Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

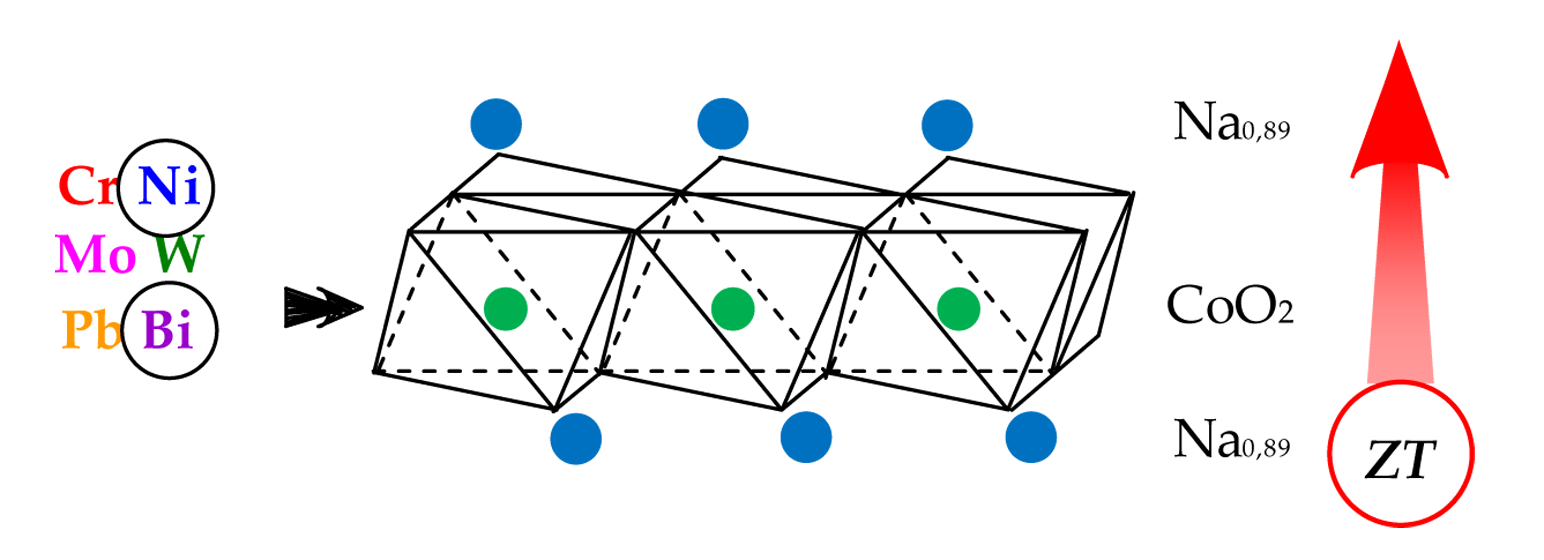

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

= 3 Na0.89Co0.90Me0.10O2 + 1.335 CO2

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klyndyuk, A.I.; Kharytonau, Dz.S.; Matsukevich, I.V.; Chizhova, E.A.; Lenčéš, Z.; Socha, R.P.; Zimowska, M.; Hanzel, O.; Janek, M. Effect of cationic nonstoichiometry on thermoelectric properties of layered calcium cobaltite obtained by field assisted sintering technology (FAST). Ceramics International. 2024, 50, 30970–30979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polevik, A.O.; Sobolev, A.V.; Glazcova, Ia.S.; Presniakov, I.A.; Verchenko, V.Yu.; Link, J.; Stern, R.; Shevelkov, A.V. Interplay between Fe(II) and Fe(III) and Its Impact on Thermoelectric Properties of Iron-Substituted Colusites Cu26–xFexV2Sn6S32. Compounds. 2023, 3, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chen, K.; Azough, F.; Alvarez-Ruiz, D.T.; Reece, M.I.; Freer, R. Enhancing the thermoelectric performance of calcium cobaltite ceramics by tuning composition and processing. ACS Applied Materials Interfaces. 2020, 12, 47634–47646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, K.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y. Influence of the phase transformation in NaxCoO2 ceramics on thermoelectric properties. Ceramics International. 2018, 44, 17251–17257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, C.; Xie, Y. Layered thermoelectric materials: Structure, bonding, and performance mechanisms. Applied Physics Review. 2020, 9, 011303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzanyan, A.S.; Margani, N.G.; Zhghamadze, V.V.; Mumladze, G.; Badalyan, G.R. Impact of Sr(BO2)2 Dopant on Power Factor of Bi2Sr2Co1.8Oy Thermoelectric. Journal of Contemporary Physics. 2021, 56, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oopathumpa, Ch.; Boonthuma, D.; Smith, S. M. Effect of Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) on Thermoelectric Properties of Sodium Cobalt Oxide. Key Engineering Materials. 2019, 798, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, M.M.; Vitta, V. Enhancing Thermoelectric Figure-of-Merit of Polycrystalline NayCoO2 by a Combination of Non-stoichiometry and Co-substitution. Journal of Electronic Materials. 2018, 47, 3230–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chang, Y.; Jakubczyk, E.; Wang, B.; Azough, F.; Dorey, R.; Freer, R. Modulation of electrical transport in calcium cobaltite ceramics and thick films through microstructure control and doping. Journal of the European Ceramic Society. 2021, 41, 4859–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noudem, J.G.; Xing, Yi. Overview of Spark Plasma Texturing of Functional Ceramics. Ceramics. 2021, 4, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Hoppe, R. Notiz zur Kenntnis der Oxocobaltate des Natriums. Zeitschrift für anorganische und allgemeine Chemie. 1974, 408, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, I.; Sasago, Y.; Uchinokura, K. Large thermoelectric power in NaCo2O4 single crystals. Physical Review B. 1997, 56, R12685–R12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoto, K.; Terasaki, I.; Funahashi, R. Complex Oxide Materials for Potential Thermoelectric Applications. MRS BULLETIN. 2006, 31, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viciu, L.; Huang, Q.; Cava, R.J. Stoichiometric oxygen content in NaxCoO2. Physical Review B 2006, 73, 212107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Yu.; Ruan, Yo.; Xue, M.; Shi, M.; Song, Zh.; Zhou, Y.; Teng, J. Effect of Annealing Time on the Cyclic Characteristics of Ceramic Oxide Thin Film Thermocouples. Micromachines. 