Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a spectrum of conditions, including Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), and IBD-unclassified (IBD-U), which can be characterised by chronic immune activation and inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract [

1]. Environmental and genetic factors, including the microbiome, are involved in the aetiology of IBD, which is known to be multifactorial. Laboratory abnormalities indicative of a chronic inflammatory state, such as anaemia, hypoalbuminemia, and elevated inflammatory markers, are observed in children with IBD. The diagnosis of IBD is established by a combination of clinical, laboratory, imaging, and endoscopic parameters, including histopathology [

2].

The goal of the treatment of paediatric IBD is to induce and maintain clinical remission, achieve normal growth, provide the best quality of life, promote psychological health, and minimise toxicity as much as possible. Despite treatment, disease activation is frequently observed in children with IBD. Stratifying disease progression and the effects of therapeutic interventions are followed by the use of clinical scoring tools such as the Paediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) and the Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) [

3]. The most common way to assess disease activation and mucosal healing is repeated endoscopy with biopsy. However, this technique is invasive, time-consuming, and has an uncomfortable preparatory regimen. Therefore, a non-invasive marker is necessary—one that is accurate, reproducible, standardised, easy to interpret by clinicians, and has a high diagnostic sensitivity and specificity to correlate with disease activation and mucosal healing. The most widely studied inflammatory markers in IBD are C-reactive protein (CRP) and faecal calprotectin (FC). Although a correlation between endoscopic activity and CRP has been reported, the data are still insufficient for its wide use in IBD. Fecal calprotectin is very sensitive, but it is not a specific marker for the detection of inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract [

1,

4]. Moreover, the concentrations of FC in stool samples may differ depending on when they are collected [

5]. In addition, it may not be easy to obtain stool samples from children at any time.

Leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein (LRG) is a 50 kDa glycoprotein that contains repetitive sequences with a leucine-rich motif. It was first purified from human serum, and was recently been developed as a new serum biomarker [

6]. Leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein is an acute-phase protein produced by neutrophils, macrophages, hepatocytes, and intestinal epithelial cells. Unlike CRP, which is induced by interleukin (IL)-6, the expression of LRG is additionally induced by other cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-

, IL-1b, and IL-22 [

7]. Leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein has been linked to various inflammatory states, such as asthma, infections, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune diseases [

7]. It has been demonstrated that serum LRG (s-LRG) is a useful biomarker for predicting mucosal inflammation in CD and UC in adult patients with IBD [

8]. In addition, it has been shown that urinary LRG (u-LRG) is a potential non-invasive biomarker for the diagnosis of acute paediatric appendicitis [

9]. There are very few studies of s-LRG in children with IBD for disease activation. This study aimed to determine s-LRG and u-LRG expression levels in children with IBD and evaluate their correlation with clinical disease activity, other inflammatory markers, laboratory results, and endoscopic activity scoring. Moreover, this is the first study to evaluate the usefulness of u-LRG as an IBD biomarker.

Methods

Patients: This prospective observational study was conducted from January to July 2023 in a tertiary centre and children with IBD who were included in the study. The diagnosis of CD or UC was proven clinically, endoscopically, and histologically. The patients were divided into two groups: those with active IBD and those in remission. Active IBD was defined on the basis of on clinical activity scoring, laboratory results, and endoscopic evaluation. The clinical characteristics of the patients, including age, sex, anthropometric measurements, disease duration, and location, were also recorded. The findings were compared between the groups with active IBD and those with remission. Patients with other diseases that could affect the levels of s-LRG, CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and laboratory results, including extraintestinal complications, other autoimmune diseases, heart failure, infectious disease, and malignancy, were excluded.

Clinical activity: The PCDAI was used to assess clinical disease activity in CD patients. Clinical symptoms were scored via the PUCAI in UC patients [

3]. Clinical activation was defined as a PCDAI and PUCAI greater than 10 in CD patients and UC patients, respectively [

10,

11].

Laboratory Results: Blood and urine samples were collected at the same time as those used for clinical scoring and endoscopic activity evaluations. Hemoglobin levels, platelet (PLT) counts, albumin, CRP, ESR, and LRG levels were analysed in the blood sample. In addition, the LRG levels were measured in the urine samples.

