chemistry and Art of Developing Lipid Nanoparticles for Biologics Delivery: Focus on Development and Scale-Up,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 16, no. 1. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee and K. H. Kwon, “Future value and direction of cosmetics in the era of metaverse,” Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, vol. 21, no. 10, pp. 4176-4183, 2022/10/01 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Tarar, U. Mohammad, and K. S. S, “Wearable Skin Sensors and Their Challenges: A Review of Transdermal, Optical, and Mechanical Sensors,” (in eng), Biosensors (Basel), vol. 10, no. 6, May 28 2020. [CrossRef]

- Elder, M. Cappelli, C. Ring, and N. Saedi, “Artificial intelligence in cosmetic dermatology: An update on current trends,” (in English), Clinics in Dermatology, Article vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 216-220, MAY-JUN 2024 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kania, K. Montecinos, and D. Goldberg, “Artificial intelligence in cosmetic dermatology,” (in English), Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, Article vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 3305-3311, OCT 2024 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vatiwutipong, S. Vachmanus, T. Noraset, and S. Tuarob, “Artificial Intelligence in Cosmetic Dermatology: A Systematic Literature Review,” (in English), Ieee Access, Review vol. 11, pp. 71407-71425, 2023 2023. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).