2022, 13, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasutskaya, N.S.; Klyndyuk, A.I.; Evseeva, L.E.; Gundilovich, N.N.; Chizova, E.A.; Paspelau, A.V. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of Na0.55CoO2 ceramics doped by transition and heavy metal oxides. Solids. 2024, 5, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenda, J.; Baster, D.; Milewska, A.; Świerczek, K.; Bora, D.K.; Braun, A.; Tobola, J. Electronic origin of difference in discharge curve between LixCoO2 and NaxCoO2 cathodes. Solid State Ionics. 2014, 271, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohle, B.; Gorbunov, M.; Lu, Q.; Bahrami, A.; Nielsch, K.; Mikhailova, D. Structural and electrochemical properties of layered P2-Na0.8Co0.8Ti0.2O2 cathode in sodium-ion batteries. Energies. 2022, 15, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.M.; Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, D.M.N.; Le, M.K.; Tran, V.M.; Le, M.L.P. Evaluating electrochemical properties of layered NaxMn0.5Co0.5O2 obtained at different calcined temperatures. Chemengineering. 2023, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baster, D.; Zająс, W.; Kondracki, Ł.; Hartman, F.; Molenda, J. Improvement of electrochemical performance of Na0.7Co1–yMnyO2–cathode material for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. Solid State Ionics. 2016, 288, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banobre-López, M.; Rivadulla, F.; Caudillo, R.; López-Quintela, M.A.; Rivas, J.; Goodenough, J.B. Role of doping and Dimensionality in the Superconductivity of NaxCoO2. Chemistry of Materials. 2005, 17, 1965–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, R.; Khan, J.; Rafique, S.; Hussain, M.; Maqsood, A.; Naz, A.A. Enhanced thermoelectric properties of single phase Na doped NaxCoO2 thermoelectric material. Materials Letters. 2021, 300, 130180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadi, M.H.N.; Katayama-Yoshida, H. Restoration of long range order of Na ions in NaxCoO2 at high temperatures by sodium site doping. Computational Materials Science. 2015, 109, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Viciu, L.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Foo, M.L.; Watauchi, S.; Pascal, R.A., Jr.; Cava, R.J.; Ong, N.P. Enhancement of thermopower in NaxCoO2 in the large-x regime (x ≥ 0.75). Physica B. 2008, 403, 1564–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasutskaya, N.S.; Klyndyuk, A.I.; Evseeva, L.E.; Tanaeva, S.A. Synthesis and properties of NaxCoO2 (x = 0.55, 0.89) oxide thermoelectric. Inorganic Materials. 2016, 52, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohle, B.; Gorbunov, M.; Lu, Q.; Bahrami, A.; Nielsch, K.; Mikhailova, D. Structural and electrochemical properties of layered P2-Na0.8Co0.8Ti0.2O2 cathode in sodium-ion batteries. Energies. 2022, 15, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi Meena, J.; Gayathri, N.; Bharathi, A.; Ramachandran, K. Effect of nickel substitution on thermal properties of Na0.9CoO2. Bulletin of Materials Science. 2007, 30, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, Zh.; Hu, Ya.; Wu, Yi.; Han, Ch.; Hu, Zh. Power factor enhancement induced by Bi and Mn co-substitution in NaxCO2 thermoelectric materials. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2016, 661, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, Ya.; Kato, N.; Miyazaki, Yu.; Kajitani, T. Transport Properties of Ca-doped γ-NaxCoO2. Journal of Ceramic Society of Japan. 