Measurement of serum and urinary LRG levels: Venous blood samples and urine samples were collected after 8–12 hours of fasting. After centrifugation, these samples were portioned and stored at -20 ◦C until the analysis day. A commercial sandwich the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Elabscience Biotechnology Inc., Texas, USA) was used to assess the LRG levels. The studies were performed according to the instructions in the kit package inserts. Spectrophotometric measurements were performed at a wavelength 450 nm via a Rayto (Microplate reader, RT-2100C, China) model ELISA reader. The LRG concentrations of the samples were determined from the standard curve drawn via diluted standard absorbances. The results were expressed as µg/mL.

Endoscopic activity: Endoscopic disease activity was analysed in 78.5% of patients with with active IBD who underwent a total colonoscopy. Colonoscopy could not be performed on other patients because they were unsuitable for anaesthesia or because the family refused. Disease activation was defined by clinical scoring and laboratory results in these patients. For CD patients, the endoscopic assessment was scored according to the simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD; 12). The Mayo endoscopic score (MES) was used in patients with UC [

12]. Scoring was independently performed by two endoscopists who were blinded to the results of the serum and urine marker analyses and reviewed if the scores were different.

Statistical analysis: The power analysis was performed with the G*power program, and the minimum sample size to be included was determined to be 40 in each group in the study. Categorical variables (sex, type of IBD, medications) were assessed via the χ2 test and were expressed as numbers and percentages. Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed to evaluate the normality of the continuous variables. Nonparametric continuous variables (median [minimum-maximum] age; z-score of weight, height, and BMI; duration of disease; PUCAI; PCDAI; hemoglobin; s-LRG; u-LRG; PLT count; albumin; CRP; and ESR) were analysed with the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test. The correlations between laboratory parameters and disease clinical and endoscopic activity scores were analysed via Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. The relationships between disease clinical and endoscopic activity and laboratory parameters were analysed via logistic regression. The data were analysed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) computer software (version 21.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc v12.5 software. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 84 patients, 42 (50%) patients with active IBD and 42 (50%) patients in remission, were included in this study. The characteristics, clinical data, and endoscopic activity scores of the patients are shown in

Table 1.

The inflammatory indicators in laboratory parameters that PLT count, CRP, and ESR were significantly higher in patients with active IBD than in patients with disease remission (p = 0.000, p = 0.046, and p = 0.001, respectively). Albumin and Hb levels were compared between the two groups, and they were found to be lower in patients with active IBD (p = 0.041 and p = 0.009, respectively). Serum LRG concentrations were elevated in the active IBD patients compared with those in IBD patients in remission (p = 0.020). However, there were no difference in the u-LRG levels between the two groups (p = 0.407;

Table 2).

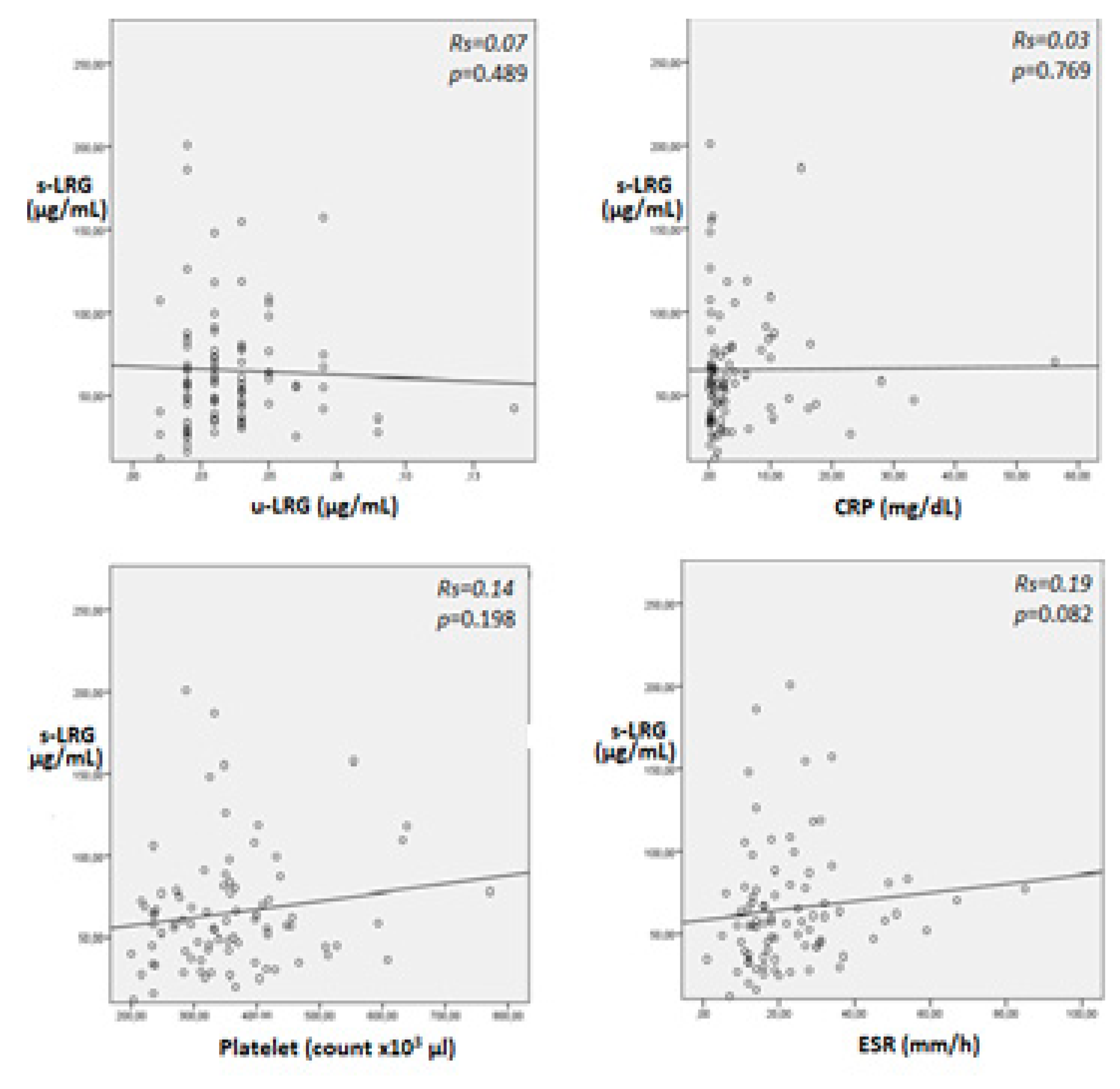

In patients with IBD, positive correlation were observed between s-LRG, the PLT, CRP, and the ESR, but these correlations were not statistically significant (

Figure 1). Thus, s-LRG was significantly negatively correlated with both albumin and Hb (p = 0.002, Rs = -0.26 and p = 0.014, Rs = -0.32, respectively). Urinary LRG was not correlated with s-LRG in any of the IBD patients included or in patients with active IBD (p = 0.489 and p = 0.329, respectively). Although the u-LRG level was not correlated with the PLT, CRP level, ESR, or albumin level, a significant negative correlation was observed between the u-LRG level and the Hb level (p = 0.046).

In patients with UC, according to the PUCAI, 50% (n = 31) achieved with clinic remission, 27.4% (n = 17) had mild clinical activation, 17.7% (n = 11) had moderate clinical activation, and 4.8% (n = 3) had severe clinical activation. According to the PCDAI in CD patients, 13 (59.1%) patients achieved with clinical remission, 3 (13.6%) patients with mild clinical activation, 4 (18.2%) patients with moderate clinical activation, and 2 (9.1%) patients with severe clinical activation. The serum LRG was positively correlated with PUCAI and PCDAI, but it was not statistically significant (p = 0.055, Rs = 0.24 and p = 0.132, Rs = 0.33, respectively). Similarly, the MES and SES-CD were positively but not significantly correlated with s-LRG in patients with active IBD (p = 0.165, Rs = 0.28, and p = 0.779, Rs = 0.11, respectively).

The cutoff value for s- LRG (77.03

μg/mL) had a sensitivity and specificity of 40.4% (95% CI 25.6–56.7%) and 88.1% (95% CI 74.3–96.0%), respectively (

Table 3).