2004, 5, S626–S628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadi, M.H.N.; Katayama-Yoshida, H. ; Restoration of long order of Na ions in NaxCoO2 at high temperatures by sodium site doping. Computational Materials Science. 2015, 109, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Ju.; Hu, Zh. Power factor enhancement in NaxCoO2 doped by Bi. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2014, 582, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetawan, T.; Amornkitbamburg, V.; Burinprakhon, Th.; Maensiri, S.; Kurosaki, K.; Muta, H.; Uno, M.; Yamanaka, Sh. Thermoelectric power and electrical resistivity of Ag-doped Na1.5Co2O4. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2006, 407, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Assadi, N. Hf doping for enhancing the thermoelectric performance in layered Na0.75CoO2. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2021, 42, 1542–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhowong, R. Effect of reduced graphene oxide on the enhancement of thermoelectric power factor of γ-NaxCo2O4. Materials Science &Engineering B. 2020, 261, 114679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Nagira, T.; Furumoto, D.; Katsuyama, Sh.; Nagai, H. Synthesis of NaxCoO2 thermoelectric oxides by the polymerized complex method. Scripta Materialia. 2003, 48, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suan, M.S.M.; Farhan, M.A.; Lau, K.T.; Munawar, R.F.; Ismail, S. Structural and Electrical Properties of NaxCoO2 Thermoelectric Synthesized via Citric-Nitrate Auto-Combustion Reaction. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2018, 1082, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, Ic.; Zhou, Yu.; Takeuchi, T.; Funahashi, R.; Shikano, M.; Murayama, N.; Shin, W.; Izu, N. Thermoelectric Properties of Spark-Plasma-Sintered Na1+xCoO2 Ceramics. Journal of Ceramic Society of Japan. 2003, 111, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Jang, K.U.; Know, H. –C.; Kim, J.–G.; Cho, W.–S., Y. Influence of partial substitution of Cu for Co on the thermoelectric properties of NaCo2O4. J. of Alloys and Compounds. 2006, 419, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, I.; Tsukada, I.; Iguchi, Y. Impurity-induced transition and impurity-enhanced thermopower in the thermoelectric oxide NaCo2–xCuxO4. PHYSICAL REVIEW B. 2002, 65, 195106–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Choi, J.W.; Lee, G.W.; Kim, S.-J.; Lim, Y.-S.; Choi, S.-M.; Seo, W.-S.; Lim, S.M. Thermoelectric Properties of Solution-Combustion-Processed Na(Co1–xNix)2O4. Materials Letters 2012, 18, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Jang, K.U. Improvement in High-Temperature Properties of NaCo2O4 through Partial Substitution of Ni for Co. Materials Letters. 2006, 60, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Lee, J.H. Enhanced Thermoelectric Properties of NaCo2O4 by Adding Zn. Materials Letters. 2008, 62, 2366–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyndyuk, A.I.; Krasutskaya, N.S.; Chizhova, E.A.; Evseeva, L.E.; Tanaeva, S.A. Synthesis and properties of Na0.55Co0.9M0.1O2 (M =Sc, Ti, Cr-Zn, Mo, W, Pb, Bi) solid solutions. Glass Physics and Chemistry. 2016, 42, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyndyuk, A.I.; Krasutskaya, N.S.; Dyatlova, E.M. Influence of sintering temperature on the properties of NaxCoO2 ceramics. Proceedings of BSTU. (in Russian). 2010, XVIII, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pyatnitsky, I.V. Analitical chemistry of cobalt. Science: Moscow, 1965, 292 p (in Russian).

- Sopicka-Lizer, M.; Kozłowska, K.; Bobrowska-Grzesik, E.; Plewa, J.; Altenburg, H. Assessment of Co(II), Co(III) and Co(IV) content in thermoelectric cobaltites. Arhives of Metallurgy and Materials. 2009, 54, 881–888. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, S.; Kumar, N.; Chand, S. Structural, morphological, optical and dielectric properties of Ti1–xFexO2 nanoparticles sythesized using sol-gel method. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology. 2022, 105, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwah, T.J. Using the size strain plot method to specity lattice parameters. Haitham Journal for Pure and Applied Science. 2023, 36, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotgering, F.K. Topotactical reactions with ferrimagnetic oxides having hexagonal crystal structures. Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 1959, 9, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyndyuk, A.I.; Chizhova, E.A.; Latypov, R.S.; Shevchenko, S.V.; Kononovich, V.M. Effect of the addition of copper particles on the thermoelectric properties of the Ca3Co4O9+δ ceramics produced by two-step sintering. Inorganic Materials. 2022, 67, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyndyuk, A.I.; Petrov, G.S.; Poluyan, A.F.; Bashkirov, L.A. Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Y2Ba1–xMxCuO5 (M = Sr, Ca) Solid Solutions. Inorganic Materials. 1999, 35, 512–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorkovská, A.; Feher, A.; Sébek, J.; Šantavá, E.; Bradaric, I. Non-Fermi-liquid behavior in the layered NaxCoO2. Low Temperature Physics. 2007, 33, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.J.; Ursell, T.S. Thermoelectric Efficiency and Compatibility. Physical Review Letters. 2003, 91, 148301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, C.; Braconnier, J.-J.; Fouassier, C.; Hagenmuller, P. Electrochemical intertcalation of sodium in NaxCoO2 bronzes. Solid State Ionics. 1981, 3, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, F.; Wang, L.; Nakano, H. High temperature electrical conductivity and thermoelectric power of NaxCoO2. Solid State Ionics. 2008, 179, 2308–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, I.; Zhou, Yu.; Takeuchi, T.; Funahashi, R.; Shikano, M.; Murayama, N.; Shin, W.; Izu, N. Thermoelectric properties of spark-plasma-sintered Na1+xCo2O4 ceramics. Journal of Сeramic Society of Japan. 2003, 111, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jiang, Ya.; Li, G.; Wang, Ch.; Shi, J.; Yu, D. Self-ignition route to Ag-doped Na1.7Co2O4 and its thermoelectric properties. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2009, 467, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Hu, Zh. Power factor enhancement in NaxCoO2 doped by Bi. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2014, 582, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baster, D.; Zająс, W.; Kondracki, Ł.; Hartman, F.; Molenda, J. Improvement of electrochemical performance of Na0.7Co1–yMnyO2–cathode material for rechargeable sodium-ion batteries. Solid State Ionics. 2016, 288, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyndyuk, A.I.; Matsukevich, I.V. Synthesis, structure and properties of Ca3Co3.85M0.15O9+δ (M – Ti–Zn, Mo, W, Pb, Bi). Russian Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2015, 51, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Lan, J.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Nan, C.-W.; Li, J.-F. High-temperature electrical transport behaviors in textured Ca3Co4O9-based polycrystalline ceramics, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 072107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhu, K.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, K.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y. Influence of the phase transformation in NaxCoO2 ceramics on thermoelectric properties. Ceramics International. 2018, 44, 17251–17257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.J.; Snyder, Al.H.; Wood, M; Gurunathan, R.; Snyder, B.H.; Niu, Ch. Weighted Mobility. Advanced Materials 2020, 200, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Sh.; Chen, Sh.; Liu, F.; Yan, G.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Fu, G. Laser-induced voltage effects in c-axis inclined NaxCoO2 thin films. Applied Surface Science 2012, 258, 7330–7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tang, X.; Sharp, J. Low-temperature solid state synthesis and thermoelectric properties of high-performance and low-cost Sb-doped Mg2Si0.6Sn0.4. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2010, 43, 085406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