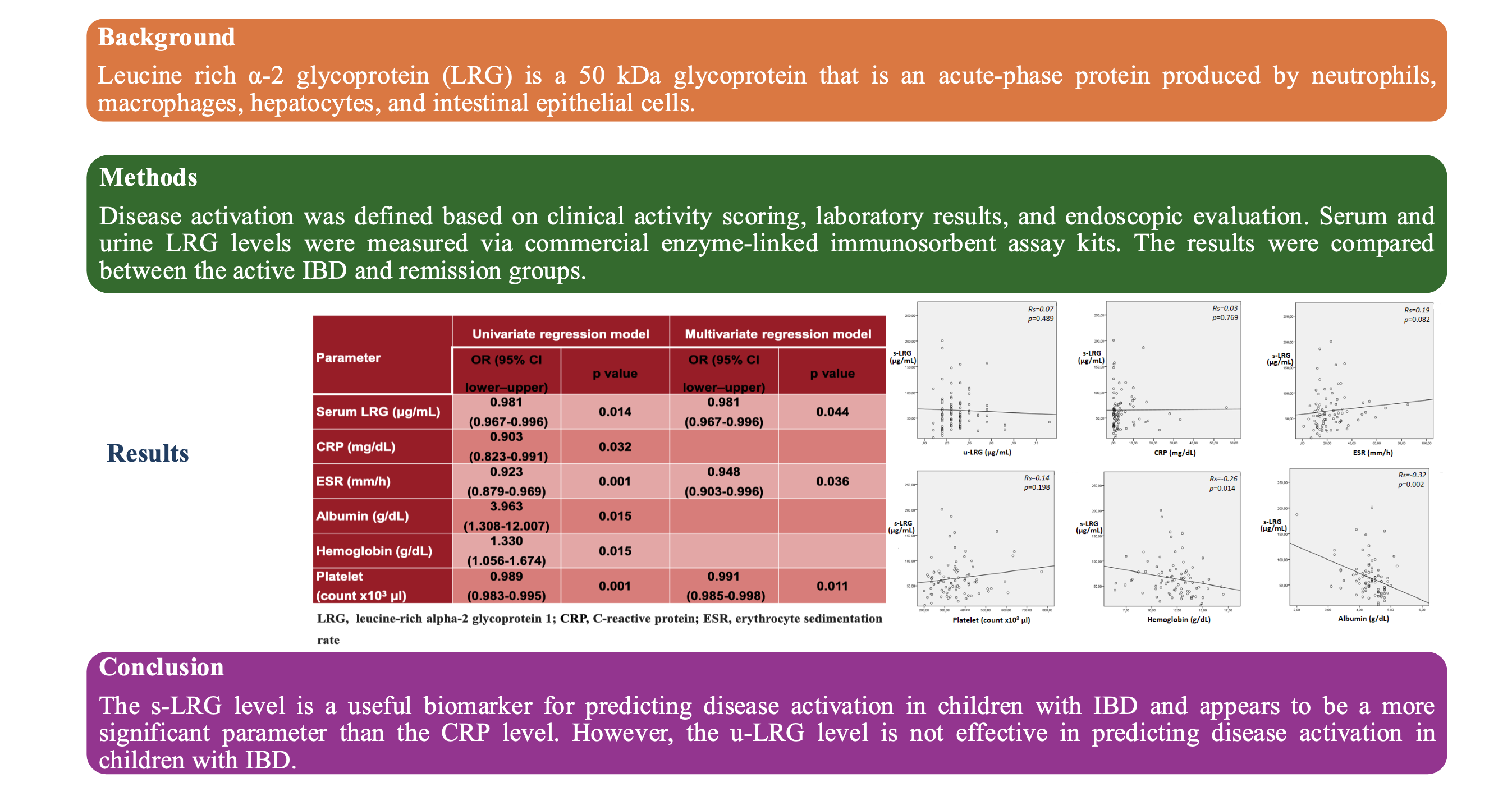

Logistic regression analysis was used in patients with IBD to assess the relationship sbetween laboratory parameters and disease activity. Disease activity was positively associated with s-LRG, ESR, CRP, and the PLT, whereas it was negatively associated with albumin and Hb (

Table 4). It was found that s-LRG was a more significant parameter than CRP in predicting disease activation (p = 0.014 and p = 0.032, respectively). In addition, the PLT count was found to be the most significant parameter for predicting disease activation (p = 0.011).

Discussion

This prospective study demonstrated that s-LRG levels were significantly elevated in active IBD patients compared with patients in remission. Additionally, s-LRG levels were correlated with inflammatory indicators and clinical and endoscopic disease activity scores. However, the study revealed that u-LRG levels were not significantly different in patients with active IBD and were not correlated with s-LRG.

A study of adults revealed that s-LRG may be a biomarker reflecting IBD activity [

12]. Shinzaki et al. demonstrated that s-LRG levels significantly increased and were correlated with clinical and endoscopic activities in UC patients [

13]. Additionally, a recent study evaluating the effectiveness of s-LRG in demonstrating remission in children with IBD revealed that s-LRG levels were lower in patients who were in remission [

14]. Similar to these studies, the present study showed that s-LRG levels were higher in patients with active IBD than in those in remission. In addition, this study showed that s-LRG has good specificity but low sensitivity for disease activation in IBD patients. Yoshimura et al. reported that s-LRG had a sensitivity of 55.6% and a specificity of 100%, with a similar cutoff value [

12]. While the results are similar, the practical cutoff value needs to be validated with large-scale studies.

Biomarkers and inflammatory indicators in laboratory parameters are useful predictors of recurrence and long-term prognosis and are minimally invasive in patients IBD. It is well known that inflammatory indicators of IBD for disease activation in laboratory parameters are anaemia, thrombocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, elevated CRP, and ESR [

1]. The present study found lower levels of Hb and albumin, higher PLTs, and higher levels of CRP and ESR in patients with disease activation. In the literature, some studies have shown that significant positive correlations with LRG are evident for CRP, ESR, and PLT counts, whereas significant negative correlations were noted for albumin and Hb levels [

12,

14]. The s-LRG levels were correlated with inflammatory indicators in the laboratory parameters in the present study. The study also found that disease activation showed a positive association with s-LRG, ESR, CRP, and PLT count, whereas it was negatively associated with albumin and Hb. These results are similar to those of previous studies.

In patients with IBD, mucosal inflammation leads to the production of various cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-22. While serum CRP levels are mediated by IL-6, LRG production does not depend on IL-6 alone [

15]. In addition, the use of anti-TNFα antibody preparations and

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors may result in negative CRP. Therefore, it has been determined that s-LRG could reflect inflammation in patients with IBD better than CRP [

16]. Previous studies have reported that IBD patients have negative CRP results, even though they are endoscopically active [

17,

18]. A prospective study of adults showed that s-LRG was detectable in every patient, even when CRP was undetectable [

12]. Additionally, it has been shown that LRG is more effective than CRP as a marker for detecting endoscopic activity in patients with IBD and could be used for follow-up [

4,

19]. Similarly, it was found that s-LRG was a more significant parameter than CRP in predicting disease activation in the present study.

Yasuda et al. reported positive correlations between s-LRG levels and the PUCAI and PCDAI for evaluating clinical remission [

14]. Shinzaki et al. reported that serial measurements of LRG levels were significantly elevated in patients with an endoscopically active stage compared with those with a mucosal healing stage [

13]. It has been shown that there is a correlation between LRG levels and the MES in UC patients and as well as between LRG levels and the SES-CD score in CD patients[

12]. In the present study, the endoscopic scores of patients—MES and SES-CD—were correlated with s-LRG levels in UC and CD patients with disease activation, respectively. Therefore, s-LRG may predict endoscopic activation in patients who are not suitable for endoscopic evaluation.

S-LRG and FC have been studied in adults with IBD. Both FC and s-LRG have been shown to have high specificity in predicting endoscopic remission [

20]. However, biomarkers may be studied in the urine, which can be more easily obtained because of the difficulty of obtaining stool samples from children. Serum and urinary LRG have been researched for their diagnostic utility for paediatric acute appendicitis by Kakar et al. [

21]. They reported that the diagnostic performance of s-LRG and u-LRG were non-invasive, rapid, and accurate biomarkers for acute appendicitis [

21]. No study has investigated u-LRG in patients with IBD. This study evaluated the u-LRG and s-LRG levels in patients with IBD at the same time. However, u-LRG was not correlated with s-LRG or other inflammatory markers or the clinical and endoscopic activity scores of patients. This may be related to the fact that the u-LRG measurement is technically more difficult and requires more dilution. The mechanism of LRG excretion in urine is unclear. Previous reports have indicated that LRG is elevated in bacterial diseases, is expressed by neutrophils undergoing differentiation in the liver, and by high endothelial venules of the mesentery, such as the mesoappendix, and is expressed at the site of inflammation [