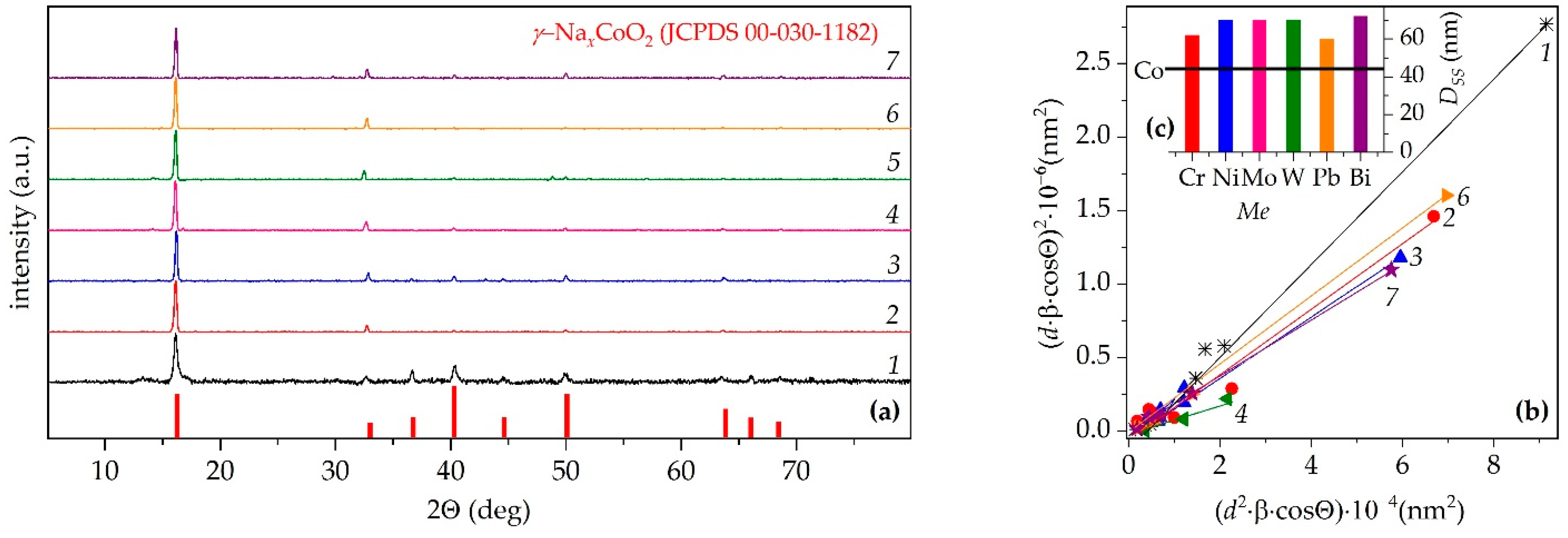

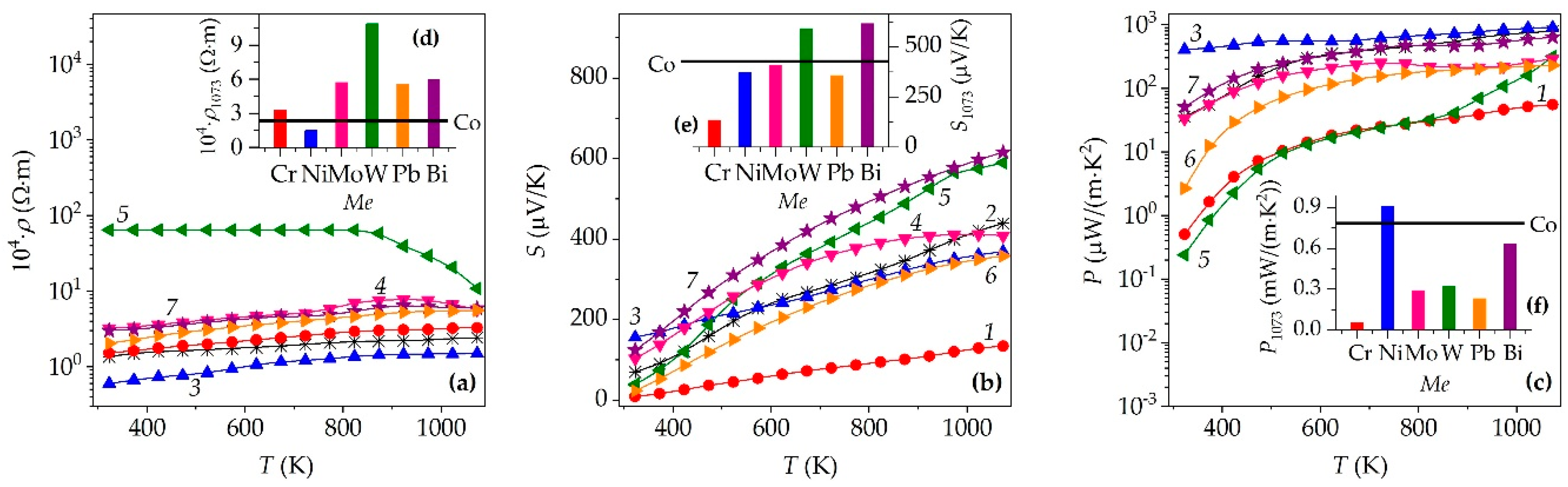

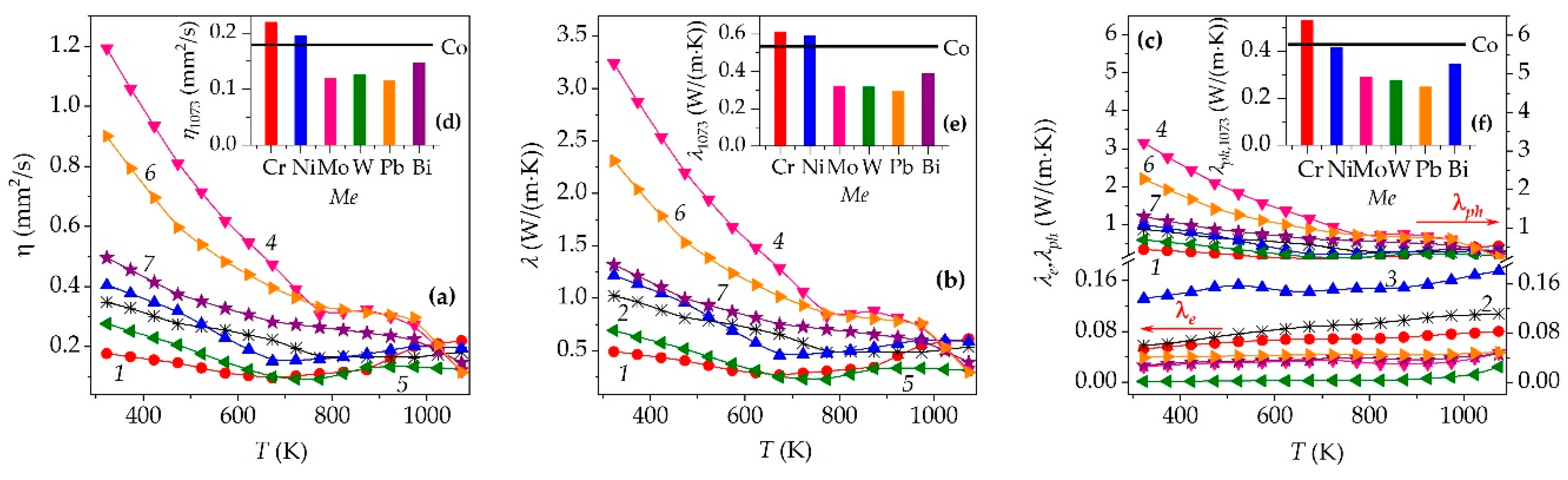

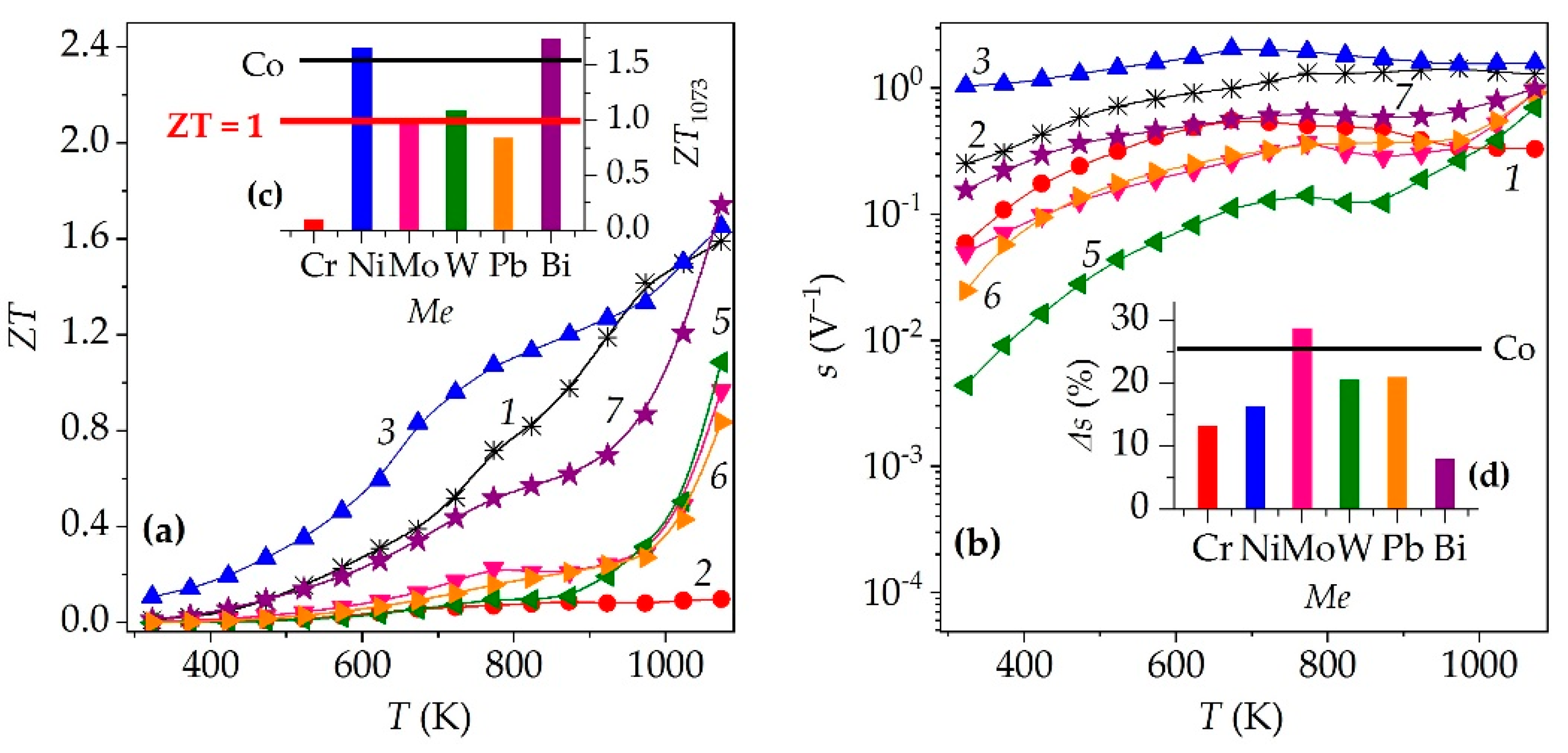

| Me | xNa | Co+Z | a, Å | c, Å | c/a | V, Å3 | f | Ds, nm | DSS, nm | ε×104 | dXRD, g/cm3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | 0.893 | 3.11 | 2.825 | 10.93 | 3.870 | 75.53 | 0.90 | 69 | 62 | 3.43 | 4.86 |

| Co | 0.891 | 3.11 | 2.826 | 10.94 | 3.872 | 75.71 | 0.31 | 63 | 45 | 4.56 | 4.98 |