22,

23]. Recently, u-LRG has been reported as a possible biomarker for immunoglobulin A nephropathy, steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, and diabetic kidney disease. Thus, u-LRG may reflect local inflammation, such as that in patients with appendicitis and renal injury. Therefore, the correlation between disease activation and urinary excretion of LRG may not have been demonstrated in patients with IBD where chronic and widespread inflammation is observed due to different causes and pathological mechanisms.

This study’s limitations include the fact that it was performed as a single-centre analysis and involved a limited number of participants. In addition, colonoscopies were performed in a small number of patients. For UC and CD patients, LRG could not be evaluated separately because of the insufficient distribution of the number of patients.

Conclusion

The serum LRG level is a useful biomarker for predicting disease activation in children with IBD and appears to be a more significant parameter than the CRP. However, the u-LRG level is not effective in predicting disease activation in children with IBD. Further large-scale studies are needed to determine the clinical benefits of using LRG as a biomarker for disease activation in children with IBD.

Author contributions: Conceptualization, Yeliz Çağan Appak and Maşallah Baran; Data curation, Serenay Çetinoğlu, Sinem Kahveci, Şenay Onbaşı Karabağ and Selen Güler; Formal analysis, Murat Akşit, Selen Güler and İnanç Kara; Methodology, Betül Aksoy; Software, Serenay Çetinoğlu, Sinem Kahveci, Şenay Onbaşı Karabağ and İlksen Demir; Supervision, Yeliz Çağan Appak, İnanç Kara and Maşallah Baran; Writing – original draft, Betül Aksoy; Writing – review & editing, Yeliz Çağan Appak and Maşallah Baran. All authors critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article (and its additional files).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was financially supported by Turkish Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tepecik Training and Research Hospital. (No 2022/18/3; date of approval: 07/12/2022). Written informed consent was provided by parents/legal guardians of the children enrolled in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge to Associate Professor Dr. Engin Köse for statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IBD |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

| CD |

Crohn’s disease |

| UC |

Ulcerative colitis |

| IBD-U |

Unclassified inflammatory bowel disease |

| PCDAI |

Paediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index |

| PUCAI |

Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index |

| CRP |

C-reactive protein |

| FC |

Faecal calprotectin |

| LRG |

Leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| TNF |

Tumor necrosis factor |

| s-LRG |

Serum leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein |

| u-LRG |

Urinary leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein |

| ESR |

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| PLT |

Platelet |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| SES-CD |

Simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease |

| MES |

Mayo endoscopic score |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

References

- C. Conrad MA, Rosh JR. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;64(3):577-591. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues BL, Mazzaro MC, Nagasako CK, Ayrizono MLS, Fagundes JJ, Leal RF. Assessment of disease activity in inflammatory bowel diseases: Non-invasive biomarkers and endoscopic scores. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 Dec 16;12(12):504-520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaoul R, Day AS. An Overview of Tools to Score Severity in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Pediatr. 2021 Apr 12;9:615216. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakov, R. New markers in ulcerative colitis. Clin Chim Acta. 2019 Oct;497:141-146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasson A, Stotzer PO, Öhman L, Isaksson S, Sapnara M, Strid H. The intra-individual variability of faecal calprotectin: a prospective study in patients with active ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015 Jan;9(1):26-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichimiya T, Kazama T, Ishigami K, Yokoyama Y, Hayashi Y, Takahashi S, Itoi T, Nakase H. Application of plasma alternative to serum for measuring leucine-rich α2-glycoprotein as a biomarker of inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2023 Jun 23;18(6):e0286415. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka K, Kitazume Y, Kawamoto A, Fujii T, Udagawa Y, Wanatabe R, Shimizu H, Hibiya S, Nagahori M, Ohtsuka K, Sato H, Hirakawa A, Watanabe M, Okamoto R. Serum Leucine-Rich α2 Glycoprotein: A Novel Biomarker for Transmural Inflammation in Crohn's Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun 1;118(6):1028-1035. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura T, Mitsuyama K, Sakemi R, Takedatsu H, Yoshioka S, Kuwaki K, et al. Evaluation of Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein as a New Inflammatory Biomarker of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2021; 2021:8825374. [CrossRef]

- Arredondo Montero J, Pérez Riveros BP, Bueso Asfura OE, Rico Jiménez M, López-Andrés N, Martín-Calvo N. Leucine-Rich Alpha-2-Glycoprotein as a non-invasive biomarker for pediatric acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2023 Jul;182(7):3033-3044. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner D, Otley AR, Mack D, Hyams J, de Bruijne J, Uusoue K, Walters TD, Zachos M, Mamula P, Beaton DE, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Development, validation, and evaluation of a pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index: a prospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology. [CrossRef]

- Shepanski MA, Markowitz JE, Mamula P, Hurd LB, Baldassano RN. Is an abbreviated Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index better than the original? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura T, Mitsuyama K, Sakemi R, Takedatsu H, Yoshioka S, Kuwaki K, Mori A, Fukunaga S, Araki T, Morita M, Tsuruta K, Yamasaki H, Torimura T. Evaluation of Serum Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein as a New Inflammatory Biomarker of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2021 Feb 1;2021:8825374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinzaki, K. Matsuoka, H. Iijima, S. Mizuno, S. Serada, M. Fujimoto, N. Arai, N. Koyama, E. Morii, M. Watanabe, T. Hibi, T. Kanai, T. Takehara, T. Naka, Leucinerich Alpha-2 glycoprotein is a serum biomarker of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis, J. 2017; 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda R, Arai K, Kudo T, Nambu R, Aomatsu T, Abe N, Kakiuchi T, Hashimoto K, Sogo T, Takahashi M, Etani Y, Kato K, Yamashita Y, Mitsuyama K, Mizuochi T. Serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein and calprotectin in children with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul;38(7):1131-1139. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida T, Shimodaira Y, Fukuda S, Watanabe N, Koizumi S, Matsuhashi T, Onochi K, Iijima K. Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein in Monitoring Disease Activity and Intestinal Stenosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2022 Jul 16;257(4):301-308. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, BE. Biomarkers of Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015 Oct;149(5):1275-1285.e2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakarai A, Kato J, Hiraoka S, Inokuchi T, Takei D, Morito Y, et al. Slight Increases in the Disease Activity Index and Platelet Count Imply the Presence of Active Intestinal Lesions in C-reactive Protein-negative Crohn’s Disease Patients. Inten Med. 2014; 53(17):1905–11. [CrossRef]

- Ichimiya T, Kazama T, Ishigami K, Yokoyama Y, Hayashi Y, Takahashi S, Itoi T, Nakase H. Application of plasma alternative to serum for measuring leucine-rich α2-glycoprotein as a biomarker of inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2023 Jun 23;18(6):e0286415. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serada S, Fujimoto M, Ogata A, Terabe F, Hirano T, Iijima H, Shinzaki S, Nishikawa T, Ohkawara T, Iwahori K, Ohguro N, Kishimoto T, Naka T. iTRAQ-based proteomic identification of leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a novel inflammatory biomarker in autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Apr;69(4):770-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe I, Shiga H, Chiba H, Miyazawa T, Oomori S, Shimoyama Y, Moroi R, Kuroha M, Kakuta Y, Kinouchi Y, Masamune A. Serum leucine-rich alpha-2 glycoprotein as a predictive factor of endoscopic remission in Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Sep;37(9):1741-1748. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakar M, Berezovska MM, Broks R, Asare L, Delorme M, Crouzen E, Zviedre A, Reinis A, Engelis A, Kroica J, Saxena A, Petersons A. Serum and Urine Biomarker Leucine-Rich Alpha-2 Glycoprotein 1 Differentiates Pediatric Acute Complicated and Uncomplicated Appendicitis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 ;11(5):860. 11 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salö M, Roth B, Stenström P, Arnbjörnsson E, Ohlsson B. Urinary biomarkers in pediatric appendicitis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016 Aug;32(8):795-804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee H, Fujimoto M, Ohkawara T, et al. Leucine rich α-2 glycoprotein is a potential urinary biomarker for renal tubular injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018 Apr 15;498(4):1045-1051. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).