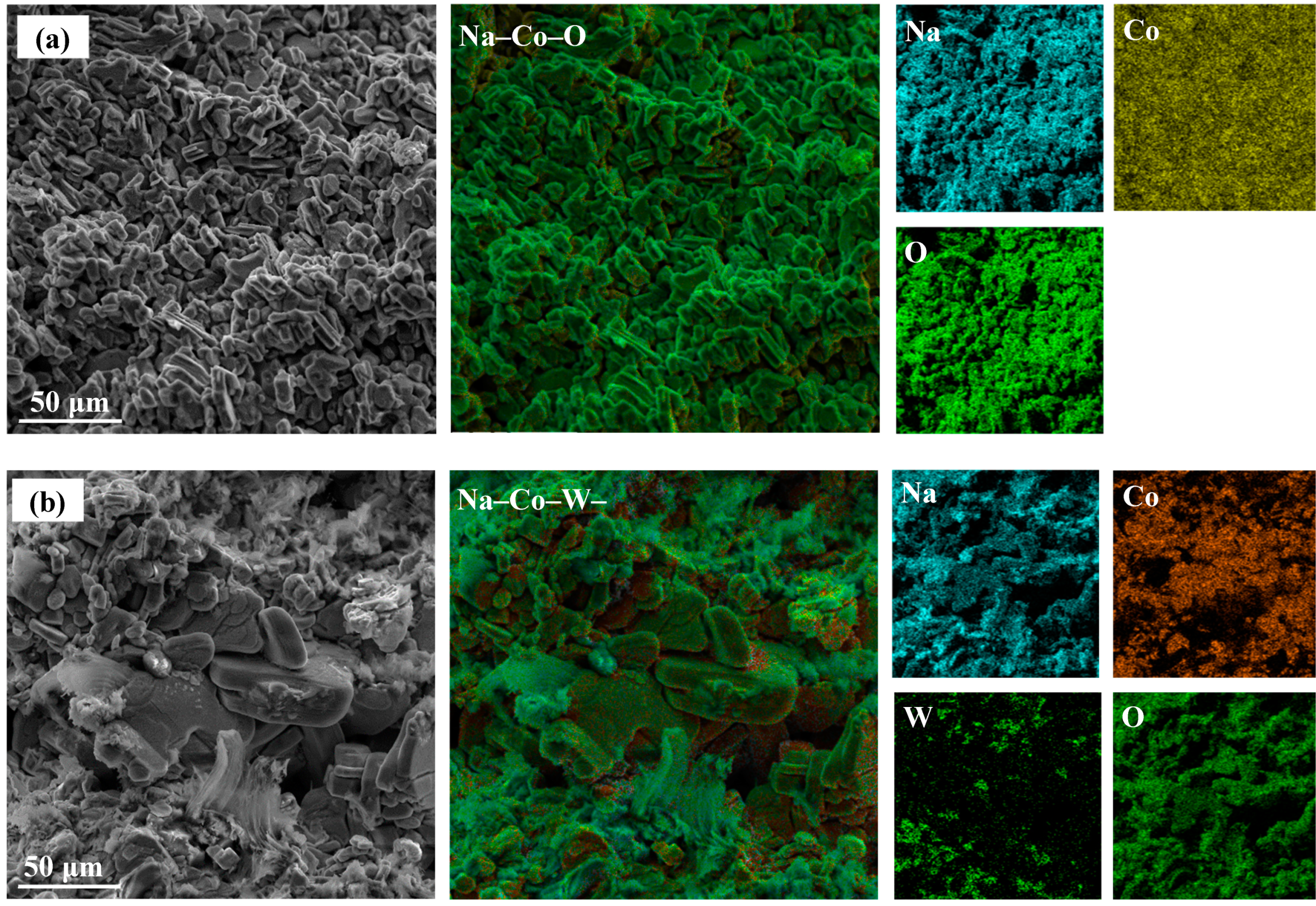

| Ni | 0.889 | 3.23 | 2.831 | 10.92 | 3.856 | 75.75 | 0.69 | 70 | 70 | 2.61 | 4.88 |

| Mo | 0.894 | 2.78 | 2.822 | 10.96 | 3.883 | 75.57 | 0.87 | 73 | 70 | 1.41 | 5.06 |

| W | 0.889 | 2.78 | 2.825 | 10.97 | 3.884 | 75.80 | 0.92 | 67 | 69 | 1.50 | 5.43 |

| Pb | 0.888 | 3.01 | 2.825 | 10.94 | 3.873 | 75.64 | 0.92 | 79 | 60 | 3.22 | 5.55 |

| Bi | 0.894 | 2.90 | 2.823 | 10.93 | 3.872 | 75.45 | 0.76 | 77 | 72 | 2.49 | 5.56 |

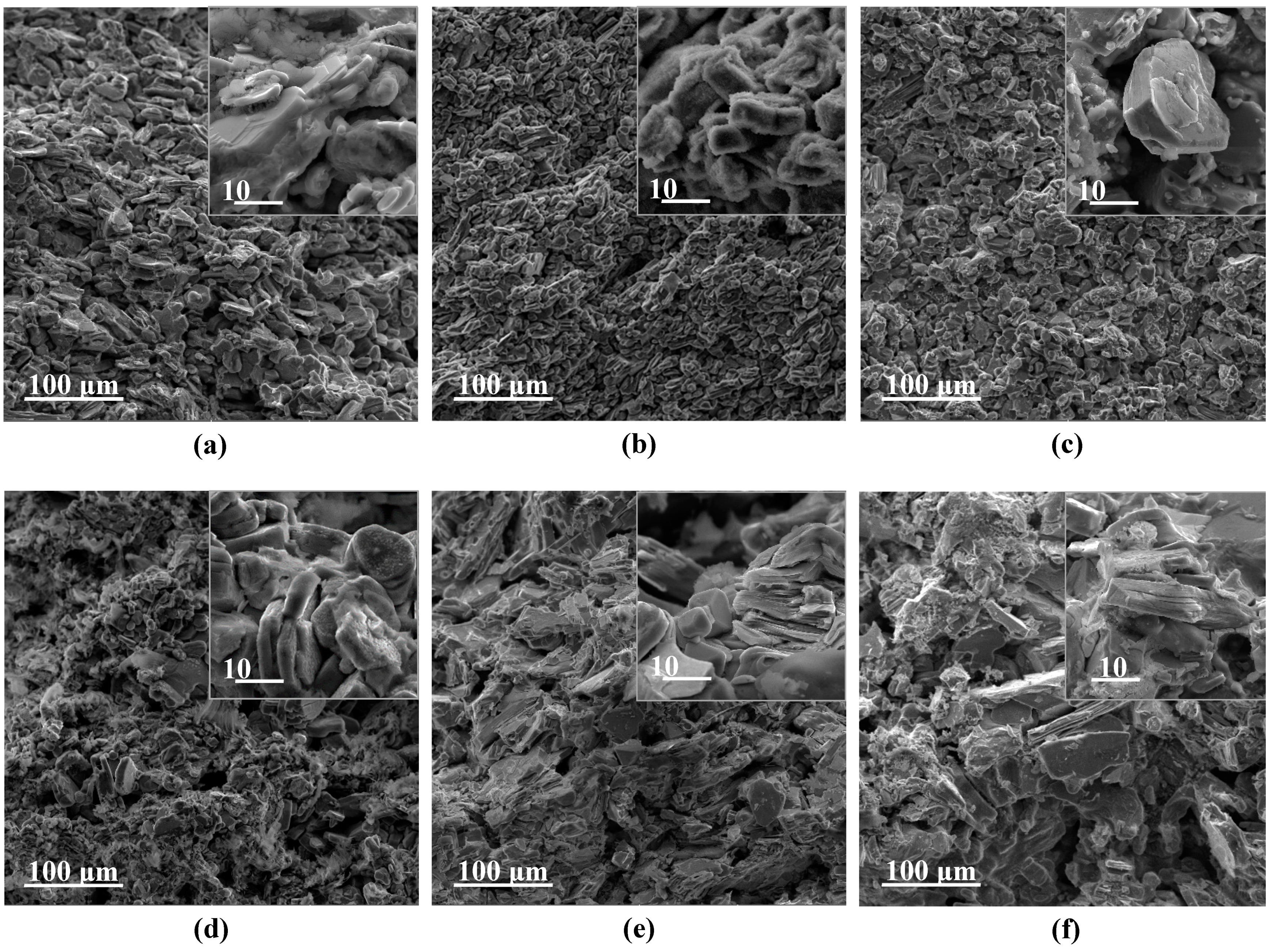

| M |

dEXP, g/cm3 |

Πt, % | Πo, % | Πc, % | 105×α, К–1 | 104×ρ1073, Ω·m |

S1073, μV/K |

P1073, mW/(m·K2) |

λ1073, W/(m·K) |

ZT1073 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | 3.18 | 35 | 16 | 19 | 1.68 | 3.28 | 134 | 0.055 | 0.613 | 0.10 |

| Co | 3.38 | 32 | 19 | 13 | 1.34 | 2.43 | 439 | 0.794 | 0.536 | 1.59 |

| Ni | 3.46 | 29 | 22 | 7 | 1.42 | 1.50 | 369 | 0.910 | 0.591 | 1.65 |

| Mo | 3.22 | 36 | 19 | 17 | 1.47 | 5.73 | 408 | 0.291 | 0.323 | 0.97 |

| W | 3.20 | 41 | 17 | 24 | 1.39 | 10.9 | 519 | 0.320 | 0.316 | 1.09 |

| Pb | 3.34 | 40 | 18 | 22 | 1.26 | 5.58 | 358 | 0.230 | 0.295 | 0.84 |

| Bi | 3.47 | 38 | 18 | 20 | 1.25 | 5.97 | 616 | 0.636 | 0.392 | 1.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).